LAO Contact

March 30, 2017

California Community Colleges

Effects of Increases in Noncredit Course Funding Rates

Executive Summary

Background

Noncredit Education Is a Key Mission of California Community Colleges (CCC). State law defines CCC’s core mission as offering credit instruction through the associate degree level. Statute also assigns CCC the “essential and important function” of providing precollegiate instruction through adult noncredit education. For many years, the state funded all CCC noncredit courses at a rate comparable to what school districts received for adult education (about $2,000 per full‑time equivalent student). In 2005‑06, this rate was just under half the average rate for CCC credit instruction. The lower funding rate reflected the generally lower costs for noncredit programs, mainly because of lower faculty pay rates.

Legislature Increased Funding Rate for Certain Noncredit Courses. Chapter 631 of 2006 (SB 361, Scott) created a special category of noncredit education called “career development and college preparation” (CDCP), which covers instruction in elementary and secondary education, English as a second language (ESL), workforce preparation, and vocational education that is part of a sequence of courses leading to a certificate. Chapter 631 raised the state funding rate for this category of courses to 71 percent of the credit rate, compared with 60 percent of the credit rate for other types of noncredit instruction (such as citizenship and parenting classes). Chapter 34 of 2014 (SB 860, Senate Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) further increased the state’s funding rate for CDCP courses to 100 percent of the credit rate, effective beginning in 2015‑16. The higher rate was intended to encourage colleges to expand their CDCP offerings and, in particular, better support noncredit vocational programs, which sometimes have relatively high equipment and facility costs.

Findings

Studying Impacts of Rate Increases. Chapter 34 directed our office to report on changes in CDCP certificate programs, course offerings, and enrollment following the 2015‑16 rate increase. Our findings are preliminary given that only one year of data is available following implementation of Chapter 34.

Colleges Developed 87 New Certificate Programs After Passage of Chapter 34. Overall, the number of new certificate programs grew modestly—from 566 in 2013‑14 to 653 in 2015‑16. The Chancellor’s Office approved new certificate programs at 20 of CCC’s 113 colleges, with most of these colleges adding between one and three new certificate programs. One college, though, added 34 certificate programs in a major revamping of its noncredit offerings that began prior to 2014‑15, which skews the total. The newly approved certificate programs primarily are in the areas of vocational, ESL, and elementary and secondary education. Of the new vocational programs, about one‑quarter appear to be in areas that might have higher costs.

Number of CDCP Course Sections Increased Relative to Other Categories. The number of CDCP course sections remained flat from 2009‑10 through 2014‑15, while the number of credit and other noncredit course sections declined substantially through 2012‑13, then increased substantially the next two years. In 2015‑16, the number of CDCP course sections increased 11 percent while the number of credit sections grew 3 percent and the number of other noncredit sections declined 7 percent.

CDCP Enrollment Also Increased Relative to Other Categories. Enrollment in all three CCC instructional categories—credit, CDCP, and other noncredit—declined from 2007‑08 to 2012‑13 following CCC budget reductions. Both credit and CDCP enrollment grew somewhat from 2012‑13 to 2014‑15, while other noncredit enrollment remained flat. Since 2014‑15, only CDCP enrollment has grown while the other categories have remained flat or declined.

Assessment

These early findings suggest Chapter 34 has had some of the effects the Legislature intended. The rate increase, however, also raises several concerns, as we summarize below.

Funding for CDCP Not Well‑Aligned With Actual Costs. Although colleges have modestly expanded the number of higher‑cost vocational programs, ESL and elementary and secondary education courses (which typically have lower costs) account for 86 percent of all CDCP enrollment. Moreover, to the extent that some CDCP certificate programs are higher cost, the state now provides ongoing funding to support those costs through the Adult Education Block Grant (AEBG), which began in 2015‑16, and the Strong Workforce Program, which began in 2016‑17. Several colleges also report drawing on other CCC categorical programs, including the Student Success and Support and Basic Skills Initiative programs, to augment services for their CDCP students. Given the overlap between these programs, AEBG, Strong Workforce, and CDCP, the Legislature may want to rethink whether funding CDCP courses at the credit rate still makes sense.

Delineation Between Credit and Noncredit Instruction Remains Unresolved. Currently, colleges largely decide for themselves whether to offer a precollegiate course as credit or noncredit. Such differences make assessing the effectiveness of CCC precollegiate education difficult. Furthermore, a clearer delineation would be especially important were the Legislature to fund credit and CDCP at different rates in the future.

Limited Data and Accountability Measures for CDCP Programs. CCC accountability systems generally exclude data on noncredit programs. Currently no statewide data exists to assess the value of CCC’s 653 CDCP certificate programs created to date. Though some of these programs (such as programs leading to nursing assistant and welding certificates) likely have immediate workforce value to students, the benefit of others (such as programs leading to certificates in “number arithmetic” or “basic skills world history”) is less obvious.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

We raise four key related issues the Legislature could explore moving forward. The issues entail the appropriate funding rates for noncredit instruction, the respective roles and definitions of credit and noncredit instruction, the accessibility of noncredit and adult education across the state, and the system the state has for measuring the effectiveness of noncredit and adult education. By addressing these issues, we believe the Legislature could improve significantly the effectiveness of noncredit and adult education in California over the coming years.

Introduction

Chapter 34 of 2014 (SB 860, Senate Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) increased the state’s funding rate for certain California Community Colleges (CCC) noncredit courses. Specifically, the legislation increased the funding rate beginning in 2015‑16 for noncredit “career development and college preparation” (CDCP)—instruction in elementary and secondary education, English as a second language (ESL), vocational skills, and workforce preparation that is part of a sequence of related courses leading to a certificate. Chapter 34 directs our office to report on changes in CDCP programs, course offerings, and students served following the rate increase. This report fulfills that reporting requirement. We begin by providing background on CCC instruction and course funding rates. Next, we provide our findings and assessment regarding changes in levels of CDCP instruction following the recent rate increase. We conclude by identifying several issues for the Legislature’s consideration regarding CCC noncredit instruction.

Background

Below, we provide background on CCC’s mission, credit and noncredit instruction at the community colleges, and the two main classifications of noncredit courses—regular noncredit and CDCP. We also discuss changes in the state funding rate for CDCP courses.

CCC Mission

Community Colleges Have Multiple Missions. State law defines CCC’s core mission as providing academic and vocational instruction through the second year of college, and authorizes community colleges to award the associate degree. Beyond this primary mission, community colleges also are assigned the “essential and important function” of providing remedial instruction (precollegiate‑level English and math) and adult noncredit education. Adult education includes elementary and secondary education—such as literacy and high school diploma or equivalency programs—as well as ESL, short‑term vocational education, workforce preparation, and programs for older adults and adults with disabilities. (Community colleges offer adult education in coordination with school districts and other education providers.) Additional community college missions include providing fully fee‑supported community services courses and economic development services such as employee training.

Credit and Noncredit Instruction

Some Overlap Between CCC Credit and Noncredit Instruction . . . In general, colleges fulfill their mission of offering the first two years of college instruction in academic and vocational subjects through credit instruction, whereas they use noncredit instruction to address much of their precollegiate adult education mission. Regulations, however, permit colleges to offer some precollegiate instruction on a credit basis, including some ESL, secondary English and math courses, and many vocational education courses.

. . . But Notable Differences Between Them. Though CCC credit and noncredit instruction overlap, they differ in six notable ways, as shown in Figure 1. First, credit courses may be in any academic or vocational subject, whereas noncredit instruction is limited to ten categories. Second, depending on the course and college, a student may be permitted to join or leave a noncredit class at any time during the term. Third, only credit courses have restrictions on the number of times a student may reenroll (such as to better master the course material) after receiving a passing grade. Fourth, CCC regulations generally require that faculty possess at least a bachelor’s degree in order to teach a noncredit course, compared to a master’s degree for most credit courses. Fifth, students are charged enrollment fees only for credit courses. Lastly, the state funds some noncredit courses at a lower rate than credit courses and calculates attendance differently.

Figure 1

Key Differences Between Credit and Noncredit Courses

|

Credit Courses |

Noncredit Courses |

|

|

Subjects |

May be in any academic or vocational subject. May be college level or precollegiate. |

State funding is limited to ten categories of noncredit courses, all precollegiate (see categories in Figure 2). |

|

Attendance Requirements |

Students are expected to participate in the course during specific hours throughout the term and complete homework. |

Depending on the course, students may be permitted to join or leave a class at any time during the term. Typically does not require homework. |

|

Course Repetition |

Students who receive a satisfactory grade generally may not reenroll in the same course. In addition, students may not earn more than 30 semester units of credit for remedial courses. |

Typically no restriction on the number of times a student may reenroll in the same class. |

|

Faculty Qualifications |

Regulations generally require that faculty possess at least a master’s degree (with exceptions for certain vocational disciplines). |

Regulations generally require that faculty possess at least a bachelor’s degree. |

|

Enrollment Fees |

State law establishes mandatory enrollment fees. For 2016‑17, fees are $46 per unit. |

State law prohibits enrollment fees. |

|

Funding |

For 2016‑17, the funding rate per full‑time equivalent (FTE) student is $5,070. Funding generally is based on student enrollment in a course at a given point in the academic term (typically the third or fourth week). |

For 2016‑17, the funding rates per FTE student are $3,049 for regular noncredit courses and $5,070 for career development and college preparation courses (same as the credit rate). Funding is based on students’ daily course attendance. |

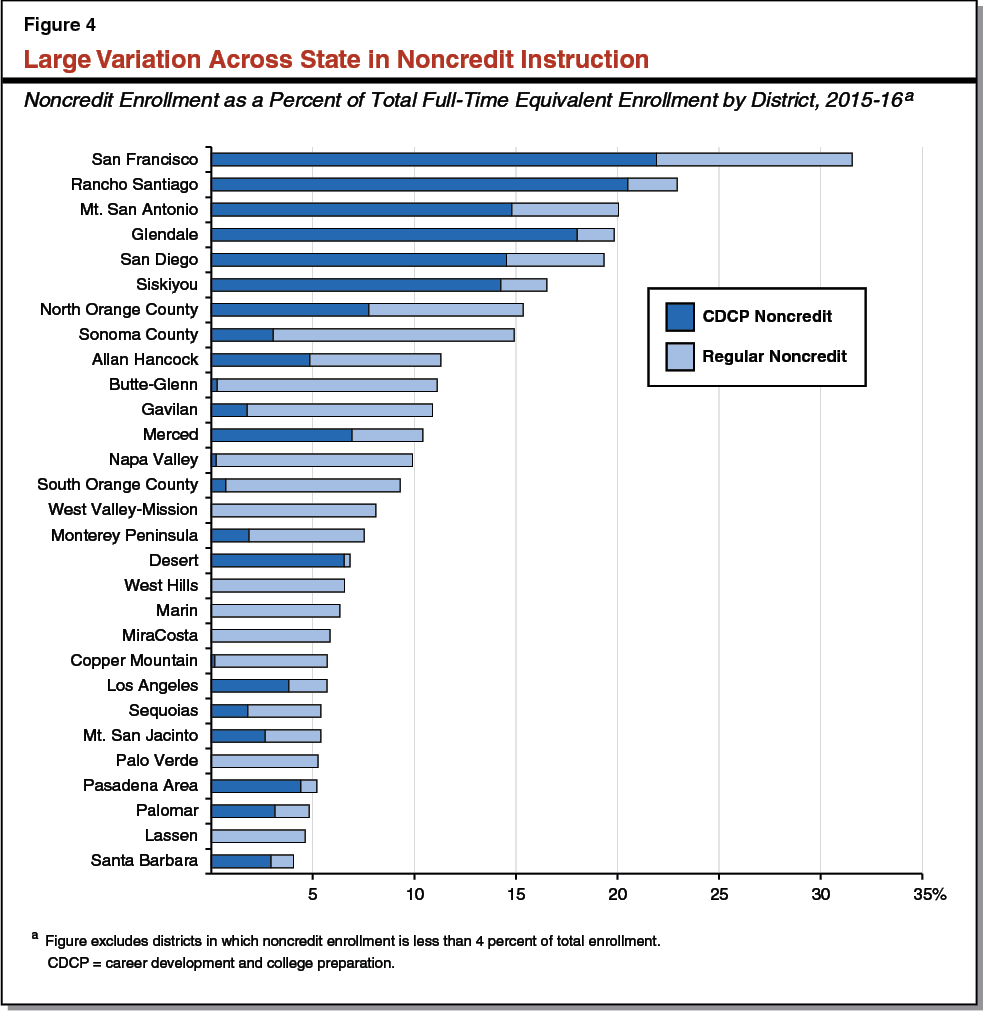

Most CCC Instruction Is Credit. Credit instruction, which all CCCs offer, accounts for 94 percent of full‑time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment and noncredit instruction accounts for 5 percent. (The remaining 1 percent is tutoring.) These proportions vary significantly by community college district. In 2015‑16, for example, the amount of noncredit instruction ranged from 32 percent of FTE student enrollment in the San Francisco Community College District to less than 1 percent in 20 other districts. Such differences typically arise from local agreements dating back many years regarding which types of institutions—schools or community colleges—would provide the majority of adult education.

Within Noncredit, Regular and CDCP Courses

CDCP Is Subset of Noncredit. State law permits community colleges to offer noncredit courses in ten instructional areas, as shown in Figure 2. As the figure shows, four of these instructional areas are eligible for the CDCP designation: elementary and secondary education, ESL, short‑term vocational programs, and workforce preparation (such as communication skills). In addition to being in an eligible instructional area, a course must be offered as part of a sequence of related courses leading to a noncredit certificate (such as certificates in basic reading skills and healthcare careers preparation) to qualify as CDCP.

Figure 2

State Authorizes Noncredit Instruction

In Ten Categories

|

Subjects Eligible for CDCP Funding |

|

|

1 |

Elementary and secondary basic skills and remedial education |

|

2 |

English as a second language |

|

3 |

Short‑term vocational programs |

|

4 |

Workforce preparation |

|

Other Noncredit Subjects (Regular Noncredit) |

|

|

5 |

Parenting education |

|

6 |

Citizenship for immigrants |

|

7 |

Education programs for persons with disabilities |

|

8 |

Education programs for older adults |

|

9 |

Home economics |

|

10 |

Health and safety education |

|

CDCP = career development and college preparation. |

|

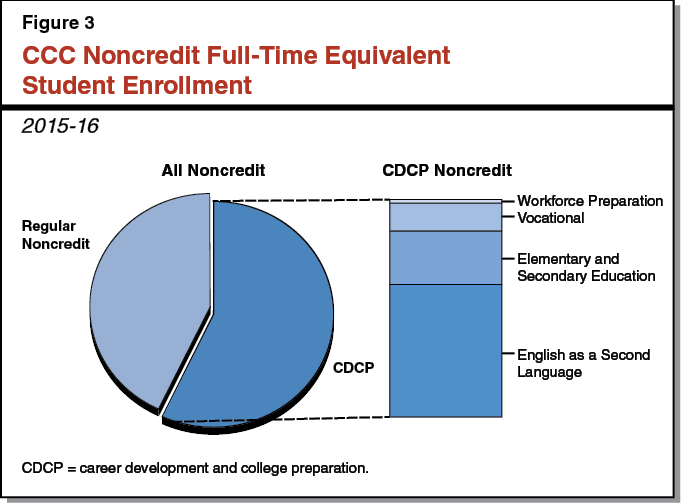

More Than Half of Noncredit Enrollment Is CDCP. In 2015‑16, community colleges served about 68,000 FTE students in noncredit courses, 57 percent of which were in CDCP. Figure 3 shows the share of all noncredit courses that are CDCP and the breakdown within CDCP by instructional area. As the figure shows, the largest instructional areas are ESL and elementary and secondary education, accounting for 61 percent and 25 percent, respectively, of CDCP enrollment in 2015‑16. Vocational courses comprise 13 percent of CDCP enrollment and workforce preparation is 1 percent.

CDCP Share of Noncredit Enrollment Varies Greatly Across Districts. Figure 4 illustrates this variation. Whereas some districts, such as Rancho Santiago, Glendale, Desert, and Pasadena Area, offer almost exclusively CDCP courses in their noncredit programs, others, such as West Valley Mission, West Hills, Marin, and MiraCosta offer only regular noncredit courses.

Differential Funding Rates

Noncredit Instruction Historically Funded at Lower Rate Than Credit. Figure 5 summarizes changes in CCC course funding rates since 2005‑06. Up to and including that year, CCC noncredit courses were funded at a rate comparable to what school districts received for adult education (about $2,000 per FTE student). In 2005‑06, this rate was just under half the average rate for CCC credit instruction. The lower funding rate reflected, in part, generally lower costs for noncredit programs, mainly because of lower pay rates for noncredit faculty. As noted earlier, CCC regulations generally require instructors to possess at least a bachelor’s degree in order to teach noncredit courses (compared to at least a master’s degree for most credit courses). Because faculty pay rates typically are higher for individuals with higher levels of education, noncredit faculty often have had lower pay rates than credit faculty.

Figure 5

CCC Instruction Funding Rates Over Timea

|

Course Type |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2015‑16 |

|

Credit |

$4,189 |

$4,367 |

$5,004 |

|

CDCP noncredit |

N/A |

3,092 |

5,004 |

|

Regular noncredit |

2,057 |

2,626 |

3,009 |

|

aState law sets forth that rates are to be adjusted annually for inflation and other factors. The Legislature adopted additional CDCP rate increases effective in 2006‑07 and 2015‑16. CDCP = career development and college preparation. |

|||

State Enhanced CDCP Funding Rate in 2006‑07. Chapter 631 of 2006 (SB 361, Scott) created the CDCP category and enhanced the funding rate for CDCP courses, among other changes. Specifically, the legislation increased the CDCP rate to 71 percent of the credit rate, compared with 60 percent of the credit rate for regular noncredit instruction.

State Further Increased CDCP Rate in 2015‑16. Eight years after Chapter 631 brought about enhanced funding, Chapter 34 increased the CDCP rate to 100 percent of the credit rate. A one‑year delay from Chapter 34’s enactment to the effective date for the rate increase (July 1, 2015) was intended to give colleges time to implement or expand their CDCP programs, such as by developing new courses and certificate programs, submitting these for state approval, and updating course catalogs.

State’s Rationale for CDCP Rate Increases

Higher Rates Intended as Incentive for Colleges to Offer High‑Priority Courses. Neither Chapter 631 nor Chapter 34 states the Legislature’s intent in raising the CDCP funding rate. Legislative discussions leading up to each law’s passage, however, centered on three main considerations:

- Program Costs. Colleges maintained that noncredit funding rates did not adequately support noncredit vocational programs, a subset of noncredit programs that sometimes have above‑average costs due to expensive equipment, supplies, and facilities, as well as lower student‑to‑faculty ratios.

- Program Quality. Colleges typically have a low share of full‑time faculty in their noncredit programs compared with their credit programs. A college might have, for example, only one or two full‑time instructors and many part‑timers in a noncredit department. The lack of full‑time faculty—who are paid for program planning and other academic activities beyond teaching—can hamper course and program development, faculty coordination, and program oversight. An increased noncredit funding rate, colleges maintained, could facilitate the hiring of more full‑time faculty.

- Financial Incentives. Lawmakers were concerned that—because of the higher funding rate for credit instruction—colleges had a financial incentive to emphasize degree and transfer programs over noncredit adult and vocational education, even if local workforce demand for graduates of noncredit programs went unmet. Equal funding rates would remove this incentive, making it more likely that colleges would offer the types of programs needed to meet workforce needs.

Findings

In this section, we report on changes in CDCP programs, courses, and enrollment since enactment of Chapter 34. Specifically, we present data on three measures: (1) the number of approved CDCP noncredit certificate programs; (2) the number of CDCP course sections (such as Arithmetic 1B on Tuesday and Thursday evenings in fall 2016); and (3) enrollment in CDCP courses. (As noted earlier, CCC measures noncredit student enrollment by students’ daily course attendance. One FTE student equates to a student attending classes 15 hours per week for two semesters.) We also present our findings regarding CDCP funding increases and how colleges have used the new funding and leveraged other CCC funding sources to support their CDCP programs.

Findings Based on Systemwide Data and Interviews With Selected Colleges. For historical context, we examine data beginning in 2006‑07, the first year of enhanced funding for CDCP courses. Our review extends through 2015‑16, the year Chapter 34’s rate increase took effect and the most recent year for which data are available. Because colleges have had only one full year of CDCP funding at the credit rate, we caution against reading too much into the most recent data. To gain a better understanding of campus decisions regarding CDCP instruction, we also interviewed administrative and academic leaders from a number of campuses.

Approved CDCP Certificate Programs

Colleges Created First Noncredit Certificate Programs Following 2006‑07 Funding Increase. Prior to 2006, colleges typically did not offer noncredit certificates. To take advantage of the new CDCP funding rate in 2006‑07, colleges created 254 new certificate programs, as shown in Figure 6. (These programs generally consisted of sequences of related, existing noncredit courses that the colleges identified at the time as CDCP‑eligible.) Growth in the number of new certificate programs continued over the following years but at much lower levels.

Figure 6

Number of New CDCP Certificate Programs

Approved Annually

|

Fiscal Year |

New Programs |

Total Programs |

|

2006‑07a |

254 |

254 |

|

2007‑08 |

87 |

341 |

|

2008‑09 |

58 |

399 |

|

2009‑10 |

67 |

466 |

|

2010‑11 |

39 |

505 |

|

2011‑12 |

31 |

536 |

|

2012‑13 |

11 |

547 |

|

2013‑14 |

19 |

566 |

|

2014‑15b |

40 |

606 |

|

2015‑16 |

47 |

653 |

|

aEnhanced noncredit rate went into effect, funding CDCP enrollment at 71 percent of the credit rate. bCDCP funding rate raised to the credit rate effective in 2015‑16. CDCP = career development and college preparation. |

||

Colleges Developed 87 New Certificate Programs After Passage of Chapter 34—Though One College Skews Total. The pace of approvals accelerated after passage of Chapter 34. During the planning year (2014‑15) and first year of implementation (2015‑16), 20 colleges received approval for 87 new noncredit certificate programs, thereby increasing the total number of approved programs by 15 percent. Of the 20 colleges, most added between one and three certificate programs. One college, however, added 34 programs. This college undertook a complete revision of its adult secondary education program and expanded its vocational offerings. In doing so, the college substantially revised many of its noncredit courses and programs and created a few others. College officials reported that they initiated this process prior to passage of Chapter 34 to improve program quality and outcomes, as well as to take advantage of the previous enhanced noncredit rate. Setting aside this college, growth in the number of approved certificate programs since enactment of Chapter 34 has been modest.

Assortment of New Certificate Programs Approved. Among the programs approved since Chapter 34’s enactment, 44 percent were vocational, 25 percent were ESL, 24 percent were elementary and secondary education, and 6 percent were in other areas. Examples of certificate programs approved in 2014‑15 and 2015‑16 include in‑home support services, graphic design and web skills, general office clerk, starting a small business, and vocational ESL for child care providers.

CDCP Course Sections

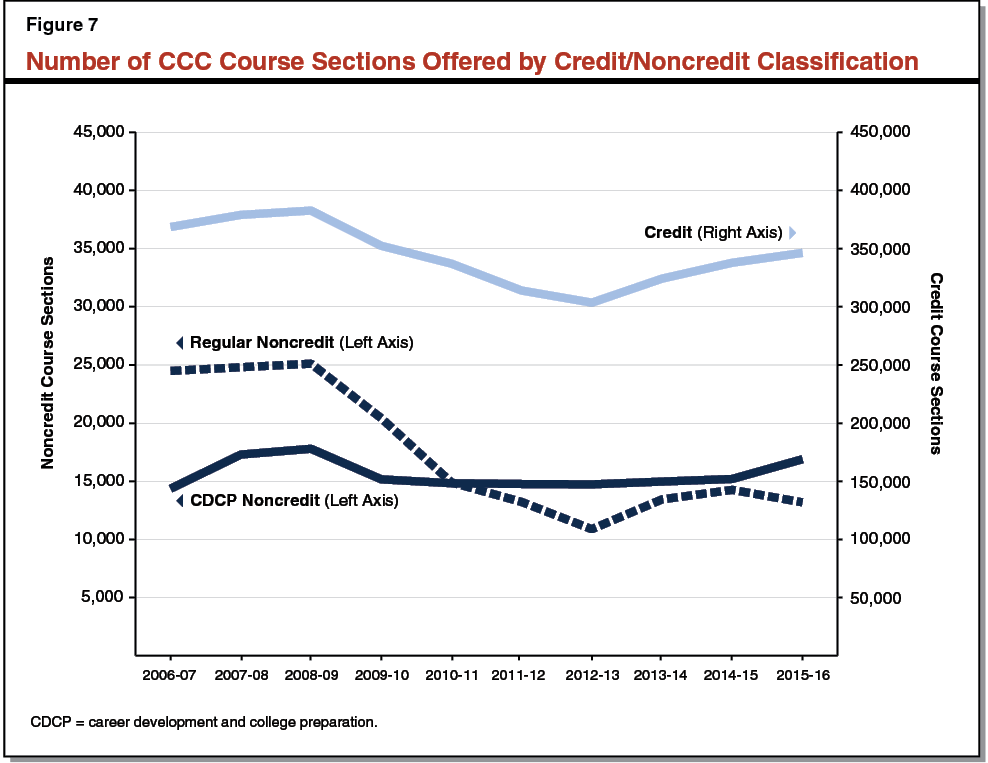

Number of CDCP Course Sections Remained Fairly Flat Through 2014‑15 . . . Despite annual increases in the number of approved CDCP programs, the number of CDCP course sections offered to students did not change much between 2006‑07 and 2014‑15, as shown in Figure 7. By comparison, the number of credit and regular noncredit course sections varied significantly over this period. Specifically, community colleges substantially reduced credit and regular noncredit course offerings in response to the state’s fiscal downturn (2008‑09 to 2012‑13) and substantially increased offerings in these categories after the state budget recovered (2013‑14 to 2014‑15).

. . . Then Colleges Increased CDCP Course Sections by 11 Percent in 2015‑16. The pattern changed in 2015‑16, the first year CDCP enrollment was funded at the credit rate. In that year, as overall funding continued to increase, the number of CDCP course sections increased 11 percent while the number of regular noncredit course sections declined 7 percent compared to 2014‑15. (Credit course sections increased 3 percent in the same year.)

CDCP Enrollment

CDCP Enrollment Has Fared Better Than Regular Noncredit Enrollment. As Figure 8 shows, enrollment in all three instructional categories—credit, regular noncredit, and CDCP—declined from 2007‑08 to 2012‑13 following CCC budget reductions. Regular noncredit instruction declined the most, dropping 46 percent, compared to 22 percent for CDCP and 4 percent for credit. Both credit and CDCP enrollment grew somewhat from 2012‑13 to 2014‑15, while regular noncredit enrollment remained flat. Since 2014‑15, only CDCP enrollment has grown while the other categories have remained flat or declined. Enrollment in CDCP courses has grown from 43 percent of total noncredit enrollment in 2006‑07 (the first year with enhanced funding) to 57 percent in 2015‑16 (the first year with CDCP funded at the credit rate).

Figure 8

Changes in Credit, Regular Noncredit, and CDCP Enrollment During Three Periods

Percent Change in Full‑Time Equivalent Enrollment

|

Credit |

Regular Noncredit |

CDCP Noncredit |

Total Enrollment |

|

|

2007‑08 to 2012‑13 (budget cuts) |

‑4% |

‑46% |

‑22% |

‑6% |

|

2012‑13 to 2014‑15 (budget increases) |

2 |

—a |

5 |

2 |

|

2014‑15 to 2015‑16 (new CDCP rate takes effect) |

—a |

‑2 |

4 |

—a |

|

Cumulative 2007‑08 to 2015‑16 |

‑1% |

‑47% |

‑15% |

‑4% |

|

aLess than 0.5 percent change. CDCP = career development and college preparation. |

||||

CDCP Funding Augmentations

Chapter 34 Resulted in $54 Million in Additional Funding for Districts Offering CDCP. Statewide, apportionment funding in 2015‑16 was $54 million higher under Chapter 34 than it would have been at the previous enhanced noncredit rate (which was 71 percent of the credit rate). Districts with large CDCP programs received substantial augmentations. With CDCP enrollment of more than 6,000 FTE students in 2015‑16, San Diego Community College District, for example, received about $9 million more than it would have received at the enhanced noncredit rate. Rancho Santiago, San Francisco, and Mt. San Antonio College Districts were close behind. Fourteen districts each received at least $500,000 in additional funding compared with what they otherwise would have earned.

CDCP Programs Report Receiving Some of New State Funding. Under current law and regulations, districts have wide discretion on how to allocate apportionment funds. As a result, districts are not required to spend funding generated from CDCP enrollment on CDCP programs. Campus noncredit deans we interviewed, however, report that their divisions have received at least a portion of the new funding. They state that, because CDCP courses now generate as much per‑student funding as credit courses, they are able to make a stronger case for additional faculty positions, instructional technology, and other resources. Because CCC does not have a centralized database of expenditures by program, however, it is unclear how much of the new funding resulting from the Chapter 34 rate increase actually has been spent on CDCP programs and services.

Colleges Report Hiring Some Additional Full‑Time Noncredit Faculty. No systemwide information is available on noncredit faculty hiring for 2015‑16. Most of the colleges we interviewed, however, reported increased hiring in their noncredit programs to accommodate additional CDCP enrollment. Some colleges have converted part‑time positions to full time or created new full‑time positions, whereas others increased their hiring of adjunct instructors. Colleges hiring more full‑time faculty say they expect the new positions to provide more stability for their programs and increase their capacity to develop and improve CDCP offerings.

Other Findings

Several Colleges Report Supplementing CDCP With Other CCC Programs. Several colleges we interviewed have improved their CDCP programs by tapping further resources available through four state categorical programs: the Strong Workforce Program, Student Success and Support Program, Adult Education Block Grant, and Basic Skills Initiative. The state has increased ongoing funding for these programs, which are described in a nearby box, by more than $500 million since passage of Chapter 34. One college we interviewed, for example, stopped offering beginning‑level ESL at its main site so it could focus on redesigning a more advanced ESL certificate program that historically had a poor completion rate. Working within its Adult Education Block Grant consortium, the college arranged with other adult education providers in its region to offer the beginner courses. According to the college, this freed the faculty up to create a more intensive, accelerated certificate program at the advanced level that students could complete in one year (compared to 2.5 years for the old program). The campus reports substantially improved completion rates after implementing the change. Another college reports using Basic Skills Initiative funding to create noncredit courses for students majoring in biology who are assessed as unprepared for college‑level English or math. The students take the CDCP courses concurrently with their major courses, earning a noncredit certificate along the way. Several colleges report using their Student Success and Support Program funds to help provide counseling and guidance to CDCP students.

Additional State Funding Sources for Career Development and College Preparation (CDCP)

In addition to receiving general purpose funding based on the number of full‑time equivalent students in CDCP courses, colleges receive categorical funding for several related activities. Most notably, colleges can use funding from the four displayed programs to provide instruction and support services for CDCP students.

|

CCC Categorical Program |

2016‑17 Funding |

|

Strong Workforce Program. Started in 2016‑17 to expand and improve high‑cost career technical education (CTE) leading to certificates, degrees, and other credentials. Can be used for credit and noncredit CTE programs. |

$200 |

|

Student Success and Support Program. Started in 2013‑14 to expand and improve assessment, orientation, and counseling services for credit and noncredit CCC students. Includes designated funding to identify and address disparities in access and completion for various subgroups of CCC students. Also includes funds for faculty and staff professional development and technical assistance. |

200a |

|

Adult Education Block Grant. Started in 2015‑16 to coordinate services among adult education providers and support CCC noncredit instruction primarily in three areas: (1) English as a second language, (2) high school completion and precollegiate‑level English and math, and (3) vocational education. |

95b |

|

Basic Skills Initiative. Longstanding program to provide counseling and tutoring for students with precollegiate‑level reading, writing, or math skills. Also provides curriculum development and professional development for faculty teaching precollegiate‑level credit and noncredit courses. |

50 |

|

aIncludes student service funding specifically designated for noncredit students, as well as all student equity and professional development funding in the categorical program. bCommunity college share of block grant funding. (Excludes share for school districts and other providers.) |

|

A Few Courses Shifted From Credit to Noncredit. A handful of the colleges we interviewed reported converting precollegiate‑level credit courses to CDCP, though no systemwide data on such conversions is available. In one example, a college began offering ESL courses as both credit and noncredit. Previously, the college had offered the courses only for credit. The courses had low credit enrollment and a large number of students auditing (paying a small fee to sit in on the class). According to the college, many of these students chose not to enroll in the courses for credit because they did not want the courses to affect their grades, course repeatability, credit accumulation, or financial aid status. The change allowed these students to enroll with no fee, provided an opportunity for them to earn a noncredit certificate, and increased overall revenue for the college. In another example, a college shifted lower‑level courses from a credit career technical education program in electronics to CDCP. According to the college, the CDCP courses served as a gateway for students who were hesitant to enroll in a credit program. Taking these courses on a lower‑stakes, noncredit basis allowed the students to explore the career area and earn a noncredit certificate. The college reports that, whereas its credit certificate program in electronics previously had low enrollment and was at risk of closing, the noncredit program has robust enrollment and is encouraging more students to enroll in the associated credit programs as well as helping them gain immediate employment.

Modest Expansion in Higher‑Cost Areas. As discussed earlier, 44 percent of CDCP certificate programs approved since passage of Chapter 34 are in vocational areas. Based on the courses associated with the new vocational programs, we estimate that about one‑quarter of these programs appear to be in areas that might have higher costs due to specialized equipment or limits on class sizes. Examples include computer‑aided design and drafting; multimedia art and animation; and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning certificate programs. One college we interviewed noted that it was developing a CDCP certified nursing assistant program (with a low student‑to‑faculty ratio) to address significant unmet local labor market demand. Another college reports it is developing an industry‑recognized noncredit electrical trainee certificate, noting that it could not have afforded the required laboratory without the higher funding rate (in addition to funding from the Strong Workforce Program).

Little Change in Number of Districts Offering CDCP Instruction . . . Of the state’s 72 community college districts, 37 were offering approved CDCP courses by 2009‑10. Currently, the number of participating districts is 39. Enrollment is highly concentrated, however, in fewer than one‑third of these districts. Eleven districts accounted for 90 percent of all CDCP enrollment in 2015‑16. (This finding reflects the historical pattern of community colleges serving as the primary adult education providers in a few localities.)

. . . But Interest Is Growing. According to colleges we interviewed that have well‑established CDCP programs, many have received numerous requests for assistance in the last year from colleges around the state that want to develop CDCP programs. In addition, the statewide Academic Senate has responded to growing interest by offering workshops on effective practices for developing and implementing CDCP curriculum.

LAO Assessment

Below, we provide our assessment of how CCC’s implementation of Chapter 34 is addressing the Legislature’s concerns about noncredit instruction at the community colleges. We first discuss costs, quality, and incentives related to CDCP instruction. We then turn to data and accountability measures for CDCP programs.

Funding for CDCP Not Well‑Aligned With Actual Costs. As noted earlier, one of the Legislature’s main considerations in enacting Chapter 34 was the cost of vocational programs. Colleges maintained that noncredit funding rates did not adequately support noncredit vocational programs, which sometimes have relatively high equipment, facility, and staffing costs. To date, however, higher‑cost vocational education programs appear to be a small minority of newly approved CDCP certificate programs. As we described, ESL and elementary and secondary education courses—which typically have lower‑than‑average costs due to lower educational requirements for faculty and no need for specialized equipment or labs—account for 86 percent of all CDCP enrollment. As a result, the vast majority of increased CDCP funding is supporting student enrollment in relatively low‑cost courses.

State Provides Separate Funding to Supplement High‑Cost Vocational Programs. To the extent that some CDCP certificate programs—typically in vocational fields—have higher‑than‑average costs, the state now provides separate, ongoing funding to support those costs. As we discussed, the Legislature adopted the Strong Workforce Program beginning in 2016‑17 to provide substantial new funding for vocational education. The Legislature also provided new funding for adult education (which includes vocational education) beginning in 2015‑16. These new programs are intended specifically to offset higher vocational program costs and encourage expansion and improvement in other CDCP instructional areas. The state’s creation of these programs in the years since passage of Chapter 34 raises questions about the continued need for funding CDCP at the credit rate.

Encouraging (Though Early) Signs of Improved Program Quality. Several colleges’ descriptions of improved CDCP coordination with other CCC programs represent an encouraging development. Spurred in part by the increased funding rate for CDCP, colleges are reexamining their noncredit offerings for opportunities to improve and expand them. As part of this process, colleges are bringing together efforts related to student success and equity, workforce education, adult education, and basic skills reform to improve the quality and outcomes of their noncredit as well as credit programs. Improvement in this regard is anecdotal to date, however, and likely falls in the category of promising, rather than widespread, practice.

Chapter 34’s Effect on Faculty Hiring Unclear. In discussing program quality, proponents of Chapter 34 identified the share of full‑time faculty in CDCP programs as a key factor. Several colleges we interviewed report that the higher CDCP funding rate has resulted in their being able to hire more full‑time faculty. Without systemwide data on changes in noncredit faculty, however, it is difficult to gauge the extent of full‑time faculty hiring. Moreover, it is not possible to determine how much of the hiring would have occurred in the absence of Chapter 34, as colleges restore noncredit courses they previously had curtailed due to budget reductions.

Some Evidence That Rate Increase Is Somewhat Improving Colleges’ Use of Noncredit Instruction . . . By eliminating the difference in funding rates between credit and CDCP instruction, the Legislature removed a significant financial incentive for colleges to favor credit over CDCP enrollment. The relative stability of CDCP enrollment (compared to credit and noncredit) over the past decade, and the 2015‑16 uptick in CDCP enrollment after Chapter 34’s rate increase took effect, suggest that colleges are responding to the changed incentive. Moreover, the shifting of a few courses from credit to noncredit, as related in our interviews, suggests that at least some colleges have begun to offer courses in the category most appropriate for the subject matter and student population.

. . . But Mostly Among Colleges That Already Were Offering CDCP Instruction. The minimal change in the number of colleges offering CDCP suggests that the higher funding rate primarily is encouraging existing providers to expand their programs rather than attracting additional colleges to offer CDCP instruction. This may be starting to change, though, as additional colleges have expressed interest in developing CDCP programs since passage of Chapter 34.

Limited Data and Accountability Measures for CDCP Programs. As evident throughout the findings section of this report, limited information currently is available about community college CDCP programs. Data on noncredit faculty hiring and shifts in course offerings from credit to noncredit are anecdotal, based on interviews. Colleges do not report individual course or program costs. The CCC Student Success Scorecard measures completion of certificates, degrees, or transfer within six years for students who initially enrolled in CDCP courses, but the Salary Surfer, which shows earnings of certain CCC graduates, as well as CCC’s basic skills outcomes tracking tool, exclude noncredit students. Most concerning, there currently is no statewide data to assess the value of the 653 CDCP certificate programs created to date. Though some of these (such as programs leading to nursing assistant and welding certificates) likely have immediate workforce value to students, the benefit of others (such as a program leading to a certificate in “number arithmetic” or one in basic skills world history) is much less obvious. CDCP funding rules, which require a sequence of related courses leading to a certificate, arguably could encourage colleges to create certificate programs with unproven value to students.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Below, we highlight four questions for the Legislature to consider as it makes decisions on CCC course funding going forward.

Should the Legislature Revisit CCC Course Funding Rates? The Legislature adopted Chapter 34 in 2014 to increase course funding rates for vocational and other high‑priority categories of noncredit instruction. Since then, the Legislature has provided substantial new funding for the same categories of instructional programs through the Strong Workforce Program and Adult Education Block Grant. Given this overlap, does funding CDCP enrollment at the credit rate still make sense? Moreover, what are the Legislature’s expectations regarding the relationship of CDCP programs with these other initiatives, as well as the Student Success and Support Program and Basic Skills Initiative?

Should the State More Clearly Delineate the Roles of Credit and Noncredit CCC Instruction? Were the state to fund credit and CDCP instruction at different rates in the future, it would need a clearer distinction between the two categories. In our 2012 report, Restructuring California’s Adult Education System, we recommended the Legislature restrict credit instruction in English and ESL to transfer‑level coursework, such that colleges would offer precollegiate‑level courses in those disciplines on a noncredit basis. We also recommended the Legislature restrict credit math instruction to courses at or above the level of Intermediate Algebra, and make math courses below that level noncredit. In addition, we recommended the Legislature convene a work group to clarify the definitions of credit and noncredit vocational instruction. The Legislature could revisit these recommendations in the context of Chapter 34 and colleges’ subsequent expansion of CDCP instruction.

Should the State Encourage Expansion of CDCP (or Regular Noncredit) Instruction to Additional Districts? Though Chapter 34 appears to have expanded enrollment opportunities for students in districts that already were providing CDCP instruction, to date it has had little effect on expanding access to other areas of the state. Colleges may have valid reasons for not offering CDCP and regular noncredit courses. In some areas, for example, other education providers might already be offering robust adult education programs that meet the community’s needs and at much lower funding rates. The Legislature could ask the Chancellor to review the regional adult education consortia plans to determine whether other providers are addressing local needs in areas where community colleges provide little or no noncredit instruction. If the Legislature wished to expand access to CDCP instruction to more areas of the state, it could then direct the Chancellor’s Office to provide additional guidance to colleges interested in developing CDCP programs.

How Should the State Measure the Effectiveness of CDCP Programs? With continued growth in the number of—and enrollment in—CDCP certificate programs, a better understanding of the value of these programs to students and the state is increasingly important. The Legislature could direct the Chancellor’s Office to include noncredit students in existing or new adult and workforce education performance measures. Program‑specific completion rates and workforce outcomes (such as employment and earnings) for students in noncredit certificate programs could be especially valuable to policymakers and prospective students.

Conclusion

Overall, we find that Chapter 34 has had some of the effects the Legislature intended—such as leading to some expansion of higher‑cost noncredit programs, improving the organization and potentially the quality of CDCP instruction, and expanding enrollment in CDCP courses. These conclusions are preliminary, however, given that only one year of data is available following implementation of Chapter 34. Moreover, expansion has not been targeted to key areas, as the state provides the new funding rate for all CDCP enrollment, including in low‑cost and previously existing certificate programs. Additionally, legislative and budget developments since passage of Chapter 34 raise new questions about how best to support CCC noncredit instruction. Also, a previous issue regarding lack of delineation between credit and noncredit instruction remains unresolved, and the state has limited data to evaluate the effectiveness of CDCP programs. By considering these issues as it makes future policy and funding decisions, we believe the Legislature could improve the effectiveness of noncredit instruction in meeting the needs of the state and its community college students.