LAO Contact

September 6, 2017

Measuring CalWORKs Performance

- Introduction

- Background

- Measuring Program Performance: Why and How?

- Performance Measurement in CalWORKs Today

- Overview of Cal‑OAR

- Issues for Consideration

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program represents one of the state’s major efforts to assist low‑income families with children. This report examines the state’s approach to assessing the performance of CalWORKs, in light of recent legislative action to establish a new framework for performance measurement in the program.

Measuring Program Performance: Why and How?

Various Rationales for Performance Measurement. There are several rationales for the Legislature to engage in performance measurement, including to (1) evaluate whether a program is meeting its objectives, (2) verify whether program implementation is consistent with legislative intent, (3) communicate statewide priorities for a program, and (4) encourage continual improvement in program performance.

What Can Be Measured? There are three main types of information that can be measured when assessing a program’s performance—inputs, processes (also referred to as outputs), and outcomes. Inputs represent the resources provided for a program to operate, processes refer to the specific activities undertaken in a program, and outcomes refer to the results of a program—the objectives the program is intended to achieve.

Ideally, Performance Measurement Should Focus on Outcomes. In practice, there are a variety of practical issues that arise in meaningfully measuring outcomes. However, when approached with appropriate caution, including outcomes in performance measurement puts the focus on a program’s end goals, rather than simply on the processes used to try to achieve those goals.

Performance Measurement in CalWORKs Is Relatively Limited

Federal Work Participation Rate (WPR) Is Driving Factor in Current Performance Measurement. Currently, performance measurement in CalWORKs is relatively limited and emphasizes the WPR, the federal government’s only performance measure for the program. This emphasis largely results from fiscal penalties the state and counties face if federal targets for the WPR are not met. At the same time, the state has enacted policies in CalWORKs that reflect priorities beyond the WPR, some of which have the potential to work at cross‑purposes with meeting federal targets. This creates the need to balance state priorities with the federal WPR requirement.

Beyond WPR, Current Reporting Emphasizes Process. Beyond the WPR, data reported on the CalWORKs program emphasize processes over outcomes. The state has made some attempts to increase the focus on outcomes in performance measurement in the past. However, for a variety of reasons, including past fiscal challenges, these efforts are currently not fully implemented.

Legislature Recently Enacted New Performance Measurement System

In recent budget legislation, the Legislature established a framework for a new performance measurement system for CalWORKs, to be known as the CalWORKs Outcomes and Accountability Review (Cal‑OAR). Under Cal‑OAR, data on various performance indicators will be collected and published and counties will regularly undergo self‑assessment and develop system improvement plans with targets for the performance indicators. Budget legislation directs the Department of Social Services to convene a workgroup beginning in the fall of 2017 to develop plans for how Cal‑OAR will operate.

Issues for Consideration

In concept, we think that Cal‑OAR will significantly increase performance measurement in CalWORKs and has the potential to place greater emphasis on outcomes. We outline several issues for consideration by the workgroup and the Legislature as planning and implementation of Cal‑OAR progress in coming months and years.

Aligning Cal‑OAR Performance Measures With Other Federal Workforce Programs. In choosing a set of performance measures for Cal‑OAR, we suggest that the workgroup give priority consideration to “common measures” used in federal workforce programs authorized by the Workforce Opportunity and Innovation Act. These common measures are consistent with the goals of CalWORKs and including these measures in Cal‑OAR would increase the consistency with which performance is measured across workforce programs in the state.

Taking Steps to Account for Other Local Factors That Affect Outcomes. As a way to address some of the practical challenges of outcome measurement, some programs use statistical techniques to adjust program performance and set targets to reflect local conditions that are beyond the program’s control. As it plans for meaningful outcome measurement in Cal‑OAR, the workgroup could consider what role similar statistical adjustments might play in CalWORKs. We identify several potential ways such techniques could be used.

Balancing State and Federal Priorities in Cal‑OAR. As a way of striking a balance between federal and state priorities in CalWORKs, the workgroup could consider including the WPR as one performance measure in Cal‑OAR, alongside other measures that align more directly with state priorities. Additionally, the Legislature may wish to consider revisiting county fiscal penalties associated with the WPR in the future and consider ways to account for both Cal‑OAR performance measures and the WPR.

Creating More Uniform County Data Collection and Reporting. Much of the data on CalWORKs are housed in one of three automation systems used by counties to administer the program. Due to recent federal guidance, counties will be moving to a single automation system by 2023. We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to report on how the transition to a single automation system will increase uniformity of data collection and streamline data sharing between the state and counties.

Cleanup Needed to Align Past Actions With Cal‑OAR. Once implemented, Cal‑OAR will overlap with some previous actions taken by the Legislature related to performance measurement in CalWORKs, requiring cleanup to address aspects of these previous actions that are now redundant or unnecessary.

Introduction

CalWORKs Assists Very Low‑Income Families With Children. The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program represents one of the state’s major efforts to assist low‑income Californians, specifically families with children. During 2016‑17, the program served an average of nearly 460,000 families each month, with almost 880,000 children receiving assistance. With $2.8 billion in estimated spending from state and local funding sources during the same year (and an additional $2.4 billion in federal spending), CalWORKs represents a significant allocation of the state’s resources. Legislative oversight of the CalWORKs program’s effectiveness is important to promote the best possible outcomes for CalWORKs recipients and the efficient use of state resources.

Performance Measurement in CalWORKs Is Relatively Limited. Currently, performance measurement in CalWORKs is relatively limited, and largely focuses on processes involved with the program’s operation—particular emphasis is given to a federal performance measure known as the “work participation rate” (WPR)—rather than on the program’s end results, or outcomes.

Recent Budget Legislation Creates CalWORKs Outcomes and Accountability Review (Cal‑OAR). As part of the human services trailer bill of the 2017‑18 budget package, Chapter 24 of 2017 (SB 89, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), the Legislature adopted a framework for a new performance measurement and accountability system for CalWORKs that will be known as Cal‑OAR. In this report, we outline the rationales for measuring program performance and what kinds of things can and ideally should be measured. We then provide an overview of the current approach to performance measurement in CalWORKs as well as the major features of Cal‑OAR. Finally, we raise several issues to be considered as the Cal‑OAR system is further developed and implemented in the coming years.

Background

CalWORKs Provides Monthly Cash Grant and Welfare‑to‑Work Services. The CalWORKs program provides financial assistance in the form of a monthly cash grant to families with children whose income is inadequate to meet their basic needs. Unless they qualify for an exemption (for example, to care for a disabled family member), adults in CalWORKs cases are generally subject to a requirement that they be employed or participate in specified activities—known as “welfare‑to‑work activities”—intended to lead to employment. Individuals subject to the work requirement are entitled to receive services to help meet the requirement, including subsidized child care and reimbursement for transportation and certain other expenses. Adults enrolled in CalWORKs are limited to a lifetime maximum of 48 months of assistance. Once adults in a case reach this limit, the children in the case may continue to receive a monthly cash grant, but that grant is reduced by the adults’ portion.

Counties Are Responsible for Local CalWORKs Administration. The CalWORKs program is locally administered by the state’s 58 counties. The California Department of Social Services (DSS) oversees operations in the counties. While some aspects of county CalWORKs programs are required by law, such as subsidized child care, counties do have flexibility in what types of welfare‑to‑work activities and other services are offered to CalWORKs participants. For example, not all counties operate programs that place CalWORKs participants in jobs where the wages are partially or fully covered by the program, commonly referred to as “subsidized employment.”

Counties Rely on One of Three Automation Systems to Administer CalWORKs. To perform eligibility determinations and other administrative functions in CalWORKs (as well as other major health and human services programs), counties rely on one of three automation systems, each of which serves a consortium of counties. These three automation systems house most of the data that are currently reported to the state on the CalWORKs program. The state is currently in the process of reducing the number of automation systems from three down to two, a process expected to be completed by 2020. Recently, federal agencies mandated that the state migrate all counties to a single statewide automation system by 2023 in order for the federal government to continue to contribute funding for a portion of the systems’ maintenance costs.

CalWORKs Implemented in Response to Creation of Federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Program. CalWORKs was created in 1997 in response to the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation that created the federal TANF program. The federal TANF program provides flexible block grant funding to states to implement programs that are consistent with the federal goals for TANF, described below.

State and Federal Goals for CalWORKs. State law establishes the first goal of the CalWORKs program to be reducing child poverty, followed by achieving the four goals of the federal TANF program, listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1

State and Federal Goals for CalWORKs

|

State Statutory Goals of CalWORKs |

|

|

|

|

Federal TANF Goals |

|

|

|

|

|

TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

Federal Performance Requirements for TANF Limited to the WPR. One of the relatively few requirements the federal TANF program places on states is that, at a minimum, 50 percent of families that receive assistance must be working or engaged in welfare‑to‑work activities for a minimum number of hours each week. (For two‑parent families, federal law specifies a higher minimum requirement of 90 percent.) Federal law outlines which activities are allowable in order for a family’s participation to count toward the requirement. The state is free to define different rules for allowable welfare‑to‑work activities (as described later on, California has defined different rules for allowable activities), so long as the percentage of families meeting the participation requirement by engaging in activities allowable under federal law exceeds the minimum threshold. This requirement—referred to as the WPR requirement—represents the primary federal performance measure for state TANF programs. States that fail to comply with the WPR requirement may face fiscal penalties in the form of reductions in TANF block grant funding that grow with each successive year of noncompliance. For states that face penalties, federal law outlines administrative processes for states to appeal the penalty amount, claim good cause for noncompliance, or enter corrective action plans to reduce or eliminate penalty amounts before they are enforced.

Measuring Program Performance: Why and How?

In this section, we describe the reasons performance measurement in public programs like CalWORKs is worth pursuing and discuss some of the ways that performance measurement can be implemented.

Rationales for Performance Measurement

There are several rationales for the Legislature to engage in measuring program performance, as described below.

To Evaluate Whether the Program Is Meeting the Legislature’s Objectives. All state programs are intended to meet certain objectives or address certain problems. Measuring the extent to which a program is meeting its objectives is central to the Legislature’s ability to identify and make changes to the program to increase its effectiveness or, in some cases, discontinue the program if it is determined that it cannot meet its objectives. For example, in the case of CalWORKs, the Legislature has an interest in understanding whether the program achieves the intended outcomes of reducing child poverty and reducing the dependence of needy parents.

To Verify Whether Program Implementation Is Consistent With Legislative Intent. In addition to establishing the objectives of a program, the Legislature sometimes specifies how those objectives should be pursued. Performance measurement can help the Legislature assess whether a program has been implemented in a manner that is consistent with state law and legislative intent. For example, state law specifies that CalWORKs participants are entitled to receive child care subsidies to enable them to meet the program’s work requirement. As a result, the Legislature may wish to measure the extent to which CalWORKs participants have access to child care subsidies.

To Communicate Statewide Priorities for the Program. State programs often have multiple objectives. Measuring performance relative to a particular objective will tend to focus attention on that objective. The Legislature’s choice of which objectives are measured and how they are measured can play a role in communicating which objectives should take the highest priority. For example, as has been noted, the WPR is the federal government’s primary performance measure for state TANF programs. As will be discussed in more detail later, the state’s priorities, as reflected in CalWORKs policies, do not always align with the WPR. However, the absence of performance measures related to these state priorities means that the state and counties have tended to focus attention on the WPR and the federal priorities it represents, potentially to the detriment of state priorities.

To Encourage Continual Improvement in Program Performance. Performance measurement can be used to encourage continual program improvement if it is paired with goalsetting processes that establish reasonable targets for performance, identify specific actions to take to achieve those targets, and measure progress toward meeting targets.

What Can Be Measured?

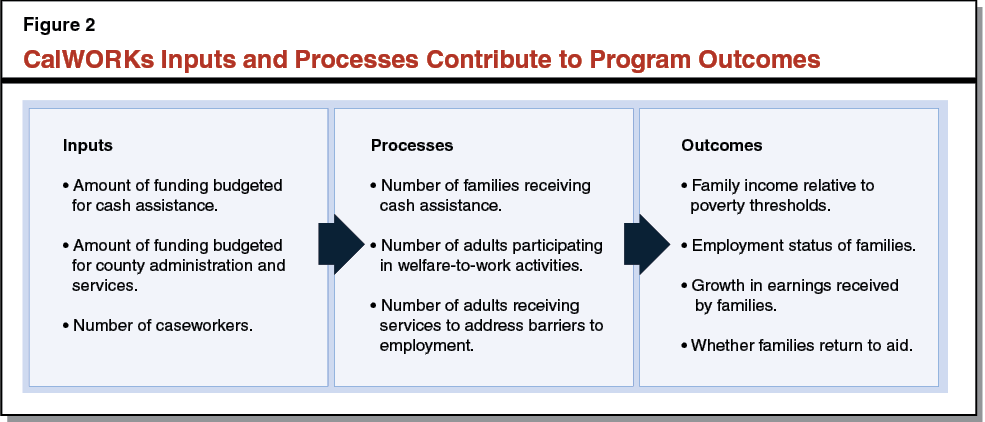

In general, there are three main types of information that can be measured when assessing a program’s performance—(1) inputs, (2) processes (also referred to as outputs), and (3) outcomes. These three key types of program information are interrelated, as shown in Figure 2.

Inputs. Inputs are the resources provided for a program to operate. For example, in the CalWORKs program, inputs include things like funding provided for cash grants; funding provided for county administration of the program; and the caseworkers, facilities, and contracted services paid for with these funds. Input measures quantify program components like funding and staff, and often appear in budgetary documents. Input measures provide some information about how the program is operating but little to no information about whether it is meeting its objectives. When considered with outcomes, inputs can play a critical role, however, in assessing how efficiently the program is operated, by identifying the resources required to achieve observed results.

Processes. Processes refer to the specific activities undertaken by the program that are intended to achieve the program’s objectives. Processes can be thought of as the operations of the program that are made possible through the inputs provided. Process measures quantify these program operations. Examples of process measures include things like the number of families receiving cash assistance, the number of adults participating in various welfare‑to‑work activities, or the number of children enrolled in subsidized child care. Like inputs, processes are relatively easy to quantify. Process measures also provide information about how a program is operating, but generally do not provide direct information about whether a program is meeting its objectives.

Outcomes. Outcomes refer to the results of the program—the objectives the program is intended to achieve. For example, some outcome measures for CalWORKs might include the income of families relative to poverty thresholds following their participation in the program, their employment status, growth in their wage levels, and the extent to which families return to assistance in the future. Outcome measures are most directly related to answering whether a program is working as intended to achieve its objectives. Given the Legislature’s overarching interest in assessing whether programs are meeting their objectives, performance measurement in public programs should ideally focus on outcomes. However, as we describe below, there are a variety of issues in meaningfully measuring these outcomes.

Outcome Measurement Can Present Challenges . . .

Data on Outcomes Not Always Readily Available. One challenge associated with outcome measurement is that data on desired outcomes are not always available. For example, as mentioned previously, the first goal of the CalWORKs program is to reduce child poverty in the state. Measuring child poverty requires relatively detailed information on families’ circumstances and resources. However, services provided in CalWORKs to improve participating families’ employment and earnings may take effect gradually over time, including after a family is no longer participating in the program. Once a family leaves the program, much less detailed information on the family’s situation is collected. This constrains the state’s ability to measure whether the family or the children are in poverty, or how a family’s income changes relative to poverty thresholds over time.

Outcomes Are Affected by Factors Other Than the Program . . . Even when data are available, another significant challenge with outcome measurement is that outcomes are generally affected by other factors in addition to the program’s operation. For example, whether a family enrolled in CalWORKs obtains employment that pays high enough wages for the family to no longer require assistance depends not just on services received through CalWORKs, but also on the characteristics of the family (such as level of education and health status) and on conditions in the labor market. Families with higher levels of education, better health, and who reside in an area with a strong local labor market with relatively abundant employment opportunities are more likely to have a positive employment outcome than a family with lower levels of education, poorer health, and living in an area with a weak labor market. This is true regardless of whether the family participates in CalWORKs.

. . . Making It Challenging to Directly Link Program Operations to Outcomes . . . The presence of other factors that affect program outcomes can make it difficult to distinguish the role of the program from the role of other factors in bringing about the observed outcome. For example, if a family obtains employment with high enough wages to allow the family to leave CalWORKs assistance, this would typically be considered a positive outcome. However, it may not be clear whether the positive outcome came about because the family had above‑average skills, because of improving conditions in the local labor market, because the CalWORKs program helped the family address barriers to employment, or some combination of all three. This means that, in general, measured outcomes cannot necessarily be fully attributed to the program, since other factors likely played some role as well. These challenges are compounded as time passes after a family leaves CalWORKs, since the extent to which other factors will affect outcomes for families increases over time. As a result, measuring long‑term outcomes is particularly challenging.

. . . Or Compare Outcomes Across Jurisdictions. The presence of other factors that affect program outcomes also makes it challenging to compare outcomes across counties. This is because the differences in outcomes between two counties may be due to actual differences in the effectiveness of the respective counties’ programs, or differences in the labor markets and participant characteristics between the two counties, or a combination of both. For example, a county with a weak local labor market and a caseload with relatively significant barriers to employment—factors beyond the county’s control—may have worse employment outcomes for CalWORKs participants than a county with a strong local labor market and a caseload with relatively fewer significant barriers to employment, even if the CalWORKs programs in the counties are operated similarly.

. . . But Adds Value When Approached With Appropriate Caution

In light of the challenges described above, performance measurement in many programs, including CalWORKs as we describe below, tends to focus on processes rather than on outcomes. However, outcome measurement remains important because measuring outcomes puts the focus on the program’s end goals, rather than simply on the processes used to try to achieve those end goals. When data are available, including outcomes as a part of program performance measurement helps the Legislature to track outcomes for families in the program and allows program administrators to consider how program administration might be changed to improve outcomes. This is done recognizing that there will always be some uncertainty in the extent to which the program is responsible for observed outcomes or how changes in program administration affect outcomes. Given this uncertainty, outcome measurement is most useful when it is done in conjunction with the measurement of processes that are expected to lead to desired outcomes and are naturally more directly under the program’s control. Additionally, as will be described in greater detail later, steps can be taken to adjust for the effect of other factors, potentially making it easier to measure program performance relative to outcomes and make comparisons across jurisdictions.

Performance Measurement in CalWORKs Today

Federal WPR the Driving Factor in CalWORKs Performance Measurement

Potential for Fiscal Penalties Focuses Attention on WPR. As noted previously, the WPR is the only required federal performance measure for state TANF programs. The prominence of the WPR, and the fiscal penalties attached to noncompliance, have made it a driving factor in the state’s approach to performance measurement in CalWORKs. To meet federal requirements, the state devotes significant resources to tracking the WPR at both the state and county level. Additionally, state law specifies that, in the event that the federal government imposes a penalty on the state for failure to comply with the WPR requirement, the state will share any penalty equally with those counties that contributed to the state’s failure to meet the WPR requirement. In other words, 50 percent of any penalty amounts ultimately imposed on the state for failure to meet the WPR requirement would be passed on to counties that did not themselves meet the federal WPR requirement. This provision is intended to motivate counties to assist the state in its efforts to comply with the WPR requirement.

State Has Failed to Meet WPR Requirement in Past Years, but Recently Came Into Substantial Compliance. Due to a variety of factors, California has consistently failed to meet the WPR over much of the past decade. This has resulted in a significant amount of penalties (a total of $1.8 billion) being assessed—but not yet enforced—on the state. However, as a result of certain actions taken by the state and by taking advantage of administrative remedies available in federal law, the state has now achieved substantial compliance with the WPR requirement, has already received relief from more than $1 billion of the total penalties, and is on track to eliminate the majority of the remaining penalties that have been assessed. We describe some of the major steps—most of them administrative—the state has taken to reach substantial compliance in the box below. Currently, the state is estimated to be exceeding the overall WPR threshold that applies to all families by several percentage points. (We note that the state continues not to meet the separate WPR threshold for two‑parent families, leaving the state subject to some penalties. However, penalties for noncompliance with the two‑parent requirement are much smaller than penalties for noncompliance with the all‑families requirement, since two‑parent families make up a relatively small share of all families receiving assistance.)

State Strategies to Address Work Participation Rate (WPR) Noncompliance

History of California WPR Compliance. California failed to meet the all‑families WPR threshold for federal fiscal years (FFYs) 2006‑07 through 2013‑14 and, as shown in the figure below, has failed to meet the two‑parent WPR threshold since FFY 2011‑12. In recent years, the state has taken several steps to address WPR noncompliance. As a result of these steps, the state achieved compliance with the all‑families requirement in 2014‑15 but remains out of compliance with the two‑parent requirement.

Steps to Alter Who Is Counted in WPR Calculation. Of all the actions the state took to reach substantial compliance, the most significant involved administratively adding households to the WPR calculation that are not enrolled in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program but that are employed with enough hours to meet the federal the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) work requirement. This is done by using state CalWORKs funds to provide a modest supplemental food benefit, referred to as the Work Incentive Nutrition Supplement (WINS), to working families that are enrolled in CalFresh but do not receive regular CalWORKs benefits. Because the WINS benefit is funded with CalWORKs funds, families that receive it are included in the state’s WPR calculation. The state also took steps to fund regular CalWORKs benefits for certain families that are unlikely to meet the federal TANF work requirement with non‑CalWORKs funding, effectively removing these families from the WPR calculation. Taken together, these steps account for most of the increase in the state’s all‑families WPR from 2013‑14 to 2014‑15.

Steps to Increase Participation in Federally Allowable Activities. In addition to changing which families are included in the WPR calculation, the state and counties have made efforts to improve the engagement of CalWORKs participants in activities that meet the federal work requirement. For example, in 2013 the state approved additional funding for subsidized employment, which is an allowable activity (counts toward the WPR requirement) under federal law.

Recent History of California WPR Compliance

Federal Fiscal Year

|

2010‑11 |

2011‑12 |

2012‑13 |

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

|

|

All‑Families WPR |

||||||

|

Required ratea |

29.0% |

50.0% |

50.0% |

50.0% |

50.0% |

50.0% |

|

Actual rate |

27.8 |

27.2 |

25.1 |

29.8 |

55.7 |

60.7b |

|

Met requirement? |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Two‑Parent WPR |

||||||

|

Required ratea |

— |

90.0% |

90.0% |

90.0% |

90.0% |

90.0% |

|

Actual rate |

33.9% |

30.8 |

30.9 |

25.5 |

61.4 |

69.9b |

|

Met requirement? |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

aCalifornia’s effective required rates were reduced in 2010‑11 (including down to zero percent for two‑parent families) due to a federal credit for past caseload reductions. bPreliminary. WPR = work participation rate. |

||||||

State Priorities Diverge From Federal Priorities, Requiring Balance

At the same time the state has worked to come into compliance with the WPR requirement, the state has enacted policies that reflect priorities beyond simply meeting the federal WPR thresholds. In particular, significant changes made in recent years have broadened the focus of the program.

State Made Significant Changes to CalWORKs in 2012 and 2013. In 2012, the Legislature enacted a significant change to the state rules that govern allowable welfare‑to‑work activities. Specifically, the state rules were altered to provide greater flexibility in what counts as an allowable welfare‑to‑work activity for a period of 24 months, allowing participants to engage in activities and receive services that best align with addressing their barriers to employment. Because these state rules differ from federal rules for allowable welfare‑to‑work activities, families taking advantage of the flexibility afforded during this period might not count toward the state’s WPR requirement. Once 24 months of assistance under the more flexible state rules are exhausted, adult recipients may continue to receive assistance but are required to participate under the federal welfare‑to‑work rules, which are relatively less flexible and generally have a heavier emphasis on employment, as opposed to education, training, and other activities intended to remove barriers to employment. A family’s participation under the federal rules generally would count toward meeting the state’s WPR requirement.

In 2013, the Legislature enacted further changes to CalWORKs related to welfare‑to‑work. The first of these was requiring the development of a standardized appraisal, known as the Online CalWORKs Appraisal Tool (OCAT), which is used with all new CalWORKs participants to identify potential barriers to employment before they begin welfare‑to‑work. The second was the creation of the Family Stabilization program within CalWORKs, which provides intensive case management and additional services (depending on the administering county) intended to help CalWORKs participants experiencing a crisis situation that would hinder full participation in welfare‑to‑work. Additional funding for subsidized employment was also approved at this time. Taken together, these changes increase the program’s emphasis on identifying participants’ barriers to employment early and provide the potential for additional flexibility in activities and services to address them.

Some State Policies Potentially Work at Cross‑Purposes With Meeting WPR Requirement, Creating Need for Balance. Some of the policies described above have the potential to work at cross‑purposes with meeting the WPR requirement. In particular, the 24‑month time clock allows CalWORKs recipients to participate in activities that do not necessarily count toward meeting the WPR. This has required implementing the 24‑month time clock in such a way as to balance the state priority of providing flexibility against the federal priority of having enough participants in federally allowable activities to meet required WPR thresholds. We note that the actual effect of implementing the 24‑month time clock on the WPR is unclear at this time, but is one subject of an evaluation of recent program changes that is due to the Legislature by January 2018. Additionally, actions taken in recent years to reach substantial compliance with the WPR requirement have provided a certain degree of “cushion” to allow the state to implement policies consistent with its priorities that might negatively affect the WPR. Despite this, because meeting the WPR is a federal requirement, the need to maintain balance between state priorities and meeting the WPR requirement will continue into the future.

Beyond WPR, Current CalWORKs Reporting Emphasizes Process

Monthly Reporting on Caseload Characteristics, Participation Rates, and Certain Limited Outcomes. Chapter 270 of 1997 (AB 1542, Ducheny), the legislation that established CalWORKs, required DSS to develop and implement a system of performance monitoring that would: (1) look at the extent to which the state and counties were achieving the program’s goals, (2) evaluate whether negative outcomes were occurring, and (3) identify any needed adjustments to the program. Chapter 270 also required DSS to periodically publish data reported by counties on caseload characteristics and welfare‑to‑work outcomes. Pursuant to these requirements, counties report on various aspects of program operations including the number of families receiving cash assistance, the number of individuals participating in each of the allowable welfare‑to‑work activities, the number of individuals receiving mental health or substance abuse services, the number of individuals who obtain employment, the number of cases discontinued from assistance due to increased earnings, and the wages of current CalWORKs participants. Most of the data points currently reported are process‑oriented. Other reported information, such as the number of individuals who obtain employment, the number of cases discontinued from assistance due to earnings, and the wages of current CalWORKs participants, are more outcome‑oriented.

State Has Previously Made Attempts to Promote Greater Outcome Measurement and Accountability

Following a reauthorization of the federal TANF program in 2005, the Legislature enacted additional performance measurement and accountability policies largely intended to increase the state’s performance relative to the WPR requirement.

Pay for Performance Incentive System Enacted . . . The first of these performance improvement policies is the Pay for Performance program, enacted by Chapter 78 of 2005 (SB 68, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). Under this program, counties may receive incentive funding on top of funding for regular program operations if they achieve certain benchmarks relative to specified performance measures. When Pay for Performance was enacted, the measures initially included (1) the percentage of current CalWORKs cases that had employment, (2) a county‑specific WPR, and (3) the percentage of participants with earnings one quarter after leaving assistance. A fourth measure—the percentage of CalWORKs participants with earnings sufficient to receive the maximum benefit from the federal earned income tax credit—was added later. In order to receive incentive funding from the Pay for Performance program, counties would either have to make a minimum level of improvement on a given performance measure or rank in the top 20 percent of counties. Incentives funds were required to be spent in the CalWORKs program.

. . . But Never Funded. After the Pay for Performance program was enacted, $40 million that was initially appropriated for incentive payments was reverted to achieve budgetary savings and no counties received an incentive payment. No funding has been appropriated for incentive payments since that time. As required by law, DSS published county performance relative to Pay for Performance measures beginning in 2005, but stopped publishing the measures (except for county WPR) around 2010.

County Peer Review (CPR) Process. The second change to performance measurement and accountability in CalWORKs was the creation of the CPR process, enacted by Chapter 75 of 2006 (AB 1808, Committee on Budget). Under this process, each county is periodically visited by representatives from DSS and peer counties to review the county’s performance on existing performance measures, including the federal WPR and Pay for Performance measures, and receive technical assistance. From 2007 through 2010, eight CPRs were conducted. With each CPR, DSS issued a report summarizing what was covered during the visit and identifying both challenges and promising practices for the visited county. The CPR process was temporarily discontinued in 2010 and reinstated in 2013. Since that time, the emphasis of county visits has shifted to oversight of implementation of CalWORKs reforms enacted in 2012 and 2013.

Recent County‑Led Efforts Related to Performance Measurement

In 2015, counties collectively contracted with a group of researchers to conduct an assessment of the CalWORKs program, referred to as the CalWORKs Strategic Initiative. The CalWORKs Strategic Initiative’s work has examined issues relating to (1) county policies and procedures related to the recent program changes, (2) county staffing and staff development needs, (3) strategies for client engagement, (4) county partnerships, and (5) how data and performance measurement practices might support more effective program operations. In part, the Strategic Initiative’s work relative to performance measurement contributed to the development of the recent Cal‑OAR legislation, described in detail below.

Overview of Cal‑OAR

As described previously, the Legislature enacted legislation to establish Cal‑OAR as part of the 2017‑18 budget package. In terms of its main components, Cal‑OAR is based on the California Child and Family Services Review (C‑CFSR), the county performance measurement and accountability system used in child welfare services. We describe the main features of Cal‑OAR below.

Requires Development of New Performance Measures

The Cal‑OAR legislation requires the development of performance measures, referred to in the legislation as “indicators,” that are consistent with program goals. These measures are to include both process measures and outcome measures, although the legislation does not specifically define the measures. Process measures are intended to focus on things like the types of services provided, how those services are provided, and the extent to which recipients utilize these services. Outcome measures are intended to focus on things like recipients’ employment, educational attainment, program exits and reentries, and potentially other measures of family and child well‑being. County‑level data on these measures will be reported and published no less frequently than semiannually.

Establishes County Assessment, Planning, and Reporting Process on Three‑Year Cycle

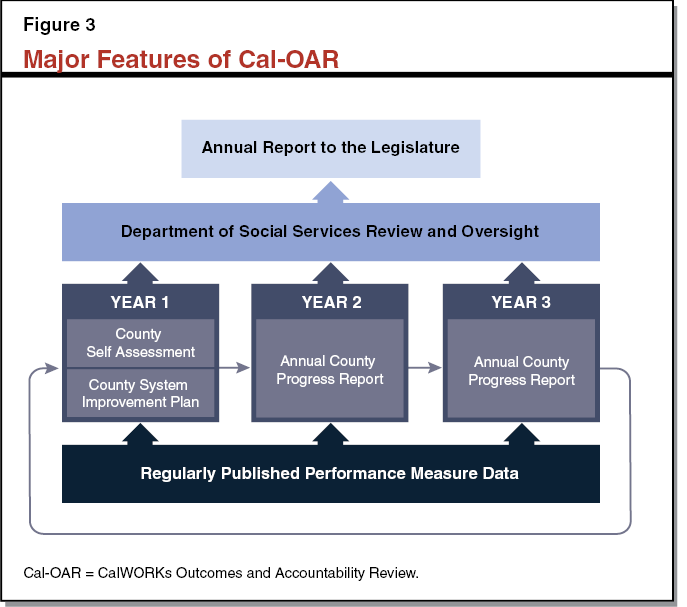

The Cal‑OAR legislation further establishes a process through which counties would use these performance measures to assess their own performance and set goals for improvement. Each county will repeat this process on a three‑year cycle. The main components of this process are described below and displayed in Figure 3.

County Self‑Assessment. First, counties will undergo a self‑assessment, in collaboration with local stakeholders, that will review their performance relative to the Cal‑OAR measures; identify the factors that contribute to that performance, including strengths and weaknesses in county practices; and consider potential areas of focus for future improvements.

County System Improvement Plan. Following the self‑assessment, counties will develop a system improvement plan that describes the steps counties will take to improve in selected areas, and will feature related targets for Cal‑OAR performance measures. For some process measures, counties will be required to meet statewide targets determined by DSS (in consultation with stakeholders). For other measures, counties may establish targets based on individual circumstances. The development of county system improvement plans will involve a peer review component similar to the CPR process in current law, in which peer counties will share best practices and provide other technical assistance to the county developing the system improvement plan. County system improvement plans are required to be approved by local elected officials, such as county boards of supervisors.

Annual Progress Reports. After approval of system improvement plans, counties will be required to prepare annual updates on progress toward meeting goals identified in the system improvement plans.

DSS Oversight Role

The DSS will play an important oversight role under the Cal‑OAR legislation. County self‑assessments, system improvement plans, and annual reports will all be required to be submitted to DSS for review and approval. Additionally, DSS is required to facilitate the sharing of best practices and provide technical assistance to support the implementation of the system improvement plans. The DSS is also required to regularly monitor county performance relative to the Cal‑OAR measures. In the event that DSS determines that a county is consistently failing to meet statewide targets for process measures or other targets established through system improvement plans, the department is required to provide targeted technical assistance and, if performance does not improve, may require counties to take corrective actions to improve performance. Finally, DSS is required to report to the Legislature annually on trends in county performance and makes recommendations on any issues identified through the development of county system improvement plans that merit legislative consideration.

Implementation Guided by Workgroup Process

Key Implementation Details to Be Determined by Workgroup. Many details related to how Cal‑OAR will operate have yet to be determined. Budget legislation requires DSS to convene a workgroup in the fall of 2017 consisting of counties, legislative staff, interested welfare advocacy and research organizations, current and former recipients, and others, to produce a plan for Cal‑OAR implementation. The workgroup will determine which performance measures to use, considering what data are already collected and how the administrative burden of additional reporting can be limited; what elements county self‑assessments and system improvement plans should include; and how county peer reviews will be structured. The workgroup will also examine state and county workload and costs associated with implementing Cal‑OAR and make recommendations on potential financial incentives for counties based on their performance. Prior to implementation, DSS is required to annually update legislative budget committees on the progress and timelines to implement Cal‑OAR.

Implementation by July 2019. Budget legislation requires that DSS implement Cal‑OAR by July 2019, based on plans developed by the workgroup, with the cycle of counties conducting self‑assessments and preparing system improvement plans beginning after baseline data are collected. Following completion of the first Cal‑OAR cycle, DSS will establish, in consultation with the workgroup, statewide standard thresholds for process measures. The workgroup will also convene following implementation to examine potential changes to the performance measures or potentially additional performance measures.

Issues for Consideration

In concept, we think that Cal‑OAR will significantly increase the extent of performance measurement in CalWORKs and has the potential to place greater emphasis on outcomes measurement. Below, we outline several issues for consideration by the workgroup and the Legislature related to how Cal‑OAR can be structured as planning and implementation progress in coming months and years.

Aligning Performance Measures With Other Federal Workforce Programs

Federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Programs Assessed Using “Common Measures.” The federal WIOA, passed in 2014, reauthorized several federal programs related to workforce development, including those that provide funding for local employment services and adult education. These programs have goals that overlap with those of CalWORKs, in that they seek to assist individuals with obtaining employment or higher wages, in many cases by providing services to address barriers to employment. For programs reauthorized by WIOA, state and local performance is assessed using a set of common measures, described in Figure 4.

Figure 4

WIOA Common Measures

|

|

|

|

|

|

aMeasure still under development. WIOA = Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. |

Recent Federal Actions Expand Use of WIOA Common Measures. The federal government has recently taken actions to expand the application of WIOA common measures to other programs. Specifically, beginning in 2017, California is newly required to use WIOA common measures to assess the performance of CalFresh employment and training programs. These programs are administered by the majority of the state’s 58 counties and provide employment and training services to CalFresh recipients that are similar in concept to CalWORKs welfare‑to‑work services. Additionally, in recent years legislation has been introduced in Congress, but not enacted, that would require states to assess the performance of TANF programs using outcome measures that are similar to some of the WIOA common measures.

Priority Consideration Should Be Given to WIOA Measures. In choosing a key set of performance measures for Cal‑OAR, giving priority consideration to the common measures used in federal WIOA programs would make sense for several reasons. First, these measures are consistent with the CalWORKs program’s goals of increasing employment and wages. We note that one of the measures included in the currently inoperative CalWORKs Pay for Performance program measure is very similar to the employment measure used in federal WIOA programs. Second, using WIOA common measures increases the consistency with which performance is measured in workforce‑related programs in the state more broadly. In our August 2016 report, Improving Workforce Education and Training Data in California, we recommended that the state adopt common performance measures that would be used across all of the state’s workforce education and training programs, including CalWORKs. Using WIOA common measures in CalWORKs would promote this goal. Finally, as noted above, there has been movement at the federal level to increase the application of the WIOA common measures to additional programs, including potentially to state TANF programs. Using WIOA common measures in CalWORKs could reduce the risk that the state would have to significantly change performance measures as the result of potential future federal actions.

Consider Steps to Account for Other Factors That Affect Outcomes

As noted previously, outcome measurement can be challenging because other factors beyond the program can affect outcomes, sometimes making it difficult to distinguish the role of the program in causing an outcome versus the role of other factors.

Some Other Programs Use Statistical Techniques to Adjust Performance and Expectations in Light of Local Conditions. Below, we briefly describe approaches used in some other programs to adjust for the effect of other factors beyond the program when measuring outcomes. As one example, in programs authorized under WIOA, federal law requires that a statistical model be used to determine states’ “expected performance” on common measures based on the conditions in the state, such as the strength of the labor market and characteristics of program participants. This expected performance level is then used as a starting point for determining state targets for performance that are tailored to a state’s individual circumstances. A similar process is used to determine local targets within California. In another example, federal law requires that state performance in child welfare services programs be adjusted to account for the conditions in the state and the characteristics of populations served. Each state’s adjusted performance is then compared to national targets to determine whether performance expectations have been met. Statistical adjustment is also used in similar ways in some state TANF programs. We describe the role of statistical adjustment in performance measurement in the TANF program of one state—Minnesota—in the following box.

Performance Measurement in the Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP)

Minnesota’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, referred to as MFIP, is administered locally by 87 counties and four tribal employment service providers. Below we describe at a high level how performance in MFIP is measured.

State‑Defined “Self‑Support Index” Is Primary Performance Measure. The performance of local MFIP administrators is measured and reported on several measures, including the federal work participation rate (WPR). Among these measures, however, the MFIP performance measurement system focuses on a state‑defined measure referred to as the self‑support index. The self‑support index is calculated as a percentage of program recipients in a given quarter that three years later (1) have left assistance for reasons other than exceeding the program’s time limits or being subject to a sanction or (2) are working at least 30 hours a week.

Local Performance Individually Measured Against Statistically Determined Range. Local performance on the self‑support index is determined by whether a local administrator’s percentage falls below, within, or above, an individualized “range of expected performance” for that administrator. The range of expected performance for each local administrator is determined using a statistical model that predicts a range of expected performance based on various factors including economic conditions and demographic characteristics of recipients in the local area. Adjusting the ranges of expected performance to reflect these factors is intended to make performance targets more realistic to reflect local conditions, such that achieving a given percentage on the self‑support index may be viewed as successful for one local administrator but not another. For example, in 2016 the lowest expected range of performance for a local administrator was 50.2 percent to 61.9 percent. The highest expected range of performance for a local administrator for the same year was 77.9 percent to 91.4 percent.

Local Administrators May Earn Incentives, or Potentially Face Penalties, Based on Self‑Support Index Performance. Local administrators that achieve a self‑support index above their expected range of performance receive a bonus of 2.5 percent of their usual funding. Local administrators that fall below their expected range of performance are required to submit improvement plans to the state and eventually, if performance does not improve, have their funding reduced as a penalty.

Statistical Adjustments Can Be Beneficial, Subject to Constraints of Available Data. By accounting for the effect of factors beyond a program that affect outcomes, such adjustments can make it easier to link program operations to outcomes. Accounting for the effect of factors outside the program can also “level the playing field” among different jurisdictions that operate a program in differing local circumstances, helping to explain what might cause differences in performance in different jurisdictions.

At the same time, we note that statistical adjustments are always constrained by the availability of data on the factors that affect outcomes. Complete and comprehensive data on all of the factors beyond a program that may affect outcomes will generally not be available. For some factors, only approximate data will be available and for other factors there may be no available data. Additionally, data may be particularly limited for small jurisdictions. These data limitations can limit the accuracy and reliability of statistical adjustments, or may limit to which outcomes or in which jurisdictions they can be applied.

Consider How Statistical Adjustments for Outcomes Might Be Used in Cal‑OAR. Through the process of developing the details of Cal‑OAR, the working group could consider what role statistical adjustments could play in measuring CalWORKs performance, in light of the potential benefits and data limitations. Statistical adjustment could potentially be used in Cal‑OAR in different ways and in varying degrees. Some ways statistical adjustment might be used include:

- To Enable Statewide Standards for Outcome Measures. As one example, the Cal‑OAR legislation specifies that the department and workgroup can consider in future iterations of Cal‑OAR whether to establish statewide performance standards for outcome measures, provided that all counties could be reasonably expected to meet such standards given varied local conditions. If there is future interest in statewide outcome standards, statistical adjustment could be used to account for the effect that local conditions have on counties’ ability to meet such standards, similar to techniques used in other programs.

- To Provide Additional Perspective on County Performance Relative to Outcome Measures. Another potential use for statistical adjustment might be for DSS to use similar techniques to publish adjusted county performance on selected outcome measures alongside unadjusted county performance. In some cases, local conditions might affect unadjusted county performance in such a way that counties that appear to perform poorly might be shown to perform well after accounting for those local conditions and counties that appear to perform will might be shown to have room for improvement after adjusting for local conditions. This information could help counties to determine which areas to focus on in system improvement plans.

- To Improve DSS Review of County Performance. Finally, DSS could use statistical adjustment as a tool to perform oversight over county self‑assessments and system improvement plans. For example, adjusting county performance to reflect local conditions could help DSS to determine whether or not differences in county performance are more likely the result of local conditions or more likely the result of practices that could be improved. Similarly, statistical adjustment could be used to help DSS evaluate whether targets chosen by counties in their system improvement plans are reasonable given those counties’ local circumstances.

In each of these examples, the use of statistical adjustments, including the data sources and models used to adjust for the effect of other factors on outcomes, would need to be revisited periodically and refined as policies and conditions in which CalWORKs operates in the state and in the counties change over time.

Performance Measures Should Reflect Balance of State and Federal Priorities

Cal‑OAR Presents Opportunity to Put in Place Additional Performance Measures Consistent With State Priorities. As noted previously, the state’s CalWORKs priorities and policies go beyond just meeting the federal WPR requirement and, in some cases, have the potential to work at cross‑purposes with meeting that requirement. The enactment of Cal‑OAR presents an opportunity to institute additional performance measures that are consistent with state priorities that are not necessarily reflected in the WPR, such as providing services to remove barriers to employment or providing flexibility in activity assignments. Putting additional measures in place that are consistent with these state priorities will elevate the prominence of these state priorities and better enable the state to track how these priorities are being achieved.

Need for Balancing State Priorities Against Compliance With Federal Requirement Remains. At the same time the state is working to improve performance relative to Cal‑OAR measures, it must still meet the WPR requirement or face penalties, requiring the state to balance the implementation of its priorities against the need to meet the federal requirement. Because of state actions taken to substantially comply with the WPR requirement, the state is exceeding the main WPR threshold, such that the state’s WPR could decrease somewhat without returning to noncompliance. However, it is unclear how the implementation of Cal‑OAR will affect the emphasis that counties place on the WPR requirement in their CalWORKs operations, or what effect this may have on the state’s WPR. It is possible that the additional performance measurement and county self‑assessment and planning will lead to increased engagement overall and a higher WPR. It is also possible that reduced emphasis on the WPR from implementing Cal‑OAR could lead to a lower WPR, resulting in greater risk of federal penalties. Given this uncertainty, it will be necessary to continue to monitor how the state’s WPR is affected as Cal‑OAR is implemented and emphasis shifts to state priorities to a greater extent through performance measurement.

Consider Including WPR as Cal‑OAR Performance Measure. As a way to strike a balance between federal and state priorities for CalWORKs, the working group could consider including the WPR in Cal‑OAR as one measure of engagement, alongside other measures that align more directly with state priorities.

Consider Revisiting County Fiscal Penalties After Cal‑OAR Implementation. The Cal‑OAR legislation does not specifically create county fiscal penalties for Cal‑OAR performance measures, such that the WPR may remain the only performance measure for which counties could face a fiscal penalty if they do not meet established thresholds. This would continue to place emphasis on the WPR relative to other performance measures in Cal‑OAR that have no associated fiscal penalties. After Cal‑OAR implementation, the Legislature may wish to revisit county penalties related to the WPR and consider ways to account for both Cal‑OAR performance measures and the WPR.

Consider Ways to Create More Uniform County Data Collection and Reporting

Multiple Consortia Systems Approach Has Advantages . . . Maintaining multiple automation systems for CalWORKs eligibility determination and case management has certain advantages. Specifically, this approach provides additional flexibility for counties to adapt the automation systems to meet local needs. Operating multiple consortia systems has also resulted in opportunities for innovation and competition among the consortia, leading to new best practices that have been adopted across the consortia systems.

. . . And Drawbacks. However, there are also some drawbacks to the multiple consortia approach. Much of the data on CalWORKs is housed in the consortia systems and, because these systems are operated and managed by the county consortia, DSS does not have direct access to these data. Instead, DSS is often required to make specific requests for the consortia to provide data to the state to use for program oversight purposes. Having different counties using different systems in some cases also results in a lack of consistency in data collection across the state. The three consortia systems do not collect all the same data elements and, even within a single consortia, not all counties use all the data elements included in the system, or use them in the same way. These issues with consistency in data collection from county automation systems have implications for how county performance will be reported in Cal‑OAR that will need to be addressed as part of the workgroup process.

Required Transition to Single System Presents Opportunity to Increase Uniformity. As described previously, the state has recently been required to develop a single, statewide automation system, to be known as the California Statewide Automated Welfare System, or CalSAWS. The development of CalSAWS presents an opportunity for the state to consider ways to standardize data collection and streamline the sharing of county data with DSS in ways that will facilitate the operation of Cal‑OAR. We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to report on how CalSAWS development will result in increased uniformity in data collection and streamline data sharing between the state and counties, and how these changes will enable the implementation of performance measurement through Cal‑OAR.

Cleanup Needed to Align Past Actions With Cal‑OAR

Once implemented, Cal‑OAR will overlap with some previous actions taken by the Legislature relative to performance measurement and accountability. The Pay for Performance incentive program, enacted but never funded or fully implemented, is redundant with Cal‑OAR. Similarly, the CPR process is very similar to the peer review envisioned by the Cal‑OAR legislation to be part of the development of the county system improvement plan. The workgroup should consider whether any aspects of these previously enacted program components would be useful to consider as part of Cal‑OAR (for example, whether any of the Pay for Performance measures might be useful as performance measures in Cal‑OAR), at which point they can be repealed.

Conclusion

The CalWORKs program plays a key role in the state’s efforts to assist low‑income families with children, and significant resources are dedicated to achieve the program’s goals. In an environment of differing federal and state priorities and decentralized program administration, effective oversight of program performance by the Legislature takes on great importance. In the past, program performance measurement has emphasized process measures, in particular the federal WPR. The recently enacted Cal‑OAR has the potential to focus performance measurement in CalWORKs more on outcomes that are consistent with the program’s goals. As Cal‑OAR is developed and implemented in coming years, consideration should be given to how Cal‑OAR can align with performance measurement systems used in other major federal workforce programs, account for factors beyond the CalWORKs program that affect outcomes, balance state and federal priorities for CalWORKs, and lead to more uniform county data collection and reporting.