Published with this report . . .

LAO Contact

October 9, 2017

The Property Tax Inheritance Exclusion

Summary

Ownership Changes Trigger Higher Tax Bills. Under California’s property tax system, the change in ownership of a property is an important event. When a property changes hands the taxes paid for the property typically increase—often substantially. Local government revenues increase in turn.

Special Rules for Inherited Properties. While most properties’ tax bills go up at the time of transfer, three decades ago the Legislature and voters created special rules for inherited properties. These rules essentially allow children (or grandchildren) to inherit their parent’s (or grandparent’s) lower property tax bill.

Inheritance Exclusion Benefits Many but Has Drawbacks. The decision to create an inherited property exclusion has been consequential. Hundreds of thousands of families have received tax relief under these rules. As a result, local government property tax collections have been reduced by a few billion dollars per year. Moreover, allowing children to inherit their parents’ lower property tax bill has exacerbated inequities among owners of similar properties. It also appears to have encouraged the conversion of some homes from owner‑occupied primary residences to rentals and other uses.

Revisiting the Inheritance Exclusion. In light of these consequences, the Legislature may want to revisit the inheritance exclusion. We suggest the Legislature consider what goal it wishes to achieve with this policy. If the goal is to prevent property taxes from making it prohibitively expensive for a family to continue to own or occupy a property, the existing policy is crafted too broadly and there are options available to better target the benefits. Ultimately, however, any changes to the inheritance exclusion will have to be placed before voters.

Special Rules for Inherited Property

Local Governments Levy Property Taxes. Local governments in California—cities, counties, schools, and special districts—levy property taxes on property owners based on the value of their property. Property taxes are a major revenue source for local governments, raising nearly $60 billion annually.

Property Taxes Based on Purchase Price. Each property owner’s annual property tax bill is equal to the taxable value of their property—or assessed value—multiplied by their property tax rate. Property tax rates are capped at 1 percent plus smaller voter‑approved rates to finance local infrastructure. A property’s assessed value is based on its purchase price. In the year a property is purchased, it is taxed at its purchase price. Each year thereafter, the property’s taxable value increases by 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower. This process continues until the property is sold and again is taxed at its purchase price (typically referred to as the property being “reassessed”).

Ownership Changes Increase Property Taxes. In most years, the market value of most properties grows faster than 2 percent. Because of this, most properties are taxed at a value well below what they could be sold for. The taxable value of a typical property in the state is about two‑thirds of its market value. This difference widens the longer a home is owned. Property sales therefore typically trigger an increase in a property’s assessed value. This, in turn, leads to higher property tax collections. For properties that have been owned for many years, this bump in property taxes typically is substantial.

Special Rules for Inherited Properties. In general, when a property is transferred to a new owner, its assessed value is reset to its purchase price. The Legislature and voters, however, have created special rules for inherited properties that essentially allow children (or grandchildren) to inherit their parent’s (or grandparent’s) lower taxable property value. In 1986, voters approved Proposition 58—a legislative constitutional amendment—which excludes certain property transfers between parents and children from reassessment. A decade later, Proposition 193 extended this exclusion to transfers between grandparents and grandchildren if the grandchildren’s parents are deceased. (Throughout this report, we refer to properties transferred between parents and children or grandparents and grandchildren as “inherited property.” This includes properties transferred before and after the death of the parent.) These exclusions apply to all inherited primary residences, regardless of value. They also apply to up to $1 million in aggregate value of all other types of inherited property, such as second homes or business properties.

Consequences of the Inheritance Exclusion

The decision to create an inherited property exclusion has been consequential. Hundreds of thousands of families have received tax relief under these rules. As a result, local government property tax collections have been reduced by a few billion dollars per year. Moreover, allowing children to inherit their parents’ lower property tax bill has exacerbated inequities among owners of similar properties. It also appears to have influenced how inherited properties are being used, encouraging the conversion of some homes from owner‑occupied primary residences to rentals or other uses. We discuss these consequences in more detail below.

Many Have Taken Advantage of Inheritance Rules

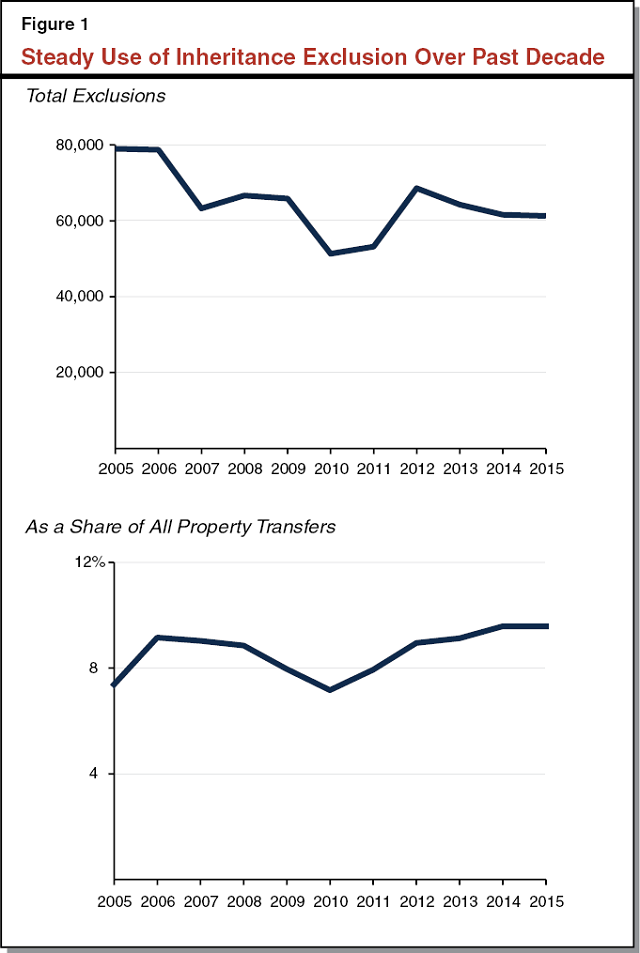

650,000 Inherited Properties in Past Decade. Each year, between 60,000 and 80,000 inherited properties statewide are exempted from reassessment. As Figure 1 shows, this is around one‑tenth of all properties transferred each year. Over the past decade, around 650,000 properties—roughly 5 percent of all properties in the state—have passed between parents and their children without reassessment. The vast majority of properties receiving the inheritance exclusion are single‑family homes.

Many Children Receive Significant Tax Break. Typically, the longer a home is owned, the higher the property tax increase at the time of a transfer. Many inherited properties have been owned for decades. Because of this, the tax break provided to children by allowing them to avoid reassessment often is large. The typical home inherited in Los Angeles County during the past decade had been owned by the parents for nearly 30 years. For a home owned this long, the inheritance exclusion reduces the child’s property tax bill by $3,000 to $4,000 per year.

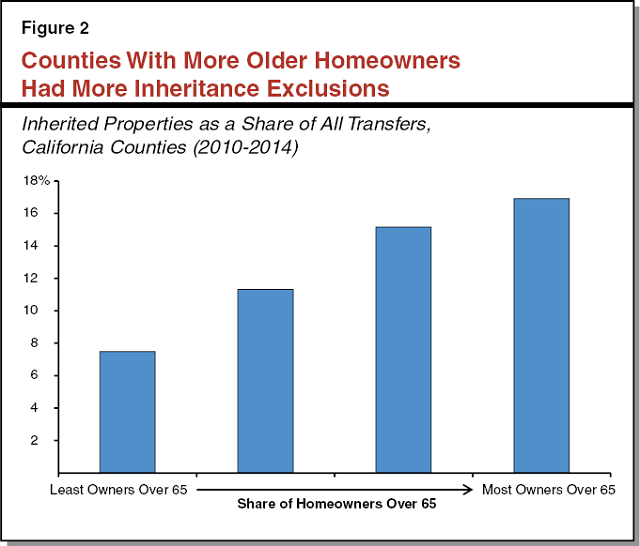

Number of Inherited Properties Likely to Grow. California property owners are getting older. The share of homeowners over 65 increased from 24 percent in 2005 to 31 percent in 2015. This trend is likely to continue in coming years as baby boomers—a major demographic group—continue to age. This could lead to an increasing number of older homeowners looking to transition their homes to their children. This, in turn, could result in an uptick in the use of the inheritance exclusion. Recent experience supports this expectation. As Figure 2 shows, during the past decade counties that had more older homeowners also had more inheritance exclusions. This suggests a relationship between aging homeowners and inheritance exclusions which could lead to a rise in inheritance exclusions as homeowners get older.

Significant and Growing Fiscal Cost

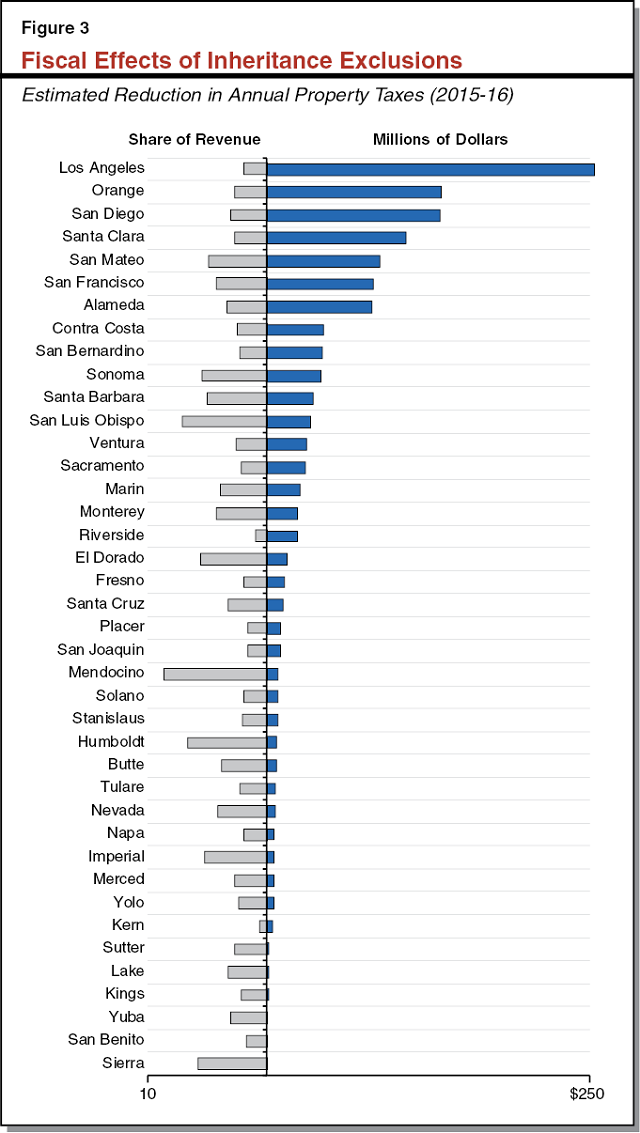

Reduction in Property Tax Revenues. The widespread use of the inheritance exclusion has had a notable effect on property tax revenues. We estimate that in 2015‑16 parent‑to‑child exclusions reduced statewide property tax revenues by around $1.5 billion from what they would be in the absence of the exclusion. This is about 2.5 percent of total statewide property tax revenue. This share is higher in some counties, such as Mendocino (9 percent), San Luis Obispo (7 percent), El Dorado (6 percent), Sonoma (6 percent), and Santa Barbara (5 percent). Figure 3 reports our estimates of these fiscal effects by county.

Greater Losses Likely in Future. It is likely the fiscal effect of this exclusion will grow in future years as California’s homeowners continue to age and the use of the inheritance exclusion increases. While the extent of this increase is difficult to predict, if the relationship suggested by Figure 2 is true it is possible that annual property tax losses attributable to inheritance exclusions could increase by several hundred million dollars over the next decade.

Amplification of Taxpayer Inequities

Inequities Among Similar Taxpayers. Because a property’s assessed value greatly depends on how long ago it was purchased, significant differences arise among property owners solely because they purchased their properties at different times. Substantial differences occur even among property owners of similar ages, incomes, and wealth. For example, there is significant variation among similar homeowners in the Bay Area. Looking at 45 to 55 year old homeowners with homes worth $650,000 to $750,000 and incomes of $80,000 to $100,000 (values characteristic of the region), property tax payments in 2015 ranged from less than $2,000 to over $8,000.

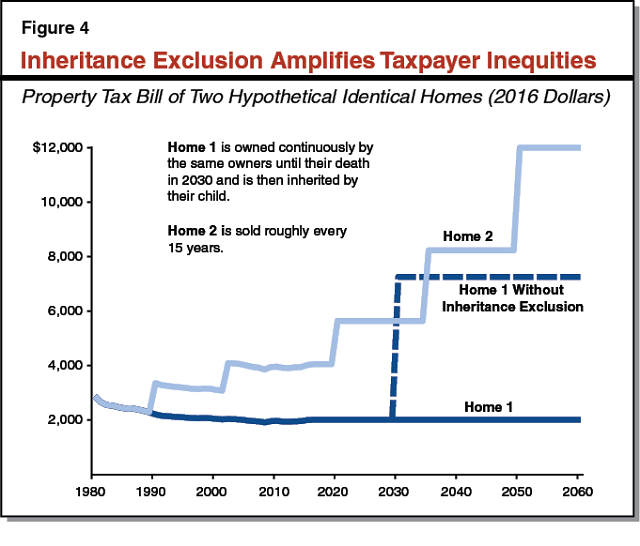

Inheritance Rules Amplify Inequities. Inheritance exclusions exacerbate underlying taxpayer inequities. This is because inheritance exclusions effectively lengthen the amount of time a property can go without being reassessed. To see how this happens, consider an example of two identical homes built in the same neighborhood in 1980:

- Home 1 is purchased in 1980 and owned continuously by the original owners until their death 50 years later, at which time the home is inherited by their child.

- Home 2, in contrast, is sold roughly every 15 years—around the typical length of ownership of a home in California.

We trace the property tax bills of these two homes over several decades in Figure 4 under the assumption that the homes appreciate at historically typical rates for California homes. By 2030, home 1’s bill would be one‑third as much as home 2’s bill. In the absence of the inheritance exclusion, when home 1 passes to the original owner’s child it would be reassessed. This would erase much of the difference in property tax payments between home 1 and home 2. With the inheritance exclusion, however, the new owner of home 1 maintains their parent’s lower tax payment. Over the child’s lifetime, the difference in tax payments between home 1 and home 2 continues to grow. By 2060 home 1’s bill will be one‑sixth as much as home 2’s bill.

Unintended Housing Market Effects

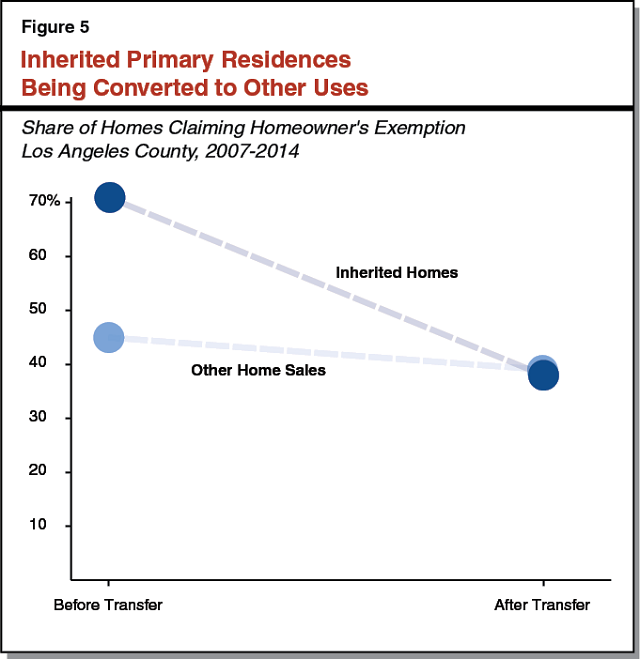

Many Inherited Primary Residences Converted to Other Uses. Inheritance exclusions appear to be encouraging children to hold on to their parents’ homes to use as rentals or other purposes instead of putting them on the for sale market. A look at inherited homes in Los Angeles County during the last decade supports this finding. Figure 5 shows the share of homes that received the homeowner’s exemption—a tax reduction available only for primary residences—before and after inheritance. Before inheritance, about 70 percent of homes claimed the homeowner’s exemption, compared to about 40 percent after inheritance. This suggests that many of these homes are being converted from primary residences to other uses.

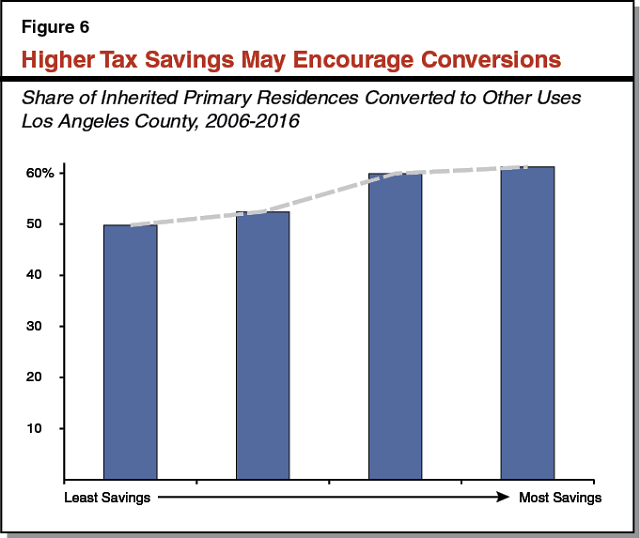

It is possible that this trend arises because people intrinsically make different decisions about inherited property regardless of their tax treatment. A closer look at the data from Los Angeles County, however, suggests otherwise. Figure 6 breaks down the share of primary residences converted to other uses by the amount of tax savings received by the child. As Figure 6 shows, the share of primary residences converted to other uses is highest among those receiving the most tax savings. A little over 60 percent of children receiving the highest tax savings converted their inherited home to another use, compared to just under half of children receiving the least savings. This suggests that the tax savings provided by the inheritance exclusion may be factoring into the decision of some children to convert their parent’s primary residence to rentals or other uses.

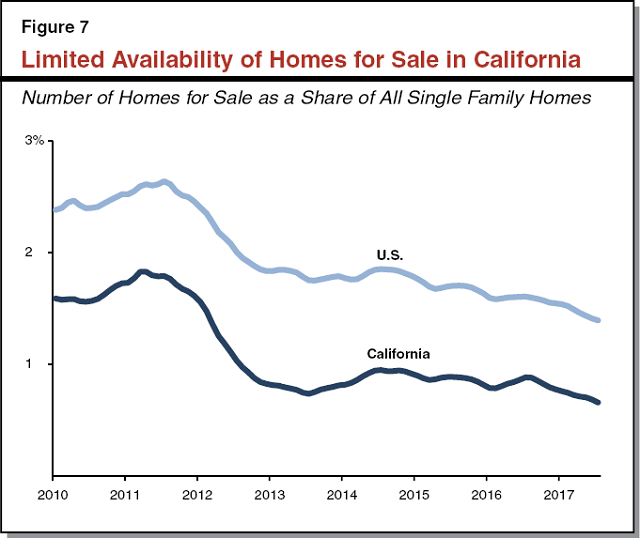

Contributes to Limited Availability of Homes for Sale. The conversion of inherited properties from primary residences to other uses could be exacerbating challenges for home buyers created by the state’s tight housing markets. In many parts of California, there is a very limited supply of homes for sale and buying a home is highly competitive. Figure 7 shows that the inventory of homes for sale is consistently more limited in California than the rest of the country. This limited inventory—a consequence of many factors including too little home building and an aging population—has driven up the price of housing in California and made the home buying experience more difficult for many. When inherited homes are held off the for sale market, these issues are amplified. On the flip side, the shift of inherited homes to the rental market could put downward pressure on rents. The data we reviewed, however, does not allow us to determine how many properties are being converted to rentals as opposed to other uses—such as vacation homes. On net, the shift of homes from the for‑sale market to the rental market likely results in fewer Californians being homeowners and more being renters.

Revisiting the Inheritance Exclusion

It has been decades since Californians voted to create the inherited property exclusion. Since then, this decision has had significant consequences, yet little attention has been paid to reviewing it. Moreover, indications are that use of the exclusion will grow in the future. In light of this, the Legislature may want to revisit the inheritance exclusion. As a starting point, the Legislature would want to consider what goal it wishes to achieve by having an inheritance exclusion. Is the goal to ensure that a family continues to occupy a particular property? Or to maintain ownership of a particular property within a family? Or to promote property inheritance in and of itself?

Different goals suggest different policies. If the goal is to unconditionally promote property inheritance, maintaining the existing inheritance exclusion makes sense. If, however, the goal is more narrow—such as making sure a family continues to occupy a particular home—the scope of the existing inheritance exclusion is far too broad.

Reasons the Existing Policy May Be Too Broad

Property Taxes May Not Be Big Barrier to Continued Ownership. One potential rationale for the inheritance exclusion is to prevent property taxes from making it prohibitively expensive for a family continue to own a particular property. The concern may be that if a property is reassessed at inheritance the beneficiary will be unable to afford the higher property tax payment, forcing them to sell the property. There are reasons, however, to believe that many beneficiaries are in a comparatively good financial situation to absorb the costs resulting from reassessment:

- Children of Homeowners Tend to Be More Affluent. Children of homeowners tend to be financially better off as adults. Data from the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics suggests that Californians who grew up in a home owned by their parents had a median income over $70,000 in 2015, compared to less than $50,000 for those whose parents were renters. Beyond income, several nationwide studies have found that children of homeowners tend to be better off as adults in various categories including educational attainment and homeownership.

- Many Inherited Properties Have Low Ownership Costs. In addition to property taxes homeowners face costs for their mortgage, insurance, maintenance, and repairs. These costs tend to be lower for properties that have been owned for many years—as is true of many inherited properties—largely because their mortgages have been paid off. According to American Community Survey data, in 2015 just under 60 percent of homes owned 30 years or longer were owned free and clear, compared to less than a quarter of all homes. Consequently, monthly ownership costs for these homeowners were around $1,000 less than the typical homeowner ($1,650 vs. $670). Because most inherited homes have been owned for decades, children typically are receiving a property with lower ownership costs.

- Property Inheritance Provides Financial Flexibility. In addition to lower ownership costs, an additional benefit of inheriting a property without a mortgage is a significant increase in borrowing capacity. Many inherited properties have significant equity. This offers beneficiaries the option of accessing cash through financial instruments like home equity loans.

Many Children Not Occupying Inherited Properties. Another potential rationale for the inheritance exclusion is to ensure the continued occupancy of a property by a single family. Many children, however, do not appear to be occupying their inherited properties. As discussed earlier, it appears that many inherited homes are being converted to rentals or other uses. As a result, we found that in Los Angeles County only a minority of homes inherited over the last decade are claiming the homeowner’s exemption. This suggests that in most cases, the family is not continuing to occupy the inherited property.

Potential Alternatives

If the Legislature feels the existing policy is too broad, it has several options to better focus the exclusion on achieving particular goals. In addition to better aligning the policy with a particular objective, narrowing the exclusion would help to minimize some of the drawbacks discussed in the prior section. Below are some options the Legislature could consider. These options could be adopted individually or could be combined. Any changes ultimately would have to be placed before voters for their approval.

Limit to Homes Used as a Primary Residence. One option is to limit the exclusion to homes that are occupied by the family member following inheritance. Inherited homes used as rentals or second homes would be subject to reassessment. Such a change could possibly cut in half the property tax losses resulting from the existing exclusion.

Apply Means Testing. Another option is to require means testing to determine eligibility for the exclusion. The Legislature could set an income threshold under which a child’s income would have to fall to be eligible for the inheritance exclusion.

Phase In Property Tax Increase. A third option is to phase in over several years the property tax increase resulting from the reassessment of an inherited property. This change would reduce the overall financial benefit provided by the exclusion—in recognition of the relative affluence of many beneficiaries—while still providing some short‑term relief. The interim period during which the increase is phased in could provide the family member time to make financial arrangements to accommodate the ongoing ownership costs of their inherited property.

Conclusion

When a property changes hands the taxes paid for the property typically increase—often substantially. This is not true, however, for most inherited property. Three decades ago, the Legislature and voters decided that most inherited property should be excluded from reassessment. This has been a consequential decision. Many have benefited from the tax savings this policy affords. Nonetheless, the inheritance exclusion raises some policy concerns about taxpayer equity and adverse effects on real estate markets.

In light of these consequences, the Legislature may want to revisit the inheritance exclusion. We suggest the Legislature consider what goal it wishes to achieve with this policy. If the goal is to prevent property taxes from making it prohibitively expensive for a family to continue to occupy a home, the existing policy is crafted too broadly and there are options available to better target the benefits. Ultimately, however, any changes to the inheritance exclusion would have to be placed before voters.

Companion Video

Companion Video