LAO Contact

December 19, 2017

California Community Colleges:

Interim Evaluation of Baccalaureate Degree Pilot Program

Executive Summary

Background

Legislature Authorizes Community Colleges to Offer Bachelor’s Degrees on a Pilot Basis. Chapter 747 of 2014 (SB 850, Block) authorizes the California Community Colleges (CCC) to offer bachelor’s degrees on a pilot basis at 15 community college districts. Generally, community colleges are limited to offering associate degrees and certificates, with the awarding of bachelor’s degrees reserved for the state’s universities. Under Chapter 747, each pilot community college district may offer one bachelor’s program at one college site. Programs must be in a subject area with unmet bachelor’s level workforce needs. Additionally, the programs were to be selected in consultation with the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC) to ensure a district does not duplicate a bachelor’s degree already offered by one of the universities. Participating districts were required to begin enrolling students by fall 2017.

Pilot to Be Evaluated in 2018 and 2022. Chapter 747 requires our office to conduct an interim evaluation of the pilot program in 2018 and a final evaluation in 2022. This report fulfills the interim evaluation requirement. Chapter 747 sunsets July 1, 2023 unless a later statute deletes or extends that date.

Evaluation

CCC Made Rapid Progress in Implementing Pilot. Within four months of Chapter 747’s enactment, the Chancellor’s Office selected 15 programs through a competitive process and received preliminary approval for the programs from the CCC Board of Governors. All programs received final approval within another four months. Ten of the pilot degree programs began enrolling students in fall 2016 and all 15 programs enrolled students in fall 2017.

Accelerated Approval Process Resulted in Limited Review and Consultation. The rapid approval process required that CCC leaders make decisions about the proposed bachelor’s degrees with substantially less information than routinely provided for new community college programs. Moreover, consultation with the universities was very limited and CCC approved some degree programs over CSU’s objections.

Only Some Approved Programs Have Strong Evidence of Need for Bachelor’s Degrees . . . A majority of the approved bachelor’s programs are in fields where the typical entry‑level requirement is below a bachelor’s degree. Moreover, for most of the approved programs, state licensing and industry certification do not require a bachelor’s degree. Some of the approved programs in health careers, however, have stronger workforce justification due to increasing accreditation requirements in their fields.

. . . But Local Employers and Students Are Positive About the Programs. Notwithstanding the lack of evidence supporting the need for some of the programs, the local employers and students we interviewed cited various reasons for liking them. They emphasized that the programs (1) were more convenient than other bachelor’s degree programs, (2) provided more nuanced job preparation tailored to local needs, (3) fostered close relationships with employers that were resulting in internship opportunities and early job offers for students, and (4) promoted better job retention due to hiring locally trained students.

Discontinuation of Some Associate Degree Programs a Concern. Most of the pilot colleges indicate that they plan to continue offering related associate degrees alongside their new bachelor’s degrees. Four colleges, however, are discontinuing their existing associate degrees in favor of offering only their new bachelor’s degrees. With one exception (occupational studies), we see no justification for discontinuing these programs.

Concerns About Current Evaluation and Sunset Provisions. Under the current provisions, very little student outcome data will be available at the final evaluation date to help ascertain whether the program is effective. This is because colleges would stop admitting students several years ahead of the sunset date to ensure the students can complete their degrees while the program remains authorized. Extending the sunset date, however, would have a major drawback. A longer enrollment period would work to further engrain the program in the status quo, potentially making terminating the pilot more difficult even if the outcome data show that the pilot was ineffective. To allow for a more robust evaluation without entrenching the program for many years, the Legislature simultaneously could permit colleges to continue enrolling new students through the fall 2021 term and move up the final evaluation one year—to 2021 from 2022.

Initial Student Cohorts Demographically Similar to CCC Students Who Transfer to Universities. This finding could imply either that the pilot is expanding access to bachelor’s degrees or shifting student demand away from the universities. Students we interviewed generally indicated they are place‑bound and unable to move for a university program, thus suggesting that the program is expanding access. With respect to financial aid, the share of CCC pilot program students receiving need‑based aid is similar to the shares for CSU and UC undergraduates.

Financial Data Needs Significant Improvement. Although our office worked closely with the CCC Chancellor’s Office to identify financial data reporting requirements, the initial financial data reports that CCC submitted in September 2017 had a number of problems. The problems we encountered are common to the first round of data collection for a new program. Nonetheless, the data problems are such that we are unable to draw meaningful conclusions about institutional and student costs. The CCC Chancellor’s Office has committed to working closely with our office to improve data collection for the remainder of the implementation period.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Interim Findings Suggest Caution in Extending Pilot. Since enactment of Chapter 747, the Legislature has faced pressure to expand the bachelor’s degree pilot program. Given numerous concerns about program selection and consultation, a lack of any graduation or workforce outcomes to date, and problems in financial reporting, the Legislature may wish to exercise caution in expanding the bachelor’s degree pilot program in advance of the final evaluation.

Fundamental Questions Remain. As the Legislature thinks more about the future of the pilot, it continues to face five fundamental questions: (1) Are bachelor’s degrees detracting from CCC’s core mission? (2) Could improved collaboration between CCC and CSU yield better results than CCC independently offering more bachelor’s degrees? (3) Is a bachelor’s degree the best solution for addressing certain employers’ needs? (4) If more bachelor’s programs are warranted, to what extent should they include content that overlaps with university courses, especially if such overlap means students are trained for a broader range of jobs? (5) What should be the role of employers in training workers?

Introduction

State law authorizes the California Community Colleges (CCC) to award associate degrees and certificates, generally limiting the awarding of more advanced degrees to the state’s universities. As an exception to this rule, Chapter 747 of 2014 (SB 850, Block) authorizes CCC to offer baccalaureate (bachelor’s) degrees on a pilot basis at 15 community college districts. Chapter 747 requires the Legislative Analyst’s Office to conduct an interim evaluation of the pilot program. This report fulfills that statutory requirement. Below, we provide background on CCC’s role in California’s higher education system and describe the main components of the statewide pilot program. We then (1) describe and evaluate the selection of the pilot bachelor’s degree programs, (2) provide initial information about students participating in the pilot programs, and (3) discuss the financing of these programs. We conclude by identifying issues for the Legislature to consider as the 15 colleges continue implementing the pilot program.

Background

In this section, we provide background on undergraduate education and then describe the main components of the pilot program created by Chapter 747.

Undergraduate Education

Key Distinction Between Lower‑Division and Upper‑Division Courses. Introductory undergraduate courses, called lower‑division courses, are designed primarily for freshmen and sophomores (though juniors and seniors also may take them). Completing a series of these courses at a community college can lead to workforce certificates, associate degrees, and/or transfer to a university. Upper‑division courses are designed for juniors and seniors. These courses often build on students’ knowledge from lower‑division courses, providing more specialized and in‑depth study. Bachelor’s degrees include both lower‑ and upper‑division courses, with the latter typically comprising at least one‑third of degree requirements (40 out of 120 semester units).

Aspects of Undergraduate Education Assigned to Community Colleges and Universities. The Donahoe Act—Chapter 49 of 1960 (SB 33, Miller)—directed CCC to offer instruction “through but not beyond” the first two years of college, including courses designed for workforce training, associate degrees, and transfer to universities. By comparison, the act assigned both lower‑ and upper‑division coursework to the two university systems—the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC). In the ensuing years, the Legislature added remedial (basic skills) instruction, adult noncredit instruction, community education, and economic development as additional CCC statutory responsibilities.

Recent Legislation Created Exception to Longstanding Mission Differentiation. In a departure from the segments’ longstanding delineated missions, Chapter 747 authorized the CCC bachelor’s degree pilot. Chapter 747 specified that the 15 districts selected for the pilot maintain their primary CCC mission as articulated in previous legislation while adding another mission—to provide high‑quality bachelor’s degrees at an affordable price for students and the state. (As discussed in the nearby box, community college bachelor’s degrees are becoming increasingly common in other states.)

Community College Bachelor’s Degrees

Community College Bachelor’s Degrees Are a Relatively Recent Phenomenon. A handful of community colleges in the country began offering bachelor’s degrees in a few selective disciplines in the 1970s and 1980s. The number of community colleges offering bachelor’s degrees grew slowly but steadily over the next couple of decades. In 2001, 21 community colleges in 11 states offered 128 bachelor’s degrees. Since 2001, the trend has gained steam. In 2017, 86 community colleges in 16 states offered more than 400 bachelor’s degrees. In addition to these 16 states, another state recently authorized community colleges to offer three bachelor’s degrees, currently under development.

More Than Half of Community College Bachelor’s Degrees Are Applied. The most common types of community college bachelor’s degrees are bachelor of applied science, bachelor of applied technology, and career‑specific degrees, such as bachelor of science in nursing or bachelor of social work. Applied degrees typically contain relatively more workforce courses and fewer general education courses (such as social sciences and humanities) than the standard bachelor of science or bachelor of arts degrees. Applied degrees are intended to prepare graduates to enter the workforce directly after completing the assigned course of study.

Extent to Which Community Colleges Grant Bachelor’s Degrees Ranges Widely Among States. The majority of states still do not allow their community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees. Among the 16 states currently offering community college bachelor’s degrees, most authorize three or fewer colleges to offer the degrees, and these colleges typically offer between 1 and 4 types of bachelor’s programs. A few of these states provide broader authority. Florida, for example, allows all its community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees, resulting in a total of 222 programs at 24 colleges.

Five States Have Stopped Offering Community College Bachelor’s Degrees. In these states, institutions that previously offered the degrees (1) no longer offer them, (2) offer them only jointly with a university, or (3) still offer them but have been institutionally reclassified and are no longer considered community colleges.

Main Components of Pilot Program

Objectives. Chapter 747 indicates a need to produce additional skilled workers with bachelor’s degrees to (1) maintain the state’s economic competitiveness, (2) meet workplace demand for higher levels of education in applied fields, and (3) address unmet student demand for education beyond the associate degree in certain disciplines. The legislation also states that community colleges could give place‑bound local students and military veterans the opportunity to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Programmatic Requirements. Chapter 747 requires the CCC Board of Governors to select no more than 15 districts to each offer a single bachelor’s program at one college within the district. Each pilot degree program must (1) be in a subject area with documented, unmet, bachelor’s‑level workforce needs in the region and (2) not duplicate a bachelor’s degree or curriculum that one of the state’s public universities already offers. Moreover, the Board of Governors is to select the pilot degrees in consultation with CSU and UC. The pilot degree programs are to begin no later than the 2017‑18 academic year, and students who enroll in the programs must complete their degrees by the end of the 2022‑23 academic year, by which time freshmen entering in 2017‑18 would have had six years to graduate.

Funding and Fees. Chapter 747 specifies that state funding for the pilot programs is at the same funding rate per full‑time equivalent student as other CCC credit courses ($5,310 in 2017‑18). Bachelor’s degree students taking lower‑division courses pay the same general course enrollment fee as other students, currently $46 per unit. Bachelor’s degree students taking upper‑division courses pay the $46 per unit general course enrollment fee plus a supplemental $84 per unit fee, bringing the total charge for upper‑division courses to $130 per unit.

Financial Aid. Under Chapter 747, financially needy students in CCC bachelor’s degree programs can receive a California College Promise Grant (previously called a Board of Governors Fee Waiver) covering general course enrollment fees, but not the supplemental upper‑division course fee. Students who qualify for a Cal Grant can receive a tuition award fully covering upper‑division fees. Cal Grant‑eligible students also can receive up to $4,672 annually for nontuition costs through a combination of Cal Grants and state‑funded grants for full‑time CCC students. (Beyond state aid, students can apply for federal Pell Grants—up to $5,920 in 2017‑18—and federal student loans.)

Application Requirements. Chapter 747 also specifies the written information a district had to submit when applying to participate in the pilot program. The district was required to document unmet workforce needs and justify the need for the proposed four‑year degree; document its consultation with CSU and UC regarding collaborative approaches to meeting regional workforce needs; describe the pilot program’s curriculum, faculty, and facilities; provide enrollment projections; and provide a plan for administering and funding the program. In addition, districts were to submit a written policy requiring all potential students who wish to apply for a fee waiver to complete and submit a federal financial aid application (or a corresponding state application for certain noncitizen students).

Evaluation and Sunset. In addition to the interim evaluation of the pilot program, Chapter 747 requires our office to complete a final evaluation by July 1, 2022. Chapter 747 sunsets July 1, 2023 unless a later statute deletes or extends that date.

Evaluation

In this section, we describe and evaluate CCC’s process for selecting the pilot degrees. We also describe characteristics of the students enrolled in the new programs. We conclude with a review of how colleges are financing the new degree programs.

Program Selection

Below, we describe the CCC’s selection criteria and application review for the new bachelor’s degrees, discuss CCC’s consultation process with CSU and UC, and detail CCC’s approval and initiation of the new degrees.

Selection Criteria and Application Review

Application Specified Selection Criteria. The Chancellor’s Office released the application form to districts in November of 2014, with applications due the following month. By the application deadline, nearly half of districts had submitted applications. The first round, however, did not yield 15 approved pilot programs. The Chancellor’s Office, in turn, conducted a second round of applications from March to April 2015, receiving 14 additional applications. The application form for both rounds listed the criteria and point values for selecting pilot programs, summarized in Figure 1 . Applications scoring fewer than 75 points (out of a possible 100) did not qualify for consideration. Among those with qualifying scores, the Chancellor’s Office indicated it would consider geographic distribution and diversity of the proposed programs.

Figure 1

Selection Criteria

|

Criteria |

Main Considerations |

Points |

|

Need for Degree |

|

25 |

|

||

|

||

|

Program Design |

|

25 |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Institutional Management and Commitment |

|

20 |

|

||

|

||

|

Identified Resources |

|

20 |

|

Overall Feasibility |

|

10 |

|

Total |

100 |

Applications Included Labor Market Data and Employer Testimonials. As part of the application process, the Chancellor’s Office assisted districts by obtaining standardized data from the state Employment Development Department (EDD) on earnings and projected employment growth for occupations related to each proposed bachelor’s degree. In addition, applicant districts were required to submit supplemental information justifying the need for their proposed degrees. Most districts submitted summaries of discussions with local employers and/or licensing requirements related to their proposed degrees. For some districts, however, the advent of bachelor’s degrees in the identified disciplines is new. As a result, traditional labor market data does not exist. To document workforce demand for these degrees, applicant districts instead relied on testimonials from employers and position statements from professional associations and accrediting bodies.

Review Team Scored Applications and Made Recommendations to CCC Leadership. To select the pilot districts, the Chancellor’s Office assembled a review team of 29 members. Twenty reviewers were community college administrators and faculty from districts that did not apply for the pilot and thus had no apparent conflict of interest. The remaining nine team members consisted of three statewide Academic Senate representatives, three Chancellor’s Office administrators, two California Department of Education program consultants, and a UC campus articulation officer. Although CCC solicited reviewers from the Intersegmental Committee of the Academic Senates (which includes representatives from all three higher education segments), no CSU representatives participated. Each of the 29 reviewers completed a web‑based training to promote consistency in scoring applications. Each reviewer then scored three or four applications, with each application scored by at least three reviewers. Based upon these scores, the review team gave the Chancellor’s Office recommendations regarding which programs to select for the pilot.

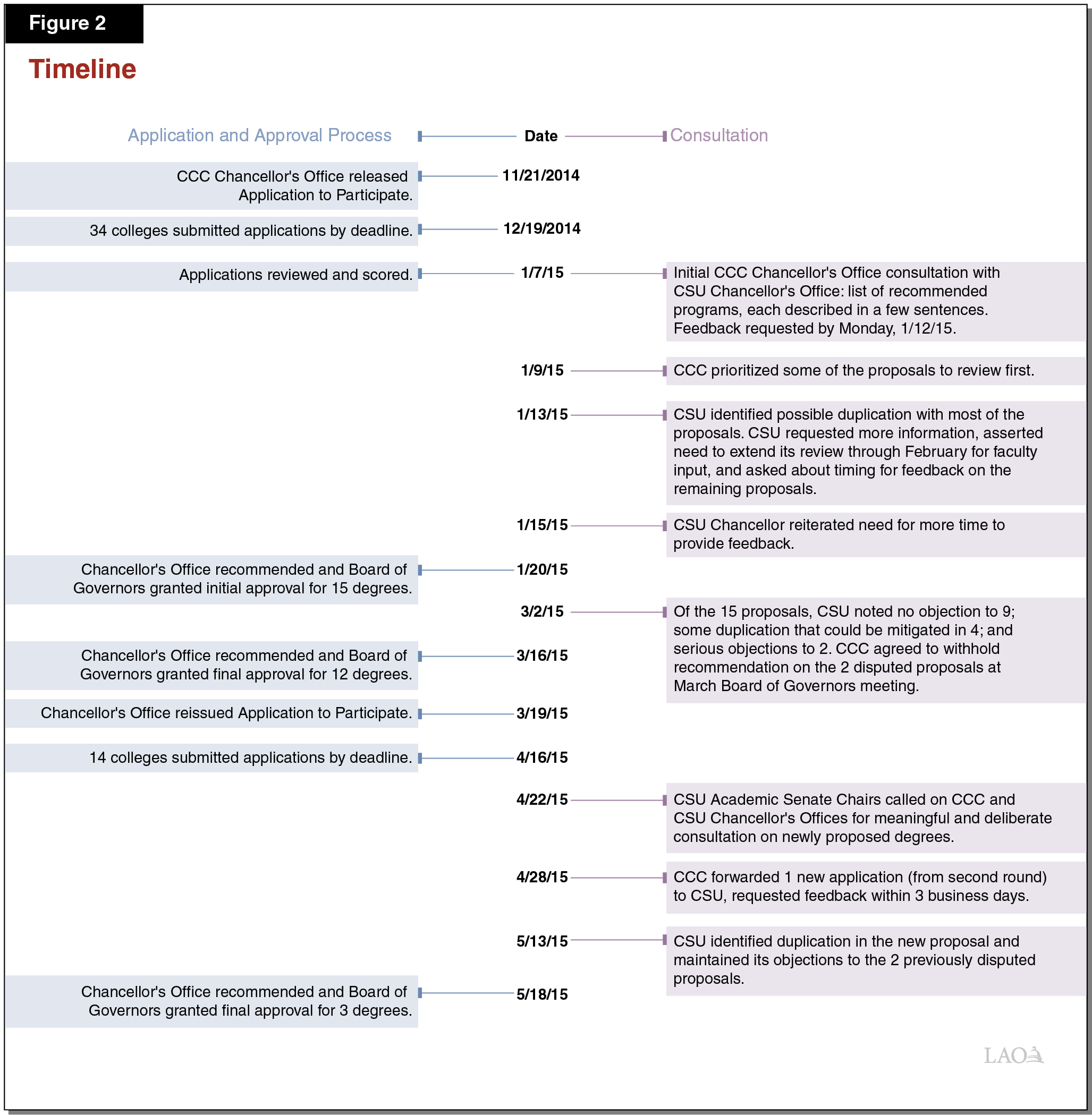

Consultation With CSU and UC

CSU Chancellor’s Office Initiated Consultation With CCC. To document nonduplication of university programs, applicant districts generally looked at university websites and catalogs and talked with faculty from nearby university campuses. No formal consultation among the segments, however, was built into CCC’s initial selection process. CSU voiced concern about the lack of consultation in December 2014 and, in response, CCC provided the universities a preliminary list of recommended degree programs in early January 2015. The material CCC submitted to the universities included brief descriptions of each of the recommended programs. (See Figure 2 for a timeline of associated application, consultation, and approval steps.)

CSU Requested Additional Information and Time. CCC initially requested feedback from CSU regarding degree duplication within three business days of having submitted the list of recommended programs. The CSU Chancellor promptly notified CCC that CSU had concerns about all but three of the recommended programs, pending further information and review. (CSU had no concerns about a mortuary science program or two dental hygiene programs.) The CSU Chancellor also noted that the university would need through February to fully respond, given the timing of the request between terms (when systemwide and campus Academic Senates are not in session).

CSU Formally Objected to Three Degrees. After securing additional information from CCC about the recommended degree programs, CSU formally objected in March 2015 to two degrees—automotive technology at Rio Hondo College and interaction design at Santa Monica College—based on duplication of CSU curriculum. CSU also noted that four degrees—in biomanufacturing, emergency services and allied health, respiratory care, and occupational studies—had some duplication requiring additional collaboration to mitigate. The second round of applications and related consultation in April followed a similar pattern: CCC transmitted information about one new recommended program (biomanufacturing at Solano College) and requested feedback within three business days. CSU formally objected to the Solano College proposal based on duplication of CSU curriculum.

Board of Governors Approval

Fifteen Bachelor’s Degrees Initially Recommended, 12 Approved. Based primarily on review scores (using the average of the top three scores for each application), the CCC Chancellor’s Office recommended 15 applications for initial approval at the January 20, 2015 Board of Governors meeting. The board granted initial approval, pending (1) additional labor market information from the 15 colleges and (2) completion of the consultation process with CSU and UC. At the March 16, 2015 Board of Governors meeting, the Chancellor’s Office recommended and the board granted final approval for 12 of the 15 degrees. Of the three applications not given final approval, two involved CSU objections and the third (from Crafton Hills College) was withdrawn due to a district accreditation issue.

Second Round Yielded Three More Approved Degrees. At the Board of Governors May 18 meeting, the Chancellor’s Office recommended, and the Board of Governors granted, final approval for the two degrees from the first round to which CSU objected and one additional degree from the second round, to which CSU also objected. Figure 3 summarizes the approved bachelor’s degree programs, and Figure 4 lists the programs not selected, along with the reasons given for denying those applications.

Figure 3

Approved Bachelor’s Degree Programs

|

Program |

Community College |

Associated Jobs |

|

Airframe Manufacturing Technology |

Antelope Valley |

Lead technician for aerospace manufacturing or guided missile and space manufacturing, industrial production manager, or aerospace engineering or operating technician. |

|

Automotive Technology |

Rio Hondoa |

A range of management positions in the automotive industry, including jobs in general operations, sales and marketing, training, technical writing, and purchasing. |

|

Biomanufacturing |

MiraCosta and Solanoa |

Technician, inspector, analyst, or coordinator in production and quality management for companies fabricating products through biological processes. |

|

Dental Hygiene |

Foothill and West Los Angeles |

Registered dental hygienist. Also could work in research, education, management, public health, and businesses related to dental health. |

|

Equine and Ranch Management |

Feather River |

Farmers, ranchers, agricultural managers, animal scientists, food science technicians, farm management advisors, veterinary assistants, animal breeders. |

|

Health Information Management |

San Diego Mesa and Shasta |

Registered health information (medical records) administrator or technician. Also could work in medical coding and reimbursement, professional education, information systems, data analysis, practice management, quality management, risk management, and compliance. |

|

Industrial Automation |

Bakersfield |

Technologist, technician, or managerial‑track positions in production and logistics (warehousing and transportation) facilities. |

|

Interaction Design |

Santa Monicaa |

Designer, developer, or architect for products and systems (including software, processes, and physical spaces). Includes graphic designer, software developer or engineer, and web designer. |

|

Mortuary Science |

Cypress |

Licensed funeral director, embalmer, crematory manager, cemetery manager, or cemetery broker. Also could work in cemetery sales, insurance sales, or mortuary management. |

|

Occupational Studies |

Santa Ana |

Certified occupational therapy assistant. Also could work as a clinical educator, lifestyle coach, activities director, or behavioral aide. |

|

Respiratory Care |

Modesto and Skyline |

Certified or registered respiratory care therapist or technician. Also could work in health care management, clinical education, research, patient case management, home health, or health care sales. |

|

aBoard of Governors approved in second round on May 18, 2015. All other programs approved March 16, 2015. |

||

Figure 4

Bachelor’s Degree Programs Denied

|

Program |

Community College |

Reasons Given for Denial |

|

Agricultural Food Safety—Fresh Produce |

Hartnell |

Accreditation concerns |

|

Allied Health Educator |

Southwestern |

Geographic distribution |

|

Applied Research and Data Analytics |

Pasadena Citya |

Below minimum score and duplication |

|

Applied Technology in Viticulture |

Allan Hancock |

Duplication with CSU |

|

Automotive Technology Administration |

Evergreen Valleya |

Accreditation concerns |

|

Automotive Technology and Management |

San Jose Evergreen |

Accreditation concerns |

|

Biology Laboratory Science (Evening/Weekend) |

Berkeley Citya |

Duplication with CSU |

|

Biomanufacturing |

Solano |

Accreditation concerns |

|

Community Corrections |

Golden West |

Below minimum score/accreditation concerns |

|

Cybersecurity Technician |

Coastlinea |

Duplication with CSU |

|

Dental Hygiene |

Fresno City |

Below minimum score |

|

Dental Hygiene |

Oxnarda |

Disciplineb |

|

Dental Hygiene |

Fresno Citya |

Disciplineb |

|

Diagnostic Medical Sonography |

Merced |

Below minimum score |

|

Diagnostic Medical Sonography |

Merceda |

Below minimum score |

|

Educator for Allied Health Professionals |

Southwesterna |

Duplication with CSU |

|

Electron Microscopy |

San Joaquin Delta |

Fiscal management concerns |

|

Electron Microscopy |

San Joaquin Deltaa |

Below minimum score |

|

Emergency Services & Allied Health Systems |

Crafton Hills |

Accreditation concerns |

|

Histotechnology |

Mt. San Antonioa |

Geographic distribution |

|

Manufacturing Processing & Design |

Yuba |

Below minimum score/accreditation concerns |

|

Network Information Technology |

College of the Canyons |

Geographic distribution |

|

Network Technology |

College of the Canyonsa |

Below minimum score and duplication |

|

Public Safety Administration |

Lake Tahoe |

Duplication with CSU |

|

Real Estate Appraisal |

Glendale |

Geographic distribution |

|

Respiratory Therapy |

Ohlone |

Disciplinec |

|

Respiratory Therapy |

Napa |

Disciplinec |

|

Sustainable Environmental Design/Human Habitat |

Saddleback |

Geographic distribution |

|

Sustainable Human Habitat |

Saddlebacka |

Below minimum score and duplication |

|

Sustainable Facilities Management and Operations |

Laney College |

Below minimum score |

|

Technical Supervision and Management |

Ventura |

Geographic distribution |

|

Water Utilities Management |

Cuyamacaa |

Did not document strong student interest |

|

Workplace Safety and Environmental Management |

Cuyamaca |

Geographic distribution |

|

aSecond‑round application. bTwo dental hygiene programs were selected in first round. cAnother respiratory therapy program in same region scored higher. |

||

Board of Governors Adopted Policies and Regulations. Through an extensive series of workshops, meetings, and conferences, the CCC Academic Affairs division, the Academic Senate of the CCC, and the 15 selected pilot colleges developed policy recommendations to guide development of the new bachelor’s degree programs. The recommendations addressed student admission criteria, curricular requirements, faculty qualifications, and student support services. The Board of Governors adopted the recommended policies at its March 2016 meeting in the form of a Baccalaureate Degree Pilot Program Handbook to be maintained by the Chancellor’s Office.

First Students Admitted One Year Ahead of Required Timeline. Ten of the 15 bachelor’s degree programs enrolled their first students in fall 2016. The remaining five enrolled their first students the following year, in fall 2017.

Assessment of Program Selection

Below, we evaluate the evidence of workforce demand for the approved CCC degree programs and discuss concerns about the CCC consultation and approval processes.

Workforce Demand

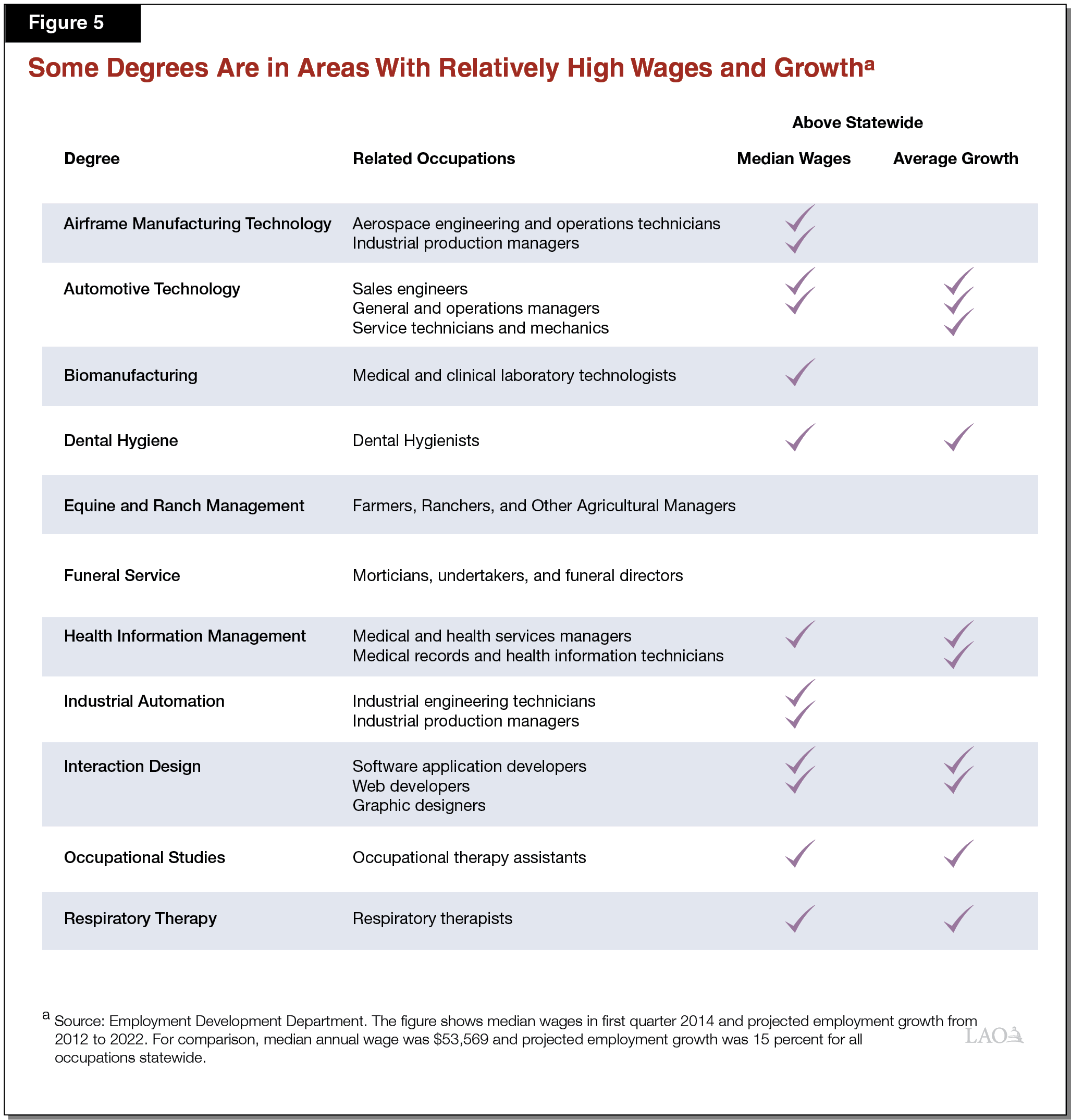

Some Approved Programs Might Be in High Workforce Demand Areas. Chapter 747 does not specify how CCC should measure and prioritize workforce demand. Two measures the state commonly uses to prioritize workforce development spending are (1) average occupational wages and (2) projected employment growth. Wage data from EDD show higher‑than‑average earnings in several occupations related to the approved degrees. For example, the data show that industrial production managers, dental hygienists, and health services managers earn higher‑than‑average wages. Additionally, EDD employment projections show higher‑than‑average employment growth for dental hygienists, software and web developers, and occupational therapy assistants, among others. In several other pilot degree program areas, however, statewide average wages or employment growth are not particularly high (see Figure 5). Wages are not high in equine and ranch management or funeral service, for example, and are only average for several of the other degree program areas. Employment growth is not high in airframe manufacturing and some of the other industrial technology areas. Moreover, the application did not require information about supply of graduates to compare to projected demand. In at least one discipline (dental hygiene), schools in the state already appear to be producing sufficient numbers of graduates to meet or exceed employer demand.

Most Approved Programs Are in Workforce Areas Not Requiring Bachelor’s Degrees. Figure 6 summarizes education requirements for state licenses and industry certifications in the pilot bachelor’s degree fields. As the figure shows, a majority of the fields do not require individuals to hold a bachelor’s degree to qualify for licenses and certifications. The figure also includes the typical entry‑level education requirement, as identified by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), for occupations associated with the approved CCC bachelor’s degrees. To determine the entry‑level education requirement, BLS considers a variety of factors for each occupation, including the minimum educational requirements in existing law and employer survey data. According to BLS, the entry‑level education requirement is below the bachelor’s degree level for all but one of the pilot‑related occupational areas. (In one area—automotive technology—the figure reflects a higher education requirement because the pilot district maintains that its degree prepares students expressly for management occupations.) The lack of a bachelor’s degree requirement for entry‑level jobs in most areas is not surprising, given Chapter 747 required CCC to select disciplines in which universities do not offer a comparable degree. In some occupational areas, however, BLS descriptions indicate advancement opportunities for individuals with a bachelor’s degree.

Figure 6

Most Approved Degrees Are in Fields That Do Not Require Bachelor’s Degree

|

Degreea |

Bachelor’s Degree Required for State License or Industry Certification? |

Typical Education for Occupationsb |

|

Airframe Manufacturing Technology |

No. |

Associate degree or certificate for technicians. Bachelor’s degree (usually in business or engineering) for managers. |

|

Automotive Technology |

No. |

Associate degree or certificate for service technicians and mechanics. Bachelor’s or master’s degree in business for managers. |

|

Biomanufacturing |

Associate degree or certificate for lab technicians. Bachelor’s degree for biological technologist or scientist license. Similar for optional industry certifications. |

Associate degree or certificate for lab technicians. Bachelor’s degree (typically in biomedical engineering or related field) for engineers, biological technicians, technologists, and technical writers. |

|

Dental Hygiene |

No. |

Associate degree for practicing hygienists. Bachelor’s and master’s degrees for hygienists in education, research, public health, and administration. |

|

Equine and Ranch Management |

No. |

No degree for most occupations, but Bureau of Labor Statistics notes increasing need for associate or bachelor’s degree as farm and land management has grown more complex. |

|

Health Information Management |

Associate degree for certified health information technician. Bachelor’s degree for certified health information administrator. |

Associate degree or certificate for medical records technician, Bachelor’s or master’s degree for management. |

|

Industrial Automation |

More experience (ten years instead of five) required for industry certification without bachelor’s degree. |

Certificate for equipment installer/repairer. Associate degree or certificate for technician. Bachelor’s degree for engineering and management occupations. |

|

Interaction Design |

No. |

Associate degree for web developer. Bachelor’s degree for software developer and graphic designer. |

|

Funeral Service |

No. |

Associate degree for funeral service workers. Additional hands‑on training (during or after associate degree program) under the direction of a licensed professional for morticians, undertakers, and funeral directors. |

|

Occupational Studies |

National accrediting agency will require all occupational therapy assistant education programs to offer a B.S. as the entry‑level degree beginning in 2027. |

Associate degree for occupational therapy assistant. |

|

Respiratory Therapy |

National accrediting agency will require new respiratory therapist education programs to offer a B.S. as the entry‑level degree beginning in 2018, but will permit existing programs to continue awarding the associate degree. |

Associate degree for respiratory therapist. |

|

aAll are Bachelor of Science degrees (B.S.). bAs defined by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics based on a variety of qualitative and quantitative sources. |

||

Approved Programs in Health Careers Have Strongest Workforce Justification. Seven of the approved pilot programs are related to health careers. Though none of the health‑related programs currently requires a bachelor’s degree for entry‑level positions, some reasons exist for offering a bachelor’s degree for three of the four careers (health information managers, respiratory therapists, and occupational therapy assistants). The reasons are rooted in the related health careers’ licensing, certification, or accreditation rules. For health information, graduates can become certified technicians with an associate degree, but national certification as a health information administrator (or manager) requires a bachelor’s degree. Similarly, beginning in 2018 for respiratory therapists and 2027 for occupational therapy assistants, the accreditor for clinical education programs no longer will approve schools that do not offer the bachelor’s degree as the entry‑level credential. Existing respiratory therapy schools will be grandfathered under the new rules, enabling them to continue awarding the associate degree. The rate at which employers shift to hiring respiratory therapists with bachelor’s degrees will depend on the extent to which existing, associate‑level education programs voluntarily convert to bachelor’s‑level programs. We found no comparable justification for offering bachelor’s degrees in dental hygiene. Employment openings overwhelmingly require only an associate degree, and employers we interviewed offered no wage differential or hiring preference for candidates with a bachelor’s degree.

Local Employers and Students Cite Liking the Approved Programs for Various Reasons. Through site visits conducted as part of our analysis, we met with local employers and students at six of the pilot campuses. These stakeholders presented various reasons for liking the approved community college bachelor’s degree programs:

- Better Job Retention. Employers—especially outside of major coastal and metropolitan areas—cited their preference for hiring locally trained residents instead of importing engineers and other skilled workers who might be more likely to leave the area within a few years.

- Convenience of Education Program. Similarly, many of the students we interviewed told us they are unable or unwilling to relocate due to family or other obligations. Many of these students indicated they never expected to pursue a bachelor’s degree until their local community college began offering one. The availability of the degree at a familiar and local institution encouraged them to raise their educational aspirations.

- More Nuanced Job Preparation. Employers reported that the new degrees are giving students the necessary skills for work requiring more than a certificate or associate degree but less than some traditional bachelor’s degrees. “An engineering degree without calculus” is how an employer characterized one of the degrees, noting that the average student in the pilot program likely would not have sought a traditional engineering degree from a university or returned to the local community if he/she had.

- More Advanced Education. Nearly all the students we interviewed identified they were learning valuable communication, critical thinking, and collaboration skills they had not learned in their associate degree programs.

- Early Job Offers. Finally, numerous employers and students noted that students in the new CCC programs had secured job commitments up to a year ahead of graduating, often after completing a summer internship related to their degree. They offered this as evidence that the CCC bachelor’s degrees have workforce value.

Discontinuation of Some Associate Degree Programs a Concern. Most of the pilot colleges indicate that they plan to continue offering related associate degrees alongside their new bachelor’s degrees. Four colleges, however, are discontinuing their existing associate degrees in favor of offering only their new bachelor’s degrees. These are Foothill and West Los Angeles Colleges for dental hygiene, Modesto College for respiratory therapy, and Santa Ana College for occupational studies. We found no evidence of employer need, licensing, certification, or accreditation requirements to justify discontinuing the dental hygiene or respiratory therapy associate degree programs. These programs can help students gain initial employment, and often state licensing or certification, and can serve as feeders to bachelor’s degree programs. (Moreover, Skyline College, which offers a respiratory therapy bachelor’s degree similar to Modesto College, is maintaining its associate degree in this area.) We have somewhat less concern about Santa Ana converting its occupational studies program to the bachelor’s degree because its accreditor has announced that within ten years it will no longer accredit associate degrees for occupational therapy assistants.

Value of Providing Management and Technical Training Together Unclear. Several of the approved bachelor’s degree programs (including airframe manufacturing, automotive technology, biomanufacturing, and industrial automation) documented demand for mid‑level managers who also have technical skills. Historically, employers in these industries either have hired management graduates and provided them the necessary technical training or encouraged talented technical employees to return to school for a management degree. The pilot colleges in these disciplines believe that by providing the technical and management training together, they can better meet the needs of these industries. It remains to be seen how employers will view graduates with these degrees, compared with graduates from general management programs. Perhaps more importantly, it is unclear to what extent the preparation students accrue from the industry‑specific bachelor’s degrees are generalizable into other industries such that workers can be resilient in a dynamic economy, potentially transferring their management skills among industry sectors.

Approval Process

Abridged Program Approval Process. The CCC Board of Governors granted initial approval for the pilot bachelor’s degrees within one month of CCC receiving proposals. This is in stark contrast to CCC’s regular program approval process. The standard approval process for a new CCC workforce certificate or degree typically takes between 18 and 24 months to complete and involves many steps. The main reason cited for the expedited approval process was that not all colleges could participate in the pilot and colleges did not want to invest substantial time in program design if they were not likely to be selected for the pilot. Given these issues, the Board of Governors conducted its selection process before colleges invested time and effort to fully develop the new programs and seek required local approvals. Only after being selected did colleges complete curriculum development and secure local approvals and Chancellor’s Office classification.

Accelerated Timeline Resulted in Limited Review. By shortening the review and approval process, CCC leaders had to make decisions about the proposed bachelor’s degrees with substantially less information than routinely provided for new certificates and associate degrees. Most notably, the pilot application did not require colleges to have completed the local curriculum development and review process. Instead, the application required examples or illustrations of upper‑division coursework for the proposed degree. The application also did not require colleges to submit other information typically required for new programs, including program goals and objectives, information about similar programs (such as programs in other states), or endorsements from an advisory committee and regional workforce consortium. Moreover, with a one‑month turnaround, the Chancellor’s Office and application review team did not have sufficient time to validate the information submitted and assess the workforce value of the proposed degrees. Although colleges eventually received local curriculum approval as they further developed their programs, local review bodies likely would have found it awkward, at best, to delay or deny a program on curricular grounds following Board of Governors approval for the program.

Consultation Process

CCC Fell Short in Meeting Consultation Requirements. The absence of time allotted for consultation in CCC’s approval timeline, the three‑day response time requested from the universities, and approval in January and May 2015 of degrees to which CSU had formally objected based on evidence of curricular duplication, indicate that CCC did not give the required consideration to the consultation process. Public statements from CCC suggest that, while the system initially expected to have meaningful consultation with the universities, it came to believe it needed only to notify the universities of its decisions. In a November 2014 board meeting, for example, the CCC Chancellor said Chapter 747 gives the universities a “de facto veto,” requiring that CCC work with the universities to ensure nonduplication. By the time of the May 2015 meeting, however, CCC administration and faculty leadership contended that only consultation rather than consensus with the universities was required.

Final Program Development Mitigated Some Duplication . . . Though CCC came to believe it did not require CSU buy‑in, it still pledged to work with CSU to mitigate concerns about duplication. For example, in Rio Hondo College’s application to offer an automotive management degree, the college had listed a number of upper‑division business courses similar to those CSU campuses offer, such as “Sales and Marketing Strategies and Techniques” and “Business and Managerial Finances.” The final curriculum for the program, however, includes only courses tailored to the automotive industry, such as “Digital Marketing for the Automotive Industry” and “Standard Accounting Systems of the Automotive Service Industry.” Similarly, the Santa Monica College interaction design degree differs from related graphic design degrees at CSU by focusing more on “user experience” (design of a product of software application from a user’s perspective). This is a topic available in some CSU art, industrial design, and computer science departments, but not as an organized concentration or major at the undergraduate level.

. . . But Process Damaged Relationship Between Segments. Though CCC campuses ultimately worked to mitigate curricular duplication, the hurried approval process resulted in significant tension between CCC and CSU. This tension has complicated intersegmental efforts the past two years. In his public remarks before bringing final program approval to a vote in May 2015, the Board of Governors Chairman lamented the truncated consultation process and noted that any future expansion of the pilot, if approved by the Legislature, should build in more robust and meaningful collaboration with the universities.

Student Participation

Below, we describe student applications, admissions, and enrollment in the pilot programs and provide information on the characteristics of participating students. Student outcome data are not yet available. The first student outcome data will become available following the spring 2018 term. Depending upon how colleges and the Legislature respond to the sunset provision in Chapter 747, CCC will have between two and five years of student graduation, employment, and earnings outcomes by the time of the 2022 final evaluation, as discussed in the nearby box.

The Effect of the Sunset Provision on Program Evaluation

Under the Existing Sunset Provision, Colleges Might Enroll No More Freshmen. Most California Community College transfer students and California State University students take five or six years to complete a bachelor’s degree. If community colleges participating in the pilot program believe they should allow up to six years for entering freshmen to complete the bachelor’s programs, the colleges would need to stop admitting freshmen now. In this case, the pilot program would have only two freshman cohorts (2016‑17 and 2017‑18), with the first of those cohorts reflecting only a partial class (as only 10 of the 15 pilot programs were operative that year). Moreover, these first two cohorts each had low enrollment levels.

Drawbacks to Halting Enrollment at This Time. Halting admissions this early would result in very little student outcome data being available for the final evaluation to help ascertain whether the program is effective. Halting admissions early also could be problematic if the Legislature later decides to extend the pilot. When a program is paused, specialized faculty hired for the program might accept another assignment, creating a temporary staffing problem for the pilot program and necessitating new rounds of faculty recruitment once the program is extended. Often more troubling, a pause in enrollment can shake public confidence in the program’s stability, thereby suppressing future student enrollment and employer support.

Extending Sunset Date Also Has a Major Drawback. To avoid problems associated with halting enrollment, the Legislature could extend the sunset date. A longer enrollment period, however, would further engrain a program in the status quo, potentially making terminating the pilot more difficult even if the outcome data show that the pilot did not meet the Legislature’s objectives.

Consider Amending Sunset and Evaluation Provisions to Balance Competing Priorities. The Legislature could consider extending the sunset date, thereby allowing for more student cohorts to enter the pilot. This, in turn, would result in more years of student outcome data and a more rigorous final program evaluation. To reduce the likelihood of entrenching a potentially ineffective program, the Legislature simultaneously could move up the evaluation date. For example, the Legislature could permit colleges to continue enrolling new students through the fall 2021 term and move up the evaluation one year—to 2021 from 2022. Under this schedule, the final evaluation would include some graduation data for a few freshman cohorts (and more complete graduation data for several junior cohorts). We think this timing would yield sufficient information for the Legislature’s review of the pilot. Under this approach, the enrolling of new cohorts and the release of the final program evaluation are coordinated. Such coordination would allow bachelor’s programs to continue uninterrupted were the Legislature to extend the pilot. It also would limit the number of cohorts that would be affected were the Legislature to sunset the program.

Majority of Applicants Accepted for Admission. To date, 863 students have applied for admission to the 15 CCC bachelor’s degree programs. Figure 7 shows 564 of these students have been admitted and 482 have enrolled. Admission rates for the first two years of the pilot vary notably among programs, ranging from 28 percent to 100 percent. Enrollment rates also vary among programs, ranging from 47 percent to 100 percent of admitted students enrolling.

Figure 7

Program Admission and Enrollment Rates

|

Academic Year |

Applicants |

Admitted |

Admission Rate |

Enrolled |

Enrollment Rate |

|

2016‑17a |

381 |

235 |

62% |

206 |

88% |

|

2017‑18b |

481 |

329 |

68 |

273 |

83 |

|

Totals |

862 |

564 |

65% |

479 |

85% |

|

aTen programs admitted students. bFifteen programs admitted students, but totals exclude Solano College which did not provide data in time for publication. |

|||||

Applications Relatively Low in Most Programs. Colleges reported two main reasons for suppressed demand in the first two years. Some colleges received final program approvals (including accreditation) shortly before the application cycle and thus had limited time to publicize their new programs. Additionally, some colleges noted that systemwide policies and regulations regarding lower‑division general education courses for the new CCC bachelor’s degrees made some students ineligible for admission to the programs. Specifically, the policies require that CCC bachelor’s degrees adopt the intersegmental lower‑division general education requirements recognized by CSU and UC—typically 39 semester units of general education in specified subject areas. One college reported that more than 200 of its associate degree students expressed strong interest in applying to the college’s bachelor’s degree program, but only 23 applied, with the vast majority of the students not qualifying to apply because they did not satisfy all the associated general education requirements. The college has since changed its associate degree program so that its graduates will meet the bachelor’s degree entry requirements, and it expects more applications in the future.

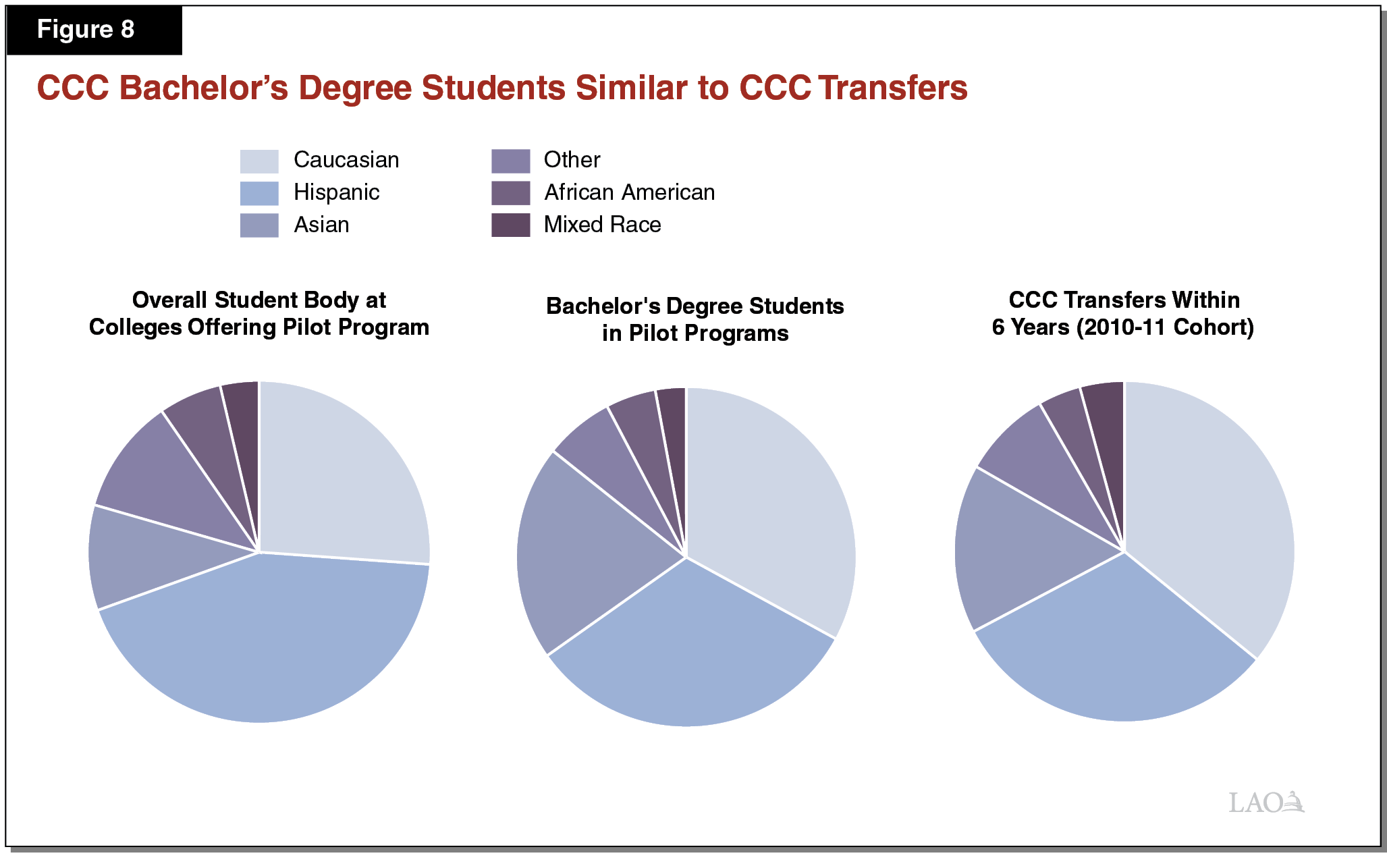

Bachelor’s Degree Students More Like Transfer Students Overall Than Other Pilot College Students. Figure 8 compares the race/ethnicity of students who enrolled in the bachelor’s degree programs in 2017‑18 (the center pie chart) with students at the pilot colleges overall (the left pie chart). CCC’s bachelor’s degree students differ markedly from other pilot college students. Compared to those students, the bachelor’s degree students are more likely to be Caucasian or Asian and less likely to be Hispanic. As reflected in the right pie chart, the bachelor’s degree students more closely resemble successful CCC transfer students.

Unclear Whether Pilot Is Expanding or Shifting Access. Chapter 747 requires that we report on the impact of the pilot degree programs on underserved students. In their initial cohorts, the pilot degree programs do not appear to be primarily serving demographic groups that are underrepresented among transfer students. That is, the CCC pilot programs might be serving students who otherwise would have attended a university program. The students we interviewed, however, generally indicated they are place‑bound and unable to move for a university program. Although they are similar demographically to transfer students, they might differ in other ways that limit their access to university programs.

Bachelor’s Degree Students More Likely to Be Female. Whereas 53 percent of pilot college students overall and successful CCC transfer students are female, 66 percent of CCC bachelor’s degree students are female.

Financing

First Data Collection Highlights Need for Standardization. Although our office worked closely with the CCC Chancellor’s Office to identify fiscal data reporting requirements, the initial fiscal data reports CCC submitted in September 2017 had inconsistencies, missing information, and other data problems. These problems are common in the first round of data collection for a new program and generally can be remedied with refinements to data collection instruments and training for the personnel involved in data collection. Below, we report some information on programs’ startup costs but are unable to draw any conclusions about ongoing program financing due to the data limitations noted.

Startup Costs

State Provided $6 Million for Startup Costs. The 2015‑16 Budget Act provided this funding for equipment, library materials, curriculum development, and faculty and staff professional development, among other one‑time costs. From this amount, the Chancellor’s Office allocated (1) $350,000 to each of the 15 pilot colleges and (2) $750,000 for an implementation support grant awarded competitively to North Orange Community College District. The implementation grant was to support meetings and conferences for the pilot colleges, a website for the colleges to share information, and evaluation activities.

Colleges Used Two‑Thirds of Startup Funds in First Two Years. The pilot colleges used their startup funds for outfitting new labs, purchasing equipment and materials, and—in one instance—purchasing property. They also used funds for curriculum development (typically by paying for faculty release time or hiring consultants) and professional development, including conferences and travel. Some of the funds were used for administration, student counseling and advising, outreach, and accreditation costs. As of June 30, 2017, two colleges reported that they had not yet used any of the funds. Four colleges reported receiving other start‑up funding from their districts or an unspecified source, and one (Bakersfield College) reported a $150,000 industry contribution toward startup costs.

Ongoing Costs

Not Able to Analyze. The greatest data reporting problems were for ongoing program revenues and expenditures. Several colleges did not include state apportionment funds and/or fee revenue from their upper‑division courses. Some colleges attributed few or no instructional costs to their bachelor’s degree programs. For half of the colleges reporting, program expenditures exceeded program revenues—often by substantial amounts—and the colleges gave no indication as to how costs were covered. With all these data problems, we are unable to draw meaningful conclusions about ongoing program financing.

Financial Aid

Financial Aid Data Limited. Initial data reports do not yield a full picture of individual students’ financial need and their use of aid. We can draw a few conclusions from the data, however, as described below.

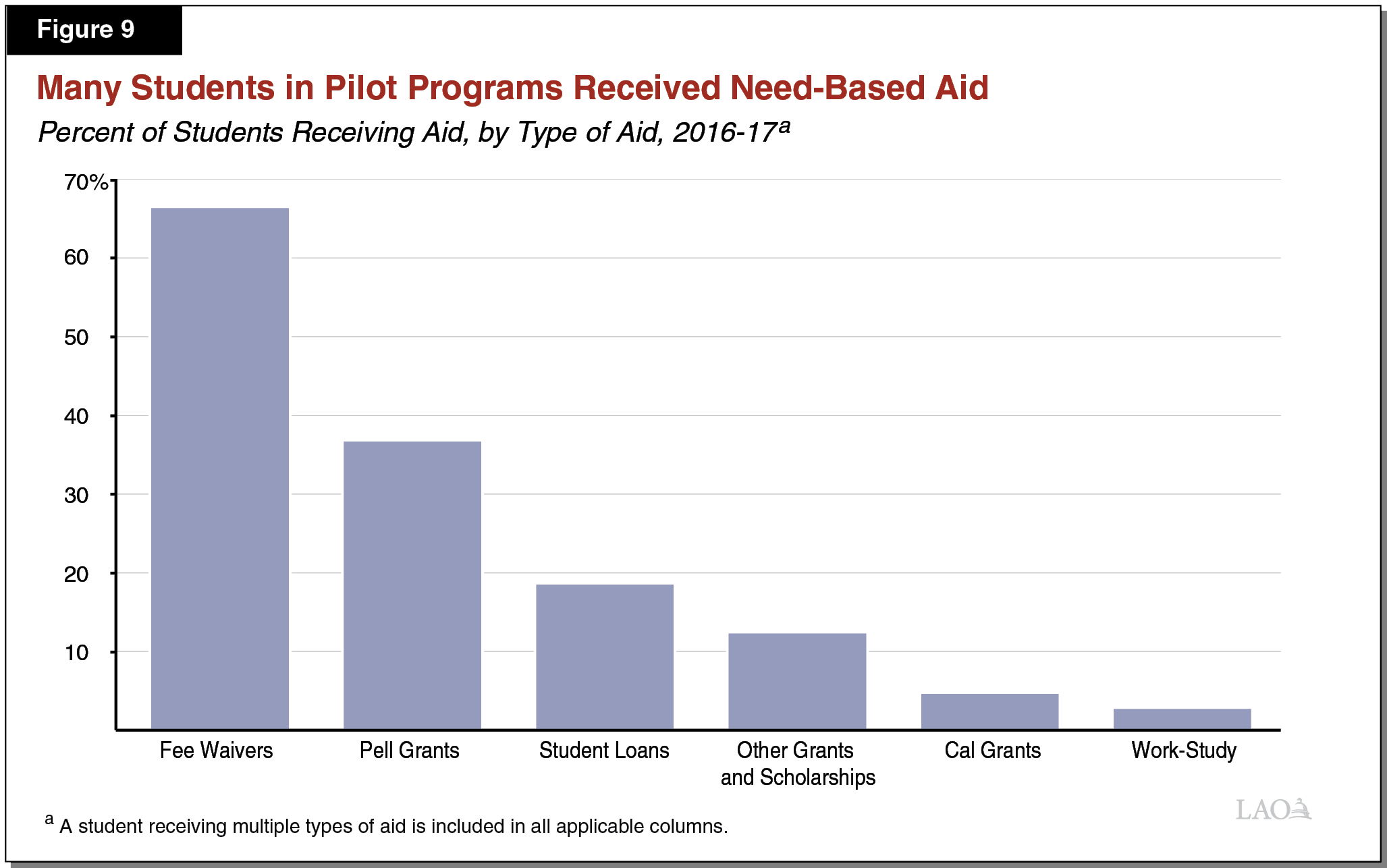

Majority of Pilot‑Program Students Receive Fee Waivers. Fee waivers are the most common form of need‑based financial aid at CCC. As Figure 9 shows, two‑thirds of CCC’s 2016‑17 bachelor’s degree students had their general course enrollment fees waived. This share is slightly lower than the share of all full‑time CCC students receiving fee waivers (71 percent) but notably higher than the share of all CCC students receiving such waivers (50 percent). For further comparison, aid programs cover full tuition for about 60 percent of UC and CSU undergraduate students, with another 10 percent of university students receiving partial tuition coverage. In addition to receiving waivers for their general course enrollment fees, 5 percent of CCC’s 2016‑17 bachelor’s degree students received Cal Grants that covered supplemental upper‑division fees and a portion of other student costs.

Pilot‑Program Students Receive Federal Grants and Loans Too. As Figure 9 also shows, 37 percent of students received Pell Grants in 2016‑17. For comparison, 22 percent of CCC students overall and 49 percent of full‑time CCC students received Pell Grants that year. Of students participating in the pilot programs, 20 percent received federal student loans. (This figure assumes all students receiving a subsidized loan also received an unsubsidized loan. To the extent the overlap is smaller, the share of students with loans increases.) The 20 percent share is substantially higher than for CCC students overall (2 percent) but substantially lower than for university undergraduates (about half).

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Since enactment of Chapter 747, the Legislature has faced pressure to expand the bachelor’s degree pilot program in advance of the 2022 evaluation and 2023 sunset. Findings from our interim evaluation, however, suggest the Legislature may wish to exercise caution in expanding the pilot before the final evaluation. As the Legislature thinks more about the future of the pilot, fundamental questions about the mission of CCC also remain. In this section, we discuss each of these issues.

Interim Findings Suggest Caution in Extending Pilot

Financial Reporting Needs Improvement. Some of the Legislature’s key questions for evaluation regard program financing and student financial aid. Specifically, Chapter 747 requires information on program costs and funding sources as well as student costs, financial aid, and debt. To date, CCC has not provided reliable information on these subjects. With improved reporting, however, we believe colleges could provide the necessary information well in advance of the final evaluation. To that end, the CCC Chancellor’s Office and our office are working together to improve and monitor data reporting.

Too Soon to Gauge Student Outcomes. Chapter 747 also requires information on student graduation, employment, and earnings outcomes, all of which are important for evaluating the success of the pilot. The extent to which outcomes for pilot students are better, worse, or the same as students who transfer to CSU should influence the Legislature’s decision about whether to continue authorizing CCC bachelor’s degrees. The first cohort of graduates, however, will not receive their degrees until spring 2018 at the earliest. We expect generalizable outcomes will not emerge until four cohorts have at least some graduation data (spring 2021).

Numerous Concerns About Selection, Consultation, and Approval Processes. Our findings regarding abridged program development, selection, and approval processes and lack of robust consultation with the universities provide additional reasons for caution. Were the Legislature to consider expanding the pilot, significant improvements would be needed in these processes.

Fundamental Questions Remain

How Are Bachelor’s Degrees Affecting CCC’s Core Mission? At many of the pilot colleges, the new bachelor’s degree programs are building on existing certificate and associate degree programs and giving students an additional option to continue their education. At other pilot colleges, however, the new degrees are replacing existing associate degree programs, thereby limiting students’ educational choices and substantially increasing their costs to enter an occupation. The Legislature may wish to consider whether colleges should avoid curtailing students’ associate degree options.

Is a Bachelor’s Degree the Solution in All Occupations? The employers we interviewed expressed a need for workers with higher skills than they typically find in associate degree graduates. Based on these conversations, however, it appears possible that graduates with associate degrees and some additional education—not necessarily a bachelor’s degree—might meet this need. For example, perhaps three‑year certificates or degrees could provide the desired skills. To serve students and employers well, any new credentials would have to be approved by accreditors and widely recognized by employers. To date, few such credentials exist. The state could explore ways to facilitate colleges and employers working together to develop programs that are more efficient in meeting industry needs.

To the Extent Bachelor’s Degrees Are Warranted, How Focused Should They Be? In our review, we found universal agreement among policymakers, community college officials, and employers that—in keeping with CCC’s workforce mission—any CCC bachelor’s degrees should focus on career education. We found less consensus, however, on how narrowly these degrees should be tailored. Chapter 747 prohibits duplication not only of CSU and UC degrees, but also their curricula. This prohibition has resulted in very specialized upper‑division courses (such as the automotive industry accounting and marketing courses cited earlier) where more general ones likely would better prepare students for a broader range of positions. The Legislature may wish to consider the trade‑offs between avoiding all duplication with the universities (thereby preserving clearer mission differentiation among the segments) and permitting some duplication (thereby potentially better serving students but weakening mission differentiation). Defining how much overlap to allow, however, could prove difficult. For example, should the state permit degree duplication in situations where similar university programs exist but are not offered in a region where a community college has documented a significant workforce need?

Could Improved Collaboration Between CCC and CSU Better Meet Workforce Needs? Another question for the Legislature to consider is whether the universities are providing adequate opportunities for CCC graduates to continue their education. Numerous collaboration models exist in which universities work closely with community colleges to expand opportunities for earning bachelor’s degrees. A partnership between Hartnell College and CSU Monterey Bay provides an illustration. In this partnership, students take courses from both institutions year‑round and earn a bachelor’s degree in computer science in three years. Other models also exist, such as transfer programs in which the university component is taught on a community college campus, online, or through any combination of delivery modes that accommodates working students. Similarly, some states have “3+1” transfer programs in which students complete three years at a community college and the final year at a university. The Legislature may wish to explore ways it could encourage collaborations across segments to help meet workforce needs more efficiently and effectively.

What Should Be the Role of Employers in Training Workers? We heard from employers that some of the pilot bachelor’s degree programs were providing hands‑on training previously offered by the employers, thereby shifting the costs and risks of this training to the colleges (and the state). The Legislature may wish to consider how these costs and risks should be shared among the parties, and what role employers should have in workforce training.

Conclusion

Given the bachelor’s degree pilot has been underway only a few years, our interim evaluation serves mainly to assess CCC’s initial implementation efforts and identify issues for the system and the Legislature to consider as implementation continues. We think numerous reasons exist for the Legislature to exercise caution in expanding the number of pilot programs before the final evaluation. These reasons include needed improvements in data collection, the absence of any student outcomes to date, and concerns raised in the pilot program selection process. The CCC Chancellor’s Office continues to work closely with our office to improve data collection for the remainder of the implementation period. To maximize the value of the resulting information, the Legislature could consider amending the sunset provision in Chapter 747 to permit participating districts to continue enrolling new students until the evaluation is completed, potentially as soon as 2021. With improved data collection and continued student enrollment, we believe the final evaluation will provide the Legislature better information with which to decide the future of CCC bachelor’s degree programs. Even with better information, however, the Legislature will continue facing fundamental issues about CCC’s mission and the best way to provide access to bachelor’s degrees.