LAO Contact

December 21, 2017

CCC and UC:

An Evaluation of Best Value Procurement

Pilot Programs

Summary

State Created Best Value Procurement Pilots in 2012. Chapter 708 of 2012 (Pavley) created pilots authorizing the California Community Colleges (CCC) and the University of California (UC) to use a best value (BV) approach when procuring goods and services. The BV pilots allowed CCC and UC to consider noncost factors—such as quality and experience—when selecting vendors, rather than having to select the lowest‑cost bidder. Chapter 708 required community college districts and UC to develop BV policies and report information about contracts procured during the pilot period. It further required our office to evaluate the pilots and recommend to the Legislature whether to continue CCC’s and UC’s BV authority after the January 1, 2019 sunset. This reports fulfills that requirement.

CCC Did Not Report—Recommend Extending Pilot and Clarifying Statute. Many CCC districts had considered noncost factors in the procurement of services prior to the pilot and continued these practices after the pilot began. Because CCC did not change its practices, it did not believe these practices constituted BV under the pilot. It therefore did not report any contract information as required by Chapter 708. It also cited other reasons for not reporting, such as overly burdensome reporting requirements. Without contract data, we could not assess CCC’s procurement practices. Nonetheless, we recognize BV can have benefits in certain instances. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature extend the CCC pilot program and clarify statute to indicate that consideration of noncost factors in any procurement constitutes participation in the pilot. We also recommend the Legislature simplify reporting requirements and require CCC to develop systemwide BV policies to promote the use of best practices among districts.

UC’s Use of BV Generally Reasonable—Recommend Making BV Authority Permanent. Somewhat similar to CCC, UC considered noncost factors in the procurement of goods and services before the pilot. Prior to the pilot, UC used an alternative procurement method called “Cost Per Quality Point” (CPQP). During the pilot period, UC continued to use CPQP, using it more frequently than BV. Specifically, CPQP accounted for 42 percent of reported contracts during the period, while BV accounted for 14 percent of such contracts. Though UC did not heavily rely on BV during the pilot period, we believe UC’s use of it was reasonable. Having BV authority generally provided UC the flexibility to select vendors that met its needs without greatly increasing up‑front costs relative to the lowest‑cost bidder. We also believe UC developed a reasonable set of BV policies, but some of its guidance to campuses could be improved. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature make UC’s BV authority permanent but require UC to include additional BV best practices in its procurement policies. We also recommend the Legislature have UC phase out CPQP, which is a less common approach than BV, and one for which the effect of price on the final award decision is hard to understand.

Introduction

State Created Two Pilot Programs in 2012. Chapter 708 of 2012 (SB 1280, Pavley) created pilot programs authorizing the use of best value (BV) evaluation in the procurement of goods and services at the California Community Colleges (CCC) and the University of California (UC). The CCC pilot program applied to all 72 community college districts and the UC pilot program applied to all 10 of its campuses, 5 medical centers, and the UC Office of the President (UCOP). Under these BV pilot programs, CCC and UC can select vendors of goods and services based on an evaluation of cost as well as noncost factors—such as quality and experience. Prior to Chapter 708, statute in most cases required CCC and UC to select vendors of goods and services based solely on whether they offered the lowest cost, as long as they met certain other minimum qualifications. This is typically known as the lowest responsible bidder (LRB) approach to vendor selection.

Chapter 708 Required Program Evaluations Prior to January 1, 2019 Sunset. Chapter 708 required CCC and UC to provide our office with information about contracts awarded between 2013 and 2015. It directed our office to assess (1) the advantages and disadvantages of the BV approach compared to the LRB approach, (2) the number and resolution of bid protests, (3) the BV policies developed by CCC districts and UC, and (4) the overall cost of contracts awarded during the period. It further directed us to recommend to the Legislature whether to continue CCC’s and UC’s BV authority. This report fulfills these program evaluation requirements.

We Analyzed Contract Data, Conducted Interviews, and Reviewed Available Studies. To evaluate the pilot programs, we examined contract data provided to our office. (As described later in our report, UC provided contract data, but CCC did not). We also conducted interviews with procurement staff associated with UC (UCOP and five UC campuses) as well as CCC (four districts and CollegeBuys—an organization that handles systemwide procurements for CCC). Additionally, we spoke to procurement staff at numerous other state agencies and departments to learn about their procurement practices and use of BV. Finally, we reviewed various studies about procurement and BV.

Background

In this section, we provide general background on the state’s use of two main approaches to procuring goods and services—LRB and BV. We then provide background specific to CCC’s and UC’s procurement of goods and services prior to the enactment of Chapter 708. (Construction services are treated separately in statute and are not covered in this report.)

State Procurement

Statute Requires Competitive Bidding When Contracts Exceed Certain Monetary Thresholds. When procuring goods and services, the state seeks to promote fair and open competition that is free from bias and favoritism. To this end, statute includes various requirements for the procurement of goods and services, particularly those of significant monetary value. Specifically, statute sets certain monetary thresholds above which agencies generally must use a competitive bidding process to advertise and solicit bids before selecting a vendor. Statute sets the competitive bidding threshold at $50,000 for CCC. Pursuant to statute, CCC’s level is adjusted annually for inflation and is currently at $88,300. Statute sets the threshold for UC at $100,000. Below these competitive bidding thresholds, entities are typically authorized to negotiate with potential vendors and/or solicit bids on a less formal basis. For the remainder of this report, we focus on contracts that must be competitively bid.

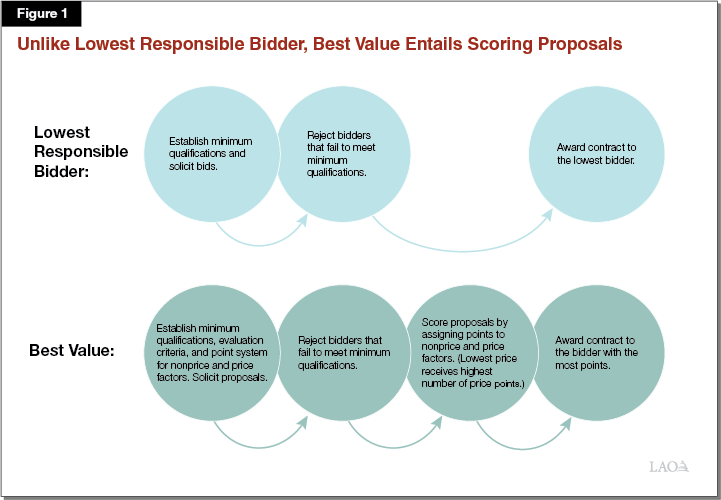

State Uses Two Main Approaches to Procure Goods and Services. Figure 1 outlines these two approaches. Under one approach, LRB, the state issues a solicitation seeking bidders willing to provide the requested goods or services. The state then verifies that the bidders meet the solicitation’s minimum qualifications—specifically, that they are both responsible and responsive. In this context, responsible means the vendor has the capability to do the work in terms of such factors as financial resources and experience. Responsive means the vendor’s bid meets all the requirements identified in the solicitation. Vendors are not rated on these requirements—they either do or do not meet them. Finally, the state awards the contract to the qualified bidder offering the lowest price. The other main approach to competitive bidding is BV. Under the BV approach, the state issues a solicitation for proposals, typically referred to as a Request for Proposal (RFP). Similar to LRB, the state then verifies that the bidders are responsible and responsive. Unlike LRB, the proposals are then evaluated and scored based on cost as well as other criteria. The BV criteria must be specified in the RFP and can include factors such as lifetime costs, use of sustainable materials or practices, experience, timeliness, terms and conditions, or economic benefits to the community. The bidder with the highest score (not necessarily the lowest bid) receives the contract.

Most State Procurement of Goods and Services Historically Has Been Based on LRB . . . State agencies have typically selected vendors using the LRB approach. LRB has been the default approach in state procurement because it is thought to protect the public from the misuse of public funds (since the state pays the lowest price offered by vendors) and guard against favoritism, fraud, and corruption (since the award determination is objectively based on who offered the lowest bid).

. . . But LRB Has Some Limitations. The LRB approach works well in many instances. For example, it is well‑suited to situations where the features of the desired good or service are easy to specify and there is little variation in observed quality across vendors. For example, procurement of routine goods purchased by the state—such as basic office supplies—is typically conducted most appropriately using LRB. However, LRB can sometimes be an inflexible approach when features or quality of a desired good or service are hard to define or the up‑front price does not reflect the longer‑term costs. These limitations have led some state agencies to request authority to consider other factors in addition to price.

State Has Granted Some Public Agencies BV Authority. Recognizing the limitations of the LRB approach, the state in 1983 began allowing some entities to use the BV approach for some purchases (see Figure 2). Notably, the state has authorized the Department of General Services to use this approach to procure services for various state departments. Additionally, it also authorized the California Department of Technology to use the BV approach for procurement of information technology (IT) goods and services (including telecommunications services) for various state departments. It further gave the California State University (CSU) BV authority, which CSU uses to procure goods and services. Finally, it has provided BV authority to certain other entities such as municipal utilities and various regional and local transit, transportation, and highway districts. In some cases, the authority includes both goods and services, while in others it covers only services or only goods.

Figure 2

Several Public Agencies in California Have Had Best Value (BV) Authority

|

State Entity |

Competitive Bid Thresholda |

Used For . . . |

Statutory Authority |

|

California State University |

$50,000 |

Goods and services |

Chapter 219 of 2001 (AB 1719, Committee on Higher Education) |

|

Department of General Services |

$5,000 |

Services |

Chapter 1231 of 1983 (SB 129, Boatright) |

|

Department of Technology |

None |

Goods and services |

Chapter 1106 of 1993 (AB 1727, Polanco)b |

|

Sacramento Municipal Utility District |

$50,000 |

Goods and services |

Chapter 665 of 2001 (AB 793, Cox) |

|

Various transit, transportation, and highway districtsc |

Varies (either $100,000 or $150,000) |

Goods |

Chapter 814 of 2006 (SB 1687, Murray) |

|

Chapter 408 of 2009 (AB 116, Beall) |

|||

|

Chapter 460 of 2009 (AB 644, Caballero) |

|||

|

Chapter 220 of 2012 (SB 1068, Rubio) |

|||

|

aIf the cost of a good or service exceeds this threshold, it must be competitively bid. For the Department of Technology, virtually all contracts must be competitively bid. bAlthough the original authority to use a BV‑like approach for information technology purchases existed prior to this law, Chapter 1106 clarified how the process could be used. cIncludes Alameda‑Contra Costa Transit District, Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District, Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority, Monterey‑Salinas Transit District, Sacramento Regional Transit District, San Mateo County Transit District, Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, and Golden Empire Transit District. |

|||

State’s Experience to Date With BV Generally Positive . . . According to procurement staff at various state departments, BV has provided much needed flexibility, particularly when it comes to complex purchases. While price remains a required consideration under BV, other factors are sometimes as important, or more important, than price. The state’s experience has confirmed that BV can be a valuable tool in cases where it is difficult to define up front the quality or features of a good or service to be procured. This may occur, for example, with complex services that require innovative solutions or that can be delivered in a variety of ways. For example, if a customer needs a supplier to develop a public relations or educational campaign, it may wish to consider various creative approaches that may be difficult to specify in advance. In these cases, BV allows customers (that is, the staff at the state department making the purchase) to ask more nuanced questions of suppliers and to score their proposals based on criteria detailed in the RFPs. Additionally, procurement staff we interviewed noted that BV has allowed them to avoid having to award contracts to poor‑quality suppliers who meet minimum criteria and routinely understate their cost in order to be the low bidder. In these latter cases, BV potentially can yield long‑term state savings while avoiding the hassle of hiring vendors unlikely to perform adequately.

. . . Although It Also Has Some Drawbacks. State procurement staff note some drawbacks to BV relative to LRB. First, the up‑front cost of the contract could be higher as the contract may not necessarily go to the lowest bidder. Second, procurement staff and customers need training on how to carry out a BV procurement successfully because the steps involved in developing the RFP (including evaluation criteria) and in reviewing and evaluating vendor proposals are generally more complex than for LRB. Also due to their complexity, BV procurements are typically more time consuming to conduct than LRB procurements. Finally, BV uses a more subjective evaluation process than LRB to award contracts. Accordingly, a potentially greater chance of bias exists, and thus additional steps need to be followed to ensure that solicitations are fair and free from bias.

Many Other States Use BV. BV is a widely used practice in private industry and is commonly used by public agencies in other states. According to a 2016 survey by the National Association of State Procurement Officials, 41 of the 47 states that responded (including the District of Columbia) reported that their central procurement offices have BV authority. BV is also a common practice among public institutions of higher education. In a 2009 survey conducted by the American Association of State Colleges and Universities and the National Association of Educational Procurement, 77 percent of the responding procurement officers at public four‑year universities and public university systems (representing 37 states and the District of Columbia) reported that state law allows them to consider noncost factors in procurement.

CCC and UC Procurement

CCC and UC Did Not Have Specific BV Authority Prior to Chapter 708. Prior to Chapter 708, statute generally required CCC and UC to use the LRB method to procure goods and services. The exceptions to the requirement to use LRB included procurement of IT goods and services and professional or other services where special training is required—such as insurance, financial, economic, accounting, engineering, or legal services. Statute excludes these types of services from the LRB requirement without specifying the alternative procurement approach (such as BV) to use. In practice, CCC and UC have used an approach like BV, where factors beyond price are considered and scored.

Some Community College Districts Considered Noncost Factors in Procuring Certain Services. Prior to the BV pilot, some of the state’s 72 community college districts considered noncost factors to procure a variety of services. Some of these services appear to be professional services, which, as described above, are excluded from the requirement to use LRB. It appears that CCC also used an approach like BV to procure services that were not clearly professional services, such as food and transportation services.

UC Also Considered Noncost Factors in Its Procurement Practices. Prior to the BV pilot, all UC campuses and UCOP considered noncost factors in the procurement of a wide range of goods and services (not only professional services) through its development of an alternative procurement approach called Cost Per Quality Point (CPQP). As discussed in the box below, UC indicated it believes CPQP complied with the requirement that it use LRB. This approach, however, allowed UC to evaluate and score quality criteria, a process that goes beyond the typical definition of LRB and is more like BV. In the wider procurement industry, CPQP is a lesser‑known approach, and UC campuses indicated they often have to educate vendors on how it works. In particular, the effect that price will have on the final decision is especially difficult to understand. Additionally, no industry standards exist for CPQP because the process is largely unique to UC.

Some UC Procurement of Goods and Services Based on CPQP

UC Developed Alternative Procurement Approach. UC developed its own approach called Cost Per Quality Point (CPQP) before it had the authority to consider noncost factors under the best value (BV) pilot and when it was still required to select the lowest responsible bidder (LRB) for goods and many services. The CPQP approach to procurement establishes a set of “quality” evaluation criteria, which are described in the solicitation. Under CPQP, evaluators score every responsible bidder’s proposal on each criterion within a predetermined range of points. Unlike BV, a bidder’s proposed price is divided by the total number of quality points to reach a CPQP. (For example, if a bidder offers a price of $100,000 and receives 80 out of 100 quality points for factors such as experience, financial stability, and key personnel, then its CPQP would be $1,250.) The bidder with the lowest CPQP is awarded the contract.

CPQP Arguably More Similar to BV Than LRB Process. UC maintains that CPQP conforms to the statutory LRB requirement because the award goes to the bidder with the “lowest cost per quality point.” Yet CPQP scoring systems can produce contract winners that differ from the result of a traditional LRB process. In our assessment, CPQP is more like BV than LRB because it scores noncost criteria and the award may not go to the LRB.

Chapter 708 Authorized CCC and UC to Use BV Through 2018. Chapter 708 established BV pilot programs for CCC and UC for the procurement of goods and services. The main rationale for Chapter 708 was to provide the segments with additional flexibility to purchase goods and services in a cost‑effective manner. Accordingly, Chapter 708 authorized CCC and UC to use BV when they believe they could attain long‑term savings or other economic benefits. Additionally, statute specifies contract evaluation criteria that can be considered, including total cost, operational cost, added value, quality, availability, supplier financial stability and experience, and other economic or environmental benefits.

Chapter 708 Required CCC and UC to Establish BV Policies. Chapter 708 directed CCC and UC to create BV policies prior to using their BV authority under the pilot programs. Specifically, statute required the governing board of any CCC district deciding to use BV to adopt BV policies and required the UC Board of Regents to adopt and publish systemwide BV policies. The legislation required that, in adopting BV policies, CCC districts and UC were to focus on reducing their overall operating costs and supporting their strategic efforts to increase purchasing efficiencies and leverage their purchasing power. It also required them to establish processes for bid protests and resolution of protests. In addition, statute required that for both CCC and UC (1) bidders only be evaluated based on the criteria described in the solicitation, (2) evaluation criteria conform to statute, and (3) bidders that do not receive the contract award be notified in writing.

CCC and UC Also Were Required to Report Certain Contract Information. As a condition of participating in the BV pilot, Chapter 708 also required CCC and UC to provide the following information to our office:

- A copy of adopted BV policies.

- A list of contracts awarded during the period (above the competitive bid threshold) and whether the contract was awarded using BV or LRB.

- For each contract, (1) a brief description of the good or service, (2) the name of the vendor awarded the contract, (3) the total contract cost for CCC and the total contract expenditures for UC (referred to as the contract “volume”), and (4) a summary of any written bid protests and how they were resolved. CCC was also required to provide the bid award announcement and the scored ratings for each bidder.

- For each BV contract, (1) information about the evaluation criteria, (2) the reasons the award winner was selected, (3) whether there were any additional economic benefits beyond the good or service itself, and (4) identification of any comparable previous contracts awarded using the LRB method. (In identifying comparable contracts, CCC was required to provide more detailed information than UC about the previous contracts, such as the solicitation materials, the bid award announcements, names of vendors selected, and the amount of the awards.)

CCC Pilot Program

In this section, we provide our findings and recommendations relating to the CCC pilot program.

Findings

CCC Districts Continued Former Procurement Practices During Pilot Period. CCC reported that no districts participated in the BV pilot program. Based on conversations with CCC districts and CollegeBuys, districts instead continued their previous procurement practices. For many districts, this meant considering noncost factors—just like BV—for the purchase of various types of services. Notably, it appears these purchases were not limited to professional services. In a review of select RFPs on the websites of CollegeBuys and several college districts, we found districts were using a BV‑like approach to procure services such as digital imaging services, food services, and printing services. Staff at one district said it was their understanding that all services (not only professional services) were exempt from the LRB requirement. It is unclear whether any district used the BV‑like approach to procure goods. The four districts to whom we spoke said they limited consideration of noncost factors to the procurement of services and always used the LRB method to procure goods.

No Contract Information Provided for Program Evaluation. As no district participated in the pilot program, CCC did not report any contract information to our office. Lacking this information, we cannot determine: how widespread the practice of using noncost factors in procuring goods and services was among districts, how long districts have been employing this practice, or whether districts’ governing boards adopted policies for considering noncost factors. Furthermore, given the lack of reported information, we were unable to assess the number of bid protests or evaluate overall costs of BV, as required by statute.

CCC Identified Three Primary Reasons for Not Reporting. CCC provided three primary reasons for not reporting the statutorily required information to our office:

- Since none of the districts reported changing procurement practices to use their new BV authority, they believed it was not necessary to report contract information.

- Districts found the reporting requirements too cumbersome, particularly collecting information about past comparable LRB contracts.

- Some districts lacked the staff, expertise, and data systems necessary to compile the required information.

Developing Systemwide BV Policies and Best Practices Could Be Particularly Helpful for CCC Districts. Currently no systemwide policies govern community college districts’ use of BV. Given the relative complexity and potentially greater subjectivity of BV compared to LRB, we think having systemwide BV policies is particularly important. Should CCC use BV (or BV‑like) procurement approaches in the future, a set of well‑understood systemwide policies and best practices would help reduce the risk of bias and ensure that each district follows a minimum set of requirements. This is particularly important given there are 72 districts, many of which likely lack experience or expertise about how to use the standard BV procurement method.

Recommendations

Below, we make three recommendations relating to the CCC BV pilot.

Extend CCC BV Pilot and Clarify Statute. Because we did not receive any information about CCC procurement contracts, we could not assess whether CCC districts used BV appropriately or effectively. However, we recognize that BV procurement can have notable benefits in some cases. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature extend BV authority to CCC on a pilot basis (for example, extending it for five additional years, from 2019 through 2023, with CCC required to report certain information to the state in 2022 and program evaluation required in 2023). In addition, we recommend the Legislature clarify that consideration of noncost factors in any competitive procurement constitutes participation in the pilot. Retaining the pilot and clarifying statute would provide districts additional time to develop BV policies while providing the Legislature an opportunity to receive data on how CCC is using BV. Based upon data submitted over the next few years, the Legislature could assess whether CCC is using BV in an appropriate and cost‑effective manner before deciding whether to make that authority permanent.

Revise CCC Reporting Requirements. The amount of information CCC was required to report (which was somewhat greater than that required of UC) appears to have created a disincentive for districts to participate in the pilot. Accordingly, we recommend revising reporting requirements in collaboration with CCC to ensure adequate information is available to conduct a basic analysis of districts’ use of BV while reducing the burden of the reporting requirements. For example, districts could forgo reporting on previous comparable contracts and focus on providing basic information about each new contract. For each new contract, districts could identify the procurement method used and the price offered by each bidder. For BV contracts, districts also could list the evaluation criteria and each bidder’s score.

Require CCC to Adopt Systemwide BV Policies. We recommend the Legislature require CCC adopt a set of systemwide BV policies prior to participating in an extended BV pilot program. These policies should be based on best practices for BV procurement. A set of systemwide policies reflecting best practices is particularly important given the number and diversity of districts, some of which have small procurement staff and limited BV expertise.

UC Pilot Program

In this section, we share our findings, assessment, and recommendations relating to the UC pilot program. We also compare and contrast UC’s use of BV, CPQP, and LRB procurement approaches.

Findings

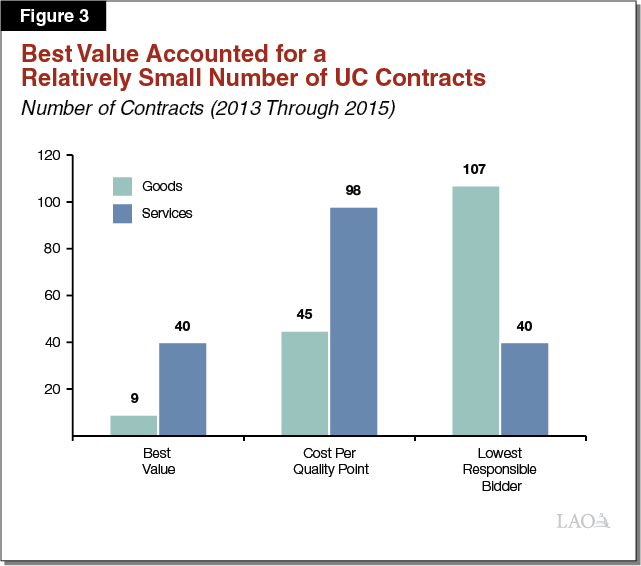

UC Used BV for Relatively Few Purchases During the Pilot Period. From 2013 through 2015, UC reported 339 contracts of $100,000 or more. As Figure 3 shows, UC used BV evaluation for 49 (or 14 percent) of these contracts. Nearly three times as many contracts (143 or 42 percent) were awarded using UC’s older BV‑like approach, CPQP. The remaining contracts (147 or 43 percent) were awarded using LRB. Based on our discussions with UC campuses, the low utilization of BV appears to be in large part a result of some campuses having been more accustomed to CPQP.

UC Used BV and CPQP Primarily to Purchase Services. About 80 percent of UC’s BV contracts and 70 percent of CPQP contracts were for services. By contrast, a much smaller share of LRB contracts—about 25 percent—were for services. We note that the services procured using BV and CPQP tended to be somewhat more complex than services procured using LRB. For example, one campus used BV to procure the services of a firm to conduct a large‑scale research survey but used LRB to procure beverage pouring rights.

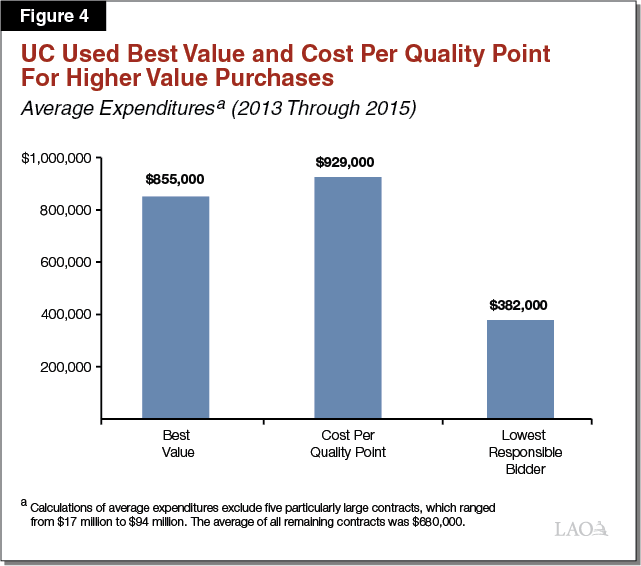

BV and CPQP Purchases Were Larger on Average Than LRB Purchases. BV and CPQP contracts tended to be much higher value contracts than LRB contracts. Specifically, among the 339 contracts reported, the average expenditure per contract was $1.34 million. Notably, five contracts were particularly large—two BV contracts (both for IT systems), two CPQP contracts (one for dining services and one for solar energy), and one LRB contract (for general laboratory supplies). These particularly large contracts ranged from $17 million to $94 million. Excluding these contracts, Figure 4 shows that the average expenditure per BV contract ($855,000) and CPQP contract ($929,000) were still more than twice the average spent on LRB contracts ($382,000).

More Campuses Used CPQP Than BV. As noted previously, both approaches were used in large part to procure services and average spending per contract was similar between the approaches. Seven campuses, one medical center, and UCOP used BV. (Two campuses and four medical centers did not.) By comparison, all ten campuses and five medical centers used CPQP. (Only UCOP did not.) While some campuses used a combination of both approaches, others relied more heavily on one or the other. The reporting period ended in 2015, and it is our understanding that some campuses are now moving toward BV and away from CPQP.

Assessment

Below, we assess UC’s BV policies and evaluation criteria, BV contract costs, and bid protests. Figure 5 summarizes the key points of our assessment in each of these areas.

Figure 5

Summary of Assessment of UC Best Value (BV) Pilot

|

Policies and Evaluation Criteria |

|

|

|

|

Costs |

|

|

|

Bid Protests |

|

Policies and Evaluation Criteria

UC’s Procurement Policies, Which Include BV, Are Generally Reasonable . . . UC’s written procurement policies, including those that cover overall procurement as well as BV, are consistent with the requirements of Chapter 708. Specifically, the overall procurement policy notes the ways in which procurement efforts should seek to reduce UC’s costs and fulfill UC’s strategic sourcing goals. Additionally, the policies on BV discuss the requirement to include evaluation criteria in the solicitation materials and inform in writing the bidders not awarded contracts. The definition of BV evaluation criteria also includes a reference to the statutory guidelines about the types of criteria that may be used. Furthermore, UC’s policies include the following provisions that, while not required by statute, are supported by studies on BV procurement:

- For all procurement approaches, bidders may not correct an error in their proposal after submission if it would give them a material advantage.

- For BV and CPQP, proposals will typically be scored by an evaluation team.

- For BV and CPQP, the total number of points and points per criterion must be determined by the evaluation team before opening any bids. (For BV, this includes the weight for price.)

. . . But Should Include Additional Guidance About BV Implementation. Although we believe UC’s policies are generally reasonable and consistent with Chapter 708 requirements, UC’s policies lack certain guidance about implementing the BV approach that could be particularly beneficial to campuses. Specifically, UC’s policies do not incorporate various best practices, such as the following:

- Separating bidders’ cost sheets from their narrative proposals (to minimize biases that may occur from reviewing the narrative with knowledge of the bidders’ prices).

- Conducting blind reviews when possible (removing the name of the bidder from the bidding materials).

- Preventing evaluators from changing their scores or throwing scores out.

- Preventing evaluators from seeking outside information about a bidder or bidder’s proposal (an exception is contacting references provided by the bidder).

- Providing all bidders with the answers to questions asked by any single bidder about the solicitation.

- Including people from various departments (or campuses if the procurement is systemwide) on the evaluation team to minimize personal, departmental, or campus biases.

Though some campuses have instituted some of these best practices on their own, UC has not endorsed them systemwide. Additional systemwide guidance in these areas would help ensure procurement staff across all the campuses conduct the BV process as fairly as possible.

BV Vendors Generally Selected Based on Core Set of Reasonable Evaluation Criteria. Based on our review of contract information provided by UC, the campuses that used BV generally appeared to evaluate prospective suppliers’ proposals using criteria that are consistent with the pilot’s statutory direction on the criteria that may be considered. For example, in addition to cost, campuses commonly considered the quality and effectiveness of the goods or services, which might include a firm’s technical capabilities, vendor experience, sustainability practices, and warranties. In addition, in several instances, campuses considered staffing capabilities and expertise. For the contracts we reviewed, the criteria selected by campuses generally appeared reasonable for the types of goods and services being purchased.

Costs

Majority of BV Contracts Awarded to Lowest Bidder. Based on additional information we requested from UC about BV procurements, we found that two‑thirds of the BV contracts (32 of 49) were awarded to the lowest bidder.

Remainder of BV Contracts Cost More Up Front. When UC did not select the lowest bidder in a BV procurement, the contract award cost on average 16 percent more than the lowest bid. Whether such an additional up‑front cost is warranted depends upon the Legislature’s evaluation of the qualitative benefits and long‑term fiscal effects of the contracts. In the case of these UC contracts, some qualitative benefits likely were achieved. For example, it appears that winning bidders scored higher than other bidders on quality (such as account management, reporting, and warranty), technical capabilities (such as innovative solutions and design), and previous experience. In some cases, these contracts also could result in long‑term savings. For example, UC may be able to avoid future costs in cases where the winning bidder offered a better service warranty than the lowest bidder.

Bid Protests

Bid Protests Are Rare. One concern about BV is that bidders will be more likely to protest contract award decisions given the more subjective nature of the evaluation. This is because protests typically happen when a bidder believes there is something improper about the solicitation or award. Chapter 708 required reporting and evaluation of bid protests during the pilot to determine whether BV led to more protests than LRB. Per UC policy, protests must be made in writing within two calendar weeks of the solicitation (if the protest is about the RFP) or award announcement. UC reported just five protests among the 339 contracts awarded during the pilot. While all of these protests were associated with BV procurements, the rarity of protests makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about which approach results in more bid protests. Additionally, the five protests reported by UC do not raise major concerns. Based on the information provided, they appear to have been either Public Records Act (PRA) requests or resolved amicably by campus staff. The staff to whom we spoke said that bidders will often make PRA requests as part of their competitive research—that is, to learn more about competitors’ pricing—rather than to protest an award.

Recommendations

Below, we make three recommendations relating to the UC BV pilot.

Provide UC With Permanent BV Authority. Based on the results of the UC pilot, we recommend the Legislature provide UC with permanent BV authority for the procurement of goods and services. We believe that UC used BV in an appropriate manner. Importantly, BV appears to give UC the flexibility to select vendors that meet its needs. Moreover, UC often selected the lowest bidder even when using the BV method. Finally, making BV authority permanent would allow UC to work more easily with private vendors who are more accustomed to BV than CPQP.

Require UC to Develop More Comprehensive BV Policies Based on Best Practices. Prior to making BV authority permanent for UC, we recommend the Legislature require UC to develop a more comprehensive written set of policies that reflect best practices for BV procurement. To promote transparency in procurement, this revised policy should be available on UC’s website for the vendor community and public to access. The more comprehensive set of policies should provide campuses with additional implementation guidance to help ensure campuses use BV as consistently, fairly, and impartially as possible. The expanded guidance should include some or all of the best practices mentioned earlier, such as conducting blind evaluations and sharing information about any questions asked during solicitation.

Have UC Phase Out CPQP. We believe UC’s former procurement practice that evaluated noncost factors—CPQP—is simply a form of BV that is no longer needed if UC has permanent BV authority. Moreover, CPQP is not an industry‑recognized practice, such that it could be serving to discourage certain prospective bidders from competing for awards. It also is an inferior approach, in that the effect of price on the final award desision is much harder to understand. For these reasons, we recommend that in granting BV authority, the Legislature have UC phase out CPQP.

Conclusion

Different Conclusions Reached for the Two Pilot Programs. The state currently does not have consistent policies for how public agencies may procure goods and services. Whereas the state has granted several public agencies permanent authority to use BV for procuring goods and services, it granted such authority to CCC and UC only on a pilot basis. Based upon our review of UC’s use of BV authority for the procurement of goods and services, we have no major concerns with making this authority permanent for UC. Though we think permanent authority might someday be appropriate for CCC too, CCC to date has not provided data to the Legislature demonstrating that it knows how to use BV and would use the procurement method appropriately. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature extend the duration of the pilot for CCC. Once more contract data are available, the Legislature could revisit the issue of whether to make BV authority permanent for CCC.