LAO Contact

- Senate Bill 1 Funding

- Caltrans

- California Highway Patrol

- Motor Vehicle Account

- Department of Motor Vehicles

February 8, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Transportation Proposals

- Introduction

- Overview of the Governor’s Budget

- Cross‑Cutting Issues

- Caltrans

- California Highway Patrol

- Department of Motor Vehicles

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overview. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $22.5 billion from all fund sources for transportation departments and programs in 2018‑19. This is an increase of $4.2 billion, or 23 percent, over estimated expenditures for the current year. Specifically, the budget includes $13.6 billion for the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), $2.7 billion for local streets and roads, $2.6 billion for the California Highway Patrol (CHP), $1.2 billion for the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), $1.1 billion for the High‑Speed Rail Authority, and $1.3 billion for various other transportation programs. In this report, we assess the Governor’s budget proposals in the transportation area. Below, we summarize our major findings and recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA) Fund Condition. The MVA, which receives most of its revenues from vehicle registration and driver license fees, mainly supports the activities of CHP and DMV. The administration’s five‑year projection (2018‑19 through 2022‑23), which reflects expenditures already approved by the Legislature and those proposed in the Governor’s budget, estimates that the MVA will have operating surpluses over the next several years. The administration projects that the MVA would maintain a reserve for economic uncertainties of approximately 11 percent of projected expenditures in 2018‑19 and about 8 percent in the following years. We note that various additional cost pressures could affect the condition of the MVA over the next several years.

Caltrans. The Governor’s budget provides $2.8 billion in revenues from the increased fuel taxes and vehicle fees established in Chapter 5 of 2017 (SB 1, Beall) for Caltrans programs. The budget distributes the funding according to formulas contained in the legislation. Of the $2.8 billion, about $1.6 billion is available for appropriation between the State Highway Operations and Protection Program (which pays for replacing or rehabilitating sections of highways) and the Highway Maintenance Program (which funds preventive measures to keep highways from deteriorating). The Governor’s budget provides $994 million for highway rehabilitation and replacement, versus $576 million for maintenance. Our assessment indicates both programs require additional funding to keep highways in good condition. We recommend that the Legislature, however, consider modifying the Governor’s proposal to weight additional funding toward highway maintenance since it can save money in the long term by delaying the need for highway rehabilitation and replacement projects.

The budget also includes $99 million in other spending proposals for the department. We recommend the Legislature require Caltrans to provide additional information on proposals related to compensation funding, liability cost increases, and implementing a road usage charge pilot program, prior to taking action on these proposals. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed budget bill language authorizing the Department of Finance to increase Caltrans’ budget by up to $12 million after the enactment of the budget to replace information technology (IT) equipment. Instead, we recommend the Legislature require Caltrans to submit a plan for equipment replacements during 2018‑19 for legislative review.

CHP. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift from a “pay‑as‑you‑go” approach for the design‑build phase of four previously approved CHP area office replacement projects to financing the projects with lease revenue bonds supported from the MVA. According to the administration, this approach would allow the projects to continue and ensure the MVA can maintain an adequate reserve. While adopting the Governor’s lease revenue bond approach would lock in some future MVA costs, funding the projects using a pay‑as‑you‑go approach would significantly reduce the projected reserve levels discussed above.

DMV. The Governor’s budget proposes a multiyear funding plan for the implementation of a major new IT project, with $15 million requested for 2018‑19. While modernizing DMV’s IT systems has merit and is consistent with legislative direction, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposal as it is premature to provide the requested implementation funding prior to completion of the planning process for the project.

The Governor’s budget also proposes to consolidate several DMV investigations offices into a new leased facility at a location yet to be determined. While the proposed consolidation is consistent with recent legislative actions and could allow for more efficient operations, we recommend that the Legislature require DMV to provide information at budget hearings that justifies the proposed square footage and staffing level for its proposed consolidated investigations office. To the extent the Legislature approves the proposed consolidation, we recommend that it only approve the planning funds for 2018‑19 and reject the proposed out‑year funding for moving and lease costs. This would allow the department to initiate site selection and request funding for moving and lease costs as part of the 2019‑20 budget process with a more precise estimate of such costs.

Introduction

The state budget provides funding for six transportation departments: the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the California Highway Patrol (CHP), the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), the High‑Speed Rail Authority (HSRA), the California Transportation Commission (CTC), and the Board of Pilot Commissioners. The state budget also provides funding for the California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA), which has jurisdiction over these six departments and is responsible for coordinating the state’s transportation policies and programs. In addition, the state budget provides funding to local governments for transportation purposes through “shared revenues” for local streets and roads and the State Transit Assistance (STA) program.

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for these departments and programs. We begin by providing an overview of the Governor’s proposed budget for each department and program. In the next section, we discuss two cross‑cutting state transportation issues: (1) funding from the tax and fee increases authorized by Chapter 5 of 2017 (SB 1, Beall), and (2) an update on the condition of the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA). In the following three sections, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for Caltrans, CHP, and DMV. In each of these sections, we provide relevant background, describe the proposals, assess the proposals, and identify issues and recommendations for legislative consideration. The final section consists of a summary of the recommendations we make throughout the report.

Overview of the Governor’s Budget

Figure 1 shows the Governor’s proposed spending for the state’s transportation departments and programs from all fund sources, including the General Fund, state special funds, bond funds, federal funds, and reimbursements. In total, the Governor’s budget proposes $22.5 billion in expenditures for all departments and programs in 2018‑19. This is an increase of $4.2 billion, or 23 percent, over estimated expenditures for the current year. The increase primarily reflects the new funding for several transportation departments and programs from SB 1. Below, we describe the major changes by department.

Figure 1

Transportation Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual 2016‑17 |

Estimated 2017‑18 |

Proposed 2018‑19 |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Department/Program |

|||||

|

Department of Transportation |

$9,138 |

$11,328 |

$13,617 |

$2,289 |

20% |

|

Local Streets and Roads |

1,277 |

1,783 |

2,738 |

955 |

54 |

|

California Highway Patrol |

2,340 |

2,415 |

2,592 |

177 |

7 |

|

Department of Motor Vehicles |

1,059 |

1,141 |

1,168 |

27 |

2 |

|

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

733 |

284 |

1,133 |

849 |

299 |

|

State Transit Assistance |

339 |

707 |

855 |

149 |

21 |

|

California State Transportation Agency |

322 |

607 |

366 |

‑241 |

‑40 |

|

California Transportation Commission |

10 |

15 |

15 |

—a |

1 |

|

Board of Pilot Commissioners |

2 |

2 |

2 |

—a |

—a |

|

Totals |

$15,221 |

$18,282 |

$22,487 |

$4,205 |

23% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$8,901 |

$11,628 |

$14,809 |

$3,181 |

27% |

|

Federal funds |

4,813 |

5,209 |

5,802 |

593 |

11 |

|

Reimbursementsb |

1,075 |

1,084 |

1,236 |

152 |

14 |

|

Bonds funds |

427 |

356 |

638 |

281 |

79 |

|

General Fund |

4 |

5 |

3 |

‑2 |

‑39 |

|

Totals |

$15,221 |

$18,282 |

$22,487 |

$4,205 |

23% |

|

aLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. bPrimarily local government payments to Caltrans for roadwork activities. |

|||||

Caltrans. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $13.6 billion in 2018‑19 for Caltrans—$2.3 billion, or 20 percent, higher than estimated current‑year expenditures. About $878 million of the increase is from new revenues generated by SB 1. (This is on top of $1.9 billion in SB 1 funding included in the 2017‑18 budget for Caltrans, bringing total SB 1 funding for Caltrans to $2.8 billion in 2018‑19.) The remainder mainly reflects an assumption that a greater amount of expenditures will be spent in the budget year rather than in the current year (as was previously assumed). The budget also proposes $99 million in new spending proposals for the department, including to pay for certain cost increases, perform new federally mandated workload, and upgrade information technology (IT).

CHP. The budget proposes $2.6 billion for CHP in 2018‑19, which is $177 million, or 7 percent, greater than the current‑year estimated level. The increase mainly reflects an assumption that funding to replace various CHP field offices will be spent in the budget year rather than in the current year (as was previously assumed). The budget also proposes to shift from a pay‑as‑you‑go approach to funding these projects with lease revenue bonds.

DMV. For DMV, the Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $1.2 billion—$27 million, or 2 percent, greater than estimated current‑year expenditures. About $18 million of the proposed increase is to pay for new IT software and hardware.

HSRA. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $1.1 billion in 2018‑19 for HSRA. This amount is $849 million, or three times, more than the estimated level of expenditures in the current year. The increase primarily reflects the carryover of funds from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund—which receives revenue from cap‑and‑trade allowance auctions—that were previously appropriated but not spent in prior years.

Local Streets and Roads and State Transit Assistance. The budget proposes $2.7 billion in shared revenues for local streets and roads—a 54 percent increase over estimated current‑year expenditures. For STA, the budget proposes $855 million—a 21 percent increase. The increases for both programs reflect new funding from SB 1.

CalSTA. The Governor’s budget proposes $366 million for CalSTA, a $241 million, or 40 percent, decrease from the current year. The year‑to‑year decrease reflects an assumption that a greater amount of Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funds will be spent in the current year rather than in the prior year (as was previously assumed). These funds support a transit and intercity rail grant program administered by CalSTA.

CTC and Board of Pilot Commissioners. The Governor’s budget proposes $15 million for CTC and $2 million for the board—about the same level of spending as the current year. The budget includes only a few small adjustments for these two departments.

Transportation Bond Debt Service. In addition to the department and program expenditures identified in Figure 1, the state also pays debt service costs on transportation bonds. For 2018‑19, the budget assumes $1.8 billion in spending on debt service, about the same as the estimated current‑year level. (We note that this spending relates to repaying bonds issued primarily to fund expenditures made in prior years.) Most of the proposed spending—$1.3 billion—is to repay Proposition 1B (2006) bonds that support various highway, local road, and transit projects. Another $366 million is to repay Proposition 1A (2008) bonds for the high‑speed rail project. Funding for debt service primarily comes from truck weight fee revenues. The budget assumes these revenues provide $1.4 billion (including $324 million in weight fee loan repayments from the General Fund). Another $278 million for debt service comes from the General Fund.

Cross‑Cutting Issues

Senate Bill 1 Funding

In April 2017, the Legislature passed SB 1 to increase state funding for California’s transportation system, including state highways, local streets and roads, and transit. Below, we (1) provide background on the legislation, (2) review the Governor’s proposals for SB 1 revenues and spending, and (3) provide an update on program implementation.

Background

Funding for California’s highways, local streets and roads, and transit systems comes from numerous state, local, and federal sources. State funding mainly comes from several fuel taxes and vehicle fees. In 2016‑17, state funding for transportation programs totaled about $7.2 billion. In order to help address the state’s transportation needs, the Legislature passed SB 1 to increase state funding levels. Specifically, this legislation increased several fuel taxes and vehicle fees and dedicated the funding to transportation programs according to various formulas.

Tax and Fee Increases. Senate Bill 1 increased existing excise taxes on gasoline as well as existing excise and sales taxes on diesel. Additionally, the legislation created two new vehicle fees: (1) a transportation improvement fee that varies depending on the value of the vehicle, and (2) a supplemental registration fee for zero‑emission vehicles (such as electric cars) model year 2020 and later. Figure 2 summarizes these taxes and fees. The legislation phases them in over time, with most already having taken effect. In addition, SB 1 provides $706 million in loan repayments from the General Fund to transportation programs over three years.

Figure 2

Senate Bill 1 Increased Several Taxes and Fees

|

Old Rates |

New Ratesa |

Effective Date |

|

|

Fuel Taxesb |

|||

|

Gasoline |

|||

|

Base excise |

18 cents |

30 cents |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Variable excisec |

variable |

17.3 cents |

July 1, 2019 |

|

Diesel |

|||

|

Excisec |

variable |

36 cents |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Sales |

1.75 percent |

5.75 percent |

November 1, 2017 |

|

Vehicle Feesd |

|||

|

Transportation Improvement Fee |

— |

$25 to $175 |

January 1, 2018 |

|

ZEV registration fee |

— |

$100 |

July 1, 2020 |

|

aAdjusted for inflation starting July 1, 2020 for the gasoline and diesel excise taxes, January 1, 2020 for the Transportation Improvement Fee, and January 1, 2021 for the ZEV registration fee. The diesel sales taxes are not adjusted for inflation. bExcise taxes are per gallon. cVariable rates set annually by the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. The current gasoline variable excise tax rate is 11.7 cents. The rate has ranged from 9.8 cents to 21.5 cents in prior years. The most recent diesel excise tax rate was 16 cents. This rate ranged from 10 cents to 18 cents in prior years. Senate Bill 1 converts both variable rates to fixed rates. dPer vehicle per year. Both fees are new, though the state levies other similar fees on vehicles, such as vehicle license fees and registration fees. ZEV = zero‑emission vehicle. |

|||

Formulas for Distributing Revenues. Senate Bill 1 created a series of formulas to distribute the revenues from the new taxes and fees to different transportation programs and purposes. In most cases, the formulas split the revenues based on fixed percentages, but in some cases the legislation sets aside fixed dollar amounts for certain programs. Though the formulas dedicate funding specifically for highway repairs, they do not distinguish between highway maintenance (such as filling potholes) and highway rehabilitation (such as rebuilding a stretch of road). The split between highway maintenance and rehabilitation instead is left up to the annual budget act.

Governor’s Proposals

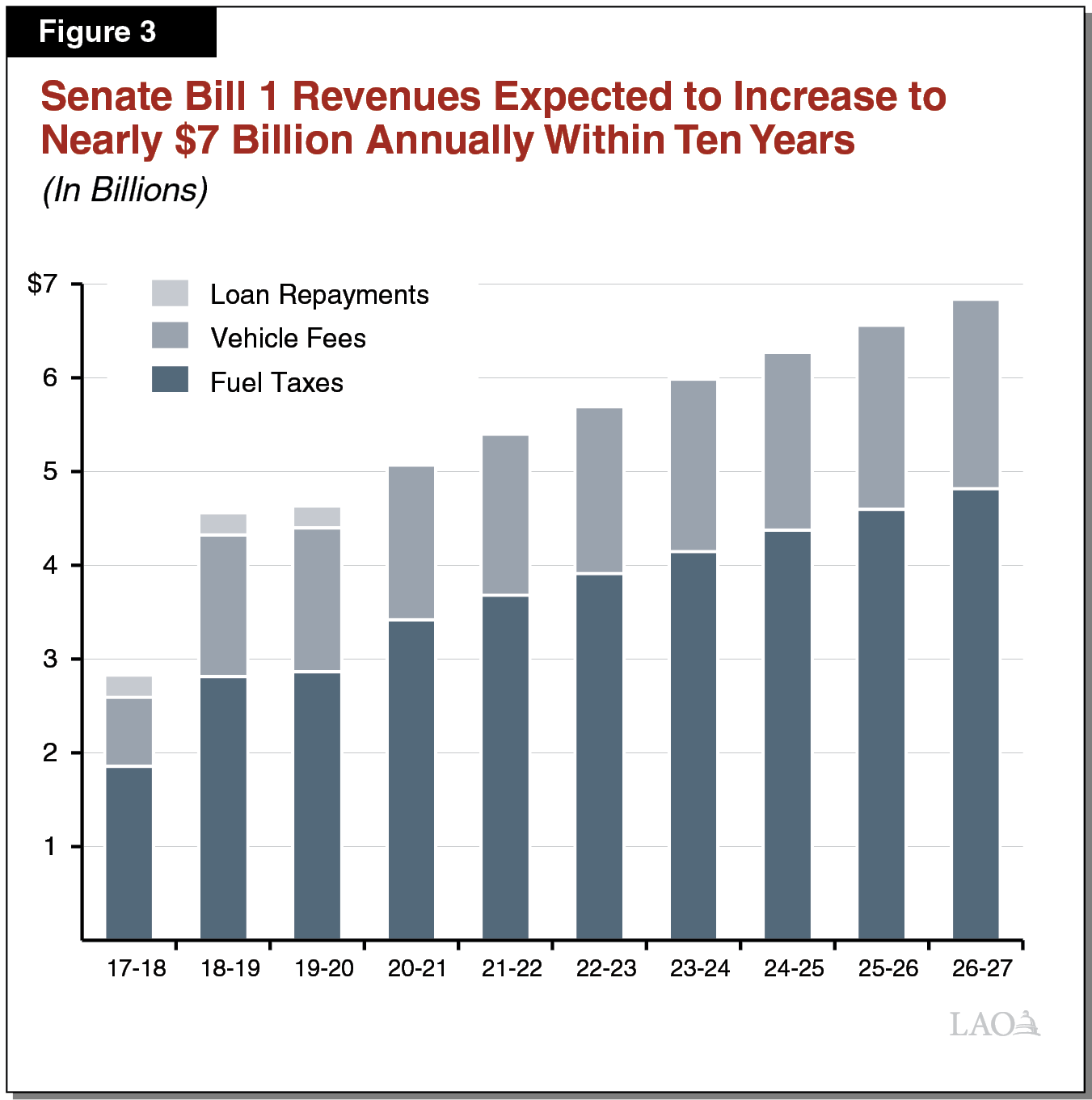

Revenue Estimates. The administration estimates that the tax and fee increases and loan repayments will provide $2.8 billion in 2017‑18, increasing to $4.6 billion in 2018‑19, and $6.8 billion annually within ten years. Figure 3 shows the administration’s revenue estimates over the next decade. The administration expects revenues to increase steadily even after all taxes and fees take effect, primarily because SB 1 adjusts the tax and fee rates annually to account for inflation. These estimates are not notably different than the administration’s estimates from May 2017, just after the legislation was enacted.

Spending Increases. The Governor’s budget distributes the new revenues to various transportation programs according to the formulas in SB 1. Figure 4 shows the administration’s spending estimates for 2018‑19 by program area. About two‑thirds of SB 1 funding supports highways and local streets and roads, while another quarter supports either transit programs or multimodal programs (that can support a combination of roadway and transit projects). The remainder primarily supports active transportation programs, which fund projects such as pedestrian crosswalks and bicycle lanes. The Governor’s budget also contains a proposal to allocate funding between highway maintenance and rehabilitation, which we discuss in the “Caltrans” section of this report.

New Program Implementation

Senate Bill 1 primarily funds existing transportation programs (though in many cases it adds new requirements to them). For new programs, the legislation tasks CTC and CalSTA with creating guidelines for transportation agencies to receive funding. For instance, the legislation requires the CTC to create a process for allocating funding for the new Solutions for Congested Corridors program that balances transportation, environmental, and community access objectives. Figure 5 shows the CTC’s and CalSTA’s progress toward implementing guidelines and selecting projects for new programs. As shown, they have developed guidelines for all new programs and expects to select projects for all programs by this spring.

Figure 5

Senate Bill 1 New Program Implementation Timeline

As of November 2017

|

Implementing Department/Program |

Guidelines Adopted |

Project Selection |

|

California Transportation Commission |

||

|

Local Partnership Program |

October 2017 |

January/March 2018 |

|

Trade Corridor Enhancement Program |

October 2017 |

May 2018 |

|

Solutions for Congested Corridors Program |

December 2017 |

May 2018 |

|

California Secretary of Transportation |

||

|

State Rail Assistance Program |

October 2017 |

February 2018 |

Senate Bill 1 also includes several provisions aimed at ensuring funds are spent efficiently and achieve legislative goals. These provisions include:

- Caltrans Efficiencies. The legislation requires Caltrans to achieve $100 million in savings annually from operating more efficiently. The Governor’s budget summary indicates that Caltrans will generate “considerably more” savings than expected by reducing overhead costs, accelerating projects, streamlining environmental reviews, and implementing other changes. The budget indicates that the department plans to provide additional detail at an upcoming CTC meeting.

- Independent Audits and Investigations. Senate Bill 1 established a new independent Office of Audits and Investigations within Caltrans to ensure its contractors (including local agencies) spend funding efficiently, economically, and in compliance with state and federal requirements. The 2017‑18 budget provided 58 positions to staff the new office (including 10 new positions and 48 positions redirected from an existing internal audit office within the department), and, in October 2017, the Governor appointed an Inspector General to direct the office’s work. According to Caltrans officials, the office is still developing its procedures for selecting audits and investigations to perform.

- Preliminary Performance Outcomes. Senate Bill 1 states legislative intent for Caltrans to achieve five outcomes by the end of 2027. These outcomes are (1) at least 98 percent of state highway pavement in good or fair condition; (2) at least 90 percent level of service for maintenance of potholes, spalls, and cracks; (3) at least 90 percent of culverts in good or fair condition; (4) at least 90 percent of transportation management system units in good or fair condition; and (5) at least an additional 500 bridges fixed. Caltrans is to report annually to the CTC on its progress in meeting the outcomes, and the CTC, in turn, is to evaluate Caltrans’ progress toward the outcomes and include any findings in its annual report to the Legislature. In June 2017, the CTC adopted a requirement for Caltrans to report quarterly on its progress in meeting the targets.

MVA Fund Condition

The MVA supports the state administration and enforcement of laws regulating the operation and registration of vehicles used on public streets and highways, as well as the mitigation of the environmental effects of vehicle emissions. Below, we (1) provide background information on MVA revenues and expenditures, (2) review the Governor’s proposals related to the MVA, and (3) assess the condition of the MVA.

Background

Revenues. The MVA receives most of its revenues from vehicle registration fees. In 2017‑18, the MVA is expected to receive a total of $3.7 billion in revenues, with vehicle registration fees accounting for $3.2 billion (87 percent). Vehicle registration fees currently total $83 for each registered vehicle, consisting of two components:

- Base Registration Fee ($58). The state charges a base registration fee of $58, with $55 dollars going to the MVA and $3 going to support certain environmental mitigation programs. The state last increased the base registration fee in 2016, when it increased the fee by $10 (from $46 to $56). At the same time, the state indexed the fee to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), thereby allowing it to automatically increase with inflation moving forward. The inflation adjustment for 2018 increased the fee to the current $58.

- CHP Fee ($25). The state also charges an additional fee of $25 that directly supports CHP. The state last increased this fee in 2014, when it increased the fee by $1 (from $23 to $24) and indexed it to the CPI. The inflation adjustment for 2018 increased the fee to the current $25.

The MVA also receives revenues from driver license fees. These revenues tend to fluctuate based on the number of licenses renewed each year. For 2017‑18, the state is expected to collect $300 million from these fees. The current fee is $35. The remaining MVA revenues primarily come from late fees, identification card fees, and miscellaneous fees for special permits and certificates (such as fees related to the regulation of automobile dealers and driver training schools).

Expenditures. The California Constitution restricts most MVA revenues to supporting the administration and enforcement of laws regulating the use of vehicles on public highways and roads, as well as the mitigation of the environmental effects of vehicle emissions. Accordingly, the MVA primarily provides funding to three state departments—CHP, DMV, and the Air Resources Board (ARB). Funding supports staff compensation, department operations, and capital expenses on department facilities. For 2017‑18, a total of $3.7 billion is expected to be spent from the MVA, mostly to support CHP and DMV.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget estimates the MVA will receive a total of $3.9 billion in revenues in 2018‑19 and proposes a total of $3.8 billion in expenditures. The budget proposes a total of $3.4 billion from the MVA for CHP, DMV, and ARB—about 91 percent of total MVA expenditures. A small share of MVA revenues (from miscellaneous fees) are not restricted by the State Constitution. Because they are available for broader purposes, the state typically transfers these revenues to the General Fund. In 2018‑19, the Governor’s budget assumes this transfer totals $89 million.

The Governor’s budget includes various new spending proposals that would affect MVA expenditures in 2018‑19 and, in some cases, beyond. Some of the proposals include:

- Environmental Mitigation Activities at the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW). The Governor’s budget proposes $18 million in new, ongoing funding from the MVA to support workload at DFW resulting from the impacts of roads and vehicles on fish and wildlife, such as fragmented habitat, impeded stream flows, spills on roadways, and wildlife‑vehicle collisions.

- DMV Capital Outlay. The Governor’s budget appropriates $7.9 million from the MVA to (1) advance previously approved projects to replace or renovate certain DMV field offices and (2) support the design and construction of perimeter fences at 13 existing state‑owned DMV field offices.

- DMV IT Proposals. The administration proposes $15 million in 2018‑19 to begin implementing a multiyear IT project to replace the software DMV uses for vehicle registration and the collection of fees. In addition, the budget includes $3.1 million on a one‑time basis for DMV to replace critical IT hardware that has reached the end of its useful life.

- CHP Vehicle Fleet and Radio Console Replacement. The budget includes $4.5 million on an ongoing basis to replace CHP’s enforcement vehicles. The budget also provides $3.9 million to support a multiyear plan to replace the dispatch radio consoles at CHP communications centers.

As we discuss in more detail in the “California Highway Patrol” section of this report, the state has typically funded the replacement of CHP area offices from the MVA on a “pay‑as‑you‑go” basis. The Governor’s budget proposes to finance the replacement of four CHP offices with lease revenue bonds, rather than as with pay‑as‑you‑go as they were initially approved by the Legislature. According to the administration, this change would allow the projects to continue and ensure the MVA can maintain an adequate reserve.

MVA Currently Balanced but Additional Cost Pressures Could Arise

The Department of Finance’s five‑year projection (2018‑19 through 2022‑23) estimates that the MVA will have operating surpluses over the next several years. These projections reflect expenditures already approved by the Legislature and those proposed in the Governor’s budget, as well as identified in the administration’s 2018 Five‑Year Infrastructure Plan. According to the administration, the MVA fund balance will be $429 million in 2018‑19, falling to $336 million in 2019‑20 and stabilizing thereafter. This balance represents approximately 11 percent of projected expenditures in 2018‑19 and about 8 percent in the following years. This is equivalent to slightly more than one month of MVA expenditures, and seems reasonable as a balance for this account.

We note that various additional cost pressures could affect the condition of the MVA over the next several years, including:

- Supplemental Pension Plan Payments. As part of the 2017‑18 budget package, Chapter 50 (SB 84, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) approved a plan to borrow $6 billion from the state’s cash balances to make a one‑time supplemental payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). All funds that make employer contributions to CalPERS—including the MVA—will repay a share of this loan. The administration accounts for these annual repayments in its MVA projections, forecasting modest growth in these expenditures from $59 million in 2018‑19 to $69 million in 2022‑23. (Over the next 30 years, the SB 84 plan anticipates that the MVA is likely to receive savings that outweigh these near‑term loan repayment expenditures, due to slower growth in employer pension contributions.) The projected expenditures, however, could be higher in the coming years depending on how the loan repayments are structured.

- Deferred Maintenance Costs. According to the Governor’s five‑year infrastructure plan, DMV and CHP have deferred maintenance backlogs totaling $11 million and $39 million, respectively. Because the administration lacks a plan to ensure that routine maintenance is adequately funded on an ongoing basis, this maintenance backlog could grow and place additional pressure on the MVA.

- CHP Officer Salaries and Benefits. The state and the union representing CHP officers last negotiated a memorandum of understanding (MOU) in 2013, which provided salary increases annually through 2018‑19. The administration’s projections for CHP expenditures assume ongoing compensation increases after 2018‑19 in line with historical growth. These costs could turn out to be greater depending on the provisions of a new MOU.

- New Federal or State Requirements. Legislatively enacted requirements at the state or federal level can result in additional workload and costs for state departments. For example, the federal REAL ID Act, which required states to implement certain driver license and identification card issuance procedures and security enhancements to prevent fraud, has resulted in new workload and funding requirements for DMV. Future legislative action could lead to additional requirements and cost pressures at CHP, DMV, or ARB.

Caltrans

Caltrans is responsible for planning, coordinating, and implementing the development and operation of the state’s transportation system. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $13.6 billion for Caltrans in 2018‑19. This is $2.3 billion, or 20 percent, higher than the estimated current‑year expenditures. Figure 6 shows proposed expenditures by program and fund source. Most spending supports the department’s highway program and comes from various state special funds (which mainly receive revenues from fuel taxes and vehicle fees) as well as federal funds. The total level of spending proposed for Caltrans in 2018‑19 supports about 19,500 positions.

Figure 6

Caltrans Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual 2016‑17 |

Estimated 2017‑18 |

Proposed 2018‑19 |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Program |

|||||

|

Highways |

|||||

|

Capital outlay projects |

$3,370 |

$3,258 |

$4,595 |

$1,337 |

41% |

|

Local assistance |

1,715 |

2,728 |

3,393 |

665 |

24 |

|

Maintenance |

1,442 |

1,992 |

2,187 |

195 |

10 |

|

Capital outlay support |

1,658 |

1,852 |

1,858 |

6 |

— |

|

Other |

434 |

467 |

494 |

27 |

6 |

|

Subtotals |

($8,619) |

($10,297) |

($12,527) |

($2,230) |

(22%) |

|

Mass transportation |

$364 |

$729 |

$779 |

$50 |

7% |

|

Othera |

156 |

302 |

312 |

9 |

3 |

|

Totals |

$9,138 |

$11,328 |

$13,617 |

$2,289 |

20% |

|

Fund Source |

|||||

|

Special funds |

$3,439 |

$5,256 |

$6,607 |

$1,351 |

26% |

|

Federal funds |

4,603 |

4,992 |

5,681 |

690 |

14 |

|

Reimbursementsb |

939 |

948 |

1,100 |

152 |

16 |

|

Bond funds |

158 |

132 |

229 |

96 |

73 |

|

Totals |

$9,138 |

$11,328 |

$13,617 |

$2,289 |

20% |

|

aIncludes Aeronautics, Planning, and Office of Inspector General. bPrimarily payments from local governments for roadwork activities. |

|||||

Governor’s Proposals. Of the $2.3 billion proposed increase in expenditures, about $878 million relates to SB 1 implementation and $99 million relates to other budget proposals. Figure 7 summarizes these proposals. The remainder of the year‑to‑year increase mainly reflects an assumption that a greater amount of expenditures will be spent in the budget year rather than in the current year (as was previously assumed). Below, we discuss the Governor’s proposals related to (1) SB 1 funding for highway maintenance and repairs, (2) a compensation cost adjustment, (3) liability cost increases, (4) IT upgrades, and (5) a road usage charge pilot program.

Figure 7

Governor’s Proposals for Caltrans

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

Proposed 2018‑19 |

Out‑Year Costsa |

|

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

||

|

Implement Senate Bill 1 |

$878.2b |

$878.2 |

$878.2 |

|

Adjust compensation costs |

58.0 |

58.0 |

58.0 |

|

Upgrade information technology |

|||

|

Security |

$10.4 |

$2.1 |

$2.1 |

|

Equipment |

2.0c |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($12.4) |

($2.1) |

($2.1) |

|

Fund liability cost increases |

|||

|

Tort payments |

$7.0d |

$7.0 |

$7.0 |

|

Vehicle insurance |

4.9 |

4.9 |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($11.9) |

($11.9) |

($7.0) |

|

Continue existing workload |

|||

|

Continue Proposition 1B staffing |

$6.5 |

$5.9 |

— |

|

Continue legal work performed for HSRA |

— |

2.8 |

$2.8 |

|

Subtotals |

($6.5) |

($8.7) |

($2.8) |

|

Perform federally required activities |

|||

|

Highway safety plan |

$3.0 |

$1.5 |

$1.5 |

|

Tunnel inspections |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Highway spending audits |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Subtotals |

($4.7) |

($3.1) |

($3.1) |

|

Implement new road usage charge pilot program |

$3.2 |

$0.7 |

— |

|

Fund facilities cost increase |

2.1 |

4.4 |

$6.7 |

|

Totals |

$977.0 |

$967.2 |

$958.0 |

|

aReflects changes associated with limited‑term funding or full implementation costs. Does not reflect changes in SB 1 revenues expected in the out years. bThe Governor’s budget displays a $1.3 billion increase. The main reason the Governor’s figure is higher is because he treats all capital outlay spending as new in 2018‑19. cProposal allows the Department of Finance to increase by up to $12 million. dProposal allows the Department of Finance to increase by up to $20 million. HSRA = High‑Speed Rail Authority. |

|||

Senate Bill 1 Funding for Highway Maintenance and Repairs

Background

Caltrans Responsible for Maintaining and Rehabilitating Highway System. The state highway system includes about 50,000 lane‑miles of pavement, 13,100 bridges, and 205,000 culverts (pipes that allow water to flow beneath the roadway). Highway infrastructure is designed and built to have certain lifespans and requires maintenance and rehabilitation work at regular intervals over the course of a lifespan. Caltrans is responsible for maintaining and rehabilitating the state’s highway system and does so through two programs—the Highway Maintenance Program and the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP):

- Highway Maintenance Program. The Highway Maintenance Program is responsible for minor routine maintenance, such as landscaping, filling potholes, and bridge painting. This work is performed directly by Caltrans staff. The program also is responsible for major maintenance projects that entail more significant repairs, such as applying a thin overlay to a stretch of a state highway. These projects are typically performed by construction contractors and overseen by Caltrans staff.

- SHOPP. The SHOPP is a program of capital projects to rehabilitate or reconstruct highways when they reach the end of their useful life. Unlike the Highway Maintenance Program, SHOPP projects can involve tearing up and replacing an entire roadway or building a new bridge to replace an old one. SHOPP projects often require significant work by Caltrans staff to design and manage each project. The construction of SHOPP projects is done by a construction contractor.

Condition of the State Highway System. While the highway system is aging, the majority of it is still in good condition. In its last State of the Pavement report prior to the passage of SB 1, Caltrans reported that 53 percent of pavement was in good condition, 31 percent was in fair condition, and 16 percent was distressed. For bridges, it reported a “Bridget Health Index” of 97.1 out of 100—meaning on average the state’s bridges were in very good condition. Caltrans also reported, however, that about 500 highway bridges statewide were distressed (about 4 percent of total bridges). For culverts, the department reported that 60 percent were in good condition, 26 percent were in fair condition, and 14 percent were distressed.

Assessment of Maintenance and Rehabilitation Needs. In our report The 2016‑17 Budget: Transportation Proposals, we estimated Caltrans’ ongoing funding needs for major maintenance and SHOPP, as well as the size of project backlogs in both programs. Specifically, we estimated Caltrans would require about $2.6 billion annually to meet its ongoing major maintenance needs and clear its backlog of projects over three years. For SHOPP projects addressing pavement, bridges, and culverts, we estimated Caltrans would require $2.9 billion annually for ongoing needs and to clear the program’s backlog over the next ten years. These identified funding needs greatly exceeded Caltrans’ annual spending of $417 million for major maintenance and $1.3 billion for SHOPP projects addressing pavement, bridges, and culverts. To address the ongoing needs as well as the backlogs, we recommended the Legislature prioritize new funding for highway maintenance over SHOPP, because Caltrans estimates each dollar of major maintenance funding saves between $4 and $12 by postponing the need for rehabilitation.

Senate Bill 1 Increases Funding for Caltrans. In 2017‑18, SB 1 increased funding for Caltrans by $1.9 billion. Of this amount, SB 1 restricted $1.2 billion for specific programs, including $75 million for SHOPP (from a General Fund loan repayment). Under SB 1, the remaining $771 million was subject to appropriation in the annual budget act for either the Highway Maintenance Program or SHOPP (though the legislation specifies at least $400 million of this funding be spent specifically on bridges and culverts). The 2017‑18 Budget Act appropriated the funds as follows:

- Highway Maintenance Program ($421 Million). The budget provided (1) $400 million for Caltrans to contract for major maintenance services and (2) $21 million to support 48 positions and overtime for Caltrans staff to perform minor maintenance and oversee maintenance contracts.

- SHOPP ($424 Million). The budget provided $368 million to advance SHOPP projects awaiting funding. (This amount includes the $75 million that SB 1 dedicated specifically to SHOPP.) Additionally, it provided $56 million and 187 positions to initiate planning and to design additional SHOPP projects.

Senate Bill 1 Also Sets Performance Outcomes for Highway Conditions. In addition to dedicating funding for highway maintenance and rehabilitation, SB 1 established associated performance outcomes for Caltrans to achieve within ten years. These outcomes are (1) at least 98 percent of state highway pavement in good or fair condition; (2) at least 90 percent level of service for maintenance of potholes, spalls, and cracks; (3) at least 90 percent of culverts in good or fair condition; (4) at least 90 percent of transportation management systems in good or fair condition; and (5) at least an additional 500 bridges fixed. Caltrans is to report annually to the CTC on its progress in meeting the outcomes, and the CTC, in turn, is to evaluate Caltrans’s progress toward the outcomes and include any findings in its annual report to the Legislature.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget estimates SB 1 funding for Caltrans will increase from $1.9 billion in 2017‑18 to $2.8 billion in 2018‑19, as most of the legislation’s tax and fee increases were in effect for only part of the current year. This is an increase of $878 million, or 46 percent. Figure 8 summarizes the changes by program. Of the $2.8 billion in 2018‑19, SB 1 dedicates $1.2 billion to specific programs. The remaining $1.6 billion is available for appropriation in the budget act for either the Highway Maintenance Program or SHOPP. Of this $1.6 billion, the Governor proposes to spend somewhat more on SHOPP ($994 million) versus the Highway Maintenance Program ($576 million). According to the administration, its proposal accelerates as many SHOPP projects as currently await funding, and spends the remainder of the funding on maintenance. The administration indicates it envisions weighting more funding toward SHOPP in the future as new projects are developed. It believes its proposed level of funding for maintenance in the meantime will help Caltrans catch up on its maintenance work.

Figure 8

Senate Bill 1 Funding for Caltrans

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Program |

Estimated 2017‑18 |

Proposed 2018‑19 |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

SHOPPa |

$424 |

$994 |

$570 |

134% |

|

Highway Maintenance Program |

421 |

576 |

154 |

37 |

|

Transit/intercity rail capital |

330 |

330 |

— |

— |

|

Trade corridors |

153 |

306 |

153 |

100 |

|

Congested corridors |

250 |

250 |

— |

— |

|

Local partnerships |

200 |

200 |

— |

— |

|

Active transportation |

100 |

100 |

— |

— |

|

Local planning grants |

25 |

25 |

— |

— |

|

Freeway service patrols |

25 |

25 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$1,929 |

$2,807 |

$878 |

46% |

|

aIncludes $75 million each year from a General Fund loan repayment. Senate Bill 1 dedicates this funding specifically to SHOPP. SHOPP = State Highway Operations and Protection Program. |

||||

The specifics of the Governor’s proposed increase for each program include:

- Highway Maintenance Program ($154 Million Increase). The Governor proposes an additional $100 million for major maintenance contracts (specifically for bridges and culverts) and $53.6 million to support 400 new positions at Caltrans. Of the new positions, 300 are to perform routine maintenance, while the remaining 100 are to oversee construction contracts for major maintenance. For routine maintenance, the Governor’s request for positions is based on the number of staff needed to perform specific activities—such as filling potholes; sealing pavement cracks; and replacing and repairing highway guardrails, lighting, and signs—to increase ten levels of service to meet specified targets. For major maintenance, the proposal assumes one position is required for each roughly $1 million in contracts, based on historical averages.

- SHOPP ($570 Million Increase). The proposed SHOPP increase is all for highway rehabilitation projects (including $300 million specifically for bridges and culverts). The Governor does not propose to adjust SHOPP staffing levels (such as for architects and engineers) at this time but will do so as part of his May Revision.

Figure 9 summarizes the Governor’s proposals for the Highway Maintenance Program and SHOPP, compared to the levels of funding provided to each program from SB 1 in 2017‑18 .

Figure 9

Governor’s Proposals for Highway Maintenance Program and SHOPPa

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Program |

Estimated 2017‑18 |

Proposed 2018‑19 |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Highway Maintenance Program |

||||

|

Major maintenance contracts |

$400 |

$500 |

$100 |

25% |

|

Staffing and support |

21 |

76 |

55 |

260% |

|

Subtotals |

($421) |

($576) |

($154) |

(37%) |

|

SHOPP |

||||

|

Projects |

$368 |

$938 |

$570 |

155% |

|

Staffing and supportb |

56 |

56 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($424) |

($994) |

($570) |

(134%) |

|

Totals |

$845 |

$1,570 |

$725 |

86% |

|

aFrom the Road Maintenance and Repair Account. Also includes $75 million in loan repayments each year from the General Fund to SHOPP. bThe Governor will submit his proposal to adjust SHOPP staffing levels as part of the May Revision. SHOPP = State Highway Operations and Protection Program. |

||||

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Prioritizing Funding Between Highway Maintenance Program and SHOPP. Under the Governor’s proposal, we estimate Caltrans would still have near‑term annual funding shortfalls of about $1.6 billion for major maintenance and at least $600 million for SHOPP, largely due to the significant backlog of projects. Though both programs remain underfunded, the Legislature may want to consider modifying the Governor’s proposal to allocate more funding toward major maintenance and less funding toward SHOPP, because major maintenance projects are critical for achieving long‑term savings on the state highway system. Additionally, we note that the Governor’s proposal funds some routine maintenance activities on highway assets—such as guardrails, lighting, and signs—that are not specifically addressed in SB 1. Given SB 1 focused specifically on pavement, bridges, culverts, and transportation management systems, the Legislature could consider whether directing funding toward these other asset classes at this time is consistent with its immediate priorities for repairing California’s highways.

Compensation Cost Adjustment

Background

The Governor’s budget annually includes adjustments for each state department to account for changes in compensation costs arising from collective bargaining agreements and changes in employer retirement rates. These adjustments are calculated based on the number of permanent positions authorized for each department in the state budget. The budget does not provide similar compensation adjustments for temporary positions. In 2017‑18, Caltrans has about 500 temporary positions.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a $58 million increase from the State Highway Account (SHA) to address what Caltrans characterizes as insufficient funding for its positions. The department believes it lacks sufficient funding because it does not receive annual compensation adjustments for its temporary positions. According to Caltrans, the proposed augmentation would fund about 340 positions that it otherwise would have to hold vacant. Caltrans plans to allocate the proposed augmentation across its programs based on their historical compensation expenditures and position history, with most of the increase going to the Highway Maintenance Program ($20.5 million) and administration ($16.1 million). In its proposal, Caltrans indicates that providing the requested funding would alleviate the need for new position requests for most of its programs over the next few years.

Assessment

The Legislature generally expects state departments to fill all their positions in order to perform their expected workload. Though the Governor’s proposal aims to address this goal, we find that it raises some concerns. Specifically, the proposal:

- Lacks Complete Information. The Governor’s proposal identifies the lack of compensation adjustments for temporary positions as a key justification for the proposed augmentation. Yet, the proposal does not document the effects of this budgetary practice over time to justify its need for additional funding, nor does it propose any changes to current budgetary practices to prevent the need for another augmentation in the future. Moreover, the proposal does not describe what workload would be performed if the department were able to fill its vacancies.

- Appears to Duplicate Other Proposals for Staffing Increases. As discussed elsewhere in this chapter, the Governor has several proposals to increase Caltrans staffing to perform new workload. For instance, the Governor proposes to add 400 positions for maintenance and 4 positions for IT security. As noted above, however, the Governor’s proposal states that providing the $58 million to fully fund its positions should alleviate the need for new staffing requests in the near term by allowing Caltrans to fill its vacant positions.

- Treats Caltrans Differently Than Other State Departments. Like Caltrans, other state departments do not receive compensation adjustments for temporary positions. And many other state departments also have ongoing vacant positions. Yet, the Governor does not propose to adjust funding levels or otherwise address position vacancies at these other departments.

Recommendation

Given the above concerns, we recommend the Legislature require Caltrans to provide (1) information showing in detail how the identified funding shortfall developed over time, (2) options to prevent another shortfall from reoccurring in the future, and (3) an explanation for what workload would be performed with the funding. Until this information is provided, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal.

Liability Cost Increases

Background

Caltrans Can Be Liable for Conditions on the State Highway System. Caltrans can be held financially liable for personal and property damages where the cause is due to the design or condition of the state highway system. The department’s base budget to pay for these damages—known as torts—is $68.6 million. Tort costs have increased sharply in recent years, growing from $45 million in 2014‑15 to $93.6 million in 2016‑17, mainly due to some exceptionally high judgments against the state. To cover the cost increases above its base funding level, the department has redirected funding from other program areas in recent years. For instance, Caltrans covered the cost increase for 2016‑17 by redirecting funding from the Highway Maintenance Program as well as other programs.

Caltrans Also Can Be Liable for Collisions Caused by Its Employees While Driving. To insure itself against damages to other individuals and their property caused by Caltrans drivers, the department participates in the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program, which is administered by the Department of General Services (DGS). Caltrans pays DGS a premium each year in order to be insured under the program. This premium is primarily based on the average annual cost of the previous five years of Caltrans’ collision claims. Caltrans’ premium more than tripled from 2014‑15 to 2017‑18, growing from $4.2 million to $14.6 million, due to a handful of exceptionally costly claims. The department’s ongoing base budget to pay for claims is $4.2 million, though it received a one‑time augmentation of $5.1 million in 2017‑18. The department indicates it has been paying for the cost increases in recent years by redirecting funding from other activities, such as replacing vehicles.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget proposes two increases totaling $11.9 million from the SHA to account for rising liability‑related costs:

- Tort Payments ($7 Million). The Governor proposes an ongoing $7 million increase for tort payments. Additionally, the Governor proposes budget bill language allowing the Department of Finance (DOF) to increase funding by up to an additional $20 million, following notification to the Legislature. The administration believes this flexibility is necessary due to fluctuations in tort costs.

- Vehicle Insurance Costs ($4.9 Million). The Governor proposes $4.9 million on a two‑year limited‑term basis to pay for a portion of the recent increases in Caltrans’ vehicle insurance premium. (We note that this proposal does not appear intended to address any potential cost increases for 2018‑19, as DGS will not set its premium rates for the budget year until this spring.)

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Caltrans must pay for its tort costs and vehicle insurance premium—meaning these operational costs are not discretionary. In our view, however, the Governor’s proposals raise two issues for legislative consideration regarding (1) ways to reduce these costs, and (2) Caltrans’ redirection of funding to pay for the costs up until now.

Options to Reduce Costs. The recent cost increases for Caltrans’ tort payments and vehicle insurance premium both appear to be due to a few exceptionally large legal settlements and judgments. For example, in early 2017, Caltrans incurred two tort judgments totaling $86 million, whereas the largest judgment two years earlier was $9.5 million. Along the same lines, we found in our recent report, A Review of Caltrans’ Vehicle Insurance Costs, that three multimillion dollar vehicle insurance claims accounted for virtually all of the recent increase in Caltrans’ vehicle insurance premiums. As we discuss in that report, the Legislature could consider establishing a state liability limit as one way to reduce costs, as many other states have done. Additionally, Caltrans could explore ways to reduce vehicle collisions and improve highway conditions to reduce its legal exposure.

Funding Redirections. Each of the Governor’s two proposals address cost increases that began several years ago. Because the costs are not discretionary, the department has been paying for them by redirecting funding from other activities. For instance, Caltrans has been paying for its increased vehicle insurance premium by redirecting funding originally budgeted for replacing vehicles (such as snow plows and pick‑up trucks). Thus, if the Legislature were to approve the Governor’s proposals, the additional funding would allow the department to send the redirected funds back to their original purpose—for example, from paying for the vehicle insurance premium back to paying for vehicle replacements. Prior to taking action on the Governor’s proposals, we recommend the Legislature ask Caltrans to explain at budget hearings how these funding redirections have impacted the departments operations and why funding is no longer available to redirect.

Information Technology

Background

Caltrans’ IT program provides services that support various activities department‑wide. For example, the program manages the department’s IT projects, and is responsible for maintaining its IT infrastructure. In 2017‑18, the program has a budget totaling about $115 million (equal to about 1 percent of the department’s overall budget) and about 550 positions.

Recent Budget Increases for IT Program. In 2017‑18, Caltrans requested, and the Legislature approved, two augmentations from the SHA for its IT program:

- IT Devices ($12 Million). The budget provided a $12 million one‑time increase for Caltrans to replace 1,100 of its IT devices, such as network switches. In its proposal, Caltrans noted that about 6,000 of its 11,000 IT devices were at the end of their useful life, and it would use the funding to replace devices at the greatest risk of failure.

- IT Security ($4 Million). The budget provided a $4 million increase ($1.8 million ongoing and $2.2 million limited term), as well as six permanent positions, to improve the department’s cybersecurity and prevent the reoccurrence of recent cyberattacks on the department.

Legislature Expressed Concerns Over Lack of Detailed Plans. Though it approved the above funding requests, the Legislature during budget hearings asked if Caltrans had developed detailed plans for both the replacement of its IT devices as well as improvements to its IT security. In particular, the Legislature asked whether Caltrans had a multiyear plan to replace equipment, as well as whether it had looked at paying for IT storage space “in the cloud” rather than replacing storage devices. Caltrans indicated that it was in the process of developing long‑term plans to consider these and other issues.

Caltrans Recently Released Two of Three IT Plans. In the spring of 2017, Caltrans released an “IT Infrastructure Roadmap.” This roadmap outlines short‑ and long‑term goals for Caltrans’ IT program (such as creating operational efficiencies). It also sets forth 46 specific initiatives to help the department meet its goals (such as by reducing printing costs). Subsequently, in fall 2017, Caltrans released a “Cybersecurity Roadmap” that identifies activities to elevate the strength of its cybersecurity from “weak” to “optimized.” This roadmap calls for three separate waves of activities, with the first wave of activities being implemented with the funding provided in the current year. In 2017, Caltrans also initiated planning for an “IT Architecture Roadmap” that would address its business applications and data processing needs, as well as options for hosting its data and replacing equipment. Caltrans determined, however, that it did not have the in‑house expertise to complete this roadmap.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget contains two augmentations from the SHA that are related to the 2017‑18 budget augmentations:

- IT Devices ($2 Million, Plus the Potential for Another $12 Million). The Governor proposes $2 million (one time) for Caltrans to contract with a vendor to develop the IT Architecture Roadmap for managing and replacing its IT devices. Additionally, the Governor proposes provisional budget bill language authorizing up to $12 million (one time) to begin implementing the roadmap after its completion, contingent upon DOF, the California Department of Technology (CDT), and CalSTA determining the roadmap is “viable.”

- IT Security and Privacy Office ($10.4 Million). The Governor proposes a $10.4 million increase, along with four positions, to implement the second wave activities identified in Caltrans’ cybersecurity plan (such as addressing mobile security needs). Of the proposed increase, $2.1 million is ongoing ($1.6 million for software and hardware purchases and $488,000 for the four positions), while the remainder is one time (primarily for hardware and software purchases).

Recommendations

Recommend Approving Funding for Roadmap, Rejecting Budget Bill Language. The development of a roadmap for Caltrans to manage and replace its IT devices would help ensure that the department is taking a cost‑effective approach. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature approve the proposed $2 million to develop the roadmap. However, the Governor’s proposed budget bill language puts the Legislature in the position of approving funding to start implementing the roadmap without providing the Legislature with an opportunity to first review it. In our view, this approach significantly diminishes legislative oversight over the costs of Caltrans’ IT program. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature reject the language authorizing the administration to increase spending after the enactment of the state budget to implement the roadmap. Instead, we recommend adopting budget bill language requiring Caltrans to submit a copy of the roadmap to the Legislature upon its completion. Under this approach, Caltrans could submit a budget request in 2019‑20 to implement the roadmap, after the Legislature has an opportunity to review it. (Though Caltrans would not be able to replace additional devices in 2018‑19, we note that the 2017‑18 budget already provided funding for Caltrans to replace devices at the greatest risk of failure.)

Recommend Approving Funding for IT Security and Privacy. We recommend the Legislature approve Caltrans’ separate request for funding for IT security and privacy, given the department already has completed its cybersecurity roadmap that outlines how it intends to improve its cybersecurity through specific courses of action.

Road Usage Charge

Background

Legislature Created Pilot Program to Study Road Usage Charge. In 2014, the Legislature enacted Chapter 835 (SB 1077, DeSaulnier), to study the feasibility of a “road usage charge”—an amount charged to individuals for each mile they drive—as an alternative to raising revenue for roads through fuel taxes. Specifically, the legislation required CalSTA to conduct a pilot program to analyze various methods for collecting road usage data and report by June 2018 on the feasibility of implementing a road charge on a statewide basis. CalSTA, in turn, selected Caltrans to implement the pilot program. The 2015‑16 budget provided $10.7 million for Caltrans to conduct the pilot program, including $8.8 million for consultant contracts, $618,000 for five limited‑term positions (for three years), and $1.3 million for overtime and other costs.

Pilot Program Concluded Early, Assessed Several Revenue Collection Methods. The pilot program enrolled 5,000 vehicles from volunteer participants to test several options for collecting the revenues, including: (1) prepurchased time and mileage permits, (2) manual odometer readings, (3) vehicle plug‑in devices, (4) smart phone applications, and (5) a specific built‑in technology found in newer vehicles. The pilot program concluded early in March and CalSTA issued its report in December 2017. In its report, CalSTA concluded that a road usage charge is viable but that certain obstacles remain to be addressed for each of the methods tested. For example, CalSTA noted that the two permit options could be difficult to enforce and costly to administer, while the vehicle plug‑in devices tested could be obsolete by the time a road usage charge is implemented.

Caltrans Recently Started to Plan for a New “Pay‑at‑the‑Pump” Pilot Program. The SB 1077 pilot program did not test collecting road usage charges when drivers pay for fuel purchases at the pump. This is because Caltrans determined that cost‑effective technology did not exist to transmit mileage data from vehicles to fuel pumps to include in the price of fuel purchases. However, in adopting the 2017‑18 budget, the Legislature approved a request from Caltrans to reappropriate $737,000 in unspent funding from the pilot program to match a new $750,000 federal grant to, in part, initiate planning for a new pay‑at‑the‑pump pilot program. According to Caltrans, new technologies emerged after the initiation of the SB 1077 pilot that now make a pay‑at‑the pump option feasible to study. Moreover, Caltrans believes the pay‑at‑the‑pump option has a key advantage over the options tested in the SB 1077 pilot because drivers already are familiar with paying gas taxes when filling up at the pump. In approving Caltrans’ request, the Legislature also added budget bill language requiring the department to report on its progress in studying a pay‑at‑the‑pump pilot program by July 1, 2018. In early January 2018, Caltrans issued a request for information to gauge market conditions for implementing a pay‑at‑the‑pump pilot program, with responses due on February 15, 2018.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes $3.2 Million to Implement the Pay‑at‑the‑Pump Pilot Program. This proposal would allow Caltrans to proceed to solicit vendors to actually implement the new pilot program. The proposed amount includes (1) $2.5 million for one‑time expenses (such as consultant contracts) and (2) $674,000 to continue, for two years, the five limited‑term positions provided in the 2015‑16 budget for the SB 1077 pilot program. Caltrans recently was awarded a $1.8 million federal grant that would pay for most of the one‑time expenses. The remainder of the funding would come from the SHA. Additionally, the proposed budget contains the same reporting language as the 2017‑18 budget—specifically, a requirement for Caltrans to report on its progress by July 1, 2018.

Assessment

Pay‑at‑the‑Pump Revenue Collection Method Might Have Advantages but Also Potential Drawbacks. Caltrans makes a reasonable case that a pay‑at‑the‑pump revenue collection method might have an advantage over other methods because drivers already pay fuel taxes at the pump, potentially making the transition to a new road usage more seamless for them. However, a pay‑at‑the‑pump collection method likely will not prove to be workable for collecting revenue from drivers of certain alternative fuel vehicles, such as plug‑in electric vehicles. This is because these vehicle owners can charge their vehicles at home rather than using public fueling stations. As a result, these drivers could evade the pay‑at‑the‑pump road usage charge. Though electric vehicles currently make up less than one percent of registered vehicles in California, both the state and automakers have undertaken efforts in recent years to increase electric vehicle adoption. Thus, a pay‑at‑the‑pump collection method could face serious issues in the long term as electric vehicle adoption increases. Indeed, in its December 2017 report on the SB 1077 pilot program, CalSTA noted that a pay‑at‑the‑pump collection method would only address gas‑powered vehicles and that alternative technologies would be needed to collect from alternative fuel vehicles.

Feasibility of Pay‑at‑the‑Pump Pilot Program Not Known at This Time. As noted above, Caltrans only recently issued a request for information to see if vendors are available who can offer a feasible technological solution for collecting road usage charge revenues at the pump, with responses not due until February 15. Therefore, at the time of this analysis, the feasibility of a new pay‑at‑the pump pilot program remains uncertain. Additionally, the costs are also still subject to some uncertainty, as Caltrans’ request for information asks respondents to submit a specific cost estimate for implementing the pilot program. Caltrans also has not yet submitted the statutorily required report on its progress in studying the feasibility of a pay‑at‑the‑pump pilot program, due July 1, 2018.

Recommendation

Given the feasibility and costs of a pay‑at‑the‑pump pilot program are somewhat uncertain at this time, we recommend the Legislature ask Caltrans to provide information summarizing the results of its request for information at spring budget hearings. Once the Legislature has this information, it would be better positioned to evaluate whether to fund the new pilot program.

California Highway Patrol

The primary mission of the CHP is to ensure safety and enforce traffic laws on state highways and county roads in unincorporated areas. The CHP also promotes traffic safety by inspecting commercial vehicles, as well as inspecting and certifying school buses, ambulances, and other specialized vehicles. The CHP carries out a variety of other mandated tasks related to law enforcement, including investigating vehicular theft and providing backup to local law enforcement in criminal matters. The operations of the CHP are divided across eight geographic divisions throughout the state.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $2.6 billion in 2018‑19, which is about $177 million, or 7 percent, more than the revised current‑year estimate. The year‑over‑year increase is mainly the result of the Governor’s proposal to revert $141 million in funding for four capital outlay projects and shift to lease revenue bonds to finance these same projects. The level of spending proposed for CHP for 2018‑19 supports about 10,850 positions, of which about 7,600 are uniformed officers.

Area Office Replacement

Plan to Replace CHP Offices Initiated in 2013‑14

The CHP operates 103 area offices across the state, which usually include a main office building for CHP staff, CHP vehicle parking and service areas, and a dispatch center. Beginning in 2013‑14, the administration initiated a plan to replace a few CHP field offices each year for the next several years. The Legislature has approved funding from the MVA in accordance with this plan each year since 2013‑14 as follows:

- 2013‑14. $1.5 million for advanced planning and site selection to replace up to five unspecified CHP area offices.

- 2014‑15. $32.4 million to fund the acquisition and preliminary plans for five new CHP area offices in Crescent City, Quincy, San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Truckee, and $1.7 million for advanced planning and site selection to replace up to five additional unspecified CHP area offices.

- 2015‑16. $136 million to fund the design and construction of the area offices in Crescent City, Quincy, San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Truckee, as well as $1 million for advanced planning and site selection to replace five additional unspecified area offices.

- 2016‑17. $32 million for the acquisition and preliminary plans for the area offices in El Centro, Hayward, San Bernardino and Ventura and $800,000 for advanced planning and site selection.

- 2017‑18. $139 million to fund the design construction of the area offices in El Centro, Hayward, San Bernardino, and Ventura; $2.5 million to fund the acquisition and performance criteria phases in Humboldt; and $2.1 million to fund the acquisition and performance criteria phases in Quincy, and $500,000 for advanced planning and site selection.

Governor’s Proposal

Shift to Lease Revenue Bond Financing for CHP Area Office Replacements. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift from a pay‑as‑you‑go approach for the design‑build phase of four CHP area office replacement projects in El Centro, Hayward, Ventura, and San Bernardino to financing the projects with lease revenue bonds that would be supported from the MVA. According to the administration, this approach would allow the projects to continue and ensure the MVA can maintain an adequate reserve. Under the Governor’s proposal, $138.7 million—El Centro ($30.3 million), Hayward ($38.1 million), San Bernardino ($33.2 million), and Ventura ($37.1 million)—in previously authorized funds would revert to MVA, and $141.1 million in lease revenue bond authority would be authorized. (The $2.3 million difference between lease revenue bond authority and the reversion amount is due to cost increases for the design‑build phase for the Ventura office [$1.3 million], and the San Bernardino office [$1 million].) The Governor’s budget also proposes lease revenue bond authority to build a new office in Quincy. (The funding approved in the 2015‑16 budget to build a new office in Quincy subsequently reverted due to difficulties acquiring a site.)

Specifically, the Governor’s budget requests $173.8 million in lease revenue bond authority as follows:

- El Centro. $30.4 million to fund the design‑build phase of the El Centro area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 27,481 square feet, or about five‑to‑six times the size of the existing 4,575 square foot facility that was built in 1966. The total estimated cost to replace this office is estimated at $34.7 million (includes $4.3 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

- Hayward. $38.1 million for the design‑build phase of the Hayward area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 43,518 square feet, or about four times the size of the existing 11,033 square foot facility that was built in 1971. The total estimated cost to replace this office is estimated at $53.1 million (includes $15 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

- Ventura. $38.4 million to fund the design‑build phase of the Ventura area office replacement. The proposed facility would be 40,972 square feet, or about three‑to‑four times the size of the existing 12,469 square foot facility that was built in 1976. The total estimated cost to replace this office is estimated at $45.7 million (includes $7.3 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

- San Bernardino. $34.2 million to fund the design‑build phase of the San Bernardino office replacement. The proposed facility would be 44,000 square feet, or about three‑to‑four times the size of the existing 12,253 square foot facility that was built in 1973. The total estimated cost to replace this office is estimated at $39.5 million (includes $5.4 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2016‑17 budget).

- Quincy. $32.7 million to fund the design‑build phase of the Quincy replacement facility. The proposed facility would be 24,538 square feet, or roughly six times the size of the existing 4,006 office that opened in about 1967. The total estimated cost to replace this office is estimated at $34.9 million (includes $2.1 million for acquisition and planning provided in the 2017‑18 budget).

Shift Procurement Method for Santa Barbara Office. The budget plan proposes to shift the procurement methodology for the Santa Barbara area office replacement from pay‑as‑you‑go capital outlay to build‑to‑suit leasing. Specifically, the administration requests a reversion of the unexpended authority of $32.4 million appropriated for the project in 2014‑15 and 2015‑16, and the addition of budget trailer language to authorize a lease‑purchase agreement or a lease with an option to purchase. The administration sites its inability to acquire suitable land in the Santa Barbara area as its reason for the proposed shift from capital outlay to build‑to‑suit lease. The proposed facility would be 25,232 square feet, or almost four times the size of the existing 7,008 square foot facility that opened in about 1982.

Five‑Year Plan for Replacement of CHP Offices. The administration’s recent 2018 Five‑Year Infrastructure Plan—which proposes state spending on infrastructure projects in all areas of state government through 2022‑23—includes ongoing projections of the CHP’s area office replacement needs. As Figure 10 shows, the plan proposes a total of $326 million over the next five years. This amount includes (1) $174 million for the design‑build phase of five area office replacement projects in 2018‑19 (as discussed above); (2) $137.4 million for the design‑build phase of two area office replacements in Humboldt and Santa Fe Springs, and other phases of five identified replacement projects; and (3) $14.6 million for yet‑to‑be‑identified replacement projects.

Figure 10

California Highway Patrol Five‑Year Office Replacement Plan

(In Thousands)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Total Project Cost |

|

|

Statewide—area office replacement program |

— |

— |

— |

— |

$14,586A,D |

$14,586 |

|

Statewide—site identification and planning |

— |

$700A,S |

$700A,S |

$700A,S |

700A,S |

2,800 |

|

El Centro—area office replacement |

$30,413B |

— |

— |

— |

— |

30,413 |

|

Hayward—area office replacement |

38,103B |

— |

— |

— |

— |

38,103 |

|

Quincy—replacement facility |

32,719B |

— |

— |

— |

— |

32,719 |

|

Ventura—area office replacement |

38,414B |

— |

— |

— |

— |

38,414 |

|

San Bernardino—area office replacement |

34,167B |

— |

— |

— |

— |

34,167 |

|

Humboldt—area office replacement |

— |

34,292B |

— |

— |

— |

34,292 |

|

Tracy—area office replacement |

— |

— |

4,613V |

2,750V |

2,811V |

10,174 |

|

Santa Fe Springs—area office replacement |

— |

— |

2,400A,D |

— |

49,107B |

51,507 |

|

Baldwin Park—area office replacement |

— |

— |

— |

2,653A,D |

— |

2,653 |

|

Santa Barbara—area office replacement |

— |

— |

— |

— |

9,000V |

9,000 |

|

Santa Ana—area office replacement |

— |

— |

— |

9,702V |

7,764V |

17,466 |

|

Westminster—area office replacement |

— |

— |

— |

— |

9,263V |

9,263 |

|

Totals |

$173,816 |

$34,992 |

$7,713 |

$15,805 |

$93,231 |

$325,557 |

|