LAO Contact

- CalWORKs

- IHSS and SSI/SSP

- Medi-Cal and Continuum of Care Reform

- Medi-Cal

- Information Technology

- Developmental Services

- Department of State Hospitals

- Medi-Cal

February 16, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Analysis of the

Health and Human Services Budget

- Overview

- Medi‑Cal

- Department of State Hospitals

- CalWORKs

- In‑Home Supportive Services

- SSI/SSP

- Developmental Services

- Continuum of Care Reform

Executive Summary

Overview of the Health and Human Services Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes $23.8 billion from the General Fund for health programs—a 7.1 percent net increase above the revised estimated 2017‑18 spending total—and $13.5 billion from the General Fund for human services programs—a net increase of 2.9 percent above the revised estimated 2017‑18 spending total. For the most part, the year‑over‑year budget changes reflect caseload changes, technical budget adjustments, and the implementation of previously enacted policy changes, as opposed to new policy proposals. Significantly, the budget reflects a net increase of $1.5 billion from the General Fund for Medi‑Cal local assistance, in part reflecting (1) a lower proportion of Proposition 56 (2016) tobacco tax revenues offsetting General Fund cost growth and (2) a higher state cost share for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act optional expansion population.

Medi‑Cal: Caseload Essentially Flat, No Proposition 55 Funding Assumed. The Governor’s budget projects an average monthly Medi‑Cal caseload of 13.5 million in 2018‑19—virtually flat from estimated 2017‑18 caseload. We find these caseload estimates to be reasonable. For the first time, the Director of Finance has made a calculation under a budget formula in Proposition 55 (2016) that determines whether a share of Proposition 55 tax revenues is to be directed to increase funding in Medi‑Cal in a given fiscal year. The Governor’s budget provides no additional funding for Medi‑Cal pursuant to this formula. We are currently reviewing the administration’s approach to this formula and will provide our comments to the Legislature at a later time.

Recent Federal Reauthorization of Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Funding Will Result in General Fund Savings Not Assumed in the January Budget. CHIP is a joint federal‑state program that provides health insurance coverage to about 1.3 million children in low‑income families, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. Due to congressional appropriations made after the administration finalized its proposed 2018‑19 budget, the proposed state budget makes federal funding assumptions that differ from the recent federal action. As the recent federal action continues federal funding for CHIP at a higher federal cost share than assumed in the budget, the Governor’s May Revision budget proposal will reflect a downward adjustment of General Fund costs for CHIP totaling $900 million over 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

Governor’s Proposition 56 Budget Proposal for Medi‑Cal Essentially Aligns With the 2017‑18 Budget Agreement; Legislature Afforded Opportunity to Target Funding Available for Additional Provider Payment Increases. Proposition 56 raised state taxes on tobacco products and dedicates the majority of associated revenues to Medi‑Cal on an ongoing basis. We find that the Governor’s budget proposal essentially aligns with a two‑year 2017‑18 budget agreement between the Legislature and the administration on the use of Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal. Of the total amount of 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 Proposition 56 revenues, the Governor allocates a total of about $1.4 billion to provider payment increases, with the remaining balance of $880 million to be used to offset General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal cost growth. Under the Governor’s proposal, we estimate that $523 million in total Proposition 56 funding is available for additional provider payment increases beyond those structured in the 2017‑18 agreement. The Legislature will be able to determine how these new payments are structured.

Governor’s Incompetent‑to‑Stand Trial (IST) Proposals Raise Several Issues for Legislative Consideration. The Governor’s budget includes various proposals to increase IST capacity as a way to reduce the number of individuals waiting to be transferred to a treatment program. We recommend the Legislature define what it considers an appropriate IST waitlist, which would allow it to then determine how many additional beds are needed to reduce this waitlist. The budget also includes $100 million (one time) for the Department of State Hospitals to contract with counties to establish IST diversion programs that are intended to primarily treat offenders before they are declared IST. While the concept of IST diversion programs has merit, we find that the Governor’s proposal is not well structured to achieve its intended benefits. As such, we recommend the Legislature instead direct the department work with individual counties to develop proposals for specific county IST diversion programs that would include such information as the specific services that would be provided.

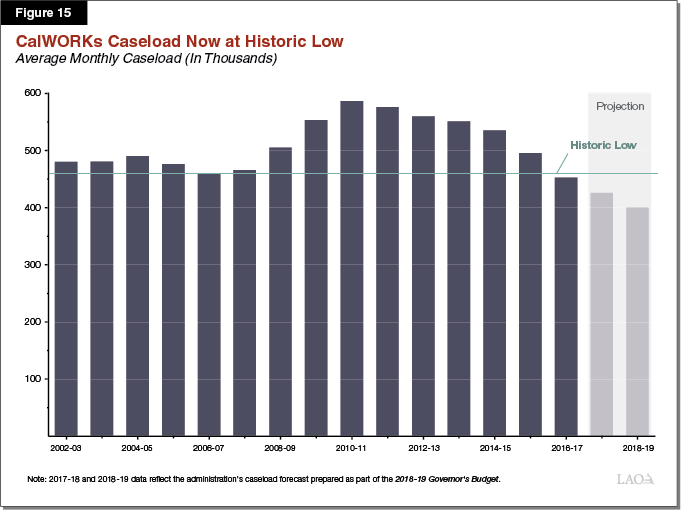

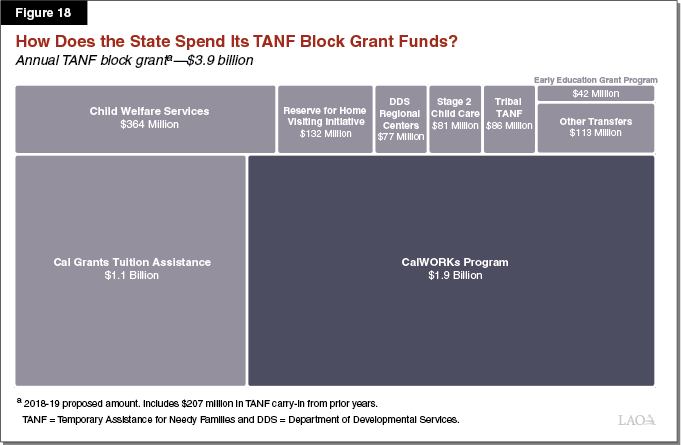

CalWORKs Caseload at Historical Low, Freeing Up Federal Funds for Other Uses. The Governor’s budget estimates the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) caseload will be 400,000 in 2018‑19—the fewest participants in the program’s 20‑year history. As a result of the caseload decline, federal funds that were previously used to fund the CalWORKs program are freed up for other purposes. The Governor proposes to spend the freed‑up funds to (1) offset General Fund costs outside of CalWORKs, (2) fund a new home visiting program in CalWORKs, and (3) fund a one‑time early education grant program in the California Department of Education. We evaluate the Governor’s proposal for CalWORKs, highlight issues and questions for legislative consideration, and note that the freed‑up funds provide the Legislature with an opportunity to create its own plan for spending the funds.

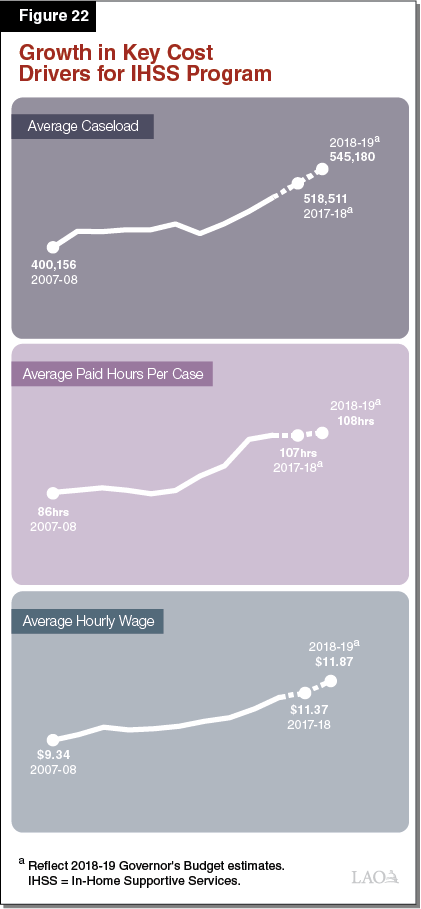

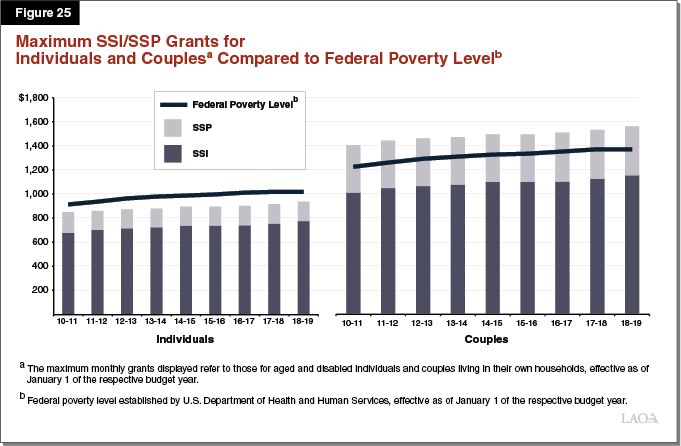

Governor’s Proposals for IHSS and SSI/SSP Program Appear Reasonable. We have reviewed the administration’s 2018‑19 budget proposals for the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) and the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP). While we raise a few issues for legislative consideration—mainly related to the new methodology for calculating administrative costs in IHSS—overall we find the administration’s proposals to be reasonable at this time. We will continue to monitor IHSS and SSI/SSP programs and update the Legislature if we think any updates to the caseload and budgeted funding levels should be made.

Department of Developmental Services (DDS) Budget Reflects Continued Activity Leading to Closure of Developmental Centers (DCs). In 2015, the administration announced its plan to close the state’s remaining DCs by the end of 2021. The transition of the remaining DC residents to the community appears on track for 2018‑19. Noting that the Legislature has been considering a proposal to earmark any possible savings from the closures of DCs for the DDS community services program, we discuss the benefit of the Legislature directing DDS to conduct a comprehensive assessment of service gaps and related unmet funding requirements in the community services system overall.

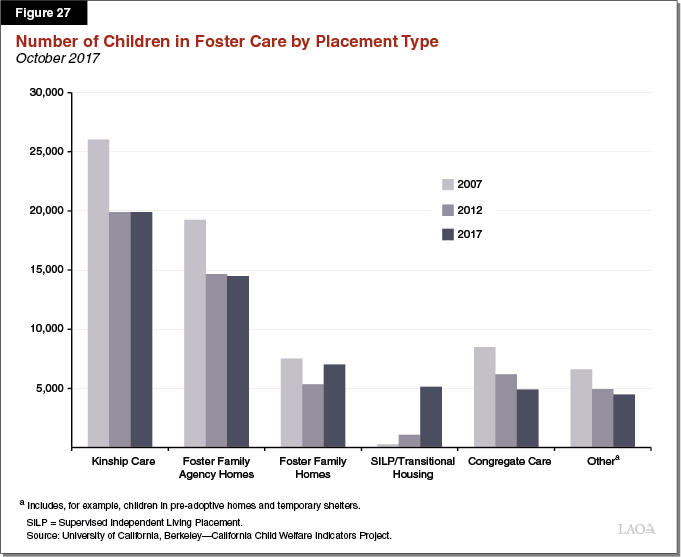

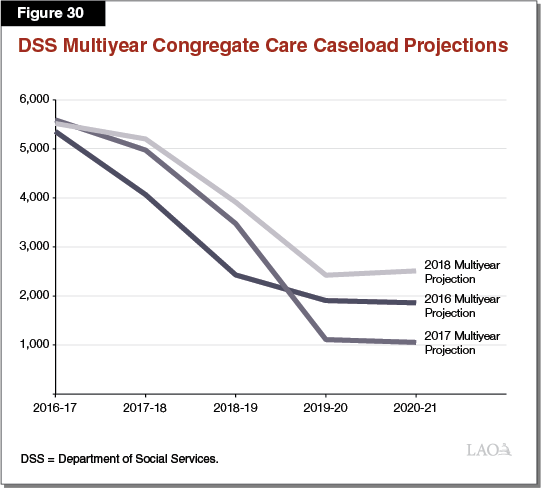

Governor Continues to Implement Continuum of Care Reform (CCR), Some Challenges Emerge. The Governor’s budget proposes funding in 2018‑19 to continue to implement CCR in the state’s foster care system. At a high level, CCR aims to reduce reliance on long‑term group home placements and increase the utilization and capacity of home‑based family placements for children in the foster care system. While the Governor’s proposal reflects more realistic estimates of the costs and savings associated with CCR than assumed in recent Governor’s budgets, it does not propose any major changes in CCR policy. We provide background on CCR, highlight a few implementation challenges that have emerged, describe the Governor’s funding proposal, and raise issues and questions for legislative consideration with the goal of addressing these implementation challenges.

Overview

Health

Background on Major Health Programs

California’s major health programs provide a variety of health benefits to its residents. These benefits include purchasing health care services (such as primary care) for qualified low‑income individuals, families, and seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs). The state also administers programs to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, prepare for and respond to public health emergencies, regulate health facilities, and achieve other health‑related goals.

The health services programs are administered at the state level by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Department of Public Health, Department of State Hospitals (DSH), the California Health Benefits Exchange (known as Covered California or the Exchange), and other California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHSA) departments. The actual delivery of many of the health care services provided through state programs often takes place at the local level and is carried out by local government entities, such as counties, and private entities, such as commercial managed care plans. (Funding for these types of services delivered at the local level is known as “local assistance,” whereas funding for state employees to administer health programs at the state level and/or provide services is known as “state operations.”)

Expenditure Proposal by Major Programs

Overview of General Fund Health Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $23.8 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $1.6 billion—or 7.1 percent—above the revised estimated 2017‑18 spending level, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)a

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Medi‑Cal—Local Assistance |

$20,058 |

$21,589 |

$1,531 |

7.6% |

|

Department of State Hospitals |

1,544 |

1,773 |

229 |

14.8 |

|

Department of Public Health |

148 |

143 |

‑5 |

‑3.4 |

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programsb |

235 |

54 |

‑181 |

‑76.9 |

|

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development |

33 |

33 |

— |

— |

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority |

9 |

9 |

— |

— |

|

All other health programs (including state support)c |

226 |

224 |

‑2 |

‑0.8 |

|

Totals |

$22,254 |

$23,826 |

$1,572 |

7.1% |

|

aExcludes general obligation bond costs. bLocal assistance only. Reduction in 2018‑19 reflects a $222 million reimbursement from Proposition 98 funds related to certain Medi‑Cal administrative activities performed by schools. cIncludes Health and Human Services Agency. |

||||

Summary of Major General Fund Budget Assumptions and Changes. The year‑over‑year increase of $1.6 billion General Fund over the revised estimated 2017‑18 spending level is largely comprised of a net increase in expenditures in Medi‑Cal local assistance. (We note that the roughly 15 percent increase in General Fund expenditures in DSH reflects in part the proposed implementation of various strategies intended to reduce the number of incompetent‑to‑stand‑trial patients awaiting placement.) The net increase in Medi‑Cal local assistance of $1.5 billion General Fund is due to several factors, including:

- Higher projected General Fund spending due to a higher proportion of Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenues in 2018‑19 being budgeted to pay for supplemental provider payments as opposed to offsetting General Fund cost growth.

- Increased costs related to the state’s responsibility for a higher share of costs for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) optional expansion population.

- Higher projected spending related to general growth in health care costs.

We note that the January Governor’s budget, which was finalized before subsequent congressional action to reauthorize funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) administered through Medi‑Cal, included $300 million of higher year‑over‑year General Fund costs in 2018‑19 for CHIP. These higher costs reflected a full‑year cost to backfill an assumed reduction in federal funds, continuing from 2017‑18, for CHIP. Recent federal action to reauthorize federal funding for CHIP initially at an enhanced rate will instead reduce General Fund costs by a total of $900 million over 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 relative to what the January budget assumed. With the adjustment to the Medi‑Cal General Fund budget, the year‑over‑year net increase in Medi‑Cal local assistance would be roughly $1.2 billion, or 6.2 percent.

Finally, we note that the Governor’s budget does not provide any additional funding for Medi‑Cal in 2018‑19 pursuant to a budget formula in Proposition 55 (2016) that extended tax rate increases on high‑income Californians.

Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal Proposal. Proposition 56 (2016) raised state taxes on tobacco products and dedicates the majority of associated revenues to Medi‑Cal on an ongoing basis. The 2017‑18 budget included a two‑year budget agreement between the Legislature and the administration on the use of Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal. We find that the Governor’s updated Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal proposal—discussed in detail in the “Medi‑Cal” section of this report—essentially aligns with the 2017‑18 budget agreement. Specifically, of the total amount of 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 Proposition 56 revenues, the Governor allocates a total of about $1.4 billion to provider payment increases, with the remaining balance of $880 million to be used to offset General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal cost growth. We also note that the Governor’s budget proposal reflects a downward adjustment in the estimated costs to implement the provider payment increases as specifically structured in the 2017‑18 agreement. This in effect frees up Proposition 56 resources that the Legislature can target for use in Medi‑Cal in 2018‑19.

Human Services

Background on Major Human Services Programs

California’s major human services programs provide a variety of benefits to its residents. These include income maintenance for the aged, blind, or disabled; cash assistance and employment services for low‑income families with children; protecting children from abuse and neglect; providing home care workers who assist the aged and disabled in remaining in their own homes; providing services to the developmentally disabled; collection of child support from noncustodial parents; and subsidized child care for low‑income families.

Human services programs are administered at the state level by the Department of Social Services, Department of Developmental Services (DDS), Department of Child Support Services, and other CHHSA departments. The actual delivery of many services takes place at the local level and is typically carried out by 58 separate county welfare departments. A major exception is the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment program, which is administered mainly by the U.S. Social Security Administration. In the case of DDS, community‑based services (the type of services received by the vast majority of DDS consumers) are coordinated through 21 nonprofit organizations known as Regional Centers.

Expenditure Proposal by Major Programs

Overview of the General Fund Human Services Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of $13.5 billion from the General Fund for human services programs in 2018‑19. As shown in Figure 2, this reflects a net increase of $375 million—or 2.9 percent—above estimated General Fund expenditures in 2017‑18. The budget reflects modest year‑over‑year changes in the General Fund budget for some departments and programs, while reflecting more significant changes for others, including California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS), and Child Welfare Services programs. In general, the more significant year‑over‑year changes in General Fund support for these programs are in part due to various funding shifts that have occurred over the last several years. These funding shifts result in General Fund increases and decreases that are not necessarily representative of broader trends in caseload and service costs in these programs.

Figure 2

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

Program |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

SSI/SSP |

$2,861.9 |

$2,827.0 |

‑$34.9 |

‑1.2% |

|

Department of Developmental Services |

4,205.2 |

4,440.9 |

235.7 |

5.6 |

|

CalWORKs |

454.7 |

551.9 |

97.2 |

21.4 |

|

In‑Home Supportive Services |

3,388.0 |

3,641.7 |

253.6 |

7.5 |

|

County Administration and Automation |

772.0 |

766.1 |

‑5.9 |

‑0.8 |

|

Child Welfare Servicesa |

517.4 |

433.1 |

‑84.2 |

‑16.3 |

|

Department of Child Support Services |

315.6 |

315.6 |

0.1 |

— |

|

Department of Rehabilitation |

64.6 |

64.6 |

— |

0.1 |

|

Department of Aging |

34.0 |

34.0 |

— |

— |

|

All other human services (including state support) |

466.2 |

379.9 |

‑86.4 |

‑18.5 |

|

Totals |

$13,079.6 |

$13,454.8 |

$375.2 |

2.9% |

|

aThis includes, among other programs, child protective services, foster care services, and kin guardian and adoption assistance. It generally reflects child welfare services spending that is not realigned to counties. |

||||

A Closer Look at Total Human Services Funding. For those programs that are demonstrating more significant General Fund increases or decreases, taking a closer look at the total funding proposed for their support provides a clearer picture of their overall growth or decline. As shown in Figure 3, after accounting for total funding from all sources, growth or decline in most of these programs is generally relatively modest. We note that growth in IHSS remains relatively high even when looking at total funds—we describe the main factors contributing to this growth in the analysis that follows.

Figure 3

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

Total Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

Program |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

SSI/SSP |

$9,935.7 |

$10,096.7 |

$161.0 |

1.6% |

|

Department of Developmental Services |

6,953.8 |

7,305.0 |

351.2 |

5.1 |

|

CalWORKs |

5,001.9 |

4,818.5 |

‑183.4 |

‑3.7 |

|

In‑Home Supportive Services |

10,294.8 |

11,241.9 |

947.1 |

9.2 |

|

County Administration and Automation |

2,314.9 |

2,285.3 |

‑29.6 |

‑1.3 |

|

Child Welfare Servicesa |

6,287.4 |

6,246.7 |

‑40.7 |

‑0.6 |

|

Department of Child Support Services |

1,010.7 |

1,011.5 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

|

Department of Rehabilitation |

458.5 |

460.1 |

1.6 |

0.3 |

|

Department of Aging |

210.2 |

201.5 |

‑8.8 |

‑4.2 |

|

aThis includes, among other programs, child protective services, foster care services, and kin guardian and adoption assistance. It generally reflects child welfare services spending that is not realigned to counties. |

||||

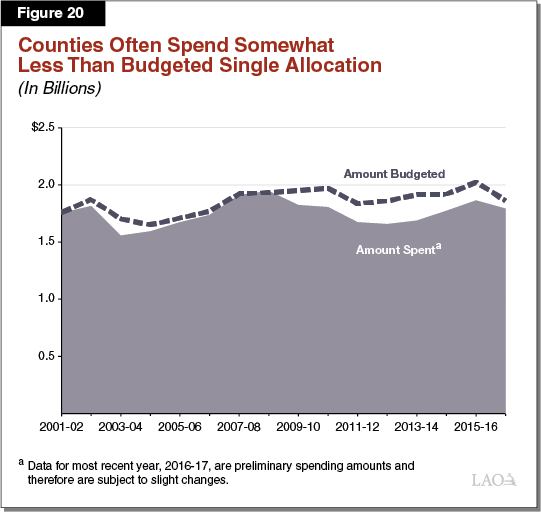

Governor’s Budget Largely Reflective of Current Law and Policy. Our analysis of the Governor’s human services budget proposal indicates that it is largely in line with the implementation of current law and policy. For example, the proposal adjusts for increases and decreases related to changes in program caseloads and the continued implementation of existing policy changes—such as the implementation of minimum wage increases in certain programs.

Although the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget is largely related to the implementation of current law, there are a few exceptions. One example is a proposal to create a new home visiting program in CalWORKs. In the analysis that follows, we provide an overview of the Governor’s proposals for the major human services programs, provide insight into the underlying program trends that lead to the proposed budget levels, and raise issues for legislative consideration.

Medi‑Cal

Background

In California, the federal‑state Medicaid program is administered by DHCS as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi‑Cal). Medi‑Cal is by far the largest state‑administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal‑state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low‑income persons. Before 2014, Medi‑Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low‑income families with children, SPDs, and pregnant women. As part of the ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi‑Cal eligibility to include additional low‑income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program. This eligibility expansion is sometimes referred to as the “optional expansion.”

Financing. The costs of the Medicaid program are generally shared between states and the federal government based on a set formula. The federal government’s contribution toward reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures is known as federal financial participation. The percentage of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government is known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP).

For most families and children, SPDs, and pregnant women, California generally receives a 50 percent FMAP—meaning the federal government pays one‑half of Medi‑Cal costs for these populations. However, a subset of children in families with higher incomes qualifies for Medi‑Cal as part of CHIP. Currently, the federal government pays 88 percent of the costs for children enrolled in CHIP and the state pays 12 percent. (We describe recent federal actions that affect CHIP funding later in this write‑up.) Finally, under the ACA, the federal government paid 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to the optional expansion population from 2014 through 2016. Beginning in 2017, the federal cost share decreased to 95 percent, phasing down to 94 percent in 2018 and down further to 90 percent by 2020 and thereafter.

Delivery Systems. There are two main Medi‑Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: fee‑for‑service (FFS) and managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi‑Cal FFS may generally obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi‑Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person per month, regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi‑Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi‑Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health services in a timely manner. (In some counties, Medi‑Cal managed care plans also provide long‑term services and supports, including institutional care in skilled nursing facilities and certain home‑ and community‑based services.) Managed care enrollment is mandatory for most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, meaning these beneficiaries must access most of their Medi‑Cal benefits through the managed care delivery system. In 2018‑19, more than 80 percent of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are projected to be enrolled in managed care.

Managed Care Models. The number and types of managed care plans available vary by county, depending on the model of managed care implemented in each county. Counties can generally be grouped into four main models of managed care:

- County Organized Health System (COHS). In the 22 COHS counties, there is one county‑run managed care plan available to beneficiaries.

- Two‑Plan. In the 14 Two‑Plan counties, there are two managed care plans available to beneficiaries. One plan is run by the county and the second plan is run by a commercial health plan.

- Geographic Managed Care (GMC). In GMC counties, there are several commercial health plans available to beneficiaries. There are two GMC counties—San Diego and Sacramento.

- Regional. Finally, in the Regional model, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries across 18 counties.

Imperial and San Benito Counties have managed care plans that are not run by the county and do not fit into one of these four models. In Imperial County, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries, and in San Benito, there is one commercial health plan available to beneficiaries.

Overview of the Medi‑Cal Budget

The Governor’s budget revises estimates of General Fund spending in 2017‑18 upward by $544 million (2.8 percent) relative to what was assumed in the 2017‑18 Budget Act. The Governor’s budget further proposes $21.6 billion for Medi‑Cal from the General Fund in 2018‑19, an increase of $1.5 billion (7.6 percent) over revised 2017‑18 estimates. In terms of federal funds, the Governor’s budget revises estimates of federal spending in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 downward from previous estimates by $5.2 billion (7.6 percent). The Governor’s budget further estimates $63.7 billion in federal funding for Medi‑Cal in 2018‑19, an increase of $3.5 billion (5.4 percent) over revised 2017‑18 estimates. Below, we summarize the main factors that contribute to changes in the Medi‑Cal budget in both the current and the upcoming fiscal years.

Estimated and Proposed General Fund Spending

Current‑Year Adjustments. Increased estimated General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 reflects the net effect of multiple adjustments, the most significant of which include:

- One‑time costs of about $300 million for retrospective payments to the federal government related to prescription drug rebates. Most of the increased costs from these payments is the result of a shift in timing, where some payments that were planned to be made in 2016‑17 have been delayed until 2017‑18.

- Offsetting savings of about $270 million from a higher estimate of prescription drug rebates in managed care. Higher estimates for 2017‑18 are based on actual rebate amounts coming in higher than previously budgeted.

- Costs of about $200 million to correct a budgeting methodology used to construct estimates of managed care costs that previously underestimated costs for SPDs.

- Higher projected General Fund spending of about $170 million related to a reduction in hospital quality assurance fee (HQAF) revenues available to offset General Fund costs in Medi‑Cal. The amount of HQAF revenues available to offset General Fund costs is tied to the total amount of supplemental Medi‑Cal payments made to private hospitals, the nonfederal share of which are financed with HQAF revenues. A technical change to how much federal funding is available for these supplemental payments resulted in lower total payments in some years and, therefore, decreased estimated HQAF revenues available to offset General Fund Medi‑Cal costs in 2017‑18.

Budget‑Year Changes. Year‑over‑year growth in General Fund Medi‑Cal spending in 2018‑19 largely reflects the net effect of the following major factors:

- Higher projected spending of $540 million to backfill Proposition 56 tobacco excise tax revenues that, while offsetting General Fund Medi‑Cal costs in 2017‑18, are proposed under the Governor’s budget to instead pay for supplemental payments to certain providers in 2018‑19. We describe the Governor’s proposed allocation of Proposition 56 revenues in a later section.

- Higher projected spending of $300 million to reflect a full year of an assumed reduction in federal funds, continuing from 2017‑18, for CHIP. The lost federal funds are assumed to be backfilled with an equivalent amount of General Fund. We discuss this assumption and recent federal actions related to CHIP funding in a later section.

- Increased costs of roughly $200 million related to the state’s responsibility for a higher share of costs for the ACA optional expansion. The state’s share of cost for newly eligible beneficiaries increases from an effective 5.5 percent in 2017‑18 to an effective 6.5 percent in 2018‑19.

- Increased costs of about $130 million related to the planned expansion into additional counties of the Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System waiver, a joint federal‑state‑county demonstration project aimed at providing a full continuum of substance use disorder services to Medi‑Cal enrollees.

- Higher projected spending in the hundreds of millions of dollars related to general growth in health care costs.

Federal Funding Changes

Changes in federal funding in Medi‑Cal assumed in the Governor’s budget—a decrease in 2017‑18 relative to prior estimates and an increase in 2018‑19 relative to revised 2017‑18 estimates—are also the result of a variety of factors. We briefly summarize the impact of two of the major factors below.

ACA Optional Expansion Retroactive Managed Care Rate Recoupment. When the state expanded Medi‑Cal eligibility under the ACA in January 2014, it was necessary to develop capitated rates that would be paid to managed care plans to provide health care services to the newly eligible population. In the absence of experience on the cost of providing health care to this new population, there was significant uncertainty about the appropriate level of the capitated rates. In recognition of this uncertainty, capitated rates for the expansion population were initially set relatively high, with the understanding that any excess funding provided to managed care plans would be recouped retroactively if actual experience turned out to be less costly than initial assumptions.

Since January 2014, the costs of providing health care services to the optional expansion population have come in below expectations, creating the need to recoup significant funds from the managed care plans. Specifically, DHCS has identified $5.3 billion in recoupments for the period from July 2015 through December 2016 that will be collected from managed care plans during 2017‑18. Since the federal government paid 100 percent of capitated rates for the optional expansion population during this period, these recouped funds will be returned to the federal government. These retroactive recoupments mean that net federal funding in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 is $5.3 billion less than it otherwise would be, and the absence of recoupments related to the ACA optional expansion in 2018‑19 is the largest factor contributing to the year‑over‑year increase in federal funding budgeted for Medi‑Cal in 2018‑19. Capitated rates have since been reduced to reflect actual experience, such that the need for additional recoupments in the future should be relatively limited.

Changes to Hospital Supplemental Payment Programs. The state operates various supplemental payment programs that provide increased reimbursements to various Medi‑Cal provider types, including public and private hospitals. In 2016, the federal government finalized a sweeping set of regulations related to managed care payments in Medicaid that had significant implications for many of the state’s supplemental payment programs. In order to comply with the final regulations, the state has restructured some aspects of key hospital supplemental payment programs. In some cases, this restructuring is resulting in shifts in the timing of supplemental payments, totaling in the billions of dollars. These timing shifts account for a significant portion of the reduced federal funding in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18. (The timing shifts also affect spending from related state special funds.) In addition to changes to hospital supplemental payment programs resulting from the federal managed care regulations, changes to the calculation of maximum payments allowed in these programs, such as under the HQAF program described above, also contribute to lower federal funds in 2017‑18.

In the sections that follow, we (1) review the administration’s caseload estimates for the Medi‑Cal program, (2) describe the administration’s calculation of Medi‑Cal funding available under Proposition 55, (3) discuss recent federal actions related to CHIP, and (4) assess the administration’s proposed plan for allocating Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenues.

Caseload Projections

According to the Medi‑Cal Eligibility Data System, there were about 13.4 million people enrolled in Medi‑Cal in August 2017. This count includes over 3.8 million enrollees—mostly childless adults—who became newly eligible for Medi‑Cal under the ACA optional expansion. A substantial number of individuals who were previously eligible—sometimes referred to as the “ACA mandatory expansion”—are also assumed to have enrolled as a result of eligibility simplification, enhanced outreach, and other provisions and effects of the ACA. After several years of significant enrollment growth largely due to the ACA, the caseload appears to have stabilized. In the following sections, we describe recent historical trends in various components of the Medi‑Cal caseload and projections in the Governor’s budget for Medi‑Cal enrollment in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

Historical Trends

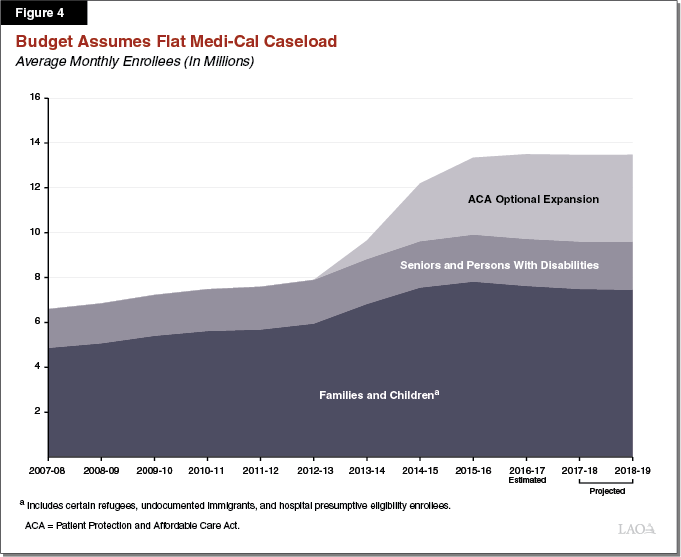

Figure 4 displays over a decade of observed and estimated caseload for the major categories of enrollment in Medi‑Cal: (1) families and children, (2) SPDs, and (3) the ACA optional expansion.

Families and Children Caseload Typically Countercyclical to State Economy. Historically, the families and children caseload has been countercyclical to changes in the state’s economy—meaning enrollment has tended to increase during an economic downturn and decrease during an economic expansion. In the last recession, which formally lasted from December 2007 through June 2009, the families and children caseload did increase; however, enrollment did not decline in the years that followed as might have been expected, with growth continuing through 2015‑16. This departure from the traditional countercyclical pattern for families and children in part reflects a shift of CHIP enrollees into the families and children caseload in Medi‑Cal in 2013‑14, as well as the effect of the mandatory expansion described above. These factors, which pushed families and children enrollment higher than it otherwise would be in an expanding economy, now appear to have taken their course and the families and children caseload has begun to decline. Specifically, the administration estimates that the families and children caseload declined 2 percent in 2016‑17.

Growth in SPD Enrollment Slowed in Recent Years. Both the seniors caseload and the persons with disabilities caseload have typically grown at a rate of roughly between 2 percent and 3 percent annually, and are typically less affected by changes in the state’s economy. In a departure from the historical trend, annual growth in seniors enrollment spiked to above 5 percent from 2013‑14 through 2015‑16, but has returned to the historical trend since 2016‑17. In contrast, growth in enrollment of persons with disabilities slowed beginning in 2013‑14 and the caseload actually declined in 2015‑16 and 2016‑17. The overall net effect of these offsetting effects is growth in SPD enrollment of less than 2 percent since 2015‑16—slower than would have been expected based on the historical trend.

The exact reasons for the departure from the historical trend for SPDs are not clear, but they likely relate to the implementation of the ACA. Unexpected faster growth in the seniors caseload from 2013‑14 through 2015‑16 could potentially have been due to the effect of the mandatory expansion. Alternatively, the growth in the seniors caseload might have been the result of delays in removing enrollees from the caseload that had changes in circumstances that made them no longer eligible. Some administrative processes in Medi‑Cal experienced delays during this period because of increased workload from significant ACA‑related enrollment. Unexpected declines in the enrollment of persons with disabilities may be related to some individuals enrolling in Medi‑Cal as part of the ACA optional expansion instead of as part of the persons with disabilities caseload. In any given year, individuals enter and exit the persons with disabilities caseload—the net growth or decline in the caseload in any given year is the difference between the entrances and the exits. It may be that, after Medi‑Cal eligibility was expanded in 2014, some individuals that previously would have entered the persons with disabilities caseload instead entered the optional expansion caseload. This would result in declines in the persons with disabilities caseload being offset by a portion of the increase in the ACA optional expansion caseload.

ACA Optional Expansion Caseload Is Stabilizing. The optional expansion population grew rapidly beginning in January 2014, but growth has since slowed significantly and appears to be stabilizing. In 2016‑17, the administration estimates that the optional expansion population grew by only 0.1 percent.

Governor’s Budget Caseload Projections

Governor’s Budget Projects Flat Overall Caseload in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. The Governor’s budget projects an average monthly Medi‑Cal caseload of 13.5 million in 2017‑18, a slight decrease of 0.5 percent relative to estimated total caseload in 2016‑17. The budget further projects the Medi‑Cal caseload to remain virtually flat in 2018‑19. Within the total caseload projection, the budget assumes that (1) the families and children caseload will continue to slowly decline; (2) the seniors caseload will continue to grow consistent with historical trends and the persons with disabilities caseload will be flat, resulting on net in modest growth in the SPD caseload; and (3) the ACA optional expansion caseload will experience slow growth.

Administration’s Caseload Projections Appear Reasonable. We have reviewed the administration’s caseload estimates and find them to be reasonable. As we have noted in recent years, substantial ACA‑related changes have made it challenging to project caseload. For example, the unanticipated decline in the persons with disabilities caseload makes it challenging to anticipate how this component of the caseload will change in the future. However, we expect that the factors leading to this decline are likely not ongoing and think the administration’s assumption that this caseload will remain flat in 2018‑19 (ending the recent downward trend) is appropriate. We also expect that the families and children caseload will continue to decline gradually as the state’s economy continues to expand, consistent with the administration’s projections. Ultimately, we expect the optional expansion caseload to also follow a countercyclical pattern. Given remaining uncertainty about this newly eligible population, however, we think it is prudent to assume the optional expansion caseload may continue to slowly grow. We will provide the Legislature an updated assessment of DHCS’ caseload projections at the May Revision when additional caseload trend data are available.

Proposition 55

In 2016, voters passed Proposition 55, which extended tax rate increases on high‑income Californians. Proposition 55 includes a budget formula that goes into effect in 2018‑19. This formula requires the Director of Finance to annually calculate the amount by which General Fund revenues exceed constitutionally required spending on schools and the “workload budget” costs of other government programs that were in place as of January 2016. One‑half of General Fund revenues that exceed constitutionally required spending on schools and workload budget costs, up to $2 billion, are directed to increase funding for existing health care services and programs in Medi‑Cal. The Director of Finance is given significant discretion in making calculations under this formula. Under calculations made for the 2018‑19 budget, the Director of Finance finds that General Fund revenues do not exceed constitutionally required spending on schools and workload budget costs. As a result, the Governor’s budget provides no additional funding for Medi‑Cal pursuant to the Proposition 55 formula. Our office is reviewing the administration’s approach to the Proposition 55 formula and will provide our comments to the Legislature at a later time.

Federal Reauthorization of CHIP Funding

Background

CHIP Provides Health Insurance to Low‑Income Children. CHIP is a joint federal‑state program that provides health insurance coverage to children in low‑income families, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. States have the option to use federal CHIP funds to create a stand‑alone CHIP or to expand their Medicaid programs to include children in families with higher incomes (commonly referred to as Medicaid‑expansion CHIP). California transitioned from providing CHIP coverage through its stand‑alone Healthy Families Program to providing CHIP coverage through Medi‑Cal. With this transition, completed in the fall of 2013, Medi‑Cal (through CHIP) generally provides coverage to children in families with incomes up to 266 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Some infants and pregnant women in families with incomes up to 322 percent of the FPL may also be eligible through CHIP for Medi‑Cal. The administration estimates that there will be around 1.3 million beneficiaries enrolled in CHIP coverage in 2018‑19.

Federal Cost Share for CHIP Is Traditionally Higher Than for Medicaid. Traditionally, the federal government provides a higher FMAP for CHIP coverage in California relative to Medicaid. The historical FMAP for the CHIP population has been 65 percent (compared to the 50 percent FMAP traditionally for Medi‑Cal), although this has been further enhanced to 88 percent by the ACA, as discussed below.

CHIP Funding Is Capped. Unlike Medi‑Cal, CHIP is not an entitlement program. States receive annual allotments of CHIP funding based on their CHIP FMAP and historical CHIP spending. Generally, states receive allotments that are sufficient to cover the federal share of CHIP expenditures for the full federal fiscal year (FFY). (A FFY runs from October 1 through September 30.) If a state does not spend its full annual allotment in a given year, the state may continue to draw down unspent funds in the next year.

The ACA and CHIP

ACA Authorized an Enhanced FMAP for CHIP, but Congress Had Only Appropriated Funding Through September 2017. Beginning in FFY 2015‑16, the ACA authorized an enhanced FMAP for CHIP through FFY 2018‑19. Under the ACA, California’s CHIP FMAP increased from 65 percent to 88 percent. However, at the time of congressional reauthorization for an enhanced FMAP for CHIP, Congress had appropriated funding for CHIP only through FFY 2016‑17 (ending September 30, 2017).

ACA Maintenance‑of‑Effort (MOE) Requirements for CHIP and Medicaid. Under an ACA MOE provision, states that operate CHIP through their Medicaid programs are required to maintain their March 23, 2010 Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children through the end of FFY 2018‑19. The implications of these MOE requirements are uncertain for California because the state transitioned from a stand‑alone CHIP to a Medicaid‑expansion CHIP after March 2010. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will need to clarify the implications of the ACA MOE requirement for California.

Recent Federal Action

Congressional appropriation of federal funding for CHIP lapsed on September 30, 2017. However, California continued to operate CHIP at the higher 88 percent FMAP using a combination of rollover funding from the state’s FFY 2016‑17 allotment and funding redistributed from other states to California by CMS. On January 22, 2018, Congress passed (and the President later signed) a reauthorization of federal funding for CHIP, including the following major components:

- Appropriates Funding for CHIP Through FFY 2022‑23. States will continue to receive annual allotments to cover the federal share of CHIP expenditures until September 2023. Annual allotments will continue to be calculated based on a state’s CHIP FMAP and historical CHIP spending.

- Maintains Enhanced CHIP FMAP Under ACA Through FFY 2018‑19. States will continue to receive the enhanced FMAP for CHIP authorized by the ACA until September 2019. As previously mentioned, under the ACA, California’s current CHIP FMAP is 88 percent. As we will discuss later, federal funding at this higher FMAP will reduce the state’s General Fund costs for CHIP in 2017‑18, 2018‑19, and the first quarter of 2019‑20.

- Begins Ratcheting Down the Enhanced CHIP FMAP in FFY 2019‑20 and Returns to Traditional CHIP FMAP in FFY 2020‑21. For FFY 2019‑20 (starting October 1, 2019), states will receive half of their FMAP enhancement for CHIP authorized by the ACA which, in California, results in a 76.5 percent FMAP instead of an 88 percent FMAP until September 2020. For FFY 2020‑21 (beginning October 1, 2020), states will return to their traditional CHIP FMAPs which, in California, is a 65 percent FMAP.

- Maintains MOE Requirement for CHIP Under ACA Through FFY 2022‑23. As previously mentioned, the ACA required states to maintain their March 23, 2010 Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children through the end of FFY 2018‑19. Federal reauthorization of CHIP funding generally extends the ACA’s MOE requirement for CHIP until September 2023.

- Permits States to Limit Income Eligibility to 300 Percent of the FPL Starting in FFY 2019‑20. One exception to the extension of the ACA’s MOE requirement for CHIP through September 2023 is for children in families with household incomes above 300 percent of the FPL. Starting October 1, 2019, states can choose to limit income eligibility for CHIP to at or below 300 percent of the FPL. (Children in families with household incomes at or below 138 percent of the FPL would continue to be covered by Medicaid.) Only a small number of children in families with household incomes above 300 percent of the FPL are currently eligible for CHIP in California.

We note that as of the time of our finalizing this budget analysis, Congress passed (and the President later signed) legislation authorizing CHIP funding (at the traditional CHIP FMAP) and the ACA’s MOE requirement for CHIP for an additional four years—through FFY 2026‑27.

State Budget Implications

Due to congressional appropriations made after the administration finalized its proposed 2018‑19 budget, the proposed state budget makes assumptions about the reauthorization of federal funding for CHIP that differ from the recent federal action outlined above.

2018‑19 Proposed Budget Assumed Funding for CHIP Appropriated at Traditional CHIP FMAP, Beginning on January 1, 2018. The proposed 2018‑19 state budget assumed federal funding for CHIP would be reauthorized, but not at California’s ACA‑enhanced CHIP FMAP of 88 percent. Instead, it assumed the state would receive its traditional CHIP FMAP of 65 percent starting January 1, 2018. (The 2017‑18 budget enacted last June had assumed a return to the traditional CHIP FMAP of 65 percent beginning on October 1, 2017.)

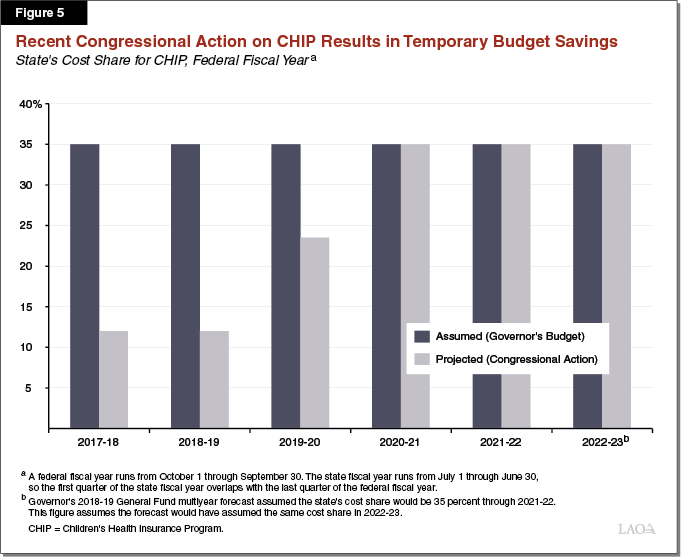

Federal Action Reduces Estimated General Fund Medi‑Cal Costs by About $300 Million in 2017‑18 and About $600 Million in 2018‑19. Assuming current caseload and program spending trends continue, reauthorization of federal CHIP funding at the enhanced FMAP of 88 percent will reduce estimated General Fund Medi‑Cal costs by about $300 million in 2017‑18 and about $600 million in 2018‑19—relative to the Governor’s proposed 2018‑19 budget assumptions. The Governor’s May Revision budget proposal will reflect this downward adjustment of General Fund costs totaling $900 million over 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. Figure 5 reflects the reduction in the state’s cost share in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

Reductions in CHIP FMAP in 2019‑20 to Increase General Fund Costs Relative to 2018‑19. However, starting in 2019‑20, the scheduled reduction of California’s CHIP FMAP from 88 percent to 76.5 percent will increase General Fund costs by about $225 million relative to 2018‑19 (based on current caseload and program spending). A return to California’s traditional CHIP FMAP of 65 percent in 2020‑21 will further increase those costs by $525 million relative to 2018‑19. Figure 5 also reflects these increases in the state’s cost share after 2018‑19. (We note, however, that General Fund costs in CHIP are now projected to be lower in 2019‑20, and the same in 2020‑21, than as assumed in the Governor’s January budget.) As previously mentioned, federal reauthorization of CHIP funding generally extended the ACA’s MOE requirement for CHIP until September 2027. If CMS determines that California is subject to the ACA MOE requirements (as the administration currently assumes), reductions in available CHIP funding could necessitate changes in state spending to maintain current CHIP eligibility levels. If California is not subject to the ACA MOE requirements, the state would have more flexibility to change eligibility levels as a means to reduce costs in the future.

Proposition 56

Proposition 56 raised state taxes on tobacco products and dedicates the majority of associated revenues to Medi‑Cal on an ongoing basis. With Proposition 56 revenues that are dedicated to Medi‑Cal, the Legislature can use this funding for two main purposes: (1) augmenting the program, such as, for example, by increasing Medi‑Cal provider payments and (2) offsetting General Fund spending on cost growth in Medi‑Cal. In this piece, we describe: (1) the 2017‑18 budget agreement on how funds were to be allocated to these two purposes in both 2017‑18 and 2018‑19, (2) the Governor’s updated plan for expenditures over the two‑year period, (3) the specific provider payment increases included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement, and (4) the Governor’s proposal to add a new service category—home health services—for provider payment increases.

The 2017‑18 Budget Agreement

The 2017‑18 budget package included a two‑year budget agreement on Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal. Broadly speaking, the agreement dedicates Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal between the two main uses of Proposition 56 funding described above: (1) increasing payments for certain Medi‑Cal providers and (2) paying for anticipated growth in state Medi‑Cal costs over and above 2016‑17 Budget Act levels, which offsets what otherwise would be General Fund costs. Figure 6 summarizes the use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal under the 2017‑18 budget agreement between the Legislature and the administration. Specifically, it authorized up to $546 million in 2017‑18 and up to $800 million in 2018‑19 in provider payment increases, with any remaining Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal funding from 2017‑18 ($711 million) and 2018‑19 ($125 million) to be used to offset General Fund spending on cost growth in the program.

Figure 6

The 2017‑18 Budget Agreement on the Use of

Proposition 56 Funding in Medi‑Cal

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Total |

|

|

Provider payment increasesa |

$546 |

$800 |

$1,346 |

|

Offsets to General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal cost growthb |

711 |

125 |

836 |

|

Total Proposition 56 Spending in Medi‑Cal |

$1,257c |

$925c |

$2,182 |

|

aThe 2017‑18 budget agreement authorized supplemental provider payment funding amounts up to the amounts listed in this figure. bAny Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal funding not allocated to augment the program, such as to increase provider payments, is available to offset General Fund spending. cAmounts reflect the administration’s projection of total Proposition 56 revenue allocated to Medi‑Cal as of the 2017‑18 Budget Act. The Governor’s 2018‑19 budget revises upward estimated Proposition 56 revenue allocated to Medi‑Cal in both 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. |

|||

For 2017‑18, the 2017‑18 budget agreement came with a structure of fixed dollar amount or fixed percentage increases in provider reimbursement levels that applied to an identified set of Medi‑Cal services ranging from physician and dental visits to certain women’s health visits. Moreover, it is our understanding that the budget agreement provides that for any provider payment increases in 2018‑19 above the total 2017‑18 amount, 70 percent is to be dedicated to physician services payment increases and 30 percent is to be dedicated to dental services payment increases. As the 2017‑18 budget agreement only goes through 2018‑19, future use of Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal will be determined through the annual budget process.

Overview of the Governor’s 2018‑19 Budget Proposal

Governor’s 2018‑19 Budget Proposal Essentially Consistent With the 2017‑18 Budget Agreement. The Governor proposes spending the maximum amount authorized in the 2017‑18 budget agreement ($1.346 billion) on provider payment increases within the provider and service categories designated in the 2017‑18 agreement. As such, we find that the Governor’s budget proposal essentially adheres to the agreement. Specifically, the Governor’s budget proposal would extend the provider payment increases structured in the 2017‑18 agreement into 2018‑19 and allocate the remaining Proposition 56 funding dedicated to provider payment increases to pay for new provider payment increases above 2017‑18 levels.

Figure 7 summarizes the Governor’s updated 2018‑19 budget proposal on the use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal. The figure shows that the Governor proposes spending slightly more Proposition 56 resources from 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 on provider payment increases—$1.378 billion—than the maximum amount authorized under the two‑year 2017‑18 budget agreement. The increase is attributable to the Governor’s proposed payment rate increase for Medi‑Cal home health services, which we discuss later on in this analysis.

Figure 7

The Governor’s 2018‑19 Budget Proposal on

Proposition 56 Funding in Medi‑Cal

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Total |

|

|

Provider Payment Increases: |

|||

|

Provider categories in 2017‑18 agreementa |

$412 |

$412 |

$823 |

|

Additional funding to be committedb |

— |

523 |

523 |

|

Home health services (new) |

— |

32 |

32 |

|

Subtotals |

($412) |

($966) |

($1,378) |

|

Offsets to General Fund Spending on Medi‑Cal Cost Growthc |

$711 |

$169 |

$880 |

|

aAmounts listed represent annual cost estimates of supplemental payments structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement by the fiscal year that the affected services are rendered. As a result, the amounts do not account for supplemental payments that are delayed into subsequent fiscal years and are not directly reflected in the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget display totals. bAllocated by the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget to broad provider categories included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement without a planned payment structure. cAny Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal funding not allocated to augment the program, such as to increase provider payments, is available to offset General Fund spending. |

|||

Governor Does Not Provide a Detailed Spending Plan for $523 Million in Proposition 56 Funding That Is Available for Provider Payment Increases in 2018‑19 . . . Under the Governor’s overall Proposition 56 budget proposal, we estimate that $523 million in total Proposition 56 funding is available for additional provider payment increases beyond those structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. (We note that this amount represents a preliminary estimate that is subject to change at the May Revision.) However, the Governor’s budget proposal does not include a detailed plan for how to structure these additional provider payment increases.

. . . Intentionally Leaving Details of the Allocation to Be Worked Out With the Legislature. The Governor’s proposal to allocate this funding broadly for additional provider payment increases without a detailed plan affords the Legislature an opportunity to provide input into how these new payments are structured. For example, the Legislature could identify new categories of providers or services to which to commit this available funding. Alternatively, the Legislature could identify different uses for this funding. For example, the Legislature could commit some or all of this amount to offset General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal cost growth or further augment the Medi‑Cal program in ways other than increasing provider payments.

In the sections that follow, we provide more detailed information on the Governor’s budget proposal for (1) the continuation into 2018‑19 of provider payment increases included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement and (2) a new provider payment increase for home health services.

Governor’s Budget Proposal: Provider Payment Increases Included in the 2017‑18 Budget Agreement

Increases Structured as Supplemental Payments. The provider payment increases discussed in this section take the form of fixed supplemental payments paid on top of standard reimbursement rates for the affected services. Since the federal government will share in the cost of these supplemental payments (at standard FMAP levels), federal approval of the payments is necessary. Certain 2017‑18 supplemental payments began to be made in late 2017, while others are expected to be implemented in early 2018. Retroactive supplemental payments for services rendered dating back to July 1, 2017 are generally expected to be made in April and May of 2018.

Governor’s 2018‑19 Budget Proposes to Spend Maximum Amount Authorized for Provider Payment Increases in 2017‑18 Budget Agreement . . . As discussed above, the Governor proposes spending the maximum amount authorized in the 2017‑18 budget agreement ($1.346 billion) on provider payment increases within the provider and service categories designated in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. The agreement designated supplemental payment levels for a selected set of services at an estimated annual cost to the state of $546 million. Figure 8 summarizes the maximum funding amounts by which the provider and service categories could be increased under the 2017‑18 budget agreement.

Figure 8

2017‑18 Budget Agreement on Proposition 56

Provider Payment Increasesa

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Two‑Year Total |

|

|

Authorized maximum increases to supplemental payments: |

|||

|

Physician servicesb |

$325 |

$503 |

$828 |

|

Dental servicesb |

140 |

216 |

356 |

|

Women’s healthc |

50 |

50 |

100 |

|

Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabledc |

27 |

27 |

54 |

|

AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Programc |

4 |

4 |

8 |

|

Totals |

$546 |

$800 |

$1,346 |

|

aThe 2017‑18 budget agreement authorized supplemental provider payment funding amounts up to the amounts listed in this figure. bThe 2017‑18 Proposition 56 budget agreement authorized physician and dental services provider payment increases to be increased by up to $254 million between 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 (bringing total Proposition 56 funding for increased provider payments to $800 million). After 2018‑19, continuation of physician and dental services provider payment increases is expected to be reevaluated. cPayment increases are intended to be ongoing, though they might be funded with an alternative fund source following 2018‑19. |

|||

. . . And Reflects Freed‑Up Funding Due to Revised Cost Estimates. Under the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget, the estimated annual cost to the state of these designated supplemental payments has been revised downward to $412 million in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. It is our understanding that this downward revision is largely the result of revised assumptions related to the federal share of cost for the majority of these payments being higher than previously projected. The Governor’s 2018‑19 budget proposes to spend the funding freed up as a result of the lower updated cost estimates on additional provider payment increases beginning in 2018‑19. Figure 9 summarizes the Governor’s 2018‑19 Proposition 56 budget proposal as it relates to the provider payment increases included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. This figure shows (1) the amount of annual Proposition 56 funding needed to fully fund the provider payment increases specifically structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement and (2) the additional funding available ($523 million) to be committed under the Governor’s proposal to new provider payment increases beyond those structured in the agreement.

Figure 9

The Governor’s 2018‑19 Proposal for Supplemental Payments

Included in the 2017‑18 Agreement

(Proposition 56 Revenues, in Millions)

|

2017‑18a |

2018‑19a |

Additional Funding |

Total |

|

|

Physician servicesc |

$252 |

$252 |

$324 |

$828 |

|

Dental servicesc |

95 |

95 |

166 |

356 |

|

Women’s healthd |

50 |

50 |

— |

100 |

|

Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabledd |

12 |

12 |

— |

23 |

|

AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Programd |

3 |

3 |

— |

7 |

|

Funding expected to be reallocated among provider categoriese |

— |

— |

32 |

32 |

|

Totals |

$412 |

$412 |

$523 |

$1,346 |

|

aAmounts listed represent annual cost estimates of supplemental payments structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement by the fiscal year that the affected services are rendered. Therefore, while corresponding to the display of amounts in the 2017‑18 budget agreement table, the amounts will differ from other Governor’s budget documents displaying expenditures on a cash basis. bAllocated by the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget to broad provider categories included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement without a planned payment structure. cAfter 2018‑19, continuation of the physician and dental services provider payment increases is expected to be reevaluated. dPayment increases are intended to be ongoing, though they might be funded with an alternative fund source following 2018‑19. eReflects available supplemental payment funding originally allocated to provider categories that we do not expect to be adjusted above the cost of the supplemental payments as structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. |

||||

Below, we discuss in greater detail the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget proposal as it relates to the supplemental payment provider categories included in the 2017‑18 budget agreement.

Supplemental Payments for Physician Services. The 2017‑18 budget agreement designated physician services, such as doctors’ visits, to receive the majority of supplemental payments using Proposition 56 funding in both 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. This funding will increase physician payments for the targeted types of physician services by between 20 percent and 45 percent compared to their standard FFS reimbursement levels. These supplemental payments will occur in both the FFS and managed care delivery systems. The federal government has approved the physician services supplemental payments within the FFS delivery system. Federal approval remains pending for these payments within the managed care delivery system but is expected to be received in early 2018, when supplemental payments across the two delivery systems are expected to begin. They are expected to expire after 2018‑19, pending a new agreement being reached in the budget development process on whether and how to fund physician services payment increases in subsequent years.

Under the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget, the estimated state cost of the physician services supplemental payments structured in the budget agreement has been revised downward from $325 million annually to $252 million annually in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. The Governor proposes to use the funding freed up as a result of these lower updated cost estimates to fund additional physician services supplemental payments beginning in 2018‑19. Overall, the Governor proposes to spend $828 million from 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 Proposition 56 revenues on physician services supplemental payments. This amount is the same as the maximum amount authorized to be allocated to physician services supplemental payments in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. Of the $828 million of total proposed spending on physician services provider payment increases, $324 million has been only broadly allocated to this purpose without a detailed spending plan. For example, the Governor’s budget does not target this funding toward additional physician services or specify higher reimbursement amounts for physician services that currently receive supplemental payments. (We would note that a portion of this $324 million comprises funding that currently is not reflected in the Governor’s budget’s spending totals in 2018‑19, but is reserved for commitments in the budget year.)

Supplemental Payments for Dental Services. The 2017‑18 budget agreement dedicated Proposition 56 funding to pay for dental services supplemental payments in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. These supplemental payments are expected to expire after 2018‑19 pending a new agreement being reached on Proposition 56 funding for provider payment increases in subsequent years.

Under the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget, the estimated state cost of the dental services supplemental payments structured in the 2017‑18 budget agreement has been revised downward from $140 million annually to $95 million annually in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. The Governor proposes to use the funding freed up as a result of these lower updated cost estimates to fund additional dental services supplemental payments beginning in 2018‑19. Overall, the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget proposes to spend $356 million from 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 Proposition 56 revenues on dental services supplemental payments. This amount is the same as the maximum amount authorized to be spent on dental services supplemental payments under the 2017‑18 budget agreement. Of the $356 million of total proposed spending on dental services provider payment increases, $166 million has been only broadly allocated to this purpose without a detailed spending plan. For example, the Governor’s budget does not target this funding toward additional dental services or specify higher reimbursement amounts for dental services that currently receive supplemental payments. (We would note that a portion of this $166 million comprises funding that currently is not reflected in the Governor’s budget’s spending totals in 2018‑19.)

Supplemental Payments for Women’s Health. The 2017‑18 budget agreement allocated up to $50 million annually in Proposition 56 funding in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 for family planning services offered through the Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment Program. These supplemental payments are intended to be ongoing, though they might be funded with an alternative source following 2018‑19. The Governor’s budget proposes to spend the maximum amount authorized under the 2017‑18 budget agreement.

Supplemental Payments for Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled (ICF‑DDs). ICF‑DDs are health facilities that provide residential services to individuals with developmental disabilities. These supplemental payments are intended to be ongoing, though they might be funded with an alternative fund source following 2018‑19. The 2017‑18 budget agreement authorized up to $27 million annually in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 for supplemental payments for ICF‑DDs. Under the Governor’s budget, the estimated cost of these supplemental payments has been revised downward by over 50 percent due to federal limits on the amount by which ICF‑DD reimbursement levels can be further augmented using federal funds. Accordingly, under the Governor’s budget, the ICF‑DD supplemental payments are estimated to cost around $12 million annually in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. The Governor proposes to use the $31 million in funding freed up as a result of these lower updated cost estimates to fund additional supplemental payments beginning in 2018‑19. (We would note that this funding is not currently reflected in the Governor’s budget’s spending totals in 2018‑19.) It is uncertain to which provider or service categories this freed‑up funding would be allocated since the state does not appear to be able to use additional Proposition 56 funding to fund ICF‑DD supplemental payments above the amount budgeted in the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget proposal.

Supplemental Payments for AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program. The AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program provides home‑ and community‑based services (HCBS) to individuals with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as an alternative to nursing facility care or hospitalization. Such HCBS services could include, for example, skilled nursing services. These supplemental payments are intended to be ongoing, though they might be funded with an alternative fund source following 2018‑19. The 2017‑18 budget agreement provided up to $4 million annually in Proposition 56 funding in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 for this program, nearly doubling reimbursement levels for many or most of the services provided through the program. The Governor’s budget revised downward the annual cost of these supplemental payments to $3.4 million due to lower updated cost projections of how much Proposition 56 funding is needed to bring AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program reimbursement levels up to the levels determined in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. The Governor proposes to spend the $1 million in funding freed up as a result of these lower updated cost estimates on additional provider payment increases in 2018‑19. (We would note that this funding is not currently reflected in the Governor’s budget’s spending totals in 2018‑19.) However, it is uncertain whether the Governor intends this funding to be spent on higher supplemental payments in the AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program or whether the Governor intends to reallocate this funding to other provider or service categories.

Governor’s Budget Proposal: New Proposed Provider Payment Increase for Home Health Services

The Governor’s budget dedicates a portion of Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal funding to pay for payment rate increases for a health care service type—home health services—that was not targeted to receive payment increases in the 2017‑18 budget agreement. Relative to the agreement, this proposal increases the total amount of Proposition 56 revenue proposed to be used to increase Medi‑Cal provider payments and decreases the amount of Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal funding available to offset General Fund spending on cost growth in the program.

Home Health Services. Home health services are services provided to patients in their residence instead of an inpatient setting such as a hospital. Home health service providers such as home health agencies hire registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, and certified home health aides to—for example—administer patients’ oral medications, insert feeding tubes, and treat wounds. All Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are generally eligible for home health services as long as the services are medically necessary. Medi‑Cal reimburses home health services at levels based on the type of health professional who provides the services and the length of time needed. These services are available through the two main Medi‑Cal delivery systems, FFS and managed care, as well as through Medi‑Cal’s various HCBS waiver programs. (HCBS waiver programs allow states to deliver long‑term services and supports, such as home health services, to Medicaid beneficiaries in their residences.)

DHCS Identified Potential Problems With Access to Certain Home Health Services in Medi‑Cal. The department monitors access to home health services in Medi‑Cal FFS through federally mandated access monitoring and self‑generated studies on access to particular services. For example, in a late 2016 self‑generated study of access to home health services largely within the California Children’s Services program, DHCS concluded there was a gap between the number of hours authorized for eligible beneficiaries and the number of hours rendered by providers. While the study could not explain the disparity, it cited for additional study specific barriers to access, including provider rates, staffing shortages, and geographic disparities. The administration cites this study in support of its proposal to increase certain home health service provider rates in 2018‑19.

Proposed 2018‑19 Budget Would Increase Home Health Services Provider Rates by 50 Percent. Starting July 1, 2018, the administration proposes to increase provider rates for home health services participating in Medi‑Cal FFS and four HCBS waiver programs—the Home and Community‑Based Alternatives Waiver, the In‑Home Operations Waiver, the Pediatric Palliative Care Waiver, and the AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program—by 50 percent. The administration estimates the total cost of the provider rate increase in 2018‑19 would be $65 million—$41 million for the rate increase, and $24 million for an anticipated increase in utilization of home health services by 15 percentage points. The Governor’s budget proposes to fund the nonfederal share in 2018‑19—$32 million—using Proposition 56 revenues. While the administration proposes that these rate increases be ongoing, it does not identify funding for the nonfederal share after 2018‑19.

Issues for Consideration. As discussed above, the Governor’s budget proposes to use $32 million in Proposition 56 revenue that would otherwise be available to offset General Fund spending on cost growth in Medi‑Cal to increase payment rates for home health services. In support of its proposal, the administration has provided some evidence that access to home health services could be a challenge for certain Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. In deciding whether to approve the Governor’s proposal, however, we recommend that the Legislature consider the following:

- Whether the rate increases should be ongoing or limited term, given the uncertain cause of the gap between the number of authorized hours and rendered hours for home health services.

- Whether the rate increases should assume increased utilization of roughly 15 percentage points in 2018‑19 and, if not, whether the amount of Proposition 56 revenues allocated for these rate increases should be higher or lower to reflect a different assumption about changes in utilization.

Should the Legislature consider these issues and wish to increase payment levels for home health services in the amount proposed by the Governor’s budget, we would recommend the Legislature direct DHCS to conduct an additional study to determine the primary cause of the gap between the number of authorized hours and rendered hours for home health services in Medi‑Cal. We would also recommend the Legislature direct DHCS to report back to the Legislature on changes in utilization of home health services (and associated costs) in Medi‑Cal after the rate increases went into effect.

Department of State Hospitals

Overview

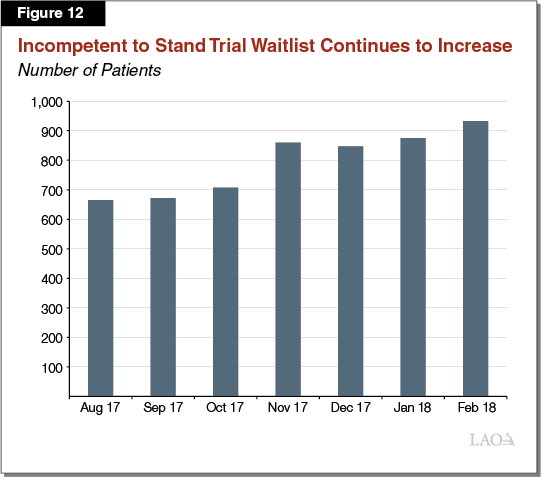

Department Provides Inpatient and Outpatient Mental Health Services. The Department of State Hospitals (DSH) provides inpatient mental health services at five state hospitals (Atascadero, Coalinga, Metropolitan, Napa, and Patton). In addition, DSH provides outpatient treatment services to patients in the community. Overall, the department is currently budgeted to treat about 6,500 patients in its facilities and another 700 in the community. Patients at the state hospitals fall into one of two categories: civil commitments or forensic commitments. Civil commitments are generally referred to the state hospitals for treatment by counties. Forensic commitments are typically committed by the criminal justice system and include individuals classified as Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST), Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity, Mentally Disordered Offenders (MDOs), or Sexually Violent Predators. Currently, about 90 percent of the patient population is forensic in nature. As of January 15, 2018, the department had about 1,100 patients awaiting placement, including about 900 IST patients.

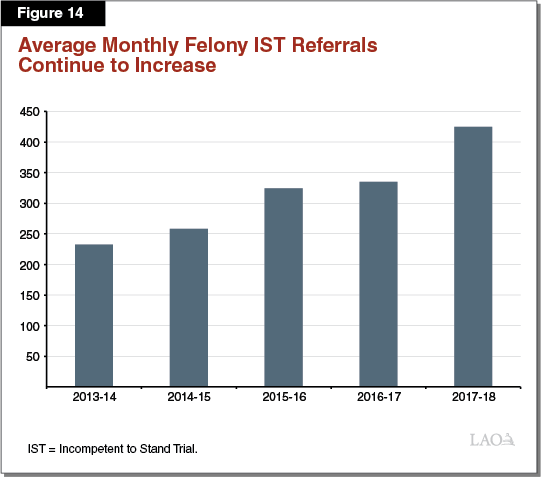

Spending Proposed to Increase by $226 Million in 2018‑19. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $1.9 billion ($1.8 billion from the General Fund) for DSH operations in 2018‑19, which is an increase of $226 million (13 percent) from the revised 2017‑18 level. This increase is primarily due to the implementation of various strategies intended to reduce the number of IST patients awaiting transfer, which we discuss in more detail below.

DSH‑Coalinga Expansion

Background