LAO Contact

April 4, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Repaying the CalPERS Borrowing Plan

Summary

State Beginning Repayments on Enacted Pension Borrowing Plan. The 2017‑18 budget package authorized a plan to borrow $6 billion from the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA)—an account that is essentially the state’s checking account—to make a one‑time supplemental payment to CalPERS. While annual state pension contributions will continue to rise over the next several years, this supplemental payment will reduce these contributions below what they would be otherwise. All funds that make pension payments, including the General Fund and most other state funds, will repay the loan over the next decade or so. While the General Fund started repaying the loan in 2017‑18, other funds will begin payments in 2018‑19.

Legislative Requirements on Repayments. Authorizing legislation gives the administration the discretion to determine the timing of funds’ repayments, but also includes a variety of requirements. In particular, the legislation requires the administration to: (1) ensure each fund pays its proportionate share of the loan’s principal and interest, (2) develop a tracking system for the repayments, and (3) publish in each fund’s condition statement the amount of the loan that is due and payable each year.

Administration’s Repayment Approach Raises Serious Concerns. The administration proposes $675 million in total repayments in 2018‑19, including $400 million from the General Fund and $275 million from other state funds. In our view, the basic elements of the administration’s plan are reasonable. We have serious concerns, however, about some choices the administration made. In particular, primarily because some funds have structural deficits, the administration shifts $8.5 million in repayment costs among state funds. As a result, some funds make payments on behalf of other funds despite having different fee payers and supporting different programs. Further, the administration does not display these cost shifts in public budget documents. The administration also allocates interest costs to the entire pool of funds, rather than individual funds. Consequently, some funds will pay more or less than their proportionate shares of interest. For instance, had the administration allocated interest costs by fund, the General Fund (all else equal) would save of tens of millions of dollars over the lifetime of the loan as it is repaying more quickly than other funds.

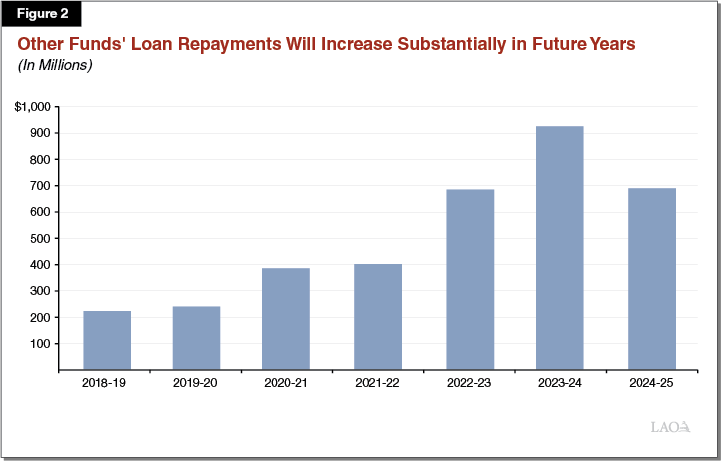

Issues Have Larger Outyear Implications. Under the administration’s plan, repayments among other state funds will double by 2021‑22 and quadruple by 2023‑24. If the administration maintains its repayment approach in future years, the issues described above will be exacerbated. As a result, the administration’s approach could lead to tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in principal and interest costs being distributed inappropriately across funds.

Recommended Approach. To address the concerns identified in this report, we recommend a modified approach. This recommended approach would: (1) be consistent with the authorizing legislation, (2) allocate costs appropriately and publicly, and (3) provide incentives to create more cost‑effective outcomes.

Introduction

State Recently Enacted Pension Borrowing Plan. As part of the 2017‑18 budget package, Chapter 50 (SB 84, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) approved the Governor’s May Revision proposal to borrow $6 billion from the state’s cash balances in the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA)—an account that is essentially the state’s checking account—to make a one‑time supplemental payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). While annual state pension contributions will continue to rise over the next several years, this supplemental payment will reduce these contributions below what they would be otherwise.

Plan Very Likely to Result in Long‑Term State Savings. The aim of this plan is to save the state money over the next few decades by slowing the pace at which the state’s annual pension costs rise. According to an analysis produced by CalPERS in September, the plan has a 95 percent chance to save the state money. The median scenario from the analysis suggests the plan would save the state $3.1 billion over 20 years. The actual savings associated with the plan will be higher or lower than this amount, potentially by billions of dollars, depending on a variety of factors, most notably CalPERS’ future investment performance.

Report Considers First Year of Implementation of Loan Repayments. Senate Bill 84 indicates that state funds must repay their respective shares of the loan in proportion to their pension costs, but also gives the Department of Finance (DOF) discretion to determine the timing of the repayments and the methodology for estimating the repayment costs across funds. As this is the first year that DOF will be allocating these repayments by fund, the purpose of this report is to help the Legislature review the administration’s approach. In this report, we first provide background on state funds, retirement liabilities, and debt repayments. Then, we outline the recently enacted pension borrowing plan. Next, we describe how the state is repaying the loan, including decisions made by the administration in 2018‑19. We then assess the administration’s repayment approach. Because our assessment identifies some serious concerns, we conclude with a recommended alternative approach that we believe is more consistent with legislative directives.

Background

In this section, we provide background on (1) the state’s use of various funds, (2) the state’s current retirement liabilities, and (3) the requirements for the state to address some of its outstanding debt under the provisions of Proposition 2 (2014).

State Funds

State Has Hundreds of Funds. The state conducts its financial affairs through hundreds of separate funds. We discuss three types of funds in this report. They are: (1) the General Fund, which is the state’s main operating account; (2) other state funds, which includes special funds, bond funds, and other “nongovernmental cost funds” (such as trust funds); and (3) federal funds.

Most Funds Have Specific Purposes. Whereas the General Fund receives revenues from various taxes and fees that can be used for any public purpose, other funds have programmatic restrictions. For instance, special funds have specific revenue sources (such as user fees) and programmatic uses established in state law. For legal and policy reasons, there generally needs to be a “nexus,” or connection, between the fees paid into a special fund and the services provided from those fee revenues. Bond funds also have legal restrictions on their use, as set forth in voter‑approved bond measures, and other nongovernmental cost funds, such as retirement trust funds, also have restrictions. Federal funds come from agencies of the federal government and are expended by state departments in accordance with federal rules.

State Can Make Loans Between Funds. When facing budget shortfalls in the past, the state has loaned money from special funds to the General Fund. These loans usually carry interest but have no set repayment period. The state also makes loans from the General Fund to special funds—for example, to support the establishment of a new program—and between special funds.

Funds’ Cash Held Together in PMIA. The funds described above all are separate in a budgetary sense, but not on a cash basis. That is, the actual cash associated with the General Fund and most other state funds is pooled together in the state’s portion of the PMIA. The PMIA effectively functions as a central checking account, receiving all revenues and paying all expenses associated with the various budgetary funds. (The PMIA also holds funds on behalf of cities, counties, and other local entities in the spearate Local Agency Investment Fund.) Over the last six months, the daily balance in the PMIA has averaged roughly $72 billion. The State Treasurer’s Office manages the PMIA, generally investing the money in low‑risk instruments with short‑term maturity schedules. In February 2018, the average return on these investments was 1.4 percent.

Retirement Liabilities

State Pensions Funded From Three Sources. The state provides pension benefits to retired state and California State University employees through the CalPERS pension system. CalPERS pensions are funded from three sources: investment gains, employer contributions, and employee contributions. Investment gains pay for about two‑thirds of current benefits, while employer and employee contributions pay for the remainder.

State Pension Plan Has Significant Unfunded Liability. Like many other pension systems around the country, CalPERS has an unfunded liability. Unfunded liabilities occur when assets on hand are less than the estimated cost of benefits earned to date. For 2015‑16, CalPERS estimates the unfunded liability is $60 billion. The state bears the cost of this unfunded liability, which it is addressing over a few decades by making additional annual contributions to the pension plan.

Employer Contribution Rates Are Increasing. At a meeting in December 2016, the CalPERS governing board voted to lower its investment return assumption from 7.5 percent to 7 percent over three years. By assuming less money comes into the system through investment gains, the state will be required to contribute more money to pay for current and future pension costs as well as a larger unfunded liability. As a result of this and other assumption changes, average employer contribution rates are projected to rise over the next few years.

Employer Contributions Paid From Each Fund. The General Fund and nearly all other funds have some payroll costs to employ state workers, and therefore also have associated pension costs. Each fund pays employer contributions to CalPERS based on its own state payroll costs. Some funds—like the Motor Vehicle Account—primarily support operations performed by state employees (such as registering vehicles), and therefore have relatively high associated state pension costs. Other funds—such as the Mental Health Services Fund—primarily pass funding through to local governments and therefore have low associated state pension costs. When employer contribution rates rise, the associated costs to each fund also rise.

Proposition 2

Key Provisions Regarding Debt Repayments. Proposition 2 requires the state to make minimum annual payments toward certain eligible debts through 2029‑30. (It also contains certain requirements related to the state’s rainy day fund.) A formula determines the required minimum payments, which can vary significantly with fluctuations in revenues, particularly those from capital gains. Over the next few years, the administration estimates Proposition 2 debt repayments will vary from $1.3 billion to $1.5 billion each year, but these requirements could be hundreds of millions of dollars higher or lower depending primarily on the future performance of the stock market.

Current Plan for Debt Repayments. While there is no overarching statutory plan in place for future Proposition 2 debt repayments, the Legislature and Governor have agreed—in some cases, informally, and, in a few cases, in state law—to prioritize certain debts that involve multiyear commitments. In addition to the CalPERS loan repayments under discussion in this report, Proposition 2 is being used to repay special fund loans to the General Fund, to repay certain amounts owed to schools and community colleges (called “settle up”), and to prefund retiree health benefits. (We discuss these uses in our December 21, 2017 budget and policy post Long‑Term Capacity for Debt Payments Under Proposition 2.)

Interest on Proposition 2 Debts. Some Proposition 2 debts carry no interest, such as settle up. Other Proposition 2 debts carry interest but the rates tend to be quite low. For instance, most special fund loans carry a fixed interest rate equal to the investment earnings rate of the PMIA on the day the loan was made. (In recent years, this rate has averaged 0.5 percent, although it has risen in recent months.)

Overview of CalPERS Borrowing Plan

This section provides an overview of the CalPERS borrowing plan as enacted by the 2017‑18 budget package and described in a subsequent analysis provided by the administration to the Legislature on September 28, 2017. (We refer to this as the “September report.”)

CalPERS Borrowing Plan Enacted in 2017‑18. As part of the 2017‑18 budget package, SB 84 approved the Governor’s May Revision proposal to borrow $6 billion from the PMIA to make a one‑time supplemental payment to CalPERS. State pension contributions will continue to rise over the next several years due to the recent changes in the pension plan’s investment assumptions, but this supplemental payment will reduce the state’s pension contributions below what they would be otherwise.

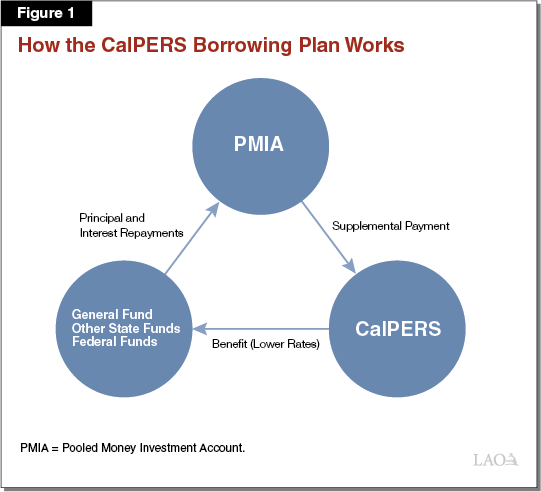

How the Plan Works. Figure 1 shows how this borrowing plan is meant to work. Under the plan, the State Controller transfers $6 billion from the PMIA to CalPERS, which CalPERS then invests to help pay down the unfunded liability. Over the next few years, funds that pay pension costs (including the General Fund, other state funds, and federal funds) accrue benefits through lower employer contributions costs relative to what they would be otherwise. Finally, funds that accrue these benefits are to repay the loan to the PMIA with interest.

Plan Very Likely to Save the State Money. The aim of this plan is to save the state money over the next few decades by slowing the pace at which the state’s annual pension contributions rise. The precise amount of savings will depend on many factors, including actual investment returns over the next few decades. An actuarial analysis by CalPERS in the September report suggests that, under the median scenario, the loan would save the state $3.1 billion over the next 20 years. Under the projections, these savings would begin to accrue in 2019‑20 and then grow over time. The growth in savings is faster in the next few years and then slows in the early to mid‑2020s.

State Has Already Transferred $4 Billion. Senate Bill 84 authorizes DOF to determine the timing of the $6 billion to be transferred from the PMIA to CalPERS. In a letter dated October 2, 2017, DOF directed the State Controller to transfer the $6 billion in three installments of $2 billion each on October 31, 2017, January 16, 2018, and April 17, 2018. These amounts were scheduled throughout the 2017‑18 fiscal year to minimize disruption to the state’s cash resources in the PMIA.

Repaying the Loan

In this section, we first describe the legislative requirements for repaying the loan, as well as initial decisions made regarding the repayments by DOF, as outlined in the September report. We then describe the administration’s repayment plan for 2018‑19.

Legislative Requirements and Initial Administrative Decisions

Loan to Be Repaid by 2030 or Sooner. Senate Bill 84 stipulates that the principal and interest payments of the loan must be fully repaid on or before June 30, 2030. Senate Bill 84, however, gives the administration discretion to determine the timing of the repayments. The administration indicated in its September report that it plans to repay the loan over an eight‑year period—that is, by June 30, 2025.

Interest Costs to Add to Repayment Amount. Under SB 84, interest on the loan is calculated quarterly using the two‑year United States Treasury rate for the prior calendar year. In 2017, this rate averaged 1.4 percent. In the September report, the administration estimated interest costs will add roughly $1 billion to the $6 billion principal repayment, bringing the total loan repayment to $7 billion.

Repayment Costs to Be Allocated Across Funds. Under SB 84, each fund, including the General Fund, is to pay its proportionate share of the loan principal and interest. As an example, if a particular fund represents 5 percent of CalPERS’ state employer contributions each year, it would repay 5 percent of the loan over its lifetime. Senate Bill 84 also authorizes the General Fund to advance money on behalf of other state funds (for example, if those funds have issues making repayments), and later be reimbursed.

SB 84 Requires Tracking of Payments by Fund. In addition to requiring that DOF ensure each fund pays its share of the loan, SB 84 requires DOF to develop a tracking mechanism for these repayments and maintain records of payments made by each fund. Senate Bill 84 also requires DOF to make public some of these records. In particular, SB 84 states that DOF shall “include in the published fund condition statement of the applicable funds and accounts, the amount determined to be the share of the loan principal and interest due and payment from each fund for the fiscal year.”

General Fund’s Share of Loan Initially Calculated at About 60 Percent but Revised to Half. Senate Bill 84 gives DOF the authority to set the methodology for calculating the amount to be repaid by each fund. In its May proposal, the administration indicated that it expected the General Fund’s share of the total $7 billion loan repayment to be 61.5 percent ($4.4 billion), while all other funds (including federal funds) would repay the remaining 38.5 percent ($2.5 billion). In the September report, however, the administration indicated it had identified payroll data that more accurately reflects underlying pension costs paid by the General Fund and other funds. As a result, it revised the General Fund’s share of total repayments down to 49.1 percent ($3.4 billion) and the other funds’ share up to 50.9 percent ($3.6 billion).

General Fund Repayments to Vary With Available Proposition 2. Senate Bill 84 stated the Legislature’s intent to repay the General Fund’s share of the loan from Proposition 2 annual debt requirements. The 2017‑18 budget package made an initial General Fund repayment of $146 million from Proposition 2. In the September report, DOF indicated it plans for future General Fund repayments to vary depending on the availability of Proposition 2 funds.

Other Funds to Repay According to Set Schedule. Other funds (including federal funds) are to repay their shares using their own available resources beginning in 2018‑19. (The reason other funds did not begin repayments in 2017‑18 was to allow time for DOF to develop a system for allocating repayment costs across the other funds.) In the September report, DOF developed a set repayment schedule for other funds. As shown in Figure 2, relative to 2018‑19, repayment costs for other funds would nearly double by 2021‑22, triple by 2022‑23, and quadruple by 2023‑24. (The administration, however, has indicated that it could revisit this schedule in the future.)

Interest Costs Not Distributed According to Different Repayment Schedules. Though the administration sets different repayment schedules for the General Fund versus other state funds, it does not allocate interest costs accordingly. Thus, under the administration’s approach, if the General Fund ends up paying faster than anticipated, the interest savings are distributed across all funds rather than just to the General Fund. (This is contrary to SB 84’s provision that each fund pay its proportionate share of the interest costs.)

Governor’s Repayment Plan for 2018‑19

Repays $475 Million From the General Fund. For 2018‑19, the administration proposes the General Fund repay $475 million from Proposition 2 debt requirements. This is the amount of Proposition 2 funds available given other commitments and priorities (such as prefunding retiree health benefits). This amount is nearly $300 million more than anticipated in June 2017. (This is mostly due to higher estimated Proposition 2 requirements and lower costs of one other debt repaid within Proposition 2.) The proposed amount for repayment is likely to change again in May when the administration updates its estimate of overall Proposition 2 debt requirements.

Repays $200 Million From Other State Funds. The administration also plans $200 million in repayments from other funds (excluding federal funds) in 2018‑19. This amount is based on the repayment plan outlined in the September report. The $200 million is distributed among other state funds proportional to their pension costs, except as discussed below.

Relieves About 40 Funds From Making $8.5 Million in Repayments in 2018‑19. The administration relieves about 40 funds (10 percent of state funds) from making part or, in most cases, all of their repayment on a one‑time basis in 2018‑19. (The administration has not made any commitments about these funds in future years.) Altogether, we estimate the relieved loan repayment costs to total about $8.5 million. As described below, these costs are shifted to other funds in 2018‑19 so that overall repayments from all other state funds remain at the planned level of $200 million. The administration cites various reasons for relieving these repayments, including:

- Structural Deficits. Some funds have ongoing expenditures exceeding their available revenues, creating a structural deficit. As Figure 3 shows, according to DOF, 18 funds have such a deficit and thus are unable to absorb their share of the loan repayment costs (totaling $5 million) in 2018‑19.

- Statutory Limits. Some funds, particularly bond funds, have limits on their administrative expenditures. Because the loan repayment costs would have caused a few funds to exceed their caps, DOF exempted these fund from repayments.

- Other Reasons. A dozen other state funds were exempt for various technical reasons. For instance, funds that function solely to pass through monies to another fund were exempt, as were a few funds that paid pension costs in the past but were recently abolished.

Figure 3

Loan Repayment Cost Shifts for Funds With Structural Deficits

(In Thousands)

|

Fund With Structural Deficit . . . |

Costs Shifted to . . . |

Amount |

|

State Parks and Recreation Fund |

All Other State Funds |

$2,255 |

|

Waste Discharge Permit Fund |

Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund |

1,094 |

|

Public Safety Communications Revolving Fund |

All Other State Funds |

709 |

|

DNA Identification Fund |

Fingerprint Fees Account |

476 |

|

Collins‑Dugan California Conservation Corps Reimbursement Account |

All Other State Funds |

166 |

|

Drug and Device Safety Fund |

Radiation Control Fund |

85 |

|

State Trial Court Improvement and Modernization Fund |

Trial Court Trust Fund |

70 |

|

State Certified Unified Program Agency Account |

Lead‑Acid Battery Cleanup Fund |

24 |

|

Timber Tax Fund |

All Other State Funds |

20 |

|

California Fire and Arson Training Fund |

All Other State Funds |

17 |

|

Driving‑Under‑the‑Influence Program Licensing Trust Fund |

Hospital Quality Assurance Revenue Fund |

17 |

|

Victim ‑ Witness Assistance Fund |

State Penalty Fund |

8 |

|

Sale of Tobacco to Minors Control Account |

Radiation Control Fund |

6 |

|

Registered Environmental Health Specialist Fund |

Radiation Control Fund |

5 |

|

Medical Marijuana Program Fund |

Health Statistics Special Fund |

5 |

|

Professional Forester Registration Fund |

All Other State Funds |

3 |

|

Sea Otter Fund, California |

All Other State Funds |

2 |

|

Winter Recreation Fund |

All Other State Funds |

1 |

|

Totals |

$4,965 |

Shifts the Associated $8.5 Million in Costs to Other Funds in Two Ways. For those funds relieved from making part or all of their repayment in 2018‑19, the administration shifts the costs to other funds using a two‑step approach:

- Shifts Some Repayment Costs to Funds Within the Same Department. The administration indicates that—when possible—it shifted costs between funds that have the same administering department. For example, DOF shifted about $1 million in costs from the Waste Discharge Permit Fund to the Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund. Both of these funds are operated by the State Water Resources Control Board. We estimate about $4.4 million in loan repayment costs from 25 funds were shifted in this manner.

- Shifts Some Repayment Costs to All Other Funds. In cases where repayment costs could not be shifted to another fund administered by the same department, the administration distributed the costs evenly to all other funds. We estimate about $4.2 million in loan repayment costs from 17 funds were shifted in this manner. The largest of these cost shifts, from the State Parks Recreation Fund, was $2.3 million.

Based on our own evaluation of information provided by the administration, we estimate that these shifts resulted in more than 100 funds having their loan repayment amount increased by more than 3 percent and 11 funds having their repayment amount increased by 50 percent or more. The administration has indicated to us that they plan to use this process again in future years to cover the costs of funds that are unable to pay.

Tracks These Shifted Costs Internally. The administration is tracking the cost shifts internally, not through publicly accessible budget documents. Thus, the fund condition statements produced by DOF in 2018‑19 reflect a fund’s total repayment, inclusive of any shifts from other funds, with no designation about those shifts. Funds that owe repayments but have shifted their costs to other funds have no indication of these shifts either.

Sets Up Alternative Payment Schedule for One Fund. The administration uses the set repayment schedule for other state funds outlined in the September report, with one exception: the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA). A fund with significant state operations costs, the MVA owes one of the largest shares of the loan repayment. The administration changes the repayment schedule for this fund in two ways. First, it extends the repayment schedule out to 2029‑30 (rather than 2024‑25). Second, it slightly increases the scheduled repayments in the first year. The administration states that, together, these changes avoid steep ramp ups in costs in the next few years. It also indicates that it took this approach at the request of the fund’s administrator, the Department of Motor Vehicles. (Under the administration’s approach, the higher interest costs that result from this modification accrue to all funds, not just the MVA.)

Excludes All Federal Fund Repayments. The Governor’s 2018‑19 repayment plan notably excludes all repayments from federal funds—totaling $24 million under the administration’s method. (Other funds do not cover these costs in 2018‑19.) This is because federal rules may not allow the state to use federal funds for these purposes—however, the administration is requesting approval from a federal negotiator to do so. In the box below, we discuss some of the fiscal implications regarding the uncertainty over whether the state can use federal funds to repay the loan.

Uncertainty Over Using Federal Funds to Repay the Loan

Federal Government May Not Allow the State to Use Federal Funds to Repay the Loan. Most federal funding to California, for various purposes from health to transportation, are deposited into a single account: the Federal Trust Fund. It is not yet clear whether the federal government will allow monies from the Federal Trust Fund to be directly expended on the loan repayments. This is because the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) loan repayments are not part of the CalPERS’ “actuarially required contribution,” and so federal rules may not allow the state to use federal funds for these purposes. The administration is requesting approval from a federal negotiator to do so. Under the administration’s current methodology, we estimate that the Federal Trust Fund and other smaller federal funds will owe nearly $400 million in repayments over the lifetime of the loan.

Federal Decision Could Have Different Fiscal Implications. In some cases, a decision by the federal government in either direction will not affect the amount of federal funding provided to the state. For example, some federal grants are provided in a lump sum and would not change even if the federal government disallowed the state from spending federal monies on the loan repayment. (In these situations, the state would have to redirect other funds to cover these costs but could use the freed up federal funding for other allowable purposes.) There could be other cases, however, where the state receives federal funding based on its costs, including those for personnel. In these cases, the state could receive more or less federal funding depending on whether the loan repayment is deemed an allowable personnel cost. (In these situations, if these costs are not allowed, the state would bear the loan repayment cost.)

Administration Has Not Yet Considered How to Cover Costs. The administration’s 2018‑19 repayment plan does not address these federal costs at this time, while the state waits for a decision from the federal government. If the federal government rejects the state’s request, then the administration indicates it would consider options for covering the loan repayment costs associated with federal funds. It could take different approaches for different programs funded through the Federal Trust Fund. For example, in some cases, the administration might want to use General Fund resources, but in others, it might shift the costs to other state funds where a sufficient nexus exists.

Assessment

In this section, we assess the administration’s repayment approach. While we think some aspects of the administration’s plan are reasonable, we have serious concerns that certain elements are not consistent with the requirements the Legislature established in SB 84. Accordingly, we also recommend a modified approach that comports with the legislation.

Basic Elements of the Plan Reasonable

Below, we describe why we think the basic elements of the administration’s plan are reasonable.

Method for Identifying Costs by Fund. As noted earlier, in the September report the administration revised its methodology for identifying pension costs by fund in order to calculate each fund’s share of loan. This changed the General Fund’s share of the overall loan from 61 percent to 49 percent (and shifted approximately $1 billion in costs from the General Fund to other state and federal funds). However, we think the new methodology is reasonable overall and better reflects underlying pension costs than the administration’s method in May 2017.

Priority Placed on CalPERS Loan Within Proposition 2. In 2018‑19, the administration places a high priority on repaying the CalPERS loan by using about a third of the Proposition 2 debt requirement for this purpose. In the past, our office has recommended the Legislature prioritize high‑interest debts within Proposition 2. While the interest accruing on the CalPERS loan repayments is low by most standards, it is actually somewhat higher than most other current Proposition 2 debt priorities. Moreover, because the interest rate on the CalPERS loan is tied to the two‑year Treasury rate, it will likely rise in coming years. As long as the Legislature continues to maintain its current uses of Proposition 2, we think it should place a high priority on repaying the CalPERS loan.

Overall Special Fund Repayment Structure. Under the administration’s schedule, other state funds’ repayments will ramp up significantly over the next few years. Also, as we noted earlier, funds will not experience most of the full benefit of the loan, in terms of slower growth in employer contributions, until the early to mid‑2020s. As such, this might create a situation where, in the short run, the costs of the loan are higher than the benefits, potentially placing pressure on a fund’s finances. We therefore concur with the administration’s approach of setting a base repayment schedule for funds that increases over time.

Some Features Raise Serious Concerns

There are some specific choices in the administration’s loan repayment approach that raise serious concerns. Most notably, some elements of the plan are inconsistent with directions given in statute. For example, the plan shifts costs between funds without any public acknowledgement of these cost shifts. We describe these issues in more detail below. (In general, it is our understanding that the administration has made these choices to improve the administrative ease of making the loan repayments.)

Lack of More Fund‑Specific Repayment Schedules. For all funds except one (the MVA), the administration imposes the set repayment schedule in 2018‑19. Funds other than the MVA, however, might also benefit from a different repayment schedule, depending on their specific fiscal and programmatic conditions. Our understanding is that other fund administrators concerned about the costs in 2018‑19, however, simply requested to be relieved from the costs, rather than considering ways to spread the costs out over time to make them more manageable. (Fund administrators may not have been aware they could request alternative repayment schedules, as our discussion with departments revealed that some fund administrators were unaware of the future costs, or even the upcoming year’s costs, associated with the loan.)

Cost Shifts Across Funds. The administration’s decision to shift $8.5 million in costs among other state funds raises both policy and legal concerns because a sufficient nexus between the funds does not appear to exist in many cases. Most notably, in cases where costs are shifted from one fund to all other funds, a nexus almost certainly does not exist between all the funds involved. A nexus might also be lacking in cases where costs are shifted from one fund to another fund administered by the same department. For instance, as discussed earlier, the administration shifts costs between two funds administered by the State Water Resources Control Board. Yet these two funds serve different purposes and have entirely different fee payers.

Cost Shifts Are Not Tracked Publicly. Despite SB 84’s directive that DOF publish in fund condition statements the amount determined to be the cost of the loan that is due and payable, the administration only publishes the total amount of repayments, which in some cases is more or less than a fund’s proportional share. As such, the administration’s approach lacks transparency because the shifts are only being tracked internally and not through publicly accessible budget documents. As described in the box below, in a recent report to the Legislature, the administration also failed to acknowledge these fund shifts.

Recent Report From the Administration

Legislature Requested Additional Information on Funds With Issues Repaying. In addition to the September report required by statute, the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) requested two further reports from the administration with additional information on the borrowing plan. These reports were due one month before the final two $2 billion transfers were scheduled (in January and April 2018, respectively). In its request for information, the JLBC asked for a “projection of special fund costs and list of special funds that would potentially have problems repaying the loan as scheduled.”

Department of Finance (DOF) Responded That All Funds Have Sufficient Balances to Pay Assessments. The JLBC received the second of these reports from the administration on March 16, 2018. This report states: “we anticipate all funds to have sufficient balances to pay their assessments.” However, as we note in this report, about 40 funds are not making repayments in 2018‑19 under the administration’s own schedule. Of these, 18 are not making repayments because they face structural deficits. (Representatives of the administration note they are interpreting the JLBC’s question to mean a list of funds that face issues with cash flow problems, not budgetary problems. There is no mention of this interpretation in the report to the JLBC.)

DOF’s Statements Obscure Cost Shifts Across Funds. As noted in this report, DOF’s cost shifts involve no public tracking system that would allow members of the Legislature or the public to compare a fund’s assessments to the amount paid. DOF provides no additional context or explanation about these cost shifts in its public budget documents. As a result, without additional information, its March 2018 report would likely have given members of the Legislature the false impression that all funds are repaying their assessments in 2018‑19.

Interest Cost Allocations. Senate Bill 84 directs the administration to ensure that all funds pay their proportionate shares of the principal and interest of the loan. The administration, however, has decided not to allocate interest costs by fund. This results in an implicit shifting of costs among funds. For instance, the General Fund is repaying nearly $300 million more in 2018‑19 than anticipated in June 2017. All else equal, this could reduce interest costs to the General Fund by about $50 million over the lifetime of the loan. (Any future shifts that accelerate General Fund payments could result in tens of millions of dollars, or over a hundred million dollars, more in General Fund savings.) Yet, under the administration’s approach and despite direction in SB 84, these savings are distributed to all funds, not just the General Fund. Conversely, by extending its repayment period, the MVA is increasing interest costs on the loan repayment, yet these costs are distributed across all funds instead of being attributed solely to the MVA.

Issues This Year Have Larger Out‑Year Implications. If the administration maintains its approach in future years, the issues described above will be exacerbated as the costs of repaying the loan double, triple, and quadruple. In particular, the costs shifted between funds likely will increase as funds face larger repayment costs. Also, as the repayment costs increase, more funds are likely to face difficulty with repayment, resulting in even more shifts. As such, the administration’s approach could lead to tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in principal and interest costs being distributed inappropriately across funds.

Recommended Approach

Overview of the Recommended Approach. In this section, we recommend an approach to repaying the loan that would modify the administration’s plan. This recommended approach: (1) is consistent with statute, (2) allocates costs appropriately and publicly, and (3) provides incentives to create more cost‑effective outcomes. Below, we describe each feature of the recommended alternative in more detail.

Customize Repayment Schedules as Needed. Under our alternative, DOF would first communicate the set repayment schedule with each fund administrator and then direct the administrator to analyze the effects of the loan repayment on the fund over the coming years. (For small funds this analysis could be very straightforward, but for larger funds, more complex.) The fund administrator could then request (and justify) a customized repayment schedule. For example, fund administrators could request an extended repayment period, as was done by the Department of Motor Vehicles for the MVA. Funds facing better budgetary conditions may prefer to pay more sooner, avoiding a steep ramp up in costs, while those with structural imbalances may choose to repay more later.

Use Loans Rather Than Cost Shifts. For some funds, a longer repayment schedule alone may not be sufficient to help them manage their loan repayments. In these cases, DOF could use loans from the General Fund (or possibly other funds) to cover the repayment costs. These loans would be repaid with interest and tracked in publicly accessible state budget documents, including fund condition statements. (For funds facing severe fiscal constraints where a loan might not be feasible, the state could consider using the General Fund to make the repayment on the fund’s behalf.) This would ensure the state is following the directives under SB 84.

Track Interest Costs by Fund. Under our alternative, interest costs would be tracked for each fund based on its own repayment schedule. In addition to fulfilling legislative requirements, this approach has a couple of advantages. First, it attributes the costs of the loan by fund more accurately. (In particular, it would ensure the General Fund benefits from lower interest costs if it repays its share of the loan more quickly than other funds.) Second, it creates a strong incentive for funds that have the ability to repay more quickly to do so. This would lower the state’s overall costs associated with the loan.