Related Content

LAO Contacts

Rachel Ehlers (Water)

Ashley Ames (Forestry)

April 4, 2018

Improving California’s

Forest and Watershed Management

- Introduction

- Why Forests Matter

- Forest Management

- Current Forest Conditions

- Findings

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Forests Provide Critical Statewide Benefits, but Poor Conditions Put Those Benefits at Risk. Roughly one‑third of California is forested, including the majority of the watersheds that serve as the key originating water source for millions of people across the state. These forests also provide critical air, wildlife, climate, and recreational benefits. However, a combination of factors have resulted in poor conditions across these forests and watersheds, including excessive vegetation density and an overabundance of small trees and brush. Such conditions have contributed to more prevalent and severe wildfires and unprecedented tree mortality in recent years, and experts are concerned these trends will continue if steps are not taken to significantly improve the health of the state’s forests.

Recommendations. While broad consensus exists about both the problematic conditions of the state’s forests and the types of activities needed to address them, the pace of making the needed improvements is slow. Moreover, the scale of the improvement projects that are currently taking place is relatively small compared to the identified need. We make various recommendations to improve the health of the state’s forested watersheds. These recommendations encompass both larger actions as well as some more moderate steps that we believe could help achieve improved outcomes.

✓ Improve and Increase Funding and Coordination.

- Recognize the statewide benefits that healthy forests can provide by maintaining at least the current level of funding—$280 million annually—for projects to improve forest health.

- Take steps to generate additional investments from downstream beneficiaries by (1) requiring the State Water Project to make an annual spending contribution to maintain the health of the Feather River watershed, (2) appropriating $2 million for pilot projects for local water and hydropower agencies to conduct wildfire cost‑avoidance and cost‑benefit studies, and (3) modifying grant criteria for the Integrated Regional Water Management program to encourage spending on watershed health projects.

- Designate the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA)—rather than the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire)—as the lead agency to oversee proactive forest and watershed health funding and initiatives.

- Ensure that future spending is based on clear prioritization criteria that targets funds to maximize statewide benefits—such as reducing fire risk, protecting water supplies, and sequestering greenhouse gas emissions—in particular by promoting larger projects.

✓ Revise Certain State Policies and Practices to Facilitate Forest Health Activities.

- Allow the sale of timber without a timber management plan in specific cases when the primary purpose of the project is forest health in order to help offset the costs of beneficial forest thinning projects.

- Direct CNRA to submit a report proposing options for how the state might streamline forest health project permitting requirements.

✓ Improve Landowner Assistance Programs to Increase Effectiveness.

- Allocate funding to CalFire for additional forester positions to increase the department’s use of prescribed fire through its Vegetation Management Program.

- Restructure California Forest Improvement Program payments to reduce the burden on small landowners by providing partial payments in advance of work being undertaken.

✓ Expand Options for Utilizing and Disposing of Woody Biomass.

- Support the development and incentivize the use of nontraditional wood products by appropriating funding for a pilot grant program.

- Increase opportunities for disposing of biomass by (1) requiring CalFire and the California Air Resources Board to analyze when burn permit requirements could be eased and (2) appropriating funding to purchase additional air curtain burners based on an analysis by CalFire.

Introduction

Roughly one‑third of California is forested, including the majority of the watersheds that serve as the key originating water source for millions of people across the state. These forests also provide critical air, wildlife, climate, and recreational benefits. However, a combination of factors have resulted in poor conditions across these forests and watersheds, including excessive vegetation density and an overabundance of small trees and brush. Such conditions have contributed to more prevalent and severe wildfires and unprecedented tree mortality in recent years, and experts are concerned these trends will continue if steps are not taken to significantly improve the health of the state’s forests.

This report consists of five sections. First, we review the importance of and benefits provided by California’s forests. Second, we provide information regarding how forests are managed in California, including ownership, state and federal policies and programs, and funding. Third, we review the current conditions of forests and watersheds across the state, including the concerning implications and recent consequences of those conditions, as well as the actions that would be needed to make improvements. Fourth, in the findings section, we highlight shortcomings in how the state manages its forests and watersheds. Fifth, we offer recommendations for actions the Legislature could take to improve forest and watershed management in California.

Why Forests Matter

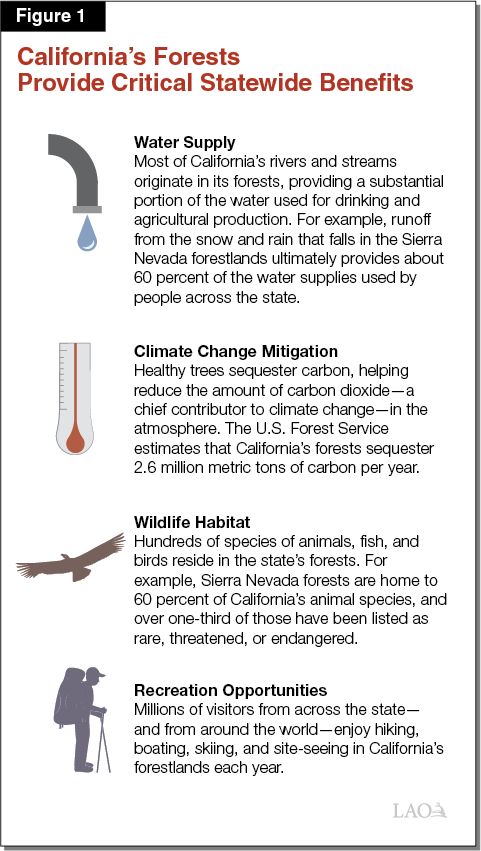

Forests Provide Critical Statewide Benefits. Forests cover about one‑third of the state’s land area, containing over 4 billion live trees. (Land is considered forested if at least 10 percent of it is covered by tree canopy, or if it formerly had such tree cover and has not yet been formally developed for other uses.) While only a small percentage of the state’s population lives in forested areas, forests affect the lives of residents across the state. Figure 1 summarizes the specific statewide benefits provided by forests. Among the most important benefits is the role forests play in collecting and storing the snowpack that most Californians depend on for water. Additionally, by storing carbon, the state’s forests also play a vital part in helping the state to combat climate change and to meet its ambitious goals for reducing greenhouse gases (GHGs). The forest ecosystems and the diverse terrestrial, aquatic, and plant species that live in them represent a public resource belonging to and entrusted to all Californians. Forestlands also provide a variety of recreational opportunities, including in areas preserved, owned, and managed by public agencies for broad public access.

Most of State’s Key Watersheds Are Located in Forestlands. In a typical year, the majority of California’s total annual precipitation—in the form of rain and snow—falls in the mostly forested Sierra Nevada and southern Cascade mountain ranges. The rivers and streams flowing from these key “source watersheds” provide the crucial surface water that a majority of Californians use for drinking and most of the state’s agricultural sector uses for growing crops. Some estimates suggest that rain and snow that start in Sierra Nevada forests contribute around 60 percent of the state’s developed water supply (water that is captured in reservoirs and distributed to users across the state). Forested watersheds in other areas of the state are also key for local water supplies. For example, the San Bernardino and Cleveland National Forests receive 90 percent of the annual precipitation for the Santa Ana River watershed, from which runoff contributes to the water supplies for 6 million people in Orange, San Bernardino, and Riverside Counties.

By storing snow through the winter wet season then releasing it as melted runoff into streams and rivers through the spring and early summer, these forests provide a natural water infrastructure upon which the state has long depended. In a typical winter, mountain snowpack is a “natural reservoir” that ultimately provides one‑third of the water supplies the state’s cities and farms will use throughout the rest of the year. Forests—including the mountain meadows located within forestlands—also protect water quality by reducing erosion of sediments into streams and by filtering out pollutants from runoff.

Changing Climate Increases Importance of State’s Forests. Predictions for how climate change will affect California in the coming decades magnify the importance of the statewide value that forests can provide. For example, scientists predict that in future years, a greater share of the state’s annual precipitation will come as rain rather than as snow, and that warmer temperatures will cause snow to melt into runoff earlier in the season compared to historical trends. Downstream reservoirs, however, do not have the capacity to take on the winter water storage role that mountain snowpack has traditionally provided. This increases the importance of efforts to preserve the ability of the state’s forests to capture—and maintain at higher elevations, for as long as possible—the snowpack that the state does continue to receive in mountain forests and meadows. Preserving and potentially increasing the role that forests play in sequestering carbon and constraining GHG emissions are also becoming important components in the state’s efforts to slow the effects of climate change. Additionally, warming temperatures and the potential for more frequent and severe droughts may cause some areas in lower elevations to become too dry to support the current species of trees, converting those forests to shrublands. This potential loss of lower elevation forestlands magnifies the importance of preserving the remaining, higher elevation forests.

Forest Management

How Forests Are Owned, Used, and Managed in California

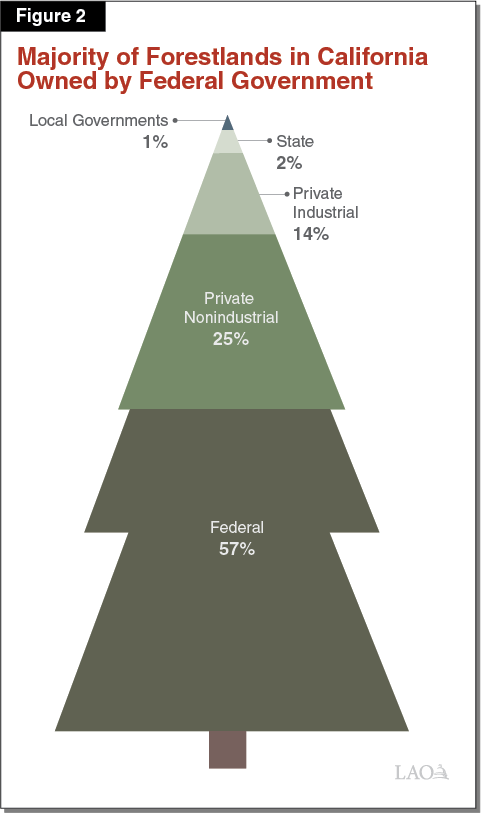

33 Million Acres of Forestland in California Owned by Combination of Entities. As shown in Figure 2, close to 60 percent (nearly 19 million acres) of forestlands in California are owned by the federal government, including by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and National Park Service. Private nonindustrial entities own about one‑quarter (8 million acres) acres of forestland. These include families, individuals, conservation and natural resource organizations, and Native American tribes. Industrial owners—primarily timber companies—own 14 percent (4.5 million acres) of forestland. State and local governments own a comparatively small share—only 3 percent (1 million acres) combined.

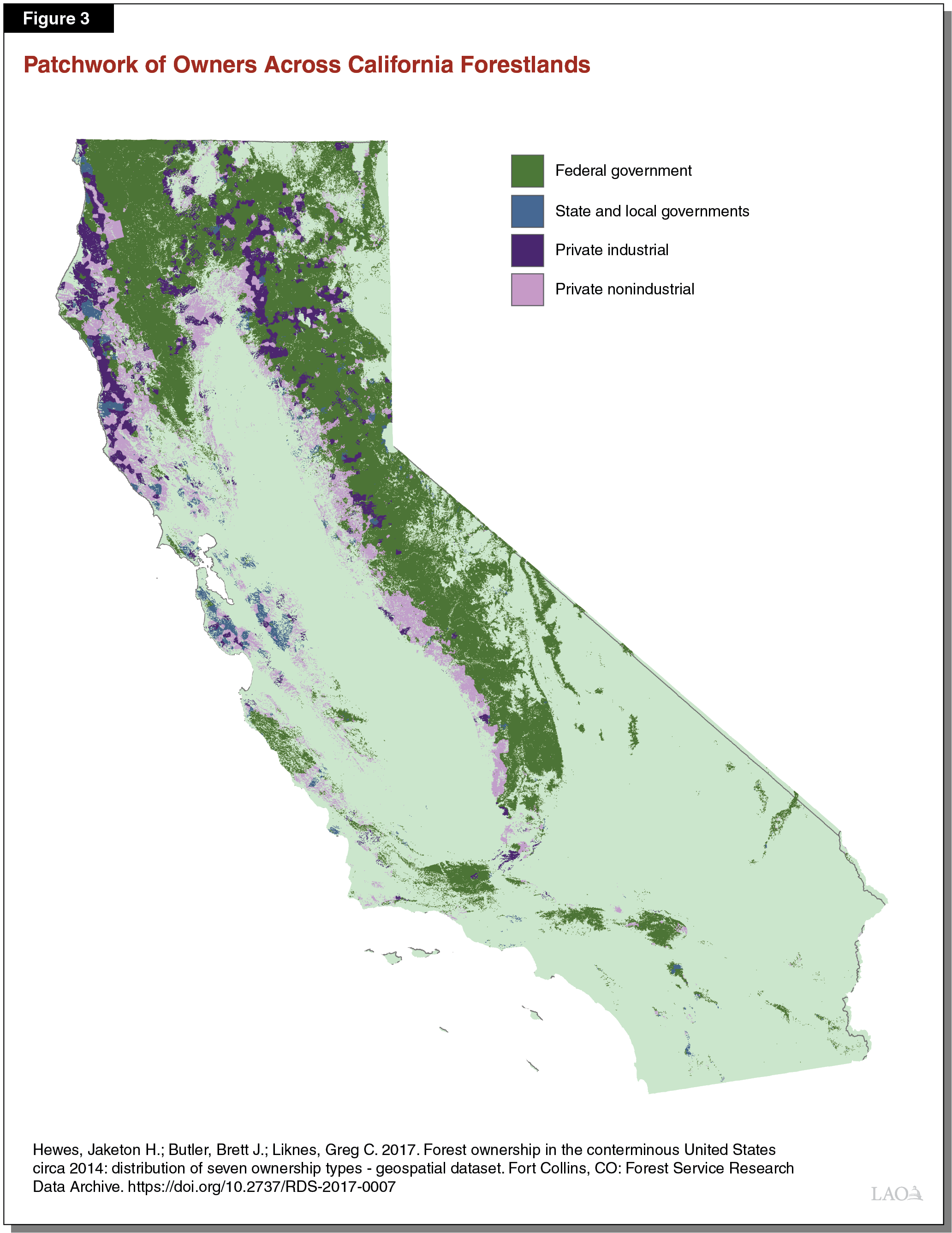

Figure 3 displays these forest ownership patterns across the state. In some areas, neighboring parcels are owned by a patchwork of different owners. In other areas of the state, a single owner—typically a federal agency—owns a large swath of contiguous land.

Though Private Forestlands Often Used for Timber, Harvesting Has Declined Over Time. As indicated earlier, 39 percent of forestlands across the state are under private ownership—both nonindustrial and industrial. Nonindustrial forest owners are those that typically have less than 5,000 acres of forestland and do not own a processing mill. The majority of these private owners hold parcels smaller than 50 acres and do not typically engage in selling timber. In contrast, private industrial interests own forestlands for the purpose of growing, harvesting, and selling timber. Private lands have provided the majority of California’s timber since the 1940s.

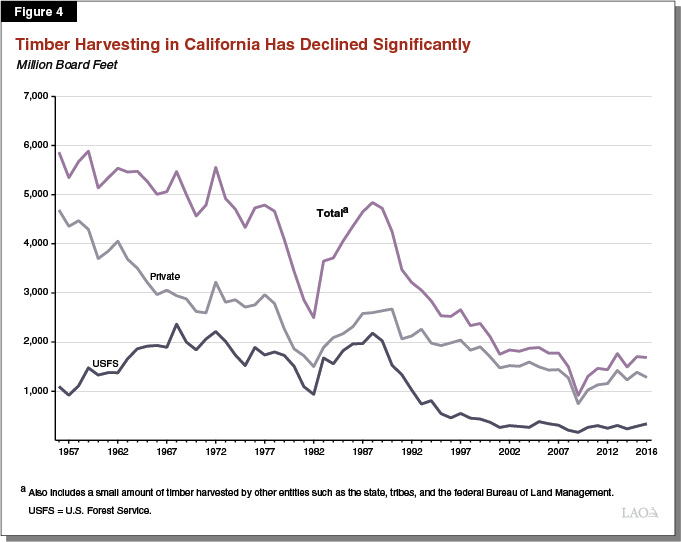

Figure 4 shows the amount of timber harvested in California on both private and public lands over the past 60 years. While subject to annual variation, total timber harvesting in California has declined by over two‑thirds since the late 1950s. As shown in the figure, harvest rates have dropped from over 4.8 billion board feet in 1988—its recent peak—to about 900 million in 2009, when it was at its lowest in recent history—a decline of over 80 percent.

These trends are due to a variety of factors, including changes in state and federal timber harvesting policies. For example, several federal laws were passed in the 1970s that shifted the USFS’s forest management objectives away from production forestry and more toward conservation and ecosystem management. Those laws included the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—which requires federal agencies to evaluate any actions that could have a significant effect on the environment—and the Endangered Species Act—which prohibits federal agencies from carrying out actions that might adversely affect a species listed as threatened or endangered. Environmental protection policies have also contributed to declines in private harvests, along with other factors. More recently, the economic recession in the late 2000s sharply reduced demand for new housing construction, thereby also suppressing demand for timber. Since 2009, timber harvesting rates have picked up somewhat, but have not returned to earlier levels.

Forest Management Involves Proactive Activities. “Forest management” is generally defined as the process of planning and implementing practices for the stewardship and use of forests to meet specific environmental, economic, social, and cultural objectives. Activities forest managers employ include timber harvesting (typically for commercial purposes), vegetation thinning (clearing out small trees and brush, often through mechanical means or prescribed burns), and reforestation (planting new trees). Figure 5 describes specific activities that managers typically undertake to improve the health of forests. As discussed later, research has shown that these are the types of activities that are most effective at preserving and restoring the natural functions and processes of forests, and thereby maximizing the natural benefits that they can provide. Efforts to extinguish active wildfires are not generally considered to be forest management activities, as they are more responsive than proactive.

Many Management Activities Result in Need to Remove Lumber and Woody Biomass. Forest management activities often involve the removal of trees or brush, whether for commercial or noncommercial purposes. The primary product of commercial timber operations is lumber that can be sold for revenue. In addition, both commercial and noncommercial timber management activities such as mechanical thinning typically require utilization or disposal of “woody biomass” that is often not of a size or quality to be used in lumber production at traditional sawmills. This includes limbs, tops, needles, leaves, and other woody parts. In some cases, woody biomass can be used to produce other products, although processing complications and limited demand can complicate these efforts, as we discuss later. Excess forest material that is not utilized as lumber or some other product is often either burned or left to decompose in the forest. Because leaving the material can create a fire hazard, woody biomass waste is most commonly disposed of using open pile burning—accumulating vegetation left by forest management activities into manageable piles that are subsequently burned.

Multiple Entities Involved in Forest Management. The mix of forest ownership across the state means that a number of different entities are involved in managing forestland. Figure 6 identifies the federal and state agencies with major forest management responsibilities in California. As shown in the figure, within the federal government this includes the three agencies with the largest forestland holdings in the state. For the state, the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) is the lead agency tasked with helping to manage nonfederal forestlands and forest health initiatives, although the other agencies also have some significant responsibilities.

Figure 6

Major State and Federal Agencies Involved in Forest Management

|

Agency |

Primary Responsibilities |

|

Federal |

|

|

U.S. Forest Service |

Owns and manages about 15.5 million acres of forestland in California, including 18 National Forests. Oversees activities related to resource development (including timber harvesting, grazing, and energy production), land conservation (including preserving designated wilderness areas), and recreation. Manages and suppresses wildfires on federal lands. Conducts forestry research. |

|

Bureau of Land Management |

Owns and manages about 1.6 million acres of forestland in California, including overseeing activities related to resource development, land conservation, and recreation. |

|

National Park Service |

Owns and manages about 1.4 million acres of forestland in California, including preserving natural and cultural resources and facilitating public access. |

|

State |

|

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) |

Prevents and suppresses fire on wildlands within “State Responsibility Areas” (which includes over 31 million acres of private and state‑owned forestland). Oversees enforcement of state timber harvesting policies on private lands. Manages 71,000 acres of state research forests and conducts forestry research. |

|

Board of Forestry and Fire Protection |

Serves as regulatory arm of CalFire. Develops state’s forest policies and regulations. |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

Oversees the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Program, including coordinating multi‑department reviews of Timber Harvest Plans and developing performance measures for how timber harvest policies are attaining the state’s ecological goals. |

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy |

Allocates state grants for local forest projects in the Sierra Nevada region. Leads collaborative Watershed Improvement Program to restore forests and watersheds in the region. |

Besides those agencies identified in the figure, certain other federal and state agencies are also involved in forest management activities, though typically to a lesser degree. For example, several regulatory agencies review and approve activities on forestlands through their permitting authority. These include the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW), the California Air Resources Board (CARB), and the state’s Regional Water Quality Review Boards. We also note that the Wildlife Conservation Board allocates state funding to protect, restore, and improve forestlands, and the California Conservation Corps undertakes conservation projects to improve forest health, including fuel reduction and planting trees. Additionally, in response to a recent outbreak of severe tree mortality across the state’s forests, the Governor issued an executive order that established a Tree Mortality Task Force comprised of state and federal agencies, local governments, utilities, and various stakeholders to coordinate emergency actions.

In addition to the federal and state governments, other entities that implement and influence forest management activities include local governments such as cities, counties, and special districts (like water agencies, resource conservation districts, and air districts). Landowners, funders of conservation projects, and concerned stakeholders are also involved in forest management decisions and in implementing forest projects. These can include local residents, Native American tribes, nongovernmental organizations, private timber companies, and electric utilities.

State Holds Some Management Responsibilities Over Privately Owned Forests. Although the state owns only a small share of forestlands, state law tasks CalFire with certain responsibilities on privately owned lands. Specifically, CalFire’s historic mission has been two‑fold: (1) the protection of commercial timber on all nonfederal lands from improper logging activities and (2) the protection of watersheds from wildland fire in lands identified as part of the “State Responsibility Area” (SRA). The SRA includes about 13.2 million acres of forestland across the state—most of the forest not owned by federal agencies. CalFire’s SRA responsibilities include (1) enforcing fire prevention measures such as checking that homes have the required “defensible space” clear of brush, (2) fire suppression and other emergency response activities, and (3) providing financial and technical forest management assistance to private landowners. Additionally, CalFire regulates timber harvest activities on both industrial and nonindustrial private lands by enforcing the state’s Forest Practice Rules and reviewing the timber harvest and forest management plans that we discuss later. The department also leads the state’s efforts to improve and maintain the health of forestlands in California, including by administering grant programs.

Partnerships Enable Entities to Work Across Ownership Boundaries. While forest management responsibilities typically align with ownership, natural processes—such as forest fires, water runoff, and wildlife habitats—do not observe those jurisdictional boundaries. As such, federal and state agencies have developed certain arrangements to collaborate on management activities across California’s forests. For example, federal law has a provision—known as the “Good Neighbor Authority”—that allows states to fund and implement forest health projects on federally owned land. As discussed later, the federal government also funds a number of grant programs to encourage collaborative projects on both federal and nonfederal forestlands. Additionally, federal and state agencies have established agreements for collaborative fire suppression efforts across jurisdictions when fires do occur.

State and Federal Forest Management Policies and Practices

Changing Emphasis on Fire Suppression Over Time. Well into the 19th century, suppression was not the standard response to wildfire in the rural, sparsely populated West. Naturally occurring fires typically burned their natural courses. However, as population density grew and forestlands were developed, wildfire began posing a greater risk to lives and property. When USFS was established in 1905, its primary task was to suppress all fires on the forest reserves it administered. By 1935, USFS fire management policy stipulated that all wildfires were to be suppressed by 10:00 in the morning after they were first spotted.

Similarly, the California Legislature first appropriated money for fire prevention and suppression work in 1919, and the Division of Forestry was created in 1927. Initially, the department provided rangers and lookout towers before fully taking on the responsibility to suppress fires in SRA in the 1940s. Currently, CalFire has the stated goal of containing 95 percent of all fires—excluding prescribed fires—at ten acres or less. These firefighting efforts have been highly successful, with the acreage burned by wildfires in California reduced from an estimated annual average of 4.5 million acres in the 1700s to about 1 million acres annually in more recent years. As forestlands have become more developed, firefighting resources have been increased to better protect homes and property, further reducing the number of acres burned annually.

USFS, however, has gradually shifted its policies back to allowing more fires to burn. The passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act encouraged allowing natural processes to occur, including fire. Accordingly, USFS has changed its policy from fire control to fire management, allowing fires to play their natural ecological roles as long as they can be contained safely based on weather patterns, terrain, proximity to development, and other factors. This policy includes both naturally caused fires and intentionally prescribed fires. This shift reflects a growing resurgence in the perspective that moderate fires can have beneficial effects on forestlands, such as clearing out smaller brush and stimulating natural processes like tree seed dispersal and replenishment of soil nutrients.

In contrast to USFS, CalFire has maintained its suppression goal, and generally still seeks to extinguish all naturally occurring fires. This is largely due to the nature of the areas the department is tasked with defending, which often are more developed than national forests.

State Forest Practice Rules Govern Timber Harvest on Privately Owned Forestlands. The state’s Z’Berg‑Nejedly Forest Practice Act of 1973 is the main California law that governs the management of California’s privately owned forestlands. The Forest Practice Act authorizes the state Board of Forestry and Fire Protection to develop regulations related to most commercial and noncommercial timber harvesting activities, known as the Forest Practice Rules (FPR). Under the FPR, landowners who wish to harvest and then sell their trees must submit and comply with an approved state‑issued timber harvesting permit.

The most common permit for the harvest and eventual sale of trees is a Timber Harvesting Plan (THP), which describes the scope, yield, harvesting methods, and mitigation measures that a timber harvester intends to perform within a specified geographical area over a period of five years. THPs are primarily utilized by larger industrial harvesters. The FPR also allow the use of other permits for harvesting and selling trees, such as a Nonindustrial Timber Management Plan (NTMP), which was added by the Legislature in 1991. NTMPs are intended to make it easier for small nonindustrial landowners—those who own less than 2,500 acres and are not primarily engaged in the manufacturing of forest products—to better manage their forests, including tree removal and sale of some relatively small amount of timber. NTMPs involve a longer‑term management plan better suited to the intended land uses than a THP. Additionally, the Working Forest Management Plan program—enacted through Chapter 648 of 2013 (AB 904, Chesbro)—allows for a long‑term forest management plan for nonindustrial landowners who wish to harvest and sell some of their trees and who own less than 15,000 acres of timberlands if the landowner commits to specific forest management practices. After a THP or other harvest management plan is prepared, staff from the state’s Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Program (TRFRP) review it for compliance with state regulations designed to ensure sustainable harvesting practices and minimize environmental harms. The TRFRP was created by Chapter 289 of 2012 (AB 1492, Committee on Budget). The California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) takes the lead role in conducting these reviews but gets assistance from CalFire, DFW, the Department of Conservation, and the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). CalFire is tasked with enforcing the FPR and ensuring landowners comply with approved permits by conducting site inspections. If landowners or timber operators are found to be out of compliance with FPR requirements, CalFire is authorized to issue citations, fine violators, or shut down harvesting operations. As we discuss below, there are circumstances in which a permit is not required, such as for specified emergencies.

Over time, the Legislature has made changes to the Forest Practice Act and Rules in order to address various concerns and encourage certain management practices. For example, in 2012 AB 1492 created the TRFRP within CNRA and levied a 1 percent lumber assessment to fund the program. It also directed CNRA to develop ecological performance measures to evaluate the cumulative impacts of management and harvesting activities on a larger scale and support more long‑term goals for minimizing the environmental impacts of such activities, which could inform further modifications to the FPR going forward. The Legislature and Board of Forestry have also made changes to the FPR to address the effects of drought and tree mortality, modernize rules for the building and maintenance of logging roads, take into account the state’s GHG emission‑reduction goals, and promote oak woodlands restoration.

State and Federal Environmental Laws Regulate Forest Management Activities. While forest owners are responsible for managing their own lands, state and federal regulatory agencies are statutorily required to ensure that those management activities do not result in excessively negative environmental impacts. For example, an operation to remove trees for either commercial harvest or to improve the health of the forest could impact habitats for sensitive wildlife or create sediment runoff into a nearby stream and degrade water quality. To prevent such negative impacts, entities seeking to undertake activities to improve forest health typically must first receive approvals from specified agencies entrusted with safeguarding water, air, and wildlife resources on behalf of the public.

As discussed above, landowners seeking to harvest timber must complete THPs, which include assessments of potential environmental impacts and mitigation requirements. Entities seeking to conduct other types of forest management projects on nonfederal lands and/or projects that are funded with state dollars typically must attain other types of environmental permits. The major permits typically required for forest management projects are summarized in Figure 7. Generally, the most significant and comprehensive reviews are the Environmental Impact Reports (EIRs) required by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). These reviews evaluate potential environmental impacts in a number of categories including biological resources, cultural resources, GHG emissions, and hydrology. Because THPs involve state department reviews of potential impacts on water quality and wildlife, traditional commercial timber harvesting projects covered by THPs typically do not require a CEQA review or additional state environmental permits.

Figure 7

Major State Environmental Permits Frequently Required for Forest Management Activities

|

Permit |

Administering Agency |

Description |

|

Timber Harvest Plan |

CalFire |

Required for landowners seeking to harvest timber for commercial sale. Must describe the scope, yield, harvesting methods, and mitigation measures planned over five‑year period. |

|

California Environmental Quality Act Environmental Impact Report (EIR) |

Typically the public agency that funds or manages the project |

Required for projects on nonfederal lands or using state funds that have the potential to cause physical change in the environment. Must evaluate, consider alternatives, and potentially mitigate for potential adverse environmental impacts in a number of categories. Can issue Negative Declaration instead of conducting full EIR if initial study finds no evidence of significant negative impacts. |

|

California Endangered Species Act Incidental Take Permit |

Fish and Wildlife |

Required for projects that have adverse effects on species the state has identified as needing special protections. Must include measures to avoid, minimize, and mitigate those effects. |

|

Lake and Streambed Alteration Agreement |

Fish and Wildlife |

Required for projects that will change the flow of or deposit debris into a stream, river, or lake. Must include measures necessary to protect fish and wildlife resources. |

|

Section 401 Water Quality Certification |

Regional Water Quality Control Boards |

Required for projects that impact waters, including wetlands, streams, rivers, or lakes. Must ensure proposed activity complies with all applicable water quality standards, limitations, and restrictions. |

|

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit |

Regional Water Quality Control Boards |

Required for projects with construction activities that will disturb more than one acre of land to address potential pollutants from storm water discharge or runoff. Must develop Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan. |

|

Burn Permit |

Air Resources Board (and local air districts) |

Required for prescribed burns. Must develop a Smoke Management Plan. Even with permit, can only burn under certain conditions. |

|

CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. |

||

Projects undertaken on federal lands typically require separate regulatory approvals from federal agencies. This frequently includes approval of an Environmental Impact Statement required by NEPA—which is similar to the state’s CEQA process—as well as federal permits to preserve water quality and wildlife species that have been identified as needing special protections. In general, state permits are not required for projects on federal lands unless they are being funded using state dollars.

Certain Forest Management Projects Can Qualify for Special Permits or Exemptions. Although many forest management projects on nonfederal lands require the types of permits described in Figure 7, certain types of projects qualify for more streamlined regulatory approvals. For example, some projects may be covered by “programmatic” EIRs for which CalFire has undertaken a large‑scale CEQA review. These programmatic EIRs analyze the potential impacts of a series of similar forest health activities—essentially treating them as one large, ongoing project and creating a broad permit that allows similar activities to be implemented over time without undertaking additional environmental reviews. For instance, CalFire has approved a programmatic EIR—known as a Program Timberland EIR—to cover a handful of similar projects on nonfederal forestlands in Northern California that combine wildfire reduction with timber harvest. The department is also in the process of developing a programmatic EIR for its Vegetation Management Program (VMP), which would allow it to undertake certain types of prescribed burning, thinning, and restoration projects on nonfederal lands across the state without needing to conduct a new CEQA EIR analysis each time.

Other agencies, such as Regional Water Quality Control Boards, also have developed some special initiatives to expedite the permitting processes for forest management projects in certain instances. For example, the North Coast regional board issued a programmatic permit authorizing limited discharges into waterbodies for landowners in Mendocino County who implement specified types of restoration and conservation projects that may result in some sediment runoff while the projects are being implemented. In addition, the Central Valley and Lahontan regional boards are working together to develop a programmatic permit to regulate “nonpoint source pollution” that would authorize certain activities on USFS and BLM lands, including specified types of timber harvesting and vegetation management projects. These programmatic permits replace the requirement that landowners attain project‑specific permits, but include oversight and monitoring to ensure agreed‑upon practices and mitigation are employed.

Additionally, the Legislature has instituted several statutory CEQA exemptions for particular forest management activities, meaning no CEQA review is required. These include removal of dead trees and removal of invasive species.

Forest Carbon Plan Provides Framework for Management to Increase Sequestration and Minimize GHG Emissions. The state has undertaken a multifaceted effort to reduce GHG emissions and sequester carbon. This includes the cap‑and‑trade program, which involves the auctioning of permits that allow businesses to emit GHGs, with the resulting revenue deposited in the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). Another component of the state’s GHG reduction strategy is the state’s Forest Carbon Plan, which will serve as a blueprint for how the state can manage forests in order for them to reduce GHGs. It is being prepared by CalFire, CNRA, and CARB, with a draft version published in 2017 and a final version expected in 2018. The plan examines California’s various forestry needs and available treatment activities with the goal of increasing GHG sequestration by improving forest health and reducing GHG emissions by minimizing wildfire severity. It also examines strategies to prevent forestland conversions and innovate opportunities for wood products and biomass utilization.

State Programs and Funding for Forest Management

Estimates Suggest Current Spending for Forest Health Is Treating About 280,000 Acres Per Year. Estimates of the level of current forest health activities being undertaken across the state vary, particularly because a large proportion of forests are owned and managed by private entities. USFS has a stated goal of implementing fuel reduction treatments on 500,000 acres of its lands in California each year; however, the need to internally redirect resources from restoration to fire suppression has resulted in a lower rate of restoration. Instead, USFS has treated an average of about 250,000 acres per year in recent years. Specifically, in 2017 USFS treated 140,000 acres through thinning and prescribed fire and an additional 110,000 acres through managed natural fires. According to the draft Forest Carbon Plan, BLM treats about 9,000 acres of its forestlands annually. The plan also states that CalFire treats about 17,500 acres of SRA land per year through its VMP, which is discussed in greater detail below. Estimates are not readily available for how many acres of forestlands private landowners treat on their own each year. A recent report by the Public Policy Institute of California estimates that ongoing federal and state funding for proactive forest management in California has averaged around $100 million annually in recent years. In this section, we describe how these funds have been spent.

State Funds Several Programs to Promote Forest Health. The state funds programs in several different state departments that are intended to encourage activities that support California’s forests, including to reduce wildfire risk. Many of these programs are designed to assist private landowners in effectively managing their lands, given they own a significant portion of the state’s forests. Figure 8 summarizes the state’s major forest management programs and the funding that was provided in 2017‑18. As shown, as the state’s lead entity for addressing forest health, CalFire administers most of these programs. We discuss several of these programs in more detail below.

Figure 8

Major State Forest Management Programs

2017‑18 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Description |

Funding |

Primary |

|

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection |

|||

|

Forest Health grants |

Provides grants for large forest management projects including reforestation, fuel reduction, pest management, conservation easements, and biomass utilization. Program goals are to increase carbon storage in forests and reduce wildfire emissions. |

$200.0 |

GGRF |

|

Vegetation Management |

Assists SRA landowners on their lands—primarily through the use of prescribed fire—to reduce wildland fuel hazards. |

9.6 |

GGRF |

|

Demonstration State Forests |

Manages eight demonstration state forests for research and education on sustainable forestry practices. |

9.0 |

Forest Resources Improvement Fund |

|

Reforestation |

Provides technical assistance related to reforestation to the forest industry, public agencies, and private landowners. Operates the L.A. Moran Reforestation Center, the state’s seed bank and tree nursery. |

5.5 |

General Fund, TRFRF |

|

California Forest Improvement |

Provides cost‑sharing grants to landowners for management planning, site preparation, tree purchase and planting, timber stand improvement, habitat improvement, and land conservation. |

5.0 |

TRFRF |

|

Fire and Resource Assessment |

Provides information, data, analysis, and resource assessments of forests and rangelands for various state and federal programs. |

1.2 |

General Fund, SRA Fire Prevention Fund, GGRF |

|

Watershed Protection |

Conducts monitoring and research for projects that restore or impact watersheds, provides technical assistance and input into Forest Practice Rules development, and provides interagency watershed and fisheries‑related trainings. |

0.8 |

General Fund |

|

California Natural Resources Agency |

|||

|

Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Program management |

Regulates timber harvesting by reviewing Timber Harvest Plans and other documents, develops ecological performance measures, and coordinates some forestry activities across state departments. |

$46.0 |

TRFRF |

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife |

|||

|

Forest Land Anadromous Restoration grants |

Provides grants for habitat improvement for the state’s at‑risk salmon species, including addressing legacy forest management impacts. |

$2.0 |

TRFRF |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

|||

|

Clean Water grants |

Provides grants for projects that can demonstrate water quality improvement through the application of forest management measures such as stream restoration, road stabilization, post fire recovery, and fuels reduction. |

$2.0 |

TRFRF |

|

Total |

$281.1 |

||

|

GGRF= Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; SRA = State Responsibility Area; and TRFRF = Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund. |

|||

State’s Largest Forest Health Program Currently Funded With GGRF. The 2017‑18 budget package provided a significant one‑time infusion of funding for forest management from the state’s GGRF. Specifically, as shown in Figure 8, $200 million was allocated to CalFire for forest health and fire prevention activities that either reduce GHG emissions through wildfire avoidance, or improve carbon sequestration by preserving forestland or improving forest health. (CalFire also received one‑time allocations from GGRF for forest health in previous years but at lesser levels—$25 million in 2014‑15 and $40 million in 2016‑17.) CalFire plans to allocate these funds via grants for projects through its Forest Health Program. Local entities and collaboratives—such as the Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program, described in the nearby box—will be eligible to apply for these funds. Based on the grant criteria CalFire has developed, eligible projects must show that they will reduce GHGs, be located in a priority region (such as an area with elevated tree mortality or wildfire threats), and result in co‑benefits (such as improved air quality improvement or conservation of wildlife habitat). The Governor’s budget proposal for 2018‑19 proposes an additional $160 million from GGRF to CalFire for this program.

Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program

The Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program (WIP) was created in March 2015 as a coordinated effort between the state (through the Sierra Nevada Conservancy) and the U.S. Forest Service, along with other governmental and local agency partners. It is intended to increase the pace and scale of restoration and forest health activities within several key California watersheds. The program is formalized through a memorandum of understanding between the state and federal governments, which is designed to increase coordination of restoration efforts at the regional and watershed levels. Both the extent of land area that is covered and the number of agencies proactively working together make this collaborative effort unique.

The WIP has three main goals for the Sierra Nevada region: (1) increase investment in forest restoration from a broad array of stakeholders, (2) identify policy‑related issues that need to be addressed in order to restore Sierra forests and watersheds to a healthier state, and (3) maintain and expand existing forest‑related infrastructure—such as lumber mills and other facilities that process or dispose of wood and woody biomass—in order to support the pace and scale of needed restoration. Currently, WIP partners are working to assess restoration needs and secure funding. The program has identified a subregion in which to conduct initial pilot projects that accelerate regional scale forest and watershed restoration, which it is calling the Tahoe‑Central Sierra Initiative. It recently received a $5 million grant from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund Forest Health Program to begin implementing forest health projects in this subregion.

California Forest Improvement Program (CFIP) Helps Smaller Landowners Maintain Their Forestlands. CFIP assists private nonindustrial landowners manage their forestlands. Specifically, the program offers grants to help individual landowners with land management planning, land conservation practices, fish and wildlife habitat improvement, tree purchase and planting, and practices to enhance the productivity of the land. As shown in Figure 8, this program has received $5 million from the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund (TRFRF) in 2017‑18. (In some recent years, it has also received funding from the High‑Speed Rail Authority for mitigation related to the state’s high‑speed rail project.) The state typically pays 75 percent of the overall costs of the project, but is authorized to pay up to 90 percent if the project meets certain criteria (such as responding to substantial fire damage). The CFIP is structured such that landowners apply for funding, receive an approved agreement and scope of work from CalFire, then undertake planning and/or complete the work on their land. Once work is completed, CFIP reimburses landowners for a share of the costs. The state also conducts oversight during and after the projects. For example, participants must agree to keep land in a “compatible use” (that is, in a forested state) for at least ten years after work is completed, and the state monitors that this agreement is kept. While the number varies each year based on funding levels and the specific projects undertaken, the program funded 183 projects statewide over the past two years.

VMP Is State’s Main Forest Program for Prescribed Fire. Prescribed fire—employed under appropriate conditions—is an important restoration tool that improves forest resiliency and reduces the risk of large, high‑intensity fires. It is also generally more cost‑effective than mechanical thinning and can reach remote areas of the forests where equipment cannot go. Most prescribed burns occur under CalFire’s VMP—the state’s main prescribed burn program. The VMP provides a cost‑sharing option for landowners to assist with the use of prescribed fire. The program also funds some mechanical thinning projects, though prescribed fire is its primary focus. The specific cost‑share ratio varies based on the share of public‑to‑private benefit, as determined by CalFire. Eligible applicants must treat forestland located within the SRA. Landowners apply to participate in the VMP, and CalFire determines whether a project is suitable for funding. The local CalFire unit then provides the personnel, equipment, and expertise to implement the project, and the department assumes the liability for conducting the prescribed burn. As shown in Figure 8, in 2017‑18 the program received about $10 million from the General Fund.

The VMP treated 17,500 acres with prescribed burns in 2017, somewhat more than the average of approximately 13,000 acres treated per year since 1999. This represents a decrease from about 30,000 acres treated per year from 1982 through 1998. This decrease is due to several factors, including (1) an increase in the amount of planning and documentation required for prescribed burns due to stricter air quality regulations, (2) projects more often being in close proximity to populated areas, and (3) longer fire seasons that can divert CalFire foresters and firefighters who would be available to plan and implement prescribed burn projects.

State Funding for Forest Health Activities Comes From Various Sources. As shown in Figure 8, most of the support for the state’s forest health programs comes from GGRF, the General Fund, or TRFRF. TRFRF, which was created by AB 1492 in 2012, is funded by an assessment on lumber that generates about $40 million annually. The Forest Resources Improvement Fund supports the eight demonstration forests CalFire operates to test and disseminate sustainable practices. That fund receives revenues generated by sales of timber or biomass fuels from those demonstration forests.

In addition to the programs displayed in Figure 8, the state has provided other one‑time resources for special initiatives related to forest and watershed health. For example, in 2017‑18 the Legislature provided roughly $10 million from the General Fund to CalFire and the Office of Emergency Services for one‑time grant programs to address the recent increase in tree mortality, including to support local efforts to remove dead and dying trees that pose a threat to public health and safety. The state has also traditionally relied on funding from voter‑approved resource bonds for some forest and watershed health initiatives. For example, Proposition 84 (2006) set aside $180 million for the Wildlife Conservation Board to implement a program to conserve and restore forestlands, including by acquiring conservation easements. Proposition 1, passed by voters in 2014, included $1.5 billion for various watershed protection and restoration efforts, many of which may be implemented in forestlands.

Additionally, the Legislature recently passed legislation, Chapter 852 of 2017 (SB 5, de León), which places a new general obligation bond—Proposition 68—on the June 2018 ballot for voter approval. This bond would provide roughly $170 million across various state agencies that could be directed towards improving forest and upper watershed health. That total includes $35 million for CalFire to improve forest resiliency, of which at least $25 million must be allocated to the Sierra Nevada Conservancy for the Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program described earlier.

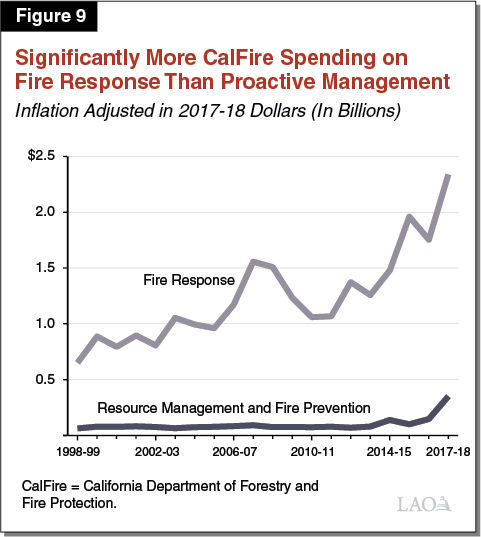

Significantly More CalFire Spending Dedicated to Fire Response Than Proactive Management. Figure 9 shows CalFire’s two major expenditure categories over the past two decades—fire response and forest management. As shown, spending for suppressing fires has far eclipsed that for proactive forest management activities. Specifically, fire response spending, which grew from $650 million in 1998‑99 (adjusted for inflation) to more than $2.3 billion in 2017‑18, makes up over 90 percent of the department’s annual spending. In contrast, spending on proactive activities like resource management and fire prevention remained relatively flat over the period, averaging $77 million and 7 percent of the department’s total expenditures through 2013‑14. Beginning in 2014‑15, the department began receiving some one‑time increases from GGRF for forest health activities. As shown, the significant addition of GGRF in 2017‑18 notably increases resource management spending compared to historical levels.

The data shown in the figure, however, may somewhat understate fire response and overstate resource management spending. This is because CalFire redirects internal staff resources to help respond to fire emergencies when needed. For example, when fire crews are needed for emergency fire suppression during the limited time of year they might otherwise be able to implement prescribed fires—such as during the fall and winter of 2017 when they were fighting the wine country and Southern California wildfires—it reduces the number of acres CalFire staff can treat with prescribed burns. Moreover, the number of severe fires and extended fire season to which CalFire has had to respond in recent years has necessarily placed the department in a recurring state of emergency response, as compared to previous years when it could more reliably count on an “off season” during which it could turn its focus to proactive fire prevention activities. On the other hand, the impacts of redirecting some resources are not as severe as those experienced by USFS—as discussed below—because CalFire is able to access additional resources to respond to emergencies.

Some Federal Funding Also Supports Forest Health Activities. In addition to state monies, the federal government also funds some forest management and health efforts. Besides managing the national forest system, the USFS operates its State and Private Forestry programs, which offer assistance to the state and private landowners for activities including forest health, cooperative forestry, conservation education, and urban and community forestry. The programs offer technical assistance, financial assistance, monitoring of forest health and sustainability, and educational and awareness campaigns. The 2017 federal budget provided $234 million for State and Private Forestry programs nationally. Additionally, the USFS Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, which received a total of $40 million in federal fiscal year 2017, provides grants for larger scale forest health projects on USFS lands conducted and funded in partnership with nonfederal partners. Based on grants from prior years, a share of these federal funds likely will be allocated to projects in California. The federal government also administers the Natural Resources Conservation Service, which provides significant support for private landowners. Finally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development Program has provided one‑time grant assistance to communities in the Sierra Nevada to develop collaborative biomass projects.

Large Share of Federal Forest Management Funding Has Been Redirected to Fight Fires. One key funding issue with the federal government’s forest management approach is “wildfire borrowing.” Currently, when fire suppression costs exceed the amount Congress has appropriated, USFS pays for these excess costs out of its other budget categories, including restoration. Unlike CalFire, USFS does not have access to emergency funds for large fires. For the federal fiscal year that ended in fall 2015, USFS redirected $700 million—about one‑quarter of its forest management budget—to cover fire suppression costs. This redirected money from other programs including recreation, research, watershed protection, rangeland management, and forest restoration. For example, the State and Private Forestry programs—the primary federal effort to provide technical and financial assistance to protect communities from wildfire—lost $37 million out of a total budgeted amount of $234 million that instead went to cover fire suppression costs across the nation. This practice of redirecting funds from other USFS activities contrasts with how the federal government pays for the response to other natural disasters, such as floods or storms. In those cases, the federal government typically provides additional funding to cover excess federal emergency response costs, rather than expecting those funds to be redirected from the portions of the affected department’s base budget that would otherwise be used for prevention and maintenance activities.

Local Governments Also Spend Money on Forest Health Activities. Counties, cities, special districts, and other local governments also invest in forest health activities within their respective jurisdictions. Examples include Community Wildfire Protection Plans, which some communities develop to identify forest fuel reduction priorities and other preventative measures. These plans are particularly common and encouraged by the federal and state governments in communities located adjacent to forestlands. Some limited examples also exist of mountain regions opting to undertake forest restoration projects intended to preserve local water quality, and using local dollars to match state bond funds from the Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) program. (The IRWM program provides bond funding—which must be paired with local funds—for regional groups to implement locally determined water resource projects.) For example, the Madera County IRWM group paired $1.5 million in local funds with an equal amount of state bond funds to reduce fuels in the Sierra National Forest in order to reduce wildfire risk and, in the words of its IRWM grant application, to help “meet long‑term water supply needs, [protect] water quality, and augment/restore environmental conditions.” Investments by local agencies and governments in discretionary forest management programs can be significantly limited in many rural forested areas of the state, however, due to small tax bases and—in many cases—economically disadvantaged populations.

Current Forest Conditions

Healthy Forests Display Natural Ecological Characteristics and Processes. In general, a forest is defined as being healthy when it reflects the natural variability, processes, and resilience it has historically displayed. Specifically, conditions in healthy forests typically include (1) a heterogeneous mix of tree species of different ages; (2) a density of vegetation that matches the supply and demand of light, water, nutrients, and growing space; and (3) a capacity to tolerate and recover from naturally occurring disturbances such as fire, insects, and disease. The majority of California’s forests currently do not meet these health criteria.

In this section, we discuss the poor conditions of forestlands across the state and the associated risks and implications, including increased incidence of major wildfires. We also discuss how expanding forest health activities could improve these conditions and the multiple benefits such improvements could yield.

Poor Forest Conditions

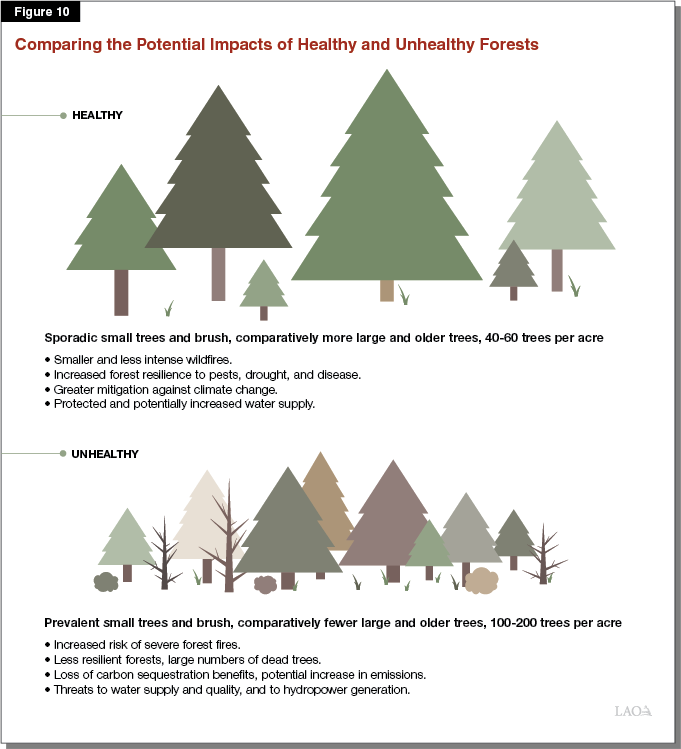

Forest Management Practices Have Increased Forest Density. As noted above, forest management practices and policies over the past several decades have (1) imposed limitations on timber harvesting, (2) emphasized fire suppression, and (3) instituted a number of environmental permitting requirements. These practices and policies have combined to constrain the amount of trees and other growth removed from the forest. This has significantly increased the density of trees in forests across the state, and particularly the prevalence of smaller trees and brush. Overall tree density in the state’s forested regions increased by 30 percent between the 1930s and the 2000s. These changes have also contributed to changing the relative composition of trees within the forest such that they now have considerably more small trees and comparatively fewer large trees. Figure 10 illustrates some key differences between healthy and overly dense forests. The increase in tree density can have a number of concerning implications for California’s forests—including increased mortality caused by severe wildfires and disease—as displayed in the figure and discussed below.

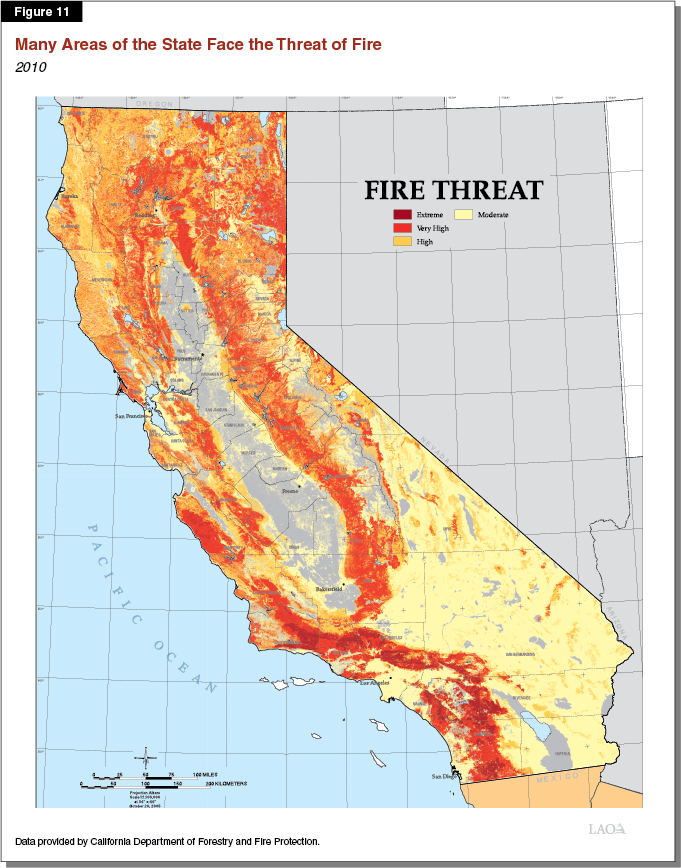

Increased Risk of Severe Forest Fires. Dense forest stands that are proliferated with small trees and shrubs contain masses of combustible fuel within close proximity, and therefore can facilitate the spread of wildfires. Moreover, these smaller trees can serve as “ladder fuels” that carry wildfire up into the crowns of taller trees that might have otherwise been out of reach, adding to a fire’s potential spread and intensity. As shown in Figure 11, CalFire estimates that most forested regions of the state face a high to extreme threat of wildfires. CalFire estimates the level of threat based on a combination of anticipated likelihood and severity of a fire occurring. Large and intense fires can have widespread negative consequences, as discussed below in the context of recent California wildfires.

Less Resilient Forests, Large Numbers of Dead Trees. In addition to increasing fire risk, overcrowded forests and the associated competition for resources can also make forests less resilient to withstanding other stressors. For example, trees in dense stands become more vulnerable to disease—including infestations of pests such as bark beetles—and less able to endure water shortages from drought conditions. This vulnerability has been on display in recent years, as an estimated 129 million trees in California’s forests died between 2010 and 2017, including over 62 million dying in 2016 alone. While this is a relatively small share of the over 4 billion trees in the state, historically, about 1 million of California’s trees would die in a typical year. Moreover, most of the die‑off is occurring in concentrated areas. For example, the Sierra National Forest has lost nearly 32 million trees, representing an overall mortality rate of between 55 percent and 60 percent. When dead trees fall to the ground they add more dry combustible fuel for fires, as well as pose risks to public safety when they fall onto buildings, roads, and power lines.

Loss of Carbon Sequestration Benefits, Potential Increase in Emissions. Another implication of the deteriorating conditions of the state’s forests relates to how they exacerbate climate change. Live trees absorb and store carbon dioxide, thereby reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. In this way, healthy forests can be an important tool in offsetting climate change. Large older trees, however, store and sequester significantly more carbon than small trees and brush. As such, the dense conditions of the state’s forests—in which small trees are overcrowding and inhibiting the growth of larger, older trees—represent a lost opportunity to sequester GHG. Moreover, dead trees and wildfires release a large amount of carbon into the atmosphere at once, thereby contributing to climate change. According to the state’s draft Forest Carbon Plan, “forested lands in the state are the largest land‑based carbon sink, but recent trends and long‑term evidence suggest that these lands will become a source of overall net GHG emissions if actions are not taken to protect these lands and enhance their potential to sequester carbon.” CARB and climate researchers are currently attempting to quantify these GHG effects, to help the state better understand the potential carbon‑related benefits and risks associated with forests and wildfires.

Threats to Water Supply and Quality, Hydropower Generation. Scientists have identified several ways in which forest density can reduce the amount of water that runs off from source watersheds into rivers and streams for downstream uses. For example, if the forest canopy is too thick, snow will collect on the tops of the trees and be exposed to direct sunlight, causing it to more quickly evaporate rather than collecting on the ground and slowly melting into runoff. A greater volume of trees also means more water may be lost to evapotranspiration—consumption by the trees in order to grow—also leaving less available for runoff. Additionally, mountain meadows that have become overgrown with trees are less able to play their traditional role of “sponges” that store and gradually release snow and water.

Poor forest conditions can also affect water supplies when they contribute to severe fires. After such fires, burned and denuded hillsides are prone to discharging large amounts of sedimentation into streams, rivers, and reservoirs during storms. Downstream, these sediments can affect both water quality (by introducing soils, nutrients, and pollutants into water sources) and water supply (by displacing capacity in reservoirs). Excessive sedimentation in rivers and reservoirs can also impair the ability to generate hydropower when it clogs intakes, turbines, and other components of hydroelectric facilities.

The risk of wildfires also threatens the system that supplies water for millions of downstream water users. Of particular concern for millions of Californians is the risk to the Feather River watershed, which drains into Oroville Lake—the primary water source for the State Water Project (SWP). The SWP, which is operated by the state’s Department of Water Resources (DWR), is a water storage and delivery system that transports water from Northern California to supply 25 million people—two‑thirds of the state’s population—living across the state, as well as 750,000 acres of irrigated farmland mostly in the Central Valley.

The high potential for a fire is also a threat for the Central Valley Project (CVP), a separate water storage and delivery system owned and operated by the federal government. The CVP collects mountain runoff into reservoirs and then delivers it through canals to irrigate about one‑third of all agricultural land in the state, as well as to provide municipal water for close to 1 million households. Fires affecting any of the multiple Cascade and Sierra Nevada watersheds whose runoff feeds reservoirs for the CVP water delivery system would have major implications—in particular for the Pit and McCloud watersheds, which drain into Shasta Lake.

Increased Incidence of Major Wildfires

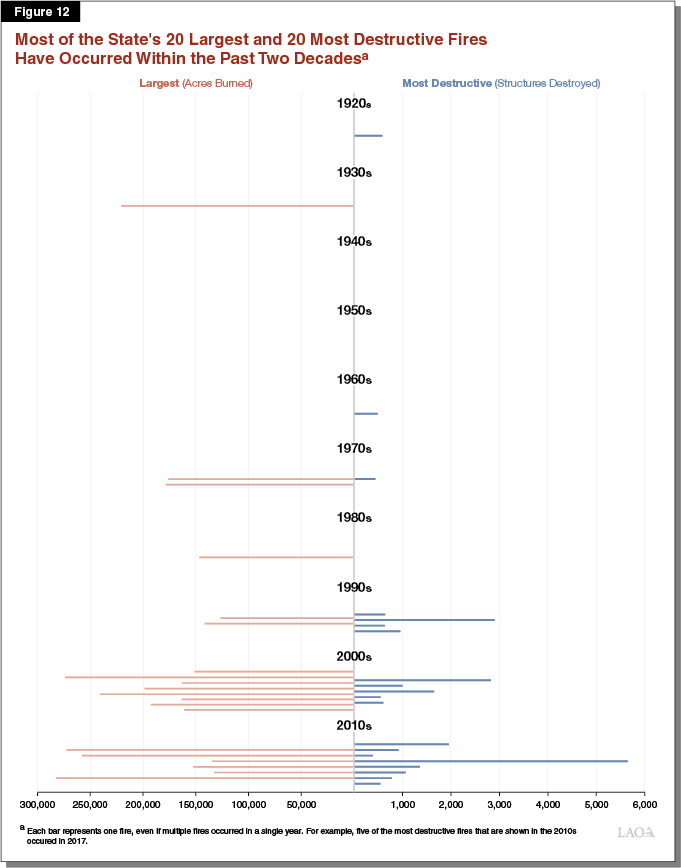

Poor Forest Conditions Have Contributed to Significant Wildfires in Recent Years. Recent events have revealed that the risk created by poor forest conditions has begun to manifest in increasingly frequent and severe wildfires. Figure 12 shows the 20 largest fires (as measured by acres burned) and 20 most destructive fires (as measured by number of structures destroyed) in recorded state history. As shown, the majority of such fires have taken place within the past 20 years. While the overall acreage of fires burned across the state’s forests varies from year to year, the figure shows that the acreage burned by individual fires has been on an upward trend, highlighting an increasing incidence of severe fires. Additionally, while it is to be expected that fire risk and impacts would increase over the past several decades as human development spreads into areas that formerly were wilderness—creating more opportunities for destruction—the extent of the increase in recent years is significant. Of particular note, both the largest and the most destructive fires the state has ever experienced occurred in 2017—the Thomas fire in December, which burned nearly 282,000 acres, and the Tubbs fire in October, which destroyed 5,643 structures and significant portions of the city of Santa Rosa. Such severe fires can have negative effects on a number of different sectors, as illustrated by the examples discussed in the nearby box.

Recent Fires Have Had Wide‑Reaching Negative Impacts

Examples of how recent fires have impacted various sectors include the following:

Property. Property losses from the October 2017 “wine country” fires in Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Lake, and Mendocino Counties—which included the Tubbs Fire—are expected to add up to between $6 billion and $8 billion. According to the California Department of Insurance, more than 14,000 homes were damaged or totally destroyed, along with nearly 4,000 commercial buildings, 3,200 cars, and 111 boats. These totals understate the total damage, as they do not include uninsured properties or vehicles.

State Costs. The state annually spends significant amounts on wildfire response and recovery. In the past ten years, the state has spent nearly $10 billion from the General Fund for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s wildfire response activities. Recovery costs for debris removal and cleanup, social services (such as shelters and social services), and local assistance (including rebuilding public infrastructure and backfilling property tax losses) can also be significant. For example, the administration estimates that state expenditures on wildfire and recovery activities for the 2017 wine country fires have totaled about $1.5 billion. While costs associated with these fires are eligible for federal reimbursement, the administration estimates that the state General Fund share of these costs will be roughly $400 million.

Air Quality. Smoke from the multiple wildfires that burned in the northern part of the state in October 2017 affected air quality and closed schools, airports, and businesses in cities at least 100 miles away from the fires. At its worst, fine particulate matter air pollution in San Francisco—located over 40 miles away from the fires—was measured at 190 micrograms per cubic meter, more than five times the federal health standard of 35 micrograms per cubic meter.

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions. The Sierra Nevada Conservancy estimates that the 2013 Rim Fire—the fourth largest in California history—released 11.4 metric tons of GHG emissions, equivalent to what 2.6 million cars would release in a year. Moreover, burned trees left on the landscape will continue to release additional emissions as they decay over time.

Water Supply and Quality. Initial estimates suggest the 2012 Bagley Fire resulted in an estimated 330,000 metric tons of fine sediment and 170,000 metric tons of sand, gravel, and cobbles deposited into Lake Shasta—which stores drinking and agricultural water supplies for millions of customers.

Habitat for Fish and Wildlife. One study found that the 2013 King Fire destroyed 30 out of 45 known habitat sites in the El Dorado National Forest for the California Spotted Owl, and that those sites remained unsuitable even a year after the fire.

Improving Forest Conditions

Consensus That Suite of Activities Needed to Improve Conditions. As described earlier, forest managers can undertake several types of activities or treatments to reduce forest density and improve the benefits that forests naturally provide. These include mechanical thinning, prescribed burning, managed wildfire, stream and meadow restoration, and land preservation. Most forest experts agree that, given the diversity of the state’s forests and extent of degraded conditions, managers should implement a combination of such activities across the state. Not every treatment can or should be employed in every situation. For example, steep and remote forested hillsides that lack road access are not practical locations for mechanical thinning operations. Additionally, in some cases treatment approaches might be most effective when used in combination. For example, applying prescribed fire to areas that currently contain large amounts of ladder fuels may not be safe until after they have been mechanically thinned because of the greater risk that a fire might escape control. Post‑thinning, however, prescribed fire can be a good way to restrain regrowth of “surface fuels” (small trees and brush) and stimulate natural processes.

Improved Forest Health Could Yield Multiple Benefits. As discussed earlier, forests provide multiple statewide benefits. Taking additional steps to improve the health of the state’s forests could restore, protect, and potentially magnify these key functions. Specifically, research indicates that thinning and restoring forests across the state potentially could lead to increased forest resilience against pests and disease, additional carbon storage, and potentially an increase in snowmelt runoff and water supply. Moreover, while fully preventing forest fires is impossible—given inevitable lightning strikes and widespread human interactions—reducing the amount of fuels in the forest could significantly reduce the size and severity of the fires that will eventually occur. For example, modeling of different fire scenarios in the Mokelumne watershed estimated that fuel treatments likely would reduce fire size by an average of roughly 40 percent, and reduce the acreage of a high‑intensity wildfire by approximately 75 percent. (Please see the box below for additional discussion of this study.)

Analysis of Mokelumne Watershed Finds Forest Treatments Yield Economic Benefits

In 2014, the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, U.S. Forest Service, and The Nature Conservancy published an analysis of how wildfire might affect resources in the Mokelumne River watershed under various hypothetical conditions. The report, Mokelumne Watershed Avoided Cost Analysis: Why Sierra Fuel Treatments Make Economic Sense, simulated the outcomes of five potential fire scenarios with and without the application of fuel treatment projects such as forest thinning and prescribed burning. The analysis found that fuel treatments would significantly reduce the size and severity of wildfires, and that the economic benefits of the modeled fuel treatments were two to three times the costs of their implementation. Specifically, the report estimated that while undertaking fuel reduction projects in the watershed would cost nearly $70 million, avoided costs from a severe wildfire (such as structures saved and avoided fire clean‑up) as well as potential revenue from the thinning activities (such as from merchantable timber, carbon sequestration, and biomass that could be used for energy or other purposes) could yield benefits of between $126 million and $224 million. The analysis found these economic benefits would accrue to both public and private entities, including the state and federal governments, residential property owners, timber companies, and water and electric utilities.

Forest Treatments Not Without Trade‑Offs. While forest management activities can help improve overall forest health, reduce fire risk, and potentially yield other benefits, their implementation can also have other, less desirable consequences. For example, in some cases removing trees can reduce available habitat for certain wildlife. Similarly, roads and heavy equipment necessary for mechanical thinning operations can both disrupt habitat for terrestrial species, as well degrade conditions for fish and aquatic species by increasing sediment runoff into streams. Prescribed and managed burns have been among the most controversial types of treatments because of the potential for the resulting smoke to temporarily degrade air quality in surrounding communities. Forest managers generally try to minimize and mitigate for these types of negative impacts, for example by leaving certain stands of trees in place for wildlife habitat, or by applying prescribed burns only under specific conditions that minimize public health impacts. The regulatory permitting processes described earlier help ensure these types of mitigations are implemented. On the whole, forest managers and the public must weigh the potential negative impacts of undertaking forest health activities against the potential benefits of applying the treatments—and against the risks inherent in not taking actions to improve forest and watershed health.

Findings

While broad consensus exists about both the problematic conditions of the state’s forests and the types of activities needed to address them, the pace of making the needed improvements is slow. Moreover, the scale of the improvement projects that are currently taking place is relatively small compared to the identified need. In this section, we identify and discuss some of the barriers that impede major progress towards healthier forests. We organize our findings into four categories: (1) funding and coordination, (2) policies and practices, (3) local assistance programs, and (4) disposal of woody biomass. Figure 13 summarizes our key findings.

Figure 13

Summary of Findings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. |

Funding and Coordination Not Adequately Addressing Forest Conditions

Large Identified Costs to Improve Forest Conditions, State Spending Not Keeping Pace. As discussed earlier, ongoing state and federal funding for proactive forest management in California has averaged around $100 million annually in recent years, treating an estimated 280,000 acres per year. This level of treatment has not been sufficient to maintain healthy natural forest conditions, and a backlog of needed activity has formed and continues to grow. Experts suggest significant additional funding would be needed to increase the pace and scale of treatment activities such that they meaningfully improve current forest conditions. While no conclusive, comprehensive assessment of needs and costs has been completed, recent estimates for certain regions include the following:

- Restoration on Nonfederal Lands. The draft Forest Carbon Plan states that 20 million acres of forestland in California face high wildfire threat and may benefit from fuels reduction treatment. According to the plan, CalFire estimates that to address identified forest health and resiliency needs on nonfederal lands, the rate of treatment would need to be increased from the recent average of 17,500 acres per year to approximately 500,000 acres per year. The plan does not include associated cost estimates.

- Restoration on Federal Lands. Based on its ecological restoration implementation plan, USFS estimates that 9 million acres of national forest system lands in California would benefit from treatment. The draft Forest Carbon Plan sets a 2020 goal of increasing the pace of treatments on USFS lands from the current average of 250,000 acres to 500,000 acres annually, and on BLM lands from 9,000 acres to between 10,000 and 15,000 acres annually.

- Restoration in the Sierra Nevada Region. A recent Public Policy Institute of California study cited estimated forest treatment needs of between 90,000 and 400,000 acres annually in Sierra Nevada forests to bring them back to historical conditions and functions. The authors found that the associated costs of mechanical thinning could vary widely—from net costs of around $800 per acre to net revenues of nearly $1,900 per acre—depending on the size of the trees removed and their potential sale value. This significant range results from the degree to which the thinning project primarily produces non‑revenue generating woody biomass, as compared to producing large trees that can be sold as timber. The report also cited a wide range of costs for applying prescribed fire—from $75 to $647 per acre—depending on the landscape where it is applied.