LAO Contact

April 27, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Meeting Workforce Demand for Certified Nursing Assistants in Skilled Nursing Facilities

In this post, we provide background on new staffing requirements for certified nursing assistants (CNAs) working in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), describe the Governor’s proposals to address these new staffing requirements, assess those proposals, and make associated recommendations.

Background

SNFs Provide Round-the-Clock Care for Many Older Adults and Other Californians. SNFs offer short-term rehabilitation services as well as long-term care for patients—primarily older adults—who have serious medical conditions and are unable to perform basic daily activities (such as bathing and eating) on their own. In 2016, approximately 1,100 SNFs in California served nearly 100,000 patients. The vast majority of these SNFs (90 percent) are operated by for-profit entities, while the remaining facilities are operated primarily by nonprofit organizations. SNFs must be licensed, inspected, and certified by a number of federal and state entities to operate. In California, the Department of Public Health (DPH) is responsible for licensing and regulating SNFs.

SNFs Receive Vast Majority of Their Funding From Federal and State Sources. In 2016, SNFs in California received about 90 percent of their patient revenue directly from federal and state funding for the Medi-Cal and Medicare programs. In California, state Medi-Cal rates paid to SNFs are typically matched with a 50 percent federal cost share. The remaining less than 10 percent of patient revenue comes from other third-party payers or from patients not covered by a third-party payer.

Medi-Cal and Medicare Rates to Cover Nearly All SNF Costs. Both Medi-Cal and Medicare pay SNFs per diem rates for each patient admitted to their facilities. The rates are updated annually. They are meant to cover nearly all of the costs of providing skilled nursing services to admitted patients. For Medi-Cal, the rates for most SNFs consider five cost categories—resident care labor costs, resident care non-labor costs (as an example, housekeeping), administrative costs, property costs, and costs passed through to facilities (for example, new federal or state mandate costs). State law limits the first three cost categories—labor, non-labor, and administrative costs—to a certain percentile of average costs incurred by facilities in specified peer groups. Labor costs, for example, are limited to the 90th percentile of average SNF labor costs within each peer group. (Facilities are grouped based upon various factors, including costs and geographic considerations.)

CNAs Provide Basic Care to Patients in SNFs. Under the supervision of registered nurses and licensed vocational nurses, CNAs perform basic duties such as feeding, bathing, and dressing patients and taking and monitoring vital signs (such as patients’ temperature and blood pressure). According to the California Association of Health Facilities, about 32,000 CNAs currently work in SNFs. Based on our discussions with CNA employers, a somewhat smaller number of CNAs work in other settings, such as hospitals, assisted living facilities, and private homes. Statewide, CNAs earn an average of about $14 per hour working in a SNF, with CNAs typically earning somewhat more in hospitals.

Several State Requirements to Become a CNA. To become a CNA, individuals must:

Be at least 16 years old.

Pass a physical (health) screening and criminal background check.

Complete an approved training program consisting of at least 60 classroom hours and 100 hours of clinical practice at a SNF.

Pass a state CNA certification examination.

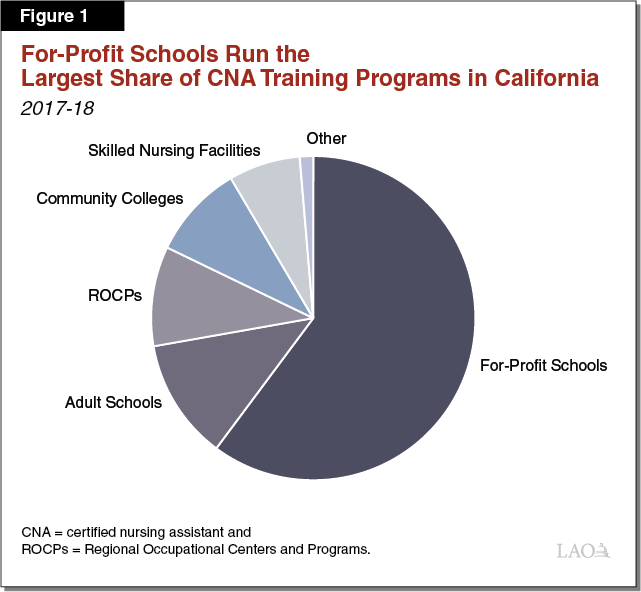

Various Training Programs Prepare CNAs. According to DPH, California has a total of 673 CNA training programs. (DPH counts each cohort of students being trained by a given provider as a separate program, such that a provider can be associated with multiple programs.) Training providers include school district-run adult schools and Regional Occupational Centers and Programs, California Community Colleges (CCCs), nonprofits (such as the American Red Cross), and for-profit schools (such as Coast Health Career College in Orange County). They also include some SNFs that provide their own training programs on site. Currently, SNFs operate 48 of the state’s 673 CNA training programs. Under the SNF training model, SNFs hire their own instructors (often employees of the SNF) and often pay students hourly wages while they receive training. In exchange, SNFs typically ask, but do not require, students to commit to working at the SNF for a specified amount of time (such as one year) after becoming a CNA. Figure 1 shows that for-profit schools account for the largest share of CNA training providers, followed by adult schools.

State Program Offers Reimbursement for Employee Training Costs. The Employment Training Panel (ETP), a division of the Employment Development Department, operates a grant program that reimburses employers for a portion of their costs to upgrade the skills of their workers and, in some cases, new hires. Reimbursements are funded by the Employment Training Tax, which is a special tax paid by California employers. Members of ETP decide which businesses to award these training funds. To receive reimbursement for training costs, a business must pay trainees an ETP-determined minimum wage after the training is completed and must retain employees for at least three months after the training. ETP currently funds several training programs for health care workers.

DPH Certifies CNAs and Oversees Training Programs. State law charges DPH with reviewing applications from individuals seeking CNA certification. State law also charges DPH with approving and overseeing CNA training programs. This process includes reviewing training providers’ proposed lesson plans and ensuring that instructors meet the state’s minimum qualifications. With regards to the minimum qualifications, existing state regulations require instructors to have at least two years of experience as a registered nurse or licensed vocational nurse, with one or more of those years spent providing direct care to patients in a SNF. DPH also ensures that training programs maintain a minimum student-faculty ratio of 15 to 1 for clinical instruction. (DPH does not require a minimum student-faculty ratio for classroom instruction.)

State Regulations Set Time Frames for DPH to Process Applications. Current state regulations require DPH to respond to applicants for new CNA training programs and new CNA certifications within set time frames. During the initial application process, the department must notify applicants as to whether their application is complete or incomplete within 30 days of its submission. Once DPH accepts the application as complete, the department has up to 60 days to issue a final decision on a training program and up to 90 days to decide whether to issue a certificate to a new CNA.

New State Requirements for SNFs to Provide Higher Minimum Levels of Nursing Hours Per Patient. State law defines nursing hours for SNFs as the number of hours of work performed by registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, and CNAs. Prior to 2017‑18, the state required SNFs to provide each patient with a minimum of 3.2 nursing hours per day. The 2017‑18 budget package raised this requirement to 3.5 nursing hours per day, and added a new requirement that CNAs provide at least 2.4 of the minimum 3.5 nursing hours per day. Both of the new requirements become effective July 1, 2018. If a facility cannot comply with one or both of the requirements by July 1, 2018, it can request a “workforce shortage” waiver from DPH. The department is currently finalizing the application and evaluation process for this waiver.

A Majority of California SNFs Already Meet the New Minimum Staffing Requirements . . . Based on recent data from the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD), a majority of SNFs currently meet both the higher minimum nursing hours requirement and the new minimum CNA nursing hours requirement. According to the data, the average SNF in California provides each patient with 3.8 nursing hours per day, of which 2.5 nursing hours per day are provided by CNAs.

. . . But Many SNFs Do Not. SNFs, however, vary notably in the number of nursing hours they provide to each patient per day. Of the approximately 1,100 SNFs statewide, 465 SNFs (42 percent) do not meet the minimum CNA hours requirement. We estimate that these SNFs will need to hire between 1,700 and 2,400 additional CNAs to meet the requirement, increasing the total number of CNAs currently working in SNFs statewide by between 5 percent and 7.5 percent. To the extent some SNFs that do not meet the minimum CNA hours requirement request and receive workforce shortage waivers, the number of CNAs that need to be hired would be lower.

Governor’s Proposals

To assist SNFs with meeting the state’s new minimum staffing requirements, the Governor’s budget includes ongoing funding to cover SNF’s higher staffing costs as well as two one-time proposals intended to produce more CNAs in the near term. The Governor also submitted a related April Finance Letter to expedite DPH processing of CNA applications. We describe each of these proposals below.

Provides $21.6 Million General Fund ($43.2 Million Total Funds) in Medi-Cal for SNFs to Cover Higher Staffing Costs From New Requirements. The Governor’s budget proposes to provide SNFs that are not in compliance with one or both of the new requirements with a state add-on to their Medi-Cal rates in 2018‑19. The state add-on would be matched with federal funds at Medi-Cal’s traditional cost share of 50 percent (or $21.6 million in 2018‑19). To calculate the add-on, the administration first used data from OSHPD to determine which facilities are not in compliance with the new requirements. Then, assuming SNFs could hire the number of staff needed at the wages currently built into their Medi-Cal rates, the administration calculated an add-on amount per day for each eligible facility. The administration proposes that this funding only be used by SNFs to hire additional staff to meet the new requirements. The amount of, and the eligibility for, the add-on will be re-determined by the state’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) in 2019‑20. In 2020‑21, DHCS will likely incorporate any additional costs associated with these new requirements into the regular reimbursement rates for each facility.

Proposes $2.5 Million in One-Time ETP Funds for CNA Training. The Governor also proposes that ETP award $2.5 million to reimburse SNFs and other training providers for the cost of providing CNA training. Though ETP does not have a detailed expenditure plan at this time, it indicates it likely would allocate some of the $2.5 million to SNFs that currently operate on-site CNA training programs to expand those programs. It also likely would allocate some funds to SNFs that do not have existing CNA training programs to develop such programs. Additionally, it likely would allocate some of the funds to SNFs for providing on-the-job training to CNAs after they receive their CNA certification.

Proposes $2 Million One-Time Proposition 98 General Fund for CCC to Expand CNA Enrollment Slots. Lastly, the Governor’s budget provides CCC with $2 million for more CNA training. The CCC Chancellor’s Office would allocate the funds through CCC’s Strong Workforce program, which the Legislature created in 2016‑17. Specifically, the Chancellor’s Office would distribute the funds to the program’s seven regional consortia of community colleges based upon each region’s projected CNA job openings, number of CNA programs, and enrolled CNA students in 2017‑18. The Chancellor’s Office estimates that the proposed funding could support about 1,300 community college enrollment slots.

Adds 15 Positions at DPH for CNA-Related Work. In an April Finance Letter, the Governor proposes to add 15 permanent positions at DPH to accommodate existing workload (primarily to reduce existing application backlogs) and expected workload increases in CNA training program approval and certification of new CNAs. The Governor proposes to fund these additional positions (estimated to cost between $1 million and $1.5 million) by increasing fees on health care facilities licensed by DPH.

Assessment

Summary Assessment. By increasing staffing requirements, the state created two major near-term challenges for SNFs. One challenge is covering higher resulting SNF staffing costs. We believe the Governor’s approach of increasing per diem rates to cover these higher costs is reasonable. The other major near-term challenge created is finding new CNAs to work in SNFs. We believe the Governor’s proposals relating to the supply of CNAs are unlikely to be effective unless the Legislature changes state requirements for being a CNA instructor. We also have concerns with the Governor’s DPH proposal. In this instance, the Governor proposes increasing DPH staff without first clearly identifying DPH’s root processing problems. Below, we assess each of the Governor’s proposals. In the following “Recommendations” section, we offer several alternatives designed to help achieve immediate state goals more effectively. In the longer term, the state could rethink more fundamentally the policies it currently has for helping private markets respond to changes in state staffing requirements.

Add-On to Medi-Cal Rates Paid to SNFs Is Reasonable. Given the large share of SNFs’ patient revenue coming from Medi-Cal and the significant number of SNFs that are not in compliance with one or both of the new staffing requirements, we believe providing noncompliant SNFs with an add-on to their Medi-Cal rates in 2018‑19 is reasonable. We also think re-determining eligibility for the add-on in 2019‑20 and incorporating the add-on into the regular reimbursement rate for each facility beginning in 2020‑21 are reasonable actions.

Governor’s CNA Proposals Fail to Address Key Barrier to Expanding Training Programs. In reviewing the Governor’s CNA proposals, we spoke with a number of CNA training program directors about their capacity to expand enrollment to meet higher demand for CNAs. Program directors generally report they have wait lists of applicants seeking to enroll in CNA training programs. These administrators indicate that the existing state rules on minimum qualifications for instructors significantly limit their ability to recruit and hire faculty to meet enrollment demand. For example, program directors note that existing regulations prevent them from hiring experienced nurses who provide direct care to elderly patients in acute care hospitals rather than SNFs. Additionally, nurses who serve as directors or other administrators in SNFs are excluded from serving as CNA instructors because they do not provide direct care. These state regulations exceed federal regulations, which require instructors to have at least one year of two years of nursing experience in the “provision of long term care facility services.” Absent changing state policy to align more closely with the federal requirements, training programs indicate they would have great difficulty hiring instructors to expand their enrollment.

State’s Credentialing Requirement Adds to Staffing Difficulties for Adult Schools. CNA program directors at adult schools indicated to us that finding and hiring instructors is even more difficult for them than other CNA training providers. This is because in addition to finding instructors that have experience providing direct care in a SNF (per state regulations), adult school instructors must have a state-approved career technical education teaching credential. Obtaining a teaching credential can be costly for aspiring faculty, and credential programs can take more than a year to complete. By contrast, state law does not require CCC instructors or CNA instructors hired by any other training provider to hold a teaching credential.

Governor’s ETP Proposal Could Be Refined. If the state were to align its CNA instructor requirements with federal requirements, we believe the Governor’s CNA training proposals would help increase the near-term supply of CNAs. We believe the proposals, however, could be refined to produce a greater increase in supply. Regarding the Governor’s ETP proposal, allocating funds to SNFs that provide on-site CNA training programs likely would boost production of new CNAs, particularly if the state required that the funds supplement and not supplant existing training funds. Allocating ETP funds for on-the-job training after individuals have earned their CNA certification, however, would not advance the state’s goals of producing more CNAs. (Historically, ETP has focused on on-the-job training rather than initial certification training. This may be one reason why ETP has indicated that it plans to support on-the-job CNA training as well as initial certification training. While an on-the-job focus may be a reasonable long-term policy, it is not aligned with the state’s immediate objective of producing more CNAs.)

Focusing Proposition 98 Funding on CCC Misses Opportunity to Leverage State’s Broader Adult Education System. We have somewhat similar concerns with the Governor’s CCC proposal and believe it too could be refined. The Governor limits his Proposition 98 proposal to community colleges, but adult schools currently are notable CNA training providers funded with Proposition 98. As a result, the Governor’s proposal misses an opportunity to broaden the reach of the funding. It also works directly counter to the state’s recent actions creating the Adult Education Block Grant (AEBG). In 2013‑14, the state began restructuring its adult education system to increase access for adult learners and improve coordination among adult schools and community colleges. As part of this restructuring, adult schools and community colleges formed AEBG consortia and developed regional plans for how they would coordinate their adult programs. These plans are intended to specify how training programs, such as the CNA program, are to be delivered within a region. The Governor’s proposal does not leverage these efforts.

DPH Slow to Approve New CNA Training Programs and Certify New CNAs. Based on our conversations with a number of CNA training program providers, the time taken for applicants to receive DPH approval often exceeds the regulatory time frames. Some providers indicated to us that it took DPH upwards of a year (four times longer than specified in regulations) to approve their training programs and upwards of six months (two months longer than specified in regulations) for their students to receive their certifications. Providers noted that some of the delays were because DPH found minor typographical errors or non-substantive omissions of information on applications. In recent months, DPH has redirected four part-time student assistants and two part-time office assistants to help address application processing delays. Although DPH indicates that processing times have improved, the administration still is unable to provide a clear picture of approval times. Moreover, DPH has indicated that it is developing an online application system, which could speed application processing times without the need for more processing staff.

Recommendations

Below, we offer a package of recommendations that (1) address existing root problems affecting the supply of CNAs and (2) modify the Governor’s proposals in an effort to increase CNA supply above the levels that likely could be achieved under those proposals.

Modify Statute to Provide Some Flexibility on Minimum Qualifications for CNA Instructors. We recommend the Legislature change statute to allow more types of nurses to qualify as CNA instructors. Specifically, we recommend the new policy permit as instructors nurses who have experience in an acute care hospital (or other facility in which a nurse would have provided a considerable amount of care for older adults even if not a SNF). We also recommend permitting as instructors nurses who do not routinely provide direct patient care but may, for example, supervise CNAs (and likely provided substantial direct patient care in the past). These changes would make recruiting and hiring instructors less difficult while continuing to ensure instructors meet federal requirements. Without such changes, augmenting funding for more training slots could have little effect, with much of the increased funding going untapped.

Recommend Legislature Modify Statute on Credentialing Requirements for CNA Instructors. To help adult schools in hiring instructors and align their requirements with CCC and other CNA training providers, we recommend the Legislature amend statute so that individuals no longer need a teaching credential to serve as CNA instructors at adult schools. (We recommend the Legislature also remove the credentialing requirement for other adult school instructors, as discussed in our February 2018 analysis on adult education.)

Recommend Legislature Direct ETP to Focus on Helping Individuals Become a CNA. To ensure the proposed ETP augmentation is used to increase the number of CNA training slots, we recommend the Legislature direct ETP to use the entire augmentation for this purpose, not post-certification on-the-job training. At $1,500 per enrollment slot, $2.5 million would fund about 1,700 new slots.

Recommend Legislature Modify Proposed CCC Grant Program to Include Adult Schools. To broaden the reach of the Governor’s proposed Proposition 98 CNA funding, we recommend the Legislature pass the funds through the AEBG program rather than the CCC Strong Workforce program. Under this recommendation, the California Department of Education and CCC Chancellor’s Office would be charged with jointly awarding, distributing, and overseeing grant funds to adult schools and community colleges in each consortium. Based on our review of CNA program costs, we believe that providing $1,500 per enrollment slot is reasonable. At this rate, $2 million would fund about 1,300 new CNA training slots.

LAO Recommended Approach Could Result in at Least 2,000 New CNAs for SNFs. Assuming that the state streamlines minimum faculty qualifications, we estimate that our recommended approach would fund about 3,000 new enrollment slots (about 1,700 enrollment slots funded by ETP and about 1,300 enrollment slots funded by Proposition 98). The number of actual CNAs produced and working in a SNF would be somewhat less than that amount. This is because DPH reports a 30 percent attrition rate from application for CNA certification to issuance of a CNA certificate (due to program attrition, exam failures, and other factors). Also, some CNA graduates get jobs in other health care settings. After taking into consideration these factors, the state likely would produce roughly 2,000 new CNAs—about in line with what SNFs will need to comply with the new state requirements. (In addition, some for-profit schools might expand their enrollment slots even if they do not receive special one-time state funding for this purpose, further increasing the overall supply of CNAs.) Without streamlining faculty qualifications, we think much of the proposed grant funds would go unspent, thereby not generating a notable number of additional CNAs.

Recommend Linking Additional DPH Positions to Other Decisions and Adding Reporting Requirement. We recommend the Legislature wait to decide on the 15 additional positions at DPH until it has acted on the rest of the administration’s CNA package of proposals. Importantly, some DPH positions might not be necessary if other programmatic changes (such as expanding minimum qualifications for CNA program instructors) were to be approved by the Legislature. In addition, DPH’s new online application system, which it anticipates rolling out this calendar year, should result in needing fewer positions to process applications. Moreover, some CNA-related workload very likely will be temporary—for example, we anticipate an increase in applications and waiver request the next few years. For all these reasons, we recommend the Legislature first make its CNA-related program decisions, then determine associated staffing levels and the appropriate mix of limited-term versus permanent positions. We also recommend directing DPH to report quarterly on average processing times within its Licensing and Certification Program for CNA-related workload. Information from these quarterly reports could help the Legislature moving forward in setting an appropriate DPH staffing level.