LAO Contacts

September 27, 2018

Improving Access to Dental Services for Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

- Introduction

- Background

- DDS Consumers Experience Problems With Oral Health and Access to Dental Care

- RCs and DDS Have Taken Steps to Address Consumers’ Dental Needs

- Analysis of Causes of The Access Problem

- Recommendations to Improve Consumers’ Access to Dental Services

- Conclusion

- Appendix: List of Acronyms Used in This Report

Executive Summary

Individuals with developmental disabilities face a number of behavioral, cognitive, and physical challenges that can adversely affect their health. Oral health is no exception. Individuals with developmental disabilities often need extra appointments or special accommodations that dentists may be unwilling or unable to provide. This report analyzes the extent to which dental services are available and sufficient for individuals with developmental disabilities. Finding that access challenges exist, we consider options and make recommendations for improving access.

Regional Centers (RCs) Coordinate Services—Including Dental Care—for Individuals With Developmental Disabilities. State law directs the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) to provide individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities (called “consumers” in statute) with services to meet their needs in the least restrictive environment possible. Twenty‑one independent nonprofit RCs coordinate services for consumers in the community.

Consumers Largely Pay for Dental Services With State‑Funded Dental Insurance. RCs may only pay for services directly if those services are not covered and funded by another public or private source, such as the state’s Medicaid program—Medi‑Cal—or private insurance. Nearly eight in ten consumers are income‑eligible for dental insurance through the state’s Medi‑Cal dental program, Denti‑Cal.

Traditional Approach to Dental Care Not Designed With DDS Consumers in Mind. The vast majority of Denti‑Cal providers work in private dental offices that are not typically set up to serve DDS consumers, especially consumers with severe behavioral or physical limitations. Some Denti‑Cal providers, such as Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice (RDHAPs), are trained to serve homebound and/or medically compromised patients and serve consumers more frequently, but there are relatively few of them statewide. While there are other potentially promising alternative approaches to dental service delivery for consumers, such as Virtual Dental Homes (VDHs) or house‑call dentistry, these are also relatively rare.

Many Consumers Lack Routine Dental Care. According to Denti‑Cal data, only about 22 percent of consumers enrolled in Denti‑Cal received even one dental service in each of 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Low Denti‑Cal Provider Participation and Denti‑Cal Payment Structure Limit Access for Consumers. Only 20 percent of the state’s dentists participate in Denti‑Cal. The relatively low number of Denti‑Cal providers means longer waits for appointments, farther distances to travel, and/or the decision to forgo dental care for consumers. Denti‑Cal also limits benefits or sets low reimbursement rates that constrain access to certain dental services commonly needed by consumers, such as periodontal treatment for gum disease. In addition, under the current Denti‑Cal payment structure, which pays dentists by the procedure, providers have an incentive to maximize the number of patients they see each day. This works against what is often the consumer requirement for additional appointments and time to receive dental services. Many consumers, for example, are unaccustomed to seeing the dentist and might require behavioral desensitization—methods that help put a patient at ease before a dental procedure. These methods often require additional time and visits.

RCs and DDS Have Taken Steps to Address Consumers’ Dental Needs, Yet Access Remains a Problem. Over the past couple of decades, DDS and RCs have taken steps to address the access problem. Currently, 17 of 21 RCs employ a dental coordinator whose responsibilities include expanding the network of dental providers willing to serve DDS consumers, helping providers with Denti‑Cal administration, conducting consumer case reviews, helping individual consumers find providers, training consumers and residential care providers on oral hygiene, and coordinating desensitization. The RCs without a dental coordinator serve areas with some of the worst access to Denti‑Cal providers. DDS has also targeted state funding provided for community resource development to projects proposed by RCs to expand access to dental care, such as development of clinic‑based services that can accommodate DDS consumers. While these actions have helped to improve consumer access, consumer access remains a significant problem, as evidenced by Denti‑Cal data.

Recommendations

We make several recommendations, based on our three key assessments, to improve consumers’ access to dental care:

Assessment—Dental Coordination at RCs Effective, but Currently Insufficient in its Use Statewide:

- Require the administration to submit a plan to the Legislature to increase the number of dental coordinators at RCs statewide. The administration should consider using DDS’ existing community resource development funds to fully or partially support the plan.

Assessment—Denti‑Cal Benefit and Rate Structure Limits DDS Consumers’ Access:

- Authorize behavior management benefit for DDS consumers eligible for Denti‑Cal.

- Improve access to periodontal treatment for DDS consumers eligible for Denti‑Cal:

- Modify or eliminate the current treatment authorization request requirement for scaling and root planing benefit for DDS consumers.

- Modify or eliminate the limit on periodontal maintenance for DDS consumers.

- Restore the prior Denti‑Cal rate for periodontal maintenance.

Assessment—Too Few Dental Providers Willing and Able to Serve Consumers:

- Consider authorizing a pilot program that would provide a supplemental payment to Denti‑Cal providers who have undergone training to treat DDS consumers.

- Expand RDHAPs’ scope of practice.

- Consider requiring the administration to submit a plan targeting the use of DDS’ community resource development funds to develop additional dental resources. Potential components of the plan might include:

- Increasing dental coordination at RCs, as noted above.

- Increasing service provision at clinics, such as federally qualified health centers.

- Increasing the number of VDHs.

- Consider providing incentives for dentists to practice house‑call dentistry.

Introduction

Individuals with developmental disabilities face a number of behavioral, cognitive, and physical challenges that can adversely affect their health. Oral health is no exception. Many individuals with developmental disabilities cannot personally maintain their own dental hygiene and suffer poor oral health outcomes, such as decaying teeth and gum disease, as a result. Under state law, individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities can receive dental services paid for by the state, but often they need extra appointments or special accommodations that dentists are unable or unwilling to provide. With the scheduled closure of the state’s three remaining state‑run institutions for individuals with developmental disabilities—known as Developmental Centers (DCs)—and the accompanying transition of DC residents into the community, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) is funding the development of new community resources to address the service needs of those formerly institutionalized. The staff of the Regional Centers (RCs)—which oversee the provision of services in the community—have indicated that dental services are a pressing need among their consumers living in the community. Research has highlighted disproportionately high rates of dental disease and tooth decay among individuals with developmental disabilities and has noted that these individuals are more likely than the general population to lack access to regular dental care across their lifespan. This report analyzes the extent to which dental services for individuals with developmental disabilities are available and sufficient in their communities. Finding that access challenges exist, we consider options for improving access to dental services for this population. (There are several acronyms used in this report. We provide a list of them, with definitions, as an appendix to the report.)

Background

Overview of Developmental Services

Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act of 1969 (the “Lanterman Act”). Under the Lanterman Act, the state provides individuals who have developmental disabilities with services and supports to meet their needs, preferences, and goals in the least restrictive environment possible. These services and supports are overseen by DDS. The Lanterman Act defines a developmental disability as a “substantial disability” that starts before the age of 18 and is expected to continue indefinitely. This definition includes cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities that require similar treatment (such as traumatic brain injury). Unlike most other public human services or health services programs, individuals receiving services through DDS need not meet any income criteria. Rather, the main qualification criterion is diagnosis of a substantial lifelong developmental disability. The department administers both community‑based services and state‑run services. These are each described below.

Community Services Program. In 2017‑18, DDS served an estimated 320,000 individuals with developmental disabilities (“consumers” in statutory language) through its community services program. Twenty‑one independent nonprofit RC agencies coordinate services for consumers, which includes assessing eligibility and developing individual program plans (IPPs). Consumers receiving community services can be divided into two broad groups:

- Infants and Toddlers. For infants and toddlers under the age of three who exhibit a developmental delay (it is often unclear at this age whether the delay reflects a lifelong developmental disability), RCs coordinate a more limited set of services (such as early intervention services and speech, occupational, and physical therapies) through the Early Start program. RCs currently serve approximately 42,000 infants and toddlers in the Early Start program.

- “Active Status” Consumers. Active status consumers are ages three and older and have been deemed eligible for lifelong services under the Lanterman Act. DDS currently serves approximately 279,000 active status consumers, with caseload increasing about 4 percent annually in recent years.

Because RCs do not necessarily coordinate dental care for infants and toddlers, this report focuses on active status consumers (including DC residents moving into the community) and will simply use the term consumers throughout to refer to this group.

RCs coordinate residential, health, day program, employment, transportation, and respite services, among others, for consumers. As the mandated payer of last resort, RCs only pay for services if they are not covered and paid for through another government program, such as Medi‑Cal, or through a third party, such as private health insurance. RCs contract with tens of thousands of vendors around the state to purchase services and supports for consumers. DDS provides RCs with a budget for both their administrative operations and the purchase of services (POS) from vendors.

DCs Program. At the start of 2017‑18, DDS served about 800 individuals in three DCs, which are licensed and certified as general acute care hospitals, and in one state‑run community facility. These state‑run facilities can be divided into two broad groups:

- Closure DCs. In 2015, the administration announced its plan—which the Legislature approved—to close the state’s remaining DCs (which we refer to as “closure DCs”)—Sonoma DC in Sonoma County by the end of 2018, Fairview DC in Orange County by the end of 2021, and the general treatment area of Porterville DC in Tulare County by the end of 2021. (At one time, the state operated seven DCs serving upwards of 13,000 consumers. It closed four DCs between 1996 and 2015; most of those residents now live in the community.) At the start of 2017‑18, 534 residents lived at closure DCs and by the end of 2017‑18, 240 consumers remained. Once individuals move from DCs into the community, they receive services as active status consumers through the community services program.

- Nonclosure Facilities. DDS will continue to operate a secure treatment program at Porterville DC, which serves individuals committed by a court because they are a safety risk to themselves or others and/or have been deemed incompetent to stand trial for an alleged criminal offense. By statute, Porterville DC’s secure treatment program can serve up to 211 people. DDS will also continue to run Canyon Springs Community Facility in Riverside County, which can house up to 63 people at a time, many of whom have recently left Porterville DC’s secure treatment program.

Characteristics That Can Affect the Oral Health of Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

Individuals with developmental disabilities may have one or more characteristics that complicate their oral health and make receiving dental treatments more difficult, especially under traditional models of care. Below, we describe some of these characteristics. Later in the report, we discuss how these characteristics complicate oral health and dental care.

Cognitive Challenges. According to December 2017 data collected by DDS, about six in ten consumers have an intellectual disability. Eight percent have an intellectual disability that is considered severe or profound (as opposed to moderate or mild). Former DC residents have even higher rates of cognitive disability. According to a May 2016 “Risk Management Report” prepared for DDS about individuals who moved from DCs between 2010 and 2014, 70 percent have an intellectual disability that is severe (15 percent) or profound (55 percent).

Behavioral Challenges. Some individuals with developmental disabilities also have mental health diagnoses, including 47 percent of former DC residents. According to the 2014‑15 National Core Indicators (NCI) Survey, 7 percent of California’s DDS consumers ages three through 18 have mental illness or a psychiatric disorder. As shown in Figure 1, the percentages are even higher for adults.

Figure 1

Many Adults With Developmental Disabilities Have Behavioral and/or Mental Health Challenges

National Core Indicators, Adult Consumer Survey, California Statewide Report, 2014‑15

|

Additional Challenge Beyond Developmental Disabilitya |

Percent |

|

Behavioral challenges |

29% |

|

Anxiety disorder |

25 |

|

Mood disorder |

24 |

|

Psychotic disorder |

9 |

|

Take Medications |

|

|

Take medications for mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders, or for other mental illness |

35 |

|

Take medications for behavioral challenges |

24 |

|

aIndividuals may have more than one challenge or disorder. |

|

These and other challenges for individuals with developmental disabilities can result in the need for supports in the activities of daily living. Nearly eight in ten children need extensive (30 percent) or some (48 percent) support to manage and prevent self‑injurious, disruptive, and/or destructive behaviors. Figure 2 shows the percentages of adults in need of such supports.

Figure 2

Behavioral Challenges Among Adults With Developmental Disabilities Result in Need for Supports

National Core Indicators, Adult Consumer Survey, California Statewide Report, 2014‑15

|

Require Supporta to Manage . . . |

Require Some Support |

Require Extensive Support |

Total Requiring Support |

|

Disruptive behaviors |

29% |

14% |

43% |

|

Destructive behaviors |

22 |

6 |

28 |

|

Self‑injurious behaviors |

17 |

3 |

20 |

|

aIndividuals may require support for more than one reason. |

|||

Other Physical and Communication Challenges. One‑quarter of adults with developmental disabilities cannot move without aides, such as wheelchairs. Many consumers also have difficulty communicating or require multilingual service providers. For example, 30 percent of adult consumers (and 18 percent of children) use gestures rather than spoken language, and for nearly 20 percent of adult consumers and children, English is not their primary language.

Identification and Coordination of Consumers’ Dental Service Needs

How Dental Needs Are Identified. Consumers’ dental needs are identified through the IPP process, which includes participation by the consumer, his or her family (if applicable), his or her RC service coordinator, and any other relevant individuals, such as RC clinical staff or service provider staff. In addition to identifying the goals, objectives, and preferences of the consumer, the IPP planning team identifies and documents the services and supports the consumer may need to live in the least restrictive and most integrated way possible. Such services and supports may include residential, day program, employment, dental, medical, or therapeutic services, or respite for caregivers. While the IPP is reviewed at least once every three years, progress toward the goals and objectives in the IPP is tracked at least annually for consumers who live with their families and at least quarterly for those who live outside the family home. These regular progress reports track dental and medical appointments and current medications, although this information currently is not aggregated, which limits the ability to understand outcomes across the DDS population. (See the nearby box for more information about where DDS consumers live and how this location affects coordination of dental care.)

Where Do Individuals With Developmental Disabilities Live?

Where consumers of the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) live affects how they receive dental services and how their dental services are coordinated. The information below provides an overview of the various settings in which DDS consumers live and how dental services are coordinated in each setting. Regardless of setting, Regional Center (RC) staff may be involved in assisting consumers and their families or caregivers find dentists, make referrals, conduct patient screenings, or review patient case files.

- Consumer’s Family Home. About three‑quarters of DDS consumers live in the home of their parent or guardian. The parent or guardian is often involved in the coordination of dental services and in taking the consumer to appointments.

- Independent Living Services (ILS) or Supported Living Services (SLS). Nearly 10 percent of DDS consumers live on their own, in a home or apartment they rent or own, and receive ILS or SLS. (ILS can also be provided to someone who lives in his or her family’s home.) ILS is for consumers who need training to learn functional skills to live on their own, whereas SLS is for consumers who need assistance with daily functions. SLS may include helping the consumer find an apartment, choosing a housemate, managing personal affairs, or tending to personal care. Because the acuity level varies widely among consumers receiving SLS, the method of coordinating and providing dental care also varies.

- Community Care Facilities (CCFs). Nearly 10 percent of DDS consumers live in CCFs, which are licensed by the Department of Social Services and have varying degrees of care and supervision provided, depending on residents’ needs. Each CCF typically houses four to six DDS consumers. Dental services and associated transportation may be coordinated by RC staff or the consumer’s family member, residential caregiver, or day program service provider.

- Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled (ICF/DDs). About 3 percent of DDS consumers live in ICF/DDs, which are medical facilities licensed by the Department of Public Health (DPH). ICF/DDs provide varying degrees of nursing care and levels of staffing (and accommodate a varying number of residents) depending on their designation. Residents living in ICF/DDs tend to have more complex medical needs than do other DDS consumers (although these needs may be similarly complex to the needs of residents living in the most intensive CCFs). Some may be unable to travel easily to a dental office and may receive basic treatments at the ICF/DD.

- Skilled Nursing Facility (SNFs). Less than 1 percent of DDS consumers (around 1,100 people at the end of December 2017) live in SNFs, which are licensed by DPH and provide 24‑hour inpatient care. SNF residents have nursing and medical needs that may be similar to residents living in the more medically intensive ICF/DDs. SNF residents may receive some of their dental treatments at the SNF and travel to a dental office or surgical center for more intensive procedures.

DDS also tracks consumer characteristics, developmental information, and consumer quality‑of‑life measures through the Client Development Evaluation Report (CDER). The CDER is completed once every one to three years and includes several questions related to dental and medical care.

How Dental Services Are Coordinated. For the roughly 550 consumers who live at DCs as of March 2018 (this number declines on a weekly basis as consumers move from DCs to the community), dental services are provided onsite by state‑employed dental staff or contracted dental providers. DCs are licensed as acute care hospitals and can administer general anesthesia onsite. For the roughly 279,000 consumers who live in the community (as of March 2018), dental services are coordinated by family members and/or by RC staff, which may include the consumer’s RC service coordinator or the RC dental coordinator, or both. We conducted a survey of the 21 RCs to learn more about their dental coordination efforts. We discuss the results of the survey as well as the role of the RC dental coordinator in more detail later in this report.

Dental Service Settings for Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

Individuals with developmental disabilities receive dental services in a variety of settings—including private dentist offices, hospital operating rooms and oral surgery centers, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and other safety net clinics, and in their own homes. Where these individuals receive services depends largely on where they live, their dental insurance (if they have insurance), their familiarity and comfort with the dentist, and the acuity of their dental needs. Typically, however, individuals with developmental disabilities receive dental services in private dentist offices.

Private Dentist Offices. Private dentist offices are typically sole proprietorships with a single dentist, one or more registered dental hygienists (RDHs), and one or more support staff including (among others) registered dental assistants (RDAs). This small office structure limits the number of patients that dentists and their staff can treat. Recent national data show that dentists treat an average of 70 patients per week. Private dentist offices also occupy relatively small office spaces with few chairs. Sole proprietorships nationwide, for example, each have an average of four chairs to serve their patients. As opposed to hospital operating rooms and oral surgery centers, the vast majority of private dental offices do not offer deep sedation or general anesthesia services.

Hospital Operating Rooms and Oral Surgery Centers. For more intensive, restorative procedures that require deep sedation and general anesthesia, patients can schedule appointments in hospital operating rooms and oral surgery centers. These facilities are equipped to provide a variety of surgeries, and their personnel can often perform multiple dental procedures in one appointment. Hospitals and oral surgery centers, however, have limited capacity to provide dental procedures relative to other surgical procedures. Limited capacity means long waiting lists—upwards of three years—for individuals with developmental disabilities to receive dental services in these facilities.

FQHCs and Other Safety Net Clinics. FQHCs and other safety net clinics provide comprehensive primary care—often including dental services—to medically underserved communities and populations. FQHCs are paid using a different payment model than other providers, one that incentivizes delivering services to more people. While this payment model may not incentivize FQHCs to serve individuals with developmental disabilities—as they often take longer to treat—two RCs are working with community health center organizations to build FQHCs with the equipment and personnel necessary to provide individuals with developmental disabilities with community‑based services.

At Home. Some individuals with developmental disabilities, particularly those who need assistance to move, receive dental services in their homes from mobile dental providers. These providers, such as Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice (RDHAPs), typically set up a dental chair and other equipment in the consumer’s home and perform dental procedures as they would in a private dentist office. There are few mobile dental providers who perform dental services in homes because of the additional cost of transportation to and from a patient’s home, the difficulty in setting up and taking down the equipment necessary to perform dental procedures, and the reduced number of patients they are able to treat.

Dental Service Delivery Approaches

Currently, most DDS consumers receive dental services through the traditional delivery approach—the same way most of the general population receives its dental services. Below, we briefly describe this approach and then several alternatives that have been developed to treat patients (including many DDS consumers) for whom the traditional approach does not meet their needs.

Traditional Service Delivery Approach. For most individuals, dental services start with the patient making an appointment at a private dentist office. The patient arrives at the office and provides the administrative assistant (or similar staff member) with relevant information (including insurance information) before the appointment begins. One of the staff members takes the patient back to a dental chair, and an RDH thoroughly cleans the patient’s teeth. Once the patient’s teeth are cleaned, the dentist performs a full examination of the teeth, gums, and mouth to check for signs of disease and decay. Should radiographs be necessary, often an RDA or RDH will take the radiographs at some point during the visit. Once all of the dental procedures are completed, the patient will be asked to go back to the administrative assistant to schedule a follow‑up appointment. Most routine, preventive dental appointments take approximately an hour, but appointments can take longer depending on the nature of the procedures performed. (Please see the nearby box for a description of the common dental procedures discussed throughout this report.)

Common Dental Procedures Discussed in This Report

Below are descriptions of some of the most common dental procedures—preventive and restorative—addressed in this report. This list does not include dental examinations and dental radiographs (another word for x‑rays), both of which are done for preventive and restorative purposes.

Preventive Procedures. Preventive procedures are one‑time or ongoing treatments that can prevent worse dental problems from developing:

- Prophylaxis. Prophylaxis is another word for cleaning, the common procedure that most children and adults undergo once or twice each year to remove plaque and tartar from the crowns of the teeth.

- Fluoride Treatments. Fluoride is a naturally occurring mineral that is applied directly to the teeth to prevent tooth decay and caries (another word for cavities). Fluoride, while present in many toothpastes and water supplies, can also be applied topically by any dental professional, including registered dental assistants.

- Sealants. Sealants are thin protective coatings applied to the biting surface of molars to prevent decay and caries.

Restorative Procedures. Restorative procedures attempt to fix a dental problem, “restoring” the tooth or gum to as healthy a state as possible:

- Fillings. Dentists use fillings, which are made of an amalgam (mercury combined with a metal), composite resin, glass ionomer, or other material, in the caries of a tooth experiencing tooth decay. The filling also prevents the decay from worsening.

- Scaling and Root Planing. Scaling and root planing are considered deep cleaning for the treatment of periodontitis (gum disease that causes inflammation and can lead to bone destruction). Scaling involves scraping plaque and calculus from the tooth surface and from under the gum line. Root planing involves scraping and smoothing the roots of the teeth.

- Periodontal Maintenance. Periodontal maintenance is like prophylaxis for patients who have periodontitis and have first undergone scaling and root planing. Whereas prophylaxis treats the crowns of the teeth, periodontal maintenance also treats the roots and gums.

- Interim Therapeutic Restoration (ITR). ITR involves placing a fluoride‑releasing glass ionomer on a tooth to prevent further progression of a caries. ITR does not require the use of a local anesthetic (like filling a caries does) and is often used for hard‑to‑serve populations or as a stabilization method until additional restoration can be completed.

Alternative Service Delivery Approaches. The state has developed and/or piloted several alternative ways of delivering dental care to reach Californians (including DDS consumers) who may have problems receiving dental services the traditional way, whether due to location; income; or physical, cognitive, or mental health. Below, we describe several of these:

- RDHAPs. Statute authorized the RDHAP licensure type in the late 1990s to serve homebound and/or medically compromised patients. RDHAPs are RDHs who also hold a Bachelor of Science degree, complete a certificate program, pass a written exam, and have about one or more years of experience. The license allows RDHAPs to practice in community settings—such as schools, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled (ICF/DDs), patient homes, their own offices, and in identified dental health professional shortage areas—without a dentist’s or physician’s direct supervision. (A dental health professional shortage area is an area designated by the federal government as not having enough dentists to adequately serve the population.) They perform the same services as RDHs (including prophylaxis, scaling and root planing, periodontal maintenance, application of sealants and interim therapeutic restorations (ITRs), and the taking of impressions), but can perform them in nontraditional settings. RDHAPs can also determine which radiographs are needed by a supervising dentist to develop a subsequent treatment plan. For up to 18 months, an RDHAP may treat (but not diagnose) a patient who has not been examined by a dentist or physician. After 18 months, the RDHAP must provide documentation that such an examination occurred and obtain a written prescription (valid for up to two years) from the dentist to treat the patient. RDHAPs may independently submit insurance claims to receive payment for their services. Currently, 507 RDHAPs are licensed to practice in California and 191 are enrolled as Medi‑Cal dental program (“Denti‑Cal”) providers. Most travel to provide dental hygiene services—for example, to patients in their homes and at SNFs and ICF/DDs. A 2009 study of California RDHAPs estimated that 30 percent of RDHAP patients had a developmental disability. In the same study, nearly half of RDHAPs reported having difficulty finding dentists to accept their referrals after the 18‑month window.

- Virtual Dental Homes (VDHs). The VDH delivery approach delivers dental services in community‑based settings, rather than in traditional dental offices, to serve patients where they are—for example, in schools, Head Start programs, residential facilities, or private homes. VDHs promote early intervention and prevention services by RDHs under the general supervision of a licensed dentist (who need not be physically present). RDHs provide education, as well as preventive and simple therapeutic services, and collect dental charts as well as dental and medical histories of patients. RDHs then confer with partnering dentists through teledentistry technology about the patient’s condition, course of treatment, and any necessary referrals. Pilot projects between 2010 and 2016 demonstrated that underserved and vulnerable populations could be successfully treated using the VDH delivery approach.

- Dentists Providing Services in Homes or Schools. Another alternative delivery approach—while not formalized as a program—is for dentists themselves to travel into the community to see patients in their homes, other residential facilities, or at schools.

- DCs. As discussed earlier, DDS consumers who still live at DCs receive their care, including treatment performed under general anesthesia, onsite from state‑employed or state‑contracted dental providers. Although this approach has been convenient for DC residents, and ensured at least some degree of dental care, the three remaining DCs will be closed by 2021 (except for the secure treatment program at Porterville DC).

Paying for Dental Services for Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

RC Consumers Must Access Their Insurance. Before an RC can use its POS funds to purchase dental services identified in a consumer’s IPP, state law requires RCs to exhaust benefits from all other available resources, including publicly funded or private insurance programs. To demonstrate that they have exhausted their benefits, RC consumers who are eligible for Denti‑Cal or some other form of dental insurance (that is, through Medicare, employer‑sponsored insurance, or other private insurance) must first attempt to receive dental services from a participating provider and be denied. For example, an insurer might deny coverage because the service is not a covered benefit or the patient has already reached his or her maximum annual number of allowed services or maximum annual dollar amount. Consumers must then provide their RC with documentation of the service denial and receive a determination from their RC that an appeal of the service denial does not have merit.

Denti‑Cal. Medi‑Cal beneficiaries can receive all currently authorized dental services through Denti‑Cal. A vast majority of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries receive dental services through the fee‑for‑service (FFS) delivery system, although all beneficiaries in Sacramento County and some beneficiaries in Los Angeles County receive dental services through a dental managed care plan. Nearly eight in ten RC consumers are income‑eligible for dental insurance through Denti‑Cal. The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) generally determines which dental benefits are covered by Denti‑Cal, what rates are set for each benefit, and how often Denti‑Cal providers can bill for a particular service for a particular patient. DHCS also determines which dental procedures require prior authorization, meaning a Denti‑Cal provider must document the medical necessity of the service (often with radiographs or photographs) and submit this documentation in the form of a Treatment Authorization Request (TAR) to Denti‑Cal before performing the procedure. If DHCS denies the TAR and the RC determines that an appeal of the denial does not have merit, the RC can then decide whether or not to use its POS funds to pay for the denied service.

Several recent legislative policy and budget changes have affected the Denti‑Cal program. Chapter 662 of 2014 (AB 1174, Bocanegra) allows dentists enrolled in Denti‑Cal to bill for virtual consultations provided through teledentistry. This change means that Denti‑Cal beneficiaries can receive dental services through VDHs. The 2017‑18 budget increased Denti‑Cal rates for certain services and fully restored adult dental benefits that were cut during the recession. The 2018‑19 budget both maintained the 2017‑18 rate increases and increased rates for additional dental services. It also added a provision allowing dentists to bill for additional time to treat patients with special needs, but it is still unclear how DHCS will implement this new provision. Finally, the 2018‑19 budget increased the rates paid through Denti‑Cal for general anesthesia and intravenous sedation in a dental setting to match the rates paid through Medi‑Cal for equivalent services in a medical setting.

RC POS. As the payer of last resort, RCs only pay for dental services with POS funds when insurance (Denti‑Cal or some other form of dental insurance) has denied coverage or falls short of covering a needed treatment, a Denti‑Cal provider cannot be found, or someone does not have dental insurance but requires a treatment. An RC can pay for the service with POS funds, but only up to the rate established by Denti‑Cal for the same procedure. If a needed service is not a Denti‑Cal benefit or the situation is an emergency and the RC cannot find a provider willing to accept a Denti‑Cal rate, in rare circumstances, the RC may negotiate a rate with a dentist for treatment.

In 2016‑17, RCs spent $3.7 million for the dental services of 6,000 consumers (about 2.3 percent of consumers), for an average per‑person expenditure of $613. In addition, RCs spent some POS funding in a service category called “specialized therapeutic services” ($10 million in POS expenditures on about 3,500 consumers in 2016‑17). These services could include special supports related to dental care, but because the expenditure data is not more specific, it is unclear what share of the expenditures is for this purpose.

DDS Consumers Experience Problems With Oral Health and Access to Dental Care

The oral health of individuals with developmental disabilities is worse on average than the oral health of the general population on several key factors. For example, they have higher rates and increased severity of periodontal disease, much higher rates of untreated caries, and more missing and decaying teeth. (One study in Massachusetts found that patients with developmental disabilities average 6.7 missing teeth, whereas the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate the general population averages 3.6 missing teeth.) Compared to the general population, patients with developmental disabilities are more likely to have missing teeth than to have teeth with fillings. This could be due, for example, to situations where their decaying teeth are more likely to be extracted than restored with fillings. Some oral health problems stem directly from the particular disability itself. For example, mouth breathing among individuals with Down syndrome can lead to a dry mouth, which makes it more difficult to wash away bacteria and can result in increased risk of gum disease.

The Characteristics of a Developmental Disability Can Compound Oral Hygiene Problems . . . The cognitive, behavioral, physical, and/or communication challenges experienced by many individuals with developmental disabilities affect their ability to practice good oral hygiene and to receive dental treatment. At home, a consumer may be physically unable to brush and floss his or her teeth, may struggle to comprehend self‑care instructions, or may resist allowing someone else to brush his or her teeth. At the dental office, a consumer may struggle with severe anxiety, be unable to use traditional dental chairs, or lack the ability to hold his or her mouth open or control his or her movements. A consumer may also struggle to describe symptoms or identify a problem.

. . . Leading to the Need for More Intensive Dental Service Needs. For some DDS consumers, dental treatments require extra appointments or longer appointment times because the patient needs extra time to alleviate anxiety or because the dentist cannot work as quickly as he or she would with another patient. Patients with developmental disabilities may need additional supports at appointments, such as special accommodations or behavior desensitization. A sizeable minority of DDS consumers require general anesthesia or intravenous sedation to undergo even routine dental treatments. General anesthesia often requires the use of an operating room in a hospital or surgical center, yet the wait time for such facilities can be lengthy—sometimes as long as three years. All these factors can reduce the amount of regular preventive care received. Resulting delays in access can worsen what might have been a small dental problem to start.

Because many patients with developmental disabilities suffer distinct oral health problems, cannot easily comply with home care guidelines, and often lack adequate preventive care, they can end up requiring more extensive treatments (such as a higher than average number of fillings) and/or intensive treatments (such as extractions or scaling and root planing) than they would have otherwise. To avoid extensive treatment, dentists will sometimes resort to extracting all the teeth and providing a full set of dentures. Some dentists, especially those who are less experienced in working with patients with developmental disabilities, will resort to using general anesthesia, rather than providing behavioral supports. (Given the lack of data available on this latter point, it is unclear whether or not deep sedation is overused on patients with developmental disabilities.)

Many Consumers Lack Routine Dental Care

To understand whether or not DDS consumers receive regular dental care, we turned to three available sources of data—(1) information about utilization via Denti‑Cal insurance claims for DDS consumers, (2) information reported by each consumer (and/or his or her family member or caregiver) via the CDER evaluation survey, and (3) information reported by a sample of adult consumers (and/or their family members or caregivers) in the NCI survey.

Available Denti‑Cal Claims Data Indicate That a Majority of DDS Consumers Fail to See a Dentist Each Year. As previously mentioned, nearly eight in ten DDS consumers are eligible for Denti‑Cal. According to Denti‑Cal data, however, only about 22 percent of DDS consumers enrolled in Denti‑Cal received a dental service in each of 2014, 2015, and 2016. By contrast, about 32 percent of Denti‑Cal beneficiaries overall utilized dental services in each of those years, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

RC Consumers Receive Fewer Dental Services in Denti‑Cal Than Beneficiaries Overall

|

Calendar Year |

Dental Service Utilizationa |

||

|

RC Consumers |

Denti‑Cal Beneficiariesb |

Difference (Percentage Point) |

|

|

2014 |

23% |

33% |

‑10 |

|

2015 |

22 |

33 |

‑11 |

|

2016 |

21 |

31 |

‑10 |

|

Average |

22% |

32% |

‑10 |

|

aDental service utilization calculated as the percentage of beneficiaries who receive any dental procedure during the calendar year. bExcludes Medi‑Cal beneficiaries enrolled in dental managed care plans due to data limitations. Available utilization data suggest no more than a 0.5 percentage point change in utilization if included. RC = Regional Center. |

|||

Self‑Reported Survey Data Appear to Vastly Overstate DDS Consumers’ Dental Care. The CDER and NCI surveys are based on data self‑reported by surveyed consumers. Recent responses reported in the CDER survey indicate that 77 percent of consumers saw a dentist in the past 12 months. Results from the 2014‑15 NCI Survey are similar—76 percent of adult consumers reported seeing a dentist in the prior year. Based on what we know about Denti‑Cal claims—actual data—it appears that survey data vastly overstates the share of consumers receiving dental care in a given year. (Even if we assume that all DDS consumers who have private dental insurance or no dental insurance received dental care and add that number of consumers to the number of consumers who had a Denti‑Cal claim, it still means that about 40 percent—at most—received even one dental service in a year’s time.) Accordingly, this finding suggests that CDER and NCI self‑reported data may not be reliable gauges of whether dental care for consumers is adequate. It also suggests more generally that this type of survey data may not be the best source of information on which to base decisions about dental programs or policies.

RCs Have Difficulty Finding Dental Service Providers

Finding Providers With Capacity to Treat Individuals With Developmental Disabilities Is Difficult. Dentists and dental hygienists receive limited training in school and through continuing education courses on how to serve individuals with developmental disabilities. For example, although the Commission on Dental Accreditation requires that dental schools teach students how to assess patients with “special needs” (including developmental disabilities), recent survey data show that the vast majority of respondents (associate deans, department chairs, and clinic directors) believed students needed more time on this topic. Optional advanced dental education programs, such as general practice residencies, offer dentists additional clinical experience working with special needs patients, yet only 30 percent of graduates enroll in one of these programs. Finally, although the Dental Board of California’s (DBC’s) regulations on continuing education suggest courses in dental service delivery that focus on “behavior guidance” and patient management for individuals with special needs, these courses are not required and are not offered frequently. Research shows that providers who are not taught to assess the treatment needs of special needs patients, including individuals with developmental disabilities, often lack the confidence to serve this population in the future, thereby limiting access to dental providers for this population.

We conducted a survey of the 21 RCs to learn more about their dental coordination efforts and included questions about the roles and responsibilities of their dental coordinators (if they have one), the types of dental providers their consumers see, and access challenges. In our survey, nearly one‑half of RCs reported that they are seldom or only sometimes able to coordinate care for their consumers who are hardest to treat (and most said it is very difficult to book operating rooms or surgical centers for consumers who need general anesthesia to undergo dental treatment). They said that reimbursement rates and waiting lists among those providers who accept Denti‑Cal are primary hurdles to accessing care for the hardest to treat, but some also reported that some dentists consider themselves ill‑equipped to treat DDS consumers in their office. Even among the dentists who do work with patients with developmental disabilities, RCs report that some prefer to see “high functioning” DDS consumers, not having the expertise, willingness, or time (or not having any mechanism to bill for extra time) to treat those with more complex needs.

Access Is an Even Greater Challenge for Denti‑Cal Recipients Given Low Provider Participation. In 2017, out of the approximately 46,000 dentists licensed to practice in California, only about 9,000 dentists (20 percent) were Denti‑Cal providers. Dentist participation in Denti‑Cal also varies widely by county. In San Bernardino County, for example, nearly 30 percent of dentists were Denti‑Cal providers in 2017. In at least six other counties, by comparison, there were no Denti‑Cal providers in 2017. While the number of counties without Denti‑Cal providers does change each year, the low participation rate of the state’s dentists in the program does not. Fewer Denti‑Cal providers generally means beneficiaries must wait longer for appointments, travel farther distances to see a dentist, and/or decide to forgo dental care.

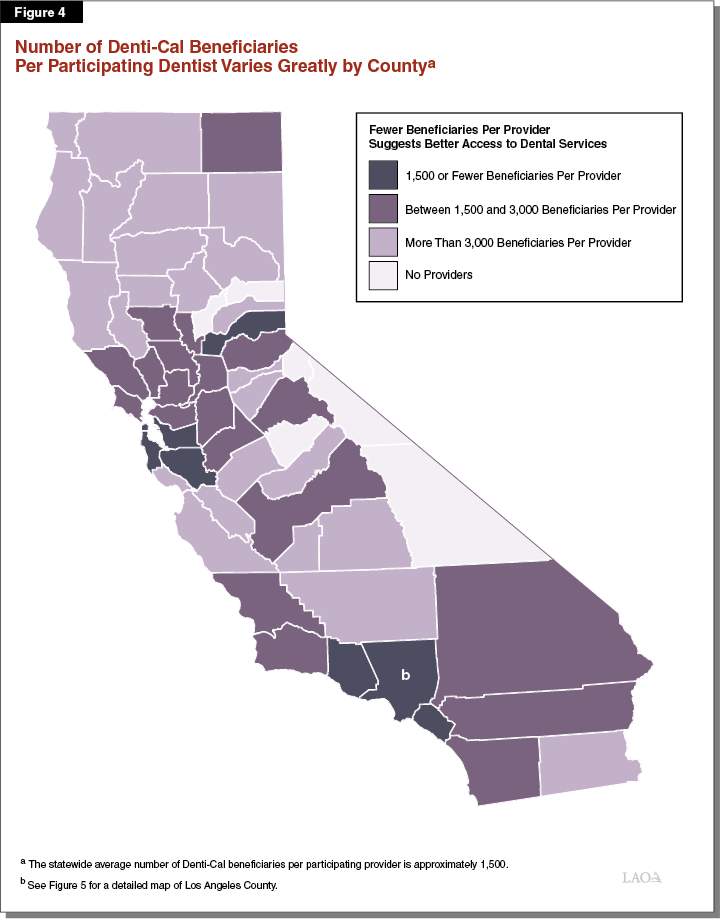

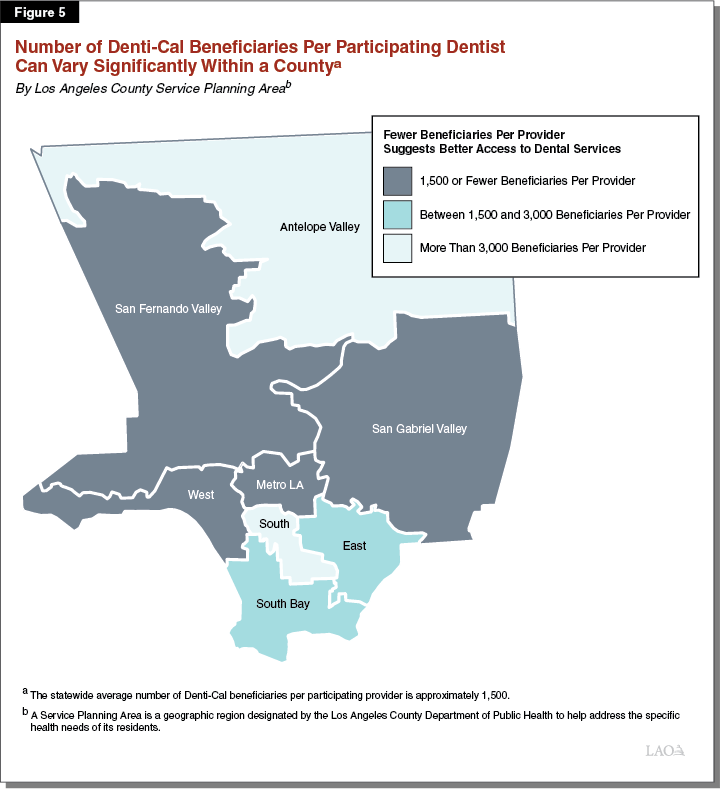

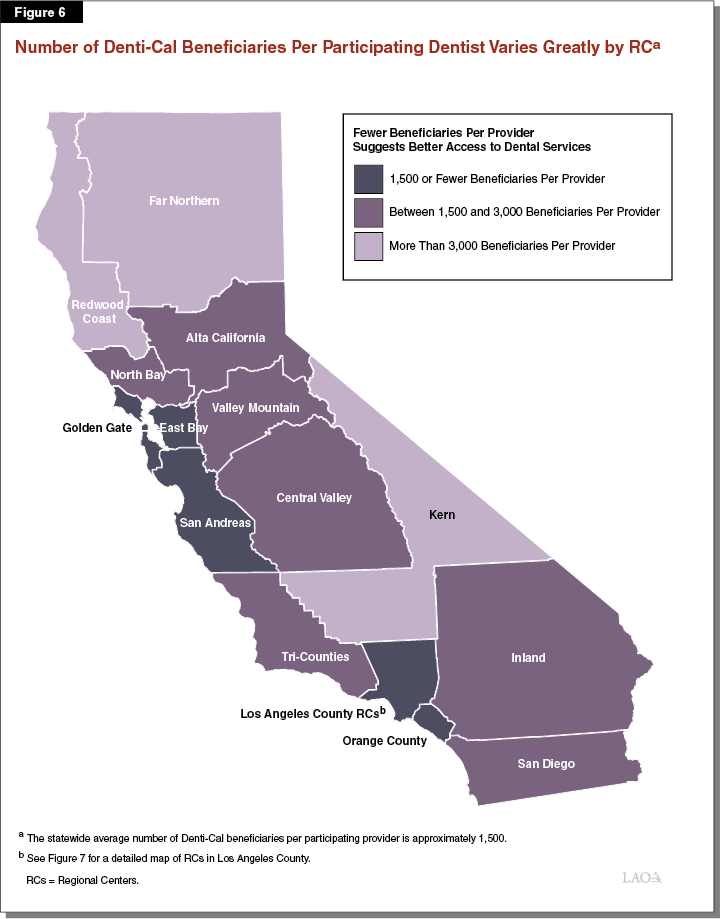

Problems With Low Denti‑Cal Provider Participation Exacerbated by Significant Increase in Number of Denti‑Cal Recipients Since 2014. While dentist participation in Denti‑Cal remains low, the number of Denti‑Cal beneficiaries overall has increased significantly due to the full implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Since 2014, an additional four million Californians have become eligible for Denti‑Cal, primarily as a result of the state’s decision to expand Medi‑Cal eligibility to all individuals under age 65 with household incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (commonly referred to as the ACA optional expansion). As a result, there was an average of 1,500 or so beneficiaries for every one Denti‑Cal provider statewide in 2017. As with dentist participation in Denti‑Cal, however, the number of Denti‑Cal beneficiaries per provider differs greatly by county, as shown in Figure 4. Even within a county, the number of Denti‑Cal beneficiaries per provider can vary greatly by county region, as shown in Figure 5 for Los Angeles County.

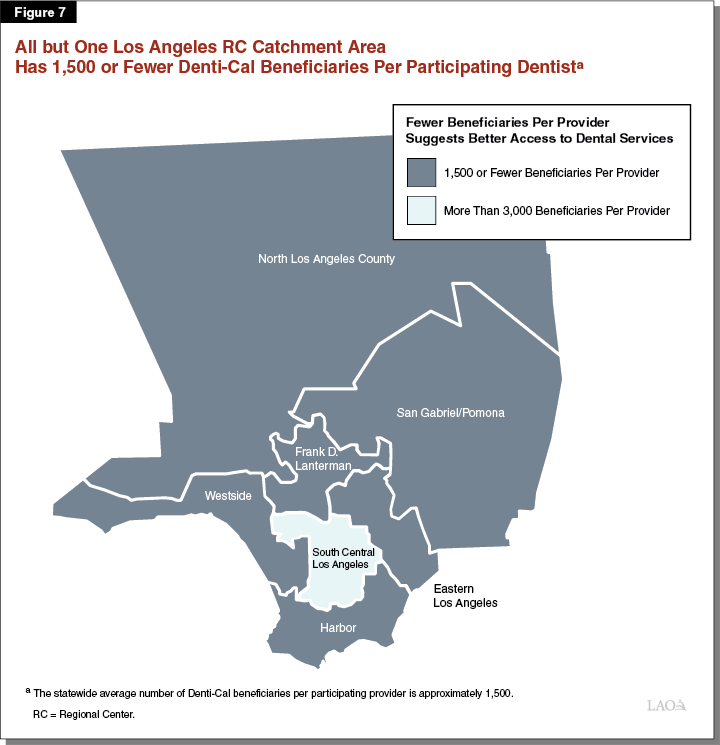

High beneficiary‑provider ratios in many of California’s counties translates into high ratios in some RC catchment areas, as shown in Figure 6. In fact, four RC catchment areas had a beneficiary‑provider ratio at least twice the Denti‑Cal statewide average, one of which is in Los Angeles County, as shown in Figure 7.

RCs and DDS Have Taken Steps to Address Consumers’ Dental Needs

Recognizing that oral health and access to dental care are problems for many individuals with developmental disabilities, DDS and individual RCs have taken certain steps over the past two decades to address these issues.

Use of Dental Coordinators

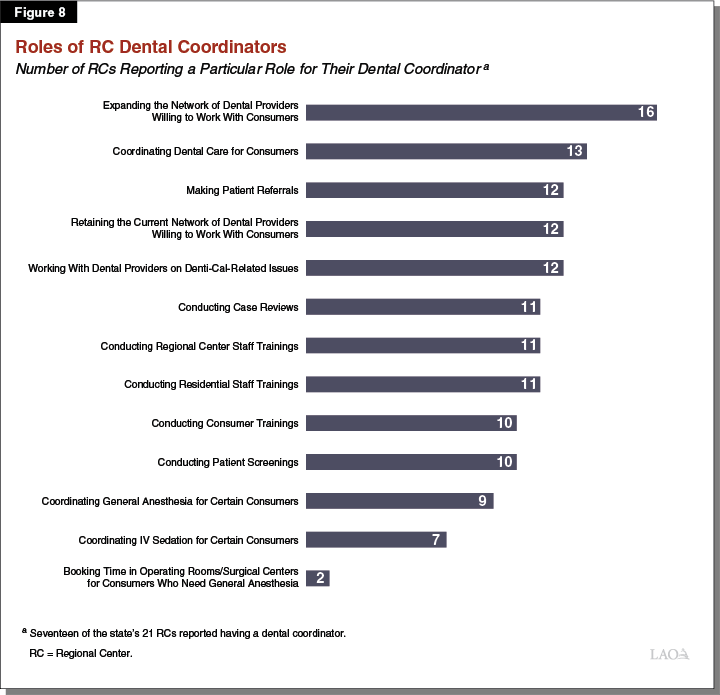

Most RCs Have Hired Dental Coordinators. In addition to having service coordinators who work with consumers and their families to develop and fulfill the overall objectives of a consumer’s IPP, RCs also have clinical staff who handle issues related specifically to the medical and dental care of the consumer population, including on an individual consumer basis. In our survey of the 21 RCs, 17 reported that they also employ one or more dental coordinators. Fourteen RCs have one dental coordinator position and three RCs have two positions (although at two of these three RCs, the total number of hours worked between the two dental coordinators is still less than one full‑time position). Four RCs do not have a dental coordinator. Most of the RC dental coordinators have worked with their RC for at least five years (the average length of employment is ten years) and the primary responsibilities of the dental coordinator position appear similar across RCs. For example, 16 RCs report that expanding the network of dental providers willing to work with DDS consumers is a core responsibility of their dental coordinator(s). More than one‑half of the RCs indicated that their dental coordinators work with dental providers on Denti‑Cal‑related issues. Figure 8 shows the various roles of a dental coordinator and the number of RCs that report each role is a primary responsibility of their dental coordinator(s).

Hiring Dental Coordinators Is Up to the Discretion of RCs. RCs’ budgets include funding for both POS as well as for RCs’ own operating costs, such as hiring service coordinators. DDS determines an RC’s total budget for operating costs using a formula, based primarily on the number of consumers served by that RC. DDS requires and funds RCs to have certain positions, while other positions are not necessarily required—for example, certain specifically identified administrative positions—but are funded by DDS. Funding amounts for RC positions are based on salary levels in the formula set by DDS. The salaries used in the formula to calculate an RC’s budget for operating costs, however, have not been updated for many years. If an RC identifies a priority that is neither required nor funded by the formula, such as dental coordination, it consequently must choose to forgo other positions or reduce other salaries in order to pay for dental coordination. It might be increasingly difficult for RCs to shuffle their budgets in this manner, however, as salary levels in the formula become increasingly outdated. Currently, to recruit and retain service coordinators, for example, nearly all RCs already pay higher salaries than what the formula provides.

Many RCs Report Hiring RDHAPs as Dental Coordinators. Our survey of RCs found that out of the 20 dental coordinators currently employed, half are RDHAPs. (Of the remainder, two are dentists, three are RDAs, three are RDHs, one is a registered nurse, and one has a Bachelor of Science degree and many years working in a dental office.) RCs report hiring RDHAPs as dental coordinators for at least two reasons—RDHAPs are familiar with the dental service needs of RC consumers because of serving patients with similar needs in residential settings or institutional settings such as SNFs, and RDHAPs are often familiar with administrative processes in Denti‑Cal. As dental coordinators, RDHAPs can help RC consumers eligible for Denti‑Cal access their insurance and can recruit additional providers for Denti‑Cal within an RC’s catchment area.

RCs Increasingly Rely on RDHAPs to Provide Dental Services to DDS Consumers

As RCs have had difficulty finding dentists who are able or willing to serve individuals with developmental disabilities, RCs have increasingly looked to RDHAPs to provide their consumers with dental services. This trend among RCs is largely explained by RDHAPs being more likely to accept Denti‑Cal (discussed further below), and being more familiar with the dental service needs of RC consumers because of their work with homebound patients or patients residing in institutional settings such as SNFs.

RDHAPs Are Twice as Likely as Dentists to Accept Denti‑Cal. In 2015, Denti‑Cal allowed RDHAPs to enroll in the Denti‑Cal program as providers who could perform a range of services without the direct supervision of a dentist. (While RDHAPs still need a dentist to diagnose the patient and prescribe treatment, RDHAPs can provide specified services and bill Denti‑Cal on their own.) By 2017, about 40 percent of the state’s 507 RDHAPs had enrolled in Denti‑Cal, a participation rate twice that of dentists. One primary reason RDHAPs are more willing than dentists to accept Denti‑Cal is that they are better able to operate within the program’s reimbursement rates—rates that are the same for dentists and RDHAPs for the same service. Whereas dentists cite these reimbursement rates as too low and thus one of the primary reasons they do not participate in Denti‑Cal, RDHAPs have been largely able and willing to work within the current rate structure. As we discuss later, however, recent changes to administrative requirements for the services RDHAPs can provide, as well as reductions in the reimbursement rates for some of those services, might reduce their participation in the program going forward.

DDS Has Awarded Community Placement Plan Funding to Develop Dental Resources

About two decades ago, the Legislature and Governor approved a special annual appropriation for DDS for community placement plan (CPP) activities. DDS uses CPP funding to pay for the transitional costs associated with moving consumers from DCs into the community. It allows DDS to fund the development of new housing and nonresidential programs in the community to meet the needs of former DC residents, who tend to have more complex medical and behavioral needs than the average DDS consumer already living in the community.

After conducting comprehensive individual assessments of DC residents, RCs submit proposals to DDS for the development of new or expanded residential and nonresidential services and supports. Through the annual CPP, DDS funds many of these proposals. The state budget currently allocates about $50 million of base funding annually for CPP. In recent years, CPP funding has been used for six dental projects in response to the needs of consumers moving out of Sonoma DC, including development or expansion of clinic‑based services, dental provider training, mobile dental services, and development of specialty dental services.

Use of CPP Funds Will Be Expanded. Chapter 18 of 2017 (AB 107, Committee on Budget) authorized DDS to expand the use of CPP funds to develop services and supports for individuals already living in the community (who never lived in a DC). The “community resource development plan” funds will present another opportunity to respond to some of the dental needs of the many DDS consumers who never lived in DCs.

Allowing DC Staff to Serve Former Residents Until Closure

DDS recently authorized the medical and dental staff at closure DCs to provide services to former DC residents (who now live in the community) onsite at the DCs until they are closed. While this is only a temporary solution to the problem of access to dental care (and medical care) among former DC residents, it may provide needed services in the short term (particularly for those who require general anesthesia). Thus far, however, it is unclear how well this option has been promoted and relatively few former DC residents have utilized (or plan to utilize) these services. In addition, DDS has chosen to limit this service only to those consumers who formerly lived at a DC.

Training and Education of Consumers, Caregivers, and RC Service Coordinators

Most of the RCs that have a dental coordinator reported in our survey that a key responsibility of their dental coordinators is educating consumers, caregivers, and RC service coordinators about the importance of good oral health in consumers’ overall health. Consumers and their caregivers are also trained on consumer dental self‑care techniques. One RC told us that it even tries to educate the caregivers about their own oral health because caregivers who take good care of their own oral health tend to prioritize the oral health of consumers. A challenge noted by several RCs is the turnover among residential care staff and how often they have to train new staff on oral health (and other issues) as a result.

Analysis of Causes of The Access Problem

In spite of efforts to improve access as just discussed, the data show that access remains a problem for individuals with developmental disabilities. In this section, we first delve into the causes of the access problem, and then make recommendations on how to improve access.

Traditional Dental Care Delivery Approach Does Not Currently Meet the Needs of Many Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

A private dentist office or FQHC typically serves patients who are familiar with dental services and the environment in which they are provided, are able to physically navigate the facility, and can speak to their dentist or hygienist about their oral health. Individuals with developmental disabilities often have difficulty performing one or more of these tasks.

Many Consumers Need Desensitization. In many cases, consumers are not used to seeing the dentist and need behavioral desensitization. (See the nearby box for a description of behavioral desensitization.) Desensitization might mean the individual needs to schedule several separate appointments or request additional appointment time. How consumers receive these services, if at all, varies widely.

What Is Behavioral Desensitization?

While desensitization can refer to the medications or numbing agents taken or applied before a dental procedure, behavioral desensitization is a term used to describe methods for helping to put a patient at ease before a dental procedure. Certain dental procedures run the risk of harming either the patient or dentist if the patient is scared (for example, a patient could bite the dentist’s hand or a dental drill injuring the patient or dentist). Behavioral desensitization can play an important role in helping patients overcome these fears.

As used in this report, behavioral desensitization, or just “desensitization,” could include practice visits to a dental office or meeting the dental provider before the actual appointment takes place. It could also include mimicking the types of procedures and techniques that will take place at an appointment, such as having the patient recline in a dental chair and opening his or her mouth and having someone position a dental mirror in the patient’s mouth. In a survey we conducted of Regional Centers (RCs) and in other interviews that we conducted with providers and RC staff, several noted that many consumers lack the dental care they need because too few providers are willing to conduct desensitization (at least in part because “behavior management” is not a billable procedure through Denti‑Cal). Some RCs end up using their purchase of services funding to pay for such behavior management through a “specialized therapeutic services” code. Several RCs indicated that their dental coordinator manages and coordinates desensitization for consumers who need it.

To provide some examples of what RCs attempt to do, South Central Los Angeles RC noted in an open‑ended survey question that its dental coordinator intentionally conducts dental screenings in a comfortable and nonthreatening environment to put patients at ease. Another RC—San Gabriel/Pomona RC—developed a Dental Desensitization Clinic Program over the past two years. The program provides an initial consultation with a dentist (including a dental intake interview and behavior assessment) and practice dental sessions in a mock dental room at the RC. The mock dental room is set up to model a dentist’s office, with a dental chair and instruments. RC staff base the consumer’s number of mock sessions, and goals of the sessions, on the particular needs of that consumer. The mock sessions may include a board‑certified behavior analyst or an autism coordinator. A dentist then conducts a dental exam and assessment and makes treatment referrals to providers, as needed. The referrals are intended to help the consumer find a dental home. Thus far, five consumers have “graduated” from the program (another 15 are currently participating). These five consumers no longer need to undergo dental treatment under general anesthesia as they did in the past.

Appointments Often Take Longer. As discussed previously, the oral health of RC consumers is, on average, worse than the general population. Worse oral health means dentists and hygienists perform more intensive services on consumers, which require more appointment time. Providers might also need to help consumers work through challenges associated with their developmental disability. Dentists and hygienists traditionally are paid based on the number of procedures they perform, so any additional time they need to perform a procedure reduces the time they have to treat other patients. This disincentive likely reduces the number of dental services provided to DDS consumers.

While Some Consumers Are Homebound, Dentists Making House Calls Are Rare. Consumers with serious physical limitations require a significant amount of coordination to get to and from a facility, and to navigate it once there. Therefore, caregivers and RCs often contract with the limited number of mobile providers in their community. While the vast majority of consumers rely on Denti‑Cal for insurance coverage, current Denti‑Cal rates make it less likely that participating dentists would adopt a house‑call model of business. Making house calls would not only reduce the number of patients a dentist could see but also would require more travel, upfront investment in mobile equipment, setup of instruments and equipment at each site, and accommodation of each particular patient’s living space. While seven RCs reported in our survey that they work with at least one dentist who makes house calls, such dentists are rare.

Current Dental Coordination Resources Are Inadequate

RCs report many benefits from having a dental coordinator, including increasing access to dental care (often by expanding or sustaining the number of dental providers); conducting dental screenings; making patient referrals; and educating RC staff, families, service providers, and consumers on the importance of good oral hygiene and how to help consumers get the care they need. In addition, as noted earlier, many consumers have a severe/profound intellectual disability, have a mental health diagnosis, and/or require supports for behavioral challenges. These are likely the consumers who require additional time or special supports to undergo a dental appointment and benefit from the services provided by dental coordinators. Yet, these benefits are not readily available to some consumers in the DDS system because their RC has not hired a dental coordinator. In addition, the RCs without a dental coordinator are in some of the catchment areas with the worst access to Denti‑Cal providers.

There Are Too Few Dental Coordinators for the Number of Consumers. The four RCs without a dental coordinator serve nearly 50,000 active consumers. All four reported they would like to hire one, but cite funding constraints as preventing them from doing so. Access to dental care has become a top priority at one of these four RCs.

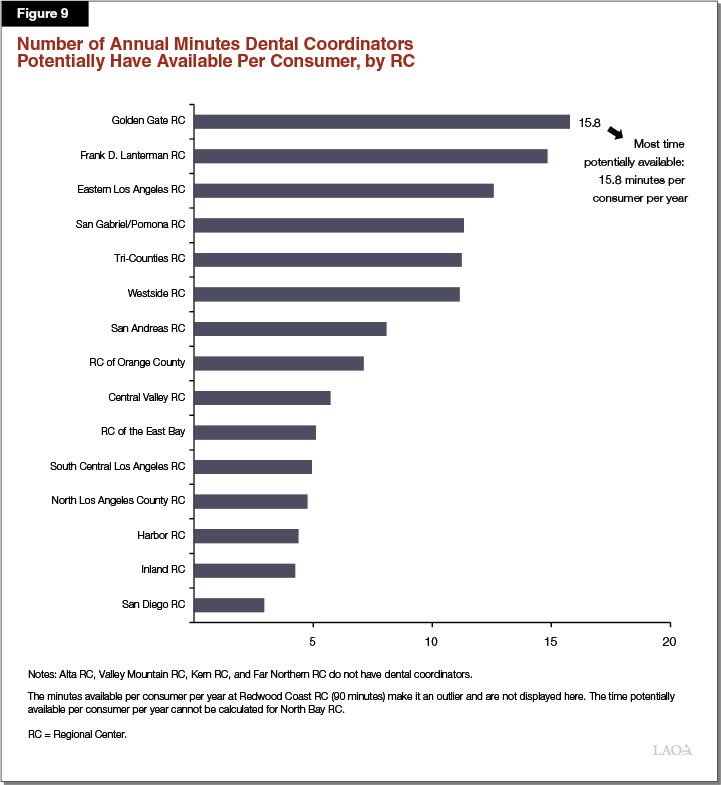

Even for the 17 RCs that report having either one or two dental coordinators (at eight RCs, the dental coordinator works part‑time), the number of potential consumers served by each coordinator varies widely across RCs. For example, across RCs, a single dental coordinator, who may only be working part‑time, serves an average of nearly 14,000 consumers, ranging from as few as 1,700 consumers to as many as 30,000 consumers. The amount of time a dental coordinator could potentially spend on each consumer’s case (this could include participating in the consumer’s IPP meeting, reviewing his or her treatment plan, conducting a dental screening, or finding a provider) similarly varies widely across RCs, as shown in Figure 9. For example, across RCs, a single dental coordinator could spend, on average, seven minutes on each consumer’s case per year, generally ranging from three minutes to 16 minutes.

While not all consumers need the services of the dental coordinator (for instance, a consumer with only a mild intellectual disability may be capable of sitting through a regular dental appointment coordinated by his or her family), the dental coordinator‑to‑consumer ratio and the average amount of time per consumer are helpful gauges in understanding the extent, adequacy of, and variation in dental coordination resources available across RCs. Taking into account the share of consumers that does not receive regular dental care, the benefits RCs report as a result of having a dental coordinator, and the minimal amount of time that a dental coordinator could potentially spend on each consumer’s case, we find that the number of dental coordinators is currently inadequate. This finding is bolstered by the fact that the RCs without any dental coordinators also serve the areas with relatively worse access to dental providers, as discussed below.

RCs Without Dental Coordinators in Areas With Relatively Worse Access. The catchment areas of the RCs that do not have a dental coordinator also happen to be among those with the worst access to dentists that accept Denti‑Cal. Three of those four RCs are also among those with the worst access to RDHAPs that accept Denti‑Cal. Figure 10 ranks RC catchment areas from best to worst in terms of consumer access to (1) dentists accepting Denti‑Cal and (2) RC dental coordinators.

Figure 10

RC Rankings on Access to Dental Providers

RCs Without a Dental Coordinator Rank Near the Bottom in Access

|

Rankingsa on Access to . . . |

||

|

Denti‑Cal Dentistsb |

RC Dental Coordinator |

|

|

RC of Orange County |

1 |

14 |

|

Westside RC |

2 |

2 |

|

Frank D. Lanterman RC |

3 |

6 |

|

San Gabriel/Pomona RC |

4 |

9 |

|

North Los Angeles County RC |

5 |

8 |

|

Harbor RC |

6 |

11 |

|

Eastern Los Angeles RC |

7 |

7 |

|

Golden Gate RC |

8 |

4 |

|

San Andreas RC |

9 |

13 |

|

RC of the East Bay |

10 |

15 |

|

San Diego RC |

11 |

16 |

|

Tri‑Counties RC |

12 |

10 |

|

Inland RC |

13 |

17 |

|

North Bay RC |

14 |

3 |

|

Alta California RCc |

15 |

— |

|

Valley Mountain RCc |

16 |

— |

|

Central Valley RC |

17 |

5 |

|

Kern RCc |

18 |

— |

|

South Central Los Angeles RC |

19 |

12 |

|

Far Northern RCc |

20 |

— |

|

Redwood Coast RC |

21 |

1d |

|

a1 = best ranking and 21 = worst ranking. bDentists accepting Denti‑Cal. cShaded rows indicate RCs without a dental coordinator. dRedwood Coast RC necessarily has the best dental coordinator‑to‑consumer‑ratio because consumer population is the smallest in the system at 3,500. It currently has two dental coordinators. RC = Regional Center. |

||

In our survey, all of the RCs with dental coordinators reported that expanding and maintaining the network of dental providers is one of the top responsibilities of the dental coordinator position. Consumers served by the RCs without dental coordinators are not only in the areas with the worst access to providers, but are at a distinct disadvantage because there is not a dental coordinator working to improve access.

In Practice, Dental Coordinators—Who Have a Limited Amount of Time Per Consumer—Have to Prioritize Administrative Tasks. Dental coordinators provide a wide range of important services at the RCs. However, some of these services are potentially more valuable than others when it comes to improving consumer outcomes. More than half of RCs reported that helping dental providers navigate Denti‑Cal‑related issues is a responsibility of their dental coordinator and five of these indicated it was a top‑three priority. This function undoubtedly increases the likelihood that a provider will work, or continue to work, with a consumer whose insurance is through Denti‑Cal. (For example, we know that some dentists will accept RC POS payments, which are based on Denti‑Cal rates, yet will not accept Denti‑Cal directly, implying that the rate alone is not the problem.) Yet, this primarily administrative task may not take full advantage of a dental coordinator’s skills and education in a way that could benefit consumers’ health outcomes, such as developing and coordinating a desensitization program.

Structure of Denti‑Cal Benefits and Rates Limits Consumers’ Access to Dental Services

RC consumers who are eligible for Denti‑Cal (the vast majority of RC consumers) have lower utilization of dental services in the program than Denti‑Cal beneficiaries overall. In addition, the structure of Denti‑Cal benefits and rates also limits the access of RC consumers to dental services, as discussed below.

Denti‑Cal Generally Does Not Pay for Additional Appointments or Time for Patients to Receive Dental Services. Denti‑Cal typically reimburses providers based on the number and types of dental procedures performed, with administrative requirements on certain services to prevent improper billing or overutilization. Additional appointments or appointment time—absent a dental procedure—have traditionally not been billable. (In 2018‑19, some tobacco tax revenues under Proposition 56 will be used to fund supplemental payments to Denti‑Cal providers for the additional time they might need to treat individuals with developmental disabilities. How these payments—which are one time for now—will be implemented, however, is uncertain at this time.) Desensitization, which often requires scheduling additional appointments or appointment time, is also not billable in Denti‑Cal. The inability of Denti‑Cal providers to bill for these services contributes to the low dental service utilization rates of consumers. It also reduces the incentives for certain providers, such as mobile dentists and dental clinics, to start practices that require additional appointment time.

Limitations on Periodontal Procedures Prevent Adequate Treatment of Periodontal Disease. After scaling and root planing, providers typically perform periodontal maintenance on patients once every three months until patients’ gums improve. In Denti‑Cal, providers generally can perform scaling and root planing once every two years, and periodontal maintenance once every three months after a scaling and root planing. (Prior to this year, periodontal maintenance was limited only to those Denti‑Cal beneficiaries living in ICF/DDs and SNFs.) There are, however, two limitations set by Denti‑Cal on scaling and root planing and periodontal maintenance that disproportionately limit consumers’ access to these services:

- Prior Authorization Requirement on Scaling and Root Planing. The first limitation is providers must submit TARs with radiographs (or, permitted recently, photographs) prior to performing this procedure. These requests often require providers to schedule two appointments: one appointment to obtain radiographs and/or photographs (and other information) in support of the request, and another appointment to perform the procedure. Many individuals with developmental disabilities—particularly those who cannot move without assistance—require a significant amount of coordination to travel to a private dental office or FQHC. In addition, providers often have difficulty obtaining radiographs or photographs from individuals with developmental disabilities because of the behavioral, cognitive, and physical challenges associated with their developmental disability. The number of appointments for a provider to perform these procedures and the difficulty obtaining radiographs or photographs from the patient both serve as barriers to these individuals accessing treatment for their gum disease.

- Two‑Year Limit on Periodontal Maintenance. The second limitation is providers can only perform periodontal maintenance for two years, after which patients are required to undergo another scaling and root planing prior to being eligible for more periodontal maintenance. Some individuals with developmental disabilities have chronic gum disease that requires periodontal maintenance for longer than two years after a scaling and root planing. Scaling and root planing also require prior authorization, whereas periodontal maintenance does not. If consumers’ gum disease does not sufficiently improve over two years, and if they are not authorized for another scaling and root planing, their oral health will deteriorate and more intensive restorative services will likely be necessary.

Many Consumers Have Difficulty Obtaining General Anesthesia and Intravenous (IV) Sedation Services in Denti‑Cal

Some DDS and RC staff estimate that between one‑fifth and one‑third of RC consumers require general anesthesia or IV sedation to undergo dental treatment. Although IV sedation and general anesthesia are covered benefits in the Medi‑Cal system, a limited number of Denti‑Cal providers offer these services in their offices and, of those who do, many are unable or unwilling to serve consumers. Alternatively, consumers can schedule appointments in hospital operating rooms or outpatient dental surgery centers that offer general anesthesia or IV sedation and accept Denti‑Cal patients. There are a limited number of these facilities statewide and, especially in hospital operating rooms, other surgical procedures are prioritized over dental services. Consumer difficulty obtaining these services not only contributes to their low utilization rates in Denti‑Cal, but also compounds oral health problems and necessitates later more expensive and time‑intensive restorative services such as teeth extraction and dentures. In addition to a lack of facilities and providers who offer these services, the treatment authorization process through Denti‑Cal FFS and Medi‑Cal managed care is also redundant and burdensome for both the providers and the consumer and his or her caregiver.

Recommendations to Improve Consumers’ Access to Dental Services

Based on our findings and assessment, we provide several recommendations for the Legislature to consider. Figure 11 provides a summary of these recommendations.

Figure 11

Summary of Recommendations

|

Issue |

Recommendation(s) |

|

Dental Coordination Effective, but Currently Insufficient in its Use Statewide |

|

|

Dental coordinators play an important role in increasing access to dental care among DDS consumers, but four RCs do not have one and many other RCs have only part‑time dental coordinators. |

|

|

Denti‑Cal Benefit and Rate Structure Limit Consumers’ Access |

|

|

Structure of Denti‑Cal benefits and rates limits consumers’ access to dental services, especially given consumers’ unique needs. DDS consumers who are eligible for Denti‑Cal use fewer dental services than Denti‑Cal beneficiaries overall. |

|

|

Too Few Dental Providers Willing and Able to Serve Consumers |

|

|

Finding dental service providers to treat DDS consumers is difficult. Many dental providers are unable or unwilling to serve consumers. Traditional delivery service approaches for dental services do not currently meet the needs of many consumers. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DDS = Department of Developmental Services; RC = Regional Center; TAR = Treatment Authorization Request; RDHAP = Registered Dental Hygienist in Alternative Practice; CPP = Community Placement Plan; CRDP = Community Resource Development Plan; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; and VDH = Virtual Dental Home. |

|

Issue: Dental Coordination Proven Effective, But Currently Insufficient in Its Use Statewide