LAO Contacts

October 15, 2018

Rethinking the 1991 Realignment

- Introduction

- The Impetus for This Report

- What is Realignment?

- Benefits and Principles of Realignment

- 1991 Realignment Basics

- 2011 Realignment

- Understanding Key Changes to 1991 Realignment

- 1991 Realignment No Longer Meets Many LAO Principles

- 1991 Realignment Likely Not Achieving Intended Benefits

- Options for Improving 1991 Realignment

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

In 1991, the Legislature shifted significant fiscal and programmatic responsibility for many health and human services programs from the state to counties—referred to as 1991 realignment. Many changes have been made to this system over the last 27 years. Most recently, the 2017‑18 Budget Act made significant changes to how the state and counties share in the cost of In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS). This report evaluates the effects of those and previous changes.

What Is Realignment? Realignments change the administrative, programmatic, and/or fiscal responsibility for programs between the state and the counties. In almost all cases, 1991 realignment increased counties’ fiscal responsibility for a wide range of programs and services including IHSS, child welfare, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), low‑income health care, and low‑income mental health services. Due in part to requirements under the State Constitution, the state provides counties dedicated revenues to pay for their share of these costs.

Realignments Should Follow Certain Principles to Achieve Intended Benefits. Realignments are intended to have long‑term benefits for counties by providing (1) greater local flexibility over programs and services based on local needs and (2) incentives to encourage counties to innovate to achieve better program outcomes. Better program outcomes also benefit the state fiscally because counties’ service improvements have the potential to reduce overall costs. Moreover, with a share of cost, counties have an incentive to control program costs in areas over which they have more control (like administration). To achieve these benefits, we believe realignments need to follow certain core principles. For example, one key principle is that realignments aim to align the state’s and counties’ share of cost based on their relative control over those programs. That is, counties’ share of cost should reflect the discretion they have over how to deliver services in the program.

Understanding Key Changes to 1991 Realignment. 1991 realignment moved in the right direction to better align county costs with their level of program control and create better fiscal incentives for counties. However, since 1991, there have been a number of programmatic and revenue changes that make it so that 1991 realignment no longer meets many of the core principles of a successful realignment. For example, both federal rules and legal decisions obligate the state and counties to provide services to anyone who meets eligibility rules for certain realigned programs—like IHSS—limiting the state’s and counties’ ability to control costs. Other policy decisions—like those affecting IHSS provider wages and federal labor rules—and increasing caseload also have made 1991 realignment more costly. While the state did not increase realignment revenues in response to these changes (or reduce counties’ share of program costs), the state did redirect revenues when realignment costs went down. For example, the Affordable Care Act significantly reduced counties’ low‑income health responsibilities. As a result, the state required counties to redirect freed‑up realignment revenues to achieve state savings.

1991 Realignment No Longer Meets Many LAO Principles. Due to the various changes to 1991 realignment programs without corresponding changes to the funding structure, 1991 realignment today no longer meets many of the core principles of a successful state‑county fiscal partnership. Today, counties’ share of some program costs exceeds their ability to control those costs. In addition, overall realignment revenues are not sufficient to cover the costs of those programs over time. Lastly, the flow of funds in realignment is extremely complex and not flexible enough to allow counties to respond to changing needs and requirements. As a result, 1991 realignment likely is not achieving the desired benefits.

Options for Improving 1991 Realignment. There are a few ways to better align the fiscal structure of 1991 realignment to achieve the intended benefits. One set of options would change the cost sharing ratios between the state and counties to better align counties’ share of costs with their ability to control those costs. Specifically, the state could reduce counties’ share of IHSS costs and increase their share of cost for another program (like felony forensic court commitments). The second set of options would better align revenue and costs by changing the flow of realignment revenue and increasing funding to address revenue shortfalls. The third set of options outlines other improvements that could be made to 1991 realignment including applying lessons from other realignments, better tracking realignment revenues and costs, encouraging counties to maintain reserves, and carefully consider future program expansion.

Introduction

California has shifted programmatic and funding responsibility between the state and counties for various programs over the last 40 years. Historically, these shifts—or realignments—aimed to benefit both the state and counties by providing greater local flexibility over services, allowing counties opportunities to innovate and improve program outcomes, and encouraging cost savings by requiring counties to share in program costs. To achieve these benefits, we believe there are certain principles any realignment needs to follow. This report evaluates the extent to which one of California’s more notable realignments undertaken in 1991 achieves the intended benefits and meets these principles.

The Impetus for This Report

Since 1991, realignment has gone through a number of structural and programmatic changes. More recently, the 2017‑18 Budget Act made significant changes to how the state and counties share in the cost of the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, the costliest social services program in 1991 realignment. Following these changes, it became clear that the funding structure of 1991 realignment could no longer fully cover county costs for certain realigned programs. Consequently, the budget agreement required the Department of Finance (DOF) to review and report on the funding structure of 1991 realignment as part of its January 2019 budget proposal.

In anticipation of the DOF report, our report outlines key historical fiscal and programmatic changes made to 1991 realignment that go beyond the new IHSS financing structure. We also discuss how these changes generally increased program costs among existing realigned programs and expanded program responsibilities within 1991 realignment. We then assess whether 1991 realignment continues to benefit the state and counties based on realignment principles we identify. Lastly, we provide the Legislature with some options to consider to improve 1991 realignment. Figure 1 provides a basic road map for the components of this report.

Figure 1

Report Road Map

|

Section |

Summary |

|

What Is Realignment? |

Provides basic background on realignment generally. |

|

Benefits and Principles of Realignment |

Outlines the intended benefits of realignments. Identifies principles we believe any realignment needs to follow in order to achieve these benefits. |

|

1991 Realignment Basics |

Describes programs affected by 1991 realignment and how funds are distributed. |

|

2011 Realignment |

Outlines overlap between 1991 and 2011 realignments. Highlights new realignment provisions included due to counties’ experience in 1991 realignment. |

|

Understanding Key Changes to 1991 Realignment |

Explains cost impacts and revenue changes to realignment since 1991. |

|

1991 Realignment No Longer Meets Many LAO Principles |

Discusses the extent to which 1991 realignment meets our principles of realignment. |

|

1991 Realignment Likely Not Achieving Intended Benefits |

Discusses the extent to which the intended benefits of 1991 realignment are being achieved. |

|

Options for Improving 1991 Realignment |

Outlines options the Legislature could consider to better align 1991 realignment with the principles and achieving the intended benefits. |

What is Realignment?

This section provides basic background on what realignment means. This section also explains some of the historical context for realignment in California due to the requirements of the State Constitution.

Realignment Refers to Changes in Program Responsibility Between the State and Counties. Counties administer most state health programs and human services programs (referred to as social services programs within 1991 realignment). Realignments change the administrative, programmatic, and/or fiscal responsibility for these programs between the state and counties. Most, realignments have shifted responsibility and resources from the state to counties. These realignments have affected responsibility for many program areas including criminal justice, health and mental health, child welfare, and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs).

State Constitution Requires Reimbursement for State‑Imposed Local Requirements. Since 1979, the State Constitution has required the state to reimburse local governments for state‑required programs and services. These are referred to as state mandates. Local governments receive reimbursement for state mandates through mandate claims. As a result, when realigning administrative, programmatic, or fiscal responsibility from the state to counties, the state must provide counties with funds to cover the cost of those increased responsibilities. Rather than reimburse counties based on their actual costs, the state typically provides counties specific revenue sources—like a portion of the sales tax—to pay for their increased fiscal responsibilities under realignment. In some years, revenues may exceed counties’ costs. In other years, the revenues provided may not be sufficient to cover counties’ costs. Over time, however, the revenue provided through realignment is intended to roughly cover counties’ costs for required realigned programs.

Realignment Provides Counties Additional Revenues for Increased Responsibilities. Prior to 1978, counties used local revenue to support their share of costs for state and local health, mental health, and social services programs. After Proposition 13—passed in 1978—counties increasingly relied on state funding for many of these programs. In large part, this was because Proposition 13 dramatically reduced county revenue. In response, the state provided a “bailout,” which we describe in the box below. Consequently, when enacting realignments, the state provides new revenues to counties because of the limitation on counties’ revenue and, as described earlier, the State Constitution requires reimbursement of state‑imposed local requirements.

State “Bailout” After Proposition 13

Proposition 13 Limited Property Taxes. Proposition 13 was a landmark decision by California’s voters in June 1978 to limit property taxes. Prior to Proposition 13, each local government—cities, counties, and special districts—could set its property tax rate annually. The average rate before Proposition 13 passed was 2.67 percent. This average rate reflected the sum of individual levies of multiple local governments serving a property (including schools). After Proposition 13, a property’s overall tax rate for all local governments is limited to 1 percent. At the time of passage, Proposition 13 caused property tax revenues to drop by roughly 60 percent (almost $7 billion at the time).

State “Bailed Out” Local Governments. The state provided $4 billion to local governments ($1.5 billion to counties) to partially backfill their revenue losses from Proposition 13 in 1978. For counties, this backfill developed into an ongoing change in the state‑county fiscal partnership. Specifically, the state provided funding to counties to “buy‑out” their share of health and social services program costs that they had previously paid for using local revenue—primarily property taxes.

California Has Enacted Two Major Realignments. In California, the most significant realignments occurred in 1991 and 2011. These realignments affected multiple programs and resulted in significant revenue shifts from the state to counties. While the focus of this report is 1991 realignment, 2011 realignment affected some programs that were part of 1991 realignment. (We discuss the impacts of 2011 realignment later in this report.)

Benefits and Principles of Realignment

This section describes the benefits realignment is intended to achieve. We also identify key principles we believe any realignment needs to follow in order to achieve those benefits.

Short‑Term Benefits During Budget Shortfalls. Both 1991 and 2011 realignment were enacted in the midst of significant recessions and helped the state address its budget shortfalls. Specifically, realignments generally shifted a greater share of program costs from the state to counties and provided counties with a new dedicated revenue stream outside of the state General Fund to pay for these increased costs. In other words, the state reduced its spending commitments by shifting costs to counties without having to transfer existing General Fund to counties to pay for these increased costs. This resulted in savings that helped the state address its budget problems. While these actions clearly benefited the state at the time, counties and others argue that the realignments also reduced the cuts the realigned programs otherwise would have received due to the budget shortfall.

Long Term, Realignments Intended to Benefit Both the State and Counties. While realignment was born out of a budget crisis, it was intended to have long‑term benefits by providing counties with (1) greater local flexibility over programs and services based on local needs and (2) incentives to encourage counties to innovate to achieve better program outcomes. Better program outcomes also would benefit the state because counties would improve services and potentially reduce overall costs (for instance through more effective and efficient service delivery). Moreover, by giving counties a share of program costs, counties would have an incentive to develop strategies to control program costs within their control (like administration). This would benefit the state by reducing the overall cost of the programs.

To Achieve Benefits, Realignments Need to Follow Certain Core Principles. We believe there are certain core principles any realignment needs to follow in order to achieve the benefits described above. We have identified what we believe these core principles to be in Figure 2. For example, one key principle is that realignments aim to align state and counties’ shares of cost based on their relative control over those programs. That is, counties’ share of cost should reflect the discretion they have over how to deliver services in the program. Programs for which the state wants to set specific service delivery requirements are not good candidates for realignment. Later, we use these principles to evaluate 1991 realignment.

Figure 2

LAO Realignment Principles

|

|

Counties should be financially responsible over those program aspects for which their decisions affect cost. |

|

|

Counties’ realignment revenues should—over time—generally cover counties’ costs for their required realigned program responsibilities. |

|

|

Funding allocations should be sufficiently flexible to allow counties to use funding where it is most needed. |

|

|

The funding provided to counties should be easily understandable. Total program funding also should be easily known. |

1991 Realignment Basics

The 1991 realignment package: (1) transferred several programs and responsibilities from the state to counties, (2) changed the way state and county costs are shared for certain social services programs, (3) transferred health and mental health service responsibilities and costs to the counties, and (4) increased the sales tax and vehicle license fee (VLF) and dedicated these increased revenues to the new financial obligations of counties for realigned programs and responsibilities. This section outlines the programs and services affected by 1991 realignment and describes the basic structure and flow of funds.

Key Terms

Understanding the mechanics of realignment—here and later in the report—requires familiarity with certain terms used to describe the flow of funds and funding allocations. We define these terms below.

Revenue Allocations. The realignment legislation established the Local Revenue Fund, and within it a series of subaccounts, into which dedicated revenues are placed to fund different groups of programs and responsibilities. These include the Social Services Subaccount, the Health Subaccount, and the Mental Health Subaccount. Additional subaccounts have been added since 1991.

Base and Growth Allocations. Generally, the total amount of revenues allocated to each subaccount in one year becomes the base level of funding in the next year. Growth in revenues between two years is allocated differently across subaccounts. The growth allocation provided to social services programs—largely through the Caseload Subaccount—is based on the actual growth in the counties’ cost of those programs from year to year. If any revenues remain after providing growth to social services programs, they are divided among the remaining subaccounts. (We describe this division in more detail below.)

Base Restoration. In some years, realignment revenues are not sufficient to meet the base level of funding for all subaccounts. In 2011 realignment, this “deficit” is tracked and repaid when revenues are stronger. This is referred to as base restoration. However, 1991 realignment subaccounts are not eligible for base restoration. Consequently, when revenues decline, the base level for those subaccounts generally is lowered—only when growth funding is provided in future years will the base for those subaccounts increase.

Unmet Need. In some years, revenue growth is lower than the increase in costs for social services programs. This is referred to as unmet need. Unmet need is tracked over time and as revenues increase additional funds are provided to the Caseload Subaccount to cover those costs. Repaying prior years’ unmet need reduces the growth available for other realignment subaccounts.

Poison Pill. Statute implementing 1991 realignment included a provision that if any county made a state mandate claim that resulted in state costs of over $1 million, 1991 realignment would end. To date, no counties have made that mandate claim against 1991 realignment.

Programmatic Components of 1991 Realignment

Below, we explain how 1991 realignment affected county program responsibilities and costs for certain social services, health, and mental health programs.

1991 Realignment Increased Counties’ Share of Costs for Certain Social Services Programs. Prior to 1991, counties received state funding for many social services programs based on the Proposition 13 bailout described earlier. Counties also paid for a relatively small portion of program costs using local revenues. 1991 realignment aimed to increase county fiscal responsibility for these programs by aligning counties’ share of cost with their ability to control costs in those programs. Generally, 1991 moved in the right direction with regard to state‑county share of costs. Additionally, for some programs, 1991 realignment tried to expand counties’ ability to control services and thereby control costs. For example, the realignment legislation authorized counties to change IHSS services for a limited amount of time. This included the ability to reduce IHSS service levels or have counties change how they administered IHSS in order to be more efficient. (Later in the report, we discuss challenges with reducing IHSS service levels.)

Figure 3 lists the social services programs affected by 1991 realignment and the cost‑sharing ratio established under the original legislation. For the majority of social services programs, 1991 realignment increased counties’ share of cost largely to reflect counties relatively higher ability to control program costs. (As explained later, realignment also provided counties with revenues to support the increase in those shares of cost.) However, for CalWORKs cash assistance and county administration, realignment reduced counties’ share of cost mainly due to a belief that counties had limited ability to control these program costs.

Figure 3

Change to County Share of Nonfederal Cost for Social Services Programs Under 1991 Realignment

|

Social Services Programs |

County Share of Nonfederal Program Costs |

|

|

Prior to Realignment |

Realignmenta |

|

|

Foster Care Assistance |

5% |

60% |

|

California Children’s Services |

25 |

50 |

|

County Services Block Grant |

16 |

35 |

|

In‑Home Supportive Services |

3 |

35 |

|

County Administration (CalWORKs Eligibility, Foster Care, CalFresh) |

50 |

30 |

|

Child Welfare Services |

24 |

30 |

|

CalWORKs Employment Services |

— |

30 |

|

Adoption Assistance |

— |

25 |

|

CalWORKs Cash Assistance |

11 |

5 |

|

aReflects the county share of nonfederal program costs originally established in 1991 as a result of realignment. |

||

1991 Realignment Transferred Certain Health and Mental Health Responsibilities and Costs to Counties. In contrast to counties sharing in the financing and administration of defined social services programs, 1991 realignment transferred certain mental health service responsibilities to counties. This means, for the most part, that there was no preexisting statewide program model counties had to follow when taking on the realigned mental health service responsibilities. As a result, counties had greater flexibility to establish a local program structure and administer these service responsibilities independent of what other counties were doing, based on the mental health needs of their county residents. In addition, realignment increased counties’ costs for certain health programs. The responsibilities and costs transferred to counties included certain community‑based mental health services, public health, and indigent health (health care services for generally low‑income, uninsured adults).

1991 Realignment Funding

Counties Receive Dedicated Sales Tax and VLF Revenue for Realignment Costs. To pay for counties’ increased costs for social services programs and health and mental health service responsibilities, the state dedicated two revenue sources to 1991 realignment: (1) a new half‑cent sales tax and (2) a portion of the VLF. The half‑cent sales tax was new revenue, approved by the voters for the purposes of realignment. The VLF was increased by changing the calculation of a car’s value for the purposes of the tax. As described earlier, counties received revenue for realignment due to the Constitutional provision that the state pay for state‑imposed requirements.

Today, Counties Receive Over $6 Billion Through 1991 Realignment. 1991 realignment revenues total about $6.5 billion (over $3 billion from sales tax, $2 billion from VLF, and about $1 billion transferred from another realignment for mental health). Of the $6.5 billion, about $2 billion of 1991 realignment revenues pays for CalWORKs grants, which in effect offsets state General Fund costs for the program. Of the remaining $4 billion, about $2 billion pays for counties’ share of social services program costs—the largest being total IHSS county costs. The remaining $2 billion is roughly split between counties’ health and mental health responsibilities.

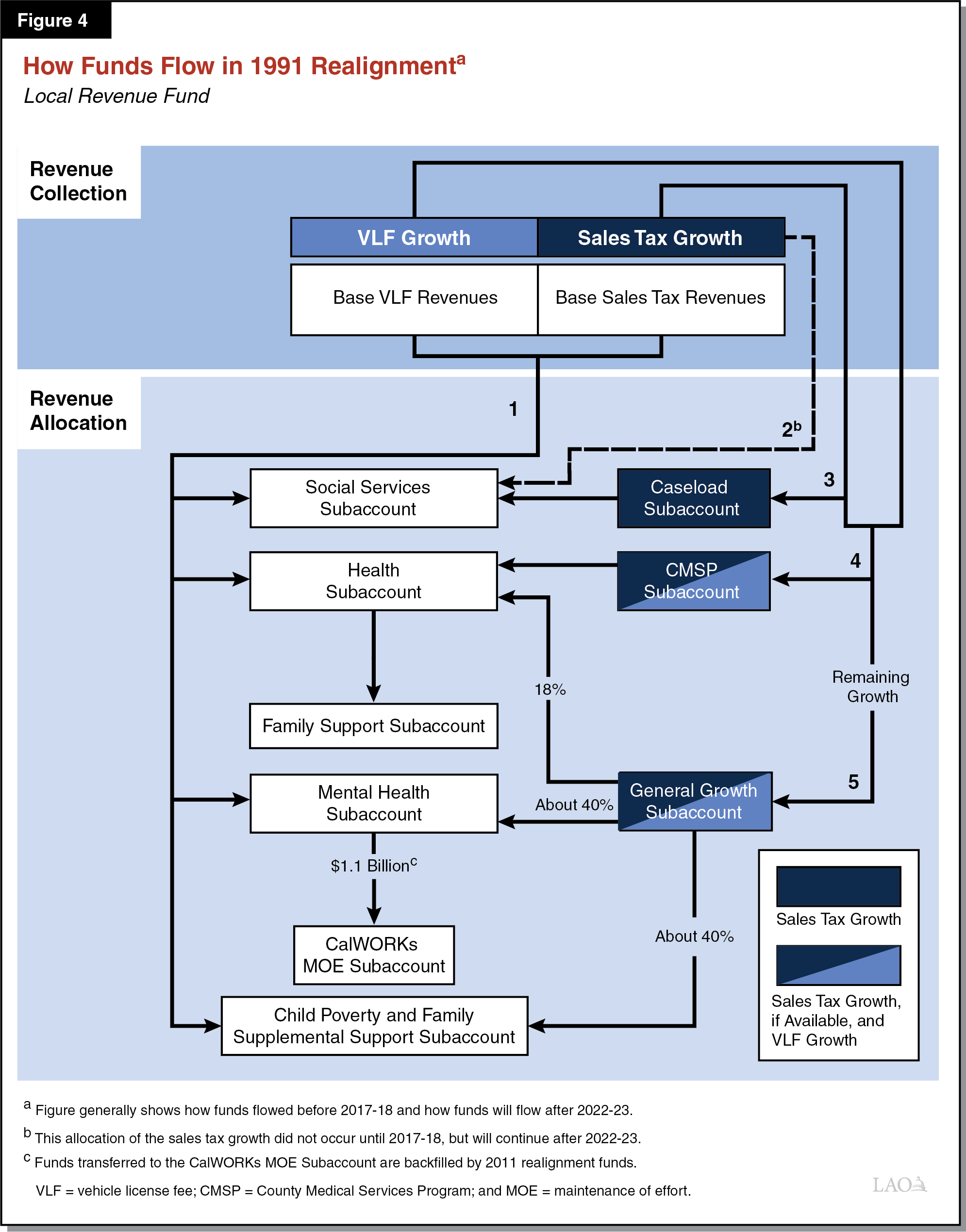

How Funds Typically Flow in 1991 Realignment. Figure 4 provides a basic description of how funds are distributed within 1991 realignment. Specifically, the figure shows how funds generally flowed before 2017‑18. From 2017‑18 through 2022‑23, the flow of funds was changed to increase the funding available for IHSS. We describe those—primarily temporary—changes later (in the “Revenue Changes” section). Absent further changes to statute, the flow of funds largely will return to its pre‑2017‑18 pattern after 2022‑23.

- Step One: Fund the Base. Sales tax and VLF revenues dedicated to 1991 realignment first fund the base level of funding provided to social services, health, and mental health programs (which, as noted earlier, typically is the prior year’s cost).

- Step Two: Sales Tax Growth to IHSS. One of the permanent changes made to 1991 realignment in the 2017‑18 Budget Act was to prioritize the use of any increases in sales tax revenue for IHSS costs. As a result, any year‑over‑year increase in sales tax revenue first is allocated to counties’ IHSS costs (through the Social Services Subaccount).

- Step Three: Remaining Sales Tax Growth to the Caseload and Social Services Subaccounts. Any remaining sales tax growth after step two then funds prior‑year increases in county costs for the other Social Services Subaccount programs (only through the Caseload Subaccount).

- Step Four: Growth to County Medical Services Program (CMSP) Subaccount. A portion of the remaining sales tax growth (if any) and a portion of the year‑to‑year growth in the VLF goes to the CMSP Subaccount, which then is allocated to the Health Subaccount. (The proportion of sales tax and VLF growth allocated to the CMSP Subaccount is based on formulas set in statute. These funds are used to fund indigent health program costs for counties that participate in CMSP. )

- Step Five: General Growth. The remaining growth from the sales tax (if any) and VLF is allocated to the General Growth Subaccount. Of the funds allocated to the General Growth Subaccount, 18 percent goes to the Health Subaccount, roughly 40 percent goes to the Mental Health Subaccount, and the remainder goes to the Child Poverty and Family Supplemental Support Subaccount (hereafter the Child Poverty Subaccount).

Funding for Social Services Programs Intended to Cover Actual Program Costs Over Time. As discussed earlier, social services programs are the first to receive realignment revenues. Over time, realignment revenues are intended to cover actual program costs associated with the increase to counties’ share of cost under realignment. The state tracks year‑to‑year increases in costs for each social services program. Additionally, the state tracks increases in costs from prior years that were not met with realignment revenues. Realignment prioritizes paying for year‑to‑year increases in total social services program costs and any unmet costs from prior years with growth revenues. Any remaining growth revenues are then used to cover county health and mental health service costs.

Funding for Health and Mental Health Responsibilities Not Directly Linked to County Costs. Unlike how social services programs are funded, there is no direct link between funding levels and actual health and mental health service costs. Specifically, the amount of realignment revenues counties receive to administer health and mental health services is based on a series of formulas, not on the amount counties spend on administering these services. These formulas are primarily based on how much counties spent on health and mental health responsibilities in the early 1990s. In effect, this means that counties may have to adjust program rules and service levels in any given year to ensure that actual health and mental health service costs mesh with available revenues.

2011 Realignment

This section describes the relationship between 1991 and 2011 realignments. It also explains the differences between 1991 and 2011 realignment.

Major Components of 2011 Realignment. In 2011, the state undertook a second major realignment. Again, this realignment, in part, was in response to a budget shortfall. The most significant parts of this realignment affected the state’s criminal justice system; however, there were changes to other programs as well. Specifically, 2011 realignment affected programmatic, administrative, and fiscal responsibility for adult offenders and parolees, court security, various public safety grants, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, child welfare programs, and adult protective services.

Counties Generally Combine 1991 and 2011 Realignment Funds to Pay for Overlapping Program Responsibilities. The fiscal responsibilities for a number of programs affected by 1991 realignment were further changed by 2011 realignment. Key shared program responsibilities between 1991 and 2011 realignment include, but are not limited to, foster care, child welfare, adoptions, and mental health. The result of these changes was that counties generally became fiscally responsible for additional program responsibilities. As a result, counties often use 1991 and 2011 realignment funds interchangeably to cover the costs in these programs.

Key Differences Between 1991 and 2011 Realignment. 2011 realignment used lessons learned from 1991 realignment to better realize the county benefits of realignment. Specifically, 2011 realignment included the following provisions:

- Constitutional Protections. To prevent new, unfunded programmatic requirements, Proposition 30 (2012) added provisions to the State Constitution exempting counties from any legislation that increases the overall costs of 2011 realignment programs if sufficient funding to enact the legislation is not provided. This provision protects counties from additional costs being added to 2011 realignment. 1991 realignment does not include this explicit protection.

- Base Restoration. 2011 realignment first distributes revenue growth to restore any prior‑year revenue shortfalls in programs’ base funding. Base restoration does not occur in 1991 realignment.

- Fund Transfers. 1991 realignment allows a certain percentage of funds to be transferred among accounts with counties’ Boards of Supervisors approval. 2011 realignment allows for transfers without this approval requirement.

- Reserves. 2011 realignment explicitly created a reserve account for saving revenues in excess of projections. 1991 realignment has no reserve account nor are counties explicitly authorized to maintain reserves.

Understanding Key Changes to 1991 Realignment

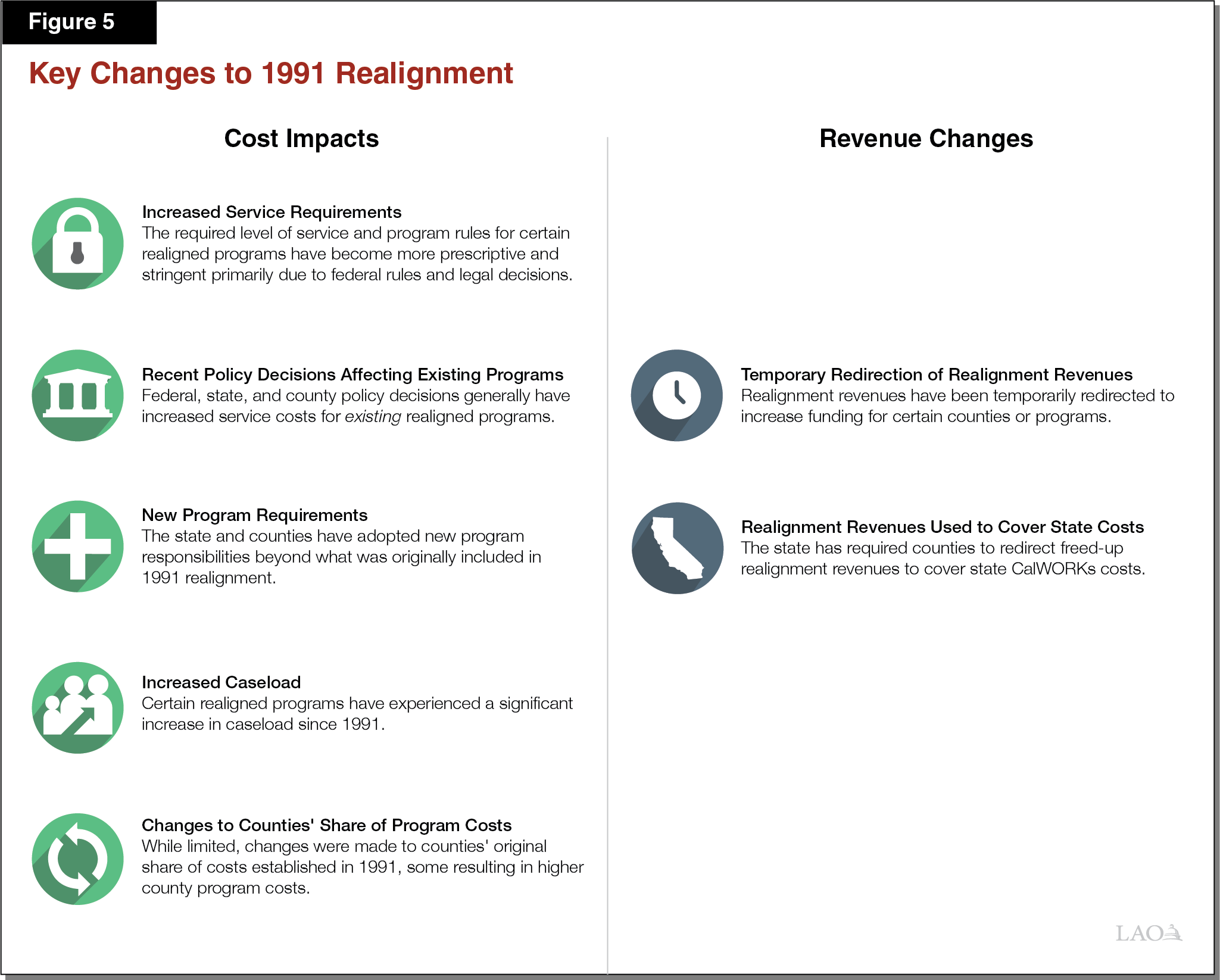

This section discusses the changes to 1991 realignment over the past 27 years. We do not include every change to 1991 realignment and the associated programs, but rather attempt to characterize the larger changes to the system over this time. We organize these changes into two main categories: cost impacts and revenue changes. Impacts to cost mainly have been driven by changes to program rules and responsibilities or increases in caseload. Similarly, many revenue changes have been due to state actions. We summarize the cost impacts and revenue changes in Figure 5. We end the section with a discussion on the impacts of these changes on counties.

Cost Impacts

Limited Flexibility to Change Service Levels. Since 1991, the required level of service and program rules for a number of realigned programs has become more prescriptive and stringent. For example, federal rules and legal decisions obligate the state and counties to provide services to anyone who meets eligibility rules for certain realigned programs—for purposes of this report we refer to these as “entitlement programs.” Below, we provide two examples of how federal rules and court decisions for entitlement programs have affected state and county control over IHSS:

- IHSS Becoming a Medi‑Cal Benefit. Since 1991, IHSS has become a Medi‑Cal benefit (California’s Medicaid health care program). By becoming a Medi‑Cal benefit, IHSS largely became an entitlement program subject to federal Medicaid rules. Integrating most IHSS services into the Medi‑Cal program allows the state to draw down more federal funds, resulting in state and county savings. Over time, however, the entitlement nature of IHSS, as a Medi‑Cal benefit, has limited the state’s and counties’ ability to change program rules, eligibility requirements, and control program costs.

- Growing Number of Legal Decisions. Some realigned programs must adhere to certain legal decisions, limiting the state’s and counties’ ability to change service levels or program rules. For example, during the recent recession when the state proposed reducing IHSS services, there was litigation asserting that these reductions violated federal rules. We discuss this decision in more detail in the box below.

Settlement Agreement Related to Proposed IHSS Reductions

During the recession, the state proposed a number of changes to the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program intended to create budget savings, including the institution of stricter eligibility rules and reducing service hours by 20 percent. Multiple class action suits were brought against the state to prevent these changes from taking effect (Oster v. Lightbourne, et al. I and II and Dominguez v. Brown, et al.). Ultimately, the federal district courts issued temporary injunctions preventing the state from making these changes. While the state did appeal these injunctions, a legal settlement was reached in 2013 resulting in a reduction to IHSS service hours (less than what the state initially proposed). Currently, the state has temporarily restored IHSS service hours that were eliminated. Based on current law, the restoration is effective through 2018‑19.

Federal, State, and County Policy Decisions Generally Have Made Existing Realigned Programs More Costly. In recent years, federal, state, and county governments have made policy decisions that have increased costs for major realigned programs. While these decisions did not increase service requirements in realigned programs, they did increase the costs to provide existing services. Examples of such policy changes include:

- IHSS Provider Wage Increases. IHSS provider wages increase in two main ways—(1) increases that are in response to state minimum wage increases and (2) increases that are collectively bargained or established at the local level. In 1999, the state required that counties establish an employer of record for IHSS providers for purposes of collective bargaining. Due to this action, all counties today have the ability to negotiate and establish IHSS provider wages above the state minimum wage. Under the current IHSS financing structure, counties do not have a share of costs associated with increases to the state minimum wage, but do have a share of costs associated with local wage increases above the state minimum wage.

- Federal Labor Rules. In February of 2016, the state implemented the new federal labor regulations for home care workers. Under the federal regulations, the state is required to compensate IHSS providers for overtime (hours worked in excess of 40 hours per week), time spent waiting during medical appointments, and time spent traveling between the homes of IHSS recipients. Similar to increases to the state minimum wage, these federal labor rules—as interpreted in California—increase service costs for IHSS.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Under the ACA, states had the option to expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs. California opted to expand Medicaid eligibility, which took effect in January 2014 (see the box below for details). The effect of the ACA on realigned health and behavioral health (mental health and substance use treatment) program costs is mixed. For example, counties are responsible for providing health care and behavioral health services to the “indigent” population—generally low‑income, uninsured adults. Much of the indigent population became eligible for Medi‑Cal coverage due to the ACA optional expansion. As a result, counties’ costs and responsibilities for indigent health care services significantly decreased. (In the next section, we discuss how the state utilized these health care‑related realignment savings to fund General Fund costs for CalWORKs.) Some counties have noted, however, that the increased enrollment in Medi‑Cal as a result of the ACA has increased demand for county behavioral health services.

Effect of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) On Medi‑Cal Eligibility

Under the ACA, states had the option to expand eligibility for their Medicaid program. Before the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was generally restricted to families with children, seniors and persons with disabilities with incomes below 108 percent of federal poverty level (FPL). Therefore, nondisabled, childless adults under age 65 were ineligible for Medicaid regardless of income. Under the ACA, states had the option—which was exercised by California—to expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs to all qualified residents under age 65 with household incomes at or below 138 percent of the FPL beginning January 2014. As of today, over 3 million Californians have obtained health insurance through the Medi‑Cal optional expansion.

State and Counties Adopted New Program Responsibilities, Generally Increased Overall Program Costs. Based upon our conversations with counties, realigned program costs also have increased as a result of newly adopted program responsibilities by the state and counties beyond what were originally included in 1991 realignment. Examples of these new program responsibilities include:

- Adult Specialty Mental Health Managed Care Program. By 1998, the state shifted programmatic and fiscal responsibilities for much of adult specialty mental health services to counties, including certain psychiatric inpatient hospital services and outpatient specialty mental health services. At the time, the state provided counties with additional funding for these newly realigned mental health program responsibilities (specifically, the amount the state was spending on these services). Over time, any cost increases were largely expected to be paid for with growth in 1991 realignment revenues. Some counties have stated that 1991 realignment funds alone are not enough to pay for the increased demand and overall costs for these mental health program requirements over time.

- Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System (ODS) Pilot Program. In 2016, counties were given the option to participate in a pilot program to provide substance use disorder services for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries beyond the required services under Medicaid. Currently, 40 counties opted into the pilot program, of which about half have OSD services up and running. Participating counties stated that they took on these additional program responsibilities as a way to increase behavioral health service levels and draw down additional state and federal funding. In addition, some counties believed that providing additional behavioral health programs could potentially reduce other health care costs, such as costs associated with emergency room and hospital inpatient visits. Our understanding is that counties took on these new program requirements with the expectation that they could use multiple funding sources, including growth in 1991 realignment revenues, to fund ODS program costs.

Overall, due to the provisions of the poison pill (see 1991 Realignment Basics above), counties generally are reluctant to submit mandate claims against new state‑imposed program responsibilities that occurred after 1991. Additionally, to some extent, counties have been able to use a mix of revenues—including 1991 and 2011 realignment funds, Mental Health Services Act funds, and federal grants—to cover new mental health program costs added to realignment.

Caseload Expanded Significantly in IHSS and Mental Health. Since 1991, key realigned programs have experienced a significant increase in caseload, resulting in higher program costs. For example, caseload in the IHSS program has more than tripled in the past 27 years, from about 160,000 in 1990‑91 to an estimated 545,000 in 2018‑19. (In contrast, the population of California has grown by roughly one‑third over that same time period.) Additionally, counties have expressed that the utilization of local mental health services has grown significantly since 1991. (We were not able to quantify caseload growth for specific 1991 realigned mental health services because such service‑level caseload data is not available.) The reasons for the significant caseload growth in IHSS and mental health are not completely understood, but likely are due to demographic and population changes in counties. In the case of IHSS, some counties have expressed that caseload growth is partially due to a significant rise in the local senior (aged 65 and older) population and a preference to age at home rather than in an institution.

State‑County Cost Sharing Arrangement Recently Changed for IHSS. As described earlier, costs for realigned programs have increased primarily due to new federal and state policies, program requirements, service cost growth, and caseload growth—things largely outside the control of counties. Despite increasing program costs and limited local flexibility, the state‑county cost‑sharing structure for realigned programs generally have remained the same. The most recent, and significant, exception was the implementation of a new IHSS maintenance of effort (MOE).

Between 2012‑13 and 2016‑17, the share of cost for IHSS established under 1991 realignment was replaced with an IHSS MOE—referred to as the 2011 IHSS MOE. Over the five years in which the 2011 IHSS MOE was in effect, growth in the county IHSS MOE was less than the growth in total IHSS costs, resulting in counties paying for a smaller share of the nonfederal IHSS costs and the state General Fund paying for a greater share of nonfederal IHSS costs relative to the original cost‑sharing ratios established under 1991 realignment. Additionally, the relatively slower growth in county IHSS costs allowed a greater share of realignment funds to pay for health, mental health, and CalWORKs costs.

In 2017‑18, a new county IHSS MOE was established—referred to as the 2017 IHSS MOE. The 2017 IHSS MOE changed county costs to roughly reflect the original county cost‑sharing ratios established under 1991 realignment (35 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS service costs and 30 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS administrative costs). As a result, the 2017 IHSS MOE significantly increased IHSS county costs relative to what county costs would have been under the 2011 IHSS MOE. Specifically, total IHSS county costs are expected to have increased by about $640 million in 2017‑18 relative to 2016‑17. Moving forward, it is expected that the majority of total realignment funds for social services programs—roughly 80 percent in 2017‑18—will be needed to cover IHSS county costs for the foreseeable future. (If the historical cost‑sharing ratios had remained in place between 2012‑13 and 2016‑17, the amount of realignment revenues used to cover IHSS county costs would have increased incrementally. As a result, without the 2011 IHSS MOE, the realignment funding issues highlighted in this report would have surfaced earlier.) We discuss in detail the technical differences between the 2011 and 2017 IHSS MOE in the box below.

2011 and 2017 County IHSS MOE

Below, we describe the 2011 and 2017 county In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) maintenance of effort (MOE) and discuss the differences between the two arrangements.

2011 IHSS MOE. As of 2012‑13, all counties were required to maintain their 2011‑12 expenditure levels for IHSS, to which an annual growth factor of 3.5 percent was applied beginning in 2014‑15. Added to the MOE were any county costs associated with local IHSS wage increases. The state General Fund assumed the remaining nonfederal IHSS costs. Over the five years in which the 2011 IHSS MOE was in effect, the annual IHSS MOE growth factor was less than the year‑to‑year growth in total IHSS nonfederal costs. As a result, a greater share of nonfederal IHSS costs was shifted from counties to the state. Specifically, under the 2011 IHSS MOE, the state share of IHSS nonfederal costs increased from 65 percent in 2011‑12 ($1.7 billion) to 76 percent in 2016‑17 ($3.5 billion). Additionally, the relatively slower growth in county IHSS costs allowed the Health, Mental Health, and Child Poverty Subaccounts to receive a greater share of realignment funds.

2017 IHSS MOE. Budget‑related legislation adopted in 2017‑18 eliminated and replaced the 2011 IHSS MOE with a new county MOE financing structure. Under the new 2017 IHSS MOE, the counties’ share of IHSS costs was reset to roughly reflect the counties’ share of estimated 2017‑18 IHSS costs based on historical county cost‑sharing ratios (35 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS service costs and 30 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS administrative costs). Additionally, the 2017 IHSS MOE will increase annually by (1) the counties’ share of costs from locally negotiated wage increases and (2) an annual adjustment factor.

As shown in the figure, the annual adjustment factor depends on the rate of growth in realignment revenues. If realignment revenues are less than prior‑year levels, the adjustment factor for the 2017 IHSS MOE will be zero. If the realignment revenues grow by less than 2 percent, the adjustment factor will either be 2.5 percent in 2018‑19 or 3.5 percent in 2019‑20 and onwards. If the realignment revenues grow by more than 2 percent, the adjustment factor will be either 5 percent in 2018‑19 or 7 percent in 2019‑20 and onwards. The administration forecasts the adjustment factor will be 5 percent in 2018‑19 and 7 percent in the coming years. Relative to the 2011 IHSS MOE, a higher adjustment rate means that fewer IHSS costs will be shifted to the state from counties. Additionally, to the extent that the MOE adjustment rate is greater than (or less than) actual growth in total IHSS costs, counties will be responsible for a higher (or lower) share of IHSS costs relative to the original county share of cost established under 1991 realignment.

2017 IHSS Maintenance of Effort (MOE) Annual Adjustment Factora

|

If Realignment Revenues Grow By . . . |

. . . Then the IHSS MOE Will Increase By . . . |

|

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 and Onwards |

|

|

No growth |

0 |

0 |

|

Less than 2 percent |

2.5% |

3.5% |

|

More than 2 percent |

5.0 |

7.0 |

|

aIn addition to the annual adjustment factor, the 2017 IHSS MOE will increase by counties’ share of costs from local IHSS wage increases. |

||

Revenue Changes

In this section, we explain key changes to realignment revenues since 1991. In general, revenue changes are due to broader trends in the tax base or state policies.

Temporary Redirection of 1991 Realignment Revenues. The state has temporarily redirected realignment revenues mainly either to improve the distribution of funds to certain counties or increase the level of funding for certain programs. Below, we describe two ways in which realignment revenues have been temporarily redirected.

- Temporarily Redirected Growth Revenue to “Under‑Equity” Counties. Prior to the enactment of 1991 realignment, counties’ per‑person funding for health and mental health programs varied. When 1991 realignment was enacted, the distribution of realignment health and mental health funding was based on these local allocations. For some counties, the funding provided through 1991 realignment did not necessarily reflect the resources needed to fully address their local program needs. (These counties are commonly referred to as under‑equity counties.) The state tried to address this issue beginning in 1994‑95 by creating multiple health and mental health “equity subaccounts” that would provide under‑equity counties with additional realignment growth revenues based on each county’s overall population and the population of local low‑income residents. These allocations increased recipient counties’ overall health and mental health funding. The final equity payments were provided in 2000‑01. While the equity shortfall for these counties was reduced, there are still differences in funding among counties that do not necessarily reflect differences in program funding needs.

- Temporarily Redirecting Growth Revenues to Pay for IHSS County Costs. The 2017‑18 budget package changed the flow of funds in response to increased IHSS county costs. Specifically, in addition to receiving all sales tax growth, IHSS will temporarily receive almost all of VLF growth. As a result, the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts will receive no VLF growth funds for three years—from 2017‑18 to 2019‑20. The VLF growth funding for these subaccounts will be partially restored in 2020‑21 and fully restored in 2022‑23 and onwards. (We note that the 2017‑18 budget package also made a permanent change to when counties receive sales tax growth revenue to improve counties ability to pay for IHSS costs.)

1991 Realignment Savings Used to Offset State Costs. In recent years there have been state and federal actions that reduced realignment‑related costs. The state has required counties to redirect freed‑up realignment revenues to newly created subaccounts in order to achieve state savings (by offsetting state CalWORKs costs) or support CalWORKs grant increases. Below, we describe three ways in which the state has redirected 1991 realignment funds:

- Redirection of Mental Health Funds to CalWORKs MOE Subaccount. In 2011, mental health funds from 1991 realignment were replaced with 2011 realignment funds. In effect, this freed‑up $1.1 billion within 1991 realignment‑related mental health funding obligations. The freed‑up 1991 mental health funds are shifted to the CalWORKs MOE Subaccount (created in 2011) within 1991 realignment, which offsets General Fund costs for CalWORKs grants. This change does not affect overall funding for CalWORKs or 1991 realignment programs.

- Redirection of Indigent Health Funding to New Subaccount. Prior to the ACA, counties largely were responsible for indigent health care. Counties paid for these costs with 1991 health realignment funds. Under the ACA, Medi‑Cal covers many of the individuals for whom the counties previously had been responsible. As a result, counties’ indigent health costs have declined. In recognition of these savings, the state requires counties to shift a portion of their Health Subaccount funding to a newly created Family Support Subaccount. (We note that the remaining portion of health realignment funds is used to cover county public health program costs and any remaining indigent health care costs.) The funds in this subaccount are used to offset General Fund costs for CalWORKs grants and county administration. In 2018‑19, counties are projected to transfer, in total, $773 million of health realignment funds to the Family Support Subaccount.

- Redirection of General Growth Funds to New Subaccount. Similar to indigent health costs, the 2011 IHSS MOE reduced county social services costs relative to historical cost levels. As a result, a greater amount of revenue growth was made available for other 1991 realignment programs. In recognition of these savings, the 2013‑14 budget package required counties to shift a portion of that growth (if available) to the newly created Child Poverty Subaccount. The funds in the Child Poverty Subaccount are used to fund certain CalWORKs grant increases. Absent these funds, existing CalWORKs grant costs originally paid for by the Child Poverty Subaccount would be paid for by the state General Fund. In 2018‑19, counties are projected to transfer, in total, roughly $350 million of general growth funds to the Child Poverty Subaccount.

Absorbing Changes Difficult for Counties

Counties’ Ability to Pay for Increased Realigned Program Costs With Local Funds Is Limited. As outlined in this section, program costs for realignment have increased for various reasons and the state’s and counties’ ability to control costs is limited. In the case of realigned social services programs, although realignment provides counties with revenues to pay for increased program and service costs over time, counties indicate that realignment revenues are not always sufficient to cover the total program and service costs in each year. In the years that revenues are not enough, counties must use other local revenues to meet their realigned program fiscal responsibilities. Counties’ ability to raise additional local funds to cover unmet social services program costs, however, is limited. In particular, counties cannot raise the rate on their largest source of revenue—property tax—due to the provisions of Proposition 13. Subsequent statewide ballot measures also have constrained counties’ ability to raise revenue through other types of taxes, fees, and assessments. Consequently, over time, counties’ ability to raise revenue using broad‑based taxes to support realigned social services programs has become quite limited.

Unfortunately, there is no statewide data on what amount of local revenue counties spend on 1991 realignment programs. As noted earlier, the state only tracks and repays unmet need for social services programs costs. The state does not provide base restoration if revenues are not sufficient to cover the prior year’s costs for all 1991 realigned programs. As a result, counties must use local revenues to cover those base costs. The amount of local revenue used to cover these shortfalls in the base is not tracked. Similarly, the state does not track what amount, if any, counties spend on health and mental health services above the funding provided through 1991 realignment and other state sources.

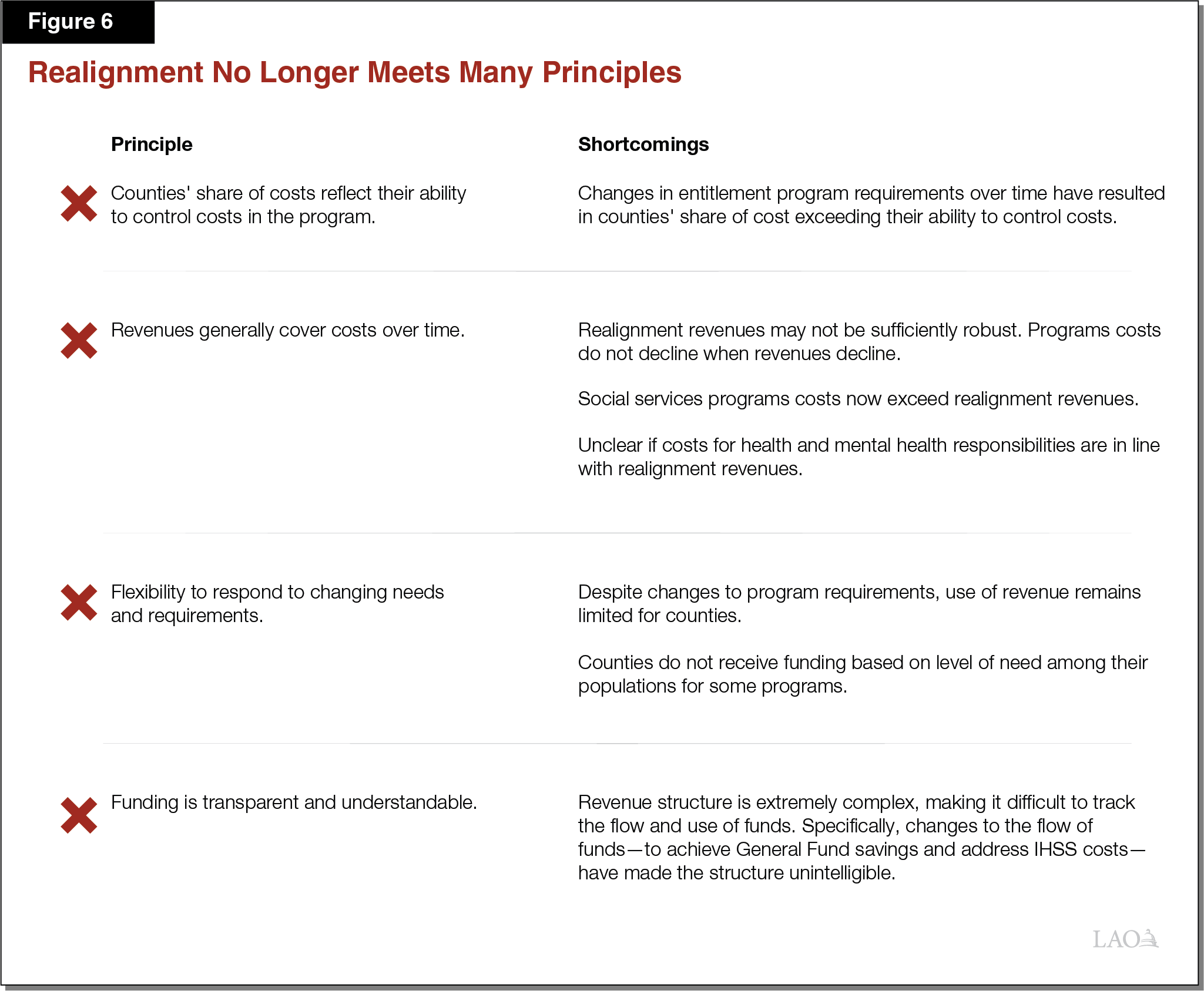

1991 Realignment No Longer Meets Many LAO Principles

The changes made by 1991 realignment aimed to create better incentives for counties to control program costs and largely allow counties to tailor health and mental health programs based on local needs. Additionally, realignment intended to increase counties’ ability to change program rules and service levels for social services programs. Generally, 1991 realignment made progress towards creating better incentives for counties, but did not ultimately give them much control over social services programs. Moreover, due to the various changes to 1991 realignment programs without corresponding changes to the realignment funding structure, 1991 realignment today no longer meets many of the core principles of a state‑county fiscal partnership we identified in Figure 2. Figure 6 summarizes why 1991 realignment no longer meets these principles, which we discuss in this section.

Counties’ Share of Program Cost Should Reflect Control

Today, Counties’ Share of Program Cost Does Not Reflect Their Ability to Control Costs. While the original cost‑sharing ratios for realigned programs moved in the right direction relative to prior fiscal responsibilities, many no longer reflect counties’ long‑term ability to control costs in the programs. Today, counties’ share of cost for many realigned programs exceeds their ability to control costs in those programs. As described earlier, the erosion in county control is largely due to state and federal policy changes in combination with increased caseload and court decisions requiring certain levels of service. For example, past attempts to reduce IHSS service levels in an attempt to reduce program costs have largely failed due to legal protections. The state largely has not made commensurate adjustments to the cost‑sharing ratios within 1991 realignment in response to these changes in county control.

Revenues Generally Should Cover Costs Over Time

Realignment Revenues May Not Be Sufficiently Robust. Since 1991, realignment revenues have grown 3.7 percent per year on average. In comparison, assuming constant tax rates, the personal income tax—the state’s largest source of revenue—has grown 5.5 percent per year on average. The property tax—local government’s single largest source of tax revenue—has grown almost 5 percent per year on average. While realignment revenue growth was intended to generally keep up with the growth in costs, no assessment of whether revenue growth is sufficient to maintain services has been made. Moreover, realignment revenues tend to decrease during recessions when caseload and demand for programs can increase (or at least remain constant). For example, between 2007‑08 and 2008‑09 the CalWORKs caseload increased by 8 percent, whereas realignment revenue declined by roughly 10 percent. Moreover, 1991 realignment does not explicitly allow counties to maintain reserves, which could help mitigate the impacts of year‑to‑year revenue declines.

Social Services Programs Costs Now Exceed Realignment Revenues. As noted earlier, counties’ social services programs’ costs are meant to be covered—over time—by realignment revenues. However, primarily due to IHSS county costs, realignment revenues alone will no longer be enough to pay for total county social service program costs for the foreseeable future. Specifically, total IHSS county costs are estimated to exceed dedicated realignment revenue by about $540 million in 2017‑18. While the additional state General Fund assistance ($400 million in 2017‑18 and declining to $150 million by 2020‑21) and temporary redirection of other realignment funds are expected to cover the majority of the shortfall in 2017‑18, about $25 million of costs will go unmet in 2017‑18. This shortfall is expected to grow in future years. As a result, counties will most likely need to use an increasing amount of other local revenue to fully cover IHSS costs.

Unclear if Costs for Health and Mental Health Responsibilities Are in Line With Realignment Revenues. Counties have expressed that realignment revenues are insufficient to cover health and mental health responsibilities, however, there is not sufficient statewide data to make this determination. In part, this is due to the fact that the amount of realignment revenues allocated to counties for health and mental health responsibilities is determined by a formula, not actual costs. While the state collects data on how much funding each county receives from realignment, the state does not collect data on the total cost incurred by counties to provide realigned health and mental health services. Consequently, while the amount of revenue each county receives for health and mental health responsibilities is known, whether costs for all health and mental health responsibilities align with the allocated realignment revenues is unknown.

Should Have Flexibility to Respond to Changing Needs and Requirements

Despite Changes to Program Requirements, Use of Revenue Remains Constrained for Counties. The realignment structure allows for counties to shift up to 10 percent of revenues between the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts on a one‑time basis annually. Most counties must receive permission from their Board of Supervisors to make this shift, which may make using this flexibility politically difficult for counties. Aside from this flexibility, however, the structure of realignment does not allow for counties to move funds across subaccounts and has not been adjusted in response to changing state and federal program requirements.

Growth Distribution Among Counties Based on the 1990s. As previously mentioned, counties largely receive revenue growth funds for health and mental health responsibilities in the same proportions as they did in 1991. Specifically, the distribution formula is largely based on how much counties spent on those programs in the early 1990s. Consequently, those counties that did not spend much on health or mental health services in the early 1990s receive a relatively low proportion of the revenue growth today. For many counties, the populations served by these programs have changed significantly since that time—both in terms of the number of eligible individuals as well as in terms of their service needs.

Funding Should Be Transparent and Understandable

Revenue Structure Extremely Complex. Understanding the flow of funds within 1991 realignment is very challenging. This is partially due to the permanent redirection of realignment revenues for uses outside of the original intent of realignment—namely to offset state CalWORKs costs—and the temporary provision of additional revenues to cover IHSS county costs. As a result of these changes, the tracking of realignment revenues and program expenditures has increased in complexity and the flow of funds is more labyrinthine. Moreover, while the state tracks how much realignment revenue counties receive, there is no statewide data to determine how much total federal, state, realignment, and local revenue is provided for each realigned program and responsibility. As a result, counties’ use of other revenue streams to supplement 1991 realignment revenues and fund realigned program responsibilities is largely unknown.

No Automatic State Oversight Mechanism to Assess Overall Fiscal Health of 1991 Realignment. There is no annual appropriations process for 1991 realignment because counties receive dedicated revenues. As a result, there is no automatic process to determine whether funding counties receive for these programs and responsibilities is sufficient. Moreover, as noted earlier, the state does not collect sufficient information to determine whether realignment revenue is sufficient to meet all requirements.

1991 Realignment Likely Not Achieving Intended Benefits

Overall, due to increased program responsibilities, 1991 realignment no longer meets many of the core principles we identified and likely is not achieving the desired benefits of realignment. As noted earlier, 1991 realignment was intended to have certain benefits for both the state and counties. This section discusses the extent to which 1991 realignment is achieving those benefits today.

Decreased Local Flexibility. Throughout this report, we have cataloged the ways in which county flexibility over programs has diminished over the last three decades. While counties maintain control over some elements of program delivery, required services consume a significant portion of what counties provide through 1991 realignment. In many ways, counties have less flexibility to respond to local needs relative to when 1991 realignment was implemented.

Unclear Effects on Innovation and Improved Program Outcomes. While program outcomes are outside of the scope of this report, the lack of program flexibility may be constraining counties’ ability to innovate. Moreover, there is very little—if any—state oversight regarding counties’ delivery of 1991 realignment services. Consequently, the state’s ability to assess realignment’s impact on outcomes is limited.

Unknown Cost Savings. As noted earlier, there is no comprehensive data on total expenditures for realigned programs. As a result, we cannot assess the extent to which the state is achieving any savings under realignment. In addition, given the increasingly prescriptive programmatic requirements which limit counties’ ability to try different strategies, counties’ ability to achieve savings through innovation likely also is constrained.

Options for Improving 1991 Realignment

Below, we present options for (1) better aligning the fiscal structure of 1991 realignment with the LAO principles laid out earlier and (2) achieving intended state and county benefits. We organize these options into three sections. The first section presents options for changing cost‑sharing ratios to better align counties’ share of costs with their ability to control those costs. The second section presents options to better align revenues and costs. The third section outlines other improvements that could be made to 1991 realignment to better align it with our principles. Generally, all of these options could be pursued in tandem or individually to improve 1991 realignment.

Change Cost‑Sharing Ratios

This section outlines options for better aligning counties’ share of cost with their ability to control costs in realigned programs. Specifically, these options would reduce counties’ share of IHSS costs and propose other programs—over which counties have greater control—to either realign or increase the counties’ existing share of cost. We summarize these options and the principles addressed in Figure 7 and discuss one specific possibility in greater detail below.

Figure 7

Change Cost‑Sharing Ratios

|

Options |

Realignment Principles Addressed |

|

Reduce county share for IHSS and increase county share for another program (such as forensic court commitments). |

|

|

Reduce County Share for IHSS . . . Although counties are expected to be able to cover the majority of their share of IHSS costs in the short‑term (in large part due to the additional General Fund assistance and temporary redirection of other realignment funds), they have expressed concern that realignment revenues will not be enough to cover increased IHSS costs in the coming years. As discussed earlier, following 1991 realignment, a number of state and federal policies and legal decisions have made it difficult for the state and counties to change service levels or program rules for IHSS. Given that the 2017 IHSS MOE is based on the original cost‑sharing ratio established in 1991 (35 percent), counties current share of IHSS costs arguably does not reflect their actual ability to control program costs. One solution would be to reduce the counties’ share of IHSS cost to better reflect their level of control over the program. (In particular, counties can affect program costs through their administration of the program and negotiations over wages and benefits.)

Reducing counties’ IHSS costs would reduce the amount of realignment funds required to cover those costs. For instance, ending the 2017 IHSS MOE and giving counties responsibility for between 20 percent and 25 percent of IHSS costs in 2019‑20 would reduce their costs by roughly $800 million to $500 million. Absent other actions, this change would mean there would be sufficient funding within realignment to cover counties’ IHSS costs plus free up roughly $500 million to $200 million in realignment funding that could flow to health and mental health programs. Reducing counties’ IHSS costs, however, would increase IHSS General Fund costs by roughly $800 million to $500 million (including the $200 million General Fund support the state plans to provide counties under the 2017 IHSS MOE). To reduce the impact to the General Fund, the Legislature could offset some or most of the increase in IHSS General Fund costs by increasing counties’ fiscal responsibilities for other programs over which counties have relatively greater control over costs. In effect, the state would “swap” a portion of counties’ fiscal responsibility for IHSS for a share of another program currently supported by the state General Fund.

. . . Increase County Share for Other Programs. There are a few realignment swap options that, if carefully considered and designed, could better fit within the realignment principles outlined earlier. We believe the best option to explore for such a swap would be forensic court commitments. Currently, counties are responsible for almost all mental health treatment for low‑income Californians with severe mental health needs. One exception, however, is treatment for individuals found incompetent to stand trail or not guilty by reason of insanity in felony cases (referred to as felony forensic court commitments). The state treats almost all felony forensic court commitments in state hospitals; however, many individuals wait in county jails for many months given the limited number state hospital beds. Counties are only responsible for providing treatment to individuals in misdemeanor forensic court commitments.

Given counties’ current mental health responsibilities, the Legislature could consider making counties responsible for treating all forensic court commitments and making counties responsible for a portion of those costs through 1991 realignment. Counties could continue to send individuals to state hospitals, treat them in county jails, or use other community‑based treatment options as appropriate. Realigning these responsibilities to the counties better fits our realignment principles in that counties would have better ability to control costs based on treatment decisions. Additionally, given that the mental health needs of felony forensic court commitments generally are similar to those of misdemeanor forensic court commitments, counties are positioned to treat both populations. In recognition of this control and ability to provide services, the state has implemented various programs—most recently in the 2018‑19 Budget Act—to give counties greater responsibility for felony forensic court commitments.

If the Legislature shifted this treatment responsibility to counties, we recommend giving counties substantial portion of the fiscal responsibility because counties’ choices about treatment would significantly affect overall costs. For instance, if counties were responsible for roughly 50 percent of the cost for serving individuals in felony forensic court commitments, total county costs would be roughly $500 million annually (based on the current population). This amount reflects half of what the state plans to spend in 2018‑19 on state hospital treatment for felony forensic court commitments plus an estimate of the cost to treat those waiting in county jail. Funding for this increase in mental health responsibilities could be provided to counties through 1991 realignment using revenue freed up from reducing counties’ IHSS costs. If the Legislature shifted a larger share of cost to counties, additional funding would need to be provided to counties.

Better Align Revenues and Costs

This section outlines two ways to change realignment funding allocations to address our realignment principle that over time revenues generally should cover costs, as summarized in Figure 8. The first way addresses the growth allocations, but does not fully address our principle that revenues generally cover costs over time. However, these changes would improve the distribution of funds moving forward. The second way, addresses overall program funding and would make more progress towards meeting this principle.

Figure 8

Better Align Revenues and Costs

|

Options |

Realignment Principle Addressed |

|

|

|

Update Growth Allocations

Update Counties’ Growth Allocations for Health and Mental Health Responsibilities. While the amount of growth funding counties receive for social services programs is meant to cover actual increases in costs, the amount of growth funding counties receive for health and mental health services is not tied to actual costs or local needs. Under this option, the amount of funding each county receives for health and mental health services would be updated to reflect counties’ current populations (rather than being based on what counties provided in the 1990s). We describe below two methods—one using existing funding and one providing additional funding—to make this update.

Use Existing Resources. This change could be made without increasing funding for these services; however, as a result, some counties would receive more funding while other counties would receive less funding (compared to today). To make this change, the formulas that govern the distribution of growth funding to each county within the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts would need to be updated. There are many different approaches for updating these formulas including distributing funding proportionally based on counties’ share of low‑income individuals. Due to the temporary redirection of VLF funding, this update would not have any practical effect—because there is no growth funding to these subaccounts—for a few years. Moreover, for the foreseeable future, all sales tax growth funds will be used to cover counties’ IHSS costs. Consequently, the overall growth funding to these accounts will be limited. As a result, there would be little change to the distribution of health and mental health funding among counties for many years.

Provide Additional Resources. Alternatively, the amount of growth funding allocated to the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts could be increased by reversing recent changes to realignment that offset General Fund costs. Specifically, the growth funding provided to the Family Support and Child Poverty Subaccounts would be reduced and shifted to the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts. (Because the Family Support and Child Poverty Subaccounts offset General Fund costs related to CalWORKs, reducing funding to these accounts would increase General Fund costs in future years.) One advantage of this alternative is that no county would receive less growth funding under an updated formula (compared to today). In addition, increasing funding for health and mental health services could help counties cover the increasing costs from the additional service responsibilities discussed earlier.

Increasing the amount of funding available would require not only updating the distribution formulas—described above—but also determining how much additional funding might be required. This would require the Legislature to direct the administration to work with counties to determine where service needs are growing more rapidly and distribute additional growth funding based on this measure.

Increase Funding to Address Existing Shortfalls

Increase Funding to Address Shortfalls for Social Services Programs. As noted earlier, the shortfall—excluding General Fund support and temporary redirection of VLF revenues—for social services programs is at least $540 million. Moreover, this shortfall will grow in future years. Rather than providing General Fund support through the budget process, funding within realignment could be redirected to cover this shortfall. Specifically, funding in the Family Support and Child Poverty Subaccounts could be reduced and redirected to the Social Services Subaccount. Because these subaccounts offset General Fund costs associated with CalWORKs, any reduction in existing funding to these subaccounts would come with simultaneous dollar‑for‑dollar General Fund costs. Moreover, future CalWORKs grant increases that would be funded with growth in the Child Poverty Subaccount would no longer occur absent legislative action. (These two subaccounts are estimated to receive a combined total of roughly $1 billion in 2018‑19.) Redirecting funds in this way would better match realignment revenues with realignment costs and simplify the flow of funds within realignment.

Assess Potential Shortfall for Health and Mental Health Responsibilities. The Legislature also could consider redirecting a portion of the funding in the Family Support and Child Poverty Subaccounts to the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts. As noted earlier, counties have flexibility to determine how to provide health and mental health services using funds from those subaccounts. As a result, determining whether there is a funding shortfall in those subaccounts—and therefore how much additional funding to provide—is very difficult. Consequently, before shifting funding to these accounts, the Legislature would need to direct the administration to work with counties to make this determination. At minimum, this would require determining what specific services should be paid by the Health and Mental Health Subaccounts and collecting data from counties on the cost of those services.

Other Improvements to Align to Principles

This section outlines a variety of other changes that could be made to realignment to better align it with our principles. Figure 9 summarizes these changes and the principles addressed.

Figure 9

Other Improvements to Align Principles

|

Options |

Realignment Principles Addressed |

|

Apply lessons from 2011 realignment. |

|

|

|

|

Track realignment revenues and costs. |

|

|

Encourage counties to maintain reserves. |

|

|

Consider long‑term impact of policy decisions on ability to control program costs. |

|

Apply Lessons From 2011 Realignment. 2011 realignment incorporated some of the lessons learned from 1991 realignment. Those lessons were not, however, extended to 1991 realignment simultaneously. To improve 1991 realignment, the Legislature could apply all or some of these lessons back to 1991 realignment. Specially, the Legislature could:

- Provide Constitutional Mandate Protection. Counties only would be required to carry out new programmatic requirements within 1991 realignment if additional funding were provided to cover the costs of those requirements. (This change would require voter approval.) By providing state funding for new program requirements, counties’ share of cost would reflect their preexisting program responsibilities.

- Provide Base Restoration to All Programs. All subaccounts would be restored after any reductions due to lower revenues. Providing more consistent funding to these programs would give counties greater flexibility to respond to state and local needs and requirements.

- Allow More Fund Transfers. Remove the requirement to receive Board of Supervisors approval for fund transfers between subaccounts. Simplifying the process in which funds can be transferred may give county health and human service agencies more flexibility to respond to state and local needs.