The 2019-20 Budget:

California's Fiscal Outlook

See a list of this year's fiscal outlook material, including a fuller discussion of Proposition 98, on our fiscal outlook budget page.

November 14, 2018

The 2019-20 Budget

California's Fiscal Outlook

- Chapter 1

- Introduction

- Economy

- Revenues

- Expenditures

- General Fund Condition in 2019‑20

- LAO Comments

- Chapter 2

- Budget Condition Under Two Economic Scenarios

- Demographic Trends

- LAO Comments

- Appendix

Executive Summary

The Budget Is in Remarkably Good Shape. It is difficult to overstate how good the budget’s condition is today. Under our estimates of revenues and spending, the state’s constitutional reserve would reach $14.5 billion by the end of 2019‑20. In addition, we project the Legislature will have an additional $14.8 billion in resources available to allocate in the 2019‑20 budget process. The Legislature can use these funds to build more budget reserves or make new one‑time and/or ongoing budget commitments. By historical standards, this surplus is extraordinary.

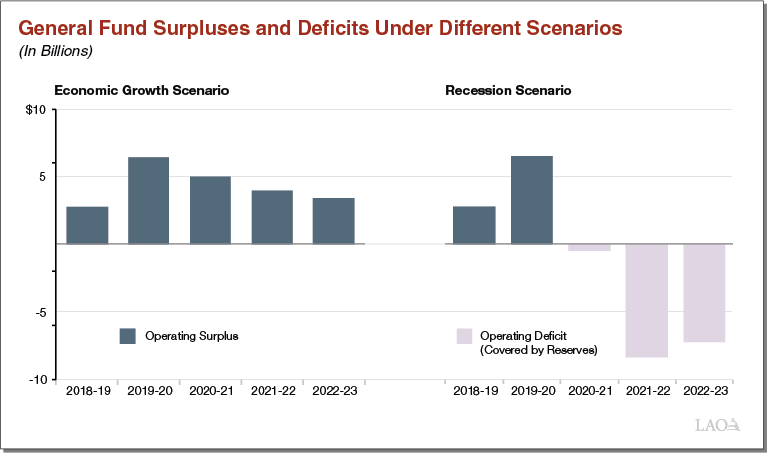

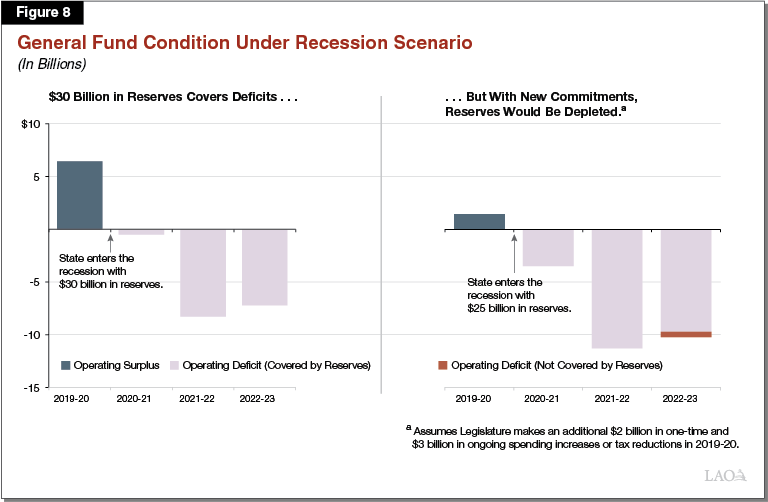

Longer‑Term Outlook Is Positive. The nearby figure displays our longer‑term General Fund outlook under two different scenarios and assuming current law and policies stay the same. The first scenario shows continuing economic growth and the second shows a recession beginning in 2020‑21. If the economy continues to grow, as shown on the left side of the figure, the state has operating surpluses averaging around $4.5 billion per year, but declining over time. In the recession scenario, as shown on the right side, the state has enough reserves to cover its deficits over the outlook period.

With More Commitments, Reserves Might Not Fully Cover the Budget Problem. Both of these scenarios assume the Legislature makes no new commitments (such as spending increases or tax reductions) in 2019‑20 or later. That is, under these scenarios, the Legislature would use all of the nearly $15 billion in available resources in 2019‑20 to build more reserves (reaching a total reserve level of about $30 billion by the end of 2019‑20). If the Legislature makes new ongoing commitments in 2019‑20, however, reserve levels under a recession scenario would be lower and the state would face higher operating deficits. Depending on the extent of these commitments, reserves might not fully cover a budget problem that emerges during a recession.

More Reserves Would Be Needed to Mitigate Reductions to School Funding. In our Fiscal Outlook publications, we assume the state funds schools and community colleges at their minimum level. More explicitly, this means under our assumptions that General Fund spending on K‑14 education declines even as the state maintains other programmatic spending using reserves. This assumption is in keeping with the publication’s aim to show spending under current law and policy, which generally has been to fund schools and community colleges at the minimum required level. If instead the Legislature wanted to mitigate the impact on schools and spend above the minimum level, the state’s operating deficits would be larger and more reserves would be needed to cover the budget problem.

The State’s Budget Condition Can Change Quickly. Our office has produced a Fiscal Outlook every year since 1995. In dollar terms, the available surplus for 2019‑20 is easily the largest our office has ever estimated. As a percent of overall revenues, it is second only to the estimated $10.3 billion surplus in 2001‑02, which we projected in November 2000. However, as the state experienced in 2001, these fortunes can change quickly. In the dot‑com bust and ensuing recession, state revenues declined precipitously. The very next year, our Fiscal Outlook found the state’s surplus had disappeared, and instead, the budget faced a deficit of $12.4 billion.

Legislature Has Unique Opportunity to Prepare for Coming Challenges. In the coming years, the budget will face challenges. The most significant risk to our outlook is the economy, which could slow and result in billions of dollars in revenue losses annually. Decisions outside of the Legislature’s control, for example by the federal government or state retirement systems, also can affect the state budget. The $15 billion surplus we anticipate for 2019‑20 gives the Legislature a unique opportunity to prepare for these foreseen—and other unforeseen—challenges still to come.

Chapter 1

Introduction

Each year, our office publishes the Fiscal Outlook in anticipation of the upcoming state budget. The goal of this report is to help the Legislature begin developing the 2019‑20 budget. Chapter 1 of this report provides our assessment of the budget in the near term. In this chapter, we outline the economic trends and assumptions that underpin our revenue and expenditure projections for the upcoming year. Chapter 2 provides our longer‑term outlook—through 2022‑23—for the state budget. Our outlook for the budget relies on two different scenarios: an economic growth scenario and a recession scenario. In Chapter 2, we also discuss demographic trends that affect California’s out‑year budget situation.

Two Important Notes About Report. First, our outlook assesses the state’s General Fund condition under current law and policies. We do not attempt to predict how the state or federal governments will change their policies. Second, our outlook depends on a set of economic assumptions that are subject to uncertainty, particularly in the longer run. When economic conditions turn out to be different (either better or worse) than what we have displayed here, the budget’s actual revenues and expenditures also will be different.

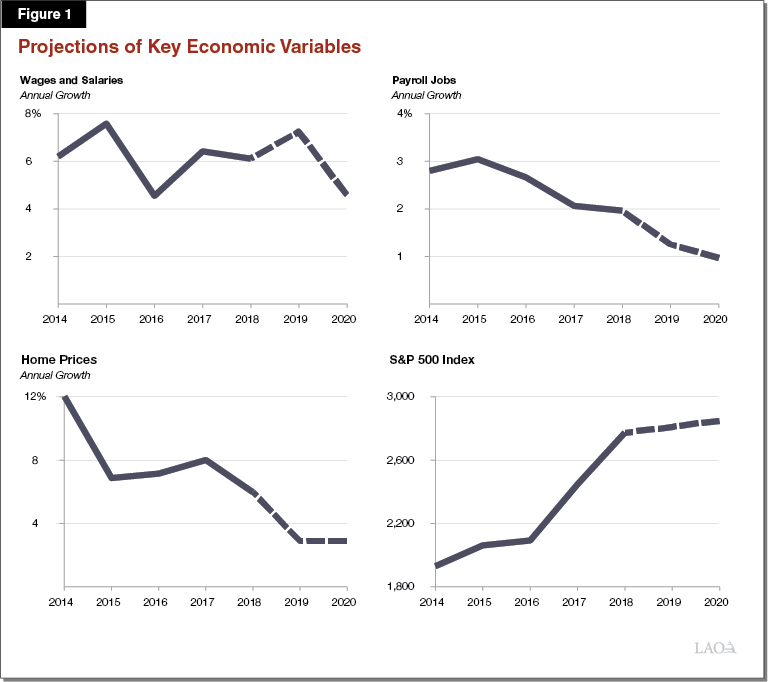

Economy

Our economic outlook is based on the average of a collection of forecasts of the U.S. economy from various institutions and professional economists, as compiled by Moody’s Analytics in September (with an adjustment to the S&P 500 in October). This consensus forecast expects continued growth of the U.S. economy, albeit with some slowing in the pace in the coming years. Based on these expectations, we project continued growth of the California economy. This growth, however, will be tempered by slower job growth and modest weakness in housing. Figure 1 displays key assumptions of our economic outlook.

Steady Wage and Salary Growth. We anticipate total wages and salaries to continue growing at the same above‑average rate as recent years. This strong wage and salary growth is due, in large part, to record low unemployment. With a limited number of people looking for jobs, competition among employers for workers is high. This competition typically forces employers to pay higher wages to attract new workers.

Slower Job Growth. The pace of job growth in California has slowed consistently each year since 2015. We anticipate that this trend will continue through 2020. This is consistent with an expected slowing of national job growth and a limited number of unemployed Californians looking for jobs.

Housing Weakening. The rate of home price growth has slowed consistently throughout 2018. Year‑over‑year growth dropped from 8.5 percent in February to 6.5 percent in September. We anticipate that this trend of slower growth will continue. Our expectation of a slowdown in home price growth reflects the rising supply of homes for sale, tighter mortgage lending, and higher interest rates.

Stock Market Levels Off. After growing rapidly between 2014 and 2017, the stock market has been up and down throughout 2018. The consensus expectation is that stock prices will grow much more slowly moving forward. Earnings of major companies do not appear to support additional rapid growth in stock prices in the near term.

Trade Disputes Create Uncertainties. Over the past year, the U.S. and China have entered a trade dispute in which each country has imposed a series of tariffs (taxes on imported goods) on products commonly traded between them, as well as made threats of additional tariffs. As of now, it is unclear what the ultimate outcome of these threats will be. Should tariffs cover a broad portion of traded goods, businesses that sell many of their goods to China would be impacted. Consumers and businesses also could face higher prices for imported goods. These impacts could, in turn, have negative effects on the stock market and the broader economy.

Revenues

Revenues from California’s three largest taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), sales tax, and corporation tax—have increased 41 percent since 2012‑13. PIT revenues have increased 46 percent over that same period. Strong PIT growth is due to higher‑than‑average wage growth over the period, especially for high‑income earners, and the growth in the stock market. California wage growth from 2012 to 2017 averaged 4 percent (adjusted for inflation), compared to an average of 2.6 percent from 1993 to 2012. The higher tax rates levied on high‑income earners by Propositions 30 and 55 (2012 and 2016) further buoyed state revenue from this earnings growth.

Expect Revenue Growth to Continue in 2019‑20. Figure 2 shows our near‑term revenue outlook. Consistent with our economic assumptions, General Fund revenues continue to increase in 2019‑20—by 5.5 percent. Much of the growth is from the PIT. Continued tightening in the labor market should keep upward pressure on wages and salaries, which make up about two‑thirds of taxable income. We expect taxable wages and salaries to increase by 7 percent in 2018, 7.2 percent in 2019, but slow to 4.4 percent in 2020 due in part to constrained growth at the national level. While we project continued growth in capital gains revenues in 2018‑19, we expect these revenues to decline somewhat in 2019‑20 due to slow growth in the stock market. (More detail on our revenue estimates is available in Appendix Figure 1.)

Figure 2

LAO Near‑Term Revenue Outlook

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Personal income tax |

$93,966 |

$97,865 |

$100,985 |

|

Sales and use tax |

25,007 |

25,870 |

26,819 |

|

Corporation tax |

12,260 |

12,728 |

13,566 |

|

Subtotals |

($131,233) |

($136,463) |

($141,369) |

|

Insurance tax |

$2,575 |

$2,696 |

$2,883 |

|

Other revenues |

1,711 |

1,762 |

1,799 |

|

BSA transfer |

‑4,289 |

‑2,766 |

‑745 |

|

Other transfers |

‑305 |

‑641 |

‑241 |

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$130,925 |

$137,514 |

$145,065 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Expenditures

This section describes major programmatic spending trends we project for the 2019‑20 fiscal year (including recently passed ballot measures). General Fund spending in three major program areas grow, in some cases moderately, from 2018‑19 to 2019‑20: (1) schools and community colleges, (2) health and human services programs, and (3) employee compensation and state retirement programs. However, these areas of growth largely are offset by reductions in one‑time spending from 2018‑19. Consequently, we estimate that General Fund spending growth (under current law and policies) from 2018‑19 to 2019‑20 will be very low. Total spending increases $2.1 billion year over year, a growth rate of 1.5 percent.

Schools and Community Colleges

Proposition 98 Establishes Funding Requirements for Schools and Community Colleges. State funding for schools and community colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by voters in 1988 and modified in 1990. The measure establishes a minimum annual funding requirement, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. The state adjusts the minimum guarantee each year based on various factors including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and K‑12 student attendance. The state meets the minimum guarantee through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue, with increases in property tax revenue generally reducing General Fund costs. The state can provide more funding than Proposition 98 requires, though in practice it typically sets funding close to the guarantee.

General Fund Costs Down $640 Million in 2018‑19. Figure 3 shows our estimate of school and community college funding in the current and upcoming year. For 2018‑19, total K‑14 funding is $68 million below the level assumed in the June budget plan. This decrease mainly reflects our estimate of lower community college enrollment, which reduces the cost of funding apportionments. Total General Fund spending is down even further, decreasing $640 million compared with the June estimate. Most of this drop is the result of our higher local property tax estimates. (General Fund spending in 2017‑18 also is lower by $471 million due to higher property tax revenue reported for that year.)

Figure 3

Estimated Changes in School and Community College Funding

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|||||

|

June |

November |

Change |

November |

Change From |

||

|

Total Funding |

$78,393 |

$78,325 |

‑$68 |

$80,765 |

$2,440 |

|

|

Fund source: |

||||||

|

General Fund |

$54,870 |

$54,230 |

‑$640 |

$55,447 |

$1,217 |

|

|

Local property tax |

23,523 |

24,096 |

572 |

25,318 |

1,223 |

|

General Fund Costs Increase $1.2 Billion From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20. For 2019‑20, our outlook assumes the Legislature sets funding equal to the minimum guarantee. Under this assumption, total school and community college funding would grow to $80.8 billion, an increase of $2.4 billion (3.1 percent) over the 2018‑19 funding level. The increase in the minimum guarantee is mainly attributable to growth in state revenues. Of the $2.4 billion increase, about half would be covered by higher property tax revenue and half by state General Fund. The year‑over‑year increase in property tax revenue mainly reflects our estimate of continued growth in assessed property values.

$2.8 Billion Available for School and Community College Programs in 2019‑20. After accounting for growth in the guarantee and backing out various one‑time initiatives funded in 2018‑19, we estimate the Legislature would have $2.8 billion available for Proposition 98 programs in 2019‑20. The state could use this funding to cover a 3.1 percent statutory cost‑of‑living‑adjustment and provide a few other previously scheduled augmentations. After providing these increases, about $480 million would remain for other ongoing or one‑time initiatives.

Health and Human Services (HHS)

HHS Spending Increases $1.6 Billion From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20. Under our estimates and assumptions, we project HHS spending would increase by $1.6 billion (4 percent) between 2018‑19 and 2019‑20, driven by cost increases in three programs (partially offset by reductions in other HHS programs):

- Medi‑Cal ($1.4 Billion Increase). Under current law and policy, we estimate that spending on Medi‑Cal would increase by $1.4 billion (6.1 percent) in 2019‑20. The growth is largely explained by (1) our assumption that the tax on managed care organizations (MCO) expires in 2019‑20, consistent with current law; and (2) continued projected growth in the cost per participant. However, year‑over‑year growth in the program is offset somewhat by our assumptions that: (1) caseload declines, consistent with recent trends; and (2) state repayments to the federal government for disputed and disallowed claims slow.

- DDS (Over $300 Million Increase). We estimate spending on the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) would increase by over $300 million (7.4 percent) if current law and policies remain in place in 2019‑20. There are two major reasons for this increase: (1) growth in caseload and utilization and (2) the state minimum wage, which is scheduled to increase to $13 per hour on January 1, 2020.

- IHSS (Roughly $100 Million Increase). Under our assumptions, spending on the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program would increase by around $100 million in 2019‑20. Similar to DDS, the major drivers of this cost increase are related to growing caseload in the program, increases in the number of hours worked per case, and the state’s scheduled increases in the minimum wage. Spending growth in IHSS is offset by our assumption that there would be a 7 percent reduction in service hours when the MCO tax expires in 2019‑20. Without this assumption, IHSS spending would grow by roughly $400 million, an over 10 percent increase, year over year.

Comparing our Estimates of HHS Spending to the Administration. As Figure 4 shows, the administration projects HHS spending will increase $3.8 billion in 2019‑20, over twice our estimate of the increase. The administration does not display its projections of spending at a department level within the HHS area, so we do not know all of the sources of these differences. Given that Medi‑Cal makes up over half of the agency total, it likely is responsible for a sizeable portion of this difference. The box below describes our concerns about the relative lack of detail on these estimates provided by the administration. For 2018‑19, we estimate HHS spending will be nearly $600 million lower than the budget assumed in June. This reduction primarily reflects reduced payments to the federal government for disputed claims based on information the state received since the administration’s projections were developed.

Administration Provides Little Detail in HHS Spending Projections, Creating Challenges and Uncertainty

We are concerned that the Legislature does not have adequate information about the administration’s long‑term projections for General Fund spending on Health and Human Services (HHS) programs. In other areas of the budget, the Legislature often has better information about the executive branch’s assumptions, methods, and baseline multiyear projections. For example, while our office and the administration regularly have different projections of state revenues, we understand the underlying differences in our respective methodologies that lead to these differences. In HHS, the administration does not make its long‑term projections for individual programs available for Legislative review. Not having basic information about the administration’s program‑level out‑year estimates and projections makes assessing their reasonableness difficult for the Legislature. It also makes it challenging for us to check our own assumptions. As the Legislature begins the 2019‑20 budget process, we recommend asking the administration for more detail on its multiyear spending estimates and assumptions in HHS.

Figure 4

Comparing LAO and DOF Estimates of HHS Spending

Through 2019‑20

(Dollars in Billions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

DOF Estimate (June 2018) |

$35.5 |

$39.3 |

$43.1 |

|

Year‑over‑year growth |

— |

3.8 |

3.8 |

|

Percent growth |

— |

10.6% |

9.7% |

|

LAO Estimate (November 2018) |

$35.5 |

$38.7 |

$40.3 |

|

Year‑over‑year growth |

— |

3.2 |

1.6 |

|

Percent growth |

— |

8.9% |

4.0% |

|

HHS = Health and Human Services. |

|||

Uncertainty in These Estimates. Our expenditure estimates for these HHS programs depend on our assumptions about policy, cost, and caseload changes. There are two key sources of uncertainty in these assumptions. First, there are uncertainties we know about—for example, price and caseload growth could be higher or lower than we anticipate. Second, there are risks that we cannot anticipate. In recent years the state has experienced a few large, unexpected cost increases in HHS spending, most notably in the Medi‑Cal program. These unanticipated cost increases have resulted in our prior projections being too low. We do not have enough information to know whether an unexpected cost increase will occur again in 2019‑20 and our estimates do not attempt to quantify this possibility.

Other Spending

Spending in Employee Compensation and Retirement Increase $2 Billion in 2019‑20. We estimate that General Fund salary and benefit costs for current employees across all state departments will increase by about $800 million from 2018‑19 to 2019‑20. Based on existing labor agreements, most state employees will receive pay increases in 2019‑20 ranging from 2 percent to 5 percent of pay. Salary increases also increase state costs for benefits that are paid for as a percentage of pay (such as pensions, prefunding retiree health benefits, Social Security, and Medicare). A large share of estimated General Fund employee compensation cost increases in 2019‑20 are due to provisions of the one‑year agreement with correctional officers—including a 5 percent pay increase—ratified earlier this year. Correctional officers and their managers represent about 40 percent of the state’s General Fund payroll costs. In addition, we estimate that the state’s costs for retirement programs (including pension and health benefits for retired state employees and pension benefits for teachers) will be about $1 billion higher in 2019‑20.

Spending Increases Offset by Significant One‑Time Spending. Under our assumptions, about $3.6 billion in spending commitments made in the 2018‑19 budget do not carry through to 2019‑20. (To assess whether or not an item is one time, we use the explicit appropriation language in the budget package, although this sometimes differs with language on legislative intent.) Under our assumptions, major one‑time spending in 2018‑19 items include:

- Infrastructure and Equipment. The budget package included $630 million for the State Project Infrastructure Fund, $305 million for deferred maintenance in a variety of program areas, $170 million for flood control infrastructure, $134 million for voting systems, and $100 million for kindergarten facilities.

- Other Major Items. Other major one‑time spending included $500 million for emergency homeless aid block grants, $200 million for hold harmless provisions associated with ending the SSI/SSP cash out policy, and $105 million in unrestricted funding for the University of California.

General Fund Condition in 2019‑20

Figure 5 displays our estimate of the General Fund condition through 2019‑20. Under current law and policies, we estimate 2018‑19 will end with $9.1 billion in discretionary reserves, an increase of $7.2 billion over the level assumed at the time the budget was passed in June. There are two major reasons for this increase across 2017‑18 and 2018‑19: (1) revenues are higher by $5.3 billion and (2) General Fund spending for schools and community colleges is down by about $1.1 billion.

Figure 5

LAO Near‑Term Budget Condition

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$5,657 |

$10,076 |

$10,281 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

130,925 |

137,514 |

145,065 |

|

Expenditures |

126,505 |

137,310 |

139,373 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$10,076 |

$10,281 |

$15,973 |

|

Encumbrances |

1,165 |

1,165 |

1,165 |

|

SFEU balance |

8,911 |

9,116 |

14,808 |

|

Reservesa |

|||

|

SFEU balance |

$8,911 |

$9,116 |

$14,808 |

|

Safety net reserve |

— |

200 |

200 |

|

BSA balance |

11,002 |

13,768 |

14,513 |

|

Total Reserves |

$19,914 |

$23,084 |

$29,521 |

|

aReflects the year‑end balances in each account under current law and policy. SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

2019‑20: $14.8 Billion in Available Resources. Under our estimates of revenues and expenditures, discretionary resources at the end of 2018‑19 would grow by $5.7 billion—to $14.8 billion in 2019‑20. (In this context, “discretionary resources” refers to the estimated end‑of‑year balance in the Special Fund for Economic Resources under our assumptions.) These surplus resources would be available to increase spending, reduce taxes, or increase reserves. The $5.7 billion increase in available resources is the net result of two major factors:

- Total Revenues and Transfers Grow $7.6 Billion. Under our office’s economic assumptions, revenues grow by $5.1 billion between 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. Transfers (which offset revenues) decline year over year, resulting in total growth in revenues and transfers of $7.6 billion overall.

- General Fund Spending Grows by $2.1 Billion. From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20, overall General Fund spending grows only $2.1 billion. As described in the expenditure section, this is the net effect of moderate growth in schools and community colleges, health and human services, and employee compensation and retirement programs, offset by reductions in one‑time spending from 2018‑19.

Constitutionally Required Reserves, Infrastructure Spending, and Debt Payments. Proposition 2 (2014) requires the state to set aside money each year for reserve deposits and debt payments. (In recent years, the Legislature has made additional, optional reserve deposits.) When the state’s constitutional reserve—the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)—reaches a threshold of 10 percent of General Fund taxes, formula‑driven deposits that would bring the balance above this threshold must be spent on infrastructure. For 2019‑20, we estimate the following Proposition 2 requirements:

- BSA Reserve Reaches $14.5 Billion. Under our revenue projections, the state would be required to deposit an additional $745 million into the rainy day fund in 2019‑20. Under these assumptions, the fund would reach $14.5 billion in 2019‑20, 10 percent of General Fund taxes. Consistent with recent state policy, this assumes that previous years’ optional deposits into the BSA count toward the 10 percent threshold.

- Required Infrastructure Spending of $914 Million. Under our assumptions, in 2019‑20, the Constitution would require $914 million to be spent on infrastructure. Under current law, $415 million of this total would be dedicated to fund state capital outlay and $250 million would be available each for rail infrastructure and affordable housing.

- Required Debt Payments of $1.7 Billion. In addition, under our revenue estimates, the state would be required to pay an additional $1.7 billion toward eligible debts. In our outlook, we allocated these funds using recent law and policy. For example, we assume $744 million would be used to repay transportation‑related loans, consistent with current law. We also assume $268 million would be used to continue to implement the state’s plan to prefund retiree health benefits using employer and employee contributions. That said, the Legislature has some flexibility in these allocations and, in the 2019‑20 budget process, could allocate these funds somewhat differently.

Outlook Assumes Current Law and Policies on Budgetary Formulas. All of the estimates in our outlook assume current state policy regarding Proposition 2. Under alternative interpretations of Proposition 2, past optional deposits would not count toward the BSA threshold, and the amount dedicated to infrastructure in 2019‑20 would instead be deposited into the BSA. The box below describes how our outlook treats other statutory and constitutional budget formulas.

Assumptions on Other Budget Formulas

There are three additional constitutional and statutory budget formulas that may affect spending and revenues in 2019‑20. With respect to these formulas, we assume:

- Sales Tax Reductions Are Not Triggered. California has two statutes that trigger reductions in the state’s sales tax rate if balances in discretionary reserves reach a certain threshold. The Department of Finance (DOF) is required to make a determination about whether the conditions are met before November 1st of each year. This year’s DOF letter on the sales tax triggers noted that—under the budget act estimates of revenues and reserve balances—the conditions for neither of these triggers were met. Decisions made by the Legislature in the 2019‑20 budget process will affect whether the provisions are triggered in November 2019.

- Additional Spending for Medi‑Cal Is Not Provided. Proposition 55 (2016) extended tax rate increases on high‑income earners and created a new budgetary formula that produces increased spending requirements for Medi‑Cal under certain conditions. The administration has significant discretion in how to administer these calculations. In 2018‑19, the first year of implementation, the administration’s approach resulted in no additional funding for Medi‑Cal. Decisions made by the Legislature and the administration in the 2019‑20 budget process will affect whether or not the formula results in additional funding requirements for Medi‑Cal.

- Constitutional Spending Limit Is Not Reached. Under the administration’s June 2018 estimates, the state had several billion dollars of “room” under its spending limit in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19. While our estimates of tax revenues are higher than those of the administration during these years, we are unable to produce spending limit estimates because our Fiscal Outlook has a General Fund focus whereas the spending limit formulas include special funds.

The state budget’s many formulas interact with one another. For example, if decisions made by the administration result in additional spending for Medi‑Cal under the provisions of Proposition 55, the likelihood that the state’s sales tax reductions were triggered would be reduced.

LAO Comments

The Budget Is in Remarkably Good Shape. It is difficult to overstate how good the budget’s condition is today. For several years, the state has consistently increased reserve levels in each subsequent budget. Economic conditions continue to improve: unemployment is low and wages are growing. Under our estimates of revenues and spending, the Legislature would have $14.8 billion in resources available to allocate in the 2019‑20 budget process. By historical standards, this surplus is extraordinary. Since 1995, our office has produced an outlook of the upcoming year’s budget condition every year. In dollar terms, the available surplus for 2019‑20 is easily the largest our office has ever estimated. As a percent of overall revenues, it is second only to the estimated $10.3 billion surplus in 2001‑02, which we projected in November 2000.

The State’s Budget Condition Can Change Quickly. While our current projections suggest the state’s economic and budgetary situations are very strong, these fortunes can change quickly. In fact, this is precisely what occurred after we published our Fiscal Outlook at the end of 2000. As a result of the dot‑com bust and ensuing recession in 2001, state revenues declined precipitously. The very next year, looking to budget year 2002‑03, our Fiscal Outlook found the state’s surplus had disappeared, and instead, the budget faced a deficit of $12.4 billion for the upcoming year. In light of these budgetary uncertainties, in the next section, we consider how the budget’s multiyear outlook would fare under varying economic conditions.

Chapter 2

In this chapter, we discuss the condition of the budget over the longer term, through 2022‑23. First, we present our estimates of revenues, spending, and the condition of the General Fund under two different economic scenarios. (The economy is the key source of uncertainty in our budgetary projections.) Second, we discuss the fiscal implications of statewide demographic trends that affect the budget now and into the future.

Budget Condition Under Two Economic Scenarios

Economy

Economic Assumptions in This Chapter. Our spending and revenue projections in this chapter are based on two different sets of economic conditions:

- Growth Scenario. In this scenario, we assume the economy continues to grow. Job growth slows as the economy reaches full employment. Wage growth overall also slows, but remains strong in some industries, such as professional and technical services (for example, lawyers, engineers, and computer programmers) and in the technology sector (for example, software development and data processing). We also assume a relatively flat stock market.

- Recession Scenario. In this scenario, we assume a recession begins in the third quarter of calendar year 2020, based on Moody’s Analytics “moderate” recession scenario. (This scenario is not based on a recent historical example, but rather a model of one possible recession scenario that Moody’s believes could materialize in the coming years.) Under this scenario, GDP drops by 2.25 percent over four quarters, starting at the beginning of 2020‑21. This scenario also assumes the S&P 500 declines by one‑third over the course of the recession. This recession scenario is relatively short‑lived—the economy begins to recover at the start of 2021‑22.

Revenues

Revenue Situation Assuming Continued Economic Growth. Under our growth scenario, General Fund revenues and transfers grow from $137.5 billion in 2018‑19 to $159.3 billion in 2022‑23. This represents a moderate 3.8 percent average annual growth rate over the period. We attribute this to moderate growth in personal income tax (PIT) revenues, which grow just less than 3 percent over the period (which is relatively weak by recent standards). This reflects our assumptions of: (1) slowing growth in wages and salaries and (2) a relatively flat stock market. Growth in the corporate tax is much stronger at 5.5 percent over the period. We attribute this to the consensus expectation that corporate profits continue to grow steadily. (The Appendix contains more information on our revenue outlook under both scenarios.)

Revenues in the Recession Scenario. Under the recession scenario, revenues would decline year over year by close to $5 billion in both 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, respectively. (Compared to the economic growth scenario, the total revenue loss would be roughly $46 billion over the outlook period.) Much of these reductions would be driven by declines in the PIT. Under our assumption that the economy starts to recover at the start of 2021‑22, revenues grow again in 2022‑23.

Scenarios Represent Two of Many Possible Outcomes. The scenarios presented in this chapter are two of many possible economic outcomes that could occur over the next five years. Our uncertainty about the economy’s condition—and therefore revenue performance—increases throughout the period. Through 2018‑19, revenues could be a few billion dollars higher or lower than our estimates. In 2019‑20, revenues could be several billions of dollars different. In the out‑years of our projections, revenues could be tens of billions of dollars lower than our recession scenario and several billions of dollars above our growth scenario.

Spending in Economic Growth Scenario

This section describes trends in General Fund spending assuming the economy continues to grow. As noted earlier, we assume current law and policies stay in place.

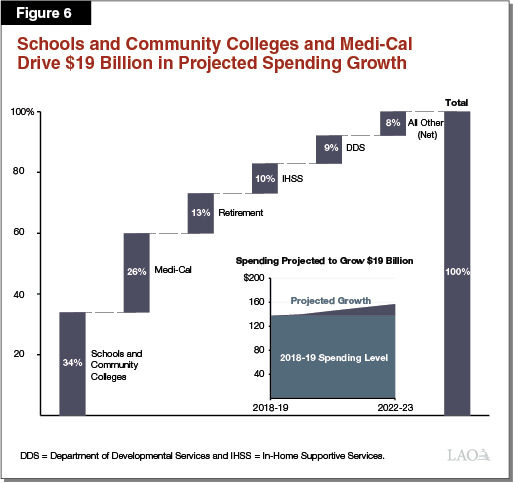

Overall General Fund Spending Grows $19 Billion (3.3 Percent Annually) Over the Outlook Period. Assuming current law and policies stayed in place, we project General Fund spending would increase $19 billion over the period (averaging 3.3 percent per year), as Figure 6 shows. Together, schools and community colleges and Medi‑Cal account for 60 percent of this growth. (These programs also account for well over half of the budget.)

Schools and Community Colleges Grow an Average of 2.9 Percent. The constitutional minimum level of funding for schools and community colleges is determined by a set of formulas (under the rules of Proposition 98). In our growth scenario, General Fund spending on schools and community colleges grows by an average of 2.9 percent over the period. This growth rate is relatively low, reflecting slightly negative changes in attendance and modest growth in revenues over the forecast period. (Overall, school and community college funding—including local property tax revenue—grows at about 3.4 percent per year.)

Medi‑Cal Grows an Average of 5.1 Percent. Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, accounts for 26 percent of overall growth in our outlook. In our growth scenario, spending on Medi‑Cal increases by an average of 5.1 percent annually. Similar to other health and human services programs, Medi‑Cal recently has been growing faster than much of the rest of the budget. This largely has been due to (1) rising caseload and costs per beneficiary, (2) scheduled reductions in federal funding (as the federal share of costs for Medi‑Cal’s optional expansion population has declined), and (3) various technical adjustments. The growth we project in Medi‑Cal through 2022‑23 is somewhat lower than recent experience, however. There are three main reasons for this:

- Limited Growth in Caseload Expected. Recently, Medi‑Cal caseload has begun to slowly decline as the economy has continued to grow. Over the outlook period, we assume caseload in the program continues a very slow decline initially and is essentially flat in later years, which dampens cost growth.

- Changes in Federal Funding. In recent years, the state share of costs has been increasing for Medi‑Cal’s optional expansion as a result of scheduled reductions in federal matching funds. Similarly, in the next couple of years, the state’s share of costs for the Children’s Health Insurance Program also will increase as the federal share declines. These increasing state shares have resulted in higher‑than‑otherwise General Fund growth rates in these programs. These state costs, however, will stop increasing in 2021‑22 when the federal shares reach their scheduled minimums. As a result, the year‑to‑year growth rates will subside.

- Lessening Effects of Technical Adjustments. Finally, our outlook assumes that increased spending related to many of the technical adjustments in recent years are one time or will be reduced in the future. (Technical adjustments include the required repayment of federal funds.) These assumptions result in lower year‑over‑year growth in General Fund spending relative to recent years.

Three Other Programs Account for Most of Remaining Growth. Three other—smaller—programs account for most of the remaining growth over our outlook period. These are:

- Retirement Programs. Over the period, the state’s retirement programs—including pension benefits for retired state employees (CalPERS); pension benefits for teachers (CalSTRS); and other post‑employment benefits, namely health benefits for retirees—account for 13 percent of the total increase in underlying spending. In CalPERS and CalSTRS, these increases largely reflect the boards’ changes in assumptions regarding investment returns and other demographic changes. For retiree health, these increases reflect rising health premiums and the fact that state retirees are living longer in retirement.

- In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS). The IHSS program accounts for about 3 percent of General Fund costs today, but over the outlook period is responsible for 10 percent of total growth. We can attribute this growth to three major factors: growing caseload in the program; increases in the number of hours per case; and the state minimum wage, which is scheduled to continue increasing over the outlook period.

- Department of Developmental Services (DDS). DDS also is responsible for about 3 percent of General Fund spending today, but 9 percent of overall spending growth over the outlook period. Similar to IHSS, the major reasons for these cost increases are growth in caseload, use of services, and the state minimum wage.

Required Spending on Debt and Infrastructure. Under the rules of Proposition 2 (2014), the Constitution requires the state to: (1) spend minimum amounts on repaying certain debts, (2) deposit money into reserves, and (3) spend more on infrastructure when reserves reach a certain threshold. These amounts are determined by a series of formulas. Assuming the economy grows and current law and policies stay in place, state reserves will have reached their maximum level in 2019‑20 under our revenue assumptions. In 2019‑20 and the years that follow, the state would be required to spend roughly $800 million per year on infrastructure. In addition, from 2019‑20 to 2022‑23, the state would be required to spend an average of $1.3 billion per year to pay down certain eligible debts. (In our outlook, we assume an allocation of these funds using recent law and policy.)

Spending in Recession Scenario

This section describes our assumptions and estimates on spending in a variety of program areas across the budget in a recession.

Lower Spending on Schools and Community Colleges. The formulas determining school and community college funding tend to result in lower spending when revenues and personal income are declining and higher spending when the opposite is true. In our recession scenario, in which revenues and personal income both decline, the minimum funding level for K‑14 education also declines. We assume the Legislature funds schools and community colleges at this lower level (as has occurred in past recessions). This means that, in our recession scenario, General Fund spending on K‑14 education declines from a high of $55.6 billion in 2019‑20 to a low of $51.2 billion in 2021‑22. (See the Appendix for more detail on these spending estimates.)

Lower Spending on Debt and Infrastructure. In the recession scenario, we assume the state suspends required deposits into reserves and stops making infrastructure payments (under the Constitution’s budget emergency rules). Even in a budget emergency, however, the state must continue to make required debt payments. As a result, relative to the growth scenario, state spending on infrastructure would be lower by roughly $800 million per year, but the state would continue to make debt payments (although, under the formulas, these required amounts would be a few hundred million dollars lower).

Higher Spending on Some Caseload‑Driven Programs. For some programs, caseload increases when the state enters a recession (usually because unemployment increases or wages decline). As a result, absent policy changes, the state faces higher costs for these programs. Three programs in particular experience quantifiable cost increases as a result of changes in the economy. They are: Medi‑Cal; CalWORKs, which provides cash assistance and services to low‑income individuals; and child care. Across these three programs, relative to the growth scenario, we estimate the state would face higher costs of roughly $1 billion in 2021‑22 in the recession scenario (and somewhat lower cost increases in other years).

All Other Program Costs Assumed the Same in Recession Scenarios. Relative to the growth scenario, we keep all other programs’ spending levels the same in the recession scenario. We understand that, in a real recession, the Legislature would change spending in these programs—particularly those over which the Legislature has more control. The aim of this publication, however, is to show how the budget would fare assuming current policies stayed in place. To be clear, this means we:

- Assume Cost‑of‑Living Increases Remain in Place. Consistent with recent practice, we have assumed a variety of programs receive cost‑of‑living adjustments across the period. This includes: increases in employee compensation (which we adjust for inflation after current bargaining agreements expire), base funding increases for universities, and discretionary increases for the judicial branch. We do not change these assumptions in the recession scenario.

- Assume Minimum Wage Goes into Effect as Scheduled. A law passed in 2016 (Chapter 4 of 2016 [SB 3, Leno]) increases California’s statewide minimum wage over a period of several years. Under the current schedule, the minimum wage for most employees is scheduled to increase to $12 per hour on January 1, 2019, to $13 in January 2020, and to $14 in January 2021. For the purposes of our recession scenario, we assume these minimum wage increases go into effect as scheduled. (In the event of a recession, the Governor has some discretion to pause these increases. For example, if the Governor paused the increase scheduled to occur at the beginning of 2021—so that the minimum wage remained at $13 per hour in 2021—it would save the state, on net, roughly $100 million to $200 million in 2020‑21.)

General Fund Condition

In this section we show the budget’s bottom line condition under the two economic scenarios.

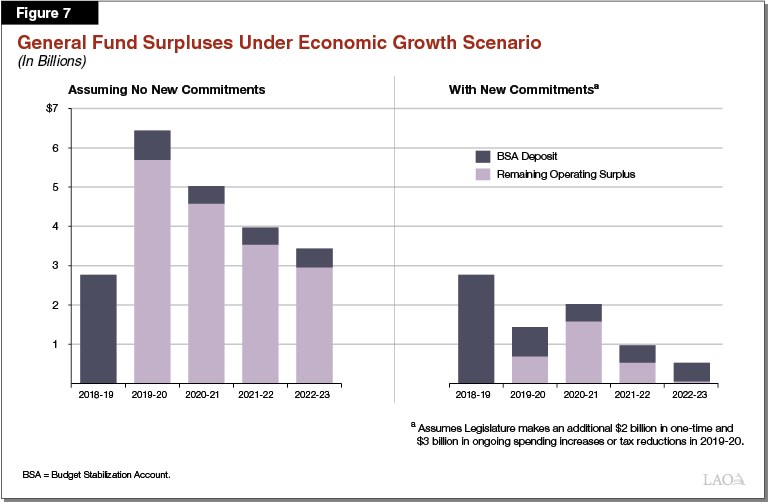

General Fund Surpluses Under Growth Scenario. Figure 7 displays our estimates over the outlook period of General Fund operating surpluses (the difference between incoming revenues and estimated spending). If current law and policies were unchanged (left side of the chart), these surpluses would average around $4.5 billion per year, declining over time. Figure 7 also shows that—pursuant to the rules of Proposition 2 and under current policy—the state would continue to make deposits into the state’s Budget Stabilization Account each year.

General Fund Operating Surpluses Decline With New Commitments. While our outlook assumes they remain the same, we know that the state’s law and policies will change over this period. To that end, for illustrative purposes, the right side of Figure 7 displays the state’s operating surpluses if additional commitments were made in 2019‑20. In particular, the figure assumes that the Legislature made an additional $2 billion in one‑time and $3 billion in ongoing commitments (but no additional commitments in 2020‑21 and beyond). As the figure shows, with these commitments, operating surpluses would decline over the outlook period such that they would be gone by the last year of the outlook.

In the Recession Scenario, $30 Billion in Reserves Would Be Sufficient to Cover Deficits. Figure 8 displays the budget’s condition assuming the recession scenario occurs. On the left side, we show the budget’s condition if the state enters the recession with $30 billion in reserves. (This would mean the Legislature uses all of the nearly $15 billion in available resources in 2019‑20 to build more reserves and makes no new commitments.) We also assume the Legislature funds schools and community colleges at the minimum level, meaning General Fund spending would decline year over year, as we described earlier. In this situation, the state would have plenty of reserves to cover its deficits. In fact, the state would end the 2022‑23 fiscal year with $13.5 billion in reserves—enough to cover additional deficits if the recession were worse or to cover any remaining deficits that occurred outside the outlook period.

With More in Commitments, Reserves Would Not Fully Cover the Budget Problem. The right side of Figure 8 displays the budget’s condition under the recession scenario if the Legislature makes additional commitments in 2019‑20. (As we assumed in the growth scenario, the figure assumes that the Legislature made an additional $2 billion in one‑time and $3 billion in ongoing commitments.) Under these assumptions, the state would enter the recession in 2020‑21 with $25 billion in reserves and operating deficits would grow by $3 billion each year. By the end of the period, the state would have exhausted its reserves and would require solutions—such as spending reductions, tax increases, or cost shifts—to cover a $500 million budget problem.

More Reserves Would Be Needed to Mitigate Reductions to School Funding. In our Fiscal Outlook publications, we assume the state funds schools and community colleges at their minimum level. More explicitly, this means, under our assumptions, General Fund spending on K‑14 education declines even as the state maintains other programmatic spending using reserves. This assumption is in keeping with the publication’s aim to show spending under current law and policies, which has generally been to fund schools and community colleges at the minimum required funding level. If instead the Legislature wanted to mitigate the impact on schools and spend above the minimum level, the state’s operating deficits would be larger and more reserves would be needed to cover the budget problem. The box below contains more information on reserves and school spending.

Reserves and School Spending

Rainy Day Fund Deposits Do Not Affect School Spending. State spending on schools is determined by a series of formulas. These formulas are unaffected by the constitutional requirements for the state to make reserve deposits into its rainy day fund (governed by Proposition 2 [2014]). Consequently, spending on schools is never lower as a result of these reserve deposits. Rather, these deposits result in less revenue available for nonschool programs. As a result, spending on nonschool programs is reduced during the time that reserves are built up.

School Reserves. Proposition 2 also established a specific statewide school reserve account (the Public School System Stabilization Account), which is governed by a separate set of formulas. To date, these formulas have not resulted in any deposits being made into the school reserve. As such, school districts do not have dedicated reserves available to cushion the impact of a recession.

Demographic Trends

California’s Population Is Aging. California’s population is growing older—the average age of Californians has been increasing and is expected to continue to do so. This is occurring as a result of three distinct trends: (1) birth rates are declining, (2) baby boomers are now reaching retirement age, and (3) people are living longer. (Some of these natural changes in demographics are offset or amplified by migration of some groups to and from the state. In recent years, more people left California for other states than moved to the state from other states. These population losses, however, have been much lower than historically.)

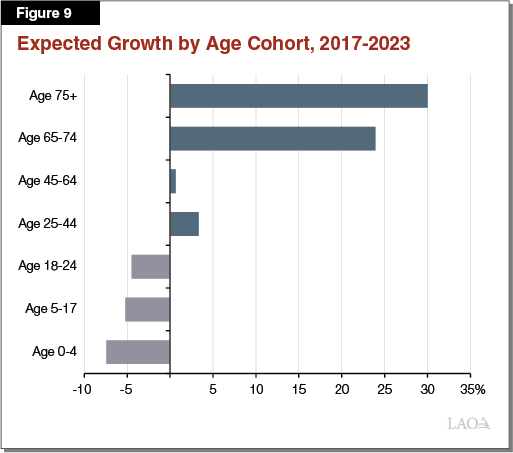

Growth in Population by Age in the Outlook Period. Figure 9 shows how our projected change in population by age group unfolds over our outlook period (2017 through 2023). We expect: (1) the population of children and young adults to decline, (2) the population of those in their prime working years to remain relatively flat, and (3) the population of seniors to increase significantly. Our projections for each of these age cohorts are close to the most recent projections made by the Department of Finance (DOF). However, DOF expects the population of children ages 5 to 17 to increase slightly over the period and young adults (ages 18 to 24) to remain nearly constant.

Fiscal Effects

We expect each of these three demographic trends to have distinct effects on the budget. This section examines the fiscal effects of each of these trends individually and then describes their likely net effect.

Some Cost Increases From Older Population. We expect the growth in the population of older Californians to result in somewhat higher costs for some programs. In particular, an aging population means higher costs for:

- Medi‑Cal, which provides health insurance coverage for low‑income families, seniors, and people with disabilities. In the program, caseload for seniors is expected to increase at a rate of 2.7 percent over the next five years (much higher growth than for any other group). Medi‑Cal’s senior caseload carries higher costs for the state on average, resulting in somewhat higher costs to the program overall.

- IHSS provides supportive services to low‑income seniors and people with disabilities. As such, caseload growth in this program is in part driven by the aging population. Additionally, as individuals live longer, recipients likely will spend more time in the program and require a higher level of service.

- Retiree Health provides medical benefits to retired state employees. The state is paying these benefits in the year they are used by retirees (although the state also is implementing a plan to prefund these benefits for current employees). As more state employees retire and people live longer, the costs associated with providing their health benefits will continue to increase.

That said, overall, demographic trends are not the most important determinant of these programs’ costs. In IHSS and Medi‑Cal, for example, policy changes—such as increases in the state minimum wage and the optional expansion of Medi‑Cal benefits to a broader group of low‑income individuals—result in much larger cost increases than those attributable to demographic shifts. Similarly, for retiree health, another important determinant of program costs is the trend in medical prices.

Somewhat Lower Tax Revenues Possible From Flat Working Age Population. Weak growth of the 45 to 64 age group could hamper growth in state tax revenues because this is the age category that routinely earns the highest wages and salaries. That said, this effect must be considered in light of other demographic shifts in this population. California’s PIT revenues depend, to a large extent, on high‑income earners. As a result, revenues would be much more sensitive to changes in the population of higher‑income people than changes in the overall working age population. In fact, recent data on migration suggest that although California has had net out‑migration among most demographic groups, it has gained among those with higher incomes ($110,000 per year or more) and higher levels of education (graduate degrees).

Growth in General Fund Costs Declines as Growth in Population of Children Slows. In contrast to programs that largely benefit older Californians, lower growth in the state’s population of children results in lower cost growth for other areas of the budget (particularly, schools). Under the rules of Proposition 98, declines in student attendance tend to reduce required funding levels. Over the next few years, we expect attendance to decline somewhat (although not as much as the ages 5 to 17 group). This reduces associated school costs. By comparison, if the school‑age population instead grew at the same rate as the overall population, the state would have to spend additional billions of dollars over the outlook period.

On Net, Demographic Trends Likely Resulting in Lower General Fund Spending Growth. The net effect of an aging population in California has counterintuitive fiscal effects. Many think the aging population is a major driver of increasing General Fund costs, but that view is incomplete. While growth in the population of older Californians likely means higher costs for some programs, declines in the population of children means much lower growth in costs for other programs. In fact, on net over the next few years, the state’s demographic trends are likely resulting in lower, not higher, General Fund cost growth. That said, demographic factors have less effect on the state budget than policy choices and economic conditions.

LAO Comments

Consider Target for Overall Level of Reserves. The budget now has a variety of reserve accounts, including some general purpose accounts and some program specific accounts, like the ones created in 2018‑19 for Medi‑Cal and CalWORKs. Each year we encourage the Legislature to first consider its target level of overall reserves as it builds the budget. In 2019‑20, the state will have nearly $15 billion in its constitutional reserve account. In addition, the Legislature also will be able to use the $15 billion in available resources to build more reserves. In this report, we have found that a $30 billion reserve would be sufficient to cover the entire budget problem associated with Moody’s moderate recession scenario. We also noted that, with new ongoing commitments in 2019‑20, a smaller reserve would be insufficient to fully cover a budget problem.

Consider How to Provide Reserves for Schools. In addition to general purpose reserves, the state has a separate statewide reserve for schools. However, the school reserve has yet to receive any deposits. Our recession scenario assumes schools and community colleges are funded at their constitutional minimum level. That is, in our scenario, general purpose reserves are used solely to maintain nonschool programs. If, instead, general purpose reserves were used to mitigate reductions to schools, additional reserves would be required to cover larger deficits. This raises basic questions about how the Legislature would like to build reserves for schools and the rest of the budget in anticipation of the next recession.

Legislature Has Unique Opportunity to Prepare for Coming Challenges. In the coming years, the budget likely will face a variety of challenges. An obvious example is the economy, which could slow. Decisions by the federal government will affect the state budget, economy, and tax revenues. Similarly, future decisions by the state’s retirement systems can change state costs by billions of dollars—an area of spending that the Constitution places largely outside of the Legislature’s control. Finally, the state always faces the risk of confronting a natural disaster that could carry high costs for the people of California and their government. The $15 billion surplus we anticipate for 2019‑20 gives the Legislature a unique opportunity to prepare for coming challenges. As such, we would encourage the Legislature to allocate a significant portion of the available resources to one‑time purposes and building higher reserve levels.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1

LAO November 2018 Revenue Outlook

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

Growth Scenario |

Estimates |

Outlook |

Average Annual Growtha |

|||||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|||

|

Personal income tax |

$93,966 |

$97,865 |

$100,985 |

$103,509 |

$106,278 |

$109,644 |

2.9% |

|

|

Sales and use tax |

25,007 |

25,870 |

26,819 |

27,753 |

28,596 |

29,268 |

3.1 |

|

|

Corporation tax |

12,260 |

12,728 |

13,566 |

14,412 |

15,111 |

15,780 |

5.5 |

|

|

Subtotals |

($131,233) |

($136,463) |

($141,369) |

($145,674) |

($149,985) |

($154,692) |

(3.2%) |

|

|

Insurance tax |

$2,575 |

$2,696 |

$2,883 |

$3,007 |

$3,059 |

$3,129 |

3.8% |

|

|

Other revenues |

1,711 |

1,762 |

1,799 |

1,802 |

1,801 |

1,797 |

0.5 |

|

|

BSA transfer |

‑4,289 |

‑2,766 |

‑745 |

‑445 |

‑435 |

‑478 |

‑35.5 |

|

|

Other transfers |

‑305 |

‑641 |

‑241 |

‑161 |

57 |

202 |

N/A |

|

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$130,925 |

$137,514 |

$145,065 |

$149,877 |

$154,465 |

$159,343 |

3.8% |

|

|

Percent change |

— |

5% |

5% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

— |

|

|

Recession Scenario |

Estimates |

Outlook |

Average Annual Growtha |

|||||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|||

|

Personal income tax |

$93,966 |

$97,865 |

$100,985 |

$96,286 |

$92,446 |

$96,505 |

‑0.3% |

|

|

Sales and use tax |

25,007 |

25,870 |

26,819 |

26,804 |

26,842 |

27,775 |

1.8 |

|

|

Corporation tax |

12,260 |

12,728 |

13,566 |

12,363 |

10,730 |

13,290 |

1.1 |

|

|

Subtotals |

($131,233) |

($136,463) |

($141,369) |

($135,452) |

($130,019) |

($137,569) |

(0.2%) |

|

|

Insurance tax |

$2,575 |

$2,696 |

$2,883 |

$3,007 |

$3,059 |

$3,129 |

3.8% |

|

|

Other revenues |

1,711 |

1,762 |

1,799 |

1,802 |

1,801 |

1,797 |

0.5 |

|

|

BSA transfer |

‑4,289 |

‑2,766 |

‑745 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Other transfers |

‑305 |

‑641 |

‑241 |

‑161 |

57 |

202 |

N/A |

|

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$130,925 |

$137,514 |

$145,065 |

$140,100 |

$134,935 |

$142,697 |

0.9% |

|

|

Percent change |

— |

5% |

5% |

‑3% |

‑4% |

6% |

— |

|

|

aFrom 2018‑19 to 2022‑23. BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||||||||

Appendix Figure 2

Spending Through 2019‑20

LAO November 2018 General Fund Estimates (Dollars in Millions)

|

Estimates |

Outlook |

||||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From |

||

|

Major Education Programs |

|||||

|

Schools and community collegesa |

$52,911 |

$54,230 |

$55,447 |

2.2% |

|

|

University of California |

3,549 |

3,729 |

3,567 |

‑4.3 |

|

|

California State University |

3,474 |

3,655 |

3,752 |

2.6 |

|

|

Financial aid |

1,188 |

1,234 |

1,318 |

6.8 |

|

|

Child care |

1,019 |

1,378 |

1,465 |

6.3 |

|

|

Major Health and Human Services |

|||||

|

Medi‑Cal |

20,345 |

22,563 |

23,943 |

6.1 |

|

|

Department of Developmental Services |

4,144 |

4,487 |

4,819 |

7.4 |

|

|

In‑Home Supportive Services |

3,444 |

3,813 |

3,897 |

2.2 |

|

|

SSI/SSP |

2,840 |

2,793 |

2,800 |

0.3 |

|

|

Department of State Hospitals |

1,485 |

1,673 |

1,631 |

‑2.5 |

|

|

CalWORKs |

438 |

201 |

268 |

33.3 |

|

|

Major Criminal Justice Programs |

|||||

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

11,068 |

11,630 |

11,910 |

2.4 |

|

|

Judiciary |

1,743 |

1,888 |

2,205 |

16.8 |

|

|

Debt service on state bonds |

5,259 |

5,532 |

5,380 |

‑2.8 |

|

|

Other programs |

13,598 |

18,504 |

16,972 |

‑8.3 |

|

|

Totals |

$126,505 |

$137,310 |

$139,373 |

1.5% |

|

|

aReflects the General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. |

|||||

Appendix Figure 3

Spending by Major Area Through 2022‑23

LAO November 2018 General Fund Estimates(Dollars in Millions)

|

Growth Scenario |

Estimates |

Outlook |

Average Annual |

|||||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|||

|

Education Programs |

||||||||

|

Schools and community collegesb |

$52.9 |

$54.2 |

$55.4 |

$57.1 |

$58.9 |

$60.7 |

2.9% |

|

|

Other education |

9.2 |

10.0 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

10.7 |

10.9 |

2.2 |

|

|

Health and Human Services |

32.7 |

35.5 |

37.4 |

40.0 |

42.1 |

44.3 |

5.7 |

|

|

Criminal Justice |

12.8 |

13.5 |

14.1 |

14.2 |

14.4 |

14.6 |

1.9 |

|

|

Debt service on state bonds |

5.3 |

5.5 |

5.4 |

6.0 |

6.4 |

6.2 |

3.0 |

|

|

Other programs |

13.6 |

18.5 |

17.0 |

17.6 |

18.5 |

19.7 |

1.5 |

|

|

Totals |

$126.5 |

$137.3 |

$139.4 |

$145.3 |

$150.9 |

$156.4 |

3.3 |

|

|

Percent change |

— |

8.5% |

1.5% |

4.2% |

3.9% |

3.6% |

— |

|

|

Recession Scenario |

Estimates |

Outlook |

Average Annual |

|||||

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|||

|

Education Programs |

||||||||

|

Schools and community collegesb |

$52.9 |

$54.2 |

$55.4 |

$53.2 |

$51.2 |

$54.1 |

— |

|

|

Other education |

9.2 |

10.0 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

10.7 |

10.9 |

2.2% |

|

|

Health and Human Services |

32.7 |

35.5 |

37.4 |

40.3 |

42.9 |

45.2 |

6.2 |

|

|

Criminal Justice |

12.8 |

13.5 |

14.1 |

14.2 |

14.4 |

14.6 |

1.9 |

|

|

Debt service on state bonds |

5.3 |

5.5 |

5.4 |

6.0 |

6.4 |

6.2 |

3.0 |

|

|

Other programs |

13.6 |

18.5 |

17.0 |

16.5 |

17.6 |

18.8 |

0.4 |

|

|

Totals |

$126.5 |

$137.3 |

$139.4 |

$140.6 |

$143.2 |

$149.9 |

2.2% |

|

|

Percent change |

— |

8.5% |

1.5% |

0.9% |

1.9% |

4.7% |

— |

|

|

aFrom 2018‑19 to 2022‑23. bReflects the General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Note: Program groups are defined to include departments listed in Appendix Figure 2. |

||||||||