LAO Contact

Update 12/3/19: Updated Figure 2

December 14, 2018

Recent Changes to State and County IHSS Wage and Benefit Costs

Introduction

Recent legislation created various options for counties to implement In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) provider wage and benefit increases. Specifically, recent state minimum wage increases and budget-related legislation adopted in 2017‑18 instituted both temporary and permanent changes to how counties can increase IHSS provider wages and benefits with varying effects on state and county costs. In this post, we (1) explain how the scheduled state minimum wage increases impact IHSS wages and state and county costs, (2) describe the recent temporary and permanent changes to the state and county cost-sharing structure for IHSS wage and benefit increases, and (3) explain how these changes could impact county wage decisions and costs for the state.

Background

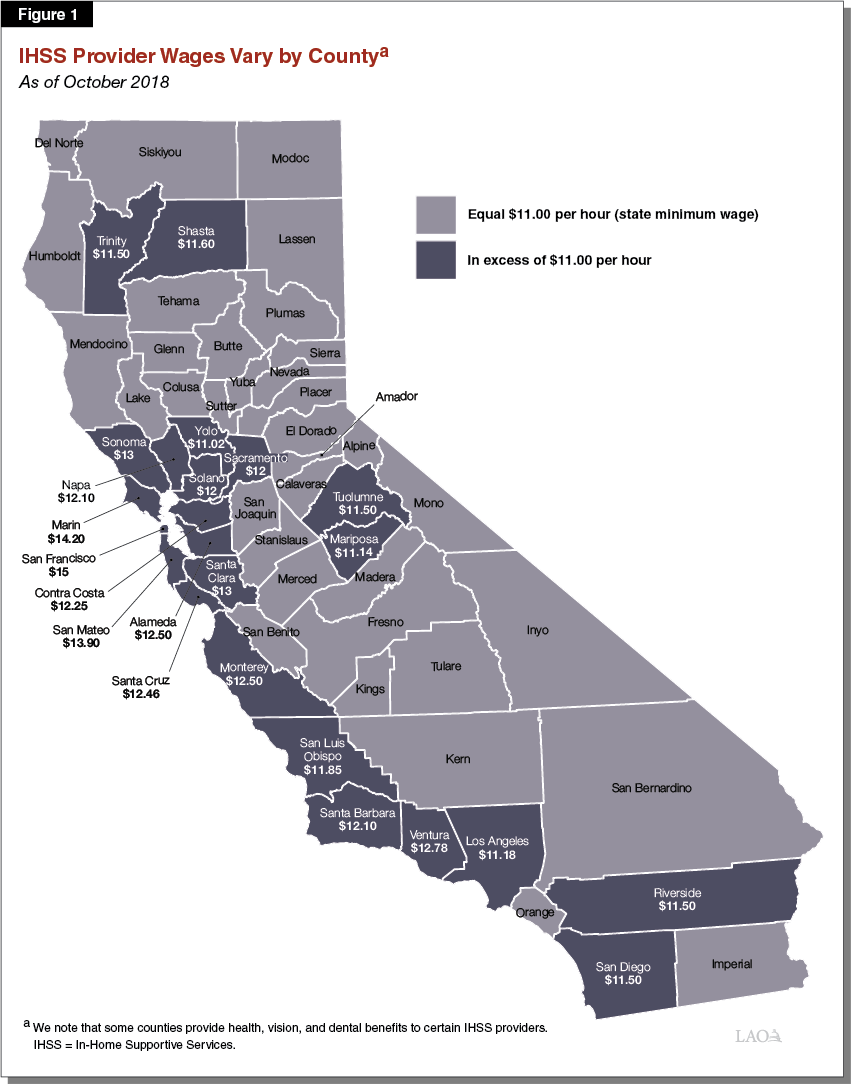

IHSS Wages and Benefits Established by Local Collective Bargaining and State Minimum Wage. IHSS provider wages mainly increase in two ways—(1) through collective bargaining at the local county level, and (2) in response to state minimum wage increases. As shown in Figure 1, IHSS wages vary by county. County wages for IHSS providers must at least equal the state minimum wage. However, counties may provide IHSS wages above the state minimum wage—largely as a result of local collectively bargained agreements. (We note that, while not common, county IHSS provider wages can also be established through locally established minimum wage ordinances.) As of October 1, 2018, 23 counties provide IHSS wages above the state minimum wage ($11.00 per hour in 2018). In addition, some counties make contributions towards health, vision, and dental benefits for certain IHSS providers. These benefit contributions are usually negotiated at the local level and vary in scope, cost, and eligibility requirements.

Recent Changes to IHSS Cost-Sharing Structure. Historically, the IHSS cost-sharing structure was based on a share-of-cost model. Counties were responsible for 35 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS service costs and 30 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS administrative costs. The state was responsible for the remaining 65 percent of IHSS service costs and 70 percent of IHSS administrative costs. Between 2012‑13 and 2016‑17, the historical share of cost model was replaced with an IHSS county maintenance-of-effort (MOE). The MOE essentially eliminated the counties’ share of IHSS costs and replaced it with a set amount that each county would pay for IHSS. In 2017‑18, that IHSS MOE was eliminated and replaced with a new MOE financing structure—referred to as the 2017 IHSS MOE. Under the 2017 IHSS MOE, county costs for 2017‑18 were rebased to roughly reflect the historical county share-of-cost of IHSS as estimated in 2017‑18 (35 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS service costs and 30 percent of the nonfederal share of IHSS administrative costs). Moving forward, the IHSS MOE will be adjusted annually by a growth factor and any county costs associated with local wage and benefit increases.

Treatment of Wage and Benefit Costs Under the 2017 IHSS MOE. As a result of the 2017 IHSS MOE financing structure, the determination of IHSS county wage and benefit costs has changed. For instance, under the historical share-of-cost model, counties had a share of costs for all wage and benefit increases. Under the 2017 IHSS MOE, however, the state is fully responsible for the nonfederal costs of IHSS wage increases due to state minimum wage increases. Nonfederal costs associated with locally established wage and benefit increases will continue to be shared between the state and counties based on the historical nonfederal cost-sharing ratios for IHSS service costs, up to the state participation cap ($12.10 per hour in 2018). Specifically, the state will pay for 65 percent of the nonfederal costs of county IHSS wages and benefits up to the state participation cap, while counties are responsible for the remaining 35 percent. If a county’s total IHSS wages and benefits exceed the state participation cap, the county will pay 100 percent of the nonfederal costs for the amount above the state participation cap.

Another example of how the 2017 IHSS MOE differs from the historical share-of-cost model is how county IHSS costs are adjusted in future years. Under the historical share-of-cost model, the county share of total IHSS program costs was the same year-to-year. As a result, total county costs would generally increase or decrease as total IHSS costs increased or decreased. In other words, to the extent that total IHSS costs, including wage and benefit costs, increased (or decreased) as a result of changes in the number of recipients, total number of hours worked, or other key cost drivers, county costs would also increase (or decrease) proportionately. However, under the 2017 IHSS MOE, county costs are adjusted by an annual growth factor and any county costs associated with new locally established wage and benefit increases. To the extent that the MOE growth rate is higher (or lower) than the actual growth in IHSS costs, counties will be responsible for a higher (or lower) share of total IHSS costs relative to the historical county share of cost. (In a later section, we further explain how changes associated with the 2017 IHSS MOE affected state and county share of IHSS wage and benefit costs.)

Ways to Increase IHSS County Provider Wages and Benefits

There are various ways counties can increase IHSS provider wages and benefits—each with varying implications for state and county costs. For example, counties can either keep IHSS wages equal to the state minimum wage or establish IHSS wages above the state minimum wage. Below, we describe in detail the various options counties have to increase IHSS provider wages and benefits and how these options have varying impacts on costs for the state and counties.

Scheduled State Minimum Wage Increases

In 2016, the state passed legislation (Chapter 4 of 2016 [SB 3, Leno]) to increase the statewide minimum wage from $10.50 per hour in 2017 to $15 per hour by January 1, 2022 (increasing by inflation annually in 2023-24 and onwards). These scheduled state minimum wage increases apply to IHSS provider wages in each county. As shown in Figure 2, beginning in 2017, the state minimum wage is expected to increase every year. (We note that in the event of a recession, the Governor has some discretion to pause the increases.) Most recently, on January 1, 2018, the state minimum wage increased from $10.50 per hour to $11.00 per hour. This particular increase resulted in IHSS provider wages increasing in 39 counties.

Figure 2

IHSS Provider Wagers Per State Minimum Wagea

|

2017 |

$10.50 |

|

2018 |

11.00 |

|

2019 |

12.00 |

|

2020 |

13.00 |

|

2021 |

14.00 |

|

2022 |

15.00 |

|

2023 |

15.00 |

|

2024 and onwards |

Increase by inflation |

|

aThe state minimum wage reflects the minimum wage of In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) providers across all counties. In some counties, IHSS provider wages are higher than the state minimum wage primarily due to locally‑negotiated agreements. |

|

State Expected to Pay for the Nonfederal IHSS Costs of State Minimum Wage Increases. While the IHSS MOE obligation for counties is adjusted to include costs associated with locally established wage and benefit increases, it is not adjusted for costs associated with state minimum wage increases. As a result, the state is expected to pay for all the nonfederal costs of state minimum wage increases. State costs for the most recent state minimum wage increase—from $10.50 to $11.00 per hour on January 1, 2018—are estimated to be about $100 million General Fund annually.

Options for Counties to Increase Wages and Benefits Beyond the State Minimum Wage

While counties could keep IHSS wages and benefits at the state minimum wage, counties could also decide to increase IHSS wages and benefits above this level. In that case, county costs would increase as a result of locally established wage and benefit increases. The 2017‑18 budget package established provisions that changed how costs for locally established wage and benefit increases are shared between the state and counties. Specifically, the new wage and benefit provisions (1) increase the cap on state participation in IHSS wage and benefit costs from $12.10 to $1.10 above whatever the state minimum wage is, (2) establish a temporary cost-sharing structure for counties with a total provider wage and benefit amount above $12.10 per hour, and (3) establish an alternative and permanent cost-sharing structure for counties that adopt a “local wage supplement.” (The Department of Social Services released an “all-county letter” in March 2018 that explains the recent changes made to the IHSS MOE, including these new wage and benefit provisions.) While these wage and benefit provisions are complex, they generally mitigate the costs counties would otherwise accrue as a result of establishing local wages and benefits above the state minimum wage. From our conversations with the administration, it is our understanding that these changes were meant to incentivize counties to continue to increase wages above the state minimum wage. Below, we discuss these three new wage and benefit provisions in detail.

Automatic Increases to State Participation Cap on IHSS Wages and Benefits. Historically, the state participation cap was a fixed dollar amount and could only increase further upon a statutory change. However, budget-related legislation in 2017‑18 made it so that the state participation cap increases every time the state minimum wage increases. The state participation cap in 2018 is currently $12.10 per hour, which is $1.10 above the current state minimum wage ($11.00 per hour). Beginning in 2019, the state participation cap will increase at the same time the state minimum wage increases. Specifically, once state minimum wage equals or exceeds $12.00 per hour, the state participation cap will always “float above,” or exceed, the state minimum wage by $1.10. For example, when the state minimum wage reaches $12.00 per hour (scheduled to occur on January 1, 2019), the state participation cap will equal $13.10 per hour (state minimum wage plus $1.10). Once the state minimum wage increases to $15.00 per hour (scheduled to occur on January 1, 2022), the state participation cap will increase to $16.10 per hour.

Temporary State Share of Cost for Counties Above the Current State Participation Cap. As previously mentioned, the state typically only contributes to IHSS wage and benefit costs up to the state participation cap, resulting in counties paying for all nonfederal wage and benefit costs above the state participation cap. The 2017‑18 budget package established a temporary cost‑sharing structure for counties with total wages and benefits above the current state participation cap—$12.10 per hour. Specifically, for these counties the state will share in a portion of costs associated with locally established wage and benefit increases that, in sum, do not exceed 10 percent of a county’s total current wage and benefit level prior to the increases—we refer to this as the “10 percent option” throughout the remainder of this post. Under the 10 percent option, the state’s and counties’ share of cost are based on the historical cost-sharing ratios for nonfederal IHSS service costs (65 percent and 35 percent, respectively). Counties can increase wages and benefits by 10 percent all at once or over a three-year period.

We note that counties can use this 10 percent option up to two times, as long as the wage and benefit increases begin prior to the state minimum wage increasing to $15 per hour (scheduled to occur on January 1, 2022) and other conditions are met. For instance, the second 10 percent option cannot begin until the three-year period for the first option ends. After the 10 percent option expires, the state will revert back to having no share of cost in future locally established wage or benefit increases above the state participation cap for all counties. As of December 1, 2018, eight counties have applied the 10 percent option to locally established wage and benefit increases.

Local Wage Supplement. Beginning in 2017‑18, counties and unions can collectively bargain a local wage supplement, meaning local IHSS provider wages will always exceed the state minimum wage by a fixed dollar amount. A local wage supplement essentially ties future local wage increases to increases to the state minimum wage. For example, if a county adopted a $1.00 wage supplement, its IHSS provider wages will be $1.00 above the state minimum wage in any given year. Under the local wage supplement model, the cost of the first wage supplement is added to a county’s IHSS MOE obligation, which is then adjusted annually by the MOE growth factor. However, the costs for subsequent local wage supplements are not added to a county’s MOE obligation. Unlike the 10 percent option, the local wage supplement model is a permanent change to the traditional state and county cost-sharing structure. In the nearby box, we explain the rules that dictate how the local wage supplement option would be implemented. As of December 1, 2018, nine counties have chosen to apply a local wage supplement to their IHSS wages.

How the Local Wage Supplement Model Works

The local wage supplement model was initially established as a part of the 2017‑18 budget package. In March 2018, additional clarifying language was passed. Below, we walk through the main components of the local wage supplement model as of March 2018.

First, the wage supplement is applied to the highest total wage and benefit amount in place in the county since June 30, 2017. This means counties cannot reduce In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) wages and benefits and then apply the first wage supplement to the lower wage and benefit amount (thereby reducing the amount their maintenance-of-effort is increased).

IHSS wages would continue to increase by the amount of the wage supplement when the total wages and benefits—not including the prior wage supplement—equal or exceed the state minimum wage in any given year.

Examples of How Changes to IHSS Wages and Benefits Impact State and County Costs

Below, we provide examples to demonstrate how the various methods of making changes to IHSS wages and benefits would affect state and county costs. These examples are based on two hypothetical counties with different wage and benefit levels. County A has a wage level of $11.00 per hour, while County B has a wage level of $12.50 per hour. For this example, we assume that neither County A nor County B provide benefits and all of the modeled wage increases occur in 2018. (We note that these examples are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect any county in particular.)

Effect of State Minimum Wage Increases. Currently, IHSS provider wages in County A and County B equal or exceed the state minimum wage—$11.00 per hour in 2018. Absent any local actions, when the state minimum wage increases to $12.00 per hour (scheduled to occur January 1, 2019), wages for IHSS providers in County A would increase by $1.00 per hour. IHSS provider wages in County B, however, would remain the same given that its IHSS provider wages ($12.50 per hour) would still exceed the state minimum wage in 2019. In the case of County A, the state would be fully responsible for the nonfederal costs associated with IHSS provider wages increasing as a result of the state minimum wage increase. Because of this, County A would experience a wage increase that has no impact on their MOE obligation.

Effect of State Participation Cap When IHSS Wages Increase. To the extent that both County A and County B implemented a $1.00 local wage increase sometime in 2018, the state and county share of costs would depend on the level of the state participation cap. As shown in Figure 3, due to the state participation cap, the state and county share of cost for a $1.00 wage increase is different for County A than County B. In the case of County A, its total wage and benefit amount would continue to fall below the current state participation cap after the $1.00 wage increase. As a result, the state would pay for 65 percent of the nonfederal costs associated with the $1.00 wage increase, while County A would pay for the remaining 35 percent. The current wage and benefit level for County B, however, exceeds the state participation cap. As a result, the state would have no share of nonfederal costs for any locally established wage or benefit increase. This means that County B would pay 100 percent of the nonfederal costs associated with the $1.00 wage increase. For both County A and County B, the cost for this one-time wage increase would be added to their MOE obligation, which would be adjusted every year by the MOE growth factor.

Figure 3

Effect of State Participation Capa on State and County IHSS Wage Costs

|

County A |

County B |

|

|

Current wage and benefit level |

$11.00 |

$12.50 |

|

Wage increase |

+1.00 |

+1.00 |

|

New Wage and Benefit Level |

12.00 (Under Cap) |

13.50 (Over Cap) |

|

Share of Nonfederal Cost for Wage Increase |

||

|

County |

35 percent |

100 percent |

|

State |

65 percent |

— |

|

aAssumed to be $12.10 per hour. |

||

Effect of 10 Percent Option. As mentioned earlier, because wages in County B already exceed the state participation cap, County B would be responsible for 100 percent of the nonfederal costs for the $1.00 wage increase. However, if County B wanted to avoid paying 100 percent of the wage increase, it could apply the 10 percent option to the $1.00 wage increase—resulting in the state having a share of cost in the wage increase. Assuming all eligibility rules were met, the state would pay 65 percent of the nonfederal costs associated with the $1.00 wage increase under the 10 percent option. As a result, County B’s share of nonfederal cost would decrease from 100 percent to 35 percent. Additionally, given that the $1.00 wage increase does not take up the full 10 percent of County B’s current wage and benefit level ($1.25), County B could still implement an additional $0.25 wage increase in which the costs would be shared between the state (65 percent) and the county (35 percent), assuming all other eligibility rules are met.

Effect of Local Wage Supplement. In this example, we assume that County A decides to implement a local wage supplement. Specifically, following the next state minimum wage increase, IHSS provider wages in County A would increase by an additional $1.00 per hour. The wage supplement would continue to increase IHSS provider wages by an additional $1.00 in County A every time the state minimum wage increases. Typically, under the 2017 IHSS MOE, if a county implements multiple wage and benefit increases, its MOE obligation is adjusted to reflect the cost of each of those increases. However, under the local wage supplement model, county costs for every wage and benefit increase or supplement are not added to the IHSS MOE. In this case, County A’s MOE obligation would increase by its share of the cost of the first wage supplement. Given that County A’s wage and benefit level remains below the state participation cap even after applying the $1.00 wage increase, only 35 percent of the nonfederal costs of the first wage increase would be added to County A’s MOE obligation. The costs of subsequent wage supplements, however, would not be added to County A’s MOE obligation. In effect, this means that the state would pay for all the nonfederal costs of all subsequent wage supplements.

Bottom Line: Many Factors Inform County IHSS Wage and Benefit Decisions

Overall, there are a number of factors that determine how counties establish IHSS provider wage and benefit levels. Recent legislation has created various options counties can pursue to increase IHSS provider wages and benefits—all of which have different implications for state and county costs. For example, counties could do nothing locally and allow IHSS provider wages to increase when the state minimum wage increases at no cost to them. Alternatively, counties could implement local wage and benefit increases, ultimately increasing their share of IHSS costs. However, the recent changes to IHSS wage and benefit provisions provide counties with options to increase IHSS wages and benefits while limiting their share of cost. That is, together, these recent changes reduce costs associated with wage increase for counties, especially for counties that locally negotiate wage increase above the state minimum wage.