LAO Contact

December 20, 2018

Analyzing Recent Changes to State Support for Fiscally Distressed Districts

- Introduction

- Historical Oversight and Takeover Process

- Recent Changes

- Assessment

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Summary

In 1991, State Created Formal Process for Supporting School Districts in Fiscal Distress. This system provides escalating tiers of support and intervention to districts based on their fiscal health. All districts are subject to ongoing fiscal oversight from their county office of education (COE). Districts exhibiting signs of fiscal distress receive special COE assistance. Districts facing exceptional fiscal distress and unable to pay their bills can request an emergency state loan in exchange for temporarily ceding control to an outside administrator. Prior to 2018, these administrators were appointed and overseen by the state Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Recent Legislation Changed This Longstanding Process. Trailer legislation adopted as part of the 2018‑19 budget package made three notable changes to the process for supporting districts in exceptional fiscal distress. First, it authorized special grants to supplement the loans already provided to the Inglewood and Oakland Unified school districts. Second, it shifted takeover responsibilities from the state to county level. Third, it established a new process for appointing outside administrators.

Some of the Recent Changes Undermine the Strengths of Longstanding Process. Under the state’s historical district oversight and takeover process, relatively few districts required emergency loans and those that did typically returned to fiscal health and repaid their loans ahead of schedule. By providing special grants to two fiscally distressed districts, the state likely has weakened incentives for all districts to make the tough decisions necessary to balance their budgets. In addition, shifting takeover responsibilities from the state to county level could weaken oversight, as the state is better positioned to provide the independent, external perspective necessary for fiscally distressed districts to recover.

Recommend Returning to Historical Process. We recommend supporting the Inglewood and Oakland Unified school districts within the traditional loan process. If additional support for these districts is deemed necessary, we recommend providing loan payment deferrals in exchange for greater state oversight. In addition, we recommend shifting takeover responsibilities back to the state from the county level.

Introduction

Recent legislation made several changes to the state’s system for intervening in fiscally distressed school districts. These changes could have significant implications for districts moving forward. In this report, we provide background on how the state historically has intervened in fiscally distressed districts, describe and assess the recent changes the state made, and offer associated recommendations.

Historical Oversight and Takeover Process

Below, we discuss the state’s historical process for conducting routine oversight of school district budgets, then discuss emergency state loans and takeovers. This process was adopted in 1991 and continued until altered by trailer legislation in 2018.

Oversight of District Budgets

Prior to 1991, State Had No Formal Process for Overseeing District Budgets. Lacking any formal oversight process, many school districts during this period went years without resolving budget imbalances. Some ultimately faced major fiscal crises. Between 1979 and 1991, a total of 26 districts requested and received emergency state loans. One large district (Richmond Unified) declared bankruptcy. The Richmond bankruptcy spurred legal challenges, and, in Butt v. California, the California Supreme Court ruled the state is obligated to assist districts in fiscal distress.

State Created Oversight Process in 1991. The state’s formal oversight process is named after its initiating legislation—Chapter 1213 of 1991 (AB 1200, Eastin). Under the AB 1200 process, all districts are subject to ongoing fiscal monitoring and districts experiencing fiscal distress are offered escalating tiers of assistance and intervention. Below, we describe these aspects of the process in more detail.

All Districts Receive Ongoing Fiscal Monitoring by County Offices of Education (COEs). Before the start of each fiscal year, all districts are required to submit their projected budgets to their COE for review. COEs are tasked with approving, disapproving, or conditionally approving these budgets. In making their determinations, COEs are to examine several indicators of district fiscal health, such as district reserve levels and salary and benefit costs. Districts with disapproved budgets must revise and resubmit their budgets until they are approved by their COE. (In rare circumstances, districts can appeal to an outside authority to resolve budget disputes with their COE.) During the fiscal year, all districts are required to submit two budget updates to their COE—one in the fall and the other in the spring. For each of these budget updates, COEs assign a positive, qualified, or negative certification. Figure 1 explains each of these terms.

Districts Struggling to Balance Their Budgets Receive Targeted COE Support. Districts with qualified or negative certifications receive additional COE oversight and assistance. In these cases, COEs choose from a menu of possible interventions (see Figure 2). COE interventions are designed to escalate as problems persist or become more severe, such that districts with negative budget certifications may receive both a first‑ and second‑level intervention. Historically, most districts receiving targeted COE support have quickly restored their fiscal health.

Figure 2

County Offices of Education Are Required to Assist Districts in Fiscal Distress

|

First‑Level Intervention for Qualified and Negative Districts |

|

For All Qualified and Negative Districts, COEs Must: |

|

|

In Addition, COEs Must Do at Least One of the Following: |

|

|

Second‑Level Intervention for Negative Districts |

|

COEs Must Do at Least One of the Following: |

|

|

COEs = county offices of education and FCMAT = Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team. |

The Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT) Gives Districts Expert Advice. To assist COEs in supporting districts in fiscal distress, AB 1200 created a team of fiscal experts to conduct in‑depth studies of district budgets and recommend specific steps for improving their fiscal health. The Kern COE manages FCMAT through a state contract.

Emergency State Loans and Takeovers

Districts in Exceptional Distress May Request an Emergency State Loan. In rare cases, districts lack the cash necessary to pay their bills. These districts may request a state loan. Prior to requesting a state loan, a district’s local governing board must invite FCMAT to make a presentation on associated trade‑offs, including the loss of local control that accompanies a state loan (discussed below). The board must then adopt a formal request for state assistance. The Legislature and Governor must then consider whether to approve the loan, with authorization given through a state appropriations bill.

Upon Receiving an Emergency Loan, District Cedes Authority to an Outside Administrator. Historically, the state Superintendent of Public Instruction has appointed and overseen this administrator. The administrator has full control over the district’s budgets and policies. School board members in these districts lose all decision‑making authority and any compensation. (A district receiving a particularly small state loan is exempted from these takeover conditions.)

District Bears Costs of Loan and Oversight. School districts receiving state emergency loans are responsible for paying the associated issuance and interest costs. Districts’ loan payments typically are scheduled over a 20‑year period. These districts also must pay for the salaries of fiscal experts, the outside administrator and trustee, auditors, and other employees who have been hired to provide assistance to the district. The authorized loan amount is intended to provide the district with sufficient funds to pay its regular bills as well as meet these special loan‑related obligations.

Districts Remain Subject to COE Oversight Even After Receiving State Loans. A district managed by an outside administrator still must submit projected budgets and budget updates to its applicable COE for review. Retaining this review step ensures COEs remain aware of all fiscal developments within their districts.

Districts Must Demonstrate Good Management Before Returning to Local Control. After the district receives a state loan, FCMAT sets performance standards for that district in five key areas: (1) financial management, (2) student achievement, (3) personnel management, (4) facilities management, and (5) community relations. Upon meeting the standards in a certain area, the administrator gives associated management control back to the local governing board. After the board regains control in all five areas and the administrator determines the district is likely to comply with its recovery plan, the administrator leaves. This process of regaining local control typically takes several years.

Trustee Remains With District Until Loan Retired. After the administrator leaves, the state Superintendent of Public Instruction appoints a trustee to oversee the district. The trustee serves until the district has repaid its loan in full. During this period, the trustee has the power to overturn local governing board decisions that jeopardize the district’s fiscal health. The power of the trustee, however, is weaker than that of a state administrator, as a trustee cannot make decisions proactively on the district’s behalf.

Recent Changes

Recent Trailer Legislation Makes Three Changes to Emergency Loan and Takeover Process. Chapter 426 of 2018 (AB 1840, Committee on Budget) makes three changes to the process for overseeing districts receiving state loans. One of these changes applies to two specified districts over the next few years, whereas the other two apply to all districts receiving state loans moving forward.

Authorizes Grants (Not Loans) to Cover a Portion of Two Fiscally Distressed Districts’ Operating Deficits. For the Inglewood and Oakland Unified school districts, Chapter 426 authorizes three years of state grants to supplement the state loans the districts previously received. Specifically, the state authorizes grants totaling 75 percent of each district’s operating deficit in 2019‑20, 50 percent of their deficits in 2020‑21, and 25 percent of their deficits in 2021‑22. The districts’ operating deficits will be determined by FCMAT, with the concurrence of the Department of Finance. The operating grants have some associated requirements, but those requirements are no more stringent than those already imposed as a condition of receiving state loans. Specifically, Chapter 426 requires both districts to update their operational and facility plans by March 1, 2019. By March 1 of each year through 2021, FCMAT, with concurrence from the two applicable COEs, is to report to the Legislature and the Department of Finance on progress these districts have made to improve their budget conditions.

Shifts Takeover Responsibilities From State to Counties. Chapter 426 shifts the responsibility for appointing and overseeing the outside administrator from the state Superintendent of Public Instruction to the applicable county superintendent of schools.

Establishes a New Process for Appointing Administrators and Trustees. Under the new Chapter 426 process, FCMAT prepares a list of potential candidates and discloses the list for public input. From this list, the applicable county superintendent of schools makes the appointment, with the concurrence of the state Superintendent of Public Instruction and the president of the State Board of Education. Historically, the state Superintendent of Public Instruction made appointments through an informal and confidential process.

Assessment

Below, we discuss our assessment of the state’s fiscal oversight process and the changes recently made to it. Bottom line, we believe the AB 1200 process generally was effective and caution against most of the recent changes made to it.

Historical Oversight Process Has Worked Well to Date

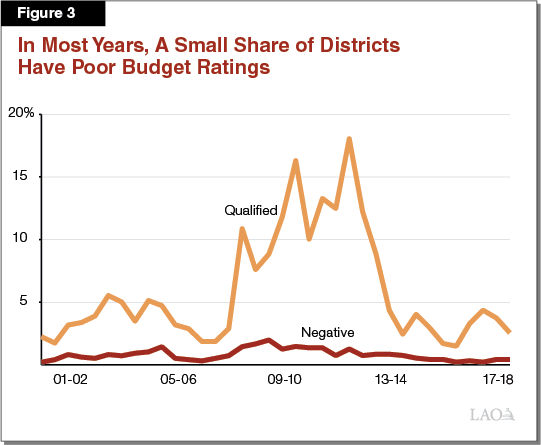

Most Districts Have Found Local Solutions to Fiscal Challenges. As Figure 3 shows, a small share of districts typically receives qualified or negative certifications. The share of districts struggling to balance their budgets, however, tends to increase during economic recessions. From 2008‑09 through 2012‑13, for instance, the share of districts with qualified budget ratings was significantly higher than during stronger economic times and the share of districts with negative ratings was somewhat higher. Despite the ebb and flow of districts with qualified and negative ratings, most districts receiving one of these poorer budget ratings have quickly returned to fiscal health without requesting state loans. This suggests the AB 1200 system has helped districts address budget imbalances and regain their fiscal footing.

Relatively Few Districts Have Received Emergency State Loans. As Figure 4 shows, only nine districts have received emergency state loans since AB 1200 passed in 1991. By contrast, 26 districts received state loans in the 12 years preceding 1991. Of the nine districts that received loans in the AB 1200 era, only three requested loans in the immediate wake of a recession—suggesting most districts requiring loans have systemic issues that go beyond dealing with a tough economic environment. Notably, no district during the past six years has requested a state loan, despite many districts continuing to face declining enrollment and rising pension costs.

Figure 4

Nine Districts Have Received State Loans Since 1991

|

School District |

Year of |

Current |

Total Loan |

Loan |

|

Inglewood Unified |

2012 |

Administrator |

$29 |

2033 |

|

South Monterey County Joint Union High |

2009 |

Trustee |

13 |

2028 |

|

Vallejo City Unified |

2004 |

Trustee |

60 |

2024 |

|

Oakland Unified |

2003 |

Trustee |

100 |

2023 |

|

West Fresno Elementary |

2003 |

— |

1.3 |

2010 |

|

Emery Unified |

2001 |

— |

1.3 |

2011 |

|

Compton Unified |

1993 |

— |

20 |

2001 |

|

Coachella Valley Unified |

1992 |

— |

7.3 |

2001 |

|

West Contra Costa Unified |

1991 |

— |

29 |

2012 |

Districts Have Typically Paid Back State Loans Ahead of Schedule. As Figure 4 shows, the first district to receive an emergency loan under AB 1200 took about 20 years to retire it. The next four districts to receive emergency loans, however, all retired their loans substantially ahead of schedule—after fewer than nine years on average. The four districts to receive state loans more recently still are paying off their loans.

Credit Rating Agencies View California’s Oversight Process as Model. The agencies that provide school districts with credit ratings tend to view the AB 1200 process as a model for state oversight and intervention. Rating agencies cite two features as particularly important to AB 1200’s success: (1) its predictability, as the state and COEs offer escalating levels of support following a uniform monitoring and evaluation process; and (2) its “carrot and stick” approach, under which districts receive state aid only in exchange for agreeing to pay all recovery costs and temporarily ceding local control. These features ensure districts are aware of their fiscal issues and have the incentive to resolve those issues at the local level.

Providing Grants Undermines Historical Oversight Process

FCMAT Believes the Two Districts Could Balance Their Budgets Without State Grants. Although both the Inglewood and Oakland Unified school districts face serious fiscal challenges, FCMAT has identified feasible options for both districts to balance their budgets absent special state grants. These options include adjusting employee benefits, consolidating schools, and downsizing administrative overhead. Though such decisions are difficult, the state has notably eased both districts’ fiscal condition by providing them substantial funding increases under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Under LCFF, per‑student funding has increased by 57 percent at Inglewood and 46 percent at Oakland since 2012‑13. These two districts’ per‑student funding grew more significantly over this period than a large majority of districts statewide.

Providing Grants Sends Wrong Message to Other Districts in Fiscal Distress. If other districts and unions believe the state might offer them special grants too, they are less likely to agree to the difficult decisions necessary to balance their budgets locally and manage their operations responsibly. This could lead more districts to circumvent the traditional oversight process in favor of direct appeals for state assistance.

Providing Grants Undermines Predictability of Oversight Process. The state’s traditional oversight process requires districts to follow a predictable series of steps before seeking state support. By contrast, the state’s recent actions create precedent for aiding districts at unscheduled times and for unspecified reasons. This approach creates more uncertainty for both districts and the state, with both parties less able to predict when intervention will come, the form it will take, and what will be the associated costs. If even a few large districts unexpectedly sought state grants, the cost pressure on the state budget likely would be notable.

Providing Grants Undermines Principles of Core School Funding Formula. Since 2013‑14, California has provided most school funding through LCFF. One principle of LCFF is that all districts should receive equal state funding based on student need. Providing extra state grants to just two districts undermines this equity principle. We estimate the proposed operating grants for 2019‑20 would increase per‑student funding to Inglewood by 4 percent and Oakland by 15 percent as compared to other districts with similar student populations, such as the Compton and Hayward Unified school districts.

New Takeover Process Has Notable Weaknesses

The State, Not COEs, Holds Ultimate Responsibility for Districts With State Loans. Under the Supreme Court’s ruling in Butt v. California, the state is ultimately responsible for assisting school districts in exceptional fiscal distress. Consequently, the state acts as lender of last resort. Upon the Legislature and Governor authorizing a state loan, the state assumes responsibility for ensuring the loan is repaid. Historically, the state has protected this public interest by providing direct oversight of districts while they have outstanding loan amounts. Under the changes in Chapter 426, the state is delegating this key oversight role to COEs, which may not share the state’s interests or feel the same level of obligation to retire the state loan.

State Offers Independent, External Perspective to Districts in Fiscal Distress. Districts seeking state loans typically have deep and persistent budget and management challenges. Some of these challenges reflect powerful constituencies who are unwilling to agree to necessary cutbacks. Counties are more likely than the state to be enmeshed in the political challenges facing their distressed districts. Even counties that have constructive relationships with their fiscally distressed districts may not want to be heavily involved in imposing deep district budget reductions. By contrast, the state is more likely to provide an independent, external perspective.

Shifting Control to Counties Unlikely to Address Recent Concerns About State Administrators. In proposing the changes to the takeover process, the Brown administration indicated it was concerned with the frequent turnover of state administrators assigned to the Inglewood Unified School District. We have spoken with many stakeholders involved in this state takeover and believe the circumstances in that district are anomalous. Although the state has experienced some challenges attracting and retaining effective administrators, these challenges are unlikely to be overcome by shifting administrator responsibilities to COEs. Takeover administrators face a uniquely challenging job, as they are solely responsible for making the tough decisions necessary to recover districts from serious fiscal distress. Relatively few individuals in the state are both willing and qualified to accept such a challenge, and COEs seem no more likely than the state to identify and attract these individuals.

New Appointment Process Raises Issues for Consideration

Requiring Additional Disclosure Likely to Dissuade Qualified Administrator Candidates From Applying. Requiring FCMAT to seek public input on a list of administrator candidates will likely dissuade sitting district superintendents and other qualified persons from applying for these positions. Few candidates for any job wish to disclose their interest to current employers before receiving a new job offer. In conversations with successful former state administrators, most told us they would not have applied had they been required to publicly signal their interest prior to receiving a job offer.

Requiring Concurrence on Administrator Selection Could Improve Decision Making . . . Allowing one elected official to select an administrator unilaterally—as was historically the case—might result in decisions made for narrow political or personal reasons. For example, a superintendent connected to a fiscally distressed district might be reluctant to appoint an administrator willing to impose the deep cuts necessary to balance that district’s budget. These political risks can be mitigated by requiring other figures, such as other elected officials representing competing political constituencies or nonelected officials, to concur on administrator appointments.

. . . But Also Could Result in Delays and Weaken Accountability. Building concurrence among parties with competing views often requires time. Consequently, the new process may result in delays during which the state’s most challenged districts are left without a leader. In addition, requiring concurrence among multiple parties means no single party can be held fully accountable for the appointment decision. Moving forward, the Legislature could have difficulty identifying and correcting the causes of poor appointment decisions.

Recommendations

To Extent Deemed Necessary, Support the Inglewood and Oakland Unified School Districts With Loan Modifications. We recommend the Legislature rescind authorization for special operating grants to the Inglewood and Oakland Unified school districts over the 2019‑20 through 2021‑22 period. If the Legislature wishes to provide additional time for these districts to make necessary budget adjustments, we recommend considering loan payment deferrals rather than grants, as this would preserve the historical expectation that districts are responsible for paying fiscal recovery costs. We recommend consulting with FCMAT to determine whether the existing repayment schedules for these districts are realistic before providing any loan deferrals.

Attach Meaningful Conditions to Any New State Support. The state’s historical oversight process has worked in part because it requires districts to weigh the benefit of state loans against the cost of temporarily ceding local control. We recommend preserving this trade‑off as a condition of making loan modifications. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature consider exercising greater state oversight as a condition of providing any loan payment deferrals to the Oakland Unified School District. (Unlike the Inglewood Unified School District, which is still managed by an outside administrator, the Oakland Unified School District has been back under local control since 2008.) To help determine what control to take back, the Legislature could ask FCMAT to conduct a review of the district in the five core management areas. If FCMAT were to find that the district was no longer meeting performance expectations in one or more of those areas, the state could appoint an administrator to assume associated governing control.

Shift Takeover Responsibilities Back to the State. We recommend the Legislature return to the historical practice of having the state oversee districts with emergency state loans. The state is likely better equipped than most counties to provide effective oversight by offering an independent, external perspective. The state also is the entity that holds ultimate responsibility for the district both retiring its loan and reinstituting good management practices. Although we recognize the Legislature may wish to ensure some local control over fiscally distressed districts, we note COEs have historically continued to serve a role in reviewing district budgets even after those districts fall under state control.

Remove Disclosure Requirement for Administrator Candidates. Regardless of whether the Legislature chooses to have the state or county superintendent of schools appoint administrators and trustees, we recommend removing the requirement that FCMAT seek public input on administrator candidates. Relatively few individuals have both the experience and interest to serve as effective administrators and requiring all candidates to publicly disclose that interest will likely discourage most potential candidates from applying.

Conclusion

For schools to keep their doors open, school districts must maintain good fiscal health. Local school boards are the ones tasked with keeping their districts in good fiscal health. These boards are to balance their district budgets each year, even when—especially when—doing so requires difficult trade‑offs and decisions. The state’s historical process for overseeing district budgets—giving local boards early warning signs of fiscal problems and having COEs help local boards make fiscal corrections—has worked to date to keep the vast majority of districts on positive fiscal footing. We encourage the Legislature to maintain this system and work within it to help struggling districts. We are concerned that recent changes could weaken the system and result in poorer local fiscal management.