LAO Contact

February 7, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

The Governor's Individual Health

Insurance Market Affordability Proposals

Executive Summary

Broad Concerns Have Been Raised About Health Care Costs and Access . . . The Legislature, among others, has raised concerns about underlying costs, efficiency, and access in the state’s overall health care system.

. . . As Well as Specific Concerns About Affordability of Individual Market Coverage. In addition to broader concerns about the health care system, the Legislature has raised more specific concerns about affordability in the individual health insurance market. At the Legislature’s direction, Covered California recently released a report that outlines a series of policy options to improve affordability and increase enrollment in the individual market.

Governor Proposes Two Policies to Make Individual Market Coverage More Affordable. The Governor’s proposed budget includes elements intended to help address the above concerns. The subset of the Governor’s proposals we review in this report focus more narrowly on encouraging enrollment and reducing consumer costs in the individual market, as opposed to broader questions of underlying health care system cost and efficiency. Specifically, the Governor proposes two policies: (1) the creation of a state individual mandate with an associated financial penalty, to take the place of the federal individual mandate penalty that was effectively eliminated by Congress beginning in 2019, and (2) the use of revenues from the state individual mandate penalty to provide state subsidies to reduce the cost of individual market coverage.

Individual Mandate Proposal Merits Serious Consideration. While the full extent of its impact is subject to some uncertainty, the individual mandate may be one of the state’s most effective policy options to increase enrollment in the individual market and reduce the cost of individual market coverage, particularly for households that currently do not receive federal subsidies. The individual mandate does involve trade‑offs. In particular, the individual mandate would generate revenue at the expense of individuals who would choose to pay the penalty rather than obtain coverage, perhaps because they do not view available coverage options as affordable. However, on balance, we think the Governor’s proposal to create a state individual mandate warrants serious consideration. We think it makes sense for the Legislature to consider—as the Governor has proposed—the proposed state individual mandate in conjunction with other policies that would improve the affordability of health insurance coverage. This could serve to increase the level of compliance with the mandate, meaning that more people would have health coverage than otherwise.

Legislature Has Multiple Policy Options to Increase Individual Market Coverage and Improve Affordability. We recommend that the Legislature consider the Governor’s proposal in the context of a range of policy options, such as those presented in Covered California’s report, and consider what policies would best align with the Legislature’s policy and budgetary priorities.

Many Implementation Questions Remain. If the Legislature wishes to create a state individual mandate along with some form of insurance subsidies, as proposed by the Governor, many questions remain to be addressed. In particular, funding subsidies from individual mandate penalty revenues as proposed by the Governor could be problematic. The goal of the individual mandate as a deterrent against forgoing insurance coverage is at odds with the goal of raising revenue for insurance subsidies. To address this issue, the Legislature could consider using whatever penalty revenues are generated to simply offset—at least partially—the cost of subsidies, with other state funds covering any difference.

Introduction

Broad Concerns Have Been Raised About Health Care Costs and Access. The Legislature, among others, has raised concerns about the underlying cost and efficiency of the state’s overall health care system, and the extent to which the state’s residents can access quality health care services through that system. The significant number of California residents without health insurance coverage—roughly estimated to be 3.5 million people—has been a particular concern. The state’s health care system is complex—numerous factors influence who can access care, how that care is delivered, and at what cost.

Proposals Reviewed in This Report Focus Narrowly on Encouraging Enrollment and Reducing Consumer Costs in the Individual Health Insurance Market. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget proposal includes elements intended to help address some of these concerns. The subset of the Governor’s proposals we review in this report focus more narrowly on encouraging enrollment in health insurance coverage purchased on the individual market—where over 2 million people obtain their coverage—and on making that coverage more affordable. (The individual market excludes coverage obtained through employer‑sponsored insurance and government programs such as Medi‑Cal.) These proposals do not directly address, nor are they intended to address, broader concerns about the underlying cost of health care services or the efficiency of health care delivery systems.

Legislature Has Taken Recent Actions Related to Broader Concerns About Underlying Costs. As part of the 2018‑19 budget package, the Legislature set in motion two ongoing, multiyear efforts that are intended to explore issues related to broader concerns about underlying costs in the state’s health care system. Specifically, the Legislature provided funding to begin planning and developing a database that would collect information on public and private health care costs and utilization in the state. The database is intended to be used to increase transparency of health care pricing and inform state policy decisions. The Legislature also established a Council on Health Care Delivery Systems that will develop options for structural reforms to the state’s health care delivery system to accomplish universal health care coverage and reduced health care costs.

Background

Overview of Health Insurance Coverage in California

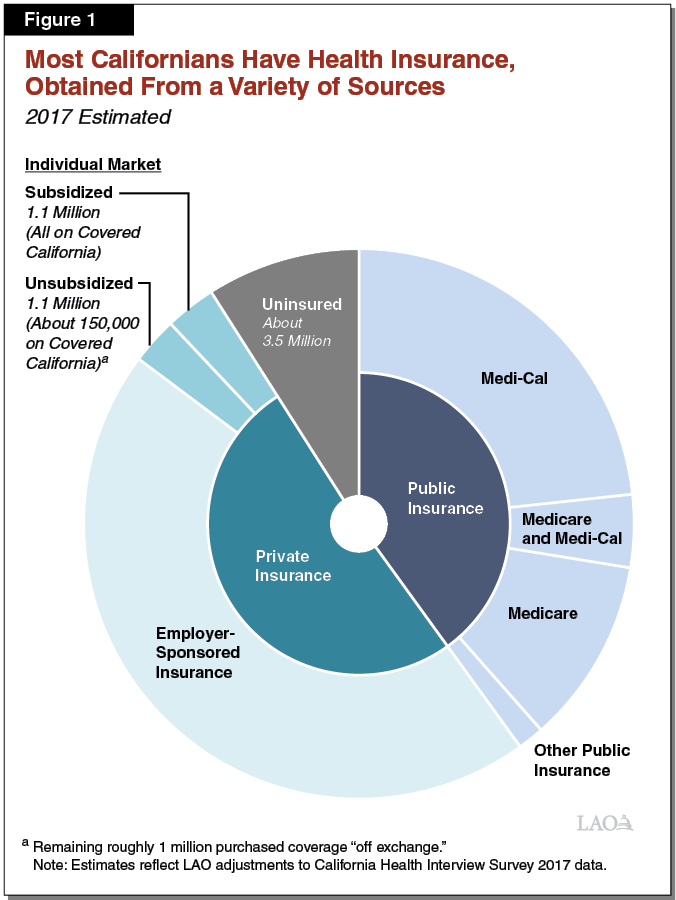

Most Californians Have Health Insurance Coverage. As shown in Figure 1, we estimate that most Californians—91 percent—have health insurance coverage. (Compared with other states, California’s rate of insurance is roughly in the middle—some states have higher rates of insurance, while others have lower rates of insurance.) Employer‑sponsored insurance is the most common source of coverage. Major public health insurance programs, including Medi‑Cal, the state’s insurance program for low‑income people, and Medicare, the federal program that primarily provides health coverage to the elderly, also cover large portions of the state’s residents. Over Two Million Californians Purchase Coverage Through Individual Market. Individuals who are not enrolled in insurance through their employer or public health insurance programs can purchase coverage directly from insurers in what is referred to as the “individual market.” As shown in Figure 1, about 2.2 million individuals had health insurance coverage through the individual market in 2017. As will be described in more detail later, a little less than 1.1 million of these received federal subsidies to reduce the cost of coverage through the state’s health benefits exchange, known as Covered California. About 150,000 additional individuals who do not receive subsidies also purchased coverage through Covered California, for total enrollment through Covered California of a little over 1.2 million at the end of 2017. About 1 million additional people purchased insurance from insurers outside of Covered California—sometimes referred to as “off exchange.” Federal subsidies are not available off exchange.

Roughly 3.5 Million Californians Are Uninsured. While most Californians have health insurance coverage, an estimated roughly 3.5 million people in the state are uninsured. In general, the uninsured are more likely than the general population to be low income. A large portion of the uninsured—likely around 1.5 million—are undocumented adults. We note undocumented adults may not purchase coverage through Covered California and are ineligible for Medicare and the full scope of Medi‑Cal benefits. Some undocumented adults may enroll in “restricted‑scope” Medi‑Cal coverage, which provides coverage for emergency and some pregnancy‑related services. However, due to the limited nature of restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal, we consider these individuals uninsured. Although the number is uncertain, a portion of the uninsured are eligible for subsidized coverage through Covered California, as will be described in more detail later.

Federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Significantly Altered Health Insurance Landscape

The ACA—most of the provisions of which became effective in 2014—brought about significant changes to the way that health insurance coverage is provided in California. Broadly speaking, the ACA led to more comprehensive and standardized health insurance options on the individual market, limited the ability of health insurers to charge higher premiums or deny coverage to individuals with costly preexisting medical conditions, and provided both incentives and penalties to encourage individuals to enroll in health insurance coverage. Below, we describe several key aspects of the ACA in greater detail.

Covered California Established as Centralized Marketplace for Comparing and Purchasing Coverage. The ACA provided for the establishment of state health benefits exchanges, including Covered California, where people in the individual market can compare health insurance coverage options. Consumers who shop for coverage on Covered California can choose among health insurance plans organized into standardized metal tiers, including bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. These tiers vary in the amount of monthly premiums they charge and out‑of‑pocket costs they require households to pay, such as annual deductibles and co‑pays for medical visits. Bronze plans have the lowest premiums but have the highest out‑of‑pocket costs. For example, bronze plans feature a large deductible that must be met before many medical services are covered. Silver, gold, and platinum plans require progressively lower out‑of‑pocket costs, but also come with higher premiums.

Federal “Individual Mandate” to Require Most to Obtain Health Insurance Coverage or Pay Penalty. As originally enacted, the ACA imposed a requirement, referred to as the individual mandate, that most individuals obtain specified minimum health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. (As will be discussed later, subsequent federal action eliminated the penalty beginning in 2019.) The individual mandate was intended to discourage people from going without health insurance coverage, particularly younger and healthier individuals who have lower risk of incurring health care costs and who otherwise would be less likely to enroll in coverage. Increased coverage of younger, healthier populations leads to a more balanced insurance risk pool and allows the costs of covering higher‑risk populations to be spread more broadly. This in turn reduces the average cost of coverage and helps to offset the increased cost of making individual market coverage more comprehensive under the ACA.

As outlined in the ACA, the individual mandate required households to certify on their annual federal income tax return that they have health insurance coverage that meets minimum requirements. For those who do not have minimum coverage, the individual mandate penalty in 2018, for example, was set at the greater of a flat amount ($2,085 for family of four) or 2.5 percent of family income, up to a maximum (just over $13,000 for a family of four). Households subject to the individual mandate penalty for that year calculate the amount of the penalty and pay the amount owed through their federal income tax return. Most households that have paid the penalty have paid the flat amount.

For those who do not have minimum coverage, the ACA provided several exemptions from the individual mandate penalty. For example, a household is exempt from the individual mandate penalty if (1) it does not have any “affordable” health insurance options (for purposes of the individual mandate, coverage is considered affordable if it costs less than 8.05 percent of the household’s annual income), (2) it has income below the minimum threshold required to file a federal income tax return, or (3) its members are undocumented. In 2016, the most recent year for which data are available, almost 600,000 tax filers in California paid a total of $446 million in individual mandate penalties to the federal government.

Federal Subsidies to Reduce Cost of Health Insurance Purchased Through Covered California. The ACA also created two types of subsidies that work together to reduce the cost of health insurance for most households that purchase coverage through Covered California, as described below:

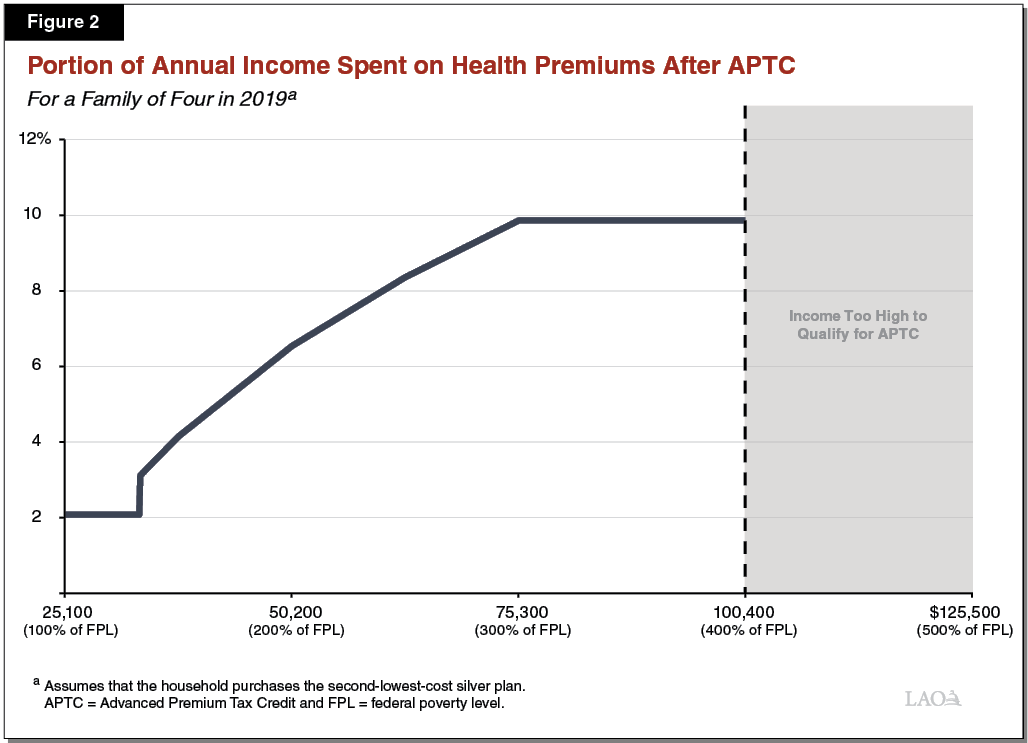

- Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC). The APTC offsets the cost of health insurance premiums for households with incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). As shown in Figure 2, the APTC effectively limits a household’s net premium for a silver plan (after accounting for the APTC) to between 2 percent and 10 percent of annual income. (This percentage increases as income increases.) Each year, Covered California estimates the amount of APTC a household will qualify for before coverage begins and the household can choose to “advance” some or all of the estimated APTC amount to insurers. This immediately reduces the household’s monthly premiums. At the end of the year, any remaining APTC is claimed on the household’s federal income tax return. In the event that a household was ultimately eligible for less APTC than was advanced to insurers through the preceding year, the household is required to pay the difference through the income tax return.

- Cost Sharing Reductions (CSRs). While the APTC offsets premium costs, CSRs reduce households’ out‑of‑pocket costs. Under the ACA, the federal government provided CSR funding for insurers on Covered California to offer three different “enhanced” plan options that have the same premiums as a silver plan but require lower out‑of‑pocket costs for covered households. Households with incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of FPL may enroll in these enhanced silver plans. Figure 3 shows examples of out‑of‑pocket costs for a regular silver plan and the three enhanced silver plan options in 2019.

Figure 3

Enhanced Silver Plans Reduce Out‑of‑Pocket Costs

Cost Sharing for Selected Services, 2019

|

Silver |

Enhanced Silver Plans |

|||

|

Silver 73 |

Silver 87 |

Silver 94 |

||

|

Household income to enroll |

No income limitations |

201 percent to 250 percent of FPL |

151 percent to 200 percent of FPL |

100 percent to 150 percent of FPL |

|

Portion of average annual medical costs covered by plan |

70% |

73% |

87% |

94% |

|

Annual out‑of‑pocket maximum |

$7,550 for an individual $15,100 for a family |

$6,300 for an individual $12,600 for a family |

$2,600 for an individual $5,200 for a family |

$1,000 for an individual $2,000 for a family |

|

Selected Co‑Pays |

||||

|

Primary care visit |

$40 |

$35 |

$15 |

$5 |

|

Specialist visit |

80 |

75 |

25 |

8 |

|

Emergency room visit |

350 |

350 |

100 |

50 |

|

FPL = federal poverty level. |

||||

Concerns Raised About Cost of Individual Market Coverage

Despite ACA policies intended to reduce the average cost of individual market coverage, concerns have been raised that individual market coverage may not be affordable for some households, including those that are currently eligible for federal subsidies and those with higher incomes that are not.

Concerns Among Those Eligible for Federal Subsidies . . . Although federal subsidies limit the cost of coverage for those who are eligible, there are indications that some households that are eligible for federal subsidies still view individual market coverage as unaffordable. According to Covered California, almost 30 percent of households that are eligible for federal subsidies do not take up coverage, making them subject to the individual mandate penalty (unless they are exempt). Among this group (and among the uninsured of all incomes), the cost of coverage is the most commonly cited reason for lacking health insurance coverage.

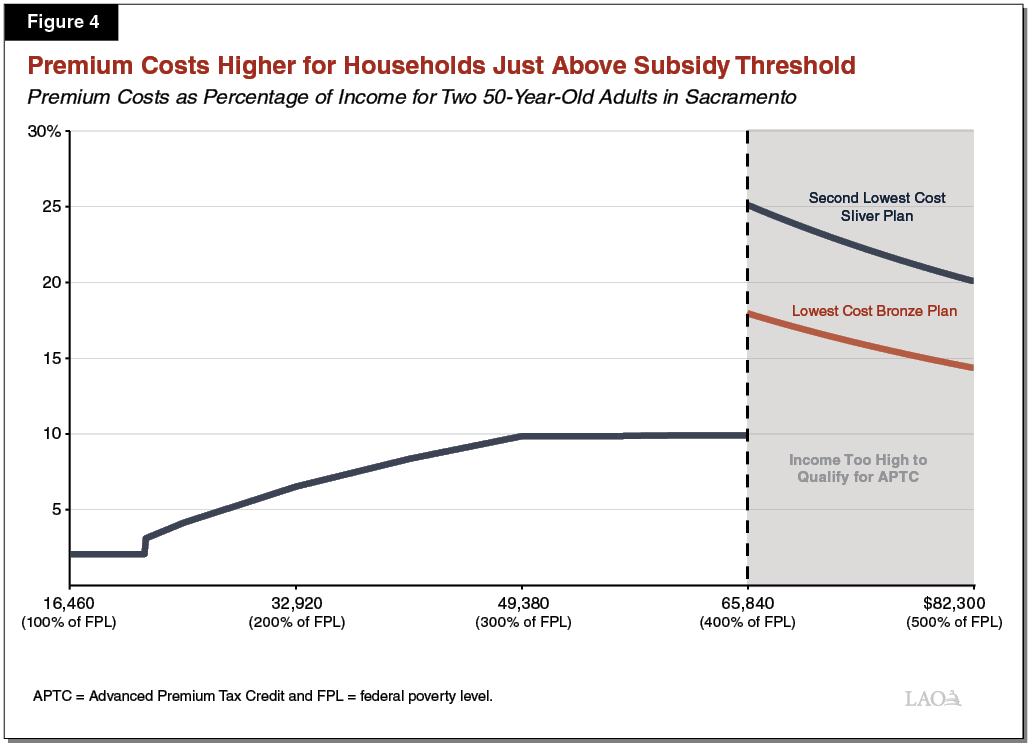

. . . And Those Above Threshold to Qualify for Federal Subsidies, Who Face Subsidy “Cliff.” While the APTC limits premium costs to no more than about 10 percent of income for eligible households, federal subsidies end abruptly for households with income just above the threshold to qualify for APTC. The abrupt end of subsidies is sometimes referred to as the subsidy cliff. Households at this income level can pay substantially more than 10 percent of their income for coverage. (This percentage declines the further above APTC income threshold a household is.) Figure 4 displays premiums as a percentage of income for a hypothetical household consisting of two adults, each age 50, living in Sacramento. If the household had annual income of $65,000, their premiums for a silver plan purchased through Covered California would be limited to about 10 percent—close to $6,500 for the year—because of the APTC. If the household’s income increased to $66,000 per year, they would no longer qualify for APTC and their premium costs to keep the same plan would increase to 25 percent of their income—over $16,000 for the year. If the household instead switched to the least expensive bronze plan available, their premiums would be 18 percent of their income—almost $12,000 for the year—and the household would have increased out‑of‑pocket costs. Households just above the APTC eligibility threshold that have older individuals or that are located in areas of the state with higher premiums are particularly likely to spend a higher percentage of their income on premiums.

Because net premium contributions are limited to a fixed percentage of income for households that receive the APTC, these households are insulated from changes in gross premiums (premiums before accounting for the APTC). If gross premiums increase from year to year, the household’s APTC increases so that the net premium cost as a percentage of income remains roughly the same. However, households that do not qualify for federal subsidies are exposed to annual increases in premiums. Year‑over‑year increases in premiums in the individual market have been significant. Covered California reports that average premiums for unsubsidized enrollees with coverage through Covered California grew by over 10 percent in each of 2017 and 2018.

Federal Individual Mandate Penalty Effectively Eliminated Beginning in 2019. As part of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, Congress set the penalty for violating the individual mandate’s coverage requirement to zero beginning in 2019. The requirement that most individuals have coverage technically remains in effect, but without the penalty this requirement is unenforceable. (Because of the timing of tax filing, households that did not have coverage during 2018 and are subject to the individual mandate penalty are paying penalty obligations during the current tax filing season in early 2019.)

End of Individual Mandate Penalty Expected to Lead to Greater Number of Uninsured. By removing the financial disincentive for not having coverage, ending the individual mandate penalty is expected to lead to fewer individuals taking up coverage and a larger number of uninsured. The federal individual mandate was implemented at the same time as several other policies that affected the number of people enrolling in insurance. This makes it challenging to separate the effects of the individual mandate from the effects of these other policies. Additionally, states implemented ACA policies differently, so the effect of the individual mandate, when enforceable, on enrollment may have been different in each state. For these reasons, the number of people who will discontinue coverage because of the end of the federal individual mandate penalty is uncertain. Several research organizations have estimated the potential impact of ending the federal individual mandate penalty on individual market enrollment at the state and national levels using varying sets of assumptions and methods. These estimates project reductions in individual market enrollment ranging from around 7 percent to around 26 percent.

Recently, University of California researchers used the California Simulation of Insurance Markets (CalSIM) model to project that enrollment in California’s individual market would be 10 percent lower in 2020 and over 14 percent lower in 2023 than it would have been if the federal individual mandate penalty had continued. This equates to about 260,000 fewer individual market enrollees in 2020 and about 370,000 fewer enrollees in 2023. The CalSIM researchers also projected the impact that ending federal individual mandate penalty would have on enrollment in other forms of coverage, as shown in Figure 5. In particular, CalSIM researchers projected that enrollment in Medi‑Cal will drop by a few hundred thousand people. (Under the ACA, Medi‑Cal enrollment grew significantly due to an expansion in eligibility and as previously eligible individuals newly enrolled in coverage, the latter sometimes referred to as the “woodwork effect.” Growth in Medi‑Cal enrollment was driven in part by the individual mandate. Accordingly, the end of the federal individual mandate penalty will have the opposite effect as people have reduced incentive to seek or renew Medi‑Cal coverage.) After accounting for changes across these forms of coverage, CalSIM researchers projected that 300,000 additional people will be uninsured in 2020 and 660,000 additional people would be uninsured by 2023 as a result of the end of the federal individual mandate penalty.

Figure 5

Projected Enrollment Change Due to End of Federal Individual Mandate Penalty

Calendar Years 2020 and 2023

|

2020 |

2023 |

|

|

Individual market |

‑260,000 |

‑370,000 |

|

Medi‑Cal |

‑170,000 |

‑350,000 |

|

Employer‑sponsored insurancea |

130,000 |

60,000 |

|

Net Decrease in Enrollment |

‑300,000 |

‑660,000 |

|

aEmployer‑sponsored insurance is projected to increase as more employers offer coverage to employees in response to higher premiums in the individual market because of the end of the federal individual mandate penalty. Source: UC Berkeley/UCLA California Simulation of Insurance Markets projections, November 2018. |

||

Since 2019 is the first year in which the federal individual mandate will not be enforced, the end of the penalty could affect enrollment in coverage purchased on Covered California beginning in 2019. Covered California recently announced that new enrollment was down 24 percent in 2019 relative to the prior year (although a higher number of previous enrollees renewed their coverage, leading to roughly flat levels of plan selections in 2019 overall relative to 2018). Several factors likely contributed to these changes, but the end of the federal individual mandate penalty may have played a role.

End of Individual Mandate Penalty Expected to Lead to Increased Cost of Individual Market Coverage. Those who choose not to enroll in coverage because of the end of the federal individual mandate penalty are expected to be lower‑risk (less costly to insure) than those who remain covered. This is expected to increase average premiums on the individual market. CalSIM researchers estimate that the end of the individual mandate penalty will lead to an increase in premiums of between 8 percent and 10 percent. Households that qualify for APTC are insulated from these premium changes, but the changes would directly affect households in the individual market that do not qualify for federal subsidies.

Coverage Affordability and Enrollment Are Linked. The cost of individual market coverage and the extent to which individuals choose to take up coverage are linked in two ways. First, a greater number of individuals will choose to purchase coverage at lower costs than at higher costs. At the same time, as a greater number of younger and healthier individuals purchase coverage, the risk mix of the insurance pool improves and premiums decrease relative to what they otherwise would have been. In this way, policies intended to reduce the cost of coverage, such as the APTC and CSRs, can have the added effect of increasing enrollment, potentially leading to additional reductions in premiums. Similarly, policies intended to increase take‑up of coverage, such as the individual mandate, can have the added effect of reducing premiums.

Legislature Required Report on Options to Improve Individual Market Affordability

In light of concerns about affordability in the individual market, the Legislature directed Covered California to develop options for providing financial assistance to help low‑ and middle‑income Californians access health insurance coverage. Covered California submitted a report to the Legislature pursuant to this requirement on February 1, 2019.

Report Lays Out Several Policy Options for Legislature’s Consideration. The Covered California report lays out several options for improving affordability and increasing enrollment in the individual market. Specifically, the report identifies three “market‑wide” options that would generally have a larger impact in the individual market overall but also require a larger commitment of state funds, as well as eight “targeted” options that would generally have less impact but would require a smaller commitment of state funds. Some options include a single affordability policy, while other reflect a package of policies. The policies included in the options fall into three main categories:

- State Insurance Subsidies. Several of the options presented in the Covered California report would provide state subsidies to further reduce the cost of insurance in the individual market. These subsidies include additional premium assistance, similar in concept to the APTC. Some options include supplemental premium assistance for households with incomes below 400 percent of FPL that currently qualify for the APTC. Other options include premium assistance for households with incomes above 400 percent of FPL that currently do not receive federal assistance. Insurance subsidies described in the Covered California report also include additional state‑funded CSRs that would further reduce out‑of‑pocket costs for some households.

- State Individual Mandate With Penalty. The Covered California report includes options that would create a state individual mandate and an associated penalty, modeled on the federal individual mandate before its penalty was set to zero. The individual mandate differs significantly from other affordability proposals in that it generates revenue for the state.

- State Reinsurance Program. Finally, the Covered California report includes options that would establish a state “reinsurance” program. In a reinsurance program, the state would cover part of the cost of particularly high‑cost claims on behalf of insurers in the individual market. This would reduce the risk for insurers of having to pay high‑cost claims. This, in turn, would allow insurers to charge lower premiums for individual market coverage. The Covered California report describes how the state could receive federal funding to offset some of the costs of a reinsurance program through a federal Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver. More information on Section 1332 waivers is provided in the nearby box.

Federal Section 1332 State Innovation Waivers and Reinsurance

Section 1332 State Innovation Waivers Can Provide Additional Federal “Pass‑Through” Funding. Section 1332 of the Federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) allows states to apply for a waiver of certain ACA requirements in order to implement policies that improve the quality and affordability of health insurance coverage. Policies implemented under a Section 1332 waiver are required to not increase overall federal spending. However, if a policy implemented under a Section 1332 waiver reduces federal spending (such as spending on the Advanced Premium Tax Credit, or APTC), the federal government will pass these savings through to the state. Such funding is referred to as pass‑through funding.

Several States Receive Pass‑Through Funding for Reinsurance Programs. State reinsurance programs reduce average premiums for health insurance coverage purchased in the individual market. Since the amount of APTC a household receives is tied to the level of premiums on the exchange, reinsurance programs generally reduce federal APTC spending. Several states, including Alaska, Minnesota, Oregon, Maryland, Wisconsin, Maine, and New Jersey, have received approval of Section 1332 waiver that included reinsurance programs and federal pass‑through funding to offset the costs of these programs. The ratio of federal pass‑through funding to the cost of the reinsurance program varies by state and depends on the risk profile of the state’s individual market.

Amount of Potential Federal Pass‑Through Funding Subject to Some Uncertainty. The Covered California report estimates that California could potentially receive federal pass‑through funding equal to about 66 percent of the total cost of the program. However, the amount of federal pass‑through funding is uncertain, in part because it could depend on whether a state reinsurance program is packaged with other state affordability policies for purposes of a Section 1332 waiver. Many other policies, including state insurance subsidies and a state individual mandate, are projected to increase individual market enrollment and therefore increase federal APTC spending. If the state were to adopt a package of policies that included policies that both increased and decreased federal APTC spending, the federal government might require that all of these policies be considered together when determining the amount of federal pass‑through funding. This would result in less federal pass‑through funding than if a reinsurance program was considered on its own.

Options Vary in Estimated State Fiscal Impact and Effect on Enrollment. Figure 6 provides a high‑level summary of the parameters of each option in the Covered California report, along with their estimated impact on enrollment in the individual market and their estimated state fiscal impact. While most options have a state cost (sometimes net of offsetting revenues or federal funding), one option—Targeted Option 8, which would implement a state individual mandate without any other policies—generates revenues. Generally, options that result in greater enrollment impacts have greater associated net state costs, but this is not always the case. The impact on enrollment per dollar of net state cost varies significantly across the options. Similar to estimates of the potential impact of ending the federal individual mandate penalty, these estimates are based on a series of assumptions and are subject to uncertainty. Overall, however, we find the estimates reasonable.

Figure 6

Summary of Options Presented in Covered California Report

|

Estimated New Individual Market Enrollment |

Estimated State Fiscal Impacta |

|

|

Options With Greater State Cost |

||

|

Market‑Wide Option 1 |

||

|

Provide supplemental premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions for households under 400 percent of federal poverty level (FPL). |

290,000 |

$2.2 billion cost |

|

Provide premium subsidies for households over 400 percent of FPL. |

||

|

Market‑Wide Option 2 |

||

|

In addition to policies included in Market‑Wide Option 1, enact state individual mandate with penalty, modeled on federal individual mandate. |

648,000 |

$2.1 billion net costb |

|

Market‑Wide Option 3 |

||

|

In addition to policies included in Market‑Wide Option 1 and Market‑Wide Option 2, establish state‑based reinsurance program. |

764,000 |

$2.7 billion net costb,c |

|

Options With More Limited State Cost |

||

|

Targeted Option 1 |

||

|

Provide more limited (relative to market‑wide options) supplemental premium subsidies for households under 400 percent of FPL. |

70,000 |

$425 million cost |

|

Targeted Option 2 |

||

|

Provide more limited supplemental cost sharing reductions for households under 400 percent of FPL. |

27,000 |

$215 million cost |

|

Targeted Option 3 |

|

|

|

In addition to policies included in Targeted Option 1, provide more limited additional premium subsidies for households with incomes between 400 percent and 600 percent of FPL. |

125,000 |

$765 million cost |

|

Targeted Option 4 |

||

|

In addition to policies included in Targeted Option 3, enact state individual mandate with penalty, modeled on federal individual mandate. |

478,000 |

$409 million net costb |

|

Targeted Option 5 |

||

|

Provide more limited premium subsidies for households with incomes between 400 percent and 600 percent of FPL only. |

47,000 |

$285 million cost |

|

Targeted Option 6 |

||

|

Provide slightly more generous subsidies relative to Targeted Option 5 for households with incomes above 400 percent of FPL. |

50,000 |

$324 million cost |

|

Targeted Option 7 |

|

|

|

Establish state‑based reinsurance program. |

118,000 |

$578 million net cost |

|

Targeted Option 8 |

||

|

Enact state individual mandate with penalty, modeled on federal individual mandate. |

359,000 |

$526 million revenueb |

|

aWhere a net cost is shown, reflects net effect of new state spending and offsetting revenues from individual mandate penalties or federal pass‑through for reinsurance. bDoes not reflect state costs in Medi‑cal—potentially in the hundreds of millions of dollars—from increased enrollment under a state individual mandate. cAssumes offsetting federal pass‑through revenues, which are uncertain. Net costs could be higher by about $800 million. Source: Covered California “Options to Improve Affordability in California’s Individual Health Insurance Market.” |

||

Overview of the Governor’s Proposal

As part of the 2019‑20 Governor’s Budget, the Governor proposes two policies along the lines of the options presented in the Covered California report. First, the Governor proposes to create a state individual mandate with a penalty. Second, the Governor proposes to use revenues generated by the state individual mandate penalty to increase insurance subsidies for households purchasing coverage on Covered California. The stated objectives of these proposals include improving the affordability of health care and increasing the number of people with health insurance coverage. The administration has so far provided only a broad outline of these proposals, with few details on structure and implementation. Below, we describe the broad contours of the Governor’s proposal based on information provided by the administration as of the time this analysis was prepared.

Create State Individual Mandate With Penalty

State Mandate Would Be Modeled on Federal Mandate, Before Penalty Elimination. Similar to an option presented in Covered California’s report, the Governor proposes to model a state individual mandate on the federal individual mandate, before the federal penalty was set to zero. Based on the amount of federal penalties paid by Californians in 2016, the administration estimates that the proposed state individual mandate would generate roughly $500 million annually in new revenues.

Franchise Tax Board (FTB) Would Administer State Mandate. The administration has indicated that FTB, which administers the state’s personal income tax, would implement the proposed state individual mandate penalty. This would be similar to the federal individual mandate penalty that is administered by the federal Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Provide State Insurance Subsidies

Additional Subsidies for Households Currently Eligible for Federal Assistance. The administration has indicated that proposed state subsidies would be available to households with incomes between 250 percent and 400 percent of FPL, households that are generally eligible for federal subsidies. It is unclear whether these subsidies would be structured similar to the APTC, CSRs, or some other form of assistance.

New Subsidies for Relatively Higher‑Income Households Currently Not Eligible for Federal Assistance. The administration has indicated that proposed state subsidies would also be available to households with incomes between 400 percent and 600 percent of FPL, households that are not currently eligible for federal subsidies. The structure of these proposed subsidies is similarly unclear.

Covered California Would Administer State Subsidies. The Governor’s proposal assumes that Covered California would administer the proposed subsidies. Details on implementation are yet to be determined.

LAO Assessment

Governor’s Proposal Would Likely Reduce Number of Uninsured and Improve Individual Market Affordability

On Its Own, State Individual Mandate With a Penalty Would Likely Increase Take‑Up and Reduce Premiums. As noted previously, the full extent of the negative impact on insured levels and premium costs of the end of the federal individual mandate is uncertain. Accordingly, the full extent of the impact of enacting a state individual mandate with penalty is similarly uncertain. However, by avoiding or mitigating reductions in coverage and premium increases associated with the end of the federal individual mandate penalty, a state individual mandate could potentially be one of the state’s most effective policy options to increase coverage and reduce premiums. As shown previously in Figure 6, Covered California projects that implementing a state individual mandate on its own would result in 359,000 additional individuals with coverage, 235,000 of whom would be potentially eligible for federal subsidies. Covered California further estimates that the state individual mandate would also reduce premiums for currently unsubsidized households off exchange by a projected $24 per month. These are a large effects in comparison with most individual policy options in the Covered California report.

State Individual Mandate Penalty Generates State Revenues . . . Unlike some other policy options that directly subsidize household insurance costs, the state individual mandate could increase enrollment and reduce premiums without significant state spending (other than some relatively limited costs for administration) and in fact would generate state revenues.

. . . But Could Indirectly Result in Increased State Costs in Medi‑Cal. As noted previously and shown in Figure 5, some of those projected to discontinue coverage because of the end of the federal individual mandate penalty would have otherwise been enrolled in Medi‑Cal. Decreased Medi‑Cal enrollment will result in reduced state costs. Under a state individual mandate, most or all of the individuals who otherwise would have not enrolled in Medi‑Cal would still enroll, likely eliminating any reduced Medi‑Cal costs otherwise associated with the end of the federal individual mandate penalty. While very uncertain, these changes could result in state Medi‑Cal costs in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually that would at least partially offset penalty revenues generated by the state individual mandate, but would also reflect a reduced number of uninsured. Even after accounting for these potential state costs in Medi‑Cal, a state individual mandate likely remains a very cost‑effective option from a state budgetary perspective for increasing coverage and reducing premiums.

Enacting State Individual Mandate Involves Some Trade‑Offs. A state individual mandate would have additional costs beyond the state budget. Unlike other policy options that directly subsidize consumers, the individual mandate reduces premiums primarily by bringing additional, lower‑risk individuals to the insurance risk pool. These individuals would have the cost of purchasing coverage they otherwise would not have purchased, although they would also benefit from greater access to health care services and reduced financial risks from not having insurance. Revenues from the individual mandate would come at the expense of individuals who choose to pay the penalty instead of obtaining coverage. In addition to the cost of the penalty, these individuals would not benefit from insurance coverage.

Modeling State Mandate on Federal Mandate Has Benefits . . . Since the federal individual mandate has been in effect for a few years, households are now generally familiar with its structure. Closely modeling a state mandate on the federal mandate could make understanding and complying with a state mandate easier. Additionally, policies have already been developed for the operation of the federal individual mandate. The state could create a state individual mandate more efficiently by adapting existing federal policies and structures for the California context.

. . . Although the Legislature Could Consider Some Changes. At the same time, in enacting a state individual mandate, the Legislature could consider some changes to the federal individual mandate, depending on its policy priorities. For example, the state individual mandate penalty in Massachusetts is generally lower than the federal penalty, particularly for lower‑income households. Such changes could potentially serve to reduce the impact of the penalty on certain populations, but would need to be balanced against potential weakening of the mandate’s deterrent effect and possible increased complexity of implementation and administration.

State Subsidies Would Be Relatively Modest . . . Assuming that total state spending on the Governor’s proposed insurance subsidies would be roughly $500 million (consistent with the rough estimated amount of penalty revenues from the individual mandate), the subsidies would be relatively modest compared to the existing federal insurance subsidies. By comparison, federal spending on individual market subsidies in California is estimated to be over $6 billion in 2018.

. . . But Would Likely Ease Compliance With State Mandate. At the same time, these subsidies would reduce the cost of coverage for households that are eligible to receive them and would ease compliance with a state individual mandate. In light of the trade‑offs associated with implementing a state individual mandate, we think the Governor’s proposal to consider the individual mandate in conjunction with proposals that would reduce the cost of coverage makes sense.

Multiple Policy Options to Increase Coverage and Improve Affordability

Should the Legislature wish to enact policies to accomplish the twin goals of improving affordability and increasing coverage in the individual market, there are several options to choose from, in place of or in combination with those included in the Governor’s proposal. Available options include those presented in Covered California’s report, such as variations on additional state‑funded premium subsidies or CSRs for households below 400 percent of FPL, new premium subsidies for households above 400 percent of FPL, and a state reinsurance program. Different policy options to improve affordability and increase coverage present different trade‑offs. Choosing which, if any, policies to enact will require weighing these trade‑offs against the Legislature’s priorities. Below, we outline some key decision points for the Legislature’s deliberations.

Assistance for Currently Subsidized Versus Unsubsidized Households. One decision point is whether to focus assistance on households below 400 percent of FPL, households above 400 percent of FPL, or both. Some policy options, such as the state individual mandate and reinsurance, would primarily have the effect of reducing premiums in the individual market. These policies would directly lower the cost of coverage for households currently enrolled in individual market coverage without federal subsidies, since these households are exposed to the full premium charged by insurers. For this reason, these policies are projected to significantly reduce costs and increase enrollment among unsubsidized households.

However, premium changes that result from these policies (the state individual mandate and reinsurance) would not significantly affect households that are currently receiving federal subsidies, since the APTC would adjust downward to reflect reduced premiums so that subsidized households’ net premium cost would remain the same. (The individual mandate is projected to increase enrollment among current subsidy‑eligible households not because of its effects on premiums, but primarily because the penalty provides an incentive for people to remain insured.) Instead, in order to reduce the net premiums for individuals currently receiving subsidies, the state would need to provide additional premium subsidies on top of the federal APTC. Alternatively, providing additional assistance to reduce out‑of‑pocket costs, such as through state CSRs, is another avenue to provide assistance to households currently receiving federal subsidies.

Premium Assistance Versus Reduced Out‑of‑Pocket Costs. Another decision point is whether to focus on reducing premiums, out‑of‑pocket costs, or both. Research suggests that consumers are more sensitive to the premium cost of insurance in the individual market than they are to the level of out‑of‑pocket costs. As a result, policies that reduce premium costs, such as premium subsidies and reinsurance, are more likely to result in larger increases in new enrollment than policies that are intended to reduce out‑of‑pocket costs, like state CSRs. However, reducing out‑of‑pocket costs can be a goal in its own right, as it can increase access to health care services. Reducing out‑of‑pocket costs may also make it more likely that individuals that take up coverage remain insured. If increased new enrollment is a priority, then policies that reduce premiums would be preferred. Policies that reduce premiums can also result in reduced cost sharing to the extent that households take advantage of lower premiums to purchase more comprehensive, higher‑tier plans. However, if improving access to health care and encouraging the currently insured to remain insured is the priority, then CSRs may be more direct and may be the preferred policy.

Funding Level. The Legislature would also need to determine at what level to fund affordability policies. The Governor proposes to fund state subsidies consistent with the amount of penalty revenues generated by a state individual mandate. As noted previously, subsidies funded at this level would likely be relatively modest compared with federal subsidies currently available. As outlined in the Covered California report, larger impacts on coverage and affordability may be possible, but would require a substantial commitment of state funding. Projections in the Covered California report provide a helpful guide for gauging the impact on coverage enrollment of various options and spending levels. This can facilitate balancing potential state spending on insurance subsidies against other state funding priorities. The Legislature will also need to decide whether to use revenues from an individual mandate penalty to fund affordability policies, use other funding sources, or a combination of both.

Initial Comments on Implementation Issues

In this section, we highlight several issues related to implementation that could arise in relation to the Governor’s proposals or alternative policy packages the Legislature may evaluate.

Funding Subsidies Solely From Penalty Revenues Could Be Problematic. If subsidies were to be funded solely from penalty revenues, problems could arise for a few reasons. First, the goal of the individual mandate penalty as a deterrent against people foregoing health insurance coverage is at odds with the goal of generating funds for insurance subsidies. Prioritizing the goal of deterrence would mean maximizing compliance with the mandate and minimizing penalty revenues, which would have the effect of reducing funding available for subsidies. Prioritizing the goal of funding subsidies would mean maximizing penalties, or minimizing compliance with the mandate.

Second, the effects of the state individual mandate and insurance subsidies will interact—increasing enrollment through the individual mandate will make state subsidies more costly, and reducing the net cost of coverage with state subsidies will in turn increase the number of people taking up coverage, reducing the amount of penalty revenues generated. Accounting for this interaction would be a key part of designing subsidies that would be funded solely from penalty revenues.

Finally, if the amount of penalty revenues collected is not stable over time, there could be a need to update the structure of state subsidies. This could be disruptive for administering agencies and for households that receive the subsidies. One way to address these issues would be to use whatever penalty revenues are generated to simply offset—at least partially—the cost of subsidies, with other state funds covering any difference.

One‑Time State Funding Might Be Required Until Penalty Funds Are Available. Assuming a state individual mandate penalty is modeled after the federal penalty, revenues from the penalty would first be collected through state tax returns in the months following its first year of implementation. In contrast, many options for providing state subsidies, such as premium assistance that is advanced throughout the year, would result in costs in the same year that the assistance is provided. If the Legislature wished to use penalty funds to cover some or all of the costs of subsidies but wants to avoid the penalty being in place before subsidies are available, the state may need to provide one‑time startup funding from other sources to cover the costs of the first year of subsidies.

In General, Closely Modeling Premium Subsidies on Federal APTC Would Reduce Implementation Complexity . . . Covered California and health insurers have developed systems and processes to administer the federal APTC. These include Covered California information technology systems that collect household information, verify this information against electronic data sources, estimate APTC amounts, and allow households to apply APTC to a chosen health plan. Processes also exist for regular reconciliations among Covered California, the federal government, and health insurers to account for changes in household circumstances that impact the eligible tax credit amount after it has been advanced. If the Legislature wished to provide state premium subsidies, closely modeling them on the federal APTC could allow the state to utilize systems and processes developed for the APTC, reducing implementation complexity and cost.

. . . But Some Adjustments to Final Reconciliation Process Worth Considering. The federal APTC—specifically the portion that is advanced—is adjusted throughout the year to reflect changes in household circumstances, with a final reconciliation at the end of the year as households file their taxes. Closely following this model in California would involve households reconciling their advanced credit amounts on their state income tax returns. This final reconciliation may provide an additional level of accuracy and increase program integrity, but would also add to administrative complexity and cost. Other states that have state premium assistance (Massachusetts and Vermont) fully advance the assistance to immediately reduce premiums and do not reconcile subsidy amounts at the end of the year through their tax system. (In this sense, the state premium subsidies in these states are not actually tax credits like the APTC.) As the Legislature evaluates the possibility of providing a state‑funded premium subsidy in California, it could consider whether reconciling premium subsidies through the tax system adds sufficient value to justify the additional costs, or whether to adopt an approach similar to that used in these other states.

State CSRs Likely More Challenging to Implement and Administer Than State Premium Subsidies. For at least two reasons, state CSRs would likely be more complex to administer than state premium subsidies. First, initial implementation of federal CSRs was complex and involved extensive reconciliation activities. Second, the current federal administration determined in October 2017 that it lacked the authority to make CSR payments to insurers and discontinued the payments. In response to this change, California and many other states adopted a strategy under which the cost of continuing to provide enhanced silver plans is largely covered by increased federal APTC. It is unclear how the state’s strategy in response to the end of federal CSR payments might affect the implementation of a state CSR subsidy. If the Legislature wished to pursue state‑funded CSRs, these and potentially other implementation questions would need to be addressed.

Legislative Guidance Would Be Needed on Desired Level of Mandate Enforcement by FTB. Finally, how FTB would administer a state individual mandate, and at what cost to the state, will significantly depend on what level of enforcement the Legislature desires. Stronger enforcement of a state mandate would likely require enhanced coordination and data‑sharing among agencies and additional resources for FTB to review tax filings. Increased enforcement could also increase the deterrent effect of the mandate. If the Legislature proceeds with a state individual mandate, it will be important to consider the benefits of additional enforcement against its costs.

Recommendations

Individual Mandate Proposal Warrants Serious Consideration. While the full extent of a state individual mandate’s impact on improving insured levels and reducing individual market premiums is subject to some uncertainty, it may be one of the most effective policy tools available to the state to accomplish these twin goals. Because it raises revenues (likely at least partially offset by increased state costs in Medi‑Cal), the individual mandate is also very cost‑effective from a state budgetary perspective. However, a state individual mandate would result in costs for some households purchasing coverage that otherwise would not, and others paying penalties while remaining uninsured. On balance, we recommend that the Legislature give serious consideration to the Governor’s proposal.

To address some of the trade‑offs inherent in the proposal related to increased costs borne by individuals that do not comply with the mandate, the Legislature could consider making adjustments to the structure of the state mandate relative to the federal mandate. For example, the Legislature could consider adjusting the amount of penalties paid at different income levels or types of exemptions that are available. Additional state assistance to reduce the cost of coverage could also help alleviate the negative impact of the individual mandate penalty on some households.

Consider Proposed State Subsidies Among Range of Additional Policy Options to Improve Affordability. The administration has so far provided few details on the structure of the Governor’s proposed insurance subsidies. However, we think it makes sense to consider a state individual mandate in conjunction with policies to further reduce households’ insurance costs. We recommend that the Legislature consider the Governor’s proposal in the context of a range of policy options, such as those presented in Covered California’s affordability report, and consider what policies would best align with the Legislature’s policy priorities and desired level of General Fund commitment.