LAO Contacts

See These Related

2019-20 Budget Reports

February 20, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Considerations for the

Governor’s Housing Plan

Summary

Housing in California has long been more expensive than most of the rest of the country. Addressing California’s housing crisis is one of the most difficult challenges facing the state. The 2019‑20 Governor’s budget includes various proposals aimed at improving the affordability of housing in the state. Specifically, the Governor proposes (1) providing planning and production grants to local governments, (2) expanding the state Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit program, (3) establishing a new state housing tax credit program targeting relatively higher‑income households, and (4) expanding a loan program for middle‑income housing production.

The Governor’s housing proposals raise questions about which populations to prioritize. The Legislature will need to decide if it agrees with the Governor’s approach to spread the state’s housing resources among broader income levels—including middle‑income households—or whether it prefers to target the state’s resources toward the Californians most in need of housing assistance. Because the need for housing assistance outstrips current resources and there are fewer policy options to address affordability for low‑income households, we suggest the Legislature consider prioritizing General Fund resources towards programs that assist low‑income households.

Given that the Governor’s proposals are largely conceptual at this stage, we highlight key questions the Legislature might want to ask the administration as it considers the merits of the proposals, including: (1) the timeline for awarding new affordable housing funding, (2) plans to fund future maintenance costs associated with affordable housing developments, and (3) the state’s approach for administering the newly proposed state housing tax credit program.

Lastly, we note that the enormity of California’s housing challenges suggest that policy makers explore a variety of solutions. While the Governor proposes a few approaches to address the state’s high housing costs, the Legislature could pursue a variety of other tactics that address these and/or other facets of the state’s housing crisis.

Background

Building Less Housing Than People Demand Drives High Housing Costs. Housing in California has long been more expensive than most of the rest of the country. While many factors have a role in driving California’s high housing costs, the most important is the significant shortage of housing, particularly within coastal communities. A shortage of housing along California’s coast means households wishing to live there compete for limited housing. This competition increases home prices and rents. Some people who find California’s coast unaffordable turn instead to California’s inland communities, causing prices there to rise as well. Today, an average California home costs 2.5 times the national average. California’s average monthly rent is about 50 percent higher than the rest of the country. High housing costs drive California’s official poverty rate from roughly 13 percent (slightly higher than average) to 19 percent (highest in the nation) under the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which takes into account food, clothing, shelter, and utilities. Though the exact number of new housing units California needs to build to address housing affordability is uncertain, the general magnitude is enormous. We summarize our prior research that attempted to estimate the magnitude of the state’s housing shortage in the nearby box.

Estimating California’s Housing Shortage

In our March 17, 2015 report, California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, we estimated the amount of housing that—had it been built between 1980 and 2010—would have kept California’s median housing price from growing faster than the nation’s. We found that on top of the 100,000 to 140,000 housing units typically built in the state each year, the state probably would have to build as many as 100,000 additional units annually—almost exclusively in its coastal communities—to seriously mitigate housing affordability problems. Under this approach, California’s median housing prices still would have grown between 1980 and 2010, but the rate of growth would have been slower and comparable to that in the rest of the country. Under this housing supply scenario, California’s housing prices would have been 80 percent higher than the national median in 2010, instead of reaching twice the national median (as actually occurred). This suggests an aggregate of about 3 million additional housing units would have been needed between 1980 and 2010 to keep California’s housing cost growth in line with cost escalations elsewhere in the nation.

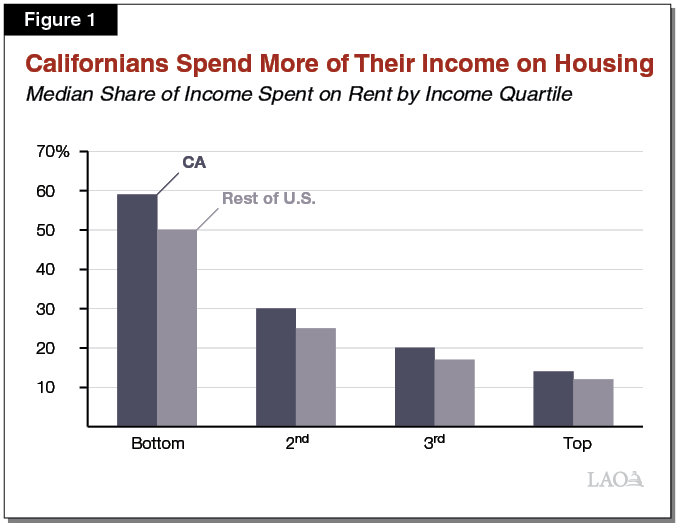

Many Households Have Difficulty Affording Housing in California. Housing costs are the largest component of most households’ spending each month. For homeowners, these costs include monthly principal and interests payments; property taxes and homeowner’s insurance; and household utilities like water, gas, and electricity. For renters, housing costs are their monthly rent and any utilities the tenant pays. Despite higher incomes relative to the rest of the country, for most California households, higher housing costs consume a large portion of their income. Specifically, the typical California household spends about 26 percent of their monthly income on housing. The typical household in the rest of the country, on the other hand, spends about 20 percent. Some households in California spend significantly more on housing. Over 1.5 million low‑income renter households in California report spending more than half of their income on housing. This is about 11 percent of all California households, a higher proportion than in the rest of the country (about 7 percent). Figure 1 depicts the share of income spent on rent by income quartile. The figure demonstrates that Californians spend a larger share of their income on rent than households in the rest of the nation at every income quartile and households with the lowest income face the highest rent burden.

Housing Affordability Challenges Even Middle‑Income Households. Households that pay more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing are generally considered cost burdened and may therefore have difficulty affording other necessities, such as food, clothing, transportation, and medical care. While low‑income households are the most likely to be cost burdened, high housing costs, particularly in California’s coastal communities, have created affordability challenges for middle‑income households. About 1 million households at or above California median income (households earning above $70,000 annually) in the state are cost burdened. (In California, around 2.5 million low‑income households are cost burdened.)

State Historically Has Provided Housing Assistance to Low‑Income Californians. In recent decades, the state has approached the problem of housing affordability for low‑income Californians by (1) subsidizing the construction of affordable housing and (2) reducing the housing costs for some households. Below, we provide additional information on these government housing programs.

Various Government Programs Help Californians Afford Housing. Federal, state, and local governments fund a variety of programs aimed at helping Californians, particularly low‑income Californians, afford housing.

- Various Programs Support Building New Affordably Priced Housing. Federal, state, and local governments provide direct financial assistance—typically tax credits, grants, or low‑cost loans—to housing developers for the construction of new rental housing. In exchange, developers reserve these units for lower‑income households. Data suggests these programs together have subsidized the new construction of over 8,000 rental units annually in the state—or about 7 percent of total public and private housing construction—over the past two decades. In addition to direct subsidies, some local governments increase the supply of affordable housing by requiring developers of market‑rate housing to charge below‑market prices and rents for a portion of the units they build, a policy called “inclusionary housing.”

- Programs That Help Households Afford Housing. In addition to constructing new housing, governments also have taken steps to make existing housing more affordable. In some cases, the federal government makes payments to landlords—known as housing vouchers—on behalf of low‑income tenants for a portion of a rental unit’s monthly cost. About 400,000 California households receive this type of housing assistance. These payments generally cover the portion of a rental unit’s monthly cost that exceeds 30 percent of the household’s income. In other cases, local governments have policies that require property owners charge below‑market prices and rents. For example, some local governments limit how much landlords can increase rents each year for existing tenants. Several California cities have these rent controls, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose.

Need For Low‑Income Housing Assistance Outstrips Resources. About 3.1 million low‑income households (who earn 80 percent or less of the median income where they live) rent housing in California, including 2.3 million very‑low‑income households (who earn 50 percent or less of the median income where they live). The amount of resources supporting existing federal, state, and local affordable housing programs is not sufficient to assist all of these households. Around one‑quarter (roughly 800,000) of low‑income households live in subsidized affordable housing or receive housing vouchers. Because programs that aim to build affordable housing have historically accounted for only a small share of all new housing built each year, they alone have not addressed the state’s housing needs. Moreover, most households receive no help from voucher programs. Those that do often find that it takes several years to get assistance. Roughly 700,000 households are on waiting lists for housing vouchers, almost twice the number of vouchers available. The scale of these programs—even if greatly increased—could not meet the magnitude of new housing required to address affordability challenges for low‑income households in the state.

Overview of the Governor’s Housing Plan

In the 2019‑20 January budget, the Governor includes various proposals aimed at improving the affordability of housing in the state. These proposals are largely conceptual and no details were included in the trailer bill legislation released by the administration in early February. We understand the administration is developing additional legislation related to its housing plan that could provide further information about the Governor’s vision. Below, we describe the Governor’s proposals to date. Figure 2 summarizes the Governor’s key housing proposals in the 2019‑20 budget.

Figure 2

Governor’s 2019‑20 Housing Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

Description |

General Fund |

|

Planning grants to local governments |

Provides grants to local governments meant to accelerate meeting new short‑term housing production goals. |

$250 |

|

Production grants to local governments |

Provides general purposes funds to local governments as a reward for reaching “milestones” in their efforts to meet their short‑term housing production goals. |

500 |

|

State Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit program |

Expands existing state Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit program. |

300 |

|

New state housing tax credit program |

Establishes new state housing tax credit program targeting households with relatively higher incomes. |

200 |

|

Mixed‑Income Loan Program |

Expands existing program aimed at increasing middle‑income housing production. |

500 |

|

Total |

$1,750 |

Expands Existing State Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program. The budget proposes a total of $500 million one‑time General Fund towards housing tax credit programs. Of this amount, $300 million would be allocated to the state’s existing Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit program. The program provides a tax credit to housing developers for the construction of rental housing. In exchange, developers reserve these units for low‑income households. The household income of residents must be below 60 percent of area median income—$71,000 in San Francisco and $35,000 in Bakersfield. Given the competitive nature of the tax credit program, developers often commit to serving households with much lower income to bolster their application for the credit.

Establishes New State Housing Tax Credit Program Targeting Households With Relatively Higher Incomes. The remaining $200 million would be allocated to a new state tax credit program targeting housing development for households with relatively higher‑income levels. Specifically, the proposal targets developments for households with incomes between 60 percent and 80 percent of area median income. In San Francisco, households with incomes between $71,000 and $95,000 would be eligible, while the range for Bakersfield residents would be $35,000 to $47,000. For both the expanded and new state tax credits, the Governor’s budget assumes no reduction in revenues due to the tax credit in 2019‑20 or in its multiyear budget plan. (While the credits could be awarded in 2019‑20, the credit could not be claimed unit the housing has been built. The Governor’s budget plan reflects the lag between the awarding and claiming of the housing tax credits.)

Expands Program Aimed at Middle‑Income Housing Production. The Governor’s budget proposes $500 million one‑time General Fund to expand the California Housing Finance Agency’s Mixed‑Income Loan Program. (This is in addition to the $43 million allocated for the program in the budget with revenue from the recent real estate document recording fee.) Like the tax credit program discussed above, this program aims to increase housing production. However, this program provides loans to developers for housing developments that include housing for low‑ to middle‑income households. Specifically, the program would assist households with incomes up to 120 percent of area median income. Households with incomes up to $142,000 in San Francisco and $70,000 in Bakersfield would be eligible for housing constructed using funding from this program.

Provides Grants to Local Governments Aimed at Increasing Housing Production. The Governor proposes $750 million in one‑time General Fund grants to local governments meant to accelerate meeting new housing production goals. Specifically, $250 million would be available to cities and counties to support various activities, like conducting planning and making zoning changes, to help them meet new short‑term housing production goals. As local governments reach these new goals, an additional $500 million would be available to cities and counties for general purposes as a reward for reaching “milestones” in their efforts to meet their short‑term goals. (We evaluate this proposal in a separate report, The 2019‑20 Budget: What Can Be Done to Improve Local Planning For Housing? In addition, the report suggests a package of changes to improve the state’s existing long‑term planning process for housing.)

Other Housing Proposals. The Governor also introduces other proposals intended to remove barriers to affordable housing development.

- Building Affordable Housing on Excess State Property. The Governor has issued an executive order directing the state to identify excess state properties that are suitable for affordable and mixed‑income housing development. Ultimately the Governor aims to solicit affordable housing developers to build demonstration projects on excess state property that use creative and streamlined approaches to building (for example, using modular construction). The administration indicates that this approach is likely to produce housing units more quickly and cost‑efficiently than traditional projects because housing developers would not need upfront capital to purchase the land and would not need to wait for local review processes.

- Making Economic Development Tools More Attractive. Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) allow local governments to use property tax increment (the growth in property tax revenue year over year) to finance a wide variety of projects, including affordable housing. The Governor has proposed legislation that encourages the formation of additional EIFDs by authorizing districts to issue bonds without voter approval. Current law requires EIFD’s to secure approval from 55 percent of voters to issue bonds to finance major projects, like affordable housing developments.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we identify issues for the Legislature’s consideration as it deliberates the Governor’s housing proposals related to the state’s housing tax credit programs and the expansion of the Mixed‑Income Loan Program. As noted previously, our findings and recommendations related to the Governor’s $750 million proposal providing grants to local governments aimed at increasing short‑term housing production and revising the state’s long‑term planning process can be found in our recent report: The 2019‑20 Budget: What Can Be Done to Improve Local Planning For Housing?

How Should Funding Be Prioritized?

Housing Proposals Raise Questions About Which Population to Prioritize. The number of low‑income Californians in need of housing assistance far exceeds the resources of existing federal, state, and local affordable housing programs. Recent housing assistance programs have allocated the majority of funding to housing targeted at low‑income Californians. The Governor’s housing proposals spread limited resources to broader income levels, including middle‑income Californians. Specifically, the Governor’s budget includes a total of $700 million towards establishing a new state housing tax credit program directed at higher‑income households than previously targeted and significantly expanding a loan program that assists development of middle‑income housing. The Legislature will need to decide if it agrees with the Governor’s approach to spread the state’s housing resources among broader income levels, or whether it prefers to target the state’s resources toward the Californians most in need of housing assistance. Below, we provide the Legislature additional context as it considers this decision.

Various Approaches for Addressing Affordability Among Middle‑Income Households . . . Low‑income households can face challenges affording housing in communities across the nation. In contrast, middle‑income households face housing affordability challenges only in a limited group of communities where insufficient supply of housing drives up costs. We observe this effect most acutely in California’s coastal urban communities. The higher costs of housing in these communities can make it difficult for middle‑income households to afford other necessities, such as food, clothing, transportation, and medical care. While these households could stand to benefit from federal, state, or local housing assistance programs, other approaches could help address affordability among middle‑income households. In prior reports, we have found that the key remedy to California’s housing challenges is a substantial increase in private housing development, particularly in the state’s coastal urban communities. The Legislature could help address housing affordability for middle‑income households by removing the barriers to private development. Local resistance, environmental protection policies, and competition among builders for limited development opportunities all hinder private housing development. Policies that remove these barriers provide opportunities to improve affordability among middle‑income households. While the Legislature has taken steps in recent years to address some barriers to private housing development, opportunities remain for further improvement. Our aforementioned report and March 2015 report, California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, provide additional context on these and other impediments to private housing development.

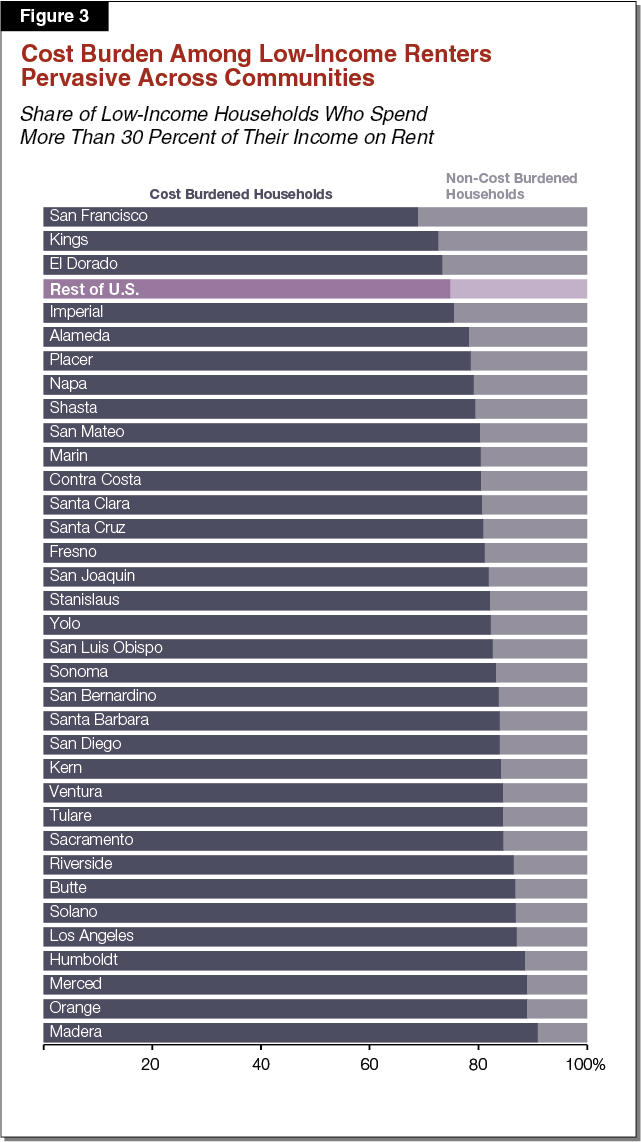

. . . Fewer Options Available for Addressing Housing Affordability Among Low‑Income Households. While an expansion of California’s housing supply would offer widespread benefits to Californians, even with a significant expansion of home building many low‑income Californians would still struggle with housing affordability. Figure 3 depicts the pervasiveness of affordability challenges among low‑income households throughout the state and in the rest of the nation. The figure demonstrates that low‑income households experience similar levels of rent burden across communities—suggesting that insufficient income creates housing affordability challenges even in low‑cost communities that have a sufficient supply of housing. Because of this, construction of affordable housing has a key role in helping low‑income households afford housing.

The cost of housing construction makes it difficult for affordable housing projects to be financially viable. Without federal, state, and local subsidies, affordable housing developments for low‑income households likely would not be available. Consequently, focusing government funding on programs that support these projects is the most effective and direct option for assisting these households. (While housing vouchers provide another option for low‑income households to access affordable housing, the success of this program is limited by the supply of landlords that are willing to accept vouchers. Evidence suggests that households with a housing voucher have trouble finding a landlord willing to accept it.)

Consider Prioritizing Low‑Income Households. Because the need for housing assistance outstrips resources and low‑income households have fewer options for accessing affordable housing, we suggest the Legislature prioritize General Fund resources towards programs that assist low‑income households. As noted earlier, the Legislature could continue to pursue broader changes that facilitate private housing construction, which would help address affordability challenges for middle‑income households.

Key Implementation Questions

Key Questions Surrounding Housing Proposals Remain. Given the conceptual nature of many of the Governor’s housing proposals, we highlight key questions the Legislature might want to ask the administration as it considers the merits of the proposals.

- What Is the Best Timeline for Awarding New Affordable Housing Funding? Even if the Legislature ultimately approves the Governor’s proposals, the Legislature should consider the best timeline for awarding the new housing funding. On the one hand, releasing the funding right away is consistent with the immediacy of the housing affordability problem and helps bring relief to Californians more quickly. On the other hand, the state has approved significant funding for affordable housing in recent years, most notably the $3 billion included in the Veteran and Affordable Housing Bond Act of 2018. Given the recently authorized funding, there might be some benefit to delaying the award of this funding until economic conditions weaken. Development and land costs likely will be cheaper during a recession, perhaps making it so that more affordable housing units could be built later than if the resources were used immediately. At the same time, other funding sources for development could be exhausted, so if this funding were available it could help serve as a backstop for affordable housing. This is akin to the Safety Net Reserve, which sets aside funds for future costs for the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids and Medi‑Cal programs in the event of a recession.

- How Will the State Address Future Maintenance Costs Associated With Affordable Housing Developments? Given the significant one‑time investments in affordable housing in recent years and the proposed one‑time investments by the Governor in 2019‑20, the Legislature should ask the administration how it plans to fund future maintenance costs associated with existing and future affordable housing developments. Without additional funding to preserve affordable housing, the state could see its advancement on affordability diminish over time.

- How Will the State Administer the New State Housing Tax Credit Program? How the state will administer the newly proposed state housing tax credit program aimed at increasing access to affordable housing for middle‑income households is unclear. We suggest the Legislature engage the administration in a discussion of the (1) allocation process, (2) eligible activities and program guidelines, and (3) expected housing production achievements.

Additional Opportunities Remain

The enormity of California’s housing challenges suggest that policy makers explore a variety of solutions. While the Governor proposes a few approaches for expanding the availability of affordable housing and helping middle‑income households afford housing, the Legislature could pursue a variety of other tactics that address these issues and other facets of the state’s housing crisis. For example, the Legislature could examine reforming local zoning laws, altering the allocation of local taxes to incentivize residential housing development, and streamlining the California Environmental Quality Act. In recent years, the Legislature has made progress on some of these fronts.

Conclusion

Addressing California’s housing crisis is one of the most difficult challenges facing the state’s policy makers. Millions of Californians struggle to find housing that is both affordable and suits their needs. The crisis also is a long time in the making, the culmination of decades of shortfalls in housing construction. And just as the crisis has taken decades to develop, it will take many years or decades to correct.

In light of the state’s housing crisis, the Governor’s interest in investing state resources on affordable housing is commendable. However, we questions the expansion of housing assistance programs towards broader income levels when other options are available to assist middle‑income households cope with high housing costs. Furthermore, given the conceptual nature of many of the Governor’s housing proposals, we highlight key questions the Legislature should ask the administration as it considers the merits of the proposals.