LAO Contacts

February 22, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Using Proposition 56 Funding in Medi-Cal

To Improve Access to Quality Care

Executive Summary

Medi‑Cal Delegates Much of the Delivery of Health Care Services to Managed Care Plans. Medi‑Cal provides health care coverage to 13 million low‑income Californians. Over 80 percent of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are enrolled in Medi‑Cal managed care plans, which are responsible for arranging and paying for most Medi‑Cal services on behalf of their members. Medi‑Cal managed care plans have flexibility in how they arrange for services, including how and how much they pay providers who furnish health care services under their networks.

State Imposes a Number of Access and Quality Standards on Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans. The state oversees Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ performance on a variety of state standards, including many related to access and quality. The state’s access standards require Medi‑Cal managed care plans to maintain adequate networks of providers. The state also enforces and reports on a number of measures of the quality of care that Medi‑Cal managed care plans provide to their enrollees.

Concerns About Access to Quality Care in Medi‑Cal Led to Proposition 56 (2016) Ballot Initiative. Stakeholders have long been concerned that access to quality care is limited in Medi‑Cal due to low provider reimbursement. These concerns led to Proposition 56—which raises state taxes on tobacco products and dedicates the majority of associated revenues to Medi‑Cal on an ongoing basis—being put on the statewide ballot in November 2016. Pursuant to Proposition 56, which was approved by voters, these revenues are to be used to improve payments to ensure timely access and ensure quality care. Currently, over $700 million in Proposition 56 funding supports provider payment increases in Medi‑Cal, with over half supporting payment increases for participating physicians and the balance supporting payment increases for other providers, such as dentists and family planning service providers. Pursuant to a two‑year budget agreement covering 2017‑18 and 2018‑19, Proposition 56 funding for provider payment increases in Medi‑Cal has been limited term.

Governor’s 2019‑20 Budget Proposes to Extend and Expand Proposition 56 Provider Payment Increases. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget proposes to make a number of changes to Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal. First, the Governor proposes to use all Proposition 56 funding on provider payment increases, which has the effect of raising General Fund costs in Medi‑Cal (since no amount of funding is proposed to offset General Fund cost growth in Medi‑Cal, as is currently done). Second, the Governor states an intent to make most of the Proposition 56‑funded provider payment increases permanent. Third, the Governor proposes new provider payment increases aimed at improving care in such areas as the identification of children with developmental delays and chronic disease management, the latter through a new “value‑based” payment program.

Following Our Preliminary Review, No Evidence of Widespread Noncompliance With the State’s Access and Quality Standards . . . We conducted a preliminary analysis of Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ performance relative to certain major components of the state’s access and quality standards. Based on our preliminary review, we have not identified widespread noncompliance with the state’s standards.

. . . But There Is Room for Improvement. However, we identify some potential areas for improvement. While Medi‑Cal managed care plans appear to be largely meeting state standards on primary care physician network adequacy, they appear to have more difficulty recruiting adequate numbers of specialists, particularly pediatric specialists. In terms of quality, Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ performance varies from fairly strong to warranting improvement.

Proposition 56 Physician Payment Increases Apply a Uniform Solution to Potential Deficiencies in Access to Quality Care That Vary Across Plans and Regions of the State. Where Medi‑Cal managed care plans have room for improvement very likely varies from plan to plan and from county to county. However, Proposition 56’s physician supplemental payments are uniform statewide and target largely non‑specialty services, where we find less evidence of access challenges. Accordingly, the existing approach may be not be adequately flexible to meet variable local health care conditions and needs. Moreover, no evaluation has been released on the impact of the existing Proposition 56 provider payment increases. As a result, their efficacy in improving access and quality in Medi‑Cal is unknown.

Proposition 56 Provider Payment Increases May Not Be Sustainable. As projected at the level proposed in the Governor’s 2019‑20 budget, annual spending on Proposition 56 provider payment increases exceeds annual Proposition 56 revenues for Medi‑Cal. Balances in the Proposition 56 fund account could cover these annual shortfalls in the short term, but General Fund could eventually be needed unless current projections are understated, the projected cost of provider payment increases is overstated, or changes are made to the Governor’s proposed use of this funding.

LAO Assessment and Recommendations. Following our review of access and quality in Medi‑Cal and the use of Proposition 56 funding to improve access and quality in Medi‑Cal, we find or recommend the following:

- Existing Provider Payment Increases Should Be Further Assessed Before Being Made Permanent. Given our concerns about the existing approach of Proposition 56 provider payment increases (particularly related to physician services provider payment increases), as well as the lack of evaluation showing their effectiveness, we recommend that the Legislature keep the Proposition 56 provider payment increases limited term. We recommend that the Legislature direct DHCS to produce a report on the efficacy of Proposition 56 funding in improving access to quality care in Medi‑Cal.

- Seriously Consider Proposed Value‑Based Payment Program, but Obtain More Information on All Proposed New Provider Payment Increases. Limited information is currently available on the new proposed provider payment increases, particularly the value‑based payment program. Accordingly, more information is needed before we can provide a recommendation on the value‑based payment program and certain of the other new proposed Proposition 56 provider payment increases. That said, we believe the value‑based payment proposal has the potential to improve areas with known deficiencies in Medi‑Cal, and therefore should be seriously considered.

- Reject Proposed Supplemental Payments for Developmental Screenings. The Governor’s developmental screenings proposal would increase payment for an activity managed care plans are already required to arrange and for which they are already compensated. The administration has not provided a compelling rationale for why increasing payments is the most cost‑effective approach to improving the identification of children with developmental delays. We recommend more cost‑effective strategies to improve the rate of developmental screenings and reporting be pursued before supplemental payments are provided.

Introduction

This report analyzes the use of Proposition 56 (2016) funding in Medi‑Cal to improve access to quality care. First, we provide background on how Medi‑Cal services are financed within Medi‑Cal’s multiple delivery systems. Then, we review how access and quality are monitored, primarily within Medi‑Cal’s managed care delivery system. We summarize how Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal has been used to date, and the changes proposed under the Governor’s 2019‑20 budget. Next, we assess Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ performance on selected state access and quality standards. Finally, we provide issues for consideration and recommendations on how to use Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal going forward to improve access to quality care.

Background

Medi‑Cal Is the State’s Medicaid Program. Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, is administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and provides health care coverage to over 13 million of the state’s low‑income residents. Coverage is cost‑free for most Medi‑Cal enrollees. Instead, Medi‑Cal costs are generally shared between the federal and state governments.

Overview of Major Medi‑Cal Delivery Systems

Medi‑Cal delivers health care services through several different delivery systems, each of which is funded, operated, and overseen in distinct ways. There are two main Medi‑Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: fee‑for‑service (FFS) and managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi‑Cal FFS may generally obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi‑Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans to provide health care coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Managed care plans are public or private health insurance plans that arrange and pay for the health care of their members. A parallel structure of FFS and managed care exists within Denti‑Cal, which covers dental services for Medi‑Cal enrollees. Denti‑Cal managed care is provided through specialized dental managed care plans that are distinct from the managed care plans that arrange and pay for broader Medi‑Cal services. We describe key features of these delivery systems below.

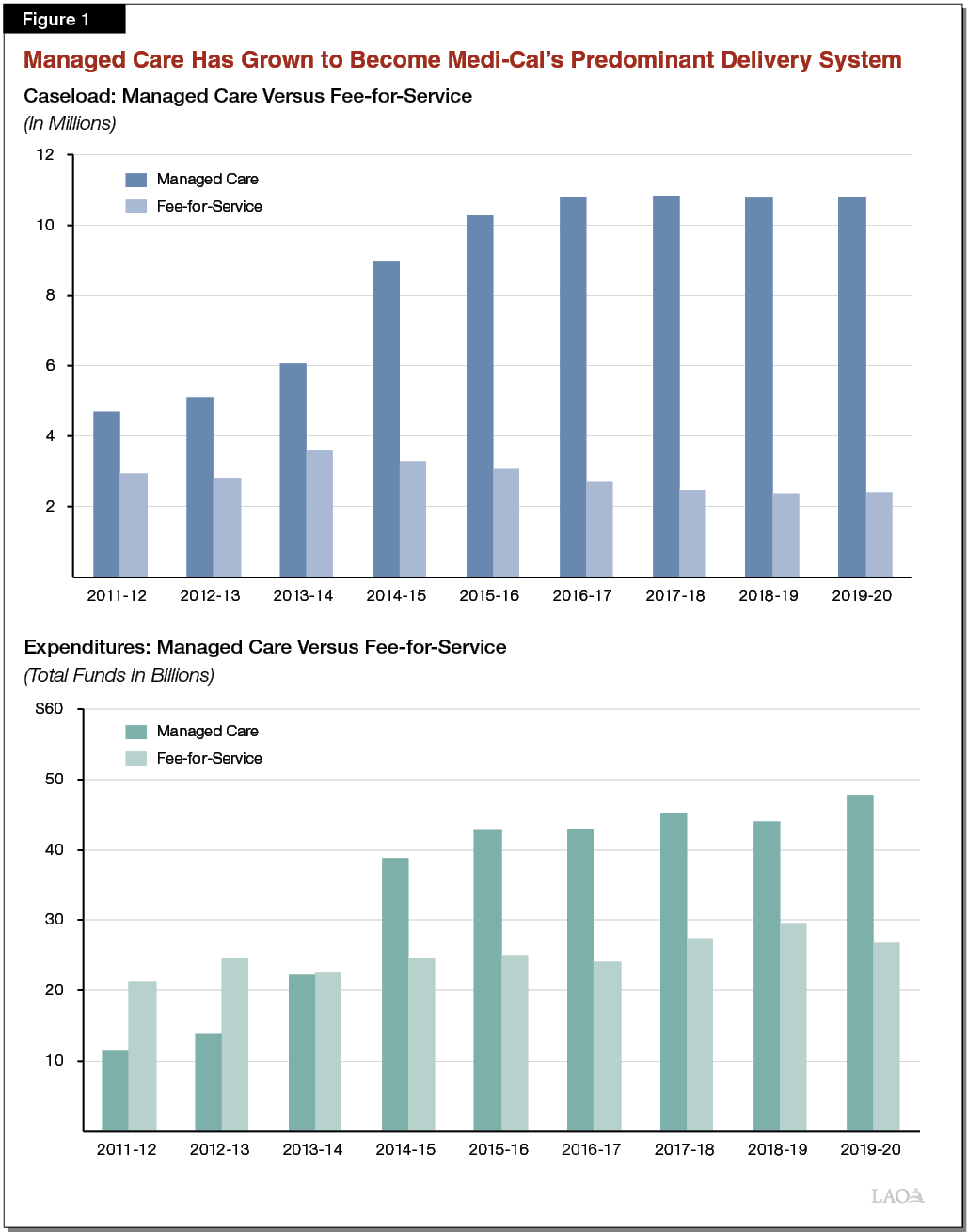

Managed Care Has Grown to Become Medi‑Cal’s Predominant Delivery System. Managed care enrollment is mandatory for most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, meaning these beneficiaries must access most of their Medi‑Cal benefits through the managed care delivery system. FFS enrollment largely consists of newly enrolled beneficiaries who will soon enroll in a managed care plan and certain select populations exempt from mandatory managed care, such as foster children. As shown in Figure 1, most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries (82 percent) are now enrolled in managed care. Over time, Medi‑Cal spending has similarly shifted from FFS to managed care. While physical health care services are primarily delivered through managed care, the vast majority of Denti‑Cal services are delivered through FFS Denti‑Cal.

State Directly Oversees and Administers Services Under FFS

Under FFS, DHCS is directly responsible for overseeing the care of FFS enrollees. Accordingly, DHCS carries out the following major activities to arrange and pay for the health care services available to Medi‑Cal FFS enrollees.

- Maintains a “Network” of Providers. To facilitate the delivery and reimbursement of services, DHCS enrolls health care providers into the Medi‑Cal FFS provider network, contracts with hospitals and other institutional care facilities (such as skilled nursing facilities), makes arrangements with pharmacies to dispense drugs, and performs a variety of other related tasks.

- Sets Payment Levels. DHCS establishes provider reimbursement levels, or “provider rates,” via state regulation. Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates are generally set on a statewide basis.

- Processes Payments. DHCS, with the assistance of contracted vendors, adjudicates and processes claims for payment for services rendered under Medi‑Cal FFS.

- Manages Service Utilization. Health care services are covered and reimbursed by Medi‑Cal to the extent they are medically necessary, typically as determined by a physician or other health care provider. Certain covered Medi‑Cal services and medical products, however, require administrative prior authorization in addition to a medical‑necessity determination by a provider before they are delivered. For example, many expensive prescription drugs require prior authorization before Medi‑Cal will pay for them. The use of prior authorization is intended to discourage the unnecessary use of health care services and medical products, particularly those that are relatively expensive.

Medi‑Cal FFS Provider Rates Relatively Low Compared to Rates Paid by Other Payers. Medicare, the federal program that provides health care coverage to 60 million elderly and disabled people nationwide, sets provider rates on an administrative basis, similar to Medi‑Cal. Since Medicare’s provider rates are public and serve as the basis of reimbursement for health care services on behalf of tens of millions of people, they are often used as a benchmark with which to compare the provider rates paid by other payers of health care services. Among the major categories of payers—commercial insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid—Medicare provider rates are understood to be moderately generous. That is, they are generally lower than the rates paid by commercial insurers, but generally higher than the rates paid by state Medicaid programs. For example, researchers have compared Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates to those paid under Medicare and found that Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates for physician services are about 50 percent of what Medicare pays. Commercial insurer providers rates tend to be around 50 percent higher than Medicare rates, though they vary significantly.

Managed Care: A Delegated Health Care Service Delivery Model

DHCS Contracts With Managed Care Plans to Arrange for Their Members’ Health Care Services. Medi‑Cal managed care is a delegated service delivery model whereby the state contracts with about 30 public or private managed care plans—such as Kaiser Foundation Health Plan—to arrange for covered health care services that the state would otherwise provide directly through Medi‑Cal FFS. As explained below, Medi‑Cal managed care plans are paid on a “capitated,” or per member, basis in return for arranging their members’ health care services. Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ various responsibilities are set in state law, state regulations, and in their contracts with DHCS, with ensuring access to health care services among the core responsibilities of Medi‑Cal managed care plans. Below, we summarize selected major responsibilities of Medi‑Cal managed care plans, which largely parallel those of DHCS under Medi‑Cal FFS.

- Maintain a Network of Contracted Health Care Providers. Rather than the state maintaining a network of contracted health care providers and facilities—as is the case in Medi‑Cal FFS—in Medi‑Cal managed care, managed care plans are responsible for establishing their own networks of participating providers and facilities. As described below, federal and state rules establish minimum requirements on the size and structure of Medi‑Cal managed care plan provider networks.

- Set Provider Reimbursement Rates. Medi‑Cal managed care plans, rather than the state, set their own provider reimbursement rates through negotiations with their network providers. As described below, the state’s role is to review the costs associated with these provider rates for reasonableness both from a state fiscal standpoint and a beneficiary access standpoint.

- Oversee Members’ Service Utilization. As the state does in FFS, Medi‑Cal managed care plans are charged with managing the service utilization of their members to ensure that members are receiving only medically necessary care.

- Provide Care Coordination. In addition to managing their members’ service utilization, managed care plans are charged with coordinating beneficiaries’ care. In general, this involves providing a “medical home” for their members, which is a primary care physician (PCP) to which members are assigned and through which they can be referred to specialty care and other supports.

Managed Care Plans Typically Operate Within and Vary Across Counties. The state contracts with managed care plans on a county‑by‑county or sometimes regional basis. Accordingly, different Medi‑Cal managed care plans serve different parts of the state. In 23 counties, the state contracts with a single managed care plan in each county to serve the vast majority of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries within that county. In 33 counties, the state contracts with two managed care plans, between which Medi‑Cal managed care enrollees may choose. In the remaining two counties, the state contracts with several managed care plans.

Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Paid on a Capitated Basis. Medi‑Cal managed care plans receive a predetermined amount of funding per member per month, regardless of the cost of services utilized by the member. We refer to these per‑member per‑month (PMPM) payments interchangeably as capitated rates. On an annual basis, DHCS, with the assistance of a contracted actuary, determines PMPM payment amounts through an actuarial capitated rate‑setting process. With a variety of adjustments, the fixed PMPM amounts are set to equal each Medi‑Cal managed care plan’s average costs of providing health care services to each of their members. Average member costs are computed using utilization and cost data from prior years, and subsequently trended forward using inflation factors. The PMPM payment amounts differ for distinct populations of Medi‑Cal enrollees whose health care costs tend to differ. For example, Medi‑Cal pays much higher capitated rates on behalf of seniors (around $600 per member per month for certain seniors) compared to children (around $100 per member per month). Medi‑Cal’s managed care capitated rates are certified by credentialed actuaries as actuarially sound. This certifies in the judgment of the actuaries that the capitated rates are projected to provide funding for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs of services that are required under Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ contracts with DHCS.

Use Capitated Payments to Fund Health Care Services Utilized by Their Members. Medi‑Cal managed care plans use the pooled funding from their capitated rates to pay for the Medi‑Cal services utilized by their members, as well as to pay for their administrative expenses. The portion of capitated rate funding that is not ultimately used to pay for health care services or administration is generally retained by the plans as profits, reserves, or used for other purposes.

Managed Care Plans Have Flexibility to Negotiate Their Own Provider Reimbursement Rates. As previously mentioned, DHCS does not set managed care plan provider rates—these are negotiated between managed care plans and providers. Generally, managed care plan provider rates may be as high as is reasonably necessary to ensure that members have sufficient access to health care services. DHCS oversees the reasonableness of provider rates through its reviews of managed care plans’ costs under the capitated rate‑setting process.

Managed Care Plans Use a Variety of Payment Methodologies. In addition to having flexibility around how much they pay their providers, Medi‑Cal managed care plans have flexibility to reimburse their network providers through a variety of payment methodologies. For example, many managed care plans “sub‑capitate” down to the provider level, whereby a physician group or clinic will receive a PMPM payment and be responsible for providing all contracted services to assigned members. In other situations, managed care plans pay for services on a FFS basis, at FFS reimbursement rates that are negotiated between the plan and the provider. In still other situations, managed care plans will pay either a “base” sub‑capitated or FFS provider rate, and supplement it with an incentive payment based on providers achieving a predetermined outcome or goal.

Managed Care Plan Provider Rates Are Generally Confidential. The provider rates paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans are generally considered a trade secret and therefore kept confidential. As a result, there is minimal transparency into what managed care plans pay their network providers.

Managed Care Plans Attest to Reimbursing Providers at Higher Levels Than Medi‑Cal FFS. For Medi‑Cal managed care plans, Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates often serve as the starting point of negotiations between the plans and providers, with increases beyond the Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates being agreed as needed. Although we do not have access to actual data on the provider rates paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans, we understand from public testimony and conversations with Medi‑Cal managed care plans that at least some plans pay higher provider rates than typically provided under Medi‑Cal FFS. Some Medi‑Cal managed care plans pay significantly higher than Medi‑Cal FFS—with certain plans sharing that they pay comparable provider rates to Medicare, which are generally understood to be about twice as high as Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates.

Capitated Payments Adjust Over Time to Account for Changes in the Provider Rates Managed Care Plans Pay. As previously discussed, capitated rates are updated annually to reflect changes in Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ costs. Changes in costs can reflect higher utilization on the part of their members—for example, as a result a bad flu season. Changes in costs can also reflect changes in the provider rates that managed care plans pay. For example, should a Medi‑Cal managed care plan experience difficulty in contracting with a sufficient number of oncologists (who treat cancer) in order to adequately serve its members, the plan may have to pay higher rates for oncology services to make the opportunity attractive to potential providers. Establishing higher provider rates for oncology services will generally raise the plan’s costs. Those higher costs will subsequently appear in the data used by DHCS to update the managed care plan’s capitated rates. As long as the costs associated with the oncology provider rate increase are deemed reasonable by the state’s use of actuarial standards, the plan’s capitated rates would then be adjusted upward to account for the associated higher costs. It should be noted that, in practice, it typically takes two to three years for a managed care plan’s higher costs, such as those associated with provider rate increases, to be reflected in higher capitated rates. To finance the provider rate increase until the capitated rate adjustment takes place, managed care plans have to reduce other spending, reduce their anticipated profits, and/or spend down their financial reserves. Ultimately, the delay in when capitated rates are adjusted has the likely effect of sometimes discouraging—but by no means forestalling—periodic provider rate increases within Medi‑Cal managed care.

Managed Care Financing Brings Benefits Relative to FFS . . . The financing of Medi‑Cal services differs markedly under managed care compared to FFS. Generally, Medi‑Cal managed care financing reflects an attempt to address some of the drawbacks of reimbursing health care services on a FFS basis. First, within Medi‑Cal, the use of managed care allows for variability in provider rates to reflect local differences in health care infrastructure and needs across the state. Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates, to the contrary, are generally established on a statewide basis. As a payment methodology, FFS tends to encourage utilization of health care services, since providers are paid for each service they deliver. In addition, FFS reimbursement in Medi‑Cal places full financial risk on the state, as the state will immediately bear the costs or savings of any spike or fall in the costs of services utilized. Managed care financing in Medi‑Cal addresses these drawbacks by giving managed care plans a global budget comprising the full amount of capitated payments that are provided, and tasking the plans with providing all necessary covered services using that funding. In this case, risk is transferred from the state to managed care plans, as plans are required to deliver services even if, in a given year, the costs exceed the funding provided.

. . . As Well as Drawbacks. Managed care financing in Medi‑Cal also brings significant trade‑offs. While having managed care plans negotiate provider rates facilitates a tighter alignment between the provider rates paid and the local health care market conditions than is possible under statewide FFS provider rates, this flexibility makes it more challenging for state policymakers to understand how much Medi‑Cal providers are being paid, and therefore whether access or quality may be negatively impacted by low provider rates. Moreover, managed care financing can reduce transparency into not only how much is being paid for a given service, but what services are being paid for and provided. Finally, as a payment methodology, given that managed care plans are paid a fixed amount per member per month, managed care financing can encourage lower utilization of services than may ultimately be desirable.

Supplemental Payments in Medi‑Cal

In addition to funding health care services through (1) FFS reimbursement and (2) capitated payments, a significant amount of Medi‑Cal funding (in the low tens of billions of dollars annually) goes to Medi‑Cal providers in the form of supplemental payments. Supplemental payments are paid on top of the base reimbursement rates that providers receive for a given Medi‑Cal service or on behalf of a given Medi‑Cal member. Major examples of Medi‑Cal supplemental payments include hospital supplemental payments and community clinic supplemental payments. Hospitals typically receive supplemental payments on top of the rates paid by Medi‑Cal FFS and Medi‑Cal managed care plans for inpatient stays. These supplemental payments are funded with a combination of local funds, special funds, and federal funds, and thus have the effect of increasing total hospital payment levels without affecting General Fund costs. Once these supplemental payments are factored in, reimbursement for hospital inpatient services in Medi‑Cal is generally thought to be comparable to the reimbursement levels available through Medicare.

Community clinics form a major part of Medi‑Cal’s PCP network, both in FFS and managed care. In managed care, plans negotiate their own provider rates with community clinics. However, certain community clinics are entitled to cost‑based reimbursement under federal law. To ensure these community clinics are reimbursed at cost, the state pays supplemental, or “wraparound,” payments to these clinics equal to the difference between the reimbursement level required by federal law and the amount paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans. The state and federal government share in the cost of these wraparound payments.

Access and Quality Monitoring in Medi‑Cal

Defining Access in Medi‑Cal

Access to Health Care Services Reflects Ability to Obtain Covered Services. At its most basic level, access represents the ability of Medi‑Cal enrollees to receive covered services in a timely manner when medically appropriate. For example, access means having sufficient available medical providers within a reasonable proximity as to allow a Medi‑Cal enrollee to make an appointment to receive services within a reasonable period of time. Health coverage through Medi‑Cal is not meaningful unless that coverage provides real access to services.

Quality of Care Is an Important Component of Access. Beyond basic access to services, the quality of services received through Medi‑Cal is also important. Health care services provided in Medi‑Cal can be thought of as “quality” to the extent that they (1) increase the likelihood of an individual’s desired health outcomes and (2) are consistent with recommended care based on current medical knowledge. Quality of care does not necessarily mean the ability to access a greater quantity of services, but rather depends on the ability to receive appropriate health care services based on recommended care and patients’ needs and preferences. In some instances, fewer or less costly services may actually be more appropriate and provide a higher level of quality. On the other hand, in some instances, certain services may be underprovided to patients and additional services may be appropriate. The state has different approaches to monitoring access and quality in Medi‑Cal’s two primary delivery systems, as described below.

FFS Access Monitoring

Federal “Equal Access” Provision. Federal law currently requires states to maintain sufficient providers in their FFS Medicaid programs so as to provide health care services that are at least comparable to those available to the general population. This requirement is often referred to as the equal access provision. However, the meaning of the equal access provision and how to determine whether a state complies with it has historically not been clear.

State Developed FFS Access Monitoring Plan. In 2015, the federal government issued regulations that clarified the meaning of the equal access provision, but did not establish nationwide access standards. Rather, the regulations required each state to develop its own plan for assessing whether its FFS Medicaid program has sufficient providers and access. Such plans must review (1) the extent to which beneficiary needs are met, (2) the availability of care, (3) changes in service utilization by beneficiaries, (4) beneficiary characteristics, and (5) payment levels in the Medicaid program and by other entities that pay for health care (such as private insurance). States are to develop their own standards and monitor access in their individual Medicaid programs in relation to those standards. Federal regulations specifically require states to evaluate the impact of any reductions or restructuring of payment rates in advance of submitting them for federal government approval. DHCS published California’s FFS access monitoring plan in September 2016. The state’s plan includes proposed methods and measures by which to evaluate access and identifies data sources for those measures. The state’s plan does not identify specific access challenges, but is intended to lead to a baseline against which access can be measured in the future.

Managed Care Access Monitoring

Federal and state law is considerably more prescriptive in establishing access standards in Medicaid managed care, relative to Medicaid FFS. Below, we summarize these standards.

Provider Network Adequacy Requirements. State law places various requirements on Medi‑Cal managed care plans in relation to access, as described below and displayed in Figure 2. (These requirements are comparable to or exceed those in the Knox‑Keene Act, which imposes various requirements on most managed care plans in the state, including those that do not participate in Medi‑Cal.)

- Provider Ratios. First, managed care plans are required to maintain minimum ratios of providers to enrollees in their service area. These standards consist of a higher ratio for PCPs and a second lower ratio that applies to a broader range of health care providers.

- Geographic Time and Distance Standards. Managed care plans are also required to contract with enough providers to limit the time and distance required for a beneficiary to travel to receive services from various types of providers. If a managed care plan can demonstrate to DHCS that it cannot meet these requirements after exhausting all reasonable efforts to contract with additional providers, DHCS may approve alternative time and distance standards. Beginning in 2018, managed care plans are required to certify that their networks meet these standards, or receive approval for an alternative standard, each year.

- Appointment Availability Requirements. Managed care plans are required to ensure that enrollees can obtain appointments to receive urgent and nonurgent health care services within specified time frames.

Figure 2

Network Adequacy Standards for Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans

|

Provider Ratios |

||||

|

One FTE primary care physician for every 2,000 enrollees |

||||

|

One FTE physician of any type for every 1,200 enrollees |

||||

|

Geographic Time and Distance Standards |

Dense Countiesa |

Medium Countiesb |

Small Countiesc |

Rural Countiesd |

|

Primary care (including OB/GYN primary care) and pharmacy |

10 miles or 30 minutes |

10 miles or 30 minutes |

10 miles or 30 minutes |

10 miles or 30 minutes |

|

Specialty care and mental health outpatient services |

15 miles or 30 minutes |

30 miles or 60 minutes |

45 miles or 75 minutes |

60 miles or 90 minutes |

|

Hospitals |

15 miles or 30 minutes |

15 miles or 30 minutes |

15 miles or 30 minutes |

15 miles or 30 minutes |

|

Appointment Availability Requirements |

Urgent |

Non‑Urgent |

||

|

Primary care (including OB/GYN primary care) |

Within 48 hours of requeste |

Within 10 business days of request |

||

|

Mental health outpatient services |

Within 48 hours of requeste |

Within 10 business days of request |

||

|

Specialty care |

Within 48 hours of requeste |

Within 15 business days of request |

||

|

aCounties with at least 600 people per square mile. bCounties with between 200 and 600 people per square mile. cCounties with between 50 and 200 people per square mile. dCounties with less than 50 people per square mile. eWithin 96 hours if prior authorization is required. FTE = full‑time equivalent and OB/GYN = obstetrician/gynecologist. |

||||

DHCS Performs Annual Managed Care Plan Audits. Each year, DHCS audits Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ compliance with various state requirements, including the network adequacy of the requirements just described. When a plan is found to have a deficiency, the state requires the plan to enter into a corrective action plan that identifies steps to address deficiencies.

Quality Measurement. DHCS assesses the quality of health care in the managed care delivery system in two main ways. First, DHCS requires managed care plans to report on an array of performance measures, referred to as the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), related to the process of providing health care and some health care outcomes. Plans are assessed on their performance on selected HEDIS measures against a “minimum performance level” that requires plan performance to be at least as good as the worst performing 25 percent of Medicaid managed care plans nationally. The state also provides an incentive for improved managed care plan performance by assigning new Medi‑Cal enrollees that do not choose a plan on their own to managed care plans that have higher scores on certain HEDIS measures. Second, DHCS surveys managed care plan enrollees about their perceptions of the quality of their managed care plan, their health care providers, and the services they receive. Figure 3 provides examples of HEDIS measures and consumer survey questions.

Figure 3

Managed Care Plan Performance Measures

|

Sample HEDIS Performance Measures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sample CAHPS Survey Questions |

|

|

|

|

aIncludes four diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis; three polio; one measles, mumps, and rubella; three Haemophilus influenza type B; three hepatitis B; one chicken pox; four pneumococcal conjugate; one hepatitis A; two or three rotavirus; and two influenza vaccines. HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Informaiton Set and CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. |

Relationship Between Access, Quality, and Provider Rates

Higher Provider Reimbursement Levels Likely Improve Access to Care and Potentially Quality, but Evidence Is Mixed. Standard economic theory suggests that paying health care providers more encourages providers to offer more services, all else being equal, thereby increasing utilization and potentially improving access. For example, in California, health care providers are relatively more willing to accept new commercially insured and Medicare patients, compared to new Medi‑Cal patients. To some degree, this likely relates to the higher provider rates paid by these other payers. Nationally, the evidence on whether increases in Medicaid provider rates increase access is somewhat mixed, with some research supporting and other research failing to support this hypothesis.

Provider rates also may impact the quality of care. For example, the more health care providers are paid for their services, the more time they may be willing to spend with their individual patients, as opposed to relying as heavily on service volume to cover their costs and maximize their earnings.

But Relationship Between Provider Rates and Access Is Complex and Depends Upon a Variety of Factors. The complexity of the relationship between provider rates and access likely contributes to the lack of consensus in the research on the impact of increasing provider rates on access to quality care. Geography plays a major role in shaping local residents’ access to health care services. While primary care services are largely available throughout California in urban and rural settings alike, specialty health care services are less likely to be available in more rural regions of the state. Rural areas have less population density and, therefore, fewer people to utilize health care services, particularly services that treat relatively rare conditions. As such, specialists will often not be able to cover their costs serving rural areas. While it is probably theoretically possible to raise provider rates high enough to eliminate geographic disparities in the availability of health care services, practically this is not feasible. Accordingly, provider rate changes will have variable impacts depending on geographic conditions and population density. Other factors, such as the degree to which there is competition among providers and provider reimbursement methodologies, also likely influence and add complexity to the relationship between providers rates and access to quality care.

Proposition 56 Provider Payment Increases

Proposition 56 (2016) Funding for Medi‑Cal. Proposition 56 raised state taxes on tobacco products and dedicates most revenues to Medi‑Cal on an ongoing basis. Funding from Proposition 56 for Medi‑Cal is intended to improve payments to ensure timely access, limit geographic shortages of services, and ensure quality care. Medi‑Cal began receiving Proposition 56 funding in 2017‑18. Proposition 56 currently provides about $1 billion annually to Medi‑Cal. Because tobacco use is projected to continue to decline on an ongoing basis—partially as a result of the new taxes put in place under Proposition 56—revenues from Proposition 56 for Medi‑Cal are expected to gradually decline on a year‑over‑year basis.

Overview of the Two‑Year Proposition 56 Agreement

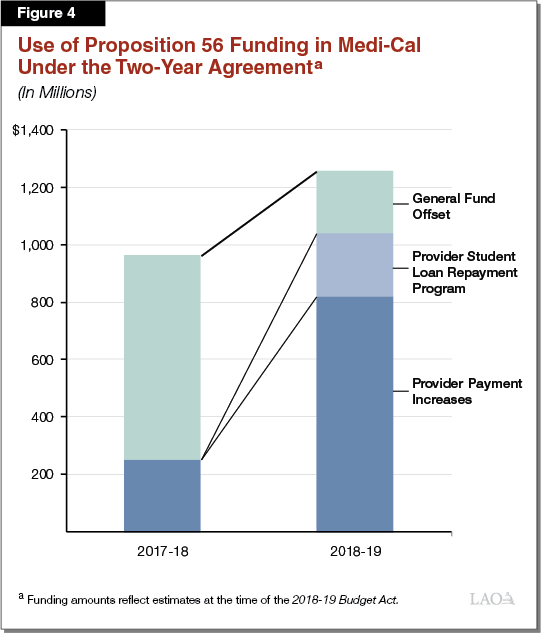

2017‑18 Budget Agreement. In 2017‑18, the Legislature and Governor Brown reached a two‑year agreement on how to use Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal. This agreement allocated Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal to two distinct purposes for both 2017‑18 and 2018‑19: (1) increasing provider payments and (2) offsetting General Fund spending on underlying cost growth in Medi‑Cal. In 2017‑18, $546 million was allocated for provider payment increases and $711 million was used to offset General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal. Under the 2017‑18 agreement, the amount of Proposition 56 funding dedicated to provider payment increases was to increase to up to $800 million in 2018‑19, provided the state’s fiscal conditions remained strong. Remaining available Proposition 56 funding would continue to be available to offset General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal. In approving the Proposition 56 provider payment increases, the administration stated an intent to evaluate the provider payment increases to determine whether they ultimately have the predicted effect of improving beneficiary access to care.

The Enacted 2018‑19 Budget Reaffirmed the 2017‑18 Agreement. The 2018‑19 budget generally allocated Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal in accordance with the 2017‑18 agreement, with most of the funding going to provider payment increases and a lesser amount used to offset General Fund spending in the program. The major changes made in 2018‑19 were:

- Downward Revision in Cost of 2017‑18’s Provider Payment Increases. In the 2018‑19 budget, the cost of the 2017‑18 Proposition 56 provider payment increases was revised downward by over 50 percent. This downward revision related to updated estimates of the federal share of cost for the Proposition 56 supplemental payments, reducing the state’s costs, and lower projected utilization of the services for which providers receive supplemental payments. This downward revision meant there was more Proposition 56 funding available for use in Medi‑Cal than was previously anticipated.

- New and Higher Provider Payment Increases. The 2018‑19 budget further increased payments for providers and services that had received increases in 2017‑18. In addition, the 2018‑19 budget expanded Proposition 56 provider payment increases to provider groups and service categories that had not previously received payment increases. This expansion was supported by freed‑up funding resulting from the revised cost estimate described above and the additional Proposition 56 funding dedicated to provider payment increases.

- Creation of a Physician and Dentist Student Loan Repayment Program. The 2018‑19 budget created a Medi‑Cal physician and dentist student loan repayment program using $220 million in available one‑time Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal. This funding is intended to be expended over multiple years. We note that the administration’s current implementation plan shows that, although the program will begin to implement over the next year, the funding will not begin to be spent until 2020‑21.

Figure 4 summarizes the use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal under the 2017‑18 two‑year agreement. Below, we describe how the Proposition 56 provider payment increases have been structured to date, and provide greater detail on the specific provider and service types that have received payment increases.

Overall Proposition 56 Supplemental Payment Structure. Most of the Proposition 56 provider payment increases take the form of supplemental payments that are paid on top of base provider rates, as opposed to being increases in base provider rates. The supplemental payments are fixed amounts of money and are paid upon the delivery of individual services. To illustrate how this works within Medi‑Cal FFS, suppose a provider furnishes a service to a Medi‑Cal enrollee—for example, a standard physician office visit—and then bills the state for the service. DHCS will then simultaneously pay the provider both the Medi‑Cal FFS base rate for a standard physician office visit and the applicable Proposition 56 supplemental payment. The supplemental payments work similarly in managed care, with providers receiving a fixed supplemental payment on top of base reimbursement following the rendering of eligible services.

Supplemental payments provide flexibility as they are easy to reduce or eliminate in the event, for example, of an economic downturn. Making reductions to base Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates, to the contrary, can be more challenging for the state because federal rules (previously discussed) that apply to provider rate reductions—but not reductions in supplemental payments—require enhanced state monitoring of the potential effect of a rate reduction on beneficiary access to services.

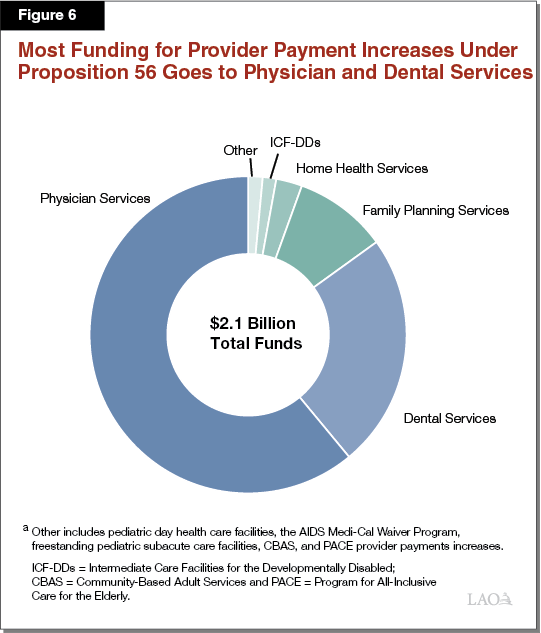

Including Federal Funding, Proposition 56 Provider Payment Increases Raise Medi‑Cal Provider Reimbursement Levels by $2 Billion in 2018‑19. The most recent estimate of total funding (including leveraged federal funds) for Proposition 56 provider payment increases in 2018‑19 is about $2 billion. Next, we provide an overview of the various Proposition 56 provider payment increases currently authorized.

Physician Supplemental Payments

Increases Physician Payments for Small Number of Common Primary Care and Outpatient Services. The largest amount of Proposition 56 funding for provider payment increases support supplemental payments for physician services ($409 million in Proposition 56 funding, and $1.3 billion in total funding once federal Medi‑Cal funding is included, in 2018‑19). These supplemental payments are available for a small set of common physician services: outpatient and office visits, preventive children’s (“well‑child”) visits, and psychiatric evaluation and management services.

Supplemental Payments in Medi‑Cal FFS. The physician services supplemental payment levels are set to make Medi‑Cal FFS reimbursement comparable to the rates paid by Medicare. Figure 5 provides examples of the Proposition 56 physician services supplemental payments, as they affect physician reimbursement in Medi‑Cal FFS.

Figure 5

Summary of Proposition 56 Supplemental Payments for Physician Services in Medi‑Cal FFS

|

Physician Service |

Base Medi‑Cal FFS Rate |

+ |

Supplemental Payment |

= |

Total Provider Reimbursement |

Medi‑Cal FFS Reimbursement as a Percent of Medicare |

|

|

Without Supplemental Payment |

With Supplemental Payment |

||||||

|

Office visit |

$34 |

$35 |

$69 |

42% |

85% |

||

|

“Well‑child” preventive office visit |

55 |

77 |

132 |

42 |

100 |

||

|

Psychiatric evaluation and management |

103 |

35 |

138 |

92 |

117 |

||

|

Note: Payment amounts reflect actual examples within the three categories of physician services that receive supplemental payments. FFS = fee‑for‑service. |

|||||||

Physician Services Supplemental Payments Also Paid Through Medi‑Cal Managed Care. Proposition 56 supplemental payments are also made for physician services delivered through Medi‑Cal managed care. The structure of the individual supplemental payments is the same in Medi‑Cal managed care as in FFS. That is, providers receive Proposition 56 supplemental payments for the individual supplemental payment‑eligible services they provide. However, there are important distinctions in how the funding flows to providers. First, rather than the state directly paying the supplemental payments to providers, funding for the supplemental payments goes to managed care plans through their capitated rates. (The funding amount equals the expected amount of funding managed care plans will need in order to make the supplemental payments upon delivery of a projected number of supplemental payment‑eligible services.) Using the additional funding received in their capitated payments, Medi‑Cal managed care plans then pay their providers a supplemental payment after an eligible service has been rendered and reported to the plan.

Dental Supplemental Payments

Increases Denti‑Cal Payments for a Large Number of Services. The second largest amount of Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal provider payment increases ($194 million) supports supplemental payments in Denti‑Cal. As with physician services, the dental supplemental payments are available in both Denti‑Cal FFS and Dental Managed Care. Unlike for physician services, where only a limited number of types of services (less than 30) receive supplemental payments, dental supplemental payments are spread across hundreds of different Denti‑Cal services. With exceptions, dental supplemental payment levels were set to increase Denti‑Cal provider rates by 40 percent.

Other Provider Payment Increases

Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal currently supports a number of other Medi‑Cal provider payment increases. These include funding for supplemental payments for family planning; intermediate‑care facilities for the developmentally disabled (ICF‑DDs); the AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program; and freestanding pediatric subacute facilities, and base provider rate increases for home health services and pediatric day health care facilities. In total, Proposition 56 funding for these other provider payment increases is $114 million in 2018‑19.

Figure 6 illustrates how Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal provider payment increases overall is targeted.

Implementation Update

Implementation of the Proposition 56 provider payment increases has met with some, generally anticipated, delays. Often these delays relate to the time line of federal approval of the provider payment increases. (Federal approval is required since Proposition 56 funding is matched with federal Medicaid funding to fully finance the payment increases.) The 2017‑18 provider payment increases were implemented beginning in 2017‑18 and have continued to be paid through 2018‑19. The new 2018‑19 provider payment increases—which are on top of the 2017‑18 increases—have generally either recently been implemented or are soon to implement over the next couple of months. In terms of overall funding, updated estimates of Proposition 56 spending on provider payments in the Governor’s January budget are relatively consistent with projections from the 2018‑19 Budget Act.

Governor’s 2019‑20 Proposition 56 Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes to extend and expand upon the previous two‑year agreement on the use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal. For 2019‑20, the proposal would spend just over $1 billion in Proposition 56 funding (more than $3 billion in total funds) on provider payment increases. Below, we outline the Governor’s proposal. Figure 7 summarizes the Governor’s proposed use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal.

Figure 7

Governor’s 2019‑20 Budget Dedicates All Proposition 56 Funding for Medi‑Cal to a Variety of Provider Payment Increases

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

||||

|

Proposition 56 Funds |

Total Funds |

Proposition 56 Funds |

Total Funds |

||

|

Existing Provider Payment Increases: |

|||||

|

Physician services |

$409a |

$1,299 |

$456 |

$1,387 |

|

|

Dental services |

194 |

510 |

217 |

547 |

|

|

Family planning services |

54 |

203 |

42 |

160 |

|

|

Home health services |

27 |

57 |

31 |

65 |

|

|

Intermediate Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled |

14 |

29 |

13 |

28 |

|

|

Pediatric day health care facilities |

6 |

12 |

7 |

14 |

|

|

AIDS Medi‑Cal Waiver Program |

3 |

7 |

3 |

7 |

|

|

Freestanding pediatric subacute care facilities |

3 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Program for All‑Inclusive Care for the Elderly |

5 |

5 |

— |

— |

|

|

Community‑Based Adult Services programs |

2 |

2 |

— |

— |

|

|

Subtotals |

($717) |

($2,130) |

($770) |

($2,209) |

|

|

New Proposed Provider Payment Increases: |

|||||

|

Value‑based payments |

— |

— |

$180 |

$360 |

|

|

Developmental and trauma screenings |

— |

— |

53 |

105 |

|

|

Medi‑Cal family planning |

— |

— |

50 |

500 |

|

|

Subtotals |

(—) |

(—) |

($283) |

($965) |

|

|

Subtotals, All Provider Payment Increases |

($717) |

($2,130) |

($1,052) |

($3,174) |

|

|

Offset to General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal cost growth |

$218 |

N/A |

— |

N/A |

|

|

Grand Totals, Proposition 56 Spending in Medi‑Cal |

$935 |

$2,130 |

$1,052 |

$3,174 |

|

|

aEstimated Proposition 56 funding for these supplemental payments has been revised significantly downward in the Governor’s January budget relative to the 2018‑19 Budget Act. However, total funding for these supplemental payments is actually higher than previously estimated. As such, this change results from an updated estimate of the federal share of cost for these payments—an update that is fiscally beneficial to the state. |

|||||

Proposal States an Intent to Make Most Provider Payment Increases Permanent. The Governor has stated an intent to make most of the provider payment increases—the existing as well as certain new supplemental payment programs—permanent and ongoing. However, the administration has not shared that it intends to propose budget‑related statutory language to effect this change.

Dedicates All Proposition 56 Funding to Provider Payment Increases. In 2019‑20, the Governor proposes to use all Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal on provider payment increases. This results in the elimination of the General Fund offset in 2019‑20, which has the effect of increasing General Fund costs in Medi‑Cal by $218 million.

Establishes New Supplemental Payment Programs. The Governor’s budget proposes to use $283 million in Proposition 56 funding to establish new supplemental payment programs. Federal approval of the new supplemental payment programs will be necessary to the extent they are supported with federal funds (as the administration currently assumes). At the time of this publication, many of the details of the new proposed programs remain in development. The following bullets provide basic background on these new proposed supplemental payment programs.

- Value‑Based Payment Program. The Governor proposes using $180 million in Proposition 56 funding ($360 million total funds) to create a value‑based payment program to improve the quality and efficiency of care within Medi‑Cal managed care plans. While details for the program remain under development, the intent is to establish incentive payments for managed care plans and their network physicians that will reward those that meet predetermined performance benchmarks. According to the administration, these payments are intended to improve care in three distinct focus areas: (1) chronic disease management, (2) prepartum and postpartum care, and (3) behavioral and physical health integration. To develop and implement the value‑based payment program, the Governor’s budget proposes 18 new permanent positions at DHCS at an annual cost of $1.5 million in Proposition 56 funds ($3 million in total funds).

- Payments to Encourage Timely Developmental and Trauma Screenings. The Governor’s budget includes $53 million in Proposition 56 funding ($105 million total funds) to expand physician screenings for (1) appropriate childhood development and (2) early identification of trauma. Of the total amount of proposed Proposition 56 funding, $30 million is for developmental screenings and $23 million is for trauma screenings. The funding would provide for a $60 supplemental payment for each developmental screening and either a $6.50 or a $23 supplemental payment for each trauma screening. Whereas developmental screenings are currently required and funded in Medi‑Cal, the introduction of trauma screenings would be largely new to the program.

- Extends Family Planning Payments to Broader Medi‑Cal Program. Currently, Proposition 56 funding is used to provide supplemental payments for family planning services within the Family Planning, Access, Care, Treatment Program (Family PACT) that is operated within Medi‑Cal. Family PACT serves state residents with incomes that are low but nonetheless too high for them to qualify for Medi‑Cal. The Governor’s budget proposes to provide similar supplemental payments within the broader Medi‑Cal program. $50 million in Proposition 56 funding is allocated for these payments, which, with an enhanced federal share of cost, will provide for $500 million in supplemental payments for these Medi‑Cal family planning services.

LAO Assessment

In this section, we first describe why focusing legislative oversight on access and quality within Medi‑Cal managed care is critical. We then provide our assessment of how well Medi‑Cal managed care plans perform on the state’s access and quality standards today. Finally, we assess the extent to which there are broad access concerns in Medi‑Cal managed care, and whether the current and proposed use of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal is well suited to addressing such concerns. We focus on the physician services supplemental payments, as well as the Governor’s new proposed supplemental payment programs. We provide particular attention to the physician services supplemental payments since they (1) represent the largest category of Proposition 56 provider payments at around two‑thirds of total funding and (2) interact with the Medi‑Cal managed care delivery system in ways that raise a number of questions. (Recall that Dental Managed Care makes up only a very small part of the Denti‑Cal program.)

Monitoring Access and Quality in Managed Care Is Critical

Medi‑Cal FFS Rates Among the Lowest in the Nation . . . By some estimates, California’s FFS provider rates rank among the lowest in the nation, at a little over half of comparable rates paid in the federal Medicare program. State Medicaid programs nationwide are believed to pay provider rates for physician services that are about two‑thirds of those paid by Medicare. Concerns have been raised that this level of reimbursement is not sufficient to maintain appropriate levels of access and quality in the Medi‑Cal program. However, we would caution against generalizing from the above findings on low Medi‑Cal FFS provider rates to the conclusion that Medi‑Cal provider rates are uniformly low and insufficient.

. . . But Large Majority of Medi‑Cal Enrollees Participate in Managed Care, Where Provider Rates Are Unknown. However, while the Legislature should ensure that appropriate access is maintained in the FFS system, less than 20 percent of Medi‑Cal enrollees participate in the FFS system. A significant majority of enrollees instead receive services through managed care. As described earlier, managed care plans set the rates paid to providers on behalf of the state. While certain Medi‑Cal managed care plans attest to paying higher providers rates than Medi‑Cal FFS, it is not known with certainty how rates paid to providers in the broader managed care system compare with Medi‑Cal FFS or with Medicaid managed care rates nationally. In addition, supplemental payments are regularly made on top of base provider rates to increase total provider reimbursement in Medi‑Cal managed care (as well as FFS).

Oversight of Access and Quality in Dominant Managed Care Delivery System Particularly Critical. In the delegated managed care system, the state pays capitated rates that are determined to be actuarially sound. In turn, managed care plans are contractually required to provide appropriate levels of access. In recent years, the Legislature and DHCS have taken steps to strengthen oversight of access and quality in Medi‑Cal managed care. In our view, given that the Legislature has chosen to largely delegate the delivery of Medi‑Cal services to managed care plans, the Legislature should continue to concentrate its oversight on managed care quality and access rather than on, for example, the level of FFS provider rates. We believe this focus is likely to have a greater impact on overall access and quality in the Medi‑Cal program.

Assessment of Managed Care Access and Quality

No Evidence of Widespread Noncompliance With Managed Care Network Adequacy Requirements. As of January 2019, all of the state’s Medi‑Cal managed care plans had certified compliance with required provider‑to‑enrollee ratios and geographic time and distance standards (in some cases by gaining approval of an alternative access standard, as we describe in greater detail below). Compliance with these and other requirements, including minimum appointment wait times, are reviewed by DHCS on an annual basis as part of the managed care plan audits. DHCS does identify deficiencies in plans’ compliance with these requirements from time to time and requires plans to take corrective actions. However, based on our preliminary review, the identified deficiencies do not appear to be widespread.

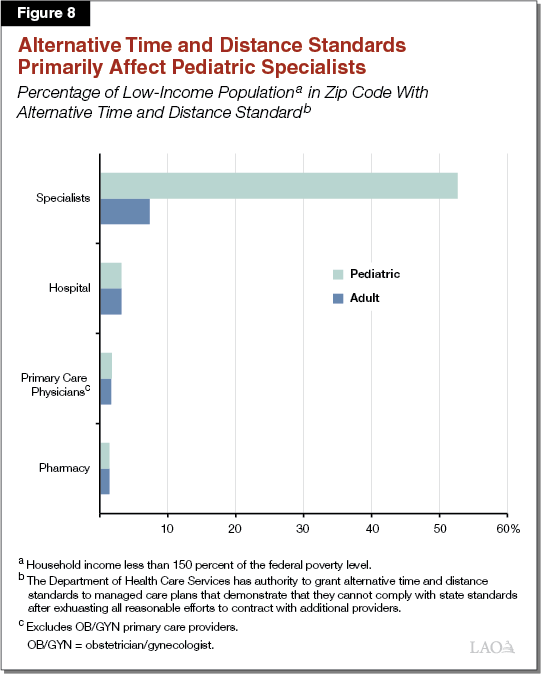

Analysis of Time and Distance Standards Highlights Instances Where Access May Be Particularly Challenging. As described earlier, the Legislature gave DHCS authority to approve alternative geographic time and distance standards for plans that can demonstrate that state standards identified in Figure 2 are not attainable after all reasonable efforts have been exhausted. In 2018, the first year of the new annual network certification process, DHCS reviewed hundreds of thousands of individual time and distance standards—reflecting all possible combinations of different managed care plans, zip codes, and provider types. Through this process, DHCS has to date approved almost 10,000 alternative standards. These alternative standards represent instances where Medi‑Cal enrollees could be required to travel for a greater length of time and over longer distances to reach certain providers than laid out in Figure 2 previously.

For this report, we conducted a preliminary analysis of where and for which providers DHCS approved alternative standards, and how these alternative standards changed the times and distances that Medi‑Cal enrollees may be required to travel under state law. We caution that time and distance standards are only one dimension of the state’s managed care access requirements and therefore do not conclusively show where access challenges may or may not exist. For example, having a provider in a managed care plan network in accordance with time and distance standards does not necessarily imply that the provider is sufficient to serve the Medi‑Cal population in the area. Other requirements—provider‑to‑enrollee ratios and appointment availability requirements—are also important in determining access. Highlights of our preliminary analysis are described below.

Managed Care Plans Appear to Largely Have Sufficient Contracted PCPs to Meet Time and Distance Standards. Figure 8 shows the estimated percentage of low‑income individuals (specifically, those with household income less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level [FPL], roughly similar to eligibility thresholds for Medi‑Cal) that live in a zip code where at least one Medi‑Cal managed care plan received approval of an alternative time and distance standard. As shown in the figure, only about 2 percent of the low‑income population was in a zip code where a managed care plan had an alternative time and distance standard for PCPs (as noted previously, state standards require PCPs to be within ten miles or 30 minutes). This suggests that managed care plans have relatively less difficulty recruiting PCPs.

Alternative Time and Distance Standards More Common for Pediatric Specialists. However, as shown in the figure, alternative time and distance standards were approved more often for pediatric specialists. This suggests that managed care plans have relatively greater difficulty locating and recruiting pediatric specialists. For relatively rare conditions, pediatric specialists may be less common in some parts of the state. For example, given the relatively low volume of patients for some pediatric specialties, these providers may be concentrated near centralized locations where specialized children’s conditions are often treated, such as children’s hospitals.

We also note that Figure 8 displays the portion of the low‑income population that lives in a zip code where any managed care plan has received an alternative access standard for any of the 17 types of specialists for which the state has a time and distance standard. The large number of types of specialists makes it more likely that a managed care plan would have an alternative time and distance standard for at least one type of specialist. Our analysis suggests that the share of the low‑income population in a zip code where a managed care plan has an alternative time and distance standard for any single type of pediatric specialist ranges from close to zero to around 35 percent. Across participating managed care plans, an average zip code had an alternative time and distance standard for roughly two of the various types of pediatric specialists.

Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plan Quality Has Room for Improvement. Medi‑Cal managed care plan quality is fairly strong according to certain benchmarks but not others. As shown in Figure 9, the average performance of Medi‑Cal managed care plans has typically been better than the average performance of Medicaid managed care plans nationwide on the majority of HEDIS measures. For example, in 2016, compared to the average performance of all Medicaid managed care plans nationally, the average performance of Medi‑Cal managed care plans was better than the national Medicaid average on 75 percent of HEDIS measures. At the same time, however, Figure 10 shows that the average performance of Medi‑Cal managed care plans is below the average performance of commercial managed care plans nationally on many measures. For example, in 2016, the average performance of Medi‑Cal managed care plans was better than the national commercial average on only 29 percent of HEDIS measures. In addition, there is significant variation in the quality scores of Medi‑Cal managed care plans. DHCS regularly publishes a single aggregated quality score, based on HEDIS measures, for each Medi‑Cal managed care plan. In the most recent release of these aggregated scores, managed care plan performance ranged from a low of less than 40 to a high of nearly 100 (scores may theoretically range from 0 to 100) and averaged 68.

Figure 9

Average Performance of Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Exceeds National Medicaid Average on Many HEDIS Measuresa

|

Percent of HEDIS Measures on Which Average |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

Average 2013‑2016 |

|

Above national Medicaid average |

55% |

55% |

45% |

75% |

57% |

|

Below national Medcaid average |

45 |

45 |

55 |

25 |

43 |

|

aThe number of HEDIS measures included in this analysis varies by year as follows: 22 measures in 2013 through 2015 and 24 measures in 2016. HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set. |

|||||

Figure 10

Average Performance of Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Below National Commercial Managed Care Plan Average on Many HEDIS Measuresa

|

Percent of HEDIS Measures on Which Average |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

Average 2013‑2016 |

|

Above national commercial managed care plan average |

32% |

27% |

32% |

29% |

30% |

|

Below national commercial managed care plan average |

68 |

73 |

68 |

71 |

70 |

|

aThe number of HEDIS measures included in this analysis varies by year as follows: 22 measures in 2013 through 2015 and 24 measures in 2016. HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set. |

|||||

On consumer surveys, Medi‑Cal managed care plans as recently as 2016 scored below the worst performing 25 percent of national Medicaid managed care plans on key dimensions, including overall quality of health care, the enrollee’s ease of getting needed care, and the enrollee’s ease of getting care quickly. The gap between Medi‑Cal managed care plan and national commercial managed care plan performance, the variability in performance among Medi‑Cal managed care plans, and relatively low performance of Medi‑Cal managed care plans on survey measures suggest that there is room for quality improvement.

Legislature May Wish to Improve Access and Quality Beyond Current State Standards. While Medi‑Cal managed care plans appear to be largely complying with the state’s network adequacy standards as laid out in current law, there are clearly areas where the Legislature might wish to pursue improvements to access. The analysis of alternative time and distance standards above suggests some potential areas of priority—specifically, pediatric specialists and travel times in rural parts of the state in particular. As noted above, there is also room for improvement of managed care plan quality. There are a variety of approaches the Legislature could take that could potentially improve access and quality of care in Medi‑Cal. These could include the existing Proposition 56 supplemental payments and some of the Governor’s proposed new uses for Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal like the value‑based payment program. In the following sections, we lay out our assessment of existing Proposition 56 provider payment increases and other new proposed uses for Proposition 56 funding in terms of their potential to improve access and quality in Medi‑Cal.

Physician Services Supplemental Payments Layer a FFS Reimbursement Approach Onto a Managed Care Structure

Proposition 56 provider payment increases, to date, reflect a FFS reimbursement approach where individual services receive individual supplemental payments (or in some cases, higher base rates). However, particularly for the physician services supplemental payments, they are employed primarily within the Medi‑Cal managed care setting (93 percent of physician services funding runs through managed care, with the remaining 7 percent in Medi‑Cal FFS). This raises a number of questions and concerns since Medi‑Cal managed care financing and network provider reimbursement differs fundamentally from the approach in Medi‑Cal FFS. Below, we reiterate some of these differences and their implications on the appropriateness of continuing to use the existing structure of physician services supplemental payments within Medi‑Cal managed care.

State Pays Actuarially Sound Capitated Rates to Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans to Ensure Access to Quality Care. Ensuring access to quality care is a core responsibility of Medi‑Cal managed care plans. Medi‑Cal managed care plans must pay adequate provider rates to maintain adequate networks of contracted providers. The state, in turn, is responsible for providing adequate, actuarially sound capitated rates to ensure Medi‑Cal managed care plans can meet all the standards, including those related to access and quality, that the state has in place.

Capitated Rate‑Setting Process Allows for Increases in Provider Rates to Address Access Challenges. The Medi‑Cal managed care capitated rate‑setting process allows for capitated rates to be continually updated to reflect changes in Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ costs. Accordingly, when Medi‑Cal managed care plans find it appropriate to increase provider rates, the associated costs eventually are incorporated into the capitated rate funding they receive from the state, as long as the state deems the costs associated with the provider rate increase to be reasonable. Because the capitated rate‑setting process is confidential, there is significant uncertainty as to how much scrutiny the state applies to the reasonableness of higher Medi‑Cal managed care plan costs as a result of provider rate increases. Nevertheless, since some plans pay provider rates that are comparable to what is paid in Medicare (as attested by these Medi‑Cal managed care plans), it is clear that Medi‑Cal’s capitated rate‑setting process can accommodate significantly higher provider rates to be paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans than those paid under Medi‑Cal FFS.

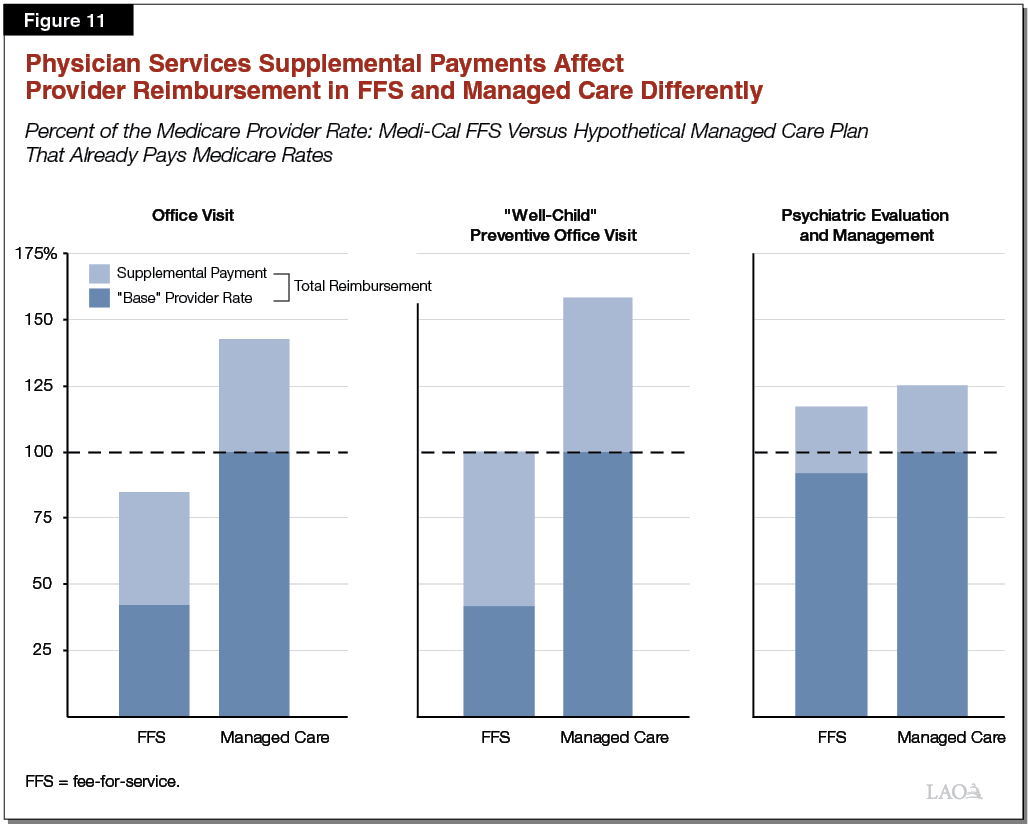

Physician Services Supplemental Payments Likely Have a Variable Impact on Medi‑Cal Managed Care Provider Payment Levels. Because the physician services supplemental payment amounts are fixed, but Medi‑Cal managed care provider reimbursement rates vary across plans, total reimbursement for physician services, with the Proposition 56 supplemental payments included, varies across plans. For Medi‑Cal managed care plans that pay provider rates comparable to Medi‑Cal FFS, the supplemental payments will bring network provider reimbursement levels close to Medicare levels, as was the intent and is the case in Medi‑Cal FFS. For Medi‑Cal managed care plans that already pay provider rates comparable to Medicare, the supplemental payments will bring network provider reimbursement levels well above Medicare reimbursement rates for the services that receive supplemental payments. Figure 11 illustrates this point for a hypothetical Medi‑Cal managed care plan that already pays providers at rates comparable to Medicare. That providers would be paid above Medicare reimbursement levels is by no means, on its own, a drawback. However, it raises questions as to whether Proposition 56 funding for provider payments increases is being targeted to the areas of greatest need.

A Uniform Approach to Local and Varied Deficiencies in Access to Quality Care. Where and how plans should devote resources for improvement likely varies from plan to plan and from county to county. However, Proposition 56’s physician supplemental payments are uniform statewide and target largely non‑specialty services. Accordingly, the approach may be not be adequately flexible to meet variable local health care conditions and needs.

Proposition 56 Provider Payment Increases May Not Be Sustainable

Proposed 2019‑20 Proposition 56 Spending in Medi‑Cal Is Greater Than Projected Proposition 56 Revenue for Medi‑Cal. The Governor’s budget proposes to use $1.05 billion in Proposition 56 funding on provider payment increases in 2019‑20. Proposition 56 revenues dedicated to Medi‑Cal are projected to be $1.02 billion in 2019‑20, and to decline on an annual basis thereafter. Moreover, scheduled changes in the federal share of cost for certain populations will increase the state’s share of cost for Medi‑Cal. This will require the state to pay for a somewhat higher share of the total cost of the Proposition 56 provider payment increases in the coming years if they are extended. Accordingly, unless the administration’s current spending projections are too high or its revenue projections overly cautious, we would project annual shortfalls of Proposition 56 revenue for Medi‑Cal compared to Proposition 56 costs in Medi‑Cal. Balances in the Proposition 56 fund account could cover these annual shortfalls, but likely only on a temporary basis, after which General Fund could be needed. We would note that certain new proposed supplemental payments are potentially over‑budgeted since the federal share of cost for these is set to 50 percent, which is lower than the state’s “effective” federal share of cost. (The state’s effective share of cost takes into account enhanced federal financial participation for certain Medi‑Cal populations and services.)

Existing Provider Payment Increases Should Be Further Assessed

As previously mentioned, when the 2017‑18 agreement was reached on the use of Proposition 56 funding to support provider payment increases, the administration stated an intent to evaluate the provider payment increases’ impact on access to care. To date, no analysis has been released showing that the existing Proposition 56 provider payment increases have had an effect on access to quality care in Medi‑Cal.

Extending Provider Payment Increases for a Limited Term Would Provide an Opportunity to Assess Their Impact. Given implementation challenges and delays, and potential lags in providers’ behavioral responses to the higher payments, it is unlikely that any information provided by the administration at this time would be able to definitively show an effect of the existing payment increases on access and quality. Accordingly, more time and experience under the existing provider payment increases would be needed to assess their effectiveness. Keeping the provider payment increases limited term, preferably for a couple of years, would provide an opportunity to assess their impact. A multiple‑year extension would allow providers’ medium‑ to longer‑term behavioral responses to the higher payments to be more properly evaluated.

Additional Public Deliberation About How Proposition 56 Funding Is Used to Improve Access and Quality Could Be Worthwhile. The structure of the existing provider payment increases was developed relatively quickly to facilitate relatively fast implementation (the structure brings other benefits as well). While there was robust public deliberation over whether to use Proposition 56 funding to augment provider payments to improve access to quality care, there was less public deliberation around how to best use the funding for this purpose. Although we raise design questions, particularly around how the existing physician supplemental payment structure works within Medi‑Cal managed care, we have not comprehensively evaluated the trade‑offs of alternative approaches, such as raising select Medi‑Cal FFS rates or providing incentive payments based on the achievement of outcomes. Further public deliberation over how to best target funding for provider payment increases to improve access and quality would provide an opportunity to better understand the trade‑offs of the various alternative approaches.

Value‑Based Payments Intriguing . . .

Value‑Based Payments May Have Potential to Drive Access and Quality Improvements. The administration’s proposal to create a value‑based payment program using Proposition 56 funding represents an intriguing approach to paying for desired improvements in care. The areas targeted with these supplemental payments—chronic disease management, prepartum and postpartum care, and behavioral and physical health coordination—are areas with opportunities for improvement that could positively impact the overall Medi‑Cal system’s fiscal performance and care outcomes. Moreover, paying for specific desired outcomes, compared to paying higher amounts for the rendering of certain services, brings promise in terms of driving tangible program improvements.