LAO Contact

Correction (3/6/19): Safety net and crisis home capacity numbers have been updated in Figure 4.

February 25, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of the Department of Developmental Services Budget

Executive Summary

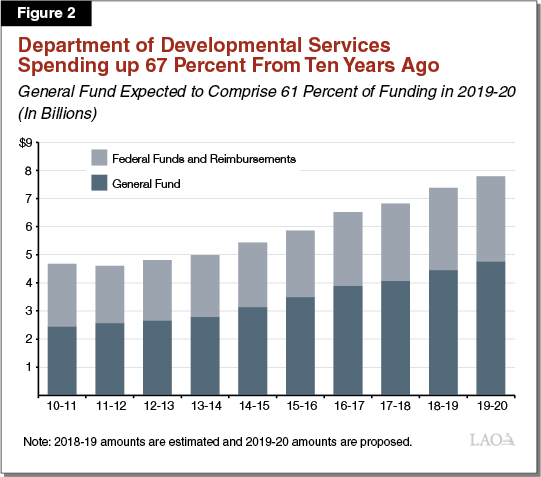

The Governor’s budget proposes $7.8 billion in spending for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) in 2019‑20, with $4.8 billion from the General Fund. Compared to estimated 2018‑19 expenditures, this marks an increase of $435 million (5.9 percent) overall and $332 million (7.5 percent) in General Fund spending.

Caseload Growth and Costs of Covering State Minimum Wage Increases Drive Year‑Over‑Year Increases in Budget. DDS expects to serve 350,000 consumers in 2019‑20, 16,500 more than in 2018‑19. (“Consumers” is the term used in statute for the individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities receiving DDS services.) These new consumers, along with changes in consumers’ mix of services, account for about $303 million of the General Fund growth. The cost to cover the 2019 and scheduled 2020 increases in the state minimum wage among service providers’ staff accounts for about $80 million of General Fund growth. Increased spending is partially offset by decreased spending on Developmental Centers (DCs) of $41 million General Fund.

General Treatment DCs on Track to Close in 2019; Future of Properties Unclear. DDS moved the final residents from Sonoma DC in 2018 and plans to move the final residents of Fairview DC and the general treatment area of Porterville DC by the end of 2019. The administration has not provided many details about its plans for the future of these state‑owned properties after final closures. We suggest the Legislature request additional details from DDS at budget hearings to inform any legislative decisions about these properties.

Proposed Reorganization of DDS Better Reflects Its Responsibilities; Opportunities for Further Reform Should Be Considered. Although DDS has requested a relatively small dollar amount and staffing augmentation—$8.1 million ($6.5 million General Fund) ongoing and 54 permanent positions—its proposal to reorganize the department represents a shift in thinking. Currently, the department reflects two systems of service delivery—one community‑based and one DC‑based. The new structure would consolidate all consumer services under one “Program Services” umbrella and all administrative, legal, and clients’ rights functions under a second “Operations” umbrella. Among other things, the proposal would enhance quality assurance, risk management, and fiscal accountability, and ramp up state oversight of Regional Centers (RCs), which coordinate services for consumers. This may be a good time to consider additional reform opportunities to improve DDS’ operations and program delivery to consumers over the longer term. We recommend the Legislature request information from DDS at budget hearings about:

- DDS’ short‑ and long‑term goals, particularly from a consumer perspective, and how this reorganization will facilitate meeting these goals.

- How DDS would consolidate data and information collected and reported by various units throughout the department to think strategically about the future and how DDS could more systematically collect data generally.

Better Quantifiable Information Needed About Demand for Crisis and Safety Net Services. For consumers with complex behavioral needs or who are at risk of, or currently in, crisis, DDS, together with RCs, has been developing a variety of community‑based resources to serve as a safety net for these consumers when regular homes and/or services cannot meet their needs. DDS requests $21 million ($20.8 million General Fund) to increase the number of safety net homes and crisis services. The proposal includes expanding the safety net to the Central Valley, as well as to children and adolescents. While there is likely need for additional safety net services to justify a budget augmentation for this purpose, we note there is a lack of data to comprehensively assess the demand for these services. Beyond the current proposal, we recommend the Legislature require DDS to submit a revised safety net plan with the 2020‑21 budget proposal that provides more detailed information on the determination of future safety net expansion, based on information about consumer needs and demand.

Other 2019‑20 Budget Issues for Legislative Consideration. Below, we highlight additional key issues raised in the 2019‑20 budget proposal for DDS.

- Proposed Federal Claims Reimbursement Information Technology (IT) System. The Governor’s budget proposes $3.2 million ($3 million General Fund) in 2019‑20 and $12 million ($11.8 million) in each of 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 for a new IT system that would allow DDS to more efficiently submit claims to the federal government to ensure receipt of federal funding for Medicaid‑eligible services. For 2019‑20, we recommend approving only the requested planning funds ($3.2 million), while deferring consideration of the requested design, development, and implementation funds ($24 million in total) until 2020‑21. Since an external contract with a consultant for these purposes will not be awarded until fall of 2020, this will give the department more time to refine its estimates of total project cost.

- Minimum Wage Issues. We recommend the Legislature revisit a rate adjustment quirk that disallows service providers in areas with local minimum wages that are higher than the state minimum wage from applying for rate adjustments the state provides for increases in state minimum wage.

- Uniform Holiday Schedule. The budget proposes enforcement of the “14‑day uniform holiday schedule,” which prohibits service providers from billing for services on 14 set days per year and was originally enacted as a cost‑savings measure during the recession. If the Legislature agrees that the state should mandate a holiday schedule among service providers, it might instead consider a 10‑ or 11‑day schedule that is more in line with state and federal government practices.

Existing Rate‑Setting Processes Are Overly Complex. The current system for setting service provider rates in the DDS system is complex due to the numerous statutorily defined methods for setting rates and the number of service codes to which rates are applied. Some of the rate‑setting methods have not actually been used for more than a decade due to recessionary budget solutions, and many of the service codes are used inconsistently across the 21 RCs.

Forthcoming Rate Study Report Will Help Inform Rate Reform in the Long‑Run; Legislature May Also Wish to Consider Actions for 2019‑20. In 2016, the Legislature approved $3 million General Fund for DDS to conduct a study of service provider rates and the rate‑setting process. The resulting report is scheduled to be released to the Legislature on March 1. We provide some background information and a framework to guide the Legislature’s evaluation of the rate study and subsequent action. The timing of the release of the rate study likely does not allow the Legislature enough time to fully consider the study and enact comprehensive rate reform before enacting the 2019‑20 budget. Therefore, the Legislature might take actions for the near term that provide some degree of fiscal relief for service providers. We provide some potential actions in this regard.

Background

Lanterman Act Lays Foundation for Statutory “Entitlement.” California’s Lanterman Act was passed in 1969 and amounts to a statutory entitlement to services and supports for individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities. Qualifying disabilities include autism, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities (such as a traumatic brain injury) that require similar treatment. The disability must be substantial, lifelong, and start before the age of 18. By passing the Lanterman Act and subsequent legislation, the state has committed itself to providing the services and supports that all qualifying “consumers” (the term used in statute) need and prefer to live in the least restrictive environments possible. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria. (Such criteria are common with most public health and human services programs.)

Nearly All Consumers Receive Services in Community Settings. The Department of Developmental Services (DDS) oversees the provision of services and supports, which are coordinated by 21 nonprofit Regional Center (RC) agencies. Nearly all 333,000 consumers receive these services in community settings, rather than in institutions.

RCs Coordinate Community‑Based Services From Thousands of “Vendors.” RCs have service coordinators who are the consumers’ case managers. They coordinate consumers’ services and supports, which are provided by more than 40,000 vendors across the state and include residential, day program, employment, transportation, and respite services. Using state and federal funding from DDS, RCs pay vendors using what is called their “purchase of service” (POS) budgets. Vendors’ payment rates are set in numerous ways, which will be discussed in the “Rate Reform” section of this report, and have been largely frozen since at least 2008 (aside from one increase in 2016 and a series of recent increases to account for rising state minimum wages). RCs cannot use POS funding to purchase services until all sources of other available funding have been exhausted, such as private health insurance or Medi‑Cal (the state’s Medicaid program).

DDS Closing Remaining Institutions. While DDS operated as many as seven large institutions called Developmental Centers (DCs) in the past, the administration and the Legislature made the decision in 2015 to close the three remaining DCs. DDS closed one DC in December 2018 and expects to close the other two, which currently serve fewer than a total of 150 consumers, by December 2019.

DDS Will Still Operate Two Large Facilities . . . DDS will continue to indefinitely operate the secure treatment program at Porterville DC, which serves up to 211 individuals with developmental disabilities who have been committed by a court because they are a safety risk to themselves or others and/or have been deemed incompetent to stand trial for an alleged criminal offense. DDS will also continue to operate Canyon Springs Community Facility, which serves a maximum of 63 consumers who typically need transitional services, such as when they are moving from the secure treatment program at Porterville DC, but before they are ready for a permanent residence. (Legislation passed in 2018 dedicates 10 of the 63 slots to consumers in crisis.)

. . . And Provide Some Community‑Based Safety Net Services Directly. In addition, DDS operates certain “safety net” services—using state staff—in community settings for consumers in crisis. (The systemwide safety net plan also includes some vendor‑operated services.) The DDS‑operated safety net system includes two mobile crisis teams (one in Northern California and one in Southern California), which currently accept referrals from five of 21 RCs, as well as two acute crisis facilities, which each can house five consumers. By the end of 2019, DDS expects to have a total of five acute crisis homes (with 24 total beds) up and running. Because vendors cannot be required to serve a consumer, having some services run by DDS state staff essentially provides a “last resort” option for consumers with especially challenging needs.

Service Delivery Continues to Evolve, Providing Consumers With Increased Independence. Service delivery methods and models continue to evolve as consumers are given more independence and freedom of choice in a system that is nearly 100 percent community‑based. For example, new federal rules that will take effect in March 2022 require RCs and vendors to increase consumer integration in the community and enhance consumer choice, including using a “person‑centered planning” process to understand and identify the individual goals, preferences, and needs of each consumer. California’s Employment First law makes competitive (meaning at least minimum wage), integrated employment a top priority for working age consumers. In addition, DDS is about to implement the Self Determination Program, which allows consumers much greater control over their choice of services and service providers and allows them to use independent facilitators to assist in planning. The program is being phased in over the next two‑to‑three years with about 2,500 consumers before being offered to all consumers.

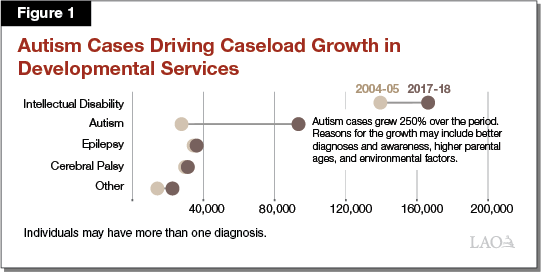

Caseload Continues to Expand and Change. The estimated number of consumers served by DDS—333,000 in 2018‑19—continues to grow rapidly, at an average annual rate of 4.7 percent over the past five years. By contrast, the state’s population has grown by less than 1 percent each year over the same period. Growth in the Early Start program, which serves infants and toddlers under age three, has been especially notable over the past five years, averaging 8.7 percent per year. In addition, over the same five years, the number of consumers with autism has increased an average of 10.1 percent annually. Consumers with autism are now one of every three DDS consumers. Figure 1 shows the rapid growth in autism. The reasons for the increase in autism (which is occurring nationwide) are not entirely understood—research points to better diagnoses, as well as actual increases in autism as a condition. On the latter point, researchers believe that both environmental factors and parental age could be potential causes.

We hear anecdotally that more consumers have dual mental health diagnoses than in the past and that more are involved in the criminal justice system; however, data are unavailable to understand the extent to which these are the case.

The Governor’s Budget Proposal

Overview of Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $7.8 billion (total funds) for DDS in 2019‑20, an increase of 5.9 percent over revised 2018‑19 expenditures. General Fund expenditures comprise $4.8 billion of this amount, a 7.5 percent increase over revised 2018‑19 General Fund spending. Relative to what was assumed in the 2018‑19 Budget Act, revised expenditures for the current year are down $65.5 million in total funds ($55.1 million General Fund). Figure 2 shows recent growth in the DDS budget.

The Governor’s budget includes a net reduction in the number of DDS positions (which include both staff at headquarters and staff operating state‑run homes and facilities) of 631 positions, or 21 percent, from 3,598 to 2,967. While the budget proposes to add 251 positions in 2019‑20—54 at headquarters and 197 at state‑run homes and facilities—these additions are more than offset by a reduction of 882 positions at the DCs that are closing.

Current‑Year Adjustments. Slightly lower spending in 2018‑19 relative to the enacted budget reflects the net effect of several changes, as described below. Caseload is expected to be 356 people higher than in the enacted budget, which partially offsets lower spending.

- POS—Total Decrease of $74.7 Million ($37.1 General Fund). Primary drivers of the change include:

- How Consumers Use Services. Net decrease of $20.4 million ($1.2 million General Fund) due to a shift in the amount and mix of services consumers are expected to use. For example, increased spending on community care facilities, health care, and medical facilities is more than offset by larger decreases in spending on day programs, in‑home respite, employment programs, and transportation. (This net decrease in spending on services largely reflects lower‑than‑expected spending on the January 1, 2018 state minimum wage increase.)

- January 1, 2019 State Minimum Wage Increase. Additional decrease of $54.6 million ($33.1 million General Fund) in the cost to cover the January 1, 2019 state minimum wage increase among vendors’ minimum wage staff. The decreases are based on lower‑than‑expected actual costs associated with the minimum wage increases that took effect on January 1, 2017 and January 1, 2018.

- RC Operations—Total Decrease of $27.7 Million General Fund. The relative cost to the General Fund declined because DDS secured additional federal Medicaid matching funds through the Targeted Case Management program (which helps pay for RC case management for Medicaid‑eligible consumers).

- State‑Run Services—Net Increase of $9.8 Million ($7.5 Million General Fund). The current‑year budget for state‑run services reflects the rising cost of employee compensation and retirement due to revised collective bargaining agreements, partially offset by reduced operating costs from moving 20 DC residents to the community earlier than expected.

Budget‑Year Changes. Increased spending of $435.2 million ($332.4 million General Fund) in 2019‑20 relative to revised current‑year estimates is largely a result of caseload growth and costs to cover 2019 and scheduled 2020 minimum wage increases among vendors’ lowest wage staff, offset to some degree by reductions in the cost to operate DCs.

- POS—Net Increase of $506.2 Million ($362.3 Million General Fund). Major drivers of this change include:

- Caseload Growth and How Consumers Use Services. Increased spending of $370.9 million ($278.5 million General Fund) ongoing to account for an anticipated 16,512 new consumers and the projected mix and amount of services used. Spending is expected to increase for community care facilities, support services, in‑home respite, and day programs. Spending is expected to decline for work activity programs (non‑integrated sub‑minimum wage programs) and increase for individual supported employment (integrated, competitive job programs). The shift from work activity programs to supported employment is what we should expect to see as the system moves into compliance with new federal rules and state rules, which both favor consumer employment in integrated settings.

- 2019 and 2020 State Minimum Wage Increases. Increase of $159 million ($80.1 million General Fund) ongoing to cover vendors’ costs associated with both the 2019 and scheduled 2020 increases in the state minimum wage.

- One‑Time 2018‑19 Expenditures That Are Ending. Decrease of $89.8 million ($53.7 million General Fund) by ending the delay of the “uniform holiday schedule” (discussed later in the report) and one‑time rate increases—“bridge funding”—for vendors in high‑cost areas.

- RC Operations—Net Increase of $43.7 Million ($29 Million General Fund). Major changes include:

- Caseload. Increase of $35 million ($25.2 million General Fund) ongoing for staffing costs associated with growth in caseload.

- New Positions. Increase of $9.3 million ($6.5 million General Fund) ongoing for staff to monitor new housing models ($5.5 million, $3.9 million General Fund) and for additional service coordinator time to work with those consumers who have especially complex needs ($3.8 million, $2.6 million General Fund).

- DC Closure Activities. Reduction of $5.4 million in RC costs associated with moving consumers from the DCs into the community.

- State‑Run Services—Net Decrease of $84.9 Million ($40.8 Million General Fund).

- DC Closures. Year‑over‑year decrease of $105.9 million ($55.6 million General Fund) due to the closure of Sonoma DC in 2018‑19 and the anticipated closures of Fairview DC and the general treatment area at Porterville DC in 2019‑20.

- Safety Net Development. Increase of $11.7 million ($7.3 million General Fund) for the development of additional state‑run crisis and safety net services.

- Deferred Maintenance. Increase of $5 million (all from the General Fund) for deferred maintenance projects at the secure treatment program at Porterville DC.

- Headquarters Changes. Expiration of one‑time costs of $400,000 (for person‑centered planning training) are offset by an increase of $13.9 million ($10.9 million General Fund), as follows:

- Reorganization of DDS. Increase of $8.1 million ($6.5 million General Fund) ongoing to restructure the department, as discussed in the next section.

- Contractor Costs Related to New Federal Rules. One‑time increase of $3 million ($1.8 million General Fund) to hire a contractor to conduct site assessments of vendors as part of coming into compliance with new federal Medicaid rules.

- Information Technology (IT) Project to Improve Federal Claims System. One‑time increases of $3.2 million ($3 million General Fund) in 2019‑20 and $12 million ($11.8 million General Fund) in each of 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 to develop a new IT system to manage claims to receive federal Medicaid reimbursements.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

What follows is a discussion of the Governor’s DDS budget proposals for 2019‑20, including our assessments and recommendations for each. We note that most of the increased spending proposed for DDS is a natural result of caseload growth and reflects the impact of previous policy decisions (primarily scheduled state minimum wage increases). Nevertheless, the proposal to reorganize the department—while expected to cost relatively little—represents a significant shift in how DDS approaches its job.

Department Reorganization Proposal

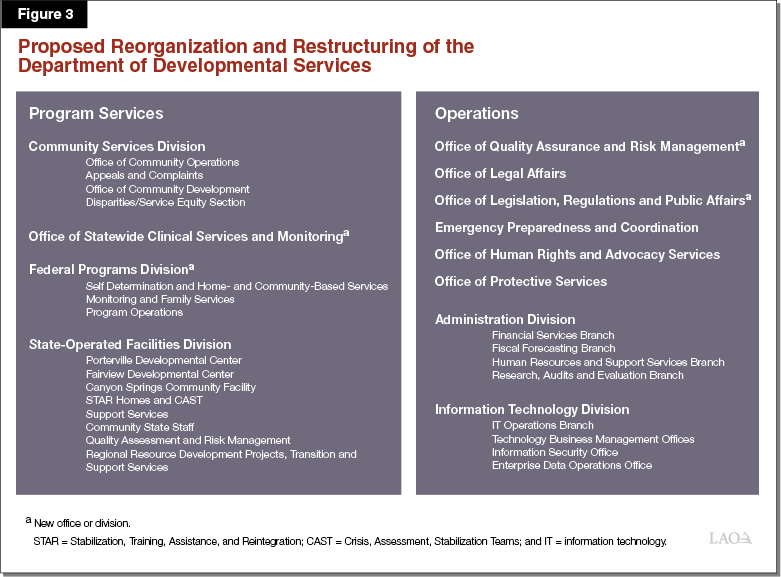

The Governor’s budget proposes $8.1 million ($6.5 million General Fund) and 54 new permanent positions (as well as three‑year, limited‑term funding for three positions related to implementation of new federal rules) to reorganize and restructure DDS to better reflect current models of service delivery and enhance fiscal and programmatic oversight.

Existing Structure Includes Two Separate Divisions for DCs and Community Services, as Well as Various Administrative Functions. Currently, DDS is divided into two main divisions. One handles community services, including oversight of RCs. The other handles DCs and other state‑operated facilities. The DCs division includes the positions that work at the DCs and other state‑operated facilities, providing direct services to consumers or maintaining facilities. At its Sacramento headquarters, DDS also has an administration division, an IT division, and five different offices handling legal affairs, human rights and advocacy, legislation, communications, and emergency preparedness. In addition to the department director, DDS has traditionally had one chief deputy director. Before his departure, Governor Brown appointed a second chief deputy director in December 2018 who will play a key role in the newly proposed departmental structure, overseeing Program Services.

Proposal Consolidates Functions Into Two Main Areas—Program Services and Operations. The current proposal would dissolve the DCs division and reorganize DDS functions (including some of the former DC division’s functions) into two main areas, as described below and depicted in Figure 3, each of which would be overseen by a chief deputy director.

- “Program Services” Would Handle Functions Associated With Consumer Services. Program Services would include the personnel that manage, and activities that concern, all of the services and supports delivered to consumers. This would include divisions for community services, state‑run facilities, and federal programs (a new division). It would also include an office for statewide clinical services and monitoring (a new office).

- “Operations” Would Handle Administrative, Legal, and Clients’ Rights Functions. Operations would cover what could be considered primarily administrative functions for all DDS programs. It would include offices for quality assurance and risk management (a new office), legal affairs, human rights and advocacy, and protective services. It would consolidate several functions into a new office of legislation, regulations, and public affairs. It would include an administration division and a restructured IT division, and it includes emergency preparedness/coordination functions.

Proposal Calls for 54 New Positions. The proposal requests 54 new permanent positions and three positions that would be funded for only three years. Excluding the staff that work on‑site at the DCs and other state‑operated facilities, this proposal would increase the number of positions at DDS by 13 percent (from 415 to 469 positions). Thirty‑seven of the 54 new positions and the three three‑year positions would be in Program Services, while 17 new positions would work in Operations.

Some of the 54 new positions would augment current departmental functions. For example, the proposal calls for four additional staff to monitor and provide oversight of RCs’ Early Start programs for infants and toddlers (please see our forthcoming budget publication, The 2019‑20 Budget: Governor’s Proposals for Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs, for more information). Other positions would perform new functions for DDS. For example, the proposal requests an autism specialist to aid the department in understanding trends and research related to autism and to coordinate with other departments in serving the growing autism caseload. Finally, some positions would extend current oversight of RCs, as discussed below.

Proposal Increases Oversight of RCs . . . Currently, four positions act as liaisons with RCs. This proposal requests 19 additional positions to serve in this capacity. It proposes to create seven “RC Liaison/Monitoring Teams.” Each team would include three people and maintain responsibility for oversight at three RCs. They would respond to complaints; attend RC board meetings and train RC board members; and ensure compliance with statutory, regulatory, and contractual obligations. Although the four current RC liaisons perform some of these functions already, this proposal would allow each team more time per RC. For example, instead of occasionally attending RC board meetings, a liaison would attend every RC board meeting.

. . . Which Includes Opening a New DDS Office in Southern California. Currently, DDS conducts its operations only from its Sacramento headquarters (aside from the state staff employed at DCs and other state‑run facilities). This proposal includes opening a Southern California office (on the Fairview DC property in Costa Mesa in the near term) to house the RC Liaison/Monitoring Teams overseeing Southern California RCs.

LAO Assessment. The cost of the proposal to restructure and reorganize DDS—$8.1 million (total funds)—does not represent a significant dollar amount relative to the total DDS budget. Yet, it does represent a shift in policy and thinking, and it comes at a critical juncture for the DDS system. DDS is in the process of closing its final general treatment DCs, ramping up its new self‑determination program, preparing for possible vendor rate reform, dealing with how to best serve the rapidly growing number of consumers with autism, and preparing for 2022 implementation of the new federal rules.

In general, we find that the restructuring proposal warrants legislative consideration because it more logically reflects DDS’ current responsibilities (and those that are on the horizon) and it attempts to respond to some of its current limitations, such as an inadequate number of staff to conduct timely and comprehensive risk management and quality assurance. It reflects the fact that all but 300 or so consumers will be served in community settings and responds to the new federal rules. It enhances oversight of RCs, which has been needed. For example, Kern RC has been operating under special contract language with DDS since 2015 after numerous complaints about service delays, lack of services, conflicts of interest, fiscal mismanagement, and lack of responsiveness (to consumers and families as well as to Kern County). In addition, Inland RC was also recently on probation, and South Central Los Angeles RC has been put on notice about possible probation.

Still, we note that the proposal misses some opportunities to more fully consider how the system could better deliver services from a consumer perspective. For example, although some changes could have a positive impact on consumers (such as the proposal to increase DDS oversight of RCs, which should lead to more timely response to complaints and reported incidents), it is unclear how the reorganization will lead more directly, and broadly, to improved outcomes for consumers and what specifically those improvements might be.

While the proposal includes increased data analysis and reporting, it does not appear to make significant changes to current data collection methods and types of data available. As we have noted in prior analyses, the current data available about DDS consumers and services are not comprehensive and are not collected in a systematic manner. This, in turn, makes it difficult to understand, in a quantifiable way, unmet service needs across the state, including whether vendors have capacity and whether services are accessible to consumers.

Finally, we note that the proposal includes several positions—such as the autism specialist, several research data specialists, and staff services managers—across various units throughout the department that would handle important functions, such as emerging needs, literature reviews, research, trend analysis, and collaboration with parents and stakeholders to understand consumers’ needs. It is unclear to us, however, whether and how DDS would take disparate pieces of information collected and provided from these various units and use them collectively to strategically plan for the future. For example, would DDS, with information collected by these various positions be in a position to consider questions, such as:

- Is 21 the right number of RCs? And if not, how many should there be?

- Does DDS have the right amount of oversight of RCs?

- Should more of what RCs do be standardized to ensure consumers across the state receive the same level of service and/or should RCs be given more latitude to pursue creative solutions to challenges?

- How should fiscal constraints be reconciled with consumer choice?

- How can self‑determination be used to enhance consumer outcomes? Can it reduce spending at the same time, and by how much?

- What can DDS and RCs do to promote a quality workforce among service providers?

- How should DDS and RCs measure quality in services?

LAO Recommendation. On net, we believe the benefits of this proposal outweigh any downside. As noted earlier, it more accurately reflects DDS’ current system and challenges and is responsive to some of the recent challenges the department has faced when it comes to RC oversight, risk management, and quality assurance. We suggest the Legislature request some of the following information at hearings and/or at May Revision to aid in its evaluation of the proposal, including the Legislature’s decision about whether or not to make any changes to the proposal.

- DDS’ overall near‑term and longer‑term goals, particularly from the consumer perspective, and how the proposed reorganization would help it reach these goals.

- Additional details about how the new Southern California office would operate and how staff in the Sacramento headquarters would maintain oversight of the new office’s functions.

- Additional information about how DDS would consolidate findings from across the multiple units and positions to understand best practices, emerging needs, and trends, and to provide forward‑looking leadership to RCs and vendors about how to best serve consumers.

- DDS’ ideas and possible plans for how to address the data collection issue. For example, we suggest that the Legislature ask DDS to begin thinking about whether current methods could be enhanced or adapted or whether DDS should consider new ways to systematically collect information. The Legislature could consider asking the department to prepare a roadmap to present with its the 2020‑21 budget proposal, for example. Such a plan could consider mechanisms to aggregate and analyze data and information at a statewide level to inform legislative, departmental, and fiscal and policy decision making.

Safety Net Services Expansion Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes to enhance the DDS system of crisis and safety net services at a cost of $21 million ($20.8 million General Fund). Figure 4 shows the current and proposed capacity in safety net and crisis homes. The proposed safety net enhancements include the following components.

- Central Valley Crisis Homes—$4.5 Million ($4.2 Million General Fund). Adding two DDS‑operated crisis homes and 60 state positions in the Central Valley. Each home could serve five consumers. DDS indicates these homes may be located in Porterville on or near the Porterville DC property.

- Central Valley Mobile Crisis Team—$800,000 ($600,000 General Fund) Ongoing. Adding a third DDS‑run mobile crisis team comprised of five state positions. The purpose of the mobile team is to attempt to stabilize consumers in crisis and try to keep them in their homes.

- State Staff for a Crisis Unit in Vacaville—$3.2 Million ($2.6 Million General Fund) Ongoing. Adding 26.5 state positions to staff a third DDS‑operated crisis unit in Vacaville in Northern California that is scheduled to open in the fall of 2019.

- Support Staff for Existing Safety Net Services—$3.2 Million ($2.6 Million General Fund) Ongoing. Adding 9.1 positions to provide oversight and support to DDS‑operated safety net homes and mobile crisis services.

- Crisis Homes for Children—$4.5 Million General Fund. Developing three community crisis homes specifically for children that would be run by vendors. Current crisis homes—which provide temporary stabilization for up to 18 months—are statutorily for adults only. This proposal includes trailer bill language governing the placement of children in these homes.

- Monitoring of Specialized Homes—$5.5 Million ($3.7 Million General Fund) Ongoing. Increasing monitoring of specialized homes by RC staff. Several new and specialized home models have been developed in recent years—adult residential facilities for persons with special health needs, enhanced behavioral supports homes, and community crisis homes. Increased monitoring would not only help ensure consumer safety, but it would also help ensure that DDS continues to collect federal funding (through reimbursements) by staying in compliance with federal Medicaid rules.

- Lowering Caseload Ratios for Consumers With Complex Needs—$3.8 Million ($2.6 Million General Fund) Ongoing. Adding RC service coordinator positions and establishing a lower 1‑to‑25 service coordinator‑to‑consumer caseload ratio for consumers with complex needs. Under current law, there are several service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratios with which RCs must comply, such as 1‑to‑62 for consumers receiving Medicaid waiver funding. DDS estimates this proposal would allow for intensive service coordination for about 1,200 consumers at any one time. The intensive service coordination would be provided on a temporary basis until a consumer is stabilized, after which he or she would resume working with his or her regular service coordinator.

Figure 4

Safety Net and Crisis Home Capacity

For Individuals With Developmental Disabilities

|

Consumer Need |

Operated by |

Already Open |

In Development |

Proposed in 2019‑20 |

Total When Completea |

|||||||

|

Homes |

Beds |

Homes |

Beds |

Homes |

Beds |

Homes |

Beds |

|||||

|

Adult |

||||||||||||

|

Needs intensive behavioral supports |

Vendor |

18 |

66 |

39 |

141 |

— |

— |

57 |

207 |

|||

|

In crisis |

Vendor |

4 |

16 |

13 |

54 |

— |

— |

17 |

70 |

|||

|

DDS |

3b |

20b |

4 |

20 |

2 |

10 |

7c |

40c |

||||

|

Transitioning from PDC‑STP |

Vendor |

— |

— |

3 |

12 |

— |

— |

3 |

12 |

|||

|

Transitioning from IMD |

Vendor |

— |

— |

4 |

16 |

— |

— |

4 |

16 |

|||

|

Child/Adolescent |

||||||||||||

|

Needs intensive behavioral supports |

Vendor |

2 |

6 |

5 |

19 |

— |

— |

7 |

25 |

|||

|

In crisis |

Vendor |

— |

— |

— |

— |

3 |

12 |

3 |

12 |

|||

|

DDS |

— |

— |

1 |

4 |

— |

— |

1 |

4 |

||||

|

Totals |

27 |

108 |

69 |

266 |

5 |

22 |

99 |

386 |

||||

|

aThere are six additional homes with 34 total beds for which it is unclear the target population. bTwo of the three crisis facilities currently run by DDS are based at developmental centers and will be replaced by homes currently in development. The third refers to the ten beds available at Canyon Springs Community Facility. cPer 2018 statute, DDS now dedicates ten of Canyon Springs Community Facility’s 63 beds for crisis services. PDC‑STP = Porterville Developmental Center‑Secure Treatment Program; IMD = Institution for Mental Disease; and DDS = Department of Developmental Services. |

||||||||||||

LAO Assessment. It is difficult to assess the current plan to expand safety net services because the department lacks good recent data and statistics about demand for such services, including information about where demand is most critical and what types of services are needed most. DDS relies primarily on qualitative information it has collected through its work with the Developmental Services Taskforce (specifically the Workgroup on Community Supports and Safety Net Services)—a group of RC, advocate, family member, and consumer representatives—and through stakeholder meetings held in 2018 in Napa, Visalia, and Pomona. These conversations and meetings have revealed important information about the need for safety net resources and well‑trained, responsive service providers who can intervene when a consumer is about to be in, or is in, a crisis. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to know whether the current number and proposed network of supports is adequate, more than adequate, or not adequate. It is also difficult to understand how the department makes its decisions about the number of homes to build, how to ramp up services, and when to ramp up services.

Regarding the proposed placement of new crisis homes in Porterville, we have concerns about placing a statewide resource in such a remote location, although we recognize the benefits of this location due to the current availability of well‑trained staff (because of the closure of the general treatment area at Porterville DC) and proximity to the secure treatment program at Porterville DC (which could act as back‑up). Very few community‑based consumers live near Porterville and we have concerns about hiring and retaining quality staff at this location in the future. Although Porterville College currently offers degrees and certificates in relevant fields—psychiatric technology and registered nursing—many of the program’s graduates end up working for the Department of State Hospitals or the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; it is unclear how many of those graduates would stay and work for DDS in the Porterville area.

Regarding the proposed additional monitoring of specialized homes by RC staff, we recognize the importance of this function, both in terms of ensuring quality services for consumers as well as ensuring continued receipt of federal funding when applicable.

Regarding the proposed caseload ratio of 1 service coordinator to 25 consumers with complex needs, we note that the proposal only partially addresses other RC caseload ratios that are often out of compliance with state statute and agreements with the federal government. The department was unable to provide the most recent caseload ratio data, but as of March 2017, only 1 of 21 RCs was in compliance with all of the various caseload ratio requirements. Although the current proposal may shift some of the complex cases off regular service coordinator caseloads, and importantly targets resources at the consumers with the most challenging, time‑consuming, and complicated needs, it most likely does not go far enough to improve regular caseload ratios. We raise concerns that the other consumers lack the time and attention of service coordinators to receive the support they need and that is stipulated in statute.

LAO Recommendation. On the Governor’s budget proposal, it is likely that additional safety net resources are needed in the DDS community for consumers with complex behavioral needs and for consumers in crisis to justify a budget augmentation for this purpose. However, whether the specific number of resources proposed by DDS is the right number for near‑term demand is less clear given the lack of back‑up data in the proposal providing a comprehensive assessment of consumer demand and service gaps. We recommend approval of the proposals to increase monitoring of specialized homes and to lower caseload ratios for consumers with specialized needs. We recommend considering other locations in the Central Valley besides Porterville for the new state‑run crisis homes, keeping consumer convenience, future demand, and future availability of quality workforce in mind.

Regarding future planning for crisis and safety net needs, we recommend the Legislature require DDS revise its overall safety net plan (the first version was released in May 2017) and include more quantifiable information about the use of and demand for crisis and safety net services, including information about what DDS and RCs are each doing specifically to prevent potential crises from escalating to the point of needing state‑run services or out‑of‑home placement. We suggest DDS be required to submit a revised plan with the 2020‑21 Governor’s budget proposal that would include information about how DDS will determine when a new home or service is needed. This plan could include information about how DDS would answer some of the following questions—even if it does not have all of the answers ready by next January:

- Do consumers need more support in their homes? What would this look like?

- Do consumers need more temporary crisis homes? If so, what additional capacity is needed, and where?

- Are most crises behavioral? What types of interventions have been successful in preventing potential crises from escalating?

- Do consumers need additional ongoing mental health services or behavioral supports? In what form?

- Do families need more training on how to handle crises and access available resources?

- What markers indicate that crises could develop? Are there things that could be done or training programs that could be developed and implemented to identify these markers and provide the necessary supports to prevent crises from occurring?

Caseload Projections

Caseload remains a major driver of year‑over‑year cost increases. DDS projects an increase of 16,512 consumers in its community programs, growing 5 percent from an estimated 333,094 in 2018‑19 to a projected 349,606 in 2019‑20. DDS also expects the population at DCs to decline to 323 consumers by July 1, 2019. Although the DDS population is growing much more rapidly than overall state population growth (particularly in the Early Start program and in cases of autism), caseload estimates reflect recent historical trends and align with projections our office made. We will examine caseload estimates again in May.

Minimum Wage Issues

State Minimum Wage Increases. The Legislature has increased the state minimum wage several times over the past decade. Currently, the state minimum wage is $11 per hour for businesses with 25 or fewer employees and $12 per hour for businesses with 26 or more employees. The state minimum wage is statutorily scheduled to increase each year until it reaches $15 per hour—in 2022 for the larger businesses and in 2023 for the smaller businesses. Currently, statute allows DDS to adjust the rates paid to vendors when the adjustment is needed to bring their lowest wage staff up to the state minimum wage.

Some Local Jurisdictions Also Have Minimum Wages. Some cities and counties have enacted minimum wages that exceed the state’s minimum wage. Currently, more than 20 cities—and all of Los Angeles County—have local minimum wages that exceed the state’s. In 14 San Francisco Bay Area cities, the local minimum wage is already at or above $15 per hour. Nearly 40 percent of the state’s population lives in areas with these higher local minimum wages. In these areas, DDS vendors must pay at least the local minimum wage. These vendors must do so, however, without any adjustment to their rate because statute generally does not provide for vendor rate adjustments in response to local minimum wage increases. To cover the cost of their minimum wage staff, vendors must make adjustments to absorb the cost, such as reducing administrative costs, staff, or program offerings. In some cases, they may shut down.

Downward Revision to Cost Estimates Associated With State Minimum Wage Increases. In each of the past two January budget proposals, DDS has had to revise downward the current‑year POS estimates, in part because the actual prior‑year costs to cover state minimum wage increases had come in lower than expected. For example, in the current budget proposal, DDS has revised downward—by $144.2 million ($81.9 million General Fund)—its previously estimated costs in 2018‑19 associated with the January 1, 2018 and January 1, 2019 minimum wage increases, based on actual expenditures from 2017‑18.

The Way DDS Has Interpreted Statute Has Perhaps Led to Unintended Consequences, Namely a Rate Adjustment Quirk. While it is not certain, the downward revision in minimum wage‑related spending is likely due in large part to a quirk in the implementation of the statutory policy that guides rate adjustments. Specifically, vendors in areas with a local minimum wage that is higher than the state minimum wage are unable to benefit from the rate adjustments for state minimum wage increases that vendors in lower‑cost areas benefit from. Vendors in jurisdictions with a higher local minimum wage are therefore both (1) ineligible for rate adjustments due to local minimum wage increases, and (2) also considered ineligible for any of the rate adjustments due to state minimum wage increases. They are considered ineligible for the state increases because they already pay their minimum wage workers a wage that is higher than the state minimum wage (even though they received no rate adjustment to pay these higher wages). In contrast, vendors providing the same service in another part of the state, but who are not subject to a local minimum wage requirement, can seek an adjustment per state policy for their minimum wage workers.

To see how this plays out, consider a vendor in San Francisco (which has had a local minimum wage above the state minimum wage since 2014). This vendor cannot request an adjustment to cover the local minimum wage costs. It also cannot seek any adjustment when the state minimum wage goes up because it already pays its lowest wage staff more than the state minimum wage. This means it may still operate with the rate it had before 2014, whereas a vendor in Modesto (which does not have a local minimum wage) would have been able to request an adjustment each of the five times the state minimum wage has increased since 2014. Not only does the vendor in San Francisco have to pay higher wages to its minimum wage staff (currently $15 per hour), but it cannot benefit from any of the adjustments, due to changes in state policy, that are afforded vendors in other areas of the state without local minimum wages.

LAO Recommendation. Given the information presented above, the Legislature may wish to clarify what it intended when it authorized DDS vendors to seek rate adjustments. For example, the state minimum wage is scheduled to increase on January 1, 2020, from $12 per hour to $13 per hour for large employers and from $11 per hour to $12 per hour for small employers. Does the Legislature want to allow a vendor in San Francisco paying the local minimum wage of $15 per hour to seek a rate adjustment to account for the $1 increase in the state minimum wage to partially offset its costs, as it allows a vendor in Modesto (paying the state minimum wage) to do? If so, we recommend statutory clean up to clarify that vendors in areas with a local minimum wage that is higher than the state minimum wage can seek an adjustment related specifically to the increase in the state minimum wage. We recommend the Legislature direct DDS to report at budget hearings about the estimated 2019‑20 General Fund cost to allow all vendors in the state to seek an adjustment related to the scheduled January 1, 2020 minimum wage increase.

DC Closures

DCs on Track to Close in 2019. DDS successfully completed the closure of Sonoma DC in December 2018 and expects to have moved the last residents from Fairview DC and the general treatment area of Porterville DC by the end of 2019. Each DC goes through a period of “warm shutdown”—typically about six months—after residents have moved. DDS is still responsible for maintaining and securing the property during warm shutdown, before it has given responsibility for the property over to the Department of General Services (DGS). (Please see our report, Sequestering Savings From the Closure of Developmental Centers, for more information about this process.)

Proposal Omits Details About the Future of DC Properties. The Governor’s budget does not include any information about DDS’s and DGS’s plans for each of the state‑owned DC properties after final closures. Based on conversations with DDS, it is our understanding that DDS will not declare Sonoma DC property surplus (meaning it will not go through the typical DGS process of disposing of state properties) and is working closely with DGS and the local government to determine the future of the property. DDS also indicated that the Fairview DC property would not be declared surplus until at least 2020‑21. The Fairview property also includes two DDS‑run crisis homes, an apartment development called Harbor Village (which includes some residences for DDS consumers), and will include a second apartment development (which will also include some units for DDS consumers). None of these developments or the crisis homes will be affected by the disposition of the property. There are fewer options for the future of the general treatment area at Porterville DC given its less populated location and its shared infrastructure with, and proximity to, the secure treatment program.

LAO Recommendation. The Legislature might wish to weigh in on decisions about these state‑owned properties. We recommend it direct DDS to provide more information at budget hearings on the status of the administration’s decisions about the future of the DC properties so the Legislature can better understand what role it might play.

Proposals to Facilitate Federal Funding

The Governor’s budget includes two proposals that are ultimately related to the department’s ability to claim federal Medicaid waiver reimbursements for community‑based services—such as residential or day program services—provided to Medicaid‑eligible consumers. (Medicaid reimbursements are projected to account for nearly 40 percent of DDS’ funding in 2019‑20.)

Contracting for On‑Site Vendors Assessments. The first proposal concerns the state’s plan for coming into compliance by 2022 with the new federal rules discussed earlier. These rules are associated with the state’s ability to receive federal funding through the Home‑ and Community‑Based Services Medicaid Waiver. These rules affect DDS as well as other state departments, including the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and Department of Social Services (DSS). As part of California’s federally approved Statewide Transition Plan (the state’s plan for how it will comply with the new federal rules), DDS must facilitate self‑assessments by vendors. This requires vendors to respond to questions about their current service delivery models, service settings, and staffing, for example, to help DDS determine what changes need to be made, if any, to help the vendor come into compliance with the federal rules. A second step involves taking a random sample of vendors and conducting an on‑site assessment to validate information provided in the survey. The Governor’s budget requests $3 million ($1.8 million General Fund) in one‑time funds for DDS to work with a contractor to conduct approximately 1,100 on‑site assessments.

LAO Assessment and Recommendation. DDS must complete the assessments to comply with the federally approved transition plan, and ultimately to draw down a significant amount of federal funding by complying with the new federal rules. DDS based the cost of these on‑site assessments on a contract DHCS has with a contractor for review of DHCS service providers. For these reasons, we do not have concerns with DDS’s request and recommend its approval.

IT Proposal—Federal Claims Reimbursement System Project. The Governor’s budget requests $3.2 million ($3 million General Fund) in 2019‑20 and $12 million ($11.8 million General Fund) in each of 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 to complete development of a new IT system to help DDS process and claim federal reimbursements for its Medicaid waiver‑eligible services. The 2019‑20 amount would pay for planning costs, while the subsequent two years of funding would pay for design, development, and implementation of the IT project. The current “legacy” IT system used to claim federal reimbursements began to be implemented 36 years ago and is not meeting the current programmatic needs of the department. (For example, DDS estimates it forgoes roughly $13.7 million in federal reimbursements each year because of the delays and manual intervention needed to use the legacy system.) DDS is working with the California Department of Technology (CDT) and using its four‑stage planning and approval process for IT project proposals.

LAO Assessment and Recommendation. Although we agree DDS should modernize its federal claims reimbursement system (especially given that federal reimbursements currently account for $2.8 billion in annual DDS funding and given the annual amount DDS estimates it cannot currently claim), it is unclear to us that DDS needs to request the full three‑year amount of funding in 2019‑20. Departments should complete all four stages of CDT’s IT project proposal planning and approval process before the fiscal year in which they are requesting design, development, and implementation funds. This allows the department to solicit bids from external consultants and provide the Legislature with more precise estimates of total project cost, schedule, and scope before the Legislature approves project funding. DDS is only in stage 3 of the process and claims that waiting to seek the remaining funding until after stage 4 is complete would delay the project by a year. We disagree. DDS does not plan to award a contract to an external consultant until the fall of 2020, and could request funding in next year’s budget process. By waiting to approve the remaining funding, the Legislature would have additional cost, schedule, and scope information from stages 3 and 4 (if completed). Even if DDS has not received bids from external consultants by the time it must submit its 2020‑21 budget request, we believe the department could still provide more refined information to the Legislature based on what it learned in 2019. We therefore recommend approving only DDS’ request for $3.2 million ($3 million General Fund) in planning dollars for 2019‑20 and rejecting the current request for design, development, and implementation funding in both 2020‑21 and 2021‑22.

Reinstatement of Uniform Holiday Schedule

As part of a package of budget solutions passed in 2009 in response to the significant state budget deficit, the state enacted a policy prohibiting RCs from paying service providers on 14 set holidays per year. This meant that service providers either did not provide services on those days or absorbed the cost without payment. The policy also required that the 14 holidays be uniform statewide (in other words, it could not be any 14 days throughout the year). This was called the uniform holiday schedule. This policy has not been enforced since 2015 (as a result of litigation, since resolved). Last year, the Governor’s budget proposed beginning enforcement again in 2018‑19, but a compromise reached with the Legislature delayed enforcement until 2019‑20.

LAO Assessment. DDS estimates that enforcing this policy could save $47.8 million ($28.7 million General Fund) annually. Typically, most RCs and vendors observe a certain number of holidays each year regardless of state policy—often about ten days—so it is our understanding the estimate is based on the savings that would occur from observing about four additional days. We note that currently, California state government observes 11 holidays each year and the federal government observes 10. The 14‑day schedule would therefore exceed both state and federal government practices. One option is to statutorily establish a 10‑ or 11‑day schedule, rather than 14. This would not result in the savings estimated by the administration, however. Whether the schedule should be uniform is another question. On the one hand, it ensures that services are up and running on the same days facilitating coordination between, for example, transportation and day program providers. On the other hand, consumers may have particular needs on certain holidays—for example they may need day program job support on the day after Thanksgiving if they work in retail. We believe that it would be reasonable for the Legislature to revisit the entire uniform holiday policy, which was part of a package of recessionary budget solutions, given the state’s improved fiscal condition and the policy’s potential negative ramifications on consumers.

Rate Reform

On March 1, 2019, DDS will release the results of a three‑year study of the DDS rate structure and rate‑setting processes. (Rates refer to the amounts paid to vendors for the services they provide to consumers. For example, vendors’ rates may be a set monthly amount or a set hourly amount and may vary based on the consumers’ level of need.) Chapter 3 of 2016 (AB X2 1, Thurmond), called for the study. DDS was provided $3 million from the General Fund to hire a contractor to conduct the study. In anticipation of the release of the findings and recommendations from the rate study, we have compiled some background information and issues for the Legislature to consider when the study is released. First, we describe the various current methods for setting rates and how this already inherently complex process was made even more complex by budget solutions and subsequent selective funding restorations. Next, we discuss the rate study and the method the contractor used to conduct the rate study and develop rate‑setting models. We then identify previous attempts to reform the rate‑setting process. Finally, we offer some issues the Legislature may wish to consider after it receives the rate study in March.

Current Rate‑Setting Process

Rate Setting Is Inherently Complex. There are any number of ways that vendors’ rates are set in the DDS system, as described below, making for an intrinsically complex system. In addition, services are billed according to a system of more than 150 codes; service providers are “vendorized” to provide services under a given code or codes. Based on conversations with RCs and service providers, it is our understanding that these codes are not necessarily used consistently across the state and that despite the sheer number, these codes can often be inflexible when a service provider tries to meet the unique needs of an individual. Rates are primarily set in the following various ways:

- Statute Sets Certain Rates. Rates for supported employment and work activity programs are set in statute.

- DDS Sets Some Rates. Some vendor rates are set by DDS. For example, DDS provides rate schedules for community care facilities and day programs, including Early Start for infants and toddlers with developmental delays.

- Some Rates Reflect Medi‑Cal Rates. When an RC pays for a service that is otherwise covered by Medi‑Cal (but the consumer is ineligible for Medi‑Cal or has exhausted his or her Medi‑Cal benefits), the RC can pay no more than the Medi‑Cal rate. For example, RCs pay no more than the Medi‑Cal rates for dentistry, physical therapy, and registered nurse care.

- Certain Rates Reflect Rates Set by DSS. When a provider, such as an out‑of‑home respite provider, has a rate established by DSS, RCs also pay that rate.

- Some Vendors Receive Their “Usual and Customary” Rate. RCs purchase some services that are also provided to the wider population. In these cases, RCs may pay the same rate the business charges the general public. These services include sports clubs, diaper service, taxi cabs, and translators.

- Some Transportation Rates Are Based on RC Mileage Reimbursement. Certain transportation services, such as transportation provided by a family member, are reimbursed at the same rates that RCs reimburse their own employees for travel.

- RCs and Vendors Negotiate Certain Rates. If none of the methods for establishing a rate described above apply, an RC and a vendor can negotiate that vendor’s rate.

- New Specialized Homes Receive Different Rates. When DDS began developing specialized homes for consumers with complex needs,such as those transitioning from DCs to the community, statute allowed DDS, RCs, and residential care vendors to negotiate rates to respond to the complex needs of these consumers.

Budget Solutions Fundamentally Changed Key Rate‑Setting Processes. While numerous targeted budget solutions stemmed growth in the DDS budget during the recent economic downturns, they also fundamentally changed the way rates are set and managed on an ongoing basis. The methods described above in essence do not apply any longer, except for those set by other departments or those that are usual and customary. Three key sets of budget solutions include the following:

- Rate Freezes. A variety of services have had their rates frozen for many years, including day programs and in‑home respite since 2003‑04 and most other services since 2008‑09. Whereas there was a process in the past for adjusting rates as vendors’ costs increased, that process no longer applies.

- Median Rates. Since 2008‑09, statute has required new vendors of certain services (whose rates were negotiated with RCs in the past) to accept either the state median rate for that service or their vendorizing RC’s median rate for that service—whichever is lower.

- Cost Statements. Vendors used to submit cost statements every two years, which were an accounting of expenses and staffing costs. These were used to adjust rates and rate schedules as the cost of doing business increased. Since the recession, vendors have no longer had to submit these cost statements because rates have been frozen.

Funding Restorations/Augmentations Have Occurred on a Piecemeal Basis. Some recent budget‑related actions have increased vendor rates, without reinstating the pre‑recession rate‑setting and rate‑adjustment processes. In addition, the state has provided funding specifically to cover some vendors’ costs associated with increases in the state minimum wage. Below are some examples of these actions.

- 2016 Special Session Legislation Increased Vendor Rates . . . Chapter 3 provided a fixed ongoing allocation of $179.4 million from the General Fund for vendors to increase the salaries and benefits of their employees who spend at least 75 percent of their time providing direct service to consumers.

- . . . But Implementation of the Rate Increase Was Complicated. DDS conducted a survey of vendors to determine how much to increase the rates across the many types of service providers (because it was a fixed allocation). It then developed a percentage rate increase for each service type. In 2017, vendors that received a rate increase were required to submit documentation as to how they were spending the increased funds. All vendors of the same type of service received the same percentage rate increase. In other words, the increase did not reflect vendors’ individual costs.

- 2018‑19 Budget Included Another Targeted Rate Increase. The 2018‑19 Budget Act provided $25 million one time from the General Fund for vendor bridge funding. The funding is only for providers in high‑cost areas of the state and, as implemented, only applies to community care facilities and day programs.

- Minimum Wage‑Related Adjustments Provided Since 2016. Chapter 351 of 2013 (AB 10, Alejo), and Chapter 4 of 2016 (SB 3, Leno), scheduled state minimum wage increases, beginning in 2014. With each new increase in the state minimum wage, only certain vendors are able to apply for rate adjustments to cover their associated increased costs (based on DDS’ interpretation of this statute, discussed earlier).

Rate Study

Statute Requires the Rate Study to Consider Several Issues. Per statute, the rate study is to address the “sustainability, quality, and transparency” of services in the DDS system and:

- Assess whether current rate‑setting methods are effective, based on:

- Whether the current methods result in an adequate number of vendors in each service category.

- How the fiscal effects of alternative methods for each service category compare.

- How different methods can positively affect consumer outcomes.

- Evaluate and make recommendations to simplify the service code structure.

Certain rates are not under consideration in the study. Primarily, this includes those rates that are out of DDS’ control, such as rates based on Medi‑Cal or DSS rates and usual and customary rates paid to vendors who serve the wider general population.

DDS Selected an Experienced Contractor to Conduct the Study. DDS solicited proposals and awarded the contract to conduct the rate study to Burns & Associates, health policy consultants based in Phoenix, Arizona. The company has worked with a number of other states to evaluate rate setting in their developmental services systems, including Arizona, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Virginia. To assess the rate‑setting process in the DDS system and develop rate‑setting models and other recommendations, Burns & Associates conducted the activities discussed below.

The Rate Study Included an In‑Depth Survey of Vendor Costs . . . Burns & Associates conducted a survey of vendors to learn more about how they each conduct business. For example, the survey asked for information about wages and other costs. Importantly, the survey solicited other information as well, since looking at vendors’ costs alone would provide an incomplete picture. This is because vendor costs are a direct function of current rates. In other words, this is not a market‑based system in which vendors can increase their rates as their costs rise; they receive the rates the state offers—which have largely been frozen for more than a decade—and adjust their spending based on those rates. In addition to collecting cost information, the survey also asked detailed questions about the proportion of time staff spend on various types of activities, such as direct care, training or program development, supervision, and professional support. It also asked about turnover rates and the number of training hours an employee spends in the first year and in subsequent years. For administrative staff, it asked about the proportion of time spent on administrative tasks related to DDS requirements versus other types of administrative work, including fundraising.

. . . And a Survey of Parents and Consumers. Statute required DDS to involve stakeholders in the rate study process, which it did. One recommendation from stakeholders, including the Developmental Services Task Force, was to conduct a survey of consumers and family members to understand the vendor rate structure more holistically. On this recommendation, DDS authorized Burns & Associates to subcontract with the Human Services Research Institute to conduct this additional survey. Although the survey is not necessarily representative of the DDS system (in terms of RCs, ages, diagnoses, race/ethnicity, and/or language), DDS and Burns & Associates have indicated that the qualitative information collected has been used to inform the overall study process. Burns & Associates also indicated that this is the first time in their rate development work with states that a survey of consumers and families has been conducted.

Contractor Is Also Using Other Sources of Information to Inform Its Evaluation. Burns & Associates examined information such as wage data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics and mileage rates from the Internal Revenue Service. They also considered the new federal Home‑ and Community‑Based Services waiver rules that will take effect in 2022 as well as federal labor laws.

Previous Rate Studies

The Current Rate Study Is Not the First. Concerns about rate setting, delivery of quality services, insufficient funding, rapid caseload growth, and a desire for increased consumer choice are not new concepts in the history of the DDS system. On several occasions over the past four decades, the Legislature has called for examinations of the system and its network of service providers, with an eye toward upholding the intent of the Lanterman Act and sustaining quality services and choice for consumers. Below are some examples of previous efforts advanced by the Legislature.

- In response to Chapter 692 of 1982 (AB 2775, Torres and Hannigan), the State Council on Developmental Disabilities prepared a report entitled, Report on Quality Assurance in the Delivery of Services to Persons with Developmental Disabilities. It examined quality assurance standards and rates of reimbursement for residential service providers.

- DDS prepared a report in 1997 in response to supplemental report language in the 1996 budget requiring a review of rate setting for residential and day program services.

- The California State Auditor submitted a report in 1999 about insufficient funding in the system based on a survey of service providers and RCs.

- DDS contracted for a report in 2000 in response to Chapter 1043 of 1998 (SB 1038, Thompson) about a proposed residential rate model. Subsequent work about rates for other services did not happen because the state went into a recession.

Results and Recommendations Have Been Addressed in a Piecemeal Fashion. Although the system did move to an Alternative Residential Model rate structure for community care facilities, many of the other recommendations about quality services and rate‑setting reform more generally have not been taken up in whole. In large part, this has been due to budget constraints, as a number of the recommendations would have required significantly more funding in the system.

A Framework for Legislative Action on the Rate Study

Although it is not yet known what will be recommended in the current rate study or how sweeping the reform recommendations might be, we suggest some issues for the Legislature to consider when reviewing the results.

The Opportunity for Real Reform

The statutory requirements of the rate study were not limited to suggesting new rates or rate‑setting models for services. It required an examination of the service code structure, how to set rates in a sustainable way, and how to set rates in a way that would improve outcomes for consumers. The discussions that will be held over the coming months provide an opportunity to review what does not work about the current structure and to identify systemic ways to improve the structure. For example, when rates were frozen and median rates for new providers were instituted, statute provided a process for exceptions—the health and safety waiver process. If a provider’s rate was compromising the health and safety of a consumer, DDS could grant an exception to the rate freeze and increase the vendor’s rate to avoid risk to the consumer. Since that time, the health and safety waiver process has become a challenge in and of itself. Vendors have sought to use it in response to increased local minimum wages and the sheer number of requests has led to long delays in DDS responses.

Issues to Consider in Reading and Evaluating the Rate Study Report

On March 1, the Legislature should receive a report and/or other materials about the final rate study results and recommendations. The study will likely inform the answers to a number of important questions, such as how much should rates be increased and whether the service code structure can be simplified. However, there may be some unanswered questions as well.

First, we suggest the Legislature consider how the study addressed sustainability of rates over time—particularly given the ups and downs in the state fiscal condition—and whether it considers geographic variation in costs and labor market conditions. For example, what considerations does the study make about adjusting rates in recessionary times and containing costs when necessary? Do the recommendations include ways to adjust rates for scheduled increases in the state minimum wage? Does it address local minimum wages?

We also suggest the Legislature consider whether the study offers ideas for how to implement changes, such as ways to phase in rate increases, and whether it recommends approving all changes as a package or offers a menu of options. Does the study offer insights about the changes that would need to be made to the current infrastructure—such as IT changes; billing and claims processes; and communication with RCs, vendors, families, and consumers—to implement the recommended changes?

Finally, we suggest the Legislature consider how the recommendations could lead to improved quality of services for consumers. This may include suggestions for better collection and analyses of data and information about service needs and gaps.

Taking Action for 2019‑20 and the Short Term

Given the timing of the release of the rate study, the Legislature must weigh whether to approve certain changes to the DDS rate structure in the 2019‑20 budget or wait to make any significant changes until further discussions take place. This trade‑off will depend in large part on the nature of the recommendations and whether there are actions that can be taken right away, whether certain recommendations should be phased in or even piloted, or whether all of the recommendations require lengthier consideration.

Providing Vendors Some Fiscal Relief in 2019‑20. The study may offer near‑term recommendations to increase rates. If it does not, the Legislature may wish to consider a select set of ways to increase funding for vendors in 2019‑20 that are not dependent on broader rate reform ultimately enacted in the longer term. For example, as we noted earlier, the Legislature could clarify statute to allow vendors in areas with local minimum wages to access the scheduled January 1, 2020 state minimum wage increases. It could also consider a 10‑ or 11‑day uniform holiday schedule (as discussed earlier), or no set holiday schedule at all.

Taking Action for the Longer Term

We recommend the Legislature ultimately take a number of actions to allow for effective ongoing oversight of implementation of the rate structure and establish processes for rate adjustments and overall continuous improvement to the rate structure.

Instituting a Process for Both Adjusting Rates and Containing Costs. We recommend the Legislature consider how it would like to handle statutorily a process for adjusting rates over time as vendors’ costs of doing business increase. At the same time, it should also consider how to handle statutorily a process for containing costs in the DDS system in tighter fiscal times. In recent experience, the types of budget solutions that have been enacted followed by attempts to restore funding have led to a situation in which the established rate‑setting methods are not used. For example, although there are vendors in certain service categories that have “negotiated rates,” nothing has been truly negotiated in more than ten years since median rates were implemented.

Instituting an Oversight Process. We recommend the Legislature consider a process to regularly track rate‑setting issues with the administration, especially in terms of the impact of the rate structure on consumer outcomes and service gaps. In tandem with our recommendation that the Legislature require DDS to develop a plan for more systematic collection and analysis of data and information of consumers’ services needs and vendor availability and capacity, we suggest the Legislature require regular briefings for legislative staff to include updates on rates, service provider capacity, and consumer outcomes. (Similar quarterly briefings are currently required to inform legislative staff on the status of DC closures and related issues.)

Periodic Formal Review of Rate Setting. We recommend the Legislature consider requiring DDS to comprehensively review the rate structure on a regular basis—perhaps every ten years—to determine whether it is still being used as intended; whether it meets consumers’ needs; and whether it needs adjustments, or wholesale changes, to adapt to the changing needs of consumers or the economy.