LAO Contacts

Update (3/4/19): Figure 3 totals adjusted.

February 28, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Governor's Proposals for Infants and

Toddlers With Special Needs

Summary

Weaknesses of California’s Early Intervention System Identified in Prior LAO Report. California provides early intervention services to about 50,000 infants and toddlers with either a disability (such as a visual or hearing impairment) or a significant developmental delay (such as not beginning to speak or walk when expected). These services are provided under three programs administered by two agencies: regional centers and schools. Our recent report, Evaluating California’s System for Serving Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs, identified several weaknesses with the state’s early intervention system, including: persistent service delays, poorly coordinated transitions between regional center early intervention and school‑based special education services, and large differences between the amount of funding and parental choice offered to families served by schools and regional centers.

Governor’s Budget Includes Three Proposals Related to Early Intervention Services. First, the Governor proposes $60 million ongoing (split between Proposition 56 [2016] tobacco tax revenues and federal Medicaid funding) to provide supplemental payments to physicians who screen children covered by Medi‑Cal for developmental delays. Second, the Governor proposes four new positions (at a cost of $446,000 General Fund) to increase state oversight of regional center early intervention services. Finally, the Governor expresses concerns about transitioning children from regional center early intervention services to school‑based preschool services at age three and indicates forthcoming trailer bill language may seek to improve these transitions.

Proposed Supplemental Payments Not a Cost‑Effective Option for Serving More Children. Many factors potentially contribute to some children who are eligible for early intervention services going without such services. The Governor’s proposed supplemental payments address one such potential factor—the possibility that some children covered by Medi‑Cal are not being screened for developmental delays. However, current state policies already require Medi‑Cal plans to provide such screenings and cover associated costs. Under the Governor’s proposal, the state would essentially pay twice for services it already requires. We recommend rejecting this proposal and instead focusing on more cost‑effective options for serving more children, such as better enforcement of existing Medi‑Cal requirements or providing supplemental payments to providers willing to serve children in their families’ homes (and thereby decreasing the number of parents unable to find a nearby provider of early intervention services).

Governor’s Other Proposals Are Reasonable, Recommend Adopting Alongside Broader Reforms. The Governor’s proposals to increase state oversight of regional centers and improve preschool transition planning represent promising first steps towards addressing some of the systemic weaknesses identified in our recent report. However, we recommend the Legislature also consider broader reforms (in particular, consolidating all early intervention services under a single agency) to fully address these weaknesses.

The Governor’s budget includes three proposals relating to services for infants and toddlers with special needs. In this report, we provide overarching background on the state’s system for serving such children and then describe and assess the Governor’s proposals regarding developmental screenings, state oversight of regional centers, and preschool transitions. These assessments largely build off our recent report, Evaluating California’s System for Serving Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. We conclude this report with a discussion of the extent to which the Governor’s proposals overall address the deficiencies identified in that report. We then recommend a path forward for the Legislature.

Background

California Serves About 50,000 Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs. In 2017‑18, California provided early intervention services to 47,500 infants and toddlers with special needs (by 2019‑20, this number is expected to exceed 56,000). These infants and toddlers either have a disability (such as a visual or hearing impairment) or a significant developmental delay (such as not beginning to speak or walk when expected). The state’s early intervention system provides these infants and toddlers with services such as speech therapy and home visits focused on helping parents promote their child’s development.

Federal Law Establishes a General Framework for Early Intervention Services. As a condition of receiving federal early intervention funding, California adheres to a five‑step process established by Part C of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

- Referral. Primary care physicians typically refer infants and toddlers following routine checkups. In addition, parents may seek out services directly.

- Evaluation. Following each referral, specialists evaluate the child and speak to the parents to determine eligibility for early intervention services.

- Individualized Family Service Plan. The family of a child deemed eligible for services meets with staff to develop an individualized family service plan. These plans are reviewed at least once every six months. Typically, these plans include authorization for targeted services such as weekly speech therapy sessions and regular home visits from an early education specialist who provides support on a wide range of developmental issues.

- Identification of Providers. Staff help parents identify appropriate providers for the services listed in the plan.

- Service Provision. Direct service providers typically provide services in the child’s home, alongside the child’s parents (or other primary caregiver). This practice is intended to ensure parents learn how to promote their child’s development as part of their daily routines. (In some cases, services might be provided in a clinical or group setting.)

Research Finds Several Benefits From Specific Early Intervention Programs. Many studies have rigorously identified positive impacts from specific early intervention programs. These programs are typically designed to address specific developmental challenges—for example, children with severe autism—and sometimes require relatively intensive supports (in some cases, 20 hours or more of professional therapy per week). Studies generally find such programs promote development in early years while reducing the need for intensive supports later in life.

Unclear Whether Federal Early Intervention Framework Is Sufficient to Produce These Same Benefits. Although studies have documented benefits for a variety of specific early intervention programs, there are reasons to doubt such benefits extend to all programs offered under the very broadly‑crafted federal early intervention framework. For example, the services offered under that framework typically range in intensity from about 1 to 4 hours of professional therapy per week, notably less than the 20 hours per week offered by some programs with well‑documented benefits. Researchers have yet to rigorously document the benefits of the federal framework.

Federal Law Leaves Two Important Policy Decisions Up to the States. Within IDEA’s basic framework, the federal government allows states to make two important policy decisions.

- Eligibility. Federal law requires states to serve all children with specific disabilities or “significant developmental delays,” but allows each state to define what constitutes a significant delay. Researchers generally categorize each state’s eligibility criteria as broad, moderate, or narrow. California’s current eligibility is considered broad and is estimated to apply to roughly 20 percent of the state’s infants and toddlers. About half of the states have eligibility criteria as broad as (or broader than) California’s, whereas the other half have more targeted criteria. (Between 2009 and 2015, the state temporarily restricted eligibility due to fiscal constraints.)

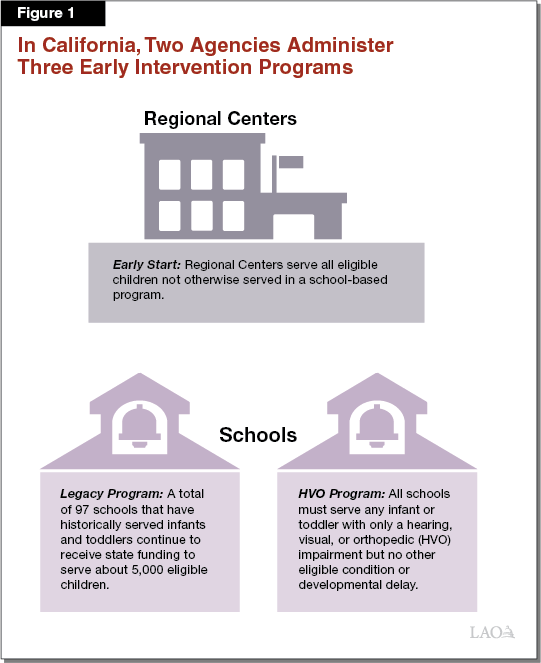

- Administration. Each state may decide which specific agency to entrust with serving all eligible children. Some states delegate this responsibility to a human services agency, whereas others rely on local schools. As Figure 1 shows, California has adopted a uniquely complex patchwork of three programs operated by both schools (under the direction of the California Department of Education) and regional centers (under the direction of the Department of Developmental Services, or DDS).

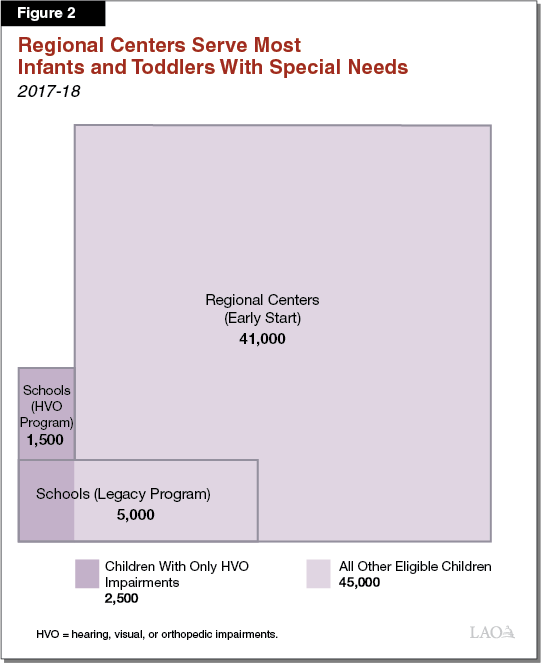

Regional Centers Administer Most of California’s Early Intervention Services. Figure 2 illustrates the relative proportions of infants and toddlers currently served in each of California’s three early intervention programs. The regional center early intervention program is named Early Start and accounts for most children served.

Regional Centers Coordinate Services From Outside Providers. Although schools typically employ their own early intervention service providers (such as speech therapists), regional centers coordinate services from and enter into contracts with independent providers. Such providers include specialists in private practice and nonprofits dedicated to early intervention. In addition, some regional centers contract with schools to provide early intervention services.

Medi‑Cal Supports Early Intervention in Two Ways. About half of California’s infants and toddlers are covered by Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, which is supported by both state and federal funding. Medi‑Cal supports California’s early intervention system in two ways.

- Regular Developmental Screenings. Medi‑Cal requires regular developmental screenings for enrolled children. However, because physicians often do not consistently report the specific services they provide, the state does not know how often this requirement is followed and thus how many children currently receive developmental screenings in Medi‑Cal.

- Early Intervention Services. Medi‑Cal pays for some early intervention services authorized by regional centers. State law requires regional centers to help families access services covered by their health insurance—including Medi‑Cal—before using regional center funding to pay for early intervention services. The most common early intervention services covered by Medi‑Cal include speech, physical, and occupational therapies.

Despite Following Federal Framework, the State Funds Most Early Intervention Services. After tapping into health insurance (which we estimate provides roughly $60 million annually), California covers most remaining early intervention costs with a combination of targeted state and federal funding. Figure 3 shows state and federal funding in 2018‑19 for early intervention services in California. Even though the federal government sets the basic framework for early intervention services, the state provides the majority of targeted funding for these programs ($504.5 million in state funding as compared to $51.5 million in federal funding).

Figure 3

State Provides Most Targeted Funding for Early Intervention

LAO Estimates for 2018‑19a (In Millions)

|

Fund Source |

Amount |

|

Regional Centers: Early Start |

|

|

State Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund |

$424.2 |

|

Federal IDEA Part C Grant |

37.3 |

|

Subtotal |

($461.5) |

|

Schools: Legacy Program |

|

|

State Proposition 98 General Fund |

$77.8 |

|

Subtotal |

($77.8) |

|

Schools: HVO Program |

|

|

Federal IDEA Part C Grant |

$14.2 |

|

State Proposition 98 General Fund |

2.4 |

|

Subtotal |

($16.6) |

|

Total |

$555.9 |

|

aDoes not include (1) Early Start services billed to Medi‑Cal and private insurance, (2) Early Start services reimbursed by federal Early Periodic Screening and Diagnosis and Treatment funding, or (3) general purpose K‑12 funds locally repurposed to support school‑based early intervention. |

|

|

IDEA = Individuals With Disabilities Education Act and HVO = hearing, visual, or orthopedic impairments. |

|

Regional Centers Subject to State Oversight. Once every three years, DDS reviews each of California’s 21 regional centers for their performance in administering early intervention services. When a review finds a regional center is not consistently meeting federal early intervention requirements (for example, when a regional center is not ensuring services begin soon after children are deemed eligible), the center is required to develop a corrective action plan.

Service Provider Rates Paid by Regional Centers Have Been Largely Frozen for Many Years. In response to state budget constraints, state law effectively froze rates for existing Early Start providers in 2003 and capped rates for new providers at the statewide median rate in 2008. Rates have largely been unchanged since that time, aside from one overall increase in 2016 and ongoing adjustments to account for rising state minimum wage costs. A forthcoming rate study (which concerns rates paid to a variety of service providers in the regional center system, including those in Early Start), will likely recommend adjustments to these rates when the study is submitted to the Legislature on March 1.

Governor’s Proposals

Below, we describe, assess, and offer associated recommendations for the three proposals from the Governor related to early intervention. We then provide an overall assessment of the Governor’s package of early intervention proposals and offer an associated recommendation.

Developmental Screenings

Governor Proposes $60 Million Ongoing to Increase Screenings for Developmental Delays. Under the Governor’s proposal, physicians serving children in Medi‑Cal would receive supplemental payments to screen these children for developmental delays. The administration estimates $60 million would support about one million screenings annually. (The proposed $60 rate per screening is equal to the rate currently paid for developmental screenings administered under Medi‑Cal fee‑for‑service.) Associated costs would be covered by a combination of Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenues and federal funding for Medi‑Cal. Notably, state policy currently requires Medi‑Cal managed care plans to provide such screenings, and thus, some portion of the proposed one million screenings currently occurs and would occur even absent the Governor’s proposal. (The vast majoirity of children enrolled in Medi‑Cal are in managed care plans.)

Assessment

California Likely Serves Only a Small Proportion of Children Eligible for Early Intervention. The administration believes expanded screenings would allow California to identify and serve more children with developmental delays. Researchers agree that many eligible children are not currently served, although (as we discuss in greater detail below) it is not clear whether this is primarily due to a lack of screenings. In 2017‑18, we estimate California provided early intervention to about 4 percent of its infants and toddlers. Some researchers believe roughly 20 percent of California’s infants and toddlers are eligible for early intervention under the state’s current eligibility criteria.

Failing to Serve All Eligible Children Contravenes Federal Requirements, Raises Equity Concerns. Although federal law allows states to establish their own eligibility criteria for early intervention, it requires each state to identify and serve all children meeting these state‑specific criteria. This requirement is intended to ensure states treat similar children similarly. Because California does not identify and serve all eligible children, it may treat similar children dissimilarly, serving some children with specific developmental challenges but not serving others with the exact same challenges.

There Are at Least Five Possible Reasons California Does Not Serve All Eligible Children. In conversations with stakeholders and experts, we were made aware of at least five major reasons why some eligible children do not receive early intervention services.

- First, some children do not receive regular physician checkups.

- Second, some physicians do not consistently screen children for developmental challenges.

- Third, some physicians do not refer all potentially eligible children for formal evaluations (in some instances because these physicians are unfamiliar with the state’s early intervention system or misunderstand its eligibility criteria).

- Fourth, some parents do not follow through on physicians’ referrals (in some instances because they hope their children will grow out of their developmental challenges).

- Fifth, some parents who try to follow through on referrals become discouraged before their children receive services. In some instances, this is because the evaluation process itself is time‑consuming or difficult to understand. In other instances, parents may become discouraged even after their children are deemed eligible for services because they are unable to find providers who accept their insurance (including Medi‑Cal), are willing to provide services in the families’ homes (as encouraged by federal law), or whose clinics are within reasonable travel distances.

Governor’s Proposal Addresses One of These Five Reasons, But This May Not Be the Most Important One. Of these five factors listed above, the Governor’s proposal only addresses the issue of inconsistency in the provision of developmental screenings. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient data to determine whether this factor plays an especially large role in preventing eligible children from being served, or whether any of the other four factors are more significant. In conversations with stakeholders and experts, many told us that they are particularly concerned about the likelihood parents will either not follow through on physician referrals or become discouraged before their children receive services. The administration has not provided a compelling rationale for devoting resources solely to developmental screenings rather than to addressing the other four reasons children go unserved.

Under Governor’s Proposal, State Would Pay Twice for Services It Already Requires. In contracting for Medi‑Cal managed care plans, the state requires these plans to follow certain federal guidelines calling for regular developmental screenings of all children ages birth through three. Because such screenings are already required, the state builds at least a portion of associated costs into the per‑child payment that Medi‑Cal managed care plans receive on behalf of enrolled children. The Governor’s proposal would thus provide supplemental payments for an activity managed care plans are already required to arrange and for which they are already compensated. For managed care plans that base their reimbursement off Medi‑Cal fee‑for‑service, the Governor’s proposal would exactly double the total payment currently provided for these screenings. (Although the state sometimes provides supplemental payments for other services required by managed care plans, such as well‑child visits, the administration has not provided a compelling rationale for doing so in this case, and specifically has not demonstrated this proposal is the most cost‑effective approach to identifying more children with developmental delays.)

Governor’s Budget Does Not Account for the Cost of Serving More Children. Although the administration believes the proposed supplemental payments for developmental screenings will result in more eligible children being identified for early intervention, the Governor’s budget provides no additional funding to serve these children once identified. If the Governor’s proposal resulted in more eligible children being served, the associated cost increase could total hundreds of millions of dollars annually (for example, if the number of children served increased 50 percent, the associated Early Start costs to serve these children would be about $250 million).

California May Not Have Enough Providers to Serve All Eligible Children. Although we are uncertain how many additional children would end up receiving early intervention services because of the administration’s proposal (since we do not have good provider data about the number of screenings already occurring), we caution that any effort to serve more children may be complicated by a shortage of qualified providers. Regional centers indicate they already have difficulty finding providers to serve current caseloads. Although the state could address relatively small shortages by increasing provider rates (which have not been increased on a regular basis for many years), addressing larger shortages might require long‑term strategies such as expanding training programs and attracting more candidates into relevant fields.

Recommendation

Reject Governor’s Proposal, Develop Strategy for Identifying All Eligible Children. California already requires and has mechanisms to automatically pay for Medi‑Cal plans to provide developmental screenings to all children. While supplemental payments may be appropriate in situations where other program improvement strategies are likely to fail, the administration has not provided a compelling reason to provide supplemental payments as opposed to pursuing alternative solutions. At $60 million in total projected costs, the Governor’s proposal to introduce additional, supplemental payments for these screenings is very likely not cost‑effective compared to alternative solutions for identifying more children with developmental delays. We recommend the Legislature consider alternative strategies for identifying and providing early intervention services to more children. Such strategies can be tailored to each of the five factors currently preventing some eligible children from being served, and may include:

- Pursuing policies to increase the number of children receiving regular checkups.

- Increasing enforcement of existing requirement that children in Medi‑Cal managed care plans receive regular developmental screenings, for example by including developmental screenings in the state’s public accountability measures that summarize and compare Medi‑Cal managed care plan performance. In addition, since the state already provides a supplemental payment for well‑child visits, it could make that supplemental payment contingent upon the concurrent delivery of a developmental screening.

- Better educating physicians about the early intervention system, in particular its eligibility requirements and how to make a referral.

- Assisting parents in following through on physician referrals.

- Increasing provider rates or providing supplemental payments to providers willing to serve children in their families’ homes, thereby decreasing the number of parents unable to find a nearby provider.

Serving More Children Will Increase State Costs. If the state managed to identify and serve all eligible children, associated service costs would likely increase by hundreds of millions of dollars. In addition, the state may have to develop a concurrent strategy to address potential provider shortages which might otherwise preclude serving all eligible children. Depending on how such a strategy was structured, it too may increase state costs by tens of millions of dollars. We recommend the Legislature consider these costs when constructing its overall budget.

State Oversight of Regional Centers

Governor Proposes Increasing State Oversight of Regional Centers’ Early Start Programs. Citing concerns about the number of children eligible for Early Start services failing to receive these services within federally‑mandated time lines, the Governor proposes adding four full‑time positions at DDS (at a cost of $446,000 General Fund) to increase monitoring of regional center Early Start programs from once every three years to once every two years.

Assessment

California Continues to Lag Other States in Providing Timely Services. Because, absent support, babies developing a few days behind their peers might grow into toddlers who are several months or even a year behind, federal law requires that services begin soon after children are determined eligible for early intervention. In our recent evaluation of California’s early intervention system, we found California does worse than most other states in meeting federal deadlines for service delivery. Since publishing our evaluation, we received updated data for California which indicate the state has improved somewhat on meeting these deadlines but still does notably worse than most states were doing in their most recent data. Figure 4 summarizes the available data.

Figure 4

California Does Poorly in Meeting Federal Deadlines

Percentage of Children for Which State Completed Activities on Timea

|

Develop Initial Service Plan |

Begin Services |

|

|

2013‑14 |

||

|

25th Ranked State |

97.9% |

98.3% |

|

40th Ranked State |

95.1 |

94.6 |

|

Californiab |

82.1 |

82.1 |

|

2014‑15 |

||

|

California |

85.5% |

88.8% |

|

aAn initial service plan is to be developed within 45 days of referral. Services are to begin within 45 days of an initial service plan. bIn 2013‑14, California ranked 46th among the 50 states in meeting the initial service plan deadline and 47th in meeting the begin services deadline. Data from the 49 states are not yet available for 2014‑15. |

||

Increased Oversight Might Partially Address Service Delays . . . Currently, DDS reviews each regional center once every three years to ensure it is meeting federal early intervention requirements. When it finds that a regional center is struggling to meet federal deadlines or otherwise falling short of federal requirements, that regional center is required to develop a corrective action plan. Increasing the frequency of these reviews to once every two years, as the Governor’s budget proposes, might further encourage some regional centers to address long‑standing deficiencies.

. . . But Eliminating Service Delays Likely Requires Broader Reform. Given the scope and persistence of California’s struggles with providing timely early intervention services, we do not believe the Governor’s proposal goes far enough. In our recent evaluation, we suggested California’s uniquely complicated early intervention system (under which two agencies operate three separate programs) likely generates some confusion and contributes to service delays. Administrative consolidation may therefore produce more timely services.

Recommendation

Adopt Governor’s Proposal, Consider Broader Administrative Reform. The Governor’s proposal to increase state oversight of regional centers’ Early Start programs appears reasonable and may improve—albeit modestly—the state’s problems with service delays. However, we continue to encourage the Legislature to consider consolidating all early intervention programs under a single agency, as we believe this would be the single most important step towards eliminating service delays. If services were consolidated under regional centers, it could potentially result in state savings in the low tens of millions of dollars which could be repurposed to serve more eligible children. If services were consolidated under schools, on the other hand, it could potentially result in significant added costs potentially reaching the low hundreds of millions of dollars.

Preschool Transitions

Governor Expresses Concern About Preschool Transitions, Formal Proposal May Be Forthcoming. In the 2019‑20 Governor’s Budget summary, the administration expresses an intent to “pursue statewide policies” to improve the transitions from Early Start to preschool special education services for three‑year olds with special needs. Although the Governor’s budget includes no specific proposal fulfilling this intent, the administration indicates that future actions may include relevant trailer bill language.

Assessment

California Continues to Perform Worse Than Other States in Facilitating Preschool Transitions. Many children who qualify for early intervention are also eligible to receive special education from their local schools when they turn three. To ensure a smooth transition between early intervention and special education services, federal law requires states to begin planning such transitions no later than 90 days before each child’s third birthday. In our recent evaluation of California’s early intervention system, we found California does worse than most other states in satisfying these federal requirements. Since publishing our evaluation, we received updated data for California (though not from the other 49 states) which indicate the state has made little progress in meeting the deadlines associated with this transition. Figure 5 summarizes the available data.

Figure 5

California Does Poorly in Planning Preschool Transitions

Percentage of Children for Which State Completed Activities on Timea

|

Notify School |

Hold Planning Conference |

Develop Transition Plan |

|

|

2013‑14 |

|||

|

25th Ranked State |

99.7% |

98.0% |

99.3% |

|

40th Ranked State |

94.3 |

90.7 |

94.4 |

|

Californiab |

74.5 |

86.2 |

91.4 |

|

2014‑15 |

|||

|

California |

76.1% |

87.9% |

80.4% |

|

aDeadline for all activities is 90 days before child’s first birthday. bIn 2013‑14, California ranked 47th among the 50 states in notifying schools about impending transitions, 44th in holding planning conferences, and 47th in developing transition plans. Data from the 49 states are not yet available for 2014‑15. |

|||

Recommendation

Establish Best Practices to Improve Preschool Transition. We recommend the Legislature adopt legislation requiring regional centers to exercise a series of best practices regarding preschool transitions. These best practices could include having regional centers develop annual inter‑agency agreements with each school in their service area to specify the general process for handling preschool transitions, identify a specific point of contact at each school for coordinating all transitions, implement shared data systems to allow both agencies to track children nearing their third birthdays, and develop a process for summer months when schools are typically closed. We believe these recommendations could be accomplished either by reprioritizing existing resources or with a relatively modest increase in regional center funding in the low millions of dollars.

A Path Forward

Governor’s Proposals Come in the Wake of Recent LAO Evaluation of State’s Early Intervention System. Our recent report, Evaluating California’s System for Serving Infants and Toddlers With Special Needs, identified significant weaknesses in California’s early intervention system. These included persistent service delays, poorly coordinated transitions between Early Start and preschool special education services, and large differences between the amount of funding and parental choice offered to families served by schools and regional centers. Below, we evaluate the Governor’s package of early intervention proposals in the context of our earlier findings and other recent research.

Governor’s Proposals Respond to Some Weaknesses in California’s Early Intervention System . . . Specifically, the Governor’s proposals to increase regional center monitoring and improve preschool planning are intended to address persistent concerns regarding service delays and preschool transitions.

. . . But Leave Others Untouched. Most notably, the Governor’s budget does not address the large differences between the amount of funding and parental choice offered to families served by schools and regional centers.

Recommendation for Development of Comprehensive Strategy

Develop Comprehensive Strategy for State’s Early Intervention System. Given the notable weaknesses of the state’s current early intervention system, we recommend the Legislature revisit the two major policy decisions it made in first establishing this system more than 30 years ago.

- Eligibility. Although California now has a long experience with relatively broad eligibility criteria, it has yet to identify and serve all eligible children. Serving all eligible children may require a substantial increase in state funding as well as a concerted strategy to address provider shortages.

- Administration. As we discussed in our previous report, we believe the state’s bifurcated early intervention system has several weaknesses, including service delays and unjustified differences between school‑based and regional center programs. We recommend the state consider options for moving towards a unified system.