LAO Contacts

- Sara Cortez

- One-Time Improvement Initiative

- Full-Day Preschool Expansion

- CalWORKs Caseload and

Cost of Care

- Amy Li

- Full-Day Kindergarten Expansion

March 4, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Early Education Analysis

- Introduction

- Overview

- Full‑Day Kindergarten Expansion

- One‑Time Improvement Initiative

- State Preschool

- CalWORKs Child Care

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s early education proposals. Below, we highlight key messages from the report.

Full‑Day Kindergarten Expansion

Recommend Against Funding More Kindergarten Facility Grants at This Time. The 2018‑19 budget provided $100 million one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for kindergarten facility grants. The state primarily intended the grants to cover the facility costs associated with converting part‑day kindergarten programs to full‑day programs. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget provides an additional $750 million for this purpose. We analyzed the first‑round applications for the existing grant program and found that most grants likely will go to districts already running full‑day programs. Because the program as currently structured does not notably advance the state’s core objective of increasing the number of full‑day programs, we recommend the Legislature not proceed with an expansion of the grant program at this time. This would free up $750 million for other budget priorities.

If Interested in Promoting Full‑Day Kindergarten Programs, Explore Options That Are More Targeted. The Legislature could revisit the Governor’s proposal in 2020‑21 after evaluating all the applications submitted for the initial $100 million in grants. (A second round of applications will be initiated shortly.) Should the Legislature desire to provide more grants based on a review of these applications, we recommend it create a more targeted program focused on districts running part‑day programs due to facility constraints. We encourage the Legislature to structure any new grant rules such that they do not create incentives to circumvent the existing School Facility Program or otherwise work at cross purposes with it. Should the Legislature be interested in creating an even stronger incentive for full‑day programs, it could consider reducing the part‑day per‑student kindergarten rate under the Local Control Funding Formula. The part‑day rate currently is the same as the full‑day rate despite the fewer hours of instruction provided. Before lowering the part‑day rate, we think the Legislature should weigh the trade‑offs of part‑day and full‑day programs carefully, as some parents prefer to send their children to part‑day programs.

One‑Time Improvement Initiative

Recommend Collecting Basic Information Before Expending One‑Time Funds. The Governor’s budget includes $500 million one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to improve the state’s child care and preschool system. Specifically, the budget includes (1) $245 million for child care workforce grants, (2) $245 million for facility grants to help support expansion, and (3) $10 million for a plan on how to improve child care access and affordability. Unfortunately, the state’s lack of information about key aspects of the existing system makes prioritizing one‑time funding difficult. Instead of designating the funding now, the Legislature could set aside some amount of one‑time funding into an account specifically earmarked for child care expansion and improvement efforts. Additionally, instead of spending $10 million on another child care plan (given the many plans already developed to date), we recommend the Legislature designate $1 million each for two focused studies. We recommend one study survey providers on their facility arrangements and another study survey parents about their child care arrangements. We recommend these reports be completed by October 2020 (the same time the results of a workforce survey are expected) to ensure the additional information is available to inform 2021‑22 budget decisions. Upon receiving the results of the studies, the Legislature could then begin allocating the funds set aside in 2019‑20.

Full‑Day Preschool Expansion

Recommend Slower Ramp Up Given Logistical Challenges. The Governor’s budget includes $125 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to provide 10,000 additional full‑day State Preschool slots for non‑local education agencies (LEAs) beginning July 1, 2019. This expansion is the first of three planned augmentations over the next three fiscal years, with the goal of serving all low‑income four‑year olds by 2021‑22. If adopted, the Governor’s proposal would be the largest increase earmarked for non‑LEAs to date. We think non‑LEAs might be unable to accommodate all 10,000 slots in 2019‑20. We recommend funding fewer slots in 2019‑20 (2,500 full‑day slots) and starting them mid‑year. This increase provides a significant number of new slots for non‑LEAs, while recognizing the logistical challenges of expanding quickly. We also recommend providing $4 million in ongoing funding for local planning councils to assist providers with facility expansion. In addition, we recommend adopting the Governor’s proposal to fund all non‑LEA slots from one fund source. In the future, the Legislature could consider funding all State Preschool (LEA and non‑LEA slots) from one fund source to give providers maximum flexibility in serving families.

Recommend Keeping Full‑Day Program Focused on Working Families. The Governor proposes to eliminate the requirement that families must be working or in school for their children to be eligible for full‑day State Preschool. The Governor’s proposal, however, does not account for the behavioral effect of families accessing more full‑day care. If more families choose full‑day care, the cost of the program would increase substantially, as full‑day slots cost more than double part‑day slots. Absent additional funding, removing the work requirement could result in serving fewer overall children than projected and fewer children from working families (as working families effectively would be competing for full‑day slots with families in which one parent stays home). We recommend keeping the work requirement to ensure full‑day State Preschool slots are available to address the needs of working families.

CalWORKs Child Care Programs

Consider Providing More Funding to Cover Potentially Higher 2019‑20 Caseload. The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) Stages 2 and 3 programs provide child care services to certain families. In 2017‑18, the state made two changes that significantly increased caseload. The state (1) increased income eligibility and (2) required families to report information for determining eligibility only once per year. Though caseload has increased notably in recent years, the administration projects CalWORKs Stages 2 and 3 caseload will increase only 3 percent in 2019‑20. The Legislature may want to budget more funding in the event caseload grows more quickly than the administration assumes. If Stages 2 and 3 caseload were to increase 9 percent—triple the rate the administration assumes but still lower than growth the past two years (11 percent and 15 percent, respectively)—the Legislature would need to provide an additional $33 million to cover program costs.

Introduction

In this report, we provide an overview of the Governor’s early education proposals, then analyze his three major proposals in this area. Specifically, we analyze his proposals to (1) fund facilities for more full‑day kindergarten programs, (2) make targeted one‑time improvements to the child care and preschool system, and (3) expand the number of full‑day preschool slots. We then assess the administration’s cost estimates for the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) child care programs. We end the report with a summary of our early education recommendations.

Overview

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s early education budget proposals.

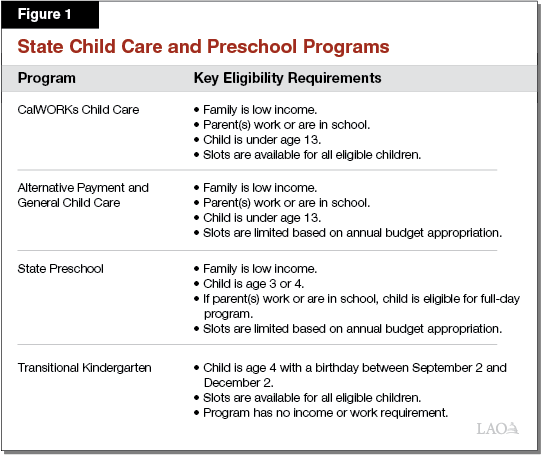

State Subsidizes Child Care and Preschool, Primarily for Low‑Income Children. The state subsidizes child care and preschool through several programs. As Figure 1 shows, these programs have somewhat different eligibility requirements. CalWORKs child care programs focus on families engaged in or transitioning out of welfare‑to‑work activities. The remaining programs are primarily designed for other low‑income, working families, with the exception of transitional kindergarten, which is age based and has no family work requirement. In 2018‑19, these programs are receiving a total of $4.7 billion in state and federal funding.

Governor’s Budget Includes $5.3 Billion for Child Care and Preschool Programs in 2019‑20. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor’s budget augments these programs by a total of $669 million (14 percent) from the revised 2018‑19 level. This increase is the net effect of a $1.1 billion (78 percent) augmentation in non‑Proposition 98 General Fund, a $211 million (10 percent) decrease in Proposition 98 General Fund (largely to account for the reclassification of certain State Preschool costs as non‑Proposition 98 General Fund), and a $218 million (25 percent) decrease in federal funding (largely to account for the expiration of a one‑time Child Care and Development Fund augmentation provided in 2018‑19). Under the Governor’s budget, proposed funding would support 492,000 child care and preschool slots—a 4 percent increase from 2018‑19. (Cost increases are greater than slot increases because a large, proposed one‑time augmentation does not add any slots.)

Figure 2

Child Care and Preschool Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 Revised |

2018‑19 Reviseda |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Expenditures |

|||||

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

Stage 1 |

$323 |

$292 |

$276 |

‑$16 |

‑5.5% |

|

Stage 2b |

504 |

560 |

597 |

37 |

6.6 |

|

Stage 3 |

339 |

399 |

482 |

84 |

21.0 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,167) |

($1,250) |

($1,355) |

($105) |

(8.4%) |

|

Non‑CalWORKs Child Care |

|||||

|

General Child Carec |

$340 |

$412 |

$457 |

$45 |

10.9% |

|

Alternative Payment Program |

292 |

530d |

340 |

‑189 |

‑35.8 |

|

Bridge program for foster children |

20 |

41 |

45 |

4 |

9.8 |

|

Migrant Child Care |

35 |

40 |

45 |

5 |

12.0 |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

2 |

2 |

2 |

—e |

2.6 |

|

Subtotals |

($349) |

($1,024) |

($889) |

(‑$136) |

(‑13.3%) |

|

Preschool Programsf |

|||||

|

State Preschool—full day |

$738 |

$804 |

$977 |

$173 |

21.5% |

|

State Preschool—part dayg |

503 |

538 |

552 |

14 |

2.6 |

|

Transitional Kindergartenh |

808 |

861 |

890 |

29 |

3.3 |

|

Preschool QRIS Grant |

50 |

50 |

50 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($2,098) |

($2,253) |

($2,468) |

($215) |

(9.5%) |

|

Support Programs |

$91 |

$144 |

$629 |

$485 |

336.1% |

|

Totals |

$3,704 |

$4,672 |

$5,341 |

$669 |

14.3% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

Proposition 98 General Fund |

$1,930 |

$2,077 |

$1,865 |

‑$211 |

‑10.2% |

|

Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund |

746 |

1,417 |

2,524 |

1,107 |

78.1 |

|

Federal CCDF |

635 |

857 |

639 |

‑218 |

‑25.4 |

|

Federal TANF |

388 |

311 |

298 |

‑13 |

‑4.1 |

|

Federal Title IV‑E |

5 |

10 |

14 |

4 |

41.3 |

|

aReflects Department of Social Services’ revised Stage 1 estimates. Reflects budget act appropriation for all other programs. The 2018‑19 budget plan also funds the Inclusive Early Education Expansion Program ($167 milllion) using 2017‑18 Proposition 98 General Fund. Funding for this proposal is not included in this table. bDoes not include $9.2 million provided to community colleges for certain child care services. cGeneral Child Care funding for State Preschool wraparound care shown in State Preschool—full day. dIncludes $205 million for additional slots in 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. eLess than $500,000. fSome CalWORKs and non‑CalWORKs child care providers use their funding to offer preschool. gIncludes $1.6 million each year used for a family literacy program offered at certain State Preschool sites. hReflects preliminary LAO estimates. Transitional Kindergarten enrollment data are not yet publicly available for any year of the period. |

|||||

|

QRIS = Quality Rating and Improvement System; CCDF = Child Care and Development Fund; and TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

|||||

Bulk of New Funding Is for One‑Time Purposes, Rest for Ongoing Commitments. Figure 3 shows the Governor’s child care and preschool proposals. The Governor’s one‑time child care initiative consists of $500 million primarily intended to improve the child care workforce and expand child care facilities. The largest ongoing augmentation is $125 million to expand the number of full‑day State Preschool slots. The Governor’s budget also includes a net increase of $103 million to reflect changes in CalWORKs child care caseload and cost of care. For non‑CalWORKs child care programs, the budget includes $79 million for a statutory 3.46 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment, partially offset by a $20 million reduction due to a projected 0.89 percent decrease in the birth through four population in California. The budget also incorporates the cost to annualize certain policies initiated in the current year. In addition to these child care and preschool augmentations, the Governor proposes $750 million one time to help school districts cover facility costs associated with converting their part‑day kindergarten programs into full‑day programs.

Figure 3

Governor Has Several Child Care and Preschool Proposalsa

(In Millions)

|

One‑Time Initiative |

|

|

Workforce development |

$245 |

|

Infrastructure |

245 |

|

Plan |

10 |

|

Subtotal |

($500) |

|

Ongoing Commitments |

|

|

10,000 additional full‑day State Preschool slots |

$125 |

|

CalWORKs child care caseload and cost of care |

103b |

|

Non‑CalWORKs child care COLA and slots |

59 |

|

Annualization of certain adjustment factors applied January 2019 |

40 |

|

Annualization of State Preschool slots added April 2019 |

27 |

|

Annualization of Alternative Payment slots added September 2018 |

3 |

|

Subtotal |

($357) |

|

All Other Changesc |

‑$188 |

|

Total |

$669 |

|

aIn addition to these child care and preschool proposals, the Governor proposes $750 million one time to increase the number of full‑day kindergarten programs. bOf this amount, $80 million is associated with higher 2018‑19 caseload. Excludes $1.4 million that is embedded in the “annualization of certain adjustment factors” row. cLargely reflects the expiration of one‑time 2018‑19 funds. |

|

Full‑Day Kindergarten Expansion

In this section, we begin by providing background on kindergarten programs and existing state funding for full‑day kindergarten facilities. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for kindergarten facilities. We conclude with our assessment and recommendation.

Background

California Requires School Districts to Operate Kindergarten Programs. The state requires all elementary and unified districts to offer kindergarten classes that are taught by credentialed teachers and adhere to California’s academic standards. In California, kindergarten is open to all five year olds, including students who turn five between September 2 and December 2. (These younger students qualify for two years of kindergarten.) Kindergarten programs currently serve about 530,000 students statewide.

School Districts May Run Part‑Day or Full‑Day Programs. Districts determine the length of their kindergarten programs. Part‑day programs operate between three hours (the state required minimum) to four hours per day, whereas full‑day programs operate for more than four hours per day. A recent survey released by the California Department of Education (CDE) found that part‑day programs averaged 3.5 hours per day, whereas full‑day programs averaged 5.6 hours per day. Schools operating part‑day programs typically run a morning session and afternoon session in the same classroom using two teachers throughout the day. One teacher leads the class in the morning session while the other leads in the afternoon session. In contrast to part‑day sessions, each full‑day session requires a separate classroom and is typically assigned one full‑time teacher who leads the class throughout the day. The teacher may receive assistance from an instructional aide. The state funds kindergarten through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), which provides districts the same per‑student funding rate for part‑day and full‑day programs ($8,235 per student in 2018‑19).

Most Districts Operate Full‑Day Programs. As of 2017‑18, 71 percent of school districts ran only full‑day kindergarten programs, 19 percent ran only part‑day programs, and 10 percent ran a mix of full‑day and part‑day programs. Based on program data reported to CDE, we estimate that roughly 370,000 (70 percent) of kindergarten students attend a full‑day program and roughly 160,000 (30 percent) attend a part‑day programs. Over the past two decades, the share of students attending full‑day programs has grown notably. A 2007‑08 survey found that 43 percent of students were attending full‑day programs, with many districts reporting that they converted from part‑day to full‑day programs during the mid‑2000s.

School Facility Program (SFP) Provides Funding to Build and Renovate Facilities. The state and school districts share the cost of building new school facilities and modernizing old ones. The state generally covers 50 percent of the cost of new construction for districts unable to accommodate all existing or projected enrollment and 60 percent of the cost of renovating facilities that are at least 25 years old. For both types of projects, the state can contribute up to 100 percent of project costs if districts face challenges in raising their local shares. The state covers its share of cost using state general obligation bonds whereas school districts typically cover their share using local general obligation bonds. In certain cases, the SFP allows districts completing projects below the budgeted cost to use project savings for other facility priorities. (The exception is for districts that receive state funding in excess of the standard cost shares. These districts are required to return any unspent funds to the state.)

State Created Kindergarten Facility Grants Last Year. During budget deliberations last year, the Legislature indicated that increasing the number of full‑day kindergarten programs throughout the state was a priority. The 2018‑19 budget package accordingly provided $100 million in one‑time General Fund to help districts cover the facility costs associated with converting part‑day kindergarten programs into full‑day programs. Similar to the SFP, the kindergarten facility grants are intended to cover 50 percent of the cost of constructing a new kindergarten classroom and 60 percent of the cost of renovating an existing kindergarten classroom, with the grants covering a higher share if a district faces challenges raising its local match. The grant rules regarding project savings also are similar to the SFP, with districts generally allowed to use savings for other facility priorities, unless they receive state funding beyond the standard share. The eligibility criteria for the new grants, however, are different from the SFP. Grant eligibility is based on (1) a school site not having enough classroom space to operate full‑day kindergarten or (2) the existing kindergarten classroom not meeting CDE regulations. If meeting either condition, an applicant can request funding for either new construction or renovation.

The Office of Public School Construction (OPSC) Administers School Facility Programs. OPSC administers both the SFP and the new kindergarten facility grants. It has decided to award the kindergarten grants through two application rounds—one that concluded this January that will allocate $37.5 million and another in May that will allocate $60 million. (As allowed by statute, OPSC has reserved the remaining $2.5 million for administrative costs it expects to incur over the current and subsequent three years.) To the extent the kindergarten grants are oversubscribed, the budget requires OPSC to give preference to districts that face challenges raising their local shares and districts with high proportions of low‑income students. Regulations adopted by OPSC also provide that the state will fund one project at each eligible district prior to allocating funds for additional projects. These regulations are intended to ensure grants are not disproportionately awarded to a small number of districts proposing a larger number of projects.

Initial Demand for Kindergarten Facility Grants Exceeds $100 Million. In the January application round, 70 districts requested a total of $262 million for 262 projects. The vast majority (76 percent) of these projects involve construction of new classrooms. Twenty‑seven districts requested additional state funds due to challenges raising their local share. The average share of low‑income students across the applicant pool is 72 percent. The OPSC currently is verifying grant eligibility for these applicants.

Governor’s Proposal

Provides Additional $750 Million for Full‑Day Kindergarten Facility Grants. The Governor proposes to provide $750 million in one‑time General Fund for additional grants in 2019‑20. These grants would operate similarly to the current grant program, with one exception. Districts would be allowed to use project savings for program support activities, in addition to facility purposes. For instance, districts could use savings for professional development or instructional materials to support full‑day programs. The new flexibility would apply even to those districts receiving state grants that cover the full budgeted cost of the kindergarten facility project.

Assessment

Grant Rules Are Broader Than Legislature’s Core Policy Objective. As the Legislature deliberated over the initial $100 million for kindergarten facility grants, it indicated its primary objective was encouraging districts to convert part‑day programs to full‑day programs. The Governor’s Budget Summary articulates the same goal, describing the $750 million augmentation as a way to “put California on a path for all kindergartners to attend full‑day kindergarten.” As structured, however, the grant program has eligibility rules much broader than this core objective. Most notably, districts currently running all full‑day programs are eligible to receive funding for constructing additional classrooms if their kindergarten classrooms do not meet CDE regulations. (For example, the classrooms do not have self‑contained restrooms or are located away from a parent drop‑off area.) Moreover, districts are eligible for new construction funding even if their overall enrollment is declining and they have space available elsewhere in the district. Given these grant rules, districts can apply to replace or upgrade their facilities rather than convert part‑day kindergarten programs to full‑day programs. Though districts likely will view the new kindergarten classrooms or upgrades as beneficial, the facility projects do not advance the state’s core goal of increasing full‑day programs.

Most Applicants for Existing Grant Program Already Run Full‑Day Programs. Our review of the first round of applications confirms that the initial interest in kindergarten facility grants is primarily among districts already operating full‑day programs. Of all applicants, we estimate that 76 percent already offer only full‑day programs (Figure 4). Given that the current funding round is oversubscribed, we also performed a second analysis focusing on the districts most likely to receive state funding under the rules establishing project priority. Specifically, we examined a subset of 24 districts reporting difficulty raising local matching funds or having particularly high shares of low‑income students. We found that a similar share of these districts (79 percent) already operate only full‑day programs. If the state were to provide another $750 million for the grant program, we believe much of the funding likewise could go to districts already operating full‑day programs.

Figure 4

Significant Majority of Initial Applicants Already Run Full‑Day Programs

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Programs Operated |

Districts Applying |

Projects Submitted |

Funding Requested |

|||||

|

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Full‑day only |

53 |

76% |

121 |

46% |

$135 |

52% |

||

|

Full‑day and part‑day |

9 |

13 |

100 |

38 |

86 |

33 |

||

|

Part‑day only |

8 |

11 |

41 |

16 |

41 |

16 |

||

|

Totals |

70 |

100% |

262 |

100% |

$262 |

100% |

||

Districts Operate Part‑Day Programs for a Variety of Reasons. We asked several districts about their reasons for operating part‑day instead of full‑day programs. Although some districts described limited classroom space as an important consideration, districts cited other reasons for running part‑day programs, including teacher and parent preferences. Some districts believed their teachers preferred part‑day programs because they received assistance from another teacher throughout the day. Some districts indicated their parents preferred a shorter school day for their children and were not interested in full‑day programs. A few districts also mentioned concern over the somewhat higher staffing costs for full‑day programs. Full‑day programs sometimes hire more support staff (such as instructional aides and custodians) compared to part‑day programs.

Most Districts Have Converted to Full‑Day Kindergarten Programs Using Existing State and Local Funds. The share of students attending full‑day kindergarten has grown significantly over the past two decades despite the absence of any specific state program funding kindergarten facilities. A district running part‑day programs can qualify for new construction funding under the existing SFP if it is experiencing an overall increase in its K‑12 enrollment or qualify for modernization funding if its classrooms are more than 25 years old (and likely do not meet CDE kindergarten regulations). Districts may also fund facility projects by raising local bond funds. Districts have successfully relied on these existing funding sources to expand their full‑day programs. Over the past ten years, the share of students enrolled in full‑day programs grew from 43 percent to 70 percent. Over just the past three years (from 2015‑16 to 2017‑18)—prior to the creation of the kindergarten facility grants—the share of districts offering full‑day programs grew from 64 percent to 71 percent. These trends suggest that existing state and local funds have been sufficient for most districts interested in operating more full‑day programs.

Recommendations

Recommend Against Expanding Grant Program at This Time. Based upon an analysis of first‑round applications, the existing kindergarten facility grants are not notably advancing the state’s objective of expanding full‑day programs, with the vast majority of applicants already running only full‑day programs. Moreover, the majority of districts already converted to full‑day kindergarten programs using existing state and local facility funding, without any special grant funding. Furthermore, some districts that continue to operate part‑day programs indicate strong teacher and parent preferences for those programs. For all these reasons, we recommend the Legislature not proceed with an expansion of the grant program at this time. This would free up $750 million in one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund purposes that could be used for key budget priorities (including building higher reserves and making larger supplemental pension payments).

Could Revisit Issue Next Year and Create More Tailored Grant Program. Should the Legislature remain interested in expanding full‑day kindergarten programs through facility grants, it could revisit this proposal in 2020‑21. After receiving and examining all the applications for the initial $100 million in grant funding, the state will have more information about the demand for new facilities among districts running part‑day programs. Were part‑day programs to document unmet facility issues, the Legislature could craft a more narrowly tailored program next year. We recommend any such program direct funds only toward districts currently running part‑day programs due to facility constraints that cannot be addressed through the SFP. We encourage the Legislature to structure any new grant rules such that they do not create incentives to circumvent the SFP or otherwise work at cross purposes with it.

Consider Reducing Part‑Day Per‑Student LCFF Funding Rateif Interested in Creating a Stronger Incentive. The state’s approach to funding kindergarten—providing the same amount of LCFF funding per student for part‑day and full‑day programs—is rare. Normally, the state funds at a lower rate when fewer hours of service are provided. For example, the state provides a notably lower rate for part‑day State Preschool programs compared to full‑day State Preschool programs. To be more consistent with regular state funding practice and provide an even stronger incentive for schools to operate full‑day kindergarten programs, the Legislature could reduce the LCFF part‑day kindergarten funding rate. The part‑day rate, for example, could be reduced by the difference in hours between the average part‑day and full‑day program (about 35 percent). Assuming the 2019‑20 LCFF funding rates in the Governor’s budget, this would equate to about $5,500 in base funding per student in a part‑day program compared to $8,500 per student in a full‑day program.

Reducing Part‑Day Rate Likely Yields Initial Budget Savings, but Raises Important Trade‑Offs. If the Legislature desires to implement a rate reduction for part‑day programs, we recommend it do so over a three‑year period, beginning in 2020‑21. This would allow districts time to consider and plan for any additional full‑day programs. If no district decided to add full‑day programs, the rate reduction would yield roughly $450 million in state savings at full implementation. In contrast, were all existing part‑day programs to convert to full‑day programs by year three, the state would achieve no ongoing savings. (The state would achieve near‑term savings for districts not converting all their programs in year one of the transition.) We think some districts eventually would respond by converting part‑day to full‑day programs, such that the state would achieve some savings but likely far less than $450 million. While reducing the part‑day rate would create a strong fiscal incentive to convert to full‑day programs, we encourage the Legislature to weigh all the pros and cons of full‑day and part‑day programs carefully before changing the associated LCFF funding rates. Given districts report that some parents prefer part‑day programs, the state might not want to create a strong disincentive for districts to offer those programs.

One‑Time Improvement Initiative

In this section, we provide background on the child care and preschool workforce, facilities, and planning. We then describe the Governor’s proposals to provide a total of $500 million one‑time funding to make improvements in these three areas. We end by providing our assessment and making associated recommendations.

Workforce

Child Care and Preschool Workers Must Meet Certain Education Requirements. Child care and preschool workers have requirements they must meet to serve in specific capacities. Most notably, a teacher employed at a child care or preschool center that contracts directly with the state must hold a Child Development Teacher Permit. The permit, which is issued by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, requires 24 units of early childhood education coursework and 16 units of general education coursework. By comparison, the minimum requirement for a teacher employed in other licensed centers in California is a Child Development Associate Credential or a minimum of 12 units of early childhood education coursework. The Child Development Associate Credential is issued by a national nonprofit organization focused on educating and training child care workers. Other child care workers, mostly aides and directors, have different education and experience requirements. Compared to teachers, aides have fewer requirements whereas directors have additional requirements. For example, a director in a center that contracts with the state must have a bachelor’s degree with 24 units of early childhood education coursework, 6 units of administration coursework, and 2 units of adult supervision coursework.

State Funds Many Programs to Educate and Train Child Care and Preschool Workers. Each year the state allocates funds intended to improve the quality of its child care and preschool system. In 2018‑19, it allocated about $50 million specifically for workforce training. These funds are used to support a variety of activities, including coaching and providing stipends to employees attaining more education.

State Has Minimal Workforce Data, Some Information Forthcoming. The state does not collect core data on the child care and preschool workforce. As a result, it lacks information on the number of child care workers, their years of experience, the wages they earn, their educational attainment, and their credentials. Although the state does not collect this information, a few research entities periodically conduct surveys of the child care and preschool workforce. The most recent survey, a national survey conducted in 2012, provides some information for California, such as the educational attainment of its center‑based workforce. The survey does not have a large enough sample to disaggregate California information by region. A new, California‑specific survey is underway that plans to provide both statewide and regional information about the workforce. The study is being funded by a mix of public and private funding. The results of this study are expected to be released in late 2020.

Facilities

Licensed Child Care Facilities Must Meet State Safety Standards. All licensed child care and preschool facilities must meet specific safety standards. For example, playgrounds must be enclosed by a fence that is at least four feet high. To ensure facilities meet state standards, Community Care Licensing (a division in the Department of Social Services) inspects facilities before providers can begin serving children in them. It inspects all existing facilities on a three‑year cycle (with plans to start doing annual visits).

Providers Have Three Common Facility Arrangements. Whether opening a first site or looking to add new sites, providers typically access child care and preschool facilities in one of three ways, described below.

- Lease at Subsidized Rate. Some providers have partnerships with other public entities, such as school districts and cities. These partner entities subsidize providers’ monthly facility costs. In many cases, subsidies are large. For example, some providers pay $1 per year to rent facilities from a city government.

- Own. Some providers own their facilities. In these cases, providers either are making monthly mortgage payments or have paid off their mortgages.

- Lease at Market Rate. Other providers lease space and pay market rent.

Providers Typically Must Cover Cost of Periodic Facility Maintenance and Repairs. Providers typically are responsible for major maintenance and repairs of their facilities. Some facility maintenance is voluntary and preventative, such as replacing a boiler that has come near the end of its useful life. Some repairs are required. For example, Community Care Licensing can require a provider to repair a facility if a safety issue emerges (such as fixing a cracked walkway). Providers might use their reserves, special grant funding, or a facility loan to cover these costs.

State Funds Child Care Facilities Revolving Loan Program to Help With Program Expansion and Maintenance. The state administers a loan program to help providers (1) serve additional children and (2) cover major maintenance and repairs in their current facilities. With state loans, providers could purchase portable classrooms or repair current facilities. In recent years, only a few providers have used the loan program, citing concerns with their ability to repay.

State Has Minimal Information About Facility Arrangements and Overall Maintenance Conditions. The state does not collect data on providers’ facility arrangements. For example, the state lacks basic information on facility ownership and lease costs. The state also lacks information on the major facility maintenance projects that providers have had to undertake in recent years. (Although Community Care Licensing checks to see that providers have remedied safety issues, it does not compile readily available statewide data on repair needs.)

Planning

Local Planning Councils (LPCs) Are Responsible for Ongoing Needs Assessment. Each county has an LPC, with membership selected by the county board of supervisors and county superintendent of schools. Membership consists of parents, providers, public agency staff, and other community representatives. The state provides a total of $3.5 million ongoing funding to LPCs. Each LPC is responsible for conducting a county needs assessment at least once every five years and submitting it to CDE.

Several Special Planning Efforts Have Been Undertaken Over Past Few Years. Over the past several years, numerous workgroups have convened to develop recommendations to improve the child care and preschool system. These workgroups have included policymakers, practitioners, and representatives of state agencies, with support from researchers. One recent workgroup published a set of recommendations for reforming the system’s complex rate structure. Another group, the Assembly Blue Ribbon Commission on Early Childhood Education, began meeting in March 2017 and is expected to release a set of recommendations for improving the system in April 2019. In addition to these workgroups, a group of researchers recently released a series of reports known as Getting Down to Facts II that covered many areas of interest to the Legislature. For example, the series compiled research findings on access to child care, services for young children with special needs, the child care workforce, and alignment with kindergarten.

New Planning Effort Now Underway. The state was recently awarded a Preschool Development Grant totaling $10.6 million in federal funds. With the funds, CDE is examining current levels of access to child care and preschool programs throughout the state. CDE also intends to develop a strategic plan that will identify steps the state could take to improve programs for children from birth through age five. The strategic plan will address topics including access, workforce, and facilities and will be developed in coordination with practitioners and representatives of state agencies. All associated activities are expected to be completed by December 2019.

Governor’s Proposals

Provides Funding for Workforce Development. The Governor’s budget provides $245 million to (1) increase the number of child care and preschool workers and (2) increase the education and training of these workers. CDE is to distribute the funds to each county based upon its relative need for additional child care and preschool workers, the cost of living in each county, and the number of children eligible for subsidized care. Trailer bill indicates the funds would go to one or more “local partners” within each county but does not specify allowable local partners. The administration indicates CDE would have broad discretion to review applications and distribute funding among grantees. Grantees could use funds for educational expenses such as tuition, transportation, and substitute teachers. The $245 million would be apportioned in equal amounts over the next five years ($49 million in each year).

Provides Funding for Facilities Expansion. The budget provides $245 million for facility grants to providers willing to serve additional children. CDE would distribute the funds competitively and prioritize applicants in low‑income communities that have high shares of eligible unserved children and plan to serve those children. Providers could use funds for one‑time infrastructure costs, including site acquisition, facility inspections, or construction management. As with the proposed workforce grant, funds would be apportioned in equal amounts over the next five years.

Provides Funding for Report on Improving Child Care and Preschool System. The budget also provides $10 million for the State Board of Education to contract with a research entity to produce a report by October 2020. The report is to include recommendations on how to improve access and affordability of state subsidized child care and preschool programs. The report also is to include steps the state can take to provide preschool to all children, cost estimates for its associated recommendations, and strategies for prioritizing state funds.

Assessment

Workforce and Facilities Are Key Issues. The Governor’s proposal sets aside funding for important issues in the child care and preschool system. Based on our conversations with providers, workforce development issues (especially retaining staff) and facilities issues (especially covering the cost of repairs) are commonly cited as key challenges.

State Lacks Data to Make Informed Spending Decisions on Workforce and Facilities. The administration’s intention to allocate proposed funds based on need is laudable. The state’s lack of data, however, makes prioritizing based on need difficult. With regard to the workforce proposal, the state does not know what geographic areas need additional child care and preschool workers or what areas would most benefit from additional worker education and training. With regard to the facility proposal, the state does not collect information that would allow it to determine the most significant facility challenge facing providers or the geographic areas experiencing the greatest challenge. The state also does not collect the information that would be necessary to identify cost‑effective options for addressing facility issues. Without this information, deciding how much funding to set aside for each issue area, how to distribute funds across the state, and how to use the funds are all difficult.

State Still Lacks Key Information About Needs of Families. As the state thinks about expanding child care and preschool programs to make them more accessible to families, it may want to better understand families’ child care and preschool needs. Unfortunately, the state collects little information about how the availability of care aligns with the needs and preferences of families. Existing efforts to assess need focus on measuring the existing child care and preschool capacity of geographic regions and comparing them with estimates of the number of families that would be eligible for subsidized programs. However, we are not aware of studies that have focused on measuring what hours eligible families tend to work, what hours they need care, and what factors affect their child care and preschool decisions. This type of information could help the state allocate its slots in a manner that is more preferable and accessible for families. For example, a region with a disproportionate number of families that work evenings or weekends may not benefit as much from additional full‑day State Preschool programs, which tend to operate under a traditional work week schedule.

Another Plan Likely Duplicative of Many Recent Efforts to Improve Child Care and Preschool System. Given the significant number of child care and preschool workgroups, reports, and recommendations that have been produced in recent years (or are currently underway), we believe an additional report in these areas is unnecessary. The Governor’s proposed report likely would make recommendations that overlap significantly with prior reports or planning efforts already underway.

Recommendations

Get Better Information Before Funding New Initiative. Given the state lacks much of the information it needs to address child care workforce and facility issues, the Legislature might want to collect better information over the coming year. Then, over the subsequent few years, it could use one‑time funds in a more targeted and effective way. To this end, the Legislature could set aside some amount of one‑time funding in 2019‑20 into an account designated specifically for future improvement efforts. As it learns more, it could allocate funds from this account as part of the regular budget process.

Fund Studies to Understand Current Facility Arrangements and Access to Child Care. Instead of spending $10 million on another child care plan, we recommend the Legislature designate $1 million each for two focused studies, described below.

- Facility Arrangements. This study would survey subsidized providers and collect information on how they obtained their facility, if they rent or own, the amount of their monthly facility payments, their interest in expanding, and the associated challenges they face. The survey would also collect information on providers’ maintenance issues and how they cover the cost of major maintenance projects.

- Child Care and Preschool Accessibility. This study would survey parents eligible for child care benefits to better understand their needs. The survey would ask parents about the hours they need child care, existing child care and preschool arrangements, and the key considerations affecting their child care arrangements. The survey would attempt to include eligible families currently not receiving child care benefits due to the capped nature of some child care programs.

Align Timing of Studies So They Can Inform 2021‑22 Budget Decisions. For these studies, CDE could run a request for applications from interested research entities. We recommend requiring CDE to award contracts to research entities by October 2019, with the results of the studies available by October 2020. This time frame would ensure all reports (including the forthcoming workforce study) would be available to inform 2021‑22 budget decisions. That year, the Legislature could begin withdrawing funds from the account designated specifically for child care expansion and improvement.

State Preschool

In this section, we provide an overview of the State Preschool program, describe and assess the Governor’s preschool proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Preschool Has Two Key Objectives. State Preschool has part‑day and full‑day options. Both options focus on fostering kindergarten readiness among children from low‑income families, with the full‑day option also helping low‑income, working families with their child care costs. The part‑day program provides at least 3 hours of developmentally appropriate activities per day for 175 days per year. The full‑day program offers between 6.5 and 10.5 hours of care per day for 250 days per year. The amount of care children receive in full‑day programs depends on the hours providers offer services as well as parents’ work or school schedules. Providers choose whether to operate part‑day or full‑day programs, and they determine how many hours per day their full‑day programs operate. We estimate the state in 2018‑19 is serving 103,000 children in part‑day State Preschool programs and 67,000 in full‑day programs.

State Preschool Serves Mostly Four‑Year Olds. The total number of State Preschool slots funded in any given year is determined by the state as part of its annual budget process. Providers must first serve all eligible four‑year olds, with children from the lowest‑income families getting priority. If space remains available, providers may serve three‑year olds—also prioritizing the lowest‑income families. After enrolling all interested and eligible children, providers may enroll children from families who are not income eligible (up to 10 percent of slots). We estimate State Preschool in 2018‑19 is serving 123,000 four‑year olds and 47,000 three‑year olds.

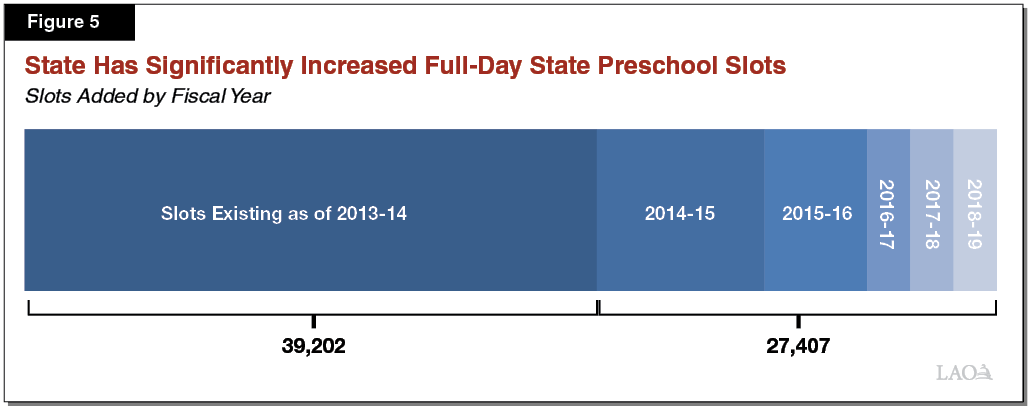

State Has Increased Full‑Day Slots in Each of Past Five Years. The state has significantly increased full‑day State Preschool slots in the past five years. As Figure 5 shows, the state has added more than 27,000 full‑day slots over this period—an increase of 70 percent.

State Also Has Increased Income Eligibility Threshold. Prior to 2017‑18, families were income eligible (for both entering and exiting the program) if they earned below 70 percent of the 2007 state median income (SMI)—$42,216 for a family of three. The 2017‑18 budget package updated the eligibility threshold to the most recent SMI. Currently, families are eligible to enroll in State Preschool if their income is below 70 percent of the 2016 SMI—$54,027 for a family of three. The new policy also increased the threshold for exiting the program. Families can remain enrolled in State Preschool as long as their income is below 85 percent of SMI (currently $65,604 for a family of three). In 2019‑20, families will be eligible to enroll if their income is under 85 percent of SMI. Each income eligibility change in recent years has increased the number of children eligible for State Preschool.

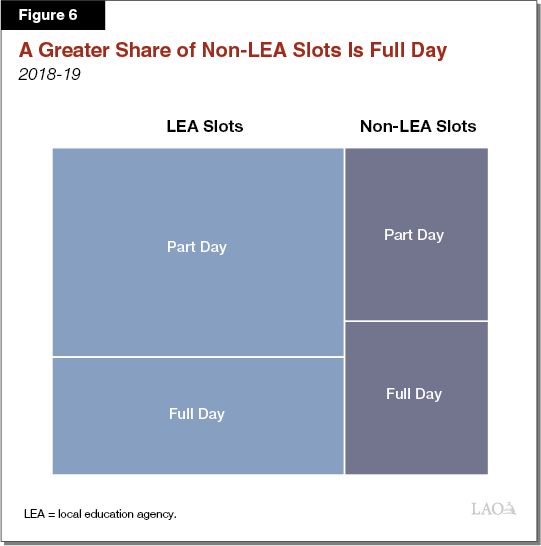

State Preschool Is Offered by Several Types of Providers. State Preschool is offered by various local government and nonprofit agencies. Roughly two‑thirds of State Preschool slots are provided by school districts and county offices of education (local education agencies or LEAs). Nonprofit agencies, county welfare departments, and cities (non‑LEAs) also operate State Preschool, accounting for about one‑third of slots. Of all LEA slots, 64 percent are part day and 36 percent are full day (Figure 6). Non‑LEAs are more likely to operate full‑day programs, accounting for roughly half of their slots.

Funding Source for Full‑Day Programs Varies by Provider Type. In 2018‑19, the state provided $1.3 billion for the State Preschool program—$538 million for part‑day programs and $804 million for full‑day programs. This funding is based on underlying per‑child rates—$5,233 per child enrolled in a part‑day program and $12,070 per child enrolled in a full‑day program. (Providers receive the full‑day rate for any child served between 6.5 and 10.5 hours.) All part‑day State Preschool is funded with Proposition 98 General Fund. All full‑day State Preschool provided by LEAs also is funded with Proposition 98 General Fund. Full‑day non‑LEA programs are funded with a mix of Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund.

Several Other Programs Serve Preschool‑Aged Children. In addition to State Preschool, California has several other subsidized programs that serve preschool‑aged children. Each of these programs has a different set of eligibility and program requirements. Figure 7 compares major aspects of these programs.

Figure 7

Several Programs Serve Preschool‑Aged Children in California

|

California State Preschool |

Contract or Voucher Programsa |

Transitional Kindergarten |

Head Start |

|

|

Eligibility Criteria: |

||||

|

Family income eligibility capb |

70 percent of state median income. |

70 percent of state median income. |

None. |

100 percent of federal poverty level. |

|

Income cap for family of three (2018‑19)b |

$54,027 |

$54,027 |

N/A |

$21,330 |

|

Work requirement |

Yes for full‑day program. |

Yes. |

No. |

No. |

|

Ages of children served |

3‑ and 4‑year olds. |

Under age 13. |

4‑year olds with birthdays between September 1 and December 1. |

Under age 5. |

|

Approximate number of 3‑year old and 4‑year olds served (2018‑19) |

170,000c |

50,000 |

90,000 |

70,000c |

|

Preschool Program Criteria: |

||||

|

Academic content standards |

Developmentally appropriate activities designed to facilitate transition to kindergarten. |

None for voucher programs. Contract programs same as State Preschool. |

Locally developed, modified kindergarten curriculum. |

The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework. |

|

Duration |

At least 6.5 hours per day, 250 days per year for full‑day program. At least three hours per day, 175 days per year for part‑day program. |

Varies based on parents’ work schedules. |

Must operate no fewer than 180 days per year. Hours per day determined by district. |

Determined by local provider. |

|

aIncludes the CalWORKs child care, Alternative Payment, and General Child Care programs. bReflects cap for 2018‑19. Beginning in 2019‑20, cap set to increase to 85 percent of state median income. cMay count children dually enrolled in State Preschool and Head Start. |

||||

Governor’s Proposal

Funds More Full‑Day Slots for Non‑LEAs. The Governor’s budget includes $125 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to provide 10,000 additional full‑day State Preschool slots for non‑LEAs. This expansion is the first of three planned augmentations over the next three fiscal years. The administration intends to provide a total of 30,000 additional slots by 2021‑22, with the intent to serve all low‑income four‑year olds at that time. (The estimate of additional slots needed to serve all eligible four‑year olds is highly sensitive to several underlying assumptions. Depending upon the specific set of assumptions made, estimates of unserved children can vary by tens of thousands.)

Expands Eligibility for Full‑Day Slots. The Governor proposes to eliminate the requirement that families must be working or in school for their children to be eligible for full‑day State Preschool. Under the Governor’s proposal, all three‑ and four‑year olds who meet the income requirements would be eligible for the full‑day program.

Shifts All Funding for Non‑LEAs to Non‑Proposition 98 Side of the Budget. The budget shifts $297 million in State Preschool funding from Proposition 98 General Fund to non‑Proposition 98 General Fund. Under the Governor’s proposal, non‑LEA providers would be funded entirely with non‑Proposition 98 General Fund, while all LEA providers would be funded with Proposition 98 General Fund.

Assessment

Non‑LEAs Generally Have Longer Program Hours. Though the state lacks data on the length of each full‑day program, our conversations with experts in the field suggest that school districts and COEs tend to operate for 6.5 hours per day, whereas non‑LEAs tend to operate 10 hours or more per day. Although the state provides the full‑day rate for 6.5 hour programs, these programs are less likely to address the child care needs of full‑time working parents. Given these differences, providing new slots to non‑LEAs increases the likelihood that these new slots will address working families’ child care needs.

Work Requirement Is Reasonable Way to Prioritize Full‑Day Care. We think retaining the work requirement is the most cost‑effective way of helping the state meet the dual objectives of promoting kindergarten readiness among all low‑income children while helping low‑income working families meet their child care needs.

Governor Does Not Account for Possible Effects of Removing Work Requirement. The Governor’s proposal to remove the work requirement is problematic in a few notable ways. Most notably, the proposal does not account for any resulting behavioral changes—changes that could substantially increase the cost of State Preschool. Though the Governor proposes to allow all children to participate in full‑day programs, he does not build in the higher associated cost of converting part‑day to full‑day slots. A full‑day slot, however, is more than double the cost of a part‑day slot. Were half of part‑day slots to convert to full‑day slots, the cost of State Preschool would be $360 million higher than the Governor’s proposed 2019‑20 funding level. Absent providing additional funding to cover the cost of slots converted from part day to full day, the Governor’s proposal could have the unintended effect of serving fewer children. This is because providers receive preschool contracts for a dollar amount, not a number of slots. Lastly, since all income‑eligible children would become eligible for the full‑day program, working families would compete for full‑day slots with low‑income families where at least one parent stays home. Even at full implementation (once all low‑income four‑year olds are served), a four‑year old from a family with a parent staying at home would receive full‑day State Preschool care while a three‑year old with parents who work would not get a slot.

Non‑LEAs Might Not Be Able to Expand as Quickly as Proposed. If adopted, the Governor’s proposal would increase non‑LEA full‑day slots by about 40 percent in 2019‑20—the largest slot increase earmarked for non‑LEAs to date. By 2021‑22, the Governor’s proposal would more than double the number of non‑LEA full‑day State Preschool slots. Given this would be such a large increase, we think non‑LEAs might be unable to accommodate all 10,000 new slots in 2019‑20. Although non‑LEAs filled all available slots when slots were last earmarked for them (in 2015‑16), they received a much smaller number of additional slots (1,200) that year. Such a large one‑year slot increase also may be difficult for CDE to administer. To award new slots to providers, CDE must provide technical assistance and review applications from hundreds of providers. An expansion of this magnitude would create a much higher volume of workload than previous, less ambitious expansions.

Slots Cannot Be Used Until Midyear. We also think any new State Preschool slots likely cannot be filled until the middle of 2019‑20. To award slots, CDE must first develop a request for applications, review applications, and decide which applications to fund. Providers who are awarded additional slots must then make facility arrangements, make necessary repairs, have their facilities approved by Community Care Licensing, hire staff, conduct outreach, and enroll children. Given these challenges, we think new slots realistically could not be used before January 1, 2020.

Additional Facilities a Key Issue. Accommodating new State Preschool slots is likely to entail various challenges, including finding and paying for additional facilities. To expand, providers must first identify available facilities that could be suitable for operating a preschool program. This might entail developing partnerships with nearby school districts, cities, county groups, or real estate experts. Once a facility is identified, a provider must then complete certain steps before the facility can operate a State Preschool program. These steps can entail working with the city regarding the zoning requirements of the property, making renovations and repairs, and ensuring the facility is reviewed and approved by Community Care Licensing. These issues can be particularly difficult for small providers that may lack the administrative capacity to manage a new facility project.

Using One Fund Source Has Benefits. Shifting all non‑LEA State Preschool funding to one fund source provides administrative flexibility for non‑LEA providers and CDE. Non‑LEA providers would be able to shift funding between their various CDE contracts—part‑day State Preschool, full‑day State Preschool, and General Child Care—to best serve families in their communities. Since a portion of full‑day State Preschool is currently funded with Proposition 98 General Fund, providers currently are unable to shift funding between full‑day and part‑day programs. The additional flexibility offered by the Governor’s proposal also simplifies the contracting process for CDE, as it is no longer required to verify that providers have maintained separate accounting of their Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98‑funded programs.

State’s Patchwork of Preschool Programs Is Poorly Designed. The state has a complex system of preschool programs that lacks coherence. Most notably, the largest school‑run program—Transitional Kindergarten—has no income eligibility requirements and does not address the child care needs of working families. The state’s voucher programs, which are designed to meet families’ child care needs, do not require programs to have an academic or developmental component. This complex patchwork of programs also can be difficult for families to understand and navigate. Some programs, for example, accept all eligible children, while other programs have waiting lists or have a fixed set of services that may not necessarily meet families’ needs.

Recommendations

Fund Fewer New Slots in 2019‑20, Start Them Midyear. We suggest the Legislature add 2,500 new non‑LEA slots beginning January 1, 2020. This is roughly a 10 percent increase from the full‑day slots non‑LEAs currently provide, and more than twice the number of slots provided to non‑LEAs in 2015‑16. This increase provides a significant number of new slots for non‑LEAs, while recognizing the logistical challenges of expanding quickly. Starting the slots midyear gives CDE time to review and approve applications, while giving providers time to find facilities, get their facilities licensed, hire additional staff, and enroll children. An additional 2,500 slots beginning January 1, 2020 would have a half‑year cost of $16 million in 2019‑20, growing to a full‑year cost of $31 million in 2020‑21. In future years, the Legislature could decide how many new slots to approve based on the take‑up in 2019‑20.

Keep Work Requirement and Give New Slots to Providers Operating at Least a 10‑Hour Day. To ensure full‑day State Preschool slots are available to address the needs of working families, we recommend maintaining the requirement that parents be working or in school. Removing the work requirement would result in some children from families where one parent stays at home receiving priority for full‑day programs over other children from families with child care needs. Additionally, we recommend prioritizing new slots to non‑LEAs that agree to operate at least 10 hours per day. This would ensure that new slots meet the needs of parent(s) working full time.

Provide Ongoing Funding to Assist With Facility Expansion. To increase the take‑up of new State Preschool slots, we recommend providing $4 million in ongoing funding to assist providers with facility expansion. For 2019‑20, we recommend having CDE distribute the funding among LPCs based on the county’s population of low‑income children under five. In the future, the state could use data from CDE’s forthcoming needs assessment to distribute funding based on each county’s unserved preschool population. With the funds, we recommend requiring LPCs to have a facility specialist who supports providers interested in finding additional facilities. (Our estimate assumes one full‑time facility specialist for each large county and a portion of a specialist’s time for smaller counties.) These facility specialists could work with local governments to address local zoning ordinances and other local issues serving as barriers to using facilities for child care and preschool. Given LPCs already are intended to serve a key planning role and include representation from an array of stakeholders, we think they are well positioned to help plan and provide support related to facilities.

Support Non‑LEAs Slots From One Fund Source. This change allows more flexibility for non‑LEA providers to use slots in a way that best meet families’ needs. This change also simplifies contracting for the state and providers. The Legislature could go further and fund all State Preschool for all providers from one fund source, thereby offering more flexibility for LEAs too.

Over Coming Year, State Could Design One Program That Better Met Two Core Goals. To better meet the core goals of fostering kindergarten readiness and meeting the child care needs of low‑income families, the Legislature may want to consider consolidating state funding for all existing preschool programs into one program. The state could build off the structure of the existing State Preschool program, which assures all participating children receive at least three hours of developmentally appropriate activities and also provides wrap care for working families. To improve the convenience for families and increase the likelihood that all low‑income children can participate, the state could also require providers to offer programs year‑round, operate at least 10 hours per day, and have flexible start times for part‑day programs.

CalWORKs Child Care

In this section, we provide background on CalWORKs child care. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to augment CalWORKs child care funding by $103 million to reflect increases in caseload and cost of care. We end by providing our assessment and associated recommendations.

Background

State Provides Subsidized Child Care to CalWORKs Participants. CalWORKs provides cash grants and employment services to low‑income families with children. Under the program, parents who work or are in school qualify for subsidized child care benefits. Parents may progress through three CalWORKs child care stages. Families are considered to be in Stage 1 when they first enter CalWORKs. Once CalWORKs families become stable (as determined by the county welfare department), they move into Stage 2. Families move into Stage 3 two years after they stop receiving cash aid. They can continue receiving subsidized care until their income exceeds 85 percent of the SMI or their child ages out of the program (turns 13 years old). At the state level, Stage 1 is administered by the Department of Social Services, while Stages 2 and 3 are administered by CDE. The 2018‑19 Budget Act included $1.3 billion in combined state and federal funding for CalWORKs child care, with an estimated 137,000 children being served.

CalWORKs Child Care Providers Are Reimbursed Based on Regional Market Rates (RMR). Reimbursement rates for CalWORKs child care providers vary by county. The rates are based on a regional market survey of a sample of licensed child care providers. The state conducts a survey of regional market costs every two years. Currently, the state links the RMR to the 75th percentile of the 2016 survey (the most recent one available). This ensures that all families have access to at least three‑quarters of their local child care providers. Chapter 29 of 2016 (SB 858, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) included intent language to reimburse child care providers at the 85th percentile of the most recent survey (although the state to date has not funded at this higher level). CDE expects to release the results of the 2018 survey in April 2019.

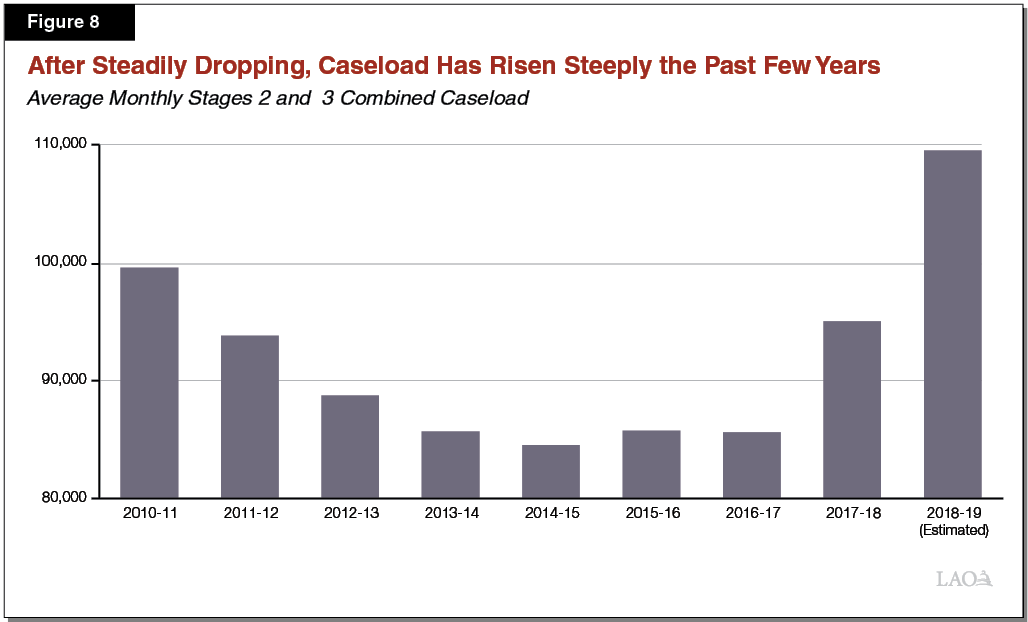

CalWORKs Stages 2 and 3 Caseload Declined Throughout Much of the Economic Recovery. Figure 8 shows Stages 2 and 3 caseload from 2010‑11 to 2018‑19. Consistent with overall CalWORKs program enrollment, CalWORKs child care caseload declined during the state’s economic recovery. In 2017‑18, however, caseload began increasing and 2018‑19 caseload is projected to exceed the 2010‑11 level. We describe the factors contributing to this recent increase below.

State Made Two Changes That Significantly Increased Stages 2 and 3 Caseload. In 2017‑18, the state made changes to income eligibility criteria and a key family reporting requirement. These changes significantly increased Stages 2 and 3 caseload. Although these changes apply to Stage 1, the effects were less notable for that stage due to its additional participation requirements.

- Income Eligibility. Under the new policy, families are eligible to enroll in subsidized child care if their income is below 70 percent of the 2016 SMI—$54,027 for a family of three. Families can continue receiving benefits as long as their income is below 85 percent of SMI ($65,604 for a family of three). Previously, to be income eligible (for both entering and exiting the program), parents were required to earn below 70 percent of the 2007 SMI ($42,216 for a family of three).

- Family Reporting Requirement. Families now must report information necessary for determining eligibility only once a year unless changes in income make them ineligible. Previously, families were required to report any change in income or work hours within five days.

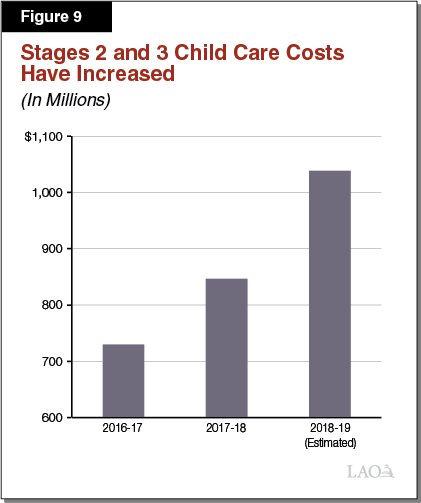

Cost for Stages 2 and 3 Has Significantly Increased In Recent Years. As Figure 9 shows, the combined cost of CalWORKs Stages 2 and 3 has grown from $714 million in 2016‑17 to more than $1 billion in 2018‑19—an increase of 45 percent across the period. The increase is primarily due to higher caseload but the cost per child also has increased as a result of the state updating to the 2016 RMR survey.

Governor’s Proposal

Makes Adjustments for Changes in CalWORKs Child Care Caseload and Average Cost of Care. The budget includes a net increase of $103 million to reflect changes in CalWORKs caseload and cost of care. This includes a combined $119 million increase in Stages 2 and 3 costs, partly offset by a $16 million decrease in Stage 1 costs. The decrease in Stage 1 is due to a decline in overall CalWORKs participation resulting from an improved economy.

Administration Requested Additional Funding to Cover Current‑Year Shortfall. The administration projects an $80 million shortfall in Stages 2 and 3 in 2018‑19, largely due to higher caseload. The administration recently notified the Legislature of the shortfall and provided a current‑year augmentation to cover it. The administration built the higher costs into its 2019‑20 budget (that is, $80 million of the $103 million increase noted above is associated with higher 2018‑19 costs).

Assessment and Recommendation

Legislature May Want to Budget More Funding in 2019‑20. The administration assumes caseload will increase 3 percent in 2019‑20. Given the substantial year‑over‑year caseload growth in recent years, the Legislature may want to budget more funding in the event caseload grows more quickly than the administration assumes. Budgeting initially at a higher level would minimize the chance the state has to use reserves to cover higher costs down the road. It also would prevent the state from having to disenroll children midyear if additional funding is unavailable. If 2019‑20 caseload were to increase 9 percent—triple the rate the administration assumes but still lower than growth the past two years (11 percent and 15 percent, respectively), the Legislature would need to provide an additional $33 million to cover Stages 2 and 3 costs.

Administration’s Cost Estimates Do Not Include Updating Rates for 2018 Survey Results. The administration continues to base its cost of care estimates on the 75th percentile of the 2016 survey. Given CDE expects to release new regional market survey results this spring, the Legislature may be interested in updating provider reimbursement rates. Based upon the state’s recent experience with survey‑based rate increases, updating survey rates in 2019‑20 likely would cost in the tens of millions.

Summary of Recommendations

Full‑Day Kindergarten Expansion

- Reject the Governor’s 2019‑20 proposal to provide $750 million in one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for more kindergarten facility grants. Based upon first‑round grant applications, the program is not likely to notably advance the state’s objective of increasing the number of full‑day kindergarten programs.

- Examine all the applications received this year to determine the extent to which districts running part‑day programs require additional facility funding to convert to full‑day programs.

- If the Legislature would like to provide more facility grants in 2020‑21, consider creating a more targeted program. Focus the new program on districts currently operating part‑day programs due to facility constraints. Structure any new grant rules such that they do not create incentives to circumvent the School Facility Program or otherwise work at cross purposes with it.

- If interested in creating an even stronger incentive for full‑day programs, consider reducing the part‑day per‑student kindergarten rate under the Local Control Funding Formula over a three‑year period. Before lowering the part‑day rate, weigh the trade‑offs of full‑day and part‑day programs carefully, as some parents prefer to send their children to part‑day programs.

One‑Time Improvement Initiative

- Hold off on spending $500 million from the Governor’s one‑time initiative given the state lacks key data to make informed spending decisions about the child care workforce and facilities.

- Consider setting aside some amount of one‑time funding in a new account specifically for future child care expansion and improvement efforts.

- Designate $2 million for two studies ($1 million for each study), instead of spending $10 million on a plan. Authorize one study to survey child care providers’ on their facility arrangements and another study to survey eligible families on their child care needs. Require the results of both studies to be submitted to the Legislature by October 2020 (the same time the results of a workforce survey are expected).

- Use the set‑aside funds starting in 2021‑22 to address specific challenges identified in the forthcoming studies.

Full‑Day Preschool Expansion

- Add 2,500 full‑day State Preschool slots for non‑local education agencies starting January 1, 2020, instead of the 10,000 slots starting July 1, 2019 as proposed by the Governor. This option would cost $16 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund in 2019‑20, instead of the $125 million the Governor proposes.

- Reject the Governor’s proposal to eliminate the requirement that parents must work or be in school to be eligible for full‑day State Preschool. Retaining the requirement ensures full‑day State Preschool is available for working parents.

- Require the California Department of Education to prioritize expansion funding for providers agreeing to operate at least 10 hours per day. This also ensures full‑day State Preschool is available for working parents.

- Provide $4 million ongoing to local planning councils so each has a facility specialist that assists providers in identifying facility options.

- Approve the Governor’s proposal to shift $297 million in State Preschool funding from Proposition 98 General Fund to non‑Proposition 98 General Fund.

- Consider funding all State Preschool from one fund source to give providers maximum flexibility in serving families.

CalWORKs Caseload and Cost of Care

- Consider providing more funding than in the Governor’s budget to cover potentially higher Stage 2 and 3 caseload. The Legislature would need to provide an additional $33 million if Stage 2 and 3 caseload were to increase 9 percent in 2019‑20—lower growth than the past two years but triple the growth the administration assumes.