March 6, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Tax Conformity

- Introduction

- Background

- Major Income Tax Provisions Affected By 2017 Changes

- Considering Income Tax Conformity

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Other Potential Conformity Provisions

Summary

Recent Federal Tax Changes Created New Differences Between State and Federal Tax Laws. The 2017 federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made significant changes to federal tax laws. Generally, the federal tax changes reduced tax rates and broadened the tax base (what is subject to tax). Because the state’s income tax laws closely refer to large portions of federal law, many of those changes created new differences between federal and state taxes. State law currently does not adopt—or conform to—any of the federal changes made in 2017.

Governor Proposes Conforming to Portions of the Federal Changes. The Governor proposes conforming to several provisions of the 2017 federal tax law. These include limits on noncorporate business losses, increased flexibility for small business accounting, changes to like‑kind exchanges, eliminating net operating loss (NOL) carrybacks, limits on fringe deductions, and other—generally smaller—provisions. (Under the Governor’s updated proposal provided to us March 1, 2019, conforming to these provisions would increase revenue by $1.7 billion in 2019‑20. These estimates are very uncertain, however.) The Governor’s proposal for conformity is tied to an expansion of the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). (We view federal tax conformity as a distinct policy issue and discuss the proposed EITC expansion in a separate report.)

Evaluate Merits of Conformity on Case‑by‑Case Basis. While closer conformity between state and federal tax laws provides some benefits, California’s tax laws historically have differed from federal law in various ways. Should the Legislature consider conforming to portions of the recent federal tax law, it will want to consider the merits of conforming to each of the major provisions independently. We lay out the questions to consider for each provision in Figure 3.

LAO Assessment of Major Provisions. We identify ten major provisions the Legislature could consider for conformity actions (five of these are part of the Governor’s proposal, which total $1.6 billion in estimated revenue in 2019‑20). In each case, we discuss which filers may be affected by conforming, the arguments in favor of conforming, and the arguments against. In some cases—like limiting noncorporate business loses and modifying NOLs—we find the arguments in favor of conforming are stronger than those against conforming. In other cases, we find the opposite or we find there are good arguments on both sides. We summarize these findings in Figure 4.

Introduction

A December 2017 federal law (known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) made many changes to the federal personal income tax (PIT) and corporation tax (CT). The state has not yet taken action to address those changes—a practice known as “conformity.” The Governor’s budget proposes conforming state tax laws to some provisions of the new federal law to offset the cost of a proposed expansion to the state EITC. This report describes the major changes to federal tax laws and provides a framework for assessing potential conformity actions. (Because we view federal tax conformity as a distinct policy issue from an EITC expansion, we analyze that proposal in a separate report.)

Background

Overview of Income Taxation

Income taxes are an important source of federal and state government revenue. In California, PIT and CT are two of the largest state taxes. The PIT contributes over two thirds—$93.5 billion in 2017‑18—of state General Fund revenue. CT collections in 2017‑18 were $12.3 billion. The rest of this section describes the basics of income tax law as they relate to each step that tax filers follow as they prepare their tax returns.

Federal Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). When tax filers prepare their tax returns, they begin by adding up all of their taxable income. For the most part, the definition of income is the same under federal and California laws. A filer’s total income is referred to as “adjusted gross income” or AGI. In addition to wage income—which is reported as earnings by more than 80 percent of federal tax filers—other sources of income include capital gains; business income; interest; dividends; and distributions from pensions, annuities, and retirement accounts. About 20 percent of filers have business income and 17 percent of filers have capital gains income. Capital gains or losses result from the sale of an asset, such as shares of a company’s stock or real estate property.

Differences Between State and Federal Definitions of AGI. There are a few differences between the state and federal definitions of AGI. For instance, California does not tax Social Security income. On net, these adjustments resulted in California tax filers’ state AGI being about 2 percent lower than their federal AGI in 2016.

Standard Deduction. Deductions are provisions of tax law that reduce filers’ taxable income. Filers must choose between two different options for taking deductions—the standard deduction or itemized deductions. About two‑thirds of Californians claimed the standard deduction in 2017. Partly due to the 2017 federal law, the federal standard deduction is much higher than the state standard deduction. For tax year 2018, the federal standard deduction is $12,000 for single filers and $24,000 for married couples filing jointly. The corresponding state amounts are $4,401 and $8,802 respectively. (Prior to 2018, the federal standard deduction was $6,350 for single filers and $12,700 for married couples filing jointly.)

Itemized Deductions. As an alternative to taking the standard deduction, filers may claim one or more other deductions—known as itemizing. For example, filers who itemize may take PIT deductions for home mortgage interest. Filers typically choose to itemize their deductions if the sum of these deductions is greater than the standard deduction.

PIT Tax Rates. After filers apply deductions, they compare the resulting taxable income to a schedule. This schedule tells them how much tax they owe (called “tax liability”) before they apply credits (described below). This schedule is based on a structure of marginal tax rates—rates that apply incrementally to each additional dollar of income. Both the federal and state PIT use graduated rate structures, meaning that the marginal rate increases as the filer’s income increases. Figure 1 shows the state’s marginal rate structure for tax year 2018.

Figure 1

California Marginal Personal Income Tax Rates

Single Filer, 2018

|

Taxable Income Over: |

But Less Than: |

Marginal Tax Rate |

|

— |

$8,545 |

1.0% |

|

$8,544 |

20,256 |

2.0 |

|

20,255 |

31,970 |

4.0 |

|

31,969 |

44,378 |

6.0 |

|

44,377 |

56,086 |

8.0 |

|

56,085 |

286,493 |

9.3 |

|

286,492 |

343,789 |

10.3 |

|

343,788 |

572,981 |

11.3 |

|

572,980 |

— |

12.3 |

Credits. A credit reduces a filer’s tax liability directly (as distinct from deductions, which reduce the filer’s taxable income). While some state credits—like the EITC and low‑income housing credits—are based on or refer to federal tax laws, others are different. For instance:

- Federal law provides a credit for 30 percent of the cost of qualified residential energy savings improvements, such as solar water heaters and geothermal heat pumps.

- State law provides a credit for 15 percent of the value of fresh fruits or vegetables donated to California food banks.

Taxes on Business Income. Business income can be earned by individuals or businesses (like corporations). Most filers with business income begin by adding up their revenue and then deducting their businesses expenses. (In some years, businesses experience a net loss, which we discuss below.) State and federal tax laws include specific accounting rules to calculate business income and deductions. These rules vary somewhat among individuals and different types of businesses. Federal and state rules also differ. Broadly, any expense that is not directly related to generating income is not deductible. Deductions for some types of business expenses—like meals with clients—are limited. After these calculations are complete, business owners include this amount in their AGI. Corporate filers apply a flat tax rate—8.84 percent in California—to this income.

NOL Deductions Smooth Business Profits and Losses Over Time. When business expenses exceed revenue in a particular year, a corporation has a NOL. The value of a NOL is equal to the amount by which allowable expenses exceeded revenue. The corporation can then deduct the NOL from its taxable income the following year, reducing that year’s tax liability. Corporations can carryforward NOLs—apply them to a future year’s earnings—for up to 20 years. State law also allows corporations to “carryback” NOLs—apply them to a previous year’s earnings—for up to two years. Overall, NOLs allow corporations to smooth profits and losses over time.

Federal Tax Laws Changed in 2017

Generally Reduced Tax Rates . . . The 2017 federal tax law reduced effective tax rates for many filers. (The effective tax rate is the total amount of tax divided by the taxpayer’s gross income.) In particular, the law:

- Replaced the previous CT rate structure with a flat 21 percent tax rate.

- Reduced PIT rates slightly.

- Doubled the standard deduction and created a new 20 percent deduction for business income for individuals.

- Raised the income threshold for the alternative minimum tax and eliminated the corporate alternative minimum tax.

. . . And Broadened Tax Base. In addition to the effective rate changes described above, the 2017 law made other changes that broadened the tax base—that is, reduced or eliminated various credits and deductions. Examples of these changes include eliminating personal exemptions, ending many individual and business deductions, and imposing new limits on other common deductions. The law also made significant changes to federal taxes for multinational corporations.

Many Changes Are Temporary. Many of the major changes to federal PIT law are effective only for tax years 2018 through 2025. Many of the changes to federal taxes on business income, however, are permanent.

States Often Conform to Federal Changes, at Least in Part

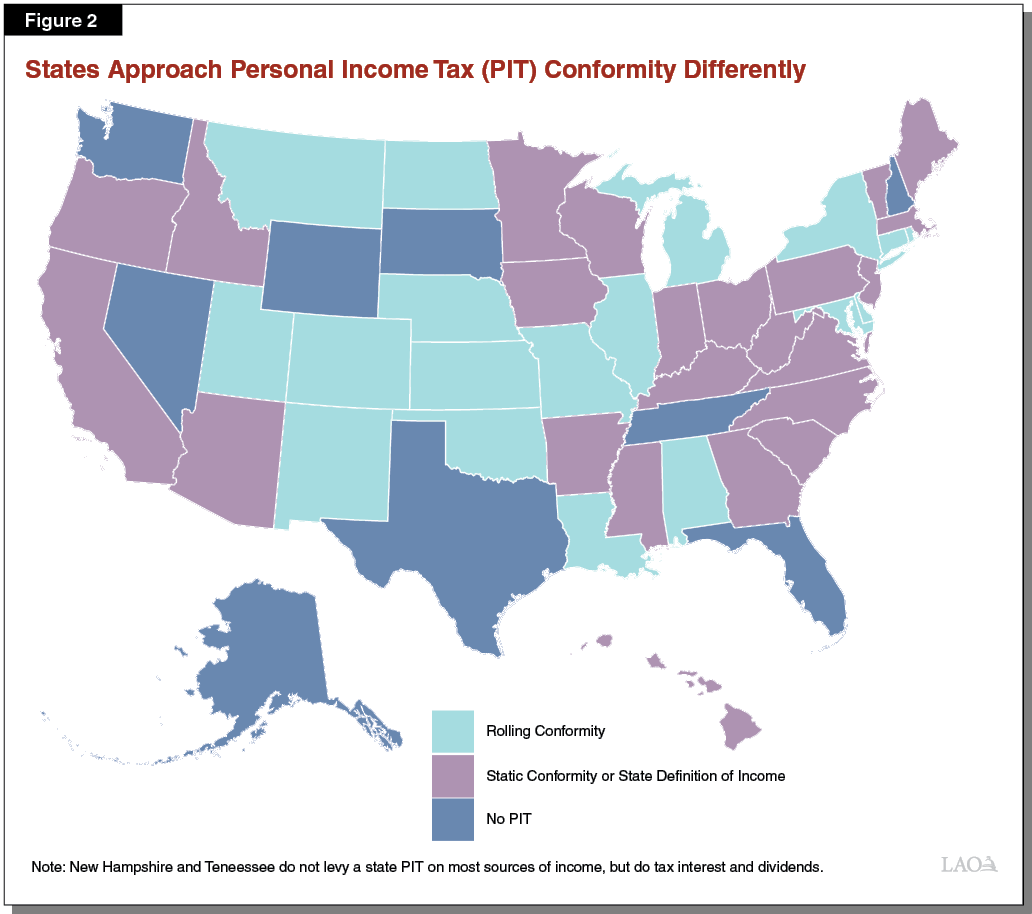

States Take Different Conformity Approaches. Many states’ income tax laws refer to or otherwise incorporate federal tax laws. When federal tax laws change, the tax laws of some states automatically conform to the change. (This is sometimes called “rolling conformity.”) Other states reference the federal law as of a particular date. If such states wish to conform to subsequent changes in federal law, their Legislatures must update the “static conformity” date in their tax laws. As we show in Figure 2, PIT laws in 19 states conform automatically and 23 must act to conform their PIT laws. (Nine states do not have a PIT.) If a state with rolling conformity does not want to conform to any particular provision, their Legislatures must pass laws to specify the difference.

Recent Conformity Actions. In 2018, most states that levy a state PIT took some legislative action to conform to the federal changes made in December 2017. While some states adopted most of the changes, other states updated their conformity dates in state law—for example, New York on a rolling basis and Virginia on a static basis—but decoupled from many of the major federal changes. Only Arizona, California, and Minnesota have not acted in response to the federal changes.

Generally, Closer Conformity Facilitates Compliance and Enforcement. States conform to the federal tax code for several reasons. By using the federal definition of income as a starting point to calculate state tax liability, states may reduce the compliance burden on tax filers and reduce errors. Additionally, referring to federal tax laws allows state administrators and filers alike to rely on federal regulations, judicial rulings, and tax filer guidance from the Internal Revenue Service. The federal interpretations generally are more detailed and extensive than what any individual state could produce. Furthermore, conformity provides consistency among states’ tax laws. This benefits those filers who pay taxes in multiple states and reduces the effects of tax policy on taxpayer behavior. Lastly, conformity enhances state compliance activities by allowing states to benefit from federal tax filer audits and use federal tax data.

California’s Federal Tax Conformity

In this section, we describe key similarities and differences between federal income tax laws and California’s tax laws as they currently stand.

Definition of Income, Many Deductions Similar. As noted earlier, the state’s tax laws are based on federal definitions of income. For instance, the state’s calculation of income begins with federal AGI. In addition, most state itemized deductions conform to similar federal rules.

State PIT More Progressive. California’s PIT historically has differed from federal law in significant ways. For example, the state provides credits to filers and their dependents in place of the federal personal and dependent exemptions (which are similar to deductions). In addition, the state taxes income under a more progressive rate structure and provides significant personal and dependent credits. Consequently, roughly 1.5 million Californians earning between $10,000 and $50,000 owe federal taxes but do not owe any state tax. In addition, the highest‑income California filers pay a proportionally larger share of their income in state taxes, relative to other filers, than they do in federal taxes.

Some State CT Rules Differ Significantly. The state taxes multinational businesses in a fundamentally different way than the federal government. These differences largely apply to how corporations file taxes and the rates applied to different types of corporations. Despite these significant differences, state CT laws conform closely to other federal tax laws regarding how and when corporations account for certain kinds of income and expenses for tax purposes.

Other Differences Reflect Different State and Federal Priorities. California has historically not conformed to certain federal provisions due to differences in policy priorities. This approach is sometimes called “selective conformity.” For example, California treats employer reimbursements for ridesharing and bicycling expenses more generously than federal law to provide a stronger incentive for alternative modes of commuting to work. Federal tax laws were changed in 1986 to increase how quickly businesses could deduct the cost of major new assets to provide a stronger incentive for business investment and California only partially conformed to those changes in PIT law. (California did not conform CT law to these changes and provides different incentives for business investment.)

Last Major Tax Conformity Action in 2015. Following the last major overhaul of the federal tax laws in 1986, California passed legislation in 1987 to selectively conform to federal changes by changing the specified date of conformity, affirmatively conforming or partially conforming to some provisions, and specifically not conforming to certain other federal changes. In addition, this legislation also reduced state tax rates, increased the personal exemption credit, and increased the standard deduction. The state Legislature has sometimes passed conformity legislation several years after changes in federal law. For example, the most recent major tax conformity change was Chapter 359 of 2015 (AB 154, Ting), which changed the specified date of conformity from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2015.

Major Income Tax Provisions Affected By 2017 Changes

We describe the most significant federal conformity provisions below. We classify these as “conformity provisions” because California’s tax laws historically have conformed to these parts of federal law. Other major changes to federal tax laws are entirely new or reference provisions to which California historically has not conformed. For instance, given the fundamental differences in how California taxes multinational corporations, we do not consider those federal changes conformity items. (The Franchise Tax Board [FTB], which administers state income tax laws, annually prepares a Summary of Federal Income Tax Changes. This annual report provides full descriptions of all the federal conformity items and details all of the technical conformity implications of each federal change.) At the end of this report, we include an appendix that briefly describes a number of other 2017 federal changes to which the Legislature could consider conforming. These provisions affect few filers or do not have a significant fiscal effect. Generally, these provisions do not run afoul of existing state tax policy.

The Governor proposes conforming to five of the major provisions described below. These are (1) limits on noncorporate business losses, (2) increased flexibility for small business accounting, (3) changes to like‑kind exchanges, (4) eliminating NOL carrybacks, and (5) limits on fringe benefit deductions. The Governor also proposes changes to some other—generally smaller provisions—which we describe in the appendix. Lastly, the Governor proposes providing tax benefits for investments in “Opportunity Zones.” We do not consider Opportunity Zone tax benefits a conformity issue, but describe the implications in the nearby box. (This report reflects the Governor’s updated conformity proposal we received March 1. The administration estimates its proposal would raise $1.7 billion in 2019‑20—$700 million more than the January proposal. As we discuss later, however, these estimates are highly uncertain.)

Opportunity Zones

Certain Economically Distressed Areas Identified as Opportunity Zones. The 2017 federal tax changes established Opportunity Zones to increase investment in certain economically distressed areas. States had discretion to identify Opportunity Zones based on federal guidance. Generally, these are areas with relatively low median income and high levels of unemployment. In California, the state Department of Finance—with public input—identified 879 census tracts as Opportunity Zones.

Federal Changes Provide Significant Tax Benefits for Investments in Opportunity Zones. To encourage investment in Opportunity Zones, federal law allows filers to defer taxes on capital gains if those profits are invested in Opportunity Zones. In addition, if filers hold on to the investment for multiple years, their tax liability on those capital gains can be reduced. Lastly, filers that maintain their Opportunity Zone investment for at least ten years will not be taxed on the eventual sale of that investment.

Administration Proposes Adopting Opportunity Zone Tax Benefits for Specific Investments. In budget summary documents, the administration proposed to allow similar state tax incentives for “green technology” or “affordable housing” investments in Opportunity Zones. The administration has not provided any details regarding this proposal.

State Opportunity Zone Tax Benefits Unlikely to Be Effective. Federal tax law typically influences people’s choices more than state tax law because the federal rates are higher. Consequently, creating a state tax benefit for Opportunity Zone investments—on top of the significant federal incentive—likely would not significantly influence decisions about where to invest. Any state tax benefit provided would be a “windfall” to investors because they likely would have made the investment even without the state benefit. Moreover, if the federal tax incentive is insufficient to encourage investment in affordable housing and green technology, a similar state tax benefit likely would not change investors’ choices.

Provisions Affecting Individuals

Limits Noncorporate Business Losses. In some years, the costs of running a business exceed its gross income, resulting in a loss. Filers generally can deduct business losses from other sources of income. (To prevent abuses, there are limitations on the type of business losses a filer may deduct.) The 2017 federal law limits such deductions to $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples). Business losses in excess of that amount become a NOL, which the filer may deduct from income the following year. About 700,000 California PIT filers had a business loss in 2016, but there likely were fewer than 100,000 with other sources of income in excess of $250,000.

Suspends Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions. Federal PIT law previously allowed filers who itemized their deductions to deduct “miscellaneous” expenses, including (1) unreimbursed work‑related expenses, (2) tax preparation fees, and (3) certain other expenses related to earning income. Common work‑related expenses include protective equipment, training, and transportation. Filers could previously deduct miscellaneous expenses in excess of 2 percent of their AGI. The 2017 federal law suspended this deduction until 2026. The change likely will affect about 2 million California filers—about 12 percent—who claimed the deduction in previous years. The change disproportionately affects filers with incomes between $75,000 and $200,000, as lower‑income filers are less likely to itemize their deductions and higher‑income filers face more limits on these deductions.

Limits Mortgage Interest Deduction. PIT filers generally cannot deduct personal interest payments. Mortgage and home equity loan interest, however, are exceptions (within certain limits). The 2017 federal changes reduced the amount of mortgage interest PIT filers can deduct. Prior to the changes, filers could deduct the interest from up to $1.1 million in combined mortgage and home equity debt. Under the new law, this limit is reduced to $750,000 for new mortgage debt. In addition, interest on home equity loans is deductible only if the loan proceeds are used for home improvements. Nearly one‑quarter of tax filers in California claim the mortgage interest deduction. Tax filers who buy or refinance a home after December 15, 2017—especially if they live in one of the state’s more expensive real estate markets—will be most affected. A filer with a new mortgage of more than $1 million could see their federal tax liability increase by more than $4,000 per year. (Roughly 15 percent of California homes sold cost over $1 million. Consequently, this change is unlikely to affect most California homebuyers.)

Limits State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction. Federal law allows taxpayers to deduct a broad range of state, local, and foreign taxes. The 2017 federal changes now limit the total amount that may be deducted under this provision to $10,000. (Businesses and corporations are not affected by this limit.) The vast majority of filers who itemized their deductions in 2016—about 30 percent of all federal filers in California—claim a deduction for state income taxes and local property taxes. Given the increase to the federal standard deduction, we expect that many fewer filers will itemize their deductions in 2018 than in previous years. As a result, fewer Californians will take the SALT deduction on their federal taxes.

Suspends Limit on Itemized Deductions. Federal PIT law previously limited the total amount of itemized deductions for higher‑income tax filers (those above $261,500 for single filers and $313,800 for married filing jointly in 2017). The 2017 federal law suspended the federal limit on itemized deductions, mostly affecting the deductions for mortgage interest and charitable contributions. (Certain deductions were exempt from the limit, including medical expenses and losses from casualty and theft.) Most tax filers with incomes above the threshold—about 5 percent of California filers—itemize their deductions and this change will likely reduce their taxes.

Provisions Primarily Affecting Businesses

Limits Interest Deduction. Corporations and other business entities generally can deduct interest payments from their income. The 2017 federal changes limit the deduction of interest to 30 percent of a filer’s “adjusted taxable income.” Interest expenses above 30 percent of income can be carried forward and deducted the following year. There is insufficient data on how many businesses that claim deductions for interest will be affected by the new limit. (Small businesses with revenue under $15 million and utilities are exempt.)

Modifies NOLs. The 2017 federal changes modified the NOL provisions in three ways: (1) limits NOLs to 80 percent of income, (2) allows NOLS to be carried forward indefinitely, and (3) eliminates NOL carrybacks. Previously, a filer with a sufficient amount of NOLs could reduce their taxable income to $0. Now, a filer may only reduce their taxable income by 80 percent. NOLs can now be carried forward indefinitely instead of expiring after 20 years. The new limit on NOLs’ use could affect roughly 100,000 PIT filers and 100,000 CT filers annually. While filers with NOLs might pay more in taxes in the current year, they would pay less in future years.

Restricts Like‑Kind Exchanges. Tax filers may defer paying PIT and CT on capital gains from sales of certain types of property if they purchase a similar type of property within 180 days. The 2017 federal changes restricted these “like‑kind exchanges” rules to apply only to real estate. As a result, tax filers who sell certain other types of tangible or intangible assets—such as vehicles, artwork, collectibles, franchises, and patents—may no longer defer paying tax on their capital gains through like‑kind exchanges. Real estate has historically accounted for most like‑kind exchanges.

Limits Deductions for Fringe Benefits. While most business expenses—including employee compensation—are deductible, there are various restrictions and limits on the deductibility of business spending on “fringe benefits.” Fringe benefits are things like health benefits, employer‑provided or reimbursed meals, and parking. The 2017 federal changes modified some of the existing restrictions and limitations on fringe benefits. These changes likely will reduce the amount of deductions that many corporations and businesses will be able to claim.

Increases Flexibility for Small Business Accounting. Most large corporations and businesses are required to follow specific accounting rules in preparing their tax returns. Smaller businesses are allowed flexibility to use less cumbersome methods. The 2017 changes to federal tax laws extend this accounting flexibility to most businesses with gross receipts of less than $25 million. Previously there were various lower gross revenue thresholds ranging from $5 million to $10 million.

Considering Income Tax Conformity

In this section we (1) lay out a framework for evaluating potential conformity provisions and (2) provide an assessment of the major conformity provisions based on our framework.

Framework for Evaluating Conformity

Figure 3 summarizes our framework for considering the merits of conforming to federal tax changes.

Figure 3

Conformity Assessment Framework

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other Things Being Equal, Closer Conformity Is Better . . . There are three primary arguments for conforming the state’s income tax laws to some of the recent federal changes: greater simplicity, improved tax administration, and a broader tax base. First, in general, closer conformity between state and federal tax laws eases tax preparation, reduces filing errors, and reduces tax compliance costs. Second, as mentioned above, closer conformity enhances FTB’s tax compliance activities by allowing states to benefit from federal judicial rulings and tax filer audits. Lastly, a broader tax base also usually results in a more horizontally equitable tax structure, with fewer groups receiving preferential treatment.

. . . But Tax Laws Should Have a Clear Rationale. While greater simplicity, improved tax administration, and a broader tax base are good reasons for conforming to federal tax changes, California has selectively conformed to federal tax laws in the past. The Legislature historically has chosen not to follow federal rules in areas where there was not a clear reason for the rule or when the state had different policy objectives from the federal government. Each of the major provisions enacted in 2017 have significant policy considerations that the Legislature will want to weigh against the benefit of greater simplicity. For example, the state may choose not to conform to the new federal limit on interest deductions if there is not a sound justification for doing so. (We discuss the policy considerations of some of the major provisions in the next section.)

Fiscal Effects Uncertain and Likely Will Change Over Time. The estimated fiscal effects of conforming to each of the major federal changes are highly uncertain for three reasons. First, available tax filer data are in some cases limited. Moreover, some estimates were based on adjustments to national estimates rather than California specific information. Second, some tax law changes will affect filers’ choices, which in turn will affect tax revenue. Third, the estimates do not account for the ways in which different provisions may interact based on the Legislature’s conformity choices. For example, if the state limits noncorporate business losses but does not modify NOLs, the change in revenue could be smaller than estimated.

Consider Whether To Make Changes Permanently or Temporarily. Many of the federal changes, especially those affecting individuals, expire on January 1, 2026. Other provisions are permanent. In general, conforming based on to the federal timeline is reasonable. The Legislature may want to consider other options in certain circumstances, however.

- Consider Rolling Conformity When Close Ongoing Conformity Important. If the Legislature believes that close, ongoing conformity is important, consider conforming to those provisions on a rolling conformity basis. For example, the state conforms to provisions affecting retirement accounts on a rolling basis because a lack of conformity may have serious consequences.

- Consider Making Some Changes Permanently. If the Legislature believes that adopting a provision has merit, regardless of federal law, consider adopting the change permanently, regardless of whether it expires under federal law. State law has historically adopted a policy of selective conformity to federal law, with differences reflecting different policy priorities.

- Consider Sunset Dates in Some Cases. If adopting a new income exclusion, deduction, or credit, the Legislature may consider imposing a sunset date—regardless of federal law—so that the continued need for the provision may later be reviewed. (While this consideration does not apply to the major provisions described above, this approach could be applied to Opportunity Zones should the Legislature pursue that proposal.)

Spot Conformity or Change Specified Date of Conformity? There are two general approaches to conformity: (1) adopt a limited number of specific provisions in a “spot” conformity bill or (2) update the specified date of conformity. There are trade‑offs to each of these approaches. Generally, spot conformity would result in fewer changes to state tax law whereas changing the specified date of conformity would affect many provisions of the tax code.

LAO Assessment

In assessing whether to conform to any of the major conformity provisions, the Legislature will want to weigh the general benefits of closer conformity—more simplicity and improved tax administration—with other state policy considerations specific to each provision. Figure 4 summarizes the major conformity provisions, our assessment, and the estimated revenue effect. We provide our assessment on some of the key policy issues regarding the major conformity provisions below.

Figure 4

Assessment of Major Federal Tax Conformity Provisions

|

Conformity Provision |

Effects of Change |

LAO Assessment |

Estimated Revenue Effect |

|

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|||

|

Provisions Affecting Individuals |

||||

|

Limits Noncorporate Business Losses |

Business owners with a loss over $250,000 would be unable to deduct the entire amount in the current year. For fewer than 100,000 filers, conforming would increase tax payments in the current year and reduce payments in future years. |

+ |

$1,200 |

$850 |

|

Suspends Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions |

Filers would be unable to deduct certain previously allowed work‑related expenses. Conforming might increase the amount of taxes paid by about 12 percent of state filers. |

+/‑ |

1,700 |

1,100 |

|

Limits Mortgage Interest Deduction |

Reduces amount of residential mortgage interest that filers could deduct from their income. The change does not affect those with existing mortgages, only those with new mortgages above $750,000. The change affects many with home equity loans. |

+ |

550 |

410 |

|

Limits Deduction for Local Taxes |

Conforming would cap at $10,000 the amount of local property taxes a state filer could deduct. The average amount of property taxes reported in 2016 by state itemizers earning less than $200,000 was just under $5,000. |

+ |

550 |

370 |

|

Suspends Limit on Itemized Deductions |

Conforming would remove the overall limit on the amount of itemized deductions that high‑income filers may claim, making the personal income tax less progressive. |

‑ |

‑2,100 |

‑1,400 |

|

Provisions Primarily Affecting Businesses |

||||

|

Limits Business Interest Deduction |

Limits business interest deduction to 30 percent of “adjusted taxable income.” Conforming would increase business borrowing costs. |

‑ |

800 |

700 |

|

Modifies Net Operating Losses (NOLs) |

Eliminates NOL carrybacks. Limits NOLs to 80 percent of taxable income. NOLs may be carried forward indefinitely. Conforming may increase state fiscal certainty. |

+ |

200 |

210 |

|

Changes Like‑Kind Exchange Rules |

Eliminates like-kind exchanges of personal property. Conforming would mean that filers could no longer defer capital gains on personal property. |

+/‑ |

260 |

200 |

|

Limits Deductions for Fringe Benefits |

Changes rules regarding business deductions for entertainment, food, and transportation expenses. Conforming would somewhat increase business taxes. |

+ |

200 |

160 |

|

Increases Flexibility for Small Business Accounting |

Increases to $25 million the annual revenue threshold for certain tax accounting rules. Conforming would eliminate differences between state and federal law that increase tax compliance costs for some small businesses. |

+ |

‑220 |

‑100 |

|

Legend +The arguments in favor of conforming are somewhat stronger than those against.+/‑There are good arguments both in favor and against conforming. ‑The arguments against conforming are somewhat stronger than those in favor. |

||||

Some Reasons to Consider Limiting Business Losses. Limiting the ability of some filers to use business losses to reduce their taxable income from nonbusiness sources could discourage investment in new or expanded businesses. New businesses often experience losses in the first few years. Allowing taxpayers to use business losses to offset other income lessens the impact of losses on business owners. In contrast, when losses cannot be used to offset nonbusiness income, the impact falls more heavily on the business owner. Despite this possibility, conforming to the federal limits on noncorporate business losses in excess of $250,000 could make sense for several reasons. First, any losses in excess of the limit are converted to NOLs and will reduce future tax payments. Second, some taxpayers create businesses not to engage in profitable activity but to generate losses aimed at reducing the filer’s tax bill. Limiting business losses would discourage this kind of activity. Finally, requiring noncorporate business losses beyond the limit to be converted to NOLs would better align the tax treatment of corporate and noncorporate taxpayers. Better aligning the treatment of noncorporate and corporate taxpayers could reduce the complexity business owners face in deciding the legal structure of their businesses.

Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions: Reasons to Keep Them . . . The deduction for unreimbursed work‑related expenses and certain other expenses related to earning income can make income taxes more equitable. For example, consider two similar workers: (1) one who makes $90,000 per year, whose employer reimburses all of her work‑related expenses; and (2) one who makes $95,000 per year while incurring $5,000 of unreimbursed work‑related expenses. The workers’ net pay is the same, so an equitable tax system would require them to pay the same amount of tax. Without miscellaneous deductions, however, the second worker pays more tax than the first.

. . . And Reasons to Suspend Them. There are two reasons to consider conforming state law to also disallow these deductions. First, the existing threshold for qualifying for the deductions—2 percent of AGI—limits their effectiveness at addressing differences among similar filers because workers must incur significant expenses before qualifying for the deductions. Second, conforming would make tax compliance and administration simpler.

Mortgage Interest Deduction Conformity Worth Considering. The federal mortgage interest deduction changes primarily affect higher‑income homeowners who likely would have been able to afford their home even without the deduction. For these tax filers, the deduction is largely a windfall. In addition, conforming to this change could temporarily slow price growth for homes priced above $900,000 providing some relief to home buyers in expensive coastal markets. For home equity loans, conforming would make the cost of borrowing more expensive for people who use these loans as lines of credit (rather than for home improvements).

Conformity to SALT Deduction Would Affect Few Filers. Capping deductions for local tax payments—primarily the property tax—would affect a small minority of state filers and would make the state PIT somewhat more progressive. In 2016, the average deduction was just under $5,000 for filers who itemized their deductions and made less than $200,000, and roughly $8,000 for itemizers with income between $200,000 and $300,000. The small number of filers deducting more than $10,000 likely recently purchased expensive homes or own multiple homes. The Legislature, therefore, could conform to this provision without increasing most filers’ tax liability. Those living in the state’s more expensive, coastal real estate markets could be most affected.

Suspending the Limit on Total Itemized Deductions Would Make PIT Less Progressive. For a subset of deductions, California limits the total amount of itemized deductions that may be claimed by filers with incomes above $187,203 for single filers and $374,411 for married filing jointly. These limits increase as filers’ incomes increase. For those with very high incomes, total deductions may be reduced by up to 80 percent. Consequently, these limits significantly reduce the value of deductions, increase filers’ taxable income, and make the PIT more progressive. (As noted earlier, however, the limit does not apply to some large deductions, such as those for medical expenses and certain losses.) Conforming to the federal suspension of these limits would reduce state taxes paid by high‑income filers, making the state PIT less progressive.

Limiting the Business Interest Deduction Could Affect State’s Business Climate. Business income taxes are intended to tax net income after accounting for ordinary and necessary business expenses. Consequently, businesses may deduct their interest payments. For instance, if a manufacturer borrows money to purchase equipment, their interest payments are deductible. By limiting the amount of interest businesses can deduct, the 2017 change in federal tax law increases the cost of borrowing for some firms. Conforming to this change could harm the state’s business climate.

Modifying NOLs Could Offer Increased Fiscal Certainty. Conforming to federal changes related to NOL deductions could allow the state to recognize some benefits while continuing to smooth corporations’ gains and losses. Although conforming to the federal changes would restrict businesses’ ability to smooth income and tax payments to some extent, businesses would retain significant ability to do so. At the same time, conformity—specifically limiting carrybacks—likely would offer increased fiscal certainty for the state, especially during a recession. Usage of NOL carrybacks tends to increase during economic slowdowns as more businesses experience losses. Increased usage of carrybacks reduces businesses’ tax payments, exacerbating general weakness in revenue collections during a slowdown. Eliminating carrybacks would prevent this problem. (Only a minority of states permitted NOL carrybacks even before the recent federal changes. The Governor’s proposal applies only to the changes to carrybacks.)

Restrictions on Like‑Kind Exchanges Raise Competing Considerations. The Legislature is faced with competing arguments in considering whether to conform to federal restrictions on like‑kind exchanges. In general, there is a reasonable argument to defer capital gains taxes in a like‑kind exchange. If a taxpayer uses all of the cash from the sale of property to purchase new property, he or she may not have cash on hand to pay taxes on their capital gains. Like‑kind exchange rules allow taxpayers to defer their capital gains taxes until they make a property transaction that increases their cash on hand. At the same time, allowing like‑kind exchange deferrals presents problems. In particular, property owners may choose a particular transaction to receive a tax benefit when a different transaction would have otherwise been more beneficial. For example, a business owner may sell an old delivery truck and replace it with a new truck to take advantage of like‑kind exchange rules but may have preferred instead to use the cash to purchase a new computer system to optimize deliveries. (We expect there will be fewer like‑kind exchanges of personal property than in the past because of the change in federal law. State conformity likely will have a smaller effect on behavior and state revenue may increase somewhat regardless of whether the state conforms.)

Deductions for Fringe Benefits Can Lack Policy Rationale in Some Cases. Federal changes related to fringe benefits primarily affected transportation, entertainment, and meals. Those changes reduced or eliminated employers’ ability to deduct those benefits provided to employees. Typically, business expenses—including these fringe benefits—are deductible because these costs enable businesses to earn income. In some cases, however, transportation, entertainment, and meals may not be necessary to conduct business and instead provide a tax‑advantaged benefit to employees (because the employees do not have to pay income taxes on these employer‑provided benefits). Because distinguishing between necessary transportation, entertainment, and meal benefits and those that otherwise increase employees’ overall compensation is difficult, conforming to this federal change may be warranted.

Allowing Greater Accounting Rule Flexibility Reasonable. Allowing greater accounting flexibility would simplify tax filing for roughly 60,000 businesses in California. Given the complexity associated with business accounting, conforming to this change would reduce significant differences in tax filing for some medium‑sized businesses. This additional flexibility, however, could result in some businesses reducing their tax liability and lower tax payments somewhat.

Conclusion

Whether to conform to federal tax changes merits Legislative deliberation regardless of the revenue effects. While the Governor’s proposal appears to link conformity and EITC in order to create a revenue neutral proposal, there are simpler means of raising additional revenue if the Legislature wishes to expand the EITC. That said, if the state conforms to the major provisions discussed above, state revenues could increase by several billion dollars. The Legislature could take a variety of steps—including reducing rates or increasing the personal exemption—to mitigate the effects of conformity

Appendix: Other Potential Conformity Provisions

These are other provisions that could be included in a conformity package. Broadly, conforming to these provisions would simplify the state tax code. To our knowledge, most of these do not affect many filers and/or have minor fiscal effects. Moreover, generally these changes would not be inconsistent with existing state tax law. (Those provisions included in the Governor’s updated conformity proposal are noted in the right‑most column.)

Other Potential Conformity Provisions

|

Provision |

Effects of Conforming |

Part of Governor’s Proposala,b |

|

Changes “Kiddie Tax” Rules |

Simplifies rules regarding the taxation of the dividends, interest, and capital gains earnings of dependent children that are subject to filing requirements. |

|

|

Raises Limit on Charitable Contributions |

Increases the amount of certain charitable contributions an individual may deduct from 50 percent to 60 percent of their income. |

|

|

Allows Increased Contributions to Achieving Better Life Experiences (ABLE) Accounts |

Changes some rules regarding contributions to an ABLE account. The maximum total contribution of $14,000 per year remains unchanged. |

|

|

Allows Rollovers to ABLE Accounts |

Allows an individual with a disability to convert a “Section 529” educational savings account to an ABLE account without penalty. |

|

|

Treatment of Certain Individuals Performing Service in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt |

Grants special tax benefits to military service members serving in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. There are currently similar provisions in state law. |

|

|

Treatment of Student Loans Discharged on Account of Death or Disability |

Excludes the discharge of student loan debt in case of death or disability from income. |

|

|

Suspends Exclusion for Moving Expense Reimbursement |

Includes employer reimbursements of moving expenses as income. |

|

|

Suspends Moving Expenses Deduction |

Eliminates the deduction for moving expenses. |

|

|

Limits Wagering Losses |

Clarifies the definition of “losses from wagering transactions.” |

|

|

Repeals Deduction for Alimony Payments |

Repeals the deduction for alimony payments for any divorce or separation executed after December 31, 2018. It is our understanding that this change was made to follow the rule of the United States Supreme Court’s (the Court’s) holding in Gould v. Gould, in which the Court held that such payments are not income to the recipient. |

|

|

Modifies Certain Depreciation Rules |

Adopts technical changes to certain depreciation rules (as applicable). |

|

|

Modifies Special Rules for Taxable Year of Inclusion |

Modifies special rules regarding when businesses must recognize certain income for tax purposes. |

|

|

Denies Deductions of Certain Fines, Penalties, and Other Amounts |

Changes business deduction rules to disallow deductions for penalties imposed for violating certain laws. |

|

|

Denies Deductions for Sexual Harassment or Abuse Settlements |

Changes business deduction rules to disallow deductions for payouts and attorney fees related to sexual harassment or sexual abuse if the payments are subject to a nondisclosure agreement. |

|

|

Repeals Deduction for Local Lobbying Expenses |

Modifies rules for lobbying expenses deductions. |

|

|

Changes Rules Regarding Deductions for Certain Employee Achievement Awards |

Modifies rules about deductions of specific types of employee achievement awards. |

|

|

Modifies Partnership Taxation Rulesc |

Modifies several rules regarding how partnership income is taxed. |

|

|

Modifies Rules Related to Life Insurance |

Modifies several rules regarding the value of life insurance contracts when they are sold or transferred. |

|

|

Limits Deductions of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Premiums |

Limits the deduction of deposit insurance premiums paid by banks. |

|

|

Changes Electing Small Business Trust (ESBT) Rules |

Changes several rules regarding ESBTs. |

|

|

Changes Accounting Treatment of S Corporation Conversions |

Changes several rules regarding a corporation that was previously a subchapter S corporation. |

|

|

Expands Limits on Excess Employee Compensation |

Eliminates the performance‑based compensation exception from limits on excessive employee compensation and expands the number of employees affected. |

|

|

Modifies Treatment of Qualified Equity Grants |

Modifies several rules related to qualified stock equity grants. |

|

|

Modifies Tax‑Exempt Organization Rules |

Modifies rules regarding treatment of unrelated business taxable income of tax‑exempt organizations. |

|

|

aAs of March 1, 2019. bThe administration also proposed to conform state law to a provision of federal law—Section 338—regarding the tax treatment of certain corporate stock transactions. This difference pre‑dates the 2017 federal law. cThe administration proposes only to conform to the repeal of “technical termination” of partnerships—tax rules that apply when there is a significant change in ownership of a partnership. |

||