March 6, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of Proposed Earned Income Tax Credit Expansion

- Introduction

- Background

- Governor’s Proposal

- Assessment

- Alternative Credit Designs

- Options for Providing Monthly Credits

- Conclusion

Summary

Governor Proposes $600 Million Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Expansion. The state adopted an EITC in 2015 and expanded it in 2017 and 2018. The Governor proposes another expansion starting in 2019. This proposal would cost roughly $600 million and would: (1) extend the income eligibility range to $30,000, (2) increase the credit amount for workers with dependents under age six, and (3) increase the credit amount for workers with earnings at the higher end of the current eligibility range. The administration also proposes exploring options for providing monthly credits.

Proposal Would Modestly Affect Poverty and Work Incentives. One way to evaluate an EITC expansion is the extent to which it alleviates poverty among workers. Although the Governor’s proposal would provide benefits to a large number of Californians in poverty, it only would move roughly 50,000 workers above the poverty line and 12,000 workers above deep poverty (half of the federal poverty level). Another way to evaluate the proposal is its effects on work incentives—both for workers to enter the workforce and to work full time. The Governor’s proposal to increase the credit for families with dependents under six would strengthen the incentive for those parents to enter the workforce. Most of the proposed expansion, however, is focused on encouraging more workers to work full time. That said, evidence at the federal level suggests that the EITC does not have much of an effect on workers’ decision to work more hours if they are already working. Consequently, the increased benefit under the Governor’s proposal would be unlikely to have a large effect on work patterns.

Alternative Credit Designs. We offer two alternative credit designs for Legislative consideration (both would cost roughly $600 million). The first increases the benefit most for those with the lowest earnings, providing more assistance to those in deep poverty (moving 58,000 workers above deep poverty). This credit design also would increase the incentive for people to enter the workforce relative to the Governor’s proposal. The second alternative increases the maximum eligible income and increases the benefit for those toward the higher end of the eligibility rage. Relative to the Governor’s proposal, this credit design further reduces the disincentive for moving from half‑time work to full‑time work (although these effects might still be relatively small). The Legislature’s ultimate design of a credit expansion will depend on how it wishes to prioritize reducing poverty, increasing workforce participation, or encouraging full‑time work.

Options for Monthly Payments. Assuming providing monthly credits would not affect Californians’ eligibility for federal health and human services programs; the state could take a variety of approaches for providing monthly benefits. The main considerations we discuss in this report are (1) which agency should administer the program and (2) whether payments should be made in advance or on a deferred basis. While advanced payments likely would be more helpful to the recipients, accurately estimating worker’s EITC advance would be difficult, but also important. In particular, attempts by the state to recoup over‑payments could create hardships for those affected.

Introduction

The state adopted an EITC in 2015 and expanded it in 2017 and 2018. The Governor proposes another expansion starting in 2019 that would (1) extend the income eligibility range to $30,000, (2) increase the credit amount for workers with dependents under age six, and (3) increase the credit amount for workers with earnings at the higher end of the current eligibility range. This report evaluates the Governor’s proposal, discusses potential alternative approaches, and examines implementation issues and options for providing credits on a monthly basis.

Background

Federal EITC

Refundable Credit Based on Earned Income. The federal EITC is a provision of the U.S. income tax code that allows workers filing a tax return who earn less than a certain amount (about $46,000 for single workers with two dependents) to reduce their federal tax liability. The EITC is refundable. The amount of the credit depends on the worker’s “earned income” (which primarily includes wages and self‑employment income), filing status, and number of qualifying dependent children. The amount of the federal credit initially rises with earnings, such that the greater the worker’s earnings, the larger the credit. The federal EITC peaks and is then flat for a range of income—between $14,250 and $18,700, for example, in the case of single workers in 2018 with two dependents. The credit then gradually phases out for workers with higher levels of income (generally those working full time). The credit is “refundable,” meaning that the worker receives the full amount of the credit even if it reduces their liability below zero.

Federal EITC Benefit Can Be Significant. The average credit nationally in 2016 was $3,181 for workers with dependent children. Workers with fewer qualifying dependents receive lesser amounts. The benefit for workers with no qualifying dependent children is much smaller (the maximum credit for such individuals is $519).

Federal EITC Reduces Poverty. The EITC increases the after‑tax income of low‑income individuals and families. In 2016, 3.1 million California workers (representing nearly 10 million people) earned a total of $7.2 billion of federal credits with an average credit amount of $2,314. These EITC amounts moved an estimated 750,000 Californians’ income above the federal poverty level ($20,160 annually for a family of three in 2016, lower for smaller households, and higher for larger ones).

Federal EITC Generally Encourages People to Enter Workforce. The amount of the federal credit initially rises with earnings, increasing the value of work. Consequently, when individuals receiving the EITC first enter the workforce, their total after‑tax earnings are greater than their initial pre‑tax wages. This creates a stronger incentive for people to join the workforce. Studies have shown that the federal EITC has resulted in significantly more people entering the workforce, particularly low‑wage and low‑skilled single parents. (See our December 2014 report, Options for a State Earned Income Tax Credit, for more information about the design and effectiveness of the federal EITC.)

Federal EITC Can Discourage People Already Employed From Working More Hours. The design of the federal EITC provides the largest benefits to low‑wage workers who work part‑time. While this design increases the number of participants in the formal labor market, the structure can discourage workers from pursuing full‑time work. This is because the phase out of the credit may offset the additional earnings associated with working more hours. For example, a single person with two dependents who works 20 hours per week at $15 per hour earns $15,000 over a full year (working 50 weeks). In 2018, this worker would receive the maximum federal EITC benefit of $5,716. If the same worker instead worked full time, his or her pre‑tax earnings would rise to $30,000 and his or her EITC benefit would be $3,333. Given the roughly $2,400 decline in the worker’s EITC benefit, the worker’s net earnings increase from working full time would be roughly $12,600 (rather than $15,000). This benefit decline can discourage people from moving to full‑time work, although evidence suggests that in practice this impact is small. (For those already working full time, the phase out of the EITC does not appear to affect decisions about how many hours to work.)

California’s EITC

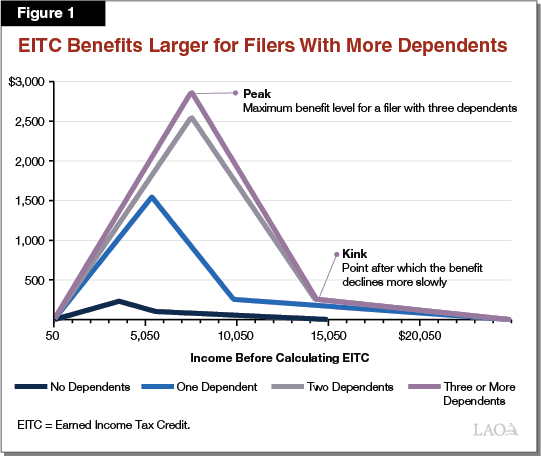

State EITC Builds on Federal Credit. Most of the state EITC’s provisions are modeled on federal provisions, such as that eligible filers must be U.S. citizens or permanent residents. Like the federal EITC, the state credit is refundable and the credit amounts are larger for filers with more dependents, as explained below. The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) annually adjusts the income thresholds and credit amounts for inflation, similar to the adjustment made at the federal level (although the state uses a California‑specific inflation index). As with the federal credit, the state EITC provides larger amounts for workers with more dependents (up to three). For example, at $10,000 of income the EITC benefit is $62 for a worker with no dependents, $254 for one dependent, $1,740 for two dependents, and $1,958 for three or more.

State EITC Structure Differs From Federal. As with the federal EITC, the state credit amount initially rises as workers’ earnings rise and phases out above a certain income level. The state credit, however, lacks a broad range of income over which the credit is constant. Instead, the credit amount peaks at a narrow range of incomes and declines for any amount of income past the peak. For example, in 2018 the maximum credit for a worker with two dependents is $2,559, corresponding to income in the narrow range of $7,501 to $7,550. The state credit also has a point (the “kink”) after which the benefit phases out much more slowly. Figure 1 shows how the income levels of these peaks and kinks vary in 2018 depending on the number of the workers’ dependents. Workers whose income is to the right of (higher than) the kink points generally receive much lower benefit levels than those with income to the left of (below) the kinks.

Nearly 1.5 Million Filers Claimed State EITC in 2017 . . . In tax year 2017, roughly 1.5 million California filers received a total of $348 million in credits under the state EITC. Figure 2 shows the number of dependents for these workers and their average and median credit amounts. As seen in the figure, nearly half of these workers did not have dependents and received much smaller EITC benefits. Moreover, for each category of filer, the median credit amounts are much lower than the average credit amounts. That is because most workers claiming the EITC receive fairly small amounts, but a small portion of recipients (typically those with income between $5,000 and $10,000) see much larger benefits.

Figure 2

Average EITC Benefits Exceed Median Benefits

2017 Tax Year

|

Dependents |

Number of |

EITC Benefit: |

|

|

Average |

Median |

||

|

0 |

674,111 |

$76 |

$62 |

|

1 |

429,942 |

267 |

163 |

|

2 |

253,177 |

474 |

193 |

|

3+ |

119,830 |

515 |

192 |

|

EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit. |

|||

. . . Recent Changes to EITC Likely to Increase Use Further. The Legislature expanded the state EITC for tax year 2018 in two ways. First, the income limits were raised from $22,300 to $24,950 for filers with dependents and from $15,000 to $16,750 for workers with no dependents. This increased the number of workers eligible for the state credit. At the time, the Department of Finance (DOF) estimated this change would affect roughly 700,000 additional potential workers. Second, workers with no dependents who are under age 25 or over age 65 were made eligible. No filing data is available yet on how this change has affected the number of filers claiming the credit or the credit’s total cost. Under the administration’s current estimates, however, the state EITC (including this expansion) is expected to cost $410 million in 2018‑19.

State Provides Funding for Outreach. Many community‑based organizations and other state and local government agencies (such as school districts and county social services offices) engage in efforts to raise awareness about the state and federal EITC. In 2016 and 2017, the state awarded $2 million in grants to these groups to help expand these education and outreach efforts. These efforts include advertising and media outreach, distribution of printed materials, and canvassing—direct contact with individuals in targeted residential neighborhoods. In 2018, the state increased the amount of grants it awarded to $10 million and allowed grant recipients to fund tax filing assistance. In addition, FTB receives $900,000 annually for additional EITC outreach activities and to fund the grant making process. State EITC grants are currently administered through an interagency agreement with the Department of Community Services and Development (CSD).

Governor’s Proposal

Proposal Would Expand EITC in Three Ways. The administration proposes expanding the state EITC in three ways: (1) providing an additional $500 credit for all EITC‑eligible workers that have at least one child under the age of six, (2) increasing the maximum qualifying income to $30,000, and (3) increasing the credit for individuals and families with earnings at the higher end of the eligibility range. The administration estimates these changes would increase the amount of credits received by $600 million—bringing the total cost of all EITC credits to around $1 billion—and increase the number of taxpayers receiving the credit by 400,000. The administration also proposes renaming the credit to the “Cost of Living Refund” (previously, the Governor’s budget proposed renaming the credit the “Working Families Tax Credit”). We describe each of the three major aspects of the Governor’s proposal in more detail below.

Additional Credits for Families With a Child Under Age Six. First, the Governor’s proposal would increase the EITC for every eligible worker with at least one dependent child under the age of six. This increase would be a flat $500 for every worker with income under $28,000, then phase out between $28,000 and $30,000 of income at a rate of $1 of credit for each $4 of income. (This phase out range would be fixed until 2022 and would be adjusted for inflation thereafter.) DOF estimates that this change would affect 400,000 workers and cost $240 million annually if implemented alone.

Maximum Eligible Earned Income Amount Would Increase. Second, the Governor proposes increasing the maximum eligible income to $30,000 for all workers regardless of their number of dependents. The current maximum income for eligibility is $24,950 for workers with dependents and $16,750 for workers with no dependents. DOF estimates that this will make the credit available to up to 1 million new workers and would cost $70 million in 2019‑20 if implemented alone. Of these new workers, about 70 percent would have no dependents. The administration also proposes holding the income limit at $30,000 until 2022, after which it would be automatically adjusted annually for inflation.

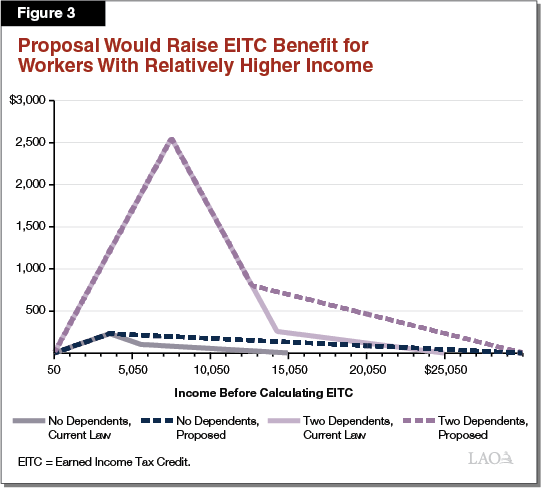

Credit Would Phase Out More Slowly. Finally, the Governor proposes increasing the credit for individuals and families with earnings at the higher end of the eligibility range. Under current law, a worker’s EITC benefit starts to decline once it exceeds the peak level. Initially, the benefit declines rapidly, as shown by the steep line after the peak and before the kink in Figure 3. Within this income range (to the left of the kink) EITC benefits decrease at the same rates they increase before the peak (for example, 34 cents for each additional $1 earned for a worker with two dependents). After the kink, the benefit declines more slowly, decreasing the benefit by less than 2 cents for each additional $1 earned for workers with any number of dependents. Figure 3 shows the differing benefit amounts (Governor’s proposal compared to current law) for workers with no dependents and those with two dependents. As seen in the figure, the Governor’s proposal would eliminate the kink for workers with no dependents entirely. For workers with dependents, the Governor’s plan would move the kink point further to the left. DOF estimates this change would cost $300 million annually if implemented alone.

DOF Estimates Entire Proposal Would Cost $600 Million. DOF estimates the cost of all three components of the proposal to be about $600 million. This is more than the sum of the estimates for the components because some components interact with one another. For example, the additional $500 for workers with dependents under age six would cost more if the maximum income were increased to $30,000 than if it remained at $25,000. The Governor proposes paying for this proposal with some conforming changes to state tax law to reflect major changes to federal tax law passed in 2017. The administration’s intent is to raise enough revenue through these changes to cover the entire cost of the EITC (roughly $1 billion annually), not just the proposed expansion.

Governor Proposes Providing $5 Million for Outreach. The Governor’s proposal includes $5 million for EITC outreach and education grants to community‑based organizations and other state and local government agencies. In a departure from recent state practice, in which outreach funding was provided to FTB and administered by CSD, these grants would be administered through the Office of Planning and Research (OPR). The proposal also indicates that the state will require grantees to provide a funding match as part of their applications. The administration has not provided any details on how OPR would administer these grants or the criteria for distributing them.

Governor Proposes Examining Options to Provide Monthly Credit. As it is currently structured, workers eligible for the EITC receive a tax refund after they file their annual taxes. This generally occurs several months following the end of the year. The administration has committed to exploring ways to provide the EITC, or a portion of the EITC, to qualified workers during the year in monthly payments rather than later in a lump sum. The administration does not have a specific monthly payment proposal for us to evaluate, but we discuss possible options for legislative consideration later in this report.

Assessment

This section first assesses the Governor’s proposal to link the EITC expansion with state tax law changes. We then lay out criteria the Legislature can use to evaluate an EITC proposal or expansion and then evaluate the Governor’s proposal using these criteria. We conclude this section with a summary of our assessment of the Governor’s proposal.

Conformity Changes and EITC Expansion Should Be Considered Separately. While the Governor proposes them together, we suggest the Legislature consider the merits of the EITC expansion separately from the proposed conformity changes to state tax law. Attempting to offset revenue losses from an expanded EITC with conformity actions is problematic. Estimates of the revenue impacts of expanding the state EITC and possible conformity actions are subject to considerable uncertainty. Considering these proposals separately would mean the state would need to use ongoing General Fund resources for an EITC expansion. Both our November Outlook and the administration’s January estimates (without the Governor’s proposed conformity changes) suggest that an additional roughly $3 billion in ongoing General Fund resources might be available for additional budget commitments in 2019‑20. Excluding the EITC, the Governor proposes $2.7 billion in new ongoing spending in 2019‑20, growing to $3.5 billion over time. We suggest the Legislature consider an EITC expansion relative to the ongoing spending proposals introduced by the Governor. Given the effectiveness of the EITC at reducing poverty and increasing labor market participation, we think an expansion merits serious consideration.

Criteria to Evaluate EITC Proposals. There are three basic criteria that can be used to evaluate proposals to modify the EITC. First, how does the proposal affect poverty in the state? Does the proposal target those in deep poverty (those with income less than half of the poverty level)? Second, how does it affect work incentives, both for people who have to decide whether to enter the formal labor market and for people who are already working but are considering switching from part time to full time or vice versa? Third, what does the proposal cost, in terms of both revenue and additional compliance and administration?

Poverty Impact

One major policy goal of the EITC is to reduce poverty. In this section, we evaluate the extent to which the Governor’s proposal would help reduce poverty in California and among which groups. We estimate that roughly 1.2 million workers receiving the EITC in 2017 were below the poverty line and 420,000 were in deep poverty. (Roughly 5.2 million Californians overall are in poverty and 2.5 million are in deep poverty. These numbers are larger because they represent all Californians—including children—not just those filing taxes.) Here, we refer to the official poverty measure as opposed to the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) which accounts for differences in living costs and for the effects of other means‑tested programs such as California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKS) and CalFresh. While the SPM is usually a more relevant measure, tax filing data does not provide sufficient information for us to evaluate the effects of the proposal using SPM. Under the SPM, the poverty and deep poverty thresholds are significantly higher than they are under the official measure (likely above $30,000 for many larger households). Measured against the SPM, the Governor’s proposal would benefit more workers with income below that threshold, but move fewer of them out of poverty.

Proposal’s Impact Would Be Broad, but Not Deep. Like the 2017 expansion, the Governor’s proposal would provide a broad but modest benefit increase. We estimate that it would benefit roughly 1 million workers (slightly less than half of whom would have no dependents) who have incomes below the federal poverty line. Despite the fact that the proposal would provide benefits to a large number of Californians in poverty, it would only move roughly 50,000 workers above the poverty level (excluding federal EITC benefits and other federal and state supports) and roughly 12,000 above the deep poverty level. In large part, this is because the Governor’s proposal does not raise the maximum benefit amount. (These figures do not account for any change in EITC participation or in current workers’ number of hours worked. The proposal’s impact on poverty likely would be greater to the extent that it encourages more people to enter the workforce.) The proposal also would modestly increase EITC benefits for an estimated 1.2 million workers (about 60 percent of whom would have no dependents) who have relatively low income but are nonetheless above the poverty line.

Largest Benefits Would Be to Two Groups of Workers. While the Governor’s proposal generally provides a relatively small benefit increase to many workers, two groups of workers would see the largest benefits:

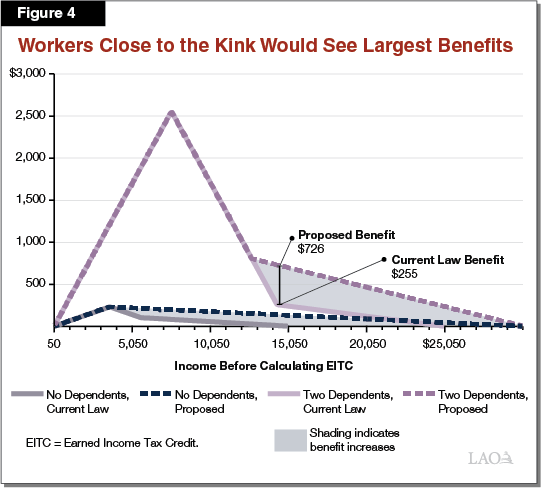

- Workers With Income Just Beyond Kink Points Would See Largest Benefit Increases. Figure 4 shows the increase in benefit under the Governor’s proposal compared to current law for workers with no dependents and workers with two dependents (similar to Figure 3). The shaded portions of the figure show the increase in benefit to workers at each income level relative to current law. As seen in the figure, the largest increase in benefit goes to those who under current law are at or close to the kink. Workers “at or close to the kink” are those who earn around $5,000 annually if they have no dependents, $10,000 with one dependent (not shown), or $15,000 annually with two or more dependents.

- Up to 400,000 Workers With Dependents Under Age Six Could Benefit. We estimate that about 385,000 workers with $30,000 or less of income in 2017 had at least one dependent under the age of six. Under the Governor’s proposal, these workers would receive an additional $500 benefit regardless of other changes to the EITC.

Work Incentives

Every EITC program faces an inherent tension. On one hand, by increasing the value of initial earnings, an EITC encourages people to enter the workforce. On the other hand, the EITC reduces the incentive to work for those with income within the “phase out” range (where the credit amount is declining). This can discourage people from moving from part‑time to full‑time work in some cases. In this section, we consider how well the Governor’s proposal encourages people to join the workforce while reducing the disincentive to work full time.

Proposal Would Increase Incentive to Enter Workforce, Mainly for Workers With One Dependent Under the Age of Six. The Governor’s proposal would strengthen the incentive to enter the workforce somewhat, but mostly for certain groups. In particular, the Governor’s proposal to provide a $500 credit to workers with dependents under age six could encourage those not currently working to work at least part of the year. The structure of the Governor’s proposal also would increase the benefit for a worker with one dependent working 20 hours a week at the minimum wage (income of $11,000) from $236 to $691 (or to $1,191 if the dependent is under age six). As such, this proposal creates a somewhat larger incentive for that individual to work part time. (This increased benefit is specific to a worker with one dependent earning roughly $11,000 per year.) The proposal would not create a similar work incentive for individuals with similar earnings and either no dependents or multiple dependents (none of whom are under the age of six).

Proposal Would Slightly Reduce Disincentive for Full‑Time Work. As described earlier, the largest component of the Governor’s proposed expansion benefits those with relatively higher earnings. Increasing the benefit to these workers by changing the phase out of the credit could reduce the disincentive to move to full‑time work. That said, evidence at the federal level suggests that the phase out of the EITC has very limited impact on current workers’ hours, and such a small effective wage increase is unlikely to have a large effect on work patterns.

Minimum Wage Increases Would Affect Future Work Incentives. The state’s minimum wage is scheduled to rise by $1 per hour at the start of each of the next four years, reaching $15 per hour by 2023 for all employees. As such, the effect of an EITC expansion on work incentives will be very different in 2023 from what they are in 2019. This table shows how the benefits for working part time and full time would change for a worker with two dependents (both over age six) who works a full year at the minimum wage from 2019 to 2023. (We assume inflation adjustments would increase EITC income thresholds and benefit amounts by 10 percent by 2023.) As Figure 5 shows, EITC benefits for both types of workers will decline as the minimum wage increases.

Figure 5

Benefits May Decline as Minimum Wage Rises

Full Year Earnings Based on 50 Weeks

|

Minimum |

Full Year Earnings |

EITC Benefit: |

||||

|

20 hr/Week |

40 hr/Week |

20 hr/Week |

40 hr/Week |

|||

|

2019 |

$11 |

$11,000 |

$22,000 |

$1,384 |

$375 |

|

|

2023 |

15 |

15,000 |

30,000 |

766 |

39 |

|

|

aFor employers with 25 or fewer employees. EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit. |

||||||

Costs and Administrative Issues

Estimates Are Always Uncertain. Estimating the costs to create and expand the state EITC was tricky when the program was first established. This largely was due to the fact that many state EITC filers had not previously filed state tax returns (because most of them did not owe state taxes). There is less uncertainty in estimating the cost of the Governor’s proposal for two reasons. First, the state has had some years of experience operating its own EITC. Second, the Governor’s proposal targets somewhat higher income groups, most of whom already file state taxes. That said, there is always some uncertainty in projecting costs associated with a new program and the actual costs associated with an expanded EITC could be higher or lower than the Governor suggests.

Administration’s Cost Estimates Appear Reasonable. We estimate that the Governor’s proposal would cost about $550 million if there is no increased participation for currently eligible households. The proposed benefit increases—particularly for those with dependents under age six—likely will increase participation among those already eligible, however. DOF’s estimate of $600 million is therefore reasonable assuming some additional participation by those eligible under current law.

FTB May Be Able to Validate Dependents’ Ages in Coming Years. FTB does not have a way to validate dependents’ ages. Currently, FTB relies on voluntary taxpayer compliance, subject to audit. For example, if the FTB believes that a worker has claimed an ineligible dependent as a child in error, it may request additional information from the worker—including documentation of the age of any dependents—before processing a refund. The administration’s proposal to provide additional benefits for workers with at least one dependent under age six increases the advantages of having a method to validate the age of a dependent child prior to approving a refundable tax credit. We understand that FTB is looking into ways to exchange worker data—including full names, dates of birth, and social security numbers—with the Social Security Administration (SSA), but that may not be available for a couple of years. Implementing a new age validation system with the SSA will require additional one‑time and ongoing costs.

Outreach Funding Lacks Clear Plan. FTB and CSD are currently working on a report that evaluates the effectiveness of the state’s EITC education and outreach grant program. The administration expects that OPR will work with FTB and CSD to determine the most effective outreach strategies, based in part on the findings of that report. More broadly, however, the administration has not provided a clear rationale for shifting outreach funding from FTB to OPR. In particular, why the administration expects OPR would improve education and outreach is unclear.

Summary of Assessment of Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s proposal provides the largest benefit to those working more than part time. This reduces the disincentive for full‑time work associated with the EITC. Research suggests, however, that the phase out of the EITC has very limited impact on current workers’ hours. Moreover, the Governor’s proposed effective wage increase likely is too small to have a large effect on work patterns.

The Governor’s proposal also aims to reduce poverty and somewhat increase the incentive to join the labor market, especially among those who have children under the age of six. While roughly 400,000 workers with young children could benefit significantly, we estimate the proposal would raise only about 50,000 workers above the federal poverty line and roughly 12,000 above the deep poverty level.

Alternative Credit Designs

In this section, we provide a few different alternative credit design options for legislative consideration. Each of the EITC alternatives outlined would carry the same costs as the Governor’s proposal. The first set of options focuses more on the goals of addressing poverty and increasing work incentives. The second option focuses more on reducing the disincentive for full‑time work.

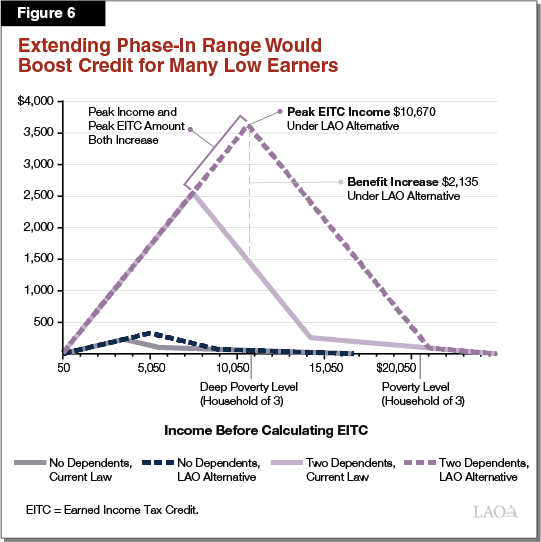

Alternatives to Mitigate Poverty and Promote Workforce Participation

Target Benefits to Those in Deep Poverty and Encourage More People to Enter Workforce. Rather than focusing on encouraging those already in the labor force to work more hours, the Legislature may wish to expand the EITC to create a stronger incentive for people to enter the workforce and provide larger benefits to those in deep poverty. The Legislature could do this by extending the credit’s phase‑in range at the current credit percentages. This would both (1) increase the maximum benefit and (2) increase the income at which workers qualify for the maximum benefit. For example, assuming the Legislature wanted to expand the EITC by $600 million—as in the Governor’s proposal—it could increase both the peak EITC benefit and the income at which the maximum benefit is reached by 42 percent. Almost the entire benefit of this proposal would go to workers currently below the poverty line and provide larger benefits to those near deep poverty. In particular, we estimate this alternative would move roughly 1,000 workers’ income above the federal poverty line, but would move 58,000 workers out of deep poverty. As with the Governor’s proposal, these figures would be higher to the extent that the EITC benefit encouraged more labor force participation. Moreover, we expect this effect to be bigger under this alternative, as the benefit increase for most part‑time workers would be much higher.

Figure 6 shows how the maximum benefit and income levels would change under this alternative for workers with zero and two dependents. (All other elements of the EITC—like the phase out—would remain the same as under current law.) For single workers with two dependents, the maximum benefit would be reached at an income of $10,670 which is equal to working about 19 hours per week for a full year at the minimum wage of $11 per hour (the minimum wage for employers with 25 or fewer employees).

Expanded Child Care Tax Credit Could Be an Alternative to Proposed $500 Credit. Rather than providing a $500 credit for workers with at least one dependent under the age of six, the Legislature could consider expanding the existing tax credit for child care expenses. Currently, the state credit is modeled on the federal credit, which reduces workers’ taxes up to a certain amount based on child care costs. Prior to 2010, the state credit was refundable. At the time, the average credit amount for filers making less than $40,000 a year was $368. Today, workers with less than $40,000 of income receive very little benefit because these workers typically do not owe state taxes and the credit is not refundable.

Making the Credit Refundable Could Target Assistance to Lower‑Income Families. We estimate that making the state child credit refundable and increasing the amount of the credit to be more similar to the federal credit would cost approximately $125 million annually. Generally, making this credit refundable would benefit a broader income range—up to $60,000 in income—than under the Governor’s EITC expansion proposal. Extending the credit to relatively higher incomes would benefit households with a second earner and could encourage a second parent to work. (See our April 2016 report, Options for Modifying the State Child Care Tax Credit, for more information about this credit.) If the Legislature wished to make this change in addition to extending the credit’s phase‑in range, it could either somewhat reduce the maximum benefit expansion or increase the costs of an EITC expansion relative to the Governor’s proposal somewhat.

Alternatives for Promoting Full‑Time Work

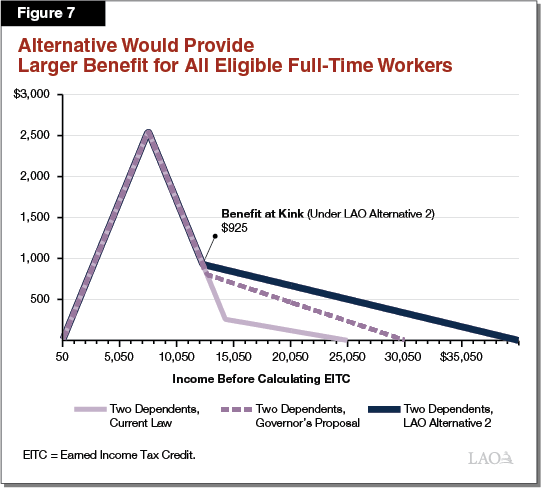

Larger Benefits for Workers With More Earned Income Could Encourage Full‑Time Work. As discussed earlier, EITC benefits can discourage people from moving to full‑time work in some cases. One way to address this obstacle is to (1) increase the maximum eligible income and (2) increase the benefit for those toward the higher end of the eligible income range, so that the increased benefit for full‑time workers phases out more slowly. Figure 7 shows a second alternative for this type of expansion. Under this alternative, the maximum eligible income would be $40,000 for workers with at least one dependent, and the increased benefit (relative to current law) for working full time at minimum wage (income of $22,000) would be $463 for workers with one dependent, $531 for two dependents, and $537 for three or more. (Workers with dependents under six years old would not receive an additional benefit under this example. Workers with no dependents working full time at minimum wage would receive an increase of $70, as under the Governor’s proposal.) Compared to the Governor’s proposal, this would reduce the disincentive for moving from half‑time to full‑time work by $226.

Options for Providing Monthly Credits

The administration indicates it would like to provide the EITC in monthly payments but does not have a specific proposal. This section first discusses the potential interaction between providing monthly credits and health and human services programs. Options for providing monthly credits and the trade‑offs associated with those options are then discussed.

Monthly EITC Payments May Interact With Federal Eligibility Rules

Eligibility for Many Human Services Programs Based on Federal Rules. The state and federal governments operate various programs that provide assistance to low‑income individuals and families, including food benefits through CalFresh, monthly cash assistance through CalWORKs, and health insurance through Medi‑Cal. Eligibility for these programs largely is set by federal law and predominantly is based on household income. In addition to eligibility, benefit levels also are set according to income—lower‑income households typically receive larger benefit amounts than eligible households with more income. Household income generally is based on earned and unearned income received on a “recurring basis” like weekly or monthly wages. Lump‑sum tax refunds, however, are not included in the determination of household income for health and human services programs.

Monthly EITC Payments Probably Would Not Affect Benefits. Providing the EITC on a monthly basis could be considered income received on a recurring basis. An increase in income could reduce the amount of assistance individuals and families receive from other programs. However, federal law provides for a specific exclusion of the federal EITC when calculating a household’s income for health and human service programs. This exclusion would more likely than not allow the state to make monthly EITC payments without affecting these benefit programs. There is some uncertainty, however, because no state currently provides monthly EITC payments and the provision has not been tested previously.

Options for Providing Monthly Payments

The state could take a variety of approaches to provide monthly EITC payments. The main considerations are (1) which agency would administer the program and (2) whether the payments should be made in advance or on a deferred basis. Each of these choices has advantages and disadvantages. We summarize each of these approaches in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Options for Providing Monthly Payments

|

Approach |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

|

Franchise Tax Board (FTB) |

FTB authorizes the State Controller to mail a check to the worker (or make a direct deposit) when a worker is owed a tax refund. |

||

|

Advance |

FTB estimates credit amount for current year based on wage information and previous tax returns. |

Could be provided to all eligible EITC recipients. |

Administering monthly EITC may create institutional challenges for tax collection agency. |

|

Less complicated to administer than other options. |

Over payments difficult to recover. |

||

|

Defer |

FTB would authorize refund in monthly installments instead of a lump sum. |

Could be provided to all eligible EITC recipients. |

Unclear why worker would elect monthly payments over lump sum refund. |

|

Least risk of over payments. |

|||

|

Department of Social Services (DSS) |

DSS administers the federal electronic benefits transfer (EBT) system that allows the state to provide food benefits and county welfare departments to issue cash assistance. |

||

|

Advance |

FTB or DSS estimates current credit amount. DSS monthly adds payments to worker’s EBT card. DSS reports credit amount advanced to worker and FTB at end of year. |

Could provide benefits to workers already enrolled in other human services programs. |

Administratively and technically complicated. |

|

Uses existing systems. Familiar to benefit recipients. |

Not all EITC recipients may receive benefits administered by DSS. |

||

|

Over payments difficult to recover. |

|||

|

Defer |

FTB authorizes DSS or county welfare department to issue monthly refund to worker. |

Avoids overpayments. Uses existing systems. Familiar to benefit recipients. |

Administratively complicated. |

|

Not all EITC recipients may receive benefits administered by DSS. |

|||

|

Employment Development Department (EDD) |

EDD administers the state unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and paid family leave programs—which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who are unable to work. |

||

|

Advance |

FTB or EDD estimates current credit amount. EDD makes monthly payments to worker. EDD reports credit amount advanced to worker and FTB at end of year. |

EDD best able to validate workers’ current wages. |

Administratively complicated. |

|

Depending on program design, could provide monthly payments to many EITC recipients. |

Minimal overlap between EITC and EDD program recipients. |

||

|

FTB and EDD already exchange tax data. |

Over payments difficult to recover. |

||

|

Defer |

FTB authorizes EDD to monthly issue refund to worker. |

Administratively complicated. |

|

|

Minimal overlap between EITC and EDD program recipients. |

|||

|

EITC = Earned Income Tax Credit. |

|||

Which Agency Should Administer Monthly Payments? Three state agencies could administer a new program to provide the EITC in monthly payments:

- FTB. As we describe in Figure 8, FTB currently administers the EITC and is responsible for processing tax refunds. FTB authorizes the State Controller to mail a check to the worker (or make a direct deposit) when he or she is owed a tax refund.

- The Department of Social Services (DSS). By administering existing programs that provide assistance to low‑income individuals and families, DSS may be well situated to administer monthly EITC payments. DSS also operates the federal electronic benefits transfer (EBT) system in the state. The EBT system allows the state to provide food benefits and county welfare departments to issue cash assistance to eligible recipients. The existing programs are tightly integrated with other federal and county government agencies, however, which may make adding a new benefit administratively and technically challenging.

- Employment Development Department (EDD). EDD collects wage withholding payments from workers who receive wages and administers the unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and paid family leave programs in the state. In addition to having a close existing administrative relationship with FTB, EDD also pays cash benefits to those recently unemployed.

Should Payments Be Advanced or Deferred? Providing the payments in advance compared to a deferred payment likely would be more helpful to the recipients. Advance payments would create some challenges, however. In particular, workers receiving the EITC have incomes that often vary from one year to another. Accurately estimating the amount of the EITC in advance is difficult and in many instances, the state may either under‑ or overestimate the correct amount to provide workers in a given year. Consequently, a method to true‑up the difference—potentially by adjusting the following year’s credit—could be necessary. Attempts by the state to recoup over payments could create hardships for those affected. Program design should balance the benefit amounts with avoiding inaccuracies and large overpayments.

Conclusion

Expanding the EITC would provide benefits to low‑income workers. There are a variety of approaches to helping these workers beyond those proposed by the Governor depending on the Legislature’s priorities. The extent to which the Legislature wishes to prioritize reducing poverty, increasing workforce participation, or encouraging full‑time work should drive the ultimate design of the expansion.