LAO Contact

March 22, 2019

Older Youth Access to Foster Care

- Introduction

- Background

- Determining Whether Foster Care Access Issues for Older Youth Exist

- LAO Comments and Recommendations for Legislative Next Steps

Summary

Supplemental Report Language (SRL) Required LAO to Report on Differences Accessing Foster Care for Older Youth Compared to Younger Youth. During deliberations on the 2018‑19 budget package, the Legislature directed our office to review data about the reporting of child abuse and neglect—which we refer to as maltreatment in this report—for older youth (ages 14 to 17) compared to younger youth (ages 0 to 13). Using publicly available data from the California Child Welfare Indicators Project (CCWIP) and specially requested data from the Department of Social Services (DSS), we examined and compared maltreatment reporting data for older and younger youth along multiple dimensions to take a closer look at whether youth in the two age groups experience differences in accessing foster care.

Available Data on Maltreatment Reports Show Some Differences Between Older and Younger Youth in Accessing Foster Care . . . Based on available data, maltreatment reports for older and younger youth show some differences. Principally, we find that maltreatment substantiation rates—a necessary report investigation finding before a youth can enter foster care—for older youth have consistently been below younger youth. Notably, this gap appears to be the result of two differences in the outcomes of older and younger youth maltreatment reports: (1) maltreatment reports for older youth are determined to not require an in‑person investigation at higher rates than reports for younger youth, and (2) fewer maltreatment reports for older youth are determined to be substantiated following an in‑person investigation than for younger youth. Despite these differences, older and younger youth have largely equivalent rates of entry into foster care following a maltreatment substantiation.

. . . But It Is Uncertain Whether These Differences Are Indicative of Any Problem. Despite some observed differences in outcomes between older and younger youth in accessing foster care, it remains difficult to make more definitive conclusions about why these differences may exist. This is in part due to limitations in the available data. For example, while we know that older youth have lower maltreatment substantiation rates, we do not know the specific reasons for this. We also note that it might be reasonable for some moderate differences in report outcomes for older and younger youth to exist, given that older youth may experience different levels of risk compared to younger youth in similar situations.

Recommend Collecting Additional Data to Better Understand Differences. Given these uncertainties, we recommend collecting additional information—which we understand is currently not collected on a statewide, systematic basis—to better inform the reasons for any differences between older and younger youth with reports for maltreatment. We provide a list of suggestions for additional data collection at the end of this report.

Introduction

The Supplemental Report of the 2018‑19 Budget Act requires our office to review data about the reporting of child maltreatment incidents among children who are ages 14 to 17. Child maltreatment, for the purposes of this report, means parental behavior that results in serious abuse or neglect of a child. To determine whether older youth have more challenges accessing foster care than younger youth, SRL directs us, where feasible, specifically to compare older and younger youth on the following dimensions:

- Rate of reporting.

- Outcomes of reporting.

- Sources of reports, if available, including self‑reported maltreatment.

- Living situations, including homelessness or living with a parent or guardian, at the time of the report, if available.

- Number of petitions filed under Welfare and Institutions Code (WIC) 329, and time frame of the filing, if available.

- Percentage of reports that involved children with prior reports of maltreatment.

- Generalized outcomes of prior maltreatment reports.

This report fulfills this requirement to the best of our ability, given data limitations discussed below.

Significant Data Limitations. A significant challenge in assessing whether older youth have more challenges accessing foster care than younger youth is the limitation of available data. In performing our analysis, we relied heavily on publicly available data from CCWIP and specially requested data from DSS. At the time of this analysis, not all of the data elements requested by the SRL were available through CCWIP and DSS. As such, although we were able to answer some of the questions posed by the Legislature, we were unable to fully address others.

Background

Below, we provide background on the Child Welfare Services (CWS) system—specifically with regard to the maltreatment report system and the pathway into foster care. For the purposes of this report, we refer to children ages 14 to 17 as older youth and children ages 0 to 13 as younger youth.

Child Welfare Services System

The CWS system works to protect children by investigating reports of child maltreatment, removing children from unsafe homes, providing services to children and families to safely reunify foster children with their families, and finding safe placement options for children who cannot be safely reunified with their families. The principal goals of the CWS system are to promote the safety, permanency (in family placements), and well‑being of youth affected by child maltreatment. The CWS system spans across federal, state, and county governments.

Responsibilities of Federal, State, and County Governments

The Federal Government Has a Broad Oversight Role. The federal government enacts child welfare laws and policies that require (or provide incentive funding for) state compliance. The federal government evaluates each state’s CWS program outcomes based on several performance measures. The federal government also audits state spending of federal CWS funds, sets policy priorities and requirements for using federal CWS funds, establishes program improvement goals for states that fail to reach federal performance targets, and issues funding penalties for noncompliance with federal policies and program performance targets.

The State Supervises County CWS Agencies. The federal government gives states some flexibility in how they operate their CWS programs. Unlike some other state CWS programs which are state administered, California’s CWS program is state supervised and county administered. DSS is the state agency responsible for oversight of the CWS program. DSS develops program and fiscal policies for CWS, provides technical assistance and training to counties, receives federal CWS funding and distributes these funds to the counties, monitors county CWS program performance, and collaborates with counties to establish program improvement goals.

Counties Are Primarily Responsible for Administering Child Welfare Services. Under the supervision of DSS, county CWS agencies provide the frontline administration of the CWS system, including: (1) Receiving reports of child maltreatment, (2) investigating maltreatment reports, (3) removing children from unsafe homes, (4) finding and funding placements for children in foster care, (5) providing services to families for reunification, and (6) finding permanent adoptive parents or guardians for children who cannot be safely reunified with their families. In addition to county CWS agencies, county probation agencies perform case management (including family reunification and placement services) for foster children who are also involved in the juvenile justice system. The state provides county CWS agencies with flexibility in how they operate their local CWS program, and therefore there is some variation in administration and services offered among county CWS agencies.

Juvenile Dependency Courts Make Significant Decisions Over Placement and Services for Children in the CWS System. In addition to county CWS agencies, juvenile dependency courts (a division within each county’s superior court) have jurisdiction over the removal, foster care placement, and permanent placement decisions for children involved in the CWS system. Juvenile dependency courts hold a series of hearings that determine how a child moves through the CWS system.

Pathway for Entry Into Foster Care

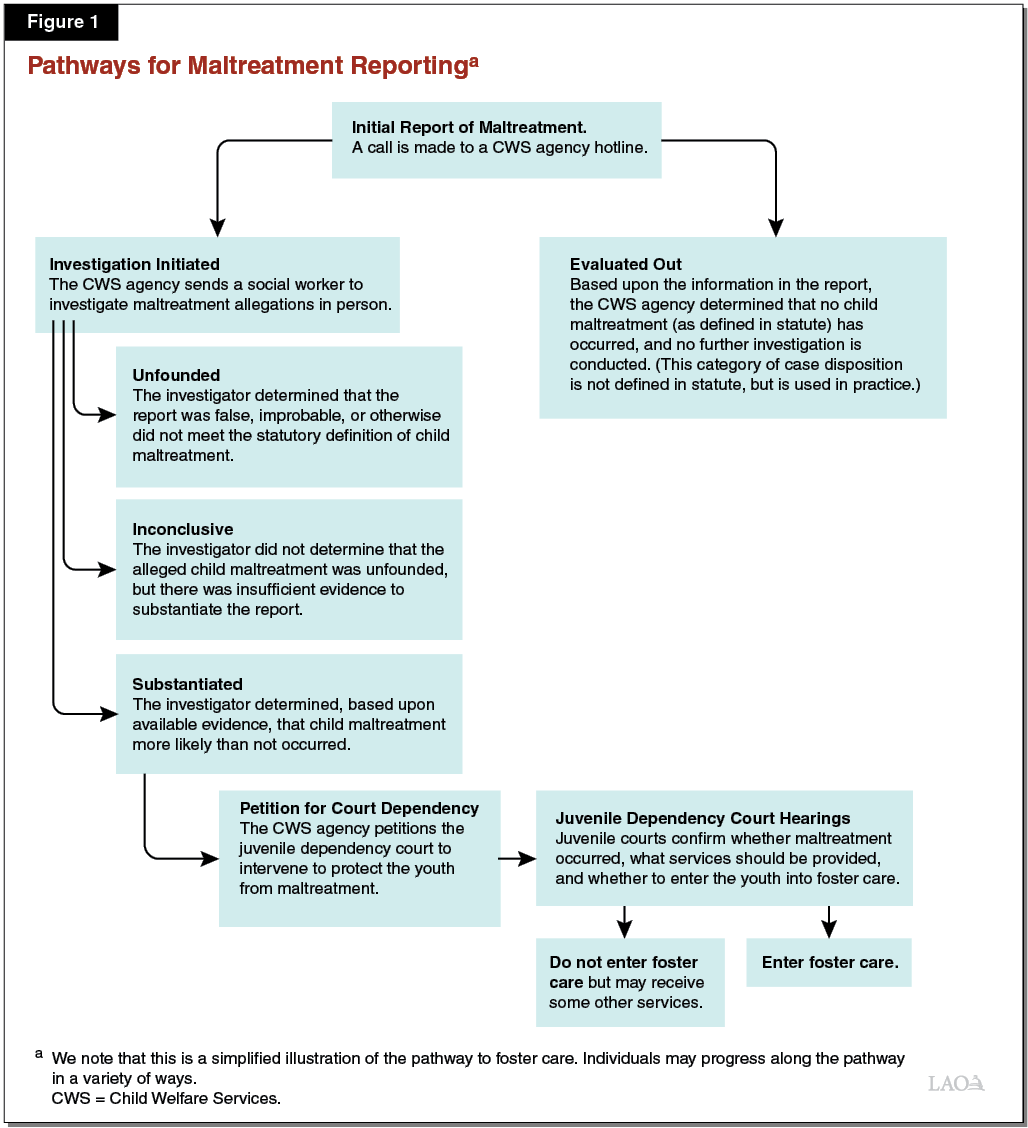

At a high level, Figure 1 provides a simplified display of the basic process and defines the types of outcomes that can result once a report of maltreatment is made to a CWS agency. In the section that follows, we describe this pathway to foster care after a maltreatment report.

Reporting of Child Maltreatment Begins the Process of Entering Court Dependency and Foster Care. When a county CWS agency receives a report of suspected child maltreatment to its reporting hotline, county CWS social workers review information provided in the report and decide whether to conduct an in‑person investigation to determine if the alleged child maltreatment is “substantiated”—has actually occurred as defined in state law—or to “evaluate out” the report and not pursue further investigation of maltreatment. State law defines multiple categories of child maltreatment: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, general neglect, severe neglect, exploitation, caretaker incapacity, and sibling abuse. The following is a description of the different types of child maltreatment as defined in statute.

- Physical abuse is willful bodily injury inflicted upon a child.

- Sexual abuse is victimization of a child by sexual assault. Sexual assault includes child molestation, fondling, rape, or incest.

- Emotional abuse is unjustifiable mental suffering inflicted upon a child that endangers the child’s health and results in certain behavioral disorders such as severe anxiety, depression, withdrawal, or aggressive behavior.

- General neglect is the failure of a parent or caretaker to provide a child with adequate food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision.

- Severe neglect is negligent care by a parent or caretaker of a child that results in a child’s medically diagnosed poor physical or emotional development. Severe neglect includes a parent’s or caretaker’s failure to protect a child from severe malnutrition.

- Exploitation is the sexual trafficking of a child.

- Caretaker incapacity is a condition in which a child has been left without any provision for support for such reasons as (1) physical custody of the child has been voluntarily surrendered, (2) the child’s parent has been incarcerated or institutionalized and cannot arrange for the care of the child, (3) a relative or other adult custodian with whom the child resides is unwilling or unable to provide care or support for the child, and (4) the whereabouts of the parent are unknown and reasonable efforts to locate the parent have been unsuccessful.

- Sibling abuse refers to an unacceptable risk of abuse or neglect of a child which is indicated by the abuse or neglect suffered by that child’s sibling.

The Structured Decision Making (SDM) Tool Is Designed to Aid Social Workers in Assessing Reports of Maltreatment. The SDM tool is a standardized tool utilized by county social workers to assist in accurately assessing risk and making prudent decisions on whether and how to intervene in families on behalf of children with maltreatment reports. The SDM tool provides social workers with a structure for analyzing the information provided in maltreatment reports and determining appropriate actions to be taken regarding the family in the report—for example whether to evaluate out the report or continue to investigate. Social workers consider various factors such as age and developmental status when deciding whether reported information constitutes maltreatment. While the SDM tool is designed to provide social workers with a comprehensive and accurate assessment of risk to a child, social workers have the ability to use their professional discretion to override the outcome of the SDM tool either to evaluate out a report or initiate an in‑person investigation of a maltreatment allegation. Counties began gradually implementing the SDM tool in 1998, with statewide implementation of the tool completed in 2016.

In‑Person Investigation Results in One of Several Outcomes. As shown in Figure 1, once an in‑person investigation is initiated, the maltreatment report can be found to be (1) unfounded, (2) inconclusive, or (3) substantiated. Substantiated reports require further action by the CWS agency through court proceedings, which can result in either the agency providing court‑ordered supportive services to the child and family or, if there is unacceptable risk to the child’s safety, the CWS agency removing the child from the home and placing the child in foster care.

Children Enter Court Dependency Through Court Petitions. Section 300 of the WIC (hereafter referred to as WIC 300) provides the legal procedures for youth to come under the dependency of juvenile courts—whereby parental rights are limited and the court can require the family to receive certain services or even remove the youth out of the home and into foster care for the safety of the youth. Generally, for a youth to enter court dependency and foster care a county CWS agency social worker must file a petition to the juvenile dependency court under WIC 300—which lists the various forms of maltreatment that qualify a youth to come under court dependency—after investigating and substantiating a report of child maltreatment.

Section 329 of the WIC (hereafter referred to as WIC 329) entitles anyone who reports child maltreatment, including the child, to receive notification of the social worker’s decision to file or not file a dependency petition to juvenile court following an investigation. If the social worker declines to file a dependency petition or fails to notify the reporter, the reporter or the child’s attorney may submit a Section 331 of the WIC (hereafter referred to as WIC 331) petition to have the juvenile court review the social worker’s decision and either affirm that decision or require the social worker to submit a dependency petition.

Juvenile Courts Make Final Decisions on Court Dependency and Foster Care for Children. Juvenile dependency courts have jurisdiction over children in the CWS system and make the final decision on placement and services for the youth. Through case review and a series of hearings, juvenile dependency courts decide: (1) if child maltreatment occurred as alleged by the CWS agencies, (2) if youth removed from their home due to maltreatment should be returned home or remain in foster care, (3) what services children and families receive, (4) where children in foster care are placed, (5) when or if parental rights are terminated, and (6) permanent placement plans for foster children where reunification is not possible.

Once in Foster Care, Youth May Remain Until Age 21. CWS agencies serve youth and families in foster care with various support services with the goal of safely reunifying the child and family. Examples of such services include counseling, parent training, and mental health or substance abuse treatment. In addition to case management services, CWS agencies provide foster caregivers with monthly financial grants. State policy is to return children to their families whenever safe and possible, and these services are designed to address family issues that led to the child’s removal and provide an opportunity for the child’s safe return home.

Permanent placement provides case management and placement services to foster children who cannot be safely reunified with their families. Placement services include facilitating a child’s adoption, guardianship, or, in some cases, long‑term foster care placement. When a child cannot be safely reunified with their family, state policy is to provide a child with a permanent adoptive parent or guardian as soon as possible (with placement preference with other members of the child’s family).

In recent years, counties have increasingly relied upon Supervised Independent Living Placements (SILPs) and transitional housing placements instead of foster parents and more institutionalized congregate care settings for older, relatively more self‑sufficient youth. SILPs are independent settings, such as apartments or shared residences, where nonminors who remain in foster care past their 18th birthday may live independently and continue to receive monthly foster care grant payments. Transitional housing placements provide foster youth ages 16 to 21 foster care grant payments and supervised housing as well as supportive services, such as counseling and employment services, that are designed to help foster youth achieve independence.

Determining Whether Foster Care Access Issues for Older Youth Exist

The Supplemental Report of the 2018‑19 Budget Act directs our office to examine whether certain differences exist in whether and how older youth—as compared to younger youth—are accessing foster care in the state based on available data. We understand that there is concern among certain youth advocates involved in the state’s CWS system that there may be systemic issues hindering the ability of older youth to access foster care even if they need it. In accordance with SRL, we examined the rates, types, and outcomes of maltreatment reporting for children in older (ages 14 to 17) and younger (ages 0 to 13) age groups—with available population data from CCWIP and DSS—to see what differences exist between the age groups and whether any inferences can be made from the available data regarding the treatment of older youth in the state’s child welfare services system.

Analysis of Available Statewide Data

Below, we offer our comparative assessment of maltreatment report data on rates of reporting, report substantiation rates, and foster care entry rates following a report substantiation for older and younger youth. We first examine publicly available data from CCWIP for overall trends for the state as a whole.

Overall Outcomes of Maltreatment Reports for Older and Younger Youth

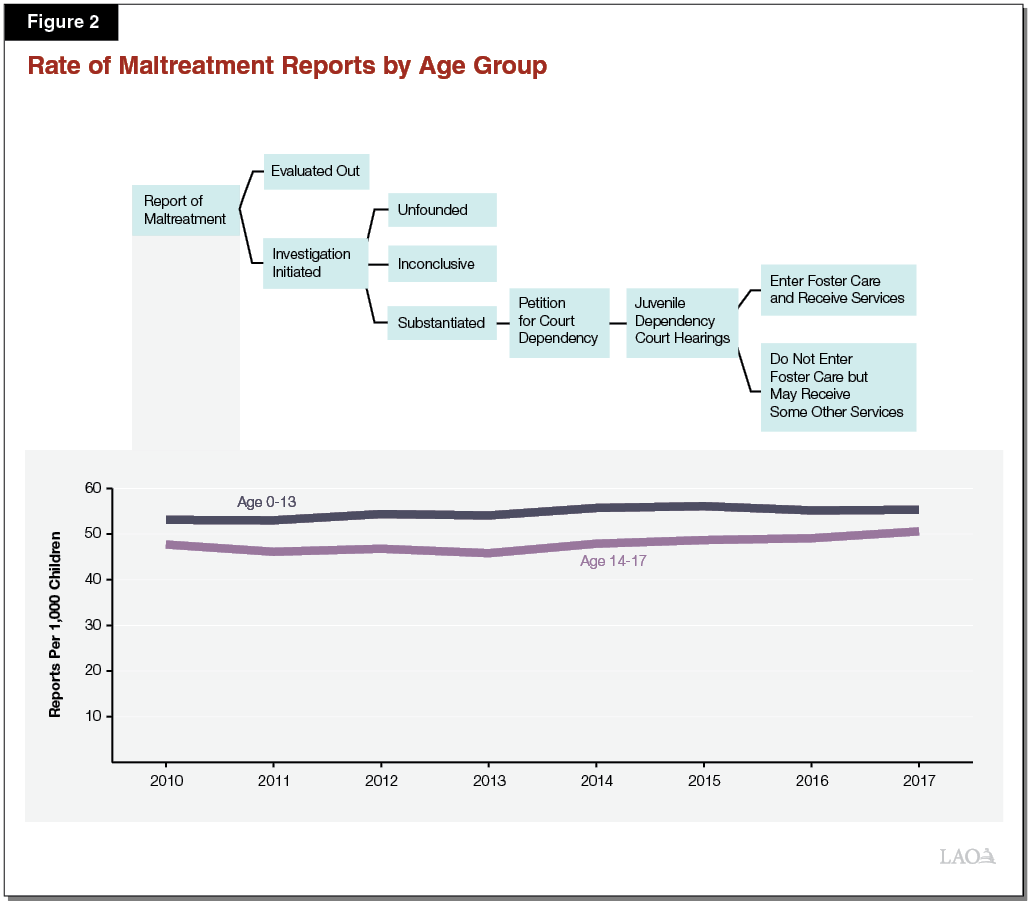

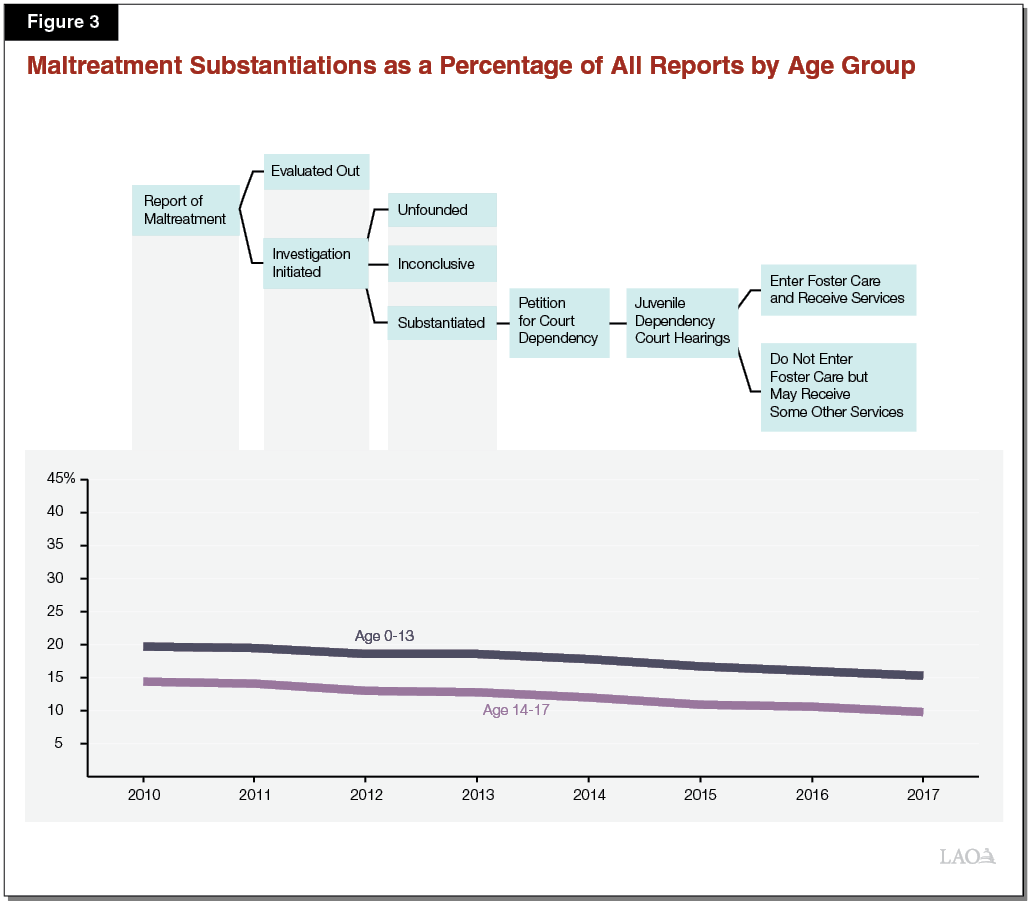

Older Youth Have a Consistently Lower Rate of Maltreatment Reports as Well as Substantiations, Relative to Younger Youth . . . Figure 2 and Figure 3 show a consistent gap between older and younger youth in both reporting and substantiation rates. Figure 2 shows that, since 2010, the rate of maltreatment reports made—the first step in the reporting process in Figure 1, and measured by the number of maltreatment reports per 1,000 children in the state—for older youth have been lower by about five reports per 1,000 children compared to the rate for younger youth. Figure 3 shows that older youth have also maintained a lower rate of maltreatment substantiations for all reports by between 5 percent and 6 percentage points in any given year relative to the rate for younger youth.

Due to the sustained difference over this time period between older and younger youth when it comes to the percentage of cases that are substantiated, we decided to take a closer look at substantiation rates by age. Specifically we found a consistent relationship between increasing age and incrementally decreasing substantiation rates. In other words, infants had higher substantiation rates than elementary school aged youth, who had higher substantiation rates than middle school aged youth, who in turn had higher rates than high school aged youth. Consistent differences in substantiation rates, therefore, occur not only between older teenagers and younger children, but are a pattern that can be observed across the entire age spectrum for youth in the state. This was not the case with the rates of maltreatment reports made or entry rates into foster care following a substantiation, which did not display the same type of decrease with increasing age.

. . . But Maltreatment Report Rates and Substantiations for Older and Younger Youth Show Parallel Trends Over Time. While older and younger youth have displayed consistent differences over time in their rates of reported maltreatment and substantiations of maltreatment, the figures also show that the rates of maltreatment reports and substantiations for both older and younger youth have generally moved in the same direction with similar magnitudes. Figure 2 shows that, over an eight year period, the rate of maltreatment reports for both age groups has increased by less than five reports per 1,000 children in each age group. Similarly, Figure 3 shows that the rate of maltreatment substantiations for all reports has decreased for both age groups by less than 5 percentage points over the same period.

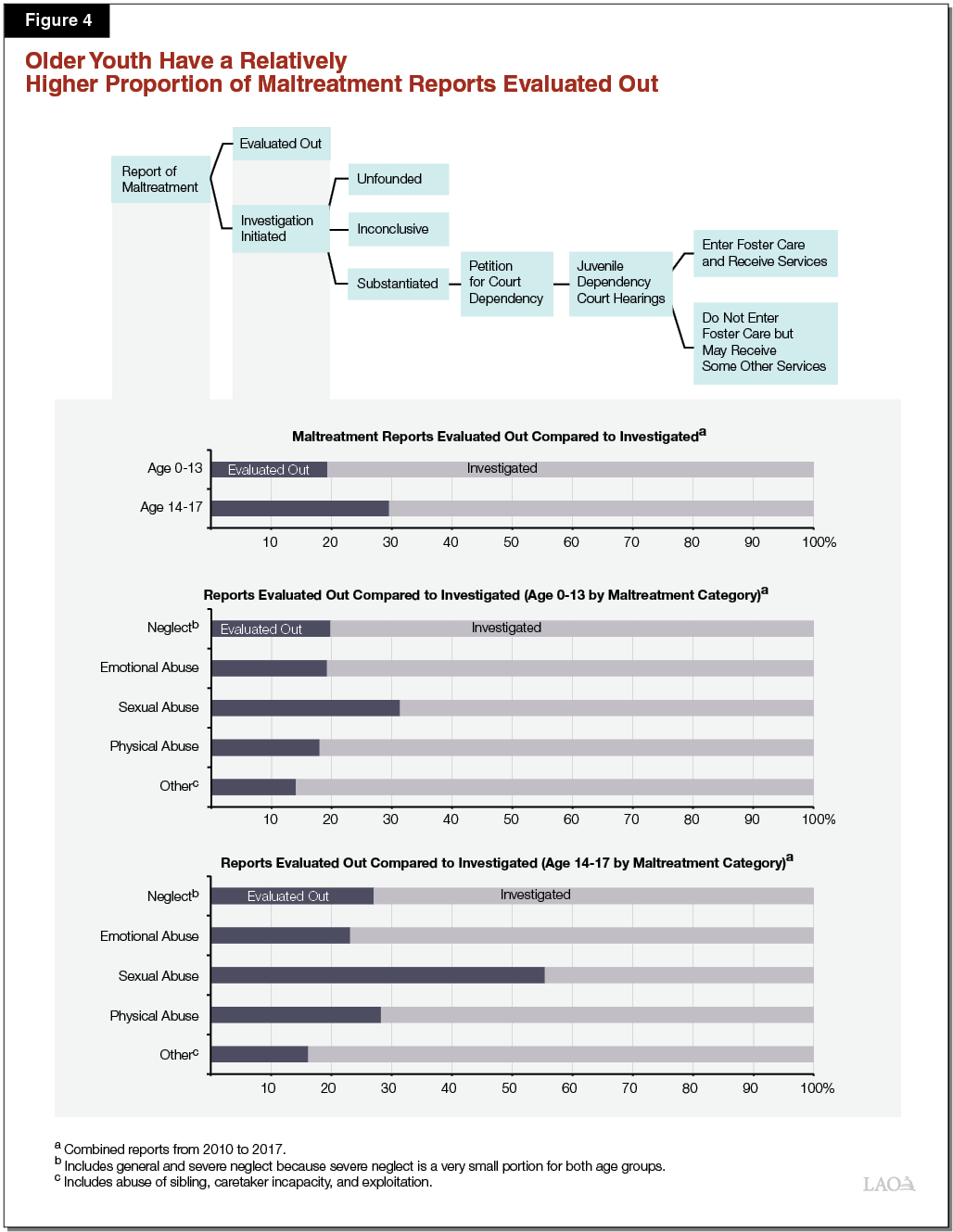

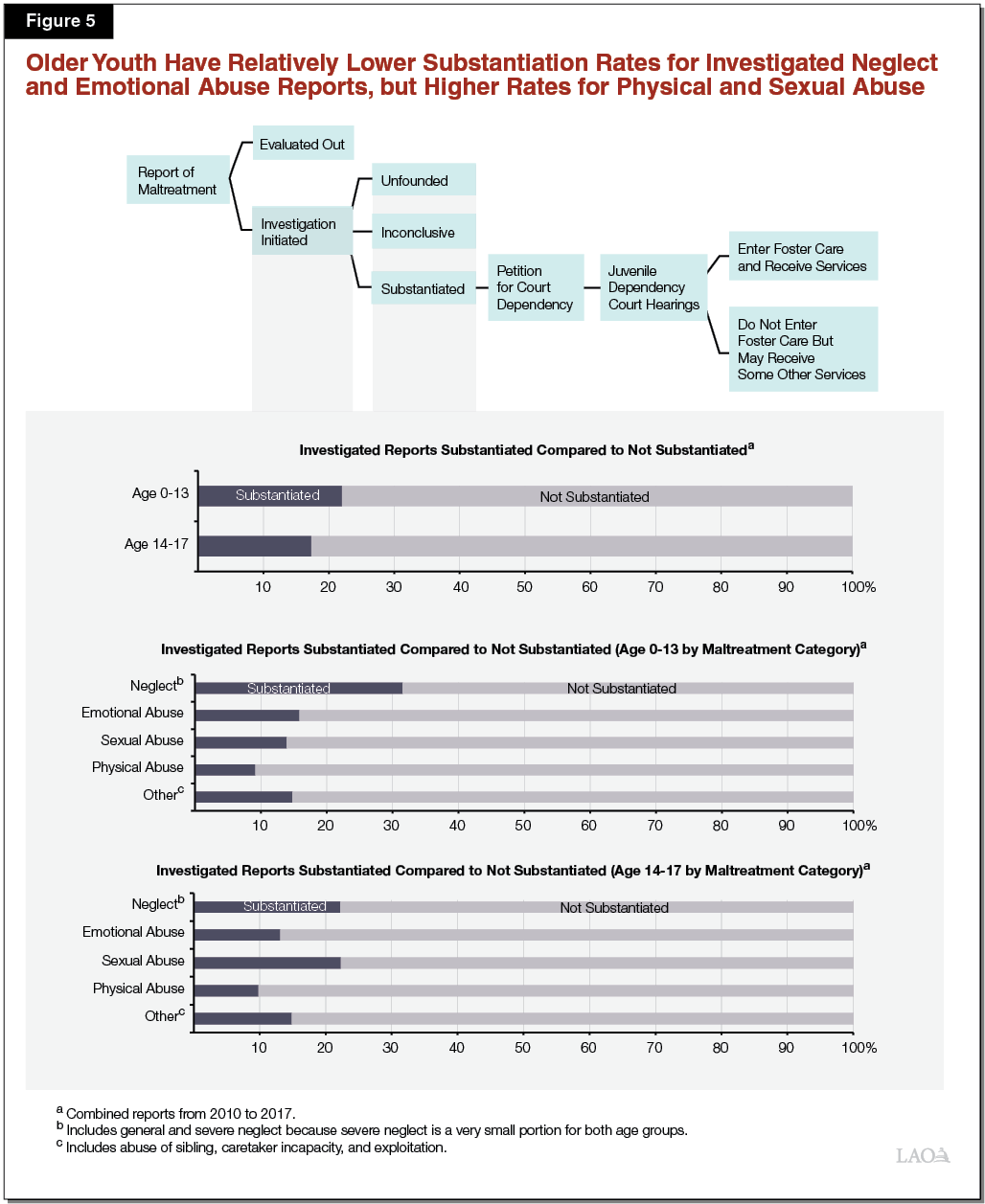

Lower Overall Substantiation Rates for Older Youth Correspond to Higher Rates of Reports Evaluated Out. As shown in Figure 4, overall about 19 percent of maltreatment reports for younger youth were evaluated out from 2010 to 2017, compared to about 30 percent for older youth. As Figure 1 shows, there are two points in the process after a maltreatment report is made where it may not be substantiated. First, a report may not be substantiated if it is evaluated out without further investigation. Second, it may not be substantiated after an in‑person investigation if it is found to be inconclusive or unfounded. Figure 4—which includes the reporting data from 2010 to 2017—displays more detail on the step where maltreatment is reported and a decision is made on whether to evaluate it out or initiate an investigation. It shows that for each category of maltreatment report, older youth had a relatively higher proportion of those reports evaluated out, especially for sexual and physical abuse, than younger youth.

After an Investigation, Older Youth Also Have Higher Rates of Maltreatment Reports That Are Not Substantiated. As shown in Figure 5, overall 22 percent of all maltreatment reports that were investigated for younger youth were substantiated from 2010 to 2017 compared to about 17 percent for older youth. Figure 5 provides more detail on report outcomes at the second step where an investigation is conducted and the report is determined either to be substantiated or to be not substantiated (unfounded or inconclusive). The figure shows that of those maltreatment reports that were investigated, older youth had a lower proportion of their neglect and emotional abuse reports substantiated than was the case for younger youth. However, older youth also had a slightly higher proportion of their investigated physical abuse reports substantiated and a higher percentage of their investigated sexual abuse reports substantiated than younger youth. Older and younger youth had roughly the same substantiation rates for other types of maltreatment.

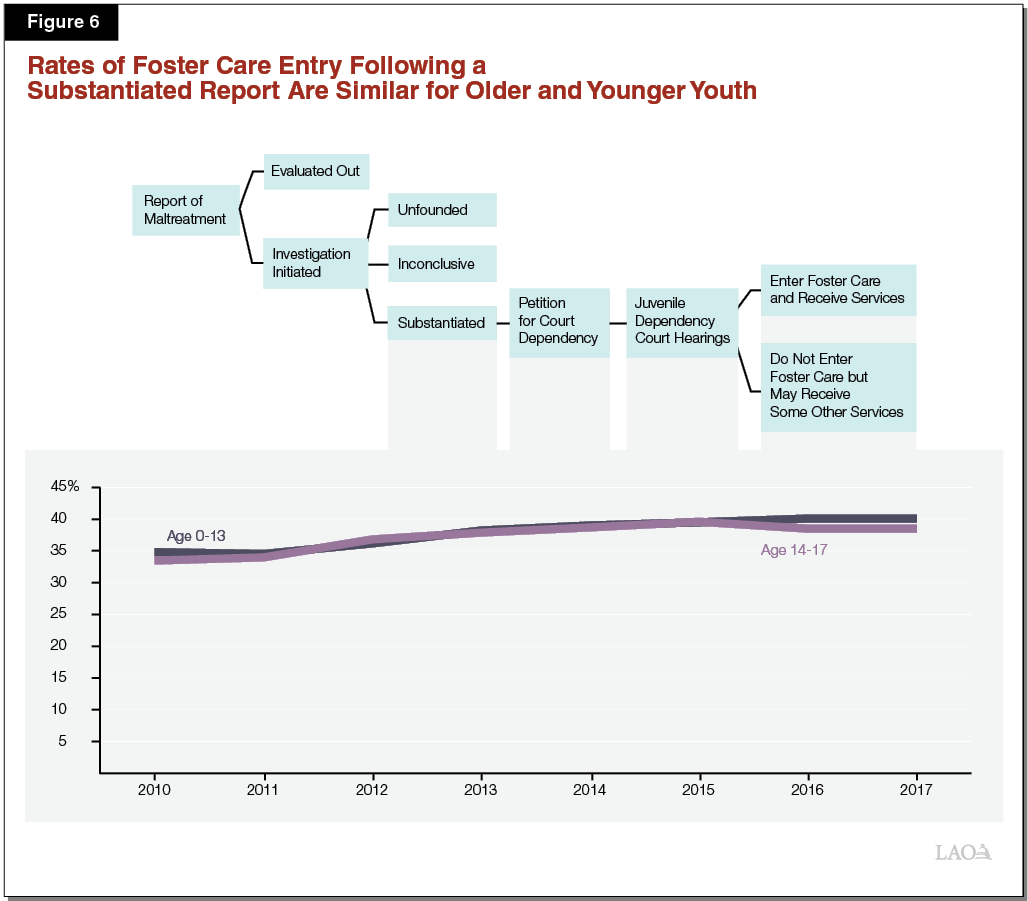

Following a Substantiation, Older Youth Have Largely Equivalent Rates of Entry to Foster Care as Younger Youth. While there are some differences in report and substantiation rates between older and younger youth, Figure 6 shows that following a substantiation of maltreatment, older and younger youth have had similar rates of entry into foster care over time. The rate of substantiated allegations resulting in a child’s entry into foster care have increased for both age groups by about 5 percentage points between 2010 and 2017.

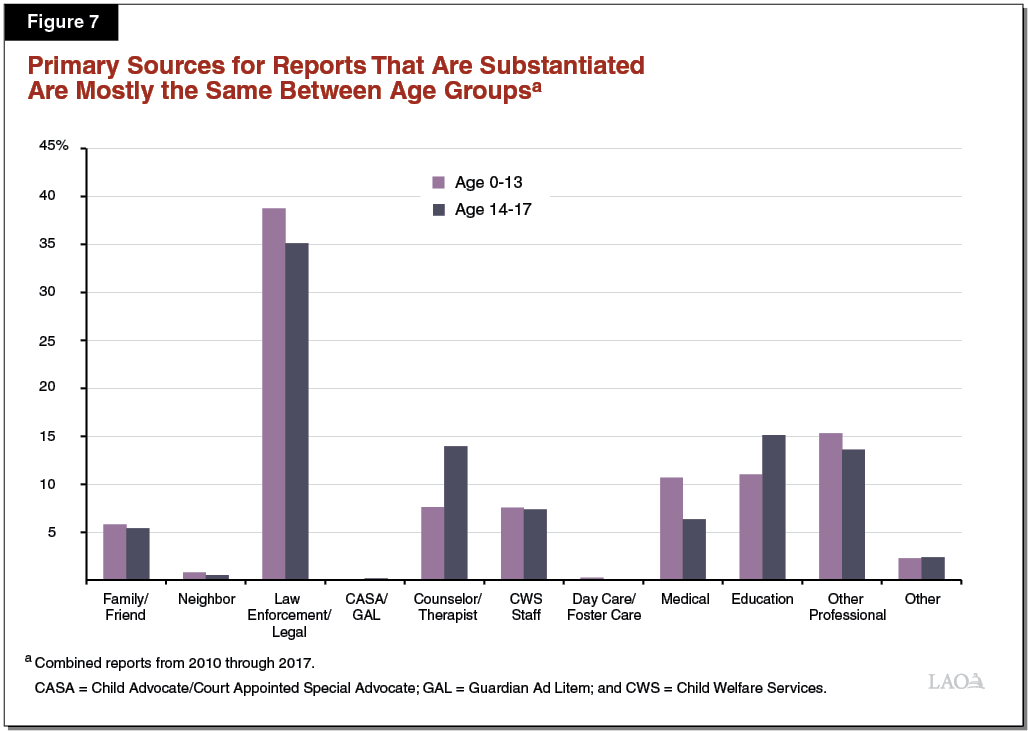

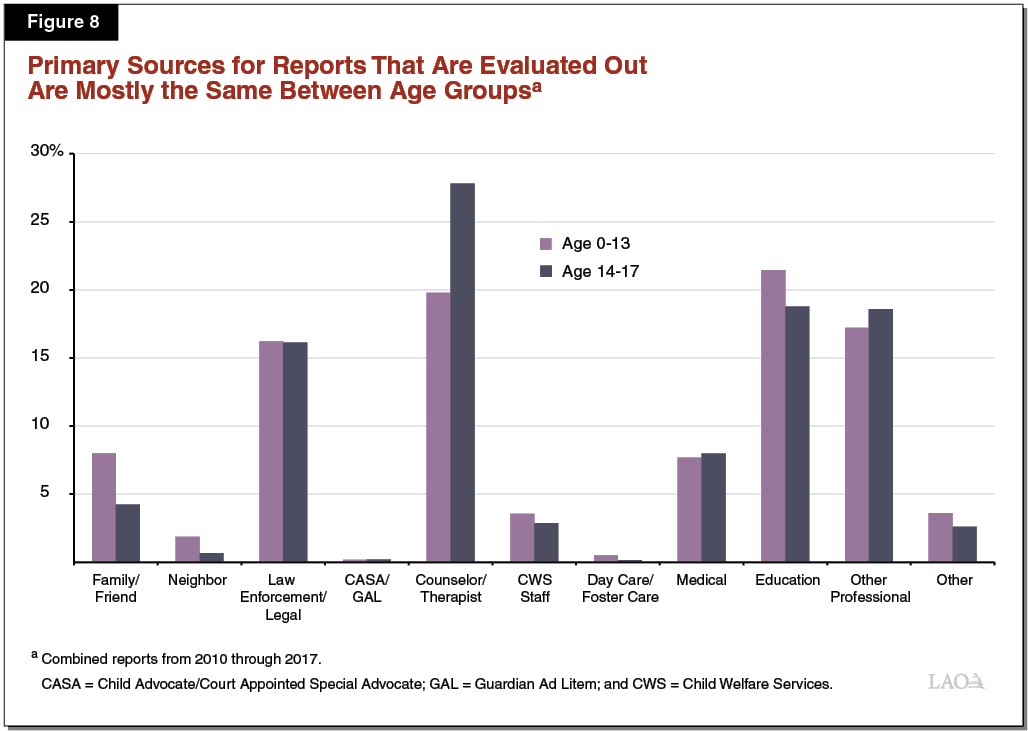

Maltreatment Reports for Older and Younger Youth Come From Largely the Same Sources. The SRL asked us to determine whether maltreatment reports coming from different sources lead to different outcomes for older youth compared to younger youth. Reports of child maltreatment to county CWS agencies come from a variety of sources, including education professionals, law enforcement, medical professionals, and friends or family members of the child. Available data from CCWIP indicate that maltreatment reports for older and younger youth primarily come from the same types of reporting sources in fairly similar overall proportions. Figure 7 shows what proportion of substantiated maltreatment reports for older and younger youth come from different reporting sources. Figure 8 displays the same information for maltreatment reports that are evaluated out. The two figures show that when a report is evaluated out or substantiated, the source of the maltreatment report is primarily the same between the age groups. We note that both age groups mostly overlap in terms of which of their report sources provide many of their maltreatment reports and which of their report sources provide few of their maltreatment reports. To the extent that there are notable differences between the age groups in this regard, the most significant is that older youth tend to have a higher proportion of reports coming from counselors and therapists. As shown in Figures 7 and 8, this also holds true when examining sources of substantiated reports and sources of evaluated out reports.

Determining Whether Data for Certain Subpopulations Based on Ethnic Group or Geographic Region Show Differences From Statewide Averages

As part of our analysis, after analyzing older and younger youth maltreatment reporting data for the state as a whole, we then looked at available CCWIP data for certain geographic regions and ethnic groups. Our purpose was to determine whether older and younger youth within certain subpopulations experienced significant differences in accessing foster care that were different than statewide aggregated data. Below, we describe the particular subpopulations and explain what we found.

Differences in Outcomes Between Older and Younger Youth Do Not Appear to Be Accentuated in Observed Geographic Locations Compared to the State Overall. The regions we investigated further include the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles County, a selection of counties in the Inland Empire and Imperial Valley, a selection of counties in the San Joaquin Valley, and a selection of counties in the rural north of the state. In doing this analysis, we did find there were differences in outcomes across regions. In other words, some regions had higher or lower overall substantiation rates and rates of entry into foster care after a substantiation than other regions. Despite these differences, however, we found the size of the differences between older and younger youth in each region observed to be similar to the differences we found for the overall population. For example:

- While inland counties tended to have generally higher maltreatment report rates than coastal counties, this was true for both age groups in roughly similar magnitudes as the state overall.

- Los Angeles County had higher overall substantiation rates compared to most other counties we examined and the San Joaquin Valley counties had lower substantiation rates than most other counties—both by about 5 percentage points in any given year between 2010 and 2017. However, again this difference applied equally to younger and older youth.

- Inland and Bay Area counties also typically had higher rates of entry into foster care after a substantiation than most other counties—with differences ranging in the single digits to more than 20 percentage points higher depending on the region. These higher rates applied at least as much to older youth as to younger youth.

Differences in Report Outcomes Between Ethnic Groups Tend to Hold Across Age Groups. Likewise, we examined data for different ethnic groups to see if any ethnic groups displayed significant differences in outcomes between older and younger youth that might not be detectable when reviewing aggregated statewide data. As with the geographic regional data, we found little evidence of significant differences between age groups within specific ethnic groups that were not also shown in statewide data. Black and Native American youth tended to have higher rates of maltreatment reports, substantiations, and entries into foster care than youth belonging to other ethnic groups regardless of whether they were older or younger.

Analysis of Data for Specified Subpopulation Characteristics

After analyzing available CCWIP data on the overall population of younger and older youth with maltreatment reports, we requested additional data from DSS in order to investigate maltreatment report outcomes for the subpopulations of (1) homeless youth and (2) youth with a maltreatment report who had prior maltreatment reports to CWS. Although we were able to identify some data for these youth, described more fully below, we note that there are significant data limitations that prevent us from making any definitive findings related to these subpopulations.

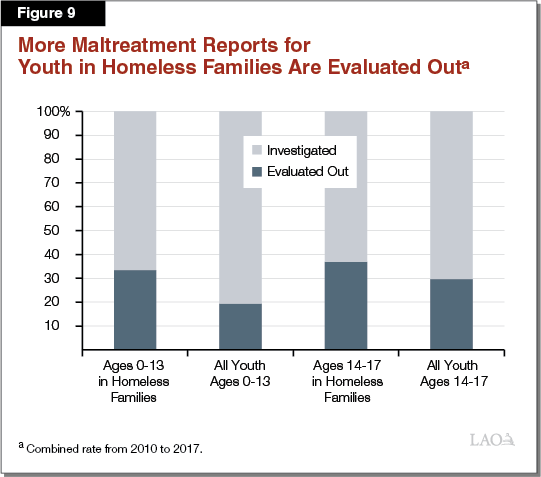

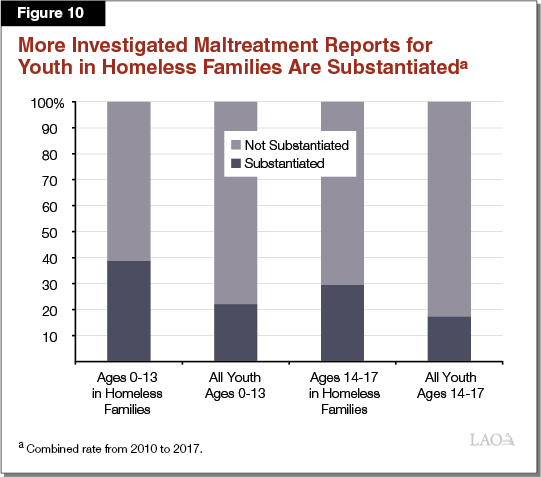

Available Data on Youth in Homeless Families Show Some Similar Trends to Youth Overall, but Also Indications of Some Differences. Although the SRL directs our office to determine whether older homeless youth access foster care at different rates than younger homeless youth, it is our understanding that the data to fully perform this analysis is not available. Instead, we note that the available data referenced in this section is for homeless families, which would not capture children who are themselves homeless, though belonging to a family that is not homeless. Accordingly, while we cannot provide an analysis of foster care access for all older and younger homeless youth, we can describe some relevant observations for a subset of this population—youth in homeless families—relative to older and younger youth overall. Maltreatment reports for youth who are in homeless families increased between 2010 and 2017 just as it did for children overall. These youth in homeless families represented less than 1.7 percent of all children with maltreatment reports in 2017—this is up from about 0.5 percent in 2010. Substantiation rates for older and younger youth in homeless families showed similar trends to youth overall—substantiation rates for both age groups declined over time by between 5 percentage points and 10 percentage points over the same time period, as was the case for the broader population of youth. Of note, however, both older and younger youth in homeless families displayed higher overall rates of reports being evaluated out than youth overall, as can be seen in Figure 9. However, Figure 10 shows that a greater proportion of investigated reports for both older and younger youth in homeless families were substantiated relative to youth overall, with younger youth having the higher substantiation rate. This suggests that while reports for youth in homeless families are somewhat more likely to be evaluated out, those reports that do receive an in‑person investigation are more likely to be substantiated than reports for youth overall. Unfortunately, in time for this analysis, we were unable to obtain comparable data that showed the entries into foster care after a substantiation for youth in homeless families over the same time period.

Data on Youth With Prior Reports Is Limited. While we were able to obtain data showing that a greater proportion of older youth with current maltreatment reports had prior reports in their history, we were unable to obtain data on the outcomes of those prior reports. We were also unable to determine whether youth in either age group with prior reports were more or less likely to have a current report substantiated or to enter foster care.

Summary of Key Data Gaps

As mentioned in previous sections, not all of the data is currently available to enable us to fully investigate some of the requested information in the SRL. Here we provide a summation of key data gaps that impacted our analysis for the SRL. We note that pointing out these current data gaps is not meant to be a critique of the administration or the counties, as they are not data elements that have previously been requested or required.

- Lack of Complete Data Related to Decision Making Processes. We lack certain data that would provide greater context to the available data on maltreatment report outcomes. Specifically, in time for this analysis we did not have information on how report determinations were made, such as whether the SDM tool was overridden by social workers (as allowed) more for one age group than the other during the time period we examined. Additionally, data on the most common reasons for reports to be evaluated out for different age groups is not available. We further lack data on the court processes that would occur after an investigation. This type of data would show the prevalence with which certain WIC code petitions—such as petitions under WIC sections 329 and 331—are invoked for older and younger youth and how often they result in an entry into foster care. We also do not have data which distinguishes between maltreatment reports for youth who self‑report—or claim maltreatment—and those for whom maltreatment is observed by others. This lack of detail regarding these types of process‑related data hinders our ability to fully determine to what extent older and younger youth have different experiences accessing foster care.

- Lack of Complete Data Related to Certain Subpopulations. The data available for homelessness is for homeless families, which does not fully capture children who are themselves homeless, though belong to a family that is not homeless. Likewise, data on youth with prior reports lists how many prior reports youth with a current maltreatment report have, not the outcomes for either those prior reports or the current reports. These data gaps significantly preclude our ability to determine how these subpopulations of youth access foster care services compared to the broader population of youth, and accordingly our ability to make comparisons between older and younger youth in these subpopulations.

LAO Comments and Recommendations for Legislative Next Steps

Limited Ability to Draw Definitive Conclusions Based on Available Data

Some Differences Exist Between Report Outcomes for Older and Younger Youth, Which Warrant Further Investigation . . . Based on our analysis of available data, certain consistent differences are worthy of further investigation to determine whether older youth in the state experience greater difficulty gaining access into foster care. In particular, maltreatment report substantiation rates for older youth have consistently been below younger youth, even as both age groups have experienced the same overall decline over time. Notably, this difference appears in two steps in the reporting process. First, a higher proportion of maltreatment reports for older youth are evaluated out—especially abuse reports—resulting in fewer reports for older youth receiving an in‑person investigation than reports for younger youth. Second, older youth have an overall higher proportion of investigated reports not substantiated—though this is not the case for sexual and physical abuse. Even though older and younger youth have largely equivalent rates of entry into foster care following a maltreatment substantiation, lower substantiation rates for older youth result in fewer entries into foster care per report of maltreatment compared to younger youth. We do note that notwithstanding these consistent differences, older and younger youth referred to CWS agencies generally experienced similar trends in reporting outcomes over time in key categories, such as increasing maltreatment report rates, decreasing overall substantiation rates, and increasing rates of entry into foster care following a substantiation. These trends held true even when controlling for other factors such as geographic location and ethnic group identity.

. . . But It Is Uncertain Whether These Differences Are Indicative of Any Problem. While we believe that some consistent, sustained differences in report outcomes for older and younger youth are noteworthy and merit further investigation, we also note that it may be reasonable for some moderate differences in report outcomes between older and younger youth to exist. Given that older youth are inherently at least somewhat more independent and capable than younger youth, it is possible that certain family situations that constitute unacceptable risk for younger youth, might not constitute the same level of risk for older youth. It is also worth noting that consistent incremental differences in maltreatment substantiation rates occur not only between older teenagers and younger children, but are a pattern that can be observed across the entire age spectrum for youth in the state—and therefore might be due to factors that do not uniquely affect youth ages 14 to 17 compared to all other youth.

Certain Categories of Data Are Unavailable or Lack Detail. Some of the difficulty in making more definitive conclusions about the treatment of older youth in the CWS system comes from limitations in the available data. For example, while we know that older youth have lower maltreatment substantiation rates, we do not know the specific reasons why their reports are evaluated out or the details of in‑person investigations. We do note that DSS provided us some limited data on SDM overrides and rates of entry to foster care for youth in homeless families after this report was finalized. Unfortunately, this data does not align with the other data we used in this report. It does, however, indicate that DSS does have the ability to track this type of information.

Recommendations for Additional Data Gathering

Given the aforementioned uncertainties over whether older youth face systemic differences in accessing foster care, we recommend that DSS collect additional information—which we understand is currently not collected on a statewide, systematic basis—to be reported to the Legislature to better inform the reasons for any differences between older and younger youth with reports for maltreatment. Such data would also help determine whether policy interventions would be an appropriate remedy for those differences. Below we list some suggestions for additional data collection:

- Systematically Track the Reason a Maltreatment Report Is Evaluated Out. This type of data would be particularly useful for developing a better understanding of why older youth and youth in homeless families have higher rates of reports evaluated out.

- More Precisely Track Homeless Youth. Current data on homelessness is limited. Current available report data does not indicate whether a child is homeless despite the family having a home. This is important data for understanding whether homelessness impacts access to foster care for both age groups.

- Track Reports for Other Social Services After an Investigation Is Completed or After Deciding Not to Place a Child in Foster Care. Even if a report is evaluated out or a child does not enter foster care, counties may still refer a family for other social services. Better knowledge about how often such referrals are made and for what services, could add more context to outcomes in which youth do not enter foster care.

- Collect Data on Dependency Petitions by Welfare and Institutions Code. This was a data point requested in the supplemental report language that was not available. Data on self‑petitions for court dependency using WIC 329 and 331—as well as the outcomes of those petitions—would provide a better understanding of whether older youth experience relative challenges gaining access to foster care, even if their rate of entry into foster care following a substantiation of maltreatment is equivalent to younger youth.

- Record Whether Reports Involve Youth Self‑Reporting Maltreatment. This was another data point requested in the SRL that was not available. Such data might provide insight into whether older and younger youth are treated differently when they themselves report maltreatment rather than when it is reported by others.

- Monitor Outcomes for Youth With Prior Reports. This data was requested in the SRL, but was not available. Data on the outcomes of prior reports, as well as the most recent report, for youth with a history of multiple reports might help determine whether certain youth have had more difficulty gaining access to foster care over time.

With the state in the process of implementing a new information technology system for CWS, stakeholders will want to consider which types of recommended data collection can be implemented more immediately in the current system and which can be incorporated over a longer time period in the new system as it is being developed. Given that there would likely be county workload and technical challenges associated with new requirements for data collection, the Legislature might also want to request input from the administration and counties on the short‑ and long‑term feasibility of collecting certain types of data. Potential increased costs to the state and counties to collect additional data are among the feasibility considerations the Legislature will want to consider, as well as various options for limiting those costs—such as pilot programs involving a limited number of counties to refine processes before creating statewide reporting requirements.