LAO Contacts

See Related

2019-20 Budget Reports

March 26, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Undoing California’s

Outstanding Budgetary Deferrals

Introduction

When facing budget problems in the past, the state has “deferred” payments from one fiscal year into the next. (The state’s fiscal year runs from July 1st to June 30th, so these deferrals usually involve pushing payments from June into July.) Deferrals can provide significant budgetary savings immediately, helping the state balance the budget. (Budgetary deferrals are different than cash deferrals, in which the state makes payments late by weeks or months within the same fiscal year for cash flow purposes.) Budgetary deferrals result in an obligation that the state can eventually repay. While the state has already addressed many of its outstanding deferrals, there are still three major categories of deferrals remaining. The Governor proposes undoing some, but not all, of these outstanding deferrals.

In February, our office released a report looking at the overall structure of the Governor’s budget proposal, including a roughly $11 billion package to repay state debts and liabilities. That report—The 2019‑20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities—recommended rejecting the Governor’s proposal to undo two budgetary deferrals. This post provides more detail on that recommendation. In particular, we provide an overview of the state’s outstanding budgetary deferrals, assess the Governor’s proposal to undo some of them, and offer an alternative approach.

California’s Outstanding Budgetary Deferrals

The state has already undone billions of dollars in outstanding budgetary deferrals, most notably, those involving payments to schools and community colleges. However, California still has three categories of outstanding deferrals related to: (1) state employee payroll, (2) pension payments, and (3) Medi-Cal payments. These deferrals are described in greater detail in this section.

Payroll Deferral. The state pays its employees monthly. The 2009‑10 budget package included an ongoing one-month deferral of state payroll from June to early July, providing savings for the state. This action was only reflected in the state’s accounting reports—it did not affect when paychecks were actually issued to state employees. On an ongoing basis, the state’s budget documents still reflect 12 months of payroll, but rather than reflecting payroll for June of the last month of the fiscal year, they reflect June of the previous fiscal year. (For budgetary purposes, the state only recognized the deferral in the General Fund, not other funds’ statements.)

Pension Deferral. The state makes quarterly payments to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) for pension contributions for state employees. The state pays the fourth-quarter contribution to CalPERS in the first quarter of the subsequent fiscal year. (Our office has not been able to discover the year this deferral was first done.) This means the state makes the transfer in the first few days of July. This deferral only applies to the state’s General Fund pension payments—other funds’ fourth-quarter CalPERS payments are paid in June. For cash purposes, the state also defers other payments to CalPERS throughout the fiscal year. For example, a portion of the third-quarter payment is transferred in mid-April, rather than the end of March.

Medi-Cal Deferrals. Medi-Cal is the state’s largest health care program and provides health coverage to over 13 million low-income Californians. The state has had budgetary deferrals in Medi-Cal since 2003‑04 as described below:

Accrual to Cash Budget. In 2003‑04, the Medi-Cal budget transitioned from an accrual basis, in which funds are appropriated based on when health care services are rendered, to a cash basis, in which funds are appropriated based on when the bill for such services is actually paid. Since the bill for some health care services is paid after the fiscal year ends, this action shifts some costs into the subsequent fiscal year. We are not aware of any other state programs that are funded on a cash basis. The cash basis of the Medi-Cal budget made it possible for the state to implement two additional budgetary deferrals in later years, described below.

Fee-for-Service (FFS) Deferrals. Payments for health care services in Medi-Cal are made under one of two major delivery systems—FFS and managed care. In FFS, the state makes weekly payments directly to health care providers, such as physicians or hospitals. The state has two FFS-related deferrals still outstanding. First, in 2004‑05, the state delayed what otherwise would have been the final weekly FFS payment in June into July (the next fiscal year). (In 2004‑05, the state also delayed all weekly FFS payments by one week to allow more time for fraud prevention review. While this delay did result in one-time savings, we do not consider it among outstanding Medi-Cal deferrals because it was not intended entirely as a budget solution.) Second, in 2012‑13, the state delayed an additional FFS payment—the second-to-last payment in June—into July. Because of Medi-Cal’s cash budget, these timing shifts reduced the number of weekly FFS payments budgeted in the years the shifts took place and resulted in one-time savings.

Managed Care Deferrals. In the managed care delivery system, the state makes monthly payments to health insurers, known as “managed care plans,” that contract with health care providers on behalf of the state. Over 80 percent of Medi-Cal beneficiaries are served through managed care. In 2012‑13, the state began delaying the monthly managed care payment for June into July. Because of Medi-Cal’s cash budget, this created one-time General Fund savings.

Implications of the Deferrals

Deferrals Provide Savings Initially, but Carry Costs to Undo. In the first year a deferral is made, it results in significant savings for the state because the state only pays the partial cost of a year’s expense. For example, in the case of the payroll deferral, the state only reflected 11 months of payroll in the 2009‑10 budget, providing hundreds of millions of dollars in budgetary savings. Undoing this deferral, conversely, means the state must reflect an additional month of payroll—13 months—in a budget, carrying an additional cost. Each of the other deferrals work similarly. Figure 1 summarizes the General Fund cost to undo each of the state’s outstanding deferrals individually in this budget. In addition to these General Fund costs, undoing the Medi-Cal deferrals could have implications for other funds. For example, accelerating the timing of payments in Medi-Cal would also involve a one-time increase in federal funds spending to reflect the federal government’s share of the payments.

Figure 1

Summary of General Fund Cost to

Undo California’s Remaining Deferrals

(In Millions)

|

Cost to Undo |

|

|

Payroll deferral |

$707 |

|

Pension deferral |

973 |

|

Medi‑Cal deferrals |

|

|

Accrual to cash budget |

2,600a |

|

FFS deferrals |

300 |

|

Managed care deferral |

1,280 |

|

aRepresents the upper bound of a range. Includes the cost of undoing fee‑for‑service (FFS) and managed care deferrals. |

|

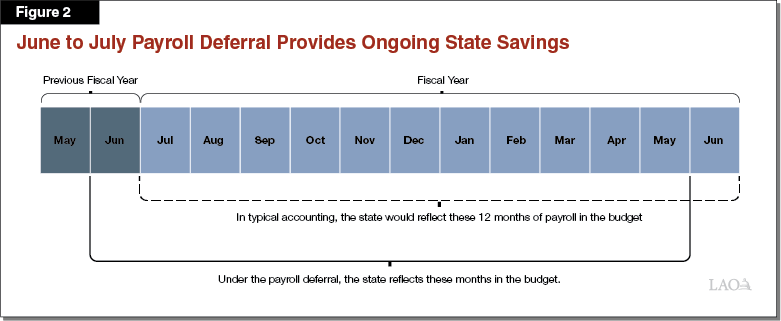

Deferrals Generally Provide Some Ongoing State Savings. All of the deferrals described here provide ongoing savings for the state General Fund. In the case of the payroll deferral, for any given fiscal year, the state pays the previous fiscal year’s June payroll, which would tend to carry somewhat lower costs than the upcoming June’s payroll (see Figure 2). In this case, the annual associated General Fund benefit of the deferral is projected to be around $30 million over the next few years. All of the state’s other deferrals also carry these ongoing savings, but the amount of savings varies depending on how the respective program’s costs are growing.

Three Potential Major Reasons to Undo Deferrals. We are not aware of any legal reason that would compel the state to undo any of its outstanding deferrals, either now or in the future. However, there are some policy reasons to do so. In particular, undoing any of the deferrals could have one or more of the following benefits:

Improve the State’s Fiscal Position. One reason to undo the deferrals would be to give the state the option to do them again in the future. This is like depositing money into a reserve—the state incurs a cost today to have the option to realize a reduction in costs in the future.

Improve the State’s Fiscal Transparency and Budgeting Practices. Ideally, the state’s budgetary costs would be reflected consistent with accepted public finance and accounting standards. To varying extents, each of the state’s budgetary deferrals result in inconsistencies between the state’s budgetary documents and standard accounting practices. As such, undoing them can improve the state’s fiscal transparency and budgetary practices.

Reduce Adverse Effects on Other Entities. When deferrals result in a real delay of payment from the state to other entities, they can result in adverse effects on those other entities. Some deferrals do not have such an effect because they are only reflected in the state’s accounting documents and are not true payment deferrals.

Governor’s Proposal and Assessment

Governor Proposes Undoing Two Deferrals. In his 2019‑20 proposed budget, the Governor proposes using $1.7 billion to undo two of the state’s three major categories of deferrals: the payroll deferral and the pension deferral. The administration estimates the cost to undo the payroll deferral would be $973 million (General Fund) and the cost to undo the pension deferral is $707 million (General Fund). The Governor has not proposed undoing any of the deferrals related to Medi-Cal.

Implications of the Governor’s Proposal. Using the criteria described above, we examine the potential implications of the Governor’s proposal. In particular, the Governor’s proposal to end the payroll and pension deferrals:

Improves the State’s Fiscal Position. The Governor’s proposal to undo the payroll and pension deferrals would allow the state to take these actions again in the future (essentially, carrying a reserve-like benefit). While the cost to undo these actions is $1.7 billion, the benefit of deferring these payments again in the future would likely be somewhat higher than $1.7 billion, assuming employee compensation and pension costs continue to grow. (The benefit of this action could, theoretically, be lower in the future if these costs declined.)

Moderately Improves the State’s Fiscal Transparency and Budgetary Practices. Undoing the pension and payroll deferrals could moderately improve the state’s fiscal transparency and budgetary practices. In particular, the payroll deferral results in an inconsistency between the state’s fund condition statements (published on a budgetary basis) and the state’s official accounting reports (published consistent with generally accepted accounting principles). Undoing the payroll deferral would reconcile the these reports. The administration has recently indicated that improving the state’s budgetary practice is its current rationale for proposing to undo these deferrals.

Does Not Reduce Adverse Effects on Other Entities. Neither the payroll nor the pension deferral carries notable adverse consequences for any nonstate entities. The payroll deferral does not affect when state employees receive their paychecks. Our conversations with representatives from CalPERS has indicated that the pension system does not experience adverse consequences from receiving funds in early July rather than late June. (In fact, as described earlier, for cash purposes, the state has longer deferrals in place for other payments to CalPERS within the fiscal year.)

Alternatives to the Governor’s Proposal

In this section, we discuss three alternatives to the Governor’s proposal. In particular, the Legislature could consider: (1) building more reserves (with the primary goal of improving the state’s fiscal position), (2) moving Medi-Cal back to an accrual budget (with the primary goal of addressing fiscal transparency), and (3) undoing some or all of the later Medi-Cal deferrals (with the primary goal of reducing adverse consequences for other entities). This section analyzes these alternatives.

Build More Reserves

The first reason to undo deferrals is fiscal—that is, undoing the deferrals would allow the state to take this action again in the future, resulting in a benefit similar to reserves. If this is the Legislature’s primary goal for undoing the deferrals, we suggest the Legislature consider building more reserves directly instead. Consistent with our discussion in the report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities, this section presents reasons why building more reserves would result in more fiscal benefit to the state as well as less administrative complexity.

Undoing the Deferrals Eliminates Ongoing State Savings. As we discussed earlier, because costs grow over time, all of the deferrals described above provide ongoing savings for the state General Fund. As such, undoing the deferrals eliminates these state savings. For example, the Department of Finance estimates the state will reflect, on average, about $35 million per year in savings over the next five years as a result of the pension deferral and $30 million per year over the next five years as a result of the payroll deferral. Although we do not have an estimate of the annual savings associated with the various Medi-Cal deferrals, undoing any of these deferrals would similarly eliminate their associated annual benefit.

Depositing Money Into Reserves Generates Interest Payments. Money held in the state’s cash reserves is not idle. The State Treasurer’s Office (STO) invests state funds, including reserves, in the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA), generating an investment return. STO invests these funds in safe, short-term assets, like U.S. Treasuries, and so the investment return is low—currently slightly above 2 percent. These investment returns generate revenue for the General Fund. At the PMIA’s current rate of return, holding $1.7 billion in a state reserve (like the Budget Stabilization Account), rather than undoing deferrals, would result in $40 million in additional General Fund revenue per year. (That said, undoing the deferrals would slightly improve General Fund liquidity, contributing to some higher investment earnings, but this effect is difficult to quantify and very small.)

Undoing, and Redoing, Deferrals Involves More Administrative Complexity. Undoing deferrals and then taking the action again in the future results in significantly more administrative complexity than simply saving more money in reserves. The payroll deferral, in particular, has involved increased workload for the State Controller’s Office when the state took the action initially and in annual state accounting records. By contrast, depositing money into reserves is a common and administratively straightforward action for the various state departments to implement.

Move Medi-Cal Back to an Accrual Budget

The second reason to undo the deferrals is to improve transparency. If this is the Legislature’s primary goal for undoing the deferrals, then there might be reasons to consider moving Medi-Cal back to an accrual basis. This section considers the extent to which this alternative would improve the state’s fiscal transparency, particularly for facilitating the Legislature’s oversight over the Medi-Cal budget.

Cash Basis Creates Challenges for Legislative Oversight of Medi-Cal Budget. As we noted in our report The 2019‑20 Budget: Analysis of the Medi-Cal Budget, in recent years Medi-Cal expenditures have become increasingly difficult to project. Significant, unanticipated changes to the Medi-Cal budget have become routine. This is partly due to Medi-Cal’s cash basis of budgeting. Specifically, the timing of some payments in Medi-Cal are subject to considerable uncertainty. Shifts in the timing of large payments under a cash budget can lead to large unexpected changes in the Medi-Cal budget. As a result, year-to-year changes in estimated Medi-Cal spending can be driven more by the timing of payments than by the underlying drivers of program spending, such as caseload and the utilization and cost of health care services. This makes oversight of the Medi-Cal budget challenging for the Legislature, since the Legislature has limited insight into the causes of such timing shifts and limited ability to anticipate them.

Reverting to Accrual Basis for Budgeting Would Have Benefits, but Would Have Significant Administrative Challenges . . . The Legislature could consider transitioning Medi-Cal back to an accrual budget as a way to increase legislative oversight and improve the predictability of the Medi-Cal budget. Doing so would match budgeted costs to when services are delivered, more closely align Medi-Cal’s budget with the trends in underlying program dynamics, smooth year-to-year changes in the Medi-Cal budget, and could make the budget more predictable. That said, switching Medi-Cal back to an accrual basis of budgeting would be a complex endeavor. The Medi-Cal program has grown significantly in size and complexity since the switch to cash budgeting in 2003‑04. As a result, moving an accrual budget would increase workload, because the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) would likely need to continue tracking certain elements on a cash basis for cash management and other operational needs.

. . . And Warrants Further Study. Given the potential benefits of reverting Medi-Cal to an accrual budget, we believe directing DHCS to examine how to implement this change is warranted. In our recent Medi-Cal report referenced above, we recommended that the Legislature require DHCS to report to the Legislature with a plan for longer-term changes—such as returning Medi-Cal to an accrual budget—to promote sound Medi-Cal estimates and budget transparency.

Undo Medi-Cal FFS and Managed Care Deferrals

The third reason to undo deferrals is to reduce adverse consequences for other entities. If this is the Legislature’s primary goal, then it might want to consider undoing Medi-Cal FFS and managed care deferrals. As we describe in this section, unlike the deferrals that the Governor proposes undoing, some of the Medi-Cal deferrals have tangible consequences for other entities that receive payments from the state.

Medi-Cal Deferrals, in Particular FFS Deferrals, Have Adverse Consequences for Some Entities. Deferred payments in Medi-Cal mean that managed care plans and some health care providers face a gap in Medi-Cal payments at the end of the state fiscal year. These entities must arrange their finances to cover this gap. To a significant extent, managed care plans and many medical providers appear to have adapted to payment deferrals with limited difficulty. There are some FFS providers, however, for whom deferrals may have a greater impact. Entities that are most likely to be negatively impacted by the deferred payments are those that:

Are relatively small and have fewer total resources available to cover gaps in Medi-Cal payments.

Receive a high percentage of their total revenue from Medi-Cal.

Receive most of their Medi-Cal payments through the FFS system. (Managed care plans typically pay health care providers on time for services rendered to Medi-Cal beneficiaries even when the state delays payments to the managed care plan, so health care providers that participate in Medi-Cal through a managed care plan generally are not affected by payment deferrals.)

Some examples of entities that may be particularly affected by the Medi-Cal payment deferrals include rural hospitals that have a high percentage of their patient base that is covered by Medi-Cal or insured and providers of family planning services (such as Planned Parenthood), a large share of which are paid for through the FFS system.

Technical Challenges Make Undoing Managed Care Deferral Difficult. Managed care payments have grown increasingly complex in recent years. Since the 2012‑13 action to defer the June managed care payment into July was taken, other monthly payments within the fiscal year have been delayed for various reasons. In the context of these changes, which are partially outside the state’s control, undoing the managed care deferral would be very difficult.

Recommended Approach

Our earlier report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities, recommended that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to undo the payroll and pension deferrals because they provide ongoing budgetary savings and would involve administrative effort to take this actions again in the future. In this section, we present an alternative to the Governor’s proposal. We suggest the Legislature instead use the $1.7 billion to selectively reverse the FFS Medi-Cal deferrals and use the remaining funds to build more reserves. This section describes that recommendation and its advantages.

Selectively Reverse Medi-Cal Deferrals. We recommend the Legislature reverse the FFS Medi-Cal deferrals. This action has a one-time cost of $300 million and would eliminate the gap in payment for the health care providers who cannot as easily accommodate the delay. Given that the managed care deferrals do not appear to negatively impact those providers and undoing this deferral involves significant technical challenges, we do not recommend reversing this deferral.

Completely ending Medi-Cal deferrals would involve transitioning Medi-Cal back to an accrual basis. This action is not ideal at this time for a few reasons. First, the estimated one-time cost of this action is significant—as much as $2.6 billion in 2019‑20—as payments that are currently beyond the 2019‑20 budget window on a cash basis would be accelerated into 2019‑20. Second, there likely are significant administrative implications that warrant further understanding before taking action. Third, this action has limited value in terms of improving the state’s fiscal position, since moving Medi-Cal back to a cash basis to achieve savings again in the future would be very difficult.

Use Remaining Funds to Build More Reserves. The Governor’s proposal to undo the payroll and CalPERS deferrals would cost $1.7 billion in 2018‑19. If the Legislature rejected the Governor’s proposal to undo these deferrals and used $300 million to undo the FFS Medi-Cal deferrals, there would be an additional $1.4 billion remaining. We recommend the Legislature then use these funds to build more reserves.

Our Alternative Approach Has Several Advantages. Relative to the Governor’s approach, our recommended alternative would have a number of benefits. Figure 3 summarizes the fiscal differences between these approaches. Relative to the Governor’s approach, our alternative would:

Reduce adverse consequences to some Medi-Cal providers that are more likely to be negatively affected by the deferrals, like rural hospitals and providers of family planning services.

Maintain the state’s ongoing budgetary savings from the payroll and pension deferrals, which together are projected to average $65 million per year over the next five years.

Build more reserves by $1.4 billion, resulting in higher annual investment returns for the General Fund and less administrative complexity to implement.

Figure 3

Comparing LAO and Governor’s Alternatives

(In Millions)

|

Cost to |

Annual General |

|

|

Governor’s Approach |

||

|

Undo payroll deferral |

$707 |

‑$30 |

|

Undo pension deferral |

973 |

‑35 |

|

Totals |

$1,680 |

‑$65 |

|

LAO Alternative Approach |

||

|

Undo Medi‑Cal FFS deferrals |

$300 |

— b |

|

Use remaining funds to build more reserves |

1,380 |

$39 |

|

Totals |

$1,680 |

$39 |

|

aReflects an average of five‑year projected savings. bAnnual General Fund benefit is unknown. FFS = fee‑for‑service. |

||