LAO Contact

March 26, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of Proposed Increase in State Funding for Local Child Support Agencies

Executive Summary

Legislature Directed the Department of Child Support Services (DCSS) to Identify Operational Efficiencies and Refinements to Budget Methodology by July 1, 2019. During the 2018‑19 budget deliberations, funding for the 49 local child support agencies (LCSAs) became an issue of concern for the Legislature. Specifically, current state funding levels for LCSAs are not based on any particular rationale and likely hinder the state’s goal of ensuring consistent child support services across the state. The 2018‑19 budget included an ongoing General Fund augmentation of $3 million (an increase of about 1 percent) to be shared among some LCSAs. The state provided this funding to address a concern that flat funding levels over time have made it difficult for some LCSAs to carry out core child support services. Looking ahead, the budget also required DCSS to produce a report that identifies program‑wide operational efficiencies and refinements to the methodology that is used to provide funding to the LCSAs. That report is expected to be completed by July 1, 2019.

Governor’s Proposal. Longstanding differences in funding across LCSAs raise the concern that some LCSAs may not have sufficient resources to perform core child support tasks, while others may have more than enough funding. In light of this concern, as part of the 2019‑20 budget proposal, the Governor proposes a new budgeting methodology that would incrementally increase General Fund support for LCSAs identified by the proposal as “underfunded.” Specifically, the proposed budgeting methodology calculates new baseline program costs for each LCSA and compares these costs to their current funding levels. Based on this comparison, the administration identified 21 LCSAs with funding levels below the calculated baseline costs. Over three years, the Governor proposes to increase total funding for these LCSAs by $57 million General Fund (the amount that is needed to increase funding in each of the 21 LCSAs from current levels to the level calculated as their baseline cost under the new methodology), while maintaining funding levels for LCSAs above the calculated baseline costs. The proposal also includes performance‑based funding for LCSAs that demonstrate increased collections and collections per case that will be distributed following the allocation of the initial $57 million (in 2022‑23). Overall, the administration estimates that total collections will eventually increase by $347 million (15 percent) as a result of increasing state funding levels.

Governor’s Proposal Premature and Raises Significant Policy Questions and Concerns. In our assessment, the administration’s proposal is premature in several ways and raises significant policy questions and concerns:

- Proposed New Budget Methodology Premature at This Time. The Legislature directed DCSS and the LCSAs to identify operational efficiencies that would make the state’s child support program more cost‑effective and efficient. The department has not yet identified these opportunities or built them into its proposed budgeting methodology. In our view, it is premature to request additional state funds without fulfilling the Legislature’s directive to also identify cost‑savings measures. In addition, the federal government recently issued new policy guidance on child support program operations. Updating state practices in the next few years to comply with this guidance could result in changes to LCSA operations and funding needs. As such, it is premature to institute a new budgeting methodology prior to updating state law to align with the new federal guidance.

- Governor’s Proposal Raises Significant Policy Questions and Concerns. The administration has not proposed statutory language to codify the intent of the budget proposal or outline how the budgeting methodology will be used in future years. As a result, legislative oversight and accountability related to the use and impact of proposed new state funding are limited. Lastly, the proposal does not fully consider the possibility of, and trade‑offs associated with, reducing the proposed state funding augmentation needed to meet baseline program costs in some LCSAs by first “right‑sizing” funding levels for all LCSAs. Right‑sizing funding for all LCSAs would mean redirecting excess funding from 28 LCSAs with more than enough funding to meet baseline costs to the remaining 21 LCSAs identified as not having enough funds to meet calculated baseline costs.

LAO Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the current proposal until the administration submits (1) the statutorily required report identifying state and local operational efficiencies and (2) a proposal to refine the current budget methodology based on the finding of the report, as previously directed by the Legislature. Regarding the development of a totally new, wide‑ranging budget methodology, as opposed to refinements, we suggest that the Legislature wait until after the state has updated its program to align with federal guidance before instituting a new methodology. Finally, given that the funding for LCSAs has remained flat for many years, if the Legislature wishes to consider providing some funding to counties to provide some fiscal relief while the state updates its program, one option would be for it to provide an inflation adjustment for all LCSAs in 2019‑20.

Introduction

The primary purpose of the state’s child support program is to collect child support payments from noncustodial parents and distribute those payments to custodial parents and their children. At the county level, Local Child Support Agencies (LCSAs), overseen by the state Department of Child Support Services (DCSS), collect and distribute child support payments. In order to collect and distribute child support payments, LCSAs locate noncustodial parents, certify paternity, establish child support orders, and enforce the payment of child support orders.

During the 2018‑19 budget deliberations, LCSA funding became an issue of concern for the Legislature. As a result, the 2018‑19 Budget Act provided certain LCSAs with a small budget augmentation. Looking ahead, the budget also required DCSS to produce a report that identifies program‑wide operational efficiencies and refinements to the methodology that is used to provide funding to the LCSAs. That report is expected to be completed by July 1, 2019.

In this report, we provide background on the current child support program. We then describe and assess the Governor’s 2019‑20 proposal to create a new budgeting methodology that would increase funding for certain LCSAs by nearly $60 million General Fund. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the funding proposal until the administration submits the statutorily required report identifying potential state and local operational efficiencies.

Background

What Is Child Support? Under state law, parents share an equal financial responsibility for the support of their children. Generally, when parents do not live together, such as divorced or never‑married parents, one parent often assumes primary custodial responsibilities to care for the child. In these cases, the noncustodial parent—that is, the parent who does not have primary custody of the child—makes monthly child support payments to the custodial parent. The amount of child support that a noncustodial parent is obligated to provide is known as the child support order.

Child Support Orders Can Be Established Privately or Through the State’s Program. In general, individuals can establish a legally binding child support order in one of two ways. First, a child support order can be established privately through a private attorney or as a result of divorce proceedings. Secondly, the government can establish child support orders through the state’s child support program (although final authority for setting the amount of the child support order rests with the court system).

State Child Support Program Collects Child Support From Noncustodial Parents. The primary purpose of California’s child support program is to (1) establish child support orders, (2) collect child support payments from noncustodial parents, and (3) distribute collected child support to custodial parents and their children. Currently, 49 LCSAs carry out these tasks at the local level. These tasks include locating absent parents; certifying paternity; establishing, enforcing, and modifying child support orders; and collecting and distributing payments. (We discuss these steps in more detail later in this section.) In federal fiscal year (FFY) 2017‑18, the state’s child support program collected and distributed about $2.4 billion on behalf of 1.2 million child support cases.

Federal Government Requires States to Collect Child Support on Behalf of CalWORKs Parents. Federal law requires states to collect child support for all custodial parents who receive cash grants under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program—known in California as the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program. CalWORKs provides cash assistance, job training, and social services to very low‑income families with children. The vast majority of CalWORKs families have little or no income, and most CalWORKs families are headed by a single parent. Under federal law, states must also offer the same child support services to other families, or “non‑CalWORKs” families, but only if they request the services.

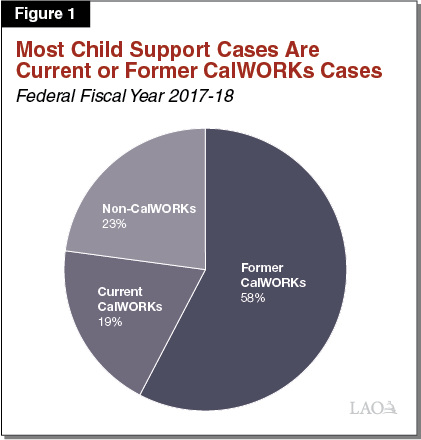

More Than Three‑Quarters of Child Support Cases Are Current or Former CalWORKs Cases. Figure 1 displays all cases within the state’s child support program by case type: current CalWORKs, former CalWORKs, and non‑CalWORKs. As a result of the requirement that CalWORKs families enroll in the child support program and the option that other families enroll, more than three‑quarters of child support cases are current or former CalWORKs recipients. (Privately established child support orders are not included. These orders would only become state cases if the custodial parent requests services to enforce and collect the order.)

Child Support Collected for CalWORKs Parents Is Used to Offset Cost of CalWORKs Benefits. When a custodial parent applies for CalWORKs, federal law requires them to sign over the majority of their child support payments to the state. These payments—often referred to as recoupment dollars—are distributed to the state and federal governments (counties also receive a small portion) to reimburse some of their costs associated with CalWORKs benefits. However, not all of these child support payments go to the government—federal law allows states to “pass through” up to the first $100 in child support per month to the custodial parent. In California, CalWORKs families keep the first $50 in monthly child support collected on their behalf, while the remainder is distributed to the state, county, and federal governments. In 2017‑18, the state collected $410 million in child support on behalf of former and current CalWORKs families. Of this amount, $368 million was collected as CalWORKs recoupment that was used to reimburse the state ($168 million), counties ($23 million), and federal ($176 million) governments. In most cases, counties use their recoupment dollars for general county purposes and not specifically to augment funding for their LCSA. Of the remaining amount, $12 million was passed through to CalWORKs families.

Child Support Services Are Funded Primarily by the State and Federal Government. The federal government pays two‑thirds of the costs of child support services and the state pays the remaining one‑third. There is no cap on the amount of federal funds the state can draw down with regards to the child support program. LCSAs primarily rely on the state General Fund to draw down federal funds. While the state does not require counties to have a share of cost in administering the program, counties may voluntarily provide local funds to draw down additional federal funds. (A few counties provide some county general fund dollars to their LCSA.) Total funding for the state child support program is estimated to be $1 billion in 2018‑19. The majority of these funds—about $770 million—are allocated to LCSAs to administer child support services.

Cost Pressures Primarily Driven by Caseload and Local Factors. Costs to administer child support services depend primarily on the number of child support cases each LCSA has, locally negotiated salaries and benefits for employees, local costs of doing business, and how LCSAs choose to structure their operations. Again, though many local decisions influence LCSA cost pressures, counties have no mandatory share of costs under the current financing structure.

The Structure of California’s Child Support Program

As noted above, the federal government requires states to provide child support services. In general, though, federal law allows states to operate their systems as they see fit. In the following section, we outline how California’s child support program is structured, including the major roles and responsibilities for the state, the LCSAs, and the courts (where child support orders are ultimately established and modified).

State Restructured Child Support System in 1999. Prior to 1999, the child support program was administered at the local level by county district attorneys (DAs), with state oversight by the Department of Social Services (DSS). In an effort to improve program performance and increase the consistency of child support enforcement across the state, the Legislature passed a reform package of bills in 1999 that aimed to restructure the organization, administration, and funding of the program. First, the oversight of child support enforcement was transferred from DSS to a new stand‑alone department, DCSS. Second, child support operations in each county were transferred from the county DA’s office to newly created LCSAs. With these changes, the state intended to shift control of the child support program away from locally elected law enforcement officials (the DA) and toward a state‑appointed child support administrator (the Director of DCSS). The reforms gave DCSS a greater oversight role than had been carried out by DSS, in part, to ensure that child support services were provided consistently across counties. (At the time, there was wide variation in how counties established and enforced child support orders.) To address this issue, the new state department was tasked with identifying and encouraging consistent best practices across the counties.

State Reforms Brought Some Funding Changes, but Preexisting County Variation Continued. Additionally, the 1999 reforms intended to make several changes to the budgeting practices of the child support program. Prior to 1999, local child support budgets were neither reviewed nor approved by the state, meaning counties were solely responsible for determining how much money to spend on their child support programs. This local funding was then matched with federal funds and state and federal incentive funding. Under the reforms, DCSS assumed responsibility for determining program expenditure levels and allocating state funds among local agencies. With the reforms, the state also intended to develop a new budgeting methodology to be used to fund the newly established LCSAs. At the time, the amount of funding dedicated to child support enforcement varied significantly across the counties and was not based on the amount of funds needed to meet state program priorities. Instead, county funding levels depended on how much each county DA dedicated to the program. However, while attempts were made to allocate state funds differently once the program was overseen by DCSS, the state ultimately chose to allocate funds to LCSAs largely based on the funding level in each county prior to 1999—which was the same as the amount the local DAs had been spending. Since that time, the state has provided very limited budget augmentations—one in 2009‑10 (specifically, $6.4 million General Fund to maintain caseworkers) and one in 2018‑19 (specifically, $3 million General Fund for a subset of LCSAs with lower staffing levels).

State DCSS’ Roles and Responsibilities. Below, we describe DCSS’ major oversight and leadership responsibilities.

- Program Oversight. DCSS oversees local child support operations by performing such activities as monitoring and auditing LCSA spending, issuing policy guidance about how to implement new state or federal laws that affect child support, and collecting performance data from the LCSAs and submitting the results to the federal government. Additionally, the 1999 child support reforms require DCSS to encourage efficient operations in an effort to maximize performance, including cost‑effectiveness. Cost‑effectiveness is measured as average collections for each dollar spent to operate child support services.

- Policy Leadership and Technical Assistance. The state is expected to set a policy vision for the child support program. To meet this expectation, DCSS prepares a strategic plan every five years in which it identifies new priorities and proposes policy changes to further those priorities. The plan, for example, identifies key performance priorities. One key priority is to increase cost‑effectiveness from its current level—$2.50 collected for each $1 spent—to $3.00. In addition to identifying major priorities and highlighting strategies to achieve those priorities, the state is expected to provide individualized technical assistance to LCSAs.

- StatewideInformation Technology (IT) Database Management. Federal law requires that the state operate a single child support IT system. Each LCSA has access to the statewide child support enforcement IT system, known as the Child Support Enforcement system, through which LCSA staff manage their child support caseload, track payments and overdue child support, and initiate enforcement actions when needed. DCSS maintains the system’s functionality and ensures that LCSAs have uninterrupted access to their caseload management and enforcement tools. The state also maintains the statewide disbursement unit, through which child support payments collected by LCSAs are sent to noncustodial parents or recouped by the state, as occurs when child support is collected on behalf of CalWORKs parents.

- Some Statewide Child Support Enforcement Activities. Although most enforcement functions are performed at the local level, as discussed below, the state nevertheless carries out some key enforcement activities in conjunction with LCSAs. For instance, DCSS operates the automated system that collects child support payments via automatic payroll deductions (known as income withholding orders). Additionally, on behalf of all LCSAs, DCSS recently instituted a statewide system of payment kiosks, at which noncustodial parents may make child support payments.

LCSA’s Roles and Responsibilities. Although the state oversees and manages the statewide IT system, most child support activities are carried out at the local level. The main steps that LCSAs and local courts perform are the following: (1) locate noncustodial parents, (2) certify paternity, (3) establish and modify child support orders, and (4) collect payments (either through voluntary payments or various enforcement actions). Below, we provide a brief explanation of the role LCSAs play in some of these key steps in establishing and enforcing a child support order.

- Calculate Preliminary Child Support Order. When child support begins, LCSAs calculate a proposed amount of child support and send it to the noncustodial parent for review. At this time, the noncustodial parent may provide additional information to be used when the LCSA calculates the proposed child support obligation. This calculation of the order is based on statutorily established state guidelines that dictate the factors to include in the determination of the child support order. These factors include such things as wages, the amount of time the child spends with each parent, disability benefits, and the costs of raising other children in the household.

- Establish Final Order in Court. LCSAs present the proposed amount of the child support order to a child support judge, or court commissioner, for approval. Here, parents have the opportunity to provide the court commissioner with additional information that may not have been included in the LCSA’s guideline calculation. In establishing the final order, court commissioners may deviate from the proposed amount and issue a different child support amount. Additionally, a child support order could be set at zero, referred to as a “zero‑order”, if the noncustodial parent has little income, or no ability to earn income, such as in cases where the parent is incarcerated, involuntarily institutionalized, or disabled.

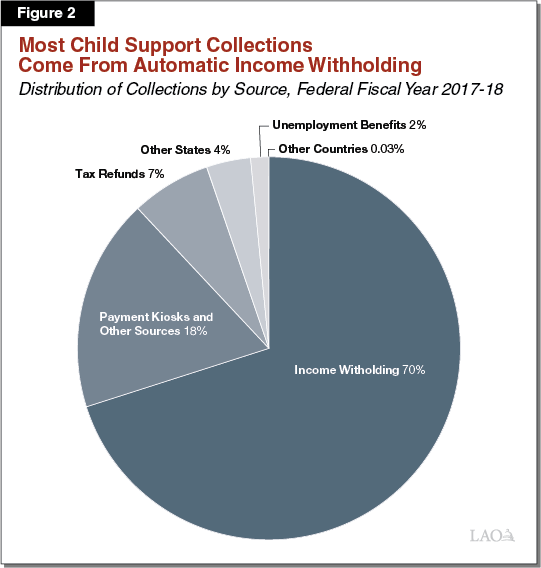

- Collecting and Enforcing Child Support Orders. Once a child support order has been established, LCSAs collect payments on behalf of the custodial parent. As shown in Figure 2, most collections are automatically collected through income withholdings that are deducted from payroll. If the noncustodial parent does not pay or pays less than the amount ordered, LCSAs seek past due payments—known as arrears—through enforcement actions, such as bank levies or driver’s license suspension.

Some LCSAs Have Capacity to Provide Services to Others. In addition to their normal functions, some LCSAs offer services to other LCSAs, referred to as “shared services”. For example, some LCSAs operate regional call centers that answer calls from customers in multiple counties throughout the state. Additionally, some LCSAs operate “centers of excellence” in which they take on uncommon and complex child support cases from other LCSAs. For example, an LCSA that has developed a particular expertise in collecting child support from workers’ compensation benefits may take on cases with workers’ compensation claims from other LCSAs. Usually these types of agreements are worked out between the LCSAs involved. In some cases, one LCSA may pay the other LCSA for services, and in other cases one LCSA may perform the services at no charge.

Local Courts and State Judicial Council Roles and Responsibilities. As mentioned, child support commissioners have the final authority to set the amount of the child support order. Although LCSA staff attempt to collect the relevant information to determine a proposed order amount, these amounts ultimately must be presented to, and approved by, a court commissioner. (Commissioners may approve the child support order as proposed by the LCSA or make changes to the proposed amount.) Commissioners specialize in hearing child support court cases, interpreting state and federal child support laws, and setting child support orders. At the local level, a court hearing overseen by a commissioner is required in order to (1) establish the child support order; (2) increase, decrease, or otherwise modify an existing order, such as increasing an order when the noncustodial parent obtains a higher‑paying job; and (3) close a child support case.

At the state level, the Judicial Council of California, the policymaking body of the state’s court system, receives funding from DCSS to oversee the county child support courts. In addition to this role, the Judicial Council reviews the statewide statutory formula for calculating child support payments—referred to as the guideline calculator—every four years to identify recommended revisions. In developing its recommendations, the Judicial Council is required to consult with DCSS and other stakeholders. (We note that legislative action would be needed to adopt any of the recommended revisions.)

Measuring Performance in Child Support

Federal Performance Measures. The federal government requires states to track and report performance data for five performance measures. They are: (1) paternity establishment, (2) percent of cases with a child support order, (3) percentage of total current child support that is paid, (4) percentage of total past due child support that is collected, and (5) cost‑effectiveness. Figure 3 describes each performance measure and compares how California ranks relative to other states. As shown in the figure, California performs at or above the national average for each performance measure except cost‑effectiveness, on which the state scores near the bottom. In addition to measuring statewide performance, the state also collects performance data for each LCSA. The federal government provides incentive funds to states based on their performance on the federal measures relative to other states. The state’s performance is dependent on how well LCSAs do on the federal performance measures.

Figure 3

Federal Performance Measures

Federal Fiscal Year 2017‑18

|

Measure |

Description |

Performance |

U.S. Average |

Overall Ranka |

|

Paternity Establishment Percentageb |

Measures the share of children born out‑of‑wedlock for whom paternity has been established. |

94% |

94% |

13 |

|

Percent of Cases With a Child Support Order |

Number of cases with a support order compared to total number of cases. |

91 |

87 |

12 |

|

Current Collections Performance |

The amount of current child support payments collected compared to the total amount of current child support owed. |

67 |

65 |

16 |

|

Arrearage Collections Performance |

The number of cases with collections on arrears compared to the total number of cases that owe arrearages. |

66 |

64 |

15 |

|

Cost‑Effectiveness Performance |

The ratio of total collections to total program costs. |

$2.52 |

$5.15 |

51 |

|

aRank out of 54 entities, including the 50 states plus Washington, D.C., Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. bStates may choose between two formulas to calculate the paternity establishment measurement. As such, California’s rank (13) is out of states that selected the same formula and not all states. |

||||

State Practice Indicators. In addition to the federal performance measures, as part of its most recent strategic plan, the state identified several additional performance measures. These measures, known as the state practice indicators, measure other LCSA outcomes that do not fall under the federal measurements. In general, the state practice indicators focus more on customer service—for example, by tracking the amount of time LCSAs take to establish an order and begin to collect child support—and payment reliability—for example, by measuring the share of custodial parents who receive at least 75 percent of the amount owed. Although DCSS implemented the state practice indicators, state funding for LCSAs does not depend on how well LCSAs perform on these indicators. Instead, the state and LCSAs use the indicators to evaluate their operations and practices in order to make improvements.

Recent and Upcoming Developments

State Increased Funding for LCSAs by $3 Million General Fund. The 2018‑19 budget included a $3 million ongoing General Fund augmentation (an increase of about 1 percent statewide) to be shared among some LCSAs. The state provided this funding to address a concern that flat funding levels over time have made it difficult for some LCSAs to carry out core child support services.

Legislature Directed DCSS to Identify Operational Efficiencies and Refinements to Budget Methodology by July 1, 2019. Budget‑related legislation approved as part of the 2018‑19 Budget Act required DCSS, in collaboration with the Child Support Directors Association of California, to “[identify] programwide operational efficiencies and further refinements to the budget methodology for the child support program, as needed.” In this context, budget methodology refers to the process by which the state determines what level of funding to allocate to LCSAs. The Legislature required the department to submit a report describing the identified operational efficiencies and recommended refinements to the budget methodology by July 1, 2019.

State to Implement New Federal Rules in the Next Few Years. In 2016, the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement, which oversees state child support programs, issued guidance to place a greater emphasis on establishing orders based on the noncustodial parent’s ability to pay, with the goal of establishing more reliable, consistently paid child support payments. Specifically, states must update their practices to ensure that each child support order is “based on the noncustodial parent’s earnings, income, and other evidence of ability to pay.” Figure 4 summarizes the new federal guidance. While the state is already in compliance with some components of the federal rule, updating state practices in the next few years to comply with the outstanding portions could result in major changes to LCSA operations and funding needs.

Figure 4

Recent Federal Guidance Prioritizes Ability to Pay and Reliability

Major Features of the Federal Final Rule, December 2016

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Overview of Federal Final Rule, “Flexibility, Efficiency, and Modernization in Child Support Enforcement Programs.” |

Governor’s Proposal

As part of the 2019‑20 budget, the Governor proposes a new budgeting methodology that would incrementally increase General Fund support for LCSAs by a total of $57.2 million on an ongoing basis. The augmentation would ramp up over three years and be provided to LCSAs identified by the proposal as not having enough funding to meet newly calculated baseline program costs. The administration’s estimate of baseline program costs for each LCSA is based on newly developed estimated costs for various program components, including staffing and associated overhead. The proposal also includes performance‑based funding for LCSAs that demonstrate increased collections and collections per case that will be distributed following the allocation of the initial $57.2 million (in 2022‑23). Below, we provide a high‑level explanation of the Governor’s funding proposal.

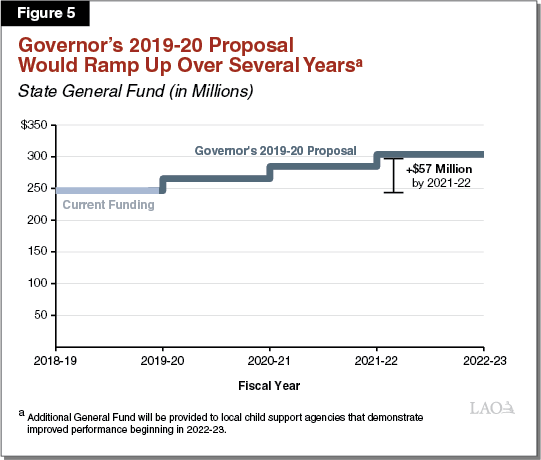

Incrementally Increases Total General Fund Support by $57.2 Million Ongoing. The state is expected to provide $246.5 million General Fund ($764.7 million total funds) to LCSAs in 2018‑19 to administer the child support program. The budget proposes a new budgeting methodology that would ultimately increase total General Fund by $57.2 million ($168.5 million total funds), or 23 percent. As shown in Figure 5, this funding would ramp up over the next three years. The amount of General Fund will increase by $19.1 million each year for the first three years, reaching a total increase of $57.2 million General Fund by 2021‑22. Beginning in 2022‑23, up to $5.1 million in additional General Fund ($15 million total funds) will be provided to certain LCSAs that have increased their child support collections.

Budgeting Methodology Calculates Baseline Program Costs. The administration’s proposal begins with the assertion that some LCSAs are “underfunded” compared to other LCSAs. To determine which LCSAs are underfunded, the administration created a new calculation of the baseline costs of the program. As shown in Figure 6, this baseline cost estimate takes into account three major factors—(1) target staffing levels, (2) associated overhead, and (3) call centers. Overall, total statewide baseline program costs for LCSAs are estimated to be $286 million General Fund ($842 million total funds) in 2019‑20. Below, we explain how the proposed budgeting methodology calculates costs for each major component of the baseline cost calculation.

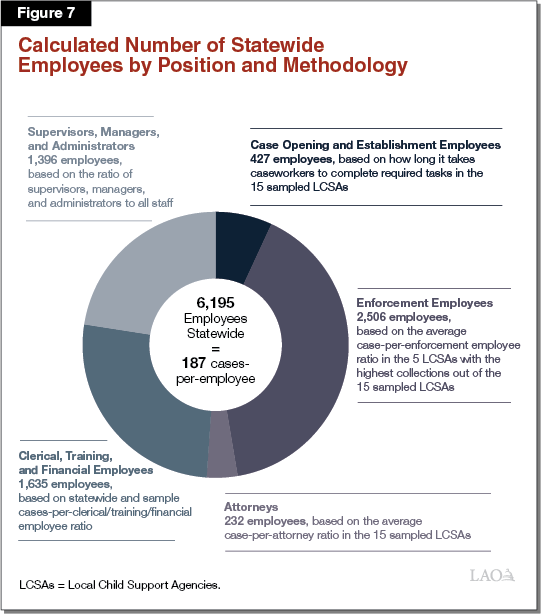

- Target Staffing Level Costs. One major component of the baseline program cost is the target staffing level. Under the proposed budgeting methodology, an LCSA should receive enough funding to maintain a staffing ratio of 187 child support cases to one full‑time equivalent (FTE) employee. The administration reached this ratio by dividing total caseload by the estimated number of FTE employees (hereafter referred to as employees) needed statewide to locally administer the child support program in 2019‑20. Figure 7 shows the total number of employees needed (6,195 FTE employees statewide) by position and the different methods used to calculate this number. For example, the administration determined the total number of employees needed for child support establishment by surveying 15 LCSAs (referred to as the “time study”) on how long it takes to complete required tasks when establishing an order. For the remaining positions, the administration did not conduct a time study. Instead, it generally based target staffing levels on current average staffing levels among the surveyed LCSAs. The budgeting methodology applies the target staffing ratio (187 cases‑per‑employee) to each LCSA’s caseload and estimated 2019‑20 local salary and benefit costs to determine staffing costs. Total staffing costs are calculated to be $226.4 million General Fund ($665.8 million total funds) in 2019‑20.

- Associated Overhead Costs. For purposes of the budgeting methodology, overhead includes rent, facility operation costs, direct service contract costs, and other indirect costs. (All salary and benefit costs are captured in the staffing cost estimate.) Overhead costs are calculated to total $49.4 million General Fund ($145.2 million total funds) statewide in 2019‑20. This is based on the average share of total administrative costs currently spent on overhead across all LCSAs.

- Call Center Costs. Currently, LCSAs either answer calls through their own call centers or direct these calls to call centers operated by other LCSAs. The proposed budgeting methodology creates a standard cost formula for all calls based on a standard call per employee ratio—6,030 calls a year to one employee—and a fixed cost per call—$15 per call. By developing a standard cost formula for calls, it is the administration’s intent to encourage LCSAs to elect the most cost‑effective way to manage their calls. That is, to the extent that the costs for an LCSA to manage its own calls exceeds the budgeted amount, the LCSA will either need to absorb those costs or direct their calls to another (more cost‑effective) call center. Call center costs are calculated to total $10.5 million General Fund ($30.7 million total funds) statewide in 2019‑20.

Figure 6

Calculated Baseline State Costs Per Governor’s Proposal

2019‑20, General Fund (In Millions)

|

Budgeted Item |

Costs |

|

Target staffing levels (187 cases per employee) |

$226.4 |

|

Associated overhead |

49.4 |

|

Call centers |

10.5 |

|

Total General Fund Costs |

$286.2 |

|

Detail does not add due to rounding. |

|

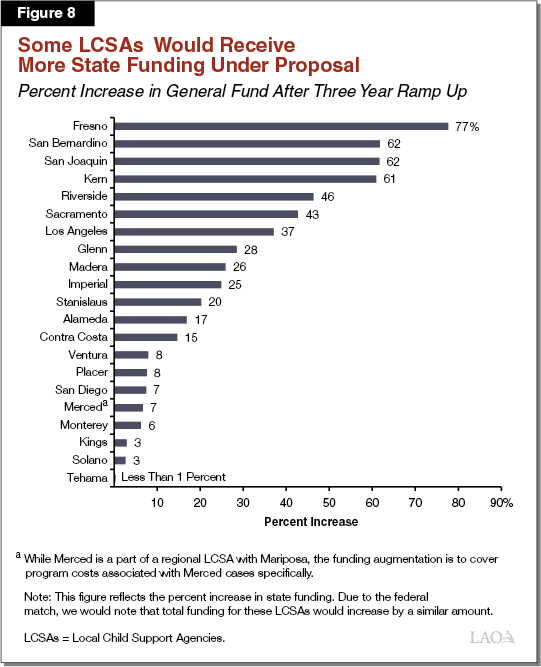

Funding Levels for 21 LCSAs Increased to Equal Calculated Baseline Program Costs. The proposed budgeting methodology calculates baseline program costs for each LCSA by summing staffing, call center, and overhead costs. Based on this amount, the administration identified 21 (of the 49) LCSAs with funding levels below the calculated baseline costs. Over three years, the Governor proposes to increase total funding for these LCSAs by $57.2 million General Fund. This is the amount that is needed to increase funding in each of the 21 LCSAs from current levels to the level calculated for baseline cost under the new methodology. For nearly all of the 21 LCSAs, the additional funding is primarily intended to cover staffing costs in order to achieve the 187 cases‑per‑employee staffing ratio. As shown in Figure 8, for some LCSAs, relative to 2018‑19 state funding levels, the total funding increase is modest (less than 5 percent), while for others the increase is significant (greater than 50 percent).

LCSAs Can Also Receive Performance‑Based Funding. In addition to receiving sufficient funds to meet baseline program costs, LCSAs are eligible to receive performance‑based funding. The budgeting methodology makes available a total of $15 million ($5.1 million General Fund) to reward LCSAs that have increased total child support collections and collections per case. The administration would determine which LCSAs would receive performance‑based funding and allocate the funds accordingly in 2022‑23 (after the $57.2 million has been allocated). It is unclear how often the administration would recalculate LCSA performance for purposes of allocating performance‑based funding and which LCSAs will be eligible to receive performance‑based funding.

Allows LCSAs With Current Funding Levels Above Calculated Program Costs to Keep Excess Funds. Similar to how the budgeting methodology identified LCSAs that do not have enough funding to meet calculated baseline costs, it also identified LCSAs with current funding levels above calculated baseline costs. The Governor proposes to allow these 28 LCSAs to keep the excess funds. By allowing the 28 LCSAs to continue to operate within their existing allocations, by the third year, the Governor’s proposal effectively overfunds the child support program statewide by $17.5 million General Fund relative to the amount the administration calculated as needed to meet baseline program costs—not including performance‑based funding. Over time, in these 28 counties, as operating costs increase due to inflation and increased staffing costs, the caseload to staffing ratios will likely move closer to 187 cases for each employee. This is because as employees leave the LCSA due to attrition, the LCSA may not have enough funding to hire a new employee—effectively increasing the number of cases the remaining employees are handling.

Administration Expects to Increase Collections by 15 Percent Statewide. The administration estimates that total collections will eventually increase by $347 million (15 percent) as a result of increasing funding levels for 21 LCSAs. Of this amount, $65.7 million is estimated to be increased recoupment collections—and therefore benefit the General Fund. The administration assumes the increase in collections will largely be the result of LCSAs hiring more staff (to meet the target staffing ratio of 187 cases‑per‑employee). Specifically, it is expected that by hiring more staff, LCSAs will be able to provide a higher level of service and conduct more case management and enforcement activities, resulting in an increase in the number of paying child support cases. The administration expects that this increase in collections likely will not fully materialize in the near term, given that it will take LCSAs time to hire new staff and make program changes.

Unclear How Budgeting Methodology Will Be Used in Future Years. The administration expects that LCSAs will use the additional funding on items included in the new budgeting methodology (staffing levels, associated overhead, and call centers). The administration’s expectation notwithstanding, LCSAs could use these funds for other purposes—for instance, for marketing and outreach, to purchase or lease new facilities, or to provide salary and benefit increases to existing staff. It is our understanding that the department intends to review and assess the budgeting methodology in future years. The administration, however, has not put forth language to codify the intent of the budget proposal or outline how the budgeting methodology will be used in future years. Fundamentally, the proposed budgeting methodology is based on current circumstances—including caseloads and costs—and it is unclear whether and how the methodology would adjust to reflect changing circumstances over time. For example, without language, it is unclear what will happen if, in future years, additional LCSAs are identified as having more than 187 cases‑per‑employee. Similarly, it is unclear what will happen if, in future years, LCSAs that receive funding under this proposal nevertheless have more than 187 cases‑per‑employee because they used new funding for purposes other than hiring new staff. Finally, it is unclear how the administration will track whether LCSAs used the funds for their intended purpose, per the budgeting methodology.

LAO Analysis

LAO Bottom Line. Longstanding differences in funding across LCSAs raise the concern that some LCSAs may not have sufficient resources to perform core child support tasks, while others may have more than enough funding. In light of this concern, the administration’s proposal to update the methodology is an encouraging sign. In our assessment, though, the administration’s proposal is premature in several ways and raises significant policy questions and concerns. Below, we summarize each of these concepts.

- Existing Funding Structure Raises Concerns. Current state funding for local child support services is largely based on the amount that was spent, by each county DA, to collect and enforce child support payments prior to 1999. These amounts varied significantly across the counties; and, as such, these differences continue today. To our knowledge, wide variation in LCSA funding levels is not based on any particular rationale and likely hinders the state’s goal of ensuring consistent child support services across the state. Notwithstanding variation in funding levels, funding on a per‑case basis has increased significantly for most LCSAs in recent years due to declining caseloads (including more than one‑half of LCSAs that would receive new funds under this proposal). Due to these factors, it is difficult to assess which LCSAs need new funding and which can carry out their core functions within their current resources.

- Proposed New Budget Methodology Premature at This Time. The proposal is premature for various reasons. The Legislature directed DCSS and the LCSAs to identify operational efficiencies that would make the program more cost‑effective and efficient. Operational efficiencies have the potential to reduce budgetary pressure, thereby minimizing, at least in part, the need for additional state funding. The department has not yet identified these opportunities or built them into its proposed budgeting methodology. In our view, it is premature to request additional state funds without fulfilling the Legislature’s directive to also identify cost‑savings measures. In addition, updating child support services to align them with new federal rules could result in significant changes to how LCSAs carry out their key functions. As such, it is premature to institute a new budgeting methodology—one that reinforces longstanding state law and practices—prior to updating state law to align with new federal rules.

- Governor’s Proposal Raises Significant Policy Questions and Concerns. The proposal raises a number of questions and concerns. First, the budget methodology seeks to improve performance by increasing LCSA funding and staffing levels, yet there is evidence that other factors—such as caseload makeup and operational decisions—may also be significant drivers of performance. Second, absent language that provides a framework for the budget methodology going forward, legislative oversight and accountability is limited. Lastly, the proposal does not go far enough to encourage other best practices and does not fully consider the possibility of, and trade‑offs associated with, reducing the proposed state funding augmentation needed to meet baseline program costs in some LCSAs by first “right‑sizing” funding levels for all LCSAs. Right‑sizing funding for all LCSAs would mean redirecting excess funding from 28 LCSAs to the remaining 21 LCSAs identified as not having enough funds to meet calculated program costs.

In the sections that follow, we provide our full analysis of the Governor’s proposed increase in state funding for LCSAs.

Existing Funding Structure Raises Concerns

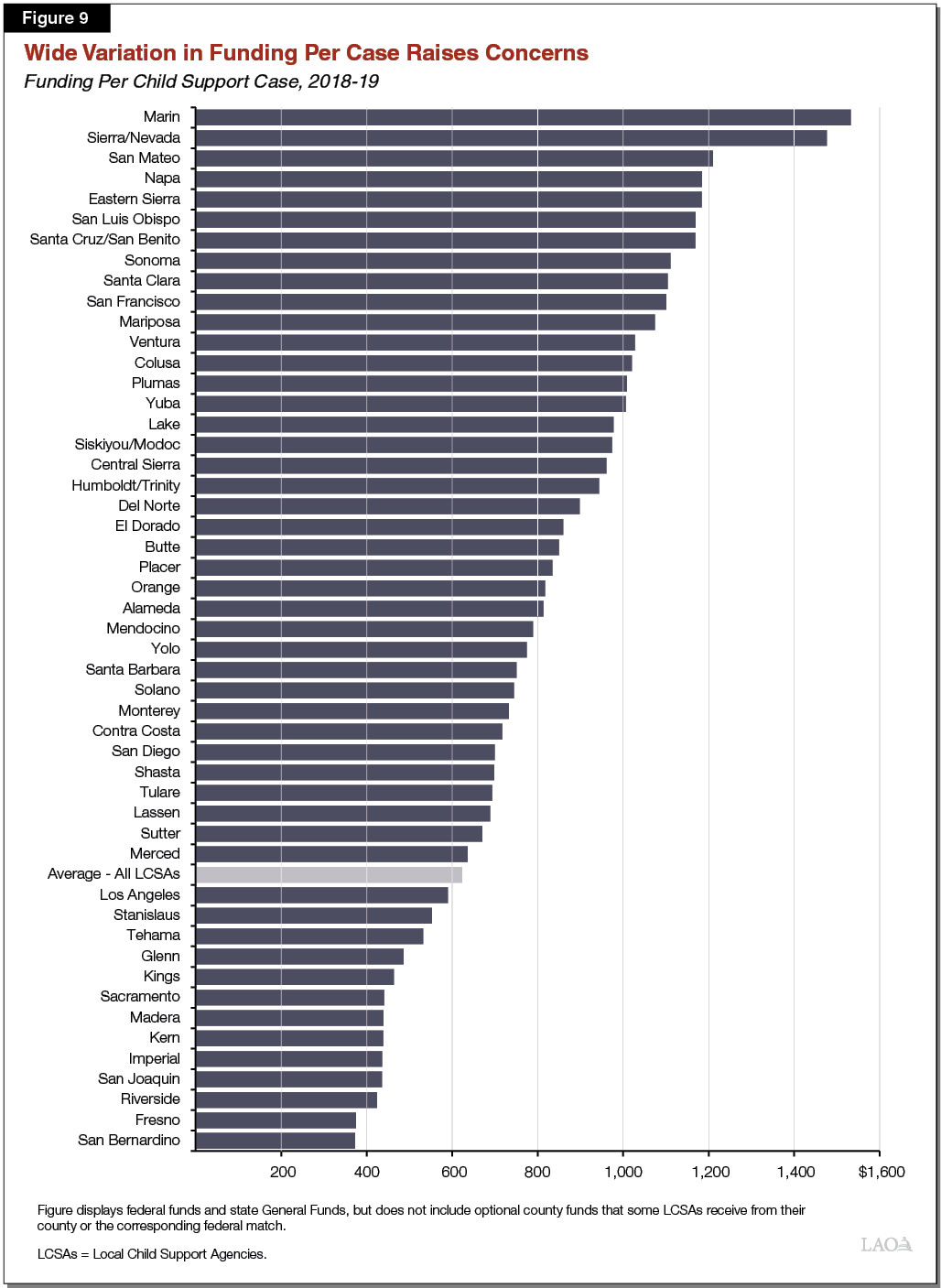

As discussed earlier, current state funding for LCSAs is largely based on the amount spent for these purposes by each county’s DA prior to 1999. These amounts varied significantly across the counties; and, as such, these differences continue today. Figure 9 shows 2018‑19 funding levels per child support case in each LCSA. It shows that many LCSAs receive more than $1,000 per case to carry out child support activities, whereas others receive less than $500 per case. In our view, fundamental differences in the amount of funding LCSAs receive to provide child support services are cause for concern. This is because these differences, to our knowledge, are an artifact of pre‑reform funding levels and operations and do not appear to further any state policy goal or objective. On the contrary, large differences in available resources across the LCSAs conflicts with the state’s goal of ensuring statewide consistency in child support services.

Funding Per Case Has Increased for the Vast Majority of LCSAs, Despite Relatively Flat Funding Over Time . . . State and federal funding for LCSAs has remained relatively flat since 2000. Due to inflation over this period, however, LCSAs now have fewer real resources at their disposal to operate child support today than they had in 2000. At the same time, though, the number of child support cases statewide declined by 28 percent, from more than 1.6 million in 2009‑10 to an estimated 1.2 million cases in 2018‑19. As a result, the vast majority of LCSAs have greater resources today—on an inflation‑adjusted, funding‑per‑case basis—than they did in 2009‑10. On average, LCSA funding‑per‑case has increased by 14 percent since 2009‑10. Funding‑per‑case increased by a larger amount (18 percent), on average, in LCSAs with excess funding under the Governor’s proposal and by a smaller amount (9 percent), on average, in LCSAs identified as underfunded. We note that a portion of the decline in the caseload over this time period could be attributable to some LCSAs taking proactive steps to close certain cases that were deemed “inactive” and unlikely to pay child support. For LCSAs, managing inactive cases likely requires less time and fewer resources than other cases, so closing some of them may not have had the effect of substantially reducing LCSA workload. On the other hand, some of the reduction could actually be attributable to less people seeking assistance through the LCSAs, which would represent a meaningful reduction in workload over this period. It is unclear how much of the caseload decline (and associated increase in funding‑per‑case) is attributable to either of these factors.

. . . But Remained Flat or Decreased in Almost Half of the LCSAs Identified as Underfunded in the Governor’s Proposal. As discussed above, inflation‑adjusted funding‑per‑case increased by 9 percent, on average, in LCSAs identified as underfunded. However, there is wide variation in funding‑per‑case among these LCSAs. Specifically, funding‑per‑case has stayed the same or declined since 2009‑10 for almost half of the LCSAs that would receive new funds. This could be due to local operational costs rising at a faster rate than declines in caseload. Additionally, as previously discussed, this may be due to differences in how LCSAs manage their caseloads, such as not proactively closing inactive cases, or more people seeking services.

Overall, Existing Funding Structure and Recent Caseload Dynamics Complicate Assessment. Due to the concerns raised by the existing funding structure and caseload dynamics—that is, the divergence among LCSAs in how funding‑per‑case has changed in recent years—it is difficult to assess which LCSAs need additional funding to carry out their core functions and which can do so within their current resources. Relatedly, due to this difficulty in assessing funding needs across LCSAs, we question whether it is possible to anticipate, with any certainty, how much LCSA performance and overall collections will improve as a result of receiving additional funding.

New Budget Methodology Premature at This Time

Proposal Is Premature as It Does Not Fulfill Directive to Identify Ways to Reduce Costs. As described earlier, 2018‑19 budget‑related legislation required DCSS, in collaboration with the LCSAs, to submit a report to the Legislature by July 1, 2019 that identifies state and LCSA operational efficiencies that could be pursued to reduce LCSA budgetary pressure. Identifying and enacting operational efficiencies could reduce costs and therefore allow LCSAs to focus staff resources on other priorities. Freeing up staff resources for other priorities would have the same effect on LCSA operations as providing LCSAs more state funding. In this way, reducing costs would help minimize the need for additional state General Fund support for LCSAs. For this reason, in our view, operational efficiencies should be pursued as the state considers how best to update the budget methodology for LCSAs. The Governor’s proposal, however, does not identify significant operational efficiencies at the state or local level and therefore does not fulfill this legislative directive.

Proposal Is Premature as It Does Not Account for Forthcoming Changes. The current proposal is based on existing operations and practices. In this way, the proposal represents a recommitment to existing practices. However, as noted earlier and summarized in Figure 3, the federal government recently issued new child support regulations—through the federal rule—that generally place a greater emphasis on setting orders on actual earnings in order to collect more reliable child support payments. The new rules may result in a major operational shift for the state’s child support system. Implementing these updates to the state’s program may require significant state leadership and legislative involvement and could result in a restructuring of how counties operate child support services. As it relates to the administration’s budgeting proposal, these changes likely would affect LCSA workload, the associated time it takes to complete certain tasks, and ultimately the calculated staffing target. Therefore, the budget methodology now being proposed is premature, given the potential for wide‑ranging changes that could occur in the next few years as the state updates its child support program to comply with the federal requirements.

Raises Significant Policy Questions and Concerns

The Governor’s proposal raises questions and concerns about the following topics: (1) the relationship between funding and performance, (2) legislative oversight and accountability over the budgeting methodology, (3) encouraging streamlined operations, and (4) the trade‑offs associated with shifting excess funding from 28 LCSAs to the remaining 21 LCSAs identified as not having sufficient funds to meet calculated program costs. Below, we discuss these issues in detail.

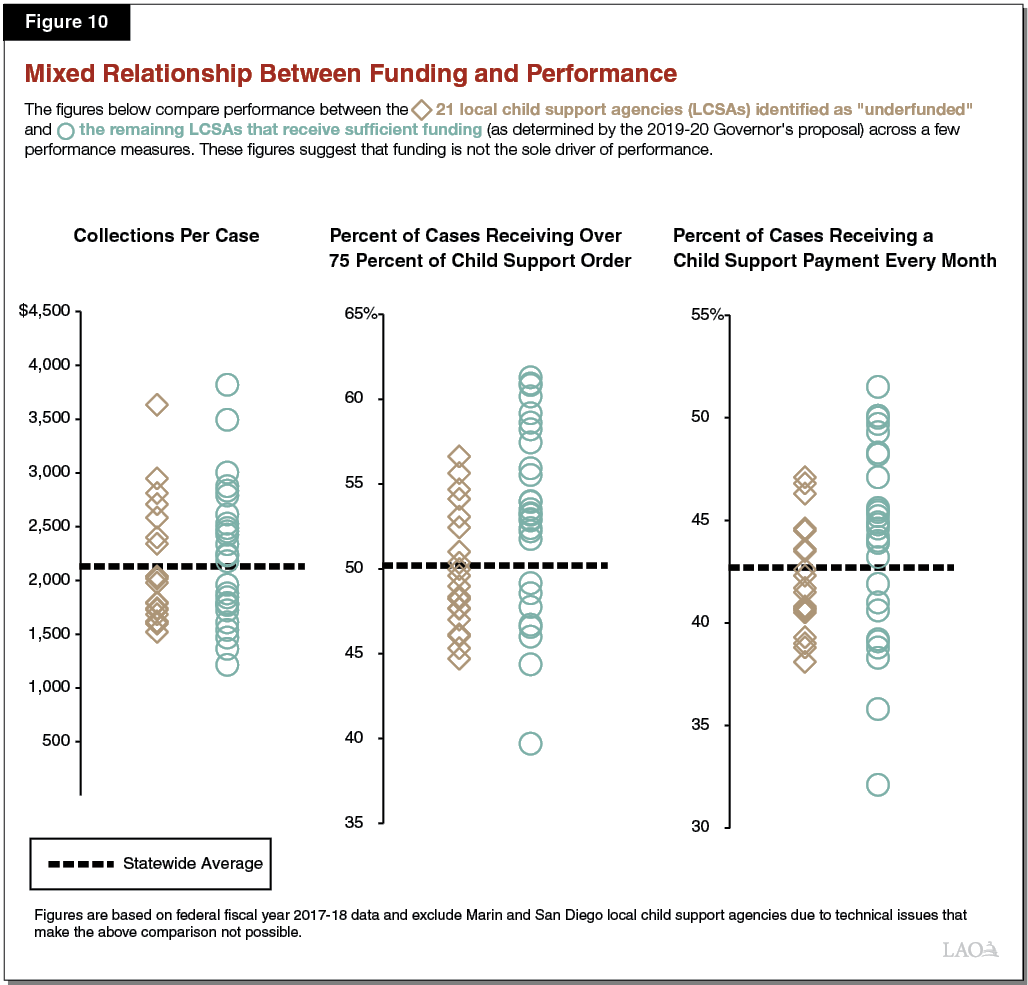

Proposal Does Not Address Other Factors That Affect Performance. The Governor’s proposal assumes that new funding will result in improved performance, mainly in the form of significant increases in collections. Based on our conversations with LCSAs, funding was identified as only one of many drivers of performance, along with program structure, caseload makeup, and local economic conditions. Performance across LCSAs has generally improved over the past five years, even though state funding has remained relatively flat. Additionally, as shown in Figure 10, the top performing LCSAs include some of the 21 LCSAs identified by the new budgeting methodology as not having enough funding to cover calculated baseline program costs. Specifically, four of the top ten counties with the highest collections per case are LCSAs identified by the administration as not having enough funding to meet their calculated baseline costs. Moreover, five of the ten counties that have the lowest collections per case are LCSAs identified as having more than enough funding to cover calculated baseline program costs. A similar mixed relationship between funding and performance is evident across other performance measures, including percent of cases receiving over 75 percent of the child support order and percent of cases that receive a payment every month in FFY 2017‑18.

Overall, funding is not the sole driver of LCSA performance. Additionally, in cases where LCSA performance has remained low, the administration has not offered adequate evidence that flat funding is the primary cause. Despite this lack of evidence, we acknowledge that additional funding may—in some cases—be necessary in order for LCSAs to improve performance. However, the proposal does not consider alternative ways in which performance could be improved. Without this analysis, it is unclear whether the improvements to performance as a result of the Governor’s proposal will fully materialize and if increased funding will have the biggest impact on performance relative to changes that could be made to other performance drivers.

Proposal Lacks Formal Oversight and Accountability Mechanisms. Relative to the longstanding budget methodology, the new budgeting methodology is a more technically complex way to calculate LCSA funding levels. The administration, however, is not proposing language to codify the new budgeting methodology and specify how it will be used in future years. The lack of language raises concerns about oversight and accountability. Specifically, it is unclear how the administration will monitor and hold LCSAs accountable for improving performance and appropriately spending the funds. Below, we describe these concerns in more detail.

- LCSAs Not Required to Demonstrate Improved Performance. In the past, when state funding levels were increased for child support, DCSS was required to report on the impact funding had on performance. The Governor’s proposal does not require LCSAs to demonstrate improved performance as a result of funding. Thus, the funding proposal does not include a way for the state to hold LCSAs accountable for making improvements.

- LCSAs May Use Funds Flexibly, Including for Purposes Outside the Budgeting Methodology. In the past, the Legislature has required DCSS to utilize augmentations to state funds for staffing purposes and report on the impact of that staffing on performance. The new budgeting methodology provides additional state funds to LCSAs with current funding levels below calculated baseline program costs. It is our understanding that the majority of the proposed funding is intended for LCSAs to hire additional staff and eventually reach the staffing level target identified by the administration. Yet, LCSAs are not required to use funds for any specific purpose or report how the funds were ultimately spent. While expenditures on nonstaff items may be appropriate in some cases—and could lead to improved collections—there is no formal way for the Legislature to track how LCSAs spent the increased funding and whether those expenses had any impact on performance.

- Funding Ramp Up Is Not Tied to LCSA’s Ability to Utilize Funds. As previously mentioned, the funding augmentation would ramp up over three years. The first augmentation of funding in 2019‑20 ($19.1 million General Fund in total) reflects a very significant increase in state funding levels—at or above 20 percent for some LCSAs. As a result, some LCSAs may not be able to fully spend their first year augmentation. In that case, it makes sense for future funding augmentations to be paused or delayed until the LCSA has fully spent their initial funding augmentation. The Governor’s proposal, however, does not monitor whether LCSAs have utilized initial funding augmentations or include a way in which future augmentations for an individual LCSA could be paused or delayed. As a result, funds may be allocated prematurely.

- Unclear How Budgeting Methodology Will Be Used in Future Years. Under the Governor’s proposal, it is unclear (1) if and how often the budgeting methodology will be recalculated in future years, (2) under what conditions the administration would propose to increase or decrease funding levels, and (3) if more LCSAs will be eligible to receive additional funding in the future. Additionally, it is unclear if and how often LCSA performance will be calculated for purposes of determining which LCSA will receive performance‑based funding.

- Flexibility in the Use of Funds Could Create Counterproductive Fiscal Incentive. As a result of the budgeting methodology, LCSAs with more cases receive more funding because they need more employees to meet the target staffing level (187 cases‑per‑employee). If LCSAs expect the state to recalculate the funding methodology every few years, they may have a fiscal incentive to keep cases open that otherwise should be closed as a way to increase the number of employees needed to meet the target staffing level. For instance, an LCSA that appropriately closes inactive cases will require fewer employees to work its caseload under the target staffing level. If the state recalculates the funding methodology, though, the LCSA would receive less state funding relative to if it maintained a higher caseload by keeping cases open that otherwise should be closed.

Proposal Does Not Go Far Enough to Identify and Encourage Best Practices. The new budget methodology attempts to encourage LCSAs to choose the most cost‑effective way to respond to calls (either operate their own call center or send their calls to a regional call center). While call centers are one way to achieve operational efficiencies, the Governor’s proposal fails to identify and encourage other operational efficiencies. Based on the results of the time study, it appears that the state could possibly achieve additional operational efficiencies by changing business practices. Specifically, the time study revealed wide variation among 15 LCSAs in the time it takes to establish child support orders. For example, while it took one LCSA five minutes to respond to automated tasks in the case management system, it took another LCSA 240 minutes. Variation could be a sign of concern (in the case that some counties are performing tasks inefficiently) or a sign of innovation (in the case that some counties have identified streamlined practices). Additionally, based on conversations with LCSAs, the wide variation could also be due to things outside of the control of LCSAs. Rather than investigating what is causing the significant difference and whether certain best practices could be incorporated and encouraged in the funding proposal (similar to call centers), the administration simply funds staffing levels at current averages.

Proposal Does Not Fully Analyze the Trade‑Offs of Redirecting Existing Funds Among LCSAs. Although some LCSAs are currently funded above calculated baseline costs and some are funded below baseline costs, the administration does not evaluate the trade‑offs associated with redirecting existing funds from those above to those below. The decision whether or not to redirect existing funds should be based on whether the benefits outweigh the disadvantages. While the administration attempted to quantify improved performance and increases to overall collections as a result of some LCSAs getting more funds—the benefits—it did not analyze the possible effects of some LCSAs losing funds as a result of redirection—the disadvantages. In general, some LCSAs with more than enough funding to cover calculated baseline costs use excess funds to provide services beyond what is required in the child support program—for example, some take on additional workload from other LCSAs through shared services, or remodel or acquire new facilities. To the extent that existing state funds are redirected, these LCSAs may no longer be able to engage in these additional practices. However, the benefit would be that state funding levels for all LCSAs (and statewide) would be “right‑sized,” decreasing the total amount of state General Fund augmentation from $57.2 million General Fund to $40 million General Fund.

LAO Recommendations

Withhold Action Until More Work Is Done

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the current proposal until the administration submits (1) the statutorily required report identifying state and local operational efficiencies and (2) a proposal to refine the current budget methodology based on the findings of the report, as previously directed by the Legislature. Regarding the development of a totally new, wide‑ranging budget methodology, as opposed to refinements, we suggest that the Legislature wait until after the state has updated its program to align with federal guidance before instituting a new methodology. Below, we describe these recommendations in more detail.

Require DCSS to Identify Operational Efficiencies and Propose Refinements Before Action Is Taken. Last year, the Legislature required DCSS to identify state and local operational efficiencies and propose refinements to the current budgeting methodology for the child support program. However, the current proposal does not meet these requirements. Specifically, while it attempts to address funding levels, it does so prior to considering all possible operational efficiencies. Additionally, the administration attempted to improve the cost‑effectiveness of call centers and reward LCSA performance, yet, in our view, the proposal does not go far enough to encourage efficient and cost‑effective business practices. Absent these components, we find that the proposal is premature in that it does not include notable changes to reduce costs.

Legislature Should Expect DCSS to Consider Certain Potential Operational Efficiencies in its Required Report. In advance of the administration’s report to be submitted to the Legislature on July 1, 2019, we suggest that the Legislature specify some of the types of potential state and local operational efficiencies that it expects DCSS to address in its report. Below, we highlight a few examples, based on our conversations with state officials, stakeholders, and numerous LCSA directors, that should be considered:

- Should the State Increase Use of Administrative Practices to Establish Orders? Some child support functions can be performed administratively, while others are judicial and therefore must be approved by a court commissioner. For the purposes of LCSA operations, administrative practices typically require fewer staff resources than going through the court process. According to some LCSA directors, one key way to increase administrative practices is to help parents agree to a child support order before the court hearing. It is our understanding that when LCSAs help parents arrive at pre‑court agreements (known as stipulated orders), noncustodial parents are more likely to make reliable child support payments in the future, which has the effect of reducing LCSA enforcement workload later on. However, not all LCSAs currently prioritize increasing stipulated orders. Thus, we recommend that DCSS identify ways to expand administrative practices and consider the trade‑offs associated with requiring LCSAs to adopt those practices.

- Should DCSS Create State Team to Frequently Evaluate Status of Zero‑Order Cases? In some cases, child support orders are set at zero—referred to as a zero‑order case—if the noncustodial parent has little income or no ability to earn income. This could be the case when the parent is incarcerated, involuntarily institutionalized, or disabled. Some LCSAs expressed that they do not have sufficient resources to audit zero‑order cases and determine if they should remain zero‑order cases, remain open cases, or be closed. A state team that audits zero‑order cases could help right‑size caseloads, reduce workload for LCSAs, and allow for a uniform and standard evaluation of all zero‑order cases. We recommend that DCSS consider whether the state could assume the responsibility of auditing zero‑order cases.

- Should LCSAs Consolidate Uncommon and Complex Cases Into Formalized Centers of Excellence? Similar to how LCSAs currently send uncommon and complex cases to certain LCSAs with the technical expertise, DCSS’ report should identify ways to formalize, and potentially expand, these practices. Additionally, we recommend that DCSS discuss the trade‑off of automatically redirecting these cases to centers of excellence (these arrangements are currently made on an ad hoc, voluntary basis).

- What Are the Costs and Benefits of Redirecting Funding Among LCSAs? In response to relatively flat state funding, some LCSAs have taken steps to relieve their budgetary pressure, including by sending workload to other LCSAs (that have more resources). As an alternative to redirecting workload among LCSAs, DCSS should consider the benefits and trade‑offs of redirecting funding as a way to provide some fiscal relief to certain LCSAs.

Require State to Align Program With New Federal Guidance Before Instituting New Budgeting Methodology. We believe that proposing a new, wide‑ranging budgeting methodology at this time is premature in part because the state has not yet finalized its efforts to align with the new federal guidance regarding child support operations. The federal guidance represents a policy shift for the state’s child support program. Determining how the state will align state policy and program operations with the new federal rules (and how doing so will affect LCSA operations and funding needs) will depend on DCSS’ leadership and could likely require significant legislative involvement. Ultimately, updating the state’s child support program could result in changes to local operations and a corresponding change to funding needs that would require a new, wide‑ranging budgeting methodology. As such, we encourage the Legislature and the state to determine how these changes would affect LCSA operations and funding needs prior to instituting a new, wide‑ranging budgeting methodology.

In the Meantime, Legislature Could Consider Providing Stop‑Gap Funding Until New Methodology Is Instituted. LCSA funding has remained flat for many years and, in some cases, has declined on a funding‑per‑case basis. To address the concern that some LCSAs may not be able to perform their current core functions, the Legislature may wish to consider providing some level of funding augmentations, in the interim, while DCSS completes its statutory report and the state aligns its program with new federal guidance. As discussed earlier, though, it is difficult to accurately assess which LCSAs are unable to perform core functions due to budgetary constraints. In light of this difficulty, if the Legislature wishes to provide LCSAs with some stop‑gap funding, one option would be for it to provide an inflation adjustment to all LCSAs in 2019‑20. This amount, in total, likely would be smaller than the amount proposed under the administration’s proposal, but it also would serve a different purpose. Instead of implementing a new, wide‑ranging methodology, stop‑gap funding would be intended only to provide some fiscal relief until the state updates its program.