LAO Contacts

April 5, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of the Carve Out of Medi-Cal

Pharmacy Services From Managed Care

- Introduction

- Background

- Governor’s Order to Carve Out Pharmacy Services From Medi‑Cal Managed Care

- LAO Assessment of the Carve Out

- Alternative Approaches to Reducing Medi‑Cal Prescription Drug Spending

- Recommendations

Executive Summary

Governor’s Executive Order on State Prescription Drug Spending. In early January 2019, Governor Newsom released an executive order to change and study how the state pays for prescription drugs, with the goal of reducing the state’s prescription drug spending. The executive order features two distinct initiatives, both of which aim to leverage the purchasing power of California to obtain better prices on prescription drugs. This report analyzes one of the two initiatives included in the executive order: to transition—by January 2021—the pharmacy services benefit in Medi‑Cal, the state’s largest low‑income health care program, from managed care to entirely a fee‑for‑service (FFS) benefit directly paid for and administered by the state. (Transitioning a Medi‑Cal service from managed care to FFS for managed care enrollees is referred to as “carving out” a service.)

Carve Out of the Pharmacy Services Benefit Likely to Result in Net Savings to the State. We find that the carve out of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care is likely to generate net savings for the state. While the amount of net state savings is highly uncertain at this time, we believe it could potentially be in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually, as attested by the administration. Primarily, these state savings are likely to arise as a result of the state paying for all drugs dispensed by pharmacies to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries at pharmacies’ cost of purchasing the drugs, as is done in Medi‑Cal FFS. In Medi‑Cal managed care, in contrast, drugs are ultimately paid for at prices negotiated between pharmacies, drug manufacturers, and managed care plans. These negotiated prices—particularly for drugs that receive steep, upfront discounts under a federal drug discount program known as the 340B program—are often higher than what the state would otherwise pay under FFS, raising the cost of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit.

Carve Out Would Significantly Impact Major Medi‑Cal Stakeholders. The carve out would have major and disparate impacts on key Medi‑Cal stakeholders, including enrollees, pharmacies, health care providers, and Medi‑Cal managed care plans. For example, Medi‑Cal enrollees might benefit under the carve out through access to a larger network of pharmacies where they may obtain their drugs and also enjoy a more standardized benefit where which drugs are available no longer depends upon which managed care plans they are enrolled in. On the other hand, going forward, managed care plans would receive significantly less funding (including a profit component) relative to today, largely to reflect the elimination of their responsibility to pay for their members’ pharmacy services. In addition, health care providers, principally hospitals and community clinics that are eligible to participate in the 340B drug discount program, would experience a significant loss of earnings currently generated by the margin between what they pay for pharmacy‑dispensed drugs and what they charge Medi‑Cal managed care plans for those drugs. (These 340B‑related earnings, instead, would convert into savings in Medi‑Cal in the form of lower prescription drugs expenditures.)

Opportunity and Role for the Legislature to Determine Whether and How the Carve Out Proceeds. The administration attests that it has the authority under current state law to effectuate the transition of Medi‑Cal pharmacy services coverage from a managed care to a FFS benefit. Our initial review of state law supports the administration’s view. Nevertheless, the Legislature has the authority and an important role to provide input into how Medi‑Cal pharmacy services are delivered going forward, as we note that the Governor’s action not only is likely to produce net savings, but also involves costs and policy trade‑offs. Given that the Department of Health Care Services (which administers Medi‑Cal) will need new state resources to implement the carve out, the Legislature can provide input into whether and how the carve out proceeds through the approval or rejection in the budget process of any associated future request by the administration for state resources.

Recommend That the Legislature Condition Approval of Future State Resource Requests to Implement the Carve Out on DHCS Providing Key Information. Many details of (1) how the carve out will be implemented and (2) how the administration believes it will affect Medi‑Cal spending and stakeholders have yet to be released. Given the important details that are lacking, we recommend that the Legislature withhold approval of future new state operations resources to implement the carve out until the administration provides key information that adequately answers major outstanding questions. Such information includes, for example:

- A robust fiscal estimate of the carve out, including detail on the estimate’s major underlying assumptions and the additional state administrative resources that would be needed.

- A plan to upgrade the state’s information technology systems to facilitate the real‑time transfer of prescription drug utilization data to managed care plans.

- Prospective guidance for Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ continued role and responsibilities in coordinating and managing their members’ prescription drug utilization.

- What continuity of care protections for managed care enrollees are appropriate to ease the transition to a new statewide Medi‑Cal preferred drug list.

- An analysis of the benefits and trade‑offs of feasible alternatives to the Governor’s plan to reduce prescription drug spending in Medi‑Cal, and how these compare to those of the carve out.

We Offer a Brief Description and Analysis of Select Alternatives to the Governor’s Action to Carve Out Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services From Managed Care. The Governor’s order to carve out the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care represents one approach to achieving savings on prescription drug spending in Medi‑Cal. There are a variety of alternative approaches, some of which have recently been considered but ultimately not implemented in California. In addition to analyzing the Governor’s approach, we briefly introduce and analyze the trade‑offs associated with four alternatives to the Governor’s order. The approaches we analyze are (1) the creation of a universal preferred drug list spanning both FFS and managed care in Medi‑Cal, (2) transferring savings from the 340B drug discount program from providers to the state, (3) formalizing the use of cost‑effectiveness analysis in providing preference to certain drugs over others in Medi‑Cal, and (4) adopting a Medi‑Cal prescription drug spending cap similar to what was recently done in New York State.

Introduction

Rising Prices Have Led to Significant Public Concern. Nationwide, public and private prescription drug spending increased from $259 billion in 2012 to $333 billion in 2017, a significantly faster rate of annual growth (5.2 percent) than general inflation (1.3 percent) and somewhat faster than the growth in health care spending overall (4.6 percent) over this time period. Much of the growth in spending is attributed to rising prescription drug prices, as opposed to greater utilization. In recent years, state and national policymakers have proposed and enacted a number of policy changes to address rising prescription drug prices.

Governor’s Executive Order on State Prescription Drug Spending. In early January 2019, Governor Newsom released an executive order to both study and change how the state pays for prescription drugs, with the goal of reducing the state’s prescription drug spending. The executive order can be separated into two distinct initiatives, both of which aim to leverage the purchasing power of California to obtain better prices on prescription drugs.

- Transition Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Entirely Into a Fee‑for‑Service (FFS) Benefit. The first initiative is to transition the pharmacy services benefit in Medi‑Cal, the state’s largest low‑income health care program, to entirely a fee‑for‑service (FFS) benefit. As such, most Medi‑Cal enrollees—who are enrolled in managed care—would now have this benefit directly administered by the state through FFS as opposed to by their managed care plan.

- Expand the State’s Bulk Drug Purchasing Program. The second initiative would expand the state’s existing bulk purchasing program for prescription drugs. Currently, the Department of General Services negotiates drug prices on behalf of multiple state agencies and programs, such as the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the Department of State Hospitals, and others. Under this second initiative, state agencies with significant spending on prescription drugs are tasked with evaluating existing prescription drug procurement strategies and outcomes, and developing new strategies to reduce prescription drug costs going forward. In addition, the second initiative envisions private entities that pay for prescription drugs, such as commercial health insurers and hospitals, joining together with the state in order to leverage greater collective purchasing power to lower prescription drug costs on behalf of all the participating public and private entities.

This Report Analyzes the Medi‑Cal Initiative. In this report, we focus on the Medi‑Cal component of the Governor’s executive order. We note that the initiative to expand existing state bulk purchasing efforts appears to be in an early stage of development, with the administration’s current activities being focused on surveying existing state drug procurement practices and their associated outcomes. Accordingly, the administration has yet to share what specific strategies to expand upon existing bulk purchasing efforts are under consideration other than the broad concept of encouraging participation by private entities in the state’s negotiations. A meaningful LAO assessment of the merits and drawbacks of the second initiative would require detail on the specific strategies being considered and/or pursued by the administration. In contrast, the strategy behind and potential impact of transitioning Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy services benefit from managed care to FFS are relatively clearer.

The report is laid out as follows. We first provide background on Medi‑Cal coverage of prescription drugs and associated spending. We then introduce the Governor’s action to transition Medi‑Cal pharmacy services entirely to FFS. We assess the Governor’s action and offer several alternative approaches to the Governor’s action to reduce state prescription drug spending, and close with our recommendations.

Background

Brand‑Name Versus Generic Prescription Drugs. A “brand‑name” drug is a drug that is sold under a trademarked name. Brand‑name drugs are often “innovator” prescription drugs, which represent the first instance a particular chemical combination is developed and sold. For a limited period of time—in practice, usually for between 12 and 16 years—these innovator drugs enjoy patent protection that prohibits nonowners of the patent from manufacturing and selling the drug without the owner’s consent. As such, brand‑name drugs are often “single‑source” drugs, meaning that the patent owner has no competitors offering an identical drug for sale within the drug market. A generic drug is a non‑brand‑name drug that is made with the same chemical combination as a currently or formerly available brand‑name drug that has had its patent expire. Typically, generic drugs are “multiple‑source” drugs where multiple manufacturers compete to produce and sell drugs made of identical chemical combinations. In some cases, the original brand‑name drug is no longer sold and only generic drugs are available. In other cases, both a brand‑name drug and generic‑equivalent drugs will be available.

Because there is limited or no competition, single‑source, brand‑name drugs are on average much more expensive than generic drugs. According to the Congressional Budget Office, in the United States, brand name drugs on average are four times as expensive as generic drugs. Among multiple‑source drugs, brand‑name drugs tend to be more expensive than their generic equivalents.

Medi‑Cal Is the State’s Medicaid Program. Medi‑Cal is administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and provides health care coverage to over 13 million of the state’s low‑income residents. Coverage is cost‑free for most Medi‑Cal enrollees. Instead, Medi‑Cal costs are generally shared between the federal and state governments. There are two main Medi‑Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans to provide health care coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Managed care plans are public or private health insurance plans that arrange and pay for the health care of their members.

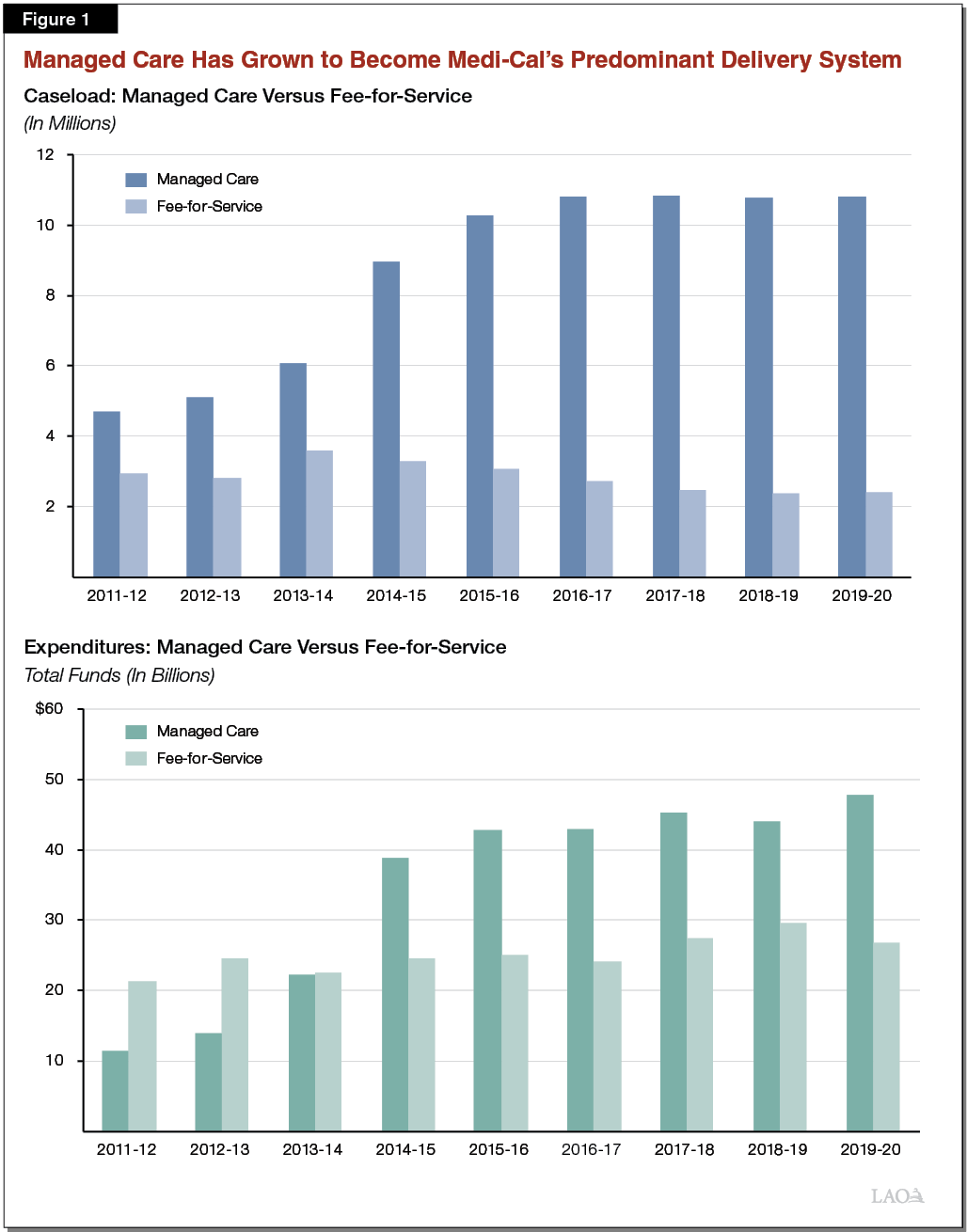

Managed Care Has Grown to Become the State’s Predominant Delivery System. As shown in Figure 1, most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries (82 percent) are now enrolled in managed care. Over time, Medi‑Cal spending has also shifted from FFS to managed care.

Medi‑Cal Covers Pharmacy Services. Medi‑Cal benefits are wide‑ranging, covering, for example, hospital stays, physician services, and care in nursing homes. The federal government requires state Medicaid programs to cover certain services, including the three listed above. Other services are generally considered optional for state Medicaid programs to cover, such as prescription drugs, dental services, and personal care. Medi‑Cal covers prescription drugs, including those delivered in a hospital setting, by a physician, or obtained by a Medi‑Cal enrollee from a pharmacy, such as CVS. If a state opts to cover prescription drugs (which all states do), federal rules effectively require Medi‑Cal to cover nearly all prescription drugs that are available for sale in the United States (though coverage of a specific prescription drug for a given enrollee is dependent on the drug being considered medically necessary to treat a diagnosed condition). In this report, we will focus on prescription drugs obtained from pharmacies, as this constitutes what is referred to as Medi‑Cal’s “pharmacy services benefit” (the subject of the Governor’s executive order). Hospital and physician‑administered drugs, on the other hand, are generally available through Medi‑Cal’s coverage of hospital and physician services and are not directly affected by the Governor’s executive order. (These are drugs that are administered within a hospital or physician office setting, as opposed to being drugs that are prescribed by a physician in such a setting and then subsequently picked up by the patient at a pharmacy.) As is the case for Medi‑Cal benefits broadly, Medi‑Cal pharmacy services are cost‑free for the vast majority of beneficiaries.

Pharmacy Services Spending Reflects About 8 Percent of Overall Medi‑Cal Spending. At around $8 billion in 2018‑19, pharmacy services spending reflects about 8 percent of overall Medi‑Cal spending from all fund sources. Around 70 percent of pharmacy services spending occurs in Medi‑Cal’s managed care delivery system, with the remaining 30 percent occurring in FFS.

How Pharmacy Services Are Paid for in Medi‑Cal

This section provides background on how Medi‑Cal pays for pharmacy services in FFS and managed care.

Fee‑for‑Service

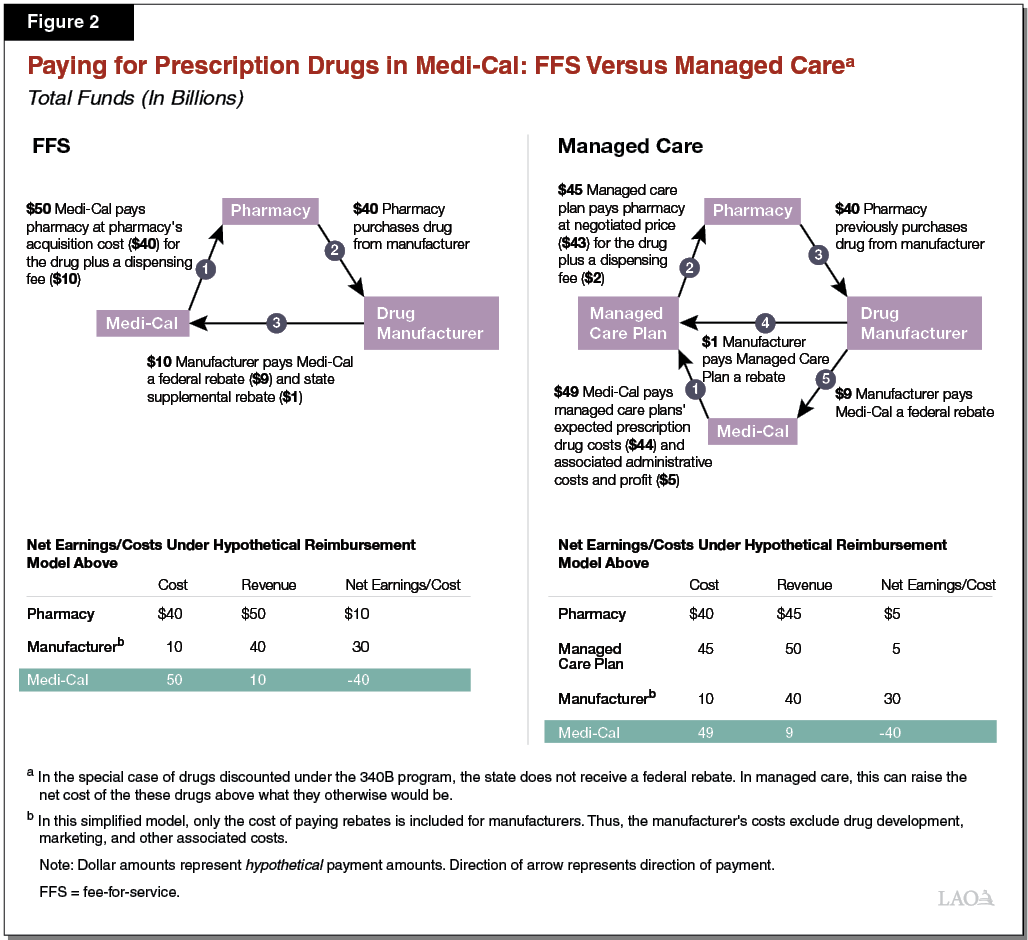

State Directly Pays Pharmacies for Prescription Drugs Obtained in FFS. In FFS, DHCS directly reimburses pharmacies for prescription drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal enrollees. DHCS reimburses pharmacies at their actual cost of acquiring a given prescription drug, plus a dispensing fee that accounts for the pharmacies’ administrative costs in dispensing the drug. While the cost for the prescription drug will vary from drug to drug, the dispensing fee paid by Medi‑Cal is fixed at either $10 or $13 per billing. The network of pharmacies where beneficiaries may obtain drugs paid for through Medi‑Cal FFS extends to the vast majority of all pharmacies in the state. (Figure 2 illustrates how reimbursement for prescription drugs at pharmacies works in Medi‑Cal FFS versus Medi‑Cal managed care, which is discussed later.)

Preferred Drug List Used to Promote Efficacy and Reduce Costs. In FFS, DHCS utilizes a preferred drug list (also known as a “formulary”), which is a list of prescription drugs that may be dispensed through Medi‑Cal FFS without the pharmacy having to seek prior authorization from DHCS. By placing an administrative burden on pharmacies for non‑preferred drugs, selective prior authorization requirements help steer utilization toward drugs that DHCS has deemed to be more cost‑effective than their alternatives. Since, under federal law, Medi‑Cal must cover almost all prescription drugs, the use of a preferred drug list is DHCS’s primary means for guiding utilization of prescription drugs toward cost‑effective options, thereby reducing Medi‑Cal prescription drug costs below what they otherwise would be. Pursuant to state law, DHCS must include at least one prescription drug within each therapeutic class on Medi‑Cal’s preferred drug list. (A therapeutic class of drugs is a set of prescription drugs that are used to treat the same or a similar medical condition. Examples of therapeutic classes of drugs include antibiotics, antidepressants, and antivirals. )

Managed Care

Managed Care Plans Arrange and Pay for the Health Care of Their Members. Medi‑Cal managed care is a delegated service delivery model whereby the state contracts with about 30 public or private managed care plans—such as the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan—to arrange for covered Medi‑Cal services that the state would otherwise arrange and pay for directly through Medi‑Cal FFS or another delivery system, such as county‑administered personal care services. Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ responsibilities are set in state law, state regulations, and in their contracts with DHCS.

Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Funded on a “Capitated” Basis. Medi‑Cal managed care plans are paid on a capitated, or per member, basis in return for arranging their members’ health care services. Managed care plan capitated payments are predetermined amounts of funding per member per month, regardless of the cost of services actually utilized by the member. With a variety of adjustments, the fixed per member per month amounts are set to equal each Medi‑Cal managed care plan’s average costs of providing covered Medi‑Cal services to each of their members.

“Carved‑In” Versus “Carved‑Out” Medi‑Cal Benefits. Medi‑Cal managed care plans are not responsible for arranging and paying for all Medi‑Cal benefits on behalf of their members. Medi‑Cal benefits that are not covered by Medi‑Cal managed care plans are known as carved‑out benefits and are instead available to all Medi‑Cal enrollees through FFS or an alternative delivery system. An example of a carved‑out benefit is personal care services, which is delivered by counties under the In‑Home Supportive Services Program. Benefits that managed care plans are responsible for are referred to as carved‑in benefits. Rather than being set in state law or regulation, DHCS’s contracts with Medi‑Cal managed care plans generally establish which benefits the plans are responsible for covering.

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Are Currently a Carved‑In Managed Care Benefit . . . Medi‑Cal managed care plans are currently generally responsible for providing and paying for the prescription drugs utilized by their members, including drugs obtained at pharmacies. Funding for the pharmacy services benefit under Medi‑Cal managed care is provided through the capitated payments made to plans. A portion of these capitated payments is intended to cover the costs of the prescription drugs dispensed by pharmacies and utilized by managed care plan members, as well as plans’ costs in administering the benefit.

. . . However, Certain Prescription Drugs Are Currently Carved Out of Managed Care and Paid for Through FFS. Although Medi‑Cal managed care plans are currently responsible for covering most prescription drugs, certain therapeutic classes of drugs—primarily, expensive classes of drugs, such as those for hemophilia and HIV—are carved out of managed care and instead paid for directly by the state through FFS.

Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Have Flexibility in How They Design Their Pharmacy Services Benefit. As with their other covered benefits, Medi‑Cal managed care plans have flexibility in how they design and administer the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit. For example, Medi‑Cal managed care plans have the flexibility to:

- Contract With Pharmacy Benefit Managers to Administer Functions of the Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Benefit. Often, managed care plans contract with a type of third‑party administrator—known as pharmacy benefit managers—to help administer certain facets of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit such as, for example, claims processing. For plans that use pharmacy benefit managers, the pharmacy benefit manager may carry out some or all of the functions described in the bullets below on behalf of the plan.

- Establish Their Own Preferred Drug Lists. Medi‑Cal managed care plans may establish their own preferred drug lists. As a consequence, the drugs available to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries without prior authorization can vary from plan to plan. Given financial incentives such as lowering costs, managed care plans’ preferred drug lists heavily steer utilization toward generic drugs. As shown in Figure 3, generic drugs are more heavily utilized in Medi‑Cal managed care compared to FFS.

- Negotiate Prices. Medi‑Cal managed care plans negotiate with pharmacies on the prices they pay for (1) the drug and (2) the dispensing costs of drugs obtained by members. This contrasts with FFS, where each drug’s price is based on pharmacies’ costs of acquiring the drug and a dispensing fee schedule established in state regulation.

- Establish Pharmacy Networks Where Members Must Obtain Prescription Drugs. It is our understanding that Medi‑Cal managed care plans sometimes limit their networks to certain pharmacies within a geographic area in an effort to achieve lower prices. This helps to lower managed care plans’—and, in turn, the state’s—prescription drug costs.

Figure 3

Brand Name Versus Generic

Prescription Drug Utilization in Medi‑Cal

Average Percent of Utilization

in Fiscal Years 2015‑16 Through 2017‑18

|

Brand Name Drugs |

Generic Drugs |

|

|

Managed Care |

6% |

94% |

|

Fee‑for‑Service |

13 |

87 |

Figure 2 compares how drugs are paid for in Medi‑Cal in FFS and managed care, taking into account certain discounts Medi‑Cal receives. We describe these discounts in the next section of the report.

Medi‑Cal Discounts on Prescription Drugs

Federal Law Directs Drug Manufacturers to Provide Best Prices to Medicaid Programs. For a drug to be covered by Medicaid, federal law requires its manufacturer to make it available to Medicaid programs for at least the best price paid by almost any other public or private payer. Federally mandated drug discounts come in the form of rebates from drug manufacturers to state Medicaid programs. Thus, after a drug is dispensed to a Medicaid beneficiary, the state Medicaid program will bill its manufacturer for a rebate payment that ultimately lowers the final, or net, price of that drug. For the remainder of this report, we refer to these federally required Medicaid drug discounts as “federal rebates.”

Since 2014, the State Has Collected Federal Rebates on Prescription Drugs Paid for Through Managed Care. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) made a number of changes to federal law governing Medicaid’s federal rebates. Prior to the ACA, drugs paid for by Medicaid managed care plans were ineligible for federal rebates, and therefore were not necessarily reimbursed by state Medicaid programs at the best price. The ACA expanded states’ authority to collect federal rebates for drugs paid for through Medicaid managed care. Since 2014, pursuant to the ACA, Medi‑Cal has collected federal rebates from manufacturers for drugs paid for through Medi‑Cal managed care.

State Negotiates “Supplemental Rebates” on Top of Federal Rebates, But Only for Prescription Drugs Paid for Through FFS. As previously discussed, DHCS has a preferred drug list that steers utilization toward preferred drugs within Medi‑Cal FFS. In exchange for placement on DHCS’s preferred drug list, drug manufacturers offer supplemental rebates to the state, which are rebates on top of the federal rebates that lower the preferred drugs’ final price below the best price available under the federal rebates. DHCS only collects supplemental rebates on drugs paid for through FFS. The state’s ability to collect supplemental rebates is generally limited to FFS because DHCS’s preferred drug list—which is what gives the state leverage to negotiate further discounts—only applies to drugs paid for through FFS.

Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Negotiate Their Own Rebates. Similarly to the state’s collection of supplemental rebates for drugs paid for through FFS, Medi‑Cal managed care plans collect rebates from drug manufacturers in exchange for placement on their preferred drug lists. Unlike the other Medi‑Cal drug rebates, the state does not receive these rebate revenues directly. Instead, the state accounts for the savings associated with Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ negotiated drug rebates when determining capitated payment amounts. It is our understanding that while these negotiated rebates historically resulted in significant discounts, the magnitude of these rebates declined following the expansion of federal rebates to Medicaid managed care under the ACA.

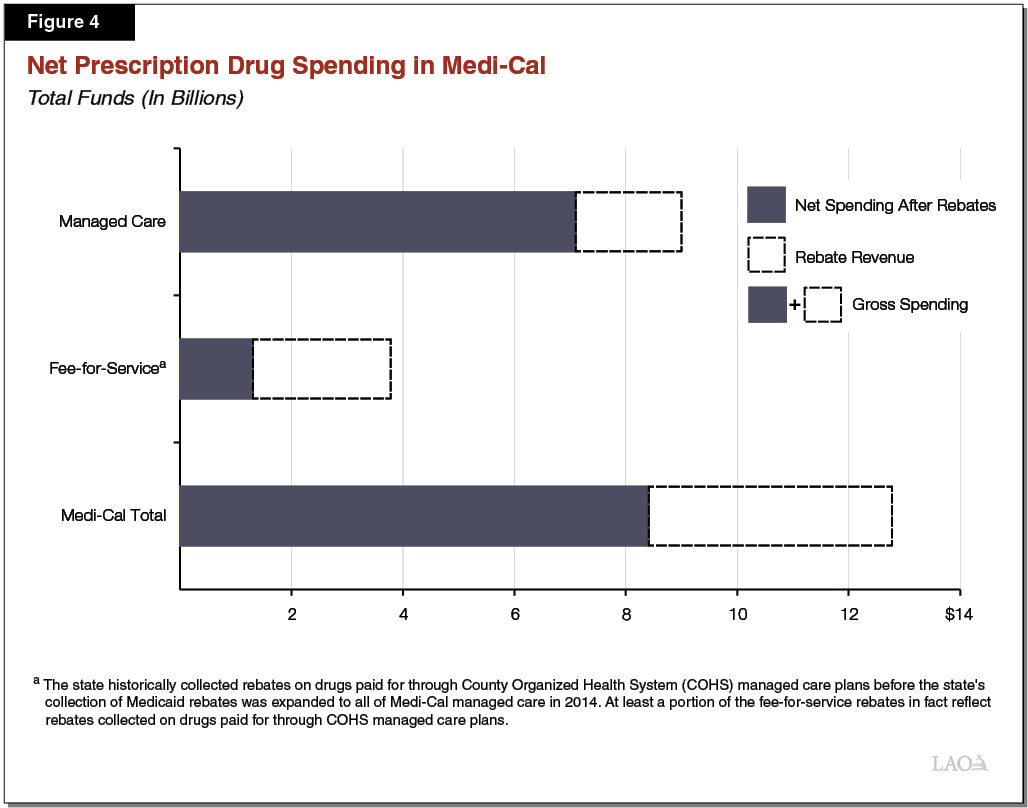

DHCS Collects Billions of Dollars in Rebates Annually. As displayed in Figure 4, DHCS will collect an estimated $4.4 billion in drug rebate revenue in 2018‑19. This rebate revenue is estimated to reduce total net Medi‑Cal spending on prescription drugs from $12.8 billion to $8.4 billion. Federal rebates for drugs paid for through both Medi‑Cal FFS and managed care account for 95 percent of rebate revenue, with supplemental rebates accounting for the remaining 5 percent of rebate revenue. Federal rebate revenue in Medi‑Cal is roughly evenly split between drugs dispensed through FFS and managed care.

The 340B Prescription Drug Discount Program

This section briefly summarizes the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program, and how it operates within the context of Medi‑Cal. For more information on the interaction between the 340B program and Medi‑Cal, see last year’s report: The 2018‑19 Budget: The Governor’s Medi‑Cal Proposal for the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

Many Medi‑Cal Providers Are Eligible for Prescription Drug Discounts Through the 340B Program. The federal 340B program entitles eligible health care providers (mainly hospitals and clinics that serve large numbers of low‑income patients) to discounts on outpatient prescription drugs (drugs that are not administered by a physician or within a hospital setting). These discounts result in savings that benefit participating health care providers and their health care partners, such as the retail pharmacies with which they contract. 340B discounts under federal law are nearly identical in magnitude to those available to Medicaid programs through federal rebates—that is, 340B discounts entitle eligible providers to at least the best price available to almost any public or private payer for each drug. Unlike for Medicaid programs, however, 340B discounts apply at the time a drug is purchased rather than coming in the form of retroactive rebates.

Implementation Challenges Associated With the Use of the 340B Program in Medi‑Cal. Currently, either the 340B program or the Medicaid federal rebate program could potentially apply when a drug is dispensed to a Medi‑Cal enrollee. However, federal law requires that only one of the drug discount programs be used for a given drug dispensed to a Medi‑Cal enrollee, thereby forbidding duplicate discounts. Preventing duplicate discounts in Medi‑Cal has proven a challenge for DHCS, as well as other state Medicaid programs. When drugs that have already received 340B discounts (hereafter referred to as 340B drugs) are dispensed to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, pharmacies are supposed to identify the drug as having already received a 340B discount. Then, DHCS will not bill the drug’s manufacturer for a Medicaid rebate. However, 340B drugs are often not identified as such in a timely manner, creating administrative challenges for DHCS and other affected parties in ensuring Medicaid rebates are sought only on drugs that have not already received a 340B discount.

340B Savings Do Not Necessarily Accrue to the State in Managed Care, as They Do in FFS. As previously noted, in FFS, DHCS pays pharmacies for drugs at their acquisition cost plus a dispensing fee. Because 340B discounts are applied to 340B drugs’ acquisition cost, 340B discounts get passed onto the Medi‑Cal program at the time Medi‑Cal pays for the drugs. This is not necessarily true in Medi‑Cal managed care since plans pay pharmacies at negotiated prices for all the drugs paid for by the plan. These negotiated prices are often higher than the discounted costs associated with acquiring 340B drugs. As a result, 340B eligible providers and their partners, such as retail pharmacies, are able to earn income based on the difference between the prices negotiated with Medi‑Cal managed care plans and the discounted costs of acquiring 340B drugs. The state and federal governments ultimately pay the costs associated with these higher negotiated prices through Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ capitated rates.

Governor’s Order to Carve Out Pharmacy Services From Medi‑Cal Managed Care

All Pharmacy Services Would Be Paid for Through FFS. Under the Governor’s executive order, Medi‑Cal pharmacy services would be entirely carved out of managed care. By January 2021, instead, all prescription drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal enrollees at pharmacies would be paid for through FFS.

Goals of the Governor’s Plan. A principal goal of the Governor’s executive order to carve out the pharmacy services benefit from Medi‑Cal managed care is to reduce prescription drug spending in Medi‑Cal. In addition, the administration believes transitioning Medi‑Cal pharmacy services coverage entirely into a FFS benefit will bring advantages in terms of (1) standardizing the pharmacy services benefit so that there is a single, statewide list of preferred drugs in Medi‑Cal and (2) improving beneficiary access to pharmacies.

Administration Asserts No Statutory Changes Are Needed to Effectuate the Carve Out. The administration asserts that no statutory changes are needed to effectuate the carve out since, under state law and federal rules, the director of DHCS has broad authority to determine, by way of managed care plan contracts, which benefits are carved into managed care and which benefits are carved out. Accordingly, the Governor is not seeking statutory changes at this time to effectuate the carve out. As we discuss in our assessment, while it appears that statutory changes are not needed to effectuate the carve out, this does not prevent the Legislature from exercising its oversight powers to provide input into how pharmacy services are delivered in Medi‑Cal going forward.

Administration Expects Hundreds of Millions of Dollars in Annual Savings to Begin Materializing in 2021‑22. The administration expects to implement the carve out beginning in January 2021. However, significant savings generated by the carve out are not expected to materialize until 2021‑22. Although the administration does not have a precise savings estimate at this time, it has stated that it expects annual savings in the hundreds of millions of dollars once the plan is fully implemented. The administration has stated that it intends to provide a detailed savings estimate at the time of the May Revision.

LAO Assessment of the Carve Out

In this section, we provide our assessment of the Governor’s action to carve out the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care. Specifically, we outline what we believe could be the likely impact of the carve out on (1) state spending; (2) funding for major nonconsumer stakeholders in Medi‑Cal such as managed care plans, health care providers, and drug manufacturers; and (3) the quality of care Medi‑Cal beneficiaries receive.

Carve Out Likely to Result in Net Savings to the State

In our view, the carve out is likely to result in net savings to the state, but of an unknown magnitude. The administration’s rough and preliminary estimate of hundreds of millions of dollars in annual state savings appears possible but is highly uncertain.(We would note that total Medi‑Cal savings will be more than double annual state savings. Because the federal government shares in the costs of funding pharmacy services in Medi‑Cal, a portion of total savings generated under the carve out—about 60 percent—would accrue to the federal, as opposed to state, government.) Below, we summarize how the carve out will affect Medi‑Cal financing of pharmacy services and explain why net state savings are likely, though not guaranteed, to materialize.

State Savings Under a Full Carve Out. The carve out can be expected to generate savings in Medi‑Cal in two primary ways, the first of which is likely and the second of which brings greater uncertainty.

- Lower Spending by Paying for Drugs at Cost. As previously noted, Medi‑Cal managed care plans reimburse pharmacies at negotiated prices for prescription drugs. These drug prices (not including pharmacy dispensing fees, which we address below) are likely higher than the pharmacies’ costs in acquiring the drugs, particularly for 340B drugs that receive significant, federally mandated discounts. Medi‑Cal FFS, on the other hand, reimburses pharmacies for drugs at prices that are meant to be equivalent to pharmacies’ costs of acquiring the drugs. As a result, pharmacies have limited or no ability to mark up the prices of the drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries under FFS. Under the full carve out, pharmacy markups would be eliminated on behalf of $9 billion in additional drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal enrollees through FFS rather than managed care. This could potentially generate significant annual Medi‑Cal savings, in large part due to the state paying for 340B drugs at cost.

- Potentially Increased Savings Due to Greater Supplemental Rebates. As previously discussed, the state currently collects supplemental rebates on top of federal rebates, but only for drugs paid for through FFS (and certain select managed care plans). By fully transitioning the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit into FFS, the state should be able to begin collecting supplemental rebates for a significantly higher proportion of the drugs paid for under Medi‑Cal, potentially increasing state savings on drugs relative to today. These greater state supplemental rebates would be in place of the negotiated rebates currently received by Medi‑Cal managed care plans. Provided the state supplemental rebates result in lower net drug prices than what is achieved from Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ negotiated rebates, the state would achieve savings.

Savings Partially Offset by Higher Costs, Such as for the Dispensing of Drugs to Medi‑Cal Beneficiaries. While we believe the carve out is likely to generate savings, as discussed immediately above, we expect there to also be some higher costs that partially offset the savings described above. Most notably, we would anticipate potentially higher state costs due to the increase in dispensing fees that Medi‑Cal would pay under the full carve out. As previously noted, in FFS, Medi‑Cal currently pays significantly higher dispensing fees to pharmacies than Medi‑Cal managed care plans pay. Paying FFS‑level dispensing fees for all prescription drugs paid for in Medi‑Cal—absent changes to Medi‑Cal FFS dispensing fees—would thus increase spending for this purpose above current levels.

Costs to Administer Pharmacy Services Would Shift From Managed Care Plans to the State, With Uncertain Net Fiscal Impact to the State. Most of the costs of administering the pharmacy services benefit would shift from managed care plans to the state, which we believe will require new state resources. Whether the required new state resources will be greater or less than existing funding for managed care plans to administer the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services is uncertain. Accordingly, the overall impact of the carve out on the state’s costs of administering the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit is uncertain.

Net State Savings Likely. We believe the increased state savings due to (1) reimbursing pharmacies at cost for their drugs and (2) collecting supplemental rebates are likely to be greater than the increased costs under the carve out, such as those associated with potentially paying higher pharmacy dispensing fees under FFS. We believe these net state savings could potentially be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, as attested by the administration. However, the amount of savings is highly uncertain for many different reasons, including, for example, the challenge of predicting the results of future negotiations between the state and drug manufactures on Medi‑Cal prescription drug costs going forward.

Impact of Carve Out on Major Nonconsumer Stakeholders

The carve out will significantly impact a variety of providers and other entities that serve the Medi‑Cal program. This section describes these impacts on nonconsumer stakeholders in the Medi‑Cal program.

Reduction in Retained 340B Earnings for Eligible Providers. As described earlier, health care providers eligible for 340B drug discounts currently are able to generate earnings based on the difference between the discounted prices at which they purchase 340B drugs and the higher prices they charge payers for the 340B drugs. These payers include, for example, private health insurers, Medicare (the federal health care coverage program primarily for the elderly), and Medi‑Cal managed care plans, but exclude Medi‑Cal FFS, which pays for 340B drugs at their acquisition cost. While eligible providers could continue to generate earnings through 340B for drugs dispensed to non‑Medi‑Cal enrollees, by transitioning Medi‑Cal pharmacy services entirely to a FFS benefit, 340B‑eligible providers would no longer be able to generate earning on any pharmacy‑dispensed drugs paid for by Medi‑Cal. Rather, these earnings would largely convert into state savings in the form of lower prescription drug expenditures.

Reduction in Funding for Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans. Funding for Medi‑Cal managed care plans would likely be reduced by between 15 percent and 20 percent under the carve out. While this reduction in funding largely reflects managed care plans’ decreased funding responsibilities—due to no longer paying for the pharmacy‑dispensed drugs utilized by their members—a portion of the reduction would likely come from existing Medi‑Cal managed care plan funding for purposes such as administration, care coordination, reserves, and profits.

Minimal Impact on Drug Manufacturing Industry. The carve out is unlikely to have a major impact on earnings for the drug manufacturing industry overall, both in the state and nationwide. Selected drug manufacturers, however, may pay higher negotiated supplemental rebates to the state in exchange for greater utilization of their drugs in Medi‑Cal through placement on a more widely applicable Medi‑Cal‑wide preferred drug list. That said, we would not expect the magnitude of the rebates to have a major impact on the drug manufacturing industry’s overall earnings.

Likely Increase in Funding for Pharmacies. Pharmacies will potentially benefit from increased funding under the carve out due to (1) (absent any changes) the higher dispensing fees paid by Medi‑Cal FFS compared to Medi‑Cal managed care plans and (2) the larger network of pharmacies serving Medi‑Cal FFS compared to individual Medi‑Cal managed care plans. A portion of the increase in funding may be offset by lower reimbursement for the drugs since Medi‑Cal FFS, but not Medi‑Cal managed care, pays pharmacies at close to pharmacies’ costs in acquiring their drugs.

Impact of Carve Out on Beneficiary Access and Care

In addition to likely generating net savings for the state and having disparate fiscal impacts on key nonconsumer stakeholders in the Medi‑Cal program, the carve out will very likely affect Medi‑Cal beneficiary access to quality care. This section explores a few of the likely impacts on beneficiary care.

Statewide Standardization of the Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Benefit. One potential benefit of the transition of Medi‑Cal pharmacy services to a FFS benefit is that the same preferred drug list would apply to all Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Currently, which drugs are readily available to Medi‑Cal enrollees can vary depending upon which Medi‑Cal managed care plan they are enrolled in. Although almost all drugs are ultimately available to Medi‑Cal enrollees regardless of which delivery system or managed care plan they are enrolled in, different Medi‑Cal managed care plans and Medi‑Cal FFS maintain different preferred drug lists. Obtaining a non‑preferred drug comes with administrative burdens. For Medi‑Cal enrollees that move counties, change plans, or change from FFS to managed care (or vice versa), there may be challenges associated with continuing on a drug that was on the enrollee’s previously applicable preferred drug list but is not on the new list. With the transition of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit to FFS, a single, statewide Medi‑Cal preferred drug list would likely apply for all program beneficiaries, thereby increasing the standardization of the Medi‑Cal drug benefit. While the standardization of the Medi‑Cal drug benefit under the carve out has potential to improve care from a beneficiary perspective in the long run, the transition to FFS could result in beneficiaries losing ready access to drugs they are currently taking. As such, the Legislature may wish to consider continuity of care protections for beneficiaries currently utilizing prescription drugs.

Expansion of the Pharmacy Network Where Beneficiaries Can Obtain Prescription Drugs. According to the administration, Medi‑Cal’s FFS pharmacy network extends to almost all pharmacies throughout the state. This contrasts to Medi‑Cal managed care to the extent that at least certain plans exclusively contract with only some of the pharmacies in their areas of operations. While this practice is likely effective in lowering costs, it does limit the number of pharmacies where Medi‑Cal managed care enrollees can obtain their prescription drugs. Thus, transitioning pharmacy services coverage to a FFS benefit could give Medi‑Cal enrollees greater choice in where they obtain their prescription drugs.

Potential Negative Impacts on Care Coordination and Management. Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ primary responsibilities include providing care coordination and management for their members. While the carve out could bring the potential benefits described above, the coordination and management of Medi‑Cal beneficiary’s prescription drug use could be weakened under the administration’s plan. Below, we outline areas where care coordination and management could be negatively impacted under the carve out.

- Less Timely Prescription Drug Utilization Information for Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans. Medi‑Cal managed care plans, and/or their contracted providers, currently receive data—often in real‑time—from pharmacies when their members fill their prescriptions. These data assist the managed care plan—particularly for relatively sick members enrolled in disease management programs—in coordinating their members’ care. For example, by informing a managed care plan when a prescription is filled, the plan’s designated care coordinator can learn whether the member is adhering to the schedule recommended for her or his prescription. As previously stated, certain drugs are currently carved out of managed care. While DHCS provides FFS prescription drug utilization data to managed care plans on behalf of their members for currently carved out drugs, it is our understanding is that this data does not arrive from DHCS in a timely enough manner to assist plans’ care coordination activities.

- Opioid Curtailment Programs. Some Medi‑Cal managed care plans have proactively developed initiatives aimed at curtailing the overuse of prescription opioids, which were responsible for around 1,500 overdose deaths in the state in 2017. These programs, for example, place elevated prescribing restrictions on opioids and attempt to educate prescribers on safe opioid prescribing practices. In many counties, these initiatives have likely contributed to dramatically reducing the number and potency of opioid prescriptions among Medi‑Cal members. Under the carve out, it is uncertain whether such initiatives by Medi‑Cal managed care plans would continue.

Important Details on the Carve Out Are Lacking

Many details of (1) how the carve out will be implemented and (2) how the administration believes it will affect Medi‑Cal spending and stakeholders have yet to be released. To some degree, this is likely due to many aspects of the policy and implementation framework remaining in development by the administration. Below are several outstanding pieces of information that could help the Legislature assess the potential benefits and downsides of transitioning Medi‑Cal pharmacy services entirely to a FFS benefit.

- Overall Fiscal Estimate. While the administration has shared that it projects annual savings in the hundreds of millions of dollars, it has not released a precise fiscal estimate of the carve out that also outlines its major assumptions. A more precise fiscal estimate, with clearly laid‑out assumptions, is necessary to be able to fully understand and weigh the potential trade‑offs of the carve out.

- What New State Resources Are Needed to Administer the Entire Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Benefit? We believe new state staff, contracting authority, or both will be necessary to administer the entire Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit through FFS. In addition to lacking an overall fiscal estimate, the administration has not identified what new state resources are required to implement the carve out.

- How Would State Information Systems Be Improved to Maintain or Improve Existing Managed Care Plan Care Coordination? As previously noted, Medi‑Cal managed care plans use prescription drug utilization data in the coordination and management of their members’ care. The state currently provides prescription drug utilization data to managed care plans for currently carved out drugs, but these data transfers are not timely or always complete. The administration, to date, has not released a plan to improve DHCS’s information systems to facilitate the timely transfer of prescription drug utilization data between the state and Medi‑Cal managed care plans.

- Managed Care Plans’ Continued Role in Coordinating the Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Benefit in Conjunction With Their Members Overall Health Care. Medi‑Cal managed care plans are generally responsible for coordinating and managing the care of their members. Under the carve out, it is unclear what Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ role would be in coordinating and managing their members’ care in relation to the pharmacy services benefit. For example, it is unclear whether Medi‑Cal managed care plans would continue to have a role in curtailing the overuse of opioids or tracking medication adherence among their members.

- Continuity of Care Protections. The administration has not shared what, if any, continuity of care protections would be put in place to allow beneficiaries currently utilizing drugs on their managed care plans’ preferred drug list to continue to use those same drugs—at least in certain situations—even if they are not on Medi‑Cal’s statewide preferred drug list under the carve out.

Opportunity and Role for Legislative Oversight

The administration attests that it has the authority under current state law to effectuate the transition of Medi‑Cal pharmacy services coverage from a managed care to a FFS benefit. Our initial review of state law supports the administration’s view as state law appears to give the director of DHCS fairly broad authority to selectively include or exclude Medi‑Cal benefits from managed care plans’ contracts with the state.

Nevertheless, we believe the Legislature has the authority to provide input into how prescription drugs are covered in Medi‑Cal going forward. We think that this is an important oversight role for the Legislature to exercise, in part because the Governor’s executive order action involves not only savings but also costs and policy trade‑offs. For one, the Legislature can enact statute constraining the administration’s ability to unilaterally effectuate the carve out, for example, by setting conditions on its implementation. Additionally, given that new state resources are needed to implement the change, we believe the Legislature can provide input into whether and how the carve out proceeds through its approval or rejection in the budget process of any associated future request by DHCS for additional state resources.

Alternative Approaches to Reducing Medi‑Cal Prescription Drug Spending

The Governor’s order to carve out the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care represents one approach to achieving savings on prescription drug spending in Medi‑Cal. There are a variety of alternative approaches, some of which have recently been considered but ultimately not implemented in California. Below, we introduce several of these alternative approaches, each of which brings different benefits and trade‑offs relative to the status quo and to the Governor’s approach. These alternative approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and thus could potentially be implemented as part of a broader package of changes.

Universal Medi‑Cal Preferred Drug List Spanning FFS and Managed Care

Background. Currently, the state has a preferred drug list that only applies to drugs obtained through Medi‑Cal FFS. One approach to potentially lowering Medi‑Cal prescription drug spending would be to adopt a universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list that would apply to all drugs dispensed to all 13 million Medi‑Cal beneficiaries across the FFS and managed care delivery systems. This would work toward standardizing the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit, as with the Governor’s approach. By employing a universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list, drug manufacturers would likely be willing to offer steeper discounts (in the form of supplemental rebates) in exchange for their drugs’ placement on the list. In 2014, Governor Brown proposed to adopt a universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list. However, this proposal was ultimately not approved by the Legislature.

Benefits Relative to the Governor’s Approach. Unlike the carve out, the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit would continue to be provided as currently by Medi‑Cal managed care plans, though they would have significantly less discretion over the benefit’s design. This would lessen the disruption to plans’ existing care coordination and management activities related to their members’ prescription drug usage. The state would also continue to benefit from the lower dispensing fees paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans compared to Medi‑Cal FFS.

Downsides Relative to the Governor’s Approach. State savings would likely be significantly lower under a universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list, as the sole approach, compared to the Governor’s approach. The primary reason is that existing 340B savings could remain with 340B‑eligible providers and their partners, rather than transferring to the state in the form of lower prescription drug costs.

Transfer Savings From 340B Drug Discounts in Medi‑Cal to the State

Background. As previously discussed, in Medi‑Cal managed care, at least a portion of the savings associated with the 340B discounts can be retained by eligible providers and their partners. Eliminating the use of 340B discounts in Medi‑Cal would have the effect of making additional drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal enrollees eligible for alternative drug discounts available under federal Medicaid law, likely resulting in savings for the state. This approach was proposed by Governor Brown in 2018, but was not ultimately adopted. A slightly different approach that could achieve similar outcomes would be to require Medi‑Cal managed care plans to pay for 340B drugs at the drugs’ acquisition costs. For additional background, see our report on Governor Brown’s 2018 proposal to eliminate the use 340B drugs in Medi‑Cal.

Benefits Relative to the Governor’s Approach. Eliminating the use of 340B discounts in Medi‑Cal or restricting payment to 340B drugs’ acquisition costs would maintain Medi‑Cal managed plans’ existing level of responsibility and discretion over the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit for their members. As with the universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list, this would allow plans to continue existing care coordination and management activities related to their members’ prescription drug usage. In addition, making changes to the use of 340B drugs in Medi‑Cal would not necessarily require new resources for DHCS and may even further simplify administration of Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy services benefit relative to the status quo and the Governor’s approach.

Downsides Relative to the Governor’s Approach. As previously discussed, the principal way DHCS can increase supplemental rebates provided directly to the state, and thereby potentially generate additional savings on pharmacy services spending in Medi‑Cal, is to extend the reach of its preferred drug list. As such, total state savings may not be as high as under the carve out since changes only to the use of 340B drugs in Medi‑Cal would not affect the scope of the preferred drug list. In addition, this approach would not serve to standardize Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy services benefit, as managed care plans would continue to be able to design their own preferred drug lists and other aspects of the pharmacy services benefit.

Formalize the Use of Cost‑Effectiveness Analysis for Preference of Drugs in Medi‑Cal

Background. Another potential approach to reducing the costs and improving the effectiveness of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit would be to formalize the use of cost‑effectiveness analysis in decisions about which drugs are placed on Medi‑Cal’s preferred drug list. Cost‑effectiveness analysis generally provides a formal structure for evaluating whether an intervention, such as the utilization of a given prescription drug, is justified at its cost. Cost‑effectiveness analysis is used in other countries and by some U.S. health insurers to help determine which prescription drugs to make readily available and at what levels of reimbursement. While DHCS is currently required under state law to evaluate the safety, effectiveness, and cost of drugs under consideration for inclusion on the Medi‑Cal preferred drug list, it is unclear how DHCS’s process for selecting preferred drugs compares to the formalized cost‑effectiveness analysis approaches used in other countries. As such, the Legislature could take steps to explore greater use of cost‑effectiveness analysis in deciding which prescription drugs are placed on Medi‑Cal’s preferred drug list.

Benefits Relative to the Governor’s Approach. On its own, the use of cost‑effectiveness analysis in designing Medi‑Cal preferred drug list may not generate significant savings on prescription drugs. This is because Medi‑Cal’s preferred drug list only applies to the minority of drugs paid for in Medi‑Cal through FFS. However, were it employed in conjunction with either a full carve out of the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit or a universal Medi‑Cal preferred drug list, it could potentially generate significant long‑run savings while also improving the quality of care Medi‑Cal beneficiaries receive.

Downsides Relative to the Governor’s Approach. Creating the infrastructure to formalize the use of cost‑effectiveness analysis in drug preference decisions would require new ongoing state resources.

Adopt a Medi‑Cal Prescription Drug Spending Cap

Background. In 2017, New York State enacted a cap on drug spending in its Medicaid program. Exceeding the statutory cap, which limits growth in drug spending in its Medicaid program to around 8 percent annually, triggers the negotiation of additional rebates with manufacturers of drugs whose cost growth contributed to surpassing the statutory cap. New York State will identify targeted rebate amounts from these manufacturers. Should a manufacturer not voluntarily offer rebates close to the amounts targeted by the state, the state may (1) impose prior authorization requirements for all drugs made by the manufacturer; (2) direct its Medicaid managed care plans to remove the manufacturer’s drugs from their Medicaid formularies (as long as there are other options within the drug’s therapeutic class); and (3) require the manufacturer to provide information to New York State on the high‑cost drug’s costs to develop, the drug’s prices available to various purchasers, and the drug’s profitability. As a result of the cap, New York State expected to reduce drug spending in its Medicaid program by 11 percent in 2018.

Benefits Relative to the Governor’s Approach. New York’s approach is similar to Governor’s Newsom’s executive order to carve out Medi‑Cal pharmacy services coverage insofar as it attempts to leverage the full bargaining power of its state Medicaid program to obtain better prices. However, it goes farther than the carve out by (1) establishing a specific intention to exclude all of a manufacturer’s drugs from its Medicaid preferred drug list should it find any of the manufacturer’s drugs to be growing excessively in cost and (2) requiring financial information from drug manufacturers, beyond what California law requires, on their costs and earnings. These more stringent requirements may assist New York’s Medicaid program in reducing net drug spending to a greater degree than California would be able to solely under the carve out.

Downsides Relative to the Governor’s Approach. New York State’s approach to reducing its Medicaid program’s drug spending likely has downsides as well. For one, barring all of a manufacturer’s drugs from the preferred drug list in cases where the manufacturer does not offer sufficient rebates likely goes further in limiting beneficiary access to certain drugs than under the California administration’s approach. Fiscally, adopting New York’s approach would not, on its own, lead to the state sharing in more of the savings generated by the 340B program. As such, it is uncertain whether adopting such an approach would generate more savings in Medi‑Cal than Governor Newsom’s approach. That said, we would note that adopting New York’s approach could be done in conjunction with the carve out or with the other alternative approaches previously described, and thus potentially go further than Governor Newsom’s approach in reducing drug spending in Medi‑Cal.

Recommendations

Leverage Oversight Powers to Gather Key Information Before the Carve Out Is Effectuated. We find that the carve out has merit given its potential to generate net state savings, which we believe could be in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually, as also attested by the administration. However, we have a number of unanswered questions and concerns, particularly about how the carve out will impact the coordination and management of beneficiary care. We therefore advise the Legislature to leverage its oversight powers to gather key information before the carve out is implemented.

Condition Resources to Implement the Carve Out on DHCS Providing Key Information That Convincingly Answers Outstanding Questions. We do not believe the carve out should be effectuated until after the administration provides key information and a detailed implementation plan. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature withhold approval of future new state administrative resources requested by DHCS to implement the carve out until DHCS provides key information that convincingly answers major outstanding questions. This key information includes, but is not limited to, the following.

- A robust fiscal estimate of the carve out, including detail on the estimate’s major underlying assumptions and the additional state administrative resources that would be needed.

- A plan to upgrade the state’s information technology systems to facilitate the real‑time transfer of prescription drug utilization data to managed care plans.

- Prospective guidance for Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ continued role and responsibilities in coordinating and managing their members’ prescription drug utilization.

- What continuity of care protections for managed care enrollees are appropriate to ease the transition to a new statewide Medi‑Cal preferred drug list.

- An analysis of the benefits and trade‑offs of feasible alternatives to the Governor’s plan to reduce prescription drug spending in Medi‑Cal, and how these compare to those of the carve out.