LAO Contacts

April 25, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

California State Library

Local Assistance Proposals

In this brief, we analyze the Governor’s proposals to provide one‑time General Fund for two local library initiatives—the Zip Books program and Lunch at the Library. We begin with an overview of the State Library and local libraries in California. We then describe and assess each proposal and offer associated recommendations.

Overview

State Library Oversees Both State Programs and Local Initiatives. The State Library’s main functions are (1) serving as the central library for state government; (2) collecting, preserving, and publicizing literature and historical items; and (3) providing specialized research services to the Legislature and the Governor. In addition, the State Library passes through state and federal funds to local libraries for specified purposes and provides related oversight and technical assistance. These local assistance programs fund literacy initiatives, Internet services, and resource sharing, among other things. In 2018‑19, the State Library is receiving $64 million from all fund sources, of which $27 million is for statewide operations and $37 million is for various local initiatives. Of total funding, 67 percent comes from General Fund, 29 percent comes from federal funds, and the remaining 4 percent comes from various state special funds.

Public Libraries Are Run and Funded Primarily by Local Governments. In California, local public libraries can be operated by counties, cities, special districts, or joint powers authorities. Usually the local government operator designates a central library to coordinate activities among all the library branches within a jurisdiction. In 2018‑19, 185 library jurisdictions with 1,119 library branches are operating in California. Local libraries provide a diverse set of services that are influenced by the characteristics of their communities. Most libraries, however, consider providing patrons with access to information a core part of their mission. More than 95 percent of local library funding comes from local governments and the remaining 5 percent comes from state and federal sources.

Governor Proposes to Fund Two Local Library Initiatives on a One‑Time Basis. The two initiatives are: (1) the Zip Books program and (2) Lunch at the Library. Both initiatives received one‑time General Fund appropriations in previous years. The remaining two parts of this brief provide our analysis of each proposal.

Zip Books Program

In this part of the brief, we analyze the Governor’s proposal for the Zip Books program. We first provide relevant background, then describe the Governor’s proposal, assess the proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

In this section, we provide background on (1) library resource sharing in the state; (2) interlibrary loans, a common way libraries share resources; and (3) the Zip Books program, which is considered to be an alternative to interlibrary loans.

Library Resource Sharing

California Library Services Act (CLSA) Establishes Library Resource Sharing as a State Interest. Established in 1977, CLSA declares that the state has an interest in ensuring “all people have free and convenient access to all library resources and services that might enrich their lives.” To promote equitable access to resources, the act aims to ensure libraries are granting their patrons access to resources available in libraries throughout the state. In establishing this goal, the act also declares libraries are to be locally controlled and financed, and that any state funding supplement, rather than supplant, local resources.

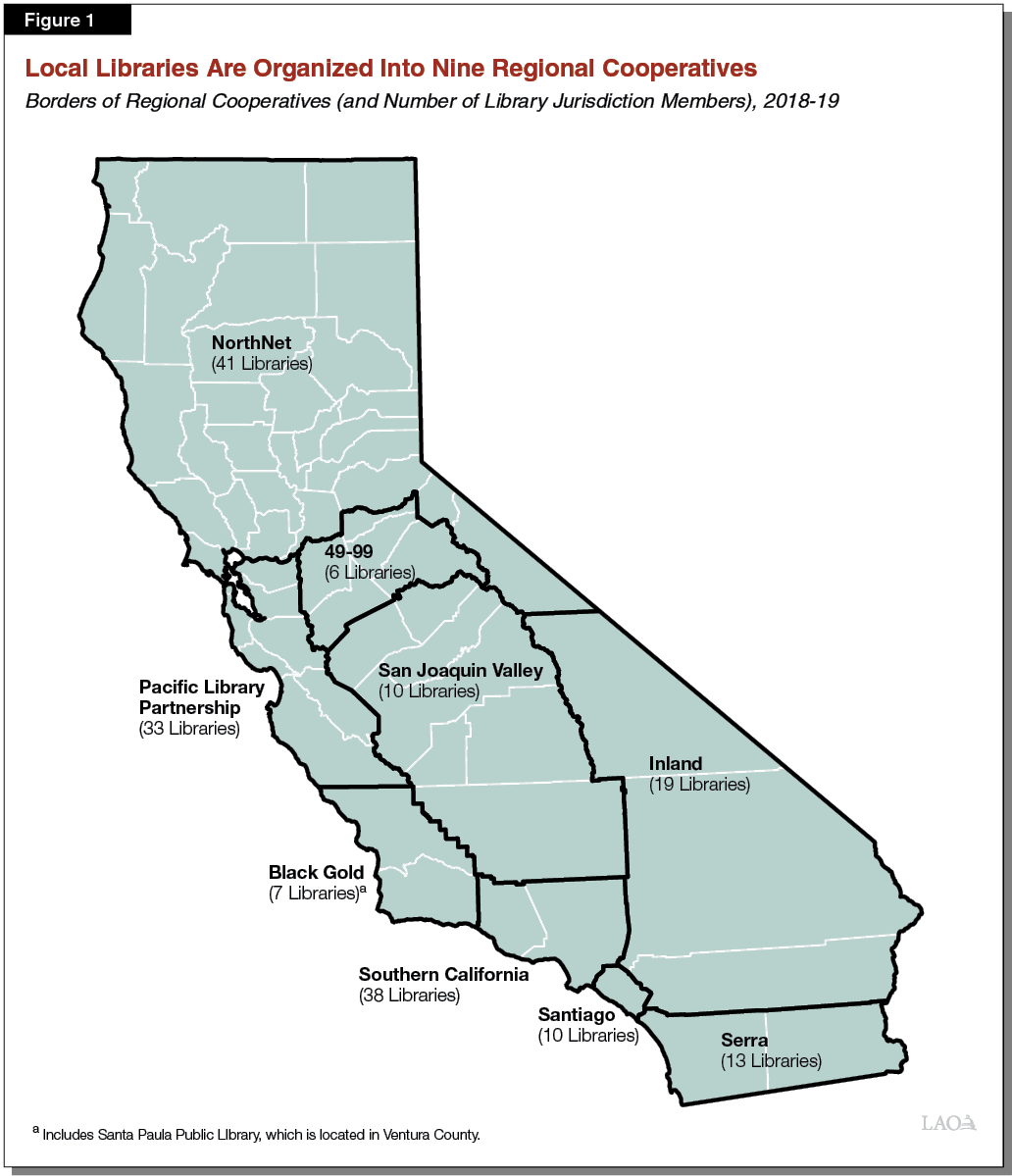

Resource Sharing Governed by Regional Cooperatives and Statewide Board. To implement CLSA, 177 of the state’s 185 library jurisdictions are organized into nine library cooperatives. (The remaining 8 library jurisdictions choose not participate in CLSA, likely because they believe more cost‑effective options exist for giving their patrons access to materials.) The nine cooperatives provide two key services for member libraries: (1) they foster communication between member libraries by supporting video conferencing, conference calls, and other platforms; and (2) they fund the cost to transport and deliver books and other resources between member libraries. The cooperatives are overseen by the State Library and California Library Services Board. Since 2016‑17, the state has provided $3.6 million ongoing General Fund for CLSA, as well as one‑time funding for various special initiatives. Figure 1 shows a map of the current regional library cooperatives.

Federal Government Funds Local Libraries Through the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). The federal LSTA program has a broader scope than CLSA. It provides grants for coordination and resource sharing, as well as promoting literacy and lifelong learning, professional development, and resource preservation. To receive federal funding, the California State Librarian and the California Library Services Board develop a five‑year LSTA spending plan. Since 2015‑16, the state has been receiving $11.3 million annually in LSTA funds, with the funds designated for various local library initiatives.

Interlibrary Loans

Patrons Can Request Books From Another Library. Through interlibrary loans, a patron in one local library jurisdiction can request a book or other print resource from a library in another jurisdiction. Historically, interlibrary loans have been one of the primary ways libraries with fewer resources have met patron demands. According to the State Library, local libraries in California loaned out 3.5 million books and resources in 2016‑17.

Most Libraries Use International Nonprofit Organization for Loan Transactions. To provide outside library resources to patrons, most libraries in California are members of an international nonprofit cooperative known as the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). Under traditional interlibrary loans, staff at a local library searches for a requested book through OCLC’s library catalogue. Staff then submit an electronic request through OCLC’s online platform to borrow the book. If a library is willing to loan the book, the lending library then arranges for delivery either through the mail or a courier service. According to staff at the State Library, the time from requesting a book from another library to receiving it can range from two to four weeks. When the patron is finished with the book, the borrowing library returns it.

State No Longer Explicitly Funds Interlibrary Loans, Though Some CLSA Funds Available for Delivery Costs. Prior to 2011‑12, the bulk of state funds for resource sharing was to reimburse local libraries in the state that were “net lenders” (that is, libraries that loaned more resources than they borrowed). Due to the state’s poor budget condition, the state eliminated funding for interlibrary loans in 2011‑12. Though the state no longer explicitly funds interlibrary loans, the state’s nine cooperatives use a significant portion of their current ongoing CLSA allocations to transport books and materials between member libraries.

Other Costs Funded From Local Resources and Patrons. Though some state funding is available to cover delivery costs, historically libraries have had to cover a portion of interlibrary loan costs using their local resources. For example, libraries must pay annual membership fees to participate in OCLC. Libraries are also responsible for paying their staff, including the staff time taken to process loan requests. According to staff at the State Library, libraries typically shift a portion of these costs onto patrons by charging certain service fees.

Zip Books

Instead of Borrowing a Book, a Library Can Purchase It Through Amazon. The Zip Books program began as an alternative to interlibrary loans for local libraries in rural areas where delivery might be especially expensive. Under the Zip Books program, patrons may request books that libraries purchase through Amazon. In these cases, Amazon delivers the books directly to the patron. After completing a book, a patron gives it to the library. The library can either keep the book, give it to another library, or sell it. The program began as a pilot in 2011 in Butte County (using federal LSTA funds) but has since expanded. According to staff at the State Library, 68 library jurisdictions (37 percent) currently participate in the program.

Book Purchases Covered From Federal and State Funding. Under the program, local libraries establish a line of credit with Amazon to purchase books. The State Library then pays the associated bills using federal and state funds. From 2011‑12 through 2017‑18, the program received a total of $1.7 million in federal LSTA funds. In 2016‑17, the California Library Services Board decided to expand the program—providing it with $1 million in one‑time state CLSA funds. The State Librarian tasked NorthNet, the state’s northern‑most cooperative, with managing these funds. In 2018‑19, no federal LSTA funding was designated for the program, but the state provided another $1 million one‑time CLSA funds for additional book purchases. NorthNet has retained about 10 percent of the one‑time CLSA funds for its associated administrative costs.

Other Costs Supported by Library Budgets. While the state covers the bulk of Zip Book costs, local libraries are responsible for covering certain remaining costs from their local resources. For example, libraries pay an annual Amazon membership fee, currently $119. The membership fee grants libraries access to Amazon purchases and also covers the cost of delivery in most cases. In addition, as is the case with interlibrary loans, libraries are responsible for paying staff time devoted to processing Zip Book requests.

Proposal

Provides $1 Million One‑Time General Fund for Zip Books Program. The proposal would provide a third year of one‑time state funding through CLSA for the program. According to the administration, $900,000 would be used for purchasing an estimated 60,000 books. The book purchases would be on behalf of patrons at the existing 68 library jurisdictions participating in the program. In addition, the administration submitted a list of another 29 library jurisdictions that it believes could potentially begin participating in the program in 2019‑20. The remaining $100,000 would cover NorthNet’s administrative costs.

Assessment

Administration Cites Two Key Statewide Benefits of Zip Books Program. First, the administration notes that Zip Books is less time‑consuming for library staff to process than traditional interlibrary loans. According to an independent 2016 evaluation of the Zip Books pilot, staff takes around 22 minutes to process a Zip Books request, compared to 78 minutes for an interlibrary loan request. According to the administration, these time savings reduce staff costs from $33 for each interlibrary loan transaction to $9.50 for each Zip Book transaction. The administration concludes from this information that Zip Books is a less expensive approach for facilitating access to books. Second, the administration believes that Zip Books provide patrons of rural libraries improved access to resources. As discussed below, we have concerns with both the administration’s fiscal analysis and overall Zip Books proposal.

Generating Savings Is a Poor Rationale for More State Funding. The administration’s fiscal analysis has two notable shortcomings. First, the administration’s analysis focuses on only one factor—staff time—while omitting other key cost considerations—notably, the cost of books, delivery, and operating fees (such as annual OCLC or Amazon membership fees). The cost to purchase books is particularly important when comparing resource sharing options, as this cost is avoided under traditional interlibrary loans. Because the administration has not provided the data required to do a complete cost‑benefit analysis, the Legislature cannot yet determine if Zip Books is more cost‑effective than other resource‑sharing options. Second, even if a comprehensive fiscal analysis were to demonstrate savings associated with Zip Books, local libraries presumably could use the savings freed up from reducing reliance on existing resource‑sharing mechanisms to fund an expansion of Zip Books. In this case, libraries would not need additional state General Fund support.

Administration’s Fiscal Analysis Omits Other Options Available to Reduce Delivery Costs. The administration’s analysis also compares Zip Books only with interlibrary loans. Libraries, however, have other options for resource sharing. For example, some local libraries are connected to regional online catalogues and courier services that can result in lower delivery costs. In addition, some library cooperatives are expanding the use of electronic resources. Though requiring digital readers, these electronic materials can be sent to member libraries without the expense of transporting physical copies. We believe any proposal to reduce resource‑sharing costs and expand access to rural libraries should examine these alternatives.

Proposal Does Not Consider Local Resources Available to Cover Book Purchases. The administration also did not provide an analysis of available local resources to cover Zip Book costs. We believe these resources should be a key consideration, as most libraries regularly purchase print and electronic materials as part of their operating budgets. In 2016‑17 (the most recent data available), libraries that currently participate in the Zip Books program spent a combined $19 million on new materials, including $10 million specifically on print materials. These ongoing amounts are much larger than the one‑time General Fund appropriation proposed by the administration.

Zip Books Might Benefit Rural Communities, but Further Analysis Is Needed. Though the administration indicates that Zip Books could improve access to books and resources for patrons in rural communities, it has not analyzed which rural libraries currently are unable to fulfill patrons’ book requests due to insufficient resources and high delivery costs. Without this analysis, the Legislature lacks sufficient information to assess the extent of the problem, whether the current Zip Books program is adequately targeted, or whether adding more jurisdictions to the program is warranted.

Expenditure Data Also Has Not Yet Been Provided for the Program. As part of our review of the Governor’s proposal, we requested the State Library provide program expenditures for the past few years. This data request had two main purposes: (1) to confirm that the program has spent all of its previous state appropriations, and (2) to gauge whether the administration’s spending projections for 2019‑20 (60,000 book purchases at an average cost of $15) are reasonable. To date, neither the State Library nor the administration has been able to provide this information.

Recommendation

Task Administration With Preparing a More Fully Developed Proposal. Given the Governor’s current proposal is not fully developed, the Legislature could invite the administration to submit an improved proposal next January, as part of the 2020‑21 Governor’s budget. Alternatively, if the Legislature still desires to provide $1 million in one‑time state funding for local library resource sharing in 2019‑20, it could condition release of the funds on the administration, in consultation with the State Librarian, submitting an improved plan by November 1, 2019. To ensure legislative oversight, provisional budget language could direct the Department of Finance to provide 30‑day notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee prior to releasing the funds. Under either of these approaches, we recommend the improved plan:

- Identify specific resource challenges facing specific rural libraries.

- Include a fiscal analysis comparing all available resource‑sharing options for these libraries.

- Provide at least three years of past funding and spending data for the program, accounting for all applicable fund sources.

- Set forth expectations for improved access and explain how progress toward meeting those expectations would be tracked over the next few years.

Lunch at the Library

In this part of the brief, we analyze the Governor’s proposal for the Lunch at the Library program. We first provide relevant background, then describe the Governor’s proposal, assess the proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

In this section, we provide background on (1) the federal government’s summer meals program and (2) Lunch at the Library, which aims to increase library participation in the federal meals program.

Federal Summer Meal Programs

Longstanding Federal Program Subsidizes School Lunches for Students From Low‑Income Households. Established in 1946, the National School Lunch Program provides public school children free or reduced‑price lunches while they attend school. Under the program, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reimburses schools for providing meals that meet certain nutrition standards. To qualify for a subsidized lunch, a child’s household must meet certain income thresholds. To qualify for a free lunch, students must be from households that have incomes at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level ($27,014 for a family of three). To qualify for a reduced‑price lunch, students must be from households earning at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level ($38,443 for a family of three). In 2017‑18, public school districts, together with some private schools, operated the program, providing meals to a total of 3.7 million students (60 percent of all K‑12 students) in California.

Federal Programs Also Provide Children Free Meals in the Summer. To ensure low‑income students have access to nutritious meals during the summer when they are not enrolled in school, USDA also reimburses states for providing free summer meals. For school districts, the reimbursement rates for summer meals are the same as those provided during the school year. For summer‑only meal operators, reimbursements rates are slightly higher (with the higher rates likely intended to account for these operators’ higher administrative costs).

Summer Programs Have Three Key Differences From the National School Lunch Program. First, whereas only schools provide meals during the academic year, many more organizations—including local government agencies and nonprofit organizations—are eligible to provide summer meals. Second, students are not required to demonstrate eligibility to receive a summer meal. Instead, organizations can provide summer meals to any individual under the age of 18 at an eligible site. Eligible sites are those located in areas where at least 50 percent of students qualify for a free or reduced‑price lunch during the school year. Third, all meals provided at eligible sites are free.

Summer Program Received $46 Million Federal Funding in 2016‑17. Of this amount, $25 million covered meals provided by 351 school districts (roughly one‑third of all districts) at 2,390 sites, with $21 million covering meals provided by 199 local agencies, nonprofit organizations, and other providers at 2,571 sites. The state provided a small General Fund match ($2 million) to the federal funding, which increased the reimbursement rate for each summer meal slightly. Altogether, 16.2 million summer meals were provided in 2016‑17—an average of 419,00 meals per summer day.

Participation in Summer Program Is Notably Lower Than in Fall Through Spring. Because students are required to attend school during the academic year, virtually all eligible students receive subsidized meals during that period. By contrast, only a portion of eligible students are accessing free meals during the summer. In the summer of 2017, average daily participation in California’s summer program was less than 20 percent of daily participation during the 2016‑17 academic year. According to the Food Research and Action Center (a nonprofit organization), participation is even lower nationally, with average summer participation 15 percent of participation during the fall through spring. Experts have suggested several reasons for the lower participation, including lack of awareness of the summer program, limited number of sites in certain areas, and lack of sufficient incentive for students to travel to the nearest summer meal site.

Lunch at the Library

Lunch at the Library Program Aims to Increase Local Library Involvement With Summer Meal Program. Initiated in 2013, Lunch at the Library was established as a partnership with the California Library Association (an association of California local libraries) and the California Summer Meal Coalition (a multisector group dedicated to increasing summer meal participation). The program’s two main goals are increasing the number of libraries serving as summer meal sites and increasing summer enrichment opportunities for students. Lunch at the Library is currently administered by two California Library Association managers, with the managers devoting 30 percent of their time to the program. In addition, one staff person at the State Library monitors the grant and oversees the program.

Program Primarily Supports Start‑Up Costs, Outreach, and Enrichment Services. Because the federal summer meal program supports the cost of providing meals to students, Lunch at the Library focuses on other services and initiatives that support summer meal sites. Specifically, the program funds: (1) training and technical support to library staff to help them establish their libraries as summer meal sites; (2) library learning, enrichment, and youth development opportunities that wrap around the summer meal program; and (3) library resources at other community summer meal sites.

Program Funded Through Mix of One‑Time Fund Sources. According to program staff, Lunch at the Library was initially funded with private grants. Over the past three years, the program also has received $241,500 in total one‑time federal LSTA funds. In 2018‑19, the state provided $1 million one‑time General Fund for the program.

Program Currently Has Relatively Small Impact. During the summer of 2018, the program reported providing 287,769 summer meals and snacks at 191 sites. These meals reflect a tiny share of free summer meals provided in California.

Proposal

Proposes $1 Million One‑Time General Fund for Lunch at the Library. As Figure 2 shows, about two‑thirds of the proposed amount would support grants for program start‑up costs at new library sites and summer enrichment programs. The remaining funds would support outreach activities, including program staff time and travel to conferences. Program staff anticipate these activities would add around 25 new Lunch at the Library sites. Staff anticipate increasing the number of summer meals served through the Lunch at the Library program by 10 percent to 15 percent (adding an estimated roughly 30,000 to 40,000 meals).

Figure 2

Lunch at the Library Budget Proposal

One‑Time State General Fund, 2019‑20 (In Thousands)

|

Proposed Expenditures |

Amount |

|

Local library grantsa |

$675 |

|

Program staff |

210 |

|

Conference travel and supplies |

25 |

|

Overhead |

90 |

|

Total |

$1,000 |

|

aFor start‑up costs at new library sites and enrichment programs. |

|

Assessment

Summer Food Insecurity Is a Salient Issue. According to Feeding America, a nonprofit organization that annually analyzes federal census data, 19 percent of Californians under the age of 18 reported being food insecure in 2016. Food insecurity rates tend to be higher in inland counties than the coast, with rates ranging from 33 percent in Imperial County to 13 percent in Alameda County. While these data do not indicate what time of year children experience food insecurity, food insecurity might increase during the summer months when school is not in session.

Focusing Efforts Solely on Adding Library Sites Is a Very Narrow Approach to Increasing Participation. Though summer meal programs likely are undersubscribed for several reasons, the Governor focuses on addressing only one factor—insufficient sites. Other factors, however, such as lack of awareness and outreach, could be equally important contributors to low summer participation. Even were the administration to demonstrate that adding more sites would be the most cost‑effective approach for increasing summer participation, the state would be limiting potential success of the initiative by focusing solely on library sites. Presumably, the optimal sites to deliver summer meals vary depending on the local community.

Likely Negligible Impact on Student Outcomes. One expressed objective of more summer enrichment programs is to improve student learning. The state, however, already provides schools with tens of billions of dollars on an ongoing basis to improve student outcomes. The added benefit of expanding summer reading programs at libraries using some portion of $1 million in one‑time funding is likely negligible.

Recommendation

Direct State Library, in Consultation With the California Department of Education, to Submit Improved Proposal. If the Legislature desires to address child food insecurity in expanded ways, with a particular focus on addressing hunger during the summer months, we recommend it take a somewhat different approach than the administration. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct the State Library to work in coordination with the California Department of Education to develop an improved plan. The improved plan could be submitted for consideration next January, as part of the 2020‑21 Governor’s budget. Alternatively, the Legislature could provide $1 million in one‑time state funding in 2019‑20 but condition release of the funds on receipt of an improved plan. Under this second option, provisional budget language could require the administration to submit a revised plan to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee by November 1, 2019, with a 30‑day review period. Whether submitted this year or next year, we recommend the improved plan:

- Include a comparative analysis of different strategies to improve summer meal participation, such as comparing a public awareness campaign with start‑up funding for a new summer reading enrichment program.

- Prioritize funds for areas of the state with higher food insecurity or lower summer meal participation than the statewide average.

- If applicable, invite participation from all types of eligible summer meal operators, including both libraries and schools, in the identified target areas of the state.

- Set expectations for what is to be achieved with the additional state funding and explain how results will be measured, tracked, and reported.

These improvements to the plan would be intended to ensure that state funding is well aligned with a clear state objective and is being used in a transparent and effective manner.