LAO Contacts

April 25, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Student Food and Housing Insecurity

at the University of California

Introduction

The Governor proposes to provide the University of California (UC) with ongoing funding to address student food and housing insecurity. UC indicates it would use the proposed funds either to augment student financial aid or support specific food and housing initiatives. In this brief, we provide background, then describe the Governor’s proposal. Next, we offer issues to consider and provide associated recommendations.

Background

In this section, we first provide background on financial aid available to UC students, then provide background on food and housing insecurity among UC students and UC’s efforts to respond.

Financial Aid

To Attend College, Students Face Tuition and Nontuition Costs. To attend UC, all students are charged tuition and other fees. In addition, students must cover the cost of books, supplies, food, housing, transportation, and health care. To estimate the overall cost of attendance (tuition and nontuition costs), UC periodically surveys its students. In 2018‑19, UC students living off campus spent on average $32,468, with $14,015 spent on tuition and fees and the remaining $18,453 spent on living costs. Students living on campus pay on average more (a total of $35,283) and students living with their parents on average pay less ($26,504). The difference is primarily due to housing costs, with students living on campus typically facing higher housing costs and students living with their parents typically facing lower housing costs.

Financial Aid Helps Low‑Income Students Cover Their College Costs. Most of the state’s undergraduate financial aid programs are need based, meaning that students qualify for aid based on their household’s financial resources and the cost to attend school. Students in California who qualify for need‑based aid often receive a mix of federal and state grants to cover costs, including the federal Pell Grant and the state Cal Grant. In addition, each public segment and many private schools offer their own aid programs that either supplement federal and state programs or support additional students.

Financial Need Is Determined by Cost of Attendance and Expected Family Contribution. Across the country, students from low‑income households qualify for financial aid based on a federal formula. The formula estimates a family’s expected college contribution based primarily on family income and size. A student’s financial need is then defined as the total cost of attendance less a family’s expected contribution. Federal, state, and campus financial aid programs each meet a portion of a student’s financial need.

UC’s Aid Focuses on Covering Cost of Attendance After Family and Student Contribution. UC first determines students’ cost of attendance based on the average cost by type of living arrangement (off campus, on campus, or with family). Then, UC expects households to contribute toward this cost based on their federal expected family contribution. In addition to expecting families to contribute, UC expects all students to support a portion of their costs through work and loans. This student expectation changes each year and is intended to reflect a reasonable amount of working and borrowing. In 2018‑19, the student work and loan expectation is $10,000 per student. The remaining cost of attendance is covered through financial aid.

UC Funds A Portion of Aid Primarily With Tuition and Fee Revenue. State and federal aid programs, including the Cal Grant and Pell Grant, do not provide enough aid to cover all student financial need at UC. To cover remaining financial need, UC has its own aid program. It funds the program using a portion of student tuition and fee revenue. In years when the cost of the attendance grows faster than growth in aid programs, UC increases the student work and loan expectation. UC believes its student work and loan expectation has remained manageable over time.

Student Food and Housing Insecurity

Food Insecurity Defined by Federal Government, but No Standard Definition of Housing Insecurity. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines “low food security” to mean an individual has a reduced quality or desirability of diet and “very low food security” to mean an individual that experiences multiple disruptions of eating patterns and food intake. To measure the incidence of food insecurity, the department has developed a six‑question survey. In contrast to food insecurity, the federal government has no one methodology for measuring housing insecurity. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, however, periodically surveys the incidence of individuals who experience homelessness.

UC Recently Completed Two Studies of Food and Housing Insecurity Among Its Students. The first survey, administered in 2015, focused exclusively on food insecurity. Using the six questions developed by USDA, UC surveyed 66,000 of its undergraduate and graduate students. Of those surveyed, 14 percent responded. Beginning in 2016, UC incorporated questions regarding both food and housing insecurity into its biennial undergraduate and graduate student experience survey. This survey is administered to all students and tends to have higher response rates (about one‑third of students respond).

Notable Proportion of UC Students Report Food and Housing Insecurity. Based on the 2016 survey, UC reports that 44 percent of undergraduate students and 26 percent of graduate students experience food insecurity. The results are roughly comparable to the 2015 survey. According to UC, about half of students reporting food insecurity experience reduced quality or desirability of diet and the other half report experiencing multiple eating disruptions. About 5 percent of undergraduate and graduate students report experiencing homelessness, but the university indicates its definition of homelessness has not been validated as an accurate measure. UC’s definition encompasses living situations ranging from couch surfing at a friend’s residence to living on the street.

University Has Implemented Several Initiatives to Address Food Insecurity. Since 2015‑16, UC campuses have received $7.8 million in one‑time funding to address student hunger, including $4 million from the state General Fund and $3.8 million from discretionary university funds. Campuses have used these funds to support a variety of activities, including: (1) developing and expanding campus food pantries, (2) establishing “basic needs centers” that provide students information on supporting food and housing costs, (3) creating programs for on‑campus students to donate unused meal allowances to food pantries, (4) providing financial literacy workshops for students, and (5) hiring on‑campus coordinators to help enroll more students in CalFresh (the state’s food benefit program).

Proposal

Proposes $15 Million Ongoing General Fund to Address Food and Housing Insecurity at UC. The amount proposed by the Governor corresponds to a budget request made by the UC Regents. The budget bill specifies that the funds are to address student food and housing insecurity. In discussions with our office, the Department of Finance indicates UC would have flexibility to determine how to use the proposed funds as well as how to allocate the funds among its campuses.

UC Indicates Initial Plan Was to Use Funds Entirely for Financial Aid. According to UC, its original $15 million request was intended to supplement student financial aid. Staff at the UC Office of the President estimated that the student work and loan expectation would otherwise rise from $10,000 in 2018‑19 to $10,500 in 2019‑20, and that the proposed funding would reduce the 2019‑20 expectation to $10,350. Staff emphasized that these estimates are preliminary and subject to a number of factors that could change before the start of the academic year.

UC Is Revisiting Its Initial Plan, May Use All or a Portion of Funds for Other Initiatives. According to UC staff, student groups have requested that the proposed funding be used to support specific food and housing initiatives. During a March meeting of the UC Board of Regents, the Office of the President indicated that campuses likely would have flexibility in how they could use the funds.

Issues for Consideration

The Governor’s proposal raises at least three issues for the Legislature to consider: (1) the underlying incidence and causes of food and housing insecurity, (2) the interaction between student financial aid and public assistance programs that support food and housing costs, and (3) inequities in funding for student food and housing across the state’s higher education segments. We discuss each issue below.

Understanding the Causes of Food and Housing Insecurity

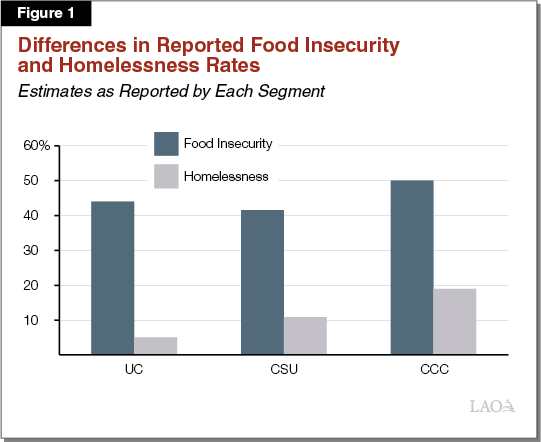

Incidence of Food Insecurity and Homelessness at UC Is Comparable to Other Higher Education Segments but Much Higher Than California Households. The California State University (CSU) and the California Community Colleges (CCC) also have studied food insecurity and homelessness among their students. The CSU and CCC studies had much lower survey response rates—around 5 percent for each study—than the UC studies. Such low rates could result in responses not being representative of all CSU and CCC students. Despite this notable caveat, these segments report that their food insecurity and homelessness rates are comparable to or higher than the rates at UC (Figure 1). The reported rates among the three segments are far greater than the incidence among California’s population as a whole. According to recent federal survey data, 11 percent of California households experience food insecurity and less than 1 percent of Californians are homeless.

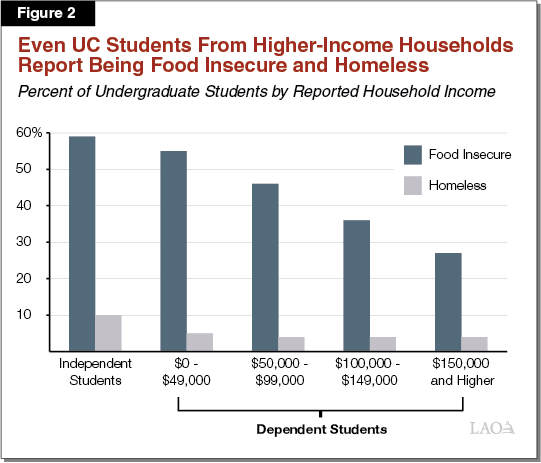

Food Insecurity Rates at UC Defy Expectations. Figure 2 shows estimated food insecurity at UC by undergraduate household income. With regard to lower‑income households, the high rates of reported food insecurity are surprising because UC offers comprehensive student financial aid that factors in food and other living costs. That one‑quarter of students from higher‑income households (earning $150,000 or more) report food insecurity is also surprising given the significant resources these households have to cover food and other living costs.

Studies Have Not Yet Pinpointed Key Causes of Student Food and Housing Insecurity. Students may experience food and housing insecurity for many possible reasons. Lack for funds, lack of awareness of aid opportunities, poor spending choices, a lack of familiarity or aversion to borrowing, difficulty finding a part‑time job, or unique circumstances (perhaps relating to family or health) might contribute to food and housing insecurity. The largest contributors likely vary depending upon student characteristics (including family income). Understanding the root causes of food and housing insecurity for specific student groups is critical if the state is to respond cost‑effectively and strategically. Depending upon the key causes, the state could want to consider providing additional financial aid for living costs; hiring additional financial aid, financial literacy, or job counselors; or funding on‑campus food pantries and emergency housing options.

Addressing Living Costs Through Financial Aid and Public Assistance

Certain College Students Can Qualify for CalFresh Benefits. Under the CalFresh program, eligible households receive an allotment of funds each month that they can use to purchase food. The monthly benefit depends on a household’s size. For example, the maximum monthly allotment begins at $192 for an individual and increases to $642 for a household of four. To qualify for CalFresh benefits, a household’s income cannot exceed 130 percent of the federal poverty level, among other requirements. According to USDA, college students generally must be enrolled less than half time to qualify for CalFresh benefits. Full‑time students can still qualify for CalFresh if they work at least 20 hours per week, have children, have a disability, or are already receiving other forms of public assistance.

Some Eligible Students Likely Are Not Receiving CalFresh Benefits. No data exist on the number of students at each segment who are eligible to receive CalFresh benefits. Some data suggest, however, that a portion of eligible students may not be receiving benefits. In a recent report, the Government Accountability Office estimated that 57 percent of income‑eligible students nationally did not receive federal food benefits. While no California‑specific data exist, recent data at UC suggest some UC students are eligible to receive food benefits. According to UC, between January and June 2018, campus staff helped enroll 10,376 additional students into the CalFresh program.

State Has Sought to Increase Coordination Between Higher Education and Human Services. As part of the 2018‑19 budget, trailer legislation directed the California Department of Social Services to convene a working group comprised of representatives from each of the three public higher education segments and local welfare providers. The purpose of the group is to improve coordination and better deliver benefits to college students. According to staff at the department, two stakeholder meetings are scheduled to occur before June 30, 2019. At the time of this analysis, no further information was available as to the content or results of the meetings.

Addressing Inequities in Funding for Living Costs

UC Students Have More of Their Living Costs Covered On Average Than Students at Other Segments. In contrast to UC, CSU and CCC aid programs focus primarily on tuition costs and offer less for living costs. This difference creates inequities among the state’s three higher education segments. A recent analysis conducted by The Institute for College Access and Success found that, holding family size and household income constant, off‑campus students attending UC face lower costs after accounting for their aid packages than similar students at the nearest CSU and CCC campus. Students facing higher costs tend to rely more on their households for support, work more hours, take on additional borrowing, or find ways to reduce their spending (for example, by sharing an apartment with more roommates).

Governor’s Proposals Would Exacerbate Inequities. Though UC students already receive more aid for living costs than CSU and CCC students, the Governor proposes an ongoing augmentation only for UC students. By comparison, the Governor proposes one‑time funding to CSU ($15 million) and no funding to CCC for their food and housing initiatives. According to the Department of Finance, the different approaches reflect budget requests made by each segment. They do not reflect a strategic statewide response to the issues at hand.

Recommendations

Gain Greater Understanding of Incidence and Causes of Student Hunger and Homelessness. The studies to date on student food and housing insecurity leave many important questions unanswered. To gain a better understanding of underlying issues and potential policy responses, we recommend the Legislature fund a one‑time study involving students across the higher education segments. The study could examine why hunger and homelessness rates are so much higher for college students than the overall California population. It also could examine whether food and housing insecurity is more acute at certain segments or if root issues vary among the segments. Additionally, the study could entail several focus groups (differing by significant socioeconomic factors) to discuss students’ specific food and housing challenges, their existing approaches to addressing those challenges, and other feasible approaches that might be more effective. We believe such a study likely could be undertaken for less than $500,000 in one‑time funding.

Use Results of Study to Inform Fiscal and Policy Responses. We recommend requiring the results of this study to be released by October 2020—in time to inform 2021‑22 budget deliberations. The state could use the results to help it decide whether providing additional financial aid, funding financial literacy or nutrition courses, hiring more counselors, or supporting specific emergency food and housing initiatives would best target the identified causes of student food and housing insecurity. The study also could help the state decide how to allocate any additional funding across the higher education segments.

Further Examine Role of Public Assistance Programs in Covering Students’ Living Costs. In addition to studying underlying food and housing insecurity issues, we recommend the Legislature continue efforts to understand how CalFresh and other public assistance programs could support students’ living costs. To this end, we recommend the Legislature direct the segments to continue working with the California Department of Social Services to estimate how many students are eligible to receive CalFresh benefits; how many students already receive those benefits; and how best to reach eligible, unserved students. We recommend this information be provided to the Legislature no later than November 1, 2019—in time to inform next year’s budget deliberations. We recommend the Legislature also direct the segments to report on the outcomes of their 2018‑19 stakeholder meetings, also no later than November 1, 2019. On a parallel track, the state could undertake a similar process of coordination and analysis relating to housing assistance programs for which students might qualify.

While Awaiting Results of Studies, One‑Time Funding Could Help Sustain Existing Initiatives. Given the uncertainty behind the underlying causes of student food insecurity and homelessness, we believe funding associated ongoing initiatives is premature. We believe waiting for the results of the studies just mentioned would help the Legislature maximize the effectiveness of state funding. Nonetheless, were the Legislature interested in sustaining existing campus initiatives in the meantime, it could provide one‑time funding for these purposes in 2019‑20. As context, the state provided $1.5 million in one‑time funding last year for food insecurity initiatives at UC.

Summary of Recommendations

- Provide up to $500,000 in one‑time funding for a study on the incidence and causes of student food and housing insecurity across the higher education segments. Require results of the study to be released by October 2020—in time to inform 2021‑22 budget deliberations.

- Direct the three public segments to continue working with the Department of Social Services to assess the effectiveness of CalFresh in addressing student food insecurity. Require associated information be provided to the Legislature no later than November 1, 2019—in time to inform 2020‑21 budget deliberations.

- Direct the segments to share what they learned from their 2018‑19 workgroup meetings. Require information be provided to the Legislature no later than November 1, 2019.

- Consider directing the higher education segments to work with other state agencies to assess the extent to which housing assistance programs are benefiting college students.

- Consider providing one‑time funding to help sustain existing food and housing initiatives at the segments in 2019‑20. The Legislature provided $1.5 million to UC in 2018‑19 for such initiatives.