LAO Contacts

April 30, 2019

Evaluation of Cal Grant C Program

Executive Summary

In this report, we evaluate the Cal Grant C program, as required by statute, and make a recommendation regarding whether the state should maintain it. Below, we share the highlights of the report.

Background

Cal Grants Are State’s Primary Form of Financial Aid. The state offers three types of Cal Grant awards (A, B, and C) that vary somewhat in their eligibility requirements and award amounts. Cal Grant A and B are the most common award types, together accounting for over 99 percent of annual Cal Grant spending. Students must be enrolled in education programs at least two years in length to qualify for Cal Grant A and at least one year in length to qualify for Cal Grant B. Recent high school graduates and relatively young transfer students are entitled to a Cal Grant A or B award if they meet certain financial and academic requirements. Older students interested in Cal Grant A or B must apply for a limited number of competitive awards (up to 25,750 each year). The smaller Cal Grant C program has different rules and requirements, as described below.

Cal Grant C Program Provides Financial Aid Aimed at Career Technical Education (CTE) Students. Postsecondary CTE is generally designed to prepare students for specific occupations. While all Cal Grant award types are open to CTE students, the Cal Grant C award is specifically targeted for them. To qualify for a Cal Grant C award, students must be enrolled in CTE programs of four months to two years in length. State law authorizes up to 7,761 new Cal Grant C awards each year. At the California Community Colleges (CCC), Cal Grant C recipients receive up to $1,094 annually for nontuition costs, in addition to having all their tuition costs waived through a separate program (worth up to $1,380 for a full‑time student). At private colleges, Cal Grant C recipients receive up to $3,009 annually for tuition and nontuition costs.

Legislature Recently Enacted Changes to Better Align Cal Grant C Program With Workforce Needs. Chapter 627 of 2011 (SB 451, Price) and Chapter 692 of 2014 (SB 1028, Jackson) modified Cal Grant C eligibility criteria. Under the new rules, the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) is to prioritize Cal Grant C awards for applicants pursuing occupations that meet strategic workforce needs, with greater consideration given to disadvantaged applicants. (The current list of prioritized occupations includes 30 jobs ranging from aircraft mechanics to website developers.) State law directs our office to prepare an interim and final report on the impact of these new rules. We released the interim report in 2015 (Review of Recent Changes to the Cal Grant C Program), and this report fulfills the final requirement.

Assessment

Recent Changes Have Not Significantly Improved Workforce Alignment. Few students apply for Cal Grant C awards. As a result, all eligible applicants are offered awards and CSAC has not needed to use the new prioritization criteria. Notably, nearly two‑thirds of Cal Grant C award offers go to applicants who indicate they intend to pursue a non‑prioritized occupation. Among Cal Grant C recipients at CCC, only two of the top ten programs of study completed by the most recent cohorts align with a prioritized occupation. In addition, some Cal Grant C recipients are completing certificates or degrees in non‑CTE fields (such as the humanities). The available data on Cal Grant C recipients’ employment outcomes suggests limited success. Three years after first receiving a Cal Grant C award, some recipients are employed in high‑wage settings such as hospitals, but others continue to work in lower‑wage settings such as restaurants and grocery stores.

Cal Grant C Program Requirements Add Complexity to Financial Aid System. While applicants for all types of Cal Grant awards must submit a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or California Dream Act Application, applicants for Cal Grant C awards must also submit a supplemental form. The supplemental form asks applicants to report their occupational goal, among other information CSAC may use in the selection process. This form likely decreases application rates, as students may not understand the importance of the form, may be deterred by the additional paperwork, or may be unsure how to answer certain questions on the form. The Cal Grant C program’s eligibility requirements also create administrative challenges for campus financial aid staff, who are required to verify that recipients are enrolled in a CTE program before disbursing their awards. These requirements run counter to the Legislature’s recent interest in simplifying Cal Grant rules to help both students and staff navigate the financial aid system more easily.

Recommendation

Recommend Phasing Out Cal Grant C Awards and Redirecting Funds Toward Cal Grant Competitive Awards. Given its shortcomings in meeting strategic workforce needs and the complexity it adds to the state’s financial aid system, we recommend phasing out the Cal Grant C program and redirecting the funds to a larger existing financial aid program that is also open to CTE students—the Cal Grant competitive program. We recommend beginning the phase out in 2020‑21 and eventually redirecting all Cal Grant C funding (an estimated $10.6 million) into the competitive program. The redirection would allow the state to raise the cap on new competitive awards by roughly 2,000, bringing the total number of new competitive awards offered annually to 27,750. Relative to Cal Grant C awards, competitive awards have more unmet demand, a simpler application process, and a larger award amount per student.

Consider Lowering the Cal Grant B Program Length Requirement. If the Legislature were to phase out the Cal Grant C program, it may wish to retain Cal Grant eligibility for students in shorter CTE programs by reducing the minimum program length for Cal Grant B awards from one year to four months. We recommend the Legislature weigh the associated trade‑offs carefully, as some research suggests students completing shorter CTE programs tend to experience lower wage increases than students completing longer CTE programs.

Introduction

The Cal Grant C program provides financial aid to students pursuing postsecondary career technical education (CTE). Chapter 627 of 2011 (SB 451, Price) and Chapter 692 of 2014 (SB 1028, Jackson) modified Cal Grant C eligibility criteria. Specifically, these laws require the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) to prioritize Cal Grant C awards for applicants pursuing occupations that meet strategic workforce needs, with greater consideration given to disadvantaged applicants. The authorizing legislation directed our office to prepare an interim report on the impact of the new rules, and Chapter 23 of 2017 (SB 85, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) directed our office to submit a final report this April. Our office released the interim report in 2015, and this report is the final one.

We begin the report by providing background. Next, we describe our key findings, including trends related to Cal Grant C recipients’ demographics, occupational goals, and employment outcomes. Then, we provide an overall assessment of the program and make associated recommendations.

Background

In this section, we provide background on CTE and the financial aid programs available for students enrolled in CTE programs.

Career Technical Education

CTE Provides Training in a Broad Range of Occupations. CTE programs span a wide range of fields, including health care, information technology, and manufacturing. (Other common terms for CTE include vocational training, occupational or technical training, and workforce training and education.) CTE programs generally are designed to train students in occupation‑specific skills. Programs vary in length from a few months to two years. Shorter programs tend to culminate in certificates, whereas longer programs typically culminate in associate degrees. Both shorter and longer programs may lead to industry‑recognized certifications. (Bachelor’s and graduate degrees are generally not considered CTE.)

California Community Colleges (CCC) and Private Colleges Provide CTE. Community colleges, private for‑profit colleges, and certain private nonprofit colleges offer postsecondary CTE programs. Importantly, other educational institutions offer instruction that can lead into or extend from a postsecondary CTE program. Many high schools in California offer CTE programs that lead to more advanced CTE programs offered by community colleges, and some community college CTE programs lead to more advanced education programs at universities. For example, a high school senior might take health‑related coursework that is articulated with community college coursework culminating in an associate’s degree in licensed vocational nursing, which could in turn lead into a university program that grants a bachelor’s degree in registered nursing.

State Funds CTE Through a Number of Programs. Figure 1 shows the major sources of state funding for postsecondary CTE in 2018‑19. Traditionally, the state has funded CTE primarily through community college apportionments. The state supplements apportionments with categorical programs focused specifically on CTE. To improve the availability and quality of CTE, the state created several of the categorical programs shown in Figure 1 over the past ten years—the two largest new programs being the Adult Education Program and the Strong Workforce Program. Most recently, the state established a new online community college overseen by the CCC Board of Governors that will offer short‑term CTE programs for working adults starting in late 2019.

Figure 1

State Funds Several Postsecondary Career Technical Education (CTE) Programs

2018‑19 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Description |

Funding |

|

Apportionments for workforce education and training |

Provides funds to community college districts for credit and noncredit courses in CTE, basic skills, and English as a second language. |

$1,954a |

|

Adult Education Program |

Provides funds to 71 regional consortia of community colleges and adult schools (operated by school districts) to support programs across a range of instructional areas, including CTE. |

527 |

|

Strong Workforce Program |

Requires community colleges to coordinate their CTE activities within seven regional consortia and provides funds to expand programs aligned with regional priorities. |

248b |

|

Apprenticeship programs |

Supports the classroom instruction component of apprenticeships, which provide paid on‑the‑job training for workers in various trades. Also provides seed money to expand pre‑apprenticeships and apprenticeships in nontraditional fields. |

78 |

|

Economic and Workforce Development Program |

Funds positions for industry area experts within the community college system, as well as other initiatives intended to strengthen alignment between CTE programs and industry needs. |

23 |

|

Online community college |

Provides short‑term online programs for working adults. |

20c |

|

Nursing program support |

Supports efforts to increase program capacity and student success within community college nursing programs. |

13 |

|

Total |

$2,863 |

|

|

aAssumes community colleges spend 27 percent of apportionment funding on CTE, based on the share of full‑time equivalent students considered CTE. bReflects ongoing funding. The state also provided $2 million one time to expand certified nurse assistant programs. cReflects ongoing funding. The state also provided $100 million one time for start‑up costs. |

||

Financial Aid

Financial Aid Helps Students Pay College Costs. The federal government, state government, many higher education institutions, and some private organizations offer financial aid to students. Awards are based on students’ financial need and/or other student factors, such as academic merit, athletic talent, and military service. One common type of financial aid is gift aid, which refers to grants, scholarships, and tuition waivers that students do not have to pay back.

Cal Grants Are State’s Primary Form of Financial Aid. Cal Grants provide gift aid to students who meet financial, academic, and other eligibility requirements. In 2018‑19, the state provided $2.2 billion to fund an estimated 392,000 Cal Grants. To be considered for an award, students must file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or a California Dream Act application.

State Offers Several Types of Cal Grant Awards. The state funds three types of Cal Grant awards: Cal Grant A, B, and C. As Figure 2 shows, these awards have somewhat different eligibility requirements related to family income, grade point average (GPA), and program length. Regarding program length, students qualify for Cal Grant A awards if pursuing any educational program (including a CTE program) of at least two years in length, Cal Grant B awards if pursuing any educational program at least one year in length, and Cal Grant C awards if pursuing a CTE program at least four months in length. As Figure 3 shows, Cal Grant award amounts vary based on award type and segment of attendance.

Figure 2

Cal Grant Program Consists of Three Types of Awards

Eligibility Requirements by Award Type, 2018‑19

|

Award Type |

Income Level |

Minimum GPA |

Program of Study and Duration |

|

Cal Grant A |

Low or middle income |

3.0 HS GPA 2.4 CCC GPA |

Any program (including CTE) between two and four years long |

|

Cal Grant B |

Low income |

2.0 HS GPA 2.4 CCC GPA |

Any program (including CTE) between one and four years long |

|

Cal Grant C |

Low or middle income |

No minimum |

CTE programs between four months and two years long |

|

HS = high school; GPA = grade point average; and CTE = career technical education. |

|||

Figure 3

Cal Grant Award Amount Varies Across Segments

Maximum Annual Award for Full‑Time Student, 2018‑19

|

Award Type |

UC |

CSU |

CCC |

Nonprofit |

For‑Profit |

|

Cal Grant A |

|||||

|

Tuition award |

$12,570 |

$5,742 |

—a |

$9,084 |

$4,000b |

|

Nontuition award |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Cal Grant B |

|||||

|

Tuition award |

$12,570 |

$5,742 |

—a |

$9,084 |

$4,000b |

|

Nontuition award |

1,672 |

1,672 |

$1,672 |

1,672 |

1,672 |

|

Cal Grant C |

|||||

|

Tuition award |

— |

— |

—a |

$2,462 |

$2,462 |

|

Nontuition award |

— |

— |

$1,094 |

547 |

547 |

|

aFinancially‑needy CCC students have their tuition waived ($1,380 for a full‑time student). bReflects amount for schools that are not accredited by WASC. Students attending for‑profit WASC‑accredited schools may receive a Cal Grant of up to $8,056. WASC = Western Association of Schools and Colleges. |

|||||

Students May Qualify for Either Cal Grant Entitlement or Competitive Program. The entitlement program guarantees Cal Grant A or B awards to recent high school graduates, as well as students under age 28 who are transferring from a two‑year to a four‑year institution. The competitive program is designed for those students ineligible for entitlement awards—typically older students who have been out of school for at a least a few years. Although roughly 300,000 applicants are eligible for these awards annually, state law authorizes only 25,750 new awards each year. CSAC uses a scoring matrix to prioritize among eligible applicants. This matrix places greatest weight on an applicant’s financial need, but it also considers certain socioeconomic factors and GPA. Although students may receive either Cal Grant A or B awards through the competitive program, the vast majority (99 percent) of competitive awards are Cal Grant B. (Cal Grant C awards are offered through a separate process detailed in the next section.)

CTE Students May Also Qualify for Other State and Federal Gift Aid. In addition to Cal Grants, various other financial aid programs provide fee waivers or grants to CTE students. Students attending CCC and enrolled in credit courses (including credit CTE courses) are eligible for a fee waiver that fully covers their tuition. (Noncredit CTE courses are offered free of charge to students.) In addition, Cal Grant recipients who enroll full time at CCC are eligible for a Student Success Completion Grant worth up to $4,000 annually. Finally, low‑income students in all segments may be eligible for a Pell Grant—a federal award worth up to $6,095 annually.

Cal Grant C

Cal Grant C Is the Smallest of the Cal Grant Programs. While CTE students are eligible for several types of financial aid that are not specific to their education program, the Cal Grant C program is specifically targeted toward CTE students. State law authorizes up to 7,761 new Cal Grant C awards each year. In 2018‑19, the state provided $10 million for the program (with costs expected to grow to $10.6 million in 2019‑20). This amount represents less than 0.5 percent of total Cal Grant funding. At CCC, Cal Grant C recipients receive a maximum award of $1,094 annually for nontuition costs (in addition to having all their tuition costs waived through another program, worth up to $1,380 for a full‑time student). At private colleges, Cal Grant C recipients receive a smaller nontuition award and partial tuition coverage, for a total maximum award of $3,009 annually. Students are eligible for the maximum award if they enroll full time throughout the academic year. Awards are prorated for students enrolling part time or in programs shorter than one year in length.

CSAC Periodically Develops List of Allowable Cal Grant C Programs. State law requires CSAC to consult with state and federal agencies—including the CCC Chancellor’s Office and the California Workforce Development Board—to develop a list of occupational areas approved for the Cal Grant C program. Students enrolled or planning to enroll in education programs aligned with these occupational areas are eligible for Cal Grant C awards. CSAC must update the list of approved occupations at least every five years. The current list includes 131 occupations ranging from website development to welding.

Statute Prioritizes Applicants When Cal Grant C Demand Exceeds Supply. Chapter 627 introduced rules for prioritizing Cal Grant C applicants, and Chapter 692 modified and added to these rules. These rules are intended to prioritize applicants based on two major considerations:

- Strategic Workforce Needs. CSAC consults with the Employment Development Department (EDD) to identify a subset of the eligible occupations that rank highly on at least two of four criteria: (1) number of job openings, (2) projected growth in jobs, (3) projected wages, and (4) alignment with a career pathway that leads to economic security. Applicants who intend to pursue these occupations receive priority. CSAC released the most recent list of priority occupations in 2016‑17. Figure 4 shows these priority occupations.

- Socioeconomic Disadvantages. Applicants may also receive priority based on socioeconomic factors. For example, CSAC gives priority points to applicants who have been unemployed for six months or longer, applicants who are single parents or dependents of single parents, and applicants with no expected family contribution to their educational expenses (as calculated by a federal need‑based formula).

Figure 4

Students Pursuing These 30 Occupations Are Prioritized for Cal Grant C Awards

2016‑17 Through 2020‑21

|

Occupation Group |

Occupation |

|

Health Care |

Cardiovascular Technologists and Technicians |

|

Dental Hygienists |

|

|

Diagnostic Medical Sonographers |

|

|

Occupational Therapy Assistants |

|

|

Physical Therapy Assistants |

|

|

Radiologic Technologists |

|

|

Registered Nurses |

|

|

Respiratory Therapists |

|

|

Surgical Technologists |

|

|

Installation, Maintenance, and Repair |

Aircraft Mechanics and Service Technicians |

|

Electrical Power‑Line Installers and Repairers |

|

|

Industrial Machinery Mechanics |

|

|

Telecommunications Equipment Installers and Repairers |

|

|

Telecommunications Line Installers and Repairers |

|

|

Construction |

Brickmasons and Blockmasons |

|

Electricians |

|

|

Elevator Installers and Repairers |

|

|

Plumbers, Pipefitters, and Steamfitters |

|

|

Architecture and Engineering |

Architectural and Civil Drafters |

|

Civil Engineering Technicians |

|

|

Electrical and Electronics Engineering Technicians |

|

|

Computer |

Computer Network Support Specialists |

|

Computer User Support Specialists |

|

|

Web Developers |

|

|

Protective Services |

Firefighters |

|

Police and Sheriff’s Patrol Officers |

|

|

Other |

Water and Wastewater Treatment Plant and System Operators |

|

Claims Adjusters, Examiners, and Investigators |

|

|

Insurance Sales Agents |

|

|

Paralegals and Legal Assistants |

Students Must Submit Supplemental Form to Apply for Cal Grant C Awards. Students who want to be considered for Cal Grant C awards must complete a supplemental form in addition to a FAFSA. During the period covered in this report, CSAC sent the supplemental form to students who indicated an intent to pursue CTE on their FAFSA but were not selected for Cal Grant A or B awards. (In 2018‑19, CSAC began sending the supplemental form to students who were not selected for Cal Grant A or B awards, regardless of whether they indicated an intent to pursue CTE on their FAFSA.) The form asks applicants to report their occupational goal, the length of the program they intend to enroll in, and other information (including work history, education history, and length of unemployment) that CSAC may use in its selection process.

Campuses Verify Student Eligibility Before Disbursing Payments. After CSAC makes Cal Grant award offers, campus financial aid staff must verify recipients’ eligibility. For Cal Grant C awards, this process requires staff to confirm that students are enrolled in a CTE program four months to two years in length. Campus financial aid staff are not required to verify that students are pursuing the specific occupational goal indicated on their supplemental form.

Findings

Statute requires our office to report on the following aspects of the Cal Grant C program: (1) the age, gender, and segment of attendance of award recipients; (2) the occupations prioritized for awards; (3) the number of applicants prioritized based on their occupational goals; and (4) the workforce outcomes of award recipients. Our first report, which was released in 2015, covered Cal Grant C recipients who received their initial award from 2010‑11 through 2014‑15. This report covers Cal Grant C recipients through 2017‑18.

Profile of Award Recipients

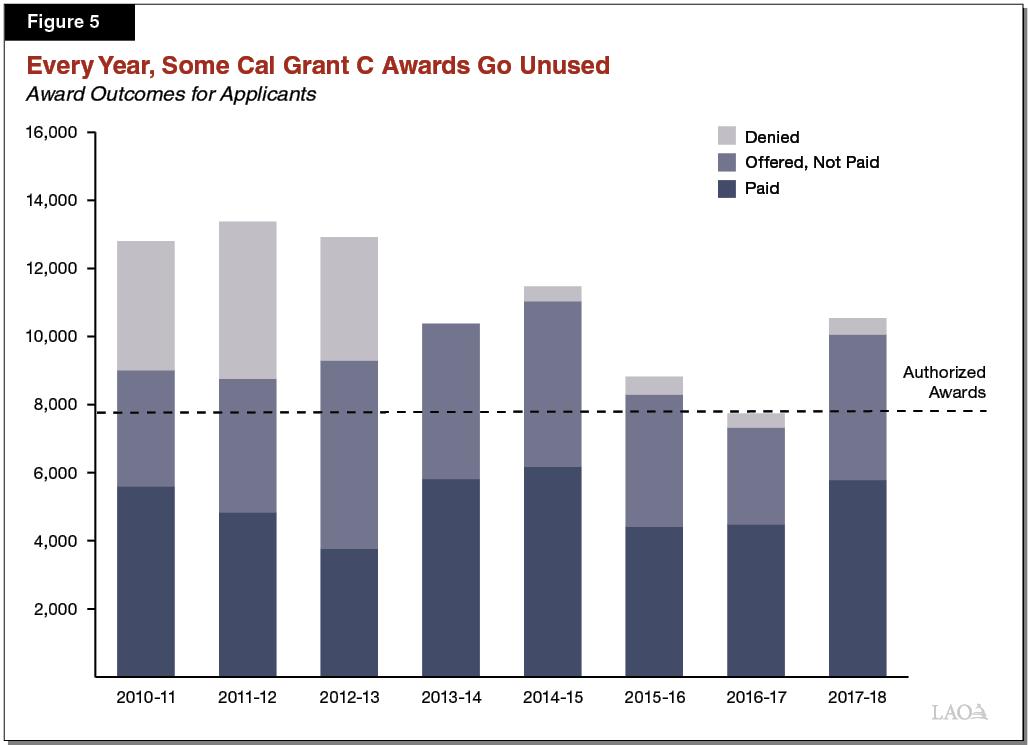

All Eligible Applicants Are Approved for Cal Grant C Awards. As Figure 5 shows, the number of students receiving Cal Grant C awards has consistently fallen short of the number of awards authorized in statute. In 2013‑14, CSAC expanded the number of offered awards to increase the number of awards that are ultimately paid. (In most years, between one‑third and half of applicants offered Cal Grant C awards do not accept the awards.) Since that change, CSAC has not had to use prioritization criteria. (Each year, some applicants are ineligible for awards, typically because they did not indicate an occupational goal or because their education program was not of an eligible length.)

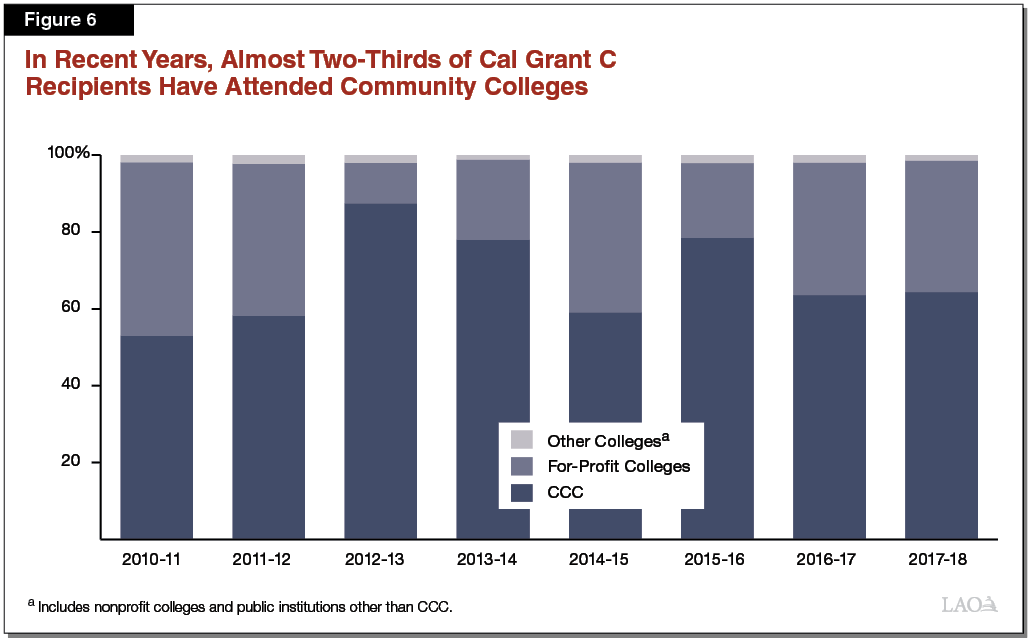

Share of Recipients Attending Private Colleges Has Fluctuated. While many Cal Grant C recipients attend CCC, a substantial share of recipients attend for‑profit colleges. A very small share (less than 2 percent) attend nonprofit colleges or public schools other than CCC (including a public health sciences college operated by Los Angeles County). Figure 6 shows that the share of recipients at for‑profit colleges has ranged from 10 percent to 45 percent. This fluctuation likely reflects changes in the colleges eligible for Cal Grants. State law deems colleges ineligible for Cal Grants if they have particularly low graduation rates or high rates of students defaulting on loans. The years with fewer Cal Grant C recipients enrolled at for‑profit colleges correspond to years in which many colleges in this segment lost Cal Grant eligibility.

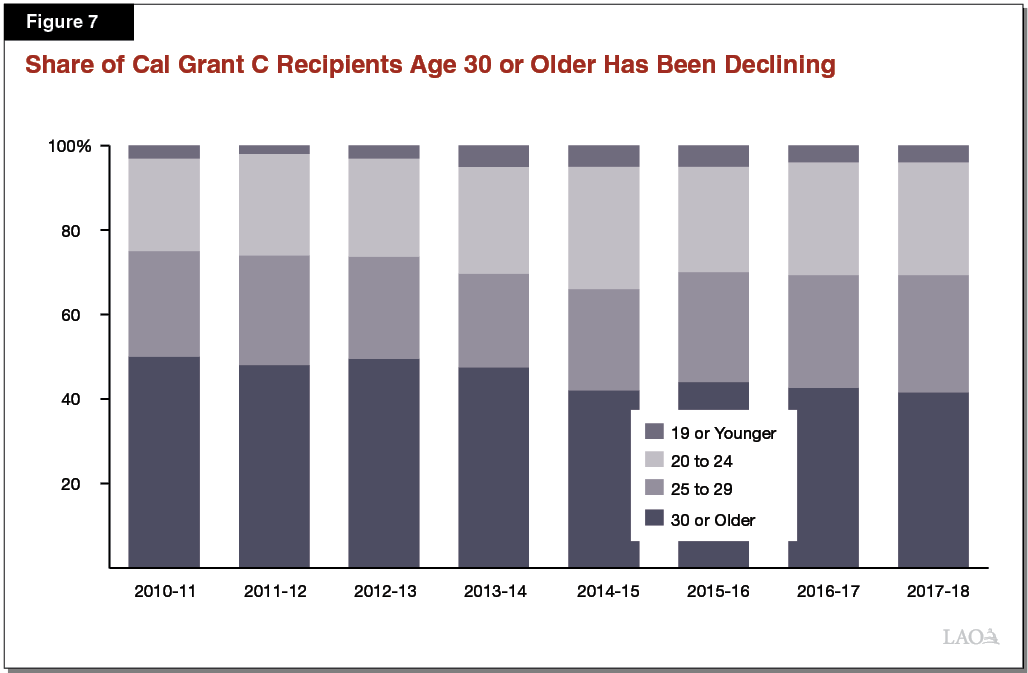

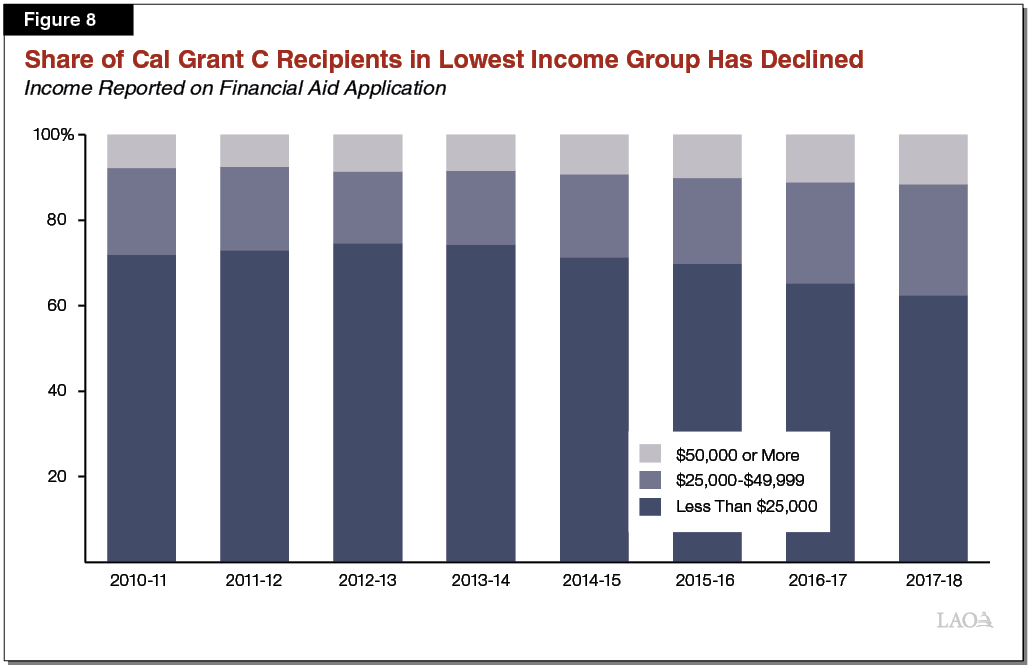

Demographics of Award Recipients Have Changed Somewhat Over Time. As Figure 7 shows, the percentage of recipients age 30 or older has decreased across the past eight years, while the percentage in all three of the younger age spans has increased. The average age of recipients declined from 33 to 31 over the period. Regarding gender, about two‑thirds of Cal Grant C recipients are female. The gender distribution has remained relatively consistent over time. According to CSAC’s data, the percentage of recipients who were unemployed at the time of application peaked in 2013‑14 at 41 percent and has steadily declined since that time. As of 2017‑18, 30 percent of new Cal Grant C recipients were unemployed. As Figure 8 shows, the percentage of recipients with a family income of less than $25,000 has also declined. These trends likely reflect the economic recovery that occurred across this time period.

No Perceptible Shift Toward Prioritized Occupations. Each year since 2013‑14, slightly more than one‑third of award offers have gone to applicants who indicated that they intended to pursue a prioritized occupation (Figure 9). CSAC updated the priority list in 2016‑17, and we considered whether this changed the occupational mix of applicants offered awards. After the new priority list went into effect, no noticeable increase occurred in the share of award offers going to applicants pursuing occupations on the new list. Moreover, some occupations removed from the priority list, such as licensed vocational nurses and automotive mechanics, remained among the top occupational goals of applicants offered awards.

Figure 9

About One‑Third of Applicants Indicate Intent to Pursue Priority Occupations

|

2012‑13 |

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

|

|

Total applicants offered award |

9,293 |

10,374 |

11,036 |

8,296 |

7,330 |

10,056 |

|

Number pursuing priority occupations |

5,240 |

3,772 |

3,853 |

3,033 |

2,562 |

3,453 |

|

Percent pursuing priority occupations |

56% |

36% |

35% |

37% |

35% |

34% |

Health Care Occupations Are Growing in Popularity. The percentage of recipients who indicated that they intended to pursue an occupation related to health care increased from 36 percent in 2012‑13 to 51 percent in 2017‑18. This trend is likely due to both student preferences and greater program availability. For‑profit colleges account for the majority (almost 90 percent) of the growth in Cal Grant C recipients who intend to pursue health care occupations.

Outcomes of CCC Award Recipients

Outcome Data Are Limited to Cal Grant C Recipients From Community Colleges. The following section covers the program completion and employment outcomes of students who first received Cal Grant C awards from 2014‑15 through 2017‑18. The CCC Chancellor’s Office provided these data for Cal Grant C recipients enrolled in their colleges. We also requested similar data from several for‑profit colleges that enroll a large share of Cal Grant C recipients. However, we generally did not receive sufficient data to draw conclusions about the outcomes of Cal Grant C recipients at for‑profit colleges.

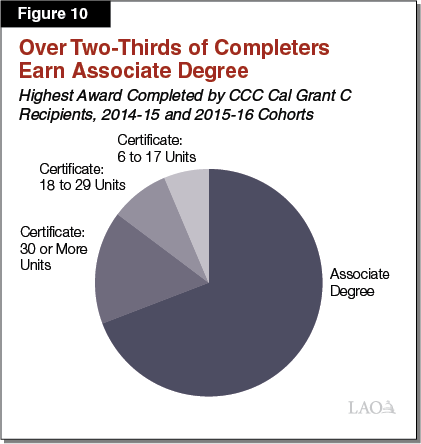

About Half of CCC Cal Grant C Recipients Complete a Certificate or Degree. As of June 2018, half of CCC students who first received Cal Grant C awards in 2014‑15 or 2015‑16 had completed a certificate or degree. This is comparable to CCC’s six‑year completion rate (48 percent), suggesting that Cal Grant C recipients are at least as likely to complete as CCC students overall. (Though fewer students in the later Cal Grant C cohorts had completed certificates or degrees by June 2018, some were likely still working toward completion.) Among completers in the two earlier cohorts, more than two‑thirds earned an associate degree, with the remainder earning a certificate (Figure 10). In addition, 85 percent of completers earned a degree or certificate of 30 or more units. This suggests that most Cal Grant C recipients are likely pursuing programs that meet the length requirement for Cal Grant B awards (at least one year).

Top Programs Completed Have Been Relatively Consistent Over Time. Although a new list of priority occupations went into effect in 2016‑17, the mix of education programs that Cal Grant C recipients complete has not changed significantly since that time. CCC students who first received Cal Grant C awards in 2016‑17 or 2017‑18 have completed similar programs as the two previous cohorts (Figure 11). Only two of the top ten programs completed by the more recent cohorts correspond to occupations on the new priority list.

Figure 11

Recent Cal Grant C Recipients Are Completing Similar Programs to Earlier Cohorts

Most Common Programs of Study Completed by CCC Cal Grant C Recipientsa

|

Program of Study |

Rank for Recent Cohorts |

Rank for Earlier Cohorts |

Prioritized Occupationb |

|

Registered Nursing |

1 |

1 |

Yes |

|

Transfer Studies |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Automotive Technology |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Humanities |

4 |

7 |

|

|

Biological and Physical Sciences |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Child Development/Early Care and Education |

6 |

6 |

|

|

Radiologic Technology |

7 |

12 |

Yes |

|

Liberal Arts and Sciences |

8 |

5 |

|

|

Licensed Vocational Nursing |

9 |

14 |

|

|

Cosmetology and Barbering |

10 |

16 |

|

|

aBased on Cal Grant C recipients who have completed certificates or degrees to date. Some recipients (particularly in recent cohorts) may still be enrolled. bBased on the updated priority list that went into effect in 2016‑17. |

|||

Some Cal Grant C Recipients Complete Programs in Non‑CTE Fields. Of Cal Grant C recipients who completed an education program at CCC, about 85 percent earned a CTE certificate or degree. The remaining completers may have intended to pursue a CTE program when they were first awarded Cal Grant C awards but switched to another program before completion. The most common non‑CTE programs completed by Cal Grant C recipients were transfer studies, humanities, and the biological and physical sciences.

Workforce Outcomes Are Available for Most CCC Students Receiving Cal Grant C Awards. The CCC Chancellor’s Office tracks workforce outcomes for all students through a data‑sharing partnership with EDD. The EDD database includes wages and employment settings for most California workers, except those who are self‑employed, working for the federal government, or serving in the military. We limit our discussion of workforce outcomes to students who first received Cal Grant C awards in 2014‑15 because many students in later cohorts were likely still in college as of 2017 (the most recent year for which EDD data was available).

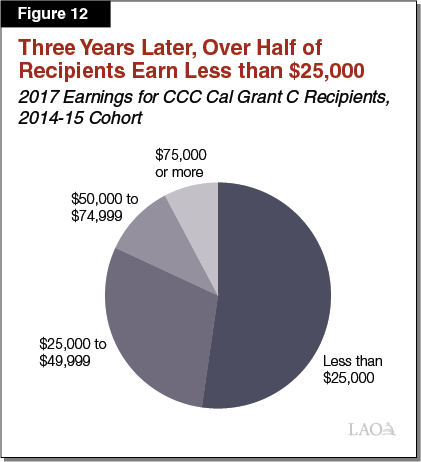

Most Recipients Find Employment, but Many Earn Less Than $25,000 Per Year. Of CCC students who first received Cal Grant C awards in 2014‑15, 73 percent appeared in the EDD database in 2017, indicating these recipients were employed approximately three years after their initial award acceptance. The remaining 27 percent were either unemployed or employed in a setting excluded from the EDD database. About half of the employed recipients in the EDD database earned less than $25,000 in 2017 (Figure 12). We cannot estimate an hourly wage for these recipients as some of them may have been working part time or only part of the year.

Employment Settings Span Diverse Range of Industries. Figure 13 shows the most common employment settings for the 2014‑15 Cal Grant C cohort. Over one‑third of employed recipients in this cohort worked in one of these ten industries in 2017. Recipients who earned less than $25,000 were most likely to work in temporary help services, elderly services, schools, and restaurants. In contrast, recipients who earned $75,000 or more were most likely to work in hospitals.

Figure 13

Top Employment Settings Range From Hospitals to Grocery Stores

Industries Employing CCC Cal Grant C Recipients, 2014‑15 Cohorta

|

Rank |

Industry |

|

1 |

General Medical and Surgical Hospitals |

|

2 |

Temporary Help Services |

|

3 |

Elementary and Secondary Schools |

|

4 |

Government Offices |

|

5 |

Services for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities |

|

6 |

Limited‑Service Restaurants |

|

7 |

Full‑Service Restaurants |

|

8 |

Physician Offices |

|

9 |

Supermarkets and Other Grocery Stores |

|

10 |

Community Colleges |

|

a Based on employment data from 2017. Recipients working in multiple industries are counted under the industry in which they earned the most wages. |

|

Assessment

Based on our findings and conversations with financial aid administrators, we have identified a number of concerns with the Cal Grant C program, discussed throughout the remainder of this section.

Recent Changes to Cal Grant C Program Have Not Had Significant Impact on State Workforce. In creating new prioritization criteria, the Legislature intended to better align Cal Grant C awards with strategic workforce needs. Given so few individuals apply for Cal Grant C awards, CSAC has not needed to use the prioritization criteria. Only about one‑third of Cal Grant C awards are offered to applicants who indicated on their supplemental forms that they intend to pursue a prioritized occupation. Furthermore, only two of the top ten programs of study completed by the two most recent cohorts of Cal Grant C recipients at CCC align with a prioritized occupation, while four of the top ten programs are not even considered CTE. Finally, while some Cal Grant C recipients find employment in high‑wage settings, other recipients continue to work in lower‑wage settings such as restaurants and grocery stores.

Many Recent CTE Initiatives Likely to Be Reaching More Students. Over the past several years, the state has undertaken several initiatives that attempt to better align CTE programs with workforce needs. The creation of the Adult Education Program, Strong Workforce Program, and a new online community college are among the most notable of these efforts. Like the Cal Grant C program, these programs are designed to benefit students enrolling in CTE programs that are linked with gainful employment opportunities. Whereas the Cal Grant C program serves roughly 10,000 students annually, these other programs by comparison are intended to support systemic improvements impacting CTE students on a much larger scale.

Cal Grant C Program Requires Complicated Financial Aid Application Process. The supplemental form that Cal Grant C applicants must submit in addition to a FAFSA likely decreases program participation. Students may not understand the importance of the supplemental form, be deterred by the additional paperwork, or be unsure how to answer certain questions on the form. The program’s complex eligibility requirements also create administrative challenges for campus financial aid staff. Staff report that they spend substantial time examining each Cal Grant C recipient’s course registration patterns to verify enrollment in a CTE program. These aspects of the Cal Grant C program run counter to the Legislature’s recent interest in simplifying Cal Grant rules and requirements to help both students and staff navigate the financial aid system more easily.

Substantial Overlap Between Cal Grant C and Cal Grant B Eligibility. Many of the CTE students eligible for a Cal Grant C award also are eligible for a Cal Grant B award. Data from CCC indicate that most programs completed by Cal Grant C recipients are at least one year long and thus meet the length requirement for the Cal Grant B program. If these students had received a Cal Grant B award, they would have received greater financial assistance. The Cal Grant B nontuition award ($1,672 annually) is worth about 150 percent of the Cal Grant C nontuition award ($1,094 annually). In addition, students may receive a Cal Grant B award for the equivalent of four years of full‑time study, whereas state law limits Cal Grant C awards to two calendar years.

Recommendations

Recommend Phasing Out Cal Grant C and Serving CTE Students Through Main Cal Grant Programs. Given its shortcomings in meeting strategic workforce needs and the complexity it adds to the state’s financial aid system, we recommend phasing out the Cal Grant C program and redirecting the associated funds to a much larger existing financial aid program that is also open to CTE students—the Cal Grant competitive program. CSAC has already initiated the 2019‑20 Cal Grant C award cycle, so we recommend beginning the phase out in 2020‑21. We estimate the state could offer approximately 2,000 new competitive awards in 2020‑21, raising the total number of new competitive awards from the existing statutory level of 25,750 to 27,750. (The administration also has a 2019‑20 budget proposal to increase the number of new competitive awards.)Our estimate of the number of new competitive awards the state could fund takes into account associated renewal awards (such that competitive program costs would increase to an estimated $10.6 million at full implementation).

Competitive Program Has Several Advantages for Students. In general, CTE students are eligible for the competitive program and could thus benefit from an increase in the number of available competitive awards. (One notable exception is for students pursuing CTE programs of less than one year—an issue discussed below.) Compared to the Cal Grant C program, the competitive award program has several advantages for these students. First, the competitive program is easier to navigate because applicants are not required to submit a supplemental form and are not restricted to training in specific occupational areas. Second, the competitive program offers greater financial assistance by providing a larger annual award for a greater number of years. Redirecting funds from the Cal Grant C program to the competitive program also increases the likelihood that all offered awards are used. Whereas some Cal Grant C awards go unused each year, nearly all authorized competitive awards are taken, with demand for them far exceeding the number of available competitive awards.

Consider Lowering the Cal Grant B Program Length Requirement. Students pursuing CTE programs at least four months but less than one year long currently are not eligible for Cal Grant competitive awards. If the Legislature wishes to retain Cal Grant eligibility for these students, it could consider reducing the minimum program length for Cal Grant B awards from one year to four months. We recommend the Legislature weigh the associated trade‑offs carefully. On the one hand, shortening the minimum program length would expand access to Cal Grant awards for some CTE students. On the other hand, some research suggests students completing shorter CTE programs tend to experience lower wage increases than students completing longer CTE programs. (Lowering the program length requirement for Cal Grant B awards would also expand eligibility for the entitlement program, thus increasing total Cal Grant spending.)

Conclusion

Several years ago, the Legislature made changes to the Cal Grant C program with the intent of better addressing both the state’s workforce needs and students’ financial needs. Since implementing these changes, the Legislature has undertaken several larger efforts to expand CTE offerings and restructure financial aid opportunities. Compared to the Cal Grant C program, these broader efforts have the potential to both reach more CTE students and provide more financial aid coverage to Cal Grant recipients. In light of these more recent efforts, we recommend the Legislature phase out the Cal Grant C program and instead provide more financial aid to CTE students through the Cal Grant competitive program.