LAO Contact

May 2, 2019

Improving California's Prison Inmate Classification System

- Introduction

- Background

- Assessment of CDCR’s Inmate Classification System

- LAO Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Overview of California’s Inmate Classification System. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) uses an inmate classification system to assign inmates to different housing security levels and varying degrees of supervision during their daily activities. Assignment to a housing security level is generally based on inmates’ assessed risk of misconduct—referred to as their “housing score.” The performance of the inmate classification system has implications for the safety of staff, inmates, and the public; prison operations and cost; the size of the inmate population; and inmates’ daily experiences in prison, including their access to rehabilitation opportunities.

Assessment of Inmate Classification System. In reviewing CDCR’s inmate classification system, we identified several issues that merit legislative consideration. Specifically we found the following:

- Housing Score Not Sufficiently Aligned With Departmental Goals. We find that CDCR may be assigning unnecessary security to inmates who are prone to engage in minor misconduct, but not in serious misconduct. This approach is inconsistent with the department’s goal to avoid placing inmates in more secure or restrictive settings than necessary.

- Accuracy of Housing Score Could Be Limited. We identified several factors that call into question the accuracy of CDCR’s housing score methodology. Specifically, we found that: (1) CDCR has modified the methodology without reassessing its accuracy, (2) several changes—such as to the demographics of the inmate population—could have caused its accuracy to deteriorate since it was first established, and (3) there is some evidence that the methodology underweights age. We also found that the methodology for recalculating inmates’ housing scores annually has never been evaluated.

- Need for Some Overrides of Housing Score Is Unclear. Under certain circumstances, CDCR staff can override an inmate’s housing score and house the inmate at a security level different than otherwise called for under the department’s methodology. However, given that three of the factors for which staff can override a housing score—inmates’ age, time to serve, and behavior—are already included in the housing score methodology, it is unclear what additional benefits, if any, these particular overrides provide.

- Access to Lowest Security Settings May Be Overly Restricted. CDCR currently maintains policies that exclude certain inmates from the lowest security housing and supervision placements. To the extent that these policies cause certain inmates to be placed in unnecessarily restrictive environments, they unnecessarily create state costs and operational challenges.

LAO Recommendations. In order to address the above concerns, we recommend the Legislature take the following steps to improve the inmate classification process:

- Direct CDCR to Develop New Method for Assignment to Housing Security Level. We recommend CDCR contract with independent researchers to develop a new methodology for assigning inmates to a housing level when they arrive in prison and annually thereafter. We find that a more effective methodology could reduce prison violence and other misconduct while minimizing placement of inmates in unnecessarily restrictive environments that can make them more prone to crime in the long run.

- Consider Options to Expand Access to Lowest Security Settings. We recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to create processes for allowing low‑risk sex offenders, inmates with more than five years left to serve, and inmates wanted by another law enforcement agency on minor charges into the lowest security settings. Such changes could alleviate existing operational challenges and reduce state costs—potentially in the tens of millions of dollars annually—without jeopardizing prison security or public safety.

Introduction

Maintaining a safe environment for inmates and staff, as well as preventing inmate escapes, are fundamental aspects of the public safety mission of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). The department uses an inmate classification system as a key tool to pursue this mission. The inmate classification system essentially assigns inmates to housing and varying degrees of security based on their assessed risk of misconduct and other factors, such as escape risk. Accordingly, the classification system significantly influences how CDCR deploys scarce housing space and custody staffing and has important implications for state costs. Moreover, because the system determines where and how inmates are housed and supervised, it significantly affects the daily experiences of individual inmates. In addition, because housing and supervision placements can affect inmates’ abilities to earn credits that reduce their prison terms, the classification system can affect how long some inmates ultimately spend in prison. In this report, we (1) provide background information on CDCR’s inmate classification system, (2) assess the current system, and (3) recommend steps to improve it.

Background

Purpose of Inmate Classification

Prevent Inmate Escape and Misconduct. One of the primary challenges facing prison systems is preventing escape and misconduct, which can range from crimes (such as murder, assault, and drug trafficking) to more minor violations of prison rules (such as misuse of food or unexcused absence from a work assignment). Inmate classification systems are commonly employed prison management tools that allow prison officials to allocate security resources according to inmates’ likelihood of escape or misconduct. These systems typically involve procedures to identify inmates with a high incentive for escape or risk factors that make them statistically more likely to engage in misconduct. This allows prison officials to place such inmates in more secure environments.

It is important to place inmates in the appropriate security setting for several reasons. On the one hand, placing inmates in a setting with insufficient security could jeopardize the safety of staff, other inmates, and the public. On the other hand, placing inmates in an overly restrictive setting can create other significant problems. For example, it can create a long‑term public safety risk by making inmates more prone to crime through the influence of more criminally active peers. We also note that inmates placed in more restrictive settings may have less access to rehabilitative programming than other inmates. In addition, research has found that placing inmates in overly restrictive settings can exacerbate mental illness. Moreover, providing a higher level of security than is warranted results in an inefficient use of limited resources.

California’s Current Classification System Established Nearly 20 Years Ago. California was the first state in the nation to use a standardized inmate classification system based on objective criteria. This system was first evaluated in the 1980s. It subsequently underwent a significant overhaul and evaluation in the early 2000s, which formed the basis of the system that is still in place today. The stated goals of CDCR’s system include (1) uniformly placing inmates in the lowest security level necessary to ensure the safety of staff, inmates, and the public; and (2) generally basing placements on objective information and criteria. In establishing the inmate classification system, the department also sought to maintain a database for research and evaluation of the system.

How Are Inmates Classified?

CDCR’s inmate classification system differentiates inmates in two primary ways. Specifically, the system assigns each inmate a (1) housing security level and (2) custody designation.

Housing Security Level. Housing security level generally determines the type of facility where inmates are housed. Inmates that the system determines have a higher risk of misconduct or escape are generally housed in higher security level facilities that have more security features, such as armed guard coverage or an electric fence.

Custody Designation. Custody designation determines where in the prison inmates may go during the day and the level of supervision they must be under when they are there. For example, inmates assigned to the lowest custody designation may work off prison grounds with minimal supervision by CDCR correctional officers. In contrast, inmates with the highest custody designation can only work within the building where they are housed and must be under the direct physical control of correctional officers at all times. Custody designation also affects inmates’ eligibility to be housed in certain facilities. For example, based on the combination of their housing level, custody designation, and other criteria, some inmates are eligible for placement in specialized housing, such as conservation camps (one of the lowest security placements).

Below, we provide greater detail on how the inmate classification system is used to assign inmates to a housing security level, a custody designation, and specialized housing.

Assignment to a Housing Security Level

CDCR Operates Four Security Levels of Inmate Housing. CDCR categorizes its facilities that house male inmates into security levels ranging from Level I (lowest security) to Level IV (highest security). (Facilities that house female inmates are not classified into different security levels as female facilities generally have similar levels of security.) Figure 1 summarizes the security requirements for each of the four security levels. As shown in the figure, inmates housed in Level I facilities are subject to the least amount of security and are generally housed in open dormitories (rather than cells) that are not required to have perimeter security—meaning some may be only surrounded by a razor wire fence or have no fence at all.

Figure 1

Higher Security Level Housing Facilities Have More Security Requirementsa

|

Level |

Minimum Required Bed Type |

Minimum Required Perimeter Security |

Armed Coverage |

|

I (lowest security) |

Dormitories |

None |

None required |

|

II |

Dormitories |

Electric fence or wall with guard towers |

None required |

|

III |

Cells |

Electric fence or wall with guard towers |

External |

|

IV (highest security) |

Cells |

Electric fence or wall with guard towers |

External and internal |

|

aThere may be some exceptions to these requirements. |

|||

Inmates housed in Level II facilities generally also live in dormitories, though unlike Level I facilities, Level II facilities are located within the main security perimeter of the prison—meaning behind an electric fence or wall with guard towers. Inmates housed in Level III and IV facilities live in cells within the main security perimeter of the prison. Level IV facilities also often contain additional security features, such as a higher level of armed guard coverage and layouts that provide officers greater visibility of all cells.

We note that, CDCR maintains other housing units that are not part of its four‑level security ranking. For example, restricted housing units—units which can be used to temporarily house inmates as punishment for a serious rule violation or who constitute a particular threat to prison security—and reception centers—which house inmates when they first arrive in CDCR custody and have not been fully classified—are not designated as one of the four security levels.

Inmates Assigned Housing Score Based on Their Risk of Misconduct. When inmates arrive at a reception center, they receive a risk assessment in which they are assigned points totaling from 0 to 999 based on six factors that are statistically associated with in‑prison misconduct. These factors are (1) age at first arrest, (2) age at time of assessment, (3) term length, (4) gang membership, (5) number of prior incarcerations, and (6) behavior during prior incarcerations. The points assigned to each factor are summed to calculate a total housing score. Inmates with higher scores are considered to be more likely to engage in misconduct. Figure 2 illustrates how the housing score is calculated for two different inmates.

Figure 2

Housing Score Is Calculated Based on Factors in Inmates’ Backgrounds

|

Number of Points Assigned |

Inmate A |

Inmate B |

|

|

Age at First Arrest |

|||

|

Under 18 |

12 |

12 |

— |

|

18 to 21 |

10 |

— |

10 |

|

22 to 29 |

8 |

— |

— |

|

30 to 35 |

4 |

— |

— |

|

36 and Older |

— |

— |

— |

|

Age at Time of Assessment |

|||

|

16 to 20 |

8 |

— |

— |

|

21 to 26 |

6 |

— |

— |

|

27 to 35 |

4 |

— |

4 |

|

36 and Older |

— |

— |

— |

|

Term Length |

Years x 2 (Up to 50 Points) |

5 x 2 = 10 |

25 X 2 = 50 |

|

Gang Member |

6 |

— |

6 |

|

Number of Prior Incarcerations |

|||

|

Prior Jail or County Juvenile Sentence of 31 Days or More |

1 |

— |

— |

|

Prior State or Federal Juvenile Incarceration |

1 |

1 |

— |

|

Prior State or Federal Adult Incarceration |

1 |

— |

1 |

|

Behavior During Last 12 Months of Prior Incarceration |

|||

|

No Serious Rule Violations |

‑4 |

‑4 |

— |

|

Serious Rules Violations |

Violations x 4 |

— |

3 x 4 = 12 |

|

Specific Serious Rule Violations During Prior Incarceration |

|||

|

Battery or Attempted Battery on a Non‑Inmate |

Violations x 8 |

— |

2 x 8 = 16 |

|

Battery or Attempted Battery on an Inmate |

Violations x 4 |

— |

— |

|

Distribution of Drugs |

Violations x 4 |

— |

2 x 4 = 8 |

|

Possession of a Deadly Weapon |

Violations x 4 (Doubled if in Last 5 Years) |

— |

— |

|

Inciting a Disturbance |

Violations x 4 |

— |

— |

|

Battery Causing Serious Bodily Injury |

Violations x 16 |

— |

1 x 16 = 16 |

|

Scores |

19 |

123 |

Inmates’ housing scores are generally recalculated annually. Points are subtracted if inmates avoid serious rule violations, perform well in work or school, or achieve placement in the lowest custody designation since their housing score was last calculated. For example, if an inmate remains free of serious disciplinary issues for six months, two points are subtracted from his or her score. Conversely, points are added to inmates’ housing scores if they have engaged in certain rule violations since their housing score was last calculated. For example, if an inmate commits a battery on an inmate, four points are added to his or her score.

Current Housing Score Methodology Established Nearly 20 Years Ago. The underlying basis of the department’s current methodology for calculating inmates’ housing scores when they first arrive in prison was established in the early 2000s by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Specifically, the researchers removed certain factors from the previous methodology that were not found to be statistically associated with misconduct (such as marital status and military service) and added certain factors that were associated with misconduct (such as gang affiliation and mental illness). They then randomly assigned inmates to be housed based on either the revised or previous methodology. After completing an evaluation of the revised methodology, the UCLA researchers found it to be more effective in predicting misconduct than the previous methodology and it was subsequently implemented for all inmates beginning in 2003. (We note that CDCR later removed mental illness from the methodology in response to a lawsuit.)

Housing Security Level Is Generally Determined by Score, Unless Score Is Overridden. As shown in Figure 3, CDCR has established certain scores—or “cut points”—that divide the range of inmate housing scores into four groups, each corresponding with a different housing security level. For example, an inmate with a housing score of 19 through 35 is typically housed in a Level II facility. We note that the current cut points were established based on research conducted by University of California researchers in 2010 and 2011.

Figure 3

Housing Security Level Cut Points

|

Housing Score |

Housing Security Level |

|

Under 19 |

I |

|

19‑35 |

II |

|

36‑59 |

III |

|

60 and Over |

IV |

However, CDCR can override an inmate’s housing score and house the inmate at a security level that is different than otherwise called for under the department’s methodology. An override can happen through one of two ways:

- Mandatory Overrides. These overrides require staff to place inmates at a higher housing level than their score indicates. Currently, there are six mandatory overrides, as shown in Figure 4. Five of the six mandatory overrides result in inmates being housed at Level II rather than Level I. These overrides are intended to prevent inmates with a relatively high risk of escaping or victimizing the public if they escape from being placed in Level I facilities. This is because Level I facilities are generally not surrounded by electric fences or walls with guard towers, which are effective in preventing inmate escapes. Inmates who are not allowed in Level I facilities include those inmates who have attempted escape in the past, have certain histories of violence, or have committed a registerable sex offense.

- Discretionary Overrides. These overrides give CDCR staff the discretion to place inmates at a higher or lower housing level than their score indicates. There are 25 discretionary overrides. For example, staff can house inmates at a lower level due to a record of good behavior or their youthfulness, immaturity, or advanced age. Alternatively, staff can place inmates at a higher security level if their disciplinary records indicate (1) a history of serious problems or (2) that they could threaten the security of the facility. Staff can also override an inmate’s housing score if the inmate requires medical or psychological treatment that is only available at certain housing levels.

Figure 4

Six Mandatory Overrides of Housing Score

|

Reason for Override |

Mandatory Minimum Housing Level |

|

Sentenced to life without the possibility of parole |

II |

|

History of escape |

II |

|

History of sex offense |

II |

|

History of violence and does not meet certain criteriaa |

II |

|

Sentenced to life with the possibility of parole and does not meet certain criteriab |

II |

|

Sentenced to death |

IV |

|

aCriteria include being within five years of release and having a minimum of seven years since last violent offense. bCriteria include having been evaluated by a psychologist to represent a low or moderate risk of violence and not having a high level of notoriety. |

|

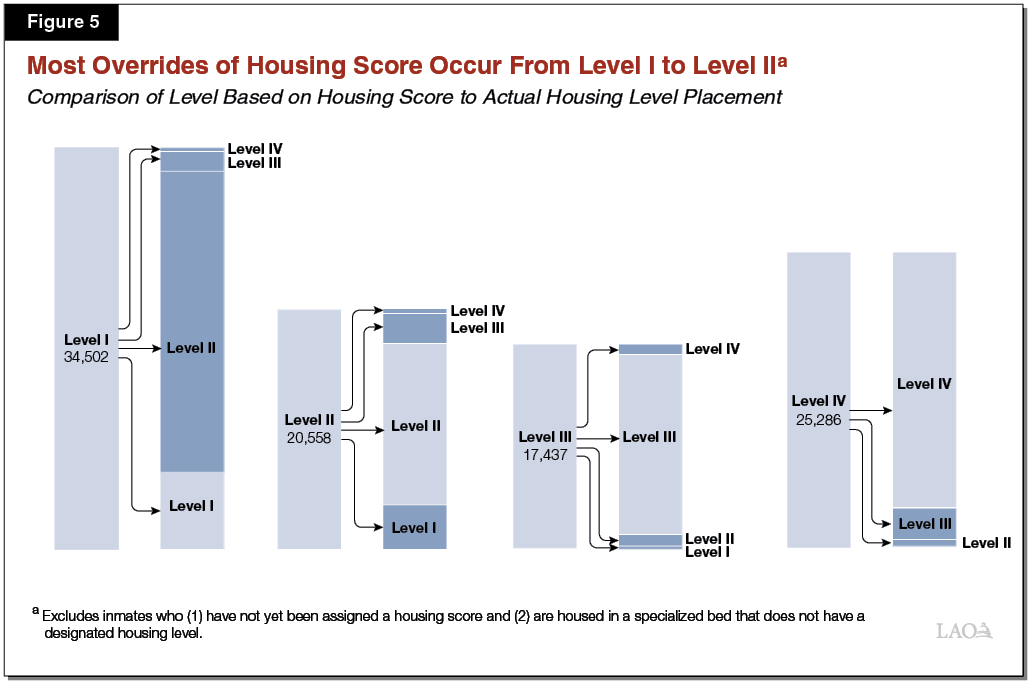

As of June 30, 2018, there were nearly 40,000 inmates in state prison whose housing score was overridden by CDCR staff as a result of either a mandatory or discretionary override. As shown in Figure 5, the majority of these overrides—about 25,700—occur from Level I to Level II. Of these particular cases, the vast majority (about 20,000) were moved from Level I to Level II as a result of two mandatory overrides—history of violence or sexual offending. This is likely one of the primary reasons why Level I facilities are populated at less than their design capacity when compared to other housing levels. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not “double‑bunk” inmates in dormitories.) As shown in Figure 6, CDCR’s Level I facilities are only at 85 percent capacity, while Level II and III facilities are over 120 percent of capacity. (Given that CDCR often houses two inmates per cell or double‑bunks inmates in dormitories, it is not uncommon for the population of a facility to exceed its design capacity to some degree.)

Figure 6

Level I Facilities Are Under Capacitya

As of June 30, 2018

|

Housing Level |

Number of Inmates |

Design Capacity |

Percent of Capacity |

|

I |

10,596 |

12,505 |

85% |

|

II |

40,689 |

33,377 |

122 |

|

III |

22,938 |

18,420 |

125 |

|

IV |

23,759 |

14,936 |

159 |

|

Totals |

97,982 |

79,238 |

124% |

|

aExcludes inmates who (1) have not yet been assigned a housing score and (2) are housed in a specialized bed that does not have a designated housing level. |

|||

Assignment to a Custody Designation

CDCR Classifies Inmates Into Six Custody Designations. Once inmates arrive at the prison to which they were assigned at the reception center, they are assigned a custody designation. CDCR uses six custody designations: (1) Maximum, (2) Close, (3) Medium A, (4) Medium B, (5) Minimum A, and (6) Minimum B, which are summarized in Figure 7. As shown in the figure, custody designations affect the level of supervision inmates receive during daily activities, with Maximum requiring the highest level of supervision. We note that CDCR has the flexibility to apply different custody designations to inmates within the same housing security level. For example, an inmate placed on Close Custody receives constant supervision during his work activities, so that staff can sufficiently account for the inmate’s specific location at all times. In contrast, an inmate placed on Medium A Custody in the same housing level would only receive frequent supervision, so that staff can sufficiently ensure that the inmate is present within a permitted work area.

Figure 7

Custody Designation Determines Level of Supervision Provided to Inmate

|

Custody Designation |

Required Level of Supervision During Daily Activities |

Required to Live in Cells? |

May Work Outside Main Security Perimeter? |

May Be Housed and Work Off Prison Grounds? |

|

Minimum B (least supervision) |

Sufficient supervision to ensure the inmate is present. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Minimum A |

Observed at least hourly if assigned outside the main security perimeter and sufficient supervision to ensure the inmate is present if inside the main security perimeter. |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Medium B |

Frequent and direct supervision while inside the main security perimeter and direct and constant supervision while outside the main security perimeter. |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Medium A |

Frequent and direct supervision. |

No |

No |

No |

|

Close |

Direct and constant supervision. |

Yesa |

No |

No |

|

Maximum (most supervision) |

Direct physical control of inmate by custody staff at all times. |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

aFemale inmates placed on Close Custody may be housed in certain dormitories. |

||||

Custody Designation Can Limit Access Outside of Main Perimeter and Credit Earning Rates. CDCR also uses custody designation to limit access to areas beyond the main security perimeter of the prison to inmates who pose a low escape risk. For example, as shown in Figure 7, inmates with a Minimum B, Minimum A, or Medium B Custody designation are allowed varying amounts of access to areas outside the main security perimeter. In contrast, inmates with a Maximum, Close, or Medium A designation must live and attend programs and work assignments within the main security perimeter of the prison.

In addition, custody designation affects the amount of sentencing credits that some inmates earn. Specifically, inmates who are placed on Minimum Custody (either Minimum A or Minimum B) and are not serving certain sentences (such as a sentence for a violent crime) can earn two days off their sentence for every day served with good behavior. If these inmates were at a higher custody designation they would instead be earning one day off their sentence for every day served with good behavior.

Custody Designation Determined by Various Criteria. Custody designation is assigned based on the presence or absence of certain factors as follows:

- Maximum Custody. Inmates who are temporarily living in a restricted housing unit often as punishment for committing particularly severe rule violations, such as assault or possession of a weapon.

- Close Custody. Inmates who meet certain criteria, such as those who (1) are in the first 5 years of a sentence of 25 years or more to life, (2) have a history of escape, or (3) have committed a severe rule violation.

- Medium A and B Custody. Inmates who are not required to be on Maximum or Close Custody and do not meet the criteria for Minimum Custody. The default designation is generally Medium A. However, inmates are assigned Medium B Custody in certain cases, such as if there is a need for them to work outside the main security perimeter of the prison.

- Minimum A and B Custody. Inmates who meet various criteria including having a housing score of 35 or lower with no mandatory overrides applied (such as having committed a registerable sex offense). Inmates must also not be wanted by law enforcement for a felony and must be within five years of release. Inmates are generally only assigned Minimum B Custody if they are placed in a program that requires them to live outside the main security perimeter of a prison, such as a conservation camp.

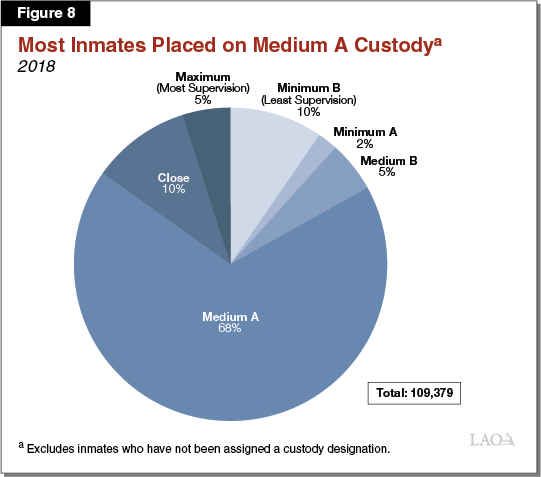

Figure 8 shows the breakdown of the inmate population by custody designation. The majority of inmates are placed on Medium A Custody.

Assignment to Specialized Housing

Based on Both Housing Level and Custody Designation. In most cases, inmates’ housing placements are not affected by their custody designation. However, some specialized housing placements—which tend to be the most and least restrictive housing in CDCR—do depend on inmates’ custody designation. For example, to be eligible for a Minimum Support Facility (MSF) or conservation camp—both types of Level I facilities that are outside the main security perimeter of prisons—inmates must not only be eligible for Level I placement, but they must have a Minimum B Custody designation, as this allows them to live and work outside of a secure perimeter. (Please see the nearby box for more information about MSFs and conservation camps.)

Minimum Support Facilities (MSFs) and Conservation Camps

MSFs are located on prison grounds but are outside of the main security perimeter of the prison. Inmates in MSFs provide important forms of operational support to prisons, such as grounds keeping and fire protection. In addition, when certain areas of the prison are “locked down”—meaning that inmates are confined to their dormitories or cells and cannot go to their regularly scheduled work assignments within the prison due to security concerns—MSF inmates temporarily fill these inmates’ jobs so that key aspects of prison operations that depend on inmate labor (such as the kitchen and laundry) can continue to function.

Conservation camps are located off prison grounds, often in remote areas of the state. Inmates in conservation camps contribute to state wildfire fighting efforts by serving on hand crews. (Hand crews are usually made up of 17 workers that cut “fire lines”—gaps where all fire fuel and vegetation is removed—with chain saws and hand tools.) There are about 3,500 inmates housed in 42 conservation camps throughout the state that are generally jointly operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. When not responding to fires, these inmates are available to support fire prevention and other resource conservation projects.

Specialized Housing Can Affect Inmates’ Credit Earning Status. In some cases, inmates housed in conservation camps can earn time off of their prison sentence faster than they would if housed elsewhere at Minimum Custody, such as in an MSF. For example, offenders serving terms for violent felonies can earn one day off of their prison sentence for every day they serve with good behavior in a conservation camp rather than only one day off for every four days they serve if housed elsewhere.

Assessment of CDCR’s Inmate Classification System

In reviewing CDCR’s inmate classification system, we identified several issues that merit legislative consideration. As summarized in Figure 9, we found that (1) the housing score methodology is not sufficiently aligned with the goals of the department’s inmate classification system, (2) the accuracy of the housing score methodology could be limited, (3) the need for some discretionary overrides of the housing score is unclear, and (4) access to Level I housing and Minimum Custody designations may be overly restricted. We discuss each of our findings in more detail below.

Figure 9

Review of Inmate Classification System—Summary of Major Findings

|

|

|

|

Housing Score Not Sufficiently Aligned With Departmental Goals

Higher Points Given for Any Misconduct. As previously indicated, one of the stated goals of CDCR’s inmate classification system is to uniformly place inmates in the lowest security level consistent with the safety of staff, inmates, and the public. To put it another way, CDCR’s goal is to ensure that inmates are not placed in a higher housing security level (more restrictive) than necessary. However, the department’s housing score methodology is designed to assign higher points to inmates likely to engage in any misconduct—meaning both serious and nonserious misconduct. For example, the system allocates the same amount of points to an inmate likely to engage in serious misconduct (such as assault) as an inmate likely to engage in minor misconduct (such as use of vulgar language) and may not require additional security resources. Accordingly, CDCR may be assigning unnecessary security to inmates who are prone to engage in minor misconduct, but not in serious misconduct. This approach is inconsistent with CDCR’s goals because it may result in inmates who do not represent a serious safety concern being placed in more restrictive settings than necessary. Moreover, it also results in an inefficient use of limited security resources.

Accuracy of Housing Score Could Be Limited

As discussed above, the accuracy of CDCR’s housing score methodology has important implications for prison security, costs, and inmates’ experiences while incarcerated. If the system incorrectly assesses certain inmates as having relatively high risks of misconduct, these inmates could be placed in more restrictive housing than necessary. Such a placement potentially threatens public safety as it could make inmates more prone to crime. In contrast, if the system incorrectly assesses certain inmates as having relatively low risks of misconduct, these inmates could jeopardize public safety through escape or misconduct.

In our review of CDCR’s housing score methodology, we identified several factors that call into question the accuracy of the methodology in predicting misconduct. Specifically, we find that (1) CDCR has modified the methodology without reassessing its accuracy, (2) several changes—such as to the demographics of the inmate population—could have caused its accuracy to deteriorate over time, and (3) researchers have found some evidence suggesting that age is underweighted in the methodology. Furthermore, we find that the methodology for recalculating inmates’ housing scores annually has never been evaluated in terms of accurately reflecting changes in inmates’ likelihood of committing misconduct.

Impact of Modification Made to Scoring Methodology Has Not Been Assessed. As discussed above, the underlying basis of the department’s current methodology for calculating inmates’ housing scores when they first arrive in prison was established in the early 2000s by researchers at UCLA. In 2008, in response to a lawsuit, CDCR removed mental illness from the set of factors that increased inmates’ scores. The department or external researchers, however, have not assessed the impact of this modification on the accuracy of the score in predicting inmate misconduct—making it unclear whether the scoring methodology is more or less accurate.

Several Changes Could Have Impacted Accuracy of Methodology. The researchers who established CDCR’s current housing score methodology in the early 2000s used data on the conduct and characteristics of inmates from the late 1990s. Accordingly, the current system effectively assigns risk scores to current inmates based on how similar they are to inmates that engaged in misconduct in the 1990s. For example, because the researchers found that inmates in the late 1990’s who were first arrested at a young age were more likely to engage in misconduct, the system assigns higher risk scores to current inmates who share this characteristic. However, any changes in the underlying relationships between these characteristics and misconduct may have caused the accuracy of the assessment to deteriorate over time. For example, if inmates who were first arrested at a young age no longer engage in misconduct at higher rates than other inmates, this would cause the accuracy of the assessment to decrease. Experts who study risk assessments designed to predict outcomes for a certain population generally recommend reassessing the accuracy of such tools whenever there are significant changes in the population for which the tool is used.

We find that several key changes could have caused the relationships between inmate characteristics and misconduct to change over time. These include changes in the following areas:

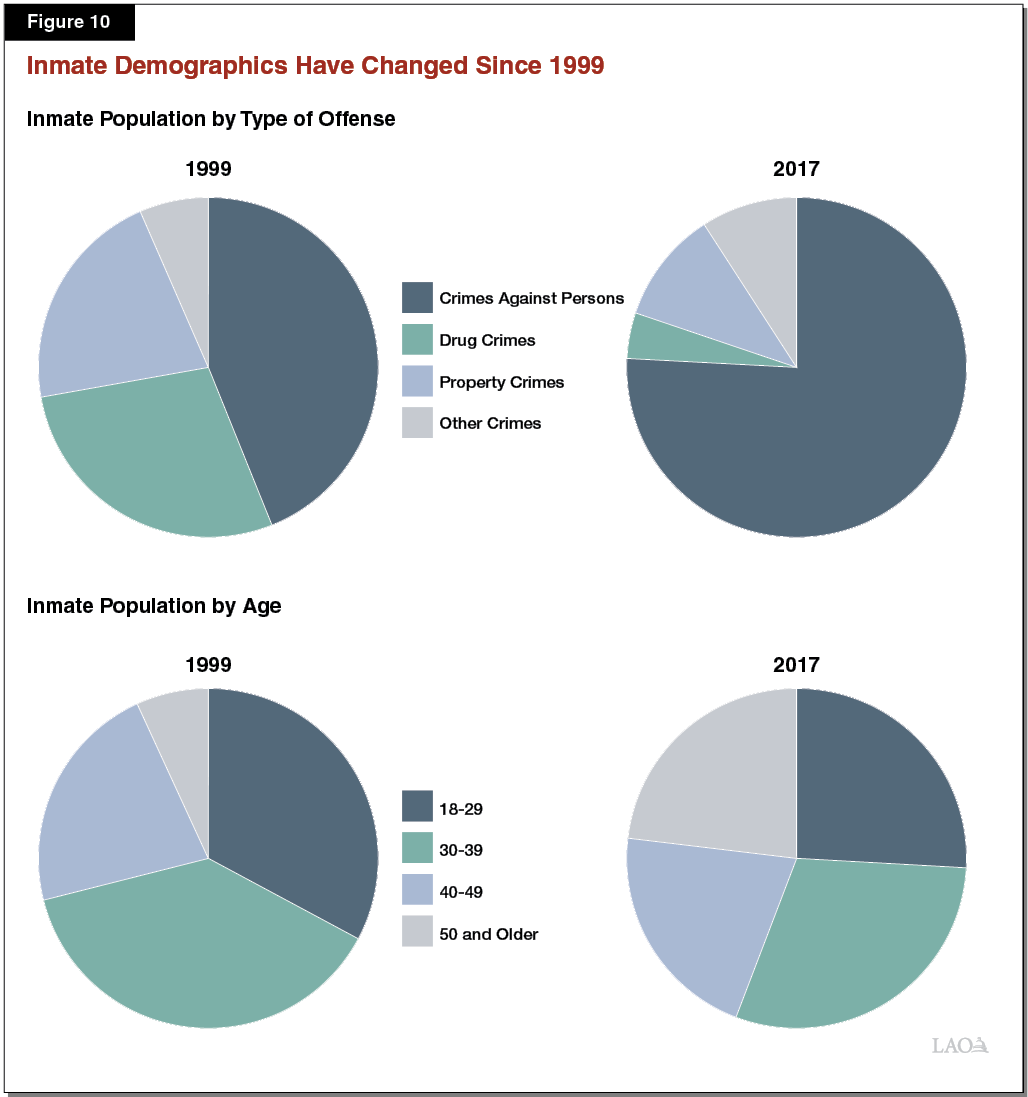

- Inmate Demographics. The demographics of the state’s inmate population have changed significantly since the housing score methodology was developed using inmate data from the late 1990s. This is largely due to changes in sentencing law such as the 2011 realignment, which shifted responsibility for housing lower‑level felons from the state to the counties. (Please see the nearby box for an overview of recent changes in sentencing law.) As shown in Figure 10, inmates are, on average, older and more likely to be serving a term for a crime against persons now than they were when the housing score methodology was developed. Accordingly, it is possible that shifting demographics have changed the relationships between inmate characteristics used to calculate the housing score and actual inmate misconduct, likely reducing the accuracy of the tool.

- How Inmates Are Housed. Since 2000, there have been two substantial changes in inmate housing conditions. First, the state has significantly reduced the level of overcrowding in its prisons. As of January 31, 2000 state prisons were at about 195 percent of their design capacity. However, by July 25, 2018, state prisons were populated at 136 percent of their design capacity. Some research has found that this reduction in prison overcrowding significantly reduced the amount of assaults and batteries committed by inmates in California. Second, in recent years, CDCR has shifted many prison gang leaders from restricted housing—where they have little communication with other inmates—to general population environments as a result of a federal court order limiting the use of restricted housing. It is plausible that these changes may have altered the relationships between inmates’ characteristics and their tendencies to engage in misconduct. For example, the average inmate today may be less likely to engage in misconduct due to reduced overcrowding but gang affiliated inmates may be more likely to engage in misconduct today due to the greater presence of gang leaders in general population environments.

- Inmate Incentives. The incentives for inmates to avoid misconduct have increased. First, CDCR has increased the number of inmates who are eligible to earn time off of their sentences for maintaining good behavior. For example, since 2017 CDCR began allowing certain offenders to reduce their prison sentences by as much as a third through avoiding misconduct. Second, the number of inmates considered for release by the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) before serving their entire sentence has increased. For example, Proposition 57 (2016) made nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration. Because BPH weighs avoiding misconduct favorably, inmates who are eligible for release by BPH have a strong incentive to avoid misconduct.

- Access to Rehabilitation Programs. CDCR has significantly increased the number of rehabilitation programs offered and the amount of time that inmates can earn off of their sentences from completing such programs. To the extent these programs are effective in reducing misconduct, greater participation in these programs may make some inmates less likely to engage in misconduct.

- Data Quality. The quality of CDCR data on inmate characteristics and behavior has also likely improved. This is because CDCR has expanded and updated its data systems significantly over the last two decades, allowing the department to capture more detailed and likely more accurate information about inmate characteristics and conduct. Moreover, the quality of data on inmate gang involvement has likely improved since the late 1990s because CDCR did not use inmate gang affiliation data for the purposes of inmate classification at that time. Accordingly, the researchers who developed the housing score methodology have informed us that inmates currently labeled as gang affiliated are probably more likely to be actually gang affiliated than inmates labeled as such in the data they used to develop the methodology nearly two decades ago.

Recent Policy Changes Impacting the Inmate Population

In recent years, the Legislature and voters have enacted various constitutional and statutory changes that significantly impacted the composition of the state’s inmate population. Some of the major changes include:

- 2011 Realignment. In 2011, the Legislature adopted legislation that limited who could be sent to state prison. Specifically, it required that certain lower‑level offenders serve their incarceration terms in county jail. Additionally, the legislation required that counties, rather than the state, supervise certain lower‑level offenders released from state prison.

- Proposition 36 (2012). Proposition 36 reduced prison sentences for certain offenders subject to the state’s existing three‑strikes law whose most recent offenses were nonserious, nonviolent felonies. It also allowed certain offenders serving life sentences to apply for reduced sentences.

- Proposition 47 (2014). Proposition 47 reduced penalties for certain offenders convicted of nonserious and nonviolent property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. It also allowed certain offenders who had been previously convicted of such crimes to apply for reduced sentences.

- Proposition 57 (2016). Proposition 57 expanded inmate eligibility for parole consideration, increased the state’s authority to reduce inmates’ sentences due to good behavior and/or the completion of rehabilitation programs, and mandated that judges determine whether youth be subject to adult sentences in criminal court.

Researchers Have Raised Concerns About Score Accuracy. As mentioned earlier in this report, CDCR commissioned University of California researchers in 2010 to assess whether there are any natural “tipping points” that correspond with clear increases in misconduct along the continuum of inmate housing scores. While this study was not an evaluation of the accuracy of the housing score in assessing inmates’ risk of misconduct, the researchers did inadvertently uncover some evidence suggesting that inmate age appeared to be underweighted in the housing score methodology. Specifically, the researchers found that they were able to better predict inmate misconduct using inmates’ housing scores and age than by using their housing score alone. This suggests that, even though housing score methodology is intended to include the effect of age on the likelihood of misconduct, it does not give a strong enough weight to age relative to the other factors. Accordingly, the researchers recommended that CDCR commission a study to investigate whether a new housing score system might perform better. However, such a study has not been done at this time.

Accuracy of Method for Annual Recalculation of Housing Score Never Assessed. The UCLA researchers that developed CDCR’s housing score system in the early 2000s only assessed the accuracy of the methodology they developed to calculate inmates’ initial housing scores at reception centers. They did not assess the accuracy of CDCR’s methodology for adding or subtracting points from inmates’ housing scores annually thereafter. As such, it is unclear whether the factors that CDCR uses to move inmates’ score up and down after their initial placement accurately reflect changes in inmates’ risk of misconduct. Moreover, even if the factors used to adjust the score are appropriate, it is unclear if the amount that the score is adjusted is consistent with inmates’ change in risk. This could mean that CDCR is housing inmates in either overly or insufficiently restrictive settings as a result of the annual recalculation.

Need for Some Discretionary Overrides of Housing Score Is Unclear

As discussed above, there are several reasons why inmate classification staff can choose to place inmates in a housing level that is inconsistent with their score. Three of these reasons—inmates’ age, time to serve, and behavior—are factors that are currently included in the housing score methodology. Thus, it is unclear what additional benefit, if any, these overrides would provide if inmates’ scores already reflect the statistical impact of their age, time to serve, and behavior on their likelihoods of misconduct. Research suggests that risk assessments, such as the housing score, generally more accurately predict risk than humans can by applying their judgement. Accordingly, the use of judgement to override a risk assessment in these cases raises concerns that it may be causing inmates to be assigned to either overly or insufficiently restrictive housing. Moreover, to the extent that staff overrides are necessary because of the inaccuracy of the housing score, it could be indicative that age, time to serve, or behavior are not appropriately weighted in the housing score methodology. Such inaccuracy could be due to the factors discussed above that have likely caused the accuracy of the score to decline since it was first developed.

Access to Level I and Minimum Custody May Be Overly Restricted

CDCR’s policies for limiting inmates’ access to Level I housing and Minimum Custody designation appear to be overly restrictive in a few ways. Specifically, it is unclear why low‑risk sex offenders are excluded from Level I housing and Minimum Custody and why inmates with more than five years left to serve or minor felony detainers are excluded from Minimum Custody. To the extent that these policies cause certain inmates to be placed in unnecessarily restrictive environments, they unnecessarily create state costs and operational challenges. We discuss these concerns in further detail below.

Unclear Why Low‑Risk Sex Offenders Are Excluded From Level I and Minimum Custody. Currently, CDCR excludes all inmates who have committed a registerable sex offense—including those who are not currently serving a term for that offense—from Level I facilities and from Minimum A and B Custody designations. This is based on the assumption that these particular offenders pose a greater threat to public safety if they were to escape when compared to other offenders. However, research suggests that the risk of sexual reoffending decreases markedly with time that offenders remain sex offense free in the community. Specifically, some individuals who have committed a sex offense in the past but are not committing new sex offenses eventually become less likely to commit a sex offense than an offender with no history of sexual offending. Moreover, research shows that the risk of an offender sexually reoffending can be reliably predicted with widely accepted risk assessments, such as the Static‑99 assessment that CDCR currently uses to identify low‑risk sex offenders. This suggests that the department may not need to exclude all sex registrants from Level I facilities and Minimum Custody given that it can identify the subset of sex offenders who pose a minimal risk to public safety. Accordingly, the current policy has the potential to unnecessarily exclude some low‑risk sex offenders from Level I facilities (including conservation camps and MSFs) and Minimum Custody.

Unclear Why Inmates With Longer Time Left to Serve Are Excluded From Minimum Custody. As previously indicated, inmates with more than five years left to serve are currently excluded from Minimum A and B Custody designations. The underlying rationale is that such inmates have a greater incentive to escape to avoid serving the remainder of their sentences relative to those inmates within less than five years of release. Given this policy, those inmates with more than five years to serve are therefore ineligible from being housed in conservation camps and MSFs. While it appears reasonable to assume that inmates above a certain number of years left to serve have relatively more to gain from escaping prison, it is unclear why or how CDCR concluded that five years was an appropriate cutoff point.

Unclear Why Inmates With Minor Felony Detainers Are Excluded From Minimum Custody. District attorneys, courts, and law enforcement agencies may notify CDCR that an inmate is wanted by that agency for a felony and in some cases request that the inmate be released into the agency’s custody after completing his or her prison term. This is referred to as a detainer. For example, after an inmate is committed to prison for a certain crime, a law enforcement agency may discover evidence implicating that inmate in a separate crime that occurred before the inmate was incarcerated. The agency could then issue a detainer to CDCR for that inmate. As discussed earlier, inmates with outstanding felony detainers are excluded from Minimum Custody, and therefore ineligible for placement in conservation camps and MSFs. The rationale is that such inmates have an incentive to escape from prison to avoid facing felony charges. However, inmates facing minor felony charges have a relatively similar incentive to escape compared to inmates with no felony charges. For example, an inmate with one year left to serve on his or her current sentence and an outstanding detainer for an offense that carries a two year prison term would have a similar incentive to escape as an inmate with three years left to serve but with no felony detainer. However, only the inmate with no felony detainer would be eligible for Minimum Custody. Accordingly, the current policy has the potential to unnecessarily exclude some inmates with detainers from Minimum Custody.

State Prison Costs and Operational Challenges. The unnecessary exclusions of certain inmates from Level I facilities and Minimum Custody likely increase state prison costs in two ways. First, because inmates assigned to Minimum Custody or housed in a conservation camp can earn credits at higher rates than they otherwise would, placing them in higher‑level facilities results in them serving longer sentences than otherwise. This, in turn, increases the inmate population and associated state costs.

Second, it results in the state spending more than necessary on contract beds due to a lack of bed space in state prisons that could have otherwise been freed up to the extent CDCR moved additional inmates to conservation camps. This is because the state currently can only house a limited number of inmates in state owned and operated prisons—not including conservation camps—due to a court‑ordered cap on the number of inmates that can be housed in such facilities and utilizes contract beds to help meet this population cap. (See the nearby text box for more information on the court‑ordered prison population cap.) We note that it currently costs about $18,000 more annually to house an inmate in a contract bed than in a state prison bed or a conservation camp. As of February 27, 2019 the state housed nearly 3,500 inmates in conservation camps, though camps have a total design capacity of nearly 4,700. Accordingly, CDCRs overly expansive exclusions on camp eligibly—which have contributed to the roughly 1,000 vacant camp beds—could be costing the state tens of millions of dollars annually in unnecessary expenditures on contract beds.

Federal Court Ordered California to Limit Prison Population

In November 2006, plaintiffs in two ongoing class action lawsuits—now called Plata v. Newsom (involving inmate medical care) and Coleman v. Newsom (involving inmate mental health care)—filed motions for the courts to convene a three‑judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act. On August 4, 2009, the three‑judge panel declared that overcrowding in the state’s prison system was the primary reason that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison system. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell.) The court ruling applies to the number of inmates in prisons operated by CDCR, and does not preclude the state from holding additional offenders in other public facilities (such as conservation camps) or private facilities.

To comply with the prison population cap, the state took a number of actions, including (1) housing inmates in contracted facilities, (2) constructing additional prison capacity, and (3) reducing the inmate population through several policy changes. For example, in 2011, the state shifted the responsibility for housing and supervising certain lower‑level felons to counties. In addition, Proposition 57 (2016) led to a reduction in the prison population by expanding inmate eligibility for parole consideration and increasing the state’s authority to reduce inmates’ sentences due to good behavior and/or the completion of rehabilitation programs.

In addition to increasing state prison costs, these exclusions can exacerbate operational challenges faced by CDCR. Specifically, CDCR currently has challenges filling inmate jobs in MSFs due to a lack of inmates who qualify for both Level I and Minimum Custody placements. Allowing more inmates to receive these placements, and thus qualify to live in an MSF, would likely help CDCR to fill these inmate jobs. This in turn, could help support prison operations, such as grounds keeping or facility fire protection, and help support facilities that need additional inmate workers due to lockdowns.

Moreover, by excluding low‑risk sex offenders from all Level I facilities, these policies unnecessarily increase the number of inmates who must be housed in Level II facilities. However, currently, Level I facilities are populated at less than 100 percent of their design capacity, while Level II facilities are populated at over 100 percent of their design capacity. To the extent that CDCR could increase the population of Level I facilities, it could potentially create more flexibility for housing Level II inmates. This is important because CDCR can face challenges in placing inmates in facilities that simultaneously meet their rehabilitative, medical, mental health, and security needs.

State Firefighting Costs and Operational Challenges. Finally, by contributing to the roughly 1,000 vacant conservation camp beds, these exclusions reduce the number of inmates who would otherwise be available to support state wildfire fighting and prevention efforts. When insufficient inmate hand crews are available, the state must use other hand crews—such as those formed by employees of federal agencies or private companies—which can increase costs. Furthermore, to the extent CDCR could increase the population of conservation camps, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection could accomplish more fire prevention work—such as fuel reduction—when inmates are not actively engaged in fighting fires.

LAO Recommendations

Based on our assessment of CDCR’s policies and practices for assigning inmates to varying levels of housing security and supervision by staff, we recommend the Legislature take certain steps to improve the inmate classification process. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature (1) direct CDCR to contract with independent researchers to develop a new methodology for assigning inmates to housing levels and (2) consider various options to expand access to Level I facilities and Minimum Custody. We discuss each of these recommendations in greater detail below.

Develop New Housing Score Methodology

We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to contract with independent researchers to develop a new methodology for assigning inmates to a housing level when they arrive at a reception center and annually thereafter. In our view, the researchers should develop the methodology by (1) using recent data and outcome variables that capture only misconduct that justifies additional security resources and/or (2) using a methodology that gives weight to different types of misconduct based on severity. We also recommend that the new scoring methodology be periodically assessed to ensure it remains effective in accurately predicting inmate misconduct.

By developing a new methodology, CDCR and the researchers will be able to (1) consider what forms of misconduct require additional security resources; (2) utilize recent data, which is likely more accurate, detailed, and reflective of current realities than past data; and (3) potentially eliminate the need for some manual overrides of the score. Together, these factors would likely allow CDCR to more accurately predict inmate misconduct and improve its ability to assign inmates to appropriate levels of security. This in turn, could help CDCR reduce prison violence and other misconduct while minimizing placement of inmates in unnecessarily restrictive environments that can make them more prone to crime in the long run. In addition, a more accurate methodology could eliminate the need to override housing score based on age, behavior, and sentence length using human judgement. We estimate that the cost of developing a new methodology would not likely exceed $1 million and could take a couple years. Until a new methodology is implemented statewide, we think it makes sense for CDCR to continue using its existing system for assigning inmates to a housing level.

Consider Options to Expand Access to Level I and Minimum Custody

As discussed above, access to Level I and Minimum A and B Custody designations may be overly restricted for certain inmates (such as inmates who have committed a sex offense but nevertheless have a low risk of recidivism). Accordingly, there are likely certain low‑risk inmates that could be placed in Level I housing or on Minimum Custody without jeopardizing safety. Depending on the number of such inmates, this change could reduce state costs—potentially in the tens of millions of dollars annually. Placing additional inmates in Level I and Minimum Custody could also mitigate existing operational challenges, such as a shortage of inmate labor in conservation camps and MSFs. Below, we discuss three options that the Legislature could consider for expanding access to Level I and Minimum Custody based on additional information from CDCR.

Allowing Low‑Risk Sex Offenders Into Level I and Minimum Custody. We recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to allow low‑risk sex offenders into Level I facilities and Minimum Custody. To help the Legislature determine whether such a change should be made, we recommend it direct CDCR to report on how it would identify sex offenders who are of low risk to escape and re‑offend for placement into Level I facilities and Minimum Custody. For example, CDCR could establish a set of criteria that include the inmate’s assessed risk of sexual re‑offense but also other factors, such as whether the inmate has participated in a sex offender treatment program and the amount of time elapsed since the inmate’s last offense. We note that in 2017 CDCR made a similar change for inmates with histories of violence. Specifically, the department narrowed the circumstances that require a mandatory override for an inmate’s history of violence. For example, if inmates meet certain criteria—such as having not committed a violent offense for at least seven years—staff have the discretion to remove the override. Similarly, CDCR also conducts case‑by‑case reviews for inmates with life terms, and gang member status who are seeking entrance to Level I facilities or Minimum Custody status. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to report on the number of inmates that would likely be affected if a review process were implemented for low‑risk sex offenders.

Reducing Time‑to‑Serve Restrictions for Minimum Custody. We recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to allow inmates with more than five years left to serve (up to some new, higher cut‑off point) to gain Minimum Custody status. To help the Legislature determine whether to make such a change, it may want to direct CDCR to contract with researchers to conduct a randomized trial to assess whether the time‑to‑serve cut off for placement on Minimum Custody status could be increased without causing an increase in escapes.

Allowing Inmates With Minor Felony Detainers Into Minimum Custody. We recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to allow inmates with minor felony detainers into Minimum Custody. To help the Legislature determine whether to make this change, we suggest directing CDCR to report on how it would identify inmates with minor felony detainers who would have a relatively low risk of escaping compared to inmates with more time at stake. For example, CDCR allows inmates with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement holds on Minimum Custody if they meet certain criteria (such as if he or she has family ties in California). Similarly, CDCR could create a set of criteria for allowing certain inmates with felony detainers on Minimum Custody. These new criteria could be linked to time‑to‑serve criteria already in place or any changes made to the time‑to‑serve criteria (discussed above). For example, if CDCR allows inmates with six years left to serve into Minimum Custody, it could also admit any otherwise eligible inmate whose current sentence in addition to potential sentence tied to a felony detainer is six years or less. The department should also report on the number of inmates that would likely be affected if the new process was implemented.

Conclusion

CDCR’s inmate classification system is a key tool for assigning inmates to appropriate amounts of housing security and staff supervision. The performance of the system has implications for the safety of staff, inmates, and the public; prison operations and cost; the size of the inmate population; and inmates’ daily experiences in prison, including their access to rehabilitation opportunities. We identified several concerns, which suggest that inmate housing placements may be based on inaccurate assessments of inmates’ risks of misconduct and that the system may be assigning too much security and supervision in certain cases. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature take various steps to improve CDCR’s inmate classification system to ensure that maximum benefit is achieved from the allocation of scarce security resources.