LAO Contact

May 13, 2019

The 2019-20 May Revision

Overview of the May Revision Proposition 98 Package

Introduction

In this post, we analyze the major changes related to Proposition 98 under the Governor’s May Revision. The first section provides background on the calculation of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and the Proposition 98 reserve. The next section describes the changes in the administration’s estimates of the minimum guarantee and Proposition 98 spending proposals. The last section provides our high-level assessment of these estimates and proposals.

Background

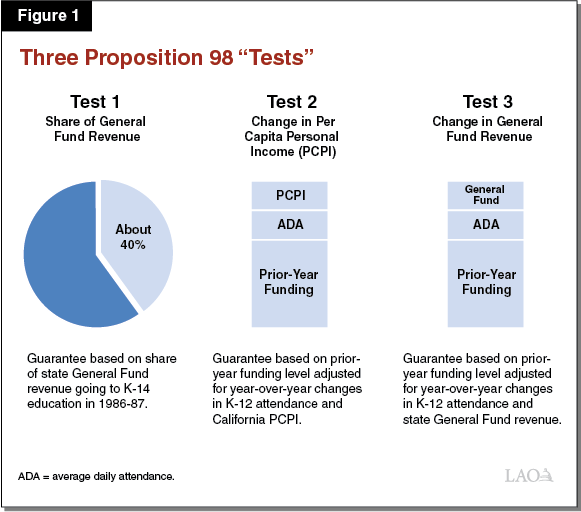

Proposition 98 Sets Minimum Funding Level for Schools and Community Colleges. Proposition 98, a constitutional amendment approved by the voters in 1988 and modified in 1990, establishes a minimal annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. This requirement is commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The state meets the minimum guarantee through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. To determine the minimum guarantee, the state calculates three main formulas (known as “tests”) set forth in the State Constitution (Figure 1). These tests depend upon several inputs, including changes in K‑12 attendance, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue. Depending on these inputs, one of the tests becomes “operative” and sets the minimum guarantee for the year.

Proposition 2 Requires Deposits Into Proposition 98 Reserve Under Certain Conditions. Proposition 2, a constitutional amendment approved by voters in 2014, established a reserve account within the Proposition 98 guarantee. The purpose of this reserve is to set aside some Proposition 98 funding in relatively strong fiscal times to help the state mitigate reductions to school funding in tighter times. The rules governing the Proposition 98 reserve generally require the state to make deposits when (1) revenue from taxes on capital gains are relatively high (above 8 percent of General Fund revenue); and (2) the minimum guarantee exceeds the prior-year funding level, adjusted for changes in student attendance and a growth factor typically linked with increases in per capita personal income. (In technical terms, the second condition can be satisfied only when Test 1 is the operative test and the Test 1 funding level exceeds the Test 2 funding level.) Another rule prohibited deposits into the Proposition 98 reserve until the minimum guarantee surpassed its peak prior to the Great Recession (adjusted for inflation) and certain outstanding Proposition 98 obligations were retired. This latter rule prevented any deposits into the reserve from 2014‑15 through 2018‑19.

Cap on School District Reserves Applies When Proposition 98 Reserve Reaches Certain Threshold. On a longstanding basis, state law has required school districts to have minimum local reserve levels. Legislation enacted in 2014 and amended in 2017 created a maximum local reserve level (or reserve cap) once the state Proposition 98 reserve reaches a certain level. Specifically, the local reserve cap applies if, during the previous year, the balance in the Proposition 98 reserve exceeded 3 percent of total Proposition 98 funding allocated for school districts that year. When the cap is in effect, most districts may hold reserves equivalent to no more than 10 percent of their annual General Fund expenditures. Districts seeking to carry higher reserves due to extenuating circumstances may apply to their county office of education for an exemption from the cap. All districts with 2,500 or fewer students are exempt from the cap. To date, the local reserve cap has never been in effect.

Changes in Estimates of Minimum Guarantee

Proposition 98 Funding Increases $746 Million Over the Budget Period. Figure 2 compares Proposition 98 funding under the Governor’s January budget and the May Revision. Compared with January, the May Revision contains $746 million in additional funding across the 2017‑18 through 2019‑20 period ($78 million in 2017‑18, $279 million in 2018‑19, and $389 million in 2019‑20). The administration funds at the estimated minimum guarantee for 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 but leaves funding $117 million above the estimated guarantee for 2017‑18. (The administration maintains its January proposal to repeal the Proposition 98 true-up account, such that the $117 million would not be credited to that account.) The additional Proposition 98 funding over the period is primarily attributable to stronger growth in General Fund revenue relative to the administration’s January estimates. A small portion of the increase is due to a slight upward revision in student attendance estimates for 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

Figure 2

Comparing Proposition 98 Guarantee Under Governor’s Budget and May Revision

(In Thousands)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Governor’s Budget |

|||

|

General Fund |

$52,887 |

$54,028 |

$55,295 |

|

Local property tax |

22,610 |

23,839 |

25,384 |

|

Totals |

$75,498 |

$77,867 |

$80,680 |

|

May Revision |

|||

|

General Fund |

$52,951 |

$54,445 |

$55,904 |

|

Local property tax |

22,625 |

23,701 |

25,166 |

|

Totals |

$75,576 |

$78,146 |

$81,069 |

|

Change |

|||

|

General Fund |

$64 |

$417 |

$608 |

|

Local property tax |

14 |

‑138 |

‑219 |

|

Totals |

$78 |

$279 |

$389 |

Proposition 98 General Fund Support Is Up $1.1 Billion. Though Proposition 98 funding is up $746 million across the period, Proposition 98 General Fund support is up $1.1 billion. This is because the administration’s estimates of local property tax revenue are down $343 million over the period. (This drop consists of a $14 million increase in 2017‑18, a $138 million decrease in 2018‑19, and $219 million decrease in 2019‑20.) The reduction is primarily due to lower estimates of several smaller components of the property tax, including prior-year tax payments and supplemental payments for properties sold in the middle of the year. The administration also lowered slightly their estimate of growth in secured taxes in 2019-20.

Proposition 98 Reserve Deposit

For First Time, State Meets Conditions for Making a Deposit Into the Proposition 98 Reserve. Of the $746 million in additional Proposition 98 funding, about half must be deposited into the Proposition 98 reserve account. In January, the administration calculated that the state would not meet the conditions for making a deposit because the minimum guarantee was growing less quickly than per capita personal income. Recent federal data, however, show per capita personal income growing more slowly than previously estimated. The downward revision in per capita personal income growth (from 5.07 percent to 3.85 percent)—combined with an upward revision to General Fund revenue and increase in the minimum guarantee—means that the conditions for a deposit are satisfied. Under the Proposition 2 formulas, the size of the required deposit is limited to the lower of (1) the difference between the Test 1 and Test 2 levels, and (2) the portion of the capital gains revenue attributable to Proposition 98. Under the May Revision, the lower of these two amounts is the $389 million difference between Test 1 and Test 2. This deposit is below the threshold required to trigger the local school district reserve cap (about $2.1 billion).

Changes in Proposition 98 Spending Package

Relatively Little Funding Available for New Commitments Beyond the January Budget. Of the additional Proposition 98 funding in the May Revision, about one-third is used for various baseline cost increases. These changes include slightly higher-than-expected student attendance and several one-time costs that emerged after the release of the Governor’s budget. Partially offsetting these increases is a small reduction in the statutory cost-of-living adjustment (estimated at 3.46 percent in January and finalized at 3.26 percent in May). After accounting for all these changes, the May Revision has roughly $150 million available for new commitments.

Provides More Ongoing Funding for Proposed Special Education Concentration Grants. The May Revision retains the Governor’s January proposal to provide special education concentration grants to districts serving large numbers of low-income students, English learners, and students with disabilities, but it increases total grant funding. Whereas the Governor’s budget proposed $577 million ($390 million ongoing and $187 million one time), the administration now proposes $696 million (all ongoing) for these grants. The $119 million net increase accounts for most of the funding available for new commitments under the May Revision. Figure 3 shows the change in ongoing funding for the special education grants and the other adjustments pertaining to Proposition 98 funding in 2019‑20.

Figure 3

2019‑20 Changes in Proposition 98 Spending

(In Millions)

|

Governor’s Budget |

May Revision |

Change |

|

|

2018‑19 Revised Spending |

$77,867 |

$78,146 |

$279 |

|

Technical Changes |

$185 |

‑$128 |

‑$313 |

|

State School Reserve |

— |

$389 |

$389 |

|

Preschool |

|||

|

COLA |

$41 |

$39 |

‑$2 |

|

2,959 full‑day slots added in April 1, 2019 (annualize cost) |

27 |

27 |

— |

|

Non‑LEA preschool (shift to non‑Proposition 98 funding) |

‑297 |

‑309 |

‑12 |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$229) |

(‑$244) |

(‑$14) |

|

K‑12 Education |

|||

|

LCFF COLA for districts and charter schools |

$2,027 |

$1,959 |

‑$68 |

|

Special education concentration grants |

390 |

696 |

306 |

|

COLA for select categorical programsa |

146 |

141 |

‑5 |

|

Standardized school district accounting system replacement (one time) |

3 |

3 |

— |

|

Southern California Regional Occupational Center (one time) |

— |

2 |

2 |

|

Otherb |

— |

— |

— |

|

LCFF costs covered with one‑time funds |

— |

‑251 |

‑251 |

|

Subtotal |

($2,567) |

($2,551) |

(‑$16) |

|

California Community Colleges |

|||

|

COLA for apportionments |

$248 |

$230 |

‑$18 |

|

College Promise fee waivers (extend program to sophomores) |

40 |

43 |

3 |

|

COLA for select student support programsc |

32 |

30 |

‑2 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.55 percent) |

26 |

25 |

‑1 |

|

Student Success Completion Grant (caseload adjustment) |

11 |

18 |

7 |

|

Legal services for undocumented students |

10 |

10 |

— |

|

Foster Care Education Programd |

— |

— |

— |

|

Strong Workforce Program (portion of costs shifted to one‑time funds) |

‑77 |

‑1 |

75 |

|

Subtotal |

($290) |

($354) |

($64) |

|

Total Changes |

$2,813 |

$2,534 |

$110 |

|

2019‑20 Proposed Spending |

$80,680 |

$81,069 |

$389 |

|

aApplies to special education, child nutrition, mandates block grant, services for foster youth, adults in correctional facilities, and American Indian education. bMay Revision provides $300,000 to add Cal Grant reporting requirements to the mandates block grant, $154,000 ongoing to the San Joaquin County Office of Education to maintain the School Accountability Report Card and School Dashboard databases, and $24,000 one time to translate the School Accountability Report Card and School Dashboard into Vietnamese, Mandarin, and Filipino (they are currently available in English and Spanish). cApplies to Adult Education, Apprenticeship Programs, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, mandates block grant, Disabled Students Programs and Services, CalWORKs student services, and campus child care support. dMay Revision includes $400,000 ongoing to backfill for a reduction in federal funding. |

|||

|

Note: The administration estimated a COLA rate of 3.46 percent in January, whereas the May Revision reflects the finalized rate of 3.26 percent. |

|||

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; COLA = cost of living adjustment; and LEA = local education agency. |

|||

Adjusts Some One-Time Spending. The Governor’s budget identified $52 million in unspent funds associated with Proposition 98 programs funded in prior years. It also included a settle-up payment of $687 million related to meeting the minimum guarantee in certain years prior to 2017‑18. The May Revision identifies an additional $113 million in unspent prior-year funds (bringing the total to $165 million) and maintains the settle-up payment. Figure 4 shows how the Governor proposes to use these one-time funds. In January, the budget allocated $475 million to covering LCFF costs. The May Revision increases this amount to $619 million, including $368 million related to 2018‑19 and $251 million related to 2019‑20. The May Revision also provides a one-time property tax backfill for the San Francisco Unified School District related to a previous misallocation of local property tax revenue in 2016‑17.

Figure 4

Governor’s Spending Proposals for One‑Time Proposition 98 Funding

(In Millions)

|

Unspent Funds From Prior Years |

Settle‑Up Payment |

Total One‑Time Funds |

|

|

Governor’s Budget |

|||

|

Cover some 2018‑19 LCFF costs |

— |

$475 |

$475 |

|

Provide grants for schools with large concentrations of students with disabilities |

$9 |

178 |

187 |

|

Cover some 2019‑20 CCC Strong Workforce costs |

43 |

34 |

77 |

|

Totals |

$52 |

$687 |

$738 |

|

May Revision |

|||

|

Cover some 2018‑19 LCFF costs |

— |

$368 |

$368 |

|

Cover some 2019‑20 LCFF costs |

$152 |

98 |

251 |

|

Backfill San Francisco Unified for previous misallocation of property tax revenue |

0 |

149 |

149 |

|

Fund CCC deferred maintenance |

5 |

35 |

40 |

|

Fund Classified Employees Summer Assistance Program |

— |

36 |

36 |

|

Provide grants to Oakland Unified and Inglewood Unified |

4 |

— |

4 |

|

Backfill basic aid districts for wildfire‑related property tax losses |

2 |

— |

2 |

|

Cover some 2019‑20 CCC Strong Workforce costs |

1 |

— |

1 |

|

Provide disaster reimbursement for Child Nutrition Program |

1 |

— |

1 |

|

Totals |

$165 |

$687 |

$852 |

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula and CCC = California Community Colleges. |

|||

Assessment

Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee Are Reasonable. Estimates of General Fund revenue tend to be the most important factor affecting estimates of the minimum guarantee. Over the budget period, our estimates of revenue affecting the guarantee are about $200 million below the administration’s estimate in 2017‑18 and about $400 million above (each year) in 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. These differences are due in part to updated information available at the time we prepared our estimates as well as differences in how we model the effects of initial public offerings of California-based companies. Regarding the minimum guarantee, our estimates are identical in 2017‑18 and $250 million above the administration across 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 combined (Figure 5). These differences are relatively minor, with the largest difference ($158 million in 2018‑19) equating to about 0.2 percent of all Proposition 98 funding that year. Our estimates of local property tax revenue also are comparable, being identical in 2017‑18 and $134 million above the administration’s estimates across 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. Given the differences between the two sets of estimates are so small, we think the administration’s estimates of the minimum guarantee offer a reasonable starting point for budget deliberations.

Figure 5

Comparing Administration’s and LAO’s May Proposition 98 Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

May Revision |

|||

|

General Fund |

$52,951 |

$54,445 |

$55,904 |

|

Local property tax |

22,625 |

23,701 |

25,166 |

|

Totals |

$75,576 |

$78,146 |

$81,069 |

|

LAO Estimates |

|||

|

General Fund |

$52,951 |

$54,417 |

$56,043 |

|

Local property tax |

22,625 |

23,887 |

25,114 |

|

Totals |

$75,576 |

$78,304 |

$81,157 |

|

Difference |

|||

|

General Fund |

— |

‑$27 |

$140 |

|

Local property tax |

— |

186 |

‑52 |

|

Totals |

— |

$158 |

$88 |

Deposit Into Proposition 98 Reserve Is Important Milestone. The Proposition 2 rules for the reserve require the administration to perform a series of calculations and comparisons to determine the amount of the deposit. We think the administration’s estimate of the size of the Proposition 98 reserve deposit is consistent with its estimates of the relevant factors and the intent of Proposition 2. The deposit will provide a dedicated source of funding that can supplement the minimum guarantee in a future recession. Though a $389 million deposit is relatively small compared to the minimum guarantee, the reserve could provide fiscal relief when schools are facing greater difficulty balancing their local budgets. The deposit also complements the state’s other efforts to improve its fiscal footing, such as its deposits into reserve accounts that benefit other parts of the state budget.

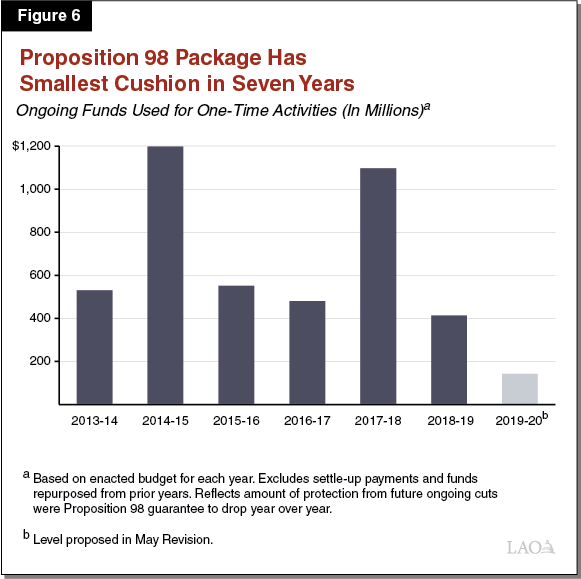

Mix of One-Time and Ongoing Proposals Moves in the Right Direction. In most years, the state budget allocates some ongoing Proposition 98 funds for one-time activities. This approach provides a buffer that reduces the likelihood of cuts to ongoing programs if the guarantee experiences a year‑over‑year decline. The Governor’s budget proposed the reverse. It relied upon nearly $80 million in one-time funds to pay for ongoing programs—effectively building a small deficit into the Proposition 98 budget for 2020‑21. The May Revision takes the positive step of eliminating this deficit. Although the May Revision relies upon about $250 million in one-time spending to pay for ongoing costs (even more than the Governor’s budget), it also contains nearly $400 million in one-time allocations (mainly the reserve deposit). Taken together—and holding all other factors constant—the Proposition 98 budget would be left with a net surplus of about $150 million entering 2020‑21.

One-Time Cushion Remains Small. Although May Revision improves upon the previous mix of one-time and ongoing spending, the $150 million cushion it contains remains relatively small (Figure 6). Over the past six years, the state has set aside an average of $700 million each year for one-time activities (excluding settle-up payments and repurposing unspent prior‑year funds). Even a modest recession could reduce the minimum guarantee by a few billion dollars—quickly depleting a $150 million cushion. As the Legislature begins developing its final budget package, we recommend shifting even more funding toward one-time activities. Such an approach would increase the state’s ability to address school funding volatility without reducing ongoing programs in the future.

Notable Concerns With Special Education Proposal, Recommend Considering Other Options. We think the design of this proposal conflicts with its intended goal of reducing the number of students identified for special education services. By providing funding in part based on the number of students identified with a disability, the proposal would reward districts that maintain above-average identification rates. Similarly, districts that managed to reduce identification rates could lose substantial funding. The May Revision exacerbates these poor incentives by providing even more funding than the Governor’s budget. Specifically, we estimate that districts eligible for the program would lose about $15,000 for each student they no longer identify for special education services. (By comparison, schools currently spend on average a little over $10,000 in local unrestricted funding per student with a disability.) As an alternative to the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature could focus on equalizing existing special education funding rates. Equalization would reduce historical funding inequities without creating incentives to over-identify students. Another option would be to modify the special education funding formula to allocate some funding specifically for preschool special education (a service schools are required to provide but for which they currently receive no dedicated state funding).

Changes to Kindergarten Facility Grants a Positive Step. When the Legislature approved the first round of kindergarten facility grants last year, its core objective was to encourage districts to convert part-day kindergarten programs to full-day programs. In light of our previous findings that the first round of grants primarily went to districts that already run full-day programs, we think the May Revision proposal to limit eligibility to districts converting their part-day programs is reasonable. We also think the May Revision proposal to lower the required local match might encourage more low-income districts to apply for these grants. Whereas these modifications seem reasonable to us, the May Revision’s proposed funding level ($600 million) still seems high. The proposed funding level assumes a high share of eligible districts will be interested in converting. Because districts face considerations beyond facilities, we think their interest level could be lower and the Legislature likely could achieve its objective with a smaller appropriation.