LAO Contact

June 14, 2019

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections)

On June 4, 2019, the administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections). Compensation costs for Unit 6 members and their managers constitute more than one-third of the state’s General Fund state employee compensation costs. This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. State Bargaining Unit 6’s current members are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). The administration has posted the agreement and a summary of the agreement on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website. (Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of this and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.)

The proposed agreement would be in effect for one year. We recommend that the Legislature consider this agreement in the broader context of the state budget because the agreement (1) has significant short- and long-term General Fund implications for the state, (2) interacts directly with the current version of the budget bill, and (3) would be a contributing factor to rising costs to administer state prisons.

Major Provisions of Proposed Agreement

Term. The agreement would be in effect for one year—from July 3, 2019 through July 2, 2020. This is the same length as the current MOU—ratified by the Legislature in 2018. The duration of this agreement is consistent with our 2007 recommendation that the Legislature not approve any proposed labor agreement with a term of more than two years.

Three Percent General Salary Increase (GSI) in 2020‑21. Under the agreement, all Unit 6 members would receive a 3 percent pay increase on July 1, 2020. Since furloughs ended in 2012‑13, Unit 6 members received pay increases in five of the past six fiscal years (see Figure 1). The MOUs that provided these past pay increases also contained concessions from employees including (1) less generous health benefits, (2) increased employee contributions towards pension benefits, (3) a new employee contribution to prefund retiree health benefits, and (3) reduced pension and retiree health benefits for future employees. Under the current MOU, Unit 6 members are scheduled to receive a 5 percent pay increase on July 1, 2019. The scheduled 5 percent pay increase in 2019‑20 and the proposed 3 percent pay increase in 2020‑21 do not appear to be accompanied with additional financial concessions from employees.

Figure 1

General Salary Increases (GSIs)

Since End of Furloughsa

|

Approved |

|

|

2013‑14 |

3% or 4%b |

|

2014‑15 |

4 |

|

2015‑16 |

3c |

|

2016‑17 |

— |

|

2017‑18 |

3 |

|

2018‑19 |

3 |

|

2019‑20 |

5 |

|

Proposed |

|

|

2020‑21 |

3% |

|

aEmployees were furloughed over five fiscal years between 2008‑09 and 2012‑13. Unit 6 member pay was reduced. The pay reduction varied over the course of the furlough period, such that Unit 6 member pay was reduced, depending on the month, anywhere between 5 percent and 14 percent. bEmployees at the top step of salary ranges received a different pay increase depending on retirement benefits. cGSI of January 2015. |

|

Leave Cash Out. The current agreement gave Unit 6 members a one-time opportunity to cash out up to 80 hours of compensable leave. The proposed agreement again would allow employees to cash out up to 80 hours of leave. As we discussed in our analysis of the current MOU, leave cash outs can reduce long-term costs for the state.

More Than Double Night Shift Differential. Under the current agreement, correctional officers who work more than four hours between the hours of 6 pm and 6 am receive a pay differential of $0.65 per hour. The proposed agreement would increase this pay differential by $0.85 per hour to $1.50 per hour—a 131 percent increase effective July 1, 2019. (The current agreement increased this shift differential by $0.15 per hour to the current $0.65 per hour—a 30 percent increase—effective July 1, 2018.)

Holiday Credit. When a holiday falls on an employee’s regular day off, the agreement would provide the employee eight hours of holiday credit. The administration indicates that this will affect the calculation used to estimate the number of relief officers that should be budgeted for in a given year. This is because the formula used by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to determine the number of relief officers incorporates the amount of leave time accrued by correctional officers. The administration estimates that the changes to this calculation would increase annual state costs by $18 million beginning in 2019‑20.

Health Benefits. The state contributes a flat dollar amount to Unit 6 members’ health benefits that was last updated in January 2019. The proposed agreement would adjust the amount of money the state pays towards these benefits in January 2020. Under the agreement, the state’s contribution would be adjusted so that the state pays a dollar amount equivalent to 80 percent of an average California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) premium cost, plus 80 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members—equivalent to what is referred to as the “80/80 formula.” The 80/80 formula is the most common type of state contribution towards state employee health benefits. The state’s contribution for Unit 6 members’ health premiums would not be increased to reflect 2021 health premiums unless provided in a future agreement.

Nearly Double Weekend Shift Differential. Under the current agreement, correctional officers who work more than four hours between midnight Friday and midnight Sunday receive a $0.80 per hour pay differential. The proposed agreement would increase this pay differential by $0.70 to $1.50 per hour—an 88 percent increase effective July 1, 2019. (The current agreement increased this shift differential by $0.15 per hour to the current $0.80 per hour—a 23 percent increase effective July 1, 2018.)

Provisions Related to Female Correctional Officers at Female Institutions. The agreement (1) makes it easier for female correctional officers to transfer to women’s prisons until the share of correctional officers at women’s prisons who are women equals 50 percent, (2) increases the number of posts for which female officers are given priority, and (3) establishes a working group that will meet quarterly to develop strategies to enhance recruitment, transfer, and retention of female correctional officers at women’s prisons. The agreement specifies that the working group will include three management employees and three rank-and-file employees. The agreement does not place requirements of the gender composition of the working group.

Correctional Counselor Work. A correctional counselor is a sworn officer who works with inmates to prepare them for reintegration into society upon release from prison. This position is one of the primary positions used in the state’s current efforts of rehabilitation in prisons. On occasion, CDCR uses correctional counselors to fill in for correctional officers to perform non-emergency assignments—for example, cell searches, yard sweeps, or escorts. The current agreement requires that such use of correctional counselors be for a “short-term.” The proposed agreement defines short-term as “less than two hours, not an entire shift, multiple days, or multiple [correctional counselors] to make up a day (e.g. each [correctional counselor] does a two-hour shift until eight hours is complete).”

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

Agreement Would Increase Ongoing Costs by $195 Million. As Figure 2 shows, if approved, the administration estimates that the agreement would increase state costs for rank-and-file Unit 6 members by as much as $112 million in 2019‑20 and state annual costs by $195 million beginning in 2021‑21.

Figure 2

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates of Proposed Unit 6 Agreement

|

Proposal |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|||

|

General Fund |

Totals |

General Fund |

Totals |

||

|

3% general salary increase |

— |

— |

$123.8 |

$126.6 |

|

|

80‑hour leave cash out |

$49.5 |

$50.6 |

— |

— |

|

|

Night shift differential increase |

24.9 |

25.5 |

24.9 |

25.5 |

|

|

Holiday credit |

17.7 |

18.1 |

17.7 |

18.1 |

|

|

Health benefits |

9.3 |

9.6 |

16.0 |

16.4 |

|

|

Weekend shift differential increase |

7.0 |

7.2 |

7.0 |

7.2 |

|

|

Other |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

|

Totals |

$109.7 |

$112.1 |

$190.8 |

$195.0 |

|

Costs to Extend Provisions to Excluded Employees. The estimates above do not include any costs resulting from the state extending provisions of the agreement to excluded employees associated with Unit 6. The administration estimates that if the provisions effective in 2019‑20 were extended to excluded employees associated with Unit 6, the state’s costs in 2019‑20 could increase as much as $19 million ($18.6 million General Fund) in 2019‑20. However, about $14 million of this is the maximum possible fiscal effect of extending the 80 hour leave cash out to excluded employees. If the 3 percent GSI were extended to excluded employees, the state’s annual costs would increase by more than $30 million beginning in 2020‑21.

Increases in Overtime Costs Resulting From GSI in 2020‑21 Not Reflected. Overtime constitutes a significant source of income for Unit 6 members. In 2018, rank-and-file Unit 6 members received more than $390 million in overtime payments. Overtime is calculated based on an employee’s regular hourly rate. It is difficult to forecast overtime utilization; however, the GSI provided by the agreement could increase overtime costs by millions of dollars.

Leave Cash Out Cost Estimate Assumes All Employees Participate. A large portion—about 45 percent—of the costs the administration identifies in 2019‑20 are attributed to the provision of the agreement that would allow employees to cash out up to 80 hours of leave. The estimated cost of $50.6 million reflects the maximum amount this provision could cost the state if all employees who are eligible chose to cash out the full 80 hours. The actual cost associated with this provision likely would be much less. For example, the current MOU includes the same provision and the leave cash outs ended up costing about one-fourth what the administration estimated when it submitted the agreement to the Legislature for ratification because most employees elected to not cash out the full 80 hours of leave.

Interactions With Budget Bill

2019‑20 Money Set Aside for New Contracts. Including Bargaining Unit 6, the state’s MOUs with 6 of its 21 bargaining units will be expired July 2019. In addition, in January 2020, the state’s MOUs with the nine bargaining units represented by Service Employees’ International Union, Local 1000 will expire. Under Item 9901, the budget sets aside $100 million ($50 million from the General Fund) in anticipation of new labor agreements in 2019‑20. The proposed trailer bill that would ratify the Unit 6 agreement (SB 103, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) would appropriate $131.2 million ($128.3 million from the General Fund) to Item 9800 to pay for the provisions of the agreement to both rank-and-file and excluded employees associated with Unit 6. As such, the $100 million set aside in Item 9901 would still be set aside for the remaining bargaining units that agree to new agreements with costs in 2019‑20.

Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Proposal. The Conference Committee budget package approved the administration’s requested $71.3 million General Fund and 280.2 positions (63 of which are correctional officer positions) in 2019‑20 and $161.9 million General Fund and an additional 150.8 positions (including an additional 63 correctional officer positions) in 2020‑21. The total 126 new correctional officer positions requested as part of this proposal is a significant increase in employees represented by Unit 6. The administration’s estimates for the cost of (1) the agreement do not take into consideration the growth in positions resulting from this proposal, and (2) the proposal does not take into consideration the growth in compensation costs provided by this agreement.

Salary Increase and Employee Compensation

No Evident Justification for Proposed Salary Increase

State Law Requires Administration to Justify GSIs with a Compensation Study. A GSI—like the 3 percent pay increase proposed by this agreement—adjusts the entire salary range for a classification such that all employees within that classification receive the pay increase. Section 19826 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR shall establish salary ranges for state classifications “based on the principle that like salaries shall be paid for comparable duties and responsibilities.” Further, the law requires that—when establishing or changing pay ranges—“consideration shall be given to the prevailing rates for comparable service in other public employment and in private business.” The law requires that at least six months before an MOU expires, CalHR submit to the union that represents the affected employees and the Legislature “a report containing the department’s findings relating to the salaries of employees in comparable occupations in private industry and other governmental entities.” If this requirement under law conflicts with provisions of a ratified MOU, the law specifies that the ratified MOU shall be controlling.

Last Unit 6 Compensation Study—From 2013—Showed CCPOA Compensated Above Market. As we indicated in our 2018 analysis of the then proposed (now the current) Unit 6 MOU, the last compensation study for Unit 6 was conducted using data from 2013. That survey determined that correctional officers represented by Unit 6 received total compensation that was 40 percent higher than their local government counterparts.

Administration Completed a 2018 Compensation Study . . . The MOU that preceded the current MOU (ratified by the Legislature in 2016, henceforth referred to as the 2016 MOU) included language related to the compensation study required by state law. Specifically, the provision required that:

Within ninety (90) days of ratification of this MOU, the parties agree to form a Joint Labor Management group who will meet to discuss the criteria, comparators and methodology to be utilized for [Bargaining Unit 6] in the next Total Compensation Report created pursuant to Government Code Section 19826. The Joint Labor Management group will be comprised of no more than two (2) representatives from each of the following: CCPOA, CalHR, CDCR and Department of Finance. The first meeting of the Joint Labor Management group will occur no later than eighteen (18) months prior to the expiration of the MOU.

Last year, CalHR informed us that (1) the administration and CCPOA met beginning August 2017 and reached a consensus on the study’s methodology by mid-October 2017, (2) the survey was mailed to six county employers in mid-October 2017, (3) CalHR completed a draft compensation report by mid-February 2018, (4) CalHR shared a draft report with CCPOA, (5) CCPOA had questions about how the agreed upon methodology was applied in the study, and (6) CalHR agreed not to submit to the Legislature the 2018 compensation study until CCPOA had completed its review.

. . . But Will Not Submit 2018 Compensation Study to the Legislature . . . CalHR and CCPOA had not resolved the outstanding issues with the 2018 compensation study before the administration submitted to the Legislature for ratification the current MOU (ratified by the Legislature in 2018, henceforth referred to as the 2018 MOU). Accordingly, CalHR did not submit to the Legislature a compensation study when it submitted the 2018 MOU. One year later, CalHR indicates that the union and administration have not resolved their differences on the compensation study and will not submit to the Legislature the 2018 study.

The administration asserts that the provision of the 2016 MOU referenced above relieved CalHR of the requirements under Section 19826 to submit a compensation report to the Legislature. We disagree with this conclusion. The provision of the ratified 2016 MOU (1) established criteria for CCPOA and the administration to meet to establish the methodologies that CalHR would use before CalHR conducted its compensation study and (2) allotted enough time—a full year—for the union and administration to meet and for CalHR to complete and submit to the union and the Legislature the study six months before the 2016 MOU expired. The provision of the 2016 MOU did not conflict with—but rather was complimentary to—the requirements under Section 19826.

. . . And Did Not Provide a 2019 Compensation Study With Agreement Now Before Legislature. The ratified 2018 MOU—the current Unit 6 agreement—specifies that the section of the 2016 MOU referenced above “will be inoperable during the term of this MOU.” With this provision of the agreement inoperable, there is no question that Section 19826 is controlling and CalHR should have submitted to the Legislature a compensation survey six months before the expiration of the 2018 MOU (meaning a study should have been submitted to the Legislature in January 2019). However, no such compensation study has been submitted to the Legislature. The administration asserts that it did not submit to the Legislature a 2019 compensation study because the parties never reached agreement on a compensation study methodology. Because Section 19826 is controlling under the 2018 MOU, whether or not the union agreed with the methodology that would be used in a 2019 compensation study is immaterial.

In Absence of Compensation Study, Administration Offers Weak Justification for Pay Increase. We asked the administration for its justification for the proposed GSI. In response, the administration asserted that the pay increase is reasonable because the agreement will (1) increase the number of posts for which female officers are given priority and make it easier for female correctional officers to transfer to women’s prisons and (2) improve rehabilitation programs by allowing correctional counselors to be more able to focus on rehabilitation and institutions to better manage rehabilitation program staff. Both of these operational improvements could be achieved without a GSI. For example, in the case of improving rehabilitation programs, the state could hire more correctional officers so fewer redirections of correctional counselors are necessary.

In addition, the administration pointed to the fact that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) West Region Consumer Price Index identified that prices in the western United States in April 2019 have increased 2.9 percent compared with April 2018. The administration suggested that this rate of inflation justified the July 2020 pay increase provided by the agreement. Pay increases provided to Unit 6 members since the last compensation study, however, have outpaced inflation. Specifically, between April 2013 and April 2019, the BLS index suggests that prices have grown 14 percent whereas the Unit 6 pay increases received during the same period equaled about 18 percent. Importantly, however, these agreements also required employees to contribute a new 4 percent of pay to prefund retiree health benefits—partially offsetting the pay increases. Looking forward, by April 2020, Unit 6 member salaries will increase an additional 5 percent while inflation is expected to increase at a slower rate. Accounting for inflation and changes in employee contributions, we believe Unit 6 members likely continue to receive higher salaries than their local government counterparts.

Without Compensation Study, Legislature Cannot Assess Need for Pay Increase. Unit 6 compensation has changed significantly since the last compensation study in 2013. These changes include lower retirement benefits for future employees, new requirements to prefund retiree health benefits, and pay increases through July 2019 compounding to more than 24 percent. We suspect that correctional officers and parole agents employed by other governmental entities also have experienced significant changes to their compensation since 2013. Based on what the administration has provided, the Legislature has no way to assess whether a 3 percent GSI is appropriate and how such a pay increase might affect the state’s position in the labor market and its ability to recruit and retain employees. That said, absent this study, we evaluate the extent to which a pay increase could be justified below.

We Find No Evidence to Justify Pay Increase. We have less than ten calendar days to complete this analysis—not enough time to do a total compensation study. However, after reviewing what data are available to us—discussed below—we think that Unit 6 compensation levels likely are sufficient to allow correctional facilities to meet personnel needs at this present time.

No Clear Recruitment Problem. Recruitment is the ability to attract new employees. We see no evidence that the current compensation structure is limiting CDCR’s ability to recruit new correctional officers. Specifically, we looked at the CDCR correctional officer academy that applicants generally must first successfully complete before becoming correctional officers. Over the past four years (including the department’s projection for 2018‑19), the academy received on average 26,000 applications each year and accepted about 7 percent of the applicants to enroll in the academy.

No Clear Retention Problem. Retention is the ability to keep experienced employees. As we discuss below, the current Unit 6 compensation seems adequate to retain experienced correctional officers not yet eligible for retirement.

- Steady Share of Mid-Career Unit 6 Members. Since 2014, the share of Unit 6 members who are mid-career—meaning, they have between 10 years and 19 years of service—has been steady at about 40 percent. As of December 2018, the administration reports that 10,507 Unit 6 members were mid-career.

- Most Officers Retire—Rather Than Resign—From State Service. Between 2014 and 2018, CDCR reports that 9,074 correctional officers separated from state employment. The primary reason for separation was retirement (68 percent of separations) where people voluntarily exit the workforce. In contrast, about 15 percent of the separations were resignations where people voluntarily leave one employer but do not exit the workforce (for example, leave an employer to work for a different employer or change career paths).

State Salaries Appear Higher Than Most Other Employers. Salaries are one element of compensation and cannot be used as the sole metric when comparing compensation across employers. A true compensation study would look at salary, health benefits, retirement benefits, and any other ancillary benefits to compare total compensation. That being said, comparing salaries alone can be informative as it is often the information most visible to outside job candidates.

- State Appears to Provide Higher Salaries Than Most Key California Counties. Because California’s correctional facilities are located throughout the state, Unit 6 members work in numerous counties across the state. However, Unit 6 employment is concentrated in some parts of the state. For example, 78 percent of Unit 6 members work in 1 of 12 counties in California—the Counties of Kern, Kings, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Riverside, Monterey, Solano, San Bernardino, Imperial, Los Angeles, Lassen, and San Diego. Based on the classification and pay range information available on these counties’ websites, the state’s current (not including the 5 percent GSI in July 2019) correctional officer salary ranges are competitive (within 5 percent) or more than 5 percent above most of the 12 counties’ comparable classifications. However, the top step of the salary ranges in the Counties of Monterey, Sacramento, and San Bernardino appear to be higher than the Unit 6 correctional officer top step (18 percent of Unit 6 members work in one of these three counties).

- California Appears to Provide Higher Salaries Than Other States. California is a high cost-of-living state. Accordingly, salaries for most occupations are higher in California than in other states. Using data from the BLS, California pays its correctional officers more than all other states. When controlling for cost of living—we used an index prepared by the Missouri Department of Economic Development—California correctional officers are the sixth highest paid in the country (behind Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Iowa). The BLS cites that fewer correctional officers will be needed across the United States due to changes in criminal laws (primarily related to reduced sentence time or an alternative to incarceration). Specifically, the BLS expects a national decline in correctional officer employment by 7 percent between 2016 and 2026, suggesting that salaries for correctional officers likely will have less pressure to increase nationally than other occupations.

Employee Compensation Drives State Prison Costs

Prison Costs Have Grown Substantially Despite Declining State Correctional Populations. Over the past decade, several policy changes have substantially reduced the state’s inmate and parolee populations in response to federal court orders requiring the state to address overcrowding in state prisons. For example, in 2011, the Legislature adopted legislation that limited who could be sent to state prison such that certain lower-level offenders serve their incarceration terms in county jail. Additionally, the legislation required that counties, rather than the state, supervise certain lower-level offenders released from state prison. Between June 2009 and June 2019, the inmate population declined from about 167,800 to 125,700 (25 percent decrease) and the parolee population declined from about 111,200 to 50,100 (55 percent decrease). Over this period, CDCR’s operational expenditures increased by about $2 billion or 19 percent—from about $10.6 billion in 2008‑09 to an estimated $12.6 billion in 2018‑19. At first glance, assuming that a reduction in inmate population would result in an overall reduction in the costs to administer state prisons would be reasonable. However, as we discus below, employee compensation costs—in particular, pension costs—have increased substantially, contributing to year-over-year growth by hundreds of millions of dollars in total state costs to administer state prisons.

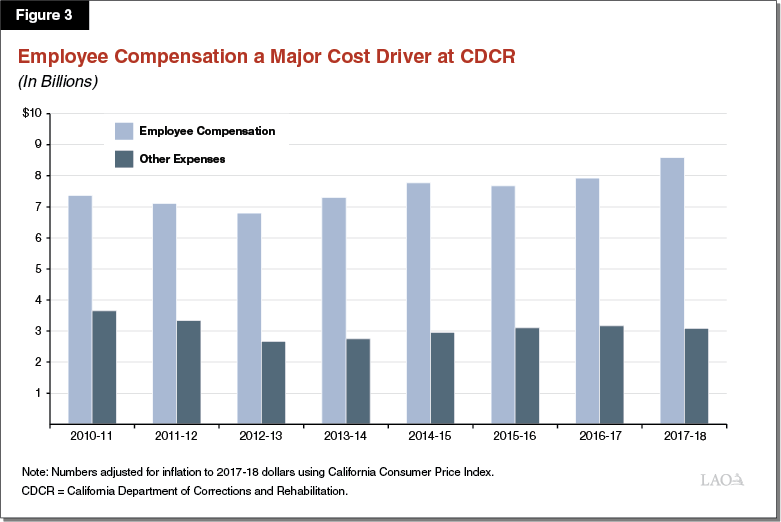

Employee Compensation a Major Cost Driver. We have identified two primary factors that have contributed to CDCR costs rising while the correctional population has declined: (1) rising employee compensation costs and (2) costs incurred to comply with federal court orders related to prison overcrowding and inmate health care. In this analysis, we will focus on employee compensation costs. Employee compensation constitutes three-fourths of CDCR’s operations budget. As Figure 3 shows, after controlling for inflation, CDCR employee compensation costs have increased while other expenses have decreased relative to 2010‑11.

Pension Benefit Costs Have Increased Sharply . . . One of the primary elements of employee compensation that has increased CDCR costs over the past decade is rising pension contribution rates to CalPERS. The state’s contributions to CalPERS are established by the CalPERS board as a percentage of pay. Part of the state’s contribution goes towards the “normal cost”—the amount of money that actuaries determine is necessary (combined with assumed future investment earnings) to pay the cost of pension benefits that employees earn in a given year. The normal cost typically does not change from one year to another unless benefits change or the CalPERS board adopts new assumptions that materially affect the amount of money that must be set aside to fund benefits earned today. To the extent that actuaries determine that assets in the pension fund from past contributions are insufficient to pay for benefits earned by employees, an “unfunded liability” exists. The state’s CalPERS unfunded liabilities have grown substantially since the Great Recession through a combination of (1) lower-than-assumed market returns and (2) new actuarial assumptions (specifically, the pension system now assumes that future returns will be lower and that retirees will live longer than was previously assumed). As a result of these unfunded liabilities, the state’s contribution rates to pay for Unit 6 members’ pensions have grown from 29 percent of pay in 2010‑11to 49 percent of pay in 2019‑20.

. . . Compounded by Salary Growth. Because the state’s contributions towards employees’ pension benefits are determined as a percentage of pay, any growth in pay increases the dollar amount that the state must contribute. Further, the CalPERS board assumes that payroll will grow 3 percent each year. To the extent that past pay increases resulted in payroll growing faster than 3 percent, the faster-than-assumed payroll growth would create an unfunded liability that would increase future state contribution rates.

Absent New Agreement, Prison Employee Compensation Costs Will Rise. CalPERS projects that the state’s contribution rates to fund correctional officers’ pensions will increase each year until 2023‑24, when it is expected that the state’s contribution rate will exceed 52 percent of pay. With the current labor agreement providing Unit 6 employees a 5 percent GSI July 1, 2019, the state’s contribution rate to CalPERS may increase above what is currently projected to the extent that the pay increase results in payroll growing faster than 3 percent. Consequently, even if the Legislature rejects the proposed agreement, the state’s costs to staff prison and parole operations will rise by hundreds of millions of dollars over the next few years. If the Legislature ratified the agreement, the state’s prison costs would increase even further (absent any major policy decisions reducing the number of correctional staff).

Female Correctional Officers

Separate Prisons Designated for Men and Women. The state operates 35 state prisons. In 2019‑20, the average daily prison population is projected to consist of 120,211 male inmates and 5,660 female inmates—meaning females are projected to account for less than 5 percent of the population. The majority of female inmates are housed at one of three women’s prisons in the state. At women’s prisons, the ratio of male to female correctional officers is about 70 male correctional officers to 30 female correctional officers.

New State Law Limits Use of Male Officers at Female Institutions. In 2018, the Legislature approved and the Governor signed AB 2550 (Weber), adding Section 2644 of the Penal Code. This law seeks to protect female inmates from sexual assault, abuse, and other improper contact with male correctional officers. Specifically, the law prohibits—except in specified emergency situations—male correctional officers from (1) conducting a pat down search of a female inmate, (2) entering an area where female inmates may be in a state of undress, or (3) being in an area where they can view female inmates in a state of undress.

Few Women Correctional Officers. The profession of correctional officer historically has been dominated by men. Since 2003, the share of Unit 6 members who are women has declined. Specifically, whereas 21 percent of Unit 6 members were women in 2003, 18 percent of Unit 6 members were women in 2018. The administration indicates that about 25 percent of people currently enrolled in the CDCR academy are women. In order to comply with AB 2550, CDCR likely needs to recruit additional women correctional officers to work in its women’s prisons. That being said, we do not know what is the necessary ratio of women to men correctional officers at female institutions in order to comply with AB 2550. While the law likely requires a non-trivial portion of posts at women’s prisons to be filled by female correctional officers (including posts located inside dormitories and at areas where pat downs might occur) there are a variety of posts (such as providing perimeter security) that could still be filled by male correctional officers.

Working Group Should Include Women. The agreement would establish a working group to develop strategies to enhance recruitment, transfer, and retention of female staff at women’s prisons. As mentioned earlier, the agreement does not require any working group members to be women. In order for the working group to be most helpful in developing strategies that work, the committee likely should include several women.

No Change to Retiree Health Prefunding Contributions

Stated Goal Is for State and Employees to Each Pay One-Half of Normal Cost. The 2016 MOU established that the state and employees each would contribute 4 percent of pay beginning 2018‑19 to fund retiree health care, with the goal that the contributions (totaling 8 percent) would equal the “actuarially determined total normal cost.” As we discuss below, since that time, normal cost for retiree health benefits has grown. While the proposed agreement maintains the goal of the 2016 MOU, it maintains the same contribution rates, despite the growth in normal cost. The administration indicates that actuarially determined total normal cost might be equivalent to 8.3 percent of pay. Accordingly, the state and employees may be paying less than what is necessary to pay the full actuarially determined total normal cost by about $10 million. By this measure, employees and the state each should contribute 4.15 percent of pay rather than 4 percent of pay. While the administration might consider 0.15 percent of pay to be too small to warrant the negotiations necessary to implement it for a one-year agreement, any amount of normal cost not paid in a given year contributes to the state’s unfunded liabilities.

Given the policy was implemented only a few years ago, the state should not create any doubt that the full normal cost will be paid each year. In the actuarial valuation of the state’s retiree health liabilities, actuaries assume that the state’s “prefunding policy provides for a 50 percent cost sharing of the normal cost, between active members and [the state].” The effect on the assessment of the state’s unfunded liability is unclear if actuaries have reason to believe this is not the state’s prefunding policy.

Normal Cost Grows Each Year, but Not Necessarily at Same Pace as Salaries. When the previous administration first introduced its proposal that the state establish through collective bargaining a policy whereby the state and employees share normal cost of retiree health benefits, the administration provided to us an actuarial valuation of retiree health benefits by bargaining unit (including rank-and-file and associated excluded employees). At the time—using a valuation as of June 30, 2014—the normal cost for Unit 6—was estimated to be $185.5 million. In a subsequent valuation that the administration provided to us (as of June 30, 2015), the normal cost for Unit 6 was estimated to be $198.9 million. We do not have a bargaining unit specific valuation for 2016; however, the past two valuations released by the State Controller’s Office (SCO) indicate that the Unit 6 normal cost was $227.4 million as of June 30, 2017 and $233.7 million as of June 30, 2018. Based on these data points, the normal cost for retiree health benefits grew 26 percent between 2014 and 2018—and year-over-year growth in normal cost can vary significantly as it grew 7 percent between 2014 and 2015, and 3 percent between 2017 and 2018. Actuarially determined normal cost is driven by numerous factors—none of which are salaries and most of which are beyond the state’s control—such as the benefit design and actuarial assumptions pertaining to health care inflation, utilization, demographic trends, investment return, and other assumptions.

To Maintain Goal, Rates Would Need to Be Reviewed Each Bargaining Cycle. Normal cost of retiree health benefits is a moving target that can fluctuate each year. As such, in order to consistently maintain a policy whereby the state and employees each contribute one-half of normal cost established as a percentage of pay, the exact rate that the parties pay would have to be reviewed each bargaining cycle. Aside from the practical difficulties of including this component of compensation in the discussion each bargaining cycle, determining the correct rates also can be difficult from a technical perspective. The numerous factors involved in determining normal cost can make it difficult to forecast future normal costs. Further, the timing of when SCO releases the most recent actuarial valuation does not take into consideration the bargaining cycle. (For example, the most recent valuation was released in mid-May after CCPOA and the state had already been bargaining for at least a month.) Consequently, ensuring that the rates in a bargaining agreement—especially if the agreement were a multiyear agreement—will result in employees and the state each paying one-half of the normal cost is difficult. In all likelihood, in some years, the state and employees will pay more than one-half of normal cost and in other years they will pay less.

Creates Artificial Pressure on Salaries. The amount of money that employees contribute to prefund retiree health benefits directly reduces the amount of money that employees take home. As we have discussed in the past (see past analyses here and here), these types of cost-sharing arrangements often result in employees receiving a pay increase that offsets their contribution increases. The pressure for the state to increase salaries in these cases obscures economic and labor market factors that should be the primary reasons for determining compensation increases. Increasing salaries to offset employee contributions results in the state (1) paying more than if the state paid the entire cost itself since each additional dollar of salary increases salary-driven benefit cost—like contributions towards pensions and Medicare and (2) basing decisions to provide GSIs on an arbitrary policy of equal cost sharing that is difficult to actually maintain.

Rather Than Provide 3 Percent GSI, State Could Eliminate Employee Retiree Health Prefunding Contribution. The state and employees deserve credit for recognizing that addressing retiree health unfunded liabilities is important. That being said, the current arrangement of establishing—as a percentage of pay—the amount of money that is contributed each year to prefund this benefit is unnecessarily complicated, unnecessarily expensive, and creates risk that the total amount of money contributed to prefunding the benefit might not actually equal the full normal cost. A simpler and less expensive option would be for the state to agree through the collective bargaining process that the state will pay the full normal cost in the budget act as determined by the most recent actuarial valuation. This would allow employees to hold the state accountable to ensure that the benefit they are earning is being funded while relieving pressure at the bargaining table for employees to receive GSIs in the future when normal cost grows.

In the case of the Unit 6 agreement before the Legislature, the total cost of the 3 percent GSI in 2020‑21—after extending it to excluded employees—would exceed $150 million each year. Further, by increasing salaries, the GSI would increase pension liabilities going forward. If, rather than providing a 3 percent GSI, the state eliminated the requirement that employees pay 4 percent of pay to prefund retiree health benefits and the state committed to pay the full normal cost, the state’s costs would increase about the same (possibly less) amount as under the proposed agreement but (1) employees would experience a 4 percent growth in their take home pay rather than 3 percent, (2) the state’s pension liabilities would be unaffected, and (3) the state would be on track to fully prefund retiree health benefits.