LAO Contact

June 26, 2019

The California State Bar:

Considerations for a Fee Increase

- Introduction

- Background

- State Bar Request for Fee Increase

- Assessment of State Bar Budgeting Process

- Assessment of Request for Fee Increase

- Alternative Fee Increase Options

- Other Issue for Legislative Consideration

- Conclusion

- Appendix A— Examples of Base Licensing Fees for Active Members of Selected Professions

- Appendix B— Summary of Major State Auditor Recommendations

- Appendix C— A Comparison of Disciplinary Processes

Executive Summary

This report presents our assessment of the State Bar as required by Business and Professions Code Section 6145. Specifically, our analysis focuses on evaluating the portion of the annual licensing fee charged to attorneys that is deposited into the State Bar’s General Fund and the State Bar’s request for a fee increase in 2020.

State Bar Licenses Attorneys and Regulates Their Professional Conduct. The State Bar functions as the administrative arm of the Supreme Court for the purpose of admitting individuals to practice law in California as well as regulating the professional conduct of attorneys by adopting rules of professional conduct and enforcing them through the administration of its own disciplinary system. As of June 2019, there are more than 270,000 members of the State Bar—of which about 190,000 (70 percent) are active members able to practice law in California.

State Bar Assesses Fees to Support Its Activities. State Bar activities generally are funded by various fees paid by attorneys for deposit into specific funds to benefit specific programs. In 2019, the total maximum annual fee paid by active members is $430. Of this amount, $333 supports the General Fund, which is used to fund most of the State Bar’s operations. In 2019 (the State Bar operates on a January through December fiscal year), the State Bar budget assumes that the portion of the licensing fee deposited into the General Fund will generate $67 million (about 84 percent of total General Fund revenues).

State Bar Request for Fee Increase. The State Bar seeks an ongoing $100 fee increase and a one‑time $250 assessment from its active members beginning January 1, 2020. The State Bar seeks these increases to address the following:

- Proposed Ongoing Fee Increase. The $100 ongoing fee increase includes: (1) $30 to address an operating deficit in which estimated expenditures exceed estimated revenues, (2) $30 to support the extension of retiree health benefits currently available only to executive employees to all State Bar employees and a salary increase for represented employees, and (3) $40 to support the hiring of 58 additional staff to improve disciplinary case processing times. The State Bar also requests the authority to adjust the entire renewal fee and the existing $25 disciplinary fee annually to account for inflation.

- Proposed One‑Time Fee Increase. The one‑time $250 assessment seeks to cover five years of project costs and includes: (1) $134 to support building improvement costs for five years, (2) $82 to support technology project costs for five years, and (3) $34 to restore the State Bar’s budget reserve level back to 17 percent.

Assessment of State Bar Request. Our review of the State Bar focuses on three major areas.

- State Bar Budgeting Process. The State Bar’s existing budgeting process generally limits legislative oversight as it is not required to go through the state’s annual budget process. This gives the State Bar more flexibility in its budgeting practices than other similar state licensing agencies. Additionally, the Legislature is not directly involved in major policy decisions that may have long‑term cost implications. Finally, the State Bar consistently approves budgets where its General Fund expenditures exceed its revenues.

- Proposed Ongoing Fee Increase. Portions of the proposed ongoing fee increase seem reasonable, while others raise concerns. Specifically, providing an ongoing fee increase to address (1) an operating deficit and (2) a salary increase for represented employees seems reasonable. In contrast, the State Bar’s proposed extension of retiree health benefits is a policy decision that is out of step with other public employers. Additionally, the request for additional disciplinary staff may be premature. Finally, the request for an annual inflationary adjustment lacks justification and could limit legislative oversight.

- Proposed One‑Time Fee Increase. While the projects that would be addressed by the one‑time assessment merit consideration, there is a lack of justification for providing five years of costs in 2020. Additionally, it is not clear why certain costs are considered one time instead of ongoing.

Alternative Fee Increase Options. We provide various alternative fee increase options for legislative consideration. The Legislature can select from these options, or others (such as those offered by the California State Auditor) to calculate the total ongoing and one‑time fee increase that best reflects legislative priorities.

Consider Appropriate Level of Legislative Oversight. Regardless of what fee level ultimately is approved by the Legislature, our review of the State Bar indicates that increased legislative oversight could be beneficial to ensure (1) that fee revenues are assessed appropriately to support expenditures that are consistent with legislative expectations and priorities and (2) that funds are used in an accountable and transparent manner. Such oversight can occur in various ways—such as including the State Bar in the annual budgeting process and/or requiring reporting on various performance or outcome measures.

Introduction

Section 6145 of the Business and Professions Code, as amended by AB 3249 (Chapter 659 of 2018, Committee on Judiciary), requires two assessments of the State Bar of California—one assessment from the California State Auditor’s Office (State Auditor) and one from our office. The State Auditor released its report on April 30, 2019. This report presents our assessment pursuant to this section of law.

Our analysis focuses on evaluating the State Bar’s General Fund portion of the annual fee charged to attorneys. (The nearby box shows the fees we examine compared with those examined by the State Auditor.) In this report, we first provide background on the State Bar and its operations. We then assess the State Bar’s proposal to increase the fees paid by attorneys in 2020. Finally, we provide the Legislature with alternative fee increase options as well as some other issues related to State Bar budgeting for legislative consideration.

LAO Analysis Focuses on Subset of Total State Bar Fees Examined by the State Auditor

The State Auditor report examined all State Bar mandatory fees as well as the State Bar’s proposal for an increase to mandatory State Bar fees. In comparison, our report focuses on the General Fund portion of the mandatory fee charged to attorneys. The figure highlights the specific subset of fees examined by our report relative to those examined by the State Auditor.

Comparison of Active Licensee Fees Examined by the State Auditor and in This Report

|

Fee |

2019 Fee Amount |

2020 State Bar Proposal |

Examined by the State Auditor |

Examined in This Report |

|

Mandatory Ongoing Fee |

||||

|

Licensing |

$308a |

$408b |

x |

x |

|

Discipline |

25 |

25 |

x |

x |

|

Client Security Fund |

40 |

40 |

x |

|

|

Lawyer Assistance Program |

10 |

10 |

x |

|

|

Subtotals |

($383) |

($483) |

||

|

Mandatory One‑Time Fee |

||||

|

Client Security Fund |

— |

$80 |

x |

|

|

Building Improvements |

— |

134 |

x |

x |

|

Technology Projects |

— |

82 |

x |

x |

|

Rebuilding Reserve |

— |

34 |

x |

x |

|

Subtotals |

(—) |

($330) |

||

|

Voluntary Fees |

||||

|

Legal Services Trust Fund |

$40 |

$40 |

||

|

Legislative Activitya,b |

5 |

5 |

||

|

Elimination of Bias Programsa,b |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Subtotals |

($47) |

($47) |

||

|

Total Fees That May Be Charged |

$430 |

$860 |

||

|

aState law authorizes a $315 annual license fee for active licensees. Existing law allows active licensees to deduct $7 from this amount—$5 if they do not want to fund State Bar legislative activity and $2 if they do not want to fund elimination of bias programs in the legal profession and justice system. bSimilar to the 2019 fee amount, $7 may be deducted. |

||||

Background

What Is the State Bar?

Licenses Attorneys and Regulates the Profession and Practice of Law in California. The California Constitution requires attorneys to be members of the State Bar to practice law in the state. The California Supreme Court has the power to regulate the practice of law in the state—including establishing criteria for admission to the State Bar and disbarment. The State Bar of California functions as the administrative arm of the Supreme Court for the purpose of admitting individuals to practice law in California and regulating the professional conduct of attorneys by adopting and enforcing rules of professional conduct. The State Bar is established by the California Constitution as a public corporation. The State Bar currently is governed by a 13‑member board of trustees (the board). As of June 2019, there are more than 270,000 members of the State Bar—of which about 190,000 (70 percent) are active members able to practice law in California.

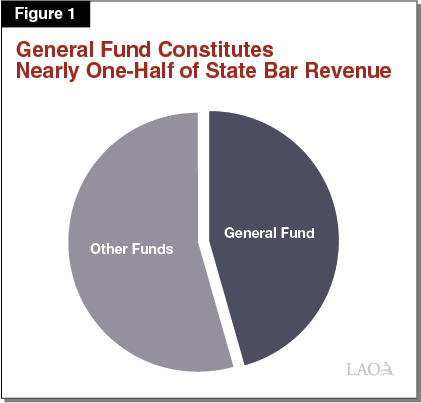

Assesses Fees to Support Activities. State Bar activities generally are funded by fees paid by attorneys. As Figure 1 shows, the State Bar’s General Fund—primarily supported by the annual mandatory licensing fee—constitutes nearly one‑half of the State Bar’s revenue. The General Fund is used to support most of the State Bar’s operations—for example, the General Fund supports 85 percent of the State Bar’s personnel expenditures. In addition to the General Fund, the State Bar has various special funds that support specific programs administered by the State Bar. (For example, the fee collected for the Client Security Fund is used to provide reimbursements to clients who suffer financial losses due to attorney misconduct.) The State Bar approved a 2019 calendar year budget estimating revenues of $168 million ($77 million to the State Bar’s General Fund) and expenditures of $189 million ($87 million from the General Fund). The approved 2019 budget would require the State Bar to use $10 million of the estimated $22 million reserves it carried into 2019.

How Does the State Bar Oversee Attorney Conduct?

California Attorneys Required to Meet Various Professional and Ethical Requirements. California—similar to other states—has various professional and ethical requirements for attorneys practicing law in the state. Examples of such requirements include: providing competent service to existing and former clients, prohibiting false or misleading communication or advertising of legal services, and keeping certain information provided by clients confidential. These requirements are outlined in state law, California Rules of Court, rules approved by the board, and the California Rules of Professional Conduct. Claims of misconduct by attorneys are adjudicated by the State Bar.

Overview of Process and Workload

Overview of State Bar Disciplinary Process. The State Bar administers its own disciplinary system primarily through its Office of the Chief Trial Counsel (OCTC) and the State Bar Court (SBC). The OCTC—consisting of teams of attorneys, investigators, and other legal administrative staff—receives, investigates, and prosecutes cases against attorneys. The SBC—consisting of judges, attorneys, and other legal and administrative staff—adjudicates these cases. Various other State Bar departments—such as the Probation Department that supervises attorneys who are required to comply with certain conditions by the State Bar Court or the Supreme Court—also support the disciplinary system.

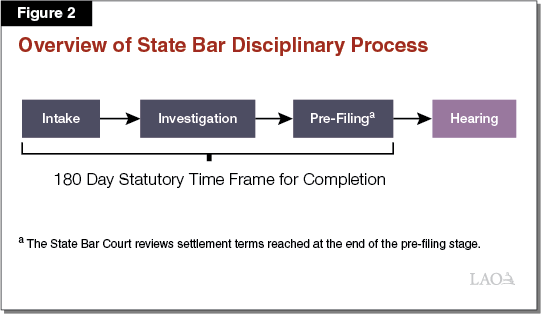

As shown in Figure 2, the disciplinary system consists of four stages. We describe each of these stages in greater detail below.

- Intake Stage. The Intake Stage—also referred to as the Inquiry Stage—generally begins with a written complaint filed with OCTC. The State Bar also may initiate its own investigations against attorneys. After an initial review, OCTC will either close the complaint (for example, notifying the complainant that no action is to be taken or issuing a warning letter to the accused attorney) or refer the case for investigation.

- Investigation Stage. The Investigation Stage consists of OCTC investigators, under the guidance and supervision of OCTC attorneys, analyzing the case through interviews, document review, and other activities to determine whether there is clear and convincing evidence that attorney misconduct has occurred or if the case should be closed (for example, notifying the complainant that no action is to be taken or reaching an agreement in lieu of discipline for low level violations).

- Pre‑Filing Stage. The Pre‑Filing Stage begins with OCTC evaluating the evidence collected in the investigation stage as well as internally documenting potential charges and appropriate levels of discipline to seek. If OCTC determines there is sufficient evidence to file charges against an accused attorney, OCTC will notify the attorney in writing of their intent to file formal charges with SBC. The attorney and OCTC may then try to resolve the case by negotiating a settlement agreement.

- Hearing Stage. If the case is not settled, the Hearing Stage begins with the formal filing of disciplinary charges with the SBC. The SBC’s Hearing Department adjudicates the case and imposes the appropriate level of discipline—which can include case dismissal, public or private reprovals, probation, suspension, and disbarment. (The SBC also reviews settlement terms reached at the end of the pre‑filing stage.) For cases where the proposed discipline involves the suspension or disbarment of the attorney, the California Supreme Court reviews the SBC’s findings and recommended disciplinary action and issues a final order.

Cost of Disciplinary System. The State Bar reports it cost $70 million from its General Fund to operate its entire disciplinary system in 2018—approximately 84 percent of the total 2018 State Bar General Fund expenditures. Of this amount, $45.4 million (or 65 percent) supported about 250 positions in OCTC and $12 million (or 17 percent) supported about 43 positions in SBC. The remaining 18 percent supported various other departments involved with the disciplinary system.

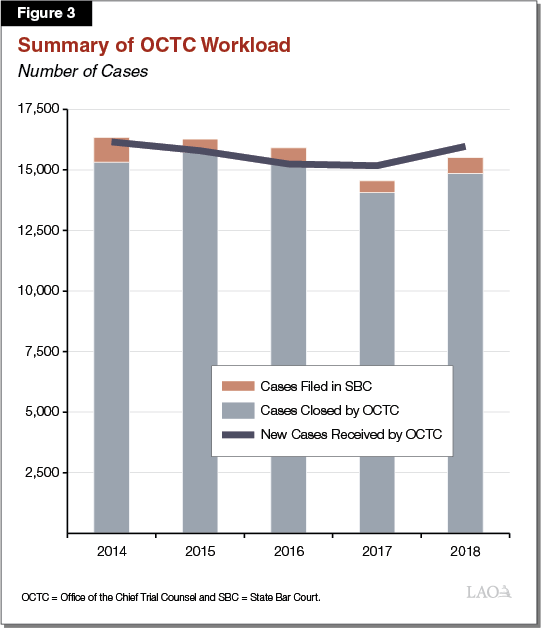

Disciplinary System Workload. As shown in Figure 3, the number of cases received and closed annually by OCTC has fluctuated slightly in recent years. Specifically, OCTC received a total of 15,973 cases in 2018 and closed 14,855 cases in 2018. Of the total number of cases closed, 13,168 cases (or nearly 89 percent) were closed without OCTC taking any action on the case. Additionally, OCTC filed 649 cases in the SBC.

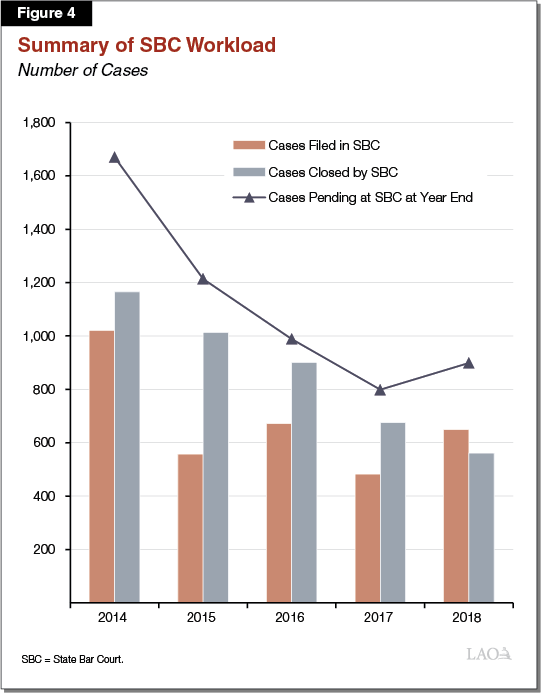

As shown in Figure 4, the number of cases received and closed annually by SBC has declined in recent years. Specifically, SBC received a total of 649 cases in 2018—a decline of 36 percent from 2014. At the same time, the SBC closed 562 cases in 2018—a decline of 52 percent from 2014. Of this amount, about 77 percent were closed with SBC imposing disciplinary action. Finally, SBC had a total of 899 pending cases at the end of 2018—a decline of about 46 percent from 2014.

Case Processing Time Frame Established by Statute for OCTC Workload. State law currently requires the State Bar to complete the first three stages of the disciplinary process (shown in Figure 2)—specifically for OCTC to dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney—within six months (or 180 days) after receipt of a written complaint. (State law extends this statutory requirement to 12 months for those complaints designated as “complicated” by the Chief Trial Counsel. However, the State Bar indicates it does not make use of this extended time frame as state law encourages adherence to the six month time frame.)

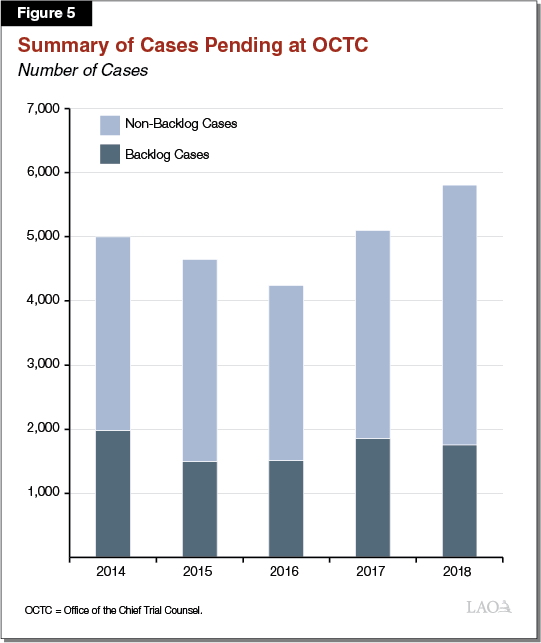

As shown in Figure 5, OCTC had 5,803 cases pending at the end of 2018—an increase of about 14 percent from 2017. Of this amount, 1,759 cases (about 30 percent) were backlogged cases—a decrease of 5 percent from 2017. Backlogged cases are cases that exceed the 180 day statutory time frame as of December 31.

Recent Changes to Improve Process and Workload

Various Changes to Improve Case Processing Times. To help improve disciplinary case processing times and reduce the number of backlogged cases, the State Bar recently implemented various changes. We discuss the major changes below.

- New OCTC Team Structure. In April 2017, the State Bar completed a significant restructuring of OCTC. Prior to this date, OCTC enforcement teams of attorneys and investigators specialized in processing specific types of complaints. The management structure, however, did not reflect this specialization‑based system. This old structure resulted in some challenges—such as disproportional staff caseloads, conflicting instructions, and a lack of clear supervisorial direction—that the State Bar believed made case processing less efficient and timely. The new structure involves most enforcement teams becoming generalist teams capable of processing nearly all complaint types. Additionally, each enforcement team now consists of attorneys, investigators, and support staff that report to a single supervising attorney. The State Bar hopes that this new structure will improve case processing times by streamlining the disciplinary process, providing a clear and simplified supervisory structure, and cross‑training staff to handle a greater range of workload.

- New Case Prioritization Methodology. In May 2018, the State Bar began implementing a new case prioritization methodology. Rather than focusing on the oldest cases first, the new methodology prioritizes cases with the greatest potential impact on members of the public. Specifically, the State Bar established three priority categories. Priority One matters involve serious misconduct or other behavior with the potential for significant or ongoing harm to members of the public. Priority Two matters involve cases that are easily resolved or identified as needing quick (or “expedited”) investigation to determine if significant harm could occur. According to the State Bar, Priority Two cases will be expedited by eliminating certain OCTC tasks. Priority Three cases consist of all other cases. The State Bar expects that all Priority One and Two cases will be completed within the 180 day statutory time frame, while the backlog will consist of mainly Priority Three cases that will be processed in order of receipt.

- New Case Management System. The State Bar completed the implementation of a new case management information technology (IT) system for the disciplinary process in February 2019. The State Bar expects this modern case management system to help improve case processing times by automating and standardizing processes to enable staff to be redirected to other case processing tasks. Additionally, the new system is expected to improve data sharing within the State Bar and its stakeholders, increase public access to information, and improve the collection and reporting of data on key metrics.

Workload Study Implemented and Used to Identify Staffing Need. In September 2018, the State Bar implemented a workload study to identify the staffing needs for its disciplinary system. For OCTC, the State Bar used a random moment time‑study methodology—similar to one used by the judicial branch—to identify all staff activities required to process a case as well as the amount of staff time associated with these activities. The State Bar then used these data to calculate “case weights” that represent the average amount of staff time each component of a case is expected to take. For example, the State Bar calculated that intake activities average 110 minutes per case while enforcement activities average 3,332 minutes per case.

The State Bar then examined historical data to identify patterns between the number of filled OCTC positions and the median amount of time required to close a case (disposition time). From this analysis, the State Bar determined that each additional filled investigator position is associated with a decrease of 3.6 days in the median case disposition time. The State Bar used this relationship to calculate that 15 additional investigator positions would be needed to meet the 180 day time frame. They then calculated the number of other OCTC staff needed based on staffing ratios (such as a staffing ratio of 1.4 attorneys for every investigator). In total, the workload study determined OCTC required 58 additional positions (above the 2018 budget positions) to meet the 180 day time frame for most cases.

How Are State Bar Activities Funded?

State Bar Revenues Determined Through Legislative Process, but Budget Is Not. Each year, the judiciary policy committees of the Legislature set the license fees charged to members of the State Bar for the coming year through the annual “fee bill.” In addition, the California Supreme Court has authority to set the license fees when a fee bill is not enacted into law. Under current law, either the Legislature or the Supreme Court must approve these fees each year or else the State Bar does not have authority to levy the fees on its members. In contrast, the State Bar’s budget is approved by the board and is not considered by the Legislature’s budget committees through the annual state budget process. This is different than nearly all other state licensing entities that regulate other professions. In most cases, these entities have their fee structure (such as fee levels) as well as proposed expenditure levels approved by the Legislature and the Governor. These entities generally need to provide written budgetary justification for any substantive changes to existing budget levels (such as to cover increased costs of operations or to support new activities) as well as explain why increased revenues are needed to support these costs.

Mandatory License Fee Is Largest General Fund Revenue Source. In 2019, the total maximum annual fee paid by active members is $430 (attorneys with an inactive status pay $155). This total consists of different fees that benefit specific funds operated by the State Bar for specific programs. Of total fees paid by attorneys, $333 supports the General Fund ($93 for inactive status attorneys). The largest fee is the base licensing fee—also referred to as the mandatory licensing fee—of $315, all of which goes to the General Fund. Members may deduct $7 from this fee if they do not want to support State Bar legislative activities or elimination of bias activities. (For context, Appendix A provides a comparison of this base licensing fee for attorneys to a selection of other professions in California.) In 2019 (the State Bar operates on a January through December fiscal year), the State Bar budget assumes that the General Fund portion of the mandatory license fee generates $67 million (about 84 percent of the total General Fund revenues).

State Bar Projections of Mandatory License Fee Revenue Based on Number of Lawyers It Anticipates. Fee revenues are a function of (1) the fees charged and (2) the number of licensees paying the fees. In the past, the State Bar projected its revenues by simply applying a growth factor to the total fee revenues received in the past. The State Bar recently changed its methodology so that it now projects fee revenues by first projecting the number of licensees it expects will pay fees in the future. Based on these projections, absent a fee increase, the State Bar projects that its fee revenues will increase by roughly one‑half of 1 percent each year.

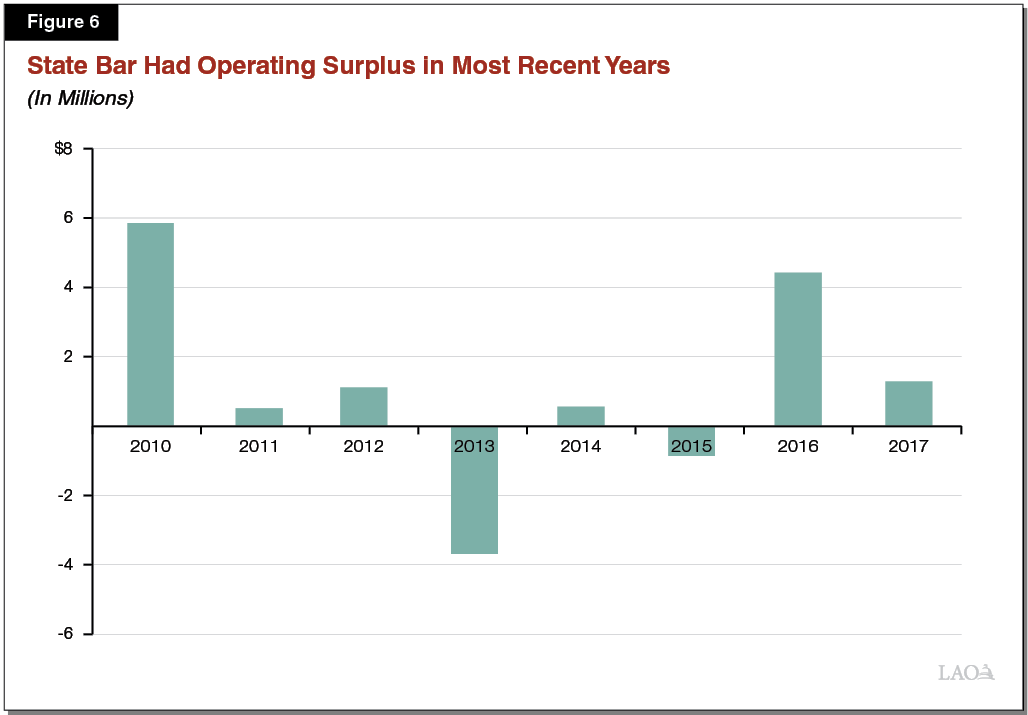

State Bar Has Had Operating Surplus In Recent Years . . . As Figure 6 shows, the State Bar has had an operating surplus in six of the eight years between 2010 and 2017. These surpluses were the result of (1) actual revenues being, on average, 1.5 percent higher than the board‑approved budgets assumed and (2) actual expenditures being, on average, 13 percent lower than the budgets assumed. In 2013, the State Bar incurred significant costs related to the new Los Angeles building, resulting in a significant operating deficit and use of reserves in that year.

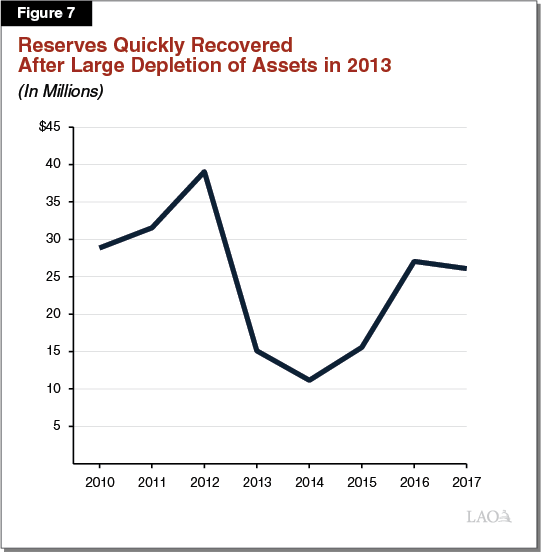

. . . Resulting in Strong Reserve Levels in Recent Years. The board has a policy that the State Bar maintain a minimum reserve equaling at least 17 percent of its expenditures—this constitutes about two months’ worth of expenditures. With most of the recent years ending with operating surpluses, the State Bar’s reserves have grown in most years. As Figure 7 shows, a notable exception to the State Bar having stable or growing reserves is in 2013 when reserves declined from $39 million to $15 million when State Bar resources were used to purchase its new building in Los Angeles. Between 2010 and 2017, the State Bar maintained a reserve above the minimum 17 percent in each year except 2014.

Beginning in 2018, State Bar Identifies Structural Deficit. The State Bar estimates that it closed 2018 with a deficit of $5.3 million. The State Bar indicates that this deficit is structural and will be ongoing—resulting in the reserves being entirely depleted before 2021 without a change in policy. The primary cause of the structural deficit appears to be rising employee compensation costs. Specifically, as we will discuss in greater detail in the next section of this report, the current labor agreements provide employees pay increases in 2018 and 2020. By 2020—after the pay increases are implemented—the State Bar indicates that its structural deficit will have increased to nearly $11 million, leaving less than $1 million in reserve.

What Are the Major Cost Drivers for State Bar?

Employee Compensation

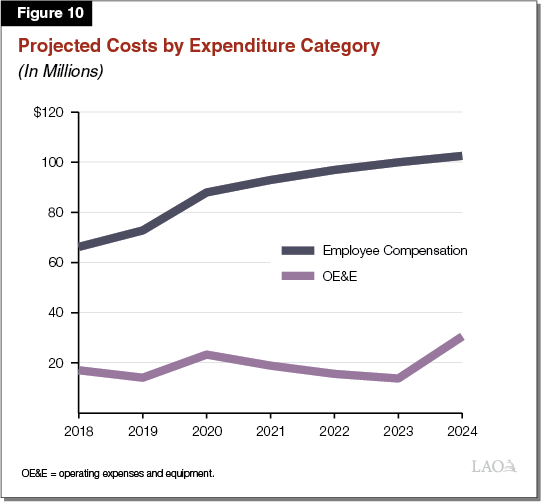

Largest Category of Spending Is Employee Compensation. As is the case with most state departments, the largest category of expenditure in the State Bar General Fund budget pays for employee compensation. Specifically, of the $87 million of expenditures approved in the 2019 State Bar budget, $73 million—or 84 percent—is assumed to go towards employee compensation costs. These costs include costs for employee salaries, active and retiree health benefits, and pension benefits. By 2024, the State Bar projects that its employee compensation costs will increase by about 40 percent to $103 million. As we will discuss in greater detail later, these increased costs are in part due to the State Bar’s request that the Legislature increase its annual fees to pay for 58 new positions.

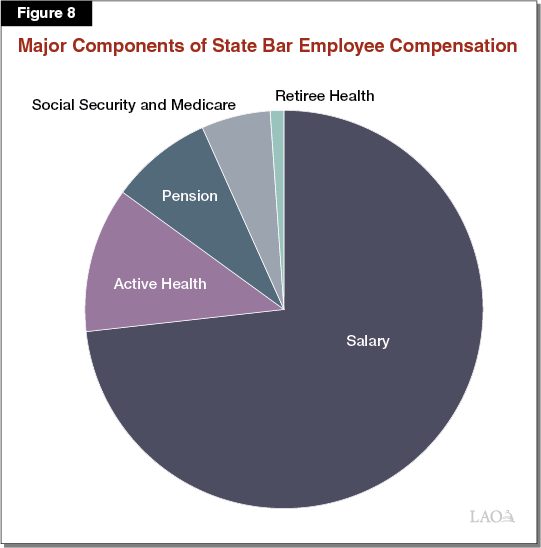

Major Components of Employee Compensation. As Figure 8 illustrates, the major components of employee compensation costs in 2019 at the State Bar include salary, employer contributions towards CalPERS health premiums for active employees, employer contributions to pension benefits administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), federal payroll taxes towards the Social Security and Medicare programs, and employer contributions towards retiree health benefits. Some of these costs—those associated with pensions, Social Security, and Medicare—are “salary‑driven” costs, meaning that these costs increase when salary increases. In contrast, active and retiree health costs are driven by the growth in health premiums and the number of people receiving the benefit.

Labor Agreements Provide Pay Increases to Rank‑and‑File Employees. Similar to the state, rank‑and‑file employee (generally, employees who are not executives or managers) compensation at the State Bar is established through collective bargaining. Unlike other state departments, however, the Legislature does not play a direct role in the ratification of these labor agreements. Instead, State Bar staff negotiate and the board approves labor agreements. (In contrast, for state employees, the California Department of Human Resources represents the Governor in negotiations with labor unions. Before the labor agreement goes into effect, it must first be ratified by the Legislature.)

State Bar rank‑and‑file employees are organized into two bargaining units—one represents attorneys and the other represents other rank‑and‑file employees. The rank‑and‑file employees are represented at the bargaining table by Service Employees International, Local 1000—the largest state employee union. The current labor agreements are in effect from January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2019. The agreements provided employees a 3.6 percent pay increase effective January 1, 2018. In addition, the agreements provide employees a 3.5 percent pay increase on January 1, 2020 potentially conditional on the approval of the fee bill. We discuss the connection between the fee bill and this pay increase in the box below.

Pension Contributions Expected to Grow. CalPERS administers pension benefits for state employees and employees of local governments that contract with the pension system. The State Bar pension benefit is separate from that provided to state employees—the State Bar contracts with CalPERS to administer pension benefits similar to how many local governments contract with CalPERS. The State Bar’s contribution rates to CalPERS to fund employee pension benefits are expected to nearly double between 2017‑18 and 2024‑25 from 12.3 percent of payroll to 21.6 percent of payroll. Employer contributions to CalPERS are based on a variety of actuarial assumptions. Similar to the projected increases in the state’s pension contributions for its employees, the projected increases in the State Bar’s contributions to CalPERS primarily are due to the amortization of unfunded liabilities resulting from CalPERS adopting new actuarial assumptions.

State Bar Began Contracting With CalPERS for Health Benefits in 2018 . . . Prior to 2018, the State Bar used a broker to contract directly with health care providers to provide health insurance to State Bar employees. In 2017, the board relied on an actuarial analysis to determine that the State Bar could reduce costs by contracting with CalPERS to administer the health plans available to its employees. At the time, the State Bar estimated that contracting with CalPERS for health benefit administration could save it $1 million per year in lower health premiums. Although the decision to contract with CalPERS likely reduced State Bar costs, health care will continue to be a cost pressure as health premiums nationally have increased at a pace faster than inflation for the past couple of decades. Similarly, CalPERS health premiums grow each year. Over the past decade, CalPERS health premiums paid by the state have increased on average 5 percent each year (ranging from between 2 percent and 10 percent in any year).

. . . Which Required State Bar to Provide Retiree Health Benefits to Rank‑and‑File Employees. Under state law—the Public Employees’ Medical and Hospital Care Act (PEMHCA)—entities that contract with CalPERS to administer health benefits must provide at least a minimum level of retiree health benefits to all employees who retire with at least five years of service. This minimum benefit level is referred to as the “PEMHCA minimum” and was $133 per month in 2018 (the PEHMCA minimum increases each year). Before 2018, the State Bar provided retiree health benefits to executive staff only and provided no benefit to rank‑and‑file employees. (Executive employees account for roughly 10 percent of State Bar employees.) According to board meetings materials, the issue of providing retiree health benefits to rank‑and‑file employees has been a matter of discussion at the collective bargaining table on occasion for the past two decades. The 2017 actuarial analysis discussed above also determined that the State Bar could significantly reduce its annual premium costs by contracting with CalPERS to administer health benefits even though contracting with CalPERS would require the State Bar to provide its rank‑and‑file employees a new retiree health benefit.

Current State Bar Retiree Health Benefit Design. Under the current retiree health benefit design, the State Bar pays (1) the PEMHCA minimum for retired rank‑and‑file employees, retired executive employees who worked fewer than 15 years, and surviving spouses of retired employees and (2) 80 percent of premiums paid for retired executive employees who worked at least 15 years of service with the State Bar. For comparison, the retiree health benefit structure for new state employees provides them 40 percent of an average premium cost if they retire with 15 years of service and 80 percent of an average premium cost if they retire with 25 years of service. The state continues providing this level of benefit to surviving spouses.

Using 2018 CalPERS Bay Area single‑party coverage, Figure 9 compares the cost of the retiree health benefit received by a retiree with 15 years of service as an executive at the State Bar, a rank‑and‑file employee at the State Bar, and as an employee of the state. As the figure shows, the benefit currently provided to new executive employees who retire with 15 years of service is much higher than the benefit provided to an equivalent state employee—potentially more than three times as generous, depending on the health plan a retiree chooses.

Figure 9

Retired Executive State Bar Employees Receive Generous Health Benefits

|

Type of Employee Individual Retires as After 15 Years of Service (Assuming 2018 Hire) |

Monthly Employer Contribution Towards Single‑Party CalPERS Health Premiuma |

|

Executive Employee at the State Bar |

$570 ‑ $1000 |

|

Employee of the State of California |

About $290 |

|

Non‑Executive Employee at the State Bar |

$133 |

|

aUses 2018 CalPERS premiums for illustration. |

|

State Bar Plans to Enhance New Retiree Health Benefit for Rank‑and‑File Employees . . . The State Bar—both in conversations with us and in board meeting materials—indicates that it has a long‑term goal of providing rank‑and‑file employees the same benefit it currently provides executive employees. Specifically, the State Bar would pay 80 percent of health premiums paid for a retired employee with at least 15 years of service and his or her spouse for the retiree’s lifetime and the PEHMCA minimum for retired employees with fewer than 15 years of service and surviving spouses.

. . . Which Would Significantly Increase Costs. The 2017 actuarial analysis indicated that providing rank‑and‑file employees the same level of retiree health benefit as executive employees would be much more expensive than providing rank‑and‑file employees the PEHMCA minimum. Specifically, the analysis estimated that providing the PEHMCA minimum to rank‑and file employees would have an annual required contribution cost of $838,000, whereas providing retired rank‑and‑file employees the same benefit as retired executive employees would have an annual required contribution cost of $4.5 million—more than five times the annual cost of the current policy. Based on the 2017 actuarial analysis, the State Bar determined that it could not extend the more generous retiree health benefits to rank‑and‑file employees without a fee increase.

Non‑Personnel Expenditures

State Bar Projects Non‑Personnel Costs to be Fastest Growing Portion of Budget . . . The State Bar projects the 16 percent of the budget that is not related to employee compensation will grow faster than employee compensation costs. Specifically, as shown in Figure 10, whereas the State Bar projects personnel costs will grow by 40 percent over the five year period—from $73 million in 2019 to $103 million in 2024—it projects that non‑personnel costs will more than double from $14 million in 2019 to $31 million in 2024. The non‑personnel portion of the budget includes routine costs such as general operations costs (for example, postage, utilities, or travel) that any state department pays. Because the State Bar owns the two buildings it occupies, this portion of the budget also includes day‑to‑day operational costs associated with maintaining a building (for example, building security, insurance, and repairs). It also includes a number of large one‑time or less regular cyclical expenditures (for example, 2024 costs to repair the façade of the San Francisco building) and IT project‑related costs.

. . . Largely Due to Decisions to Defer Costs in the Past . . . The State Bar has chosen to defer maintenance costs in the past. Across the six years between 2019 and 2024, the State Bar projects that it will spend nearly $30 million on capital improvements to the buildings it owns. Not accounting for inflationary cost increases, these projects include $12.5 million for façade work in 2024; $2.9 million for maintenance to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems; $2.5 million related to work on elevators; and $1.2 million to address fire and life safety. The State Bar indicates that all of these projects were deferred in the past.

. . . And to Take on New Projects in the Future. The increased costs in non‑employee compensation costs also are due to the State Bar’s decision to take on new projects. For example, between 2019 and 2024, the State Bar expects to spend $16.7 million on IT projects. The State Bar also plans to replace IT hardware more frequently than it has in the past. For example, while the last time the State Bar replaced its desktops agencywide was in 2013, the State Bar plans to replace (or “refresh”) its desktops every three to five years going forward.

State Bar Request for Fee Increase

Proposed Ongoing Fee Increase. The State Bar seeks to cover $19.8 million in increased ongoing costs by proposing a $100 ongoing mandatory increase to the renewal fee for its active State Bar members beginning January 1, 2020. (The proposed fee increase for inactive members would be $28.) As shown in Figure 11, this fee increase includes: (1) $30 to address an operating deficit in which estimated expenditures exceed estimated revenues, (2) $30 to support the extension of retiree health benefits currently available only to executive employees to all State Bar employees and a salary increase (discussed in the nearby box) for represented employees, and (3) $40 to support the hiring of 58 additional staff for OCTC to improve disciplinary case processing times. The State Bar also requests the authority to adjust the entire renewal fee and the existing $25 disciplinary fee annually to account for inflation.

Figure 11

Summary of State Bar Request for a Fee Increase

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

Ongoing Fee Increase |

||

|

Operating Deficit |

$5.8 |

$30 |

|

Employee Compensation Costs |

||

|

Extending retiree health benefits |

3.2 |

17 |

|

Salary increase for represented employees |

2.7 |

13 |

|

Subtotals |

($5.9) |

($30) |

|

Additional Disciplinary Staff |

$8.0 |

$40 |

|

Totals |

$19.8 |

$100 |

|

One‑Time Assessmenta |

||

|

Building Improvements |

||

|

Building facade repair |

$14.5 |

$71 |

|

HVAC |

3.0 |

15 |

|

Fire and life safety projects |

1.3 |

6 |

|

Elevators, generators, and energy management |

4.3 |

21 |

|

Structural and other infrastructure projects |

2.6 |

13 |

|

Data center HVAC and electrical |

1.6 |

8 |

|

Subtotals |

($27.4) |

($134) |

|

Technology Projects |

||

|

New systems and one‑time projects |

$8.7 |

$43 |

|

Hardware upgrades and refresh |

7.3 |

36 |

|

Routine special projects |

0.6 |

3 |

|

Subtotals |

($16.7) |

($82) |

|

Maintaining a 17 Percent Budgetary Reserve |

$6.9 |

$34 |

|

Totals |

$50.9 |

$250 |

|

aExcludes request for $80 assessment for the Client Security Fund as it is outside the scope of this analysis. HVAC = heating, ventilation, and air conditioning. |

||

Labor Agreements Seem to Set Expectations That Employees Support Total Fee Increases

The labor agreements with the two State Bar bargaining units provide employees pay increases in 2020. In the same sections of the labor agreements that provide employees the 2020 pay increase, the agreements specify that “the union and the State Bar commit to working in good faith and to the extent reasonably possible to achieve in the bill authorizing the State Bar’s 2020 licensing fees, an increase in the individual licensing fees assessed on California attorneys that is both meaningful and sustainable and that ensures that the State Bar will be able to carry out its public protection mission and appropriately invest in its workforce.” The inclusion of this language suggests that the State Bar expects the bargaining units to support the State Bar’s efforts to achieve the total requested fee increase. That being said, the language does not appear to make the 2020 pay increase contingent on a 2020 fee increase approved by the Legislature.

Proposed One‑Time Fee Increase. The State Bar seeks to cover $50.9 million in additional one‑time costs by proposing a one‑time $250 assessment for its active members. (The proposed one‑time fee increase for inactive members would be $70.) While this would be a one‑time assessment in 2020, it would cover five years of projected costs. As shown in Figure 11, this fee increase includes: (1) $134 to support building improvement costs for five years, (2) $82 to support technology project costs for five years, and (3) $34 to restore the State Bar’s budget reserve level back to 17 percent.

Assessment of State Bar Budgeting Process

Current Process Generally Limits Legislative Oversight. Most of the state’s licensing and regulatory departments undergo regular review through the policy process as well as the budget process. This allows the policy committees with expertise in the licensed profession as well as the budget committees with expertise in fiscal oversight to comprehensively assess these state departments. While the State Bar must go through the policy process to receive legislative approval for its annual fee bill, it is not required to go through the budget process. This generally limits legislative oversight as the State Bar has significant flexibility in its budgeting practices—for example, operating on a calendar year basis rather than a fiscal year basis and making budgetary decisions with little legislative input. The State Bar also is not required to provide the same level of budgetary documentation or justification required by other departments seeking changes to their budgets. Furthermore, unlike most other state departments, the State Bar is not required to seek legislative approval for any changes in the total number of employees and/or their position classifications. This can make it more difficult to evaluate any proposed revenue or expenditure changes and ensure that funding is used consistent with legislative priorities and expectations.

Legislature Not Directly Involved in Major Policy Decisions With Cost Implications. In the past, the State Bar has made large policy decisions with cost implications—for example, purchasing the Los Angeles building or approving major IT systems—without consulting the Legislature. State Bar policies that are established at the bargaining table can have long‑term cost implications and can be agreed to before the Legislature has authorized a fee increase. This has the potential of putting the Legislature in a difficult situation if the State Bar cannot afford service contracts or collective bargaining agreement provisions without a fee increase.

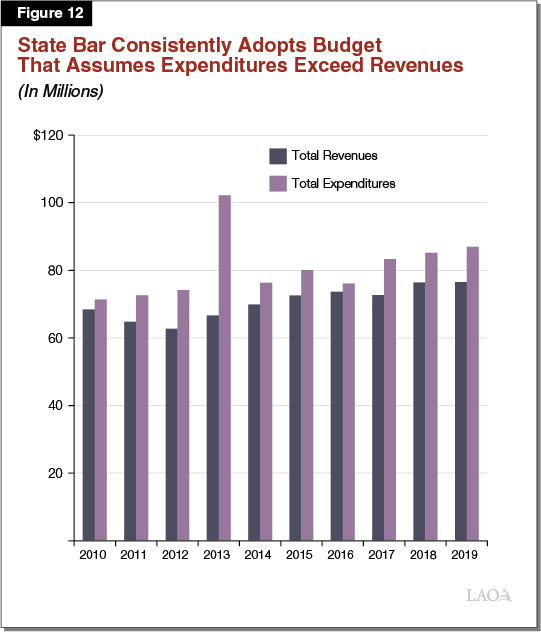

State Bar Consistently Approves Budgets With General Fund Expenditures Exceeding Revenues. A budget is a planning document used to determine and express an organization’s priorities and to ensure that the organization has sufficient resources on hand to realize those priorities. Figure 12 shows that the board consistently approves budgets that assume expenditures will exceed revenues. Actual costs end up being lower than the budgeted amounts—resulting in the operational surpluses discussed earlier—through a combination of lower‑than‑assumed costs resulting from (1) vacant positions and (2) operational decisions to defer priorities (like routine maintenance or technology replacement) that might have been approved in the budget. By consistently assuming that its priorities will cost more than the resources it has on hand, the State Bar’s budget has not been an effective planning tool. Moreover, the State Bar’s operational decisions to delay some costs could increase its costs in the long term. For example, deferring routine maintenance could result in higher one‑time costs in the future, like replacing a system sooner than otherwise would be needed.

Assessment of Request for Fee Increase

Proposed Ongoing Fee Increase

Increase to Address Structural Deficit

There Likely Is a Structural Deficit Beginning in 2018. As discussed above, the board has approved budgets in the past that assume the State Bar will end a fiscal year with a deficit. In most of the past years, the forecasted operational deficit has been avoided though some combination of lower‑than‑assumed costs and higher‑than‑assumed revenues. At first glance, the fact that past State Bar budgets have assumed deficits that never occurred weakens the State Bar’s argument for an increased fee to pay for a projected deficit. That being said, the State Bar estimates that its actual expenditures exceeded revenues in 2018 by $5.3 million. With rising salaries and pension costs expected to occur under current policy, we believe that the deficit experienced in 2018 may be structural in nature. Accordingly, an increase to the ongoing fee for the purpose of addressing a structural deficit seems reasonable.

Increase to Address Employee Compensation

Salary Increase Seems Reasonable. The 3 percent salary increases provided by the current labor agreements seems reasonable. It is comparable to the level of pay increases received by similar state employees.

Enhancing Retiree Health Benefits Out of Step With Other Public Employers. Most governments in California—including the state—are seeking to reduce unfunded liabilities associated with retiree health benefits through some combination of (1) reducing the benefits earned by future employees or (2) increasing the amount of money set aside to prefund the benefit. Most governmental employers historically did not prefund the benefit and have very few assets on hand to pay for the benefit. This has created a problem in recent years as (1) reporting requirements now require governments to report their retiree health liabilities in their annual financial statements and (2) retiree health costs have grown substantially as the Baby Boom Generation retires and health premiums continue to rise faster than inflation.

The State Bar is in a relatively unique situation where—under the current benefit design where executive employees receive a more generous benefit and rank‑and‑file employees receive the PEHMCA minimum—it has more assets on hand than the liability created by the benefit. This means that the State Bar currently has no unfunded liability associated with its retiree health benefits. According to the most recent actuarial valuation—as of January 1, 2018—the State Bar has $25.4 million in assets for a liability of $17.4 million. If the State Bar were to extend to all employees the retiree health benefit currently only earned by executive staff, actuaries estimate that the liability would immediately grow to $38.5 million—resulting in a $13.1 million unfunded liability. Being only 66 percent funded, the State Bar’s actuarially determined contribution (the amount it needs to contribute each year to fully prefund the benefit) would increase from $0 to more than $3 million (based on the June 30, 2018 actuarial valuation).

The State Bar has expressed a long‑term goal of equalizing retiree health benefits for executive and non‑executive retirees. The State Bar indicated that it did not consider establishing a lower retiree health benefit for all employees that allowed the agency to not take on the burden of an unfunded liability. For example, if future executives received the PEHMCA minimum similar to current rank‑and‑file employees, the State Bar’s retiree health benefit would be more than 100 percent funded and no additional contributions (or an associated fee increase) would be needed in the near term.

Increase for Additional Disciplinary Staff

Request May Be Premature Given Recently Implemented Changes. The State Bar recently implemented various changes to improve its case processing times, including a new OCTC team structure, a new case prioritization methodology, and a new case management system. Given that these changes have just been adopted, the full effect of these changes likely have yet to be realized. For example, new processes or systems typically require time to adapt before they are operating at their full potential. Consequently, whether these changes will actually improve case processing times and the extent to which they do so is unclear. For example, the State Bar’s 2018 Annual Discipline Report suggests that these changes could have a positive impact as the total number of backlog cases declined slightly. As such, the request for additional staffing resources may be premature.

Workload Study May Not Accurately Identify Staffing Need. The State Bar’s workload study may not accurately identify staffing needs; consequently, the fee request to support 58 additional staff may not be justified. We believe there are two issues with the workload study. First, the State Bar’s methodology consists of case weights that capture the average amount of time it takes for OCTC to process a case with existing staffing levels. The case weights currently do not reflect the amount of time that would be needed to process cases within the 180 day time frame. Because of this, the case weights cannot be used to calculate the total number of staff needed to process all cases within the 180 day time frame. If used correctly, similar to the judicial branch’s use of case weights, the difference between the calculated and existing staffing levels would reflect the number of additional staff needed. Instead, the State Bar calculates its OCTC staffing need based on a relationship it identified in historical data. It is not clear if this correlation accurately predicts the effect additional staff would have on case disposition time.

Second, different case weights may be needed for different complaint types or priority categories to the extent they require different levels or combinations of disciplinary tasks. Rather than just using one set of case weights for all case types as the State Bar currently does, differentiating between the processes for specific complaint types or priority cases can help more accurately identify workload need. For example, under the new case prioritization methodology, State Bar Priority Two cases should take less time on average to process than other cases because certain disciplinary tasks are excluded. This approach would be similar to the judicial branch’s methodology that uses different case weights for its case types—such as felony cases and traffic misdemeanors.

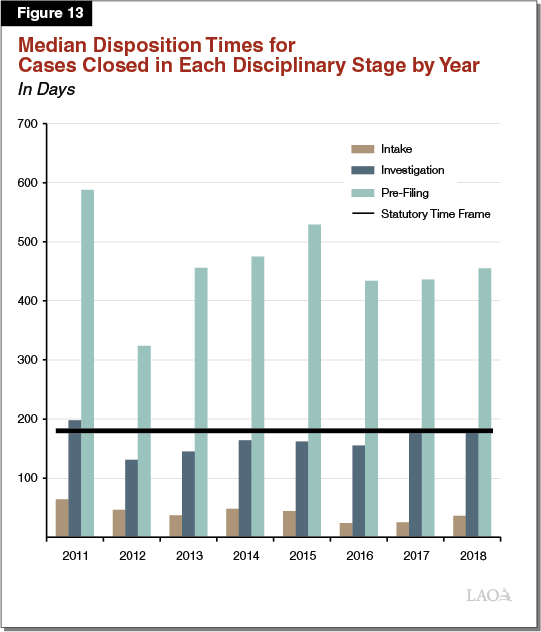

A Different Statutory Time Frame Could Require Fewer Staff. The State Bar’s workload study was premised on meeting the 180‑day statutory time frame for completing the first three stages of the disciplinary process. As shown in Figure 13, the median disposition times for cases closed in either the Intake Stage (36 days in 2018) or the Investigation Stage (177 days in 2018) fall under this statutory time frame. However, the median disposition time for cases closed in the Pre‑Filing Stage (455 days in 2018) has regularly exceeded this time frame for years. As such, the existing statutory time frame does not appear to provide a meaningful measure for processing cases. Consequently, alternative statutory time frames—like ones based on either the specific stage in which cases are closed, the severity of complaints, or specific complaint types—could provide more meaningful metrics measuring State Bar activities while also potentially requiring fewer additional staff.

Fee Increase for Additional Disciplinary Staff Likely Premature. Overall, the fee increase request for additional disciplinary staff likely is premature. Not only does the State Bar need more time to see the effects of recent changes, but also the methodology for determining the number of additional staff needed needs revision. Moreover, should the Legislature wish to change the statutory time frame, the staffing requirements to meet those changes would be different than currently estimated.

Request for Annual Inflationary Adjustment

Lacks Justification. We find that the request for an annual inflationary adjustment for the renewal and disciplinary fee lacks justification. Many other licensing bodies must periodically request adjustments for increases in general costs of doing business. There does not appear to be any obstacle that prevents the State Bar from seeking a fee increase and demonstrating to the Legislature why it is needed. Additionally, the Legislature enacted state law in 2009 that prohibits automatic increases—except as provided in the budget act and implementing statutes—from being provided to the University of California, the California State University, the state courts, or to state agency operations. This includes annual price increases to state departments and agencies. The State Bar has not provided sufficient justification for why it should be treated differently from a number of other state departments and agencies, including the state trial courts.

Request Could Limit Legislative Oversight. We note that this request could severely limit legislative oversight over State Bar operations. To the extent that State Bar expenditures do not exceed the inflationary adjustment, the State Bar would have significant flexibility in the use of any excess funding. This could result in the commitment of funds to projects or activities that are not aligned with legislative priorities, not sufficiently justified, or could have significant out‑year costs. To the extent that the State Bar seeks fee increases intermittently, it could be difficult for the Legislature to evaluate the request and undo commitments that may have been made that do not conform to legislative priorities or expectations.

Proposed One‑Time Fee Increase

Lack of Justification for Five Years of Costs. We find that the request for a one‑time assessment to cover five years of costs lacks justification. First, this request would increase the total licensing fee for attorneys significantly. Moreover, this increase would be paid only by those who are currently members but would provide benefit to a much broader group of attorneys—like those becoming members after 2020. Second, the Legislature has chosen to require the State Bar to justify its budget and operations every year by requiring an annual fee bill. There is little justification for why an exception should be provided for these particular proposed activities. Third, a number of the projects—such as HVAC costs or technology projects—could have significant one‑time and ongoing costs. As we discuss later, the Legislature may want to impose greater oversight over these types of expenditures to ensure that the funds are used efficiently and that their use is consistent with legislative priorities and expectations.

Not Clear Why Certain Costs Are Considered One Time. Certain costs the State Bar hopes to fund using the proposed one‑time fee increase should be considered ongoing costs. For example, cyclical replacements of technological hardware (such as computers) should be scheduled fairly equally over multiple years to minimize the risk of universal equipment failure and reduce the amount of funding needed annually. Similarly, certain building improvements are ongoing and predictable obligations that should be planned for accordingly. As these costs are routine and ongoing, including them in a one‑time assessment may not be appropriate.

Alternative Fee Increase Options

In light of these concerns, we provide various alternative fee increase options for legislative consideration. The Legislature can select from these options to calculate the total ongoing and one‑time fee increase that best reflects legislative priorities. (Please see Appendix B for a summary of the recommendations made by the State Auditor.) We discuss these options in more detail below.

Options to Address Proposed Ongoing Fee Increase

Option to Address the Operating Deficit. The Legislature could authorize a $21 fee increase to address the operating deficit. This option is $9 less than the State Bar request because it excludes costs to scan old disciplinary files that currently are included in the State Bar’s budget. While this project would improve the efficiency of the State Bar’s new case management system and reduce State Bar storage costs for storing attorney records, the project is generally one time in nature and should not be considered an ongoing cost. Additionally, rather than scanning all files, we believe selectively scanning old documents or files—such as scanning old files related to an attorney for which a new complaint is received—would be more efficient.

Options to Address Employee Compensation Costs. We generally have no concerns with the State Bar’s request for a $13 fee increase to provide salary increases to State Bar represented employees as it is generally comparable to the increases received by similar state employees. However, as discussed above, the State Bar seeks to provide more generous retiree health benefits to its employees than the state provides to its employees. Specifically, state employees must work 25 years to receive roughly the same benefit that State Bar executive employees receive with 15 years of service. As shown in Figure 14, the Legislature could consider authorizing a lower fee increase than requested by the State Bar—for example, providing a benefit that is comparable to that earned by state employees. The specific fee level would depend on the structure of the lower benefit and the amount of money that actuaries determine would be necessary to ensure the benefit is fully funded.

Figure 14

Alternative Options for Employee Compensation Costs

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

Salary increase for represented employees as requested by the State Bar |

$2.7 |

$13 |

|

Providing retiree health benefits similar to other state and local departmentsa |

Less than $3.2 |

Less than $17 |

|

aState benefit based on vesting schedule whereby employees must work 15 years with the state to receive one‑half of the retiree health benefits and 25 years to receive the full benefit. The amount needed and corresponding fee increase should be determined by an actuary. |

||

Options to Address Request for Additional Disciplinary Staff. As discussed above, we question whether the request for additional resources is premature given the recent implementation of various disciplinary system changes as well as whether the State Bar’s new workload methodology accurately identifies workload need. The Legislature could consider fee options to provide some additional resources that could help address the backlog of disciplinary cases or to help improve processing times. This would then allow the State Bar to measure the actual effect of these additional positions as well as to allow the recent disciplinary system initiatives to take full effect. This data also could be used to refine the State Bar’s workload study methodology and could help the Legislature determine the appropriate level of resources needed to meet legislative expectations. Specifically, as shown in Figure 15, the Legislature could consider authorizing an $11 fee increase to provide one additional enforcement team consisting of 16 attorneys, investigators, and other associated staff or a $4 fee increase to provide two sets of attorneys, investigators, and associated administrative staff.

Figure 15

Alternative Options for Additional Disciplinary Staff Request

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

One additional enforcement team (16 positions) |

$2.1 |

$11 |

|

Two sets of attorney‑investigator pairs (6 positions) |

0.8 |

4 |

|

Monitoring impact of recently enacted disciplinary system changes |

— |

— |

|

Adjusting time frames |

— |

— |

The Legislature also could consider providing no fee increase at this time. Instead, the Legislature could direct the State Bar to monitor the impact of the recently enacted changes to the disciplinary system and refine its workload study methodology. As noted previously, the State Bar regularly exceeded its statutory time frames in prior years. The Legislature could consider whether the 180 day statutory time frame is appropriate. For example, some other state licensing entities have a 270 day target time frame from receiving a complaint through completing investigations for cases not transmitted to the Attorney General for formal disciplinary proceedings. To the extent the Legislature decides to change these time frames, fewer positions (if any) may be needed. (For context, Appendix C provides a comparison of the State Bar’s disciplinary process with those of a handful of other state licensing departments.)

Options for Annualizing Certain One‑Time Costs. The Legislature could consider whether certain State Bar costs should be annualized (or distributed evenly over a certain number of years) and considered as part of the ongoing fee rather than as part of a one‑time special assessment. As shown in Figure 16, the Legislature could consider authorizing a $7 fee increase to account for routine ongoing IT costs (such as regularly replacing computer equipment on a five‑year cycle). Additionally, the Legislature could consider whether to authorize fee increases to annualize building improvement costs. Annualizing over five years could result in a fee increase of $27 for all requested projects or $9 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor. Annualizing over ten years could decrease this fee increase to $13 for all requested projects or $4 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor.

Figure 16

Alternative Options for Annualizing Certain One‑Time Costs

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

Routine or cyclical ongoing technology costs (State Auditor recommended projects)a |

$1.37 |

$7 |

|

Five‑year annualized building improvement costs (all requested projects) |

5.47 |

27 |

|

Five‑year annualized building improvement costs (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

1.83 |

9 |

|

Ten‑year annualized building improvement costs (all requested projects) |

2.74 |

13 |

|

Ten‑year annualized building improvement costs (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

0.92 |

4 |

|

aFor information technology equipment, we assume a five‑year replacement cycle. |

||

Options to Address Proposed One‑Time Fee Increase

Options to Address Building Improvements. One approach is for the Legislature to authorize a one‑time fee to cover the portion of project costs the State Bar would like to incur specifically in 2020. As shown in Figure 17, this could mean a one‑time fee of $39 for all projects proposed by the State Bar or $27 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor. An alternative approach is for the Legislature to require the State Bar to distribute all project costs equitably over a certain period of time. Assuming total building improvement costs are annualized over five years, the Legislature could consider authorizing a fee of $27 for all projects proposed by the State Bar or $9 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor for five years.

Figure 17

Alternative Options for One‑Time Building Improvement Costs

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

2020 costs (all projects) |

$8.0 |

$39 |

|

2020 costs (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

5.6 |

27 |

|

2020 costs assuming five‑year annualization (all projects) |

5.5 |

27 |

|

2020 costs assuming five‑year annualization (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

1.8 |

9 |

Options to Address Technology Projects. Similar to our approach for building improvement costs, our options here provide the State Bar with only 2020 costs for those projects we see as truly one time in nature. As shown in Figure 18, the Legislature could consider authorizing a one‑time fee of $7 for all projects or $4 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor to cover the portion of project costs the State Bar would like to incur specifically in 2020. Alternatively, assuming total new system or one‑time project costs are annualized over five years, the Legislature could consider authorizing a fee of $9 for all projects or $5 for only those projects recommended by the State Auditor for five years. Additionally, to the extent that the Legislature is interested in the State Bar’s proposed project to scan old disciplinary files, the Legislature could authorize a $46 fee to cover the full costs associated with this project or a $9 fee to cover the 2020 costs associated with this project. This project likely will be limited term in nature, so a one‑time assessment could be appropriate.

Figure 18

Alternative Options for One‑Time Information Technology Costs

|

Purpose |

Total Amount Needed (In Millions) |

Fee Increase for Active Members |

|

2020 costs for new systems or one‑time projects (all projects) |

$1.4 |

$7 |

|

2020 costs for new systems or one‑time projects (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

0.7 |

4 |

|

2020 costs assuming five‑year annualization for new systems or one‑time projects (all projects) |

1.7 |

9 |

|

2020 costs assuming five‑year annualization for new systems or one‑time projects (State Auditor recommended projects only) |

1.0 |

5 |

|

Full cost for scanning old disciplinary files (five years) |

9.4 |

46 |

|

2020 cost for scanning old disciplinary files |

1.9 |

9 |

Options to Restore the Budget Reserve to 17 Percent. The Legislature could determine what level of resources to provide in 2020 based on the total fee level it is comfortable providing. The Legislature could provide $3 as recommended by the State Auditor to provide the equivalent of a 1 percent increase in order to slowly rebuild the State Bar’s budget reserve level over time. Alternatively, the Legislature could provide more or less depending on how quickly it would like to rebuild the reserve.

Summary of Alternative Fee Options

The Legislature can select from the various provided options, or others (such as those offered by the State Auditor), to calculate the total ongoing and one‑time assessment it would like to authorize. Figure 19 provides three examples of how the assessments could differ based on choices made by the Legislature. The “low” example demonstrates a “bare‑bones” assessment to cover the most immediate and necessary costs—such as addressing the ongoing deficit, providing a salary increase for represented employees, and providing some funding for IT or building improvement costs. The “medium” example demonstrates an assessment that provides some additional resources, such as support for additional disciplinary system employees. Finally, the “high” example demonstrates an assessment that provides some level of resources across every area identified by the State Bar.

Figure 19

Examples of Range of Fee Alternatives Available

|

Assessment |

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

Ongoing Assessment |

|||

|

Addressing the ongoing deficit |

$21 |

$21 |

$21 |

|

Salary increase for represented employees |

13 |

13 |

13 |

|

Expanding retiree benefits |

— |

— |

17 |

|

Additional disciplinary system employees |

— |

4 |

11 |

|

Routine or cyclical information technology (IT) costs |

— |

7 |

7 |

|

Totals |

$34 |

$45 |

$69 |

|

One‑Time Assessment |

|||

|

Building improvement costs |

$9 |

$27 |

$39 |

|

New system, nonroutine, and noncyclical IT costs |

4 |

7 |

9 |

|

Scanning old disciplinary files |

— |

9 |

9 |

|

Restoring a 17 percent budget reserve |

— |

3 |

6 |

|

Totals |

$13 |

$46 |

$63 |

Other Issue for Legislative Consideration

Consider Appropriate Level of Legislative Oversight

Regardless of how much funding is ultimately approved, our review of the State Bar indicates that increased legislative oversight could be beneficial to ensure that fee revenues are assessed appropriately to support expenditures that are consistent with legislative expectations and priorities. Increased oversight also would help ensure that funds are used in an accountable and transparent manner. Such oversight can occur in various ways—such as including the State Bar in the annual budgeting process, revising the fee structure, requiring legislative approval for proposed expenditures with significant one‑time or ongoing fiscal impacts, providing employee compensation guidelines, and requiring reporting on various performance or outcome measures. We discuss each of these options in more detail below.

Consider Including State Bar in Annual State Budget Process. The Legislature could consider including the State Bar as part of the annual state budget process. This would require the State Bar to shift its budgeting and financial processes from a calendar year basis to the state fiscal year basis. The Legislature’s Judiciary Committees would retain policy oversight over the State Bar, similar to how the Legislature’s Business and Professions Committees retain jurisdiction over certain other state licensing departments. At the same time, State Bar budget oversight would be conducted by the Legislature’s budget committees. Taking this action could increase legislative oversight by leveraging the expertise of the budgetary committees to evaluate State Bar funding requests in a manner similar to other state departments. Additionally, requiring the State Bar to submit budgetary information in a manner similar to other state departments would enable easier comparison to ensure standardized or similar treatment across the various departments responsible for licensing professions.

Consider Appropriate Fee Structure. The Legislature could consider whether the existing fee structure ensures that funding is used in a particular manner. For example, the Legislature could consider whether to approve separate fees for various specific operational purposes (such as a fee to support the disciplinary system or a fee to support IT costs) in order to ensure the State Bar uses funding for specific legislatively desired purposes.

Consider Requiring Legislative Approval for Certain Proposed Expenditures. The Legislature could consider requiring additional oversight in certain situations, such as requiring the State Bar to seek legislative approval before beginning projects that cost above a certain threshold or implementing major policy changes with budgetary implications. This could help ensure that proposed projects are thoroughly evaluated before committing the state to future cost pressures and that funding is used consistently with legislative expectations.

Consider Employee Compensation Guidelines. Although the Legislature plays no role in the collective bargaining process at the State Bar, the Legislature could incorporate guidelines for the State Bar to follow as a condition of the fee established in a fee bill or—if the State Bar were incorporated into the state budget—as provisional language in the budget act. For example, the Legislature could specify that no more than a certain amount of the fee could be used to pay for retiree health benefits.

Consider Performance and Outcome Measures for Any New Resources Provided. The Legislature currently receives reports on certain State Bar activities. For example, the State Bar is required to provide an annual discipline report that provides key outcome measures for disciplinary workload. The Legislature could consider modifying these established requirements as well as implementing new outcome and performance measures that reflect the Legislature’s intended expectations for any funding provided. This will help the Legislature monitor how the funding is used and any effect the new funding has upon State Bar operations (such as the effect any new OCTC positions has upon disciplinary disposition times). This would also help the Legislature evaluate whether legislative expectations were actually met, determine whether future policy changes are needed, and make decisions on appropriate funding and service levels in the future.

Conclusion

We reviewed the State Bar’s operations and its use of the General Fund portion of the annual fee charged to attorneys. Through this review, we found elements of the State Bar’s proposed one‑time and ongoing increases to this fee to be reasonable while others to be premature, unjustified, or otherwise problematic. In this report, we provide a menu of alternative fee increase options for legislative consideration. The Legislature can select from these options to calculate the total fee increase it believes best reflects its legislative priorities. In addition, we identified concerns with the State Bar’s overall budgeting process. To address these concerns, we provide options for legislative consideration that would enhance legislative oversight of the State Bar’s budget.

Appendix A— Examples of Base Licensing Fees for Active Members of Selected Professions

Appendix A, Figure 1

Examples of Base Licensing Fees for Active Members of Selected Professions

|

Profession |

Regulating Agency |

Annualized Base Feea |

|

Fiduciary |

Professional Fiduciaries Bureau |

$700 |

|

Doctor of Podiatric Medicine |

Board of Podiatric Medicine |

450 |

|

Naturopathic Doctor |

Naturopathic Medicine Committee |

400 |

|

Physician or Surgeon |

Medical Board of California |

392 |

|

Dentist |

Dental Board of California |

325 |

|

Attorney |

State Bar of California |

315 |

|

Contractor |

Contractors State License Board |

200 |

|

Clinical Counselor |

Board of Behavioral Services |

200 |

|

Psychologist |

California Board of Psychology |

200 |

|

Architect |

California Architects Board |

150 |

|

Certified Public Accountant |

California Board of Accountancy |

125 |

|

Real Estate Broker |

California Department of Real Estate |

75 |

|

Professional Engineer |

Board for Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors, and Geologists |

58 |

|

aBase fees for multiyear time periods annualized (or distributed equally across the covered time period) for comparison purposes. |

||

Appendix B— Summary of Major State Auditor Recommendations

As required by Chapter 659 of 2018 (AB 3249, Committee on Judiciary), the State Auditor released a report on April 30, 2019 evaluating the State Bar’s budget, its proposed 2020 fee increase, and other objectives. We provide a summary of the major State Auditor recommendations below.

Proposed 2020 Fee Increase

The State Bar proposed to increase the $383 mandatory active member fee by $100 on an ongoing basis and $330 on a one‑time basis in 2020—resulting in a total mandatory fee of $813 in 2020. In its evaluation, the State Auditor recommends a total mandatory active member fee of $525 based on various findings, which we discuss in more detail below.

Mandatory Ongoing Fee

The State Auditor recommends a mandatory ongoing fee of $444 from active members—$39 less than requested by the State Bar. This represents a $61 increase over the 2019 mandatory ongoing fee. We summarize the reasons for this difference below.

Licensing Fee ($29 Less Than State Bar Request). The State Auditor recommends increasing the $308 mandatory license fee for active members by only $71 (instead of the $100 fee increase requested by the State Bar), resulting in a total 2020 mandatory licensing fee of $379. The reduction in the fee is due to the State Auditor determining that the request for 58 additional disciplinary staff was premature and that only funding for 19 new hires be provided to staff one enforcement team. The State Auditor found that gradually increasing staff would allow the State Bar to quantify the effects of implementing its new process and of adding an enforcement team so that it can evaluate and justify any future needs for new staff and the associated fee increases.