LAO Contact

Update 11/8/19: Adjustments made to per-student education costs

November 6, 2019

Overview of Special Education in California

- Introduction

- Special Education Law

- Students With Disabilities

- Special Education Services

- Outcomes for Students With Disabilities

- Special Education Finance

- Oversight

- Dispute Resolution

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Report Provides Overview of Special Education Services for Students With Disabilities. Since the 1970s, federal law has required public elementary and secondary schools to provide special education services to students with disabilities. Parents or teachers typically are the first ones to identify if a student might benefit from special education services. In most cases, children are then referred to school district specialists, who evaluate whether the student has a disability that interferes with his or her ability to learn. If determined to have one or more such disabilities, the student receives an individualized education program (IEP) that sets forth the additional services the school will provide. The IEP is developed by a team consisting of each student’s parents, teachers, and district administrators. The IEP may include various types of special education services, such as specialized academic instruction, speech therapy, physical therapy, counseling, or behavioral intervention.

About One in Eight California Students Receives Special Education Services. In 2017‑18, 12.5 percent of California public school students received special education—an increase from 10.8 percent in the early 2000s. Compared to other California students, students with disabilities are disproportionately low income. They also are disproportionately African American, with African American students representing 6 percent of the overall student population but 9 percent of students with disabilities. The majority of students with disabilities have relatively mild conditions such as speech impairments and specific learning disorders (such as dyslexia). The number of students with relatively severe disabilities, however, has been increasing—doubling since 2000‑01. The most notable rise is in autism, which affected 1 in 600 students in 1997‑98 compared to 1 in 50 students in 2017‑18.

Majority of Students With Disabilities Served in Mainstream Classrooms. Federal law generally requires districts to serve students with disabilities in the least restrictive setting, and the majority of students with disabilities are taught alongside students without disabilities in mainstream classrooms. These students may receive special education services within the mainstream classrooms (for example, having an aide or interpreter) or in separate pull‑out sessions. About 20 percent of students with disabilities are taught primarily in special day classrooms alongside other students with disabilities. Typically, special day classes serve students with relatively severe disabilities and provide more opportunities for one‑on‑one attention or specialized instruction, such as instruction in sign language. Another 20 percent of students with disabilities split their time between mainstream and special day classrooms. About 3 percent of students with disabilities are educated in separate schools exclusively serving students with disabilities.

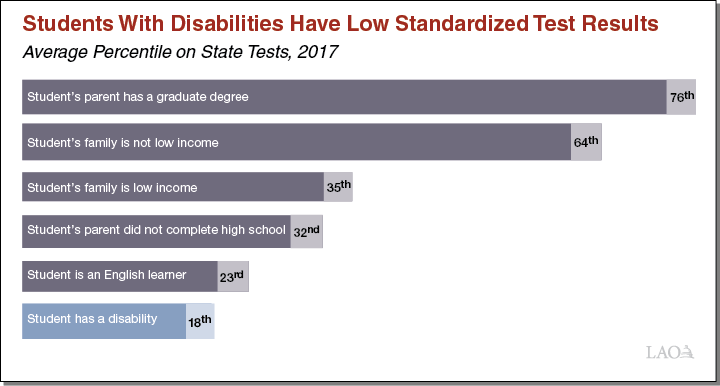

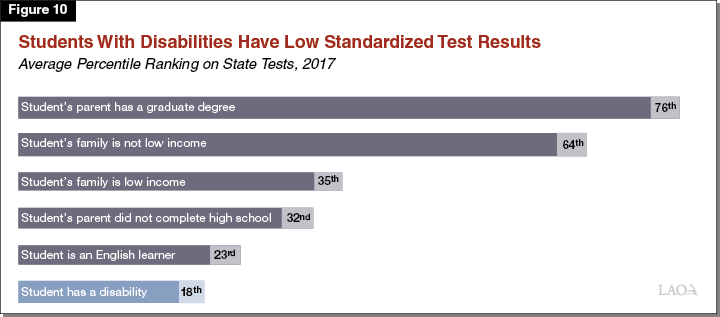

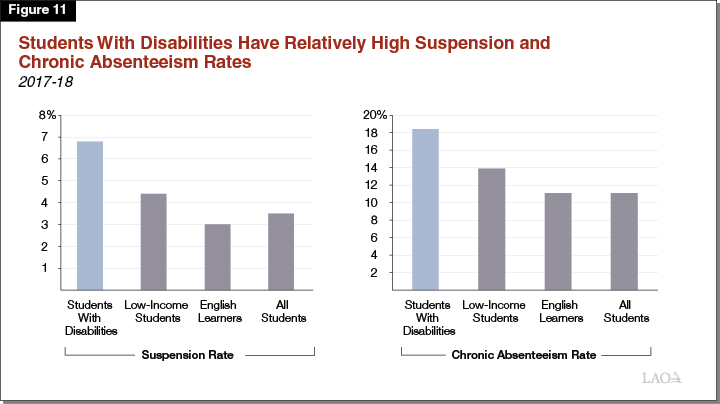

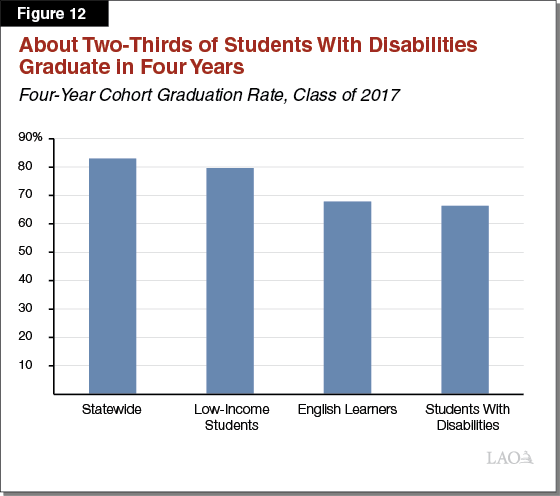

Students With Disabilities Have Lower Academic Outcomes Than Other Students. As the figure shows, students with disabilities’ average test score on state reading and math assessments was at the 18th percentile of all test takers in 2017‑18—notably below that of low‑income students and English learners. Students with disabilities also have a lower four‑year graduation rate than other student groups; a suspension rate that is almost double the statewide average; and a relatively high rate of chronic absenteeism, with almost one in five students with disabilities missing 10 percent or more of the school year.

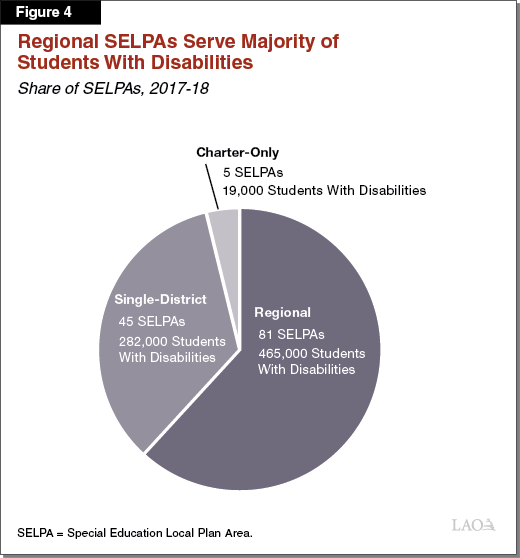

Special Education Funding and Services Typically Are Coordinated Regionally. The state requires school districts to form Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). Each SELPA is tasked with developing a plan for delivering special education services within that area. Small and mid‑sized districts form regional SELPAs to coordinate their special education services. Large districts may serve as their own SELPAs. Charter schools are allowed to join charter‑only SELPAs, which, unlike regional SELPAs, may accept members from any part of the state. As of 2017‑18, California has 132 SELPAs—consisting of 81 regional SELPAs, 45 single‑district SELPAs, 5 charter‑only SELPAs, and 1 unique SELPA serving students in Los Angeles County court schools.

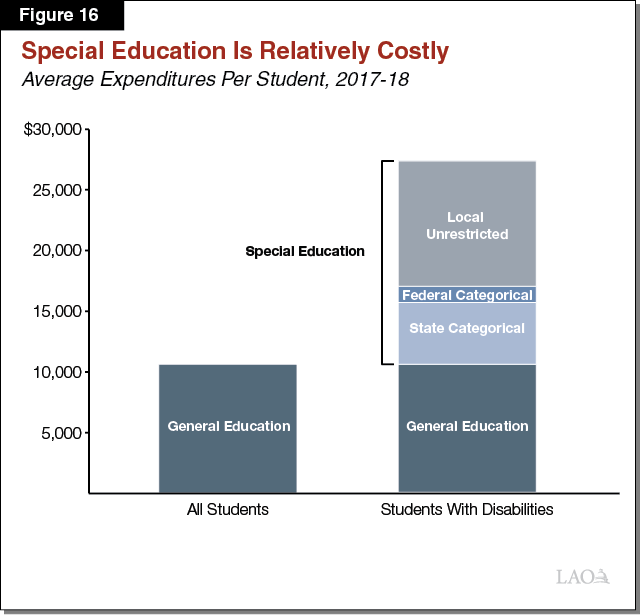

Excess Cost Associated With Special Education Is Supported by Three Fund Sources. The average annual cost of educating a student with disabilities ($26,000) is almost triple that of a student without disabilities ($9,000). The excess cost associated with providing special education services is supported by state categorical funding, federal categorical funding, and local unrestricted funding. With the exception of a few small categorical programs (such as funding for infant/toddler services and job placement and training for older students), most state and federal special education funding is provided to SELPAs rather than directly to school districts. The largest state categorical program is known as AB 602 after its authorizing legislation. AB 602 provides SELPAs funding based on their overall student attendance, regardless of how many students receive special education or what kinds of services those students receive. Typically, SELPAs reserve some funding for regionalized services and distribute the rest to member districts. School districts use local unrestricted funding (primarily from the Local Control Funding Formula) to support any costs not covered by state and federal categorical funding.

Special Education Costs Have Increased Notably in Recent Years. Between 2007‑08 and 2017‑18, inflation‑adjusted special education expenditures increased from $10.8 billion to $13 billion (28 percent). Both state and federal funding decreased in inflation‑adjusted terms over this period, primarily as a result of declining overall student attendance. Consequently, local unrestricted funding has been covering an increasing share of special education expenditures (49 percent in 2007‑08 compared to 61 percent in 2017‑18). We estimate that about one‑third of recent increases in special education expenditures are due to general increases in staff salaries and pension costs affecting most school districts. We estimate that the remaining two‑thirds of recent cost increases are due to a rise in an incidence of students with relatively severe disabilities (particularly autism), which require more expensive and intensive supports.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the share of students identified with disabilities affecting their education has increased notably. Over the same period, inflation‑adjusted per‑student special education expenditures also have increased notably. Today, nearly 800,000 students in California receive special education services at a statewide annual cost of $13 billion. Despite this spending, state accountability data show that school districts have poor outcomes for their students with disabilities. These trends have motivated many district‑ and state‑level groups to take a closer look at how California organizes, delivers, and funds special education. Recent legislation directed the Legislature and administration to work collaboratively over the coming months to consider changes in these areas, with the overarching intent to improve special education outcomes.

In this report, we aim to inform these fiscal and policy conversations by providing an overview of special education in California. We begin by describing major special education requirements, then present the latest data on students served, outcomes achieved, and dollars spent. We conclude by describing oversight activities and dispute resolution. Throughout the report, we refer to several of our other products that delve into greater detail on specific special education topics.

Special Education Law

In this section, we identify major federal and state requirements for serving students with disabilities.

Major Federal Requirements

Federal Courts Ruled Public Schools Must Educate All Students, Regardless of Disability. Prior to the 1970s, public schools did not serve some children with severe cognitive or physical disabilities. Even those schools serving children with severe disabilities sometimes offered only basic daycare services with little or no educational benefit. Starting in the early 1970s, federal courts declared all children have a right to public education regardless of disability.

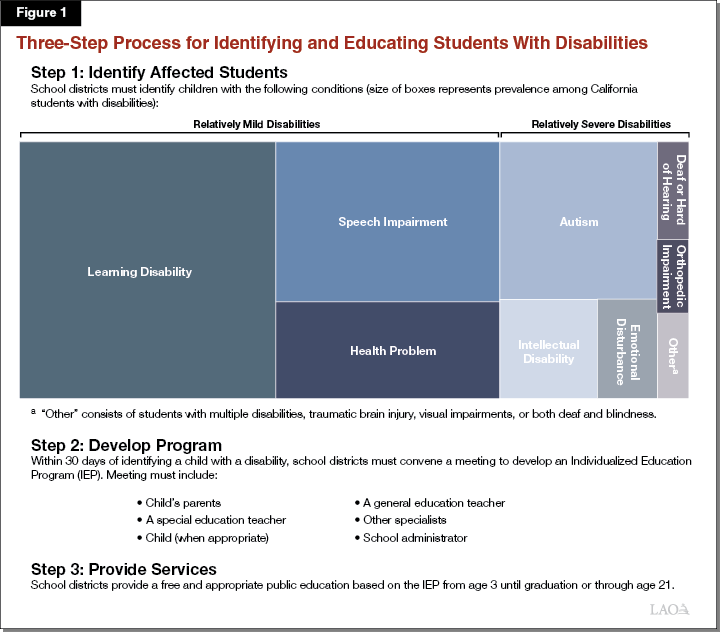

Federal Law Establishes Formal Special Education Process. Federal lawmakers responded to these court rulings by establishing a process for identifying and serving children with disabilities. Enacted in 1975, the federal law now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) set forth a three‑step process (Figure 1). IDEA authorizes federal funding to all states agreeing to implement this process. Currently, all states participate in IDEA. (For a brief overview of IDEA, see our video Overview of Special Education in California.)

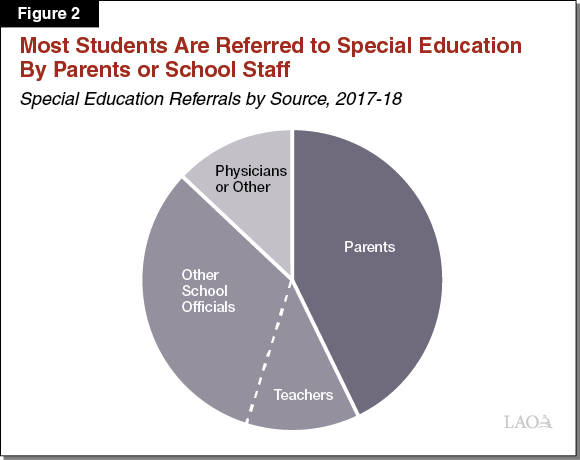

Districts Evaluate Whether Students Have Disabilities Requiring Special Education. Federal law charges school districts with making proactive efforts to identify all children with disabilities in their service areas (a responsibility commonly known as “child find”). In practice, many children are referred for special education by their parents, perhaps in response to districts’ public awareness campaigns. In most other cases, children are referred by teachers or other school officials (Figure 2). After a child is referred, specialists conduct a formal evaluation to determine whether (1) the child has a disability and (2) the disability interferes with the child’s ability to learn. Children that meet both of these requirements qualify for special education. In addition to special education services, federal law requires certain other services be provided to children with disabilities, as explained in the box below.

Other Federal Laws Affecting Students With Disabilities

School Districts Must Address Specific Student Health Needs. Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provides certain rights to students with any condition that affects one or more major life activities, including walking, seeing, breathing, and concentrating. Qualifying conditions range from disabilities that also qualify students for special education, such as autism, to conditions that do not typically qualify students for special education, such as diabetes or severe allergies. Students with qualifying conditions are entitled to an individualized “504 plan” that specifies how schools will accommodate their medical needs. For example, a 504 plan could explain how the school will administer prescribed insulin treatments to a student with diabetes throughout the school day.

Schools Must Ensure All Facilities and Events Are Accessible to Individuals With Disabilities. The federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 requires public spaces, including schools, to be accessible to individuals with disabilities. This act also requires schools to make all activities accessible to individuals with disabilities, for example, by providing ramps for wheelchair access or sign language interpreters upon request. Although many of these protections overlap with those provided by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), they apply in some situations where IDEA may not. For example, ADA requires access to after‑school events that may not be included in students’ individualized education programs.

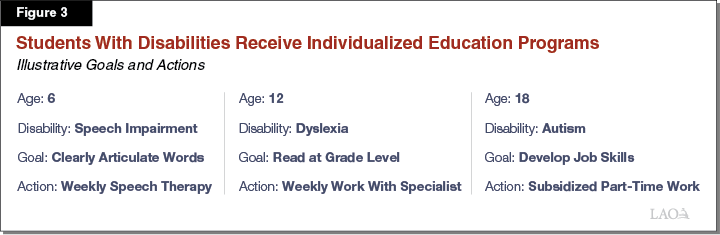

Students’ Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) Define Their Special Education Services. Once determined eligible for special education, students with disabilities receive IEPs specifying the support their school districts will provide. At least once per year, each student’s parents, teachers, and district administrators meet to develop his or her IEP, which includes specific goals and actions tailored to that student’s abilities and needs. Figure 3 provides some illustrative goals and actions that may be included in students’ IEPs.

Districts Must Serve Students With Disabilities in the Least Restrictive Environment. Federal law generally requires districts to serve students with disabilities in whichever educationally appropriate setting offers the most opportunity to interact with peers who do not have disabilities. For students with relatively mild disabilities, this typically means receiving instruction in mainstream classrooms. For students with relatively severe disabilities, this may mean receiving most of their instruction in special day classrooms (which exclusively serve students with disabilities) but participating in lunch or recess alongside students who do not have disabilities. As with all elements of a child’s IEP, the least restrictive environment must be determined collaboratively by each student’s parents, teachers, and district administrators.

School Districts Must Offer Special Education Services Even to Students Enrolled in Private Schools. About 7.5 percent of California’s school‑aged children (roughly 500,000 students) are enrolled in private schools. Federal law requires school districts to identify and offer special education to all qualified children residing in their service areas, regardless of whether these children attend public or private schools. Although school districts must offer special education to these children (for example, by offering to pay for instructional aides to work alongside them in their private school classes), their parents may choose to refuse the offer and pay directly for special education services. In 2017‑18, California schools provided special education services to about 2,300 students attending private schools.

IDEA Is Long Overdue for Reauthorization. Between 1975 and 2004, IDEA was reauthorized four times, or about once every seven years. The last reauthorization (in 2004) was intended to extend the act through 2010. To date, Congress has made no notable effort towards a new reauthorization. The most recent reauthorization remains in effect so long as Congress continues to authorize annual appropriations to the states (as it has every year since 1975).

Major State Requirements

State Law Goes Somewhat Beyond Federal Requirements. Though states technically can opt out of IDEA, all states currently adhere to its rules and receive associated IDEA funding. (A state opting out of IDEA is still legally responsible for serving all students with disabilities.) Upon opting into IDEA in the mid‑1970s, California lawmakers enshrined most provisions of IDEA into state law. Following each subsequent reauthorization of federal law, California has made corresponding changes to state requirements. In a few areas, California law imposes additional requirements beyond IDEA. For example, state law imposes maximum caseloads on some service providers. In addition, although IDEA only requires the provision of special education until students turn age 22, state law allows students enrolled in special education programs to finish out that school year.

State Requires School Districts to Form Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). Perhaps the most notable feature of California special education law is its requirement that school districts participate in a SELPA. Each SELPA is tasked with developing a plan for delivering special education services. Small and mid‑sized districts form regional SELPAs to coordinate their special education services. Large districts are allowed to serve as their own SELPAs. Charter schools are allowed to join charter‑only SELPAs, which, unlike regional SELPAs, may accept members from any part of the state. As of 2017‑18, California has 132 SELPAs—consisting of 81 regional SELPAs, 45 single‑district SELPAs, 5 charter‑only SELPAs, and 1 unique SELPA serving only students in Los Angeles County court schools. As Figure 4 shows, regional SELPAs serve the majority of students with disabilities. The objective of SELPAs is to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of special education services by achieving certain economies of scale. (The box below provides more information about special education in charter schools.)

Special Education in Charter Schools

Charter Schools Are Nontraditional Public Schools. Charter schools are established by petition, typically authorized by local school districts, and sometimes managed by independent parties (typically nonprofit groups). Charter schools are exempt from most state education laws and are intended to provide innovative alternatives to traditional public schools. Many charter schools are small and rely on their authorizing districts to provide basic services such as processing payroll.

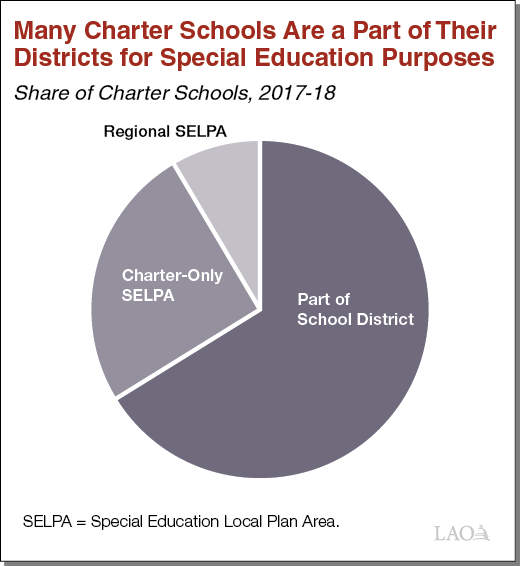

Charter Schools Must Decide How to Participate in Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). State and federal law allow charter schools to function as a part of their authorizing districts for special education purposes. In these cases, charter schools are not responsible for developing and implementing individualized education programs (IEPs), rather this responsibility falls to their authorizing districts. These charter schools receive no special education funding and have no formal decision‑making authority within SELPAs. In effect, these charter schools are treated like any other school of their authorizing district. Charter schools, however, may choose to provide special education services directly, thereby becoming responsible for their students’ IEPs. In these cases, charter schools receive special education funding and may vote in SELPA decisions. These charter schools may join either a collaborative SELPA (alongside other school districts) or a charter‑only SELPA (exclusively alongside other charter schools). As the figure below shows, the most common arrangement is for charter schools to remain a part of their authorizing districts for special education purposes.

Charter Schools Must Accept Students With Disabilities, but Serve a Smaller Share. State law requires charter schools to accept all interested students as long as their school sites have available room. Both state and federal law specifically prohibit charter schools from refusing to accept a student based solely on a disability. Despite these requirements, available data suggest charter schools are somewhat less likely than traditional public schools to serve students with disabilities. For example, about 10 percent of students attending charter‑only SELPAs have IEPs, as compared to about 12 percent of students in regional and single‑district SELPAs. Further, about 2 percent of students attending charter‑only SELPAs have relatively severe disabilities (meaning any disability aside from learning disorders, speech impairments, or health problems), as compared to about 4 percent of students in regional and single‑district SELPAs. In conversations with various stakeholders, many indicate that parents of students with disabilities (and, in particular, parents of students with relatively severe disabilities) often prefer the special education programs offered by their districts to those offered by nearby charter schools, and thus choose not to enroll their children in charter schools. Because most charter schools are small, they are often less equipped than their authorizing districts to provide a full array of services to students with disabilities.

SELPAs Provide Administrative Support and Regionalized Services. State law requires all SELPAs to collect and report certain data related to their members’ legal compliance. In addition, most SELPAs provide basic support such as in‑house legal assistance and teacher trainings. Some regional SELPAs also directly serve students with severe conditions—conditions that can be prohibitively costly to serve at the local level. For example, a SELPA may operate a special day classroom for all students with severe emotional disturbance within the region or may employ an itinerant teacher to work with all students who are deaf or hard of hearing within the region. (For more information on SELPAs, see our video How Is Special Education Organized in California?)

Students With Disabilities

Share of California Students Receiving Special Education Services Has Been Increasing. After remaining at 10.8 percent throughout the early 2000s, the share of students receiving special education has increased steadily every year since 2010‑11. In 2017‑18, 12.5 percent of California public school students received special education. Though rates have been increasing in California, all but seven states still have higher rates. In 2017‑18, the median state provided special education services to 14.3 percent of its students.

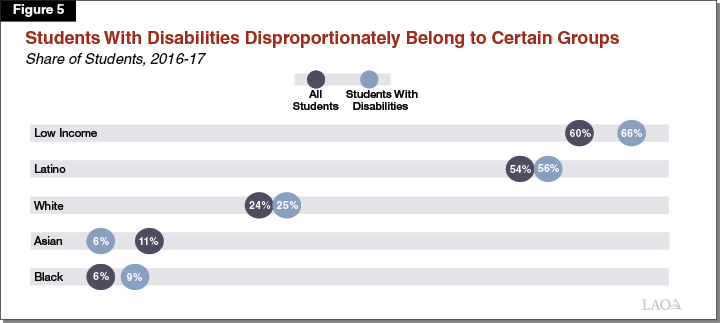

Certain Student Groups Have Relatively High Special Education Identification Rates. Figure 5 compares students with disabilities in California to the state’s overall student population by income and race/ethnicity. Compared to other California students, students with disabilities are more likely to be low income. Income status may correlate to disability status, as research has linked poor maternal health care and nutrition to higher incidence of child learning disabilities. In addition, many researchers believe cultural differences and biases contribute to racial differences in special education identification rates. Whereas Asian students have a relatively low identification rate, black students have a relatively high identification rate. The patterns across racial/ethnic groups in California are similar to patterns in other states.

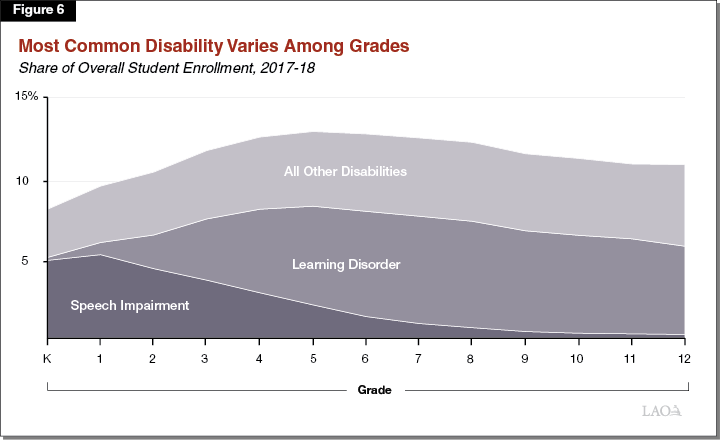

Majority of Students With Disabilities Have Relatively Mild Conditions. Figure 6 shows the prevalence of specific disabilities by grade. The majority of California students who qualify for special education have one of two types of disabilities: speech impairments (such as stuttering) and specific learning disorders (such as dyslexia). The prevalence of these disabilities varies by grade, with speech impairments being more common in the early grades and learning disorders more common in the later grades. Serving students with these types of disabilities tends to be less costly compared to students with other types of disabilities. (For more information on the prevalence of specific disabilities, see our video Who Receives Special Education?)

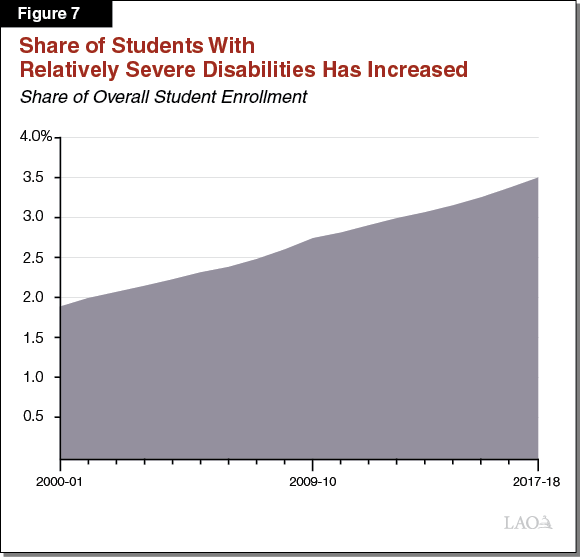

Number of Students With Relatively Severe Disabilities Has Increased Notably. As Figure 7 shows, the prevalence of students with relatively severe disabilities has almost doubled since 2000‑01. This increase is due largely to a notable rise in autism, which affected about 1 in 600 students in 1997‑98 compared to about 1 in 50 students in 2017‑18.

Incidence of Students With Disabilities Varies by Region. The overall incidence of students with disabilities varies notably among SELPAs—ranging from 4.5 percent to almost 20 percent. Large differences are evident both in the incidence of students with mild and severe disabilities. The incidence of students with relatively mild disabilities ranges across SELPAs from 4 percent to 15 percent, whereas the incidence of students with relatively severe disabilities ranges from less than 0.5 percent to 5 percent. The incidence of students with disabilities varies for at least three reasons. First, SELPAs vary in their specific practices for identifying students for special education, with some more likely to designate students with relatively mild academic or behavioral challenges as having a disability. Second, geographic factors sometimes directly affect the incidence of certain disabilities. For example, certain birth defects are more common in areas heavily impacted by drug use. Third, some areas serve as “magnets” for parents of children with specific disabilities, either because their school districts are known to have high‑quality special education programs or because other community organizations (for example, hospitals) provide high‑quality services to such children.

Special Education Services

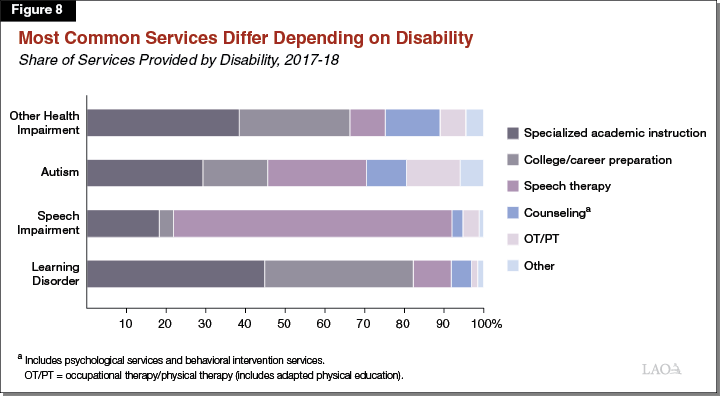

School Districts Offer Students With Disabilities Specialized Instruction and Services. Specialized academic instruction is the most common special education service school districts provide. Specialized instruction could be familiarizing a student’s general education teacher with certain instructional techniques designed to help that student or serving a student in a special day class with a teacher specifically trained to educate such children. In addition to specialized instruction, many students with disabilities receive support services such as speech therapy, physical therapy, counseling, or behavioral intervention services. Figure 8 shows the most common special education services for students with specific disabilities.

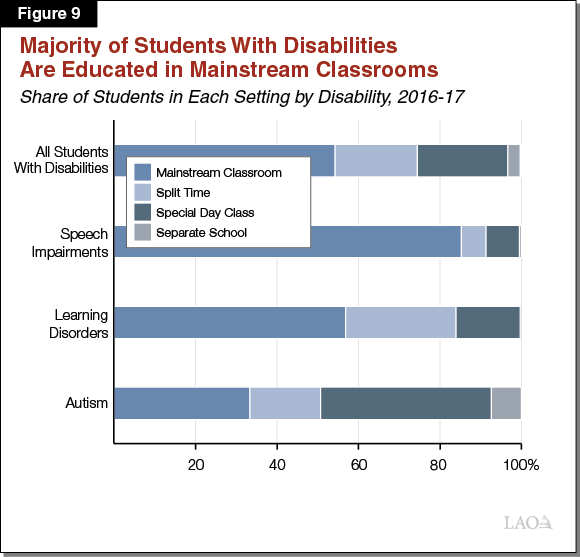

Majority of Students With Disabilities Are Served in Mainstream Classrooms. Figure 9 shows the settings in which students with disabilities are taught. The majority of students with disabilities are taught alongside students without disabilities in mainstream classrooms. These students may receive special education services within these mainstream classrooms (for example, having an aide or interpreter work with them one on one) or in separate pull‑out sessions. Students with speech impairments or learning disorders are especially likely to be served in mainstream classrooms.

Some Students With Disabilities Are Served in Special Day Classes. About 20 percent of all students with disabilities are taught primarily in special day classrooms alongside other students with disabilities. Typically, special day classes serve students with relatively severe disabilities. Some special day classes provide instruction to the entire class using specialized techniques, for example sign language. Other special day classes are organized around individual instructional modules at which students complete activities with intensive one‑on‑one attention.

Some Students Split Their Time Between Settings. Another 20 percent of students with disabilities split their time between mainstream and special day classrooms. For example, a student may spend their mornings in a special day class and afternoons in a mainstream class, or may attend a special day class for some subjects (such as reading) but a mainstream class for others (such as math).

Relatively Few Students With Disabilities Are Served in Separate Schools. Whereas special day classrooms are typically located on the same campus as mainstream classrooms, about 3 percent of students with disabilities are educated in separate schools exclusively serving students with disabilities. Typically, these students attend nonpublic schools or state special schools. A variety of agencies operate about 300 nonpublic schools, which provide services to students with disabilities under contract with school districts. Almost three‑fourths of the students served by these schools have been diagnosed with either autism or emotional disturbance (the remainder having various other health impairments or intellectual disabilities). In addition to nonpublic schools, the state directly operates two residential schools for students who are deaf and one residential school for students who are blind. The state also funds three diagnostic centers (one each in Northern, Central, and Southern California) that evaluate students with particularly challenging disabilities and assist with the development of IEPs. (For more information on the California Schools for the Deaf, see our report Improving Education for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students in California.)

Older Students With Disabilities Receive Transition Plan. When students with disabilities reach 16 years old, IDEA requires their IEP teams to develop a transition plan to help prepare them for life after high school. These plans may focus on transitioning to postsecondary education or developing specific employment skills, like operating a cash register or performing automotive maintenance. In some cases, schools work with local employers to provide part‑time work opportunities for students with disabilities prior to graduation. Transition plans also can focus on improving life skills, such as managing money or using public transportation.

Outcomes for Students With Disabilities

Students With Disabilities Score Lower on Reading and Math Tests Than Other Students. As Figure 10 shows, students with disabilities’ average test score on state reading and math assessments was at the 18th percentile of all test takers in 2017‑18. This percentile ranking is notably below that of other student groups, including low‑income students (who score at the 35th percentile) and English learners (who score at the 23rd percentile).

Students With Disabilities Have Worse Discipline and Attendance Outcomes. As Figure 11 shows, students with disabilities’ suspension rate is almost double the statewide average. Students with disabilities also have relatively high rates of chronic absenteeism, with almost one in five students with disabilities missing 10 percent or more of the school year.

Students With Disabilities Have Relatively Low Graduation Rates but Most Still Receive a High School Diploma. As Figure 12 shows, students with disabilities have a notably lower four‑year graduation rate than other student groups. Some students with disabilities, however, just take longer to graduate. Of the students with disabilities exiting high school in 2017‑18, 76 percent left with a high school diploma. Of the remaining students, 13.6 percent dropped out, 3.4 percent aged out (reaching age 22), and 7 percent received a certificate of completion (discussed below).

Some Students With Disabilities Receive Certificates of Completion in Lieu of High School Diplomas. When an IEP team determines that a student is unlikely to meet all requirements for high school graduation, the team may elect to have the student seek a certificate of completion instead of a high school diploma. Each IEP team is responsible for setting individual standards for awarding a certificate of completion. Such certificates are sometimes accepted as the equivalent of a high school diploma. For instance, some (typically private) colleges and some employers accept them, but they are not accepted by the military or for federal student aid. Most students receiving certificates of completion have relatively severe cognitive disabilities.

About One in Five Districts Have Especially Poor Outcomes for Their Students With Disabilities. California recently began implementing a new school district accountability system. As with previous accountability systems, district performance is measured overall as well as for specific student groups. In fall 2018, 343 districts (out of approximately 1,000) were identified as having poor performance with one or more of their student subgroups. Of these districts, 219 were identified because of poor outcomes for their students with disabilities.

State Created New System of Support for Districts With Poor Special Education Outcomes. Starting in 2018‑19, California is providing $10 million annually for seven SELPAs to provide statewide assistance as well as targeted assistance to districts identified as having poor outcomes for their students with disabilities. The SELPAs were selected through a competitive grant process. Three of the selected SELPAs are tasked with providing assistance in the core areas of (1) ensuring data integrity and conducting data analysis, (2) implementing effective special education practices, and (3) instituting schoolwide processes to support continuous improvement. The remaining four SELPAs are tasked with being statewide hubs of expertise in particular special education areas (including autism and special education for English learners).

Limited Data on Long‑Term Outcomes for Students With Disabilities. The federal government requires all states to annually survey students with disabilities who exited high school the previous year. The most recently available survey results for California students indicate that about half of all students with disabilities are enrolled in higher education one year after high school. By comparison, we estimate about 60 percent of all California students are enrolled in higher education one year after graduation. About a quarter of students with disabilities are competitively employed, and slightly less than 10 percent are in other types of employment or training programs (typically subsidized). We do not have good data on student outcomes beyond the first year out of high school.

Special Education Finance

In this section, we focus first on the fund sources and programs that support special education, then turn to special education costs and recent cost trends.

Funding

Most State Funding Allocated Based on Overall Student Attendance. Special education is supported by state categorical funding, federal categorical funding, and local unrestricted funding. As Figure 13 shows, California has 11 special education categorical programs, with a total of almost $4 billion in associated state funding. The largest of these state special education programs is known as AB 602 after its authorizing legislation. AB 602 provides SELPAs funding based on their overall student attendance, regardless of how many students receive special education or what kinds of services those students receive. The state shifted most special education funding into AB 602 when the program was enacted in 1997—following concerns that the state’s previous special education funding formula (which provided SELPAs differentiated rates based on the types of special education services they provided) had become too complicated and incentivized SELPAs to inappropriately identify and serve some students. Other special education programs provide funding based on alternative formulas and/or for specific types of special education services. (For more information on state funding for special education, see our post History of Special Education Funding in California.)

Figure 13

California Funds Many Special Education Programs

2018‑19 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Distribution Method |

Spending Restrictions |

Funding |

|

AB 602a |

Overall student attendance |

Any special education expense |

$3,163 |

|

Mental Health Services |

Overall student attendance |

Mental health services for students with disabilities |

374 |

|

Out‑of‑Home Care |

Location and capacity of Licensed Children’s Institutions |

Any special education expense |

140 |

|

SELPA Administration |

Overall student attendance |

SELPA‑level servicesb |

97 |

|

Infant/Toddler Services |

Number of infants and toddlers with special needs served |

Early intervention services for infants and toddlers with special needs |

80 |

|

Workability |

Number of students enrolled in employment training programs |

Job placement and training for students with disabilities |

40 |

|

Low‑Incidence Disabilities |

Number of students who are deaf, hard of hearing, visually impaired, or orthopedically impaired |

Services and materials for students with qualifying conditions |

18 |

|

SELPA Leads |

Competitive |

Support services |

10 |

|

Extraordinary Cost Pools |

Individual student placements |

Expenses associated with very high‑cost residential or nonpublic school placements |

6 |

|

Necessary Small SELPAs |

Attendance in SELPAs serving fewer than 15,000 students |

SELPA‑level servicesb |

3 |

|

Professional Development |

Overall student attendance |

Staff development |

1 |

|

Total |

$3,932 |

||

|

aSpecial education program named after authorizing legislation—Chapter 854 of 1997 (AB 602, Davis). bIncludes coordination, data management, required reporting, and fiscal administration. SELPA = Special Education Local Plan Area. |

|||

Federal Special Education Funding Follows Three‑Part Formula. As Figure 14 shows, most federal special education funding (about 60 percent), like most state funding, is allocated based on overall student attendance, regardless of how many students receive special education or what kinds of services those students receive. Of the remaining federal special education funding, most is allocated on a hold harmless basis according to the amount provided to California in 1998‑99 (the last year before the federal government revised its funding formula). The rest is allocated based on census counts of children living below poverty. As explained in the box below, California allocates the majority of federal special education to SELPAs, while reserving some funding for state‑identified priorities.

Figure 14

Federal Special Education Funding

Allocated Based on Three Factors

2018‑19 (In Millions)

|

Distribution Method |

Amount |

|

Overall student attendance |

$707 |

|

Amount received in 1998‑99 |

323 |

|

Number of children below poverty line |

125 |

|

Total |

$1,155 |

Federal Funding for State‑Identified Priorities

Some Federal Funding Used for State‑Identified Priorities and Administrative Activities. States may reserve a certain share of their federal special education funding for two types of activities. First, states may allocate some federal funding for state‑identified priorities. As the figure shows, California currently reserves $104 million of its federal funding for these priorities, which include supporting mental health services and dispute resolution. California’s allotment for these types of activities is $25 million less than the maximum amount allowed for such uses under federal law. The state currently allocates this $25 million directly to Special Education Local Plan Areas for their services. Second, states may reserve some funding for administrative activities, such as collecting and reporting data on district compliance with federal law. California currently spends the maximum amount allowed on these administrative activities ($25 million).

California Uses Some Federal Special Education Funding for Select Priorities

2018‑19 (In Millions)

|

Use |

Description |

Amount |

|

Mental Health Services |

Fund SELPAs to provide mental health services to students with disabilities. |

$69 |

|

State‑Level Services |

Support CDE and OAH in their special education‑related activities, including monitoring and litigation. |

20 |

|

State Special Schools Transportation |

Partially pay for transporting students between home and state‑run residential schools for students who are blind or deaf. |

4 |

|

Specialized Instructional Materials |

Produce and disseminate instructional materials in braille, large print, audio book, or American Sign Language video book formats. |

4 |

|

Family Empowerment Centers |

Support 14 nonprofit agencies to help educate parents about special education law and services. |

3 |

|

Alternative Dispute Resolution |

Help resolve disputes between parents and administrators without proceeding to a formal hearing. |

2 |

|

Focused Monitoring and Support |

Fund 11 consultants responsible for coordinating state efforts to monitor district compliance with federal education law and assist those failing to comply. |

1 |

|

State Systematic Improvement Plan |

Develop resources for implementing the state’s plan to improve compliance with federal law. |

1 |

|

Total |

$104 |

|

|

SELPA = Special Education Local Plan Area; CDE = California Department of Education; and OAH = Office of Administrative Hearings. |

||

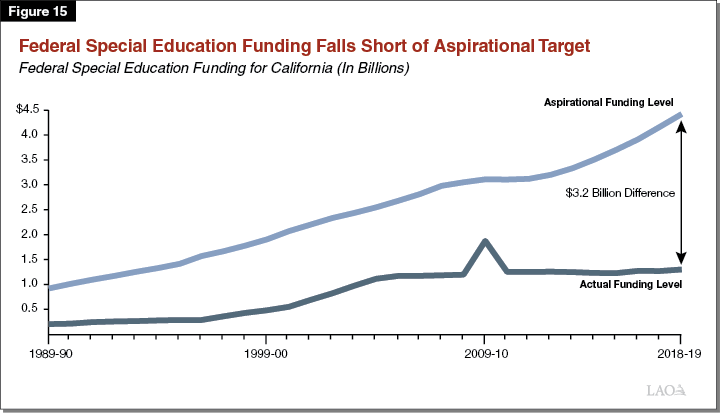

Federal Funding Falls Short of Aspirational Target. Starting in 1977, federal law established a maximum grant amount for each state equal to 40 percent of the national average per‑student educational spending amount (including special education expenditures) times the state’s population of students with disabilities. This aspirational funding level is commonly referred to as “full funding” for IDEA. As Figure 15 shows, actual federal funding to California schools has long fallen short of this target. It was $3.2 billion below the target in 2018‑19.

Most Categorical Funding Is Provided to SELPAs. With the exception of a few small categorical programs (such as funding for infant/toddler services and job placement and training for older students), most state and federal special education funding is provided to SELPAs rather than directly to school districts and charter schools. Typically, SELPAs reserve some funding for regionalized services and distribute the rest to member districts. School districts use local unrestricted funding (primarily from the Local Control Funding Formula) to support any costs not covered by state and federal categorical funding. This “local share” is intended to encourage schools to contain special education costs even while ensuring adequate services.

Federal Law Requires “Maintenance of Effort” (MOE) on State and Local Spending. In order to receive federal special education funding, both states and school districts must spend at least as much on special education each year as they did the preceding year. States and districts may choose whether their MOE is calculated on the basis of total special education spending or per‑student spending. By “locking in” increased expenditures, this requirement offers an additional incentive for the state and districts to contain special education costs.

Expenditures

Special Education Imposes Additional Costs Above and Beyond General Education. Figure 16 illustrates the average cost of educating students with and without disabilities by funding source. Students with disabilities receive some general education resources provided to all students, such as teachers, textbooks, and administrative support. In addition, each IEP imposes specific special education costs, such as the cost for smaller classes, additional teacher support, speech pathologists, audiologists, therapists, and tailored instructional equipment. In 2017‑18, special education costs averaged about $17,000 per student with disabilities, as compared to general education costs, which averaged about $10,000 per student. Accounting for both general and special education costs, students with disabilities cost on average more than two times as much to educate ($27,000) as students without disabilities ($10,000).

Special Education Costs Vary by Student. Special education is highly individualized, with some students requiring notably more intensive support and thus being more costly to serve than other students. Whereas a school district might spend $1,000 annually to provide periodic speech therapy sessions to a student with a speech impairment, it might spend more than $100,000 annually to house a student with severe emotional disturbance in an out‑of‑state nonpublic school. Service costs can vary notably even for students with the same type of disability. For example, we estimate schools annually spend between $15,000 and $100,000 per student who is deaf or hard of hearing, with costs varying based on what particular services each student is provided and in what educational setting.

Special Education Expenditures Vary by Region. In per‑student terms, special education expenditures vary notably among SELPAs. In 2017‑18, we estimate SELPAs spent an average of about $2,000 per student (spreading costs across all students in the region). Per‑student spending among SELPAs ranged from about $600 to more than $4,000. Special education expenditures vary by region for at least three reasons. First, the overall incidence of students with disabilities varies across the state. Second, even SELPAs serving similar proportions of students with disabilities may differ in the intensity of their services. Third, the cost of providing specific special education services varies by region, largely because of differences in the compensation packages that districts provide teachers and specialists.

Recent Cost Trends

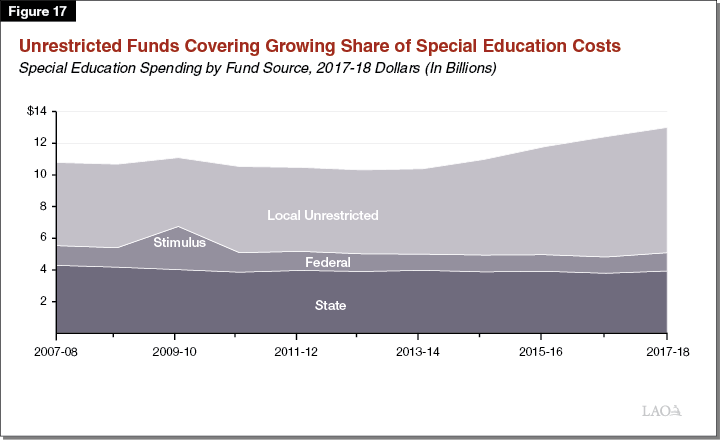

Special Education Expenditures Have Increased Notably in Recent Years. Figure 17 shows inflation‑adjusted special education expenditures by fund source between 2007‑08 and 2017‑18. During this ten‑year period, inflation‑adjusted special education expenditures increased 20 percent, from $10.8 billion to $13 billion. With the exception of an increase to federal funding as a result of stimulus legislation in 2009‑10, both state and federal funding has decreased in inflation‑adjusted terms over this period largely as a result of declining overall student attendance. Consequently, local unrestricted funding has been covering an increasing share of special education expenditures (49 percent in 2007‑08 compared to 61 percent in 2017‑18).

Expenditures Have Increased in Part Due to Spillover Effects From General Education . . . Some of the factors increasing special education expenditures are not unique to special education. In particular, since 2013‑14, increases in state K‑12 funding have resulted in school districts increasing staff salaries. Over this period, schools also have been required to make larger pension contributions on behalf of their employees. We estimate these higher compensation costs account for about one‑third of recent increases in special education expenditures.

. . . And in Part Due to an Increase in Students With Relatively Severe Disabilities. We estimate about two‑thirds of recent increases in special education expenditures are due to an increase in the incidence of students with relatively severe disabilities, particularly autism. Students with autism typically require intensive support from paraprofessionals, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, and adaptive physical education specialists, among other specialists. California schools have increased their employment of such professionals by about 20 percent since 2006‑07.

Oversight

California Department of Education (CDE) Oversees Local Compliance With Special Education Law. School districts annually submit data on certain special education indicators to CDE. For each district, the indicators track the number of students receiving special education services, the types of disabilities that students have, the district’s adherence to procedural requirements (for example, whether IEPs are held in a timely manner and include all required parties), and student outcomes. Districts may be flagged for further review or technical assistance if these indicators show noncompliance with procedural requirements, poor student outcomes, and/or significant disproportionality in the rates of identification for special education among student groups.

Federal Government Oversees State Compliance With Special Education Law. Each year, CDE compiles the data it receives from school districts into a statewide report and submits the report to the federal government. The federal Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) reviews the report along with CDE’s description of its process for identifying and assisting districts with poor indicators. Based on this review, OSEP gives California (and all other states) a grade ranging from “meets requirements” to “needs substantial intervention.” In July 2019, OSEP designated California, along with 22 other states, as “needs assistance” (for two or more consecutive years). States awarded any designation besides meets requirements may receive additional oversight or technical assistance from the federal government.

Dispute Resolution

Federal Law Allows Parents to Challenge Proposed Special Education Services. Under IDEA, states must establish a formal process for resolving disputes regarding IEP services. For example, parents who believe their child requires placement in a nonpublic school rather than their district’s own special day class must be permitted to argue their case before an administrative law judge focused on special education. In California, these disputes are resolved through the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) under a contract with CDE. Both parents and school districts may request hearings with OAH. Following a formal hearing process (which typically lasts several days), an OAH judge submits a legally binding ruling resolving each dispute.

Federal and State Law Establish Mediation Process. Because formal hearings can be costly and divisive, federal and state policies typically encourage alternative methods of dispute resolution. The most prominent alternative is mediation. During mediation, OAH assigns a trained special education mediator to works with all parties in collaboratively resolving each dispute. Typically, disputes that are not resolved during mediation proceed to a formal hearing.

Number of Disputes Has Increased. Between 2006‑07 and 2016‑17, the number of cases filed with OAH (including both hearings and mediations) increased 84 percent—growing from 2,188 cases to 4,032 cases. Some stakeholders we interviewed attribute this growth to the increase in students with relatively severe disabilities, as IEPs that involve more intensive services are more likely to generate disputes. More disputes increase districts’ administrative and legal costs.

Conclusion

Understanding how California’s students with disabilities are served is an essential step towards improving their educational outcomes and experiences. In this report, we provide a high‑level review of special education laws, services, outcomes, funding, and costs. As evident from the review, special education is characterized by a complex interplay of policies and practices at the federal, state, and local levels. Given this complexity, determining the roots of special education shortcomings, crafting potential policy responses, and identifying all the possible repercussions of proposed policy changes requires especially careful thinking and deliberation. Our intent throughout this report has been to help the Legislature understand this complexity, with the ultimate goal of better positioning the Legislature to engage with the administration in developing cost‑effective policy responses for improving special education in California.