The 2020-21 Budget:

California's Fiscal Outlook

See a list of this year's fiscal outlook material, including the core California's Fiscal Outlook report, on our fiscal outlook budget page.

LAO Contact

November 21, 2019

The 2020-21 Budget

California’s Fiscal Outlook

Cal Grant Cost Estimates

Cal Grants are the state’s main type of student financial aid. Total spending on Cal Grants has more than doubled over the past decade. In this post, we provide background on Cal Grants, describe the key factors driving recent spending increases, provide our spending estimates for 2020‑21, and discuss the spending outlook through 2023‑24.

Background

Cal Grants Assist With Tuition Costs. Cal Grants—administered by the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC)—provide gift aid to undergraduate students with financial need. Awards fully cover systemwide tuition and fees at the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) and partially cover tuition at private universities. At the California Community Colleges (CCC), a separate state-funded program waives tuition for students with financial need.

Cal Grants Also Assist Some Students With Living Costs. In addition to receiving tuition coverage, some students receive a Cal Grant access award. This award assists students with living costs such as food and housing. The maximum base access award (currently $1,672 per year) is the same across all segments. Two student groups are eligible for larger amounts of aid. Beginning in 2019‑20, Cal Grant recipients with dependent children qualify for larger access awards (of up to about $6,000 per year) at the public segments (UC, CSU, and CCC). Cal Grant recipients enrolling full time at CCC also qualify for additional aid (of up to $4,000 per year) through the Student Success Completion Grant.

Cal Grants Have Financial and Other Eligibility Criteria. Cal Grants are available to California residents, as well as certain nonresident students (including undocumented students) who previously attended a California high school or community college. Students apply for a Cal Grant by submitting a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or California Dream Act Application. To receive a Cal Grant, students must meet certain income and asset criteria, which vary by family size. For example, a dependent student from a family of four must have a family income of less than $102,500 and family assets of less than $79,300 to qualify for a Cal Grant. CSAC also requires a verified grade point average (GPA) for most Cal Grants. The minimum GPA to receive certain Cal Grant awards is 2.0, with other Cal Grant awards requiring a higher GPA. In most cases, students may renew their awards for up to four years of full-time study or the part-time equivalent.

Some Cal Grants Are Entitlements, Others Are Competitive. Recent high school graduates and transfer students under age 28 who meet the above financial and academic criteria are entitled to Cal Grants. Students ineligible for entitlement awards—typically older students who have been out of school for at a least a few years—compete for a fixed number of Cal Grant awards. State law specifies the number of new competitive awards available each year (currently 41,000).

Cal Grants Are Supported by State and Federal Funds. The 2019‑20 Budget Act provides $2.6 billion for Cal Grants. This primarily consists of $1.5 billion state General Fund and $1.1 billion federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds. (TANF also supports various programs outside CSAC—most notably the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids, or CalWORKs, program.) The budget also provides $6 million from the College Access Tax Credit Fund, a state special fund that supports a small augmentation to the access award. (The CCC Student Success Completion Grant program is supported by Proposition 98 state General Fund, separate from Cal Grant funding.)

Recent Growth Trends

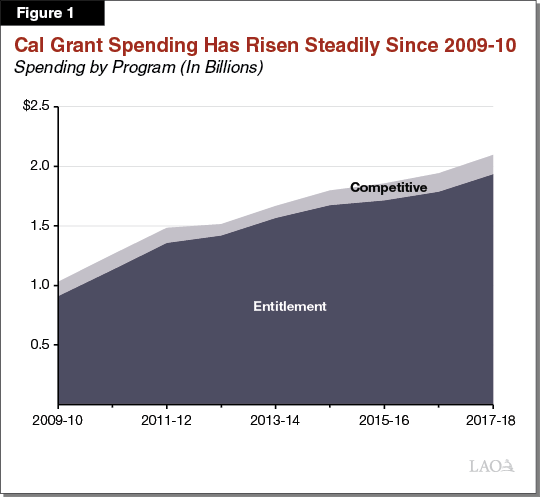

Cal Grant Spending Has More Than Doubled Since 2009‑10. As Figure 1 shows, Cal Grant spending increased from $1 billion in 2009‑10 to $2.1 billion in 2017‑18, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 9.2 percent. The bulk of increased spending over this eight-year period was due to growth in the entitlement program. Below, we first discuss the factors contributing to entitlement program growth, then focus on growth in the competitive program.

Entitlement Program

Increase in Spending Due to More Recipients and Larger Award Sizes. Figure 2 lists multiple factors contributing to growth in Cal Grant entitlement spending. Most of these factors contributed to an increase in recipients. From 2009‑10 to 2017‑18, the number of students receiving Cal Grant entitlement awards increased from 171,500 to 312,800, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 7.8 percent. The increase was particularly high at CCC and CSU, where the number of entitlement award recipients grew at average annual rates of 11 percent and 9.6 percent respectively. Larger award sizes, linked with UC and CSU tuition increases, account for the remainder of higher spending.

Figure 2

Key Factors Contributing to Growth in

Cal Grant Entitlement Spending

|

More Recipients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Larger Awards |

|

Increase in Recipients Driven in Small Part by Enrollment Growth. As undergraduate enrollment increases, the number of entitlement award recipients tends to increase. Only a small share of the growth in entitlement award recipients, however, is attributable to more undergraduate students. From fall 2009 to fall 2017, the number of undergraduates increased at an average annual rate of 0.8 percent at UC, 2.0 percent at CSU, and 2.2 percent at nonprofit colleges and universities. (The counts for UC and CSU include only resident students whereas the counts for the nonprofit sector include both resident and nonresident students.) At CCC, enrollment declined as the economy improved, with slight enrollment declines even among recent high school graduates (those eligible for entitlement awards).

Changes in Family Income Also Might Have Contributed in Small Part to the Increase in Recipients. The limited data available suggests the share of families in California meeting the financial eligibility criteria for entitlement awards may have increased from 2009‑10 to 2017‑18. Some data suggests the increase in college students coming from low- to middle-income families was most notable in the first few years of this period, then leveled off or even declined somewhat from its peak during the recession. This shift likely reflects broader statewide income trends.

Higher Application Rate Likely Explains Large Part of Increase. We estimate the percentage of high school seniors who applied for an entitlement award increased from roughly 35 percent in the 2009‑10 award year to roughly 50 percent in the 2017‑18 award year. During this time period, several policy changes simplified the Cal Grant application process. Most notably, Chapter 679 of 2014 (AB 2160, Ting) required school districts to electronically submit GPAs to CSAC for all high school seniors starting in the 2016‑17 award year. In addition, federal law extended the FAFSA application window by three months starting in 2017‑18. The increase in Cal Grant application rates may also reflect further efforts from CSAC and the segments to promote college readiness among low-income students, increase student awareness of financial aid opportunities, and support students in navigating the financial aid application process.

Paid Rate for Offered Awards Also Increased Somewhat. The percentage of students offered entitlement awards who go on to receive payments (referred to as the “paid rate”) has varied over time. The entitlement paid rate generally declined from 2009‑10 to 2012‑13. However, from 2012‑13 to 2017‑18, this rate increased steadily from 68 percent to 75 percent, thus contributing to recent increases in recipients. This trend may reflect efforts by CSAC to provide more follow-up to students offered awards and more assistance to college financial aid staff.

California Dream Act Notably Expanded Eligibility for Cal Grants. Starting in 2013‑14, Chapter 604 of 2011 (AB 131, Cedillo)—known as the California Dream Act—expanded state financial aid eligibility to certain nonresident students (including undocumented students) who attended three or more years of high school in California. (The Legislature has since expanded this law to include certain nonresident students who attended CCC.) As of 2017‑18, over 15,000 students were receiving entitlement awards under this policy. These students represent about one-tenth of the increase in entitlement award recipients since 2009‑10.

Tuition Growth Led to Increase in Award Size. Though an increase in recipients explains the majority of growth in Cal Grant entitlement spending since 2009‑10, award sizes also increased. From 2009‑10 to 2017‑18, system-wide tuition and fees increased by 41 percent ($8,898 to $12,570) at UC and 43 percent ($4,026 to $5,742) at CSU. Because Cal Grant award sizes are linked to UC and CSU tuition levels, the average entitlement award for UC and CSU students grew. The growth in average award size at UC and CSU primarily occurred from 2009‑10 to 2011‑12—the years with the largest tuition increases. Compared with the large increases in tuition awards, the access award has changed relatively little over the time period examined. The maximum access award, which is set in the annual budget act, increased 8 percent over the period (from $1,551 in 2009‑10 to $1,672 in 2017‑18).

Competitive Program

Competitive Spending Grew Because of Increase in New Awards. As with the entitlement program, an increase in recipients (rather than award size) explains most of the spending growth in the competitive program over the 2009‑10 through 2017‑18 period. State law specifies the number of new competitive awards offered each year. From 2009‑10 to 2017‑18, the Legislature raised the number of new awards offered just once—from 22,500 to 25,750 in 2015‑16. This resulted in a 15 percent increase in competitive award spending that year, followed by smaller spending increases the next few years as the larger cohorts of new recipients renewed their awards.

Near-Term Outlook

Prior- and Current-Year Spending Estimates Have Decreased Since Budget Enactment. Compared with the estimates underlying the 2019‑20 Budget Act, CSAC has adjusted its Cal Grant spending estimates downward by $138 million in 2018‑19 and $155 million in 2019‑20 (Figure 3). These adjustments are based on more recent data on award offers and payments. The downward adjustments suggest that earlier policy changes, such as extending the FAFSA application window, may already have had much of their impact, with effects now leveling off. After incorporating CSAC’s adjustments, our revised estimate of 2019‑20 Cal Grant spending is $2.4 billion. Spending growth from the revised 2018‑19 level to the revised 2019‑20 level is $272 million (13 percent).

Figure 3

Updating Prior‑ and Current‑Year Cal Grant Spending Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20a |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

June Budget Plan |

||||

|

Entitlement program |

$2,112 |

$2,281 |

$169 |

8% |

|

Competitive program |

143 |

251 |

108 |

75 |

|

Otherb |

11 |

23 |

12 |

118 |

|

Totals |

$2,266 |

$2,555 |

$289 |

13% |

|

November Estimate |

||||

|

Entitlement program |

$1,963 |

$2,103 |

$140 |

7% |

|

Competitive program |

155 |

278 |

123 |

80 |

|

Otherb |

10 |

19 |

9 |

87 |

|

Totals |

$2,128 |

$2,400 |

$272 |

13% |

|

Changec |

‑$138 |

‑$155 |

||

|

aReflects California Student Aid Commission estimates, as adjusted by LAO to incorporate policy changes. bIncludes Cal Grant C program and California Dreamer Service Incentive Grant Program. cReflects change in total spending from June budget plan to November estimate. |

||||

Budget-Year Estimates Reflect Current Law Without Further Expansions. Below, we discuss our spending estimates for the entitlement and competitive programs in 2020‑21. Our estimates reflect current law, meaning we assume no further policy changes impacting Cal Grants. We also assume the state covers all spending increases using General Fund rather than TANF. If the Legislature were to decide to use more TANF funds for Cal Grants, state General Fund costs would be reduced dollar for dollar.

Entitlement Program

Relatively Low Growth in Entitlement Spending Expected in 2020‑21. Under our outlook, budget-year spending in the entitlement program increases by $19 million (0.9 percent) over the revised current-year level of $2.1 billion. This growth rate is considerably lower than in recent years because of several assumptions. First, we assume low enrollment growth at the public and private nonprofit segments. Consistent with projections of high school graduates, our outlook assumes 1 percent enrollment growth in resident undergraduate students at UC, no growth at CSU, and no growth in the private nonprofit sector. At CCC, we assume 3 percent enrollment growth for students who are recent high school graduates. (We exclude enrollment trends among older CCC students because they are ineligible for entitlement awards.) Second, we assume no further increases in the financial aid application rate for high school seniors or the paid rate for offered awards. Third, based on recent practice at these segments, we assume no change in systemwide tuition at UC and CSU, with a 5 percent increase only to UC’s Student Services Fee. Growth in entitlement spending would be higher than we project if other key assumptions or policy decisions were made (discussed below).

Additional Enrollment Growth Would Increase Entitlement Spending. As part of the budget process, the Legislature will make enrollment growth decisions for the public segments. Higher rates of enrollment growth would lead to higher Cal Grant spending because some of the additional students would qualify for entitlement awards. We estimate every 1 percent increase in resident full-time equivalent students leads to additional entitlement spending of roughly $10 million at UC and $8 million at CSU. (Our estimates assume the newly added students at each segment would receive entitlement awards at the same rate as current students.) At CCC, additional enrollment growth could lead to higher entitlement spending, as well as Proposition 98 General Fund cost pressure in the Student Success Completion Grant program. The higher cost for entitlement awards would depend on the share of additional CCC students who are recent high school graduates.

Higher Application and Paid Rates Would Further Increase Spending. Our outlook assumes the effects of recent policy and administrative changes affecting Cal Grant application and paid rates are leveling off. Additional efforts to promote college readiness, increase student awareness of financial aid, or simplify the financial aid application and payment processes could lead Cal Grant spending increases to be higher than we project. For every 1 percentage point increase in the share of high school seniors applying for entitlement awards, we estimate Cal Grant entitlement spending would increase roughly $9 million in 2020‑21, with costs growing over the outlook period as larger cohorts of new recipients renew their awards. For every 1 percentage point increase in the paid rate for offered awards, we estimate higher Cal Grant entitlement spending of roughly $25 million.

Higher Tuition at UC and CSU Also Would Increase Entitlement Spending. Our outlook assumes a 0.4 percent increase in overall systemwide charges at UC and no tuition increase at CSU. If tuition were raised beyond these assumed levels, Cal Grant spending would increase, as the maximum award size at public universities is linked to tuition levels. We estimate every 1 percent increase in system-wide charges leads to roughly $10 million in additional Cal Grant entitlement spending at UC and $6 million at CSU.

Competitive Program

Competitive Spending Estimated to Increase 12 Percent in 2020‑21. Under our outlook, budget-year spending in the competitive program increases by $35 million over the revised current-year level, reaching $313 million in 2020‑21. The increase in spending primarily reflects the phase-in costs of two policy changes enacted in the 2019‑20 budget package. First, the Legislature increased the number of new competitive awards authorized each year from 25,750 to 41,000. The cost of this policy change will be higher in 2020‑21 because the first expanded cohort of recipients will renew their awards and another expanded cohort will receive new awards. Second, the Legislature increased the maximum access award for student parents at the public segments from $1,672 to about $6,000. With the phase in of the competitive award increase, we expect more student parents to receive awards in 2020‑21. Beyond the effects of these two policy changes, we assume a small increase in UC student charges consistent with our assumptions for the entitlement program. The small tuition increase has the same effect in both the entitlement and competitive programs of increasing the size of the associated Cal Grant award for UC students.

Outlook Through 2023‑24

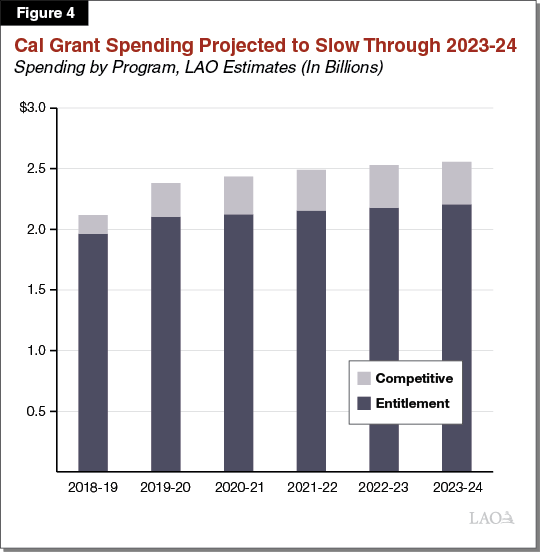

Modest Cal Grant Spending Increases Projected Through 2023‑24. Under our outlook, total Cal Grant spending (including both the entitlement and competitive programs) increases by 1 to 2 percent each year, reaching $2.6 billion in 2023‑24 (Figure 4). This rate of growth continues to be notably lower than the rate of growth from 2009‑10 through 2017‑18. The slower growth reflects an extension of the assumptions underlying our 2020‑21 estimates. Specifically, we continue to assume only a slight increase in the number of entitlement award recipients due to enrollment growth, no further increase in Cal Grant application or paid rates, and only a slight increase in overall systemwide charges at UC and no increase at CSU.

Various Reasons Cal Grant Spending Increases Could Be Higher Than Projected. As with our 2020‑21 estimates, the rate of growth in Cal Grant spending over the outlook period would be higher if certain policy decisions were made or administrative efforts taken. Notably, higher enrollment growth, higher tuition charges, further efforts to raise application or paid rates, further increases in the size of access awards, or additional increases in the number of new competitive awards would increase costs above our projections. Were any of these factors to change over the outlook period, costs could end up notably higher than our projections. For example, we estimate increasing the maximum access award by $1,000 would cost roughly $250 million—or more, if coupled with changes that increase the number of Cal Grant recipients. Costs also could be higher than we project if the state experiences an economic slowdown or downturn that causes more families to meet Cal Grant financial eligibility criteria.