LAO Contact

December 10, 2019

Preparing for Rising Seas:

How the State Can Help Support Local Coastal Adaptation Efforts

Also see this ![]() Summary Fact Sheet for the report

Summary Fact Sheet for the report

- Introduction

- California Faces Threat of Rising Seas and Tides

- Coastal Adaptation Activities Can Help Lessen SLR Impacts

- Local Responses to SLR Will Be Key to Statewide Preparedness

- California Is in Beginning Stages of Preparing for Sea‑Level Rise

- Strong Case Exists for Local Governments to Accelerate Adaptation Activities

- Local Adaptation Efforts Face Key Challenges

- State Can Help Expedite Local SLR Adaptation Efforts

- Recommendations for Legislative Steps

- Funding Options for Implementing Recommendations

- Conclusion

- APPENDIX

Executive Summary

Important for Coastal Communities to Begin Preparing for Sea‑Level Rise (SLR)

California Faces the Threat of Extensive and Expensive SLR Impacts. California’s coast could experience SLR ranging from about half of 1 foot by 2030 up to about 7 feet by 2100. Periodic events like storms and high tides will produce even higher water levels and increase the risk of flooding. Rising seas will also erode coastal cliffs, dunes, and beaches which will affect shorefront structures and recreation.

Most Responsibility for SLR Preparation Lies With Local Governments, However, the State Has a Vested Interest in Ensuring the Coast Is Prepared. Most of the development along the coast is owned by either private entities or local governments—not the state. Additionally, most land use policies and decisions are made by local governments, and they are most knowledgeable about their communities. Local governments will need to grapple with which existing infrastructure, properties, and natural resources to try to protect from the rising tides; which to modify or move; and which may be unavoidably affected. However, given the statewide risks, the state can play an important role in encouraging and supporting local efforts and helping to alleviate some of the challenges local governments face.

Many Coastal Communities Are Only in the Early Stages of Preparing for SLR. The progress of SLR preparation across the state’s coastal communities has been slow. Moreover, few coastal communities have yet begun implementing projects to respond to the threat of rising seas. Coastal communities must increase both the extent and pace of SLR preparation efforts if California is to avoid the most severe, costly, and disruptive impacts in the coming decades.

Delaying SLR Preparations Will Result in Lost Opportunities and Higher Costs. Planning ahead means adaptation actions can be strategic and phased, helps “buy time” before more extreme responses are needed, provides opportunities to test approaches and learn what works best, and may make overall adaptation efforts more affordable and improve their odds for success. The next decade represents a crucial time period for taking action to prepare for SLR.

Local Adaptation Efforts Face Several Key Challenges

Funding Constraints Hinder Both Planning and Projects. Local governments cite funding limitations as their primary barrier to making progress on coastal adaptation efforts.

Limited Local Government Capacity Restricts Their Ability to Take Action. The novelty of the climate adaptation field makes it hard for local governments to locate and hire individuals with appropriate experience and expertise.

Adaptation Activities Are Constrained by a Lack of Key Information. Local governments cite a need for additional data and technical assistance to help inform their adaptation decisions.

Few Forums for Shared Planning and Decision‑Making Impede Cross‑Jurisdictional Collaboration. Even though the interrelated effects of SLR make cross‑jurisdictional planning essential, local governments lack formal and strategic ways to learn from each other or make decisions together about coastal adaptation issues.

Responding to SLR Is Not Yet a Priority for Many Local Residents or Elected Officials. Because many California residents are not yet aware of how and when SLR might affect their communities, coastal adaptation actions are not a high priority for them to request from their local governments.

Protracted Process for Attaining Project Permits Delays Adaptation Progress. Achieving regulatory approval for coastal adaptation projects is complicated and takes a long time.

LAO Recommendations for Supporting Local Adaptation Efforts

While our recommendations represent incremental steps that will not be sufficient to address all the anticipated impacts of SLR, they represent prerequisites along the path to more robust statewide preparation.

Foster Regional‑Scale Adaptation

- Establish and assist regional climate adaptation collaborative groups to plan together and learn from each other regarding how to respond to the effects of climate change.

- Encourage development of regional coastal adaptation plans to address key risks that SLR poses to the region, as well as strategies the region will take to address them.

- Support implementation of regional adaptation efforts by contributing funding towards construction of projects identified in regional plans.

Support Local Planning and Adaptation Projects

- Increase assistance for cities and counties to conduct vulnerability assessments, adaptation plans, and detailed plans for specific projects.

- Support coastal adaptation projects with widespread benefits such as those that pilot new techniques, protect public resources, reduce damage to critical infrastructure, or address the needs of vulnerable communities.

- Facilitate post‑construction monitoring of state‑funded demonstration projects to learn more about which adaptation strategies are effective.

Provide Information, Assistance, and Support

- Establish the California Climate Adaptation Center and Regional Support Network to provide technical support and information to local governments on adapting to climate change impacts.

- Develop a standardized methodology and template that local governments can use to conduct economic analyses of SLR risks and adaptation strategies.

- Direct the California Natural Resources Agency to review and report back regarding how regulatory permitting processes can be made more efficient.

Enhance Public Awareness of SLR Risks and Impacts

- Require coastal flooding disclosures for real estate transactions to spread public awareness about SLR and allow Californians to make informed decisions about the risks of purchasing certain coastal properties.

- Require that state‑funded adaptation plans and projects include robust public engagement efforts to help develop societal awareness about SLR, build acceptance for adaptation steps, and ensure the needs of vulnerable communities are addressed.

- Direct state departments to conduct a public awareness campaign about the threats posed by SLR to develop public engagement in and urgency for taking action.

Introduction

State’s Climate Change Response Will Require Both Mitigation and Adaptation. In recent years, California has taken steps to limit the effects of climate change by enacting policies and programs to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. While these efforts—if combined with similar global initiatives—ultimately may constrain the total amount of warming the planet experiences, scientists are conclusive that some degree of climate change already is inevitable. The changing climate will have several consequential effects on California over the coming decades. Indeed, such impacts have already begun. In recent years, the state experienced a severe drought, multiple serious wildfires, and periods of record‑breaking heat, all of which scientists suggest likely are harbingers of future conditions. In addition to these more episodic events, science has shown that the changing climate will result in a gradual and permanent rise in global sea levels. Given the significant natural resources, public infrastructure, housing, and commerce located along California’s 840 miles of coastline, the certainty of rising seas poses a serious and costly threat. As such, in the coming years the state will need to broaden its focus from efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change to also undertake initiatives centered on how communities can adapt to the approaching impacts.

Report Responds to Increasing Legislative Interest in Climate Adaptation. This report responds to increasing legislative interest in determining how the state can best prepare for the impacts of climate change, including sea‑level rise (SLR). In recent years, the Legislature has held several hearings on SLR and coastal adaptation, formed two related select committees, and deliberated multiple legislative proposals on these topics. In addition, the Governor and some legislative members have indicated interest in placing a new general obligation bond on the 2020 ballot for voter approval that would provide funding for climate adaptation activities.

Report Focuses on How State Can Support Local Coastal Adaptation Efforts. Although the risk presented by SLR is an issue of statewide importance, most of the work to prepare for and respond to these changes has to take place at the local level. This is because most of the development along the coast is owned by either private entities or local governments—not the state. Additionally, most land use policies and decisions are made by local governments, and they are most knowledgeable about the needs and specific circumstances facing their communities. However, the state can play an important role in encouraging and supporting local efforts and helping to alleviate some of the challenges that local governments face in preparing for SLR. Given the importance of protecting the state’s residents, economy, and natural resources from considerable damages, this report focuses on how the Legislature can help support and expedite progress in preparing for rising seas at the local level. (While the state will also need to take action to prepare for potential impacts to assets for which it has primary responsibility—like coastal highways and state parks—consideration of those steps is outside the scope of this report.) This focus and our recommendations represent a continuation of the state’s long‑standing role in facilitating and incentivizing implementation of state objectives at the local level. While adopting our recommended actions will not be sufficient to address all the projected impacts of SLR, they represent important incremental steps towards greater preparation across the state.

Findings Informed by Extensive Interviews and Research. The findings and recommendations presented in this report are informed by interviews we conducted with over 100 individuals. These interviewees represented local governments from across the state, academic researchers, community groups, nongovernmental organizations, federal agencies, and state departments. We also reviewed relevant reports and academic literature, including several statewide surveys conducted on the topics of coastal adaptation, climate change preparation, and local government planning. The resources we reference within the report are listed in the “Appendix.”

California Faces Threat of Rising Seas and Tides

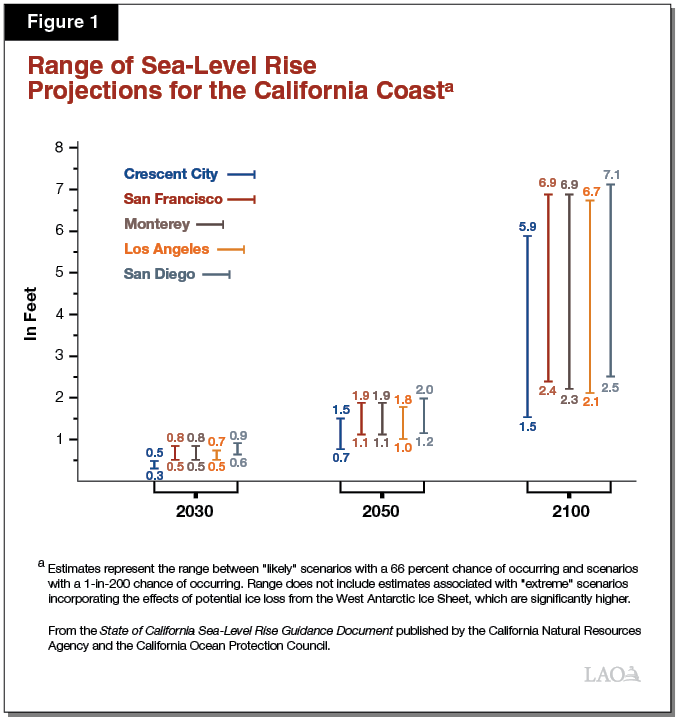

Coast Will Experience Encroaching Seas in Coming Decades. Climate scientists have developed a consensus that one of the effects of a warming planet is that global sea levels will rise. The degree and timing of SLR, however, is still uncertain, and depends in part, upon whether global greenhouse gas emissions and temperatures continue to increase. Figure 1 displays recent scientific guidance compiled by the state for how sea levels may rise in various coastal areas of California in the coming decades. As shown, the magnitude of SLR is projected to be about half of 1 foot in 2030 and as much as 7 feet by 2100. The estimates shown in the figure represent the range between how sea levels might rise across the state under two different climate change scenarios. The bottom end of the range reflects the lower bound of a “likely” scenario (with a projected 66 percent chance of occurring). The top end reflects the upper bound of a higher risk and more impactful scenario (with a projected 1‑in‑200 chance of occurring). As shown, the range between these scenarios is greater in 2100, reflecting the increased level of uncertainty about the degree of climate change impacts the planet will experience further in the future.

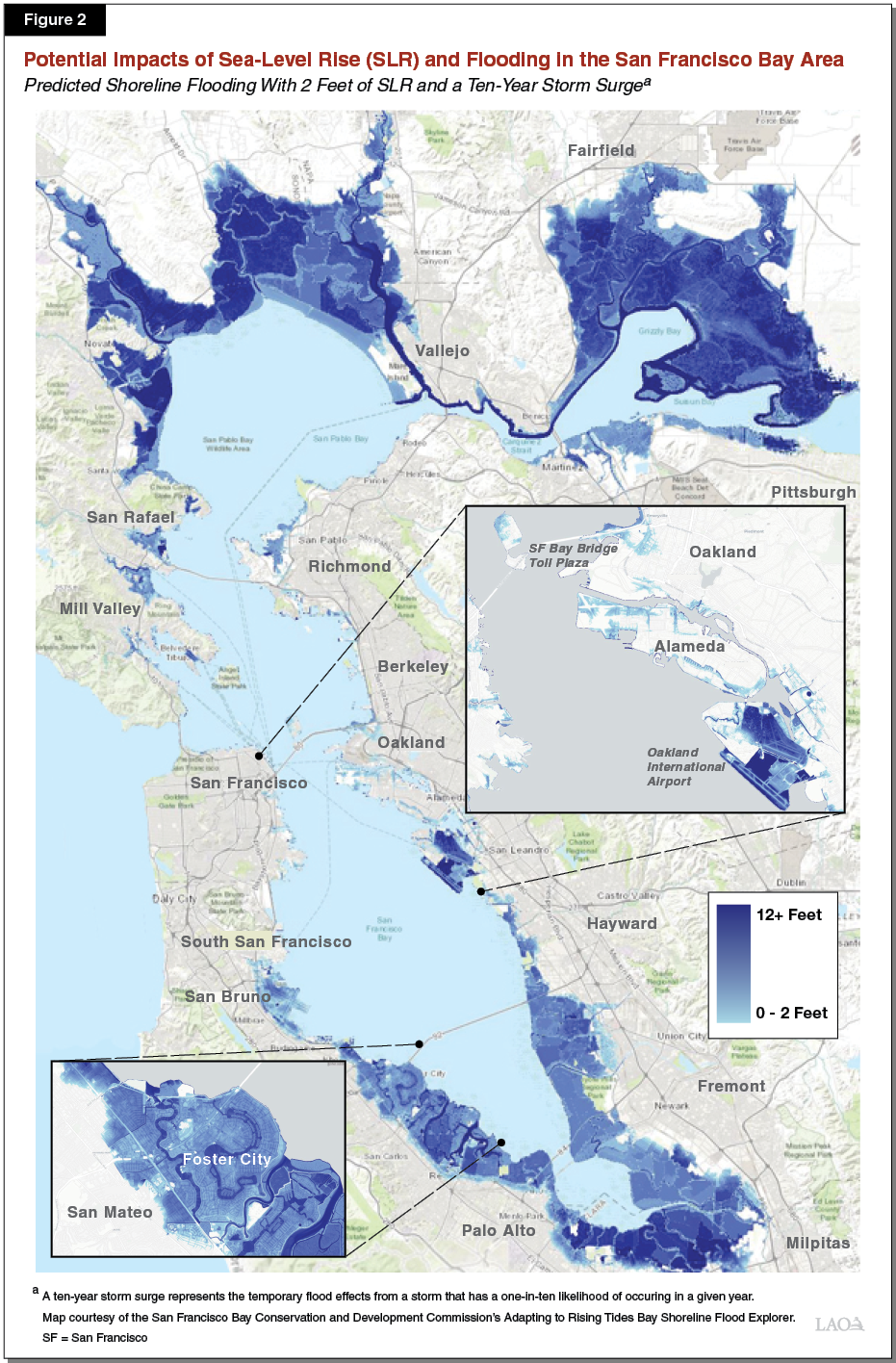

Figure 2 displays a detailed map of how current SLR projections translate into potential flooding in the San Francisco (SF) Bay Area. The map shows flooding projected to occur with 2 feet of SLR combined with a ten‑year storm surge (that is, the temporary flood effects from a storm that has a one‑in‑ten likelihood of occurring in a given year). This combination of events would result in a total water level of over 4 feet. As shown, under this scenario—and given existing shoreline protections and conditions—many portions of the SF Bay shoreline would become inundated. For example, as highlighted in the map, this would result in severe flooding for Foster City, the Oakland International Airport, and the toll plaza for the SF Bay Bridge in Oakland. This combination of SLR and storm is well within the range of possibilities that could occur within the next 50 years. Combining a significantly high‑tide event with SLR would result in even more severe flooding across the region than that shown in this map.

Storms and Future Climate Impacts Could Raise Water Levels Further. Although they would have substantial impacts, the SLR scenarios displayed in Figure 1 likely understate the increase in water levels that coastal communities will actually experience in the coming decades. This is because climate change is projected to contribute to more frequent and extreme storms, and the estimates shown in Figure 1 do not incorporate potential increases in sea levels caused by storm surges, exceptionally high “king tides,” or El Niño events. These periodic events could produce notably higher water levels than SLR alone. Moreover, the data displayed in the figure do not include significantly higher estimates associated with “extreme” scenarios that incorporate the effects of potential ice loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The likelihood of these severe scenarios occurring is still uncertain, but possible. If there is considerable loss in the polar ice sheets, scientists estimate that San Francisco could experience over 10 feet of SLR by 2100.

SLR Impacts Have Potential to Be Extensive and Expensive. The potential changes in sea levels and coastal storms will impact both human and natural resources along the coast. These events will increase the risk of flooding and inundation of buildings, infrastructure, wetlands, and groundwater basins. A 2015 economic assessment by the Risky Business Project estimated that if current global greenhouse gas emission trends continue, between $8 billion and $10 billion of existing property in California is likely to be underwater by 2050, with an additional $6 billion to $10 billion at risk during high tide. A recent study by researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates that by 2100, roughly 6 feet of SLR and recurring annual storms could impact over 480,000 California residents (based on 2010 census data) and $119 billion in property value (in 2010 dollars). When adding the potential impacts of a 100‑year storm, these estimates increase to 600,000 people and over $150 billion of property value.

Rising seas will also erode coastal cliffs, dunes, and beaches—affecting shorefront infrastructure, houses, businesses, and recreation. The state’s Safeguarding California Plan cites that for every foot of SLR, 50 to 100 feet of beach width could be lost. Moreover, a recent scientific study by USGS researchers predicted that under scenarios of 3 to 6 feet of SLR—and absent actions to mitigate such impacts—up to two‑thirds of Southern California beaches may become completely eroded by the year 2100. Such a loss would impact not only Californians’ access to and enjoyment of key public resources, but also beach‑dependent local economies. While no entity has completed a comprehensive economic assessment of beach‑related recreation across the state, a 2016 report by the Center for the Blue Economy estimated that California’s ocean economy—including tourism, recreation, and marine transportation—is valued at over $44 billion per year.

SLR Impacts Could Have Fiscal Implications at Both Local and State Levels. The potential impacts of SLR also could have negative impacts on the economy and tax base—both locally and statewide—if significant damage occurs to certain key coastal infrastructure and other assets. These include ports, airports, railway lines, beaches and parks used for recreation, and high‑technology companies located along the SF Bay. Furthermore, if property values fall considerably from the increased risk and frequency of coastal flooding, over time this will affect the annual revenues upon which those local governments depend. To the degree local property tax revenues drop, this also could affect the state budget because the California Constitution requires that losses in certain local property tax revenues used to support local schools be backfilled by the state’s General Fund.

SLR Threatens Vulnerable Populations. Not all of the assets threatened by SLR are expensive homes and affluent communities. In contrast, many communities with more vulnerable populations also face the risk of more frequent flooding. Such populations include renters (who are less able to prepare their residences for flood events), individuals not proficient in English (who may not be able to access critical information about potential SLR impacts), residents with no vehicle (who may find it more difficult to evacuate), and residents with lower incomes (who have fewer resources upon which to rely to prepare for, respond to, and recover from flood events). For example, a 2012 study conducted by the SF Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (BCDC) Adapting to Rising Tides Project found that SF Bay Area locations at risk of inundation from SLR included more than 9,000 renter‑occupied households, over 2,500 linguistically isolated households, over 2,000 households with no vehicle, and over 15,500 individuals living in households earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Coastal Adaptation Activities Can Help Lessen SLR Impacts

While the estimates cited above highlight the potential damages, costs, and disruption that SLR could cause, strategies for moderating such impacts exist.

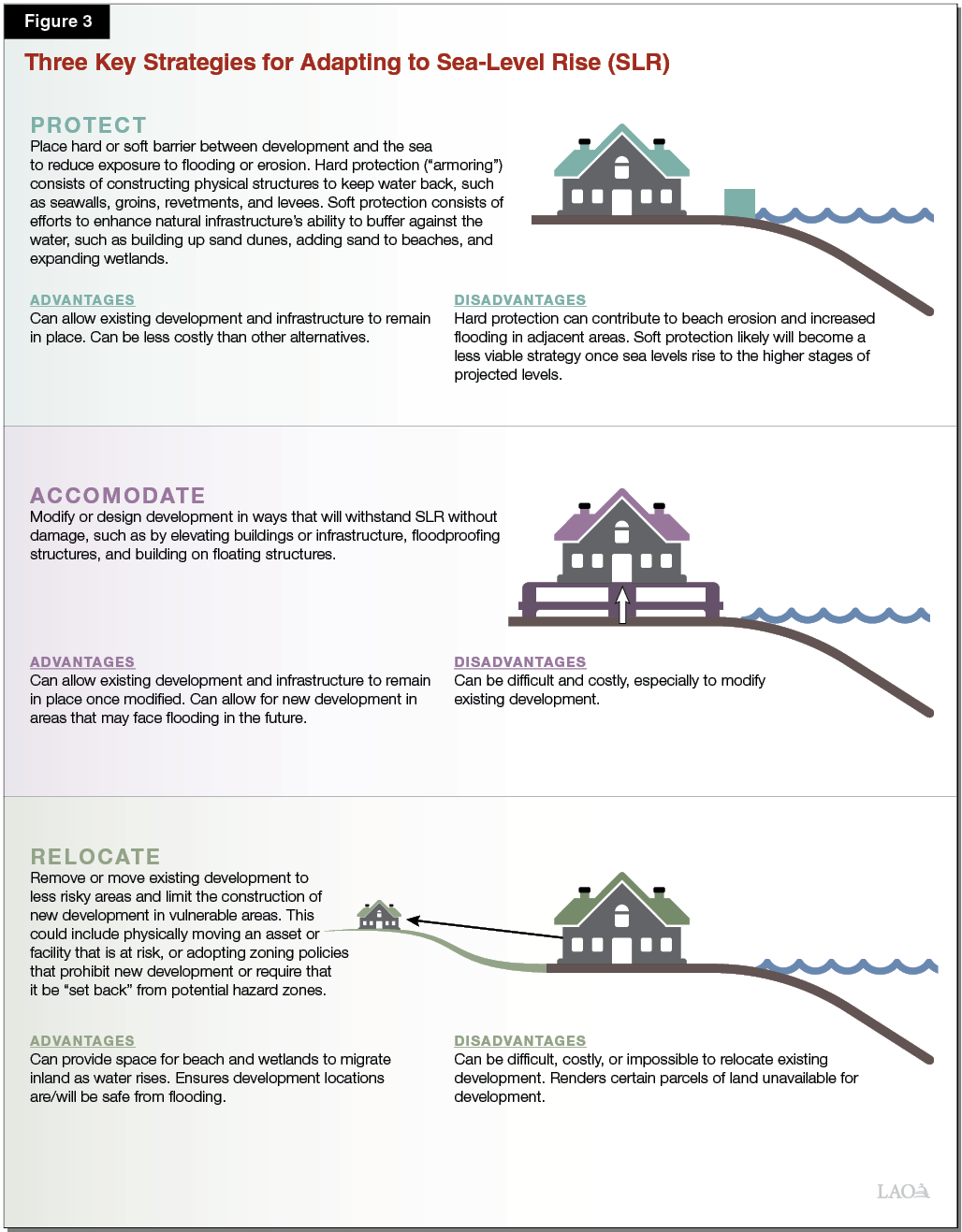

Three Primary Options Exist for Adapting to SLR. The state, coastal communities, and private property owners essentially have three categories of strategies for responding to the threat that SLR poses to assets such as buildings, other infrastructure, beaches, and wetlands. As shown in Figure 3, they can (1) build hard or soft barriers to try to stop or buffer the encroaching water and protect the assets from flooding, (2) modify the assets so that they can accommodate regular or periodic flooding, or (3) relocate assets from the potential flood zone by moving them to higher ground or further inland. Each of these options comes with trade‑offs, as discussed in the figure, and not all strategies will work in every situation. Communities and residents are understandably reluctant to relocate existing properties, as this will be disruptive, expensive, and in some cases not logistically possible. Armoring much of the coast to protect most assets, however, also is not practical. Not only would such an approach be prohibitively expensive and have decreasing effectiveness over the years as more intense wave action migrates inland, it also would disrupt natural erosion processes such that it would cause much of the sand on the state’s beaches to disappear.

Selecting which combination of SLR adaptation approaches to use in a particular location is an involved process necessitating scientific research, locally specific information, public and stakeholder input and support, both high‑level and detailed planning, and—in many cases—additional funding. Local governments planning for SLR are also balancing other—and sometimes competing—land use objectives. As we discuss in the nearby box, SLR presents particular challenges for coastal jurisdictions—and the state—seeking to expand the supply of housing units. Undertaking Coastal Adaptation Activities Likely Less Costly Than Avoiding Action. The types of adaptation efforts described in Figure 3 can not only help mitigate disruptive SLR impacts, in many cases they also make sense from a fiscal perspective. That is, while such activities might require up‑front investments, the costs of failing to adequately prepare for the impacts of SLR likely would cost even more. Recent research found a strong benefit‑to‑cost ratio for undertaking mitigation projects ahead of disasters compared to spending on disaster response and recovery. Specifically, a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)‑sponsored study by the National Institute of Building Sciences found that for every $1 the federal government invested in various types of pre‑disaster mitigation activities in recent years, it avoided public and private losses totaling $6. Designing new structures to be more resilient to natural hazards was also found to be financially advantageous. For example, in the case of riverine flooding, the study estimates that for every extra $1 spent to build new buildings higher out of the floodplain than international building codes require, $5 in flood damage‑related costs was avoided. While the study was based on retrospective data on other types of disasters and did not consider future SLR‑related coastal flooding, similar principles likely apply. That is, investing in adaptation activities that will help to mitigate significant flooding, damage, disruption, and erosion that will otherwise occur from SLR is almost certainly a less costly approach overall compared to not taking such actions.

SLR Complicates State’s Housing Objectives

The potential impacts of sea‑level rise (SLR) create complications for a different state and local priority—increasing housing availability and affordability. California faces a serious housing shortage, and the state’s coastal areas are experiencing the most acute population growth, high housing costs, and demand for more affordable housing. Our office has estimated that on top of the 100,000 to 140,000 housing units typically built in the state each year, California probably would have to build as many as 100,000 additional units annually—almost exclusively in its coastal communities—to seriously mitigate housing affordability problems. In recent years, the state has implemented a number of measures intended to encourage local governments to build more housing, including providing additional funding and instituting new penalties for jurisdictions that fail to comply with state housing laws.

Flooding caused by SLR poses two serious impediments to coastal jurisdictions seeking to meet these state housing objectives. First, over the coming decades some existing housing units along the coast will experience regular flooding and become uninhabitable. Second, some parcels of land that do not currently contain housing—and therefore may seem like apt locations for new development—also face the likelihood of flooding in future years. While local governments may be reluctant to adopt policies restricting development on these parcels given their current viability, the future hazards make them risky locations to construct new housing. Certain adaptation strategies described in Figure 3 could help to safeguard some existing properties and land parcels from the effects of SLR—including protecting them through armoring, or building or retrofitting structures such that they can accommodate flooding. As described in the figure, however, these strategies come with trade‑offs, including costs and effects on adjacent areas. The degree of SLR that is predicted over the next century clearly will affect land use decisions and create additional challenges for local governments—and the state—as they seek to expand housing options for Californians in coastal regions.

Local Responses to SLR Will Be Key to Statewide Preparedness

Most Responsibility for SLR Preparation Lies With Local Governments . . . Most of the development along the coast is owned by either private entities or local governments—not the state. Additionally, most land use policies and decisions are made at the local level, and local governments are most familiar with the specific circumstances facing their communities. As such, responsibility to prepare for and respond to the impacts of SLR lies primarily with the affected local communities. Deciding how to confront these challenges and implement the strategies described in Figure 3 will be both difficult and costly. Local governments will need to grapple with which existing infrastructure, properties, and natural resources to try to protect from the rising tides; which to modify or move; and which may be unavoidably affected.

. . . However, the State Has a Vested Interest in Ensuring the Coast Is Prepared. As discussed in more detail later in this report, the 1976 California Coastal Act grants the state special jurisdiction over land use decisions along the coast. Specifically, unlike other areas of California, along certain portions of the coast the state possesses the authority to regulate activities that change the intensity of use of land, with the intended goal of balancing development with protecting the environment and public access. This authority, combined with a motivation to minimize costly and traumatic damage for residents and their property, creates a strong rationale and incentive for the state to help ensure that local jurisdictions plan for and take action to adapt to SLR. Californians could experience serious public health and safety impacts if local governments do not take proper steps to prepare for how SLR will affect certain coastal infrastructure. Such impacts include threats to drinking water (from impacts to coastal groundwater aquifers and water treatment plants, and damage to levees in the Sacramento San Joaquin Delta), sewage treatment, local transportation infrastructure, and other essential facilities such as hospitals and schools. Moreover, the state is charged with overseeing natural resources on behalf of the public trust and, thus, is responsible for ensuring the preservation of public access to the coast and the health of coastal wetlands, wildlife, and habitats. As discussed earlier, SLR damages also would have fiscal implications, which the state will want to try to minimize.

California Is in Beginning Stages of Preparing for Sea‑Level Rise

In this section we discuss how the state, federal, and local governments currently are engaged in preparing to adapt to the impacts of SLR.

State‑Level Efforts

Multiple State Departments Have SLR‑Related Responsibilites. As summarized in Figure 4, a number of state departments are engaged in efforts to prepare for and respond to the impacts of SLR. Additionally, senior‑level staff from each of the departments shown in the figure—together with representatives from the Delta Stewardship Council—meet periodically to discuss statewide policy and priorities through a Sea‑Level Rise Leadership Team they have formed. Besides the activities described in the figure, many state departments also are taking initial steps to assess how SLR will impact the state facilities and essential services for which they are responsible. Such steps were spurred by Governor Schwarzenegger’s Executive Order S‑13‑08 (which in 2008 directed state agencies to begin planning for SLR and climate impacts), and several iterations of the Safeguarding California Plan (which was compiled by the California Natural Resources Agency [CNRA] and serves as the roadmap for steps that state agencies and departments should take to respond to the changing climate). One department managing significant state assets that are at risk from SLR is the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), which manages state highways along the coast. Another is the Department of Water Resources, which manages the State Water Project, a water conveyance system that is highly dependent on the integrity of the levees in the Sacramento San Joaquin Delta to successfully move drinking water from the northern to the southern part of the state.

Figure 4

State Departments With Major Sea‑Level Rise (SLR) Related Responsibilities

|

Department |

Primary SLR‑Related Responsibilities |

|

California Coastal Commission |

Regulates the use of land and water in the coastal zone, excluding the San Francisco (SF) Bay Area. (The coastal zone generally extends 1,000 yards inland from the mean high tide line.) Reviews and approves Local Coastal Programs (LCPs)—plans that guide development in the coastal zone. Maintains permitting authority over proposed projects in areas in the coastal zone with no approved LCP and for state‑managed lands such as state parks. |

|

SF Bay Conservation and Development Commission |

Reviews and issues regulatory permits for projects that would fill or extract materials from the SF Bay, and works to preserve public access along the bay’s shore. Participates in the SF Bay Area’s multiagency regional effort to address the impacts of SLR on shoreline communities and assets. Administers the Adapting to Rising Tides Program to support SLR‑related planning and projects in the SF Bay Area. |

|

Ocean Protection Council |

Allocates grants for SLR and coastal adaptation projects and research. Conducts and distributes data and information to help local jurisdictions and state departments plan for SLR, including developing the State of California Sea‑Level Rise Guidance Document. |

|

State Coastal Conservancy |

Allocates grants for and undertakes projects to preserve, protect, and restore the resources of the California coast and the SF Bay Area. Provides grants for planning and projects through its Climate Ready Program to increase the resilience of coastal communities and ecosystems to climate change impacts such as SLR. |

|

State Lands Commission |

Stewards sovereign state lands, including those located between the ordinary high water mark of tidal waters and the boundary between state and federal waters three miles offshore. Monitors sovereign state lands the Legislature has delegated to local municipalities to manage in trust for the people of California. |

|

Governor’s Office of Planning and Research |

Administers the Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resilience Program, which includes a web‑based clearinghouse that compiles information about climate change adaptation research and projects, including those related to SLR. |

|

Department of Parks and Recreation |

Owns and manages more than one‑quarter of California’s coastline. Responsible for protecting and conserving these beaches, wetlands, and other coastal resources on behalf of the public. |

Additional Departments May Have More Involvement With SLR Adaptation in the Future. Two state departments not shown in Figure 4 that have had limited involvement with SLR activities thus far but may have increased roles in the future are the Strategic Growth Council (SGC) and California Office of Emergency Services (CalOES). Currently, SGC administers several state programs that are primarily designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and its engagement on SLR‑related issues has been relatively limited. As the state expands its focus beyond climate change mitigation into a greater emphasis on adaptation, however, the Legislature may choose to task SGC with additional responsibilities given the Council’s experience in managing climate‑related programs. Additionally, CalOES directs disaster preparedness and response activities in California, including overseeing local disaster mitigation planning efforts and administering associated federal programs and funding. Correspondingly, as California communities increase preparation for and begin to experience the impacts of SLR, CalOES likely will play a role in supporting such efforts.

State Has Been Engaged in SLR Planning, Data Collection, and Information Dissemination. The state has published a number of reports in recent years concerning SLR projections and steps the state and local governments might take to respond. Among these is the State of California Sea‑Level Rise Guidance Document, which was initially adopted in 2010 and most recently updated in 2018. This document—developed by the Ocean Protection Council (OPC) in coordination with other partner agencies—provides (1) a synthesis of the best available science on SLR projections and rates for California, (2) a stepwise approach for state agencies and local governments to evaluate those projections and related hazard information in their decision‑making, and (3) preferred coastal adaptation approaches. Other SLR‑related plans and reports the state has released in recent years include several iterations of the aforementioned Safeguarding California Plan (each of which consists of multiple companion reports), four California Climate Change Assessment reports (also encompassing multiple companion reports), the California State Hazard Mitigation Plan, and Paying It Forward: The Path Toward Climate‑Safe Infrastructure in California.

Additionally, pursuant to Chapter 606 of 2015 (SB 246, Wieckowski), the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) operates the Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resilience Program. This program is intended to develop a cohesive and coordinated response to the impacts of climate change across the state and has two components. First, a Technical Advisory Council helps OPR and the state improve and coordinate climate adaptation activities. Second, OPR has created a searchable online public database of adaptation and resilience resources—known as the State Adaptation Clearinghouse—including some related to SLR and coastal adaptation. The Clearinghouse includes resources such as local plans, educational materials, policy guidance, data, research, and case studies.

State departments have undertaken certain other initiatives to support SLR‑related activities around the state, some of which are mentioned in Figure 4. For example, BCDC has developed the Adapting to Rising Tides Program which provides adaptation planning support, guidance, tools, and information to SF Bay Area agencies and organizations. BCDC has also developed detailed maps of how potential future flooding might impact the SF Bay region. The State Coastal Conservancy (SCC) has developed additional SLR resources and helps to coordinate the California Coastal Resilience Network, which presents monthly webinars on coastal adaptation. OPC has undertaken several initiatives, including a recently enacted contract to conduct a relatively small‑scale public awareness campaign about the risks associated with SLR.

State Has Provided Limited Funding for Coastal Planning and Projects. In addition to undertaking state‑level planning and research, the state has also provided some limited funding for SLR planning and projects. Figure 5 summarizes the funding appropriated by the Legislature for coastal adaptation activities over the past five years (2014‑15 through 2019‑20), totaling $67 million. These funds have been provided from a variety of sources. The Legislature has utilized bonds as the largest source of funding for these coastal adaptation activities ($26 million), followed by the Environmental License Plate Fund ($17.5 million) and the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund ($14.8 million). Much of this funding has been or will be used for grants to local governments and nongovernmental organizations for planning and projects, including through SCC’s Climate Ready Program. The totals shown in the figure include $25 million for OPC and nearly $4 million for SCC appropriated in the 2018‑19 Budget Act that can be used for coastal adaptation projects, some of which likely has not yet been allocated for specific projects. In addition, a portion of the funds have been used for state department staff to undertake activities that assist local governments, such as staff support from BCDC and the Coastal Commission for local planning efforts.

Figure 5

Summary of Recent State Funding for Coastal Adaptation

2014‑15 Through 2019‑20 (In Millions)

|

Department |

Primary Uses |

Amount |

|

Ocean Protection Council |

Grants for adaptation projects, statewide research projects. |

$34.6 |

|

State Coastal Conservancy |

Grants for sea‑level rise planning, grants for adaptation projects. |

15.4 |

|

California Coastal Commission |

Grants for local adaptation planning and to update Local Coastal Programs, staff support for those local planning efforts. |

14.0 |

|

San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission |

Regulatory review of adaptation projects, grants for sea‑level rise planning, staff support for regional planning efforts. |

3.3 |

|

Total |

$67.3 |

In addition to the funding specifically for coastal adaptation shown in Figure 5, some other state funds have supported related work in recent years. This includes a program run by the Division of Boating and Waterways within the Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) that allocates grants for local beach erosion control and sand replenishment projects. Some other funding has been provided through sub‑grants from other state departments. For example, both BCDC and some local governments have received funding from Caltrans for coastal adaptation planning and projects that involve transportation infrastructure. Some of BCDC’s work supporting adaptation planning in the SF Bay Area has also been supported by some small grants from the Delta Stewardship Council, and SCC has received grants from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for wetlands restoration projects.

Federal‑Level Efforts

Federal Government Has Supported Some Coastal Adaptation Activities in California. In general, the federal government’s role in preparing for SLR in California has largely been to support the state and local agencies by providing technical assistance, scientific research and information, and some limited funding. The primary federal agencies engaged in SLR‑related activities in California are the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and USGS. As discussed in the nearby box, FEMA has not had much involvement in coastal adaptation activities thus far, but likely will play a larger role in the future.

Role of FEMA in Coastal Adaptation

FEMA Helps Communities Prepare for and Respond to Disasters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) works with the California Office of Emergency Services (CalOES) to help prepare for and recover from disasters. Therefore, like CalOES, FEMA likely will play a role in supporting the state’s coastal communities as they get ready for and respond to sea‑level rise (SLR) impacts. Such efforts could include providing federal disaster mitigation funding for projects designed to reduce the future impacts of SLR. After a state experiences a federally declared disaster, FEMA provides it with funding to undertake activities intended to lessen the impacts of future disasters through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. For example, in 2018 (after experiencing several wildfire disasters) California received over $500 million in disaster mitigation funding from FEMA. The state also received close to $500 million in 2017, when federal disasters were declared after wildfires and severe storms.

FEMA Funds Could Be Used for Coastal Adaptation Projects. While the Legislature could help identify priorities for the use of such funds, thus far it has deferred to CalOES to select which areas of focus and specific projects to support—subject to approval from FEMA—when the state receives disaster mitigation funds. In general, CalOES has opted to use such funds to prevent future disasters of the type that recently occurred. For example, it plans to use essentially all of the 2018 funding on wildfire mitigation projects. However, this is not a FEMA‑imposed requirement. While FEMA does have some requirements around how disaster mitigation funds must be used—including that funded projects meet its cost‑benefit analysis parameters—it allows these funds to be used to help lessen the potential impacts of many types of disasters, not just those that a state recently experienced. As such, the state could use FEMA pre‑disaster funds for coastal adaptation projects to mitigate future SLR‑related flooding—even if FEMA provides the funds after the state experiences wildfire‑related disasters. CalOES indicates it plans to use about $50 million from the 2017 allocation of federal disaster mitigation funds for coastal projects. In general, however, this has not been a primary area of focus for such funds thus far.

NOAA Provides Technical Assistance and Some Funding. NOAA works collaboratively with the state to implement the federal Coastal Zone Management Act and help protect coastal resources. Significant SLR‑related initiatives that NOAA is undertaking in California include providing training on coastal adaptation planning, developing tools (including the “Sea Level Rise Viewer” that provides detailed digital maps of potential SLR flooding), and collaborating on data collection initiatives. In addition, NOAA annually provides funding to the three state departments designated to help implement the Coastal Zone Management Act—the Coastal Commission, BCDC, and SCC. Between 2016 and 2019, NOAA allocated a total of about $11 million to these three departments for their ongoing coastal management activities, of which about $1.8 million was explicitly for SLR‑related projects and policy development. NOAA has also provided some specific one‑time grants to state departments and local governments for SLR‑response initiatives in California, including $690,000 to San Diego County for a coastal resiliency project described below.

USGS Provides Scientific Research and SLR Modeling. Unlike NOAA, USGS does not give out grants to the state or local agencies; rather, USGS undertakes scientific research, which those agencies can then utilize. The largest SLR‑related activity in which USGS is engaged in California is development of the Coastal Storm Modeling System (CoSMoS). This is a dynamic modeling approach that integrates predictions for (1) future SLR, (2) future coastal storms, and (3) long‑term evolving coastal trends such as erosion to beaches and bluffs. Because it forecasts the potential interactions of these multiple events and impacts, this tool—which USGS has already completed for most of the state—allows for more detailed local predictions of future coastal flooding than models which only predict SLR. (The state has also contributed some funding to help develop CoSMoS.) In addition to developing CoSMoS, USGS is engaged in various other scientific research endeavors that relate to SLR, including monitoring coastal erosion and groundwater hazards, sea‑floor mapping, and the Hazard Exposure Reporting and Analytics project that assesses the potential socioeconomic impacts of SLR within California’s coastal communities.

Local‑Level Efforts

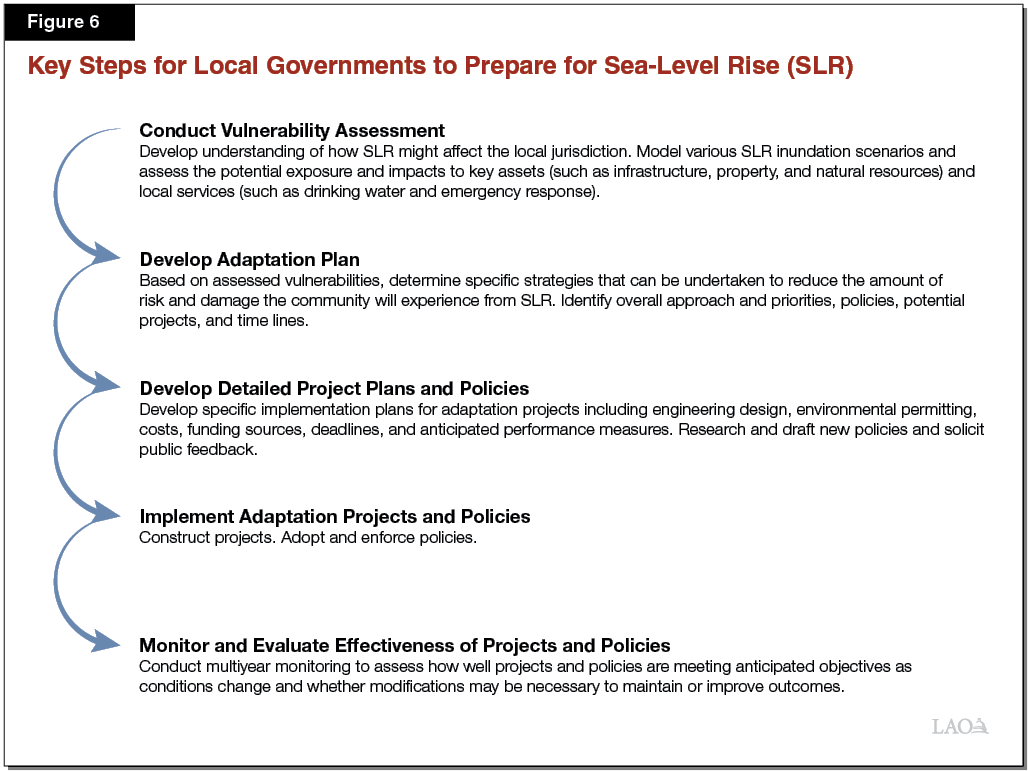

Local Governments Can Undertake Multiple Steps to Prepare for SLR. While the magnitude and timing of SLR still are unknown, many of California’s coastal communities have begun preparing for what level of risk they face and how they might respond over the coming decades. Figure 6 highlights the key steps in this process. As shown, the first step for local governments typically is to conduct an assessment to ascertain how their residents, infrastructure, and services might be affected under different SLR scenarios. Next, they develop a high‑level adaptation plan for how they might address those identified vulnerabilities. Subsequently, they begin to undertake the three stages of actually applying adaptation strategies to mitigate those risks—developing detailed plans, constructing projects, and undertaking ongoing monitoring and modifications to ensure effectiveness. While in many cases communities may undertake adaptation projects—such as building up sand dunes or restoring wetlands to serve as a wave buffer, or relocating infrastructure out of flood zones—they also may implement new policies as part of their adaptation strategies. These could include imposing limits on (1) where and when hard armoring may be used (in order to prevent the erosion of beaches), (2) new development, or (3) rebuilding in certain coastal areas.

The process described in Figure 6 represents a deliberate, strategic approach to undertaking coastal adaptation. However, state law does not require that local governments progress sequentially through the steps described in the figure—nor, indeed, that they undertake each step at all. (As noted earlier, Coastal Commission staff does encourage local governments that are updating their Local Coastal Programs [LCPs] to undertake SLR vulnerability assessments.) Local governments could opt to skip the first several proactive planning steps of this process and instead implement response activities on a reactive basis once they begin to experience SLR impacts. As we discuss later, however, to the degree local communities avoid undertaking proactive risk assessment and planning activities in the near term, they may lose some opportunities for minimizing damage and disruptive SLR impacts in future years.

Many Coastal Communities Have Begun Preparing for SLR, but Only in Early Stages. Data suggest that many communities around the state have begun to prepare for the effects of climate change. For example, OPR’s statewide Annual Planning Survey found in 2018 that 60 percent of responding cities and counties have plans or strategies to adapt to the impacts of climate change. (This survey did not ask about SLR specifically.) However, a closer look at the status of adaptation planning around the state suggests that even for those jurisdictions that are beginning to address the impacts of climate change, the majority of coastal jurisdictions still are only in the initial stages of the SLR preparation process displayed in Figure 6. Specifically, a recent statewide survey called the 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey—conducted as part of California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment—asked coastal professionals about the current status of their adaptation work. Respondents included representatives from the local, state, and federal levels of government, as well as private consultants and nongovernmental organizations. About one‑third of respondents indicated they were primarily engaged in detecting and gathering information—such as by conducting vulnerability assessments. About half of respondents said they were developing adaptation and project plans—the second and third steps of the adaptation process shown in Figure 6. Only 16 percent indicated that they had transitioned to implementing and monitoring projects and policies. While these responses show slight progress compared to a similar survey conducted in 2011—in which a larger share reported they were still assessing their climate risks—the results show that few communities are yet ready to begin implementing SLR adaptation projects.

Moreover, the fact that most of the survey respondents indicated that they are engaged in some phase of adaptation work is not representative of the whole state, as highlighted by the OPR survey data. That is, this survey’s responses seemingly over‑represented coastal professionals who are engaging in adaptation work and under‑represented those communities that have not yet begun this type of work. That even within this skewed sample group so few respondents indicated they are implementing projects underlines how much preparation work remains to be undertaken statewide.

Several Types of SLR Planning Efforts Underway at Local Level. While some local governments are undertaking SLR vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans on their own initiative, such efforts are also prompted by three key statutory requirements. First, as described in the nearby box, the 1976 California Coastal Act encouraged coastal communities to develop LCPs, which include policies to govern new and existing development along the coast and protect coastal resources in accordance with state law. Since most LCPs were developed around 30 years ago—before the need to account for the potential effects of climate change—some coastal communities are beginning to work on updates to address SLR. The Coastal Commission reports that 39 jurisdictions are in the process of updating their LCPs for SLR, including 30 that have completed vulnerability assessments. (Coastal Commission staff encourages using SLR vulnerability assessments to inform LCP updates.) Thus far, only three local governments have completed all stages of updating their LCPs for SLR and had them certified by the Coastal Commission. As shown earlier in Figure 5, state funding grants have partially supported these efforts. Specifically, the Coastal Commission reports that between 2013 and September 2019, it provided 50 grants totaling nearly $7 million to 37 local jurisdictions for SLR‑related LCP updates.

State Has Special Jurisdiction Over Land Use Decisions in the Coastal Zone

Enacted in 1976, the California Coastal Act gives the state a unique role in planning and regulating the use of land and water along the coast. Specifically, within the coastal zone—unlike other areas of California—the state possesses the authority to regulate the construction of buildings, divisions of land, and activities that change the intensity of use of land or public access to coastal waters. (The land covered by the coastal zone is specifically delineated in statute and varies in width from several hundred feet in highly urbanized areas up to five miles in certain rural areas, and excludes the San Francisco Bay Area.) The basic goals of the Coastal Act are to balance development along the coast with protecting the environment and public access. The Act includes specific policies that address issues such as shoreline public access and recreation, habitat protection, landform alteration, industrial uses, water quality, transportation, development design, ports, and public works. The Coastal Act tasks the California Coastal Commission with implementing these laws and protecting coastal resources. As such, entities seeking to undertake development activities within the coastal zone must first attain a coastal development permit from the Coastal Commission. (In general, local governments make decisions about land use outside the coastal zone.)

The Coastal Commission may delegate some permitting authority to the 76 cities and counties along the coast if they develop plans—known as Local Coastal Programs (LCPs)—to guide development in the coastal zone. The LCPs specify the appropriate location, type, and scale of new or changed uses of land and water, as well as measures to implement land use policies (such as zoning ordinances). The Coastal Commission reviews and approves (“certifies”) these plans to ensure they protect coastal resources in ways that are consistent with the goals and policies of the Coastal Act. Local governments have incentives to complete certified LCPs, as they can then handle development decisions themselves (although stakeholders can appeal such decisions to the Coastal Commission). In contrast, any project undertaken in the coastal zone in communities without certified LCPs must attain a permit from the Coastal Commission. To date, nearly 90 percent of the applicable geographic area is covered by a certified LCP.

Second, Chapter 608 of 2015 (SB 379, Jackson) requires communities to update the safety element of their General Plans to address the risks posed by climate change no later than 2022. Data suggest that local jurisdictions still are in the process of working to meet this requirement. Specifically, about 30 percent of the cities and counties that responded to OPR’s 2018 survey reported that they have addressed climate adaptation in their adopted General Plan policies.

Third, Chapter 592 of 2013 (AB 691, Muratsuchi) required certain coastal cities and special districts to conduct an assessment of how they propose to address SLR on the granted public trust coastal lands for which they are responsible. (These are sovereign state lands for which the Legislature has delegated management to local municipalities for specified uses, such as piers, ports, harbors, airports, and recreation.) For each applicable jurisdiction, these assessments must include: (1) an inventory of public trust assets that are vulnerable to SLR; (2) how SLR may impact those assets in the short, medium, and long term; (3) an evaluation of the financial costs associated with those SLR impacts—including for nonmarket asset values such as recreation and ecosystem services; and (4) a description of how potential SLR adaptation strategies could address the identified vulnerabilities and a proposed time frame for implementing such measures. The State Lands Commission is in the process of reviewing these reports, which had to be submitted by July 2019.

Some Examples of Regional Collaboration on SLR Planning Exist, but Efforts Are Limited. Because the effects of SLR do not stop at the city border or county line, local jurisdictions would benefit from working together with their neighbors on a regional basis to collaborate on plans for addressing the interrelated impacts. While some regional collaborative efforts have been initiated across the state, these initiatives still are emerging and uneven. Perhaps the largest effort consists of seven regional groups that have formed in various areas of the state to work on climate change adaptation issues—including but not limited to SLR—as highlighted in Figure 7. The Local Government Commission and OPR help facilitate a network for these groups to communicate, known as the Alliance of Regional Collaboratives for Climate Adaptation (ARCCA). However, these regional groups have experienced varying levels of participation and activity. Most of the groups meet only intermittently to informally share information, none has worked on developing a regional SLR or climate adaptation plan, and typically, they do not have permanent dedicated funding or staff. In some cases, local jurisdictions are only eligible to participate in their region’s collaborative if they are willing and able to pay an annual administrative fee. As such, not all cities and counties located within the regions encompassed by these ARCCA groups are active participants that benefit from the potential collaboration. (Orange County is the only coastal county not encompassed by any of the ARRCA regional collaboratives.)

Figure 7

Groups Participating in the Alliance of Regional Collaboratives for

Climate Adaptation

|

The SF Bay Area has made the most progress on multicounty regional SLR collaborative efforts. In a survey of SF Bay Area stakeholders conducted by University of California (UC), Davis, researchers in the fall of 2018, close to 60 percent of respondents reported that they had shared information about SLR with other organizations in the last year, and about 45 percent said that they had engaged in some joint SLR planning with other organizations. Moreover, in 2016, voters in the nine‑county region passed Measure AA, establishing the SF Bay Restoration Authority and imposing a parcel tax that is projected to raise about $25 million annually for 20 years to fund projects to protect and restore the bay. To support this effort, the Authority has established—and funded—the “SF Bay Restoration Regulatory Integration Team,” which is intended to expedite and simplify the permitting process for wetland restoration and flood management projects. Additionally, BCDC is initiating efforts to coordinate the development of a “Regional Adaptation Plan” for the SF Bay Area.

Other limited examples of regional collaboration related to SLR exist around the state at the county level. For example, some counties have conducted vulnerability assessments and adaptation planning specifically to address the threat of SLR across the jurisdictions within their counties. These include Marin and San Mateo. San Mateo County also just received statutory approval to reconstitute an existing special flood district to specifically address the anticipated impacts of SLR across the county. Additionally, San Diego County undertook a three‑year initiative (funded by grants from NOAA and SCC) called the “Resilient Coastlines Project of Greater San Diego” to coordinate several local SLR initiatives, gather scientific information on a regional basis, develop tools and resources, and connect community members and scientific experts to work together.

In an effort to help encourage regional climate adaptation efforts, the Legislature recently passed Chapter 377 of 2018 (SB 1072, Leyva). This legislation creates a program to assist under‑resourced communities in developing the capacity to access grant funding for climate change mitigation and adaptation projects. SGC will administer the program, and still is in the process of determining its structure, selection criteria, and funding sources.

Strong Case Exists for Local Governments to Accelerate Adaptation Activities

The relatively limited progress that local governments have made in preparing for SLR may not seem overly concerning, given that most of the intense impacts of SLR still are decades in the future. However, waiting too long to initiate adaptation efforts likely will make executing an effective response more difficult and costly. Taking action ahead of when sea levels are projected to significantly encroach on the coast would enable local governments to benefit in several important ways, as summarized in Figure 8 and discussed below.

Figure 8

Benefits of Taking Action Early to Prepare for Sea-Level Rise (SLR)

|

Planning Ahead Means Adaptation Actions Can Be Strategic and Phased. Time allows cities and counties to (1) be strategic, phased, and thoughtful about which approaches will work best for their communities; (2) gather community input; and (3) implement projects and policies that may take many years to put into effect. Planning ahead can allow coastal communities to adopt a phased approach for when it will undertake escalating actions that is dependent upon when certain predetermined conditions or “triggers” are reached. For example, such a strategy might state that the community will relocate its wastewater treatment plant once sea levels are observed to have risen by 1 foot locally, and that in the meantime, stakeholders will identify a new location for the plant, develop detailed project plans, and acquire funding so they are ready to implement the project once the identified threshold has been reached. A phased approach based on defined triggers can also help address community concerns that a local government might be acting “prematurely” to address SLR and thereby affecting their property values unnecessarily. The State of California Sea‑Level Rise Guidance Document encourages coastal communities to utilize “adaptation pathways” with multiyear, progressive steps—but such an approach requires time to develop and implement.

Undertaking Certain Near‑Term Actions Can “Buy Time” Before More Intensive Responses Are Needed. Putting certain adaptation projects and strategies in place now can help postpone and extend the period before which subsequent, more difficult‑to‑implement actions are needed. For example, building up wetlands or sand dunes in certain areas could help buffer the effects of SLR and coastal storms and protect the development behind them for the coming few decades. Even if such a strategy would have decreasing effectiveness once sea levels rise to higher levels, implementing such a project in the near term could delay the date at which the buildings begin to regularly flood and need to be relocated or elevated.

Early Implementation Provides Opportunity to Test Approaches and Learn What Works Best. Near‑term action allows for time to test theories and determine the most effective approaches. Because SLR poses a unique set of challenges, many uncertainties exist around which potential adaptation strategies might be most effective. For example, scientists are unsure of how successful wetland restoration projects will be at buffering the force of waves during more severe coastal storms. Acting to implement adaptation strategies in the near term will provide the opportunity to monitor, evaluate, and revise them in the coming years. This can help the state and local governments ascertain which types of approaches will be best for particular locations and/or for widespread application as SLR threats become more pressing.

Taking Action Earlier May Make Overall Adaptation Efforts More Affordable. Undertaking a multiyear, multistep strategic plan for coastal adaptation can allow local governments to spread costs over a longer period of time and thereby make them more affordable. A multiyear financing approach—such as utilizing bonds—for large projects also provides the opportunity for costs to be borne by both current and future taxpayers, which is reasonable since such projects are intended to provide benefits over many years. Moreover, if local governments take the opportunity to test out SLR response approaches, they and other coastal communities can learn “best practices” from those pilot projects and likely will be able to replicate similar approaches in more efficient, cost‑effective ways in the future.

Coming Decade Represents Key Window for SLR Preparation. Experts suggest the next ten or so years represent a crucial time period for taking action to prepare for SLR. After that point, sea levels may already have risen by around 1 foot in many locations, as shown earlier in Figure 1. Once sea levels have risen to higher levels, the planning window narrows and options for how local governments can respond become more limited. For example, a comprehensive scientific study of the SF Bay, The Baylands and Climate Change, suggests tidal marshes that are established by 2030 are more likely to flourish and provide wave‑buffering benefits. After that point, marshes may not have sufficient time to develop and fortify—by building up sediment and growing plants—and will instead become submerged. Coastal communities that delay SLR response activities until coastal flooding is more imminent lose opportunities to implement proactive, incremental, and ground‑tested adaptation responses. Instead, they will be forced into a more reactive mode with the need to address the threat immediately.

Local Adaptation Efforts Face Key Challenges

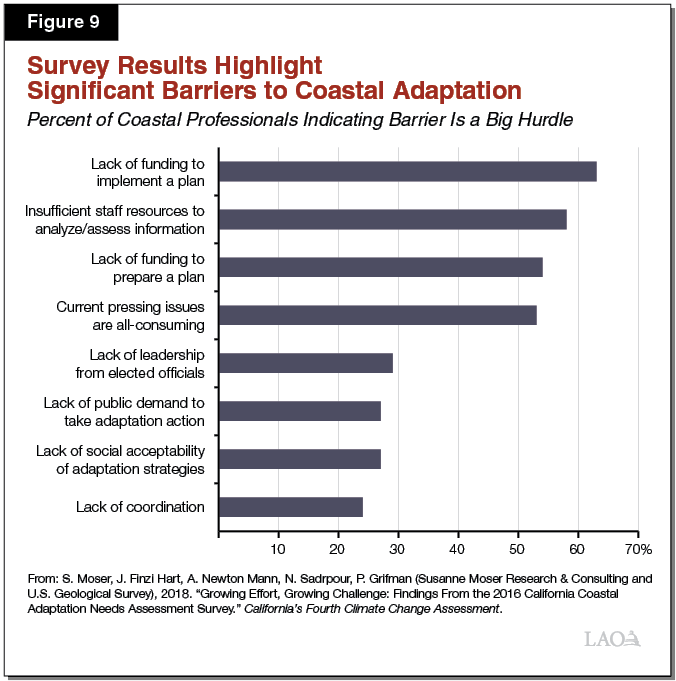

Despite the significant threats posed by the projected changes in the coming years and the compelling reasons to take action soon, most local governments still are only in the early stages of preparing for SLR, as discussed earlier. Data suggest that local governments’ progress in adapting to the impacts of SLR is constrained by a number of key challenges. For example, Figure 9 displays the top eight barriers that coastal professionals identified in the 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey as being “big hurdles” in their adaptation efforts. The academic literature on coastal adaptation and the many interviews we conducted in researching this report identified some additional common obstacles. Figure 10 summarizes our compilation of key challenges, which we describe in more detail in this section.

Figure 10

Local Adaptation Efforts Face Key Challenges

|

Funding Constraints Hinder Both Planning and Projects

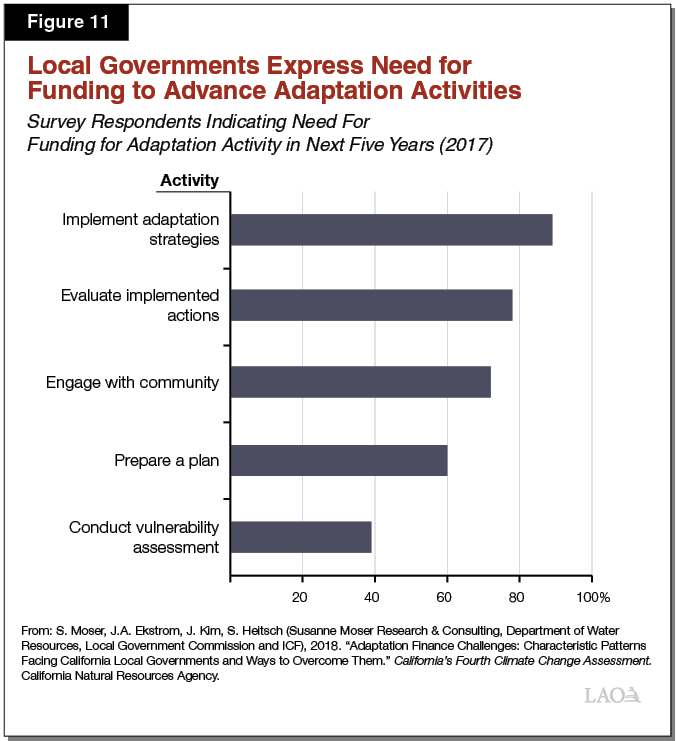

Local Governments Cite Funding Limitations as Primary Barrier to Making Progress on Coastal Adaptation Efforts. Funding for both coastal adaptation project implementation and planning are paramount concerns for local governments seeking to prepare for SLR. These funding challenges were identified in nearly all of the interviews we conducted in researching this report, and also are reflected as the first and third most cited hurdles, respectively, in the survey data displayed in Figure 9. A different statewide survey conducted in 2017 asked local government representatives specifically which adaptation‑related activities they needed funding to conduct over the coming five years. (This survey did not ask about SLR or coastal adaptation specifically.) The responses are displayed in Figure 11 . As shown, comparatively lower—but still significant—proportions of respondents indicate the need for funding to conduct initial assessment and planning activities, with a much higher share needing funding to implement and evaluate projects. That survey also asked local governments whether they had yet acquired the necessary funds to undertake the identified adaptation activities—fewer than 2 percent responded affirmatively. About 32 percent of respondents indicated they had secured some funding, whereas about two‑thirds responded they had secured none of the needed funding.

Responses from our interviewees and both of the above surveys appear to align with the trends cited earlier—that many but not all communities have made headway in beginning to plan for climate change impacts (which is why comparatively fewer cite the need for planning funds), but few have moved into enacting those plans. Moreover, these data suggest that funding is a primary contributor to that lack of progress. The expressed need for funding likely is a result of constraints on available local funding as well as on funding from state, private, or federal sources.

Limited Local Funding Faces Many Competing Priorities. Even though responsibility for addressing SLR lies primarily with local governments, our interviews indicated that they struggle to identify local funding sources they can dedicate to preparation activities. This is echoed by the 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey, with respondents indicating that only about one‑third of the funding currently supporting their adaptation activities comes from local sources. One chief explanation for these responses is that allocating funding from existing sources to respond to a large, long‑term, uncertain threat such as SLR is difficult when local governments have to balance such expenditures against many other immediate short‑term priorities. Such priorities might include housing shortages, homelessness, schools, aging infrastructure, and other climate‑related impacts such as increased wildfires. (Competing funding commitments likely also are factors for the 53 percent of survey respondents shown in Figure 9 who cite the challenge of facing many other pressing, all‑consuming issues as a big hurdle in addressing SLR.) Additionally, California local governments’ ability to generate new revenues for activities is constrained by certain constitutional limitations, including Proposition 13 (1978, which limits increases in local property taxes) and Proposition 218 (1996, which requires meeting a two‑thirds local voter threshold in order to raise certain local taxes and fees). Moreover, local revenues available for adaptation activities may be further constrained in the future by SLR. This is because existing property values in some areas of the coast likely will decrease if those buildings become or are at risk of becoming flooded, thereby over time affecting the property tax revenues generated for the local jurisdiction.

Only Limited Amounts of Adaptation Funding Have Been Available From Other Sources. Local government respondents to the 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey indicated that while local sources have provided one‑third of their coastal adaptation funding thus far, state funds provided the largest share—45 percent. As shown earlier in Figure 5, however, these funds have been relatively modest. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the important role that state resources have played in encouraging the coastal adaptation activities that have occurred to date. Responses to the aforementioned survey indicate that funding they have received for their adaptation activities from other sources are even more limited—10 percent from foundations or other private sources and 9 percent from the federal government.

Limited Local Government Capacity Restricts Ability to Take Action

Local Governments Lack Sufficient Staff and Technical Expertise to Address SLR. Inadequate internal capacity to undertake adaptation planning and projects is also a significant barrier to local governments’ SLR preparation efforts. We heard this frustration expressed repeatedly in our interviews, with local government staff indicating they need to address adaptation planning activities in addition to their primary job responsibilities. Additionally, local government interviewees indicated that staffing constraints often mean that they do not have the capacity to complete the work necessary to compile successful grant applications for the funding that the state offers for adaptation planning and projects—thereby compounding their challenges in making progress on coastal adaptation efforts. In OPR’s 2018 Annual Planning Survey, 60 percent of responding cities and counties indicated they had very little or no staffing and technical capacity to address climate change or adaptation. These findings are mirrored in the survey responses highlighted in Figure 9. Specifically, insufficient staff resources to analyze and assess information was the second most commonly cited hurdle to coastal adaptation efforts, cited by 58 percent of respondents. Interestingly, some progress to address these capacity issues appears to have been made in recent years, as a comparatively higher percentage of coastal professionals responding to the 2011 version of the same coastal needs assessment survey indicated insufficient staff resources as being a big hurdle—67 percent compared to 58 percent in the 2016 survey.

Adaptation Expertise Is Not Widespread. A couple of key factors may explain these capacity challenges. The first is a direct result of the funding constraints noted earlier—limited funds often translate to a limited ability to hire a sufficient cadre of qualified staff. Additionally, because climate adaptation is a new field, local governments find it hard to locate individuals with appropriate scientific, engineering, and legal experience and expertise to know how to plan for the impacts of SLR, even if they could manage to secure the funds to hire more staff. The 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey report states that “most coastal practitioners are still essentially learning about adaptation ‘on the job’ rather than through formal training opportunities.” Specifically, the survey found that only about 40 percent of local government respondents indicated that they had received any formal training in adaptation.

Small and Disadvantaged Communities Particularly Challenged by Capacity Limitations. Our research indicates the challenges associated with limited government capacity to address climate adaptation needs are especially pronounced for smaller communities and those whose residents have a lower average income and/or lower property values. These communities often have smaller government administrations and fewer financial, business, philanthropic, and community resources upon which to draw. As such, these communities likely find it even harder than their larger and better‑resourced neighbors to hire and maintain experienced staff dedicated to adaptation work—which in turn also makes it even more challenging to compete for limited grant funding. This raises an important social equity concern about how adequate preparation for SLR may be influenced by the relative size and wealth of a particular community.

Adaptation Activities Constrained by Lack of Key Information

Local Governments Cite a Need for Additional Data to Help Inform Adaptation Decisions. In the interviews we conducted in preparing this report, one of the most frequently cited obstacles to coastal adaptation was a lack of information to help guide decision‑making. Specifically, local entities expressed uncertainty about how to proceed with SLR preparation because they are unsure about details such as:

- Trade‑Offs of Adaptation Options. Data and examples that might help inform which adaptation options might be most appropriate for their community and what factors to consider when making those decisions.

- Cost of Adaptation Options. Rough estimates for how much different options might cost to implement and what factors influence those costs.

- Economic Implications of Adaptation Options and SLR Impacts. The potential economic impacts of implementing various adaptation options, including the “no action” alternative.

- Locally Specific SLR Projections. Specialized estimates and maps for how exactly SLR and coastal storms might affect specific locations, neighborhoods, infrastructure, and resources in their communities.

- Legal Clarifications. A legal analysis clarifying the responsibilities—and liabilities—local governments face with regard to SLR, particularly related to how potential changes in the mean high‑tide line, land use policies, and city services might affect private properties.

The first four information priorities were also cited by city and county respondents to the 2016 California Coastal Adaptation Needs Assessment Survey when asked which types of information they perceive as most useful for assessing the risks from climate change to local coastal resources. Specifically, about 75 percent rated information on the trade‑offs of adaptation as very useful, and a similar percentage said the same about information on the costs of adaptation (representing the top two responses to the question). The usefulness of economic and community vulnerability assessments each were rated as very useful by about 60 percent of respondents. (The survey did not ask about legal information.)

The lack of information on the potential economic impacts that SLR might have on the community was raised repeatedly throughout the interviews we conducted for this report. Even for the local governments that have conducted initial SLR planning activities, few vulnerability assessments include these types of considerations. Similarly, only a handful of completed adaptation plans across the state include an analysis of the economic trade‑offs of employing potential adaptation strategies. For example, this could include evaluating and comparing the short‑ and long‑term costs and benefits of approaches like building seawalls, adding sand to beaches, restoring wetlands, and relocating infrastructure. Feedback from our interviewees suggests they have not undertaken these types of analyses because they are complicated and expensive to conduct, with few examples available to serve as models. Yet without an understanding of the economic implications associated with SLR or the costs and benefits of the steps they could take to address those impacts, local governments are constrained in determining the best path forward.

Novelty of Coastal Adaptation Efforts Means Information Is Even More in Demand—and Limited. Interviewees who were able to gather the necessary information to complete vulnerability assessments and high‑level adaptation plans indicated that they were unclear how to determine what specifically they should do next. That the coastal adaptation field is so new is a large contributor to this information gap. These uncharted waters present a double challenge—local governments have never undertaken such work before and therefore are urgently in need of guidance, examples, and data to help them make these novel decisions. However, such information is not widely available because few others have undertaken such work either.

Technical Assistance Not Widely Available. Interviewees cited a lack of—and desire for—entities to which they might be able to turn for advice, technical assistance, comparison data, and real‑world examples to help inform their adaptation decisions. As noted earlier, OPR created the Adaptation Clearinghouse, which provides an online database of resources for adaptation planning and projects. Our interviews and available research, however, suggest use of this website is not yet widespread. This is due both to a lack of awareness about the resource, and also because users find it overwhelming and difficult to navigate. Rather, local entities express a desire for (1) models and planning templates they can recreate or modify to meet their local circumstances, and (2) experts they can call upon to discuss and help address their specific needs. The Clearinghouse has only limited examples that meet the first need and does not have staff available to address the second. Some entities have provided technical assistance for coastal adaptation efforts within their regions—such as the Adapting to Rising Tides Program administered by BCDC in the SF Bay Area and the University of Southern California Sea Grant program in Los Angeles—but these resources are not available statewide.

Few Forums for Shared Planning and Decision‑Making Impede Cross‑Jurisdictional Collaboration

Local Governments Lack Robust Forums for Discussing and Planning for SLR on a Regional Basis. Local governments across California lack formal and strategic ways to learn from each other, share information, or make decisions together about coastal adaptation issues. As noted earlier, while some regional collaborative efforts are underway across the state, such initiatives are largely informal, they lack funding and staff, and their level of activity and participation vary by region. Moreover, with the exception of a couple of countywide plans, no region has yet developed a coordinated plan for how it will address SLR impacts on a regional basis. This lack of coordination was frequently mentioned as a significant concern by the individuals we interviewed, and was highlighted as a big hurdle by about one‑quarter of survey respondents in Figure 9. When UC Davis researchers surveyed stakeholders in the SF Bay Area about the largest barriers they face in working collaboratively with other stakeholders on SLR issues, the most common response was the lack of an overarching regional plan to address SLR.