LAO Contacts

January 6, 2020

Potential Impacts of Recent State Asset Forfeiture Changes

- Introduction

- Overview of Asset Forfeiture

- SB 443 Made Changes to Asset Forfeiture

- Difficult to Determine Economic Impact of SB 443 Changes

- Data Related to Potential Impacts of SB 443

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Overview of Asset Forfeiture. Asset forfeiture refers to the seizure of cash or other items suspected of being tied to crime and the transfer of these items to government ownership. The asset forfeiture process generally involves three steps: (1) seizure of items; (2) adjudication proceedings—held at the federal or state level—to determine whether seizures were appropriate; and (3) distribution of proceeds to various agencies, typically for support of law enforcement activities. Federal and state laws as well as local policies apply to each step, meaning processes differ across the nation and within California.

SB 443 Changed Asset Forfeiture and Required Data on Economic Impact. Chapter 831 of 2016 (SB 443, Mitchell) made various changes to the state’s asset forfeiture processes related to drugs. Specifically, it limited law enforcement’s ability to pursue certain types of asset forfeiture cases at the federal level and required criminal conviction for receipt of proceeds from certain cases pursued at the federal level. It also made changes to California’s asset forfeiture processes by requiring criminal convictions and increasing the burden of proof required for certain seizures. Finally, SB 443 requires our office to provide data to the Legislature about the economic impact of these changes on law enforcement budgets. This report responds to this requirement.

Data Used for This Report. For this report, we analyzed asset forfeiture data submitted to the California Department of Justice (CA DOJ) as well as various other federal, state, and local data. However, we identified a number of challenges that make it difficult to determine the economic impact of SB 443. For example, the data reflect the impacts of various asset forfeiture‑related changes at both the federal and state level. Additionally, the CA DOJ asset forfeiture data is incomplete and limited. This is compounded by challenges with the various other data sources used to supplement the CA DOJ data.

Potential Reduction in Asset Forfeiture Distributions, but by Unknown Amount. Despite such challenges, certain trends and patterns can be observed in the data. Specifically, we identified the following trends:

- California generally receives more than $100 million annually in asset forfeiture distributions.

- State and federal asset forfeiture distributions have fluctuated in recent years.

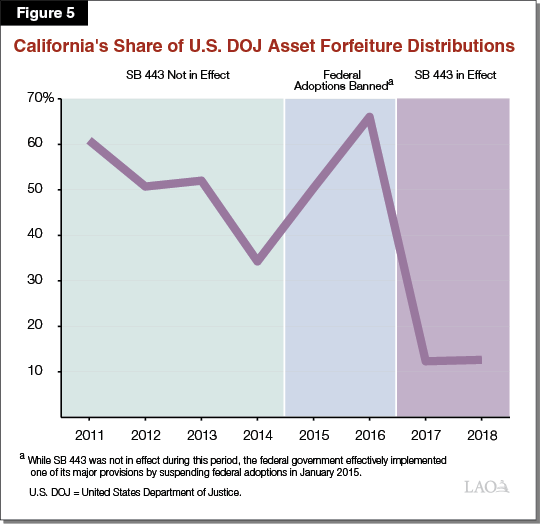

- California’s share of United States Department of Justice asset forfeiture distributions has significantly declined since 2017.

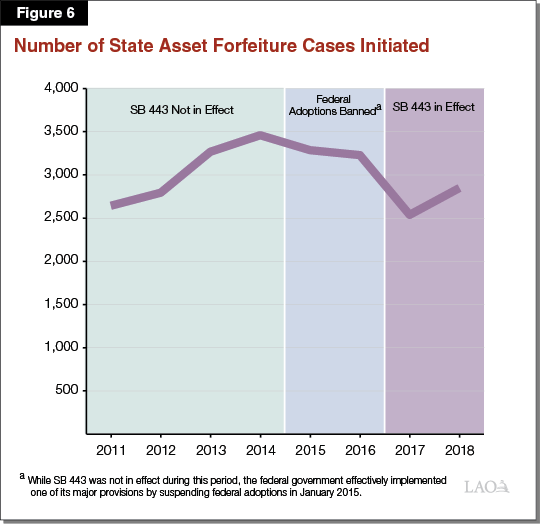

- The number of cases initiated and adjudicated at the state level generally declined.

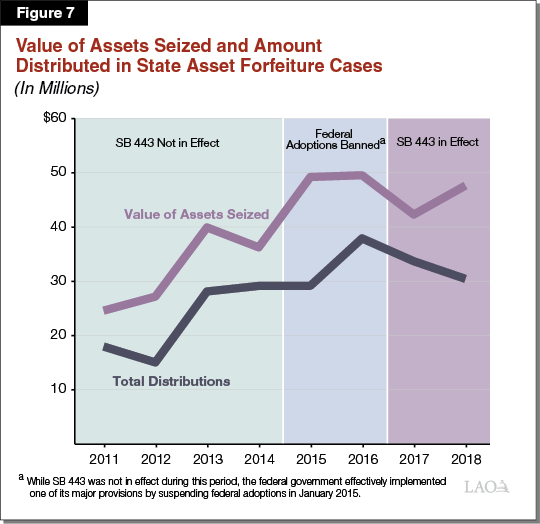

- The value of assets seized and amount distributed in state cases increased until 2016.

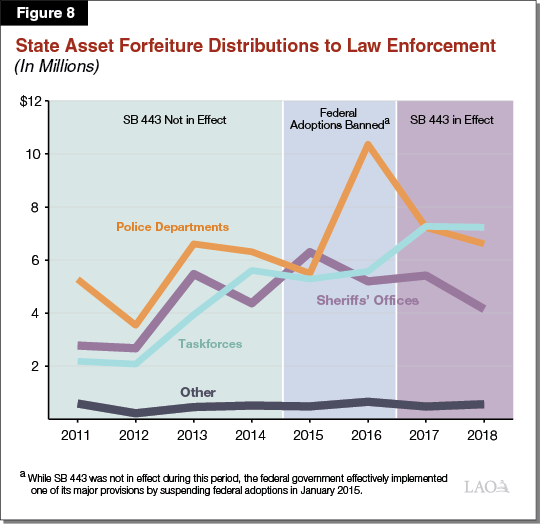

- Distributions to most agencies generally declined until 2018.

- Distributions generally reflect a small share of agency budgets.

While not solely attributable to SB 443, data suggest that it potentially reduced distributions received by California. However, it is not possible to estimate the size of this potential impact because of the challenges discussed above. As such, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the data. Additionally, law enforcement is still adapting to SB 443 as well as to various changes in the federal asset forfeiture process. Accordingly, future data could provide a more accurate—and potentially different—picture of the impact of SB 443.

Introduction

Chapter 831 of 2016 (SB 443, Mitchell) made various changes to the state’s asset forfeiture processes related to drugs. These changes generally make it more challenging for state and local law enforcement agencies to pursue certain asset forfeiture cases. Senate Bill 443 also requires our office to provide a report that contains data about the economic impact of these changes on state and local law enforcement budgets. This report responds to that requirement. In preparing this report, we analyzed available federal, state, and local data sources, as well as consulted with various stakeholders (such as local law enforcement agencies).

Overview of Asset Forfeiture

What is Asset Forfeiture?

Seizure and Transfer of Certain Items to the Government. Asset forfeiture refers to (1) the seizure of cash, property, or other items that are suspected of being tied to a criminal offense and (2) the transfer of ownership of these items to the government. The proceeds from these seizures are generally used to support various state and local law enforcement activities.

Seeks to Disrupt Criminal Activity, While Ensuring Due Process. According to federal and state laws, one of the primary goals of asset forfeiture is to punish, disrupt, and deter criminal activity by seizing items used to facilitate the activity or acquired through it. However, another primary goal of federal and state laws is to ensure due process to uphold individuals’ rights. To accomplish this, state and federal laws include different safe guards intended to prevent abuse. For example, under both federal and state laws, any proceeds from asset forfeiture distributed to law enforcement agencies are generally only available to supplement (not supplant) law enforcement budgets.

How Does the Asset Forfeiture Process Work?

The asset forfeiture process generally involves three steps: (1) seizure, (2) adjudication, and (3) distribution. Federal and individual state laws apply to each step of the process. For example, federal and state laws define the conditions and processes governing asset forfeiture for specific items, for determining whether specific seized items can be kept, and for using forfeited items. Local policies often provide further details in each of these areas. This results in asset forfeiture processes differing across the nation and within California.

Seizure

Federal law, individual state laws, and local policies dictate the conditions under which law enforcement may seize assets as well as the specific processes and procedures that they must follow when seizures occur.

Seizures Conducted by Law Enforcement. Federal and individual state laws authorize law enforcement agencies to conduct asset forfeiture seizures. These laws also can specify the conditions under which prosecutorial agencies must also be involved. For example, in California cases, prosecutors are generally required to initiate drug‑related asset forfeiture seizures.

Seizure Typically Tied to Suspicion That Criminal Offense Occurred. Federal and individual state laws authorize asset forfeiture for certain types of criminal offenses, such as drug‑related offenses. For example, California law authorizes asset forfeiture of items related to individuals suspected of selling certain types of drugs (such as cocaine or heroin). Seizure is also authorized under specified circumstances, such as if the seizure is related to a search warrant or if there is probable cause to believe that the item was used to violate state drug laws. As such, law enforcement officers must have at least probable cause to believe that an eligible drug‑related crime has occurred before assets may be seized. (Probable cause is the lowest burden of proof, and is the level that must be met for officers to make arrests.)

Seizure of Items Must Have Statutorily Authorized Justification. Federal and individual state laws authorize the seizure of cash, property, and other items only under certain justifications. In practice, these justifications are also known as theories. The most common theories include:

- Contraband theory allows the forfeiture of items deemed illegal under federal or state laws (such as illegal drugs).

- Exchange theory allows the forfeiture of items intended to be exchanged for illegal items (such as cash exchanged for illegal drugs).

- Proceeds theory allows the forfeiture of items that can be traced back to a benefit that resulted from an illegal exchange. For example, items purchased legally using money deposited into a bank from the sale of illegal drugs would be eligible for forfeiture.

- Facilitation theory allows the forfeiture of items intended to be used to make it easier to commit a criminal offense (such as a vehicle).

Additional Federal and State Limits Apply. Even if items are potentially eligible for seizure under one of the statutorily authorized theories, federal and state laws and local policies can include additional limitations on seizures. For example, federal policies generally authorize the civil forfeiture of cash only if at least $5,000 is seized. In California, for drug‑related asset forfeiture, state law prohibits the seizure of real property if it is being used as a family residence or for other lawful purposes.

Adjudication

After seizure occurs, asset forfeiture proceedings are initiated to determine whether the assets were seized appropriately and can be kept for subsequent distribution. As we discuss below, these proceedings can be held at the federal or state level.

Asset Forfeiture Cases Can Be Adjudicated Through Either Federal or State Proceedings. State and local law enforcement agencies and/or prosecutors can sometimes choose whether to pursue an asset forfeiture case through federal or state proceedings. Federal asset forfeiture proceedings are pursued through either the United States Department of Justice (U.S. DOJ) or the United States Department of Treasury Asset Forfeiture Programs. A variety of factors influence this choice, such as differences in how proceeds from state versus federal proceedings are distributed and how such distributions can be used.

Cases are generally pursued through federal proceedings in one of the following two ways:

- Joint Investigations. Asset forfeiture cases that arise from joint investigations between federal and state and/or local law enforcement can be pursued at the federal level. These joint investigations usually take place through taskforces. Taskforces generally involve agencies agreeing to provide a certain number of staff for a specified purpose (such as illegal drug investigations). While participating agencies typically pay for certain costs (such as their officers’ salaries), the taskforce typically pays for other costs (such as officers’ overtime) using asset forfeiture proceeds or other funds. Participating agencies generally sign agreements documenting their responsibilities and their share of any monies (such as asset forfeiture proceeds) received by the taskforce.

- Adoptions. In cases not involving federal law enforcement, state or local jurisdictions can request the federal government “adopt” the asset forfeiture case. Adoption generally requires that federal law (1) similarly deems the alleged criminal offense a crime and (2) authorizes the theory of forfeiture used to justify the seizure. (As we discuss below, federal adoptions are no longer allowed in California.)

Cases that are not pursued through federal proceedings are instead pursued through state proceedings. These include cases that state or local jurisdictions choose to not have adopted or are not eligible for adoption, as well as cases that joint investigations choose to pursue through state (rather than federal) proceedings.

Individuals Allowed to Contest Seizures in Proceedings. Federal and individual state laws specify processes by which individuals can challenge seizures. Individuals can contest seizures for various reasons. For example, individuals can claim that the seizure was inappropriate (such as not complying with statutorily mandated procedures). Individuals can also claim that they had no knowledge of the suspected criminal activity (such as an individual unknowingly loaning a vehicle to another person who uses it for illegal purposes). Whether a seizure is contested typically determines how asset forfeiture proceedings must be adjudicated.

Two Ways to Adjudicate Proceedings at Both Federal and State Level. Proceedings generally either end with an official order to (1) forfeit the items (allowing them to be kept and distributed) or (2) return the items to a specified party. Asset forfeiture at both the federal and state level can occur through one of the following types of proceedings:

- Administrative Proceedings. Administrative proceedings generally allow prosecutors or law enforcement agencies to issue an order to forfeit seized items without court involvement under certain conditions. These proceedings are generally authorized in cases involving specific items that fall below a certain value threshold or where no one files a claim contesting the forfeiture. For example, in California, district attorneys are authorized to order forfeiture of seizures totaling less than $25,000 if appropriate notice is provided and no claim contesting the forfeiture is filed within 30 days.

- Judicial Proceedings. Federal and state laws require judicial proceedings under certain circumstances—such as for certain types of asset forfeiture, items that exceed specific thresholds, or items that an individual contests. For example, in California for drug‑related asset forfeiture, judicial proceedings are required when an individual files a claim contesting the seizure of cash or property. Judicial proceedings can occur through criminal or civil proceedings. The burden of proof in criminal proceedings is generally much higher than in civil proceedings as all criminal convictions require proof “beyond a reasonable doubt”—the highest burden of proof. While proof beyond a reasonable doubt is required for certain seized items in civil proceeding (such as vehicles and homes) in California, a lower burden of proof—known as “clear and convincing evidence”—is required for other items (such as cash above a certain threshold). An even lower burden of proof—known as “preponderance of the evidence”—generally must be met in federal civil proceedings. In California, verified claims contesting forfeiture in either criminal or civil proceedings are generally heard by a jury.

Distribution

Federal and individual state laws generally dictate how asset forfeiture proceeds will be distributed. (Noncash items in asset forfeiture proceedings may be sold, destroyed, or kept for official law enforcement use.) Individual state and local laws also dictate the conditions under which law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies can receive distributions from the federal government.

Distributions From Federal Proceedings Generally Based on Agency Workload. Federal law allows for the deduction of certain costs (such as victim compensation costs) prior to the distribution of any remaining proceeds—also known as net proceeds—to state and local agencies who worked on the case. Currently, the amount of distribution each agency receives is generally based on the level of resources or work it invested. However, the federal government generally abides by agreements signed by agencies participating in taskforces that specify distribution percentages.

Distributions From State Proceedings Depends on Criminal Offense Type. Individual state laws can also allow for the deduction of certain expenses prior to distribution of the net proceeds. Distribution of remaining proceeds depends on the type of criminal offense. In California, drug‑related asset forfeitures (the subject of SB 443), are subject to the following distributions:

- 1 percent of net proceeds to a nonprofit organization of local prosecutors for training on asset forfeiture ($303,000 in 2018).

- 10 percent to the prosecutorial agency that processed the forfeiture (about $3.3 million in 2018).

- 24 percent to the state General Fund (about $7.3 million in 2018).

- 65 percent to law enforcement entities that participated in the seizure generally based on their proportionate contribution or distribution percentages in signed task force agreements (about $19.6 million in 2018). 15 percent is to be set aside for funding programs to combat drug abuse and divert gang activity.

Use of Funding Limited. Federal and individual state laws generally dictate how asset forfeiture proceeds can be used. For example, both federal and California laws prohibit these proceeds from being used to supplant any existing law enforcement funding. Examples of allowable uses include law enforcement equipment and training. Federal law includes additional restrictions, such as prohibiting transfers of monies to other law enforcement agencies.

SB 443 Made Changes to Asset Forfeiture

Senate Bill 443, which became effective in January 2017, made several changes to the state’s asset forfeiture processes related to drugs. In particular, it made changes to California’s forfeiture processes and their interaction with the federal asset forfeiture processes. We discuss below the major changes.

Changes to California’s Interaction With Federal Asset Forfeiture Processes

Prohibits Federal Adoptions. Senate Bill 443 prohibits state and local law enforcement agencies from requesting that the federal government adopt cases in which federal law enforcement has no involvement. (We note that the federal government temporarily suspended adoptions from January 2015 through July 2017—about six months after the implementation of SB 443.) However, SB 443 did not change the ability for state and local law enforcement agencies to participate in joint investigations.

Requires Criminal Conviction for Receipt of Proceeds From Federal Proceedings. Senate Bill 443 prohibits state and local law enforcement agencies participating in federal joint investigations from receiving distributions from seizures under $40,000 unless there is a conviction in federal court for a criminal offense for which property is subject to forfeiture under state law. A criminal conviction, however, is not required for cases in which the forfeited property is cash or negotiable instruments of $40,000 or more.

Changes to California’s Asset Forfeiture Processes

Increases Burden of Proof Required for Seizures Between $25,000 and $40,000. Prior to the implementation of SB 443, prosecutors were required to demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that the forfeiture of certain items—including vehicles, homes, and cash or negotiable instruments up to $25,000—met state requirements for their seizure (such as being justified under an authorized forfeiture theory). Clear and convincing evidence (a lower burden of proof) was required for cash and negotiable instruments above $25,000. Senate Bill 443 increases the burden of proof required for cash and negotiable instruments between $25,000 to $40,000 to beyond a reasonable doubt. Cash and negotiable instruments above $40,000 continue to require a lower burden of proof.

Requires Criminal Conviction in Civil Judicial Proceedings for Seizures Between $25,000 and $40,000. For all seized items for which proof beyond a reasonable doubt is required, the court can only issue an order for asset forfeiture if: (1) a defendant is convicted in a related criminal case, (2) the conviction is for an offense for which asset forfeiture is allowable under state law, and (3) the offense generally occurred within five years of the initiation of the asset forfeiture process. With SB 443 requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt for cash or negotiable instruments between $25,000 to $40,000, these three conditions must be met for these seizures as well.

Other Provisions

Senate Bill 443 requires that our office provide a report to the Legislature by December 31, 2019 containing data about the economic impact of the above changes on state and local law enforcement budgets. We note that SB 443 made various other changes to the state’s asset forfeiture processes. For example, it increased the types of asset forfeiture‑related information that state and local law enforcement agencies are required to report to the California Department of Justice (CA DOJ). However, SB 443 does not require our office to evaluate the impact of these other changes.

Difficult to Determine Economic Impact of SB 443 Changes

In preparing this report, we analyzed the annual asset forfeiture data submitted to and reported by CA DOJ. We also supplemented this data with various other federal, state, and local data. For example, we used federal asset forfeiture data as well as state and local law enforcement budget data. In analyzing the data, we identified a number of challenges with the data that make it difficult to isolate and determine the economic impact of the changes enacted by SB 443.

Data Reflect Impacts of Changes Outside of SB 443

A number of other changes occurred regarding asset forfeiture at both the federal and state level at or around the same time SB 443 became effective in January 2017. It is possible that some of these changes have increased distributions, while other changes could have reduced distributions. This means that the data reflect the net effect of all of these changes (including SB 443), making it difficult to separate the impact of SB 443 alone. We discuss these other changes to asset forfeiture processes below.

Federal Changes That Impacted Asset Forfeiture. The federal government made several changes to federal asset forfeiture processes that collectively could have impacted distributions to California law enforcement. For example, in recent years the federal government has no longer distributed asset forfeiture proceeds directly to taskforces. Instead, proceeds are only distributed to a fiduciary agency (an entity legally responsible for managing the assets for another entity) or directly to taskforce participating entities. Additionally, law enforcement agencies can no longer transfer federal asset forfeiture proceeds between themselves. These changes potentially make it more administratively and legally burdensome for certain law enforcement agencies to obtain forfeiture proceeds, particularly those agencies that only participate in asset forfeiture through taskforces. This burden could cause some agencies to limit their participation in taskforces, thereby reducing the amount of asset forfeiture proceeds they receive. However, the data might not fully reflect this as agencies could be in the process of still adapting to these changes.

State Changes That Impacted Asset Forfeiture. At the same time, a number of changes to California law similarly could have impacted the amount state and local law enforcement agencies receive from asset forfeiture. For example, Proposition 64 (2016) legalized cannabis and Proposition 47 (2014) reduced penalties for nonviolent drug crimes. Both of these changes likely resulted in reduced asset forfeitures.

Other Federal and State Actions. Other federal and state actions could have impacted asset forfeiture distributions. For example, due to budget cuts in 2015, the federal government delayed distributions from federal asset forfeiture proceedings for at least a year. This delay in payments likely means that asset forfeiture data following this period is skewed as the federal government distributed more monies than it otherwise would have. Similarly, local budgetary choices after the recession could have impacted the level of law enforcement or prosecutorial resources dedicated to asset forfeiture activities—and thereby the amount of asset forfeiture proceeds distributed.

Data Reported to CA DOJ Incomplete and Limited

Data reported to CA DOJ, which have been used for this report, is incomplete and limited for various reasons we describe below. This makes it even more difficult to determine the economic impact of the changes enacted by SB 443.

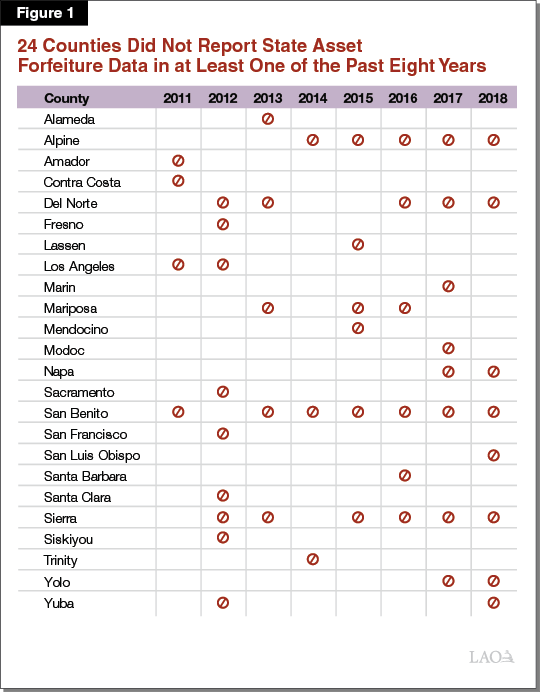

Reporting on State Cases Sometimes Did Not Occur. State law requires annual reporting on asset forfeiture cases that are resolved through state proceedings to the CA DOJ. However, 41 percent of the state’s 58 counties did not report such data in at least one of the past eight years. Figure 1 lists the 24 counties that did not report at least once in the past eight years and indicates the year in which they did not report. For example, Los Angeles County did not report in 2011 and 2012 while Sacramento County did not report in 2012. As a result, state data understate total state asset forfeiture proceeds—particularly in 2011 and 2012. It also makes it difficult to determine if changes in state asset forfeiture proceeds are a result of changes in the amount forfeited or simply changes in the amount reported. For example, a significant factor in the increase in state forfeiture distributions reported in 2013 was likely due to more complete reporting.

Amounts Provided to Certain Law Enforcement Agencies Could Be Understated. Data on state asset forfeiture cases included distributions to taskforces. However, based on certain taskforce agreements, some of these distributions are subsequently allocated to the local law enforcement agencies participating in the taskforce. These subsequent distributions are not reflected in the state data, meaning that total distributions to individual law enforcement agencies that received them are understated.

Law Enforcement Still Adapting to New Requirements to Report on Federal Distributions. Senate Bill 443 required reporting of new data related to distributions from federal asset forfeiture cases. However, it appears that the data could be incomplete. This could be partially due to this being a new reporting responsibility for law enforcement agencies and future reports could be more complete. According to the data, California law enforcement agencies received distributions from federal cases totaling $13.6 million in 2017 and $42.2 million in 2018. In comparison, the federal government reported distributions to California of $57 million in 2017 and $108.9 million in 2019. While this data cannot be readily compared—as discussed in more detail later—it suggests an underreporting of the state data. As a result, the data related to federal asset forfeiture distributions presented later in this report relies on the data reported by the federal government.

Less Than Two Years of Data Available After Implementation of SB 443. Data is generally reported when cases are resolved and distribution occurs—a process which can take months or years to complete. As a result, it is common for data on asset forfeiture distributions to lag by at least one year. Since SB 443 went into effect in January 2017, there is currently less than two years of complete data on its effects. This is insufficient to draw meaningful conclusions from. For example, it is likely that law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies are still adapting to SB 443’s changes. As a result, the impact of the measure’s effects on these agencies’ behavior will not be fully captured by the existing data.

Other Challenges Make Comparisons Difficult

To evaluate the economic impact of SB 443, we analyzed data reported to CA DOJ. We also supplemented that data with other federal, state, and local data. However, challenges with those data sources also make comparisons difficult.

Federal and State Annual Data Reports Begin in Different Months. The state and federal data used cover different time periods. For example, the federal data are generally based on the federal fiscal year (which begins in October) while the state data are based on the calendar year, or the state fiscal year (which beings in July). This can skew the data and the patterns observed.

Federal Data Include All Forfeitures. U.S. DOJ and the U.S. Department of Treasury both report data on total federal asset forfeiture distributions to individual states, including California. However, the data include asset forfeiture distributions for all criminal offenses—not just drug‑related asset forfeitures that were affected by SB 443. While stakeholders believe that a significant portion of these distributions are drug‑related, the precise portion is unknown.

Data on Distributions to Specific Agencies Excludes Some Federal Distributions. Both U.S. DOJ and the U.S. Department of Treasury report total federal asset forfeiture distributions by state. However, unlike the U.S. DOJ, the US Department of Treasury does not report the amount it distributes to individual law enforcement agencies—including those in California. Thus, data on the total amount of asset forfeiture distributions each law enforcement agency receives from the federal government are not available.

Data Related to Potential Impacts of SB 443

Despite the challenges described above, certain trends and patterns can be observed in the available data. While these trends and patterns cannot be solely attributed to SB 443, they can provide a sense of its potential impacts. In examining the data, we generally compared three time periods:

- Before 2015. Data from this period reflect asset forfeiture distributions before any components of SB 443 went into effect, including the prohibition of federal adoptions which was implemented by the federal government prior to the enactment of SB 443 (discussed below).

- 2015 to 2016. Data from this period begin to reflect the impact of the prohibition of federal adoptions. By suspending adoptions in January 2015, the federal government effectively implemented this aspect of SB 443.

- 2017 to Present. Data from this period begin to reflect the implementation of SB 443.

On net, the trends and patterns observed in the data suggest that SB 443 potentially reduced the amount of asset forfeiture distributions received by California. However, it is not possible to estimate the size of this potential impact due to the data challenges previously discussed. As such, the conclusions we draw below represent our best sense of the potential impact of SB 443, but should not be considered definitive.

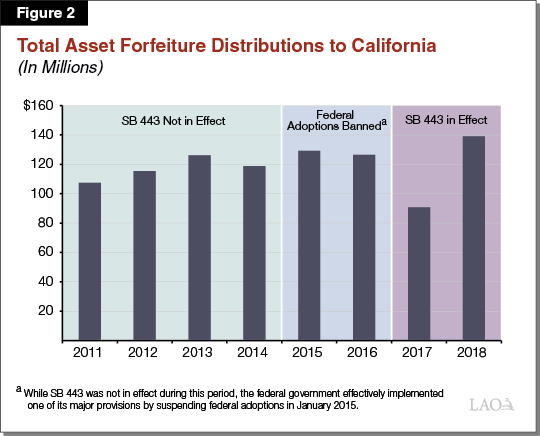

California Generally Receives More Than $100 Million Annually in Asset Forfeiture Distributions

As shown in Figure 2, California generally receives more than $100 million annually in total asset forfeiture distributions. Annual distributions between 2013 and 2016 fluctuated slightly, but were relatively stable. However, distributions decreased significantly by $35.8 million (or 28 percent) between 2016 and 2017—from $126.4 million to $90.7 million. This time period reflects the implementation of SB 443. In 2018, distributions rebounded with a $48.4 million increase (or 53 percent) from 2017. As we discuss below, virtually all of this 2018 increase is tied to a single asset forfeiture case that is likely unrelated to SB 443.

State and Federal Distributions Fluctuated in Recent Years

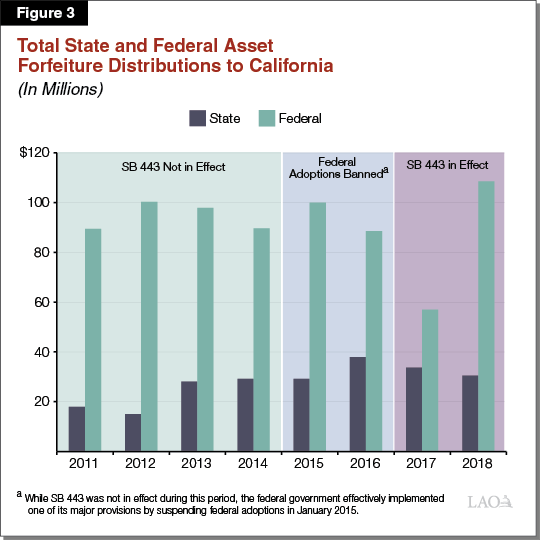

Figure 3 provides a breakdown of distributions from state and federal asset forfeiture cases. As shown, the amount of distributions from each type of case has fluctuated in recent years. In most years, state asset forfeiture distributions represent less than 30 percent of total asset forfeiture proceeds. As discussed above, the federal government prohibited adoptions beginning in 2015 (a prohibition subsequently included in SB 443). Between 2015 and 2016, state asset forfeiture distributions increased by 30 percent while federal asset forfeiture distributions declined by 11 percent. This could reflect law enforcement choosing to pursue cases at the state level as a result of the prohibition on federal adoptions.

In both 2017 and 2018, state asset forfeiture distributions declined by about 10 percent. Similarly, federal asset forfeiture distributions declined by 36 percent from 2016 to 2017—from $88.5 million to $57 million. These declines could reflect the impact of SB 443’s increased burden of proof and conviction requirements for state and federal cases, as well as the continued impact of the elimination of federal adoptions.

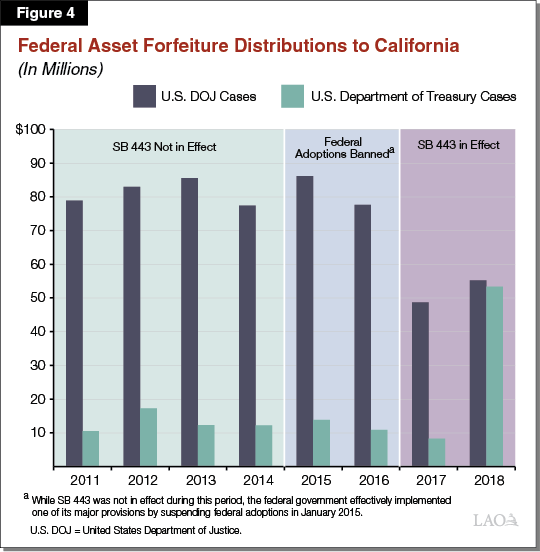

As shown in Figure 3, federal distributions increased by 91 percent in 2018—from $57 million to $108.6 million. However, as shown in Figure 4, this significant increase in 2018 is due to an unnaturally large increase in U.S. Department of Treasury asset forfeiture cases. Specifically, such distributions increased by $45 million (or 543 percent) between 2017 and 2018. This increase can be attributed to the distribution related to a single U.S. Department of Treasury case—likely unrelated to SB 443—that involved a bank accused of violating money laundering laws. At the same time, distributions from U.S. DOJ cases—which are more likely to be affected by SB 443 given that many involve drug crimes—increased by 13 percent (or $6.5 million) in 2018. Given that federal cases can only be pursued through joint investigations, this increase could reflect law enforcement pursuing more cases federally through joint investigations.

State Share of US DOJ Asset Forfeiture Distributions Has Significantly Declined Since 2017

Federal data indicate that hundreds of millions of dollars are collected and made available for distribution from U.S. DOJ asset forfeiture cases annually in California. (Comparable data are not available for U.S. Department of Treasury cases.) However, only a portion of this amount is distributed to agencies in the state, with the remainder distributed to various other purposes (such as federal law enforcement agencies). For example, in 2016, $117.5 million was collected and made available for distribution from U.S. DOJ cases in California while $77.6 million—66 percent—was distributed within the state. As shown in Figure 5, this represented a major increase in the state’s share. It is possible that this increase was due to the federal government delaying to 2016 some distributions that normally would have been allocated in 2015 due to budget cuts, as mentioned previously.

Following implementation of SB 443 in 2017, the state’s share significantly declined to 12 percent and remained at this level in 2018, as shown in Figure 5. This is potentially due in part to SB 443. For example, SB 443’s prohibition on receiving certain federal distributions without a conviction could have reduced the state’s share for a couple of reasons. According to stakeholders, federal entities are potentially less likely to pursue convictions due to the high burden of proof required. Stakeholders also indicated that it was often difficult to obtain information on whether a conviction occurred in federal cases, making agencies unable to receive distributions in such circumstances.

Number of State Cases Initiated Declined Between 2014 and 2017

As shown in Figure 6, the number of state asset forfeiture cases initiated declined by 26.6 percent between 2014 and 2017. While the earlier declines are unrelated to SB 443, the decline in 2017 could be due to the pursuit of fewer cases given SB 443’s new burden of proof and conviction requirements in state cases. For example, it is possible that certain law enforcement agencies began pursuing fewer seizures of assets between $25,000 and $40,000.

In 2018, however, the number of state cases initiated increased. This could suggest a shift away from federal cases back to state cases, partially in response to the implementation of SB 443. For example, some stakeholders reported that the various changes to the federal asset forfeiture process described above as well as the inability to obtain information from the federal government on whether a conviction was obtained—which is required under SB 443—could make asset forfeiture through federal proceedings less attractive.

Value of Assets Seized and Amount Distributed in State Asset Forfeiture Cases Increased Until 2016

Figure 7 shows the value of assets seized as well as the amount distributed in state asset forfeiture cases, which has fluctuated in recent years. As we discuss below, this likely reflects how certain individual law enforcement agencies may have changed in how they adapted to SB 433 during this time period.

As shown in Figure 7, both the value of assets seized and the amount distributed generally increased until 2016, before declining in 2017 (the year in which SB 443 was implemented). Specifically, the value of assets seized declined by 15 percent between 2016 and 2017 (from $49.5 million to $42.3 million), while the amount distributed declined by 11 percent (from $37.9 million to $33.7 million). This decrease could potentially reflect law enforcement agencies’ initial reactions to SB 443. For example, fewer asset forfeiture cases were potentially pursued in the short run before agencies determined how they would adapt their operations. Additionally, more cases could have instead been pursued at the federal level through joint investigations given the new burden of proof and conviction requirements for state cases. However, the trend in the value of assets seized and the amount distributed diverged in 2018.

Specifically, as shown in Figure 7, the value of assets seized in state cases increased by 13 percent between 2017 and 2018. This could reflect law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies beginning to adapt to SB 443 changes by identifying the most cost‑effective ways to modify their behavior and operations on an ongoing basis. For example, law enforcement agencies could be focusing on higher‑value seizures to avoid SB 443 thresholds requiring conviction. Law enforcement agencies could also be choosing to pursue more cases at the state level, instead of at the federal level. This could be due to challenges in obtaining information on federal convictions, which is required for law enforcement to receive distributions for certain asset forfeiture cases under SB 443.

In contrast to the increase in the value of assets seized, the amount distributed declined by another 10 percent between 2017 and 2018. The decrease in the amount distributed despite the increase in the value of assets seized could also reflect the impact of SB 443 changes. For example, the burden of proof and conviction requirements in state cases could result in distributions not occurring despite assets being seized as convictions were not obtained and/or the higher burden of proof requirements were not met.

Asset Forfeiture Distributions to Most Agencies Generally Declined Until 2018

State Asset Forfeiture Distributions to Law Enforcement Declined, Except for Taskforces. A little more than 500 prosecutorial and law enforcement agencies have received at least one distribution from state asset forfeiture dollars since 2011. As shown in Figure 8, police departments have typically received the greatest share of state asset forfeiture distributions. The amount distributed to police departments declined between 2016 and 2018, while the amount distributed to sheriffs’ offices declined between 2015 and 2018. The decline in distributions to police departments and sheriffs’ offices could reflect the impact of SB 443’s burden of proof and conviction requirements for state cases. As mentioned above, law enforcement could be pursuing fewer cases impacted by such requirements or might not be able to meet the burden of proof or conviction standards required to keep seized assets.

At the same time, the amount distributed to taskforces has steadily increased since 2016 with taskforces receiving the most in distributions beginning in 2017. This could potentially reflect law enforcement agencies choosing to increase their participation in taskforces as taskforces are potentially more effective at pursuing higher‑value cases not subject to SB 443 requirements. Additionally, this could reflect taskforces shifting more attention from federal asset forfeiture to state cases. This could be occurring given changes to federal asset forfeiture processes (such as the restriction on transferring distributions between participants) that could make it more difficult for taskforces to receive distributions from federal proceedings.

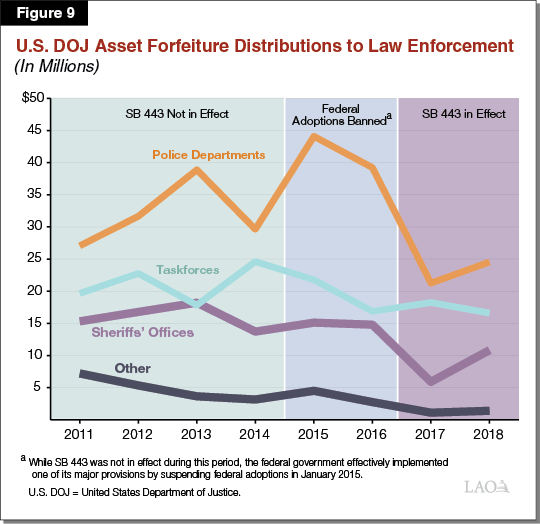

U.S. DOJ Distributions to Law Enforcement Agencies Generally Declined. As shown in Figure 9, police departments receive the most U.S. DOJ distributions. (Comparable data from U.S. Department of Treasury cases is unavailable.) In recent years, the amount of these distributions to law enforcement agencies has generally declined—potentially reflecting the impact of the prohibition on federal adoptions. However, the magnitude of the decreases varied. Agencies that relied more heavily on pursuing asset forfeiture cases through joint investigations would experience less of an impact, as such investigations remain permissible under SB 443. For example, certain taskforces have historically been comprised of federal, state, and local partners participating in joint investigations. Such taskforces would be impacted less by the prohibition on federal adoptions. This could partly explain why the amount distributed to taskforces did not decline as much compared to other law enforcement agencies prior to 2016. Additionally, the amount distributed to taskforces increased slightly between 2016 and 2017. This increase could reflect law enforcement agencies reacting to SB 443’s burden of proof and conviction requirements for both state and federal cases by choosing to pursue more asset forfeiture cases through joint investigations.

Between 2017 and 2018, distributions to both sheriffs’ offices and police departments increased, while distributions to taskforces decreased. The increase to sheriffs’ offices and police departments could indicate that they are adapting to SB 443 by increasing their participation in joint investigations. The decline in federal distributions to taskforces—along with the increase in state distributions to taskforces—is consistent with taskforces shifting their attention away from federal cases to state cases in response to changes in federal processes that make receiving distributions more difficult, as discussed above.

Asset Forfeiture Generally Reflects Small Share of Agency Budgets

Most Agencies Receive Less Than 1 Percent of Their Budget From Asset Forfeiture. Total asset forfeiture distributions represent a small share of total law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies’ budgets. (We would note, however, that asset forfeiture dollars can represent a sizeable portion of the budget of taskforces, though data on taskforce budgets are not readily available.) In recent years, asset forfeiture distributions made up less than 1 percent of the budget for more than 80 percent of agencies. For example, for those agencies with available data in 2018, 246 out of the 276 agencies that received distributions fell within this category. (For small agencies, a less than 1 percent share of the budget could represent only hundreds of dollars, while for a large agency it could represent the low millions of dollars.) Since 2016, the number of agencies for whom asset forfeiture distributions represent more than 1 percent of their budgets has slightly declined, which could reflect certain agencies pursuing fewer asset forfeiture cases or receiving fewer distributions due to SB 443.

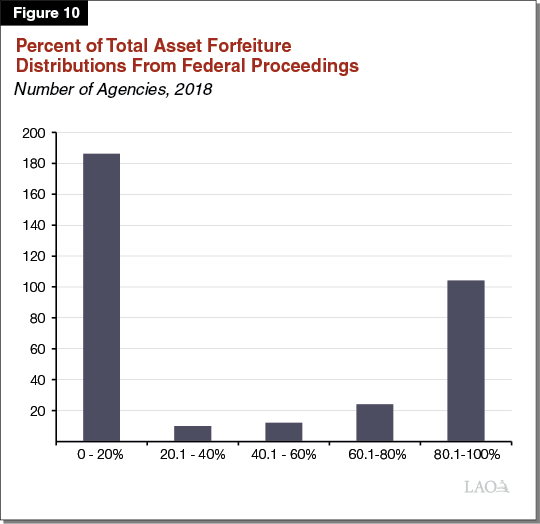

Majority of Agencies Receive Less Than 20 Percent of Asset Forfeiture Distributions From Federal Proceedings. As shown in Figure 10, in 2018, 186 out of 336 agencies (or slightly more than half) that received asset forfeiture distributions reported receiving less than 20 percent of their distributions from federal cases. However, 104 agencies reported receiving more than 80 percent of their distributions from federal cases. This pattern has fluctuated slightly in past years, but has generally remained stable. As such, despite the changes enacted by SB 443, a relatively consistent number of agencies continue to receive most of their asset forfeiture distributions from federal cases.

Conclusion

Senate Bill 443 implemented various changes to the state’s asset forfeiture processes and directed our office to provide data about the economic impact of these changes upon state and local law enforcement budgets. While the trends and patterns observed in available data suggest that SB 443 potentially reduced the amount of asset forfeiture distributions received by California agencies on net, it is not possible to estimate the size of this potential impact due to a lack of complete and accurate data as well as various challenges with the available data. As such, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the data. However, asset forfeiture distributions generally reflect a small share of agency budgets. Additionally, we would note stakeholders indicated that they were still in the process of adapting to SB 443 requirements as well as to the various changes in the federal asset forfeiture process. This means that data collected in future years could provide a more accurate—and potentially different—picture of the impact of SB 443.