LAO Contact

February 4, 2020

State Correctional Spending Increased Despite Significant Population Reductions

- Various Actions Have Reduced State Correctional Populations

- Despite Population Reduction, CDCR Spending Increased

- Population Decline Allowed State to Avoid Significantly Higher Costs

Summary

Over the past decade, the state has taken various actions that have significantly reduced the number of inmates and parolees under the supervision of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Most notably, legislation was enacted in 2011 that shifted (or realigned) the responsibility for certain offenders from the state to counties. This was done to help the state comply with a federal court order to reduce prison overcrowding, as well as reduce state costs. Voters have also approved a series of ballot measures that have impacted the inmate population, such as reducing penalties for certain offenders convicted of nonserious and nonviolent property and drug crimes. Since the implementation of the these and other policy changes, the state’s inmate population declined by nearly one‑quarter and the parolee population declined by nearly one‑half. However, over the same period, CDCR spending increased by over $3 billion, or more than one‑third.

Major Reasons for Spending Growth Despite Population Decline. In this brief, we describe the major reasons why CDCR’s costs did not decline in line with the substantial decrease in the populations. Specifically, while CDCR did experience some reduced costs associated with the decline in the populations, they were more than offset by increased costs primarily associated with three factors:

- Compliance With Court Orders. Despite the decline in the inmate population, the state had to maintain existing prison capacity, as well as take steps to actually expand capacity, in order to meet the federal court’s overcrowding limit. The state also made substantial improvements to inmate medical and mental health care to comply with court orders, particularly in terms of increased staffing.

- Increased Employee Compensation Costs. Increases in pension costs and raises given to employees caused employee compensation costs to grow substantially.

- Spending on Costs Deferred During Fiscal Crisis. The state is now paying for costs that were deferred during the fiscal crisis, such as furloughing of correctional officers.

Population Decline Allowed State to Avoid Significantly Higher Costs. We note that had the inmate population not declined over this period, CDCR spending would have increased by significantly more than it actually did. This is because the state would have had to finance the construction of several new prisons or contract for tens of thousands of prison beds. Accordingly, despite the growth in spending on CDCR, the state is likely spending billions of dollars less than it otherwise would be had it not taken actions to reduce the inmate and parolee populations.

Various Actions Have Reduced State Correctional Populations

Federal Courts Required State to Improve Inmate Health Care and Limit Prison Overcrowding. In December 1995, after finding the state failed to provide constitutional mental health care to inmates, a federal court in the case now referred to as Coleman v. Newsom appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on CDCR’s progress towards providing an adequate level of mental health care. In February 2006, after finding the state failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to inmates, a federal court in the case now referred to as Plata v. Newsom appointed a Receiver to take control over the direct management of the state’s prison medical care delivery system from CDCR.

In November 2006, plaintiffs in Coleman v. Newsom and Plata v. Newsom filed motions for the federal courts to convene a three‑judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act to determine whether (1) prison overcrowding was the primary cause of CDCR’s inability to provide constitutionally adequate inmate health care and (2) a prisoner release order was the only way to remedy these conditions. In August 2009, the three‑judge panel declared that overcrowding was the primary reason that CDCR was unable to provide adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison system. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per prison cell.) The court ruling applies to the number of inmates in prisons operated by CDCR and does not preclude the state from holding additional inmates elsewhere, such as conservation camps—which are generally jointly operated by CDCR and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection—and other publicly or privately operated facilities.

State Implemented Several Policy Changes to Reduce Prison Overcrowding. In order to reduce prison overcrowding, the state implemented various policy changes that significantly reduced the inmate population in recent years. Some of the major changes include:

- 2011 Realignment. The Legislature adopted a package of legislation that limited who could be sent to state prison. Specifically, it required that certain lower‑level offenders serve their incarceration terms in county jail. Additionally, the legislation required that counties, rather than the state, supervise certain lower‑level offenders released from state prison.

- Proposition 36 (2012). Voter‑approved ballot measure that changed the state’s “Three Strikes” law by generally eliminating life sentences for offenders with two or more prior serious or violent felony convictions whose most recent offenses are nonserious, nonviolent felonies. The measure also allowed offenders who were serving these sentences at the time to apply for reduced sentences.

- Proposition 47 (2014). This measure reduced penalties for certain offenders convicted of nonserious and nonviolent property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors—resulting in some offenders serving terms in county jail rather than state prison. The measure also allowed certain offenders who had been previously convicted of such crimes to apply for reduced sentences.

- Proposition 57 (2016). This measure reduced the amount of time inmates serve in prison primarily by expanding inmate eligibility for release consideration and increasing CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ sentences due to good behavior and/or the completion of rehabilitation programs.

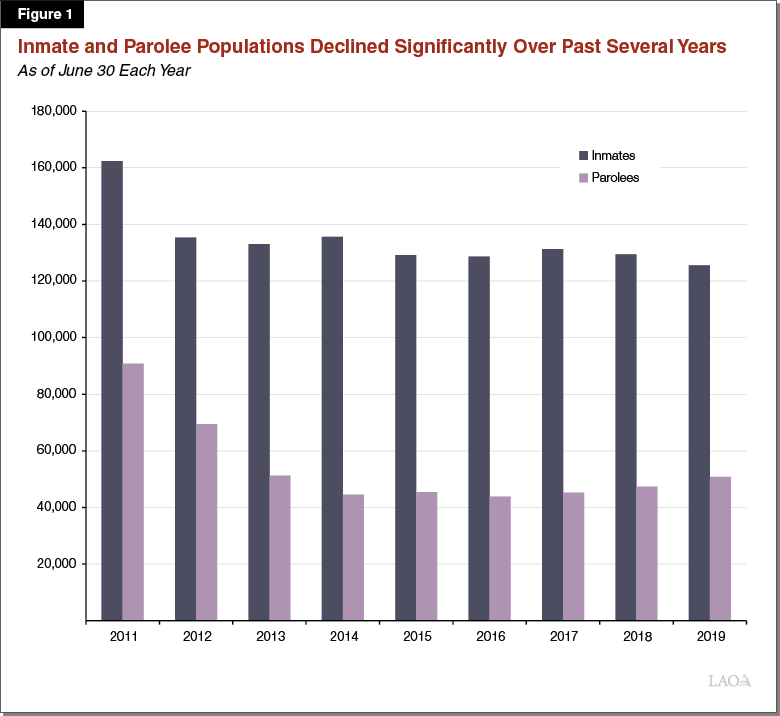

Inmate and Parolee Populations Have Declined Significantly. As shown in Figure 1, the state’s inmate and parolee populations have declined significantly over the past several years, primarily as a result of the above policy changes. Specifically, between June 30, 2011 and June 30, 2019, the inmate population declined from about 162,400 to 125,500 (23 percent) and the parolee population declined from about 90,800 to 50,800 (44 percent).

Despite Population Reduction, CDCR Spending Increased

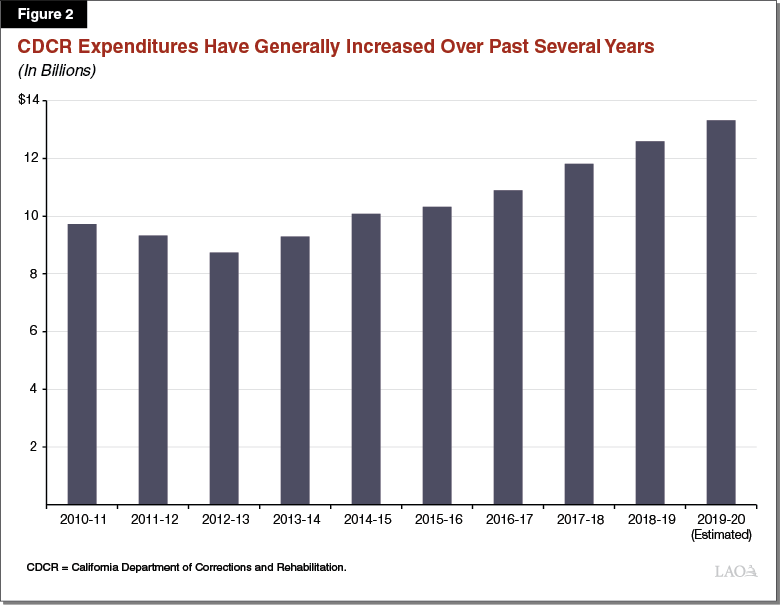

Although the state’s inmate and parolee populations have declined significantly in recent years, the level of spending on CDCR has increased. As shown in Figure 2 , expenditures increased by $3.6 billion (37 percent)—from about $9.7 billion in 2010‑11 to an estimated $13.3 billion in 2019‑20.

While many factors have contributed to the increase in CDCR spending over the past decade, we have identified three main factors: (1) costly operational changes to comply with various federal court orders, (2) increased employee compensation costs, and (3) the payment of costs that were deferred during the fiscal crisis. Below, we discuss each of these factors in further detail and how some of the increased costs are the result of more than one factor.

Various Court Orders Have Driven Costly Operational Changes

Despite Population Decline, State Was Not Able to Reduce Prison Capacity Given Overcrowding Limit. As discussed above, the federal court ruled that prison overcrowding had to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the state’s prison system. As such, although the number of individuals in state prison significantly declined, the state had to maintain its existing number of facilities—but house fewer inmates in them—to help meet the court order. Accordingly, the state did not realize a substantial reduction in staffing or costs because a large amount of prison operational costs are generally only eliminated when an entire prison or section of a prison is closed. We also note that the state continued to house inmates in out‑of‑state contract prisons in order to maintain compliance with the overcrowding limit.

State Also Activated New Capacity to Comply With Overcrowding Limit. In addition to maintaining existing prison capacity, the state also had to take steps to actually expand prison capacity and the number of available inmate beds in order to meet the court’s overcrowding limit. Otherwise, the state would have still exceeded the limit. Specifically, the state:

- Leased and Staffed California City Correctional Facility. Chapter 310 of 2013 (SB 105, Steinberg) gave CDCR the authority to lease the California City Correctional Facility from a private entity and operate the facility with state staff (similar to state‑owned prisons). The facility houses about 2,400 male inmates who are not counted toward the prison overcrowding limit. The state annually spends about $30 million to lease the facility and $100 million to operate it.

- Constructed and Staffed Three New Facilities at Existing Prisons. Chapter 42 of 2012 (SB 1022, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) authorized $810 million in lease revenue bond authority for CDCR to construct three inmate housing facilities at existing prisons. These facilities, which were activated in 2016, allow CDCR to house 3,267 additional inmates. The state annually spends over $70 million to operate these facilities and $58 million in debt service to repay the bonds. As of June 2019, the state had about $755 million in remaining debt to pay for the construction of these facilities.

- Constructed New Health Care Facility. The state constructed and activated in 2013 the California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton, which allowed CDCR to house 4,057 additional inmates. CHCF provides medical and mental health treatment to inmates who have the most severe and long‑term needs. The state spends $58 million in debt service annually for the facility. As we discuss in more detail below, the state also incurs significant costs to operate CHCF.

- Created Reentry Facilities. In 2014, CDCR began contracting with residential facilities in the community, which now house and provide rehabilitative programming (such as educational services, substance use disorder treatment, job training, and computer skills workshops) to male inmates within 12 months and female inmates within 30 months of completing their sentence. The 2019‑20 budget includes about $48 million to house about 1,100 inmates in such facilities.

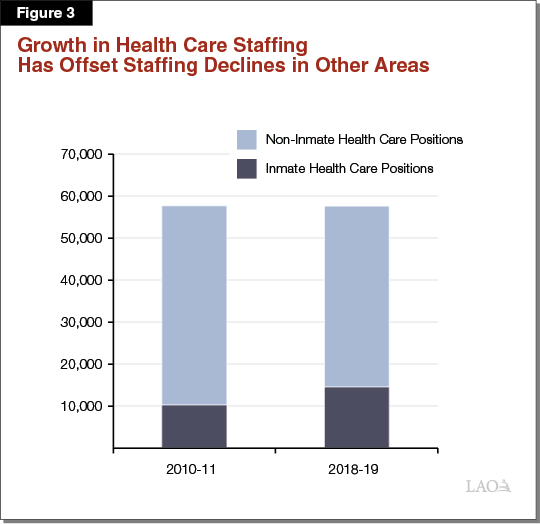

Improvements to Inmate Health Care Have Been Costly. In order to comply with court orders in the Plata and Coleman cases, the state substantially expanded inmate medical and mental health care services over the past several years. As a result, CDCR spending on inmate health care increased by about $1.4 billion (66 percent)—from about $2.2 billion in 2010‑11 to an estimated $3.6 billion in 2019‑20. Much of this increase is due to increased staffing. For example, the number of health care positions per inmate has nearly doubled—from 0.06 in 2010‑11 to 0.11 in 2018‑19 (the most recent complete data available). We note, however, that the number of non‑health care staff declined over the same time period. As shown in Figure 3, this resulted in overall staffing at CDCR being similar to its pre‑realignment level, but with a greater share being health care staff.

One of the most significant expansions of inmate health care during this period was the activation of CHCF. To operate CHCF, the 2019‑20 budget includes a total of about 4,000 positions, including about 2,600 health care and 900 custody positions. The state spends roughly $480 million annually to operate CHCF. Another significant expansion in inmate health care costs resulted from shifting responsibility for operating inpatient psychiatric programs in prisons from the Department of State Hospitals to CDCR. This change, adopted as part of the 2017‑18 budget package, was intended to improve care primarily by streamlining the process of transferring inmates into the program. The shift resulted in a roughly 1,400 position increase in CDCR health care staffing and a $260 million increase in CDCR spending between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18.

Cost Per CDCR Employee Has Increased

Although the total number of positions in CDCR is currently similar to its level prior to the 2011 realignment, the cost per position has increased—contributing to over $3 billion in increased CDCR spending. Whereas each position cost CDCR an average of $110,000 in 2010‑11, each position cost CDCR an average of $158,000 in 2018‑19, a 43 percent increase—nearly triple the rate of inflation.

Increased Pension Benefit Costs. One of the primary elements of employee compensation that has increased CDCR costs over the past decade is rising pension contribution rates. For example, the state’s contributions to pensions for CDCR’s correctional staff have grown from 29 percent of pay in 2010‑11 to 49 percent of pay in 2019‑20. Pension contribution rates are established by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System board. The board has increased contribution rates to pay for unfunded pension liabilities that grew during the fiscal crisis through a combination of (1) lower‑than‑assumed market returns and (2) new actuarial assumptions (specifically, the pension system now assumes that future returns will be lower and that retirees will live longer than was previously assumed).

Increased Employee Salaries. Growth in salaries has also been a major contributor to CDCR employee compensation costs. Since 2012‑13, the state’s labor agreements with the various bargaining units that represent CDCR employees have generally provided annual pay increases. For example, correctional staff—which make up half of CDCR employees—received pay increases ranging from 3 percent to 5 percent in all but one of the past seven fiscal years. (We note that many of the pay increases during this time period were established in labor agreements that also increased employee contribution rates to fund retirement benefits.)

Spending on Costs Deferred During Fiscal Crisis

Between 2008‑09 and 2012‑13, California faced annual budget shortfalls exceeding several billion dollars. The state took various actions to close these shortfalls, including reducing expenditures and shifting costs to the future. (For more information on this topic, see our report The Great Recession and California’s Recovery.) This made CDCR’s budget artificially low in these years and resulted in greater spending in future years. One significant example of this type of action was the furloughing of correctional officers. Between 2008‑09 and 2012‑13, many state workers—including CDCR correctional officers—were given increased leave time in exchange for reduced pay, known as “furloughs.” While this temporarily reduced CDCRs budget, it significantly increased correctional officer leave balances. This increased future costs in two ways. First, as these employees subsequently take vacation with leave time earned through furloughs, the state must pay other staff—often through overtime—to cover their positions. Second, the state must pay off any remaining leave when these employees separate from state service. Accordingly, some amount of CDCR’s employee compensation spending since furloughs ended in 2012‑13 is tied to these payments. (For more information on this topic, see our report After Furloughs: State Workers’ Leave Balances.)

Population Decline Allowed State to Avoid Significantly Higher Costs

As mentioned above, the state complied with the federal court’s overcrowding limit by both reducing the inmate population and expanding prison capacity. However, if the inmate population did not decrease and the state complied exclusively by expanding prison capacity, CDCR spending would be significantly higher than it is today. This is because the state would have had to finance the construction of several new prisons or contract for tens of thousands of prison beds. To the extent the state chose to construct additional prison capacity, it would have incurred increased operational costs to staff and operate the new facilities. Similarly, the state would have faced higher costs to increase the quality of health care for a greater number of inmates. In total, these additional costs could have been in the billions of dollars annually. Accordingly, despite the growth in spending on state corrections, the state is likely spending significantly less than it otherwise would be had it not taken actions to reduce the inmate and parolee populations.