LAO Contact

February 7, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Analysis of the Department of Developmental Services Budget

- Introduction

- Background

- Overview of the Governor’s Budget Proposal

- Rate Reform and Performance‑Based Incentives

- New Supplemental Provider Rates

- Enhanced Caseload Ratios for Children ages 3, 4, and 5

- Safety Net Plan

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

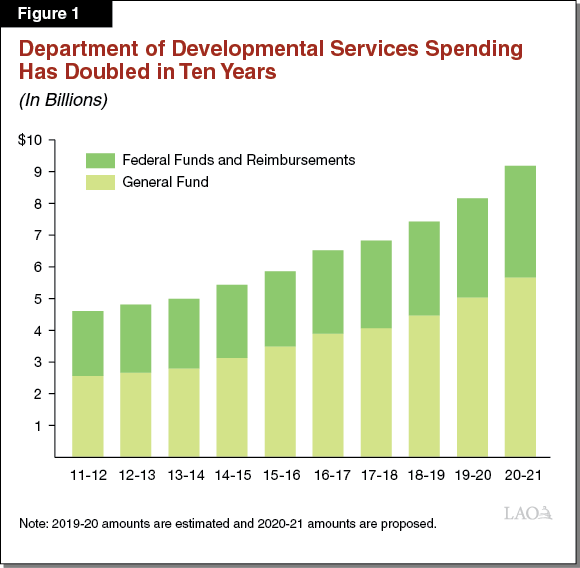

The Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) includes $9.2 billion from all fund sources, up $1 billion relative to revised 2019‑20 estimates. The General Fund accounts for $5.7 billion of proposed 2020‑21 spending, an increase of $622 million (12.3 percent) from revised 2019‑20 General Fund spending.

Year‑Over‑Year Spending Increase Is Due Largely to Caseload Growth, State Minimum Wage Impacts. DDS is estimated to serve 368,622 individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities (called “consumers” in statute) in 2020‑21, up 5.3 percent from 2019‑20. The cost to serve new consumers, as well as growth in the cost per case, accounts for $420.3 million ($263.4 million General Fund) of the total year‑over‑year increase. Spending for service providers’ costs associated with state minimum wage increases accounts for another $224.1 million ($114.6 million General Fund).

Major New Policy Proposal This Year Is for a Performance‑Incentive Program. The proposed budget includes $78 million ($60 million General Fund) to implement a performance‑incentive program for developmental services administered through Regional Centers (RCs). The program is subject to potential suspension on July 1, 2023. Its four broad goals are to improve quality, deliver “person‑centered” services, promote settings that integrate consumers in the community, and increase consumer employment. It would base incentive payments on whether RCs meet certain performance metrics, to be developed in consultation with the stakeholder community.

Current Conditions of the Developmental Services System Are Not Conducive to a Successful Performance‑Incentive Program. While the goals of the proposed program reflect legislative priorities for DDS, we find the system’s current conditions, particularly funding challenges, would significantly constrain the ability of RCs and service providers to respond to incentives in a way that would lead to the intended goals. In addition, we find that the proposed program’s structure lacks several criteria identified by researchers as optimal to result in a successful government performance‑incentive program. We also note that this proposal appears to move the system away from implementing rate reform—a key legislative interest over the last several years. This interest is reflected in the statutory requirement for a three‑year rate study (since completed) to modernize the DDS rate structure in an effort to address the sustainability and quality of developmental services provided in the community.

Recommend Legislature Reject Performance‑Incentive Proposal and Consider Its Preferred Way Forward for the DDS System. Given the above concerns, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposal for a performance‑incentive program, and instead consider the direction it would like to take the DDS system in the future. On the one hand, pursuing full implementation of the rate study’s recommendations over time would align the system with the guiding vision of the Lanterman Act, but it would increase costs significantly. If the Legislature pursued this path, we offer some suggestions for how to repurpose funding proposed in the Governor’s budget for the performance‑incentive program to begin to address some of the system’s chronic challenges. This path also could lay the foundation for pursuing a performance‑based incentive program in the future. On the other hand, the Legislature may choose a different path forward. If so, we suggest the Legislature begin to consider ways to change the system based on the Legislature’s priorities and available resources.

Governor Proposes Supplemental Rate Increases for Three Additional Services—Recommend Approval. The 2019‑20 budget included funding for supplemental rate increases of up to 8.2 percent in numerous service categories, effective January 1, 2020, at an annualized cost of $413 million ($250 million General Fund). Although these increases do not reflect implementation of the rate study’s recommended rate models, the selection of service categories to target was based on findings from the then‑draft rate study. The Governor’s budget proposes $18 million ($10.8 million General Fund) in 2020‑21 for supplemental rate increases for three additional services—infant development, Early Start therapeutic services, and independent living services—effective January 1, 2021. The addition of these three services to those services receiving supplemental rate increases reflects a correction made in the final version of the rate study, and thus is consistent with legislative intent in enacting the 2019‑20 increases. We therefore recommend approval of the proposed supplemental rate increases for the additional three service categories.

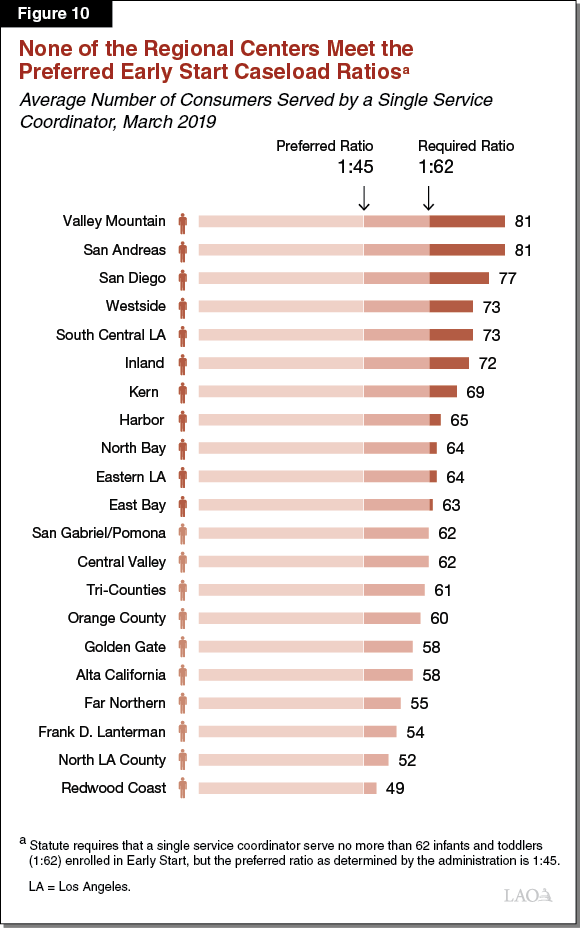

Governor Proposes Enhanced Service Coordinator Caseload Ratios for Children Ages 3, 4, and 5—Withhold Recommendation as Basis for Proposal Unclear. The proposed budget includes $16.5 million ($11.2 million General Fund) to reduce the RC service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratios to 1:45 for children ages 3, 4, and 5. Currently, federal funding agreements and state statute require average caseload ratios of 1:62 to 1:66 at each RC. The Governor’s proposal is based on the administration’s preferred caseload ratios of 1:45 in the Early Start program, which serves infants and toddlers under age 3 (statute limits average Early Start caseload ratios to 1:62). While the Governor’s proposal might have merit given developmental milestones at the targeted age range, it does not address other known problems with caseload ratios for service coordinators serving other age groups. In addition, whether all RCs have the same service coordination needs is unknown. Without prejudice to its merits, the Governor’s proposal lacks an analytic basis to determine where or for whom caseload relief is warranted. We therefore withhold recommendation on this proposal and suggest the Legislature ask for more information about the basis for this proposal at budget hearings this spring.

Governor Proposes Expanding Crisis and Safety Net Services for Consumers in Crisis—Recommend Approval and That Legislature Seek Information on Department’s Prioritization of Safety Net Spending. The Governor’s budget includes $20.9 million ($19 million General Fund) in 2020‑21 to expand the safety net as follows: (1) a temporarily increase in capacity (until 2024) at DDS’ secure treatment program at Porterville Developmental Center (PDC) for consumers currently in jail, (2) simultaneous development of five specialized homes that would ultimately replace the temporary increased capacity at PDC, and (3) an increase in crisis prevention training at four RCs (currently this model is being piloted at two RCs). We find that each of these three proposals has merit. The first two fill a current gap in the system that results in consumers inappropriately being placed in county jails and the third could increase the ability of RCs, service providers, and families to prevent crises from happening or from escalating. While we recommend that the Legislature approve the three proposals, we also recommend that the Legislature request more information from DDS to better understand how the department prioritizes its safety net spending in its long‑term planning efforts.

Introduction

The following report assesses the Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget for the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), which currently serves about 350,000 individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities in California. We first provide an overview of the budget proposal, including caseload projections and changes in year‑over‑year spending. We then consider four key new policy proposals. First, and most significantly, we consider the Governor’s proposal for a performance‑incentive program, which appears to represent a new direction for the DDS system. Second, we assess the Governor’s proposal to provide supplemental rate increases in additional service categories in 2020‑21. Third, we review a proposal to reduce the caseloads of service coordinators who work with children ages 3, 4, and 5. Finally, we examine the Governor’s proposed additions to DDS’ crisis and safety net services.

Background

Lanterman Act Lays Foundation for “Statutory Entitlement”. . . California’s Lanterman Act was originally passed in 1969 and substantially revised in 1977. It amounts to a statutory entitlement to services and supports for individuals with qualifying developmental disabilities. By passing the Lanterman Act and subsequent legislation, the state committed to providing the services and supports that all qualifying “consumers” (the term used in statute) need and choose to live in the least restrictive environments possible. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria.

. . . Although Spending on Services Is Limited to Funding Provided. Although the Lanterman Act entitles consumers to the services and supports they need, it also states that DDS cannot require Regional Centers (RCs)—the agencies that coordinate services for consumers—to spend more on services than what has been appropriated.

DDS Is Closing Its Last General Treatment Developmental Center (DC) . . . Pursuant to the plan proposed by the Governor and approved by the Legislature in 2015, DDS is closing its last general treatment DC—Fairview DC in Costa Mesa (Orange County). DDS plans to move the final resident this month. In December, DDS closed the General Treatment Area of Porterville DC (PDC) in Porterville (Tulare County). DCs were large state‑operated institutions for individuals with developmental disabilities. At one time the state operated as many as seven DCs, but as integration of consumers into the community and consumer choice have grown in importance, institutional settings are less common. Most former DC residents transitioned to community‑based homes (a small share live in intermediate care facilities or skilled nursing facilities).

. . . And Aside From Two State‑Operated Facilities, DDS Now Administers a Fully Community‑Based System. DDS continues to operate a secure treatment program at PDC for consumers placed there by court order. PDC includes competency training for consumers deemed incompetent to stand trial (IST). Statute limits the number of PDC residents to 211. DDS also operates a leased community facility—Canyon Springs in Cathedral City (Riverside County)—which serves up to 56 consumers, many of whom are transitioning from PDC. Otherwise, DDS’ consumer population now is served in community settings.

DDS Contracts With 21 RCs, Which Coordinate and Pay for Consumer Services. Community services are coordinated by 21 nonprofit RCs, which contract with DDS. RCs pay for consumers’ direct services, which are delivered by a large network of private and nonprofit service providers. Most consumers also receive services through other state programs, such as Medi‑Cal (California’s Medicaid program), public schools, or In‑Home Supportive Services. If a service can be accessed through one of these other programs, RCs cannot pay for that service.

Overview of the Governor’s Budget Proposal

Governor’s Budget Proposes More Than $9 Billion to Fund Developmental Services. The Governor proposes $9.2 billion (total funds) in spending for DDS in 2020‑21, up more than $1 billion (12.4 percent) relative to revised 2019‑20 spending of $8.2 billion. The General Fund accounts for $5.7 billion—or about 62 percent—of proposed 2020‑21 spending, an increase of $622 million (12.3 percent) from revised 2019‑20 General Fund spending of $5 billion. Figure 1 shows growth in the DDS budget over the last decade.

Caseload Projections

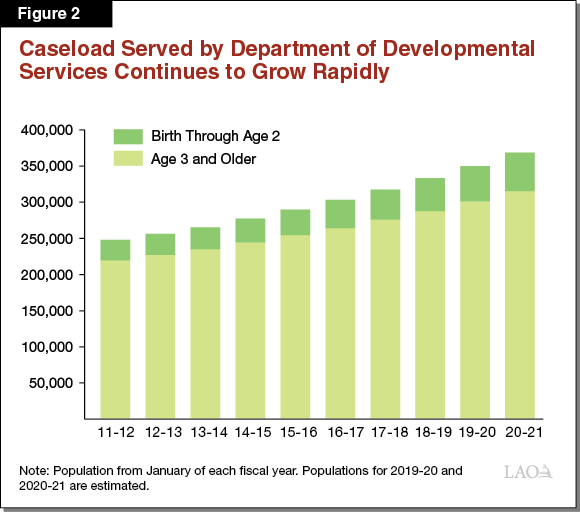

Caseload Continues to Grow Rapidly. The number of consumers served in the DDS system—projected by the administration to be 368,622 in 2020‑21—continues to grow rapidly. While California’s overall population has grown by less than 1 percent on average in recent years (and the number of births in the state was down between 2017‑18 and 2018‑19), DDS caseload has grown by 5 percent on average in recent years. The DDS caseload is projected to add 18,575 new consumers in 2020‑21, growing by 5.3 percent relative to revised 2019‑20 estimates. DDS’ Early Start Program—which serves children under age 3 who have a developmental delay—is growing particularly fast—twice as fast as the consumer population age 3 and older. Figure 2 shows growth in the DDS system over the past ten years.

Governor’s Caseload Assumptions Reflect Recent Trends and Appear Reasonable. Although the reasons for the growth in DDS caseload are not entirely clear (a large part of the explanation may be better diagnoses than in the past), the Governor’s assumptions about the population in 2020‑21 reflect trends in recent years and are very close to our own estimates.

Current‑Year Adjustments

The Governor’s budget estimates a net decrease in spending of $63 million ($14.3 million General Fund) in the current year for community services and a net increase of $5 million ($4.1 million General Fund) for state‑operated facilities.

Purchase‑of‑Service (POS) Expenditures Revised Downward. Most of the current‑year change in community services is due to reduced POS spending, which is estimated to decline by $63.9 million ($41.7 million General Fund). The decline is driven primarily by reduced spending on state minimum wage increases, which is based on actual requests to date from service providers for related adjustments. The decrease in General Fund spending is offset to some degree by the correction of an accounting error that results in increased General Fund spending on RC operations in the current year.

Budget‑Year Adjustments and Policy Proposals

Three Primary Factors Drive Spending Increase. A $1 billion increase ($627.2 million General Fund) in proposed 2020‑21 spending on community services relative to revised 2019‑20 estimates primarily is due to the three factors discussed below that reflect workload budget adjustments (as opposed to new policy proposals). Increased spending on community services is partially offset by decreased spending of $26.2 million ($16.7 million General Fund) on state‑operated facilities.

- Caseload and Use of Services. The increase in the number of consumers served and changes in the mix and amount of services used by each consumer account for $420.3 million ($263.4 million General Fund) of the increase.

- State Minimum Wage. Funding to help service providers pay for the rising cost of state minimum wage increases accounts for another $224.1 million ($114.6 million General Fund) of this increase. This includes the full‑year costs of the increase from $12 to $13 that began January 1, 2020 and half‑year costs of the increase from $13 to $14 that is scheduled to begin on January 1, 2021.

- Full‑Year Implementation of Supplemental Rate Increases. The 2019‑20 Budget Act included half‑year costs for supplemental rate increases of up to 8.2 percent in numerous service categories. The increases took effect January 1, 2020. The proposed 2020‑21 budget includes an additional $206.2 million ($124.5 million General Fund) to account for the full‑year cost of these increases. The potential suspension of these rate increases also was extended 18 months from December 31, 2021 to July 1, 2023.

Key New Policy Proposals Account for Most of the Remaining Increase. The increase in year‑over‑year spending also reflects several key new policy proposals, which we assess in later sections of this report.

- Performance‑Based Incentives. The Governor’s budget proposes $78 million ($60 million General Fund) for a new performance‑based incentive program, the goal of which is to encourage quality improvements in services and consumer outcomes. Funding is subject to the same possible suspension on July 1, 2023 noted above.

- Supplemental Provider Rate Increases for Three Additional Services. The Governor proposes $18 million ($10.8 million General Fund) for the half‑year cost of supplemental rate increases for three additional services—infant development, Early Start therapies, and independent living services. Rate increases would take effect January 1, 2021 and are subject to potential suspension on July 1, 2023.

- Enhanced Caseload Ratios for Children Ages 3, 4, and 5. The Governor proposes $16.5 million ($11.2 million General Fund) to reduce caseloads for RC service coordinators who work with children ages 3 through 5 and their families. The Governor proposes a 1:45 caseload ratio (or one service coordinator for every 45 children). Currently, required caseload ratios for this age group are 1:62 for children enrolled in the Medicaid waiver or 1:66 for children not enrolled in the Medicaid waiver. (The Medicaid Home‑ and Community‑Based Services waiver provides federal matching funds for services at a level required to help a Medicaid‑ [called Medi‑Cal in California] eligible consumer live in the community and who, if not for this funding, would require care in a more institutional setting. This waiver accounts for more than 25 percent of funding in the DDS budget.)

- Safety Net Expansion. Chapter 28 of 2019 (SB 81, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) required DDS to submit an updated safety net plan in conjunction with the release of the Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget. DDS submitted this plan on January 10. The “safety net” provides services for consumers at risk of or experiencing a crisis and for those who may be at risk of losing, or who have lost, their residential placement due to a crisis. The Governor’s budget includes the following proposals as part of the updated plan:

- Additional Temporary Capacity at PDC. The Governor’s budget proposes $8.9 million General Fund to add temporary 20‑bed capacity (one intermediate care facility unit) at PDC for DDS consumers who are currently in county jails awaiting a PDC placement and who have been deemed IST. These beds would be available through June 30, 2024.

- Additional Community‑Based Specialized Homes for Former PDC Residents. The budget proposal includes $7.5 million General Fund for the development of five new enhanced behavioral supports homes (EBSHs) that include delayed egress (meaning there is a short delay and alarm if a consumer tries open an exit door) and secured perimeter (which is a locked fence surrounding the property). These homes would serve consumers who were at PDC because they were a safety risk to themselves or others.

- Crisis Prevention Training. In 2019‑20, DDS began pilot testing a crisis prevention training program at two RCs. The Governor’s budget proposes adding training at four additional RCs in 2020‑21, at a cost of $4.5 million ($2.6 million General Fund).

Rate Reform and Performance‑Based Incentives

Background

How Community Services Are Funded

RCs Pay Providers for Each Service Based on a Rate; Current Rate Structure Outdated. Service providers around the state deliver a wide variety of services and supports to DDS consumers, including residential services, day programs, employment support, independent and supported living, and personal assistance. RCs pay providers a rate for each service provided based on a set of service codes. This system, which is akin to a “fee‑for‑service” model, includes more than 150 service codes. Traditionally, the specific rates paid for each service were set in a number of different ways, including by DDS, statute, negotiation between providers and RCs, or other departments. Budgetary conditions over the past couple of decades led to numerous incremental changes to both the rates and the rate‑setting methods. These piecemeal changes made the rates overly complex, inequitable across similar providers, and hard to understand. In addition, there generally is common agreement that the current rate structure does not result in funding levels that align with the funding requirements of the DDS system, which are based on current laws and demand for services.

Recent Rate Study Examined Rate‑Setting Process and Associated Funding Gaps . . . To address the problems associated with service provider rates (both the structure and level of rates), the Legislature approved $3 million General Fund in 2016 for DDS to conduct a rate study over a three‑year period. DDS contracted with health policy consultants, Burns and Associates, to conduct the study, the results of which were delivered in draft form on March 15, 2019 and in final form on January 10, 2020. The rate models recommended by the study provide similar rates for similar services, include assumptions and inputs that can be modified or updated, allow for adjustments based on regional and other cost differences, and reflect rate levels necessary to meet service needs. Not factoring in the increased funding associated with 2019‑20 supplemental rate increases, Burns and Associates estimated that if the rate models were fully implemented, DDS spending would increase $1.8 billion in total funds (about $1.1 billion General Fund) relative to 2019‑20 spending.

. . . But Recommendations Have Not Been Implemented. The Governor has not proposed implementing the rate models developed by Burns and Associates. Last year’s budget actions increased funding for supplemental rate payments to certain providers, rather than implement the rate models. DDS has committed to discussing “system and fiscal reform” through a new workgroup (of the same name) comprised of family members, advocates, service providers, RC representatives, and others.

Some Funding Allocations Take Place Outside the Traditional Rate‑Setting Process. In addition to paying for services through the rate‑setting process, DDS has several separate funding allocations, some with set annual funding amounts. Figure 3 lists some of these allocations.

Figure 3

DDS Allocations That Operate Outside of Traditional Rate‑Setting Process

|

Allocation |

Purpose |

Amount (General Fund) |

Year Authorizing Legislation Approved |

|

Employment‑Related Incentives |

|

$20 million annually. |

2016‑17 |

|

|||

|

Reducing Disparities |

Grants to RCs and community‑based organizations to implement recommendations and plans to reduce disparities in RC services. |

$11 million annually. |

2016‑17 |

|

Compliance With HCBS Rule |

Funding to help providers achieve compliance with federal HCBS rules by March 17, 2022. Awards based on demonstrated need. |

$15 million annually. |

2016‑17 |

|

Specialized Home Service Rates |

Negotiated rates for service providers at specialized homes (ARFPSHN, CCH, and EBSH). |

At least $83.6 million spent in total in 2018‑19.a |

2005‑06 (ARFPSHN), 2014‑15 (CCH/EBSH) |

|

Average per‑person spending is more than three times what it is at the most intensive community care facilities. |

|||

|

CPP/CRDP |

|

About $60 million to $68 million annually. |

2002‑03; CRDP added in 2017‑18 |

|

|||

|

aThis amount does not include the service provider billing for vacancies (which is allowed via the contracts with Regional Centers), nor does it include the amount of contract purchase‑of‑service dollars for ARFPSHN homes. |

|||

|

DDS = Department of Developmental Services; RC = Regional Center; HCBS = Home‑ and Community‑Based Services; ARFPSHN = Adult Residential Facility for Persons with Special Health Care Needs; CCH = Community Crisis Home; EBSH = enhanced behavioral supports home; CPP = Community Placement Plan; and CRDP = Community Resource Development Plan. |

|||

The purpose of these alternative payments is to address some of the particular service requirements that were not being met under the rate‑setting process.

DDS Oversight of the System

DDS Oversees RCs Through Performance Contracts. One way DDS conducts oversight of RCs is through contracting. Statute requires the state to enter into five‑year contracts with RCs. These contracts include annual performance objectives—such as how many consumers live in homelike settings or how many consumers have competitive job placements—as well as annual performance reporting requirements. Currently, RCs’ funding levels are not contingent on their performance under these contracts.

DDS’ Current Data Systems Provide Limited Ability to Understand Unmet Needs. The current data available about DDS consumers and services are not comprehensive and are not collected in a systematic manner. This makes understanding the extent to which service needs go unmet across the state difficult. In particular, DDS does not collect enough data to quantify whether service providers have sufficient capacity to meet consumers’ diverse needs or whether consumers have sufficient choice among providers.

Proposed Performance‑Incentive Program

Overview of Proposed Program

The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposes $78 million ($60 million General Fund) annually to establish a performance‑incentive program for developmental services that are administered through the RC system. The program would be subject to potential suspension on July 1, 2023.

Program Goals Prioritize Quality, Person‑Centeredness, Integration, and Consumer Employment. The proposed program has four stated goals: (1) having a quality system that values consumer outcomes, (2) developing services that meet consumer needs in a person‑centered way, (3) promoting settings that better integrate consumers into the wider community, and (4) increasing the number of consumers that have competitive (minimum wage or higher) job placements in the mainstream community.

RC Contracts Would Be Based on New Program Goals. DDS intends to work with the System and Fiscal Reform Workgroup of the Developmental Services Task Force to determine which outcomes align with the stated goals and how to measure them. These measures—or metrics—would form the basis of RC contracts moving forward.

RCs Would Be Eligible for Performance Payments for Certain Metrics. DDS would revise RC performance contracts to reflect the systemwide agreed‑upon metrics. RCs would be eligible for additional payments by meeting certain metrics—called “advanced tier” metrics. These metrics would be weighted (some would be more important than others), and RCs could receive a varying amount of incentive funding, depending on which metrics they meet.

In the First Year, DDS Proposes to Improve Data Quality and RC Infrastructure. DDS indicates that in the first year of the proposed incentive program, the funding would allow RCs to improve the quality and consistency of data collected and to ensure adequate infrastructure (such as contracting processes or payment practices) is in place to carry out the program.

DDS Is Modeling This Idea on Programs in Other States. DDS developed this proposal based on communications with the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services and by examining similar programs in other states, such as Louisiana.

LAO Assessment

Improving service quality, delivering person‑focused services, increasing accountability of RCs and service providers, and thinking innovatively aligns with the Legislature’s priorities for DDS. As discussed below, however, the DDS system’s current conditions are not suited for implementing the proposal. Specifically, RCs and service providers are not in a position to respond to the incentives in such a way that would lead to the program’s intended goals. Below, we discuss an evaluation framework for thinking about performance incentives and describe the challenges currently facing the DDS system that make implementation of a performance‑incentive program premature.

Optimal Conditions for Successful Government Performance‑Incentive Programs

In 2010, the RAND Corporation released a study examining nine “performance‑based accountability systems” (systems that provide incentives based on measured outcomes to improve public services) in five public sectors: child care, education, health care, public health emergency preparedness, and transportation. The study found that the conditions listed in Figure 4 are optimal for success. We will use these conditions as an evaluation framework for considering the Governor’s proposed performance‑incentive program. RAND notes that while fully realizing all six of these conditions is rare, decision makers should assess whether sufficient conditions are present to make a performance‑based accountability system the most appropriate and cost‑effective policy intervention.

Figure 4

Excerpted From RAND Studya on

Performance‑Based Accountability Systems for Public Services

|

Optimum circumstances include having the following: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aRAND Corporation (2010). “Toward a Culture of Consequence: Performance‑Based Accountability Systems for Public Services.” |

In addition, RAND found that successful implementation of a performance‑based accountability system requires getting past certain pitfalls, such as lack of experience managing such systems or lack of infrastructure to support it, unrealistic time lines, overly complex design, lack of communication, and resistance from stakeholders. The study notes that assessing “upfront whether providers have sufficient resources to do what is required of them” is important.

RAND found examples of strategies that can aid public agencies in avoiding these pitfalls. For example, public agencies can pilot‑test the system to identify problems or challenges. Exploiting existing infrastructure (such as building on top of existing structures) and implementing the system in stages can reduce implementation time and minimize the effect of mistakes in the system. The report recommends regular and effective communication with stakeholders, as well as regular monitoring of the system to identify and correct problems on an ongoing basis.

Proposal Meets Few of RAND’s Conditions

Lacks Some of RAND’s Optimal Conditions for a Successful Performance‑Based System. Figure 5 summarizes our assessment of the extent to which the Governor’s proposal meets the six major conditions the RAND study says are optimal for a successful performance‑based system. We discuss these further below.

- Widely Shared Goal. The proposal appears to have one condition in place—a widely shared goal. The broad goals of the program (quality, person‑centeredness, integration, and consumer employment) reflect previously established legislative priorities and most likely are shared by RCs, service providers, and consumers and their families.

- Clear, Observable Measures. Currently, the program proposal does not specify which measures will be used. DDS is engaging stakeholders to develop the measures (which is a good step given the importance of stakeholder buy‑in), however, whether the ultimate choice of measures will be appropriate is unknown. For example, among other measures, DDS mentioned the possibility of using quality‑of‑life measures, which are subjective measures whose accuracy depends heavily on how the responses are obtained, particularly in the context of individuals with developmental disabilities. In light of this concern, pairing such measures with more objective ones will be important.

- Properly Aligned Incentives. The proposal is vague about how the incentives would be aligned. Although the program would provide the incentive payments to RCs, many of the goals depend on the quality of services delivered by the large network of service providers. Without aligning incentives with the right actors—those whose behavior affects outcomes—success may be difficult.

- Meaningful Incentives. Whether the incentives—monetary or otherwise—would be meaningful enough to change behavior is unknown given the current lack of detail on the structure of the incentives. RAND notes that the “size of an incentive should reflect the value to the government of changing the targeted behavior” and recommends an incentive large enough to offset the costs of effecting that change in behavior.

- Few Competing Interests or Requirements. The DDS system has numerous federal, statutory, regulatory, and practical requirements that create competing demands for the attention of RCs and service providers. Such demands include ensuring compliance with federal rules to receive federal funding; completing reports and other tasks related to consumer health and safety; responding to various administrative, accounting, and reporting requirements; and training new staff. The combination of these various requirements means that RC staff and service provider staff may not have sufficient time and resources to effectively respond to the proposed incentives. While some of the goals of the proposal would align with existing requirements, the administration has not provided sufficient detail to determine the extent to which this would be the case.

- Sufficient Resources to Run the Program. Whether the amount proposed for the program—$78 million ($60 million General Fund) annually—is sufficient to design, implement, administer, and monitor the program is unclear. How the Governor chose this amount also is unclear.

Figure 5

DDS’ Proposed Performance‑Incentive Program

Lacks Important Conditions for Success

|

Conditions |

Does the Proposed Program Currently Have This Element? |

||

|

Yes |

No |

Unclear |

|

|

Widely shared goal |

|||

|

Clear, observable measures |

X |

||

|

Properly aligned incentives |

? |

||

|

Meaningful incentives |

? |

||

|

Few competing interests |

X |

||

|

Sufficient resources |

? |

||

|

DDS = Department of Developmental Services. Note: Conditions for a successful performance‑based accountability system are taken from Rand Corporation’s 2010 report, “Toward a Culture of Consequences: Performance‑Based Accountability Systems for Public Services.” |

|||

The Governor’s Proposal Does Not Describe Oversight or Evaluation Mechanisms. As currently described, the proposal lacks well‑defined oversight and evaluation mechanisms to ensure program fidelity. Incentive programs have the potential to yield unintended consequences, such as achieving the performance measure, but not achieving the program goal. Given the funding challenges in the current system, incentive payments could be especially problematic. Oversight of the performance‑incentive program would be necessary to ensure that potential recipients do not circumvent important rules or compromise quality to meet a particular metric. Including evaluation components to assess the program’s ongoing success at achieving the stated goals also would be critical.

Proposed Program Does Not Address Existing Problems in the DDS System

DDS System Has Fundamental Challenges. The DDS consumer population continues to grow in number and change in composition. Numerous challenges currently strain the system as it tries to adapt to the evolving needs of the population, the most fundamental of which are funding‑related in nature. We summarize these issues below.

- Outdated Rates and Rate Structure. As noted previously, the current DDS rate structure is not aligned with current service needs, treats similar service providers differently, and—according to the rate study—has a sizeable funding gap ($1.8 billion [$1.1 million General Fund] not accounting for last year’s supplemental rate increases). Moreover, minimum wage increases exacerbate funding challenges in several ways. First, the rising state minimum wage creates upward pressure on the wages of service provider employees who make just above the minimum wage, but the rate adjustments provided for state minimum wage increases do not account for these compaction pressures. Second, the state has not adjusted provider rates to account for costs associated with local minimum wage ordinances. Third, the rate adjustments provided to cover costs associated with state minimum wage increases have not been available to providers in areas with local minimum wages that exceed the state minimum wage. Figure 6 shows the local areas in which providers were unable to access funding associated with the January 1, 2020 state minimum wage increase from $12 to $13 per hour.

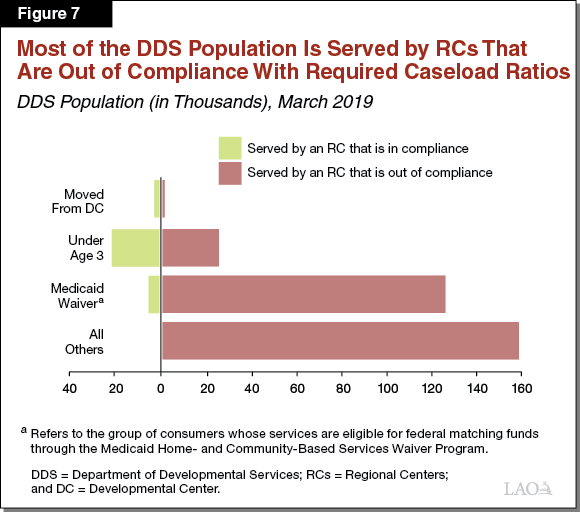

- Caseload Growth. The rapidly growing number of consumers and their changing demographics strain the service provider network as well as RC service coordinator caseloads. While state law and federal agreements stipulate the average service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratio that an RC may have, Figure 7 shows that more than 90 percent of consumers are served by RCs whose caseload ratios exceed requirements.

- Lack of Data. Because the DDS system does not collect data in a systematic way, understanding service gaps—which could inform policy and spending decisions by the Legislature—is difficult.

Figure 6

Local Areas in Which Providers Cannot Request DDS Funding Associated With January 2020 State Minimum Wage Increase From $12 to $13 Per Hour

|

City or County |

Employer Size |

Local Hourly Wage |

|

Belmont |

$13.50 |

|

|

Berkeley |

15.59 |

|

|

Cupertino |

15.00 |

|

|

El Cerrito |

15.00 |

|

|

Emeryville |

16.30 |

|

|

Fremont |

26+ employees |

13.50 |

|

Los Altos |

15.00 |

|

|

Los Angeles City |

26+ employees |

14.25 |

|

Los Angeles City |

Under 26 employees |

13.25 |

|

Los Angeles County—unincorporated areas |

26+ employees |

14.25 |

|

Los Angeles County—unincorporated areas |

Under 26 employees |

13.25 |

|

Malibu |

26+ employees |

14.25 |

|

Malibu |

Under 26 employees |

13.25 |

|

Milpitas |

15.00 |

|

|

Mountain View |

15.65 |

|

|

Oakland |

13.80 |

|

|

Palo Alto |

15.00 |

|

|

Pasadena |

26+ employees |

14.25 |

|

Pasadena |

Under 26 employees |

13.25 |

|

Redwood City |

13.50 |

|

|

Richmond |

15.00 |

|

|

San Francisco |

15.59 |

|

|

San Jose |

15.00 |

|

|

San Leandro |

14.00 |

|

|

San Mateo |

For‑profits |

15.00 |

|

San Mateo |

Nonprofits |

13.50 |

|

Santa Clara |

15.00 |

|

|

Santa Monica |

26+ employees |

14.25 |

|

Santa Monica |

Under 26 employees |

13.25 |

|

Sunnyvale |

15.65 |

|

|

DDS = Department of Developmental Services. |

||

Proposed Performance‑Incentive Program Does Not Address Most of These Challenges. Without addressing the existing challenges, providers are not positioned to respond to an incentive‑based system, such as the one proposed. While some elements of the proposal—like updating data systems—would lay the foundation for performance‑based incentive contracts with RCs, the proposal otherwise does not set up many of the optimal conditions for success.

LAO Recommendations

Reject Proposal

Proposed Incentive Program Addresses System Challenges at the Edges Only . . . The proposed performance‑incentive program does not address the fundamental financial challenges facing the DDS system. Instead, the proposal appears to take the system in a new direction by changing RC performance contracts and basing new funding on yet‑to‑be determined metrics.

. . . And Will Likely Not Work Well Under Current Conditions. If designed well under the right conditions, the proposed performance‑incentive program could have the potential to improve service quality and consumer outcomes. However, under current conditions in which numerous challenges strain the system, the program would not have a foundation conducive to success. Consequently we recommend the Legislature reject the proposal to provide incentive‑based payments.

The administration’s proposal to update RC contracts, however, has merit. We recommend these contracts be revised to reflect more meaningful and relevant measures (developed in conjunction with stakeholders).

Recommend the Legislature Request Additional Information About the Administration’s Long‑Term Vision for the DDS System. The Governor’s proposed DDS budget appears to move away from implementation of the rate study, given that neither the revised 2019‑20 budget proposal nor the current budget proposal includes steps to implement it. The Legislature might wish to ask the department at budget hearings to provide more information about its future vision for the system.

Recommend the Legislature Consider Its Preferred Way Forward. Without prejudice to the administration’s long‑term plans, we recommend the Legislature consider the direction it would like to take the DDS system. Implementing rate reform—which has been an interest of the Legislature for the past few years—significantly exceeds the resources provided to DDS in the Governor’s budget. Doing so, however, would bring the DDS system into alignment with the vision of the Lanterman Act. If that were the chosen direction, the Legislature could consider repurposing the resources included in the Governor’s proposal for performance incentives to begin addressing some of the most problematic elements of the current system and develop a path forward to fully implement rate reform over time. The box below offers options for 2020‑21 to begin that process. (If the Legislature chooses this direction, we recommend requiring DDS to develop a multiyear rate reform implementation plan, which could include later implementation of a performance‑incentive program.) Alternatively, the Legislature may choose a different path forward. In that case, we recommend the Legislature begin to consider ways to change the system based on the Legislature’s priorities and available resources.

Options for Repurposed Funding

The Legislature could choose to repurpose the $60 million General Fund proposed for performance incentives (or another funding amount) for one or more of the following uses.

Begin to Implement Rate Study Recommendations. Last spring, we offered some ways to incrementally roll out rate models. The Legislature could opt for one of these options—or another option—to phase in rate models, beginning in 2020‑21.

Increase Supplemental Service Provider Rates. Alternatively, or in combination with the first example, the Legislature could increase supplemental provider rates or provide supplemental rate increases in additional service categories.

Increase RC Operations Funding to Improve Caseload Ratios. The Legislature could provide Regional Centers (RCs) with additional funding to improve caseload ratios. This not only would increase compliance with the state’s federal Medicaid waiver agreement and protect against the loss of federal funding, but also it would give service coordinators more time to deliver services to consumers in a person‑centered way.

Have the Administration Lead an Effort to Improve Data Systems and Data Integrity. This idea may be somewhat similar to what the Governor intended for the first year’s use of performance‑incentive funding, but we also would recommend redesigning RCs’ case management information technology systems to facilitate reporting and analysis on service gaps, consumer preferences, and consumer outcomes.

Consider Other Ways to Improve Quality. The Legislature could consider ways to use existing allocations for employment incentives, paid internships, reducing disparities, complying with federal rules, and developing community‑based resources (noted earlier) to test performance‑incentive strategies. We suggest the Legislature ask the Department of Developmental Services for ways it could redesign the structure of these allocations to build in accountability and quality measures and use some of the funding to test the use of performance incentives.

New Supplemental Provider Rates

Background

Draft Rate Study Results Informed Supplemental Rate Increases in 2019‑20. The 2019‑20 enacted budget included $206 million ($125 million General Fund) for supplemental rate increases of up to 8.2 percent to the service categories shown in Figure 8. The rate increases apply to services that make up the majority of POS spending. (The full‑year cost of these increases in 2020‑21 is $413 million [$250 million General Fund].)

Figure 8

Department of Developmental Services

Supplemental Rate Increases, Effective January 1, 2020

|

Service Code and Service |

Rate Increase |

|

017 ‑ Crisis Team—Evaluation and Behavior Modification |

8.20% |

|

025 ‑ Tutor Services—Group |

8.20 |

|

028 ‑ Socialization Training Program |

8.20 |

|

048 ‑ Client/Parent Support Behavior Intervention Training |

8.20 |

|

055 ‑ Community Integration Training Program |

8.20 |

|

062 ‑ Personal Assistance |

8.20 |

|

063 ‑ Community Activities Support Services |

8.20 |

|

091 ‑ In‑Home/Mobile Day Program |

8.20 |

|

093 ‑ Parent‑Coordinated Personal Assist Service |

8.20 |

|

094 ‑ Creative Arts Program |

8.20 |

|

108 ‑ Parenting Support Services |

8.20 |

|

109 ‑ Program Support Group—Residential |

8.20 |

|

110 ‑ Program Support Group—Day Service |

8.20 |

|

111 ‑ Program Support Group—Other Services |

8.20 |

|

113 ‑ DSS Licensed‑Specialized Residential Facility |

8.20 |

|

420 ‑ Voucher Respite |

8.20 |

|

465 ‑ Participant‑Directed Respite Services |

8.20 |

|

475 ‑ Participant Directed Community‑Based Training Services/Adults |

8.20 |

|

510 ‑ Adult Development Center |

8.20 |

|

515 ‑ Behavior Management Program |

8.20 |

|

612 ‑ Behavior Analyst |

8.20 |

|

613 ‑ Associate Behavior Analyst |

8.20 |

|

615 ‑ Behavior Management Assistant |

8.20 |

|

616 ‑ Behavior Technician—Paraprofessional |

8.20 |

|

645 ‑ Mobility Training Services Agency |

8.20 |

|

650 ‑ Mobility Training Service Specialist |

8.20 |

|

860 ‑ Homemaker Services |

8.20 |

|

862 ‑ In‑Home Respite Services Agency |

8.20 |

|

864 ‑ In‑Home Respite Worker |

8.20 |

|

875 ‑ Transportation Company |

8.20 |

|

880 ‑ Transportation‑Additional Component |

8.20 |

|

882 ‑ Transportation‑Assistant |

8.20 |

|

896 ‑ Supported Living Services |

8.20 |

|

904 ‑ Family Home Agency |

8.20 |

|

905 ‑ Residential Facility Serving Adults—Owner Operated |

8.20 |

|

910 ‑ Residential Facility Serving Children—Owner Operated |

8.20 |

|

915 ‑ Residential Facility Serving Adults—Staff Operated |

8.20 |

|

920 ‑ Residential Facility Serving Children—Staff Operated |

8.20 |

|

950 ‑ Supported Employment—Group |

8.20 |

|

952 ‑ Supported Employment—Individual |

7.60 |

|

073 ‑ Parent Coordinator Supported Living Program |

6.30 |

|

605 ‑ Adaptive Skills Trainer |

3.90 |

|

635 ‑ Independent Living Specialist |

2.40 |

|

DSS = Department of Social Services. |

|

The Legislature and the administration used the draft rate study (released in March 2019) to determine which service categories to increase within the budgeted amount of $206 million ($125 million General Fund). The 2019‑20 budget included the suspension of these services in December 2021 unless the anticipated amount of General Fund revenues met a certain threshold.

Several Services Were Not Given Rate Increases in 2019‑20. Among the services that were not given a supplemental rate increase were independent living services, infant development services, and Early Start therapeutic services. The draft rate study models had indicated that the existing rates for these services were sufficient in the near term. As described below, however, updated rate models indicated they were not.

Under Federal Reimbursement Rules, DDS Must Seek Federal Approval of Rate Increases. To receive federal Medicaid matching funds, DDS must seek federal approval of the supplemental rate increases. This approval process takes about six months for program changes like a rate increase. Because of this delay, the 2019‑20 budget provided half‑year funding in anticipation of the increases beginning January 1, 2020 (which they did).

Budget Proposal

Three Additional Services Would Be Included in Supplemental Rate Increases Approved by Legislature. The Governor’s budget proposes $18 million ($10.8 million General Fund) to add the three additional services noted above to the supplemental rate increases in 2020‑21. The funding represents half‑year costs. In 2021‑22, the estimated annual cost of these increases is $36 million ($21.6 million General Fund). Figure 9 notes each service and the percentage rate increase for each.

Figure 9

Proposal for Supplemental Rate Increases for

Three Additional Services, Effective January 1, 2021

|

Service Code and Service |

Rate Increase |

|

520 ‑ Independent Living Program |

8.20% |

|

805 ‑ Infant Development Program |

8.20 |

|

116 ‑ Early Start Specialized Therapeutic Services |

5.00 |

Rate Increases Would Take Effect January 1, 2021. For the added services, supplemental rate increases would not take effect until January 1, 2021, which would again provide the state six months to seek federal approval of these increases.

Rate Increases Would Potentially Be Suspended July 1, 2023. The supplemental rate increases approved in 2019‑20 and proposed in 2020‑21 would be suspended on July 1, 2023 unless General Fund revenues are anticipated to reach a certain threshold. This extends the original suspension date for the 2019‑20 increases by 18 months. (Currently, the administration assumes these suspensions take effect.)

LAO Assessment

Proposal Corrects Omission From 2019‑20 Supplemental Rate Increases. We had identified the three services targeted for rate increases in 2020‑21 as ones that had potential issues with their draft rate models. The results from the draft rate models had led to the omission of these services from the rate increase in 2019‑20. The Governor’s budget proposes to correct that omission based on revised rate model information. Again, the proposal does not implement rate models; rather the rate models—if they were fully implemented—indicate which services are most in need of a rate increase.

Built‑In Suspension of Rate Increases in 2023 Creates Uncertainty About Sustainability. As we noted in our analysis last year, the Governor’s proposed suspension of services that are arguably ongoing in nature creates uncertainty for consumers and service providers.

LAO Recommendation

Recommend Approving New Supplemental Rate Increases, Consistent With Legislative Action in 2019‑20. We recommend the Legislature approve the proposed supplemental rate increases for infant development, Early Start therapies, and independent living, consistent with the Legislature’s action approving supplemental rate increases in 2019‑20.

Enhanced Caseload Ratios for Children ages 3, 4, and 5

Background

Age 3 is an important milestone in the DDS system. Infants and toddlers who were part of the Early Start program are reassessed at age 3 to determine whether they have a substantial lifelong developmental disability. It also is the age at which young children may become eligible for services through the school system. Currently, required average caseload ratios at each RC for consumers ages 3 and older are 1:62 if they are enrolled in the Medicaid waiver or 1:66 if they are not enrolled in the Medicaid waiver.

Governor’s Proposal

Budget Proposes to Reduce Caseloads for Service Coordinators Working With Children Ages 3 Through 5. The Governor’s budget proposes $16.5 million ($11.2 million General Fund) to pay for additional service coordinators at RCs to lower the caseload ratio for young consumers ages 3 through 5 to one service coordinator for every 45 consumers (1:45). DDS cites the complexity parents face navigating the various systems at this point in their child’s life as justification for lowering the service coordinator caseload ratios. DDS also cites 1:45 caseload ratios in Early Start as the basis for selecting that particular ratio.

LAO Assessment

Proposal Does Not Target Existing Caseload Problems

While the Governor’s proposal to add extra support for the families of children ages 3 through 5 might have merit, it does not address some of the known problems with caseload ratios described below.

Early Start Caseload Ratios Well Over 1:45. The Governor’s budget bases its proposal for caseload ratios of 1:45 for children ages 3, 4, and 5 on the purported 1:45 caseload ratios in Early Start. Although statute sets Early Start caseload ratios at 1:62, DDS funds RCs for a preferred caseload ratio of 1:45. The salary assumptions in the funding formula DDS uses to determine how much to pay RCs to implement the preferred caseload ratios is very outdated, however. Consequently, an RC typically hires fewer service coordinators than it is “funded for” because it has to pay a higher salary than that provided in the formula. As a result, as of March 2019, all RCs had average Early Start caseload ratios exceeding 1:45 as shown in Figure 10. The average caseload ratio statewide was 1:65 and six RCs had average Early Start ratios in excess of 1:70.

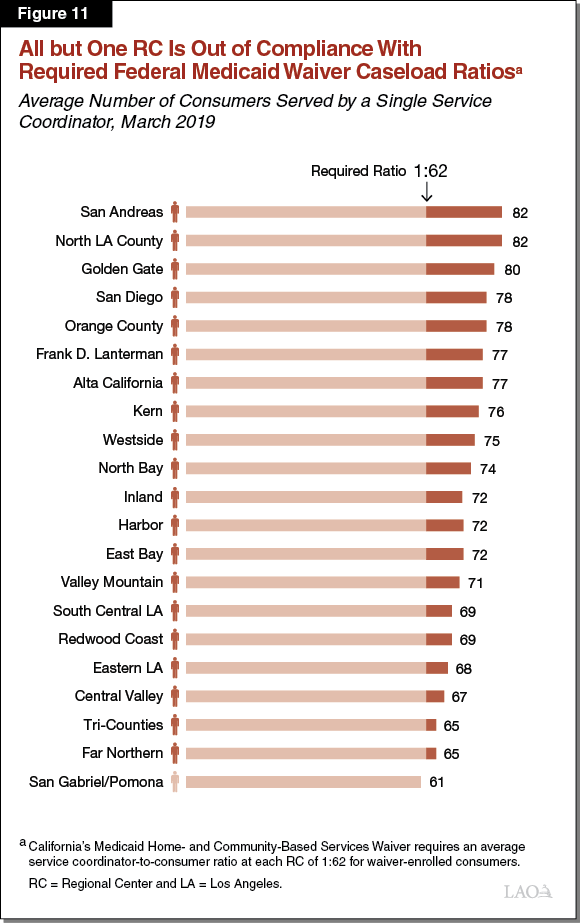

Current Federal Waiver Caseload Ratios Risk Loss of Federal Funding. In addition to problems with the Early Start caseload ratios, RC service coordinators also carry large caseloads for consumers age 3 and older enrolled in the Medicaid waiver. While statute and federal agreements require average caseload ratios of 1:62 at each RC, as of March 2019, only one RC was in compliance as shown in Figure 11. The average caseload statewide was 73 and nine RCs had average caseload ratios of 1:75 or higher.

Medicaid waiver caseload ratios have been out of compliance for multiple years. Although the federal government has not taken any action against California as of yet, these out‑of‑compliance ratios nonetheless put federal funding at risk, particularly given the state’s experience in the 1990s. Specifically, in 1997, the federal government found that RCs had numerous quality problems. In response, the federal government froze enrollment in the Medicaid waiver program until RCs implemented agreed‑upon changes, which meant that the state could not access federal matching funds for services provided to consumers who would have otherwise been new waiver enrollees. When the freeze was finally fully lifted several years later, DDS estimated the state had foregone nearly $1 billion in federal funding. At that time, the federal government and California agreed to limit the size of caseloads as one way to avoid compromising the quality of RC services.

Service Coordination Needs May Differ Across RCs

Without prejudice to its merits, the Governor’s proposal lacks sufficient analytic basis to determine where or for whom caseload relief is warranted. Instead, it assumes that all RCs need to provide more intensive service coordination to families of children ages 3 through 5. While we agree those ages include important milestones and could benefit from extra support, why this is necessarily the case at all RCs is unclear, given some RCs might need extra support elsewhere. For example, age 22 is another important milestone in the system—it is when consumers age out of the school system and begin to access adult services from RCs. Transition planning at schools begins at age 16. Arguably, consumers in this transitional age range and their families also could use added attention from their service coordinators. Given that more than 90 percent of DDS consumers are served by RCs that are out of compliance with caseload ratios, we to question why the proposal is limited to ages 3 through 5.

LAO Recommendations

We withhold recommendation on the proposal for enhanced caseload ratios for children ages 3, 4, and 5. In light of the fact that most consumers are assigned to service coordinators who have very large caseload ratios (and that all RCs are out of compliance in at least one service category), we would need more information to justify approval of this request to enhance caseload ratios for such a limited age group. In addition, the program—Early Start—that serves as the model for this caseload ratio of 1:45 does not have a single RC with average caseloads that small. Consequently, the rationale for targeting caseloads for this age group before targeting Early Start caseloads is unclear.

Recommend the Legislature Ask DDS to Report on the Following Issues at Budget Hearings. We recommend the Legislature request additional information from DDS at budget subcommittee hearings this spring to inform its deliberations on this component of the Governor’s proposal:

- What is the department’s plan to address other caseload ratios that are out of compliance?

- Is the department concerned about the possibility of losing federal funding because of out‑of‑compliance caseload ratios for consumers enrolled in the Medicaid waiver program?

- For each RC, are children ages 3, 4, and 5 the group for which service coordination needs are the greatest?

- What is the department’s plan to improve Early Start caseload ratios?

Recommend Requiring DDS to Provide Updated Caseload Ratio Information in March. Each year, statute requires RCs to report caseload information to DDS. The final reporting is complete in March, but is not always made available publicly in a timely way. We recommend the Legislature direct DDS to provide this information to the budget subcommittees and the LAO in March to better inform budget decisions that will be made this year.

Safety Net Plan

Background

Closure of DCs Led to Need for Community‑Based Safety Net. As DDS closed its last general treatment DCs, it simultaneously developed community‑based services for individuals in crisis. (Previously, DCs served as a backstop and safety net for individuals needing crisis services.) Such safety net services—which provide temporary residential, medical, and behavioral intervention—range from mobile crisis teams to acute crisis homes to “step‑down” homes and services for individuals moving from more restrictive settings, such as institutions for mental disease or PDC’s Secure Treatment Program.

DDS Submitted a Safety Net Plan in May 2017. The previous Governor’s plan to close DCs was approved by the Legislature in 2015. Subsequent legislation required DDS to submit a safety net and crisis plan with the Governor’s revised budget in May 2017. Many, but not all, of DDS’ recent and current activities related to safety net services were described in that plan.

Legislation Associated With the 2019‑20 Budget Required DDS to Submit a Revised Plan in January 2020. Last year, we recommended the Legislature require DDS to submit a revised plan in part because each budget proposal since the May 2017 plan was released has included new proposals (that were not identified in the original plan) to expand the safety net. Assessing whether these new additions were necessary or sufficient became difficult because there was little insight into how the department decided to request additional funds. We recommended that DDS submit a new plan that would include information about how the department is planning for the future, how it makes its decisions to add new resources, how it will increase the capacity of the system to prevent crises from happening, and whether consumers need greater access to ongoing mental health and behavioral health services. Although our recommendation was not taken up in all aspects, DDS was directed by the Legislature to submit a revised plan along with the Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposal.

DDS Budget Proposals to Expand the Safety Net

Revised Safety Net Plan

DDS released its revised safety net plan on January 10. It includes an update on previous initiatives, describes how it engaged stakeholders to develop the plan, discusses recent initiatives, and describes the new proposals in the Governor’s budget (summarized below).

Additional PDC Capacity, EBSH Homes, and Crisis Prevention Training

Temporary Additional Capacity of 20 Beds at PDC . . . The Governor’s budget proposes $8.9 million General Fund to temporarily add one intermediate care facility (ICF) unit of 20 beds at PDC (for a total of 231 beds at PDC). The 20 beds would not be available after June 30, 2024. The Governor’s budget indicated the purpose of the additional beds, which would increase the statutory cap of 211 beds at PDC to 231, is to provide temporary additional capacity for individuals with developmental disabilities who have been deemed IST and are currently in county jails awaiting admission to PDC.

. . . In Combination With Development of Five Additional Community‑Based Homes to Serve Individuals Previously at PDC. The Governor’s budget proposes $7.5 million General Fund for DDS to develop five additional EBSHs with delayed egress and secured perimeter. These homes would serve individuals at PDC who are deemed a danger to themselves or others, which would make more room at PDC for those accused of committing a crime and deemed IST. DDS estimates all five homes would be up and running by July 2024 when the temporary ICF unit at PDC would cease being available.

Additional Crisis Training at Four RCs. The Governor’s budget includes $4.5 million ($2.6 million General Fund) to expand crisis prevention training and education at four additional RCs (training and education currently are being pilot‑tested at two RCs). The particular program is called Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment, Resources, and Treatment (START). It was developed in 1988 at the University of New Hampshire to serve the unique needs of individuals with developmental disabilities and co‑occurring mental or behavioral health challenges. Among other things, it provides training to local START teams (which are selected and contracted by the RC) on whole person assessment, community education, and data collection and management. These teams facilitate 24‑hour care coordination and provide coaching and education to families, staff, and service providers.

LAO Assessment

Revised Safety Net Plan

The Safety Net Plan Provides Important Information About Efforts Thus Far. DDS’ revised safety net plan provides important status updates about past and current safety net development and operation and it describes the 2020‑21 proposals to expand the safety net. It also describes the changing demographics and composition of the DDS consumer population, which provides important context (particularly about the increasing share of individuals with autism) about the need for safety net services.

The Safety Net Plan Provides Less Detail About Longer‑Term Plans. Although the plan provides important information about current and past efforts and describes the new proposals for 2020‑21, it provides little information about efforts beyond 2020‑21. Because the plan is more like a status update, assessing whether the department is conducting the right amount of preparation for the future is difficult. For example, the plan provides good data about the growth in the number of consumers diagnosed with autism or intellectual disabilities, but it does not address what the department anticipates having to do to in terms of safety net planning to adequately serve these consumers in the future.

The Plan Does Not Provide Much Detail About How DDS Prioritizes Safety Net Spending. DDS compiles certain data and information about the safety net, such as how many consumers were placed in restrictive settings like jails and for how long, the characteristics of consumers with complex needs, and ongoing housing development. What is less clear is how DDS uses that information to determine which projects to prioritize in a given year, anticipate future need, and project caseloads and spending associated with meeting those needs.

Focus on Prevention Is a Good Approach. The focus on training of local teams to prevent and respond to crises by educating and coaching family, staff, and providers could potentially reduce the number of full‑blown crises. This would be better for the consumer and the consumer’s family and service providers. Moreover, crises can be costly events. Crises often result in consumers having to move from their current residence to a temporary crisis home or a restrictive setting like an institution for mental disease, the latter of which is ineligible for federal funding. Consequently, reducing the frequency of consumer crises could reduce state costs.

Additional PDC Capacity, EBSH Homes, and Crises Prevention Training

DDS Provided Information to Demonstrate Need for Additional Capacity. DDS used information about the number of consumers in county jails awaiting admission to PDC (which is currently at capacity) as the basis for proposing to add 20 temporary beds at PDC and develop five EBSHs in the community (which could each serve up to four people). The PDC resources would be available for individuals who have been found IST and need competency training. PDC is likely a more appropriate placement for an individual with developmental disabilities than county jails. The EBSH homes would serve individuals at PDC who are deemed a danger to themselves or others. Moving those individuals into EBSH would make room at PDC for the IST population needs.

Restrictive Nature of Proposed Community‑Based Homes Means the Governor’s Proposal Should Be Considered With Caution. Although it appears the additional EBSH capacity is warranted, it is worth noting that increasing the number of EBSHs that include delayed egress and a secured perimeter deviates from current statute. Currently, EBSHs with delayed egress and secured perimeter are written into statute as a pilot program that ends January 1, 2021. The pilot only allowed six of these homes to be built and for only one to be developed in a given year. The current proposal would increase the cap to 11 homes and remove language about only developing one of these homes per year. The reason for the original limitations is that EBSHs with delayed egress and secured perimeter are considered more restrictive settings and are not eligible for federal matching funds. Since approving the planned closure of DCs, the Legislature has approached proposals to expand the use of restrictive settings in the community with caution given the potential implications for the individual. Although the Legislature may determine this particular expansion is warranted, making these decisions deliberately and conducting ongoing oversight of DDS to ensure these settings are not being overused is important.

While START Pilot Is Not Complete . . . Pilot‑testing of START services at San Andreas and San Diego RCs is not yet complete and no reports are available yet about the implementation and progress.

. . . Crisis Training, as Proposed, Is Justified. Typically, government agencies wait for the results of pilot programs before deciding whether the pilots were successful enough to scale the programs up and replicate them in other areas. In this case, DDS may be justified in moving forward before the pilot testing is complete. As we noted in our analysis last year, moving the system more toward prevention of crises and away from having to respond to crises is important. The START program—which has been used and evaluated in other states and requires data collection as a requisite activity—trains families and providers on ways to prevent and respond to potential crises and link them to local resources, such as first responders. Which RCs will be selected for START services is still unknown.

LAO Recommendations

Revised Safety Net Plan

Consider Requesting More Information About Future Planning and Decision‑Making Process. Although the safety net plan submitted by DDS includes important status updates and descriptions of programs and changing consumer demographics, it still lacks information about future‑looking strategies and the methodology DDS uses to determine imminent and future needs. We recommend the Legislature continue to press DDS at hearings, if not in another formal update, to provide additional information about its strategic planning process to inform the Legislature’s assessment of the Governor’s safety net spending priorities in the current and future budget proposals.

Additional Capacity and Homes

Recommend Approving Additional PDC Capacity and Homes. The proposed temporary additional capacity at PDC coupled with the development of new EBSH homes with delayed egress and secured perimeter makes sense for serving consumers in jail awaiting admission to PDC. We recommend the Legislature approve this component of the safety net proposal and request regular updates about the use of and demand for these kinds of services.

Recommend Approving Increase for START Training. While we recommend the Legislature ask DDS at budget subcommittee hearings about which RCs would be selected for START services and why, we recommend approval of funding to increase START training on crisis prevention and intervention in concept. We recommend the Legislature request regular updates on these training efforts, including reports of available data.

Conclusion

The most significant new proposal in the Governor’s DDS budget is the performance‑incentive program. It represents a new direction for developmental services without addressing existing challenges in the current system. Without addressing these challenges, the proposal is unlikely to succeed. We therefore recommend rejecting this proposal. The Legislature, meanwhile, should consider the way forward given these challenges. Does it want to use the rate study to design a path forward that could lead to the right conditions for a performance‑based accountability system in the future? Or, does it want to consider an alternative path that changes the system to address future service demands given budget constraints?