LAO Contact

February 11, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget:

Analysis of the Department of State Hospitals Budget

- Overview

- Community Care Collaborative Pilot

- Treatment Team and Primary Care Staffing Proposal

- Protective Services Staffing Proposal

Summary

The Governor’s budget proposes $2.3 billion for the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) in 2020‑21—an increase of $232 million (11 percent) from the revised 2019‑20 level. In this report, we assess three specific DSH proposals and offer recommendations for legislative consideration.

Community Care Collaborative Pilot. The Governor’s budget proposes a pilot program intended to help alleviate the rising number of incompetent to stand trial (IST) designations and referrals to the state hospital system and requests $24.6 million (General Fund) and 3 positions to implement this program in 2020‑21. (The total cost of the six‑year pilot is estimated to be $364.2 million General Fund.) Under this pilot, DSH would provide funding to counties for competency restoration treatment in the community, as well as incentive payments for counties to invest in strategies to reduce the level of IST designations. We recommend that the Legislature direct DSH to report back at upcoming budget hearings on issues we raise related to the efficacy and governance of this pilot. To the extent the Legislature chooses to move forward with this proposal, we recommend that it adopt legislation that (1) clarifies the target population of the pilot program, (2) includes a robust evaluation component for the pilot program, (3) strengthens fiscal oversight of the pilot, (4) requires the use of counties’ previous‑year level of IST referrals as the baseline to measure progress, and (5) ensures that the funding given to counties under this pilot does not supplant funding for existing programs.

Treatment Team and Primary Care Staffing. The Governor’s budget proposes several changes to the way treatment teams and primary care units are staffed at state hospitals, and requests $32 million (General Fund) and 80.9 positions to implement these changes in 2020‑21. These amounts would ramp up to $64.2 million (General Fund) and 250.2 positions by 2024‑25, and be ongoing thereafter at these amounts. While we recommend the Legislature approve the proposed standardization of the treatment team and primary care caseload ratios that would apply across all state hospitals, we recommend that the Legislature direct DSH to report at budget hearings on its ability to fill proposed psychiatrist positions. We also recommend that the Legislature direct DSH to report with an assessment of the degree to which nurse practitioners can be staffed in primary care units. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature approve the trauma treatment specialist positions and discharge strike teams on a pilot basis. The pilot can be used to determine whether these requested positions are effective at developing services tailored toward patients who have experienced significant trauma in their lives, or improving patient placement in community settings after discharge.

Protective Services Staffing. The Governor’s budget proposes several changes to the way protective services are staffed at state hospitals, and requests $7.9 million (General Fund) and 46.3 positions to implement these changes at Napa State Hospital only. We recommend the Legislature approve the proposed standardization of protective services staffing levels, but require DSH to provide information on the cost of implementing the new staffing levels at all state hospitals, which is unknown at this time.

Overview

Department Provides Inpatient and Outpatient Mental Health Services to Forensic and Civil Commitments. The Department of State Hospitals (DSH) provides inpatient mental health services at five state hospitals (Atascadero, Coalinga, Metropolitan‑Los Angeles, Napa, and Patton). DSH also contracts with counties to provide in‑patient mental health services in additional locations (typically county jails) throughout the state. In addition, DSH provides outpatient treatment services to patients in the community. The 2019‑20 budget included resources to provide in‑patient mental health services to about 6,200 individuals in state hospitals and roughly 400 individuals in contracted programs. The budget also included resources to provide out‑patient services to around 700 individuals. Patients fall into one of two categories: civil commitments or forensic commitments. Civil commitments generally are referred to the state hospitals for treatment by counties. Forensic commitments typically are committed by the criminal justice system and include individuals classified as incompetent to stand trial (IST), not guilty by reason of insanity, mentally disordered offenders, or sexually violent predators. Currently, about 90 percent of the patient population is forensic in nature. As of January 14, 2020, the department had about 1,200 patients awaiting placement, including about 800 IST patients.

Operational Spending Proposed to Increase by $232 Million in 2020‑21. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of about $2.3 billion ($2.1 billion from the General Fund) for DSH operations in 2020‑21. This represents an increase of $232 million (11 percent) from the revised 2019‑20 level. The department’s budget includes increased funding for several proposals, including a pilot program to reduce the number of IST designations and referrals to the state hospital system and staffing adjustments resulting from DSH’s Clinical Staffing Study, both of which we discuss in greater detail below.

Community Care Collaborative Pilot

Background

IST Designations and Referrals. Under state and federal law, all individuals who face criminal charges must be mentally competent to help in their defense. By definition, an individual who is designated by the court as IST lacks the mental competency required to participate in court proceedings. (Typically, the IST designation process is initiated by defense attorneys reporting their concerns about their clients’ mental capacity to the judge. The judge then orders an initial evaluation and a competency hearing.) Individuals who are IST and face a felony charge typically are referred by a state trial court to DSH to receive competency restoration treatment that, if successful, results in the individual returning to the court system to face the felony criminal charges levied against them. (Individuals found IST facing misdemeanor charges typically receive treatment in county jails or other county‑run programs.) Not all patients have their competency restored, meaning that they may reside in the DSH system longer or may be transferred to another system to continue receiving mental health services.

The IST Waitlist. Once DSH receives a referral for an IST patient, the patient is put on a pending transfer list (commonly referred to by the department as the “IST waitlist”). Patients are removed from the waitlist when they are physically transferred to a treatment program. Patients on the waitlist are typically housed in county jails while they wait to be transferred to a DSH program, which is problematic for two reasons. First, due to limited access to mental health treatment in some jails, these patients’ condition can worsen while they are in jail, potentially making eventual restoration of competency more difficult. Second, long waitlists can result in increased court costs and a higher risk of DSH being found in contempt of court orders to admit patients.

DSH Efforts to Increase Capacity for IST Treatment. In recent years, funding was provided to DSH to increase capacity for competency restoration treatment. This includes expanding the number of IST treatment beds and staff within state hospitals, as well as expanding capacity for Jail‑Based Competency Treatment (JBCT) programs. Under the JBCT program, counties provide competency restoration treatment in county jails to patients who do not require the intensive level of inpatient treatment provided in state hospitals. In addition, ongoing funding was provided beginning in 2018‑19 for a Community‑Based Restoration (CBR) program in Los Angeles County. Under the CBR model, competency restoration treatment is provided to IST patients in county mental health facilities outside of a jail setting.

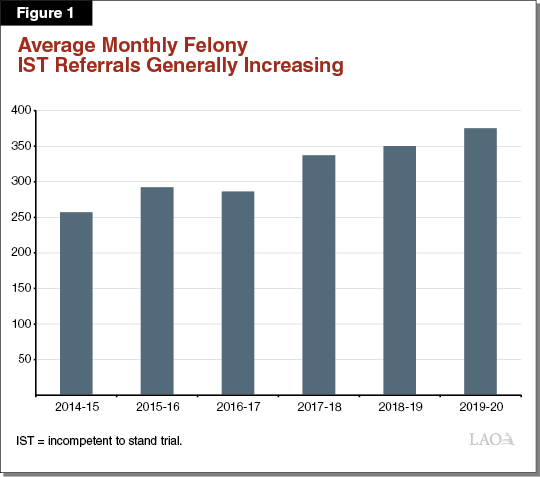

IST Waitlist Is Now Steady, But IST Referrals Continue to Increase. From 2013 to 2018, the average monthly IST waitlist increased from roughly 350 patients to over 800 patients, an average annual increase of close to 20 percent. However, as of 2019 it has leveled off at around 800 individuals. This likely is due to increased capacity for competency restoration treatment that has been funded in recent years, such as expanding the number of JBCT beds. Despite the IST waitlist leveling off, the number of IST referrals to DSH (which includes referrals to JBCT programs) generally has increased. This trend is shown in Figure 1.

While funding was provided to DSH to increase capacity to treat IST referrals through competency restoration, this increased capacity has not kept up with the increasing rate at which IST patients are being referred to DSH. The factors that contribute to the growing IST referral rate cannot be addressed by competency restoration treatment alone, as competency restoration treatment only is provided to individuals who have already been designated as IST. In response to its increasing IST referral rate, DSH has received funding to implement an IST “diversion” program. We describe the concept of diversion in the nearby box.

Diversion

Diversion generally narrowly refers to the process of the courts referring offenders with a mental health condition to treatment programs as an alternative to incarceration. Diversion programs often include a corresponding possibility of dropped charges should the offender complete their court‑ordered treatment program.

However, diversion also can have a broader interpretation—referring to the process of investing in community mental health services pre‑arrest or post‑release from jail, to either (1) help prevent individuals with a mental health condition from being arrested in the first place or (2) provide services so that individuals with a mental health condition are not rearrested after they are released from prison.

DSH Diversion Program. To address the increasing number of felony IST referrals to DSH, DSH received one‑time funding in 2018‑19 to contract with counties for three years to establish IST diversion programs that are intended primarily to treat offenders before they are declared IST. The diversion programs target individuals who have been arrested for a felony offense, have a mental health condition that could render them IST, and are a low public safety risk. Under this program, courts have the authority to refer individuals who meet these criteria to the county IST diversion programs. If such individuals successfully complete these programs, judges could drop or reduce their charges. This diversion program reflects the narrower interpretation of diversion previously discussed.

Governor’s Proposal

The administration proposes a two‑pronged pilot program known as the Community Care Collaborative Pilot (CCCP) to provide funding to counties for CBR treatment and incentivize counties to invest in strategies to reduce the overall number of felony IST designations and referrals to DSH. This six‑year pilot program would be implemented in three counties that have high IST referral rates to DSH. (The administration has not identified which counties would participate in the pilot. We understand that the administration is in discussions to identify which counties these would be.)

The pilot program is composed of three funding components: (1) “progress payments” to counties for CBR treatment modeled after the CBR program in Los Angeles County that was funded by DSH in 2018‑19, (2) “incentive payments” to counties for reducing felony IST designations and referrals by investing in both pre‑arrest and post‑release from jail strategies, and (3) application‑based start‑up funds (available in each year of the pilot) for either up‑front CBR program costs or strategies to reduce IST designations. In total, the Governor’s budget includes $24.6 million General Fund in 2020‑21 to implement this pilot program, and the total cost to the General Fund over the six‑year pilot would be $364.2 million. We describe this proposal in greater detail below.

DSH Would Pay for CBR Treatment Through Progress Payments to Counties. The first component of the CCCP proposal is funding from DSH for CBR treatment. Specifically, DSH would pay $60,225 for each felony IST served by counties in a CBR treatment program. Funding would be capped at counties’ benchmark reduction goal (described in the next paragraph). The funding amount is based on a $165 per day rate, and would be increased by 3 percent each year of the pilot to account for increases in local service costs. The proposal reserves $14.3 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 for the progress payments component. If counties treat fewer felony ISTs than the number that has been set as their benchmark reduction goal, any remaining funds will be rolled over into the incentive payments component of the CCCP, which we describe below.

Incentive Payments Based on Meeting Felony IST Designation and Referral Benchmark Reduction Goals. The second component of the pilot would provide incentive payments to counties for reducing felony IST designations and referrals based on set goals. Specifically, counties’ benchmark reduction goals in felony IST designations and referrals would be set at 15 percent of their total felony IST referrals in 2018‑19. The proposal reserves $7.9 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 for the incentive payments component. The benchmark reduction goals increase over time but would be consistently measured against counties’ total 2018‑19 felony IST referrals as the baseline. We describe how counties could make progress toward these goals below.

Counties Would Be Required to Submit Plans Before Receiving Start‑Up Funds. Under the CCCP, counties would be required to submit a plan to DSH outlining how they plan to achieve reduction goals for felony IST designations and referrals. The plans also would be required to outline how counties plan to use their incentive payments to invest in community mental health services, and describe how other funding sources would be used to support the pilot. The proposal reserves $1.4 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 for start‑up funds.

How Counties Could Make Progress Toward Benchmark Reduction Goals. Counties could make progress toward their benchmark reduction goals by treating felony ISTs in CBR programs so that they are not referred to DSH. They also could make progress by implementing upstream efforts to provide county services to individuals with mental health conditions before they are arrested (these could include crisis response centers, diversion training programs for law enforcement, or mental health training programs for 911 dispatchers). Finally, they could make progress by implementing downstream efforts to provide county services to individuals with mental health conditions after they are released from jail to prevent being rearrested (these could include housing assistance, ongoing behavioral health treatment, or employment services).

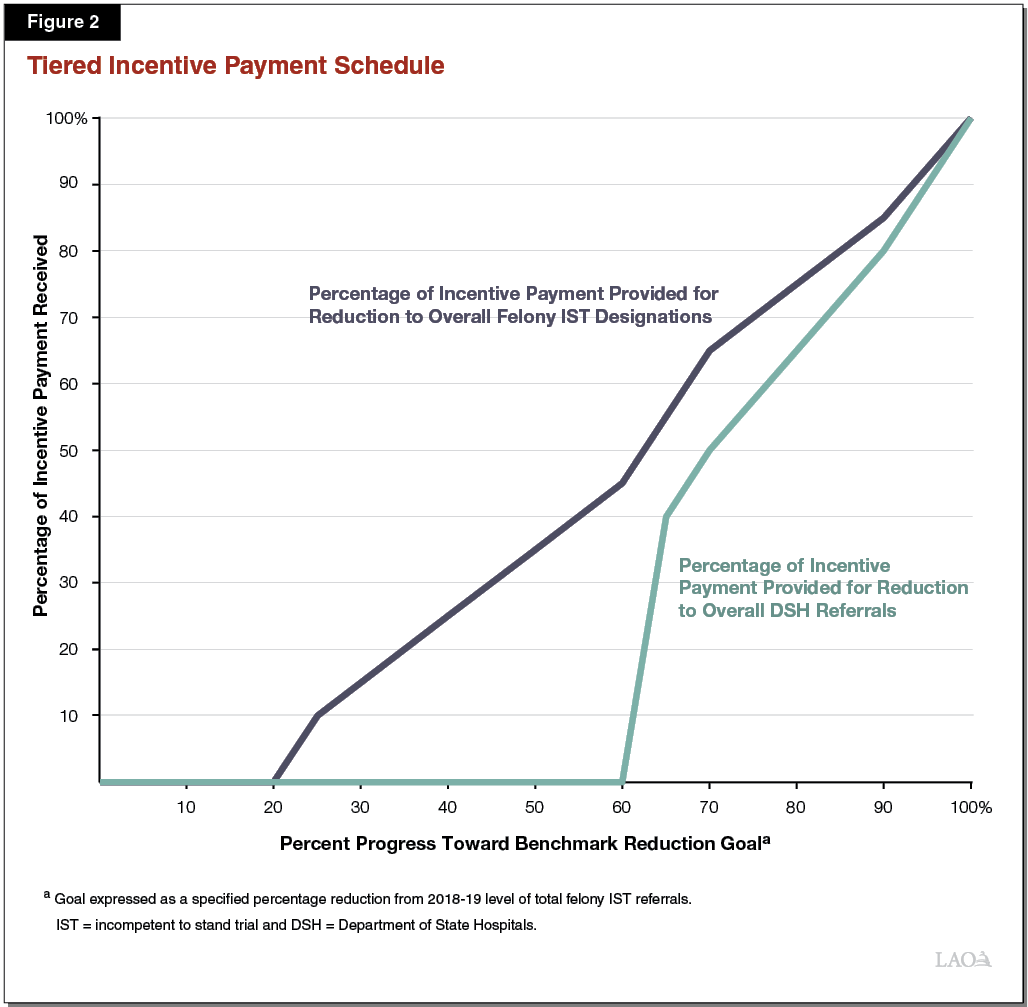

The incentive payments available to counties would be “tiered,” meaning counties would not have to fully meet their benchmark reduction goals in felony IST designations and referrals in order to be eligible for incentive payments. If counties partially meet their benchmark reduction goals, they would receive a percentage of the total amount available for incentive payments. As seen in Figure 2, counties would be eligible for these partial payments starting at 25 percent of their benchmark reduction goals for felony IST referrals, and starting at 65 percent of their benchmark reduction goals for felony IST designations. After counties meet each of these minimum thresholds for progress toward their benchmark reduction goals, the amount they could receive increases the closer they get to their overall benchmark reduction goals.

Given reducing IST designation is more difficult than reducing referrals to DSH (given the option to treat individuals in CBR programs), the incentive payments for designation reductions begin earlier. If counties meet their benchmark reduction goals for felony IST designations, they will receive a further incentive payment equal to 15 percent of the total amount allotted for the progress payments component of the pilot.

Governor’s Proposal Emphasizes Community Mental Health and Other Diversion Strategies to Prevent Further Felony ISTs. In the CCCP proposal, DSH argues that the most effective way to address the increasing number of IST designations is to invest in “upstream” county services (that are able to assist individuals with mental health conditions at risk of becoming a felony IST before they are arrested) or “downstream” county services (that are able to connect individuals with these services when they are released from jail, so that they are not designated as a felony IST again). DSH supports this strategy using evidence from its review of felony IST arrest histories. Specifically, DSH found that in 2014‑15, 45 percent of its felony ISTs had 15 or more previous arrests. It also found that in 2014‑15, 69 percent of felony ISTs were rearrested and about 50 percent were convicted of new crimes.

Comparison to Current DSH Diversion Program. While the existing diversion program also aims to reduce IST designations, the new pilot proposal has some key differences from the existing program. Under the current DSH diversion program, counties agree to serve a set amount of individuals over three years, typically set at 20 percent to 30 percent of counties’ total felony IST referrals to DSH in 2016‑17. In addition, under the current DSH diversion program, counties are required to divert individuals with a mental health condition who have already been arrested before their trial. Under the CCCP, in contrast, incentive payments could be used to divert individuals pre‑arrest or post‑release from jail, reflecting the broader interpretation of diversion. The current DSH diversion program also includes a requirement to drop charges if a client completes the diversion program successfully. The CCCP does not include this requirement. Finally, the current DSH diversion program also is limited to only serving individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder. Under the CCCP proposal, the list of eligible diagnoses is expanded to include a broader set of mental health conditions including post‑traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder.

Proposal Encourages Counties to Use These Funds to Leverage Additional Funding Sources for This Pilot. Under the CCCP, counties would be encouraged to access other funding sources (such as Medi‑Cal reimbursement) to support community placement and services. Counties would be required to report which funding sources they utilize to support the CCCP to DSH.

Outcomes Reporting. Under this proposal, counties would be required to report how they spent funds received through CCCP to DSH. This would include what specific programs or services the CCCP funds were used for. DSH also requests resources to conduct evaluation of the CCCP, but little detail is provided on what lessons are intended to be learned from the pilot, or how the evaluation framework would be structured.

LAO Assessment

Proposal Raises Issues for Legislative Consideration Related to Efficacy and Governance

Effectiveness of LA County Competency Restoration Program Is Uncertain. The CBR portion of the CCCP is modeled after the CBR program funded beginning in 2018‑19 in Los Angeles County. Considering expansion of CBR treatment has merit given (1) the rate of IST designation and referral growth and (2) competency restoration services are cheaper to provide in community settings than in state hospitals. However, there has not been enough time to evaluate the effectiveness of the program in Los Angeles County. Consequently, expansion of this CBR program may be premature, as could be basing incentive payments on the Los Angeles model.

Increasing Community Mental Health and Other County Diversion Strategies Merits Consideration . . . Given the increasing number of felony IST designations and referrals, considering methods to prevent individuals from becoming IST is worthwhile. We note that the upstream and downstream services that the administration describes in this proposal seem like reasonable ways to provide services to individuals with mental health conditions who may be at risk of being designated a felony IST.

. . . But Adding Another Funding Entity for Community Mental Health May Create Program Coordination and Oversight Issues. The CCCP would add complexity to the broader community mental health system in three ways.

- Addition of Another State Entity Complicates Oversight. The state has long‑standing issues with fiscal and programmatic oversight of county delivery of mental health services. Part of this difficulty is due to the currently fragmented oversight system, split between the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission. This proposal creates further fragmentation by adding DSH as a third state entity with a role in overseeing community mental health funds, an area over which DSH has little experience.

- Coordination Issues Arising From Addition of New County Actors. This proposal potentially adds other actors to county delivery of mental health services. The CCCP would require significant coordination across multiple programs to provide upstream and downstream services for people with mental health conditions that may render them IST. These programs could be administered by local entities other than county mental health departments including, but not limited to, county departments of public health, county public guardians, or county public defenders. This raises the possibility of coordination issues among multiple program efforts that could lead to inefficiencies and poorer overall results.

- Additional Funding Stream Adds to Complexity. The CCCP would add another funding stream to the community mental health funding system that is already confusing. This system is composed of several different funding streams, including (1) federal funds, (2) county realignment funds, (3) Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) funds, (4) state General Fund from DHCS, and (5) additional county funds. This proposal would add funding from DSH to this system, potentially making it more complex and confusing to track the use of funds in the system.

Proposal Also Raises Issues Related to Program Structure

Hard to Define Target Population for Incentive Payments Component. The incentive payments component of the CCCP is meant to provide mental health services to individuals who are at risk of becoming IST. In practice, this population is very difficult to identify and without more explicit criteria for determining which individuals will receive services, the incentive payments given to counties by DSH might be indistinguishable from existing county funding sources for community mental health. Counties being unable to direct funding toward services for a more specific target population could dilute the effectiveness of this pilot.

Potential Supplanting of Funding for Existing County Mental Health Programs. Under the CCCP, counties would be given the flexibility to use the incentive funding received through the pilot for programs that they choose. Counties could choose to use this funding to support existing community mental health programs that have goals that overlap with the goals of the CCCP. There are a number of existing funding streams at the county level that fund community mental health programs for individuals with severe mental illness. These funding streams include Medi‑Cal, county realignment funds, and MHSA funding. Given the flexibility that counties receive under this proposal, funding received through this pilot could supplant funding for existing programs, and counties could direct existing funding sources for community mental health toward other purposes. If this were to occur, the incentive payments might not result in an increase in services to prevent IST designations and referrals.

Details on Fiscal Oversight of Spending Are Unclear. Under this proposal, counties would be required to report to DSH how they spent funds received through the CCCP. This would include the cost to treat felony ISTs, what other funding sources were used, and what investments in upstream or downstream services were made. What systems DSH will utilize to ensure that counties are held accountable for their spending through this pilot is unclear.

Benchmark Reduction Goals May Be Too Difficult to Achieve. The overall trend in felony IST designations and referrals is increasing. DSH proposes to use counties’ level of felony IST referrals in 2018‑19 as the baseline year for measuring progress. Given the underlying trend in felony IST referrals, counties could have difficulty achieving their benchmark reduction goals in felony IST referrals in the later years of the proposal.

Unclear How the Pilot Will Be Evaluated. The proposal is not clear on the intended lessons to be learned from this pilot program, or on how the pilot program will be evaluated. We note that since counties are given flexibility on how to spend incentive funds, different programs and practices may be adopted on a “county‑by‑county” basis. This will make assessing the success of the pilot overall difficult.

LAO Recommendations

We find the intent of this proposal—to provide services to prevent people with mental health conditions from becoming IST—to have merit. The amount of felony IST designations and referrals is increasing, and current DSH efforts to expand capacity for competency restoration treatment do not directly address why people are designated as a felony IST in the first place. However, as discussed above, we raise concerns regarding the efficacy and governance of the CCCP that we suggest the Legislature direct the administration to respond to. We offer recommendations on structural changes to the pilot should the Legislature decide to approve this proposal, following further information from the administration that responds to the above concerns.

Recommendations to Improve Program Structure if Proposal Approved in Concept

There are several ways in which the Legislature could improve the structure of the CCCP to address the structural concerns we raise, should the Legislature approve of this budget request in concept. To that end, we recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation that:

- Clarifies Definition of At‑Risk‑of‑IST Population. The incentives payment component of the CCCP is meant to provide upstream and downstream services to individuals at risk of becoming IST. In order to ensure that the funding from this pilot program is directed toward that population, we recommend that the Legislature direct DSH to clarify the definition of at‑risk‑of‑IST individuals and that the definition be codified in statute. This would require DSH to review referred cases for characteristics that would help define this population.

- Establishes a Robust Evaluation Component of the Pilot. The proposal does not include a framework for how to evaluate either the progress payments or the incentive payments components of the pilot. We recommend that the Legislature direct DSH to conduct a robust evaluation of both the CBR model currently being implemented in Los Angeles County and the CBR component of the CCCP. In addition, the CCCP would give counties wide discretion in the types of programs and services provided to reduce the IST population, which may lead to many different types of programs being implemented. We recommend the Legislature direct DSH to establish a robust evaluation strategy for the incentive payments portion of this pilot as well. This would include a framework for how to compare the successes of different programs and how information on the most effective programs would be shared among counties.

- Strengthens the Fiscal Oversight Component of County Plan Submissions. Given that the details on how DSH would provide fiscal oversight of county spending under this pilot are unclear, we recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation that strengthens this component of the pilot. This would include setting up an oversight framework that holds counties accountable for their spending under the pilot.

- Sets Benchmark Reduction Goals Based on Prior‑Year’s Level of IST Referrals. Given the potential difficulty of achieving the benchmark reduction goals for felony IST designations and referrals over time, we recommend that the Legislature set these benchmark reduction goals based on counties’ prior‑year level of IST referrals.

- Establishes Non‑Supplanting of Existing County Funds. There is a significant possibility that the funding counties receive under this pilot would be used for existing programs that may utilize other sources of funding now. To ensure that the incentive payments that counties receive are not used to fund existing programs, we recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation that establishes a non‑supplantation provision for funding provided in this pilot program.

Treatment Team and Primary Care Staffing Proposal

This proposal requests $32 million General Fund and 80.9 positions in 2020‑21, ramping up to $64.2 million General Fund and 250.2 positions in 2024‑25, and ongoing at that amount thereafter, for two separate components within DSH—treatment teams and primary care. The proposal also includes changes to DSH’s supervisory structure within primary care and its clinical executive structure, provides resources to implement Trauma‑Informed Care, and provides resources to improve the patient discharge process. We provide background on these components in the following section.

Background

DSH Provides Interdisciplinary Psychiatric Treatment and Primary Care to Patients With Complex Needs. DSH provides both psychiatric and medical treatment to patients with extreme mental illnesses who have complex needs. These needs often exceed those of typical psychiatric patients because DSH patients typically have been involved in the criminal justice system. Most DSH patients also suffer from severe mental illness in the form of a primary psychotic disorder, which can be resistant to typical drug therapies for such a condition. In addition, the DSH patient population is aging, which has caused increased need for medical treatment.

DSH Follows the Clinical Treatment Team Approach to Provide Inpatient Psychiatric Care. To provide psychiatric care to its patients, DSH utilizes a treatment method called the treatment team approach—in which an interdisciplinary team is assigned a caseload of patients and provides a comprehensive treatment approach. This approach is recognized as the standard of care in psychiatric hospitals. The treatment team collaborates to develop individualized treatment plans and delivery of care for each patient at DSH. Figure 3 describes each of the positions on the treatment team.

Figure 3

Department of State Hospitals Interdisciplinary Treatment Team

|

Position |

Responsibilities |

|

Psychiatrist |

Treatment team lead, diagnostic decisions, and medication prescribing. |

|

Psychologist |

Treatment planning, assessment, therapy, and other specialized interventions. |

|

Clinical Social Worker |

Psychosocial assessment, case management, and discharge treatment. |

|

Rehabilitation Specialist |

Rehabilitation therapies and developing functional treatment goals. |

DSH Staffs Both Physicians and Nurse Practitioners for Primary Care. To provide primary care medical services to patients, DSH staffs both physicians and nurse practitioners. Physicians are primarily responsible for all phases of medical care, and provide supervision to nurse practitioners. Nurse practitioners perform medical duties similar to physicians, with a focus on addressing specific patient complaints related to general medical care, so that physicians can address more complex medical needs.

Current Treatment Team and Primary Care Caseload Ratios Are Based on Patient Acuity, Reflected in Level‑of‑Care Classifications . . . Currently, the caseload ratios for both treatment teams and primary care staff—the ratio of providers to patients—are based on patient acuity (the severity of need for mental or physical health care). This includes psychiatric acuity—which affects workload due to individual needs for individual therapy or increased aggression and self‑injurious behavior—and medical acuity—which affects workload due to individual needs for medical care. These caseload ratios are reflected in level‑of‑care classifications for DSH units. For example, acute psychiatric units and skilled nursing facilities house patients with the highest acuity, and have the lowest caseload ratio of provider to patients. Current caseload ratios are given in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Current Caseload Ratios by Level of Care

|

Level of Care |

Ratioa |

|

Acute Psychiatric and Skilled Nursing Facilityb |

1:15 |

|

Intermediate Care Facilityc |

1:35 |

|

Residential Recovery Unitsd |

1:50 |

|

aRatio of treatment provider to patients. bHighest acuity. cModerate acuity. dLowest acuity. |

|

. . . But Not Treatment or Commitment Type. DSH patients can have unique needs that are related to the treatment they receive. For example, patients who are deaf or hard of hearing require additional attention. DSH patients also can have unique needs that are related to their commitment type. For example, patients committed as IST require specialized treatment that is focused on restoring them to competency. Currently, the treatment team and primary care ratios do not reflect these factors.

DSH Clinical Staffing Study. In 2013, DSH began evaluating staffing practices at its five hospitals in a study known as the Clinical Staffing Study. (This evaluation of staffing practices has now been incorporated into a collaborative effort with Department of Finance to review practices across DSH facilities, known as Mission‑Based Review.) The department initiated the study in an effort to assess whether past practices and staffing methodologies—which often differed between each hospital—are in need of revision, particularly in light of a patient population that has grown in terms of size, age, and the number who have been referred by the criminal justice system. The study is in the process of reviewing the hospitals’ forensic departments and protective services, and the way each hospital plans and delivers treatment. In 2019‑20, DSH received funding and positions to augment its staffing ratios within its nursing services.

As part of its review of treatment teams and primary care, DSH examined all of its units to determine workload categories. Workload categories were created based on patient treatment and commitment type. DSH then produced a model to categorize its units—based on workload categories—into ”Unit Categories” displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Department of State Hospitals Clinical Staffing Study Unit Categories

|

Unit Category |

Type of Patient |

|

Admissions |

Newly admitted patients. |

|

Discharge Preparation |

Patients nearing discharge. |

|

Medical Treatment |

Patients who are receiving medical care. |

|

Incompetent to Stand Trial Treatment |

Patients who are accused of a crime but must be restored to competency before their court proceedings can continue. |

|

Mentally Disordered Offender Treatment |

Patients who have been convicted of a violent offense connected to their severe mental disorder who are committed after completing their prison term as they have been found to pose a danger to the public if released. |

|

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Treatment |

Patients referred for treatment from state prisons. |

|

Sexually Violent Predator Treatment |

Patients who have been convicted of a sex offense and are committed following their release from prison, as they have been found to have a mental disorder that makes them likely to engage in sexually violent criminal behavior. |

|

Lanterman‑Petris Short Treatment |

Patients who have been civilly committed by counties. |

|

Multi‑Commitment Treatment |

Various types of patients that are treated together, including mentally disordered offenders, Lanterman‑Petris‑Short Act patients, and individuals found not guilty by reason of insanity. |

|

Specialized Services Treatment |

Various patients with special needs such as those who are highly aggressive, require sex offender treatment, or are deaf. |

To develop new caseload ratios for the unit categories, DSH collected data to identify major factors that affect workload for its treatment teams and primary care providers—including patient acuity. It then classified its units into high, moderate, or low workload units. It classified the units separately for treatment teams and for primary care, as workload levels can be different for each of these two components. DSH then developed caseload ratios specific to whether a unit is designated as high, moderate, or low workload.

Trauma‑Informed Care. Trauma‑informed care is a comprehensive approach to delivering health care that is focused on patients who have severe mental illness and a history of trauma. DSH currently has several initiatives related to implementing trauma‑informed care across its facilities. These include staff training programs, a pilot program to screen patients for trauma, and a statewide committee on trauma‑informed care meant to steer efforts to implement trauma‑informed care in its facilities.

DSH Patient Discharge. DSH patients have unique discharge needs related to their mental and physical health needs, disabilities, and involvement in the criminal justice system. DSH currently has Discharge Preparation Units that work with patients to maintain stability and develop skills needed to succeed after discharge.

Governor’s Proposal

DSH proposes (1) new caseload ratios for its treatment team and primary care components, and associated positions to meet the new caseload ratios (2) additional positions to implement the principles of trauma‑informed care, (3) additional resources to improve the patient discharge process, and (4) other staff augmentations to address executive leadership and supervisory issues. This proposal requests $32 million General Fund and 80.9 positions in 2020‑21, ramping up to $64.2 million General Fund and 250.2 positions in 2024‑25, and ongoing at these amounts thereafter to implement these changes.

New Treatment Team Caseload Ratios. Under this proposal, new treatment team caseload ratios would be implemented using an updated methodology that includes both patient acuity and the unique workload drivers associated with treatment and commitment types. The new treatment team caseload ratios would replace the old ratios based solely on acuity, however, the positions that make up the treatment team would remain the same. Based on these updated ratios, DSH is requesting 62.6 psychiatrist positions, 59.7 psychologist positions, 32 clinical social worker positions, and 31 rehabilitation therapist positions. As discussed earlier in this report, the Clinical Staffing Study categorized DSH units as high, moderate, or low workload units, and appropriate caseloads were developed for each of these three types of units. A description of the caseload level given for each unit workload type is given in Figure 6.

Figure 6

New Treatment Team Caseload Ratios

|

Unit Workload Levela |

Caseload Ratiob |

|

High workload |

1:15 |

|

Moderate workload |

1:30 |

|

Low workload |

1:35c, 1:50d |

|

aWorkload level incorporates both patient acuity and unique workload based on treatment and commitment type. bRatio of treatment provider to patients. cDischarge preparation units. dSexually violent predator treatment. |

|

New Primary Care Caseload Ratios. Under this proposal, new primary care caseload ratios would be implemented using a combination of the updated methodology used to develop the treatment team caseload ratios, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) methodology for staffing primary care clinicians. The new primary care caseload ratios also would replace the old ratios based solely on acuity. Based on these updated ratios, DSH is requesting 26.9 physician positions and no nurse practitioner positions. Similarly, utilizing these two components, primary care caseload ratios were set according to units designated as high, moderate, or low workload. A description of the caseload level given for each unit workload type is given in Figure 7.

Figure 7

New Primary Care Caseload Ratios

|

Unit Workload Levela |

Caseload Ratiob |

|

High workload |

1:15 |

|

Moderate workload |

1:30 |

|

Low workload |

1:45 |

|

aWorkload level incorporates both patient acuity and unique workload based on treatment and commitment type. bRatio of treatment provider to patients. |

|

Other Staff Augmentations. The administration also proposes a number of additional staffing changes outside of treatment teams and primary care. Specifically, it proposes to (1) add five Trauma Treatment Specialist positions to help integrate trauma‑informed care into the DSH culture, (2) add six clinical social worker positions to establish a Discharge Strike Team, to develop relationships with community partners to help DSH establish a comprehensive discharge planning program, (3) add six Chief Physician and Surgeon positions to address alignment issues with DSH’s primary care supervisory structure, (4) add six Medical Director positions with increased compensation to address salary‑related issues with DSH’s clinical executive structure, and (5) create position authority to formalize a clinical operations division, which is currently being staffed with redirected resources.

Methodology Reassessed Annually. Under this proposal, DSH will reassess the staffing methodologies for both treatment team and primary care annually.

LAO Assessment

Adjusting Caseload Ratios Makes Sense. The administration’s proposal to create uniform staffing standards for DSH’s treatment team and primary care components across state hospitals represents an important step forward. This is because the proposal would result in the treatment team and primary care portion of the DSH budget being more accurately adjusted for the makeup of its patient population and workload‑specific certain unit types. We note that utilizing CDCR’s methodology for primary care staffing makes sense due to the amount of forensic patients within DSH.

Difficult to Recruit Psychiatrists, Making Treatment Team Caseload Ratios Potentially Difficult to Meet. DSH expects to staff the requested 62.6 additional psychiatrists at the end of this proposal’s phase‑in period for its treatment teams. The department has long had difficulty recruiting and retaining psychiatrists, recently reporting that its vacancy rate for psychiatrists was as high as about 40 percent. DSH has funded workforce development efforts to alleviate these difficulties, but hiring the proposed number of psychiatrists in the five‑year time frame might be unrealistic. If the Legislature approves these positions, many may go unfilled and DSH could redirect these resources to other purposes that the Legislature did not explicitly approve.

Proposal Requests Physicians for Primary Care But Not Nurse Practitioners, Potentially Reducing Cost‑Effectiveness. Within DSH, nurse practitioners are part of the primary care team as well, but the proposal does not request any nurse practitioner positions. Having certain duties within primary care be performed by nurse practitioners rather than physicians could be cost‑effective. DSH notes that it did not consult CDCR’s staffing methodology for nurse practitioners, and that examining the need for this staffing category was beyond the scope of this study. DSH also notes that there have been concerns raised about staffing nurse practitioner positions for patients within CDCR that DSH is responsible to treat, and that recruitment of nurse practitioners is difficult.

Unclear How Effective Trauma Treatment Specialists Would Be. DSH already has several initiatives within its facilities to implement trauma‑informed care. These include staff training programs, a pilot program to screen patients for trauma, and a statewide committee on trauma‑informed care meant to steer efforts to implement trauma‑informed care in its facilities. Whether the additional services provided by these proposed positions would improve the implementation of trauma‑informed care and the outcomes therefrom is unclear.

Unclear How Effective Discharge Strike Team Would Be. DSH has existing discharge preparation units, which are meant to help prepare patients for transition back to the community. The proposed discharge strike team will focus more on establishing relationships with community partners to find appropriate placement. DSH notes that the proposed strike team also would be tasked with identifying barriers that hinder DSH patients from finding appropriate placement in community resources, but the proposal does not provide detail on how they would do so. Improving community placement for DSH patients warrants consideration, but it is unclear how effective the proposed discharge strike team will be.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Requested Psychiatrist Positions, But Require Department to Report Back on Ability to Hire Psychiatrists. Given the difficulties that DSH has had historically in recruiting and retaining psychiatrists, DSH might use vacancies within its additional psychiatrist positions to redirect resources to other needs. These redirected resources may not fit the Legislature’s priorities for DSH. We recommend that the Legislature enact provisional language to require DSH to report on its ability to fill these additional psychiatrist positions, and condition continued funding for the positions on its ability to reasonably fill vacancies.

Require DSH to Assess Need for Nurse Practitioners and Report Back. We find that the increased workload needs for treatment team and primary care units justify additional staffing resources. However, this proposal does not request any nurse practitioner positions and only requests physicians. DSH notes that there have been concerns raised about using nurse practitioners to staff care for patients within CDCR that it is responsible for treating. We note that this does not necessarily mean that they could not be staffed for other patient classifications. DSH also has indicated that it is open to revisiting its need for nurse practitioners in the future. We recommend that the Legislature require DSH to report at budget hearings on the feasibility of assessing staffing needs for nurse practitioners relative to physicians in primary care units by the May Revision, so that the Legislature potentially could adjust the proposed staffing proposal. Should the Legislature find that DSH will have difficulty assessing that need by that time, it could choose to approve this request to address the increased workload needs, while adopting supplemental report language requiring DSH’s assessment on the issue to be submitted in conjunction with the Governor’s 2021‑22 budget. We note that a study examining CDCR’s staffing methodology for nurse practitioners may be a reasonable place to start.

Approve Trauma‑Informed Care Team on Pilot Basis and Require Evaluation. Whether the proposed Trauma Treatment Specialist positions would be successful at improving the adoption of trauma‑informed care at DSH facilities is unclear. Whether the additional services the proposed positions would add would improve existing efforts to implement trauma‑informed care within DSH also is unclear. Given this uncertainty, we recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed Trauma Treatment Specialist positions on a pilot basis, and require evaluation on effectiveness of improved adoption of trauma‑informed care.

Approve Discharge Strike Team Positions on a Pilot Basis and Require Evaluation. Whether the proposed Discharge Strike Team would be successful at improving patient placements is unclear. We recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed strike team on a pilot basis, and require evaluation on its effectiveness at improving the placement of patients back into the community after discharge from DSH.

Protective Services Staffing Proposal

Background

DSH Protective Services. DSH Protective Services is a law enforcement agency that provides 24‑hour police services for hospital operations. It provides security for all hospital buildings, manages inflow and outflow of patients, and transports patients to medical appointments and court appearances. The officers within DSH utilize Therapeutic Strategies and Interventions (TSI) when interacting with patients who have behavioral issues. TSI emphasizes less restrictive behavioral intervention techniques to manage potentially violent situations.

DSH Protective Services Support Services. DSH’s Support Services Division is responsible for ensuring safety and security during patient movements outside of patient housing areas. This includes escorting patients to outside medical appointments and court hearings. A description of the key responsibilities of Support Services is given in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Department of State Hospitals Protective Services:

Support Services Division Key Responsibilities

|

Job Duty |

Responsibility |

|

Main Entrance |

Officers operate gates, verify identities, and search pedestrians and vehicles. |

|

Visiting Center |

Officers monitor patient‑visitor interactions to ensure they follow guidelines, and monitor for contraband. |

|

Package Center |

Officers use x‑ray machines and metal detector wands to search mail. |

|

Transportation |

Officers transport patients to medical visits, court appearances, and to other state hospitals if transferred. |

DSH Protective Services Operations Division. DSH’s Operations Division is responsible for the day‑to‑day operations of protective services. This includes providing security and patrol for hospital buildings. A description of the key responsibilities of the Operations Division is given in Figure 9.

Figure 9

Department of State Hospitals Protective Services:

Operations Division Key Responsibilities

|

Job Duty |

Responsibilities |

|

Admission Unit |

Officers conduct patient classifications, process property, and fingerprint patients. |

|

Off‑Grounds Custody |

Officers provide 24‑hour security to patients while they are hospitalized at an outside medical facility. |

|

Hospital Patrol |

Officers provide security in patient housing units, conduct unit walkthroughs, and secure all hospital grounds. |

|

Perimeter Kiosks |

Officers monitor for unknown pedestrians or vehicles on hospital grounds. |

Protective Services Staffing Levels Were Based on Anticipated Need at the Time Units Were Set Up With Minor Adjustments Over Time. Each DSH facility has an allocation of protective services staff. However, the level of staffing was based on anticipated need at the time the protective services were set up many years ago, and the adjustments to them have been made in a piecemeal way in response to specific events or incidents of violence at specific hospitals. This has resulted in staffing levels that vary across hospitals. The staffing levels within DSH protective services also have not been adjusted for the increase in forensic patients at DSH.

DSH Clinical Staffing Study. As part of DSH’s Clinical Staffing Study (discussed earlier in this report), DSH reviewed protective services staffing levels as well. For protective services, it reviewed job tasks specific to each post, the number of staff required to perform these tasks, and the workload drivers specific to these posts. This review was conducted for both the Services Support and Operations Divisions within DSH Protective Services.

Overtime Concerns. DSH provides continued coverage for its posts and frequently provides that coverage through overtime. Napa State Hospital has the highest use of overtime system wide. Napa’s average monthly overtime is 86 percent higher than the average monthly overtime system wide. One of the reasons DSH conducted the Clinical Staffing Study is to reduce hospitals needing to rely on overtime to cover protective services posts.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes (1) new Protective Services staffing levels for Services Support, (2) new staffing levels for its Operations Division, and (3) additional positions for its executive leadership structure. In total, the administration requests 46.3 positions and $7.9 million General Fund in 2020‑21, 47.8 positions and $13.4 million from the General Fund in 2021‑22, and $12 million ongoing from the General Fund starting in 2022‑23. These resources are meant to implement staffing level changes at Napa State Hospital only as the first phase of this project. The intent is to implement the staffing methodologies at the other state hospitals in the future.

New Methodology for Staffing Levels in Services Support and Operations Division. This proposal requests resources to implement updated staffing levels for DSH Protective Services’ Services Support and Operations Divisions. These updated staffing levels were developed based on the DSH Clinical Staffing study’s review of workload related to specific job posts. The methodology is meant to be applied to all the state hospitals. (As described later, implementing the new methodology mainly requires additional staff at one state hospital—Napa.)

New Executive Leadership Structure. This proposal seeks to add four positions to the executive leadership structure within DSH Protective Services. These consist of (1) a Chief of Law Enforcement to oversee protective services at all five DSH facilities, (2) an Assistant Chief of Law Enforcement to provide support to the Chief of Law Enforcement, (3) five Chief of Police positions to oversee the police and fire departments at each state hospital, and (4) five Assistant Chief of Police positions to provide support to the Chiefs of Police at each state hospital.

Proposal Only Requests Funding to Apply New Staffing Methodology at Napa State Hospital. With the exception of augmentations to executive leadership and the off‑grounds custody posts, this proposal only requests funding to augment staff at Napa State Hospital due to significant overtime concerns there. The administration plans to implement these new staffing ratios at all five hospitals in the future.

LAO Assessment

Adjusting Protective Services Staffing Levels Makes Sense. Given the lack of a standardized practice for staffing Protective Services job posts at DSH, adjusting these staffing levels based on the methodology outlined in DSH’s Clinical Staffing Study is reasonable.

Unknown Cost of Implementing These Staffing Levels to Remaining DSH Facilities. Given that this proposal requests funding only to implement staffing changes at Napa State Hospital, the costs of implementing this reform across the other DSH facilities is unknown. The Legislature might want to consider what this cost would be before it approves this request.

LAO Recommendations

Request Total Cost to Implement the Proposed Staffing Level Across All DSH Facilities and a Time Schedule for Doing So. Given that the cost of implementing updated staffing levels across the remaining four state hospitals is unknown, we recommend that the Legislature require information from DSH on the total cost to implement all phases of this proposal, as well as an implementation schedule for doing so. Based on this information, the Legislature could consider whether this specific proposal—given its implications for the rest of the state hospitals—is the best path forward.