LAO Contact

This post was prepared with assistance from Juan Heredia.

February 19, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Improving the State’s Unpaid Wage Claim Process

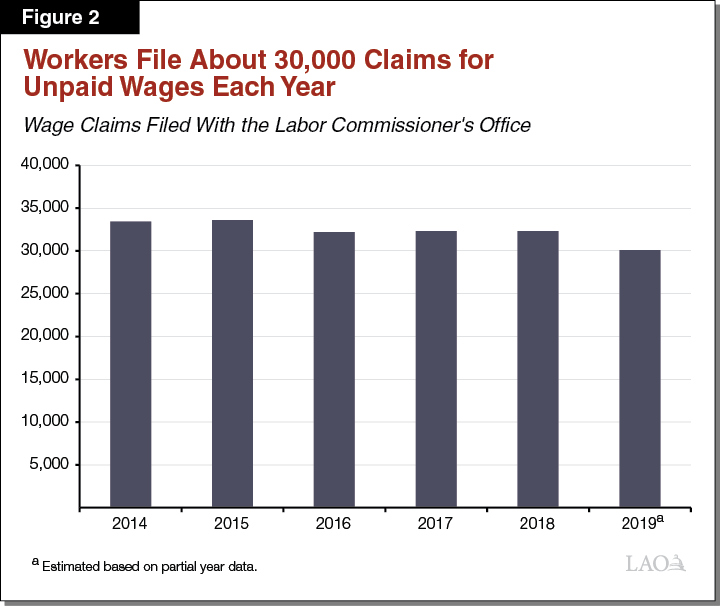

Filing a claim for unpaid wages with the Labor Commissioner’s Office is one option workers have to recover unpaid wages their employer owes them. Each year, about 30,000 workers file wage claims. In 2017, workers filed claims for a total of $320 million in unpaid wages—about $10,000 per claim on average—and recovered about $40 million in total. Of the total amount recovered, workers who settled their claims received $25 million. Workers who did not settle and instead proceeded to a formal hearing collected the remaining $15 million. However, less than half of workers who received an award for unpaid wages were able to collect any wages from their employer. On average, workers waited 396 days for the state to adjudicate their wage claim.

In this post, we provide a background on employment laws, take an initial look at worker outcomes in the wage claim process, and highlight several opportunities to improve the process. We also assess the Governor’s proposal to hire additional staff at the Department of Industrial Relations to reduce delays that have recently begun to affect wage claims.

The Wage Claim Process

Employment Laws, Benefits, and Protections. State law requires that employers follow rules about employee wages, hours, and breaks. These rules set the state minimum hourly wage and when rest and meal breaks must be provided. Employers also must provide certain benefits, including having insurance to cover on-the-job injuries, reimbursing employees for job expenses, and contributing to unemployment insurance. Finally, employees have certain job protections—for example, taking time off due to illness, a short-term disability, or to bond with a new child. The Labor Commissioner’s Office enforces these laws and adjudicates alleged violations.

The Labor Commissioner’s Office Hears Workers’ Wage Claims. The Labor Commissioner’s Office, within the Department of Industrial Relations, hears unpaid wage claims. Workers file a claim when they believe their employer has not complied with the state’s employment laws. When filing a claim, workers estimate the amount of wages their employer owes. Enacted in 1976, the wage claim process is designed to be a simple alternative to filing a lawsuit in court, in that wage claims do not require a lawyer and have lower standards of evidence than the courts.

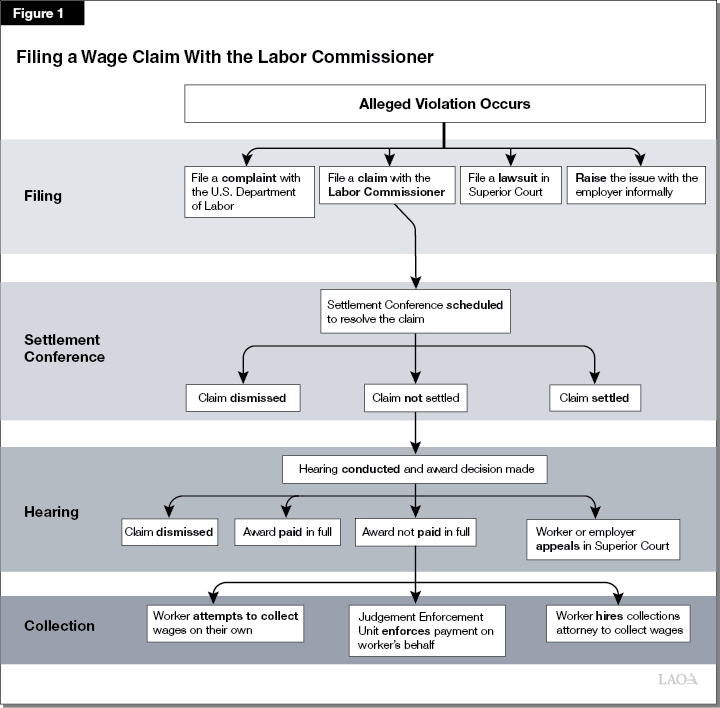

Filing a Claim for Unpaid Wages. One option workers have to collect unpaid wages is to file a wage claim with the state. (Workers have other options that we do not address in this post, including filing a complaint with the federal Department of Labor for violations of federal employment law, filing a lawsuit in court, or addressing the issue informally.) Figure 1 shows how a typical wage claim proceeds. Under state law, wage claims are to be adjudicated within 120 days. At each stage, staff may dismiss the claim if (1) the worker does not show up, (2) the Labor Commissioner does not have jurisdiction to hear the issue, or (3) the parties settle privately. Below, we describe each stage in a typical claim:

Filing a Claim. Workers file wage claims with their regional Labor Commissioner’s Office by submitting forms and records related to their claim. Workers may submit forms in person or via e-mail, but not online. The claim includes information about the employer, the worker’s hours and pay, and the worker’s estimate of the wages their employer owes them.

Settlement Conference. Once a worker has filed a claim, the Labor Commissioner schedules a settlement conference. During the settlement conference, a Deputy Labor Commissioner hears from the worker and the employer but does not collect evidence, such as pay stubs, that could prove or disprove the allegation. The Deputy Commissioner also reviews the worker’s estimate of unpaid wages and may encourage the two sides to settle the claim. If the two sides settle, the claim ends when the employer pays the settlement amount. If the two sides do not settle, the claim proceeds to a hearing.

Hearing and Decision. At the wage claim hearing, a hearing officer collects and reviews evidence and hears sworn testimony. Afterward, the hearing officer issues their decision about the claim and the amount of money, if any, the employer owes the worker. Either side may appeal the decision in Superior Court.

Enforcement. If neither side appeals, the Labor Commissioner sends the decision to the local court, after which it becomes an enforceable judgment that the worker can collect. In certain cases, the Labor Commissioner’s Judgment Enforcement Unit assists the worker in collecting unpaid wages. Often, though, the worker must try to collect the wages awarded in the judgment on their own, sometimes with the help of a private collections attorney or county sheriff.

A Look at Worker Outcomes

About 30,000 Workers File Wage Claims Each Year. As shown in Figure 2, about 30,000 workers file wage claims each year with the Labor Commissioner’s Office. This represents about 1 in 600 workers statewide. In 2017, the most recent year with complete data, 33,000 workers alleged a total of $320 million in unpaid wages—nearly $10,000 per worker. About one-third of these claims were dismissed, often because the worker did not attend the conference or the parties settled informally. Of the claims that were not dismissed, about half of them settled and about half of them proceeded to a hearing.

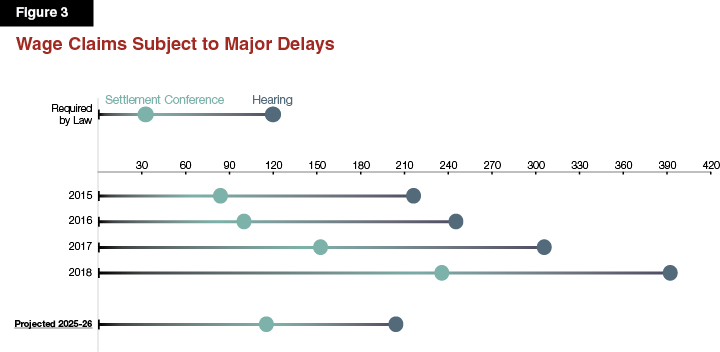

Wage Claims Subject to Major Delays. Under state law, wage claims are to be adjudicated within 120 days. As shown in Figure 3, however, the average claim took almost 400 days in 2018. According to the administration, this delay is due to new laws that expanded the Labor Commissioner’s authority to collect wages, which makes some cases more complex. Recent efforts to more thoroughly review claims also might have had the effect of delaying cases.

Wage Claim Delays Favor Employers. Long delays between the filing, settlement conference, and hearing favor employers for three reasons. First, the longer the claim process takes, the more likely a worker will move or otherwise drop the claim. When this occurs, staff dismiss and close the claim and no unpaid wages can be collected. Second, long delays may encourage workers to settle their claim for smaller amounts. Although workers may receive more if they continue to a hearing, some choose instead to settle because they cannot afford to wait for the hearing. Third, long delays favor noncompliant employers insofar as the long time line discourages workers from filing a claim in the first place.

Many Affected Workers Who Could File Claims Do Not. Although about 1 in 600 workers statewide file wage claims each year, the share of workers owed unpaid wages likely is much greater than 1 in 600. A few of these other workers probably try to recover unpaid wages in other ways, such as through a lawsuit or a federal complaint, but most do not.

Common Claims and Industries. Most wage claims allege several employment law violations. As shown in Figure 4, waiting time penalties, failure to pay regular or minimum wages, and rest and meal period violations were the most common claims in 2017. Among workers who reported the industry in which they work, the most common jobs were in restaurants, agriculture, construction, medical offices, and private security.

Figure 4

Most Common Claims and Industries

Claims Filed in 2017

|

Most Common Claims |

Share |

Most Common Industries |

Share |

|

|

Waiting time penalties |

24% |

Restaurants |

11% |

|

|

Failure to pay regular wages |

17 |

Agriculture |

7 |

|

|

Failure to pay minimum wage |

14 |

Construction |

7 |

|

|

Rest and meal period wages |

12 |

Hospitals and medical offices |

6 |

|

|

Overtime |

9 |

Security guards and patrol services |

5 |

|

|

Unreimbursed business expenses |

3 |

Trucking |

4 |

|

|

Liquidated damages |

3 |

Landscaping services |

4 |

|

|

Vacation wages |

3 |

Staffing agencies |

4 |

|

|

All other |

15 |

Home health care services |

2 |

|

|

Total |

100% |

Grocery and convenience stores |

2 |

|

|

Janitorial services |

2 |

|||

|

Auto repair |

2 |

|||

|

Hotels and motels |

2 |

|||

|

All other |

44 |

|||

|

Total |

100% |

Overall, Workers Report Collecting Less Than 20 Percent of Unpaid Wages Owed. Workers filed claims in 2017 to recover $230 million in unpaid wages and collected $40 million, less than 20 percent of the amount claimed. These figures do not include dismissed claims.

At Settlement, Workers Recover About Half of Wages Owed. Workers who settle at the settlement conference recoup, on average, about half of their alleged unpaid wages. Settlements vary and depend on various factors. These include: (1) the claim size (larger claims tend to settle for a smaller percentage), (2) personal finances (workers who can afford to may insist on a larger settlement or go to hearing), (3) the advice of the settlement officer, and (4) the employer’s interest in a settlement. Overall, workers settled at the settlement conference for about $15 million in unpaid wages.

At Hearings, Most Workers Receive Award, but More Than Half Collect No Wages. Most workers who proceed to a hearing receive an award in their favor. However, in 2017, about 60 percent of workers who received an award ultimately recovered zero wages, despite being awarded about $60 million in unpaid wages. (This is because employers did not pay the amount awarded.) The remaining workers—those who were able to recover unpaid wages—collected about $15 million.

Large Awards More Likely to Go Uncollected. Workers are less likely to collect unpaid wages when their award is large than when their award is small. For workers who collected wages, the median amount was about $3,700. For workers who did not recoup wages, the median amount uncollected was $8,600, more than twice as large.

Governor’s Proposal

The 2020‑21 Governor’s budget includes 15 positions and $2.3 million special funds, increasing to 63 positions and $8.8 million special funds ongoing by 2023‑24, to add settlement and hearing officers at the Labor Commissioner’s Office to reduce delays for workers seeking unpaid wages. These positions, once fully phased in, would increase the wage claim staff by about 50 percent.

Proposal Also Notes Effort to Build Industry Expertise. The proposal also highlights recent efforts to build industry expertise among its staff. For instance, each hearing officer in an office might specialize in one field—say, wage claims in the construction industry. Construction industry claims would be heard by this hearing officer. Over time, the administration expects this to improve outcomes for workers because hearing officers will better understand industry-specific practices and commonly alleged violations.

LAO Analysis

Additional Staff Should Help Reduce Delays, but by How Much Is Unknown. Increasing hearing staff by about 50 percent should notably reduce wage claim delays. The administration expects the 50 percent staff increase to reduce claim duration by 50 percent—from 400 days to 200 days, as shown earlier in Figure 3. This probably overstates by how much the average claim duration will shorten. In all likelihood, if no other changes are made, cutting the claim duration in half would require 100 percent more staff, in effect doubling the staff size, as opposed to 50 percent more staff. Although the claims duration probably will shorten by a smaller amount than what the administration expects and the exact reduction is unknown, the average claim duration could decline by 100 days or more.

Reducing Delays Should Improve Worker Outcomes... Any improvement in the wage claim time line likely will benefit workers because fewer workers would withdraw their claims and workers could settle for higher amounts. The size of these benefits is unknown.

...But Broader Challenges and Opportunities Remain. Reducing the wage claim duration represents a key first step toward improving worker outcomes, yet two key challenges remain. First, regardless of the duration of the claim, many workers clearly have difficulty recovering wages on their own, without the support of a private attorney or the state. Second, only a small portion of affected workers statewide file wage claims each year, meaning the vast majority of unpaid wages go uncontested. Addressing these ongoing challenges would require close legislative involvement over several years and, potentially, significant new resources at the Labor Commissioner’s Office.

Recommendations

Approve Proposal. We recommend the Legislature approve the request to add settlement and hearing officers at the Labor Commissioner’s Office to address long delays for workers who file wage claims. While the exact outcomes of adding these staff are unknown, the severity of the existing delays—particularly given the statutory time line—warrants additional resources.

Take Broader Look at State’s Wage Claim Process. The wage claim process was created in 1976 to provide “a speedy, informal, and affordable method to resolve wage claims.” In the decades since, the Legislature has enacted new employment requirements and granted the Labor Commissioner additional authority to collect unpaid wages and penalties when employers do not comply with these requirements. The increasing delays identified by the administration, as well as the difficulties many workers experience collecting unpaid wages, raise questions about whether the wage claim process continues to meet the Legislature’s original objectives. In light of these questions, we recommend that the Legislature take a broader look at the wage claim process to address some of the major challenges workers face as they seek to recoup unpaid wages. Below, we discuss several follow-up actions for the Legislature to consider:

Set Benchmarks for Worker Outcomes. In light of the major employment laws enacted in recent decades, the Legislature could reevaluate its goals for the wage claim process. In so doing, the Legislature could set benchmark standards for worker outcomes, besides the statutory time line under current law, that align with its contemporary goals. For example, the Legislature could set a standard that at least three-quarters of workers who receive a hearing award are able to collect their unpaid wages. Benchmark standards such as this would allow the Legislature and the administration to evaluate the wage claim process and make updates as needed.

Request Annual Reports. State law requires the investigative arm of the Labor Commissioner’s Office to report their results each year. These reports are available on the Labor Commissioner’s website. Requiring the wage claim adjudication unit to also report results could help focus legislative and public oversight.

Simplify Process to Lower Hurdles. Streamlining the wage claim process could reduce avoidable delays and encourage more affected workers to file claims. Many workers hear about the Labor Commissioner’s Office through word of mouth. As a result, hearing stories of delays from others may discourage some workers from submitting claims. One option to simplify the wage claim process is to set up an online filing portal where workers can submit their claim, parties can track the claim and submit requested documents, and staff can communicate with the parties.

Take a More Active Role in Collections. Taking a more active role in collections and enforcement could increase the amount of unpaid wages workers recover. One immediate option would be to provide additional resources for the Judgment Enforcement Unit to collect wages on behalf of more workers. Other options, including authorizing the Labor Commissioner to use new enforcement tools or establishing a fund to cover uncollected wages in certain cases, would require careful consideration and changes to state law.

Reimburse Legal Aid Nonprofits and Community Groups. In recent years, the state has reimbursed legal aid nonprofits for their work guiding individuals through immigration and naturalization proceedings. The Legislature could consider a similar program for legal aid nonprofits and community groups that assist with wage claims.