LAO Contacts

February 20, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget

Medical Education Analysis

Summary

Governor Proposes Augmenting Funding for Two University of California (UC) Medical Schools. For the UC Riverside School of Medicine, the Governor proposes a $25 million ongoing General Fund augmentation to support operations and expand enrollment. In conjunction, the Governor proposes approving a $94 million project to construct a new Riverside medical education building. At the UC San Francisco (UCSF) Fresno branch campus, the Governor proposes $15 million ongoing General Fund, also to support operations and expand enrollment. According to UC staff, UCSF Fresno intends to submit an expansion plan in March.

Proposals Raise Questions About How Best to Address Regional Physician Shortages. The Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley have significantly fewer physicians per capita than other regions in the state. Providers in these regions appear to be responding, with both regions seeing increases in medical school enrollment and physician residency slots. Analysis is lacking as to whether these trends will be sufficient. To the extent they are not, the Legislature has options to further increase physician supply. In recent years, the state has increased funding for physician residency and physician incentive programs (such as loan repayments). These initiatives tie funding more closely to the end of the physician pipeline. They might be more cost‑effective policy responses than expanding medical school enrollment to attract physicians to certain geographic areas, but data are lacking to fully compare their relative effectiveness.

Riverside Proposal Could Be Improved. If the Legislature is interested in expanding medical school enrollment at UC Riverside, we recommend two improvements. First, we recommend setting enrollment targets and aligning state funding. For example, rather than giving the school an augmentation all at once in 2020‑21 (even though the school does not plan to begin growing enrollment until 2023‑24), the Legislature could provide the first augmentation in 2022‑23 and then spread further augmentations over several subsequent years. Second, we recommend the Legislature inquire about the school’s expansion plans during spring hearings. Under the current plan, some of the proposed augmentation would supplant campus and UC support for the school. If the freed‑up funds would be used for low legislative priorities, the Legislature could reduce the proposed augmentation or designate that the funds support enrollment beyond the school’s current plan. In either case, the signal would be that the campus should not reduce its existing support for the school.

UCSF Fresno Proposal Requires Further Planning and Review. The UCSF Fresno proposal also provides funding without first setting enrollment expectations. Additionally, the proposal lacks a fully developed expansion plan and facility assessment. Furthermore, according to UC, the forthcoming UCSF Fresno plan will propose establishing a new joint medical program with UC Merced, but this is only one of many options UCSF Fresno has explored the past few years. Given the complex and long‑term consequences at stake, we recommend the Legislature withhold action until it has received a detailed plan and held an oversight hearing to vet it.

Introduction

In this brief, we analyze the Governor’s proposals relating to UC medical education. After providing an overview of medical education, we first analyze the Governor’s proposals to expand enrollment and build a new academic building at the UC Riverside School of Medicine. We then analyze the Governor’s proposal to expand enrollment and services at the UCSF Fresno branch campus.

Overview

The Governor’s proposals would expand UC medical education programs in an effort to increase physician supply in two regions of the state. In this section, we provide an overview of both medical education in California and physician workforce issues.

Medical Education

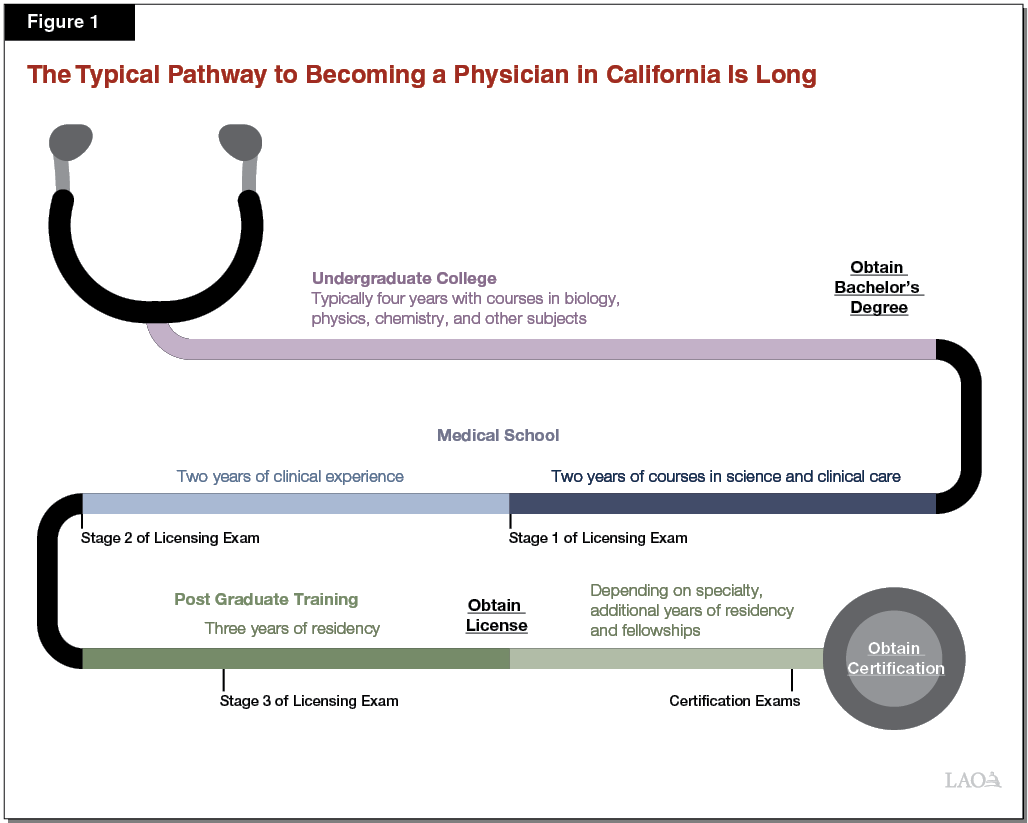

Becoming a Doctor Entails Long Education Pathway. As Figure 1 shows, students first complete basic science preparatory work as undergraduate students. They then complete four years of medical school, typically consisting of two years of basic science instruction and two years of clinical experience. After medical school, students complete postgraduate training known as residency in a specific medical area, such as family medicine or surgery. Though state law only requires three years of residency to receive a license, most medical students complete additional years of training to receive industry‑recognized certification in a specific medical area.

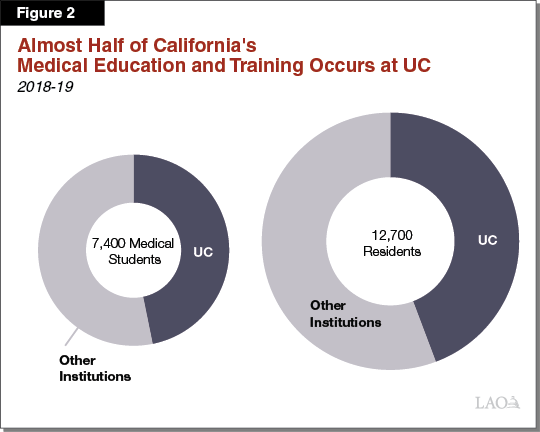

California Has Numerous Public and Private Medical Education Programs. California has 13 medical schools (6 public schools and 7 private schools) enrolling 7,400 students. In addition, California has 12,700 physician residents trained by nearly 100 sponsors. Residency sponsors consist of medical schools, hospitals, and other medical providers. In both California and across the nation, the number of residency slots exceeds the number of medical school slots. To fill residency slots, sponsors rely on graduates not only from California and other states but from Canada and other countries. In California, UC is the sole public higher education institution tasked with providing medical education. Six UC campuses—Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Diego, and San Francisco—operate medical schools and residency programs. As Figure 2 shows, UC educates almost half of medical school students and trains almost half of physician residents.

Medical Education Is Relatively Costly. Available data suggest medical education likely is the most costly form of instruction in higher education, with costs ranging from high tens of thousands of dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars per student. The high cost is largely due to very low overall student‑faculty ratios and high faculty compensation. Most medical schools hire more faculty than students, with an average student‑faculty ratio of 0.5. That is, medical schools, on average, hire two faculty members for each medical student. The ratios are driven primarily by the need for many clinical faculty to oversee students as they undertake their clinical rotations during their third and fourth years of medical school.

Medical Education Is Subsidized by Clinical Revenues and Public Funds. Medical schools rely on many sources to fund instruction, research, and clinical training. Many medical schools subsidize costs from clinical revenues earned by their faculty, who often have dual appointments working as active physicians at their medical center. UC medical schools also cover operations with state General Fund and student tuition. At UC, total annual resident tuition and fee charges range from $36,021 at UCSF to $41,231 at UC Davis. In contrast to medical schools, virtually no state General Fund directly subsidizes residency programs. Instead, residency programs in California and across the nation cover their operating costs using primarily clinical revenues and federal funds.

Accrediting Bodies Set Standards. UC medical schools are accredited by the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME), and residency programs are accredited by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Like many other accrediting bodies, LCME and ACGME are peer‑run, consisting of member medical schools and residency programs throughout the country. A chief concern of both bodies is to ensure programmatic funding and resources are adequate to support enrollment. When programs wish to expand enrollment or slots, they are expected to notify LCME and ACGME of their plans. If these accrediting bodies determine schools and programs lack adequate resources, they can request more information, undertake further review, or consider various sanctions.

Physician Workforce

California Has Over 110,000 Licensed Physicians. Of these physicians, researchers estimate around 28,000 are employed in a primary care medical area—generally defined as family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology. Physicians in these areas are considered to be the first point of health care for patients. The state’s remaining physicians are employed in numerous specialty areas, such as psychiatry or surgery. In addition to physicians, patients can receive health services from a variety of other providers. For example, California has around 29,400 nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Patients can also receive mental health services from psychologists, case workers, and other providers. These other providers generally have narrower scopes of practice than physicians. For example, physicians have significantly greater authority than these other providers to prescribe medication.

Some Data Suggest California Is Facing Shortages in Certain Medical Fields. Available data suggest that shortages are concentrated among primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Specifically, a 2017 study from researchers at UCSF estimated California could face a shortage of around 4,100 primary care providers (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) by 2030. In one of our 2019 reports, we found that psychiatrist wages have grown much faster than other occupations since 2010, a potential indicator of a shortage. (In contrast, we did not find data indicating a shortage among other mental health professionals, such as psychologists and social workers.)

Data Show Longstanding Regional Disparities in Supply of Physicians. According to most estimates, the state’s inland regions—the Inland Empire, Central Valley, and Northern California—have notably lower numbers of physicians and other health care providers per capita than the state’s coastal regions. For example, a 2017 study from researchers at UCSF estimated that the primary care provider to population ratio in the Bay Area is more than double the ratio in the Inland Empire.

State Funds Three Types of Programs in Response to Physician Shortages. First, a portion of UC medical students are enrolled in specialized medical education programs focused on providing care to certain communities (such as disadvantaged populations or rural communities). These programs are known as Programs in Medical Education (PRIME). Second, the state funds competitive grant programs for physician residency programs. To qualify for these state grants, residency programs must focus on primary care, emergency medicine, or psychiatry, and demonstrate they are serving certain geographic areas of the state. Lastly, the state has expanded a variety of incentive initiatives (such as loan repayments and stipends) to attract new physicians to work in shortage areas. To date, the Legislature has lacked adequate information to gauge the relative cost‑effectiveness of the three types of programs (medical school programs, physician residency programs, and fiscal incentive programs) at increasing the supply of physicians in underserved regions.

UC Riverside School of Medicine

In this section, we provide background on UC Riverside’s School of Medicine, describe the Governor’s proposals to expand the school, assess the proposals, and offer issues for consideration.

Background

UC Riverside Is UC’s Newest Medical School. Prior to operating a medical school, the Riverside campus provided basic science instruction to a relatively small number of medical students. After two years of study, the students then completed their clinical rotations at UC Los Angeles. In 2008, the UC Board of Regents authorized the Riverside campus to run a full medical school. Though approved by the board in 2008, several years of planning elapsed prior to the school enrolling its first cohort in 2013‑14. The delay was largely due to challenges with the school receiving preliminary accreditation from LCME. The school eventually received preliminary accreditation in 2012 and became fully accredited in 2017.

School Relies on Surrounding Hospitals for Its Clinical Training. The Riverside campus differs from the other UC medical schools in that it does not operate its own medical center. To offer clinical placements for its students and sponsor residency programs, the Riverside medical school partners with nearby hospitals and clinics. Physicians at these medical centers provide the clinical instruction, with about 60 percent of them providing instruction on a voluntary, unpaid basis.

School Now Receives Funds From Multiple Sources. The 2013‑14 state budget provided $15 million ongoing General Fund to the school. While the school considers this annual appropriation to be an important source of operating funding, the school’s budget has since grown significantly. In 2019‑20, the school anticipates receiving $75 million in total funding, with almost half coming from clinical revenues.

Campus and UC Office of the President Contribute Funding to the School. In recent years, the Riverside campus and UC Office of the President have provided funds to the school to help cover its operating costs. For 2019‑20, the School of Medicine reports contributions from the Riverside campus, UC Office of the President, and campus reserves. As reserves are generally best suited to cover one‑time costs, rather than operations, the Riverside campus has characterized the School of Medicine as having a budget deficit. Both the campus and the medical school would like to discontinue the school’s reliance on reserves for covering ongoing operating costs.

State Preliminarily Authorized New Medical School Building. Currently, the Riverside medical school has a total of around 39,000 assignable square feet dedicated to its instruction and administrative functions. The space includes one main education building, associated on‑campus modular space, a small amount of instructional space in the campus’s science library, and off‑campus leased office space for faculty and staff. In the 2019‑20 budget, the state adopted provisional language authorizing UC to “pursue a medical school project at the Riverside campus.” Associated intent language indicated the state would increase UC’s General Fund support in future years to finance the project.

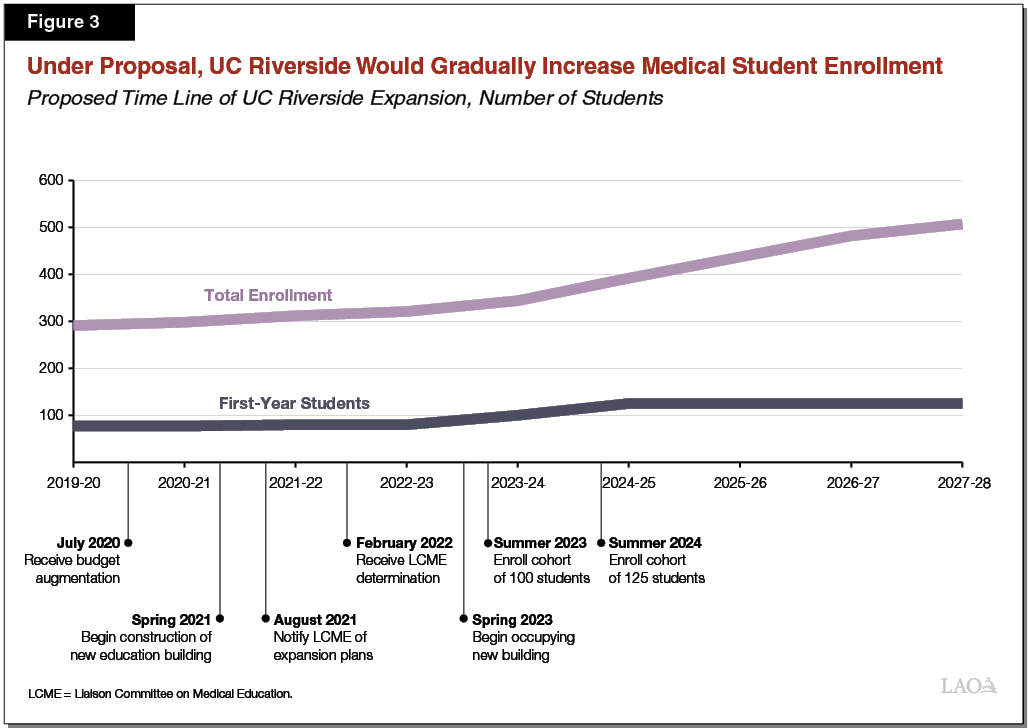

Proposals

Provides $25 Million Ongoing to Expand Riverside School of Medicine. The Governor’s Budget Summary indicates that the purpose of the proposed augmentation is to enhance the school’s operational support and expand enrollment. Budget provisional language further states that the funds are to supplement and not supplant existing funds provided by UC for the medical school. The budget does not state a specific enrollment target. According to UC staff, the Riverside campus would like to grow its incoming medical school cohort size from 77 students to 125 students. As Figure 3 shows, the school would not begin growing the number of incoming students until the 2023‑24 academic year. The campus projects its medical school enrollment would eventually reach around 500 students (four cohorts consisting of 125 students each) by 2027‑28.

Proposes Approving New Medical School Facility. UC submitted a proposal for a new UC Riverside medical education building in September 2019. As Figure 4 shows, the proposal is for the medical school to maintain its existing education building but stop using its existing off‑campus leased space and replace its on‑campus modular buildings. In addition to constructing a new building, the medical school proposes renovating some space in its science library. UC is seeking $94 million in bond authority to support working drawings and construction costs. When UC begins paying associated debt service (expected in 2023‑24), the annual cost would be $6.8 million, paid over 30 years. Under UC’s debt service projections, the total cost to pay off principal and interest would be $204 million ($94 million principal and $110 million interest).

Figure 4

Proposed Facility Project Would Increase

UC Riverside School of Medicine Space

|

Prior to Project |

After Project Completion |

|

|

Space (asf) |

||

|

New education building |

— |

65,000 |

|

Existing education building |

19,829 |

19,829 |

|

Orbach Library |

1,946 |

10,946 |

|

Modular building |

4,659 |

— |

|

Leased off‑campus space |

12,600 |

— |

|

Totals |

39,034 |

95,775 |

|

Students |

292 |

500 |

|

Space per student |

134 |

192 |

|

Note: Excludes School of Medicine’s research and health clinic space, which would remain unaffected by the proposal. asf = assignable square feet. |

||

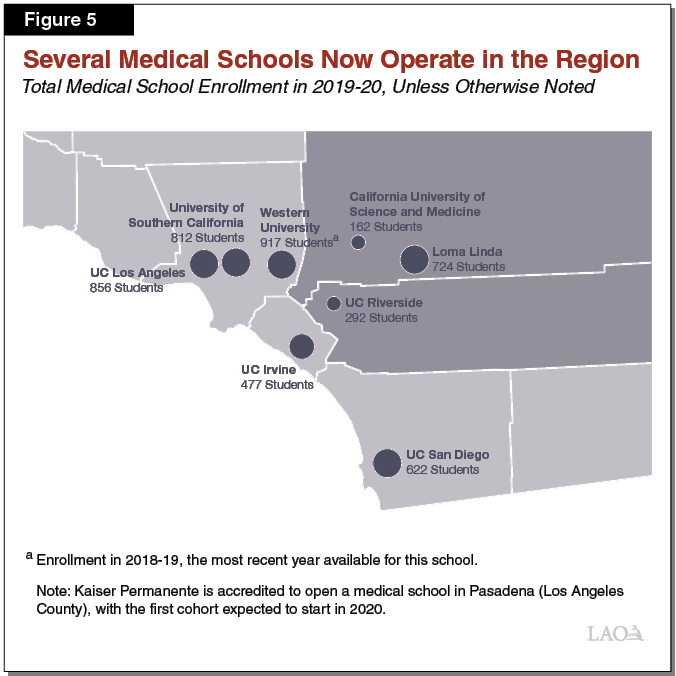

Assessment

Region’s Medical Schools and Residency Programs Appear to Be Responding to Shortage. In recent years, both medical schools and residency programs in the Inland Empire appear to be taking steps to increase physician supply in the region. As Figure 5 shows, the Inland Empire has two private medical schools. One of these schools—the California University of Science and Medicine—opened recently and is growing enrollment. Furthermore, Western University, located just outside of the region in nearby Pomona, has grown enrollment considerably over the past several years. At both schools, California students comprise over 80 percent of incoming students. Residency slots have also increased notably in the region in recent years. According to national residency match data, the number of first‑time resident slots in the Inland Empire grew 58 percent between 2015 and 2019. Analysis is lacking as to whether these recent developments are sufficient to address gaps in the Inland Empire’s regional supply of physicians.

Impact of Proposal on Increasing Physician Supply in Inland Valley Could Be Small. As the Governor’s proposal would increase the school’s incoming cohort from around 80 students to 125 students, the proposal would increase the number of medical schools graduates in the state by about 45 graduates annually. According to UC Riverside, about one‑third of its medical school graduates currently remain in the Inland Empire for their residency program. The school notes that this retention rate could change in the future, but the current rate would result in about 15 additional physician residents in the Inland Empire annually. Given that the school’s first cohort only recently graduated from medical school and many from that graduating class are still in their residency programs, it is too soon to evaluate how many UC Riverside students ultimately will practice medicine in the region.

Other Approaches Might Be More Effective at Increasing Physicians in the Inland Empire. While increasing medical school enrollment likely is an effective way to increase the statewide supply of physicians, programs that target funds toward the end of the medical education pipeline could have stronger regional effects. For example, the state in recent years has increased funding for primary care residency programs and certain physician incentive programs (such as loan repayment programs). In contrast to general appropriations to medical schools, these other types of programs tie funding to attracting physicians to practice in high‑need medical areas and geographic areas. As noted earlier, the lack of more comprehensive data on these initiatives hinders the Legislature’s ability to assess their relative cost‑effectiveness in addressing regional physician shortages.

School’s Initial Plan Supplants Existing Funding. The UC Riverside School of Medicine’s budget plan would have a portion of the proposed $25 million General Fund augmentation replace existing campus and UC Office of the President support for the school. (In future years, the school plans to maintain a balanced budget primarily by increasing its clinical revenues and student tuition revenue as it grows its staffing and enrollment.) Potentially, the campus could use the freed‑up redirected funds in areas that are of lower priority to the Legislature than the medical school.

Recommendations

If Proposal Is Pursued, Enhance Accountability. The Governor’s proposed provisional language associated with the $25 million General Fund augmentation does not establish an enrollment target for the UC Riverside School of Medicine. Were the Legislature to decide to fund enrollment growth at the school, we recommend it set enrollment targets and specify the period of time over which the school has to meet the targets. The Legislature also might consider aligning the timing of any General Fund augmentation with the school’s enrollment growth plans. Under this approach, the state would ramp up funding as the school’s enrollment grows, rather than allocating it all at once in 2020‑21. For example, the Legislature could commence enrollment growth funding in 2022‑23 (one year prior to the school enrolling a larger student cohort), then spread further augmentations over several subsequent years.

Request School Report During Spring Hearings on How It Plans to Use Redirected Funds. To ensure any General Fund augmentation for the school meets legislative priorities, it will be important for the Legislature to better understand how the Riverside campus would spend any redirected funds. To the extent the redirected funds would be used for low legislative priorities, the Legislature could correspondingly reduce the proposed augmentation. Alternatively, the Legislature could retain the size of the proposed augmentation but designate that the funds support additional enrollment beyond the school’s current expansion plan. In either case, the Legislature would be signaling that the campus should not reduce its existing support for the medical school.

Consider Capital Proposal in Context of School’s Expansion Plan and Competing Capital Priorities. Given that the primary rationale to construct a new facility at UC Riverside is to support medical school enrollment growth, we recommend the Legislature ensure that the school’s plan to expand its operations is well aligned with its capital expansion plan. We also encourage the Legislature to keep UC’s other capital priorities in mind. As we discuss in other higher education reports, UC faces many high‑priority seismic renovation and maintenance needs that will likely place budget pressure on the Legislature for many years to come. Were the Legislature to deem this medical school project to be high priority in the context of all the university’s and state’s needs, the Legislature could consider the project a potential candidate for Proposition 13 (2020) funds were the measure to pass in March.

UCSF Fresno

In this section, we provide background on the UCSF Fresno branch campus, describe the Governor’s proposal to expand the branch campus, assess the proposal, and offer a recommendation.

Background

UCSF Has Operated Medical Education Programs in Fresno Since 1970s. In 1975, the state provided one‑time funding to establish UCSF Fresno. Over the years, UCSF Fresno has supported third‑year rotations for medical students from UC Davis and UCSF as well as physician residents. In 2001‑02, the state appropriated funds to construct a new Fresno facility to house these programs, and, in 2005, UCSF Fresno moved into the new 87,700 square foot facility adjacent to a Fresno medical center. UC reports that the current site hosts around 150 medical students in clinical rotations and sponsors 320 physician residents. Throughout UCSF Fresno’s history, some of its activities have occurred on site and some in community hospitals.

UCSF Fresno Also Supports San Joaquin Valley PRIME Program. In 2011, UC established a new PRIME program focused on practicing medicine in the San Joaquin Valley. Under the program, known as San Joaquin Valley PRIME, medical students completed their two years of basic science instruction at UC Davis, then completed one year of clinical rotations at UCSF Fresno, before returning to UC Davis to complete their second year of clinical rotations. According to UC, the San Joaquin Valley PRIME program enrolled cohorts of 8 students annually (with around 32 students enrolled across four years). In 2015‑16, the state provided $1.9 million ongoing General Fund for the program. The authorizing legislation—Chapter 2 of 2016 (AB 133, Committee on Budget)—stated that the program should enroll 48 students. That is, the funding grew the program’s enrollment from cohorts of 8 students (or 32 students across 4 cohorts) to cohorts of 12 students (or 48 students across 4 cohorts). Because of the timing of the appropriation, UC Davis did not begin spending the funds until the 2016‑17 academic year.

A Couple of Years Ago, UC Began Studying Possible Expansion of Fresno Programs. In 2017, the UC Office of the President funded a third‑party study of options to expand medical education at UCSF Fresno. The study assumed UCSF would administer the San Joaquin Valley PRIME program, grow the program’s enrollment to cohorts of 50 students annually (200 students across 4 years), and provide a greater portion of instruction in Fresno. The study developed three options to fulfill these objectives, described below:

- Hybrid Model. Under this approach, students first would complete their two years of basic science instruction at UCSF’s main campus, then complete their two years of clinical rotations at Fresno. Each year, 100 students would be enrolled at the UCSF main campus and 100 students at the Fresno branch campus.

- Full Branch Model. Under this approach, UCSF students would complete all four years—both basic science and clinical—at Fresno (for an annual total of 200 students at Fresno). The study further considered options for faculty to use technology to remotely deliver instruction to Fresno students from the UCSF campus.

- Joint Model. Rather than beginning instruction in San Francisco or Fresno, under this approach UCSF students would complete basic science instruction at the Merced campus. Students would then complete clinical rotations at Fresno. Each year, 100 students would be enrolled at UC Merced and 100 students at the Fresno branch campus.

UCSF Has Taken Initial Steps Toward Expansion. In 2018, UCSF received accreditation from LCME for the Fresno operations to become a branch campus and begin supporting two years of rotations (rather than only one). The following year, UC Davis transferred administration of the San Joaquin Valley PRIME program to UCSF. For the first cohort in 2019, consisting of six students, UCSF is taking the hybrid approach. Specifically, PRIME students complete basic science instruction at the UCSF main campus, with portions of their time (such as weeklong experiences and summer research projects) spent at Fresno. The students then complete all clinical rotations at Fresno. UCSF plans enrolling a cohort of 12 students in 2020‑21, returning the program to its previous enrollment level.

Last Year, Legislature Expressed Intent to Approve a Future UC Merced Medical Facility. In addition to approving a UC Riverside medical school project, the 2019‑20 budget authorized UC to pursue a new medical school project at or near the Merced campus. As with the Riverside project, the language stated intent to increase UC’s General Fund support in future years to finance the project. To date, UC has not submitted a Merced facility proposal for the state to review.

Proposal

Provides $15 Million Ongoing for UCSF Fresno. Provisional language in the budget states the funds are available to support operational costs and expand services at UCSF Fresno, in partnership with UC Merced. Similar to the provisional language for the Riverside augmentation, provisional language for this augmentation states the funds shall supplement and not supplant existing funds provided by UC for the Fresno branch campus.

UC Plans to Submit More Detailed Proposal in March. In correspondence with our office, UC indicated that it would submit a more detailed budget of its expansion plans for UCSF Fresno in March. According to UC, its proposed budget will outline a somewhat different expansion plan than the three options described in the 2017 study. Under the revised plan, UC would develop a joint bachelor’s/medical degree program between UC Merced and UCSF. Students enrolled in the joint program would complete their four years of undergraduate studies at UC Merced. Students would then complete basic science medical school instruction at Merced and move to UCSF Fresno for their clinical rotations. According to UC, the program could serve as the foundation to eventually create an independent medical school at the Merced campus. UC states its initial plan is to enroll the first cohort of undergraduate students at UC Merced in 2022.

Assessment

Workforce Issues Are Similar to Those Raised by Riverside Proposal. Similar to the Inland Empire, the San Joaquin Valley is set to see growth in private medical school enrollment. Though the region currently has no medical schools, one new private school in Clovis plans to enroll its first cohort in 2020. The region also has experienced a notable rise in residency slots, with slots growing by 54 percent between 2015 and 2019. Analysis is lacking as to whether these recent developments are sufficient to address gaps in physician supply within the San Joaquin Valley. As with the Riverside proposal, the Legislature also would want to weigh the efficacy of medical school expansions against funding more residency slots or incentive programs.

Legislature Faces Complex Considerations. Were the Legislature to conclude that further expanding medical student enrollment in the region is warranted, it would want to decide how to undertake the expansion. The Legislature cannot fully assess the Governor’s proposal until it receives UC’s expansion plan. Ideally, such a plan would summarize available medical school expansion options, along with their associated annual operating and capital costs through full implementation. The plan also would offer alternative approaches to meeting regional workforce needs, including the possibility of increasing residency slots or physician relocation incentives. Additionally, any expansion plan should have an implementation time line that has projections of staffing and student enrollment. Even were the Legislature to receive a detailed budget plan in March, we question whether the Legislature would have adequate time to weigh such complex, costly, multifaceted, and impactful considerations prior to enacting the budget in June.

UC Riverside Experience Serves as a Warning. The Governor’s approach to expanding UCSF Fresno appears to share several disconcerting similarities to the state’s approach to establishing the UC Riverside School of Medicine. Similar to the approach taken for UC Riverside, the Governor proposes providing funding without first setting enrollment expectations, having a developed budget plan, or assessing facility needs. Furthermore, when our office asked the Department of Finance the basis for the proposed $15 million funding level, it noted that the state provided the same amount to UC Riverside in 2013‑14. Given UC Riverside’s previous implementation delays, current budget shortfalls, and notable cost pressures, we encourage the Legislature to take a more gradual, cautious, and vigilant approach to expanding UCSF Fresno.

Recommendations

Withhold Action Pending Comprehensive UCSF Fresno Expansion Plan. We recommend the Legislature withhold taking action on this proposal until it receives and has had time to carefully review any expansion plan that UCSF Fresno submits. At a minimum, we recommend the plan include:

- A summary of different options to expand the center, including prioritizing existing enrollment and clinical slots for San Joaquin Valley‑focused students, expanding UCSF Fresno into a four‑year branch campus, and establishing a joint program with UC Merced.

- For each option, a time line of planning activities, including staffing and enrollment levels and implementation deadlines.

- For each option, an estimate of the total operating cost and a multiyear expenditure phase‑in plan, along with revenue projections by source.

- A space and facility utilization analysis of UCSF’s main campus and the Fresno branch campus, along with a capital outlay plan under each option that identifies scope, cost, and schedule.

If the university is unable to provide this information by spring, the Legislature could create a reporting requirement (in provisional budget language or supplemental reporting language). We recommend selecting a due date for the report that is aligned with the legislative budget process. For example, were the Legislature interested in funding expansion in 2021‑22, it would want the UC report no later than November 2020.

Recommend an Oversight Hearing to Review and Discuss Any Expansion Plan. After receiving a comprehensive expansion plan, we recommend the Legislature hold an oversight hearing to vet the plan. We believe such a review is critical given the issues at stake are complex, potentially costly, and could have significant implications for people living in the region. As the Legislature carefully reviews the proposal, we would note that certain expansion efforts will already be underway in the region. With a new medical school opening and UCSF Fresno in the midst of increasing enrollment in the San Joaquin PRIME program, enrollment expansion will happen in 2020‑21 even without the Legislature approving further expansion efforts.