LAO Contact

February 25, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

The Governor’s Information Security Proposals

Introduction

One of the priorities of the Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget is to improve information security (IS) across state government entities. The proposed budget includes resource requests for the entities that govern IS for the entire state to increase their operational capacity, as well as resource requests for individual government entities to expand and improve their IS programs. This budget and policy post provides relevant information about state IS strategy to help the Legislature consider each of these requests. This post then summarizes the IS-related requests in the proposed budget. (We do not provide an in-depth analysis of any individual entity’s budget request in this post.) We focus the remainder of the post on findings and recommendations concerning constraints currently faced by the Legislature in evaluating IS-related budget requests. These constraints relate to the significant amount of information in support of these requests that is kept confidential by the administration and not made available to the Legislature.

Update on State IS Strategy

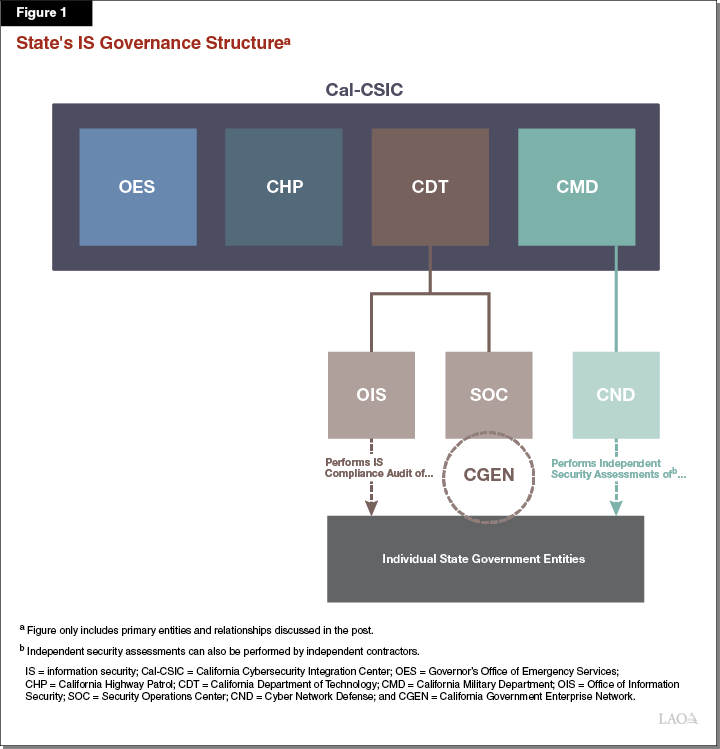

In this section, we provide relevant information about state IS strategy to help the Legislature consider IS-related requests in the Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget. We outline the state’s IS governance structure, discuss how state law and policy set IS standards and establish compliance and enforcement procedures, and describe some of the procedures the state uses to enforce IS compliance from individual state government entities.

Governance

California Cybersecurity Integration Center (Cal-CSIC). Cal-CSIC is a statewide joint operations center for IS activities with four core members—the California Department of Technology (CDT), the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (OES), the California Highway Patrol (CHP), and the California Military Department (CMD). Cal-CSIC is led by a Commander and Deputy Commander, both of whom are employed by OES. Each of the core members is responsible for different IS activities within the operations center. CMD, for example, assesses state government entity vulnerabilities and identifies potential threats. OES is responsible for coordinating the core partners’ response to an attack, CHP focuses on cybercrime investigations and evidence collection, and CDT assesses the vulnerabilities of entities’ networks and systems after they are attacked. Cal-CSIC interacts with a number of other state entities such as the OES State Threat Assessment Center—another partnership with some of the same core members responsible for threat analysis more broadly (inclusive of IS-related threats)—as well as the federal government (such as the United States Department of Homeland Security), local governments, and private sector entities.

CDT Office of Information Security (OIS). CDT OIS is responsible for the creation and enforcement of IS policies, standards, and procedures that many state government entities must follow. (Some entities are not under CDT’s authority for IS-related matters, such as constitutional offices, and are not required to follow the IS policies, standards, and procedures set by OIS.) Later in this post, we discuss some of the policies, standards, and procedures OIS sets through administrative policy.

CDT Security Operations Center (SOC). CDT also operates the SOC, which continuously monitors and reacts to threats on the California Government Enterprise Network (CGEN), the state government’s primary enterprise network. A number of state government entities connect to CGEN, which allows SOC to identify and respond more quickly to any attacks and/or threats to these entities. SOC also transmits any information about attacks and/or threats to Cal-CSIC to determine if, for example, other government and/or private sector entities are responding to similar attacks and/or threats.

CMD’s Cyber Network Defense (CND) Team. CMD’s CND team is comprised of National Guard personnel who, among other responsibilities, perform independent security assessments (which we discuss in more detail later in this post) of individual state government entities. The team, as part of CMD, also performs different IS activities within Cal-CSIC.

Individual State Government Entities. Daily IS-related activities, such as efforts to comply with state IS policies and standards and routine monitoring of local networks and systems, are performed by IS offices and programs across individual state government entities.

Figure 1 provides a graphic showing the multiple players in the state’s IS governance structure.

State Law and Policy

Cal-Secure. CDT’s OIS recently released the draft of the executive branch’s first five-year IS maturity roadmap—Cal-Secure—in collaboration with the other core members of Cal-CSIC. According to the administration, Cal-Secure is intended to be used by state government entities to inform their own IS roadmaps and strategies. Cal-Secure identifies three main priorities that, according to the administration, will improve the executive branch’s cybersecurity maturity and identify and manage risks to the state. The three priorities (at a high level) are (1) a “world-class” cybersecurity workforce developed through improved recruitment and training efforts, (2) a more unified cybersecurity oversight structure with state government agencies setting and enforcing more IS policies and processes for individual entities under the agencies’ purview, and (3) effective cybersecurity defenses that meet (at a minimum) baseline requirements set by the administration.

State Law. State law establishes CDT’s OIS, and directs the Chief Information Security Officer (who leads OIS) to establish the state’s IS program. Some program responsibilities for CDT’s OIS include making sure independent security assessments (that we explain later in this post) are conducted for at least 35 state government entities each year; conducting audits of entities’ compliance with IS policies, standards, and procedures as needed; and ranking of entities on an IS risk index based on a number of criteria, such as the sensitivity of the data they maintain.

State Administrative Policy. CDT establishes IS policies, standards, and procedures through the State Administrative Manual (SAM)—a reference manual authored by a number of control agencies such as the Department of Finance and the Department of General Services—and the Statewide Information Management Manual (SIMM)—a collection of forms, instructions, and templates managed by CDT for state government entities to use for IS compliance (among other uses). Several of the IS policies in SAM and procedural elements in SIMM are informed by IS standards, guidelines, and practices set by the federal government, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s cybersecurity framework.

Compliance and Enforcement

State Government Entity Risk. CDT’s OIS uses a number of criteria to determine whether state government entities that are under its authority are a higher IS risk to the state or a lower IS risk. (Criteria include, for example, the sensitivity of the data the entities maintain.) Whether an entity is higher or lower risk to the state largely determines how often they are required to be subject to an IS compliance audit (which we discuss later in more detail). All entities are expected to undergo independent security assessments biennially, but entities that are a higher IS risk to the state also are expected to undergo some form of IS compliance audit biennially (alternating with their independent security assessments). Lower-risk entities can self-certify their compliance with IS policies and standards, but may be subject to an IS compliance audit at some point. All entities with identified IS deficiencies also are required to submit plans of action and milestones (which we discuss later in more detail) that must be updated on a quarterly basis to CDT.

IS Compliance Audits. In an IS compliance audit, CDT reviews whether a state government entity under its authority is compliant with state IS policy and standards. Auditors request documentation from the entity, such as risk management plans, to perform an initial assessment of the entity’s compliance. Then, auditors perform field work, such as interviews with entity staff and testing of the networks and systems used by the entity. A final report is issued to the entity with findings of non- or partial compliance with state IS policies, standards, and/or procedures that require corrective action. All of the documentation from, and results of, an IS compliance audit are not made public.

Independent Security Assessments. In an independent security assessment, CMD’s CND team or (in some cases) an independent contractor perform a technical analysis of a state government entity’s cybersecurity defenses. The CND team, for example, assesses (1) whether an entity’s networks and/or systems are configured to prevent attacks and/or threats, and (2) simulates attacks and/or threats to see whether an entity’s networks and/or systems can be compromised or its data modified and/or stolen. A final report also is issued to the entity with findings of non- or partial compliance with state IS policies, standards, and/or procedures that require corrective action. All of the documentation from, and results of, an independent security assessment are not made public.

Plan of Action and Milestones. IS compliance audits and independent security assessments (and other possible assessments and audits) inform a state government entity’s plan of action and milestones. The plan of action and milestones identifies risks—a term used broadly to describe assessment and audit findings as well as activities underway to address security incidents—and requires entities to describe any short- or long-term controls needed to address the risks. If there are reasons why the entity cannot address the risk, such as a lack of available resources, entities are required to describe those constraints. At a minimum, state entities under CDT’s authority must submit to OIS quarterly updates to their plans of action and milestones and demonstrate progress towards the remediation of their identified risks. All plans of action and milestones are not made public.

Cybersecurity Maturity Metrics. In March 2018, CDT’s OIS introduced the California Cybersecurity Maturity Metrics to, according to the administration, objectively measure the effectiveness of IS programs at each state government entity under its authority (including the use of budgeted IS resource allocations). CDT’s OIS expects each entity to receive a cybersecurity maturity score, which is calculated based on a complex formula that uses various information sources (including IS compliance audits and independent security assessments) to score the entity on each metric. The administration expects to update the metrics on a four-year cycle to both allow year-over-year comparisons and to accommodate changes in the nature of attacks and/or threats as well as technology. It is our understanding from the administration that cybersecurity maturity scores will not be made public.

Governor’s 2020‑21 IS Proposals

The Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget includes 20 requests for resources to improve IS across state government entities, three of which would increase the operational capacity of entities that govern IS for the entire state. We provide a listing of all 20 requests and details on the three requests of statewide application. We also describe proposed statutory language that, if approved, would change how the state pays for CDT’s IS compliance audit program.

Governor’s Proposed Budget Includes a Total of 20 Requests for IS-Related Resources. The Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget includes 20 requests for IS-related resources with a total cost of $40.8 million (a majority of which is General Fund) in 2020‑21. (This total ramps down to about $30.4 million in 2021‑22 and ongoing.) Figure 2 lists these requests by state entity and budget proposal.

Figure 2

Governor’s 2020‑21 Proposed Budget Requests for IS‑Related Resourcesa

(In Thousands)

|

State Government Entities |

Budget Proposal |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Total Funds |

General Fund |

||

|

California Department of Technology (CDT) Highway Patrol Military Department Office of Emergency Services |

California Cybersecurity Integration Center |

$11,061 |

$11,061 |

|

Department of Food and Agriculture |

Information Technology Workload Growth and Sustainabilityb |

5,372 |

2,462 |

|

Department of Technology |

Statewide Endpoint Protection Platform |

5,069 |

5,069 |

|

Department of Human Resources |

Departmental Data Solutionsb |

4,223 |

2,197 |

|

Correctional Health Care Services |

Information Technology Security Staffing and Tools |

2,888 |

2,888 |

|

High‑Speed Rail Authority |

IT Office Restructuringb |

2,634 |

— |

|

Department of Consumer Affairs |

Information Technology Security |

2,004 |

— |

|

Department of Public Health |

Cybersecurity Program Augmentation |

1,900 |

— |

|

Public Utilities Commission |

Information Security Office Resources |

1,492 |

— |

|

Department of Social Services |

Protecting Data and Systems |

1,043 |

1,043 |

|

Department of Business Oversight |

Information Technology Security Workload |

780 |

— |

|

Department of Rehabilitation |

Systems and Privacy Protections |

670 |

670 |

|

Public Utilities Commission |

Cyber and Physical Security |

405 |

— |

|

Department of Managed Health Care |

Information Security Resources |

384 |

— |

|

Department of Developmental Services |

Information Security Office |

293 |

234 |

|

Secretary of Statec |

IT Division Resources Workload Growth |

293 |

79 |

|

Air Resources Board |

Monitoring and Laboratory Division and Information Services Program Support |

172 |

— |

|

Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission |

Contract and Information Technology Workload |

144 |

— |

|

Department of General Services |

Enterprise Technology Solutions Workloadd |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$40,827 |

$25,703 |

|

|

aThere is an additional proposed budget request from CDT—Security Operations Center and Audit Program. The request would shift the funding source for the Security Operations Center and Audit Program from CDT’s Technology Services Revolving Fund to the General Fund. The request (if approved) does not increase total spending, but does increase the General Fund appropriation for CDT by $15.1 million in 2020‑21 and ongoing. bSome portion of this budget request, not the entire amount reflected here, is for IS‑related activities. cSecretary of State, as a constitutional office, is not under CDT’s authority. dThe Department of General Services is not requesting expenditure authority because the cost of the requested positions can be absorbed by existing funding from previously approved budget requests. |

|||

|

IS = information security and IT = information technology. |

|||

Three Requests for Entities That Govern IS for the Entire State. Three of the IS-related resource requests would increase the operational capacity of entities that govern IS for the entire state, as described below.

Cal-CSIC. A request from the four core Cal-CSIC partners—CDT, OES, CHP, and CMD—for $11.1 million General Fund in 2020‑21 and ongoing to expand on their existing roles within Cal-CSIC (as described previously) and to add a number of resources that will be shared by the partners to respond more quickly to IS-related incidents, such as mobile hardware and software.

SOC and Audit Program. A request from CDT to shift the funding source for its SOC and IS compliance audit program from its cost recovery fund (the Technology Services Revolving Fund) to the General Fund. This proposal would not increase total state spending, but would increase the General Fund appropriation for CDT by $15.1 million in 2020‑21 and ongoing. The intent of the administration (as reflected in proposed statutory language detailed later in this post) is to allow state government entities to use funding they currently have budgeted for IS compliance audits and the SOC (that would be deposited into CDT’s cost recovery fund) to remediate identified IS deficiencies. The administration is also proposing statutory changes related to the audit program (which we describe later in more detail).

Statewide Endpoint Protection Platform. A request from CDT for $5.1 million General Fund in 2020‑21 to cover the initial (annual) licensing costs of IS-related technical solutions for a number of state government entities the administration identified (through, for example, assessments and audits) as needing the solutions. According to the administration, entities that use the solutions will need to cover their ongoing licensing costs after 2020‑21.

Proposed Statutory Language Would Allow General Fund Expenditures for IS Compliance Audits Performed by CDT. The administration also is proposing statutory language that would repeal the requirement that state government entities audited by CDT are required to fund the cost of the audit and instead allow General Fund to be used for this purpose. We understand that the intent of the administration is to allow entities to use the funding they currently have budgeted for CDT audits to remediate deficiencies in their IS programs. (The proposed language does not repeal this requirement for independent security assessments, so entities assessed by CMD’s CND team, for example, will still be required to fund the cost of their assessments.)

Findings

Limited Information Available for Legislature to Evaluate IS-Related Resource Requests. Many of the state government entities with requests for IS-related resources in the Governor’s proposed 2020‑21 budget justified the amount of funding and number of positions they requested by citing that there were some relevant findings from IS assessments and audits pertaining to them, as well as relevant risks from their plans of action and milestones that were informed by the assessments. Importantly, the findings and risks themselves were not disclosed in the proposals.

While the administration is in a position to assess whether the resources that entities requested would help address these findings and risks, the Legislature is not because the administration keeps the overall assessment (and the underlying findings and risks) confidential. We understand that the administration keeps this information confidential to protect entities from possible attacks. We appreciate the administration’s interest in protecting entities from attack, but also question how the Legislature can effectively evaluate on IS-related resource requests without at least some of the information that forms the basis for the request.

Specifically, the Legislature does not have information that shows if/how the administration prioritizes among the IS-related requests it receives from multiple entities. From our meetings with a number of the entities that are requesting IS-related resources in 2020‑21, it appears that entities received varying direction and levels of engagement from CDT in regards to their budget requests. Some entities, for example, treated their plans of action and milestones as mandates from the administration that required them to request additional resources. Other entities cited some findings and risks in support of their request, but also seemed to suggest during our meetings that they had only received limited direction from the administration on their request. These observations from our meetings appear to suggest that CDT may not have consistently and clearly articulated its priorities for funding IS-related budget requests.

The Legislature also does not have clear metrics from the administration to evaluate whether the requested resources are improving the overall maturity of entities’ IS programs. For example, how much the cybersecurity maturity score of an entity would increase because of the requested additional resources is unknown. There also is no baseline against which to compare an entity’s score, both for the entity itself and for entities of comparable risk and/or size, meaning that what score an entity should be aiming for is undefined.

Proposed Statutory Language Does Not Require Entities to Use Previously Budgeted Audit Funding to Remediate IS Deficiencies as Intended by Administration. As noted, we understand that the intent of the statutory language proposed by the administration is to allow state government entities to use funding they previously budgeted for CDT IS compliance audits to remediate deficiencies in their IS programs. While we think that the intent of the administration has merit, the administration’s intent is not reflected in the text of the proposed language. Instead, the administration anticipates meeting with individual IS officers to make sure previously budgeted audit funding is used as intended. Whether this approach is a feasible way of conveying this intent given the large number of entities under CDT’s authority is unclear. Moreover, given the confidential nature of IS-related activities, absent this language, the Legislature has no means of ensuring funds are used in this manner.

Some Entities Requesting IS-Related Resources Are Not Subject to IS Oversight Governance Structure. Some state government entities that are requesting IS-related resources in 2020‑21 are not under CDT’s authority and, therefore, are not subject to the IS oversight governance structure we described. The California State Auditor recently released a report showing a majority of entities they surveyed that are not under CDT’s authority were (1) only partially compliant with a number of federal and state IS standards, and (2) had a number of high-risk deficiencies. If some entities are not required to meet the state’s IS standards and are not subject to the state’s IS oversight governance structure, the entities might compromise the state’s IS strategy and limit the effectiveness of the resources requested in the budget.

Recommendations

Adopt Supplemental Reporting Language Requiring CDT to Evaluate Options to Provide Legislature With More Information to Consider IS-Related Resource Requests. Without at least some of the information from the assessments, audits, and related documentation that—as a package of information—currently is kept confidential by the administration, the Legislature cannot effectively evaluate IS-related resource requests. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature consider requiring CDT to determine what type of information the administration could feasibly share with the Legislature (both confidentially and publicly), and present several options for the Legislature to consider in a format specified through supplemental report language (SRL). We recommend that the SRL specify that the options should address the Legislature’s interest in receiving (1) information from the administration showing how it prioritizes IS-related requests from different entities, and (2) clear metrics from the administration that can show whether requested resources are improving the maturity of entities’ IS programs.

Adopt Revisions to Statutory Language That Requires Previously Budgeted Audit Funding Be Used to Remediate IS Deficiencies. We recommend the Legislature adopt revisions to the administration’s proposed statutory language to require state government entities to use their previously budgeted audit funding to remediate IS deficiencies identified by the administration through its IS oversight governance structure. These revisions would ensure this funding will be used to improve the maturity of entities’ IS programs, which we find has merit.

Consider Statutory Language That Require State’s Entities Not Under CDT’s Authority to Follow State’s IS Standards and Be Subject to IS Oversight Governance Structure. State entities that are not required to meet the state’s IS standards and are not subject to the state’s IS oversight governance structure could compromise the state’s IS strategy. Without common IS standards that every entity follows and a common oversight governance structure to enforce the standards, the administration and Legislature cannot be confident that entities not under CDT’s authority are effectively mitigating their IS risks. Limited visibility into the IS programs of these entities also means attacks and/or threats could occur without a coordinated response within the administration. We therefore recommend the Legislature consider statutory language that would require these state entities to follow state IS standards (or comparable standards) and be subject to a similar IS oversight governance structure.