February 28, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Re-Envisioning Medi-Cal—The CalAIM Proposal

- Introduction

- Background

- Overview of CalAIM

- Governor’s 2020‑21 Budget Proposal to fund CalAIM

- LAO Assessment

- Key Takeaways From Our Assessment

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Overview of the Governor’s Proposal

Administration Proposes Reforms Collectively Known as California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM). In October 2019, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) released a far‑reaching set of Medi‑Cal reforms collectively now referred to as CalAIM. These reforms are intended to address longstanding challenges in Medi‑Cal. CalAIM (formerly known as “Medi‑Cal Healthier California for All”) proposes reforms in the following areas:

- Increase the Focus on Medi‑Cal’s High‑Cost, High‑Risk Enrollees. CalAIM aims to improve care coordination and provide a broader suite of supportive services to Medi‑Cal members with the most complex needs. Specifically, DHCS proposes to (1) coordinate care through a new “enhanced care management” benefit and (2) provide an the optional suite of “in lieu of services” (ILOS) (such as temporary housing assistance) as alternatives to traditional, and often more expensive, Medi‑Cal benefits.

- Transform and Streamline Medi‑Cal Managed Care. DHCS proposes a number of changes to the managed care delivery system, including (1) moving certain benefits, such as long‑term care, out of Medi‑Cal’s fee‑for‑service delivery system and into managed care; (2) setting payment levels for managed care plans on a more regional as opposed to county‑by‑county basis; and (3) considering a full‑integration pilot whereby one or more Medi‑Cal managed care plans would not only offer the standard set of physical health services, but also dental services, mental health services, and substance use disorder services (the last two of which together are known as “behavioral health services”).

- Extend Components of a Current Federal Waiver. Currently, the state operates much of Medi‑Cal under a federally granted Section 1115 waiver, which allows the state to obtain federal funding that might not otherwise be available. Under CalAIM, the state generally would continue programs that are under the current 1115 waiver, such as funding for public hospitals and an expansion of substance use disorder services.

- Rethink How Behavioral Health Services Are Financed and Delivered. The CalAIM proposal includes a number of proposed reforms to improve service delivery for county behavioral health, including streamlining its financing, exploring new federal funding opportunities for residential care, integrating behavioral health services at the local level, and changing eligibility rules so more beneficiaries can receive behavioral health services.

Many Details of CalAIM Proposal Under Development. At the time of the release of this report, many of the details of the administration’s CalAIM proposal remain in development. Accordingly, this report provides our assessment of the CalAIM proposal as it evolved at the time our report was prepared (January through late February 2020).

Governor Proposes $348 Million General Fund to Implement CalAIM in 2020‑21. The Governor’s budget proposes $348 million General Fund ($695 million total funds) for CalAIM for a half year of implementation in 2020‑21. On an ongoing basis, the Governor projects annual costs of $395 million General Fund ($790 million total funds).

LAO Assessment

In Concept, the Approach of CalAIM Appears Promising… CalAIM would expand on the vision of managed care in the Medi‑Cal program, giving Medi‑Cal managed care plans additional tools to address the broad needs of their beneficiaries. In addition, CalAIM would provide new opportunities to receive federal Medicaid funding for services not previously eligible, including for temporary housing assistance and recuperative care. In some ways, the proposal also would move Medi‑Cal toward greater standardization across the state and reduce some complexity. Finally, the behavioral health reforms could improve service delivery by removing barriers to accessing Medi‑Cal services and reduce the administrative burden on counties associated with the current financing structure.

…However, the Proposal Also Raises Many Questions and Presents Risks. While the CalAIM proposal could bring many benefits, the reform proposal also raises many outstanding questions and presents a number of risks. Some key questions relate to (1) the readiness of Medi‑Cal managed care plans for their significantly expanded responsibilities under the proposal; (2) likely difficulties the state and plans would face ensuring that new benefits—particularly the new ILOS benefits—are cost‑effective, presenting possible fiscal risks to the state; (3) how new benefits would expand the supply of already limited services; (4) how new benefits would interact with existing services; and (5) how the state could minimize new complexities the proposal could introduce.

Key Takeaways From Our Assessment

As Details of Proposal Remain Under Development, Focus on Resolving Key Questions. The CalAIM proposal continues to evolve. As of this publication’s release, the administration has not submitted any trailer bill or statutory language for the proposal. This makes providing specific direction on the actions we would recommend the Legislature to take on the proposal difficult. Instead, we suggest that the Legislature primarily focus on resolving key questions about the proposal prior to taking action on it. These questions are summarized in Figure 8 toward the end of the report.

Explore Where Delays in Implementation May Be Possible and Advisable. CalAIM is far‑reaching and the time line for implementation is aggressive. Given (1) the significant actions the state and managed care plans would have to take in the near future to implement CalAIM as proposed and (2) the risks that unplanned delays could present, we recommend that the Legislature explore whether some components of CalAIM could be delayed. While delays may not be feasible in some cases due to the need to have new federal waivers in place beginning in 2021, some elements of the proposal could be postponed or implemented in phases.

Closely Consider and Ensure Measures Are in Place to Mitigate Potential Fiscal Risks of CalAIM. In deciding which components of the Governor’s CalAIM proposal ultimately to approve, we recommend that the Legislature consider (1) the potential for CalAIM to result in significantly higher costs on an ongoing basis than is currently assumed by the administration, (2) what fiscal transparency measures are needed to ensure that the Legislature can know how much is being spent on CalAIM on an ongoing basis, and (3) what policies should be put in place at the outset to mitigate the potential fiscal risks of CalAIM.

Ensure Robust Legislative Oversight and Evaluation of Any Reforms Ultimately Adopted. Legislative oversight of CalAIM implementation will be critical to ensuring smooth and successful implementation. In addition, in order to understand the impacts of CalAIM, we recommend that the Legislature establish a framework for an independent and robust evaluation of whichever major components of the CalAIM proposal ultimately are adopted.

Introduction

In October 2019, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) released a broad set of Medi‑Cal reform proposals that now are collectively referred to as CalAIM (California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal). We note that when these proposals were presented to the Legislature in the January budget, they were at that time collectively referred to as Medi‑Cal Healthier California for All. The proposals are intended to address longstanding challenges in Medi‑Cal, such as the disproportionately high cost of services provided to a relatively small number of beneficiaries with high needs as well as significant variation and complexity in how services are delivered throughout the state. These proposals are complex and would affect nearly all aspects of the Medi‑Cal program. As part of CalAIM, the administration has convened a series of stakeholder workgroups through which DHCS is receiving feedback on the various proposals. Ongoing discussions through the workgroup process are likely to affect the details of the overall proposal while it is under legislative consideration. Other components of the overall proposal could be the subject of legislative deliberations in the policy bill process. This report provides our assessment of the CalAIM proposal as of the point in time that our report was prepared.

This report is laid out as follows. First, we provide some high‑level background on Medi‑Cal. Second, we describe the major components of the CalAIM proposal, including funding proposed to implement CalAIM. Third, we assess the opportunities and challenges of the proposal. Finally, we conclude with key takeaways from our assessment.

Background

Medi‑Cal Provides Care to Some Individuals With Complex and Costly Conditions

Medi‑Cal Provides Health Care Services for Nearly One‑Third of Californians. Medi‑Cal, California’s Medicaid program, provides health care services for the state’s low‑income residents. Medi‑Cal is the single largest provider of health care coverage and services in the state, covering nearly 13 million people, or roughly one‑third of the state’s total population. About one‑half of children in the state are enrolled in Medi‑Cal.

Medi‑Cal Provides a Range of Health Care Benefits and Services… Medi‑Cal provides a comprehensive set of health care benefits and services. Key benefits include primary care, other outpatient services, inpatient services, emergency services, maternity and newborn care, mental health and substance use disorder services (together referred to as “behavioral health” services), prescription drugs, rehabilitative services, dental services, and long‑term care (predominantly in skilled nursing facilities, or SNFs).

…To a Variety of Populations. Key Medi‑Cal populations include families with children (about 7 million), seniors aged 65 or older (about 1 million), persons with disabilities (about 1 million), and childless adults (about 4 million) who are part of the eligibility expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

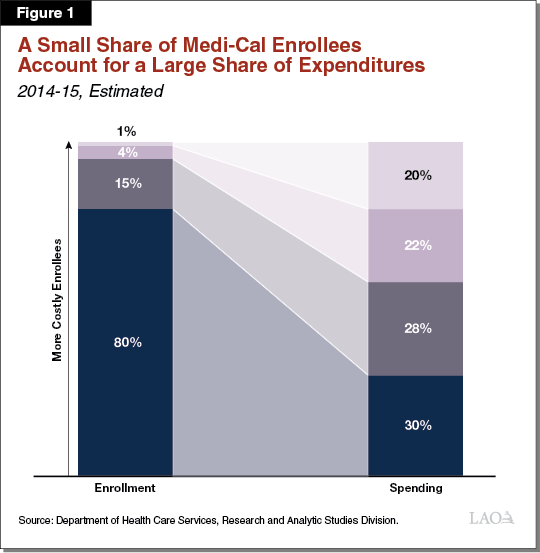

A Small Number of Enrollees With Complex Needs Account for a Large Portion of Overall Medi‑Cal Spending. Medi‑Cal enrollees are diverse and have varying health statuses. The cost of Medi‑Cal services per enrollee varies significantly and a small number of Medi‑Cal enrollees account for a large and disproportionate share of total spending in Medi‑Cal. As shown in Figure 1, the most costly 1 percent of Medi‑Cal enrollees accounts for about 20 percent of program spending and the most costly 20 percent of Medi‑Cal enrollees account for about 70 percent of program costs.

Certain factors have been identified that are related to an enrollee having disproportionately high costs in Medi‑Cal. Past research indicates that the highest‑cost enrollees typically are being treated for multiple chronic conditions (such as diabetes or heart failure) and often have mental health or substance use disorders. Costs for this population often are driven by frequent hospitalizations and high prescription drug costs. In some cases, social factors like homelessness play a role in the high utilization of these enrollees. Costs are also high for individuals residing in long‑term care facilities, the annual costs of which can be about $90,000 for someone who resides in a SNF for an entire year. Costs for individuals residing in long‑term care facilities could potentially increase in coming years as the state’s population ages.

Medi‑Cal Is Complex

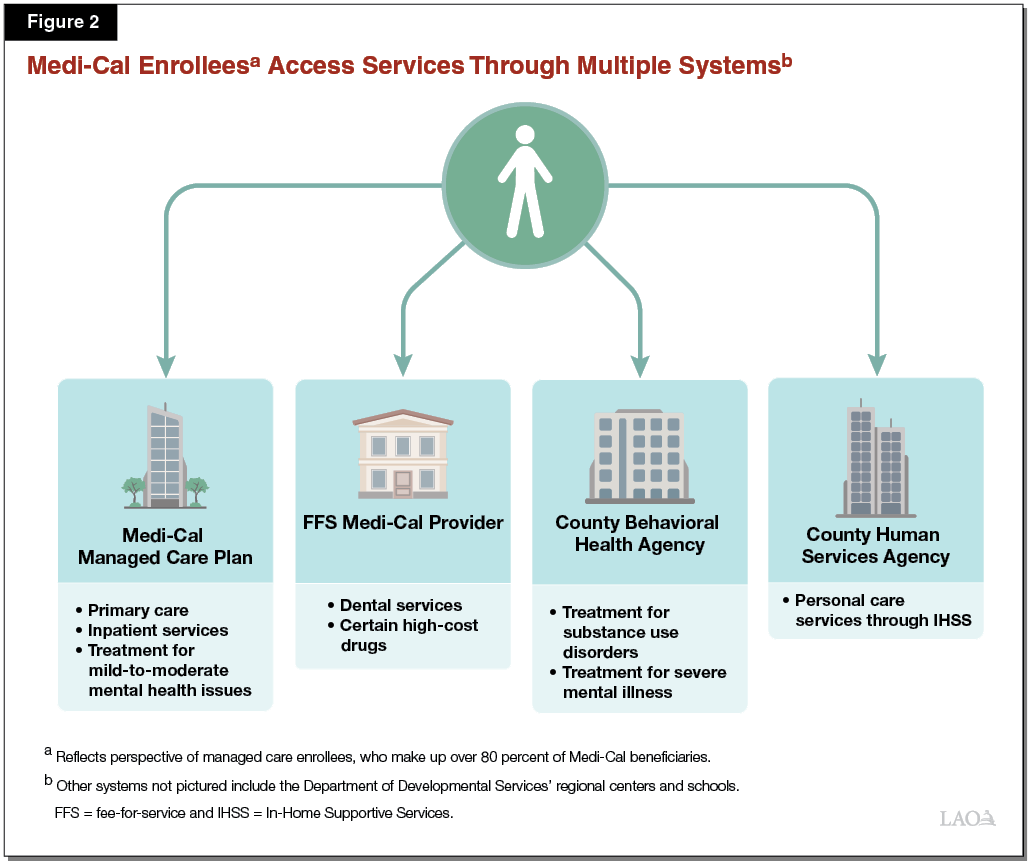

Medi‑Cal Services Are Provided Through a Variety of Delivery Systems. Medi‑Cal is large and complex. As shown in Figure 2, services in the program are delivered through a variety of systems:

- Managed Care. Managed care is one of the two main Medi‑Cal delivery systems. In managed care, the state contracts with managed care plans (including some commercial for‑profit, commercial not‑for‑profit, and government‑sponsored plans) to provide a network of health care providers though which Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who enroll with the managed care plan receive services. Plans receive a monthly payment, or “capitated rate,” per beneficiary to cover the cost of their care. Currently, over 80 percent of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are enrolled with a managed care plan for their Medi‑Cal benefits, with estimated total expenditures of nearly $48 billion in 2019‑20. While the benefits provided through managed care vary somewhat in different counties as we describe later, in general, a wide range of benefits are provided through managed care, including primary care and other outpatient services, inpatient services, and treatment for mild‑to‑moderate mental health conditions.

- Fee‑for‑Service (FFS). FFS is the second main delivery system. In FFS, Medi‑Cal beneficiaries may receive services from any health care provider that accepts Medi‑Cal, rather than choosing a provider from within a managed care plan’s network. Because most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care, a relatively small proportion of beneficiaries obtain general services like primary care and inpatient care through FFS. However, certain services are provided mostly or exclusively through FFS. Such benefits are sometimes referred to as being “carved out” of managed care, because they are not available through the state’s Medi‑Cal managed care plans. One example of such a benefit is dental services, which are predominantly provided in FFS. Estimated expenditures in FFS total $27 billion in 2019‑20.

- County Specialty Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment. While managed care plans are responsible for providing treatment for mild‑to‑moderate mental health conditions, treatment for more severe mental health conditions is carved out of managed care and is the responsibility of counties. These county services are often referred to as “specialty mental health.” Counties also are responsible for providing substance use treatment services in much of the state. In many cases, a single county behavioral health agency administers services for both severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Estimated expenditures on county specialty mental health and substance use services total roughly $5.4 billion in 2019‑20.

- In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS). The IHSS program allows persons with disabilities to hire a worker to provide personal care services, such as help with dressing, bathing, and household work. This is intended to enable persons with disabilities to remain in their homes. IHSS is administered at the state level by the Department of Social Services. However, it is almost entirely funded as a Medi‑Cal benefit and is by far the largest Medi‑Cal‑funded, community‑based, long‑term services and support benefit available in the state, with estimated total funding of about $13 billion in 2019‑20. Individuals apply to receive IHSS services and manage their benefit through a county human services agency.

Structure and Availability of Benefits and Service Delivery Varies Across the State. Medi‑Cal benefits are not always provided through the same delivery system in all parts of the state, and not all benefits are available everywhere in the state. This variation largely is the result of past efforts to test new models of care in only portions of the state. Several examples of this variation include:

- The SNF long‑term care benefit is a managed care benefit in more than half of counties but is an FFS benefit in the remaining counties.

- Seven counties in the state that participated in the Coordinated Care Initiative have specialized managed care plans—referred to as “Cal MediConnect” (CMC) plans—that integrate Medi‑Cal and Medicare benefits for seniors and persons with disabilities that are dually eligible for both programs.

- 38 counties have opted in to the Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System (DMC‑ODS) program, under which counties provide a more comprehensive substance use benefit than is otherwise available in Medi‑Cal.

- 24 counties and one city have opted in to the Whole Person Care program, which is testing local initiatives that coordinate physical health, behavioral health, and social services for beneficiaries who are high users of health care and other services.

- 12 counties are participating in the Health Homes Program, which has similar goals to the Whole Person Care program and provides extra services to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries that have chronic health and/or mental health conditions that results in high utilization.

Medi‑Cal’s Complexity Puts Burdens on Beneficiaries and Program Administrators. The complexity of the Medi‑Cal program impacts both beneficiaries and the state in its oversight and administration of Medi‑Cal. Depending on which services beneficiaries require, they may need to navigate multiple delivery systems, which can make it difficult for beneficiaries to receive all the services that their conditions would indicate are needed. Difficulties navigating Medi‑Cal’s multiple systems can be particularly pronounced for individuals with multiple complex conditions. The complexity of the program also increases administrative workload for DHCS as it develops policy and guidance, provides technical assistance, and provides funding for the large variety of benefit and delivery system combinations present throughout the state.

Many Key Medi‑Cal Program Features Are Authorized Through Federal Waivers

Medicaid Waivers Provide States Flexibility to Test New Approaches to Delivering Services. Federal law lays out many basic requirements for how states may operate Medicaid programs and requires states to offer certain benefits. Federal law also allows the federal government to waive certain Medicaid requirements in some cases. States often take advantage of federal waivers to provide Medicaid benefits in new ways and, in some cases, obtain funding for services that might not otherwise be available. The CalAIM proposal affects two waivers in particular:

- Section 1115 Waivers. Section 1115 waivers provide broad authority to allow states to (1) expand eligibility for benefits beyond those who typically would be eligible under federal law; (2) provide additional services not traditionally available under Medicaid; and (3) use different delivery systems, such as managed care, that are intended to provide care more efficiently. (The federal government now discourages using 1115 waivers to implement managed care delivery systems in light of other waivers being available for this purpose, as described shortly hereafter.) Changes approved under 1115 waivers are required to be cost‑neutral to the federal government. In the past, the state has been able to justify to the federal government that changes included in the waiver—primarily moving Medi‑Cal populations into managed care—save money for the federal government. In turn, the federal government returned at least a portion of these savings to the state for new services and program improvement initiatives also approved under the state’s 1115 waiver.

- Section 1915(b) Waivers. Section 1915(b) waivers are more narrow and essentially allow states to provide Medicaid benefits through a managed care delivery system instead of through FFS, or more generally to allow benefits to vary in different regions of a state.

Key Medi‑Cal Benefits and Services Operate Under Waivers. The state currently has 1115 and 1915(b) waivers for significant components of the Medi‑Cal program. As already noted, the state’s 1115 waiver provides the authority for the state to provide core Medi‑Cal services through managed care. The current 1115 waiver also includes:

- The Public Hospital Redesign and Incentives in Medi‑Cal (PRIME) program, which provides incentive payments tied to the state’s public hospitals meeting certain quality and efficiency targets.

- The Global Payment Program, which repurposes federal funding for uncompensated care at public hospitals to an incentive‑based structure that encourages hospitals to provide preventive care in order to try to avoid the need for acute care.

- The Dental Transformation Initiative, which is intended to improve access to dental services for children with Medi‑Cal coverage. Under the program, dental providers receive payments for meeting performance benchmarks related to the provision of preventive dental care and continuity of coverage. (The current waiver allows the state to claim state expenditures on other state health programs as the nonfederal share of cost for the Dental Transformation Initiative, allowing this waiver program to be funded largely exclusively with federal funding for Medi‑Cal.)

- The Whole Person Care program, described earlier, allows participating counties to receive funding to coordinate and provide health, behavioral health, and social services for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who have high utilization of multiple systems of care and have poor health outcomes.

- The DMC‑ODS program, described earlier, allows the state to receive federal reimbursement for an array of substance use disorder treatments, including those provided in an Institution for Mental Disease (IMD), which are defined as residential mental health facilities with more than 16 beds that normally are not eligible for federal funding. Participation in DMC‑ODS is optional for counties.

Specialty mental health services have been carved out of managed care under the 1915(b) waiver.

Current Major Medi‑Cal Waivers Are Set to Expire. The state’s 1115 waiver is set to expire at the end of 2020. (A few programs included in the wavier have other expiration dates. For example, the Global Payment Program expires in July 2020.) The state’s 1915(b) waiver expires in July 2020, but the state applied to the federal government to extend waiver authority six months to align with the expiration of the 1115 waiver. Because these waivers are expiring, the state must seek renewal of these waivers or explore other options to gain federal authority if it wishes to continue the program features described previously.

Overview of CalAIM

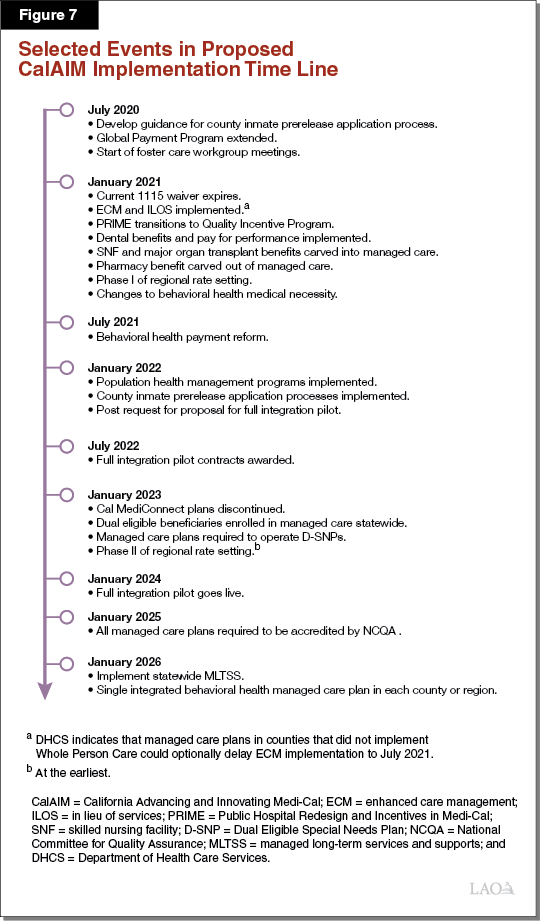

At a high level, CalAIM is intended to address some of the challenges identified previously by (1) providing more comprehensive benefits and services to high‑risk and high‑cost populations and (2) streamlining and standardizing Medi‑Cal benefits and administration. The proposal further seeks to promote quality of care and positive health outcomes through payment reforms. Finally, the CalAIM proposal addresses the upcoming expiration of the state’s 1115 and 1915(b) waivers. Many, but not all, of the changes proposed under CalAIM would be implemented through the 1915(b) waiver. In this section, we provide a high‑level overview of the major components of CalAIM, summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Major Policy Reforms Under CalAIM Proposal

|

Increasing the Focus on High‑Risk, High‑Cost Populations |

|

Create new enhanced care management benefit. |

|

Ensure enrollment assistance for individuals transitioning from incarceration. |

|

Provide new nonmedical “in lieu” benefits. |

|

Require managed care plans to develop population health management programs. |

|

Convene foster care workgroup. |

|

Transforming and Streamlining Managed Care |

|

Transition certain Medi‑Cal benefits into managed care statewide. |

|

Transition certain benefits out of managed care statewide. |

|

Modify approach to coordinating care of beneficiaries eligible for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare. |

|

Set capitated rates on a regional rather than county basis. |

|

Require NCQA accreditation of Medi‑Cal managed care plans; deem as meeting most federal and state standards. |

|

Consider creation of a full‑integration pilot. |

|

Extending Components of the Current 1115 Waiver |

|

Continue public hospital funding under other programs. |

|

Maintain expansion of substance use disorder services begun under DMC‑ODS. |

|

Extend statewide components of Dental Transformation Initiative. |

|

Rethinking Behavioral Health Service Delivery and Financing |

|

Streamline behavioral health financing. |

|

Explore federal funding opportunities for residential care. |

|

Change medical necessity criteria for beneficiaries to access services. |

|

Implement “no wrong door” approach for children obtaining mental health services. |

|

Integrate county administration of specialty mental health and substance use disorder services. |

|

CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal; NCQA = National Committee on Quality Assurance and DMC‑ODS = Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System. |

Increasing the Focus on High‑Risk, High‑Cost Populations

The CalAIM proposal reflects an increased focus on the small portion of beneficiaries with high needs that accounts for a high portion of overall spending in Medi‑Cal. These beneficiaries may have complex care needs that include issues related to homelessness, behavioral health, or criminal justice involvement. These beneficiaries also need to navigate multiple health care delivery systems to receive the care they need. To improve services for this population, the administration is proposing new Medi‑Cal benefits that we describe in the following sections.

Create New Enhanced Care Management (ECM) Benefit. To assist high‑need beneficiaries with navigating Medi‑Cal’s delivery systems, DHCS is proposing a new statewide ECM benefit. This benefit would be modeled after services currently provided in the Health Homes Program and the care coordination services provided through the Whole Person Care pilots. The new ECM benefit would be administered by the Medi‑Cal managed care plans, which would be tasked with establishing care management programs for their members and contracting with providers to deliver care. The benefit would be targeted at high utilizers of hospital inpatient stays and emergency room visits; individuals at risk of institutionalization in IMDs or SNFs; individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness; individuals transitioning from incarceration; and children with complex physical, behavioral, and developmental needs. The ECM benefit would be implemented beginning in January 2021.

Ensure Enrollment Assistance for Individuals Transitioning From Incarceration. Currently, there is variation among counties in the extent to which they enroll individuals transitioning from jails in Medi‑Cal. DHCS proposes making inmate pre‑release application processes mandatory statewide beginning in January 2022.

Provide New Nonmedical “In Lieu” Benefits. Under federal rules, “in lieu of services” (ILOS) are generally nonmedical services that can be provided as alternatives to standard Medicaid benefits in the managed care delivery system. ILOS are intended to be provided in place of a more expensive standard Medicaid benefit. If states opt in to provide ILOS (and receive federal funds in respect of them), federal law requires that ILOS be optional for managed care plans to provide and beneficiaries to accept. DHCS has proposed a menu of ILOS benefits that managed care plans could choose to provide beginning in January 2021, as shown in Figure 4. Notably, the ILOS benefits proposed to be offered include housing assistance benefits. Some of them have restrictions on how much they can be used or who is eligible, including benefits that are only available for use once in a beneficiary’s lifetime unless the managed care plan demonstrates why provision of an additional benefit would be cost‑effective. While some other states have opted in to provide ILOS, their offerings of services tend to be more limited in scope than what is being proposed under CalAIM.

Figure 4

Proposed “In Lieu of Services” Benefits

|

Benefit |

Description |

|

Services to Address Homelessness and Housing |

|

|

Housing depositsa |

Funding for one‑time services necessary to establish a household, including security deposits to obtain a lease, first month’s coverage of utilities, or first and last month’s rent required prior to occupancy. |

|

Housing transition navigation servicesa |

Assistance with obtaining housing. This may include assistance with searching for housing or completing housing applications, as well as developing an individual housing support plan. |

|

Housing tenancy and sustaining servicesa |

Assistance with maintaining stable tenancy once housing is secured. This may include interventions for behaviors that may jeopardize housing, such as late rental payment and services to develop financial literacy. |

|

Services to Allow Long‑Term Placement in Home‑Like Settings |

|

|

Day habilitation programs |

Programs provided to assist beneficiaries with developing skills necessary to reside in home‑like settings, often provided by peer mentor‑type caregivers. These programs can include training on use of public transportation or preparing meals. |

|

Environmental accessibility adaptations |

Physical adaptations to a home to ensure the health and safety of the beneficiary. These may include ramps and grab bars. |

|

Nursing facility transition/diversion to assisted living facilitiesb |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to community settings, or prevent beneficiaries from being admitted to nursing facilities. |

|

Nursing facility transition to a home |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries transitioning from nursing facility care to home settings in which they are responsible for living expenses. |

|

Personal care and homemaker servicesc |

Services provided to assist beneficiaries with daily living activities, such as bathing, dressing, housecleaning, and grocery shopping. |

|

Recuperative Services |

|

|

Meals/medically tailored meals |

Meals delivered to the home following discharge from a hospital and meals that are tailored to meet beneficiaries’ unique dietary needs. |

|

Recuperative care (medical respite) |

Short‑term residential care for beneficiaries who no longer require hospitalization, but still need to recover from injury or illness. |

|

Respite |

Short‑term relief provided to caregivers of beneficiaries who require intermittent temporary supervision. |

|

Short‑term post‑hospitalization housinga |

Setting in which beneficiaries can continue receiving care for medical, psychiatric, or substance use disorder needs immediately after exiting a hospital. |

|

Sobering centers |

Alternative destinations for beneficiaries who are found to be intoxicated and would otherwise be transported to an emergency department or jail. |

|

aRestricted to use once‑in‑a‑lifetime, unless managed care plan can demonstrate cost‑effectiveness of providing a second time. bIncludes residential facilities for the elderly and adult residential facilities. cDoes not include services already provided in the In‑Home Supportive Services program. |

|

Require Managed Care Plans to Develop Population Health Management Program. A population health management program is an approach to planning used by a managed care plan to determine how to address the varying conditions across its group of enrollees along a continuum of care. Managed care plans are not currently required to have a population health management program, but would be newly required to under CalAIM. Specifically, managed care plans would be required to outline strategies for (1) focusing on preventive and wellness services; (2) grouping, or “stratifying,” enrollees based on their risk and need; (3) addressing the needs of enrollees in these various groups with differing services and levels of case management; and (4) identifying and mitigating health disparities (for example, across racial or ethnic groups). The population health management programs would be implemented beginning in January 2022.

Convene Foster Care Workgroup. Current and former foster youth have unique and complex needs among Medi‑Cal’s various enrollee populations. In an effort to create a forum for focused deliberations over potential improvements to their care, DHCS intends to convene a workgroup beginning in 2020 with interested stakeholders. What specific policy changes will be considered by the workgroup is unclear. However, the workgroup’s discussions could include whether or not to encourage greater enrollment of foster youth in managed care than is the case currently, ways to improve behavioral health service delivery to foster youth, and how to better serve and appropriately fund foster youth who move from one county to another. DHCS intends for the workgroup to include participation from a wide variety of stakeholders, including Medi‑Cal managed care plans; county child welfare and behavioral health departments; and other representatives of social services, education, and juvenile justice.

Transforming and Streamlining Managed Care

This section provides an overview of six components of CalAIM that are primarily intended to transform and streamline Medi‑Cal managed care.

Transition Certain Benefits Into Managed Care Statewide. DHCS proposes moving certain benefits into managed care that currently are in managed care only in certain parts of the state. The first of these benefits is the long‑term care SNF benefit. The second is major organ transplants. Under the proposal, both of these benefits would be moved into managed care beginning in January 2021.

Transition Certain Other Benefits Out of Managed Care Statewide. In addition to moving certain benefits into managed care on a statewide basis, DHCS intends to carve certain benefits out of managed care. The benefits that DHCS intends to carve out include (1) pharmacy services (which we discuss separately in The 2020‑21 Budget: Analysis of the Medi‑Cal Budget), (2) specialty mental health services in the two counties (Sacramento and Solano Counties) where they are carved in for enrollees in the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, (3) the Multipurpose Senior Services Program, and (4) optical lens fabrication. Effective January 2021, these benefits would be reimbursed through Medi‑Cal FFS.

Modify Approach to Coordinating Care of Beneficiaries Eligible for Both Medi‑Cal and Medicare. Under the proposal, CMC plans would be discontinued in January 2023 (the date at which federal approval for the integrated plans ends). Instead, the state would require all Medi‑Cal managed care plan contractors to establish specialized plans, known as Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D‑SNPs), which are designed to provide managed Medicare benefits to individuals who also are eligible for Medi‑Cal. Under this framework, Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who also are eligible for Medicare could, but would not necessarily be required, to receive their Medicare benefits through a D‑SNP that is operated by the same contracted managed care plan that provides their Medi‑Cal benefit. (We will describe this particular aspect of the CalAIM proposal in more detail and provide our assessment in a separate forthcoming publication related to CalAIM’s implications for aging issues.)

Set Regional Capitated Rates. Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ capitated rates are set for a number of distinct populations of Medi‑Cal enrollees. In addition, with the exception of most of California’s largely rural counties, managed care plans’ capitated rates are set on a county‑by‑county basis. Setting different capitated rates for distinct Medi‑Cal populations and across counties greatly adds to the complexity of the capitated rate‑setting process. According to DHCS, the capitated rate‑setting process currently involves calculating more than 4,000 distinct components. In an effort to simplify the capitated rate‑setting process and also improve fiscal management of Medi‑Cal managed care, DHCS proposes to move to a regional capitated rate‑setting process whereby capitated rates would be set over broader geographic areas than they are currently. DHCS intends to implement regional capitated rate‑setting in two phases, with the first phase implementing beginning in January 2021 and the second phase implementing no sooner than January 2023. We understand that phase one would potentially involve implementation of regional capitated rates in areas where it is most feasible—for example, across adjacent county lines where the same managed care plans operate in both counties.

Require National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Accreditation of Managed Care Plans. In an effort to increase standardization across Medi‑Cal managed care plans and streamline oversight of them, DHCS proposes to require plans to obtain NCQA accreditation by 2025. Through the accreditation process, plans are evaluated and certified as meeting minimum standards in such areas as provider network management, utilization management, and member communication and experience. According to DHCS’ analysis, NCQA accreditation standards are equal to, or more stringent than, many if not most federal and state standards for Medi‑Cal managed care. DHCS intends to use plan adherence to NCQA accreditation standards to “deem” that plans meet federal and state Medi‑Cal standards wherever possible. In so doing, DHCS would be able to reduce some of the administrative burdens associated with oversight of Medi‑Cal managed care plans, from both a state and a plan perspective.

Consider Creation of a Full‑Integration Pilot. Currently, beneficiaries enrolled in Medi‑Cal managed care receive most physical health care from their managed care plan; specialty mental health and substance use services from the county behavioral health delivery system; and many other services, such as dental care, through FFS. Given the challenges Medi‑Cal beneficiaries with complex needs may have in navigating potentially several different delivery systems for care, DHCS is proposing pilot programs that would integrate physical, behavioral, and dental care under a single contracted entity, and is engaging in stakeholder conversations to inform development of these pilots and address any issues with implementing them. DHCS proposes to implement these pilot integration plans in participating counties beginning in January 2024.

Extending Components of the Current 1115 Waiver

Overall, the CalAIM proposal takes a different approach to federal Medicaid waivers than has been used in the past. Under the CalAIM proposal, authority to operate the managed care delivery system would be moved from the state’s 1115 waiver into the state’s 1915(b) waiver, the same authority used for the state’s specialty mental health carve out. Moreover, relatively few other items currently in the state’s current 1115 waiver would remain in a new 1115 waiver that the state would propose to the federal government for approval. In this section, we describe how certain components of the current waiver would be handled under the CalAIM proposal.

Continue Public Hospital Funding Under Other Programs. In 2018, the federal government changed how it defines cost‑neutrality for purposes of 1115 waivers. This change significantly limited the state’s ability to use savings in the managed care delivery system as justification to receive additional federal funding for state initiatives under the waiver. As a result, DHCS does not propose extending the PRIME program as part of waiver. Instead, DHCS proposes to increase quality incentive payments for public hospitals through a separate program known as the Quality Improvement Program that currently is not part of the state’s 1115 waiver. DHCS proposes to increase the size of this program to preserve much or all of the funding that public hospitals receive through PRIME. Funding for the Global Payment Program largely is not derived from estimated savings from the state’s transition to managed care. As a result, the state likely could continue receiving most Global Payment Program funding through an 1115 waiver. DHCS proposes to continue the Global Payment Program in the new 1115 waiver proposal.

Maintain Expansion of Substance Use Disorder Services Begun Under DMC‑ODS. DHCS is proposing to allow counties to continue providing the more comprehensive substance use disorder services under DMC‑ODS by incorporating DMC‑ODS into the new 1915(b) waiver and renaming the program to substance use disorder managed care. However, DHCS would still pursue expenditure authority for substance use disorder treatment provided in IMDs through an 1115 waiver. Counties still would be able to opt in to the substance use disorder managed care plan model. DHCS intends to implement these changes beginning in January 2021.

Extend and Expand Statewide Components of Dental Transformation Initiative. With the expiration of the current waiver at the end of 2020, the Dental Transformation Initiative would end absent its reauthorization through a new waiver or state plan authority. To maintain and build on the increases in dental care utilization that have occurred since the Dental Transformation Initiative began, DHCS proposes to continue the statewide components of the Dental Transformation Initiative on an ongoing basis. These statewide Dental Transformation Initiative components, which would continue in similar forms under the CalAIM proposal, include funding for (1) dental risk assessments for young children, (2) the provision of preventive dental services, and (3) meeting benchmarks on continuity of care. While funding for the Dental Transformation Initiative was limited to children’s services, under CalAIM, DHCS proposes to expand the preventive and continuity of care components to cover adult dental services as well. A recent change in federal rules will no longer allow the state to claim state expenditures on other state health programs as the nonfederal share of cost for Medi‑Cal expenditures. As a result, going forward, the Governor proposes to use General Fund to fund the nonfederal share of cost for the extension of the Dental Transformation Initiative components.

Rethinking Behavioral Health Service Delivery and Financing

The CalAIM proposal includes a number of proposed reforms to improve service delivery for Medi‑Cal county behavioral health. (Some of these changes will be included in the 1915(b) waiver discussed earlier in this report.)

Streamline Behavioral Health Financing. The CalAIM proposal intends to streamline how county behavioral health departments receive reimbursement for providing Medi‑Cal eligible services. Currently, counties pay for behavioral health services when they are administered. They then submit certified public expenditures (CPEs)—expenditures that are recognized to be eligible for federal reimbursement because they provide a Medi‑Cal covered service—to DHCS so that eligible federal matching funds can be received. The state then reimburses counties on an interim basis until the completion of a cost reconciliation process (that usually takes several years). The current financing system is cost‑based, which does not account for quality or outcomes in reimbursement amounts.

DHCS is proposing to transition behavioral health financing from a CPE structure to a system that utilizes a different funding mechanism known as intergovernmental transfers (IGTs) to provide payment to counties. Under an IGT framework, the state would identify an overall funding amount for a period of time (such as a month) and counties would transfer funds to the state to cover the nonfederal share of costs. (This is more akin to setting a rate for services provided, as opposed to strict cost reimbursement.) The state then would use these funds to claim federal funding and return both the federal funds and the local funds to counties for use in providing behavioral health services, eliminating the need for cost reconciliation. Since funding amounts would not require detailed and lengthy cost reconciliations, an IGT framework could reduce administrative burden and multiyear fiscal uncertainty. Some additional details need to be clarified before this change would be implemented, including how the advanced funding amounts would be set under an IGT framework.

Explore Federal Funding Opportunities for Residential Care. Historically, the state has not received federal reimbursement for mental health services provided in IMDs. In 2018, the federal government provided an 1115 waiver opportunity to states to potentially receive federal reimbursement for otherwise Medi‑Cal covered services that are provided during short‑term stays in psychiatric hospitals or residential treatment settings that qualify as IMDs. If the state chooses to pursue this opportunity, it will have to adhere to a set of requirements from the federal government, including requirements related to permissible length of stay, level of staffing, and state maintenance of effort for investing in community mental health services. The administration has yet to reach a decision on whether to pursue this waiver opportunity.

Change Medical Necessity Criteria for Beneficiaries to Access Services. Existing beneficiary eligibility for specialty mental health services is determined by diagnosis and level of impairment. Individuals often present with symptoms of mental illness before providing an accurate diagnosis of their condition is possible. Consequently, the need to diagnose prior to receiving services is problematic for county mental health plans. For example, some plans may be reluctant to offer services to beneficiaries who have significant mental health impairments but do not have a diagnosis for mental illness. Alternatively, plans may have to forego federal funding for specialty mental health services that ultimately could be eligible for federal reimbursement.

DHCS is proposing to reform medical necessity criteria for behavioral health services to focus more on level of impairment—the degree to which a person’s behavioral health issue affects their self‑care or daily living skills—rather than specific diagnoses. DHCS is proposing to develop statewide, standardized assessment tools (one for beneficiaries over age 21 and one for beneficiaries under age 21) to determine eligibility for specialty mental health services based on level of impairment. DHCS intends to implement revisions to medical necessity criteria in January 2021.

Implement “No Wrong Door” Approach for Children Obtaining Mental Health Services. Current law and policy is somewhat ambiguous regarding where beneficiaries under the age of 21 are to receive certain mental health services—whether this should be through a Medi‑Cal managed care plan or in the county behavioral health system. DHCS is proposing a No Wrong Door approach to care for this population, in which both managed care plans and county behavioral health plans would be reimbursed for behavioral services provided regardless of whether a beneficiary under age 21 moves to a different delivery system. DHCS intends to implement this approach in January 2021.

Integrate County Administration of Specialty Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services. Currently, specialty mental health services and substance use disorder treatment services are administered separately at the county level. DHCS is proposing to eventually integrate specialty mental health services and substance use disorder services under single behavioral health managed care plans in the majority of the state’s counties. DHCS intends to implement this proposal under a new 1915(b) waiver in 2026.

Governor’s 2020‑21 Budget Proposal to fund CalAIM

Proposal Funds Key Aspects of Proposal to Be Implemented in 2020‑21. The CalAIM proposal includes significant funding in 2020‑21 to implement its reforms. The Governor’s budget proposes $695 million total funds ($347.5 million General Fund) for CalAIM for a half year of implementation in 2020‑21. Additional funding would be provided in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 to reflect a full year of implementation. On an ongoing basis, the Governor proposes to provide a lower amount of $395 million General Fund ($790 million total funds) annually to reflect the phase out of temporary incentive payments. We briefly describe these funding components later in this section and display amounts for these items over time in Figure 5. Notably, these totals do not include any state operations funding for DHCS to implement the CalAIM proposal. The Governor’s budget includes a placeholder amount of $40 million total funds ($20 million General Fund) for this purpose. The administration intends to provide more detail on estimated state operations costs later in the year before the budget is enacted.

Figure 5

Components of Proposed CalAIM Fundinga, by Year

(In Millions)

|

Components |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 Through 2022‑23 |

2023‑24 and Ongoing |

|||

|

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

General Fund |

Total Funds |

|

|

ECM |

$112.5 |

$225.0 |

$225.0 |

$450.0 |

$225.0 |

$450.0 |

|

ILOS |

28.8 |

57.5 |

57.5 |

115.0 |

57.5 |

115.0 |

|

Incentives for ECM and ILOS |

150.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

600.0 |

— |

— |

|

Dental services |

56.3 |

112.5 |

112.5 |

225.0 |

112.5 |

225.0 |

|

Total |

$347.5 |

$695.0 |

$695.0 |

$1,390.0 |

$395.0 |

$790.0 |

|

aFunding amounts do not include state operations funding for the Department of Health Care Services to implement the CalAIM proposal. The Governor’s budget includes placeholder funding (not shown) of $20 million General Fund ($40 million total funds) for this purpose. CalAIM = California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal; ECM = enhanced care management; and ILOS = in lieu of services. |

||||||

Funding for ECM Benefit. The Governor’s proposal includes $112.5 million from the General Fund ($225 million total funds) in 2020‑21 and $225 million from the General Fund ($450 million total funds) in 2021‑22 and ongoing to fund the new ECM benefit. DHCS indicates that it developed this estimate of funding needs based on experience with the Health Homes Program.

Funding for “Existing” ILOS. The Governor’s proposal includes $28.8 million from the General Fund ($57.5 million total funds) in 2020‑21 and $57.5 million from the General Fund ($115 million total funds) in 2021‑22 and ongoing to pay for services that are currently being provided through current programs like Whole Person Care and Health Homes that now would be provided under ILOS. The Governor’s budget does not explicitly identify new funding for additional ILOS benefits that would be implemented through CalAIM, as these benefits would be provided in place of more costly benefits currently being provided and that are already included in capitated rates paid to managed care plans.

Incentives for ILOS and ECM. However, the Governor’s proposal does include significant funding for “incentive payments” to managed care plans to encourage the adoption of ILOS benefits and to build up capacity to provide ECM. The budget includes $150 million from the General Fund ($300 million total funds) in 2020‑21, and $300 million from the General Fund ($600 billion total funds) in each of 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. No additional incentive funding would be provided thereafter. While the structure of these incentive payments has not been determined, the administration indicates the payments would be provided to managed care plans for meeting benchmarks related to bringing on ECM and ILOS benefits.

Funding for Dental Services. As noted previously, a new funding source other than the state’s 1115 waiver is required to continue components of the Dental Transformation Initiative. The Governor proposes to provide $56.3 million from the General Fund ($112.5 total funds) in 2020‑21 and $112.5 million from the General Fund ($225 million total funds) in 2021‑22 and ongoing to support components of the Dental Transformation Initiative that cannot be continued in the 1115 waiver.

LAO Assessment

In this section, we provide our initial assessment of the CalAIM proposal. As noted earlier, the administration is in the process of developing the specific elements of many components of the proposal. Consequently, our assessment is based on our understanding of the proposal based on conversations with the administration, observation of ongoing working groups, and currently available public documents on CalAIM. At the time of this writing, the administration has not released any proposed statutory language for CalAIM.

Overall, we find several ways that the conceptual approach of the CalAIM proposal appears promising. However, the proposal also presents risks and raises many questions as to how the changes in the proposal would be implemented and the effects they would have in practice.

Policy Proposal Could Bring Benefits…

Proposal Expands on Vision of Medi‑Cal Managed Care. Managed care is intended to promote efficient and effective health care by (1) making managed care plans and their contracted providers responsible for arranging for care (including which types of services are available and which types of services to emphasize) and (2) creating financial incentives for managed care plans to do so in the most cost‑effective way possible. This financial incentive is created by paying managed care plans a fixed capitated payment for a beneficiary that does not vary, at least in the short run, with the amount of health care services a beneficiary utilizes. In theory, this should lead to managed care plans identifying new and less costly ways to address beneficiaries’ needs that provide at least similar outcomes. However, while managed care plans can provide services similar to ILOS today, plans do not have the ability to claim their spending on these benefits for purposes of setting capitated rates and do not get to keep savings generated from providing alternative benefits. The CalAIM proposal, primarily by allowing the option for plans to provide in lieu services and have these costs reflected in capitated rates, encourages managed care plans to provide alternative services.

By moving the SNF benefit into managed care statewide, the CalAIM proposal also could strengthen plan incentives to provide effective, less‑costly care for those potentially needing SNF services. Because plans would not immediately receive higher rates when beneficiaries move into SNFs, plans might opt to utilize less‑costly settings when feasible. There is general agreement that some SNF residents could be safely cared for in more community‑based settings and would prefer to do so if appropriate alternative services were available. In many cases, these alternative services would be less costly than the individual remaining in a SNF.

Provides New Opportunity to Receive Federal Funding for Services. Some of the services that managed care plans would provide under CalAIM, such as ECM or ILOS, are provided to some degree today by counties and other nongovernment entities. For example, many counties use existing local resources to operate sobering centers and recuperative care centers in light of their potential to reduce length of stay and repeat admissions to hospitals for individuals that need temporary housing for recovery. By enabling managed care plans to provide these services as an ILOS, the CalAIM proposal effectively would allow the state to obtain federal Medicaid funding to offset the cost of these services and possibly expand services overall.

In Some Ways, Proposal Would Move Toward Greater Standardization and Simplicity. Several aspects of the CalAIM proposal would address some of the complexity in the current Medi‑Cal program and move toward greater standardization (both across program components and across the state) and simplicity. Key examples of the increased standardization and simplification include: (1) standardizing which benefits are covered through managed care statewide by carving in the long‑term care SNF benefit and major organ transplants; (2) requiring plans statewide to offer D‑SNPs; and (3) expanding the potential to have a more comprehensive approach to addressing the needs of high‑cost populations, such as those provided through the Whole Person Care and Health Homes programs, through ECM and ILOS benefits statewide.

The CalAIM proposal also would simplify state administration in some ways. The state currently sets separate managed care rates for several categories of service and population types for every managed care plan in every county. This results in a very large number of rate determinations that need to be made on an annual basis, resulting in significant workload for DHCS and federal oversight agencies. Combining counties into a smaller number of regions for rate setting—as proposed—would reduce this workload and streamline program administration.

NCQA Accreditation Proposal Has Potential to Streamline Oversight of Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans. Over two‑thirds of Medi‑Cal managed care plans already have or are in the process of obtaining full NCQA accreditation. As a result, these plans currently face duplicative oversight since they must prove to two separate oversight entities—NCQA and DHCS—that they meet what are often overlapping standards. By using NCQA accreditation findings to determine whether plans meet or surpass federal and state Medi‑Cal standards, the state could streamline oversight of Medi‑Cal managed care plans. California would join 25 other state Medicaid programs—plus the District of Columbia’s—that currently require NCQA accreditation. Of these 26 Medicaid programs, 14 use NCQA accreditation to deem at least partial adherence to federal and state Medicaid standards. Figure 6 provides a summary of the extent to which adherence to federal and state standards for Medi‑Cal could be deemed through compliance with NCQA accreditation standards.

Figure 6

Federal and State Standards Are Likely at Least Partially Deemable Through NCQA Accreditation

|

Category |

NCQA Standard Likely Meets or Exceeds State and Federal Standards for: |

Examples of Standards Met |

Examples of Standards Not Met |

|

Member Experience and Communications |

13 out of 27 standards |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Population Health Management |

7 out of 9 standards |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Access to Care |

17 out of 32 standards |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Quality Measurement and Improvement and Program Integrity |

7 out of 12 standards |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Note: LAO tabulation based on DHCS’ comparison between NCQA accreditation and federal and state standards for Medi‑Cal managed care. NCQA = National Committee on Quality Assurance; OON = out‑of‑network; LTSS = long‑term services and supports; LAO = Legislative Analyst’s Office; and DHCS = Department of Health Care Services. |

|||

Continuation of Programs From State’s Current 1115 Waiver Has Merit. Overall, the Governor’s approach to continuing certain programs currently part of the state’s 1115 waiver—including public hospital financing programs, components of the Dental Transformation Initiative, and DMC‑ODS—makes sense and has merit given the benefits of these programs.

Behavioral Health Reforms Could Improve Service Delivery. The proposed behavioral health reforms under the CalAIM proposal could improve behavioral health service delivery in a number of ways. Broadening the scope of beneficiaries who are eligible for these services through revised medical necessity criteria (that focus more on level of impairment) could increase utilization and provide treatment earlier. The proposed financing reforms (moving from CPE reimbursement to an IGT reimbursement framework) also could give county mental health plans more flexibility to provide services, and reduce their administrative burden due to the state’s lengthy cost reconciliation process. CalAIM also presents an opportunity for the state to draw down additional funding through Medi‑Cal through reimbursement for services provided in IMDs and for services provided to beneficiaries without a covered diagnosis.

…But Many Questions Remain

While the CalAIM proposal likely could bring significant benefits, the reform proposal also presents a number of risks and raises many outstanding questions. Given that the CalAIM proposal is a work in progress and is on various tracks—including stakeholder workgroups and potentially the policy bill process—having a lot of outstanding questions is to be expected. Many of these should be answered over the next few months as more details are ironed out. We organize this section by major issue area to highlight the critical questions to be answered during legislative deliberations on the proposal.

Is Managed Care Ready for This Significant Expansion?

The CalAIM proposal would significantly expand the role of Medi‑Cal managed care plans by giving them tools and funding not only to address their members’ medical conditions, but also their broader needs related to housing and social services. While this presents Medi‑Cal managed care plans with an opportunity to better address their members’ overall needs, the expanded role of Medi‑Cal managed care raises major issues for consideration, which we discuss in this section.

Existing Concerns About Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Meeting Basic Responsibilities. Multiple evaluations from recent years raise concerns about Medi‑Cal managed care plans meeting their basic responsibilities related to ensuring their members receive appropriate health care services. For example, a recent report from the California State Auditor showed that utilization of children’s preventive services in Medi‑Cal lags that of most other states’ Medicaid programs. (A significant majority of children on Medi‑Cal are enrolled in managed care, showing that plan efforts to encourage preventive children’s services may be inadequate.) Similarly, researchers recently assessed Medi‑Cal managed care plan performance, as measured by the common Healthcare Effectiveness Data Information Set (HEDIS) quality scores—where plan quality is assessed based on measures such as vaccination rates and receipt of prenatal care. The assessment showed that plan performance was below the state’s longstanding, low minimum performance standard for nearly one‑quarter of the HEDIS measures and that plan quality scores have declined or remained stagnant about as often as they have improved. Given these and other challenges within Medi‑Cal managed care, whether Medi‑Cal managed care plans currently are meeting their responsibilities related to their core competencies—delivering high‑quality, appropriate, timely, and cost‑effective health care to their members—remains an outstanding question.

New Benefits Would Require Managed Care Plans to Develop New Expertise. The CalAIM proposal would encourage plans to arrange and pay for nonmedical services—specifically ILOS—with which they have limited experience providing, such as temporary housing assistance. Accordingly, managed care plans would need to establish new relationships, contracts, and payment mechanisms with community‑based organizations and other local entities that provide ILOS such as housing. How quickly and successfully Medi‑Cal managed care plans will be able to establish these new relationships with local service providers is unknown. Moreover, how Medi‑Cal managed care plans will balance (1) adding capacity to provide new services under CalAIM, including ILOS, and (2) improving their performance on their existing, core responsibilities, as discussed in the previous paragraph, is uncertain.

What Trade‑Offs Does Using NCQA Accreditation for Managed Care Oversight Present?

As previously discussed, DHCS has proposed to require NCQA accreditation of all Medi‑Cal managed care plans, and to use their accreditation to deem that plans meet most federal and state standards for Medi‑Cal managed care. We believe this proposal merits consideration, though we have a number of related outstanding questions. First, while an initial crosswalk of NCQA and federal and state Medi‑Cal managed care standards has been completed, more detailed analysis appears necessary to validate which federal and state standards would and would not be possible to deem as being met due to NCQA accreditation. Second, while we understand that obtaining initial NCQA accreditation costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, we have not seen a fiscal estimate of the cost to the state of requiring Medi‑Cal managed care plans to obtain and maintain NCQA accreditation (a cost to plans that is potentially reimbursable through capitated rate setting). Third, DHCS has not released a fiscal estimate of what state resources currently dedicated to Medi‑Cal managed care plan oversight could be freed up by adopting this proposal. Obtaining the fiscal information described above would allow the Legislature to better understand the net fiscal impact of the NCQA proposal. Moreover, the Legislature likely will want to consider the policy implications of delegating this critical state function—oversight of Medi‑Cal managed care—to a contracted entity. We think the answers to the above questions would enable the Legislature to more fully weigh the benefits and costs associated with this proposal.

How Would New Benefits Expand the Supply of Already Limited Services?

Services Similar to ILOS and Case Management Services Already May Be Limited. The success of the CalAIM proposal would depend, in part, on Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ ability to marshal community resources to serve the broader, nonmedical needs of their members. As such, limits in the availability of community resources could affect the effectiveness of the reform effort, as well as the speed of its success. For example, constraints in the local housing supply in certain communities could make assisting members in obtaining appropriate housing a challenge for managed care plans. In fact, limited housing availability has been among the most common challenges cited by implementers of the Whole Person Care pilots. As another example, not all communities have organizations that provide general case management services. In these communities, Medi‑Cal managed care plans would need to devote time and resources to establish local case management services, meaning that the full benefits of ECM services may be slow to materialize in these communities.

Whether New Benefits Would Supplement or Supplant Existing Services Is Unclear. Existing community services and new benefits under the CalAIM proposal overlap. For example, local ILOS and ECM services currently include: (1) local homelessness support programs funded through the Homelessness Coordinating and Finance Council under the Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency; (2) targeted case management programs available through county specialty mental health plans and the Department of Developmental Services delivery system; and (3) personal care services available through IHSS. While DHCS has indicated that certain existing programs would continue to operate in conjunction with the proposed new ECM and ILOS benefits, how CalAIM ultimately would affect, and operate in tandem with, other existing programs is unclear. At one end—given the level of demand—the new CalAIM benefits could supplement existing programs and act largely as an additional point of entry for obtaining the benefits available through ECM and ILOS. At the other end, CalAIM services could end up supplanting some of these services—ultimately resulting in Medi‑Cal managed care being a principal route by which low‑income individuals and families can access these services.

What Fiscal Risks Could New Benefits Create?

While New Benefits Are Intended to Be in Lieu of More Expensive Services… As the name suggests, ILOS are intended to be in place of existing Medi‑Cal benefits. Thus, for example, in‑home personal care services are intended to deter placement in nursing facilities, recuperative care is intended to reduce hospitals stays, and temporary housing assistance is intended to prevent emergency room visits for conditions that might develop during periods of homelessness. To receive federal funding, federal regulations require ILOS to be “cost‑effective” substitutes for covered health care services. Federal regulations do not prescribe, however, how cost‑effectiveness is to be determined, and instead appear to give states broad flexibility in making this determination.

Importantly, the option to provide ILOS was fairly recently granted to state Medicaid programs. To our understanding, no state has proposed as expansive a set of ILOS for federal consideration as California would under CalAIM. Without precedent for a proposal of this scale, anticipating whether the federal government would ultimately approve this component of the state’s CalAIM proposal is unclear.

…In Practice, Calculating Cost‑Effectiveness in Medi‑Cal Might Be Difficult. While, in theory, ILOS are intended to be cost‑effective relative to the costs of covering existing Medi‑Cal services, in practice this will be very difficult to track. Medi‑Cal spending and utilization data may not be able to show definitively that spending on the new ILOS benefits is in place of and less expensive than providing existing covered benefits. Moreover, tracking Medi‑Cal expenditure data would not capture all the ways in which an ILOS benefit potentially could result in savings or costs to government (potentially outside of health care services) or others.

Initial Evidence on Preventive Services Raises Questions Regarding Potential Medi‑Cal Savings. The following bullets summarize evidence showing that providing additional preventive and social services does not necessarily result in significant offsetting reductions in spending on services that are more expensive.

- The ACA. The ACA was intended to reduce hospital stays and emergency department visits by increasing access to preventive health care services, where patients’ conditions could be treated before they worsen and require inpatient or emergency care. Subsequent evidence does not show this to have been the case; rather, utilization of preventive, inpatient, and emergency services alike has increased under the ACA.

- Camden “Hot‑Spotters” Model. Researchers recently published a high‑quality study of a program in Camden, Massachusetts that delivered intensive clinical, social supportive, and case management services to “super‑utilizers” of health care services—a population comprising less than 0.5 percent of the city’s population but that accounted for 11 percent of the city’s hospital’s expenditures. The study found that super‑utilizers who received the intensive services had comparable rates of subsequent hospital admissions as a control group who did not receive the intensive services.

- Whole Person Care Evaluation. As discussed in the background, CalAIM is in many ways designed to build upon programs in the current 1115 waiver. In particular, the proposed new ECM and ILOS benefits reflect benefits that were piloted as a part of Whole Person Care. In late 2019, a preliminary evaluation of Whole Person Care was released looking at how the pilot has affected service delivery, interagency collaboration, and the cost‑effectiveness of health care. While the evaluation showed certain improvements in service delivery and interagency collaboration, the evaluation did not consistently show improved cost‑effectiveness in the form of lower hospital and emergency department utilization among Whole Person Care beneficiaries relative to a comparison group.

DHCS has not yet released detailed state policy guidance on how cost‑effectiveness will be overseen and enforced by the state. Depending on how the state’s policy on cost‑effectiveness is formulated, there is a distinct possibility that adding ILOS benefits ultimately could come with significant ongoing net costs to the state. That said, there could be policy reasons—as we discuss in the next paragraph—that could make pursuing the benefits worthwhile.

Fiscal Risks Should Be Weighed Against Potential Policy Benefits of ILOS. Even if ILOS have the potential to result in higher net costs, they still merit policy consideration as potentially effective approaches to meeting Medi‑Cal beneficiaries’ broader needs. For example, there is evidence from the Camden study that beneficiary access to non‑health care programs, such as food assistance, can improve by providing intensive case management services. Moreover, while the increased hospitalizations observed under the Whole Person Care interim evaluation do not show that the pilot has been consistently effective in reducing health care costs, the additional hospitalizations might address beneficiaries’ sometimes longstanding medical needs and leave them with improved health going forward.

Managed Care Plans’ Choices About Which Services Would Be Offered Would Affect Cost‑Effectiveness. Federal law requires the state to allow managed care plans to choose whether—and which—ILOS services to offer. If plans do not widely opt to provide ILOS, the availability of these new services could be more limited in scope than the state ultimately desires. Moreover, if plans deem only a limited set of services as cost‑effective, the proposal may not be as effective as intended.

Establishment of New Benefits May Introduce New Fiscal Risks for Managed Care Plans… Whereas ECM is intended to be a statewide Medi‑Cal managed care benefit, managed care plans would have the power to decide which, if any, of the ILOS benefits they will provide. The extent to which managed care plans could, once deciding to provide an ILOS, determine which members are eligible or not for the ILOS is less clear. DHCS has yet to release detailed policy guidance on this issue of plan flexibility related to ILOS eligibility decisions. Relatively lower or higher degrees of plan flexibility could come with distinct trade‑offs and fiscal implications, as described in the next paragraphs.

With low flexibility, once plans opt to provide an individual ILOS benefit, Medi‑Cal managed care plans could be responsible for providing and paying for ILOS generally as an “entitlement” benefit. In other words, plans could have to provide and pay for the benefit to the extent that their members meet state‑established eligibility requirements for the benefit. This would introduce fiscal risk for managed care plans since—absent opting to no longer provide the ILOS—they might have only limited authority to manage utilization of the new benefit. Moreover, in the short term, certain plans would be reimbursed for the projected but not actual cost of providing the benefit. Should the short‑term cost of providing the ILOS benefit exceed provided funding, these managed care plans would have to use other plan resources—such as savings from lower costs elsewhere, reserves, or foregone profits—to cover the unreimbursed costs.

On the other hand, with high flexibility, managed care plans ultimately might have significant discretion to determine whether an ILOS would be a cost‑effective alternative to a standard Medi‑Cal benefit for an individual member. Only in cases where this determination is positive, and where the member chooses to accept the ILOS, would managed care plans be obligated to provide the ILOS. Granting managed care plans this flexibility could help mitigate the fiscal risk—for both plans and the state—associated with ILOS. However, if such discretion ultimately is granted to managed care plans, there could be inconsistencies in the provision of ILOS over time, across plans, and even across members of the same plan.

…And for the State. We understand that, in the long run, the proposed new ECM and ILOS benefits are intended to be reimbursed by the state in a manner similar to how most other benefits within Medi‑Cal managed care are reimbursed. That is, they would be reimbursed through the standard capitated rate‑setting process, whereby the state establishes capitated‑rate levels largely based on Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ average reported costs per beneficiary. (Because of the complexity of the rate‑setting process, it typically takes two to three years for year‑over‑year changes in plan costs to be reflected in their capitated rates.) Since the state pays Medi‑Cal managed care plans largely on the basis of their costs, any growth in managed care plans’ ILOS costs would ultimately be borne by the state. Since ECM and any ILOS benefits provided by Medi‑Cal managed care plans could be similar to entitlement benefits—where the state could not necessarily manage utilization through the use of waiting lists, for example—the state might have less control over its fiscal commitment to these services than if they were provided through programs other than Medi‑Cal on a nonentitlement basis.

Tracking ILOS Spending Could Be Challenging. In early February 2020, DHCS announced that managed care plans’ costs for ILOS would likely not be reflected as a separate benefit category within managed care capitated rates. This could mean that the standard managed care plan cost reports would not necessarily separately identify their costs on ILOS. These standard cost reports represent the only reporting mechanism available to the Legislature that we are aware of that provides detailed information on how state funding is used within Medi‑Cal managed care. At this time, the rationale for not separately identifying ILOS costs is unclear. Accordingly, we have outstanding questions about how this decision could affect the Legislature’s and potentially even DHCS’ ability to accurately identify and oversee how much funding the state is dedicating to ILOS on an ongoing basis. (Moreover, this could complicate the Legislature’s oversight of the outcomes achieved from spending on ILOS.) If ILOS costs ultimately are not separately identified in the standard cost reports, additional reporting requirements might be necessary to ensure transparency.