LAO Contact

March 6, 2020

Excess ERAF: A Review of the Calculations Affecting School Funding

- Introduction

- Background

- Findings and Concerns

- Administration’s Recent Actions

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Hundreds of Millions of Dollars in Property Tax Revenue at Issue. This report focuses on a state law enacted in the 1990s that shifts some of the property tax revenue in certain counties from schools and community colleges to other local agencies. For historical reasons, the shifted revenue is known as “excess ERAF.” (The acronym refers to the local accounts—known as Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds—that facilitate the shift.) We recently found that some counties are calculating excess ERAF in ways that seem contrary to state law and shift too much property tax revenue from schools to other agencies. We have three specific concerns related to the calculation of excess ERAF that together affect more than $350 million in annual property tax revenue. Earlier this year, the Newsom administration began to address one of these concerns. In this report, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to enforce state law on our other two concerns. We also recommend improving oversight to prevent similar issues from arising in the future.

Background

Property Tax Revenue Shared Among Local Agencies. The State Constitution requires the proceeds of the property tax to be allocated among the local agencies in the county where the revenue is collected. Recipients of property tax revenue include cities, counties, special districts, K‑12 schools, and community colleges. The county auditor is responsible for allocating property tax revenue to these entities according to state law.

Property Tax Changes Can Affect School Funding and the State Budget. Proposition 98 (1988) establishes a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The guarantee encompasses state General Fund and local property tax revenue. A set of formulas in the State Constitution determines the guarantee each year. In certain years, the formulas provide that any changes to the amount of property tax revenue received by schools and community colleges have a dollar‑for‑dollar effect on the size of the guarantee. In other years, property tax changes affect the amount of General Fund the state must allocate to meet the guarantee.

ERAF Accounts Created in the Early 1990s. In the early 1990s, the Legislature permanently redirected a significant portion of the property tax revenue from cities, counties, and special districts to schools and community colleges. The redirected revenue is deposited into a countywide account known as ERAF. Revenue from ERAF is allocated to schools and community colleges to offset the funding these entities otherwise would receive from the state General Fund.

Excess ERAF Allocated to Noneducation Agencies. In a few counties, ERAF revenue is more than enough to offset all of the General Fund allocated to schools and community colleges. In the mid‑1990s, the Legislature enacted a law shifting the portion of ERAF not needed for schools and community colleges to other agencies in the county. The revenue shifted through this process is known as excess ERAF. As of 2018‑19, five counties have excess ERAF—Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara.

Findings and Concerns

Three Specific Concerns. We recently reviewed the calculation of excess ERAF in the five counties and identified three specific concerns. Our first concern is that counties are excluding charter schools from certain calculations related to excess ERAF. Our second concern relates to the way counties are accounting for the school share of property tax revenue formerly allocated to redevelopment agencies. (The state dissolved these agencies in 2011‑12.) Our third concern pertains to a provision of law known as minimum state aid. In each case, we believe counties are calculating excess ERAF in ways that are contrary to state law and shift too much property tax revenue from schools to other local agencies. All three concerns together affect more than $350 million in annual property tax revenue.

Concerns Affect Funding for the School System Overall. One potential misconception about our concerns is that they affect the budgets of individual schools within the five counties. As we discuss in this report, each concern affects the state’s entire school system. For example, to the extent counties incorrectly exclude charter schools, less funding is available for school districts, charter schools, and community colleges throughout the state.

Two Broader Concerns. First, we are concerned the current process for calculating excess ERAF provides an insufficient role for the state. We think the lack of state involvement is one reason the law has been implemented in ways the Legislature did not intend. Second, we are concerned that the state has a fragmented system for collecting ERAF data from the counties. This fragmentation makes the calculations difficult to monitor.

Administration’s Recent Actions

Administration Recently Began to Address Our First Concern. In February, the administration informed the five counties that it expects them to adjust their calculations to address the concern about charter schools. Our current understanding is that the counties have not yet provided a formal response to the administration. The administration also recently became aware of our other concerns related to redevelopment revenue and minimum state aid, but has not taken formal action on these issues.

Recommendations

Direct the Administration to Enforce State Law on All Three Issues. We credit the administration for its initial actions regarding our concern about charter schools. We would, however, recommend the Legislature direct the administration to enforce state law on our other specific concerns, including the treatment of redevelopment revenue and minimum state aid.

Monitor Potential Changes in School Funding. The Governor’s budget assumes the state resolves the concern about charter schools. If this issue were not resolved, however, school property tax estimates would be overstated by about $180 million per year relative to the Governor’s budget. On the other hand, if the administration successfully resolves the other two concerns, school property tax estimates would increase by about $170 million per year relative to the Governor’s budget. Under the Governor’s estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, any changes in property tax revenue would affect the size of the guarantee—and by extension, the amount of funding available for K‑14 programs.

Improve State Oversight Moving Forward. We recommend the Legislature task the California Department of Education or the Department of Finance with developing standardized procedures that all counties would use for the calculation of excess ERAF. We also recommend making one agency responsible for collecting the data necessary to verify these calculations. These improvements would make the calculations easier to monitor, promote greater consistency across the counties, and reduce the likelihood that any future changes to ERAF are implemented in ways the Legislature does not expect.

Introduction

Since the mid‑1990s, a state law has shifted some of the property tax revenue in certain counties from schools and community colleges to other local agencies. For historical reasons, the shifted revenue is known as “excess ERAF.” (The acronym refers to the local accounts—known as Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds—that facilitate the shift.)

We recently learned that a few counties have made changes to the way they calculate excess ERAF. The changes would increase the amount of property tax revenue shifted from schools to other local agencies by hundreds of millions of dollars per year. Under the constitutional formulas governing education funding, the changes would mean less revenue is available for school and community college programs in the 2020‑21 budget.

This report provides our assessment of the counties’ changes. It also reviews two other issues affecting the calculation of excess ERAF. The first section provides historical context and explains the relevant laws and formulas. The second section describes our findings and concerns. The third section reviews the recent actions taken by the Newsom administration. The final section contains our recommendations to the Legislature.

Background

This section provides background on property taxes in California and explains how they affect school funding. It then explains the purpose of the local accounts (pronounced “E‑RAF”) and the concept of excess ERAF. It ends by providing background on two related issues.

Property Tax Basics

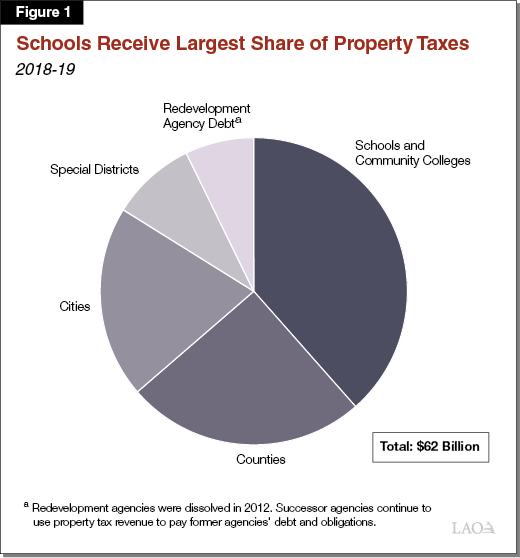

Many Local Agencies Receive Property Tax Revenue. Property owners in California pay a tax of at least 1 percent on the assessed value of their properties. The State Constitution requires the proceeds of the property tax to be allocated for local agencies in the county where the revenue is collected. Recipients of property tax revenue include cities, counties, special districts, K‑12 schools, and community colleges. The county auditor is responsible for allocating property tax revenue to these entities according to state law. The exact share of property tax revenue for each entity varies across the state, largely for historical reasons. On a statewide basis, schools and community colleges receive about 40 percent of all property tax revenue and other local agencies receive about 60 percent (Figure 1).

Property Taxes and School Funding

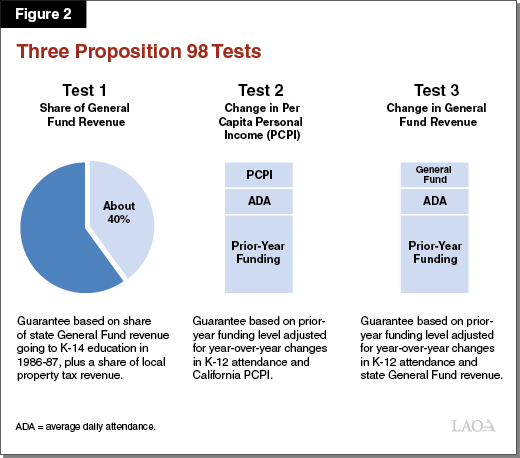

Proposition 98 Establishes Minimum Funding Level for Schools and Community Colleges. Proposition 98 (1988) establishes a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges, commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The guarantee encompasses state General Fund and local property tax revenue. The state determines the guarantee by calculating and comparing three main formulas, or “tests” (Figure 2). These tests depend upon various inputs, such as General Fund revenue and changes in student attendance. Depending on these inputs, one of the tests becomes operative and sets the minimum guarantee for that year.

Interaction Between Property Tax Revenue and the Proposition 98 Guarantee. The amount of property tax revenue received by schools and community colleges affects the Proposition 98 calculations. The effects vary, however, depending on which of the three tests is operative. In Test 1 years, the minimum guarantee equals a fixed percentage of state General Fund revenue, plus whatever amount of property tax revenue schools and community colleges receive that year. In Test 1 years, increases or decreases in property tax revenue have a dollar‑for‑dollar effect on school funding. When one of the other tests is operative, changes in property tax revenue do not affect the minimum guarantee or overall school funding. Instead, they affect the amount of General Fund the state must allocate to meet the guarantee.

State Law Allocates Funding to Districts Through Formulas. Whereas Proposition 98 establishes a total minimum funding level, the Legislature decides how to allocate this funding. For schools, the Legislature allocates most funding through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). This formula establishes a funding target for each school district based primarily on the number of students attending the district and the share of those students who are low income or English learners. For community colleges, the Legislature allocates most funding through apportionments. The apportionment formula establishes a target for each college district based on its enrollment (as measured by full‑time‑equivalent students), share of students who are low income, and performance on certain measures of student outcomes.

Districts Funded With Property Tax Revenue and State General Fund. The state counts the property tax revenue a school or community college district receives toward its funding target. The state then provides General Fund to make up the remaining difference. For the average district, property tax revenue covers the first 40 percent of its target and state General Fund covers the remaining 60 percent. The exact share varies widely across the state. For approximately 10 percent of school and community college districts, property tax revenues exceed their target. For historical reasons, these districts are known as “basic aid” districts. State law allows these districts to spend the additional revenue on their local education priorities.

Property Tax Shifts and Excess ERAF

ERAF Accounts Established in Early 1990s. During the early 1990s, the state experienced an economic recession and budget shortfalls. To help balance the budget, the state permanently redirected almost one‑fifth of statewide property tax revenue from cities, counties, and special districts to schools and community colleges. The redirected property tax revenue is deposited into an account in the county treasury known as ERAF. Initially, the operation of these accounts was relatively straightforward—all of the property tax revenue was distributed to schools and colleges within the county to offset revenue they would otherwise receive from the state General Fund. By increasing property tax revenue to schools, the ERAF shifts reduced the amount of General Fund needed to meet the Proposition 98 guarantee. Basic aid districts did not receive any allocations from ERAF because they received no General Fund revenue the state could offset.

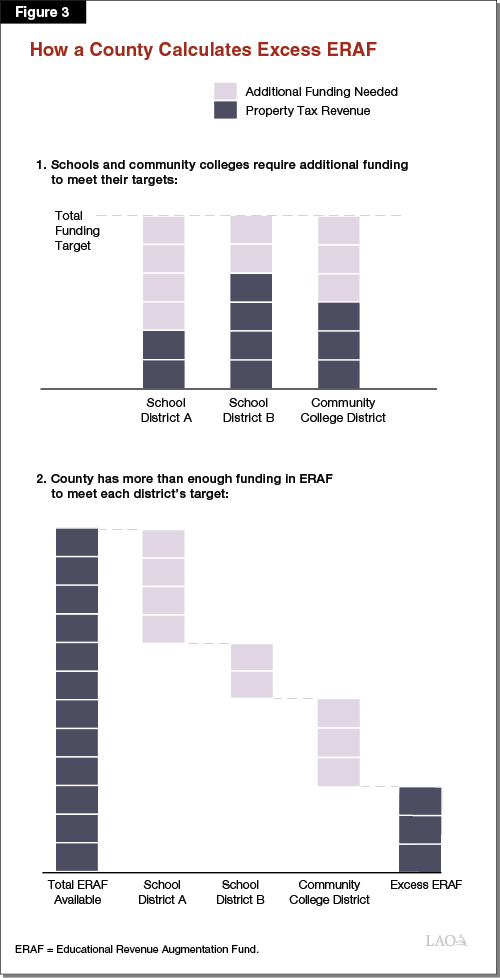

Local Agencies in Certain Counties Receive Excess ERAF. In 1994‑95, Marin County reported a new development—it had more than enough funding in ERAF to offset all of the General Fund its schools would receive from the state. At the time, the law did not specify how ERAF revenue above the amount needed for schools should be used. In response, the Legislature specified that some of the funds would be used for special education programs and the remainder would be allocated to other agencies in the county, including the county government, cities, and special districts. The ERAF funds allocated to noneducation agencies through this process are known as excess ERAF. An agency’s share of excess ERAF is proportional to the share of its property tax revenue originally shifted into ERAF. The agencies receiving excess ERAF may use it for any local purpose. Figure 3 illustrates how a county calculates excess ERAF.

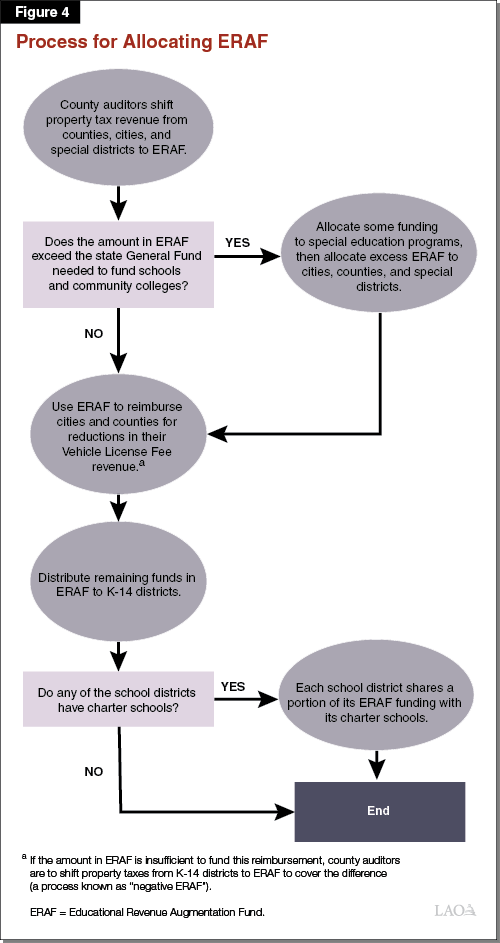

State Made Another Change to ERAF in 2004‑05. In 2004‑05, the state began directing county auditors to use funding in ERAF to reimburse cities and counties for a reduction in their Vehicle License Fee (VLF) revenue. (The VLF is a tax on vehicle ownership and a longstanding source of revenue for cities and counties. The state began reducing the VLF rate in the late 1990s.) This shift is known as the VLF swap. Although the VLF swap reduced the amount of property tax revenue in ERAF available to fund schools, state law specified that the shift would not affect the calculation of excess ERAF.

Current ERAF Allocation Process. Figure 4 shows how the various parts of the ERAF allocation process fit together. After shifting property taxes into ERAF, the county auditor compares the amount in ERAF with the amount of state General Fund that schools and community colleges would need to fund their targets. If the amount in ERAF is larger, the auditor allocates the difference to local agencies as excess ERAF. (If the amount is smaller, the auditor skips this step.) Next, the auditor subtracts funding from ERAF to reimburse cities and counties for the VLF swap. Finally, the auditor distributes the funds remaining in ERAF to schools and community colleges. The specific distribution of ERAF among the school districts in the county is determined by the county superintendent of schools.

Charter Schools Receive Property Tax Revenue Indirectly. Charter schools educate K‑12 students under locally developed agreements (or “charters”) that describe their educational goals and programs. Most charter schools are approved and monitored by the school districts in which they are located. The first charter schools opened in 1992‑93. Since that time, the Legislature has taken steps to integrate charter schools into the K‑12 funding system. For example, state law deems charter schools to be school districts for the purposes of allocating LCFF funding and meeting the Proposition 98 guarantee. Unlike school districts, however, charter schools do not receive an automatic allocation of property tax revenue. Instead, the law requires school districts to share their property tax revenue—including ERAF—by making payments in‑lieu of taxes to their charter schools. Generally, each charter school receives a share of the property tax revenue that is proportional to its share of students in the school district. The state then backfills the school district for the reductions to its property tax revenue. (Somewhat different rules apply for charter schools in basic aid school districts.)

Recent Trends in Excess ERAF

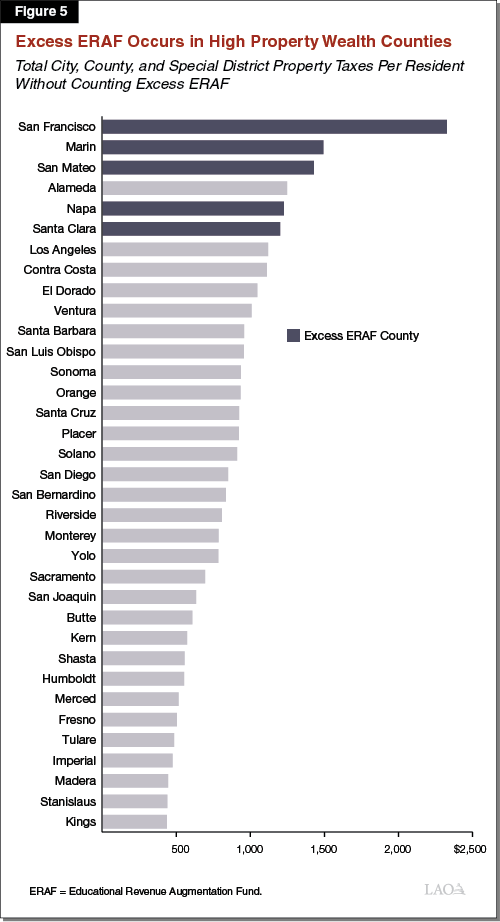

Five Counties Currently Report Excess ERAF. Until the mid‑2000s, Marin was the only county with excess ERAF. Since that time, four other counties in the Bay Area have joined Marin—San Mateo, San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Napa. San Francisco, the most recent addition, began reporting excess ERAF in 2016‑17. As Figure 5 shows, all of these counties have very high levels of property tax revenue relative to their overall populations. High levels of property tax revenue increase the total amount of funding shifted into ERAF and, by extension, the likelihood of having excess ERAF.

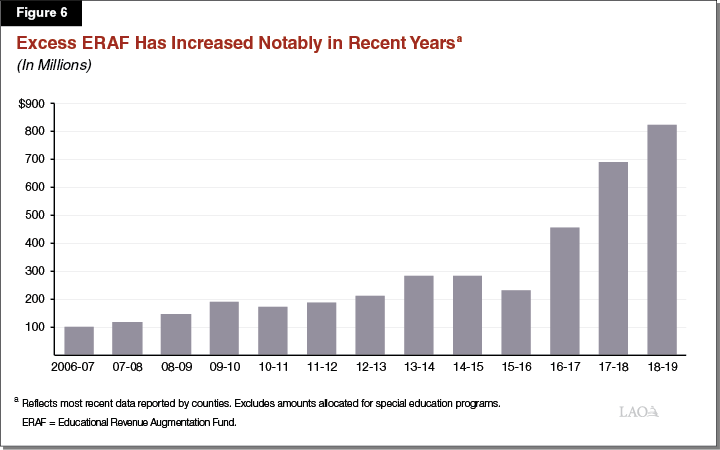

Excess ERAF Has Grown Rapidly in Recent Years. Figure 6 shows how the amount of excess ERAF reported by counties has changed over time. In 2006‑07, counties reported excess ERAF totaling about $100 million—equating to about 1.5 percent of all property tax revenue allocated from ERAF accounts statewide. Over the next decade, excess ERAF grew steadily. Within the past three years, however, growth in excess ERAF has accelerated. Preliminary reports show excess ERAF totaling $820 million in 2018‑19—equating to about 8 percent of all funding allocated from ERAF statewide. Several factors explain this large uptick. Most notably, San Francisco became an excess ERAF county beginning in 2016‑17. In 2017‑18, growth in property tax revenue among Bay Area counties was particularly strong relative to the increase in school funding that year. County decisions about the calculation of excess ERAF have also played an important role, as discussed later in this report.

Redevelopment Dissolution

Dissolution of Redevelopment Increased Property Tax Revenue for Schools and Other Local Agencies. Prior to 2011‑12, the state had more than 400 redevelopment agencies engaged in various redevelopment projects around the state. Redevelopment agencies financed their activities using a portion of the property tax revenue collected in their jurisdictions. The 2011‑12 budget package dissolved redevelopment agencies effective February 2012. Under the dissolution process, property tax revenue formerly allocated to these agencies is used first to pay off redevelopment debts and obligations. The remaining revenue is distributed to schools, community colleges, and other local agencies. Each agency’s share of this revenue generally is proportional to its share of all other property tax revenue. As former redevelopment debts and obligations are retired, these distributions will grow over time.

State Law Specified That Dissolution Would Not Increase Excess ERAF. By increasing school property tax revenue, the dissolution of redevelopment also reduced the amount of General Fund needed to fund schools. For counties with excess ERAF, these changes presented a complication. Specifically, the redevelopment revenue allocated to schools in these counties would have reduced the funding schools could receive from ERAF and increased excess ERAF. As a result, schools would have not experienced an overall increase in their property tax revenue. To prevent this unintended outcome, the Legislature passed Chapter 26 of 2012 (AB 1484, Committee on Budget). This legislation instructed county auditors not to increase excess ERAF as a result of any revenue attributable to the dissolution of redevelopment. (The funding that remains in ERAF as a result of this law is available to pay for the VLF swap and fund schools.)

Minimum State Aid

School Districts Receive a Minimum Level of State Funding. Certain provisions of the California Constitution and state law guarantee all school districts a minimum level of funding from the state General Fund. Generally, this minimum equals the amount of state funding each district received in 2012‑13 (the year prior to the creation of LCFF) or $120 per student, whichever is higher. For most school districts, this “minimum state aid” counts toward meeting their LCFF targets. (Basic aid districts are an exception, as they receive minimum state aid on top of their targets.)

Minimum State Aid Increases Excess ERAF. When counties are calculating excess ERAF, they determine how much General Fund revenue allocated to schools could be replaced with property tax revenue. Minimum state aid, however, represents General Fund revenue a school district will receive regardless of its property tax revenue. The law is implemented such that the portion of each district’s target covered by minimum state aid cannot be replaced with ERAF. In other words, minimum state aid reduces the amount of ERAF that can be allocated to the schools within a county. Reducing the amount of ERAF allocated to schools, in turn, results in more excess ERAF being allocated to other agencies.

Findings and Concerns

This section explains three specific concerns we identified in our review of the calculation of excess ERAF. It also explains two broader concerns we have about the oversight of these calculations.

We Recently Reviewed Excess ERAF Calculations in the Five Counties. For our review, we examined county calculations, spoke with local officials, and reviewed relevant state law. We identified three specific concerns regarding the calculation of excess ERAF, which are summarized in Figure 7. The first relates to the treatment of charter schools, the second to the dissolution of redevelopment, and the third to the calculation of minimum state aid. In each case, our concern is that certain counties are calculating excess ERAF in ways that shift too much property tax revenue from schools to other local agencies. Apart from the three specific issues, we have two broader concerns that we describe at the end of this section.

Figure 7

Three Specific Concerns About Excess ERAF Calculations

|

Issue |

Concern |

Revenue Shifted From Schools to Other Agenciesa |

Amount Shifted Over Three‑Year Budget Perioda |

|

Treatment of charter schools |

Counties excluding charter schools from calculation of excess ERAF. |

$180 million |

$540 million |

|

Implementation of redevelopment dissolution |

Counties allowing redevelopment revenue to increase excess ERAF. |

$170 million |

$510 million |

|

Calculation of minimum state aid |

At least one county overcounting minimum state aid, which increases excess ERAF. |

$2 million |

$6 million |

|

aReflects estimates based on available data and our understanding of counties’ current practices. ERAF = Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund. |

|||

Concerns Affect Funding for the School System Overall. One potential misconception about our findings is that they affect the budgets of individual schools within the five counties. In fact, each issue affects the state’s entire school system. To the extent a county allocates too little ERAF to schools, the state provides more General Fund. Depending upon which test is operative for calculating the Proposition 98 guarantee, the cost of this backfill results in (1) less overall funding for school and community college programs (when Test 1 applies), or (2) higher General Fund costs for the state (when another tests applies).

Three Specific Concerns

Counties Are Increasing Excess ERAF by Excluding Charter Schools... The amount of excess ERAF in a county depends upon the difference between the amount of (1) ERAF revenue available and (2) General Fund revenue that schools within the county are eligible to receive. We recently learned that two counties have been excluding charter schools from this second amount for the past few years. That is, these counties are treating charter schools as though they receive no General Fund revenue that could be replaced with ERAF. By reducing the ERAF allocated for schools, this practice increases excess ERAF. We also learned that other excess ERAF counties—which previously included charter schools—began excluding them in their most recent calculations. Across all five counties, we estimate the exclusion of charter schools would shift roughly $180 million per year in property tax revenue from schools to other local agencies.

…Even Though State Law Includes Charter Schools. State law specifically allocates ERAF and other property tax revenue to charter schools through their school districts. This property tax revenue offsets the General Fund revenue charter schools otherwise would receive from the state. The counties’ approach, however, would involve calculating excess ERAF as though these parts of the allocation process did not exist. The overall effect would be to reduce the amount of ERAF revenue available for allocation to the school districts in the county. (Charter schools would experience the reduction indirectly, in the form of smaller payments in‑lieu of taxes.) This approach also runs counter to various state laws declaring charter schools to be school districts for funding purposes such as LCFF.

Redevelopment Revenues Are Increasing Excess ERAF. Though state law provides that redevelopment revenue allocated to schools should not increase excess ERAF, we found that the five counties are not implementing this provision. Instead, redevelopment revenues are displacing property tax revenue that schools otherwise would receive from ERAF. This means that revenues intended to benefit schools are instead benefitting cities, counties, and special districts through additional excess ERAF. We estimate this practice is shifting roughly $170 million per year from schools to other local agencies.

At Least One County Is Increasing Excess ERAF by Over Counting Minimum State Aid. A third, much smaller concern relates to the calculation of minimum state aid. We found that at least one county is assuming its school districts receive more minimum state aid than the law actually provides. This assumption reduces the amount of ERAF that can be allocated to schools. Excess ERAF, in turn, increases by a corresponding amount. We estimate this practice is shifting at least $2 million per year from schools to other local agencies. (Technically, this issue stems from the assumption that school districts receive both $120 per student in state funding and the amount received in 2012‑13, whereas the law specifies that the minimum level be based on one of these amounts.)

Two Broader Concerns

State and Schools’ Interests Not Sufficiently Represented. Although each of our specific concerns is rooted in a different part of law, taken together we think they illustrate a broader concern. Each year, the property tax produces a finite amount of revenue for the agencies within each county. The state and schools share an interest in maximizing the revenue allocated for schools, as this revenue results in either more overall school funding or lower state General Fund costs. Conversely, other local agencies share an interest in maximizing their share of the property tax revenue. This trade‑off provides an incentive for counties to implement the law in ways that increase their share of the property tax revenue, particularly when so many different steps are involved in the calculation. We think the lack of state involvement in the ERAF allocation process is one reason the law is being implemented in ways the Legislature did not intend.

State Has Difficulty Monitoring the Calculation of Excess ERAF. Two main issues limit the state’s ability to monitor the calculation of excess ERAF. First, the implementation of the law varies from county to county. Each county uses its own procedures to calculate excess ERAF. The five counties, for example, implemented the decision to exclude charter schools differently. Second, the state has not assigned responsibility for collecting ERAF data to any single agency. Instead, this responsibility is spread across multiple agencies including the State Controller’s Office (SCO), California Department of Education (CDE), and the Department of Finance (DOF). For example, the SCO collects information on the total amount of property tax revenue shifted into ERAF, but CDE collects information on excess ERAF. Due to these two issues, the state has difficulty monitoring the calculations, identifying errors or inconsistencies, and projecting how the amount of excess ERAF might change in the future.

Administration’s Recent Actions

This section explains the Governor’s recent actions related to excess ERAF and the assumptions embedded in the administration’s property tax estimates.

Administration Recently Began to Address Concern About Charter Schools. The administration indicates it is concerned about the exclusion of charter schools from the calculation of excess ERAF. In February, the administration informed the five counties that it expects them to revise their calculations to include charter schools. We understand that as of this writing, the counties have not formally responded to the administration. The administration also recently became aware of our concerns related to the treatment of redevelopment revenue and minimum state aid, but has not taken any formal action on these issues.

Property Tax Estimates Assume Charter Schools Are Included. The Governor’s budget estimates that total property tax revenue for schools and community colleges will be $23.9 billion in 2018‑19, $25.2 billion in 2019‑20, and $26.5 billion in 2020‑21. These estimates assume all counties include charter schools for each year of the period. Regarding our other concerns, the budget assumes no changes to the way counties currently account for redevelopment revenue or minimum state aid.

Changes to Property Tax Revenue Would Affect Overall School Funding. The Governor’s budget projects that Test 1 is the operative test for calculating the Proposition 98 guarantee each year of the period. As a result, any changes to property tax revenue would increase or decrease the minimum guarantee—and the funding available for schools and community colleges—on a dollar‑for‑dollar basis.

Recommendations

This section explains how we suggest the Legislature respond to our specific concerns and the steps we recommend to prevent similar concerns from arising in the future.

Direct the Administration to Enforce State Law on All Three Issues. We credit the administration for its initial actions to ensure charter schools are included the calculation of excess ERAF. We would, however, recommend the Legislature direct the administration to enforce the law on all of our concerns, including the treatment of redevelopment revenue and minimum state aid. All three issues involve the calculation of excess ERAF in ways that seem contrary to state law and shift too much property tax revenue to noneducation agencies.

Monitor Potential Changes in School Funding. Taken together, our three specific concerns affect the allocation of approximately $350 million in property tax revenue per year. Over the 2018‑19 through 2020‑21 period, the amount is more than $1 billion. The Governor’s budget assumes the state is able to address the charter school issue, which accounts for about half of this amount. If the administration successfully resolves the other two issues, annual property tax revenue for schools—and the Proposition 98 guarantee—would be around $170 million higher than the estimates in the Governor’s budget (about half a billion dollars over the three years). Due to the potential swings in funding, we advise the Legislature to monitor the state’s progress on these issues.

Improve State Oversight Moving Forward. We recommend the Legislature address our two broader concerns by improving state oversight. Specifically, we recommend the following:

- Develop Clear, Consistent Procedures. We recommend the Legislature task CDE or DOF with developing standardized procedures that all counties would use for the calculation of excess ERAF. We envision these procedures including instructions and a template to ensure compliance with all of the applicable state laws. We think the Legislature could ask each agency to explain what resources it would need for this task, then choose the most cost‑effective option.

- Improve Data Collection. We recommend the Legislature task CDE with collecting all of the relevant data necessary to verify the calculation of excess ERAF. Having one agency collect the data in a consistent manner would allow the state to ensure counties are following the new instructions. Given that CDE already collects certain property tax data, we think the cost of collecting the additional information would be modest.

By improving oversight, these changes would help ensure that the interests of the state and schools are better represented in the ERAF allocation process. They also would make the calculation of excess ERAF easier to monitor and promote greater consistency across the counties. Finally, our recommendations would reduce the likelihood that future changes to school funding or property tax laws affect the allocation of ERAF in ways the Legislature does not expect. If the Legislature were to adopt these recommendations as part of the June budget package, we think they could be implemented during the 2020‑21 fiscal year.

Conclusion

Excess ERAF Is Likely to Remain a Significant Issue. Over the past several years, excess ERAF has come to affect five counties and hundreds of millions of dollars in property tax revenue each year. As property values continue to rise, this shift is likely to affect an even larger share of the property tax revenue in those counties—and potentially additional counties. These trends highlight the importance of understanding the calculation of excess ERAF and ensuring effective state oversight. They also suggest that excess ERAF is likely to be an important factor affecting the budget picture for schools and other local agencies for many years to come.