LAO Contacts

March 10, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Proposition 2 Debt Payment Proposals

Summary

Proposition 2 Represents a Unique Opportunity for State Over Next Decade. Under the provisions of Proposition 2 (2014), the state is required to dedicate annual amounts to accelerate the pay down of state debts. These annual payments will represent a substantial sum of money—$12 billion to $21 billion—over the next ten years and must be dedicated to a limited set of uses, namely to pay down the state’s unfunded liabilities related to retirement. As such, Proposition 2 represents a key and unique opportunity for the state. This report presents our recommendations for how the state can use Proposition 2 debt payments most strategically over the next decade.

Teachers’ Pensions and Retiree Health Both Have New Funding Plans. In 2014, the state adopted a plan to fully fund the teachers’ pension program in response to projections suggesting the system would fully deplete its assets by the mid‑2040s. Also, in 2015, the state began implementing a plan to prefund retiree health benefits—that is, setting aside money today to fund benefits in the future. Both of these plans represent a significant step forward. These plans position the state to address both outstanding retirement liabilities over the next few decades, however, they also face limitations that could prevent them from staying on track.

Agree With Governor’s Strategy on Teachers’ Pensions… The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposal offers one strategy to prioritize Proposition 2 funds in 2020‑21 and over a multiyear period. One notable feature of the plan is the Governor’s proposal to address a portion of the state’s share of the unfunded liability for teachers’ pensions. Under the Governor’s plan, the state would provide nearly $3 billion to this purpose over a multiyear period. We agree that focusing Proposition 2 debt payments on this purpose makes sense.

…But Not Specific Choices. The amounts the Governor proposes dedicating to teachers’ pensions both in 2020‑21 and in future years are not connected to the specific actuarial needs of the system, however. As such, these additional contributions could fall short of the amounts the system will actually need to stay on track. In this report, we present a method that the Legislature could use to tie additional supplemental contributions to the system’s actuarial needs. In addition, while the Governor does not propose dedicating additional amounts to retiree health, we think some payments could be warranted. In particular, if—after addressing teachers’ pensions—additional Proposition 2 capacity remains in future years, we think it makes sense to use this funding for the state’s retiree health program.

Recommend Closer Monitoring—and Tailoring Proposition 2 Funding—to Keep Funding Strategies on Track. While this report outlines a general approach for addressing possible future costs, the amounts needed to accomplish these goals are not yet known. As such, to implement this approach, we recommend the Legislature adopt trailer bill language directing the administration to report, at the time of its January budget proposal each year, on a few different aspects of the teacher pension and retiree health funding plans. This reporting language would allow the state to: (1) better monitor progress on the funding plans and (2) target funding to reduce the risk that those plans get off track over the next decades.

Introduction

Proposition 2 was added to the November 2014 ballot in a special legislative session under ACAX2 1 (Pérez) and subsequently was approved by voters. The measure made significant changes to the state constitution concerning budgeting practices. In particular, in addition to requiring annual deposits into the state’s rainy day fund, it requires the state to make additional debt payments each year until 2030. The intent of Proposition 2 was to improve the state’s fiscal situation—for example, by “repay[ing] state debts and protect[ing] the state from the negative effects of economic downturns.”

Until last year, most of the state’s Proposition 2 debt‑related payments were directed toward paying off loans the state took out to address its past budget problems. However, additional payments made as a part of the 2019‑20 budget essentially eliminated these types of debts. As such, the Legislature now has an opportunity to rethink its long‑term strategy for Proposition 2 debt payments.

The remaining eligible uses of Proposition 2 debt payments mainly are related to retirement liabilities. While California has hundreds of billions of dollars in unfunded retirement liabilities, the state also has several plans in place to address those liabilities over the next few decades. Some of those plans, however, are still relatively new and there is a chance they could fall short of meeting their goals.

Meanwhile, the Proposition 2 debt requirements, while wholly insufficient to address the state’s total retirement liabilities, will represent a substantial sum of money—$12 billion to $21 billion over the next ten years. As we discuss in this analysis, these funds—and the requirement to spend them on certain limited uses— represent a key and unique opportunity for the state. The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposal has one plan for how to allocate the funds. This report presents our recommendations for how the state can adjust this plan to most strategically deploy this Proposition 2 funding.

Background

This section provides background on how Proposition 2 debt payment requirements are estimated and on the state’s major retirement liabilities—the remaining eligible uses of those payments.

Debt Payments Required Through 2029‑30

Proposition 2 Required Debt Payments Vary Significantly From Year to Year. Proposition 2 contains a formula that requires the state to spend a minimum amount each year to pay down specified debts. The formula has two parts. First, the state must set aside 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues. Second, the state must set aside a portion of capital gains revenues that exceed a specified threshold. The state combines these two amounts and then allocates half of the total to pay down eligible debts and the other half to increase the level of the rainy day fund (the Budget Stabilization Account). Because capital gains revenues can vary significantly from year to year, the annual amount of the Proposition 2 required debt payment has varied by hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

Dedicates Annual Payments—Even During Downturns—Toward Eligible Debts Until 2030. Proposition 2 debt payments are required through 2029‑30. Thereafter, these debt payments become optional, but amounts not spent on debt must be deposited into the rainy day reserve. Unlike reserve requirements, which the Governor and Legislature may reduce during a budget emergency, the state cannot reduce required debt payments before 2030 for any reason.

Over the Next Decade, State Will Make Between $12 Billion and $21 Billion in Additional Debt Payments. Debt payment requirements will vary depending on revenue performance. For example, in a recessionary year when the stock market declines substantially over several months, the annual requirement could be as low as $900 million. In other years, when capital gains revenues are more significant, the annual requirement could reach well over $2 billion. We estimate that, over the next ten years, the state will make $12 billion to $21 billion in additional debt payments under Proposition 2. (In addition to these requirements, outside of Proposition 2, the state makes several billions of dollars in annual debt payments under a number of other state policies. These are described in more detail in the nearby box.)

Proposition 2 Is One Part of the State’s Debt Approach

Beyond Proposition 2’s (2014) requirements, the annual budget pays down several billion dollars of liabilities each year. These include costs to pay down pension unfunded liabilities and debt service on bonds. For example, in addition to $1.9 billion in Proposition 2 debt payments, the 2018‑19 budget allocated about $4 billion to pay down the unfunded liability for state and California State University employee pension benefits and $6.2 billion for debt service on general obligation bonds.

No State Policy for All Proposition 2 Debt Payments Beyond 2019‑20. The state has generally approached annual debt payments on a year‑by‑year basis, meaning there is no formal multiyear policy on how these payments will be distributed over the next decade. The administration, however, maintains its own multiyear plan for Proposition 2 debt payments that it updates with each budget proposal. The administration’s current Proposition 2 debt payment plan, which is reflected in the Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposal, extends through 2023‑24. While the administration’s budget proposal makes assumptions about future Proposition 2 payments, the Legislature may choose to use these funds differently.

Last Year’s Budget Paid Down Most of State’s Remaining Budgetary Debt. At the time the measure was passed, there were five types of debts eligible for payments under Proposition 2. These were: (1) “settle up” or certain amounts the state owed to schools; (2) special fund loans from other state funds to the General Fund; (3) reimbursements for pre‑2004 mandate claims from cities, counties, and special districts; (4) unfunded liabilities for pensions; and (5) prefunding and unfunded liabilities associated with retiree health benefits. As of the 2019‑20 budget, the state has repaid the first three types of eligible Proposition 2 debts (that is, settle up, special fund loans, and mandate claims).

Remaining Eligible Uses of Proposition 2 Debt Payments

The remaining eligible uses of Proposition 2 mainly are related to unfunded liabilities for pensions and retiree health benefits. Figure 1 summarizes those eligible uses that are the sole responsibility of the state. While these amounts are large, the state has plans in place to address these liabilities over the next few decades. The remainder of this section describes each of the eligible uses and provides detail on how these plans would work.

Figure 1

Outstanding State‑Only Eligible Uses of Proposition 2

Debt or Liability (In Billions)

|

Retiree health |

$85.6 |

|

State and CSU employee pensions |

59.7 |

|

Teachers’ pensionsa |

33.4 |

|

Judges’ pensions |

3.3 |

|

Pooled Money Investment Account loanb |

2.5 |

|

aState’s share of the unfunded liability. bGeneral Fund’s share of the remaining repayments. Total outstanding repayments owed are $5.1 billion, including interest. |

|

State Retiree Health

The state provides health benefits to retired state employees. Prior to 2015, the state essentially put no money aside to pay for this benefit while the eventual retiree was still working. As a result, the state accrued a significant unfunded liability associated with retiree health. (An unfunded liability occurs when the assets that have been set aside during a retiree’s working years are insufficient to pay their future benefits—in this case, there were no assets set aside for these workers for decades.) In 2015‑16, the state began a policy to prefund this benefit by setting aside funds annually. (Over the last few years, the state’s General Fund costs of prefunding have been paid using Proposition 2.) The state retiree health unfunded liability is estimated to be $86 billion as of the most recent actuarial valuation.

State and Employees Recently Began Making Regular Contributions Based on Normal Cost. Under the new policy to prefund retiree health, the state and employees each pay a percent of pay intended to equal one‑half of the normal cost so that the entire normal cost is paid each year. (Normal cost is the amount that actuaries estimate is necessary to be invested today to pay for the benefit in the future.) Actuarial valuations provided to the Legislature at the time the state adopted the funding plan indicated that, using this strategy, the benefit would be fully funded by the mid‑2040s under the plan. This projection is based on a number of assumptions about the future, including: benefit design and assumptions about investment returns, health care inflation, and demographic trends.

State and CSU Employee Pensions

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) administers pension benefits for state employees, state judges, certain elected state officials, and employees of local governments that contract with CalPERS (and their beneficiaries). Unfunded liabilities emerge at CalPERS when actuaries determine that there are insufficient assets invested today to make benefit payments in the future for earned benefits. For example, when investment returns on assets are lower than actuaries assumed in a particular year, an unfunded liability is created that will be paid off by the state over a couple of decades. The state’s unfunded liabilities at CalPERS total about $63 billion, which includes about $60 billion associated with state and California State University (CSU) employee pension benefits and about $3 billion associated with pension benefits for judges first appointed or elected before 1994.

CalPERS Has Full Rate Setting Authority. A pension system has “full rate setting authority” when its board has the authority to require employers to contribute an amount of money that the board determines is necessary to fund the system. With full rate setting authority, contribution requirements might change year over year in response to actuarial changes. For example, contribution requirements might increase if retirees live longer in the future than expected or decrease if investment returns are higher than actuaries assumed. This rate setting authority is important because it allows the system to (1) make up for losses that occur when actuaries determine that more funds are necessary to pay for benefits than what has already been set aside (that is, to address an unfunded liability over time) and (2) not charge employers more than is necessary for the system to become fully funded. Under the California Constitution, CalPERS has full rate setting authority.

Teachers’ Pensions

The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) administers pension and other retirement programs for current, former, and retired K‑12 and community college teachers and administrators, as well as their beneficiaries. According to CalSTRS’ most recent actuarial valuation, total unfunded liabilities for its defined benefit program are $107 billion. Under state law, currently about one‑third of these liabilities are the responsibility of the state ($33 billion) and about two‑thirds are the responsibility of school districts. (Figure 1 displays only the state’s share of the unfunded liability, but the districts’ share also arguably is eligible for Proposition 2 payments.)

Prior to 2014, CalSTRS Was on Path to Fully Deplete Assets by Mid‑2040s. Benefits for CalSTRS members are funded from a combination of investment returns, contributions from employers (which we refer to as “districts”), employees (teachers), and the state. Prior to 2014, base contribution rates paid by districts, teachers, and the state were established in statute, and the CalSTRS board had limited authority to set a supplemental contribution rate for the state. Like other pension systems, CalSTRS incurred significant investment losses during the 2008 financial crisis. However, unlike other pension systems, given its constraints, CalSTRS projected those losses would result in the system running out of assets in the mid‑2040s.

2014 Funding Plan Aims for System to Be Fully Funded by 2046. In 2014, the Legislature approved a plan (Chapter 47 [AB 1469, Bonta]) to fully fund the CalSTRS defined benefit program by 2046 (we refer to this as the “funding plan”). To reach that goal, the funding plan statutorily assigned existing unfunded liabilities to districts and the state. The funding plan also scheduled increases to the contribution rates paid by districts, teachers, and the state to the system for several years and—after that point—granted the CalSTRS board limited rate setting authority.

CalSTRS Board Has Limited Rate Setting Authority. Unlike CalPERS, the CalSTRS board has limited—not full—rate setting authority under the funding plan. Specifically, the funding plan phased in increases to the state’s contribution rates until 2016‑17, after which the funding plan gave the CalSTRS board limited authority to adjust those rates. In particular, the board may increase the state’s rate by 0.5 percent of pay each year. Figure 2 shows current and expected future contribution rates under CalSTRS’ current projections. Under these projections, the state’s rate is expected to continue to increase over the next few years in response to recent actuarial losses (for example, years in which CalSTRS’ investments have earned less than the actuarially assumed 7 percent).

Figure 2

CalSTRS Expected Future State Contribution Rates

|

Fiscal Year |

State Ratea |

|

2019‑20 |

10.3% |

|

2020‑21 |

10.8 |

|

2021‑22 |

11.3 |

|

2022‑23 |

11.8 |

|

2023‑24 |

11.6 |

|

aIncludes the required contribution to the Supplemental Benefit Maintenance Account. |

|

Other Eligible Uses

General Fund Repayments to PMIA Loan. The 2017‑18 budget package authorized a plan to borrow $6 billion from the state’s share of the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA)—an account that is like the state’s checking account—to make a one‑time supplemental payment to CalPERS. The General Fund and all other funds that make CalPERS payments on behalf of employees will save money from the supplemental payment. This is because supplemental payments reduce the system’s unfunded liability, resulting in lower employer contributions over time. Because all funds that contribute to CalPERS will experience savings, they are all expected to contribute toward the repayment of the loan. The General Fund’s share of the remaining outstanding loan balance is $2.5 billion.

University of California (UC) Pension Liabilities Also Eligible. In addition to the retirement liabilities described earlier, unfunded liabilities of the UC Retirement Plan (UCRP) also are eligible for Proposition 2 payments. Unlike most pension systems in California, the UC pension plan was “superfunded” for many years, meaning the system had more than enough assets to pay future benefits. In response to this status, the UC Regents (which serves as the pension board of UCRP) allowed a “funding holiday” for nearly two decades during which neither UC nor its employees made pension contributions. This funding holiday eventually resulted in an unfunded liability. In 2009, the UC Regents adopted a funding plan to reinstate contributions to UCRP. As of the most recent actuarial valuation, UCRP’s unfunded liability is estimated to be $16.6 billion.

State Has Used Proposition 2 to Pay for UCRP in the Past. In three years since 2014, the state made contributions to UCRP using Proposition 2 funds. The state does not have a direct legal obligation to provide funding to the UC specifically to pay for its retirement liabilities. (As a result, we do not display UCRP in Figure 1.) As contributions to pay down retirement liabilities take up a larger share of UC’s budget, however, there could be pressure on the state to provide General Fund augmentations to UC.

Governor’s Proposition 2 Proposal

This section describes the Governor’s proposal for allocating the required Proposition 2 debt payments in 2020‑21 and over a multiyear period.

Governor’s Proposal for 2020‑21

Total Requirement of $2 Billion. The administration estimates that required debt payments will total $2 billion in 2020‑21. These requirements are based on the administration’s January 2020 estimates for 2020‑21 General Fund revenues and tax proceeds, personal income taxes derived from capital gains, and the share of excess capital gains that the Constitution requires the state to spend on education. The estimates of these amounts—and therefore of required debt payments—will change when the administration releases its revised budget plan in May 2020.

Proposed Allocation. The Governor proposes allocating the $2 billion requirement to three purposes in 2020‑21:

- Retiree Health Prefunding. The Governor first uses $340 million of this requirement for the General Fund cost of prefunding retiree health benefits. The state has been using Proposition 2 to cover these costs since the retiree health prefunding policy was adopted in 2015‑16.

- PMIA Loan Repayments. Next, the administration dedicates $817 million of the total to continue repaying the General Fund’s share of the PMIA loan. This payment would reduce the outstanding balance owed by the General Fund on this loan to $1.7 billion.

- CalSTRS Supplemental Payment. Finally, the administration proposes using $802 million to make a supplemental payment to the state’s share of CalSTRS’ unfunded liability. The state also made a supplemental payment of $1.1 billion to CalSTRS in 2019‑20 using the Proposition 2 debt payment requirement.

Governor’s Multiyear Plan

The Governor’s current multiyear plan for Proposition 2 debt payments extends through 2023‑24.

Estimates of Multiyear Requirements. The administration’s estimates of multiyear Proposition 2 debt payment requirements are based on the administration’s multiyear revenue estimates. These estimates assume the economy continues to grow and that the stock market grows slowly. These assumptions result in moderate Proposition 2 requirements each year—ranging from $1.5 billion to $1.8 billion over the out‑year period. The actual requirements will differ from the administration’s estimates in any given year, depending primarily on the performance of the stock market.

Multiyear Plan. The Governor’s multiyear plan for allocating those estimated requirements has a few parts. First, the Governor proposes to continue using Proposition 2 to prefund retiree health benefits. Second, he proposes fully paying down the General Fund’s share of the outstanding PMIA loan by 2022‑23. Next, the Governor proposes continuing to make supplemental payments to CalSTRS until the total amount of Proposition 2 supplemental payments reach nearly $3 billion in 2022‑23. Finally, after the PMIA loan is fully paid off in 2022‑23, he proposes directing the freed up Proposition 2 capacity to make a supplemental payment to CalPERS in 2023‑24. Figure 3 summarizes the plan. Because the Proposition 2 requirements will differ in amounts in future years, how the Governor actually proposes to use those funds will likely differ from what is included in the current multiyear plan.

Figure 3

Administration’s Multiyear Proposition 2 Plan

(In Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

|

Retiree health prefunding |

$340 |

$350 |

$365 |

$375 |

|

Pooled Money Investment Account loan repayments |

817 |

791 |

871 |

— |

|

Supplemental payments to CalSTRS |

802 |

615 |

345 |

— |

|

Supplemental payments to CalPERS |

— |

— |

— |

1,123 |

|

Totals |

$1,959 |

$1,756 |

$1,581 |

$1,498 |

Savings Assumed in Mulityear. In addition to reducing unfunded liabilities, another goal of supplemental payments is to generate state savings. Savings occur when the state pays down an unfunded liability and that payment lowers contribution rates relative to what otherwise would be the case over the next few decades. The administration’s January multiyear budget plan assumes savings associated with the supplemental CalSTRS payments beginning in 2022‑23. Since the administration put together these estimates, however, the CalSTRS board has adopted some changes to assumptions that result in increases to the state’s rate. This likely means that, when the administration releases a revised budget at the time of May Revision, it likely will assume a couple hundred millions of dollars in higher CalSTRS costs in the last years of the multiyear budget plan.

Findings and Recommendation

This section provides our assessment of the Governor’s Proposition 2 proposal. In the first section, we provide our overall comments on the plan, in particular the multiyear strategy for Proposition 2. In the second section, we present two ways to improve the Governor’s multiyear plan for Proposition 2. We conclude with a recommendation to the Legislature outlining an approach to implement our improvements.

Agree With Governor’s Approach to Maintain Current Commitments. We agree with the Governor’s approach to maintain the state’s commitments to prefunding retiree health and repaying the PMIA loan using Proposition 2. With regard to retiree health, now that prefunding costs are being shared through collective bargaining, the General Fund generally is obligated to cover them whether or not the state uses Proposition 2. Likewise, now that the PMIA loan has been made, the state is obligated to repay it whether or not Proposition 2 is used. That said, these payments could be reduced somewhat over the next few years, relative to the Governor’s proposal. In particular, the state has until 2029‑30 to repay the PMIA loan. The Legislature could choose to spread out the payments over a longer period, making more room for other priorities over the next few years.

Agree With Governor’s Approach to Focus on CalSTRS… If the Legislature wants the CalSTRS funding plan to stay on track to meet its goal of full funding by 2046, given CalSTRS’ limited rate setting authority, the state might need to ramp up contributions faster than currently scheduled. The Governor’s multiyear plan for Proposition 2 addresses this need by devoting nearly $3 billion in additional funds to CalSTRS over a few years.

…But Suggest Connecting Those Amounts to Specific Actuarial Need. The Governor has targeted multiyear supplemental payments of nearly $3 billion to CalSTRS. (We understand that the underlying rationale for this amount is that it is close to the amount the 2019‑20 budget dedicated to CalPERS for the same purpose.) While we agree with the Governor’s emphasis on CalSTRS over the multiyear period, the amounts proposed by the Governor are not connected to a specific actuarial need. Although making these payments would reduce CalSTRS’ unfunded liability and put the plan on better footing, because they are not estimated based on the actuarial needs of the system, they might fall short of the amounts the system will need to stay on track.

Recommend Improvements to the Multiyear Plan to Keep Funding Strategies on Track. The Constitution requires the state to make Proposition 2 debt payments each year for the next decade. At the same time, the state has relatively new plans in place to address unfunded liabilities for CalSTRS and state retiree health benefits that might not succeed in fully addressing the unfunded liabilities over the next few decades. (We describe why these plans might not fully address the unfunded liabilities in more detail later.) As such, Proposition 2 presents an opportunity for the state to assist in keeping these plans on track. In the remainder of this section, we outline a recommendation that would: (1) allow the state to better monitor progress on the funding plans and (2) target funding to reduce the risk that those plans get off track over the next decade.

Use Proposition 2 Payments to Keep Funding Plans On Track

CalSTRS

Funding Plan Is Still Relatively New, but Represents Significant Step Forward for the State. Under current actuarial and demographic assumptions—despite the limitations on CalSTRS’ rate setting authority—the system’s unfunded liabilities likely will be reduced by 2046‑47. As we have said in the past, the funding plan represents a major accomplishment for the state and puts CalSTRS on a much more sustainable path. However, the funding plan—which is three decades long—is still in the initial years of implementation.

Limitation in CalSTRS Rate Setting Authority Creates a Risk for the Funding Plan. If actuarial assumptions regarding the future materialize, the funding plan will bring the CalSTRS system to fully funded status in the mid‑2040s. However, future actuarial losses could create substantial risk to CalSTRS’ ability to achieve full funding by 2046. (“Actuarial losses” occur when experience deviates from what actuaries assume in a way that creates unfunded liabilities—for example, lower‑than‑assumed investment returns.) CalSTRS actuaries have reported that although the system likely will be better funded than it is today, there is about a 50 percent chance that the system will not be fully funded by 2046. This risk primarily stems from the limitations on the CalSTRS board’s rate setting authority. Because the board can only increase the state’s contribution rate by up to 0.5 percent of pay in any given year, actuarial losses can create future unfunded liabilities for the state that would not be addressed by 2046.

Example of Shortcoming in Limited Rate Setting Authority. There are many scenarios in which the limitations on CalSTRS’ rate setting authority constrain the system’s ability to compensate for actuarial losses. For example, CalSTRS estimates that an investment return of 5 percent (which is less than the assumed rate of 7 percent) would necessitate an ongoing increase in the state’s contribution rate by 1 percent of pay. (Based on current payroll estimates, a 1 percent of pay increase in the state’s rate is equivalent to about $350 million.) However, the board can only increase the state’s rate by 0.5 percent of pay each year. So, in the first year following the 5 percent return, the state’s rate would increase by 0.5 percent of pay and then an additional 0.5 percent pay in the next year. Figure 4 summarizes the effects on state contribution rates resulting from a few lower‑than‑assumed investment scenarios. The limitations on the board’s ability to increase the state’s contribution rate in response to actuarial losses under the funding plan mean that the state’s contribution rate might increase at a slower pace than would be the case if the board had full rate setting authority. Sustained actuarial losses over several years could create a risk that the system will not be fully funded by 2046.

Figure 4

Examples of CalSTRS Investment Loss Scenarios

|

CalSTRS’ Investment Return Assumption |

Hypothetical Investment Experience |

Actuarial Loss |

Implication for Increase in the State Rate |

Number of Years Needed to Fully Phase‑In Rate Change |

|

7% |

6% |

1% |

0.5% |

1 |

|

7 |

5 |

2 |

1.0 |

2 |

|

7 |

4 |

3 |

1.5 |

3 |

|

7 |

3 |

4 |

2.0 |

4 |

Use Proposition 2 to Keep the CalSTRS Funding Plan On Track. Proposition 2 presents the Legislature with a unique opportunity to determine how best to use funds that it is required to spend. We recommend the Legislature use Proposition 2 to increase state contributions to CalSTRS to address actuarial losses in future years (should they occur). In particular, in years when the board cannot increase rates sufficiently to address changes in the state’s unfunded liability, we recommend that the state direct Proposition 2 requirements to cover the difference. More specifically, Proposition 2 could be used to cover the cost of the difference between CalSTRS rates under law and what those rates would be if CalSTRS had full rate setting authority. This differs from the Governor’s approach in that future Proposition 2 payments to CalSTRS would be higher—or lower—depending on how much the system actually needed to reach full funding.

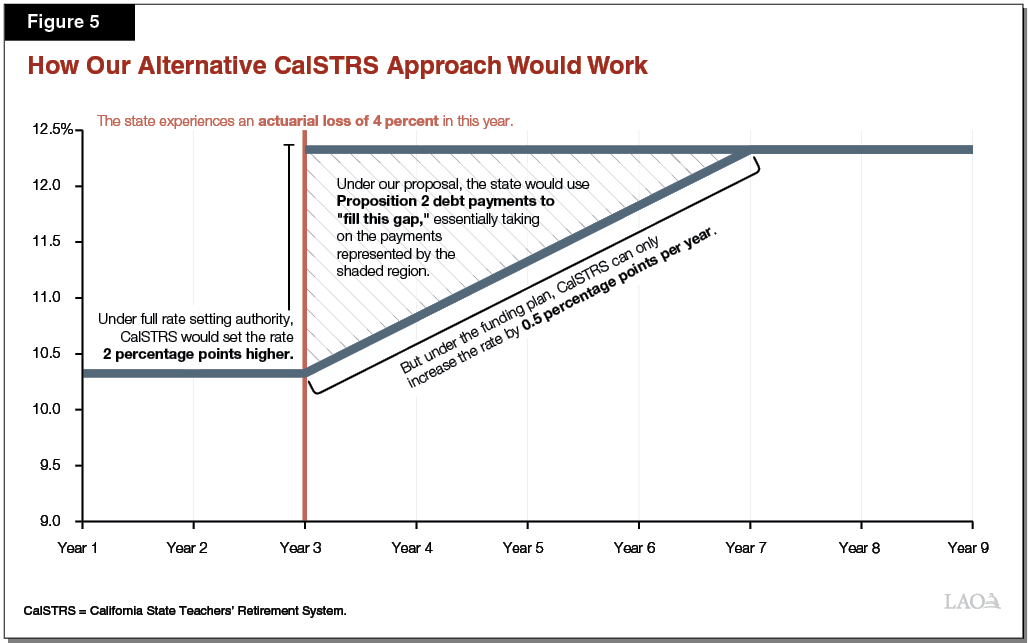

How This Approach Could Work. Figure 5 shows how our recommendation could work. For example, suppose in some year CalSTRS experiences an annual return of 3 percent—which is lower than the assumed rate of 7 percent. To make up for this actuarial loss, the board would need to increase the state’s rate by approximately 2 percent of pay, but under law could only raise the rate by 0.5 percent of pay each year over four years. In those intervening years, there would be a difference between the rate the state is paying and the rate the state would pay if the CalSTRS board had full rate setting authority. In dollar terms, this difference would very roughly equal $525 million in the first year, $350 million in the second year, and $175 million in the third year. Proposition 2 debt payments could be used to make up this difference. This means, under our recommendation, the state would contribute nearly $1 billion over the three years using Proposition 2 to make up for the loss.

Retiree Health

New Unfunded Retiree Health Liability Could Arise in the Future. The state and employees each contribute a percentage of pay to retiree health that roughly is equivalent to one‑half of the normal cost. This system creates two risks that might result in new unfunded liability in the future. First, normal cost for retiree health benefits—unlike pension benefits—grows over time at a rate that is unrelated to salary growth. This means that the percent of pay that constitutes half of the normal cost in one year might not be sufficient in future years. Second, new unfunded liabilities would emerge if experience deviates from the actuarial assumptions used to determine normal cost. For example, this would occur if health costs increase faster, retirees live longer, or investment returns are lower than actuaries had assumed when they calculated normal cost. These estimates also tend to be subject to a greater range of uncertainty compared to pension benefits, for example, because health care costs can grow unpredictably.

Some Risk That This New Unfunded Liability Would Mean the Retiree Health Plan Gets Off Track. New unfunded liabilities will occur in any year in which the full normal cost is not paid or in which actuarial losses occur. Unlike the CalPERS pension system with full rate setting authority or the CalSTRS system with limited rate setting authority, there is no automatic mechanism to increase contribution rates to retiree health benefits when new unfunded liabilities are created. This creates a risk that the retiree health benefit will not stay on track be fully funded by the mid‑2040s.

Use Proposition 2 to Keep the Retiree Health Prefunding Plan on Track. The state could use Proposition 2 to address future, new unfunded liabilities should they emerge for retiree health. For example, suppose in a particular year investment returns on prefunded assets fail to meet expectations. This would result in a new unfunded liability and would reduce the likelihood that the retiree health benefit is fully funded by the mid‑2040s. (If the system exceeded its investment target in a subsequent year the unfunded liability could be reduced or eliminated.) Using Proposition 2 to make up for these investment losses would keep the plan on track. The costs of addressing these new unfunded liabilities would be relatively low in the next few years—because there are so few assets invested that even significantly lower‑than‑assumed investment returns would result in a small dollar amount of unfunded liability. These costs will increase over time, however, as the state sets aside more prefunded assets.

Recommendation

In this report, we have discussed two different ways to use Proposition 2 debt payment requirements to keep the CalSTRS and retiree health funding plans on track. That said, the future amounts needed to accomplish this goal are still unknown. As such, to implement this approach, we recommend the Legislature adopt trailer bill language directing the administration to report, at the time of its January budget proposal each year, on a few different aspects of these funding plans. Specifically the report would include reporting language on:

- CalSTRS. In the case of CalSTRS, this report could include: (1) the annual difference between CalSTRS rates under law and what those rates would be if CalSTRS had full rate setting authority; (2) the annual cost, in dollar terms, of that difference; and (3) how much capacity Proposition 2 has to take on that difference.

- Retiree Health. For retiree health, this report could include: (1) the annual contribution requirement necessary to address any new unfunded liabilities resulting from actuarial losses over the amortization period assumed by actuaries in the most recent actuarial valuation; (2) the total amount, in dollar terms, of that new unfunded liability; and (3) how much capacity Proposition 2 has to address that total.

Given that CalSTRS payments are more likely to yield savings for the state over the next few decades and there is more uncertainty inherent in future health costs, we further recommend the Legislature use this trailer bill language to direct the administration to prioritize CalSTRS payments. In this case, capacity for retiree health would only occur after CalSTRS is addressed. This report would allow the Legislature to determine how to allocate Proposition 2 in future years to keep both plans on track while allowing more time to pass to assess how the plans are functioning.

Conclusion

In a report to the Legislature last year—The 2019‑20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities—we analyzed the Governor’s proposals to make several large supplemental pension payments. Those supplemental payments were part of the Governor’s budget resilience package, which aimed to improve the budget’s multiyear condition by paying down state debt. Those proposals departed from recent state practice to deposit more money into reserves as the primary method for putting the budget on better footing. We analyzed those proposals from that perspective, concluding that, if the state’s goal was to achieve more savings and improve the budget’s multiyear condition, making payments to CalPERS—not CalSTRS—would be best choice.

This report takes a different perspective. In this report, we consider the very long‑term benefits of supplemental payments to improve existing state plans to pay down state retirement liabilities. To that end, we recommend that the state use Proposition 2 payments to keep the state’s plans for CalSTRS and retiree health on track. While the administration’s multiyear plan for Proposition 2 also would direct additional funds toward CalSTRS—which we think makes sense—the proposed amounts are not connected to a specific actuarial need. We suggest the Legislature ask the administration to track progress on CalSTRS and retiree health more explicitly, and then use that information to direct additional payments to the systems based on those determined needs.

Further, our recommendations related to annual reporting would allow the state to monitor the progress of the state’s relatively new plans to address CalSTRS and retiree health liabilities. Over the next few years, it could mean the state directs more funding to CalSTRS and retiree health, but only to the extent that funding is actuarially needed. Over the next decade, this could help keep both plans on track and give Legislature more information about how the funding plans are working.