LAO Contact

March 11, 2020

Analysis of California's

Physician-Supervision Requirement

for Certified Nurse Midwives

Executive Summary

Women’s Health Care Providers Include Nurse Midwives. Three types of providers specialize in health care related to childbirth and women’s reproductive health. They are obstetricians and gynecologists (OB‑GYNs), nurse midwives, and licensed midwives. California has over 2,000 practicing OB‑GYNs, around 700 nurse midwives, and roughly 400 licensed midwives. OB‑GYNs and nurse midwives overwhelmingly practice in hospitals, while licensed midwives primarily practice outside of hospital settings, such as freestanding birth centers. Nurse midwives and licensed midwives are authorized to be the exclusive attendant in cases of normal childbirth but are not authorized to be the exclusive attendant of high‑risk births, such as those involving twins and those delivered by mechanical or surgical means.

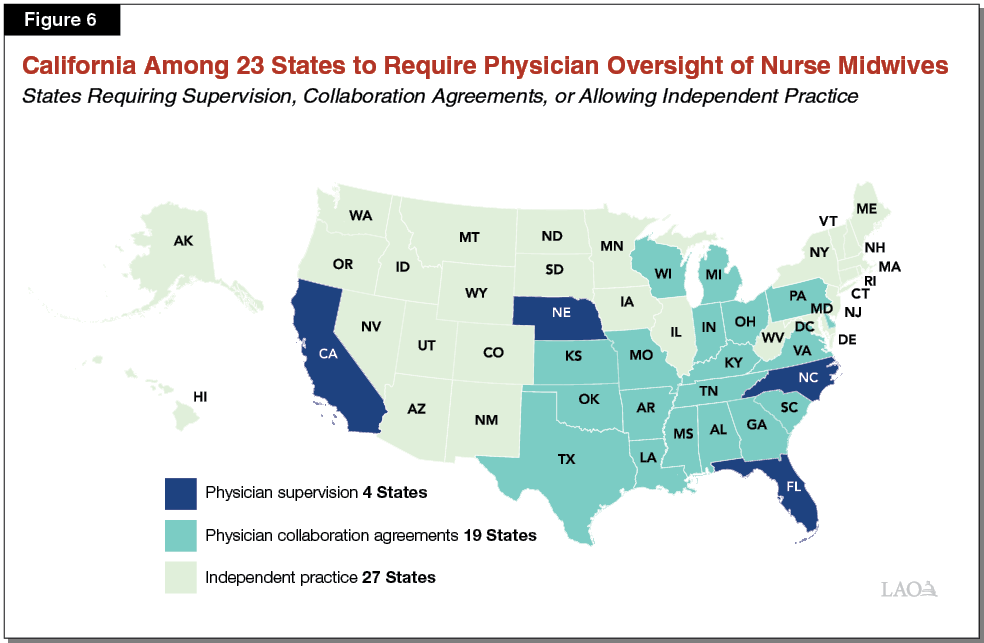

California Is Among 23 States to Require Physician Oversight of Nurse Midwives. Under California state law, nurse midwives may only practice and deliver health care services under the supervision of a licensed physician. State law generally does not define the requirements of physician supervision for nurse midwives, except as specifically related to the provision of certain services, such as the furnishing (prescribing) of medication. (State law also specifies that physician supervision does not require the physical presence of the physician.) While only four states (including California) require physician supervision of nurse midwives, an additional 19 states have similar requirements that nurse midwives maintain “collaboration agreements” with physicians in order to practice.

Report Analyzes California’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement for Nurse Midwives. California’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives is intended to improve the safety and quality of women’s health care. This report analyzes whether the requirement is effective at achieving this purpose and the trade‑offs the requirement could create, such as impeding access or increasing the cost of care. The findings of this report only are intended to apply to nurse midwives, not licensed midwives, who currently are not subject to a physician‑supervision requirement.

Physician‑Supervision Requirement Unlikely to Significantly Improve Safety and Quality. Following our review of academic literature, we do not find evidence that the safety and quality of maternal and infant health care by nurse midwives is inferior to that of physicians in cases of low‑risk pregnancies and births. Moreover, states with physician‑supervision or collaboration‑agreement requirements do not have superior maternal and infant health outcomes than states without such requirements. At the state level, because California’s requirement does not clearly define the responsibilities of supervision, the state’s requirement is unlikely to be more effective than other states’ similar requirements. Therefore, we find that California’s supervision requirement for nurse midwives is unlikely to improve safety and quality for low‑risk pregnancies and births.

Physician‑Supervision Requirement Potentially Is a Factor Contributing to Limited Access and Raising Costs for Nurse‑Midwife Services. We find some evidence that access to nurse‑midwife services specifically, and women’s health care services generally, might be limited in California. For example, the recent high growth in earnings for nurse midwives suggests that demand for their services may exceed supply. We also find evidence of geographic disparities across the state in access to care by OB‑GYNs. We agree with the Federal Trade Commission’s finding that physician‑supervision requirements likely impede access and raise costs by giving physicians control over nurse midwives’ ability to independently deliver services. Moreover, on the national level, research shows that states without occupational restrictions on nurse midwives, such as physician oversight, tend to have greater access to nurse‑midwife services.

Removing Physician‑Supervision Requirement Could Increase Access and Promote Cost‑Effectiveness. Removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement could increase access to nurse‑midwife services, including in the rural and inland areas of the state that today have relatively more limited access to women’s health care services. In addition, we find that removing the requirement could improve the cost‑effectiveness of women’s health care services by increasing utilization of a less costly but capable provider and potentially lowering the medically unnecessary use of certain costly procedures, such as cesareans.

Recommend the Legislature Consider Removing the Physician‑Supervision Requirement, and Add Other Safeguards. We find that the state’s physician‑supervision requirement is unlikely to be effective in achieving its objective of improving safety and quality. Moreover, we find that the requirement likely introduces trade‑offs in terms of decreasing access and raising the cost of care. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature consider removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives, while adding other alternative safeguards to ensure safety and quality. We believe these other safeguards could be more cost‑effective than the state’s physician‑supervision requirement at ensuring safety and quality. They could be imposed as conditions of licensure or as conditions to practice without supervision. Such safeguards could include requiring nurse midwives to:

- Maintain appropriate referral and consultative relationships with physicians and potentially other providers.

- Practice as a part of a health system (generally defined as a hospital, provider group, or health plan).

- Practice in a licensed or accredited facility.

- Maintain medical malpractice insurance.

- Meet minimal clinical experience standards (such as a minimum number of years of practice) in order to practice without oversight.

Introduction

In an effort to ensure safety and quality, California state law places occupational licensing restrictions on who may provide childbirth and reproductive‑related health care services to women. (Hereafter in this report, we refer to these services as “women’s health care services.”) Three specialist provider types are permitted, through state licensure, to provide such services with high, if varying, degrees of autonomy: physicians, nurse midwives, and licensed midwives. Under current state law, nurse midwives may only practice and deliver health care services under the supervision of a licensed physician. In contrast to California, most other states do not have a physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives, and a majority of other states do not even have the requirement for nurse midwives to maintain collaboration agreements with a physician.

At the request of a member of the Legislature, this report analyzes the impact removing California’s current physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives would have on health care outcomes and access to care for mothers and their infant. In effect, we have been tasked with analyzing whether a specific occupational licensing requirement for nurse midwives—in this case, the physician‑supervision requirement—is meeting its intended safety and quality objectives without significantly decreasing access to health care services (or increasing cost). While providing primary care services is within the scope of practice of nurse midwives, the focus of this report—and the research we cite—is on the care provided to women and their infants related to pregnancy and childbirth. This focus reflects the fact that such care is a primary focus of nurse‑midwives’ services and is the most complex and risky care that they generally provide.

While we recognize that changes to other occupational licensing requirements on nurse midwives—such as their scope of practice—may bring certain benefits, we focus in this report on the state’s physician‑supervision requirement since its effects are likely more pronounced and better studied than other occupational licensing requirements. The findings of this report are not expressly intended to extend to licensed midwives, in large part due to the fact that licensed midwives can already practice without physician supervision under California state law.

Layout of the Report

This report contains three main sections. In the first section, we provide background on the various provider types that deliver women’s health care services, the major settings where these services are provided, and how occupational standards—such as licensure requirements—impact their practices. The second section of this report contains our analysis. It opens by laying out the evaluation framework by which we assess the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives. Next, we summarize national research findings related to the safety, quality, and relative cost‑effectiveness of care by nurse midwives, as well as how occupational restrictions affect access to their services. We then assess the likely impact of California’s physician‑supervision requirement on—and how removing it may affect—the safety, quality, accessibility, and relative cost‑effectiveness of nurse‑midwife services. The last section of this report provides our concluding assessment and includes our recommendations. At the end of this report, we include a selected references section that displays the major academic articles and other reports that we relied upon in our analysis.

Background

State Law and Professional Societies Set Requirements for Who May Provide Health Care Services

State Licenses Health Care Providers. Through the licensing of providers, California state law places restrictions on who may provide certain kinds of health care services. The state issues distinct licenses for different types of health care providers, including, for example, physicians and surgeons, dentists, and nurses. An individual who obtains a given license is permitted under law to provide the services authorized under the license, while an individual without that license is prohibited from providing such services.

State Sets Licensure Standards. State rules establish minimum educational, clinical experience, and other standards in order for individuals to become licensed health care providers. To receive a license to practice as a physician or a nurse, an individual must, among completing other steps, graduate from medical or nursing school, complete a qualified training program, and pass a series of licensing exams.

Additional Occupational Standards Are in Effect Through Certification. Health care providers—prospective or practicing—who wish to perform in certain specialties regularly seek certification from nongovernmental agencies with the intent of demonstrating their proficiency in those specialties or procedures. As with licensure, to obtain certification, providers typically must meet minimum education and/or work experience requirements and pass formal assessments such as a qualification exam. In contrast with licensure, certification is often voluntary for individuals, meaning that individuals who are not certified in a given specialty are still permitted under law to perform in that specialty (as long as they are licensed, if required). However, health care systems, such as hospitals and health insurers, regularly require—for a broad range of specialties—their providers to be certified in order to practice.

Providers May Perform Services Within Their Scopes of Practice. Scope‑of‑practice rules establish the range of services and procedures that a health care provider may perform under their professional license, certification, or otherwise determined competencies. Some scope‑of‑practice rules are established in state law while others are self‑determined by individual health care systems and/or professional societies—such as the American Board of Family Medicine. The following bullets give a high‑level summary of how California’s scope‑of‑practice rules pertain to physicians, nurses, and advanced practice nurses.

- Physicians. In California state law, physicians’ scope to practice medicine and surgery is unlimited. Accordingly, state law broadly authorizes physicians to diagnose mental and physical health conditions, prescribe and administer medication, and perform surgery. In practice, however, physicians tend to practice within the scope of their particular specialties. Physicians typically receive national certification to practice within the various specialties.

- Registered Nurses. The scope of practice for registered nurses includes the provision of basic health care, such as observing the signs and symptoms of illness (but not its diagnosis), delivering immunizations, and drawing blood. Registered nurses generally may administer medications and other therapies only as ordered by a physician or by another authorized provider.

- Advanced Practice Nurses. Advanced practice nurses are registered nurses who have completed graduate‑level (masters‑ or doctoral‑level) nursing education. (In contrast, registered nurses generally will have completed bachelor‑ or associates‑level nursing education.) Nurse practitioners are the most numerous type of advanced practice nurses. Given their advanced education, advanced practice nurses have a more expansive scope of practice compared to registered nurses. For example, advanced practice nurses may diagnose patients, order tests, and “furnish” (broadly similar to prescribe) medications. Unlike physicians, however, advanced practice nurses’ scope of practice are, in some cases, limited within state law. In addition, for certain services, California state law requires advanced practice nurses to practice in accordance with standardized procedures, as developed in collaboration with physicians and the health systems in which they work.

State Law Establishes Physician‑Supervision Requirements for Certain Types of Advanced Practice Nurses. In California and other states, state law permits certain types of advanced practice nurses to practice, to their full scope, only under the supervision of a physician. By “full scope of practice,” we mean delivering advanced practice nursing services, as opposed to the services delivered by a registered nurse as ordered by a physician or other provider. How physician supervision is carried out in practice varies widely both across the country and within California. It generally involves (1) collaboration in the development and approval of standardized procedures, which advanced practice nurses generally are expected to follow in certain circumstances (such as prescribing medications), and (2) availability for consultation. In many cases, physician supervision additionally can involve “chart reviews” and/or other types of consultation whereby the supervising physician reviews and advises upon advanced practice nurses’ patient care decisions during and/or after patient treatment. Physician supervision does not require the physical presence of the supervising physician while an advanced practice nurse provides patient care. Given the absence of a physical‑presence requirement, in California and other states, advanced practice nurses may practice far away from their physician supervisors.

Women’s Health Care Providers

Several Provider Types Specialize in Women’s Health Care. While a variety of provider types assist in childbirth and women’s health care services more broadly, several provider types specialize in this domain of care. The major specialist provider types include:

- Obstetrician‑Gynecologists (OB‑GYNs). OB‑GYNs are physicians who are certified to practice obstetrics and gynecology, which are the surgical and medical specialties related to pregnancy, childbirth, and women’s reproductive health.

- Nurse Midwives. Nurse midwives are a type of advanced practice nurse who are certified to practice nurse midwifery—health care related to women’s reproductive health, pregnancy, and childbirth. Nurse midwives must hold a graduate degree in nurse midwifery. They provide primary care and assist, often without the physical presence of a physician, in childbirth provided that the pregnancy is low risk and proceeds without major complications. We discuss in detail the various occupational licensing restrictions that apply to nurse midwives in California in the next section of this report.

- Licensed Midwives. Licensed midwives are trained, non‑nurse midwives who provide health care, including assistance during pregnancy and childbirth, to women and their infants. Minimum licensing requirements for licensed midwives include holding a high school diploma and completion of a qualified midwifery educational program that includes clinical training in pre‑ and postpartum care and labor management.

Figure 1 compares the major educational and training differences between OB‑GYNs and nurse midwives. In addition to the above‑noted specialist providers, family practice physicians also regularly provide women’s health care services, with a small portion (according to national statistics) regularly attending childbirths. Family practice physicians are trained to deliver a broad range of primary care services, including, but not limited to, women’s health care services.

Figure 1

Major Educational, Training, and Credential Differences Between Nurse Midwives and OB‑GYNs

|

Nurse Midwives |

OB‑GYNs |

||

|

Education Requirements |

|||

|

Bachelor’s degree |

Bachelor of Nursing or completion of similar coursework |

Bachelor’s degree with medically relevant coursework |

|

|

Master’s degree |

Master’s of Nurse‑Midwifery |

— |

|

|

Doctoral degree |

— |

Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine |

|

|

Typical total years of post‑secondary education |

6 |

12a |

|

|

Clinical Training Experienceb |

|||

|

Hours of general nursing/medical education clinical training experience |

800 |

4,000 |

|

|

Hours of graduate‑level nurse‑midwifery or OB‑GYN clinical training experience |

1,000 |

14,000c |

|

|

Total hours of clinical training experience |

1,800 |

18,000 |

|

|

Licensure and Certification |

|||

|

Licensing requirement |

Licensed as registered nurses by the California Board of Registered Nurses |

Licensed as physicians by the California Board of Medicine or California Board of Osteopathic Medicine |

|

|

Specialty certification requirement |

Certified as nurse midwives by the American Midwifery Certification Board |

Certified as OB‑GYNs by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology |

|

|

aIncludes years in residency. bLAO estimates. cA significant portion of these residency training hours relate to the diagnosis and treatment of conditions outside of the scope of practice of nurse midwives. For example, this training includes advanced procedures such as cesareans and hysterectomies and advanced treatments for illnesses such as for cancer. OB‑GYN = obstetrician and gynecologist. |

|||

Nurse Midwives Comprise an Appreciable Share of the Women’s Health Care Workforce in California… There are over 2,000 OB‑GYNs in California, compared to more than 700 nurse midwives and almost 400 licensed midwives. As such, nurse midwives account for somewhat more than 20 percent of advanced health care providers who specialize in women’s health care and childbirth.

…But Are Recorded as Attending a Significantly Smaller Share of the State’s Births. In 2017, nurse midwives were recorded as attending almost 50,000 births in the state, or somewhat more than 10 percent of the 470,000 births in the state that year. Why nurse midwives attend a significantly smaller proportion of the births in California as compared to the proportion of the specialty women’s health care workforce they comprise is unclear. However, one reason likely is that births attended by nurse midwives are not always recorded as such (for example, they are recorded as having been attended by a physician).

Women’s Health Care Settings

Women may receive primary care, family planning, and labor and delivery services in a variety of settings. The following bullets briefly describe four settings that specialize in women’s health care and detail how physician and nurse‑midwife services are utilized in similar and different ways across the settings:.

- Hospitals. The vast majority of births, whether attended by physicians or nurse midwives, occur at the hospital. In California, essentially 100 percent of physician‑attended births and 98 percent of nurse midwife‑attended births—together totaling about 460,000 of the state’s births in 2017—occur at the hospital. Within hospitals, labor and delivery care usually is provided within a standard obstetric unit or, less commonly, within a birth center located on the same campus or in the same building as the hospital. Obstetric units typically are physician‑led, whereas hospital‑based birth centers typically are led by nurse midwives or collaborative nurse midwife and physician teams. Primary care and family planning services, whether delivered by physicians or nurse midwives, commonly occur outside of the hospital.

- Freestanding Birth Centers. Freestanding birth centers are outpatient facilities where women can give birth in a health care setting other than a hospital. Freestanding birth centers typically are staffed by nurse midwives and licensed midwives and generally are intended for expecting mothers who prefer fewer medical interventions be used during delivery. Physicians generally do not attend births within this setting. Around 1,400 births occurred in freestanding birth centers in 2017, or less than 1 percent of the state’s births that year.

- Home Settings. Some women—somewhat more than 2,000 women in 2017—opt to deliver outside of a health care setting and instead do so at home. Home births are predominantly attended by licensed midwives (86 percent) or by nurse midwives (12 percent). Physicians attend the remaining 2 percent.

- Women’s Health Clinics. Women’s health clinics offer a range of primary care and gynecological outpatient services tailored to women and their reproductive health. Births do not take place in women’s health clinics.

California’s Rules Governing the Practice of Nurse Midwives

This section describes the major practice rules placed on nurse midwives. Figure 2 summarizes the major practice differences between nurse midwives and OB‑GYNs in terms of where they typically practice and how they can practice.

Figure 2

Major Practice Differences Between Nurse Midwives and OB‑GYNs

|

Nurse Midwives |

OB‑GYNs |

|

|

Common Practice Settings |

||

|

Hospital‑based deliveries |

||

|

Freestanding birth center deliveries |

||

|

Home‑birth deliveries |

||

|

Clinic‑based primary care |

||

|

Practice Restrictions and Authority |

||

|

Physician supervision required |

||

|

Scope of practice limited in state law |

||

|

Practice Authority to: |

||

|

Provide primary care and family planning services |

||

|

Deliver prenatal, postpartum, and newborn care |

||

|

Furnish (prescribe) medications |

||

|

Attend low‑risk and normal childbirths |

||

|

Attend births experiencing complicationsa |

||

|

Deliver twins |

||

|

Deliver with the use of medical instruments |

||

|

Perform cesarean sections |

||

|

Perform gynecological surgeries |

||

|

Provide gynecological cancer treatment |

||

|

aWhen a low‑risk birth experiences complications, nurse midwives are required by state law to immediately refer and transfer the birth to a physician’s care. OB‑GYN = obstetrician and gynecologist. |

||

Nurse Midwives May Only Practice Under the Supervision of a Physician. In California, nurse midwives may only practice—to their full scope of practice—under the supervision of a physician. For nurse midwives, a supervisor must be a physician with a current practice or training in obstetrics. State law does not further define the requirements of physician supervision for nurse midwives, except as specifically related to the furnishing (prescribing) of medication, the repair of minor lacerations, and the making of small cuts to prevent lacerations (episiotomies). There is no state requirement that nurse midwives practice within the same geographic vicinity as their physician supervisor. As such, the physical presence of a nurse midwife’s supervisor is not required under state law during deliveries or other services provided by nurse midwives.

Nurse Midwives May Furnish Medications in Accordance With Standardized Procedures. Nurse midwives have the authority under state law to furnish medications. They must do so, however, in accordance with standardized procedures that are developed and approved in collaboration with their supervising physicians. These standardized procedures establish which medications a nurse midwife may furnish, under what circumstances they may do so, and how their competence and the standardized procedures will be periodically reviewed. State law further limits the total number of medication‑furnishing advanced practice nurses that an individual physician may supervise at a given time. This limit is one supervising physician to four advanced practice nurses who furnish medications. In addition, state law requires that, for nurse midwives to furnish medications, their supervising physician must be available via telephone at the time of a patient’s visit.

State Scope‑of‑Practice Rules Limit Nurse Midwives to Attending “Normal Childbirths.” Under California law, nurse midwives are authorized to be the exclusive attendant only for normal childbirths. Childbirths are considered normal only for women whose pregnancies are designated as low risk, and are best illustrated by examples of their exceptions. Accordingly, for example, high‑risk pregnancies include the birthing of twins or significantly pre‑ or post‑term deliveries. Additionally, nurse midwives may not deliver children by mechanical means, such as with the use of forceps or a vacuum.

Immediate Referral to a Physician Is Required When Childbirth Complications Arise. Nurse midwives are required to immediately refer women experiencing complications during childbirth to a physician. Examples of complications include labor that is not progressing at a safe speed, or for which the use of medical instruments (such as forceps or a vacuum) is necessary. Similarly, women in labor requiring an emergency cesarean section must be referred to a physician. Childbirths that feature relatively minor lacerations, or for which minor surgical cuts are made to prevent lacerations, are considered normal and are, therefore, within the scope of practice of nurse midwives. For hospital births, referral involves a simple handoff from the attendant nurse midwife to an on‑call physician. For freestanding birth center and home births, referral typically will entail transportation to a hospital.

Analysis

In this section, we analyze the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives. Specifically, we assess whether this requirement is effective in ensuring and improving the safety and quality of childbirth without unreasonably impeding access or raising costs. First, we lay out the evaluation framework we use to analyze this (and potentially other) occupational restrictions. Second, we summarize national research findings on (1) the safety and quality of nurse‑midwife services across various practice settings (including across different occupational licensing requirements), (2) whether access to women’s health care is impaired by restrictions on nurse midwives’ independent practice, and (3) whether such restrictions raise the costs of women’s health care. Third, we evaluate the effect of California’s physician‑supervision law from a California‑specific perspective. Finally, we present our assessment of how removal of the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives could impact access to relatively safe, high‑quality, and cost‑effective women’s health care services.

Evaluation Framework

This section describes the evaluation framework that we utilize in this report to assess the benefits and trade‑offs of the physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives.

Occupational Restrictions Can Be Appropriate Insofar as They Achieve a Public Purpose... Occupational restrictions—such as licensure, scope‑of‑practice regulations, and supervision requirements—can be appropriate insofar as they achieve a public purpose without imposing unreasonable trade‑offs. In general, occupational restrictions can be an appropriate means to implement the broad public purpose of ensuring and improving the safety and/or quality of a given service. In particular, such restrictions may be appropriate when (1) consumers would have difficulty observing and/or predicting the safety or quality of a given service and (2) there is risk of serious and irrevocable harm when a service is performed poorly.

…But There Are Trade‑Offs to Consider. As previously noted, occupational restrictions bring trade‑offs. Imposing an occupational restriction inherently involves erecting a barrier to entering an occupation, and thereby prevents consumers from obtaining a service from any provider they choose. Doing so can impede competition among service providers and, as a result, potentially raise prices and reduce access to those services. Moreover, occupational restrictions can have the potential to impair the quality of services when they prevent competent but uncredentialed providers from entering a market to compete on the quality of their services. Given these trade‑offs, occupational restrictions should be employed by policymakers with scrutiny and care, and be reassessed as evidence arises regarding impacts on safety, quality, access, and cost. When feasible, occupational restrictions should be judged in comparison to other policies that could achieve the same purpose. Figure 3 summarizes our evaluation framework for assessing occupational restrictions in health care broadly.

Figure 3

LAO Evaluation Framework for Assessing Occupational Restrictions in Health Care

|

Occupational restrictions may be appropriate when: |

|

|

Consumers would have difficulty observing and/or predicting the quality or safety of a given health care service. |

|

|

There is a risk of serious and irrevocable harm when a health care service is performed poorly. |

|

|

Trade‑offs to consider in establishing an occupational restriction: |

|

|

The impact on access to health care services. |

|

|

The impact on the cost of health care services. |

|

|

Potential to impair rather than improve the quality of health care services. |

|

|

LAO = Legislative Analyst’s Office. |

|

Occupational Restrictions for Nurse Midwives Should Allow and Facilitate Access to Safe, High‑Quality, and Cost‑Effective Care. As discussed in the background, California state law requires nurse midwives to practice under the supervision of a physician and places certain other scope‑of‑practice restrictions on nurse midwives. Consistent with our evaluation framework for occupational restrictions for health care services generally, we view the state’s restrictions on nurse‑midwife practice as appropriate insofar as they allow and facilitate access to relatively safe, high‑quality, and cost‑effective care. Ease of access—having sufficient numbers of available health care providers throughout the state—should be considered in conjunction with the effects on safety and quality. Figure 4 defines the key terms of our framework.

Figure 4

Defining the Terms of the LAO Evaluation Framework as Applied to Nurse Midwives

|

Access: Ability of individuals to successfully obtain pregnancy, labor and delivery, and reproductive health care in a timely manner from an appropriate and preferred provider. |

|

Safety: Protection from risk and injury related to pregnancy, labor and delivery, and reproductive health. |

|

Quality: A summary measure combining (1) patient satisfaction with pregnancy, labor and delivery, and reproductive health care and (2) the consistency of such care with clinical best practice guidelines. |

|

Cost‑Effective: Effectiveness or value in terms of safety, quality, and accessibility of health care in relation to the costs of such care. |

|

LAO = Legislative Analyst’s Office. |

This Analysis Examines California’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement. Applying the evaluation framework outlined above, this analysis specifically examines the effectiveness of California’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives by asking the following questions:

- Does the Requirement Improve the Safety and Quality of Maternal and Infant Health Care? As with other occupational restrictions, the fundamental purpose of California’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives is to ensure and improve the safety and quality of mothers’ and infants’ health care. To judge safety and quality, we examine the growing body of research on the question of whether (1) care by a physician results in superior maternal and infant health outcomes compared to care by a nurse midwife and (2) whether states with less strict occupational restrictions on nurse midwives experience worse health outcomes for mothers and infants compared to states with stricter restrictions.

- Does the Requirement Unreasonably Impede Access to Care? As previously noted, occupational restrictions can impede access to services governed by the restrictions. In this analysis, we examine whether California’s physician‑supervision requirement unreasonably impedes access to women and infants’ health care services.

- Is the Requirement Relatively Cost‑Effective Compared to Alternative Approaches to Ensuring Safety and Quality? Occupational restrictions are one of a variety of policy approaches for ensuring and improving the safety and quality of a given service. As such, we evaluate whether California’s physician‑supervision requirement appears relatively cost‑effective in improving safety and quality as compared to alternative approaches.

Figure 5 summarizes our evaluation framework for assessing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives.

Figure 5

LAO Evaluation Framework for Assessing the State’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement for Nurse Midwives

|

Requiring physician supervision of nurse midwives can be appropriate if theory and evidence show: |

|

|

The safety and/or quality of health care provided by nurse midwives appears deficient compared to that of physicians. |

|

|

The requirement improves safety and/or quality of women’s health care. |

|

|

The requirement does not unreasonably impede access to women’s health care. |

|

|

The requirement appears relatively cost‑effective compared to alternative approaches to ensuring safety and quality. |

|

|

LAO = Legislative Analyst’s Office. |

|

Assessment of National Research Findings

This section provides our assessment of national research on how occupational restrictions related to nurse‑midwife practice affect (1) the safety and quality of women’s health care, (2) access to such care, and (3) the cost‑effectiveness of such care.

State Laws Vary for Nurse Midwives

Nurse Midwives’ Independence Varies. Nurse midwives are allowed to practice and are active in all 50 states. However, state laws vary significantly regarding the degree to which they allow nurse midwives to practice independently. States with high degrees of “independent practice” for nurse midwives do not require physician supervision and generally impose fewer scope‑of‑practice restrictions on nurse midwives. Examples of such scope‑of‑practice restrictions include limitations on nurse midwives’ authority to furnish medication and to practice at a faraway geographic distance from their supervising physician.

About Half of States Require Physician Oversight. California is among four states that require physician supervision of nurse midwives. Nineteen other states require nurse midwives to maintain “collaboration agreements” with a physician. Collaboration‑agreement requirements are broadly similar to physician‑supervision requirements. They generally entail written agreements between nurse midwives and their collaborating physicians that outline the parameters under which a nurse midwife may practice. The remaining 27 states allow nurse midwives to practice independently, that is, without a physician‑supervision or collaboration‑agreement requirement. Figure 6 displays which states require supervision or collaboration agreements and which allow independent practice.

Care Provided by Nurse Midwives Is Comparable to Physician Care

Hospital‑Based Labor and Delivery Care by Nurse Midwives Compares Favorably to Care Provided by Physicians. Academic researchers have extensively explored how hospital‑based labor and delivery care by nurse midwives for women with low‑risk pregnancies compares to such care by OB‑GYNs and other physicians. (As previously noted, in California, 98 percent of nurse midwife‑attended births occur at the hospital.) This body of research demonstrates that the care provided by nurse midwives during labor and delivery in hospitals is comparable, or in some cases, potentially superior to the care provided by physicians. For example, infant mortality rates and other infant outcomes are comparable for nurse midwives and physicians. Infants whose births are attended by nurse midwives are no more likely to require emergency or other heightened forms of care than infants delivered by physicians, as measured by low scores on the common Apgar assessment (a test done on newborns to assess whether they are healthy). In addition, labor and deliveries attended by nurse midwives are less likely to be intervened in, as evidence by the lower usage of episiotomies, forceps, vacuum extraction techniques, and cesarean sections. Such interventions, while critical in cases of medical necessity, come with risks and therefore are recommended to be employed only as needed. Figure 7 summarizes our assessment of academic research findings as they pertain to the care provided by nurse midwives and physicians, mostly in hospital settings.

Figure 7

Nurse‑Midwife Care Is at Least Comparable to Care by Physicians for Women With Low‑Risk Pregnancies

|

Selected Outcomesa |

Better Outcomes Associated |

Evidence Gradeb |

|

Labor Process Outcomes Related to: |

||

|

Labor induction utilizationc |

Yes |

High |

|

Labor augmentation utilizationc |

Yes |

Moderate |

|

Overall length of labor and delivery |

No Differenced |

Suggestive |

|

Birth Process Outcomes Related to: |

||

|

Cesarean section utilizationc |

Yes |

High |

|

Episiotomy utilizationc |

Yes |

High |

|

Forceps/vacuum extraction utilizationc |

Yes |

Moderate |

|

Infant Health Outcomes Related to: |

||

|

Apgar scores |

No Differenced |

High |

|

Mortality rates |

No Differenced |

Suggestive |

|

Breastfeeding rate |

Yes |

Suggestive |

|

Maternal Health Outcomes Related to: |

||

|

Perineal lacerations |

Yes |

Moderate |

|

Mortality rates |

No Differenced |

Suggestive |

|

Postpartum hemorrhage |

No Differenced |

Suggestive |

|

aWhile the table includes only selected outcomes, the findings generalize to many other outcomes studied in the literature, which generally shows nurse‑midwife care to be at least comparable to care by a physician. We note that these studies primarily compare nurse‑midwife and physician care in hospital settings. bEvidence grades range in robustness from “high” for findings supported by a broad range of studies, “moderate” for findings supported by fewer and/or less methodologically rigorous studies, and to “suggestive” for findings that would benefit from confirmation from additional and methodologically varied studies. cCare guideline is to reduce when medically unnecessary. dLiterature generally does not show consistent significant differences in outcomes between the two provider types. |

||

Greater Variation and Uncertainty in Safety and Quality of Care by Nurse Midwives Outside of the Hospital. As discussed above, the research literature amply demonstrates the quality of labor and delivery care provided by nurse midwives in hospital settings—by far the most common setting. However, in our review of the research literature, we found less conclusive and more mixed evidence of the safety and quality of care in other settings where nurse midwives practice commonly. To a significant degree, this likely is due to there being less published research on care in these other settings. In the following bullets, we provide our assessment of the research on safety and quality in the major nonhospital settings in which nurse midwives practice.

- Labor and Delivery Care in Freestanding Birth Centers. A number of studies compare labor and delivery outcomes (in terms of safety and quality) between hospital births and freestanding birth centers, the latter of which often are staffed by nurse midwives. Some of these studies show superior outcomes in freestanding birth centers while others show the opposite. In our assessment, the safety and quality of care provided at freestanding birth centers appears roughly comparable to, if not slightly more risky than, care in hospitals. At the very least, given the varied findings in the studies we reviewed, we find there is relatively greater uncertainty related to the safety and quality of care in freestanding birth centers compared to hospital settings. Importantly, the studies that examine births in freestanding birth centers do not necessarily examine which type of provider attends the planned birth. Therefore, the studies do not show the impact of the provider type on safety and quality within this setting.

- Home Birth Care. In our review, studies on the safety and quality of planned home births varied significantly in their results—with some showing better outcomes for hospital births and some showing better outcomes for planned home births. In our assessment, on balance, planned home births appear to come with some elevated risk compared to other birth settings. Planned home births usually are attended by midwives, with the majority in California being attended by licensed midwives rather than nurse midwives. As with births in freestanding birth centers, the studies that examine home births do not necessarily examine which type of provider attends the planned birth. Therefore, the studies do not show the impact of the provider type on safety and quality within this setting.

- Women’s Primary Care Services. We reviewed a small selection of studies that specifically compares the safety and quality of primary care provided by nurse midwives versus physicians, including care before and after childbirth. As a whole, these studies do not find major differences in the safety and quality of care provided by nurse midwives and physicians. That said, given the small number of studies that we found that evaluated this aspect of the care provided by nurse midwives, we find there to be somewhat greater uncertainty around the comparability of physician and nurse‑midwife care for women’s primary care services.

States With Less Stringent Restrictions on Nurse Midwives’ Independent Practice Do Not Experience Worse Birth Outcomes. Several research studies explore whether states with less stringent occupational restrictions on nurse midwives experience worse birth outcomes. One study we reviewed specifically examines whether physician‑supervision or collaboration‑agreement requirements are associated with improved birth outcomes. Other studies look at occupational restrictions broadly rather than strictly focusing on whether a state allows nurse midwives to practice without physician supervision or collaboration agreements. Nevertheless, for these latter studies, physician‑supervision requirements are an important component used by researchers to ascertain the extent by which occupational restrictions affect nurse midwives’ ability to practice independently. This research generally finds no association between relatively more stringent occupational restrictions on nurse midwives and improved maternal and infant health outcomes. Because these studies examine basic associations (while controlling for certain relevant differences among states, such as demographics and average educational attainment), they do not establish a firm, causal relationship showing whether or not occupational restrictions on nurse midwives improve health outcomes.

Occupational Restrictions on Nurse Midwives Are Associated With Less Access to Their Services

Researchers have examined whether states with fewer occupational restrictions on nurse midwives have a proportionately higher number of nurse midwives and therefore, greater access to nurse‑midwife services for those desiring them. This research finds that in states with fewer occupational restrictions on nurse midwives—including, but not necessarily limited to, physician‑supervision or collaboration‑agreement requirements—there are proportionately more nurse midwives practicing and more births are attended by nurse midwives. For example, one study of 12 million births nationwide showed that in states that do not require physician supervision or collaboration agreements, the proportion of all births attended by nurse midwives is nearly 60 percent higher than states with such requirements. Similarly, states with generally less stringent occupational restrictions tend to have higher numbers of nurse midwives on a per‑population basis and higher utilization of nurse‑midwife services. We note that since these studies are observational as opposed to experimental in nature, whether fewer occupational restrictions actually cause an increase in the number of practicing nurse midwives, or if other factors explain the identified relationship, is uncertain.

Nurse Midwives Likely Provide Relatively Cost‑Effective Care

Several studies directly compare the costs of care provided by nurse midwives and OB‑GYNs. There also are strong practical reasons to expect that care by nurse midwives is less costly compared to OB‑GYNs. This section lays out the main reasons. We note that, provided the effectiveness (safety and quality) of care remains constant or improves, a reduction in costs necessarily increases its cost‑effectiveness.

Nurse Midwives Employ Fewer Costly Labor and Delivery Interventions Than Physicians. Among only low‑risk pregnancies, births attended by nurse midwives tend to have lower rates of intervention in the labor and delivery process compared to births attended by physicians. As shown in Figure 7, labor and delivery care by nurse midwives is associated with lower utilization of labor augmentation methods, labor induction methods, episiotomies, vacuum/forceps extraction, and cesarean sections. Such interventions, when not medically necessary, can raise the cost of labor and delivery, either because there is an extra charge for the specific intervention or because the intervention—particularly in the case of cesareans—results in a longer length of stay at the hospital. For example, because the intervention itself is costly and is associated with longer lengths of stay at the hospital, cesarean deliveries are generally between 60 percent and 90 percent more costly than vaginal deliveries. Overall, given the evidence that nurse midwives tend to minimize the unnecessary use of labor and delivery interventions, utilizing nurse midwives to a greater extent could increase the cost‑effectiveness of labor and delivery care.

Nurse Midwives’ Salaries Are Generally Lower Than OB‑GYNs’. In California, average annual salaries for nurse midwives are $135,000, whereas OB‑GYNs earn $225,000 annually. Thus, nurse midwives earn about 60 percent of what OB‑GYNs earn. One likely reason that nurse midwives’ salaries are lower is the significantly lower cost of their training. As shown in Figure 1, to practice, a nurse midwife typically must attend six years of post‑secondary education and training. OB‑GYNs, on the other hand, must attend 12 years of post‑secondary education and training, including residency. This added time and the associated financial commitment come with significant costs for OB‑GYNs, often in the form of student loans. Average physician student loan debt can be as much as four times as high as the average amount for nurse midwives. These high training costs likely are compensated within the health care system through higher incomes for physicians, ultimately leading to higher women’s health care costs overall than they would otherwise be. Other key factors, such as OB‑GYNs’ ability to provide care in complex cases—which derives from their more extensive training—also likely contribute to their higher incomes. (While OB‑GYNs’ extra competencies are critical in complex cases of pregnancy, labor, and delivery, they are not necessarily needed in the case of normal childbirths—the type of births which nurse midwives are authorized to solely attend.) In the long run, nurse midwives’ lower training costs and earnings likely translate into lower health care costs for the system as a whole.

Evaluating the Impact of California’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement

The previous section largely summarized national research findings on the relative safety, quality, and cost‑effectiveness of care by nurse midwives, as well as how access to nurse‑midwife services varies based on differences among states in their occupational restrictions. This section turns to California, informed by the national research findings. First, we discuss the likely impacts on safety and quality of the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives, given the specifics of the state’s requirement and how it is implemented in practice. Second, we summarize several other quality‑assurance mechanisms applicable to the provision of women’s health care that are widely utilized or present in the health care sector. Third, we discuss the theoretical and practical reasons for how the state’s requirement could impede access to and raise costs for nurse‑midwife services. Fourth, we provide empirical evidence that access to nurse‑midwife services appears limited in California. Lastly, we bring together these components to discuss the potential impact of the state’s requirement on the safety, quality, accessibility, and costs of women’s health care services in California.

California’s Requirement Unlikely to Have Significant Impact on Improving Safety and Quality

Physician Supervision Is Not Well‑Defined… California state law establishes few parameters on what physician supervision of nurse midwives must entail. Instead, many of the terms of supervision are allowed to be determined by supervising physicians, their nurse‑midwife supervisees, and the health systems in which they work.

…Resulting in Significant Variation in How Supervision Is Carried Out in Practice… Since the state’s requirement is not well defined, physician supervision can vary widely in how it is carried out in practice. Some physician supervisors might regularly interact with their nurse‑midwife supervisees, while others might collaborate in the initial establishment of their nurse‑midwife supervisees’ scope of practice and standardized procedures and have limited subsequent involvement. In addition, health systems might interpret the responsibilities and parameters associated with the state’s physician‑supervision requirement differently. For example, we understand that some hospitals require physicians to cosign all inpatient admission orders by nurse midwives, whereas other hospitals grant nurse midwives full authority to admit patients. Along similar lines, we understand that some health systems require physicians to cosign medication orders, while others do not. (We note that state law is more prescriptive regarding physician supervision of nurse midwives who furnish medication.)

…Which Limits the Requirement’s Potential Effectiveness. We recognize that the lack of prescriptiveness in state law likely has efficiency benefits in that it allows flexibility in how the physician‑supervision requirement is implemented based on the varying competencies of individual nurse midwives. This allows, for example, varied levels of direct supervision for lesser and more experienced nurse midwives. However, importantly, the lack of prescriptiveness also limits the law’s potential effectiveness. For example, the state’s physician‑supervision requirement places no responsibilities on supervising physicians to perform quality‑assurance activities—such as periodic clinical chart reviews—with their nurse‑midwife supervisees. Accordingly, one of the major mechanisms by which a physician‑supervision requirement could improve safety and quality is not a provision within state law.

Requirement Unlikely to Significantly Improve Safety and Quality. Due to the flexibility of California’s physician‑supervision requirement, described above, we find that California’s requirement is unlikely to be any more effective than other states’ similar requirements at improving safety and quality. Given the lack of differences at the national level for safety and quality between states with and without physician oversight requirements, California’s supervision requirement specifically likely does not significantly improve safety and quality for maternal and infant health. Moreover, as described in the next section, we identify a number of other quality‑assurance mechanisms that are widely utilized in the state’s health care system that likely play an important role in ensuring the safety and quality of health care services in the state.

Role of Other Quality‑Assurance Mechanisms

The fundamental purpose of the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives is to ensure safe and high‑quality care. Previously, we discussed how licensure and certification commonly is used to achieve this purpose, including in the case of nurse midwives. Other quality‑assurance mechanisms and practices, in addition to the licensure and certification of professionals, are broadly utilized for ensuring high‑quality and safe health care. Below are several such mechanisms and practices:

- Facility‑Specific Regulation. In addition to occupational restrictions, the state regulates health care facilities with the intent of ensuring high‑quality and safe care. Such regulations can involve licensure, or a certificate that allows the performance of a specific set of services only within licensed facilities. In other cases, the state requires facilities to be accredited—which can be similar to licensure but is carried out by a nongovernmental entity. Such rules and regulations—whether by a licensing government agency or an accrediting body—typically mandate the maintenance of a safe and clean facility environment, standards for hiring qualified personnel, systems for managing confidential health information, and processes for ensuring performance improvement. Hospitals and freestanding birth centers currently are subject to licensing requirements within state law.

- Quality‑Improvement Processes. Health systems and provider groups regularly employ formalized quality‑improvement processes to assure and improve the safety and quality of their practices. At a minimum, such processes involve evaluation of past performance, comparing it to benchmarks or goals, and strategizing methods of improvement. For health care providers, for example, quality‑improvement processes regularly involve the review of patients’ clinical charts to assess whether the providers’ treatment plans met accepted standards of care. Quality‑improvement processes likely play a major role in assuring and improving the safety and quality of health care broadly, including services related to women’s health and childbirth.

- Medical Malpractice. Medical malpractice is an area of law whereby patients who believe they have received substandard health care may sue their providers for damages. The prospect of receiving a medical malpractice claim is intended to deter health care providers from providing negligent or otherwise substandard care. In anticipation of potential medical malpractice claims, both nurse midwives and physicians typically maintain medical malpractice insurance, which covers the policy holder in the face of a medical malpractice lawsuit. Medical malpractice insurance carriers generally base the rates they charge for coverage on their estimation of the risks inherent in a given provider or provider group’s practice. Accordingly, they play a role in ensuring quality by charging premium amounts based on the riskiness of providers’ practices. This provides an incentive for providers to reduce their risk by ensuring safe and high‑quality care.

- Reputational and Financial Interests Among Providers, Facilities, and Payers. Providers, facilities (such as hospitals), and payers of health care services (health plans and insurers) have an interest in showing their patients and customers that the health care they provide (often indirectly for health plans and insurers) is safe and high quality. Accordingly, hospitals regularly market themselves as being highly rated along safety and quality dimensions, while health plans and insurers often compete to provide access to highly rated hospitals and other providers within their networks. Conversely, hospitals with poor safety and quality records periodically are closed, change management, or are cut from health plans’ and insurers’ provider networks. Thus, protection of the reputational and associated financial interests of health facilities and payers work towards ensuring and improving safety and quality. Given these incentives, health systems voluntarily employ a wide variety of quality‑assurance practices, some of which we have described earlier.

How California’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement Could Impede Access and Raise Costs

There are theoretical and practical reasons to suggest that the state’s physician‑supervision requirement impedes nurse midwives’ ability to establish independent practices, as discussed further below. Through such practices, nurse midwives can build their own patient bases, with whom they can perform an array of women’s health primary care services, and also assist through labor and delivery. Primary care services take place at primary care clinics or freestanding birth centers run by the nurse midwives. Labor and delivery is attended at nearby hospitals—where nurse midwives have admitting privileges—or at freestanding birth centers. As with all nurse midwives, nurse midwives wishing to establish such independent practices must first obtain a physician supervisor under state law. As described below, physicians can be hesitant to provide statutorily required supervision, or can require compensation to provide such supervision.

To Practice, Nurse Midwives Must Obtain Consent From a Potential “Competitor.” There are a number of reasons why a physician may choose not to supervise a nurse midwife. For one, a physician may not wish to perform the added supervisory activities that they believe would fulfill their duties as a supervisor. Additionally, a supervising physician may be concerned that they could be held liable in a successful medical malpractice suit against a nurse‑midwife supervisee. Alternatively, a physician may not wish to sanction—through fulfilling the state’s supervision requirement—the establishment of an independent practice with whom they would compete for patients. The Federal Trade Commission, in its 2014 report, Policy Perspectives: Competition and the Regulation of Advanced Practice Nurses, voiced this concern, stating that “physician‑supervision requirements establish physicians as gatekeepers who control [advanced practice nurses’] independent access to the market.” As is the case in markets generally, granting a competitor the authority to prevent the establishment of rival firms undermines the ability of markets and competition to deliver high‑quality goods and services at reasonable prices. For this reason, the physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives raises anti‑competitive concerns.

Physicians Sometimes Ask for Payment in Return for Supervision. We understand that physicians sometimes ask for payment in return for agreeing to supervise nurse midwives (particularly in the case of nurse midwives who practice independently from major hospital systems and/or medical groups). Such payments can reimburse physicians for the time spent on supervision activities and can also serve to compensate physicians for any potential risk incurred should they be named in a medical malpractice suit against a nurse‑midwife supervisee. In these cases, the payments would compensate physicians for the legitimate costs and risks associated with supervision. In theory, the payment to physicians could go beyond the costs and risks associated with supervision to reflect a payment being made to allow competitors (nurse midwives) to enter the market and establish independent practices. (Such payments would not be in the public interest insofar as they only compensate physicians for authorizing the establishment of independent practices with which they would have to compete.)

Such Impediments to Nurse Midwives’ Ability to Establish Independent Practices Could Impede Access. The state’s physician‑supervision requirement could impede access in three ways. First, and most directly, nurse midwives unable to obtain statutorily required physician supervision may not establish independent practices through which patients could obtain care. Second, for nurse midwives who obtain a supervisor, the payments made in exchange for physician supervision likely are passed on to patients and payers as higher costs. Patients might obtain fewer services to the extent they or their payers have to pay these higher costs. Third, the ability of nurse midwives to compete with other providers on cost is impeded by the higher costs associated with these payments. Thus, the state’s physician‑supervision requirement might limit the establishment of additional nurse midwife‑run independent practices by making them less economically viable. Not only could these impediments limit access to nurse‑midwife services, they also could limit access to women’s health care more broadly, particularly in rural areas where services from physicians may not be readily available.

Evidence for Limited Access in California

In the previous section, we discussed the theoretical and practical reasons for how California’s physician‑supervision requirement could limit access to nurse‑midwife services—and potentially women’s health care services more broadly. In this section, we describe empirical evidence specific to California that suggests nurse‑midwife services might be undersupplied relative to the demand for their services, thereby suggesting access to their services could be limited. The first two pieces of evidence relate to potential limits in access to labor and delivery care by nurse midwives. The second two pieces of evidence show that (1) nurse‑midwife services overall appear to be in high demand and (2) access to women’s health care services overall could be limited in the more rural and inland areas of the state.

Nurse‑Midwife Care Potentially Is Appropriate for More Women Than Are Currently Served in the State. Research suggests that between 50 percent and 75 percent of births are normal and therefore eligible for nurse‑midwife services. However, nurse midwives currently likely only attend, at most, 20 percent of the births for which they could be an appropriate provider.

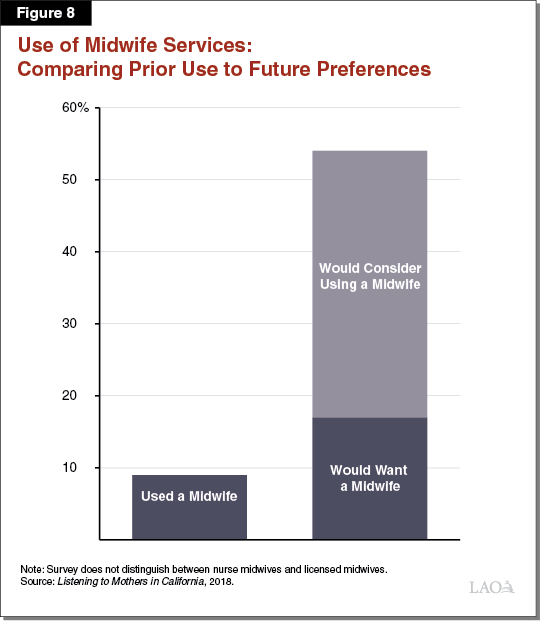

Survey Data Indicate a Higher Proportion of Women Want Than Receive Midwife Services. The Listening to Mothers in California survey showed that 17 percent of survey participants (mothers who gave birth in California in 2016) would definitely want to utilize a midwife’s services. (The survey question does not distinguish between nurse midwives and licensed midwives.) An additional 37 percent of survey participants said that they would consider utilizing a midwife’s services, bringing the total percent of women who would at least consider a midwife’s services to 54 percent. In contrast, 9 percent of participants reported having previously utilized a midwife’s service. Figure 8 summarizes these survey findings. The survey found, however, that among mothers who would have preferred to use a midwife, 25 percent reported experiencing health problems necessitating referral to a physician rather than a midwife. A significant portion of the remaining 75 percent cited reasons related to access—defined as the ability to have an appropriate and preferred provider—for why they did not use midwife services. Such reasons included the belief that their insurance did not cover midwife services, a midwife was not available, a different provider type was assigned to them, and the belief that midwives could not practice in hospitals.

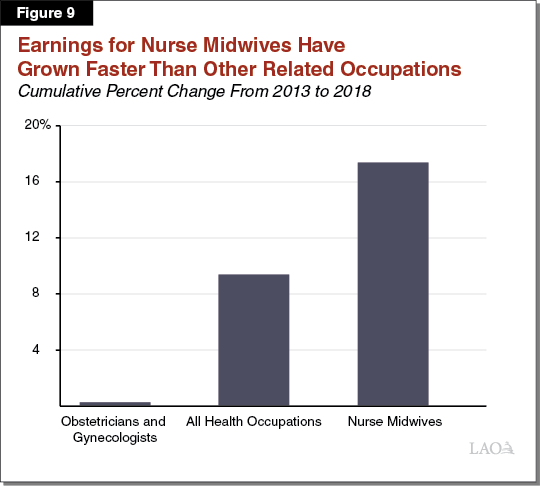

Robust Growth in Earnings Suggests Demand for Nurse‑Midwife Services May Exceed Supply. Robust growth in earnings over time for an occupation can provide evidence that demand for the services provided by members of the occupation exceeds supply. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that between 2013 and 2018 nurse midwives’ average salaries increased at a faster rate than those for both OB‑GYNs and health care practitioners generally in California. Figure 9 shows these trends. This provides further evidence suggesting that demand for nurse midwives exceeds their supply.

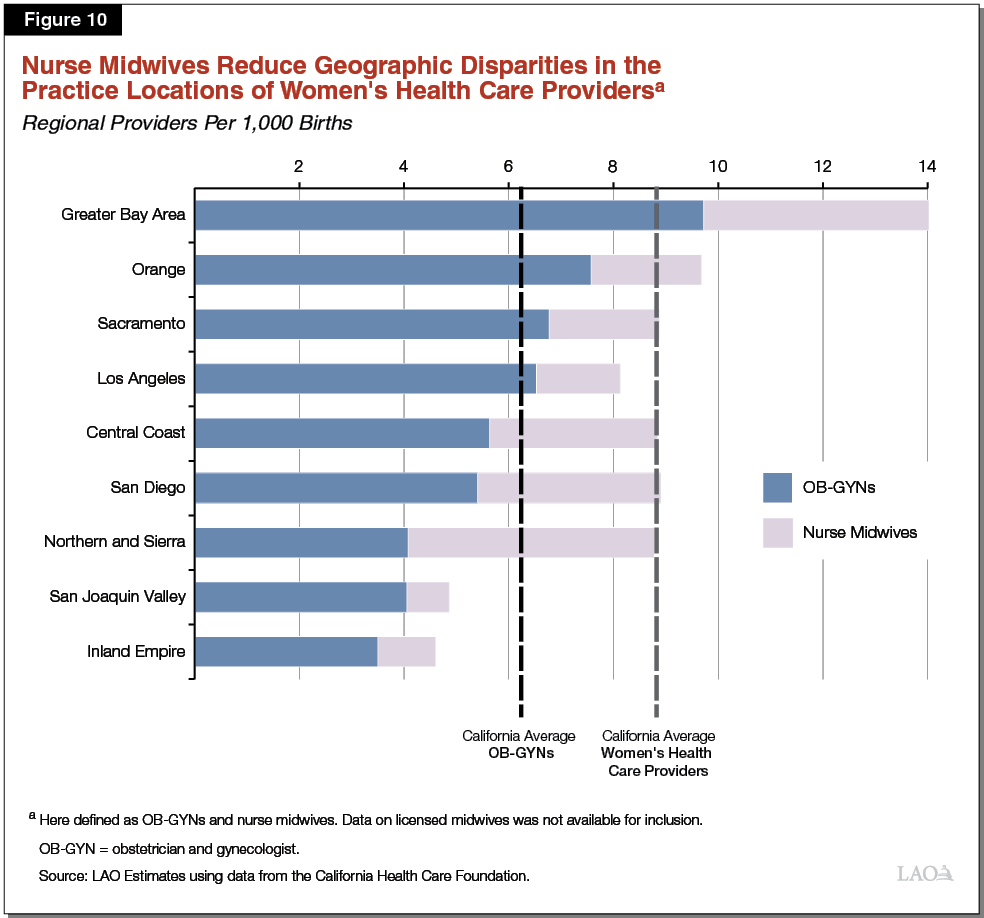

Geographic Disparities in Access to OB‑GYNs. As with other physicians in California, OB‑GYNs tend to practice disproportionately in certain regions of the state. For example, as shown in Figure 10, the Greater Bay Area has nearly three times as many OB‑GYNs per 1,000 births than the Inland Empire—and over 50 percent more than the statewide average. The San Joaquin Valley and northern and Sierra regions of the state also have significantly fewer OB‑GYNs per 1,000 births than the more urban and coastal regions of the state. This suggests that—when only counting OB‑GYNs—access to women’s health care services might be limited in certain areas of the state. Later in the report, we describe how nurse midwives could serve to fill the gaps in access in the more rural and inland regions of the state.

Requirement Likely Is a Factor Contributing to Limited Access to Nurse‑Midwife Services

Bringing together our various findings discussed previously, in our assessment, California’s physician‑supervision requirement likely is a factor contributing to limited access to nurse‑midwife services in the state, and potentially to women’s health care services overall. First, as previously discussed, national research shows that states without occupational restrictions such as physician oversight have proportionately more nurse midwives and more births attended by nurse midwives. Second, physician control over nurse‑midwife access to the market through supervision requirements provides a sound theoretical and practical mechanism by which such requirements could limit access to nurse‑midwife services, and women’s health care services overall. Third, we find empirical evidence that access to nurse‑midwife services—and potentially women’s health care services overall, at least in certain regions of the state—is limited.

Possible Effects of Removing California’s Physician‑Supervision Requirement

Enacting policies to increase access to nurse‑midwife services could increase access to women’s health care services, generally maintain safety and quality, and lower costs. Removing California’s physician‑supervision requirement reflects one promising avenue to do so. In this section, we assess the potential impact of removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement from state law on the safety and quality, access, and cost‑effectiveness of women’s health care, including labor and delivery care.

Impact on Safety and Quality Could Be Positive, Particularly in Hospital Settings

Potentially Positive Impact on Safety and Quality in Hospital Settings, the Most Common Setting for Childbirth. In our assessment, removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives could improve the safety and quality of labor and delivery care in hospital settings, provided the removal leads to greater utilization of nurse‑midwife services in these settings. As noted earlier, for low‑risk births, nurse midwives utilize fewer interventions, which can improve safety and quality.

On Balance, Uncertain but Likely Limited Impact on Safety and Quality Outside of Hospital Settings. There is greater uncertainty regarding the impact on safety and quality that removing the requirement would have on care provided by nurse midwives outside of the hospital—including labor and delivery care in nonhospital settings and women’s primary care.

- Labor and Delivery Care. On the one hand, independent practice for nurse midwives may lead to greater utilization of labor and delivery care outside of the hospital setting in freestanding birth centers and homes, where there is greater uncertainty related to the safety and quality of care. While this development would be positive from a patient‑choice perspective, it could come with added risks for mothers and their infants relative to the care that otherwise would have been provided in a hospital setting. On the other hand, removing the physician‑supervision requirement could increase the safety and quality of care for women who otherwise would still have elected to deliver outside of the hospital. Removing the physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives may encourage more nurse midwives to attend home births, and thereby increase the average training and credential levels of attendants of home births.

- Primary Health Care. A number of studies indicate that the safety and quality of pre‑ and postnatal care are comparable regardless of whether the provider is a nurse midwife or a physician. However, we found relatively few studies on the safety and quality of nurse midwife‑delivered primary care services not directly related to pregnancy and childbirth. Accordingly, the safety and quality of primary care services delivered by nurse midwives is somewhat uncertain. That said, studies do show that the safety and quality of primary care delivered by nurse practitioners is comparable to physicians. Since (1) nurse‑midwife education and training on primary care services is comparable to that of nurse practitioners and (2) about half of California’s nurse midwives also are certified nurse practitioners, we find it likely that the safety and quality of such care would be roughly comparable for nurse midwives and physicians.

On balance, we find that removing the physician‑supervision requirement would have a limited but somewhat uncertain impact on safety and quality outside of hospital settings.

Potential to Improve Access

Potentially Positive Impact on Access to Nurse‑Midwife Services in Hospital Settings. As previously discussed, survey data indicate more women are eligible for and desire midwife services than currently receive them in the state. Removing California’s physician‑supervision requirement could potentially facilitate more low‑risk births being attended by nurse midwives. As previously discussed, states with fewer occupational restrictions on nurse midwives—including physician‑supervision and collaboration‑agreement requirements—tend to have more nurse midwives, the majority of whom likely practice in hospital settings. By removing California’s physician‑supervision requirement, more hospitals might grant broader admitting privileges to nurse midwives, improving their employment prospects and making the profession more attractive to individuals deciding among careers. Rural hospitals, where we understand nurse midwives have greater challenges finding physician‑supervisors, would no longer face this barrier to employing nurse midwives.

Removing Requirement Could Encourage the Establishment of Independent Clinics and Freestanding Birth Centers. Removing the physician‑supervision requirement for nurse midwives would remove a barrier—namely, obtaining a physician’s consent—that currently impedes nurse midwives’ ability to establish women’s health clinics or freestanding birth centers, as well as their ability to attend home births. As such, removing this requirement could encourage greater access to services in these settings, and in doing so give expectant mothers more options as alternatives to delivering in a hospital setting. Previously, we discussed the potential safety and quality impacts of such developments.

Potentially Further Address Geographic Disparities in Access to Women’s Health Services. In California, OB‑GYNs tend to practice disproportionately in certain regions of the state. Figure 10 shows that the Greater Bay Area, Orange County, the Sacramento region, and Los Angeles have more practicing OB‑GYNs per 1,000 births than the statewide average. The remaining five regions of the state have fewer practicing OB‑GYNs per 1,000 births. As Figure 10 also shows, nurse midwives fill the gaps in women’s health care in three of the five regions with relatively few OB‑GYNs: the Central Coast, San Diego, and the northern and Sierra counties. Thus, while there are five regions in the state with relatively limited access to women’s health care services when only counting OB‑GYNs, just three regions of the state have relatively limited access (by this measure) once nurse midwives are counted as providers. This shows that nurse midwives, as a profession, have the potential to fill gaps in coverage in the areas of the state where relatively few OB‑GYNs practice. Removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement is a means by which the state could increase the number of nurse midwives and—particularly given the constraints on rural hospitals previously discussed—address geographic disparities in access to women’s health care services.

Likely Improve Cost‑Effectiveness

By reducing costs and potentially increasing access to nurse‑midwife services—without significantly reducing safety or quality—removing the state’s physician‑supervision requirement has the potential to improve the cost‑effectiveness of women’s health care services. We expect costs to be lower due to the following factors:

- Care Delivered by Less Costly Providers. In California, nurse midwives earn about 60 percent of what OB‑GYNs earn. In part, this likely is due to the lower costs of training a nurse midwife compared to an OB‑GYN, as well as different demands for their respective skill sets. Accordingly, by increasing the relative amount of care appropriately delivered by nurse midwives, the state’s health system could achieve savings.

- Reduce the Use of Costly Labor and Delivery Interventions. National research shows that nurse midwives tend to employ fewer costly labor and delivery interventions—such as episiotomies and cesareans—than OB‑GYNs. By increasing the proportion of births attended by nurse midwives, fewer costly interventions might be utilized in the state, thereby reducing labor and delivery costs.

- Removal of the Costs Associated With Physician Supervision. Physician supervision imposes costs on the health system in a number of ways, three being (1) the payments made by nurse midwives to physicians in exchange for supervision, (2) the absence of greater competition among providers due to the anti‑competitive nature of the physician‑supervision requirement, and (3) any medical malpractice liability physicians bear as supervisors. By removing the requirement, these costs would be eliminated and likely would not be fully offset by other added costs, such as those associated with other forms of increased health system oversight and professional collaboration related to the care provided by nurse midwives.

Specifying Responsibilities of Physician Oversight Has Drawbacks

While the Lack of Definition of Responsibilities of Physician Supervision Does Likely Impede the Law’s Effectiveness… Previously, we discussed why the lack of definition in the state’s physician‑supervision requirement makes it unlikely that the requirement is effective in significantly improving the safety and quality of maternal and infant health care. Therefore, one way safety and quality might be improved would be to add definition and parameters to the state’s physician‑supervision requirement. For example, some states set maximum geographic distances from which a physician can supervise a nurse midwife. As another example, some states mandate periodic reviews of the nurse midwives’ clinical chart by their physician supervisors.

…Adding Definition and Parameters to Physician Supervision Does Not Reflect the Best Approach. Further defining the state’s physician‑supervision requirement would not address the current competition issue—specifically, granting potential competitors (physicians) the power to control nurse midwives’ access to the market. As noted earlier, we believe this issue might be limiting access to nurse‑midwife services in the state, and potentially to women’s health care services more broadly. Moreover, this approach would make the tasks associated with supervision more burdensome, potentially making supervision less attractive to physicians, and thereby further impeding nurse midwives’ ability to practice.