LAO Contact

March 13, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Hastings College of the Law

In this post, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for the Hastings College of the Law (Hastings). We first provide background on the law school and its budget. Next, we describe the Governor’s budget proposals and Hastings’ associated budget plan. We then assess the proposals and make associated recommendations.

Background

Hastings Is an Independent Public Law School. California has five public law schools. The University of California (UC) operates four of these schools—at its Berkeley, Los Angeles, Davis, and Irvine campuses. The fifth school, Hastings, is affiliated with UC but operates independently in many respects, having its own governing board (known as the Board of Directors). Hastings’ board has similar responsibilities as the UC Board of Regents, including establishing policy, ratifying collective bargaining agreements, adopting budgets, and setting student tuition and fee levels. Hastings’ affiliation with UC offers it certain benefits. For example, Hastings uses UC’s payroll processing and investment management services. Additionally, Hastings’ employees participate in UC’s employee health and pension programs.

Hastings Is Receiving $59.5 Million Ongoing Core Funding in 2019‑20. Hastings receives almost three-fourths of its operational funding from student tuition and fee revenue. About one-quarter of its funding comes from the state General Fund. Beyond these two core fund sources, the school receives funding from a few smaller sources, including the state lottery and investment income.

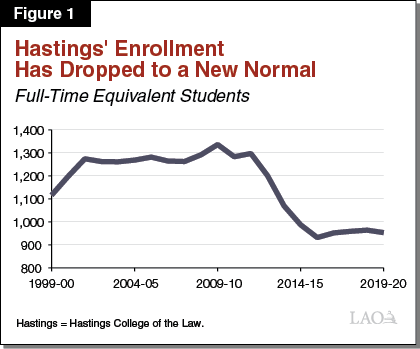

After Notable Decline, School’s Enrollment Has Stabilized. Hastings is enrolling 953 full-time equivalent students in 2019‑20, of which the vast majority are enrolled in its juris doctor program. (Hastings also offers two master’s programs.) As Figure 1 shows, this enrollment level is notably lower than enrollment levels throughout the 2000s. From 2009‑10 through 2015‑16, Hastings enrollment declined by 30 percent. Many other public and private law schools experienced similar declines, with enrollment nationally declining by 20 percent. (Declines tended to be more substantial for less selective schools.) Since 2015‑16, Hastings’ enrollment level has stabilized at what appears to be a new normal, hovering between 930 and 960 students.

Hastings Is Unwinding Its Tuition Discounting Initiative. Historically, Hastings has spent about 30 percent of tuition revenue on tuition discounts for certain students. Similar to most graduate programs, Hastings’ tuition discounts are based primarily on students’ academic merit (rather than financial need). In 2015‑16, Hastings began increasing its tuition discount rate, with the discount rate exceeding 40 percent for several student cohorts. Hastings raised its discount rate to attract students with better academic records. In implementing the higher discount rate, Hastings indicates that it recognized its operating budget would begin running deficits. Hastings has been covering the annual operating deficits primarily by using its unrestricted reserves. The school has since begun reducing tuition discounting, returning to the previous 30 percent discount rate for incoming student cohorts (beginning with the fall 2019 cohort). Because previous cohorts with higher discount rates remain enrolled, Hastings continues to have a deficit, but the size of the deficit is shrinking and is expected to be eliminated by 2021‑22. For 2019‑20, Hastings anticipates having an operating deficit of $5.1 million—$6.6 million smaller than its 2018‑19 deficit. Hastings projects having an unrestricted reserve of $8.6 million—equating to 13 percent of its annual operating expenses.

Hastings Has Received General Fund Base Increases the Past Seven Years. Beginning with the 2013‑14 budget, the state has provided Hastings unrestricted General Fund base increases each year. Rather than linking these augmentations to enrollment changes, the state typically has loosely linked them to inflationary increases in Hastings’ core budget. (In some years, state funding increased even as Hastings’ enrollment dropped.) State augmentations have been the school’s primary source of funding to cover annual cost increases. During these years the school’s tuition charge ($43,486) remained flat. The state-funded base increases have helped Hastings cover higher salaries, benefit costs, and other operational cost increases. The state augmentations also have reduced pressure on Hastings’ reserves in the years that the school has run deficits. (In the nearby box, we discuss the Legislature’s efforts to tie future funding for Hastings more closely to enrollment.)

Marginal Cost Formula for Hastings

Legislature Has Taken First Step Toward Funding Hastings Based on Enrollment. The state’s budgetary approach for Hastings College of the Law (Hastings) is highly unusual in that it is not based on the number of students the school serves. In 2015‑16, the Legislature sought to set the basis for future enrollment-based budgeting by directing Hastings to develop a marginal cost formula, similar to the formula the state uses to fund enrollment growth at the University of California. (This formula estimates the increase in operating costs associated with adding one new student.) This action was in response to state funding for Hasting increasing significantly even as the school’s enrollment dropped significantly. In its fall 2015 report to the Legislature, Hastings estimated a total marginal cost of $34,513, with a student tuition share of $29,910 and a state share of $4,705. The state has not directed Hastings to update the marginal cost calculation since 2015.

Proposals

Governor Provides Ongoing General Fund Base Increase to Hastings. The Governor connects the proposed $1.4 million increase to avoiding a tuition increase. Specifically, the administration states that the General Fund augmentation is equivalent to the amount of revenue that would be generated from a 5 percent tuition increase. The augmentation equates to a 9.1 percent increase in state General Fund support for the school. As in past years, the Governor proposes that the additional state funding be general purpose, with no specific associated spending requirements.

Governor’s Budget Covers Increase in Lease Revenue Debt Service. The proposed $3.5 million covers the debt service for a facility project that the state approved in the 2015‑16 budget. Specifically, Hastings constructed a new academic building. The building is intended to replace an existing building known as Snodgrass Hall, which Hastings plans to demolish later in 2020. Hastings expects to begin occupying the new building this spring.

Hastings’ Budget Plan

Hastings’ Recently Submitted a 2020‑21 Budget Plan. Shortly after release of the Governor’s budget, Hastings submitted a budget plan to our office. As discussed in more detail below, the plan summarizes how Hastings would spend the Governor’s proposed augmentation. The plan also includes multiyear budget projections. Figure 2 summarizes the key aspects of the budget plan for 2020‑21.

Figure 2

Hastings’ 2020‑21 Plan Uses Bulk of

Augmentations for Operating Deficit

(In Thousands)

|

Augmentations |

|

|

State General Fund base increase |

$1,388 |

|

Tuition from enrollment growth |

1,564 |

|

Total |

$2,952 |

|

Spending Changes |

|

|

Operations |

|

|

Salaries |

$693 |

|

Employee benefits |

160 |

|

Operating expenses and equipment |

86 |

|

Subtotal |

($939) |

|

Financial aid |

‑$457 |

|

Total |

$482 |

|

Existing Operating Costsa |

$2,470 |

|

aReflects portion of operating deficit covered with proposed augmentations. Hastings projects a remaining deficit of $2.1 million, which it plans to cover with its reserves. Hastings = Hastings College of the Law. |

|

Hastings Anticipates Additional Revenue From Enrollment Growth. Unlike for UC, the state does not have a standard approach for adjusting Hastings’ budget for changes in enrollment. In recent years, the school has kept staffing levels steady regardless of changes to enrollment. Thus, in years when enrollment has grown, the school has received more tuition revenue to cover its operating costs. Conversely, reductions in enrollment have resulted in less tuition revenue to cover the school’s operating expenses. In 2020‑21, the school anticipates enrolling 993 students, an increase of 40 students (4.1 percent) above the level estimated in 2019‑20. The enrollment growth would generate $1.6 million in additional tuition revenue, coupled with various other small revenue adjustments.

Hastings Anticipates Increasing Ongoing Operational Costs. Under the school’s 2020‑21 budget plan, Hastings would increase ongoing operational spending by $939,000, consisting of increases in salaries (3 percent), operating expenses and equipment (OE&E, 1.1 percent), and employee benefit costs (1 percent). Partly offsetting these operational cost increases, Hastings’ reduction in tuition discounting is expected to lower its financial aid spending by $457,000. Taken together, net ongoing spending would increase by $482,000 in 2020‑21.

Hastings Uses Bulk of Augmentation to Address Deficit. After covering operational cost increases, Hastings would use the remaining $2.5 million combined General Fund and tuition revenue augmentation to address its deficit. Effectively, this amount helps Hastings cover existing ongoing costs. After applying the augmentation, Hastings is projecting a remaining operating deficit of $2.1 million. The school’s unrestricted reserves would cover this deficit. The school estimates it would end 2020‑21 with $6.5 million in unrestricted reserves—equating to 9 percent of its annual operating expenses.

Hastings Multiyear Plan Shows Surpluses. Under the school’s five-year budget plan (2019‑20 through 2023‑24), 2020‑21 would be the final year of deficit spending. In 2021‑22, Hastings anticipates having a budget surplus of approximately $900,000, with its budget staying balanced the subsequent two years. The plan does not assume any additional augmentations from the state over the period. Instead, Hastings would cover costs by increasing student tuition levels by 5 percent annually. As this budget plan make numerous assumptions regarding funding and spending, the estimates are subject to some uncertainty.

Assessment

Similar to its decisions for UC and the California State University, the Legislature must decide each year the cost increases to support at Hastings and how to share those costs between the state General Fund and student tuition revenue. With Hastings, the Legislature has the added complication of deciding how best to address the school’s operating deficit. Below, we assess Hastings’ costs and the main options available for covering those costs.

Costs

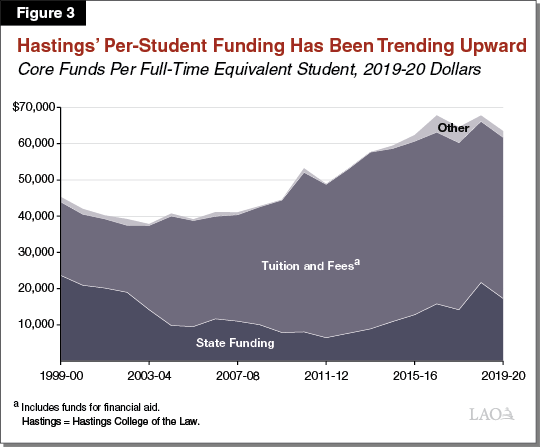

Proposed Cost Increases Are Typical but Two Issues Complicate Matters. Hastings’ planned cost increases (for salaries, benefits, and OE&E) are in line with increases generally being requested by other state agencies. Hastings faces two budget issues, however, that make its budget situation somewhat unusual. First, unlike most other state agencies, Hastings has an operating deficit—meaning that its core revenue is falling short of being able to cover even its existing operating costs. Second, Hastings has seen particularly high growth in its per-student costs over the past decade. Because Hastings received budget augmentations in years in which its enrollment notably declined, its funding per student has far outpaced inflation (Figure 3). These two factors indicate that efforts might be warranted to reduce Hastings’ costs.

Actions to Reduce Costs Seem Reasonable but Further Options Could Be Explored. Given the school’s deficit and relatively high growth in per-student costs, Hastings’ plans to reduce its tuition discounting and increase its enrollment without a corresponding increase in staff seem warranted. The key question before the Legislature is whether these actions go far enough in 2020‑21 or whether further budget adjustments should be made.

State Funding Remains Disconnected From Enrollment. For most higher education institutions, enrollment is a key cost driver. The Governor’s proposal for Hastings, however, is not tied at all to enrollment. The Governor neither sets an enrollment target for Hastings nor establishes a way to adjust Hastings’ funding in response to enrollment changes.

Covering Costs

Hastings’ Reserves Are No Longer a Prudent Tool for Addressing Its Deficit. If Hastings had a very large unrestricted reserve, the Legislature might consider gradually drawing down the reserve to help the school right-size its budget over a multiyear period. Hastings, however, already has substantially reduced its unrestricted reserve. At the end of 2020‑21, Hastings projects having an unrestricted reserve equating to 9 percent of its annual operating expenses—reflecting around a one-month cash supply. Given Hastings’ heavy reliance on tuition revenue and enrollment-related uncertainties, further significant reductions in its reserve level may pose budget risks.

State Share of Hastings’ Budget Has Increased in Recent Years. As we noted in our recent publication The 2020‑21 Budget: Higher Education Analysis, the state does not have a formal policy for any of its higher education segments specifying how it should share education costs with students. The share of Hastings’ core funding coming from the state is higher today than ten years ago but lower than 20 years ago. Specifically, we estimate the state share of core funding in 2019‑20 was 37 percent, compared to 22 percent in 2009‑10 and 61 percent in 1999‑00. (These estimates are based on state General Fund and net tuition revenue, after accounting for tuition discounts. Including tuition discounts overstates the student share of cost.) Much like for UC, the state’s funding decisions for Hastings have largely been driven by the economic cycle. During economic expansions when General Fund revenue is growing, the state has opted to increase state support and keep tuition flat. Conversely, during economic downturns, the state has reduced General Fund revenue and supported tuition increases.

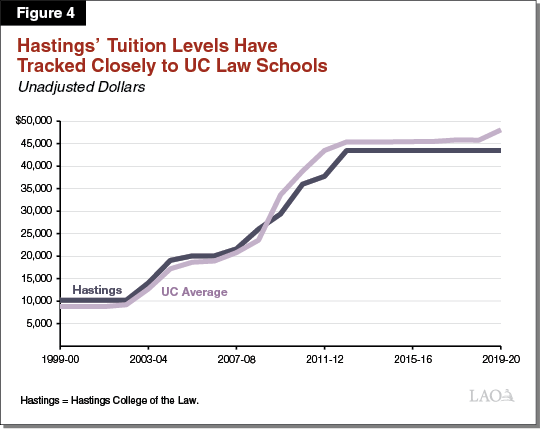

UC Regents Started Raising Law School Tuition Last Year. If the Legislature were not comfortable with Hastings’ growing reliance on state funding over the past ten years, it could consider supporting tuition increases at Hastings. As Figure 4 shows, Hastings’ total tuition charge has tracked closely with the tuition level of UC law schools. From 2002‑03 to 2012‑13, tuition increased more than fourfold at both Hastings and UC law schools. Since 2012‑13, tuition has been about flat. In 2019‑20, the UC Board of Regents elected to raise total tuition systemwide charges for its law schools, with increases ranging from 3.7 percent (Davis) to 5.5 percent (Berkeley). A couple of months ago, the Board of Regents adopted a multiyear plan to continue increasing law school tuition through 2023‑24.

California Public Law Schools Are Relatively Costly. Although UC raising tuition at its law schools might make the Legislature more inclined to consider increases at Hastings, tuition at California’s public law schools already is notably higher than other public law schools around the country. In 2019‑20, their resident tuition charges range from around 70 percent more to double those of other public law schools. California students also tend to face higher living costs relative to students at many other law schools across the country, resulting in a higher total cost of attendance. Though these costs are higher in California, its public law schools might be offering more general financial aid packages to offset some or all of the higher costs. Unfortunately, data on tuition discounting are incomplete. The limited data that are available suggest that the total cost of attendance remains higher in California than the national average even after accounting for financial aid.

Hastings Graduates Have Above Average Debt Burdens. Law students in California and across the nation rely heavily on borrowing to help cover tuition and living expenses. In California, public law school graduates tend to have higher debt than graduates from public law schools in other states. California graduates, however, also tend to earn higher salaries upon entering the workforce, resulting in a mixed picture as to their relative ability to manage their debt. According to data compiled by law school experts, the average Hastings graduate spends 28.5 percent of their first-year income on annual debt payments. This ratio is higher than the median burden at public law schools nationally (23.1 percent). Graduates at UC law schools tend to have lower burdens, with the average ranging from 15.6 percent (Berkeley) to 24.4 percent (Irvine).

Recommendations

Discuss Hastings’ Budget Plans at Spring Hearings. To evaluate the proposed base increase, we recommend the Legislature review Hastings’ budget plan and discuss the plan at a spring hearing. As part of its review, we encourage the Legislature to consider Hastings’ multipronged approach of increasing overall operational spending, reducing tuition discounting, growing enrollment, and eliminating its deficit through a combination of additional state funding, tuition revenue, and reserves. Though other options could be considered, the Legislature could support Hastings’ tuition discounting and enrollment plans, as both factors help reduce the school’s operating deficit. The Legislature also could support Hastings’ plan to draw down its reserve to help eliminate its deficit, though we advise against any other actions that would further reduce Hastings’ reserve given its already low level. Deciding what costs to support with a state General Fund augmentation is arguably the most difficult decision facing the Legislature, as the decision depends upon the Legislature’s competing budget priorities and view of Hastings’ current cost per student.

Consider Tuition Increases. As part of its budget decisions, the Legislature will want to decide whether to support a tuition increase. We recommend the Legislature weigh all the trade-offs we described in the “Assessment” section. We estimate every 1 percent increase in Hastings’ tuition charge would generate $282,000 in additional tuition revenue to support the school’s operations.

Explore Ways to Link State Funding More Closely to Enrollment. Ideally, the Legislature would develop a comprehensive understanding of the key drivers of law school enrollment, as well as a corresponding method for setting an annual enrollment target for Hastings. Consistent with its approach for UC, we think the enrollment target for Hastings would be set for budget year plus one, such that the Legislature could influence Hastings’ fall admission cycle, which typically concludes in the spring prior to enactment of the state budget. In the future, the Legislature could use the marginal cost formula that Hastings has developed (or a variant of it) to fund enrollment growth. (Presumably, the Legislature would want Hastings’ operating deficit eliminated and its per-student costs at an approved level before funding enrollment growth.) Over the coming year, the Legislature could work with Hastings informally to discuss how to begin moving toward this type of enrollment-based budgeting.

Adopt Lease-Revenue Augmentation. Given the new debt service costs Hastings faces in 2020‑21, we have no concerns with the proposed $3.5 million augmentation and recommend the Legislature approve it.