LAO Contact

March 19, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Governor’s Fiscal Oversight Proposals

In this post, we provide background on fiscal oversight of school districts in California, describe the Governor’s proposals to augment oversight and reporting requirements related to school district budgets, assess those proposals, and provide associated recommendations.

Background

School Districts Must Have Their Budgets Approved by Their County Office of Education (COE). Before the start of each fiscal year, districts are required to submit their locally developed budget plans to their respective COEs for review. COEs are tasked with determining whether these budgets will allow school districts to meet their current and future financial obligations. COEs must approve budgets that meet those criteria and either disapprove or conditionally approve budgets that do not. Districts with disapproved budgets must revise and resubmit their budgets until they are approved by their COE. In making their determinations, COEs consider ten core indicators of district fiscal health, including reserve levels and changes in salary and benefit costs.

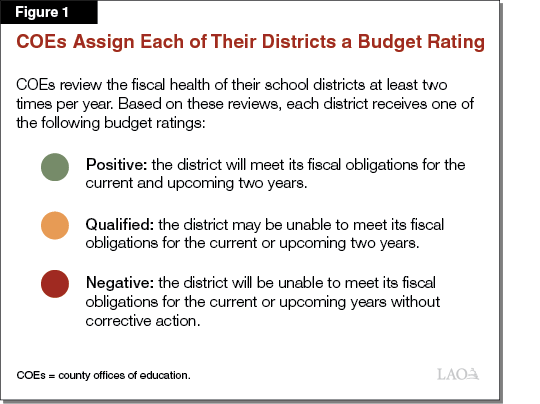

Districts Also Have Fiscal Health Assessed Twice Per Year. During the fiscal year, districts are required to submit two budget updates, or “interim reports,” to their COE—one in the fall and another in the spring. For each of these budget updates, COEs assign a positive, qualified, or negative certification. Figure 1 explains each of these terms.

Districts With Poor Budget Ratings Receive Intensified COE Support and Intervention. Districts with qualified and negative budget ratings are subject to escalating COE oversight and intervention. For all qualified or negative districts, COEs must review a third interim budget report at the end of the school year, review and comment on proposed district collective bargaining agreements, and approve the issuance of certain types of district debt. As Figure 2 shows, statute requires COEs to take additional action with fiscally distressed districts, but provides substantial discretion for COEs to decide on the best approach. COE interventions are designed to escalate as problems persist or become more severe, such that districts with a negative budget rating will receive greater intervention than those with a qualified rating.

Figure 2

County Offices of Education Are Required to Assist Districts in Fiscal Distress

County Offices of Education Must Do At Least One of the Following

|

For Qualified Districts: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For Negative Districts: |

|

|

|

|

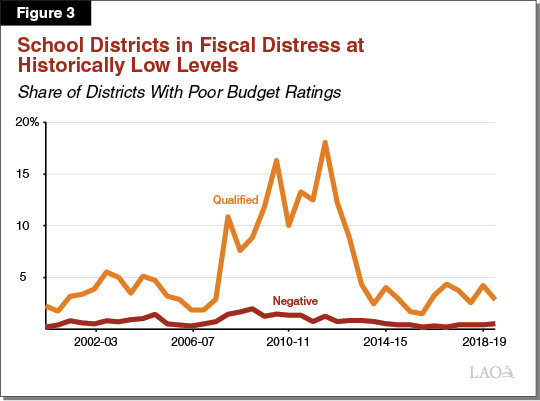

School Districts With Poor Budget Ratings Are at Historically Low Levels. The vast majority of districts in California have positive budget ratings. Of the nearly 1,000 districts currently operating, only five received a negative fiscal rating in the spring 2018-19 reporting cycle. An additional 27 received qualified ratings. As Figure 3 shows, the share of districts currently in distress is near a historic low and significantly below the peak during the Great Recession. The historically strong growth in school funding since 2013-14 likely is one reason so few districts have poor budget ratings today. Another reason likely is that many districts are well managed, with a consistent focus on good management practices. Most districts, for example, have accurate budget projections and deliberately plan for cost increases in key areas such as pensions and special education. Although few districts receive poor ratings consistently, a relatively small group of chronically distressed districts have received multiple qualified or negative ratings over the past few years.

Districts That Do Not Recover After COE Intervention May Receive Emergency Loans. If a district does not have cash on hand to pay its bills, its local school board may request an emergency loan from the state. If the Legislature and Governor approve the request, the loan is authorized through a state appropriations bill. Upon receiving a state loan, the local governing board loses its authority and an administrator is appointed to run the district. The applicable county superintendent of schools appoints the administrator, with the concurrence of the state Superintendent of Public Instruction and the president of the State Board of Education. The local board typically regains power gradually over several years after it has demonstrated good management in five specified areas—financial management, student achievement, personnel management, facilities management, and community relations. Since the state’s oversight system was enacted in 1991, nine districts have received emergency state loans. Four school districts currently have active emergency loans: Inglewood Unified, Oakland Unified, Vallejo City Unified, and South Monterey County Joint Union High.

Governor’s Proposals

Administration Proposes Several Modifications to Fiscal Oversight of Districts. As part of the Governor’s 2020-21 budget, the administration proposes budget trailer legislation to make several changes to how COEs assess district health and oversee district collective bargaining agreements. The budget also makes changes to the authority that COEs and the Fiscal Crisis and Management and Assistant Team (FCMAT) have in supporting fiscally distressed districts. Figure 4 summarizes the Governor’s key proposals.

Figure 4

Governor Proposes Several Changes to Fiscal Oversight of School Districts

|

Current Law |

Proposal |

|

Assessment of District Fiscal Health |

|

|

Specifies that, in reviewing a district’s fiscal health and weighing whether to approve its proposed budget, the county office of education (COE) is to consider if an external reviewer finds the district meets more than 3 out of 15 commonly used predictors of fiscal distress, as determined by the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT). |

Changes the external review to be based on common indicators of moderate or high fiscal risk, as determined by FCMAT. |

|

Review of Collective Bargaining Agreements |

|

|

Requires a qualified or negative district to give its COE ten days to review and comment on any proposed collective bargaining agreement. |

Extends requirement to all districts and to agreements made with employees not represented by a union. |

|

Requires the county superintendent to notify the district and county board of education within ten days whether the agreement would endanger the district’s fiscal health. |

Requires the county superintendent to also notify the union that negotiated the agreement. |

|

Requires local school boards to solicit public comment and disclose labor costs associated with employees covered by a collective bargaining agreement. |

Adds similar requirement for agreements with employees not represented by a union. |

|

Requires the district superintendent and chief business official to certify in writing that the district can meet the costs of a negotiated collective bargaining agreement. |

Requires this certification to be signed under penalty of perjury. |

|

Authority Over Fiscally Distressed Districts |

|

|

Allows COEs to assign FCMAT to review how fiscally distressed districts manage their teacher workforces. |

Allows COEs to have FCMAT conduct a broader review of district budget practices and financial projections. |

|

Allows COEs to stay or rescind certain actions taken by fiscally distressed districts until the subsequent year’s budget is approved by the COE. Does not specify whether COEs retain this authority if it disapproves the district’s budget. |

Allows COEs to retain stay and rescind authority for another year if the district’s budget is disapproved by the COE. |

Assessment

Governor’s Proposals Address a Few Key Fiscal Oversight Issues. Most of the county officials and superintendents we interviewed over the past several months indicated that governance and management issues are common among fiscally distressed districts. Another common characteristic is lack of fiscal expertise. Fiscally distressed districts often enter into labor agreements that they cannot sustain on an ongoing basis. Additionally, multiple COE officials and superintendents suggested that the state’s current indicators for assessing fiscal distress are incomplete and assign positive ratings to districts that are under a relatively high degree of fiscal pressure. We find that the Governor’s proposed changes generally address these issues and that most of the changes would improve the state’s fiscal oversight system. However, we have also identified a couple of concerns with the proposed changes that merit legislative consideration. Below, we discuss our assessment of these proposals in more detail.

Revised Fiscal Indicators Will Likely Provide a Fuller Assessment of District Fiscal Health. Under current law, a COE may identify a district as fiscally distressed if an external reviewer finds the district meets more than 3 out of 15 standard predictors, as determined by FCMAT. These predictors include administrative issues, such as limited access to timely personnel, payroll, and budget data, as well as financial issues such as flawed multiyear projections. Although some of these predictors may be greater risk factors than others, statute directs external reviewers to weigh all 15 predictors equally. This approach also does not distinguish between moderate and severe fiscal distress. The Governor’s proposal would replace the 15 predictors with a set of indicators determined by FCMAT that would test for moderate or high financial risk. Based on our conversations with FCMAT, COEs would use a fiscal health risk analysis tool similar to one already developed by FCMAT. This tool, which FCMAT has posted on its website, includes more detailed questions, assigns different weights to particular questions, and distinguishes between moderate and high risk. We believe this more detailed tool would serve as a better diagnostic tool than the 15 predictors that are currently used.

Additional Oversight and Disclosure Requirements Could Bring Greater Scrutiny of Costly Collective Bargaining Agreements. Requiring COEs to review all collective bargaining agreements would provide better information for fiscally distressed districts and the public prior to the approval of any new agreement. Given entering into an unsustainable collective bargaining agreement can put a district into fiscal distress, we think the additional review would also benefit districts with a positive budget rating. Some COEs report they already review all proposed district collective bargaining agreements and consider it a best practice. We believe the other oversight proposals also would improve oversight of collective bargaining agreements. Requiring COEs to review agreements for nonunion employees would help ensure all labor costs are being carefully monitored. Similarly, notifying relevant labor unions of any concerns the COE has with a collective bargaining agreement would help ensure the relevant parties are aware of challenges with implementing the agreements.

Changes Provide Somewhat Greater Authority of FCMAT and COEs Over Fiscally Distressed Districts. The Governor’s proposal expands the role that COEs can ask FCMAT to perform in fiscally distressed districts from reviewing teacher workforce management to conducting a broad review of the district’s financial issues. We think this adjustment is reasonable, as it would provide FCMAT flexibility to review the district’s most salient fiscal issues. This proposal is also consistent with the type of review FCMAT currently conducts on behalf of COEs. The Governor’s proposal also clarifies existing law to ensure COEs continue to have stay and rescind authority over some fiscally distressed districts. Under current law, the COE’s authority to stay or rescind the actions of a fiscally distressed district expires when the COE approves the district’s budget. However, current law does not specify whether the COE’s stay or rescind authority would persist for another year if the COE disapproves the relevant district’s budget. We think these proposed changes would allow FCMAT and COEs greater flexibility to assist fiscally distressed districts in improving their fiscal health.

Concerns With Penalty of Perjury Language. We have concerns with the proposal to require superintendents and chief business officials (CBOs) to certify under penalty of perjury that their district can afford a newly negotiated collective bargaining agreement. Assessing the sustainability of a collective bargaining agreement requires a district to make a number of key assumptions. For example, the district must make assumptions regarding its projected revenue, staffing counts, and implementation of local initiatives (such as the planned opening or closing of schools). Given the uncertainty regarding these assumptions, a CBO or superintendent could certify that an agreement is sustainable and later be proven incorrect because of lower-than-expected state funding or school board actions that affect the district’s ongoing costs.

Some COEs Do Not Use Full Extent of Statutory Authority. While the Governor’s proposal would expand the fiscal oversight authority of COEs in some respects, it would do relatively little to address COEs that do not fully utilize the authority they already possess under current law. For example, in a 2019 audit of Sacramento City Unified School District’s financial challenges, the State Auditor concluded that the Sacramento COE could have used more of its authority to ensure the district implemented a corrective action plan after it disapproved the district’s budget. Some COEs may be reluctant to use more intrusive tactics, such as staying or rescinding a board action, in order to preserve their relationship with district officials or because they are uncertain of how much power they have to intervene in district affairs.

Recommendations

Adopt All but One of the Governor’s Proposals. With one exception described below, we recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposals. The proposals align with the goals of California’s school district fiscal oversight system and enhance the roles of COEs and FCMAT in helping districts avoid fiscal issues. In particular, the additional reporting requirements around district collective bargaining agreements could help ensure districts carefully consider the costs associated with their labor contracts.

Reject Penalty of Perjury Language. We recommend the Legislature reject the proposed language requiring superintendents and CBOs to certify under penalty of perjury that their district can afford a collective bargaining agreement. As discussed above, the proposed language would create significant consequences for superintendents and CBOs in situations that may be outside of their control.

Require Additional Reporting of COE Actions to Support Fiscally Distressed Districts. To better monitor how COEs are using their statutory authority to help districts improve their fiscal health, we recommend the Legislature adopt legislation to require COEs to publicly report when their districts do not comply with financial rules and describe how they responded to the lack of compliance. The Legislature could require such reporting in a number of key areas. For example, the Legislature could require COEs that rejected or conditionally approved a district’s budget to report on the support they provided to the district and the specific actions the district took to have its budget ultimately approved by the COE. We believe this additional reporting would encourage districts to comply with existing fiscal rules and create an added incentive for COEs to enforce compliance.